The story of impressionism in English literature might be said to begin with Arthur Symons. As we have seen, he was not the first to suggest the idea: as early as 1883, in a review of The Little Schoolmaster Mark by J. H. Shorthouse, Vernon Lee had described a prose style which resembled, ‘if I may use an artist’s word’, a painter’s ‘impressionism in execution’; and in 1892 the Pall Mall Gazette praised the Goncourts’ sixth instalment of their Mémoires de la vie littéraire (1886–96) for its ‘touch of unconscious literary impressionism, if the phrase may stand’.1 But in each case there is a hesitation, an uncertainty that the term will ‘stand’ in its new verbal context. Each reviewer, moreover, uses the word in passing, in a manner which might itself be described as ‘impressionistic’ – which is to say, subjective and unsystematic. Symons, by contrast, was concerned above all with systems, schools and movements, and with telling stories about them. One such grouping is what he calls, in his essay of the same title, ‘The Decadent Movement in Literature’, of which ‘the Impressionists’ are said to form the most prominent branch. Published in Harper’s Magazine in 1893, the essay marks the first serious effort by an anglophone writer to define an impressionist style, and in this sense the tale of literary impressionism belongs, originally, to Symons.

Yet Symons rarely features in discussions of the subject, and his wider reputation has continued to be defined in relation to his major critical work, The Symbolist Movement in Literature (1899), which has overshadowed the significance of his other writings.2 In this chapter I return to the definitions of impressionist style outlined in ‘The Decadent Movement’, which I consider both as resources for Symons’s poetry and as instructively ambiguous early articulations of the idea of literary impressionism itself. The particular concern of my initial discussion is with the language of sanity and wholeness (or their absence) in which the essay’s conception of impressionism is grounded, and with tracing its theoretical roots in contemporary French writing, Whistlerian aesthetics and Pater’s philosophy of impressions. My attention then turns to the curiously divided fashion in which this critical synthesis reshaped Symons’s verse. I argue that the version of impressionism defined in ‘The Decadent Movement’ – a ‘diseased’ style preoccupied with the ‘unstable’ and the fragmentary, and with the breaking open of ‘rigid’ or outworn forms (‘DM’, pp. 170–1) – provided the rationale for some of Symons’s most innovative experiments with lyric form during the 1890s, which in turn furnished les imagistes with models for their own poetic renovations in the decades that followed. As I go on to suggest, however, the poems’ absorption in momentary and subjective impressions might also be seen to establish the limitations of a theory which seemed itself to become unstable in Symons’s later writings, particularly those which he composed in the years prior to his crippling mental collapse in Venice in 1908. What emerges from my discussion is a portrait of a form that is self-consciously preoccupied with the fragmentary, but which seems, eventually, to pull apart under the pressure of its own impulse to fracture.

Magnified by the mythos of the so-called Tragic Generation, the intrigue surrounding Symons’s breakdown has obscured the extent to which mental pathology was itself his most enabling critical motif, as well as a subject which his overlapping theories of decadence and impressionism consciously explored.3 In fact, those theories were first provoked into being by an accusation of insanity. In an article written for the Century Guild Hobby Horse in 1892, the poet and critic Richard Le Gallienne had suggested that ‘literary decadence consists in the euphuistic expression of isolated observations’ and, further, that ‘any point of view [that] ignores the complete view, approaches Decadence’.4 ‘Disease’, for instance, ‘is a favourite theme of décadents [but] does not in itself make for decadence: it is only when it is studied apart from its relations to health, from the great vital centre of things, that it does so’.5 Likewise:

To notice only the picturesque effects of a beggar’s rags, as Gautier; the colour scheme of a tippler’s nose, like M. Huysmans; to consider one’s mother merely prismatically, like Mr. Whistler – these are examples of the decadent attitude. At bottom, decadence is merely limited thinking, often insane thinking.6

‘The Decadent Movement’ was written partly in response to Le Gallienne, but offers its rebuttal indirectly, without mentioning the earlier article. Indeed, there is a sense in which its indirectness is its rebuttal: exclusively dedicated to ‘the maladie fin de siècle’ – that ‘new and beautiful and interesting disease’ which Symons considers ‘apart from its relations to health’ – the essay not only articulates a defence of decadence, but also pointedly assumes the perspective that Le Gallienne had called insane (‘DM’, p. 169).

The gambit is clarifying in two ways, illuminating the relationship between the language of disease and Symons’s conception of decadence, and bringing into sharper focus his sense of how that idea related to the wider literary culture of the fin de siècle. In Symons’s characterisations, decadence was a diffuse and amorphous phenomenon, too varied and complex to be exactly defined, but composed of two main branches. As he remarks, ‘The latest movement in European literature has been called by many names, none of them quite exact; [but] taken frankly as epithets which express their own meaning, both Impressionism and Symbolism convey some notion of that new kind of literature which is perhaps more broadly characterised by the word Decadence’ (‘DM’, p. 169). In Symons’s later book-length study The Symbolist Movement in Literature, the emphasis will be on the rarefied atmospheres of symbolism, which he associates with the ‘elliptical’ opacity of Stéphane Mallarmé and the aristocratic detachment of Villiers de l’Isle-Adam.7 In the earlier essay, however, his preference is for the emotional intensity of impressionism, which finds expression in the jagged confessional prose of the Goncourts and the dissolute lyricism of Paul Verlaine. Both wings of the decadent movement seek ‘the very essence of truth’ – one renders ‘the truth of appearances’, the other divines ‘the truth of spiritual things’ (p. 170) – but if decadence is insane for ignoring the complete view, then impressionism in particular, which Symons defines as a ‘new way of seeing things [that has] never sought “to see life steadily” or “see it whole”’, is both its primary mode and the one adopted by his essay (p. 172).

In a reciprocal fashion, the essay’s embrace of disease and disequilibrium gives an indication of what this impressionism looks like, both in its manner of viewing the world and in its formal contours. The Goncourts’ ‘vision has always been somewhat feverish’ – ‘“We do not hide from ourselves that we have been passionate, nervous creatures, unhealthily impressionable”, confesses the Journal’ – but their ‘marvellous style’, Symons suggests, derives from their ‘morbid intensity [in] seeing things and seizing things’, their ‘desperate endeavour [to] preserve the very heat and motion of life’:

What the Goncourts have done is to specialize vision, so to speak, and to subtilize language to the point of rendering every detail in just the form and colour of the actual impression. [T]hey have broken the outline of the conventional novel in chapters with its continuous story, in order to indicate – sometimes in a chapter of half a page – this and that revealing moment, this or that significant attitude or accident or sensation.8

This style may be ‘unwhole’, but its fragmentation is only a symptom of the Goncourts’ ‘endeavour after a perfect truth to [their] impressions’, since a ‘revolt from ready-made impressions and conclusions’ requires the fracture of ‘forms become rigid’ (p. 171). Out of that breakage emerges ‘une langue personelle’ blind to ‘due proportions’, but closer to experience for being so, such that ‘words are not merely colour and sound, they live’ (p. 172). In verse, too, there is a breaking apart of old forms, and the coming in their place of a more vital style: ‘What Goncourt has done in prose’, Symons suggests, ‘Verlaine has done in verse’, ‘inventing absolutely a new way of saying things, to correspond with that new way of seeing things which he has found’ (pp. 172–3). In his Fêtes galantes (1869) and Romances sans paroles (1874), in particular, ‘the poetry of Impressionism reaches its very highest point’, giving expression to ‘the violence, turmoil, and disorder of a life which is almost the life of a modern Villon’ through an ‘exquisite depravity of style [which is] really instinctive’ – its surface so ‘tourmenté’, its language so ‘furiously sensual’, that word and sensation seem almost to fuse (pp. 173–4).

