1.1 The Political Economy of High-End Language Work

A good friend told me she once saw a talk given by John F. Kennedy’s speechwriter, Ted Sorensen. During the Q&A afterwards an audience member asked whether he had penned Kennedy’s famous line, “ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.” Mr. Sorensen hesitated, and then responded, “Ask not.” (The audience, of course, erupted in laughter.) This anecdote nicely encapsulates the mystique surrounding speechwriting as a profession, as well as the code which these markedly high-end language workers must carefully follow – they are the authors but not the animators nor principals of their craft (Goffman Reference Goffman1981). At the same time, and as others have noted (e.g. Hanks Reference Hanks, Silverstein and Urban1996), the complexity of these roles should not be understated. Indeed, Mr. Sorensen’s response is all pretense, and serves as a coy admission of his authorship; speechwriters’ work may take place behind the scenes, but they still routinely claim ownership and expertise. And certainly, they are economically invested in the material success of their linguistic output: words are power, but words are also money. As Del Percio, Flubacher, and Duchêne (Reference Del Percio, Flubacher, Duchêne, García, Flores and Spotti2016) astutely observe, there often exists “a tension between the potential of language to enable access to symbolic and material capital and the complex logics, interests, and technologies regulating the convertibility of language into capital in specific markets” (69). Put another way, implicated in speechwriting are both the “symbolic power of language” (Kramsch Reference Kramsch2021) as well as the political economy of the linguistic market – two interconnected (but not necessarily equivalent) systems of value. As an additional case in point, in White House Ghosts political correspondent Robert Schlesinger (Reference Schlesinger2008) documents the very material ramifications of speechwriters “going rogue” – George W. Bush’s former staffer David Frum was supposedly fired for claiming he wrote the famed line “axis of evil,” and much later the administration was plagued by two other speechwriters’ public disagreements over the extent of their individual roles and impact. All of which is to say that the “production format” (see again Goffman Reference Goffman1981) of speechwriting offers a compelling case study of the real worth of words in popular culture, as well as the material value placed on the laborers who produce them (e.g. Thurlow Reference Thurlow and Thurlow2020b).

As such, and following those who have engaged with linguistic labor as a phenomenon of our contemporary, knowledge-based neoliberal economy (e.g. Duchêne and Heller Reference Duchêne and Heller2012), I am largely interested in how certain types of language workers are explicitly valued in the market (cf. Jakobs and Spinuzzi Reference Jakobs, Spinuzzi, Jakobs and Perrin2014). Thus, I follow Thurlow’s (Reference Thurlow and Thurlow2020b) recent thinking concerning high-end language workers; the community in which I am interested is not an example of those who are without sociopolitical or economic capital. Rather, speechwriters – whose livelihoods are based on the crafting and designing of words for powerful, public figureheads – are well remunerated and relatively prestigious. However, and as is the case for many wordsmiths, the product of speechwriters’ language work is almost always attributed to someone else. It is somewhat surprising, then, that language scholars have predominantly focused on political speeches/rhetoric without addressing the backstage laborers and actual producers of this discourse (see Wodak Reference Wodak2009 for an important exception). Additionally, while applied linguists have thoroughly documented the lower-end “precarious” working contexts of irregular employment (e.g. Park Reference Park and Chun2022) and online teaching (e.g. Curran and Jenks Reference Curran and Jenks2023), as well as the markedly invisibilized language work of professionals like medical doctors (e.g. Locher Reference Locher2017) and social workers (e.g. Lillis Reference Lillis2017), the linguistic labor of speechwriters has been entirely ignored. This is all to say that it is perhaps time for language scholars to approach contemporary language work with this kind of high-end wordsmithery in mind.

To this end, I systematically investigate the ways in which speechwriters talk about their professional practices, as well as the material procedures which guide the production of their deliverables. This metadiscursive, text trajectory approach enables me to comment in detail on the microlinguistic processes which characterize these wordsmiths’ work (cf. Macgilchrist and Van Hout Reference Macgilchrist and Van Hout2011). Indeed, this is not a tell-all narrative of political or professional secrets; it is a nuanced examination of the relationship between text and talk, and between the various stakeholders in public rhetoric. My data, in this regard, comprise a robust collection of secondary and primary sources including memoirs and training resources, a public talk by Jon Favreau (President Obama’s former speechwriter), recorded interviews with practicing speechwriters, fieldnotes from a professional speechwriting course, speech drafts and other texts, a video-recorded meeting with several speechwriters, and US Presidential archive materials. As such, my methodological approach follows ethnographic work which is focused on the interconnectedness between different genres of (textual) data (e.g. Woydack and Rampton Reference Woydack and Rampton2016; Lillis and Maybin Reference Lillis and Maybin2017); this sort of discourse-centered approach is simultaneously situated and reflexive, thus fostering a holistic micro-to-macro perspective. My analysis of these data demonstrates precisely how speechwriters come to discursively enact “the new worker-self” in late or advanced capitalist regimes, essentially articulating their personhood as a bundle of “commodifiable skills” (Urciuoli Reference Urciuoli2008: 211). This case study therefore contributes nicely to recent conversations in critical applied linguistics related to the market-driven understanding of contemporary working life (e.g. Catedral and Djuraeva Reference Catedral and Djuraeva2023).

In this vein, it is the political-economic ramifications of professional language work which is the primary motivation for this book. Speechwriters are bound by the expectation that they “make themselves profitable” (Martín Rojo and Del Percio Reference Martín Rojo, Del Percio, Martín Rojo and Percio2020: 11), and yet this depends on their being entirely invisibilized, relatively unknown, and completely erased from their material output – reflecting the contradictions of a market which both empowers and disempowers its workers (cf. Panaligan and Curran Reference Panaligan and Curran2022). And consequently, speechwriters’ ultimate “status anxiety” (see De Botton Reference De Botton2004) comes to the fore: their discourse portrays not only the complex “semiotic ideologies” (Keane Reference Keane2018) of contemporary language work but also a nuanced and simultaneous (dis)avowal of power and prestige. In this way, speechwriters – even as elite, highly skilled professionals – are workers who “have no choice but to sell their labour” (Holborow Reference Holborow2018: 59). Contrary to other sorts of language workers – Cameron’s (Reference Cameron2000) call center workers, for example – they are not oppressed nor necessarily exploited, but still, they are not immune to the precarities of a (linguistic) marketplace entrenched in ideological and socioeconomic struggle (cf. Park Reference Park and Chun2022).

Given the clear entanglement of language and capitalism in contemporary social life (see also Chun Reference Chun2022a), the purpose of this book is to tease apart the inner workings of these simultaneously discursive and material processes, using metadiscursive insights from professional speechwriters. As such, I aim to answer the following questions:

1. What are the typical, daily professional practices of speechwriters, and how do they connect to the production format of their work?

2. How does the work of speechwriters intersect with the wider political economies of professional life – both in terms of linguistic labor and the more general disciplines (e.g. politics, commerce) in which they practice?

3. How do speechwriters understand the nature of language, its intersection with other semiotic modes, and its material consequences? And relatedly, to what extent do they recognize their work as both linguistically and ideologically consequential?

These questions are intended to produce empirically grounded conceptual insights for (critical) applied linguistics, sociolinguistics, discourse studies, and linguistic anthropology. Following Coupland’s (Reference Coupland and Coupland2016) call to more effectively document the real chains of metadiscursive activity which (re)produce the social world, this monograph is at once theoretically and methodologically germane. On the one hand, it contributes to cutting-edge debates related to the commodification of both language and labor, demonstrating the discursive negotiations that co-constitute socioeconomic inequality (see again Holborow Reference Holborow2018). On the other, this work pointedly decenters language scholars as the arbiters of linguistic skill and knowledge. By inviting metadiscursive commentary and self-reflection (of both researcher and research participants), I demonstrate what we as linguists can learn from other sorts of “elite” language workers (see Thurlow and Britain Reference Thurlow, Britain and Thurlow2020). In this sense, the book is intended to help critical scholars envision what Bucholtz’s (Reference Bucholtz2021) “community-centered collaboration” methods might look like in practice, and how this sort of approach allows for a deeper understanding of how status claims and competition circulate in professional contexts.

