10.1 Introduction

In Chapters 4–9, we discussed the level of policy triage across various organizations within different countries. We demonstrated that the variation among organizations can be explained by a combination of different factors: blame-shifting limitations for central policymakers, opportunities for external resource mobilization, and the commitment to overload compensation.

In this chapter, we “zoom out” to identify broader patterns of variation across countries, sectors, and administrative levels. With this approach, we aim to show that our theory is not limited to explaining within-country variation but can also help to understand triage patterns on a larger scale. We begin by focusing on the differences between various country clusters, before discussing the variations on the sectoral and administrative level.

10.2 Empirical Findings: The Good, the Bad, and Those in Between

As we have outlined in our research design (see again Chapter 3), our country sample was deliberatively constructed to include all major administrative traditions found in Europe (Knill, Reference Knill2001; Painter & Peters, Reference Painter and Peters2010). This approach was intended to ensure that our theoretical arguments are not limited to a specific tradition but instead reflect broader patterns across various administrative setups. While we observed that our theoretical arguments hold true across different contexts, their “aggregated” insights also align well with what we would expect from the respective administrative traditions. Appendix A provides an overview of all organizations assessed in this book, structured by country and sector.

Denmark exemplifies the key characteristics of the Nordic administrative tradition, which is known for its strong bureaucratic professionalism, high levels of coordination, and a consensual policymaking approach across various sectors (Loughlin & Peters, Reference Loughlin, Peters, Keating and Loughlin1997; Verhoest et al., Reference Verhoest, Roness, Verschuere, Rubecksen and MacCarthaigh2010). When examining the combined triage patterns across sectors and organizations, Denmark stands out for its overall low levels of policy triage. This can be largely attributed to the country’s well-functioning balance between policy accumulation and capacity expansion. Both central and local implementation bodies in Denmark experience relatively low levels of overload, as moderate policy growth has been matched by corresponding increases in administrative capacities. Danish implementation bodies are relatively insulated from uncompensated overload, with central policymakers having limited opportunities to deflect blame for implementation failures onto them. This is consistent with the Scandinavian administrative tradition’s emphasis on consensus-based governance and collective responsibility, which reduces the likelihood of individual agencies being blamed for broader policy failures (Grønbech-Jensen, Reference Grønbech-Jensen1998). Additionally, these bodies have plentiful opportunities to mobilize additional resources when tasked with new responsibilities, reflecting the tradition’s robust coordination between different levels of government and a commitment to ensuring that administrative capacity keeps pace with policy expansion (Lægreid, Reference Lægreid, Nedergaard and Wivel2017). Moreover, Danish implementation bodies often demonstrate high levels of policy advocacy and a strong sense of policy ownership, fostering a strong institutional commitment to manage additional workloads. This aligns well with the Nordic model’s focus on professionalized bureaucracies characterized by a high degree of autonomy and trust, which empowers agencies to actively shape policies and ensure their effective implementation.

In contrast, Italy and Portugal, both grounded in the Napoleonic administrative tradition, illustrate cases where implementation bodies are particularly susceptible to overload. The strong centralization and hierarchical governance inherent in Napoleonic systems amplify the tendency for policymakers to prioritize legislative output over administrative feasibility (Peters, Reference Peters2008). Politicians, driven to generate policies, encounter few barriers to shifting blame for implementation failures onto sectoral authorities. The highly centralized decision-making structures provide them with the means to distance themselves from the challenges associated with day-to-day implementation (Knill et al., Reference Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2021b). Furthermore, implementers within these systems face limited opportunities to secure additional resources, a challenge compounded by the stringent budgetary controls enforced by the Ministry of Finance, which remains a consistent feature of the Napoleonic administrative model (Ongaro, Reference Ongaro, Painter and Peters2010).