Symons’s emphasis on the living quality of these new ways of seeing and writing is the crucial thing to notice, because it inverts the negative connotations of insanity, so that the sane and the whole become critical categories which seem retrograde and limiting. ‘To see life steadily’ and ‘see it whole’ are phrases borrowed from Matthew Arnold’s 1849 sonnet ‘To a Friend’ (probably Arthur Hugh Clough), ‘whose even-balanced soul’

In its strenuous pursuit of momentary affective states, the version of impressionism defined in Symons’s essay upends the poem’s emphasis on symmetry and even-balance in a way that is deliberately ‘unhealthy’. But, he asks, ‘simplicity, sanity, proportion – the classic qualities – how much do we possess them [in] our surroundings, that we should look to find them in our literature – so evidently the literature of a decadence?’ (‘DM’, p. 170). In a parody of Arnold, Symons connects this new way of seeing with ancient empire of the wrong kind – with the alleged ‘decadence’ of the later Roman Empire, which, in the nineteenth century, was routinely contrasted with the perceived moral and linguistic integrity of the Roman Republic and (as in Arnold’s poem) the earlier Greek Empire.10 Formal idiosyncrasies are then reclaimed as achievements since, in their irregularity, they are said to be more representative of life in a world from which proportion is absent than the ‘classic’ art of antiquity. This explains the predominance of what Symons calls impressionism in ‘The Decadent Movement’, since its broken outlines would seem well suited to an accelerating urban culture of accidents and sensations, of momentary impressions as opposed to steady or whole pictures of events. Contrary to Arnold’s ideals of proportionality and balance, Symons’s impressionists are joined by their feverish sensitivity – their ‘unhealthy impressionability’ – to the violence and disorder of modern life (‘DM’, pp. 172–3). It is a marriage of illness and genius in which the former is said to inflame the surface of the mind, giving it the ‘diseased sharpness of over-excited nerves’ (p. 172), and heightening its susceptibility to the impressions it receives. Symons’s impressionists may be unhealthily impressionable, even unstable, but their discovery of ‘curiosities of beauty [in] quite ordinary places’ is enabled, so the motif implies, by precisely that affliction.11

This receptivity to curious new forms of beauty is the vital link between modernity, disease and the kind of genius ‘The Decadent Movement’ describes, and represents the aptitude which, theoretically at least, redeems the part of disease in that equation. Significantly, it also connects Symons’s essay to an existing current of nineteenth-century writing about impressions. Charles Baudelaire was perhaps the most famous advocate for the idea that ‘the beautiful is always strange’, and his portrait of Constantin Guys, the convalescent ‘Painter of Modern Life’ (1863) who harvests the ‘vividly coloured impressions’ which follow after physical illness, would be one important model for the kind of feverishly hyper-sensitive genius described in Symons’s essay.12 But Symons’s adjustment of the slogan, with its new stress on ‘curiosity’, indicates a more complex theoretical ancestry for the kind of impressionism envisaged by his essay. In particular, it is a mark of Symons’s discipleship to Walter Pater, whose 1876 essay on ‘Romanticism’ not only paid close attention to Baudelaire’s ‘addition of strangeness to beauty’, but also suggested that curiosity was essential to ‘all true criticism’.13 ‘When one’s curiosity is deficient’, Pater argued, ‘one is liable [to] be satisfied with worn-out or conventional types’ and ‘to value mere academical proprieties too highly’, becoming susceptible to what, in the ‘Conclusion’ to his Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873), he described as the ‘facile orthodoxies of Comte, or of Hegel’.14 According to Pater, such ‘abstract theor[ies]’ were irreconcilably removed from the vibrant and ‘unstable’ impressions that wash continually through ‘the narrow chamber of the individual mind’.15 In The Renaissance, therefore, intellectual systems are cast aside: ‘with the passage and dissolution of impressions, images, sensations[,] analysis leaves off’.16 As ‘all melts under our feet’, Pater claimed, ‘he who experiences [his] impressions strongly has no need to trouble himself’ with the issue of their ‘exact relation to truth’.17 The point was not, as Arnold had argued, ‘to see the object as in itself it really is’ and see it whole, but rather ‘to know one’s impression as it really is’, and to discern ‘those more liberal’ intuitive truths which lie beyond the ‘strictly ascertained facts’ about experience.18

Pater’s revision of Arnold’s formula is one in which, as Denis Donoghue remarks, ‘ontology is displaced by psychology’.19 By placing subjective perception at the centre of experience in this way, and urging his readers to be ‘forever curiously testing new opinions and courting new impressions’, Pater seemed to advocate an imaginative replenishment in which life would become a project of continuous aesthetic creation: one in which fancy would usurp fact, and ‘the desire of beauty, the love of art for art’s sake’ would become an ethic in its own right.20 Thus, in his novel Marius the Epicurean (1885), Pater suggested that ‘life in modern London even [is] stuff sufficient for the fresh imagination of a youth to build his “Palace of Art” of’, its ‘brevity’ giving ‘him something of a gambler’s zest in the apprehension [of] the highly coloured moments which are to pass away so quickly’.21 Indeed, in The Renaissance, he aligned this ‘incurable thirst’ after rare and fleeting sensation with the very highest art forms, ascribing to the adolescent Leonardo (who in this respect bears an uncanny resemblance to Baudelaire’s portrait of Guys) an almost compulsive receptivity to impressions of beauty ‘which never left him’: ‘As if catching glimpses of it in the strange eyes or hair of chance people, he would follow such about the streets of Florence till the sun went down.’22 Along with many young men of his generation, Symons interpreted Pater’s notion of an incurable curiosity as a lesson in a particularly intensive kind of aesthetic self-fashioning. He took seriously the injunction, powerfully articulated in Pater’s ‘Conclusion’, to make oneself as sensitive as possible to ‘those impressions of the individual mind to which, for each one of us, experience dwindles down’ – ‘to burn always with this hard, gem-like flame’, ‘gathering all we are into one desperate effort to see and touch’.23 As Symons recalled in his ‘Introduction’ to the 1900 edition of The Renaissance, ‘that book opened a new world to me, or, rather, gave me the key or secret of the world in which I was living. It taught me that there was a beauty besides the beauty of what one calls inspiration, and comes and goes’ – taught him, indeed, ‘that life (which had seemed to me of so little moment) could itself be a work of art’.24 From Pater he caught a ‘curiosity [like] a fever’ which, in one of his Spiritual Adventures (1905) entitled ‘A Prelude to Life’, compels his teenage self to rush into a London crowd with the ‘eager hope of seeing some beautiful or interesting person, some gracious movement, a delicate expression, which would be gone if I did not catch it as it went’.25 In the ‘Prelude’, as in Pater’s portrait of Leonardo, this ‘unlimited curiosity’ is said to be uncontrollable, and comes to be described in the language of nervous febrility that Symons elsewhere applies to Verlaine and the Goncourts. ‘This search without an aim grew to be almost a torture to me’, he remembered; ‘my eyes ached with the effort, but I could not control them. [I] grasped at all these sights with the same futile energy as a dog that I once saw standing in an Irish stream, and snapping at the bubbles that ran continually past.’ ‘Life ran past me continually’, the ‘Prelude’ finishes, ‘and I tried to make all its bubbles my own’, its concluding stress landing on the ‘desperate’ process of individuation at the heart of Pater’s theory of impressions, as well as the stream that was its most powerful figure (SA, p. 139).26

That note of nervous self-torture becomes increasingly agonised in Symons’s later writings, as we will see, but Pater’s philosophy of ‘highly coloured moments’ provided a cogent rationale for the acutely impressionable, ‘intense[ly] self-conscious’ sensibility envisaged by ‘The Decadent Movement’ (‘DM’, p. 169). To be receptive to the impression of strange forms of beauty in ordinary places was to assert the vibrancy of personal experience against the aridity of ‘abstract’ metaphysical systems, as well as to manifest a ‘feverish’ curiosity amenable to modern life’s unrest.27 Crucially, this philosophy also offered Symons a conceptual model for his appraisals of modern art, particularly impressionist painting, which in turn informed his efforts to define an impressionist style in literature. Released from analysis, the stream Symons borrows from Pater as a metaphor for perception runs through the city to art itself, as in the ‘Prologue’ to his first collection, Days and Nights (1889), which is dedicated to Pater ‘in all gratitude and admiration’:

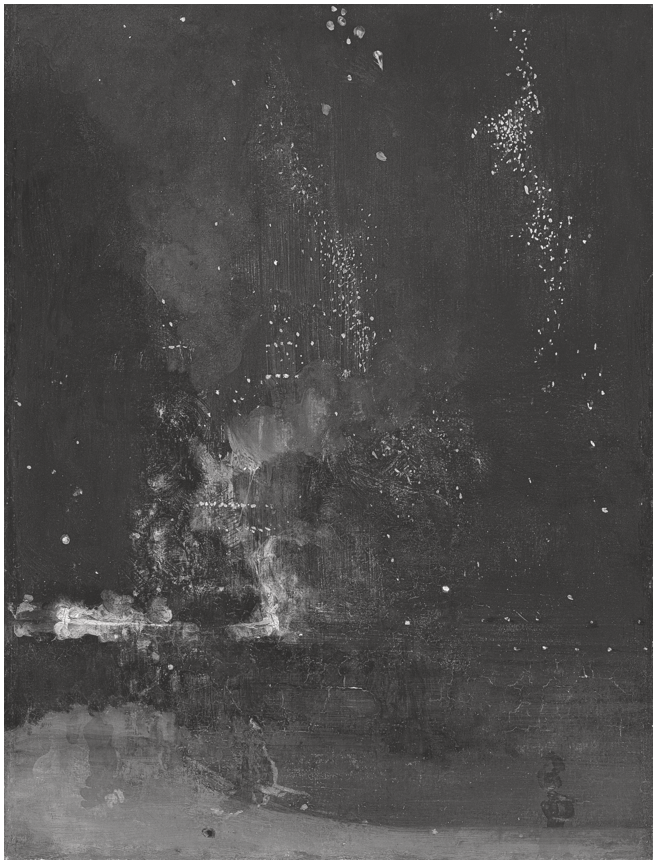

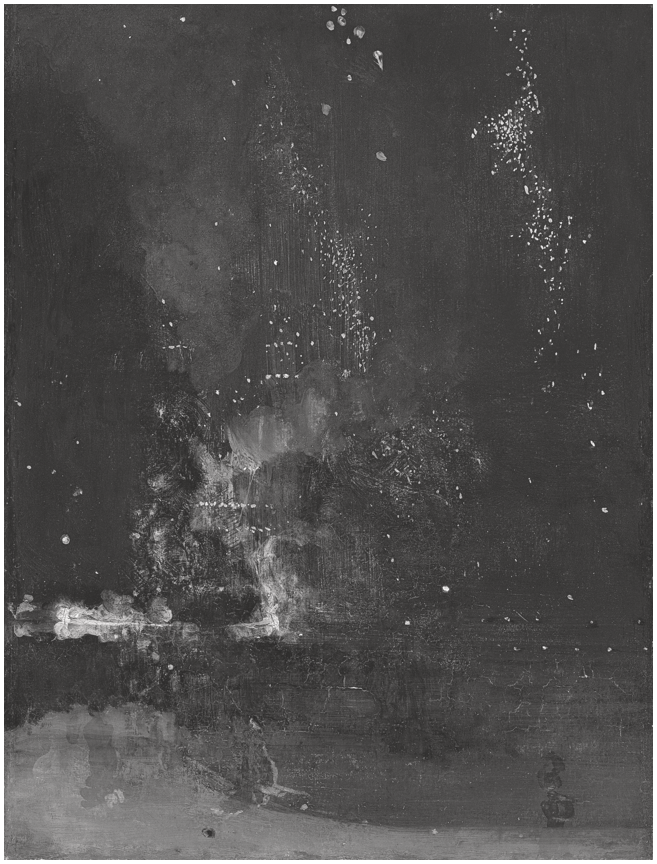

Very often it led to the art of one painter in particular, who demonstrated to Symons in a particularly vivid way what it would mean to distil the strange beauty of modern life. In his review of W. E. Henley’s 1892 collection London Voluntaries, for example, Symons claimed that the poems ‘flash before us certain aspects of the poetry of London as only Whistler had ever done’, comparing Henley’s urban vignettes favourably with Whistler’s painting of fireworks bursting over the Thames, Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket (c. 1875, Figure 1.1); while in his obituary for the painter, Symons cast Whistler in a distinctly Paterian mould, remarking that his pictures have ‘their brief coloured life like butterflies, with the same momentary’ – and ‘curious’ – ‘perfection’ (SSA, p. 138).28

Brought into correspondence with Pater’s philosophy in this way, Whistler’s paintings supplied templates for the diseased form of fleeting instants and fragmented outlines described in ‘The Decadent Movement’. Whistler was ambivalent about the impressionist group, but like the French painters (and indeed Pater himself) he emphasised the personal and momentary nature of what he referred to as his ‘impressions’, claiming to ‘knock one off’ every ‘couple of days’.29 While the evocative sparsity of his paintings would often attract accusations of formlessness and incoherence – notably from John Ruskin, who likened the Nocturne in Black and Gold to a flung pot of paint – Symons found in Whistler’s ‘morbid intensity [in] seeing things’ a paradigm for the aesthetics of nervous receptivity and formal rupture which underpin his descriptions of impressionist style, whose exponents, ‘in literature as in painting, would flash upon you in a new, sudden way so exact an image of what you have just seen, [that] you may say, as a young American sculptor [said] to me on seeing for the first time a picture of Whistler’s, “Whistler seems to think his picture upon canvas – and there it is!”’ (‘DM’, p. 170).30 In a way that seemed to align with the vision of flux outlined in Pater’s ‘Conclusion’ and the French painters’ preference for the esquisse over the finished tableau, Whistler painted rapidly, often evoking figures with single brushstrokes and flecks of paint, and suggesting that the ‘proper execution of the idea depends greatly upon the instantaneous work of my hand’.31 To ‘the dangerous stupidity of intelligences misguided’, as Symons called it, such impressions may have appeared unwhole – may even have seemed so ‘slight’ as to be incomplete – but their sketchiness was, he felt, integral to their intended sense of evanescence (SSA, p. 125). As he remarked, it was Whistler’s aim ‘to be taken at a hint, divined [by] telepathy’ in a kind of immediate mental transmission requiring only ‘glimpses in which one sees hardly more than a colour, no shape at all, or shapes covered by mist and night’ (SSA, p. 136). If this approach had led Whistler to break the outline of conventional representation, Symons argued, he, like the Goncourts, had done so only to preserve the heat and motion of life: ‘Take some tiny, scarcely visible sketch’: ‘it is a moment of faint colour as satisfying [as] one of those moments of faint colour which we see come and go in the sky after sunset’. To ‘enclose the commentary within the frame’ would do harm; ‘Whistler has said the essential thing’ and that is enough: analysis leaves off (SSA, p. 138).

Besides offering suggestive formal models, the gestural slightness of Whistler’s paintings also indicated how an aesthetics of momentary impressions might harness the current of imaginative energy running through Pater’s ‘Conclusion’. The ‘essential thing’ in Whistler’s case, as in Pater’s, was his intuitive response to – rather than accurate representation of, or moral comment upon – the scene he painted.32 Thus, he justified the unusual appearance of his Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge (c. 1872–5) by explaining that the image was not intended to be a ‘correct’ ‘copy of Battersea Bridge’ but rather a ‘harmony of colour’, just as the Nocturne in Black and Gold was offered not as ‘the portrait of a particular place’ but rather ‘an artistic impression that had been carried away’.33 Elsewhere he argued that imaginative detachment from the literal was an artistic obligation, remarking that ‘[t]he imitator is a poor kind of creature. If the man who paints only the tree, or flower, or other surface he sees before him were an artist, the king of artists would be the photographer. It is for the artist to do something beyond this.’34 Such overt disregard for empirical truth aggravated critics with an investment in artistic realism, appearing to Ruskin (for example) as a kind of ‘ill-educated conceit’ which effaced the God-given outlines of the natural world.35 Yet if Whistler’s mimetic departures seemed insane to his detractors, to Symons they were thrilling examples of the imaginative licence afforded by what Pater had called a ‘love of art for art’s sake’. As Symons remarked, Whistler went ‘clean through outward things to their essence’ with an exhilarating disregard for their actual outlines (SSA, p. 49). For this reason, he comes to serve as the ideal standard for the ‘poetry of evocation’ espoused by ‘The Decadent Movement’ – ‘poetry which paints as well as sings, and paints as Whistler paints’ (‘DM’, p. 174) – as well as the archetype of that new, feverishly excited note of ‘personality’ the essay diagnoses in European art (p. 177). A ‘visionary’ who saw with ‘the vividness of hallucination’, Whistler had dispensed with truth’s ready-made forms to unveil what Symons called a ‘new conception of what the real truth of things consists in’: one in which the painter ‘touch[es] nothing that he [does] not remake or assimilate in some faultless and always personal way’, so that his subjects appear ‘strangely existent’, but as if ‘dreamed on canvas’, at an unearthly remove ‘from the dull insistence of ordinary life’ (SSA, p. 136). To those who would reprove this deliberate process of creative refashioning, Symons responded by affirming Whistler’s defence of the artist’s proper remit: ‘Nature can take good care of herself, and will give you all the reality you want’; ‘but the way of looking at nature, which is what art has to teach you’, can ‘come only from the artist’ (SSA, p. 144).