In what follows, I first engage with important scholarship related to language in institutional and professional contexts (Section 1.2.1); language work and wordsmiths (Section 1.2.2); metadiscourse (Section 1.2.3); and reflexivity and semiotic ideologies (Section 1.2.4). In establishing this comprehensive theoretical framework, I document not only the ways in which “talking work” (Iedema and Scheeres Reference Iedema and Scheeres2003) both establishes and contests particular communities of practice but also how larger issues related to metalinguistic awareness and political economy are implicated in these processes. Next, I briefly map the history of speechwriting as well as the scant scholarly engagement with practitioners, and then turn to the specifics of my project. I provide detailed overviews of my data collection before turning to an explanation of critical ethnographic discourse analysis (cf. Rampton et al. Reference Rampton, Tusting, Maybin, Barwell, Creese and Lytra2004) as my primary methodological approach. Here I also introduce the three primary rhetorical strategies which arise in speechwriters’ metadiscursive accounts of their work: invisibility, craft, and virtue. Lastly, I conclude with an overview of the remaining chapters, throughout which I argue that speechwriters are simultaneously elevated and erased – their authorship both avowed and disavowed. It is these complex discursive negotiations which ultimately reveal the status anxieties and relative precarity of their positions as wordsmiths, who are nevertheless beholden to the demands of the neoliberal, linguistic market.

1.2 Theoretical Framework

1.2.1 Language in Institutional and Professional Contexts

Discourse analysts have long been interested in language at work, whether under the label institutional (e.g. Drew and Heritage Reference Drew, Heritage, Drew and Heritage1992), workplace (e.g. Holmes Reference Holmes2007), professional (e.g. Kong Reference Kong2014), or organizational discourse (e.g. Wee Reference Wee2015). Various others have documented this literature extensively (see Vine’s Reference Vine2018 Handbook of Language in the Workplace, for example) and so my review here is relatively brief and primarily considers the differences between these four terms. Although institutional and workplace discourse are used rather interchangeably in the literature, the former is arguably a bit broader, and it is the term which first gained traction in applied linguistics as a way of describing the distinction between language that emerges specifically in public contexts instead of more private ones. In Drew and Heritage’s seminal work on the topic they propose a set of main differences which serve to distinguish institutional discourse: 1) it tends to be goal-oriented; 2) it involves particular constraints on what speakers may say in any given context; and 3) it is often associated with inferential frameworks, or contextualized heuristics which speakers draw on when determining the meaning or function of emergent talk. In general, these parameters point to an important takeaway in the literature – institutional discourse is conceptualized as relatively more structured, regulated, and systematic than the sorts of language use which crop up in private spheres (see Sarangi and Roberts Reference Sarangi and Roberts1999). This is not to say, however, that the everyday communicative work required for maintaining interpersonal relationships is not important in these broader institutional contexts. Indeed, this has been a primary focus for scholars of workplace discourse in particular.

Koester (Reference Koester2010) describes workplace discourse as communication which occurs across any sort of occupational setting, encompassing interactions between co-workers, customers and clients, lay people, and professionals (5). In addition to some of the primary structural concerns related to workplace interaction, Koester highlights the fundamental nature of relational talk at work, noting that interpersonal management is a defining feature of accomplishing tasks effectively. Likewise, many other scholars have examined issues such as the construction of power and solidarity (e.g. Tannen Reference Tannen1994), gender and/or ethnic identity (e.g. Marra and Kumar Reference Marra and Kumar2007), and negotiating leadership (e.g. Rogerson-Revell Reference Rogerson-Revell, Angouri and Marra2011). In Chapter 5 I discuss this strand of research more thoroughly; here I will just underscore that as Holmes (Reference Holmes, Tannen, Hamilton and Schiffrin2015) attests, much of this work has documented the unavoidable manifestation of power and hierarchy across white-collar professions specifically, leaving the blue-collar workforce markedly understudied (but see Baxter and Wallace Reference Baxter and Wallace2009, Stubbe Reference Stubbe2010, and Gonçalves and Kelly-Holmes Reference Gonçalves and Kelly-Holmes2021 for important exceptions). For this reason, many scholars adopt the distinctive term professional discourse to convey the necessary privilege and specialization attached to these more “elite” kinds of workplaces (see also Koester Reference Koester2010 on “business discourse”).

Following this tack, Kong (Reference Kong2014) opens his book Professional Discourse with a powerful quote from Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu and Wacquant1989), part of which I have reproduced here: “The notion of profession is dangerous because it has all appearances of false neutrality in its favor. Profession is a folk concept which has been uncritically smuggled into scientific language and which imports in it a whole social unconscious” (p. 37, cited in Kong Reference Kong2014: 1). Here Bourdieu captures the structuring potential of language, alluding to the ways in which the prominent cultural indexicalities of a term like “profession” serve to erase and normalize its hidden ideological stance. Indeed, there is considerable status attached to defining oneself as a “professional.” Kong argues that professionals are part of the “new work order” (see Gee et al. Reference Gee, Hull and Lankshear1996), which is defined by the increasing need for specialization and efficiency/productivity in neoliberal economies. Subsumed within this conceptualization is an orientation towards specialist training in particular – for Kong, professionals are partly defined by this shared experience, as well as the ways in which they can be described as “symbolic communities” who orient around shared knowledge, functions, ideologies, and discursive practices. Relatedly, Sarangi and Roberts (Reference Sarangi and Roberts1999) make the point that a tension exists between what practitioners view as “institutional discourses” and the language they produce in their professional communities. In other words, professionals might see themselves as operating outside or separately from “institutions”; this shared ideological stance is additionally community-building. What emerges, then, is how professional discourse is concerned with establishing parameters of belonging. While these result in inevitable hierarchies between ingroup members themselves, they also allow people to claim prestige vis-à-vis others in the workforce. Importantly, this status competition is intensified by notions of meritocracy and efficiency – both of which are integral to upholding ideologies of neoliberal advancement.

In this regard, Wee (Reference Wee2015) highlights the consumer-oriented styling of organizational discourse in particular. For Wee, and precisely because of the role of neoliberalism in shaping various public discourses, it is useful to consider organizations to be “corporate actors” of specific sociolinguistic interest. Rather than framing organizational discourse as a contextual backdrop, Wee relies on a number of case studies which foreground the ways in which the communicative practices of organizations (e.g. universities, small businesses) demonstrate and disseminate ideologies pertaining to “autonomy, innovation, creativity, strategy and the ability to respond quickly to competition” (7). The pervasiveness of this “enterprise culture” as a normalizing rhetoric not only attributes human virtue to entrepreneurial qualities but also effectively demands that everyone – organizations, and the individual workers of which they are comprised – reproduce these discourses (see also Mapes Reference Mapes2021a on “pioneer spirit”). As Wasson (Reference Wasson2006) points out, this has practical consequences for employees. Although the language of enterprise might have distinctly empowering effects as it allows workers to establish themselves as profitable businesses, it can also be disempowering in that the market ultimately controls the way in which they claim value. Various others have documented a similar positioning among professionals across various domains, including medicine (e.g. Iedema Reference Iedema2005), language teaching (e.g. Panaligan and Curran Reference Panaligan and Curran2022), and the migration industry (e.g. Del Percio Reference Del Percio and Chun2022). Indeed, what these and other studies have determined is that workers these days are often complicatedly enlisted into upholding the fundamentally hierarchical tenets of the so-called new economy, in which the product of one’s work is often specifically knowledge-based rather than rooted in industrial labor/manufacturing. In this vein, I turn now to language work.

1.2.2 Language Work and Wordsmiths

Cameron’s (Reference Cameron2000) study featuring call center workers in the UK highlights the linguistic impacts of globalization on the provision of services in competitive markets. Her observation that employees’ language use is both strategically styled and highly monitored demonstrates the ways in which these linguistic laborers have been ultimately exploited – their skills commoditized and anonymized as cogs in the neoliberal apparatus of wealth accumulation (see again Harvey Reference Harvey2005). While others have explored similar processes unfolding in various multilingual contexts (e.g. Heller Reference Heller2003; Duchêne and Heller Reference Duchêne and Heller2012), few scholars have attended to the sorts of language work which are more explicitly valued, or “elite” (but see Barakos Reference Barakos2024 on “elite multilingualism”). In invoking this term – which is sometimes contested – I align with other scholars who see claims to status or privilege as both material realities and also discursive accomplishments (e.g. Thurlow and Jaworski Reference Thurlow and Jaworski2017a). In other words, high-end language workers not only possess relatively measurable amounts of social, cultural, and economic capital but also explicitly self-style as prestigious, powerful, and professional. And in terms of speechwriters specifically, they are prominently portrayed in fictionalized media representations (e.g. The West Wing; see also Chapter 2), and their memoirs have graced The New York Times bestseller list (e.g. What I Saw at the Revolution, 1990, Peggy Noonan). Thus, as these pointedly discursive manifestations of speechwriters’ status circulate, their eliteness is performed into being.