Lastly, while Ireland, the UK, and Germany exhibit medium levels of policy triage on average, significant differences exist in the distribution and underlying patterns across these countries. Ireland and the UK, both following the Anglo-Saxon administrative model (Painter & Peters, Reference Painter and Peters2010), show a highly heterogeneous distribution of triage across policy sectors and administrative levels. The tradition’s strong emphasis on agency-based governance, competitive resource allocation, and managerial flexibility contributes to pronounced variation in overload vulnerability and compensation strategies (Knill, Reference Knill2001; Lodge, Reference Lodge, Painter and Peters2010). Some implementation bodies face frequent and severe triage, while others largely insulate themselves from overload pressures through the ability to secure additional resources or maintain institutional autonomy. The decentralized nature of implementation in the Anglo-Saxon model permits significant divergence among organizations, with some demonstrating robust policy advocacy and financial autonomy, while others are more susceptible to blame-shifting and resource limitations (Ziller et al., Reference Ziller, Peters, Pierre and Peters2012).

In contrast to the UK and Ireland, Germany presents a much more homogeneous picture, where triage is consistently observed across almost all implementation bodies, albeit with certain constraints. The German administrative system, characterized by a strong legal–rational bureaucracy, well-institutionalized coordination mechanisms, and a federal structure that distributes responsibilities across multiple levels of government, ensures a relatively balanced implementation landscape (Knill, Reference Knill2001: 72). The Germanic tradition’s emphasis on legalistic governance and rule-based administration not only limits the extent of severe triage but also constrains flexibility in resource mobilization, making it difficult to reallocate capacities dynamically in response to shifting policy demands (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1988). As a result, while Germany avoids the stark disparities in triage seen in the UK and Ireland, its bureaucratic rigidity and intergovernmental fragmentation contribute to overall medium levels of policy triage across the institutions.

In summary, our theoretical explanations align closely with existing knowledge on the characteristics of administrative traditions. This implies that specific institutional arrangements within these countries, as well as varying interpretations of the role of administration, can account for the observed triage patterns. However, it is essential to emphasize that administrative traditions do not render our theories redundant. At most, they can serve as a “proxy,” indicating the likelihood of certain explanatory factors being prevalent. As demonstrated in Sections 10.3 and 10.4, significant variation remains that cannot be explained by solely referring to the broader country background.

10.3 The Sectoral Discrepancies: More Triage in the Environmental Sector

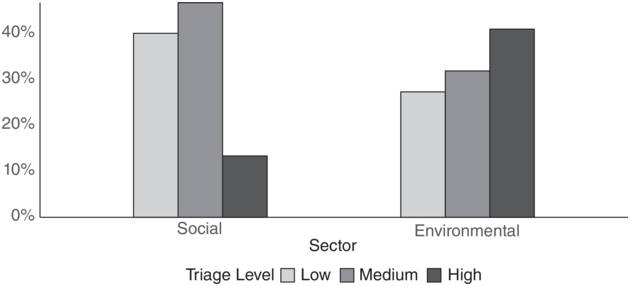

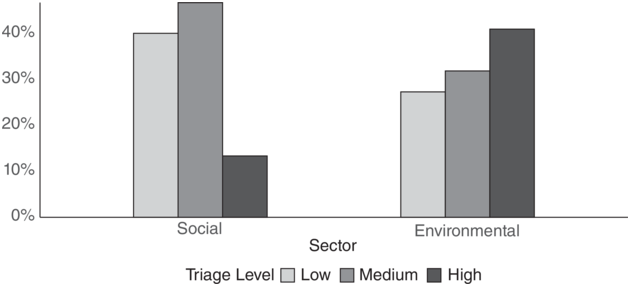

In Section 10.2, we concentrated on the variation across countries and assessed how well our insights align with those from the administrative tradition literature. Now, we turn our attention to the variation across the policy sectors under analysis. A strong pattern emerging from our analysis is that policy triage is more prevalent in the environmental sector than in the social sector. As shown by Figure 10.1, among the twenty-two environmental implementing organizations surveyed, 41 percent (nine organizations) exhibit high levels of triage, whereas in the social sector, only two out of fifteen implementers face similarly high levels. Correspondingly, a smaller proportion of environmental organizations exhibit low levels of triage (27 percent) compared to the social sector (40 percent), suggesting that environmental implementers are generally more prone to overload.

Figure 10.1 Policy triage across sectors.