Symons claimed various instructors in the art of looking, particularly in relation to the perspectives he adopted in his poetry. He often credited Edgar Degas with opening his eyes to a new range of subject matter, suggesting that he had ‘tried to do in verse something of what Degas had done in painting’.36 He was close, too, to Walter Sickert, who was one of his chief companions to the London music halls, and whose paintings feature in several of Symons’s lyrics.37 But ‘The Decadent Movement’ draws together the figures who shaped Symons’s way of looking at a formative stage in his career, and the vision of his early collections owes much to the ‘unhealthily impressionable’ aesthetics of evocative fragments it articulates. Promising to unshackle him from ‘straightforward narratives [of] barren facts’ – and, more broadly, from the notion that art should present the ‘complete view’ – the combined influence of Pater, Whistler and French writing enabled Symons to arrive at a sense of his own preferred style: ‘an impressionistic art’ in which the whole is subjugated to the part, and the dull insistence of colourless facts dissolves under the pressure of intensely felt ‘inner meanings’.38 Indeed, his fiction repeatedly draws Paterian portraits of young men (usually men in some way resembling Symons himself) who learn the art of looking from Whistler and find poetic equivalents for his ‘diseased sharpness’ of vision in the exquisitely depraved forms described in ‘The Decadent Movement’. ‘All art is a way of seeing’, says the painter-protagonist of ‘The Death of Peter Waydelin’ (1904), and ‘the art of the painter consists [in] getting rid of everything but the essentials’: ‘You have to train your eye not to see’, like Whistler, ‘who sees nothing but the fine shades’, just ‘as Verlaine writes songs almost literally “without words”’ (SA, p. 190). The same analogies underpin Symons’s definitions of impressionist style in poetry, which prioritise the distillation of emotional ‘essence’ through aggressive processes of abbreviation. Thus, Jules Laforgue is praised for pursuing a ‘theory which demands an instantaneous notation (Whistler, let us say) of the figure or landscape which one has been accustomed to define with rigorous exactitude’ in order to preserve the ‘essential heat’ of the moment.39 While on one view such a theory would appear limited, perhaps even insane, Symons found it a congenial blueprint for his own verse, which shapes itself to the fusion of fleeting sensation, strenuous subjectivity and urban accident that animates his criticism.

Instantaneous notation is not the best description of Symons’s earliest poems – his first collection, Days and Nights (1889), is composed largely of dramatic monologues and ballads – but in his second collection, Silhouettes (1892), he frequently adopts a more compact quatrain form, substituting lighter tetrameter and trimeter lines for the pentameter lines which had predominated in the preceding volume. Concurrent with this metrical change is a change in perspective, so that narrative descriptions are replaced by briefly sketched impressions of urban life seen through the eyes of an isolated authorial voice. Often those impressions are almost literally noted, taking the form of paratactic lists which catalogue hastily glimpsed features, as in the Baudelairean ‘Maquillage’:

Or they will produce sudden contrasts, as in the opening lines of ‘In Bohemia’, which erupt out of the obscure hedonism of a London music hall – itself registered in fragments – into the cold moonlight of a Whistler nocturne:

There were circumstantial reasons for this change in approach. As Alex Murray and Jane Desmarais have suggested, a general shift in the style and subjects of Symons’s writings can be traced to his first visits to the Continent with Henry Havelock Ellis in 1889 and 1890, during the course of which he became infatuated with the ballet and the music hall.40 The particular kinds of transformation Symons achieves in his verse seem to coincide specifically with his trip to Paris in 1890, where he managed to insinuate himself into the company of Stéphane Mallarmé, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Maurice Maeterlinck and Paul Verlaine. These are the subjects of ‘The Decadent Movement’, and Symons’s poems begin at this point to prefigure the stylistic procedures he describes in his essay three years later, abandoning ‘continuous story’ in favour of impressing images of ‘this or that revealing moment, this or that significant attitude or accident or sensation’ on the mind of the reader.

‘In the Train’, which originally appeared under the title ‘Going to Hammersmith’ in the Academy in July 1891, and which Symons reprinted in Silhouettes as part of his Whistlerian ‘City Nights’ series, is composed entirely of images of this kind. Here is the first stanza:

Such images tend to arrive in volleys, discharged by a near-verbless syntax which renders the fleeting apparition of colour and light. The effect is replicated in ‘Impression’, a poem written for the music hall performer Minnie Cunningham in 1894 and subsequently added to the 1896 edition of Silhouettes. Where the first poem achieves its sense of speed by asyndeton, or the omission of conjunctions between clauses, in the opening quatrain of ‘Impression’ a similar effect is produced in the opposite way, through the repeated use of conjunctions:

By alternately omitting and making ubiquitous the grammatical links which govern the reader’s sense of duration, Symons is able to present synecdochic glimpses of what he called ‘the restlessness of modern life’ as though they were somehow outside time, or happening too quickly for time to be fully registered.41

Looked at from another angle, what these lyrics represent is a particular way of viewing the world. Specifically, they adopt the new way of seeing things described in ‘The Decadent Movement’, seeking neither to see things steadily nor to see them whole. In a short essay entitled ‘At the Alhambra: Impressions and Sensations’ (1896) detailing an evening at an east London music hall, Symons observed that ‘to watch a ballet from the wings is to lose all sense of proportion, all knowledge of the piece as a whole; [but] in return, it is fruitful in happy accidents, in momentary points of view’ (SA, p. 92). With those happy accidents in mind, the poems Symons wrote during this period are frequently given over to narrators whose vision is circumscribed – by crowds, street corners, or, as in ‘At the Stage Door’ (written in 1893 and published in London Nights two years later), by the archway where art brushes against life:

Apprehended just before they pass away, these momentary and ‘highly coloured’ apparitions attracted Symons because of their ‘accidental’ nature, which is to say their happening out of the ordinary order of things (even if these extraordinary images nonetheless arise in ‘quite ordinary places’), their appearance in ‘curious’ places relative to the eye that sees them and their shedding of the usual contexts and perspectival dimensions which make them signify. His description of sitting in the wings might in that sense be viewed as a spatial metaphor for the logic of the periphery that Symons outlines in his criticism, according to which we ‘need tease ourselves with no philosophies, need endeavour to read none of the riddles of existence’ because a comprehensive vision of things is either fractured or, as Pater had argued, impossible (SA, p. 97). The poems adhere to this logic: voiced from the narrow chamber of the mind, in them things are often seen at oblique angles by personae who posit perspectival limitation as the condition of experience. In other words, they suggest that to attempt to see the whole picture, or to try too hard to situate one’s immediate perceptions within a larger system of meaning, is to renounce experience itself and let the ‘heat of life’ leak away.