In an effort to turn language scholars’ analytical attention towards these more privileged wordsmiths, Crispin Thurlow’s (Reference Thurlow2020a) edited volume The Business of Words covers professions such as dialect coaches, court judges, word artists, and school principals, to name just a few. Notably, in mapping the complex linguistic issues which arise in each of these domains, it becomes clear that prestigious, institutionalized language work in late capitalism is not only rife with social misunderstanding and inconsistency but also frequently used to support claims to expertise, status, and value (see also Karrebæk and Sørensen Reference Karrebæk and Sørensen2021 on Danish courtroom interpreters). However, and as Duchêne (Reference Duchêne and Thurlow2020) notes in his contribution to the volume, academics’ understanding (and labeling) of these language work hierarchies must not be approached uncritically. Indeed, Thurlow’s collection demonstrates the ways in which “elite” language work is distinctly profitable (for a range of stakeholders) and imbricated in the structures of neoliberal productivity, individuality, and status competition (see also De Costa et al. Reference De Costa, Park and Wee2016). Similarly, in their analysis of online language teacher profiles Curran and Jenks (Reference Curran and Jenks2023) demonstrate how teachers make market-centric choices to succeed in the “gig economy,” reflecting the real commodification of their labor (see also Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Young, Jowaisas, Boakye-Achampong and Sam2022). Ultimately, speechwriters, like all explicitly specialized professionals (see Section 2.3.1) must continually (re)establish their value – vis-à-vis each other, as well as other members of the “wordforce” (Heller Reference Heller2003).

In this regard, claiming professional worth and status based on neoliberal ideals of entrepreneurialism and market productivity can be challenging for those whose markedly “elite” labor is nonetheless largely invisibilized. As Thurlow and Britain (Reference Thurlow, Britain and Thurlow2020) point out in the case of dialect coaches, obscurity is the typical state of being for workers whose success is measured by the unnoticeable quality of their craft. Notably, this more discreet labor runs counter to contemporary society’s prioritizing of attention-seeking personal branding and “microcelebrity” (Marwick Reference Marwick2013). However, in his investigation of various behind-the-scenes professions (e.g. UN interpreting) Zweig (Reference Zweig2014) observes that invisibility is associated with perfection, meticulousness, and responsibility (cf. Inoue Reference Inoue2011 on nineteenth-century stenographers in Japan). Likewise, Portmann’s (Reference Portmann2023, 2025, Reference Portmann2026) user experience (UX) writers pride themselves on their ability to construct inconspicuous micro-copy for digital interfaces (see also Droz-dit-Busset Reference Droz-dit-Busset2023 on advertising copywriters). In other words, for some professional communities of practice it is precisely their erasure which solidifies their value as high-end language workers. And indeed, it is a standard by which ingroup membership may be both claimed and contested – for speechwriters, this is a distinction which is often metadiscursively negotiated (for example, see Jon Favreau’s repair from “we” to “he” in Section 2.3.3). I turn now to this theoretical domain.

1.2.3 Metadiscourse

In lieu of documenting the breadth and scope of metalinguistic theory (others have done this very successfully, e.g. Jaworski, Coupland, and Galasinski Reference Jaworski, Coupland and Galasinski2004; Gordon Reference Gordon2023), I will attend to just three relevant points. First, although I primarily refer to “metadiscourse” to conceptualize my understanding of “discourse about discourse or communication about communication” (Vande Kopple Reference Vande Kopple1985), I also use the alternative terms “metacommunication,” “metalanguage,” and “metalinguistics” more-or-less interchangeably throughout the book. However, I do think it is useful to acknowledge the scalar differences between different sorts of metadiscourse. For example, Preston (Reference Preston, Jaworski, Coupland and Galasinski2004) categorizes overt commentary related to language use as Metalanguage 1; intertextual references to prior conversations as Metalanguage 2; and widely shared beliefs about language use in a particular community as Metalanguage 3. While this heuristic is perhaps overly simplistic, it serves to establish the rather broad theoretical significance of meta to everyday discursive practices. Indeed, and as Cameron (Reference Cameron, Jaworski, Coupland and Galasinski2004) states emphatically, “a language that lacks resources for reflexive comment on its own characteristics is incomplete” (311). Thus, it appears that human communication relies quite fundamentally on metadiscursive commentary. It is used to make sense of social differentiation (e.g. Kemper and Vernooy Reference Kemper and Vernooy1993); it can be a resource for establishing a larger moral order (e.g. Wilson Reference Wilson, Jaworski, Coupland and Galasinski2004); it gives access to the poetic functions of language (e.g. Jakobson Reference Jakobson and Sebeok1960); and it is a primary strategy for creating humor, rapport, and involvement (e.g. Tannen Reference Tannen2005 [1984]). Metalanguage is therefore integral to the microlinguistic details of everyday interaction and an underlying element of all language use.

Various scholars have engaged with the specific ways metadiscourse arises in people’s communicative practices across a variety of research sites. As I mentioned a moment ago, the scope of this literature is truly vast – it pertains to spoken, written, and digital contexts, with scholars using methods that range from eliciting “language portrait” drawings from hundreds of participants (Busch Reference Busch2012) to analyzing character development on The West Wing (Richardson Reference Richardson2006). Most recently, Gordon (Reference Gordon2023) expertly examines the relationship between metadiscourse and intertextuality specifically, arguing that participants in an online discussion forum rely on intertextual linking as a resource for metadiscursive meaning-making. In turn, this activity often reveals their ideological positionings, illuminating the ways in which metalinguistic commentary is an important means of establishing ingroup status for particular communities of practice. Relatedly, in the conclusion to his edited volume on theoretical debates in sociolinguistics, Nikolas Coupland (Reference Coupland and Coupland2016) identifies metacommunication as a primary area for future scholarship, writing:

What is distinctly social about language resides in its metacommunicative aspects. This is where the social is embedded into linguistic practice, and how language use comes to be a socially constituted practice. The meanings structured around ways of speaking can usefully be seen as being sustained through reflexive (metapragmatic) representations.

Thus, and echoing the introduction to Jaworski, Coupland, and Galasinski’s (Reference Jaworski, Coupland and Galasinski2004) edited volume, the real crux of metadiscourse is the way in which it neatly exposes the inherently social aspects of language in use. A focus on “language in the context of linguistic representations and evaluations” (Jaworski et al. Reference Jaworski, Coupland and Galasinski2004: 4) thereby allows researchers to effectively document how metalanguage serves to continually (re)produce the social world. This brings me to my final point.

Eliciting metadiscourse in applied linguistic research is a methodological strategy which is not only aimed at particular kinds of data collection but also necessary for the researcher’s positioning vis-à-vis their participants. On the one hand, scholars have demonstrated how obtaining self-reflexive commentary on various types of language-in-use is a fruitful exercise in determining the social implications of discursive practices (see again Busch Reference Busch2012). On the other, it is likewise necessary to account for our own scholarly evaluations and determinations of what sorts of language (and what sorts of speakers) are worthy of study. To return to Duchêne’s (Reference Duchêne and Thurlow2020) point, we must thus consider how our labeling and classifying schemes belie the metadiscursive entanglements of researcher-researched, or, for example, “elite-nonelite” language worker (cf. Woydack Reference Woydack2019) – and furthermore, whether participants themselves find these categories to be relevant or interesting (more on this in Chapter 6). As Lillis (Reference Lillis2008) observes, this level of (auto)ethnographic engagement allows the researcher to stay firmly located in their informants’ sociohistorical contexts. Importantly, this approach also brings to the fore the similarly “meta” idea of reflexivity – a concept which is not only fundamental to everyday language use (e.g. Lucy Reference Lucy1993), but also an inherently neoliberal social/professional positioning. Indeed, the contemporary conditions of late capitalism call for this sort of (inter)personal reflection as a means for increasing profitability. I elaborate in Section 1.2.4.