A more nuanced picture emerges when comparing central and local implementers in the environmental sector. At the central level, organizations are polarized, with most agencies experiencing either very high or very low levels of triage. Of the twelve central environmental implementers surveyed, six faced high triage levels, while five reported low levels. In contrast, at the local level, triage is more consistently moderate: Of the ten local environmental implementers surveyed, six exhibited medium levels of triage, three faced high levels, and only one displayed low levels.

Cross-national variation further highlights the uneven distribution of policy triage in the environmental sector. High-triage implementers were found in four out of the six countries, with Denmark and Germany standing out as the only exceptions. Yet, even in Denmark, which generally exhibits low triage levels overall, Municipal Environmental Administrations (MEAs) deviate from this trend, showing medium levels of triage compared to the consistently low levels found in all other Danish organizations. This suggests that even in well-functioning administrative systems, specific organizational units can become vulnerable when administrative burdens exceed available resources and compensation mechanisms remain underdeveloped.

The highest concentration of environmental organizations experiencing severe triage is found in Portugal and Italy, where policy expansion has far outpaced administrative capacity. However, notable instances of high triage also appear in the UK and Ireland, particularly within the English Environment Agency (EA) and the Irish National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS). These cases illustrate a deviation from the expectation that policy triage aligns closely with Hanson and Sigman’s state capacity index (Reference Hanson and Sigman2021). Lastly, low-triage environmental organizations are concentrated in Denmark, Ireland, and the UK.

Turning to the social sector, the overall picture is more positive compared to the environmental sector, with the majority of implementing bodies exhibiting either medium or low levels of policy triage. Out of the fifteen social policy implementers surveyed, six display low levels of triage, while seven experience medium levels. This suggests that while implementation strain is present, it is generally less severe and more evenly distributed than in the environmental sector.

Cases of extreme triage remain the exception rather than the rule, with only two organizations facing high levels of triage: the Institute of Employment and Vocational Training (Instituto do Emprego e Formação Profissional; IEFP) in Portugal and the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) in the UK. These two agencies struggle with chronic administrative overload, high demand for services, and persistent resource constraints, exacerbated by recent economic crises and structural austerity measures. The DWP, in particular, has been heavily affected by politically driven administrative attrition, while the IEFP has faced long-term staffing shortages and underfunding, limiting its ability to cope with rising policy burdens.

No clear pattern of triage distribution emerges when scrutinizing individual subsectors within the social policy realm. Instead, variation in triage levels appears to be more closely linked to organizational mandates and structural design. Evidence from Ireland and the UK suggests that highly specialized regulatory bodies tend to experience lower levels of triage compared to general-purpose welfare providers. In case of the Pension Authority (PA) in Ireland and The Pensions Regulator (TPR) in the UK – the two organizations with the narrowest mandates in our sample – little to no triage was observable. In contrast, the countries’ general-purpose welfare providers – the Department for Social Protection (DSP) in Ireland and the DWP in the UK – show medium and, in the case of the latter, even high levels of triage.

Overall, our sectoral findings align with the theoretical expectations outlined at the beginning of this book. Policy accumulation is more pronounced in the environmental sector than in the social sector, reflecting the latter’s status as a more established policy domain with fewer opportunities for major policy expansion. However, the cases of the UK’s DWP and Portugal’s IEFP demonstrate that even modest policy growth can lead to severe policy triage when administrative capacities are curtailed and no longer align with rising demands. These examples underscore that it is not only the pace of policy accumulation that drives triage but also the extent to which implementation resources keep up with evolving responsibilities.

Environmental policy is highly Europeanized, with a significant share of new policies originating at the European Union (EU) level (Fernández-i-Marín, Knill, Steinbacher & Zink, Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2024; Knill, Reference Knill2001). In contrast, social policy remains largely a national matter. As national policymakers are not always the primary formulators in the environmental realm, one can expect lower levels of policy advocacy and ownership, reducing their incentive to proactively address potential implementation overload. Consequently, national policymakers have stronger incentives to ensure adequate implementation of nationally formulated policies while facing higher levels of accountability for potential implementation failures in the social sector compared to the environmental sector.