This is certainly the underlying mood of Symons’s third collection, London Nights (1895), as we gather from the penultimate stanza of a poem proffered as its ‘Credo’:

Which is not to suggest that Symons turns away from serious things entirely, or even at all (although this was a criticism his verse would frequently attract). Rather, it is to notice his serious attempt to explore an anti-metaphysical outlook in poetry, where the goal is no longer a comprehensive one, but instead ‘[t]o fix the last fine shade, the quintessence of things; to fix it fleetingly’ (‘DM’, p. 174). Like Whistler’s, Symons’s impressions are inward visions rendered in such a way as to appear immediate. After the manner of Verlaine, they aim to capture those finer shades of feeling which exist beyond the genteel eloquence and rigid prescriptions of moral rhetoric. In Symons’s translation of Verlaine’s ‘Art poétique’ (1882), the reader is instructed (in an intentional irony) to ‘Take Eloquence, and wring the neck of him!’42 In its place, ‘Music first and foremost of all!’:

The translation mimics Verlaine’s rimes embrassées, where the first line of a quatrain rhymes with or is identical to the fourth. Homophonically bracketed at both ends, the recursive aural patterning of the Verlainian stanza was meant to approach a kind of pure musicality, which in turn was supposed to produce an art object hermetically sealed against extraneous moral concerns. This elevation of la musique avant toute chose is itself viewed in Symons’s essays through a Whistlerian lens: ‘[Verlaine’s] is a twilight art, full of reticence, of perfumed shadows, of hushed melodies’, Symons wrote in 1891 – ‘it suggests, it gives impressions, with a subtle avoidance of any definite or too precise effect of line or colour’.44 Elsewhere he remarks that ‘Verlaine subtilises words in a song to a mere breathing of music. And so in Whistler [there are] shapes covered by mist or night’ (SSA, p. 137).45

Symons was not alone in comparing the two artists in this way; the dissolution or blurring of line was a useful metaphor for critics and artists wishing to cross the formal thresholds between text, image and song, especially in the case of Whistler and Verlaine. In 1889, Huysmans had also compared painter and poet in terms of a meshing of ‘nuances’ so fine as to approach a vapour-like indistinctness, which was most apparent when each artist seemed about to pass into the territory of the other: just as ‘Mr. Wisthler [sic], in his harmonies of nuances, goes almost to the boundary of painting’, he remarked, so ‘M. Verlaine has obviously gone to the limits of poetry, where it evaporates completely and where the musician’s art begins.’46 In Symons’s writings this movement across art forms sometimes took the form of a literal-minded pictorialism: Catherine Maxwell and Jane Desmarais have both identified attempts by Symons to simulate adjectivally the ‘spectral softness’ of Whistler’s canvases, with their tendency to dissolve outline in colour tones being paralleled by his ‘prose-Whistlerian’ descriptions of the Venice lagoon sunk in mist and his portrayals of diffused scent.47 But the language of Symons’s critical analogies between Whistler and Verlaine – and between the ‘mazy lines’ of his own verse and the ‘mist of lines’ he found in impressionist painting (SP, p. 59) – also suggests a more significant correspondence. To avoid any ‘too precise effect of line or colour’ is to be vague, yet in Symons’s handling the vagueness of the analogy is its most salient feature: if Whistler’s colour ‘harmonies’ (as he called them) are commensurable with Verlaine’s romances sans paroles (songs without words), they are so because of their shared obscurity, the immunity from certain ‘facile’ kinds of meaning each artist claims for their work. That, at least, is the basis for Symons’s own splicing of Verlaine’s musique and Whistler’s ‘fineness of shades’, which, by contrast with the rigidities of Hegelian metaphysics, and of conventional thought more broadly, are said to be equivalently ‘subtle’ and ‘suggestive’. At the same time, the impressionist has an almost violent ‘sharpness’ in her or his perception of delicate shades of feeling, because the figurative wordlessness Symons describes frees the artist from – may even be an attack on – the proprieties which might constrict their pursuit of ‘the impression of the moment followed to the letter’ (‘DM’, p. 174).48 As Symons argued, ‘Social rules are made by normal people for normal people, and the man of genius – the Whistlerian or Baudelairean “visionary” – is fundamentally abnormal’: ‘it is the poet against society, society against the poet, a direct antagonism’. If the shock of this confrontation ‘is often possible to avoid by compromise’, then Verlaine’s calculated indeterminacy would be a means of subverting social rules which might fetter the ‘fierce subjectivity [of] natures to which compromise is impossible’.49

In its refusal to convey certain meanings in the way it ought to, this studied vagueness is a stylistically codified stab at the received moralities that a poet might be expected to keep in health. It is also an invitation to enjoy the poem for the poem’s sake, on the basis of which Symons claims ‘an equal liberty for the rendering of every mood of that variable and inexplicable and contradictory creature which we call ourselves’ – even in the face of what, in the ‘Preface’ (1896) to the second edition of Silhouettes, Symons called the ‘fallacy by which there is supposed to be something inherently wrong in artistic work which deals frankly and lightly with the very real charm of the lighter emotions and the more fleeting sensations’ (SP, pp. 198–9). At the levels of form and content, in other words, the impressionist style that Symons is defining involves a disregard for (or resistance to) certain kinds of moral prescriptiveness which allows poet and reader to gain territory elsewhere. The ‘Prologue’ to Symons’s London Nights is exemplary in this respect, borrowing Verlaine’s stanza form and Whistler’s cloudy atmospheres to depict the sensations of an imagined music hall and a notably heightened kind of self-consciousness:

While the poem’s track of thought is strikingly inward-facing and involved, the identity of the speaking voice is oddly indistinct. That is to say, because it is not entirely clear whose thoughts are being communicated by the poem, its subject seems in one sense strangely impersonal, particularly in view of its pronominal insistence that there is a subject, a ‘very self’. But on account of that dissonance, the ‘Prologue’ might be said to yield a perfect example of the ‘disembodied voice’ that Symons had posited as ‘the ideal of Decadence’, the poem’s reticence in fleshing out its speaker’s biography in an extended narrative fashion being reflected in the vacancy of the refrain to which it gives voice (‘DM’, p. 174). Indeed, its ‘empty song’ is a wordless kind of music (or one where the meanings of words are of secondary importance) which, like the poem’s enveloping rhyme scheme, resembles Verlaine’s own. And the verbal patterning of the ‘Prologue’ rounds back on itself so that, like its speaker, it seems to see itself perform. The poem poses as a self-sufficient (because self-divided, in conversation with itself) objet d’art which describes the same formal autonomy that it exemplifies: it does not perform for any purpose extrinsic to it; it remains ‘in make-believe of holiday’, in its own dream of the world.

Such lyrics indicate the wider significance of the impressionist style that Symons defines in ‘The Decadent Movement’. In the case of the ‘Prologue’, there is a technical dexterity with which the speaker’s rounding-back is embedded within the architecture of the poem, which would illustrate Symons’s successful assimilation of new verse styles from France. At the same time, the poem suggests how that assimilation might enlarge the scope of English poetry in general. In the self-regard it both describes and embodies, the ‘Prologue’ not only represents a formal consummation of the self-sufficiency implied by l’art pour l’art (Pater’s ‘art for art’s sake’); it also indicates what kind of poetry might be written under the aegis of that maxim. In this case, as in so many of his early poems, Symons’s ornate formal structures seem to sponsor a new kind of erotic subject matter. As Stephen Cheeke has remarked, the mirrored terms of art for art ‘evoke the myth of Narcissus, suggesting a pathology of self-regard and a libidinal economy that is essentially onanistic’.50 In the ‘Prologue’, there is a literal kind of self-regard (‘I see myself’), which, given the poem’s stylistic self-concern and erotically charged locale, may shade the speaker’s ‘impotence’ with an unintended second sense. Certainly, the relationship between speaker and performer is voyeuristic – even if its voyeurism is curiously self-directed – pointing to how Symons’s disembodied voice tends to linger over distinctly embodied moments of experience. For example, the first stanza of the obviously Whistlerian lyric ‘Nocturne’ (1892) depicts an erotic encounter in a cab:

In his obituary for Whistler, Symons had written that the painter found ‘astonishing beauties’ in places that had been ‘made beautiful by the companionship and cooperation of the night’ (SSA, p. 137). Likewise, in Symons’s poem the city sparkles underneath an ‘invisible dome’ of darkness, transformed by the artist’s imagination and ‘the magic and the mystery that are night’s’. If darkness makes seeing things whole impossible, it is for this reason that it serves for both Whistler and Symons as a pretext for the artistic representation of beauty itself. As night falls, both poet and reader are relieved of the burden imposed by the ‘jagged outline of things’, as are the lovers in the backseat, who are ‘Free of the day and all its cares!’ (SP, p. 72), darkness obscuring the world beyond their window, while covering over, and so enabling, a casual sexual encounter.51 Indeed, the poem’s depiction of ‘Human love without the pain’ might be said to be made in its own image. Just as the concupiscence it depicts relies on not seeing things whole, so too does its refashioning of reality along aesthetic lines – its transformation (or erasure) of the Embankment’s poverty and pollution, its detachment from life’s ‘ordinary’ outlines and its immersion in the more aesthetically satisfying ‘essence’ of the ensemble imagined in its place. The speaker remembers how the pavement ‘glitter[ed]’ where ‘the bridge lay mistily’, giving lyrical being to the ‘evening mist’ which, in Whistler’s ‘Ten O’Clock’ lecture (1885), ‘clothes the riverside with poetry’ by covering over its less palatable features.52 What remains is an image of human life without the pain, ‘in make-believe of holiday’, and an artwork content to luxuriate in its own interlacing rhyme schemes (along with the glimpses of erotic jouissance they embroider) in place of those aspects of ‘ordinary’ life which might distract from them.

The poem’s remoteness from certain aspects of the objective world, especially those aspects of the city that would disrupt its mood of erotic playfulness, underlines a tension in Symons’s definition of impressionism as a poetics of urban modernity. Yet it is worth noticing what kind of lyric experiments were enabled by this ‘holiday spirit’, as Verlaine called it in his review of London Nights.53 Under its auspices, Symons borrowed Whistler’s palette and Verlaine’s rhyme schemes to depict erotically charged flashes of the ‘exquisite curves’ he observed on stage and behind closed doors.54 The poem ‘Pastel’ (1892) is perhaps the most accomplished example of this:

The poem is implicitly aligned with impressionist art, evoking the boudoir pastel works of Degas as well as the smouldering imagery of Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold. And the cigarettes at its centre serve as emblems of the poem’s own impressionist procedures: they flare, gem-like, for a moment, their flash of heat being paralleled by the speed with which the poem flashes its three discrete images upon the reader, its economy of diction and asyndetic omissions engendering the sudden radiance, in turn, of a hand, a ring and a face. Those features, and the manner in which they are perceived, are evidence of both the kind of encounter to which the poem bears witness and its motives for doing so. Walled in by the narrow chamber of the mind, and diminished further by darkness, the margins of the speaker’s vision are tightly delimited, but if Symons’s essay is right it could not be otherwise, and the philosophical limitations for which restricted vision is a metaphor are not without compensations: what light there is illuminates infidelity (assuming the ring is marital) and, by extension, both the sexual freedom Symons liked to claim that he exploited and the shedding of moral strictures this would imply.

Symons’s apparent eagerness to portray himself (or speakers who seem calculated to resemble himself) capitalising on such liberties can distract from the historically significant stylistic freedoms – particularly from narrative exegesis and moral instruction – which his poetics of half-sight ushers in, and which would be so important to the modernists who followed him. As Hugh Kenner remarked in The Pound Era (1971), the final stanza of ‘Pastel’ anticipates Ezra Pound’s ‘In a Station of a Metro’ (1913):

Not an interpretative comment, but three happenings, have entered the domain of the pictorial: an abstract noun; an unexpected un-pictorial adjective; and, interpolated, (‘A rose!’) another image fetched from elsewhere by the mind, something else to see but not present in the scene, present only in the poem.55

All three combine in the space of two lines to fuse the eternal (‘grace’) with the poetic (‘lyric’) and momentary (‘face’) in a concentrated palimpsest of ocular and imaginative vision, an emotionally charged ‘impression’ evoked as an almost instantaneous experience in the mind of the reader. In the poem’s epiphanic self-incarnation, ‘we are’, as Kenner suggests, ‘coming close to “Petals on a wet, black bough”’.56

Symons’s amalgamation of Pater’s philosophy, impressionist painting and recent French verse in ‘The Decadent Movement’ brought together various important currents in late nineteenth-century aesthetics, yielding lyrics which not only pre-empt certain major forms of twentieth-century poetry, but also reflect a moment of significant transferral between art forms – and, indeed, across the Channel. More generally, Symons’s reaction against the Arnoldian precepts of wholeness and even balance foreshadowed the wider modernist fascination with evocative fragments and subjective perspectives, and his writings would have a shaping influence on the generation of writers which succeeded his own. T. S. Eliot described his encounter with Symons’s essays as ‘an introduction to wholly new feelings, as a revelation’.57 Pound admired the poems and art criticism, including Symons somewhat implausibly alongside Dante, Plato and Spinoza in a list of his personal ‘gods’.58 Ford Madox Ford thought him ‘a great – [a] marvellously skilful – writer’, while James Joyce found in the short fiction models for his Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916).59

However, Symons’s preoccupation with momentary effects in his verse was at first poorly received, meeting with what he remembered as ‘a singular unanimity of abuse’ (SP, p. 200). Late in 1894, John Davidson wrote a report on London Nights for the Bodley Head describing the book as ‘an embodiment [of] mere and sheer libidinous desire’ in which the ‘trivialities of harlotry are very deftly treated’ – a complaint which marries eroticism and formal sleekness but in a pejorative sense.60 In a similar vein, W. B. Yeats recalled Lionel Johnson fulminating against Symons’s ‘Parisian Impressionism’, which he summed up as ‘a London fog, the blurred tawny lamplight, the red omnibus, the dreary train, the depressing mud, the glaring gin-shop, the slatternly shivering women, three dextrous stanzas telling you that and nothing more’ (A, p. 238).61 William Archer would grant Symons his ‘technical accomplishment’, and admired the ‘competence of his workmanship’, but thought the poems lacked ‘the element of the miraculous’ necessary for them to be anything more than ‘documents in erotic psychology’, remarking that ‘[h]is verses impress us, one and all, as the metrical diary of a sensation-hunter’.62 For each, the objection is not so much to the ‘dexterity’ of the poems, but to their mere dexterity: the fact that they offer the reader ‘nothing more’ than passing, often ‘libidinous’ moods, and their own vogueish style.

It seems unlikely that Symons would have taken these criticisms to heart. In his ‘Preface’ (1896) to the second edition of London Nights, he was candid about both the ephemerality and the subjectivism of the impressions contained in the book:

Whatever has been a mood of mine, though it has been no more than a ripple on the sea, and had no longer than that ripple’s duration, I claim the right to render, if I can, in verse[.] I do not profess that any poem in this book is a record of actual fact; I declare that every poem is the sincere attempt to render a particular mood which has once been mine.

But the poor reception of the lyrics damaged Symons’s reputation, and prefigured some of the more persistent misgivings about impressionism as a literary style. In particular, the recurring complaint about Symons’s ‘too sedulously self-observant’ cultivation of his own moods (to borrow Archer’s phrase) anticipates the doubts of later critics, such as Fredric Jameson, who have argued that impressionism is a form of irresponsible self-absorption – a style which ‘discards even the operative fiction of some interest in the constituted objects of the natural world’ and posits ‘the perceptual recombination of sense data as an end in itself’, ‘derealiz[ing]’ the world in order to ‘make it available for consumption on some purely aesthetic level’.63 While Symons’s poems represent a significant early attempt to conceive an impressionist style in English literature, the response that greeted them also identified deficiencies which have since been attributed to impressionism by contemporary literary criticism. Symons’s early writings might in this sense be seen as the original case study for the strengths and demerits of impressionist literature itself, with its dual implications of formal ingenuity and wilful detachment, vibrancy and vanity.