1.2.4 Reflexivity and Semiotic Ideologies

To introduce this section I will begin by briefly outlining how I understand “neoliberalism.” I have written extensively about this topic elsewhere (e.g. Mapes and Ross Reference Mapes and Ross2020), but to briefly summarize: what we might call advanced capitalism has ultimately resulted in increased inequality despite advocating for individual prosperity, liberty, and choice (e.g. Chun Reference Chun and Preece2016). In this regard, my argument throughout this book is undergirded by two important points. First, neoliberalism is not only a particular version of capitalism dependent upon “accumulation by dispossession” (Harvey 2023), but also a hegemonic system of control. In addition to being a material reality, it is an embodied and discursively (re)produced ideology which is presented as the only “rational” option. In this way, it is powerfully normalizing in that it erases other socioeconomic options or systems from view (cf. Chun Reference Chun2022a). Second, and more to the point, neoliberalism demands (inter)personal reflexivity which in turn prompts social actors to consistently “attempt to make themselves profitable by the application of self-reflection, self-knowledge and self-examination” (Martín Rojo and Del Percio Reference Martín Rojo, Del Percio, Martín Rojo and Percio2020: 11). This sort of “governmentality” – discipline-by-self – is reframed as progressive self-betterment, despite the ways in which it quite clearly helps to structure and maintain the status quo (see Mapes Reference Mapes2021a; Adkins Reference Adkins2003). In other words, and as Anthony Giddens (1993) noted long ago, modern life is a continually reflexive process of decision-making, meaning production, and status competition.

Turning now to reflexivity in language use specifically, it is clear that our daily linguistic practices are reflexive in that repeated evaluations of linguistic signs are built into the scaffolding of the languages we speak (see again Lucy Reference Lucy1993, and discussion in preceding section). These fundamentally structural processes parallel the reflexivity of language in use more generally. Importantly, this sort of reflexivity occurs at a much larger scale – especially when researchers specifically request that their participants engage in “talk about talk.” This is where the notion of semiotic ideologies becomes germane. As Keane (Reference Keane2018) theorizes, the semiotic processes of daily life are inherently reflexive, and as such, ideological (see also Section 1.5). His use of the phrase “semiotic ideologies” is thus meant to capture how people understand and use signs in society as profound, meaning-making tools which link their experiences to their general beliefs about the world (66). For Keane, these metapragmatic processes are highly dynamic and dependent on the “representational economy” of any historical or social context – as human actors make determinations about what is natural, for example, or what is ethical, they function within contexts of “symbolic authority” (Thurlow Reference Thurlow2017). An example of this can be seen in Thurlow’s study on “sexting,” which demonstrates nicely how semiotic ideologies operate at the level of multimodal communicative practices and the interesting ways in which media and language ideologies represent simultaneously (dis)similar processes (see also Gershon Reference Gershon2010; Ehrlich Reference Ehrlich2018).

While the aforementioned strand of research sheds light on the ways in which certain types of semiotic signs (e.g. photos, spoken language, text messages) are valued over others, for my purposes it is useful to examine the ramifications of semiotic ideologies in terms of what kinds of knowledge and meaning production are strategically embraced by particular communities of practice – and therefore have indexical, agentive significance (see Parish and Hall Reference Parish, Hall and Stanlaw2020). For instance, scholars have investigated the ways in which nonnormative, individual semiotic ideologies can destabilize and push back against more mainstream, institutional ones related to citizenship and gender (Hegarty Reference Hegarty2023), the value of human life (Rouse Reference Rouse2004), and even ethnographic research practices (Berman Reference Berman2018). Conversely, Arndt (Reference Arndt2010) reveals how marginalized voices (e.g. Indigenous activists) can be muted by the powerful cultural discourses of more dominant stakeholders. Perhaps unsurprisingly, across all these examples, context is key – interlocutors’ interpretation of signs is firmly connected to particular ways of being in the world, and in many cases, to the ways they are socialized into constructing meaning and value.

Carr’s (Reference Carr2011) monograph concerning the language of addiction treatment offers a powerful case study, in this regard. Her deeply ethnographic approach, entailing lengthy (and repeated) interviews with both therapists/clinicians and the women receiving treatment reveals how addicts are taught to speak like “healthy and valuable American [people]” (13). This method of articulating or narrating one’s recovery is rooted in “principles of inner reference” – a semiotic ideology that demands participants excavate their psyches in order to produce “perfectly clean or sober language” (15). In turn, one’s ability to speak like a proper, healthy person results in access to resources and other material affordances, revealing the complex ways in which aligning to the semiotic ideologies of particular communities can have political economic ramifications. In essence, and returning to Martín Rojo and Del Percio (Reference Martín Rojo, Del Percio, Martín Rojo and Percio2020), while people’s use of language (and other signs) is to some extent agentive, it is also co-constructed by the ideological apparatus of neoliberal governmentality. In deciding “what their world means” (see Souleles Reference Souleles2020), individuals learn to appropriately perform valuable/profitable citizenship. Thus, every reflexive evaluation of semiosis – be it personal or professional – is at once a sociopolitical positioning, and a judgement of individual worth.

As a way of concluding this overview I will now briefly summarize the primary takeaways with regard to speechwriters and their work. First, while their workplace communicative practices are certainly subsumed under the all-encompassing umbrella of institutional discourse, speechwriters are invested in establishing a distinct community of practice which orients towards unique specialization and professional worth. Second, these parameters of ingroup belonging partly entail shared claims to prestige and power – indeed, speechwriters are wordsmiths, and as such are especially high-end or “elite” language workers. Third, this sort of metalinguistic self-stylizing is integrally connected to neoliberal rhetorics pertaining to (inter)personal reflexivity and meritocratic success; a primary component to speechwriters’ status production is rooted in a semiotic ideology which frames their particular sort of linguistic skill and knowledge as distinctly valuable. Ultimately, my aim in marrying these rather disparate strands of scholarship is not only to make sense of the ways in which professional discourse communities coalesce but also to determine how their metalinguistic activity serves to establish their symbolic and material worth. In the end, certain kinds of words and work have value in the (linguistic) marketplace – and according to speechwriters, theirs certainly do.

1.3 Speechwriting: History and Scholarly Engagement

While speechwriting has been neglected by applied linguists and discourse analysts, it is an ancient rhetorical practice and political strategy that has been documented throughout history from a variety of academic perspectives. As several others have observed, records of speeches ghostwritten for Greek philosophers and Roman emperors abound (e.g. Einhorn Reference Einhorn1982; Kjeldsen et al. Reference Kjeldsen, Kiewe, Lund and Barnholdt Hansen2019); Duffy and Winchell (Reference Duffy and Winchell1989) assert that the practice “emerged virtually at the same time that rhetoric became a study” (102). Likewise, speechwriting in the time of the ancients was considered a distinct art. Bruss (Reference Bruss2011) notes that a talented “logographer” such as the Athenian speechwriter Lysias, for example, was admired for “lifelike and believable portrayals” of his clients – his speeches were described as “more carefully composed than any work of art” (Lysias 8, as cited in Bruss Reference Bruss2011: 174). Notably, however, rhetorical skill does not equate with oratorial expertise, and as such even in ancient times speechwriters remained behind the scenes in order to preserve the authenticity of their speakers. And indeed, as Bruss also observes, their discursive accomplishment of invisibility (i.e. capturing the voice of the client) is what ultimately solidified their success as logographers.

Despite its prominent historicity, academic literature on speechwriters is markedly lacking, especially in terms of deep theoretical/analytical engagement. Kjeldsen, Kiewe, Lund, and Barnholdt Hanson’s (Reference Kjeldsen, Kiewe, Lund and Barnholdt Hansen2019) recent book Speechwriting in Theory and Practice is somewhat of an exception, and as the broadest and most thorough academic volume published on speechwriting to date it is worth reviewing here in some detail.

The authors, all scholars of rhetoric and communication, spend considerable time attending to “speech” as a genre. They define it as “a physical and situational event unfolding in a specific sphere of time and space” (10, my emphasis); it is therefore embodied performance, and importantly, dependent on a distinct hierarchy of participants (i.e. the speaker talks, and the audience listens). In establishing the complexity of a speech as a multimodal event, Kjeldsen and colleagues point out an important quality of speechwriting nowadays – in contrast to those of antiquity, today’s mediated/mediatized speeches travel to much wider audiences (I elaborate on this point further in Chapter 3). In this regard, much of their book seems to be dedicated to teaching practitioners how to write and work successfully under these contemporary conditions. They include chapters titled “Writing for the Eye: Pictures, Visions and PowerPoint,” as well as “The Functions of Speechwriting in Contemporary Society” and a largely instructional final chapter called “The General Steps in the Speechwriting Process.” Thus, although Kjeldsen and colleagues do engage with the history and various theoretical dimensions to speechwriting, the volume serves more as a how-to for “aspiring speechwriters” (their words, from the back cover blurb).