Furthermore, the effects of social policies are more immediately tangible to voters. As a result, vote-seeking politicians (Gratton et al., Reference Gratton, Guiso, Michelacci and Morelli2021) have a stronger incentive to prevent implementation deficits or outright failures in this domain. In contrast, implementation shortcomings in the environmental sector are often less visible to the general public, making them a lower political priority. Since environmental policy failures may not generate the same level of direct voter backlash, policymakers may feel less pressure to ensure effective implementation, further reducing incentives to allocate sufficient resources to implementing agencies. In line with this argument, Fernández-i-Marín et al. (Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Hinterleitner, Knill and Steinebach2025), demonstrate that issue salience can explain cross-temporal variation in resource provision in the social sector, but not in environmental policy.

Lastly, overload compensation within the organization may be lower in the environmental sector compared to the social sector. This expectation is rooted in the fact that environmental policy implementation is split between central agencies and local or regional authorities, whereas social policy is more often centralized under national jurisdiction. This distinction is reflected in our sample: Among the twenty-two environmental implementers surveyed, twelve are central agencies, while ten operate at the subnational level. In contrast, only four of the fifteen social implementers function at the regional or local level. Since local and regional authorities are typically multipurpose organizations, their ability to compensate for overload in environmental policy is constrained by competing demands across various policy domains. Unlike central agencies that have a singular focus, local authorities must balance the implementation of environmental policies with a range of other responsibilities.

Our findings provide strong evidence for these claims when analyzing the values of our three mechanisms. First, regarding blame-shifting, we observe that in the environmental sector, policy formulators face few constraints in half of the organizations surveyed. Notably, this trend holds across all sampled countries except Germany. This pattern contrasts sharply with the social sector, where low limitations on blame-shifting were found in only three organizations – one each in Portugal, Italy, and the UK – representing just 20 percent of the social implementers surveyed. In contrast, for 60 percent of social implementers, high constraints on blame-shifting were observable, meaning policymakers are provided with significantly less opportunities to deflect blame on implementation bodies.

Secondly, regarding resource mobilization, we find no significant differences between the environmental and social sectors. The distribution of this mechanism is strikingly similar across both policy areas, suggesting that the ability to secure additional resources is not inherently sector dependent. However, as we will explore in Section 10.4, the extent to which organizations can mobilize resources is strongly influenced by their governmental level. This lack of sectoral variation in resource mobilization opportunities supports our argument that institutional design – rather than policy content – plays the primary role in determining an organization’s ability to secure additional resources.

Last, regarding overload compensation, we observe lower levels of commitment in the environmental sector compared to the social sector. While two-thirds of social policy implementers display high levels of overload compensation, this applies to only a little over one-third of environmental implementers. We reasoned that this divergence in levels is centrally due to the involvement of subnational implementers, which face competing demands across multiple policy areas. Our findings strongly support this claim: While half of central environmental implementers exhibit high levels of overload compensation, only 20 percent of local environmental implementers do so. However, it is important to note that most environmental organizations across levels still demonstrate some degree of overload compensation, with the majority falling into the medium category. In other words, while social policy implementers generally compensate for overload more frequently, environmental implementers also do engage in compensation – it is simply less extensive.

In summary, the environmental sector is more prone to policy triage than the social sector across all sampled countries. This trend is largely explained by the prevalence of our three mechanisms, which not only shape triage at the organizational level but also hold when comparing sectors across countries. Specifically, lower constraints on blame-shifting and weaker overload compensation make environmental implementers more vulnerable to triage than their social policy counterparts. Crucially, this pattern persists even in contrasting cases. In Denmark, despite its overall strong administrative capacity, triage is more prevalent in the environmental sector – albeit still at relatively low levels. Conversely, Italy illustrates that even in a system facing significant administrative challenges, the social sector remains comparatively better off than its environmental counterpart. These sectoral findings demonstrate that the structural and institutional factors we theorized in the beginning of this book make environmental policy implementation more susceptible to overload and triage, regardless of the overall strength of a country’s administrative system.