Indeed, there is a quite extreme fashion in which the potential risks of the forms described in ‘The Decadent Movement’ might be seen to play out in Symons’s writings – particularly those he composed in the years before his nervous collapse in 1908, which often return to his earlier essay’s language of instability and fragmentation, but seem themselves to become unstable in doing so. Perhaps the most intriguing of the early appraisals of Symons’s poetry was authored by Le Gallienne himself, whose diagnosis of ‘insane thinking’ in recent French writing had stimulated Symons to define impressionism in the first place. In a review of Silhouettes published shortly after his article for the Century Guild Hobby Horse, Le Gallienne offered cautious praise for Symons’s ‘genuine gift of Impressionism’, but like Johnson (if less bitterly) he noted the ‘slightness’ of the poems, deducing that ‘Mr Whistler and M. Verlaine are evidently the dominant influences on him.’64 Those are the artists he had given as examples of decadence earlier that year, and the line of connection he draws between them and Symons also marks the limit of his approval, since what he had called ‘the euphuistic expression of isolated observations’, or an absorption in momentary effects divorced from their ‘whole’ series, is what Symons calls impressionism in his criticism and exemplifies in his verse. Yet ‘isolated’ also has a second sense which suggests something more troubling about the type of decadence Le Gallienne diagnoses, and which has a peculiar and disturbing resonance for Symons’s writings in light of his own experiences of insanity.

Forms of isolation are central to much of Symons’s verse, fiction and criticism. In ‘Veneta Marina’ (1894), for example, Symons cast himself in the mould of the subjects of ‘The Decadent Movement’, companionless and apart from the whole. This is the third stanza:

The pose here is self-conscious and controlled, even if the kind of self-consciousness the poem describes (as distinct from the one it exemplifies) caused one reviewer to worry that Symons was afflicted with a ‘super-consciousness of life’ which had made him ‘turn away from exteriority’ in a kind of ‘spiritual suicide’.65 But when Symons returned to the theme in the first part of ‘The Brother of a Weed’, a short lyric sequence written a year before his nervous collapse in Venice in 1908, his mood was different:

This is a self-portrait that is as candid about its author’s solipsism as its precursor, but which, having shifted into the present perfect – as if suddenly to wonder at never having wondered – seems newly elegiac, almost forebodingly so. (It is notable also that the state of being ‘alone’ has given way to the state of being ‘lonely’, which has a quite different resonance.) In their obsessive attention to his ‘imaginings’, as well as their inward-turning formal procedures, Symons’s poems all share this emphasis on interiority – like Daniel Roserra, the narrator of ‘An Autumn City’ (1903), he ‘respect[s] nature’ only for the ‘image a place makes for itself in the consciousness’ rather than the place itself (SA, pp. 204–5) – but the later verse seems hesitant about this emphasis in ways that the early verse is not.

The images that Symons refers to are descendants of the impressions Pater had described in his ‘Conclusion’. After the minor controversy which followed the initial publication of The Renaissance in 1873, Pater was also doubtful, worrying in a footnote to the 1888 edition that it had been misconceived by ‘some of those young men into whose hands’ it had passed.67 In The Trembling of the Veil (1922), Yeats recalled that he and his contemporaries had ‘looked consciously to Pater for our philosophy’, and wondered if the attitude of mind described in Pater’s writings ‘had not caused the disaster of my friends’ in the Rhymers’ Club, of which both he and Symons were members: ‘it taught us to walk upon a rope stretched through serene air, and we were left to keep our feet upon a swaying rope in a storm’ (A, p. 235). The metaphor suggests the vulnerability inherent to Pater’s brand of ‘super-consciousness’ in a context where, as Nicholas Freeman argues, his ‘dismissal of “theory”’ ‘detached contemporary debates about impressionism from their apparent roots in Hume and Berkeley’, and provided ‘an intellectual short-cut for writers’ – like Symons – ‘eager to apply impressionism to urban life, rather than to philosophical inquiry’.68 Sensitive to its potential misapplication, Pater made repeated attempts to impose limits on the thirst after experience described in his ‘Conclusion’, tempering what many had taken to be the doctrine of pleasure implied by his claim that ‘our one chance is [in] getting as many pulsations as possible into the given time’.69 In Marius, in particular, Pater revises the argument to foreground qualities of wholeness which are absent from Symons’s impression of his philosophy: ‘Not pleasure, but a general completeness of life, was the practical ideal to which this anti-metaphysical metaphysic really pointed. And towards such a full or complete life, a life of various yet select sensation, the most direct and effective auxiliary must be, in a word, Insight.’70 Accordingly, Marius would be inclined to ‘take flight in time from any too disturbing passion’ likely ‘to quicken [the] pulses beyond the point at which the quiet work of life was practicable’.71 But here Symons and Pater part ways. In a review of Imaginary Portraits (1887), Symons noticed in Pater a ‘chill asceticism’, and conjectured that ‘he never would have appreciated writers like Verlaine’ because ‘it pained him, perhaps only because [he was] more acutely sensitive than others, to walk through mean streets’.72 If Pater’s own counsel was therefore ‘always in the direction of sanity’ and ‘restraint’, Symons made a virtue of exactly the unhealthy impressionability that Marius’s prudence and moderation are supposed to counteract.73 Indeed, to ‘sharpen the acuteness of every sensation’, especially the sensations of ‘mean streets’, was both a strategy integral to his impressionism as well as its justification. A ‘diseased sharpness’ of the nerves might make for ‘disordered vision’, but then ‘simplicity, sanity, proportion’ – ‘how much do we possess them in our life [that] we should look to find them in our literature?’ (‘DM’, p. 180).

‘Disorder’, ‘disease’ and ‘insanity’ were all useful rhetorical terms for Symons, but when Eliot wondered in ‘The Perfect Critic’ (1920) if Symons was the type of critic who ‘reacts in excess of the stimulus’, he was voicing scepticism not just about an unhealthy impressionability in his criticism; he was making the more provocative suggestion that Symons was too ‘disturbed [by] his reading’ to have been left ‘internally unchanged’ by it in life (CPE, II, p. 265). Transactions between art and life of this kind may seem unlikely, but in his ‘Introduction’ to The Renaissance, Symons (following Pater) had insisted on an overlap. More recently, Rita Felski has argued that ‘our being in the world is formed and patterned along certain lines’ and, further, that ‘aesthetic experience can modify or redraw such patterns’.74 If redrawing of this kind is possible, as Symons professed it was, then the critical ‘disturbances’ induced by an ‘overbalancing’ ‘susceptibility of the senses’, and ‘an emotional susceptibility not less delicate’, seem fraught with dangers, as Symons’s autobiographical fiction tends to suggest (‘DM’, p. 170).

‘Christian Trevalga’ (1905) is his Paterian portrait of a pianist who, in keeping with the marriage of art and life he aspired to, resembles Symons himself. Trevalga resembles Whistler, too, possessing the painter’s disregard for ‘outward things’ as well as his visionary faculty, so that ‘sounds [become] visible’ to him (SA, p. 167). Here, however, its underlying self-absorption is ‘unsafe’. ‘Occupied more and more nervously with himself’, Trevalga begins to lose his hold on the world:

Gradually sound began to take hold of him, like a slave who has overcome his master. The sensation of sound presented itself to him continually [like] some invisible companion, always at one’s side, whispering into one’s ears. He was not always able to distinguish between what he actually heard, a noise in the street, for instance, which came to him for the most part with the suggestion of a cadence, which his ear completed as if it had been the first note of a well-known tune[,] and what he seemed to hear, through noise or silence, in some region outside reality.