These things aside, one of the merits of Kjeldsen and colleagues’ approach is their research emphasis on speechwriting in non-US American political contexts (see also Harris Reference Harris1964; Schäfer and Keel Reference Schäfer and Keel2015). Indeed, academic literature is largely dominated by US perspectives, and almost entirely by Western ones (but see Acheoah’s Reference Acheoah2020 paper on speechwriting and oratory in Nigeria for a notable exception). In the authors’ chapter on genre they divide the practice into three broad categories: 1) American presidential politics; 2) European politics; and 3) business and organizational speeches. These subsections reflect the overall bent in scholarship towards speechwriting for the US presidency in particular, an area of scholarship which I will attend to in a moment. What surfaces across these genres, however, is that much of the same issues persist. Key concerns include speechwriters’ access to their “principals” (the professional term used to describe the elected official, e.g. Medhurst Reference Medhurst, Ritter and Medhurst2003); the various constraints in the speechwriting process (including collaboration input; e.g. de Jong and Andeweg Reference De Jong, Andeweg, van Haaften, Jansen, Jong and Koetsenruijter2011); speechwriters’ roles as wordsmiths and/or policy-makers (e.g. Neumann Reference Neumann2007); ethics (e.g. Bormann 1960); and lastly, authenticity and style (e.g. Bruss Reference Bruss2010).Footnote 1

Although research on speechwriting in both Europe and the US has focused on rather predictable themes, Kjeldsen and colleagues determine that the actual production of speeches differs depending on country, administration, professional sphere, and so on. They compare various case studies of speechwriting processes in political contexts – one each from Germany and Denmark, along with a handful of examples from US presidents. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the mechanics of speech production are dependent on the preferences of each elected official or particular governmental organization. It is common, for example, for a speech to be written collaboratively by a team of writers for one prime minister (or president), but by a single staff member for another. Likewise, a writer might begin their assignment by working from a list of ideas prepared by the principal, from a technical brief, or simply from their individual knowledge of the upcoming occasion. Throughout the drafting process, speechwriters receive input from a variety of parties – some internal, some external – and work on merging wordsmithery (as well as speaker style) with these policy-orientated demands. As my analysis reveals later on, this is no easy task, and it is fraught by issues of institutional power; Kjeldsen and colleagues note that the speechwriter in their Danish ministry example is especially low on the hierarchical chain of command and begrudgingly makes revisions to a speech that are described as “not debatable” (107). To be sure, all speechwriters experience this sort of disappointment in their work, but it seems that some employers (government and otherwise) are more flexible than others. Ultimately, Kjeldsen and colleagues’ brief exploration of speech production practices reveals the necessity of qualitative, ethnographic methods in collecting and analyzing speechwriting data.

In this regard, interviewing has been the primary approach to studying speechwriters in academic literature. Scholars of speech and communication have published numerous conversations with prominent US American speechwriters (e.g. Benson Reference Benson1968; Smith Reference Smith1976; Einhorn Reference Einhorn1988; and Duffy and Winchell Reference Duffy and Winchell1989), but interestingly, rarely do they analyze these discursive accounts. To her credit, Einhorn (Reference Einhorn1988) summarizes the contrasting perspectives represented by her three informants, and Duffy and Winchell (Reference Duffy and Winchell1989) offer a rather eloquent introduction which serves to frame a subsequent transcribed conversation between various practitioners. But what is most evident is a distinct lack of theoretical and analytical engagement with the work that speechwriters accomplish day-to-day. Indeed, much of the early literature is markedly descriptive – researchers essentially allow informants to document what exactly they do, and how they themselves view this work, but little else. The more recent work of Kristine Bruss (Reference Bruss2010, Reference Bruss2011), however, departs from this trend. She interviews two very different speechwriters – one, Steve LeBeau, worked for the (in)famous professional wrestler-turned-Governor of Minnesota Jesse Ventura, and the other, Alan Perlman, holds a PhD in linguistics and wrote speeches for executives of General Motors and Kraft throughout the 1980s and 1990s. I will document insights from each of these practitioners in turn.

Bruss’s (Reference Bruss2010) case study highlights the uniqueness of Jesse Ventura as a principal, and the struggles LeBeau faced in writing for an elected official who (very) publicly disparaged political rhetoric; like Donald Trump’s claims during the 2016 election, Ventura was known for his spontaneous talk and lack of prepared speeches. Bruss’s focus on LeBeau as a practitioner is therefore an interesting example of a rather atypical speechwriting situation. Nevertheless, while LeBeau admits the difficulties in writing for a speaker who often strays from the script (what he calls “Jesse-talk”), in terms of general processes and professional practices his work is strikingly similar to that of other political speechwriters. Even his background in theater and entertainment is a common refrain; as Bruss observes, this sort of orientation to theatrical performance and showmanship allows speechwriters to fully develop ethopoeia, or the art of characterization. This ability to capture the essence of a speaker in order to produce an authentic “voice” is key for all successful speechwriters, but importantly, practitioners differ in terms of how systematic they are in achieving this goal.

While many speechwriters describe their process as intuitive (see Chapter 2), Bruss’s (Reference Bruss2011) interview with Alan Perlman outlines a very specific method for characterizing the speaker. His three-part system is organized according to verbal style, (the client’s “fundamental” manner of speaking, p. 168); rhetorical techniques (their “preferred ways of making a point,” p. 169); and intellectual character (the client’s knowledge of the outside world). This formulaic approach is effective because it produces what Bruss deems “faithfulness” to type, individual, and nature – the speechwriter is not just concerned with capturing a principal’s particular cadence, mannerisms and argument strategies but also with producing knowledge that the speaker could believably possess. Bruss (Reference Bruss2011) concludes that “The skillful ghost is a master of mimesis, attuned to character types, the distinctive characteristics of individual speakers, and conversational style. The result is the seemingly natural, artless expression of character, an aesthetic ideal valued by practitioners in ancient as well as contemporary times” (177). Thus, what Bruss’s research reveals is how two very different kinds of speechwriters, working for two very different kinds of speakers, orient to similar professional expectations and goals. The way they describe their work practices may differ slightly, but the end result is ultimately the same: a well-crafted speech and an invisible speechwriter.

This sense of invisible authorship has been a point of academic (and public) intrigue most often in the realm of presidential studies, a subdiscipline of history and political science. Importantly, the perspective here tends to be firmly president-centered. As Schlesinger (Reference Schlesinger2008) puts it, speechwriting “is a unique lens through which to view the [US] nation’s modern chief executives” (4). In other words, research in presidential studies does not aim to understand speechwriters, but rather, as the name suggests, to understand US presidents. That said, scholars in this area have documented valuable insights pertaining to 1) policy versus wordsmithery; 2) authorship versus ownership; and 3) access/relationship to the principal. I briefly elaborate on each of these in what follows.

In the introductory chapter to Ritter and Medhurst’s (Reference Ritter and Medhurst2003) edited volume on presidential speechwriting, Medhurst debunks “ten myths that plague modern scholarship” (3), most of which read as a defense of speechwriters and their practice. In particular, Medhurst emphasizes the historical lineage of speechwriting in the United States, pointing out that George Washington and many other famed presidents received assistance with written work, even if they were not known to employ speechwriters per se.Footnote 2 His tack here is to push back against concerns about the ethics of speechwriting (cf. Seeger Reference Seeger1992) and to establish the practice as fundamental to the US American presidency. Indeed, Medhurst ultimately argues that speechwriting is not “mere wordsmithing,” but is rather a major part of policy-making (13) – elsewhere he describes this process as “evolutionary invention” (Medhurst Reference Medhurst1987: 247):

What starts as a change of terminology in draft #2, becomes a change of verb form in draft #3, then a rearrangement of sentences in draft #4, then part of a new paragraph in draft #5, necessitating in draft #6 a new illustration which, itself, necessitates further stylistic changes until by the final draft the original sentiment may be eliminated entirely.