10.4 No Love for the Country: More Triage on the Subnational Level

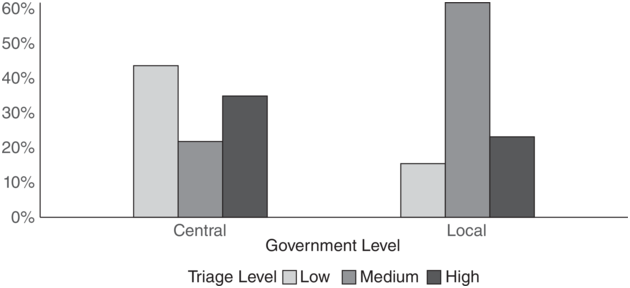

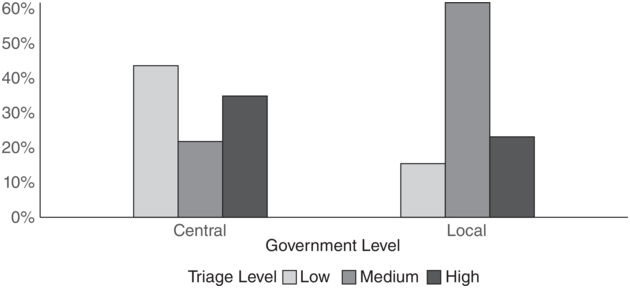

Turning to variation across government levels, we observe a contrasting pattern in triage levels between central and subnational implementers. As shown in Figure 10.2, the distribution of triage levels follows a U-shaped pattern, with most organizations experiencing either high (34 percent) or low (43 percent) levels of triage at the central level. By contrast, at the subnational level, the majority of implementers – 64 percent – exhibit medium levels of triage, while low triage is observed only in Danish social implementers and English local authorities. High levels of triage at the local level are relatively rare, occurring only in Italy’s regional and local environmental agencies and among Portuguese organizations across both policy sectors. Overall, we would describe the situation at the subnational level as “muddling through” – most implementers engage in some degree of triage, but the scale and severity are generally limited. This is largely due to their narrower mandates and the relatively low impact of the policies they implement compared to central agencies. Thus, while subnational implementers face resource constraints and competing priorities, triage, while present, is less disruptive than at the central level.

Figure 10.2 Policy triage by governmental level.

Compared to the subnational level, the situation for central implementers is more polarized, with most organizations falling into either the “good performer” or the “bad performer” category. We find central-level organizations with low levels of triage in all countries except Italy and Portugal. A closer look at these low-triage “good performers” reveals that they are exclusively highly independent agencies, such as the pension regulators in the UK and Ireland, and central agencies in both Danish sectors.

This pattern contrasts with less independent central authorities. A clear example is found in Ireland, where the EPA, an independent agency, experiences low levels of triage, whereas the NPWS, responsible for nature conservation, faces extremely high levels of triage. The key distinction between the two is their institutional setup – the EPA operates with high autonomy, while the NPWS remains heavily dependent on its parent department, the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage. A similar pattern can be observed in the English social sector: While TPR experiences low levels of triage, the DWP, the UK’s central social implementer, faces severe triage challenges.

However, the level of agency independence is not a sufficient condition for low triage levels. As seen in Portugal and Italy, even independent agencies struggle with high triage due to severe resource constraints and political interference. The case of the EA is particularly striking: Despite being one of the most independent environmental agencies in Europe – second only to the Irish EPA according to Gilardi (Reference Gilardi2008) – the organization experiences very high levels of triage. This suggests that while a high level of independence can shield organizations from certain vulnerabilities, it does not automatically protect them from triage if other structural or political constraints – such as chronic underfunding or blame-shifting – are present.

Turning again to our mechanisms, we observe that central-level implementers experience less blame-shifting compared to subnational organizations. This can be attributed to both physical and political distance, which reduces the opportunities for policy formulators to deflect responsibility for implementation failures onto central agencies. At the subnational level, blame-shifting is far more prevalent. Less than one-third of local organizations are well protected against blame-attribution attempts from the central government, while 42 percent are highly susceptible to it.