In Whistler’s paintings this confusion of perceptual and imaginative experience had been a virtue, the ‘outlines of things’ being made complete by ‘that imaginative sympathy which is part of the seeing of works of art’ (SSA, p. 52). Here it seems dangerous, as visions which possess the ‘vividness of hallucination’ threaten to lose the safe distance of analogy: ‘“So long as I can distinguish”, [Trevalga] said to himself, “between the one and the other, I am safe; the danger will be when they become indistinguishable”’ (SA, p. 168). Symons seems to have understood what the danger was. Shortly before writing ‘Trevalga’, he found himself overawed by the interior of the Kremlin, writing that ‘life lived here could but be unreal, as if all the cobwebs of one’s brain had externalised themselves, arching overhead and draping the four walls with a tissue of such stuff as dreams are made of’ – as if the fantasies of the mind had become ‘indistinguishable’ from its too-intense surroundings.75 ‘It could easily seem’, he remarked, ‘as if unhuman faces grinned from among the iron trellis of doors, as if ropes and chains twisted themselves about doorways and ceilings, as if the floor crawled with strange scales, and the windows broke into living flames, and every wall burned inwards.’76 It could easily seem as if the phantasms of those inflamed minds Symons describes in his criticism had begun to destabilise his self-characterisations. The prose shifts into the language of ‘The Decadent Movement’, Symons observing that ‘to live in Moscow [is to be] without escape from the ceaseless energy of colour, the ceaseless appeal of novelty. Mere existence there is a constant strain on the attention, in which shock after shock bewilders the eyes, hurrying the mind from point to point of restless wonder.’ Over-excited and ‘driven in upon itself from such sombre bewilderments’, he worried that the brain ‘could but find itself at home in some kind of tyrannical folly, perhaps in actual madness’.77

Actual mental pathology haunts ‘Henry Luxulyan’, the protagonist of a Spiritual Adventure written in the same year, who renounces the nervous excitement and intense self-consciousness of the ‘too narrow, London philosophy’ espoused in ‘The Decadent Movement’ by withdrawing to Cornwall (SA, p. 249). The retreat is salvific, enabling Luxulyan to turn his attention beyond ‘the circle of my own brain’, and become ‘less sick with myself’ (p. 249). In the opposite way, returns to the language of ‘The Decadent Movement’ in these stories always induce psychological distress. Later Luxulyan visits Venice, where he takes a gondola across the lagoon – symbolically coming adrift from the ‘whole’ – and stares (like Narcissus) at his reflection in the water. As he does so, he hears screams coming from a nearby island. ‘It is San Clemente’, his gondolier tells him; ‘they keep mad people there’ (p. 258). The coincidence of classical myth, self-absorption and insanity is not accidental; nor is the fact that it marks the moment at which Luxulyan is possessed by an uncontrollable ‘feverishness’ and wonders if ‘the too exciting exquisiteness of Venice drive[s] people mad?’ (p. 258). Fever, madness and nervous excitement are ideas centrally important to Symons’s conceptions of impressionism; but where they had previously affixed to an enabling ‘curiosity’, here they describe a disturbing groundlessness. ‘I came to Venice for peace’, Luxulyan writes, but its waterways – in which the images of things are doubled and distorted, as in the mind itself – become increasingly menacing, ‘even hallucinatory’. Looking into the canals, he sees ‘lights growing like trees and flowers out of the creeping water’, remarking, ‘I never felt anything like this insidious coiling of water about one’ (p. 259). On a visit in 1894, Symons had himself noted Venice’s ‘coiled’ waterways, which seemed to tighten around him like a ‘spider’s web’ – an image he later employs in his descriptions of the Kremlin to represent the mind on the brink of psychosis.78 Given the autobiographical nature of the Spiritual Adventures, the stories might then be read as Symons’s explorations of his own anxieties about adopting the ‘insane’ perspectives we find in his criticism. He borrows phrases from Pater’s ‘Conclusion’ to describe Trevalga’s breakdown, which begins with a vision of smoke, a tremulous wisp ‘forming and unforming’ before him.79 Trevalga walks into the street to ‘take hold of something real’, but is overwhelmed by the ‘horrible exterior forces’ of the crowd – Pater’s ‘flood of external objects’ – and begins to lose his ‘sense of material things’, as if his own ‘atoms [had] lost some recognition of themselves’, leaving him unable to understand why they ‘should coalesce in this particular body, standing still where all is in movement’ (SA, p. 169).80 This represents a more frightening kind of disembodiment than that which is described in ‘The Decadent Movement’, Trevalga’s inner world seeming to become indistinct from the disparate sensations around him. Its result is a bewilderment which Luxulyan (in a reference to Pater) describes as the feeling that ‘all that is solid on the earth seems to melt about one’ (SA, p. 239).81 This may be the price of one interpretation of Pater’s theories of personality. Curiously, though, it entails a form of impersonality that could properly be called ‘insane’, as in the case of Luxulyan, who succumbs to a ‘queer fever’ which disperses his identity. ‘I have had so singularly little feeling of personality’, he writes: ‘the world, ideas, sensations, all are fluid, and I flow through them [like] a weed adrift’ (SA, p. 261).

This would seem to mark the moment when a theory of impressionism with decomposition at its heart begins to disintegrate itself. Detached from questions of form, and explored instead as a rationale for life, its rejection of wholeness in favour of the momentary and interior is productive not of the evanescent shimmer which characterises Symons’s poetry, but of profound anxiety. In his Confessions (1930), an account of his nervous collapse in Venice, Symons wrote that ‘every artist lives a double life in which he is for the most part conscious of the illusions of the imagination’ – those images he cultivated so prodigiously in his own writings.82 But the sections describing his breakdown suggest a powerlessness to observe precisely this distinction between illusion and reality: Symons wonders whether he was ‘in the situation of my Christian Trevalga’, recalling ‘wild imaginings’ where ‘inward and outward [were] jumbled together in an inextricable confusion’, the boundary separating perception from its objects seeming, as in ‘Trevalga’, almost entirely absent.83 It would be an extraordinary instance of aesthetics overlaying existence, but also one whose possibility Symons’s own writings repeatedly assert, and which, indeed, he used to interpret his breakdown in retrospect. When Trevalga dies in an asylum he leaves behind ‘scraps of paper’ on which ‘he had jotted down a few disconnected thoughts’ (SA, p. 171). ‘Isolated’ from each other in sense and syntax, these fragments are each the product of a mind correspondingly isolated from ‘the world and the ways of men’, so that Pater’s emphasis on experiencing impressions strongly without worrying over their relation to objective truth appears in a newly tragic light: ‘it all comes to the same thing in the end’, reads the final note, ‘one form or another of knowledge; and does it matter if I can explain it to you?’ (p. 173). For Trevalga, the ‘strength’ Pater describes – in Symons’s interpretation a form of mental weakness – gives way to ‘actual madness’, where the brain ‘sits aside and reserves judgment, while all manner of feelings, instincts, sensations, chatter among themselves’ without an interpretive framework (or ‘facile orthodoxy’) to organise them (p. 254).

Neurosis, fever, sickness, decomposition, delirium – these are all central to Symons’s conception of what a literature of impressions would look like. Yet in the later poems and short fiction, the metaphors to which he was repeatedly drawn in his criticism seem to gesture to the unravelling of the very forms they had helped Symons to articulate – so much so that his friends and acquaintances would see a connection between pathology as pose and actual madness in the wake of his nervous breakdown, after which his illness came to seem indissociable from the style he had defined and adopted in his writings. Yeats in particular would consider Symons’s strenuous attempt to rediscover in verse an ‘impulsive’, raw-nerved syntax at least partly responsible for the mental ‘disorder’ into which he was eventually plunged (A, p. 235). Whether in fact Symons’s writings or the theory of impressionism they explore bear any relation to their author’s own ‘insane thinking’ must remain an open question: ‘to retrace [the] way in which one’s madness begins’, as Symons acknowledged in his Confessions, ‘is as impossible as to divine why one is sane’.84 But even if he had ‘no intention of giving many details of the month I spent in Venice in September 1908’, Symons’s own recollections of the collapse are suggestive. ‘I was over-excitable’, he remembered: ‘too many burdens had been imposed upon me’ by his ‘voracious appetite for life’ – his frantic ‘haste to eat and drink my fill [at] a feast from which I might at any time be called away’ – so that ‘the sudden shock of [some] common circumstance’ was ‘enough to jangle the tuneless bells of one’s nerves’. Given his reluctance to elaborate on the evening when ‘the thunderbolt from hell’ struck, it is significant that the final detail we are granted should be a description of Symons lying in his room, where, alone and agitated, his ‘nerves reacted on [his] imagination: reacted, almost recoiled, on my body’. ‘Sleep forsook me’, Symons recalled, so ‘I got out of bed and began to write and write and write.’85