Thus it is in the revision process where Medhurst sees the bulk of policy-making by speechwriters. While their work appears to be simply language-centered, these microlinguistic practices can have large, material impacts. Furthermore, and as Schlesinger (Reference Schlesinger2008) also observes, putting policy into words helps raise new questions, expose potential weaknesses, and “set the terms of the international debate” (129). Speechwriters are therefore important members of staff who often determine not only the tone but also “the substance of a Presidential speech” (Smith Reference Smith, Ritter and Medhurst2003: 146). Thus, although I use the title “wordsmith” to convey speechwriters’ high-end status and skill, it seems that for them the term is not necessarily a compliment – it does not adequately capture the extent of their language work, nor their sense of ownership over the material they produce (see also Chapter 2).

The question of who the speech belongs to is one that has not only been addressed in academic literature but also infiltrated politics; President Nixon famously accused President Kennedy of being a “puppet who echoed his speechmaker” (Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger2008: 141), essentially claiming that it was Ted Sorensen who authored and owned JFK’s rhetoric.Footnote 3 As several presidential studies scholars have argued, this perspective – which was certainly a political ploy given Nixon’s own use of speechwriters – drastically oversimplifies the speechwriter-speaker relationship (e.g. Medhurst Reference Medhurst, Ritter and Medhurst2003). As Schlesinger eloquently puts it,

There is a distinction between authorship of a speech and ownership. Ferreting out the specific author of a memorable line can be an interesting exercise (enough to write whole books about), though often a fruitless one. But of greater importance is not who first set specific phrases to paper, but the care with which a president adopts them as his own, and how well those words express that president’s philosophy and policies. The president must ultimately have ownership of his words – for good or ill – not only because he will be held responsible for them, but because to suggest otherwise risks the possibility that he may not.

Here, Schlesinger highlights two important aspects to presidential speechwriting. First, he notes the speechwriter’s expertise in converting “the president’s philosophy and policies” into rhetoric; because this work goes beyond simple wordsmithery, the actual authorship of language becomes secondary (see also previous paragraph). Second, no matter whether the speechwriter produces certain words or phrases, it is the president who is held responsible, and who is therefore owner (I discuss this further in Chapter 2). Although this latter point is a widely-held public perspective, many presidential speechwriters take pains to explicitly mitigate their authorship – as part of the moral code of speechwriting (e.g. Benson Reference Benson1968), or out of respect for their particular principals (e.g. see Chapel Reference Chapel1978; Duffy and Winchell Reference Duffy and Winchell1989). There are instances in which the behind-the-scenes workings of this sort of text production have been exposed, but they are relatively controversial (see Schlesinger’s discussion of the George W. Bush writing team, especially). Ultimately, presidential speechwriters seem to tread carefully when it comes to talking/writing about their participation in speech making, and indeed, their reflections typically focus on their collaboration with their respective presidents. This brings me, lastly, to the speaker–speechwriter relationship.

Various scholars have observed that access to the principal is integral for speechwriters (e.g. Seeger Reference Seeger1992), and it is true that presidents who are respected for their oratory abilities are often known to work very closely with their speechwriters (President Obama and Jon Favreau, for example). In the afterword to Ritter and Medhurst’s (Reference Ritter and Medhurst2003) edited volume, Medhurst (Reference Medhurst, Ritter and Medhurst2003) writes

… the most successful relationships between writers and principals have been characterized by more or less direct access at three crucial moments: the moment of ideational conception when the principal decides what he wants to say, the moment of compositional closure when the speechwriter is close to producing what she or he considers to be a “final” draft, and the moment of administrative imprimatur when the other involved parties – cabinet secretaries, agencies, bureaus, and the president’s inner circle – “vet” the speech as drafted. Speechwriters who are directly involved at these three crucial moments tend both to be more satisfied with their work and also, I believe, to produce better work.

Medhurst’s position is based partly on his assessment of the relationship between John F. Kennedy and Ted Sorensen – the notoriously collaborative nature of their speech making process proved to be highly successful for the president’s rhetoric and overall reputation. Sorensen himself is quoted in Schlesinger’s (Reference Schlesinger2008) White House Ghosts as saying, “there’s a tremendous advantage for a speechwriter to know his boss’s mind as well as I did” (103). Arguably, the better you understand the inner workings of your principal, the more effectively you can write for them. A slightly different situation, however, can be seen in the case of Ronald Reagan’s writing team. Although the speechwriters (Peggy Noonan being the most famed of the group) were not known as having the same level of intimacy with their boss as the Sorensen–FK dyad (cf. Muir Reference Muir, Ritter and Medhurst2003), they seemed to be given access to President Reagan during Medhurst’s “crucial moments” and were especially involved during draft “vetting,” as he puts it. According to Muir (Reference Muir, Ritter and Medhurst2003), this is why Reagan’s speechwriting department saw themselves as “the soul of administration” – and also why the president’s “bully pulpit” was such a public success (203, 194). Thus, although speechwriting practices across presidential administrations vary, the literature reveals that close collaboration is key for the production of high-quality, “authentic” rhetoric (see Mapes Reference Mapes2021a). In this way, the goals and structure of presidential speechwriting practices seem to rather closely resemble those of professional speechwriting more generally.

In summary, this overview of academic literature on speechwriting reveals that although the profession/practice has been addressed by scholars of communication, rhetoric, and history, there exists a marked lack of deep theoretical and analytical engagement with speechwriters’ daily linguistic labor. It is certainly interesting to hear how they describe their craft in interviews, to compare their processes across different international/professional contexts, and of course, to examine their role in presidential politics – all of which speaks to the general intrigue of their behind-the-scenes work. But as real arbiters of wordsmithery, their linguistic expertise can be a resource for understanding not only the important ways language can be strategically produced, crafted, and stylized, but also how this kind of creative labor is explicitly valued and commodified in neoliberal markets. This is precisely the issue I address throughout the rest of this book. With this in mind, I turn now to my research specifically, and to the data that inform my analytical focus.

1.4 The Project

My research on professional speechwriters has been part of a larger research program called Elite Creativities, which investigated the high-end language work of various understudied professions (see Droz-dit-Busset Reference Droz-dit-Busset2022 on social media influencers as modern-day copywriters; Portmann Reference Portmann2022 on UX writers; and Thurlow and Britain Reference Thurlow, Britain and Thurlow2020 on dialect coaches). In addition to collecting secondary sources related to each profession (e.g. memoirs), as well as “language biography” interviews following Preston’s (Reference Preston1996) focus on folk linguistic accounts, we aimed to conduct a “production chain analysis” via extended, ethnographic fieldwork in the workplace, which would have allowed us to track wordsmiths’ actual production of deliverables (in my case, speeches). However, from the beginning of my data collection – which commenced in Autumn 2019 – I struggled to gain access to speechwriters (and to political speechwriters especially) and even found soliciting interviews to be a challenge. As a result, before Covid-19 emerged as a global crisis I had already begun reimagining my approach, envisioning it as a rather more eclectic but nonetheless holistic documentation of speechwriters (in general) and their work. Thus, my data collection and methodological procedures closely follow the principles of “linguistic ethnography” as defined by Rampton and colleagues (Reference Rampton, Tusting, Maybin, Barwell, Creese and Lytra2004). Before elaborating on the specifics of this approach, however, I will document the various genres of data I draw on for analysis in each substantive chapter.

1.4.1 Professional Speechwriting Course

At the beginning of my research I was interested in documenting the specific avenues through which speechwriters learn to do their jobs – as such, in September 2019 I paid to participate in a three-day Professional Speechwriting class that was offered by a university based in Washington, DC.Footnote 4 I emailed the instructor, Matt, beforehand, asking to enroll, and explained that I was a researcher interested in speechwriters and their work.Footnote 5 He welcomed me readily, and I traveled to Washington from Bern, Switzerland, two weeks later, several days in advance of the first day of class. However, and as Heller (Reference Heller, Wei and Moyer2009) notes, ethnography as a methodological approach is uniquely unpredictable: the evening before the course began I became terribly ill and was forced to stay home all of the next day. As such, I missed an entire day’s worth of lectures and workshopping. I feel compelled to note here how devastating this was, given the struggles I had experienced with data collection. Fortunately, however, all students were given access to the PowerPoint materials used across the entirety of the course, and I was also able to ask Matt specific questions about Day 1 content in our recorded interview. As such, I attended class on Days 2 and 3 as a full participant-observer. I took detailed field notes, occasionally responded to prompts or questions from the instructor, and interacted with the fourteen other students during breaks. I learned that most participants worked in communications for the US military – Matt informed me that this is the norm for these classes (which at the time were offered once a month). At the end of the class on Day 3 I asked whether any of the students were interested in being interviewed about their work, and one woman (Julie) approached me. Her interview, and my interview with Matt (which occurred after class on Day 3), are included in Table 1.1 (pp. 25–26). These speechwriting class data inform my analysis most prominently in Chapters 2 and 5.