This pattern holds across most countries in our sample, with Germany and the UK being notable exceptions. In the UK, limited devolution implies that most responsibilities remain centralized in Whitehall, making blame-shifting to local implementers more difficult. The German case, on the other hand, is shaped by its highly federalized structure, which clearly delineates responsibilities across different levels of government. This institutional design inherently limits the central government’s ability to shift blame onto lower levels. Additionally, blame-shifting in Germany is further constrained by political alignments, as party constellations at the federal level often mirror those in subnational governments, reducing the incentive for central policymakers to deflect responsibility onto their regional counterparts.

The situation at the central level is more complex, as blame-shifting is highly polarized across central implementers. While half of the central organizations surveyed are well shielded against blame attribution from policymakers, the other half are highly vulnerable to it. The highest levels of blame-shifting at the central level are found in Portugal and Italy, where all central implementers face intense blame attribution. However, similar patterns are observable in Ireland and the UK, albeit for a more limited set of organizations. In Ireland, the NPWS is particularly vulnerable, functioning as an organizational “stepchild” that receives little institutional support. Here, blame-shifting is less overt, but the parent department systematically distances itself from responsibility, effectively leaving NPWS to absorb the consequences of implementation failures without adequate political backing. In the UK, blame-shifting is more aggressive and overt, particularly for the two major social and environmental policy implementers. Both organizations are frequently used as scapegoats to deflect attention away from failures at the policy-formulating level.

However, in both Ireland and the UK – similar to Germany – some central implementers enjoy strong reputations for their expertise and capabilities, significantly limiting the extent to which policymakers can shift blame onto them. Thus, in other words, these organizations exemplify how institutional credibility and public perception can act as shields against blame-shifting, preventing policymakers from easily attributing implementation failures to agencies that are widely viewed as competent and effective.

At the central level, a near-identical pattern emerges when examining organizations’ ability to mobilize additional resources. Out of twenty-three central implementers surveyed, ten face few constraints in securing additional resources, while another ten encounter severe limitations in doing so. This polarization suggests that resource mobilization opportunities are not uniformly determined by a country’s administrative system but rather – as we theorized earlier – by the institutional design and standing of individual organizations within the broader bureaucratic framework.

In contrast, the local level is significantly more constrained in its ability to mobilize additional resources, with almost two-thirds of subnational implementers facing limited opportunities for resource expansion. For the most part, this reflects the broader financial and political dependence of local authorities on central decision-makers, which often restricts their capacity to independently secure additional funds. However, notable exceptions exist that highlight how institutional structures and fiscal arrangements influence resource mobilization opportunities even on the subnational level. In the UK, local authorities benefit from multiple funding streams, allowing them to tap into grants, form partnerships, and generate local revenue, which provides them with greater financial flexibility than their counterparts in other countries. Similarly, in Germany, regional governments are directly involved in budgetary discussions, granting them greater influence over financial allocations and enabling them to negotiate additional resources when needed.

With regard to overload compensation, our findings present a relatively positive picture at both central and local levels, though with notable differences in intensity. At the central level, we observe a strong commitment to mitigating workload pressures, with most organizations demonstrating high levels of overload compensation. In contrast, local-level implementers predominantly display medium levels of compensation.

These differences can largely be attributed to the structural nature of central versus local implementers. Central agencies tend to be highly specialized, fostering strong policy ownership and advocacy, which translates into a greater willingness and ability to compensate for workload increases. By contrast, local implementers operate with a broader, more horizontal focus, covering multiple policy areas simultaneously. As a result, they constantly have to balance competing demands, making it more difficult to fully compensate for overload in any single domain.

Despite the generally strong compensatory patterns observed, exceptions exist at both levels, where implementers struggle to offset overload effectively. At the central level, three organizations exhibit minimal overload compensation, namely, the Irish NPWS, the British DWP, and the Portuguese IEFP. Similarly, at the regional and local levels, weak overload compensation is evident in the Bavarian welfare agency (Zentrum Bayern für Familie und Soziales; ZBFS) in Germany and the Portuguese Regional Coordination and Development Commissions (Comissãos de Coordenação e Desenvolvimento Regional; CCDRs). These cases span four of the six countries in our sample and provide important insights into the limits of overload compensation: Rather than reflecting an unwillingness to compensate, these organizations appear to have exhausted their compensatory capacity due to prolonged underfunding, rising workloads, and institutional constraints. Among these cases, the NPWS stands out as particularly illustrative. Unlike the other organizations, where compensatory capacities seem to be exhausted, the NPWS centrally faces structural challenges. Its fragmented organizational design and highly heterogeneous workforce hinder the development of a cohesive institutional identity and esprit de corps, weakening its ability to respond effectively to overload severely.