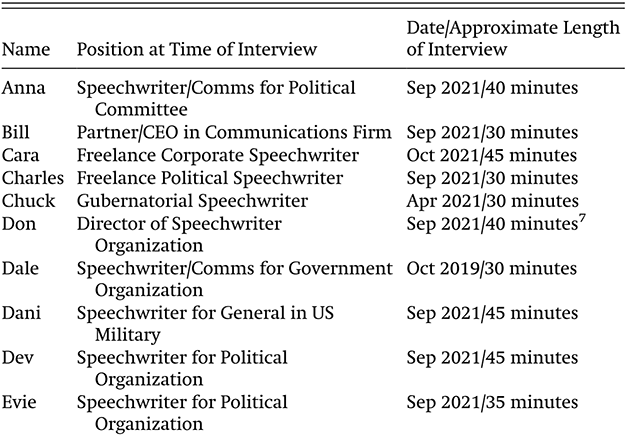

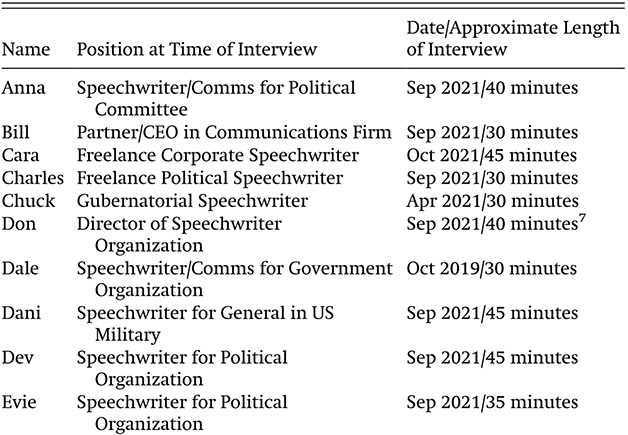

Table 1.1Long description

The table consists of three columns: Name, Position at Time of Interview, and Date or Approximate Length of Interview. It reads as follows. Row 1: Anna, Speechwriter slash Comms for Political Committee, September 2021 slash 40 minutes. Row 2: Bill, Partner slash Chief Executive Officer in Communications Firm, September 2021 slash 30 minutes. Row 3: Cara, Freelance Corporate Speechwriter, October 2021 slash 45 minutes. Row 4: Charles, Freelance Political Speechwriter, September 2021 slash 30 minutes. Row 5: Chuck, Gubernatorial Speechwriter, April 2021 slash 30 minutes. Row 6: Don, Director of Speechwriter Organization, September 2021 slash 40 minutes superscript 7. Row 7: Dale, Speechwriter slash Comms for Government Organization, October 2019 slash 30 minutes. Row 8: Dani, Speechwriter for General in United States Military, September 2021 slash 45 minutes. Row 9: Dev, Speechwriter for Political Organization, September 2021 slash 45 minutes. Row 10: Evie, Speechwriter for Political Organization, September 2021 slash 35 minutes.

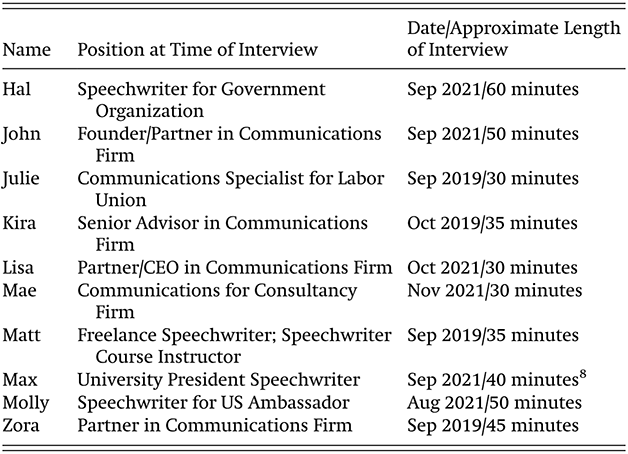

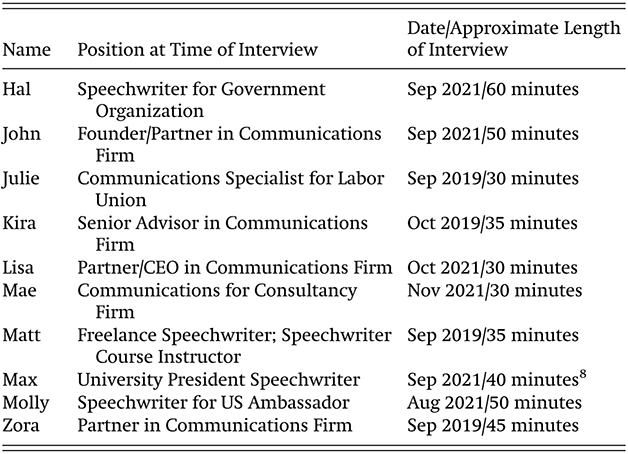

Table 1.1 (cont.)Long description

The table consists of three columns: Name, Position at Time of Interview, and Date or Approximate Length of Interview. It reads as follows. Row 1: Hal, Speechwriter for Government Organization, September 2021 slash 60 minutes. Row 2: John, Founder slash Partner in Communications Firm, September 2021 slash 50 minutes. Row 3: Julie, Communications Specialist for Labor Union, September 2019 slash 30 minutes. Row 4: Kira, Senior Advisor in Communications Firm, October 2019 slash 35 minutes. Row 5: Lisa, Partner slash Chief Executive Officer in Communications Firm, October 2021 slash 30 minutes. Row 6: Mae, Communications for Consultancy Firm, November 2021 slash 30 minutes. Row 7: Matt, Freelance Speechwriter; Speechwriter Course Instructor, September 2019 slash 35 minutes. Row 8: Max, University President Speechwriter, September 2021 slash 40 minutes superscript 8. Row 9: Molly, Speechwriter for United States Ambassador, August 2021 slash 50 minutes. Row 10: Zora, Partner in Communications Firm, September 2019 slash 45 minutes.

1.4.2 Secondary Sources

While attempting to solicit more contacts in the speechwriting community I began reading The Speechwriter: A Brief Education in Politics, a memoir by Barton Swaim (Reference Swaim2015), to expand my knowledge on the profession. I chose this book because it was the first title to pop up during a cursory Google search, but eventually I added two others to my list of secondary sources: What I Saw at the Revolution: A Political Life in the Reagan Era by Peggy Noonan (Reference Noonan1990) and Thanks, Obama: My Hopey, Changey White House Years by David Litt (Reference Litt2017). Both of these latter two texts were mentioned to me in interviews with speechwriters, as was The Political Speechwriter’s Companion: A Guide for Writers and Speakers by Robert A. Lehrman and Robert Schnure (second edition, Reference Lehrman and Schnure2019). As is perhaps clear from their titles, the presidential (and gubernatorial in Swaim’s case) speechwriter memoirs are eloquent reflections on each author’s experiences writing for (in)famous elected officials, whereas the fourth title I mentioned can be considered more of a training manual. In any case, I read each text closely and took detailed notes for comparison with other speechwriter accounts. Additionally, early on in my research I discovered a video-recorded Oxford Student Union address delivered by Jon Favreau, the former speechwriter for President Obama. Favreau’s speech, titled “Life as Obama’s Speechwriter,” is approximately seventeen minutes long and followed by forty-five minutes or so of discussion with the audience. I archived the recording, which I then loosely transcribed for analysis. Altogether, these secondary sources were collected and analyzed predominantly during 2019 and 2020, alongside my interview data. I rely on extracts/insights from these data in all my substantive chapters.

1.4.3 Interviews

As I mentioned a moment ago, the Elite Creativities researchers relied on interviews as a primary data source partly as a means of prioritizing the language expertise of non-linguists; this approach attempts to center what Preston (Reference Preston1996) calls the “folk linguistic awareness” of lay people (see also Kramsch Reference Kramsch2009 on “language memoirs”). In this regard, my interviews engaged with US American speechwriters’ professional practices, career trajectories, and education, but also explicitly elicited metadiscursive commentary. I selected my research site (Washington, DC/the United States) because I thought it was the location where I had the best chance of accessing a speechwriting community. As a US citizen and former DC resident, I had pre-established connections that I hoped would lead me to practicing speechwriters. I did, however, end up conducting an interview with one woman working in the Canadian government and with one man working in the Swiss government. Both of these interviews were excluded from the final dataset, but their discourse reflected similar themes to the ones I identified in the US American context.

Although I distributed the list of interview questions to each informant beforehand (along with a consent form), the interviews themselves were semi-structured: largely organic and conversational in nature (see appendices for these documents). Importantly, and following Perrino (Reference Perrino, Perrino and Pritzker2022), I approached these interviews as interactional events which are co-produced, contextualized reflections of interlocutors’ social selves. I did not simply read down the list posing each question in turn but rather began all my interviews by asking speechwriters to tell me about how they came to do this sort of work. Our conversations unfolded naturally from this point. If we encountered a lull, I would consult my list and ask them to comment on a particular question or issue. Overall, at the end of each interview I felt like the participant had at least touched on every question, and so I was comfortable relying on this rather ethnographic-cum-eclectic way of collecting interview data.Footnote 6

I will reiterate here that it was very difficult for me to find participants. The (political) speechwriting community is hard to access because of the fast-paced nature of their work (see p. 53) and their proximity to high-powered elected officials and other leaders. I was relying (rather naively) on word of mouth to make contacts, and before enrolling in the Professional Speechwriting course I was simply unsuccessful. Although in 2019 I was put in touch with several people who showed initial interest, it wasn’t until I came to Washington, DC, that September that I was able to speak with any speechwriters. Around this time I recorded and transcribed five interviews (three in person, two over the phone); these early interviews grew mostly out of my course contacts, and one other well-connected friend in the area. Unfortunately, however, the Covid-19 pandemic closely followed this round of fieldwork and my research came to somewhat of a halt – it felt like an odd time to reach out to people asking for favors when all our lives were so incredibly altered (and indeed, lost or at least threatened). In 2021 my interviews picked up again, but it wasn’t until September of that year, when I returned to Washington, DC, that I was able to collect the bulk of my data. I acquired these additional participants by reaching out to a few acquaintances in the area – these contacts combined with snowball sampling resulted in a total of nineteen interviews (with twenty total participants) by the end of my fieldwork in November.

My interview participants are organized in Table 1.1 alphabetically, according to each speechwriter’s pseudonym. I have included the position or title each one held at the time of their interview, as well as the date and approximate length of our conversation. Notably, only three participants (out of twenty total) had zero experience in politics and/or government – most of my interviewees had worked in multiple positions throughout their careers, and many of them as expressly political speechwriters. The three outliers include Don, the executive director of the Speechwriter Organization (see next section); Dani, a speechwriter in the US military; and Max, the speechwriter for a prominent university president.Footnote 9 In terms of demographics, ten speechwriters were women and ten were men; three were Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC); and the ages of participants ranged from early twenties to late fifties. Most interviews were around 30 minutes long, though several went longer. Ultimately, I collected over 12 hours of audio-recorded interview data (approximately 735 minutes), all of which I transcribed using a combination of software and manual methods.Footnote 10 I draw on these interviews heavily for my analysis in each substantive chapter.

1.4.4 Video-Recorded Meeting

Various studies in institutional discourse have documented workplace meeting interactions via audio and/or video footage – Christina’s Wasson’s (e.g. Reference Wasson2006) work here is of particular interest, as her extended fieldwork at prominent corporations resulted in a large corpus of ethnographic, textual, interview, and interactional data related to this common institutional practice (see earlier discussion on p. 7). Interestingly, she was also able to document the earlier days of virtual meetings, which were largely facilitated by teleconference and shared computer screen technology. Nowadays, of course, virtual meetings over Zoom and other applications are commonplace, and I was fortunate to gain access to one such gathering during my fieldwork.

Early in my research process I was put in contact with the executive director of the Speechwriter Organization, a membership-based group of communications professionals that is designed to create networking opportunities, collaboration/inspiration, and learning/training resources. Don invited me to attend one of the organization’s monthly virtual “happy hours” in which members gather to discuss a number of topics related to the profession. My presence at the meeting and brief project description were advertised by email; in the end, the happy hour comprised five speechwriters, me, plus the executive director and chief operations officer (both of whom were mostly observers during our conversation). The participants were mostly freelance speechwriters (which is common for the Speechwriter Organization), although the conversation also included Max and Dani (see again Table 1.1). According to my email exchange with Don, none of the participants knew each other well, and they had only interacted in the context of these monthly happy hours.

The meeting was conducted using the platform GoToMeeting on a Friday evening in September 2021 and was about one hour long. I was able to video-record approximately thirty-five minutes of the gathering, which I then audio-transcribed for analysis.Footnote 11 Our conversation was guided by a few general questions I raised related to creativity, ownership, and mastering the “voice” of a client. For my purposes in the book, I identified two extracts of methodological and analytical interest which I transcribed multimodally – I focus on these data in Chapter 5.

1.4.5 Speech Drafts and Other Texts

As I mentioned earlier, alongside metadiscursive accounts of speechwriters’ work I was interested in documenting the actual production of deliverables (e.g. Macgilchrist and Van Hout Reference Macgilchrist and Van Hout2011). Thus, in September 2021 I began to ask my participants whether they might be willing to share drafts of their work so I could track the so-called “life” of a speech. Although many expressed interest verbally, only three speechwriters (Anna, Evie, and Molly) ended up providing these sorts of materials, which included outlines or notes from speech planning meetings, first/second drafts with handwritten notes or tracked changes, and then final versions. For some speeches I was also able to find a video of their delivery, which I also archived for analysis. Ultimately these written/audiovisual materials comprise twenty-one total texts, pertaining to nine different speeches. I attend to two of these speeches in detail in Chapter 3.

1.4.6 George W. Bush Speech Texts

Lastly, and at the suggestion of one of my interview participants, I decided to look into obtaining speech drafts and texts from presidential archives. I was especially interested in President Obama’s materials after analyzing Jon Favreau’s Oxford Student Union address, but was informed by a staff member that his library would not be open to the public for some time, given that they were still processing his documents. In fact, the most recent texts available were those of George W. Bush, and so I simply chose to focus on those.

My data collection began with a series of correspondence with various presidential library and National Archives and Records Administration employees. Eventually a staff member of the George W. Bush Library and Museum in Dallas, Texas, identified materials that might be of interest to me, but recommended I peruse the website to see what other records were available for request. As I was not concerned with the dates or topics covered by any one file in particular, I ultimately settled on what was labeled as SP (Speeches) Box 3 – the description included the phrase “speech drafts” and seemed to contain files that would be the most straightforwardly related to my research. I was charged $442 for this “box” of speeches (which was reimbursed by the Elite Creativities project grant, of course). I did know I would pay a fee for the files to be digitized and sent to me, but I must say I was a little surprised by the amount! In any case, I received everything quite quickly once the fee had been paid and I archived the files accordingly.

Box 3 contained thirteen separate PDF documents, each of which comprised a variable number of scanned texts (ranging from 1 to 89 pages in length). Overall the files amounted to 549 digital pages – most of which, unfortunately, were of little use to me. As it turns out, almost all speech production texts (i.e. drafts) were redacted from the final materials, leaving behind only official lists of what had been removed from Box 3 before it was made available to me. Of course, given my focus on speech authorship this was in and of itself interesting, but it was nonetheless fairly disappointing. I will elaborate more on Box 3 and the various texts involved in presidential speech production in Chapter 3.

In sum, the various data I collected between 2019 and 2022 together comprise a robust corpus of written, spoken, and visual material pertaining to contemporary professional speechwriting practices in the US. Accordingly, and as a means of illustrating how I make sense of these distinct but connected genres of data, I turn now to my general method and analytical approach.

1.5 Method: (Critical) Discourse Ethnography