In sum, our findings reveal distinct triage patterns across central and subnational implementers. At the local and regional levels, most implementers engage in moderate triage, reflecting a “muddling through” approach rather than outright implementation failures. Their broad mandates, financial dependence on central governments, and exposure to blame-shifting make them particularly vulnerable. While some, like English local authorities and Danish social implementers, experience minimal triage, others – especially in Italy and Portugal – face more severe implementation challenges. At the central level, by contrast, triage patterns are more polarized, with organizations experiencing either high or low triage. In this context, independent agencies tend to fare better due to stronger resource access and insulation from day-to-day politics.

Blame-shifting is a key driver of triage, especially at the subnational level, where local implementers are often used as scapegoats. At the central level, blame-shifting is more selective, typically targeting organizations with weaker institutional standing. Resource mobilization also varies: While some central agencies can secure additional funding, most local implementers face severe constraints. Despite generally strong overload compensation, limits are becoming increasingly apparent. Central agencies, particularly specialized ones, tend to mitigate workload pressures more effectively, whereas local implementers struggle with competing priorities. Some organizations have exhausted their compensatory capacities, illustrating the risks of prolonged administrative strain and growing implementation deficits.

10.5 Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings highlight significant variation in policy triage across country clusters, sectors, and government levels. Denmark emerges as the best-performing case, where moderate policy growth has been matched by administrative expansion, limiting the need for triage. At the other end of the spectrum, Portugal and Italy exhibit high levels of triage due to a combination of rapid policy expansion, resource constraints, and limited compensatory capacity. Ireland, Germany, and the UK occupy an intermediate position, with medium levels of triage on average, though their internal patterns differ based on institutional configurations and sectoral dynamics.

By comparing these insights with the literature on administrative traditions, it appears that Nordic countries are overall less susceptible to policy triage, while southern countries tend to be more so. In the countries standing in the Anglo-Saxon and Germanic tradition, the pattern is more varied. Germany’s strong legalistic culture seems to generally limit policy triage to a moderate level. In contrast, in the Anglo-Saxon world, where public authorities have more discretion and autonomy, the pattern is more fragmented, with some instances of minimal engagement and others demonstrating high levels of policy triage.

The environmental sector is generally more prone to triage than the social sector. This discrepancy is primarily driven by weaker overload compensation, higher opportunities for blame-shifting, and the fragmented implementation landscape in environmental policy. While social policy remains largely within national jurisdiction, environmental policy often involves multiple governance levels and is influenced by external factors such as EU regulations. As a result, policymakers face fewer political incentives to ensure adequate implementation in the environmental sector, leading to a greater strain on implementers.

Similarly, our analysis reveals distinct differences between central and subnational implementers. The central level tends to be characterized by a more polarized triage pattern, with some organizations enjoying strong resource mobilization and insulation from blame-shifting, while others have a higher risk of being forced to triage. Subnational implementers, by contrast, are more uniformly exposed to medium levels of triage, reflecting their broad mandates and financial dependence on central governments. While some, such as the Danish social implementers and English local authorities, experience minimal triage, others – especially in Italy and Portugal – face more severe challenges.

Despite strong overload compensation in many organizations, the limits of this strategy are becoming increasingly apparent. Central agencies, particularly those with specialized mandates, tend to mitigate workload pressures more effectively, whereas local implementers struggle with competing priorities. Certain organizations have already exhausted their compensatory capacities, illustrating the risks of prolonged administrative strain. Without structural reforms to address resource constraints, streamline responsibilities, and improve coordination between policymakers and implementers, the risk of growing implementation deficits will likely continue to rise.