Refine search

Actions for selected content:

202 results

6 - Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and the Global Energy Transition

-

- Book:

- Crude Calculations

- Published online:

- 08 January 2026

- Print publication:

- 19 February 2026, pp 163-189

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chinese migration and the ‘colonial question’: Perspectives of Chinese intellectuals, 1900s–1940s

-

- Journal:

- Modern Asian Studies , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 January 2026, pp. 1-33

-

- Article

- Export citation

7 - Uniformitarianism and the Social Ecology of Anguilla’s Homestead Period

-

-

- Book:

- Uniformitarianism in Language Speciation

- Published online:

- 10 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 December 2025, pp 265-309

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Myths, History Wars, and Indigenous-Settler Relations in Canada and Other Settler States

-

- Published online:

- 15 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 January 2026

-

- Element

- Export citation

1 - Introduction

-

- Book:

- The Venal Origins of Development in Spanish America

- Published online:

- 11 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 02 October 2025, pp 1-21

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Perspectives

-

- Book:

- Land, Law and Empire

- Published online:

- 01 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 07 August 2025, pp 1-8

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Tudor State, Chartered Companies and Colonization

-

- Book:

- Land, Law and Empire

- Published online:

- 01 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 07 August 2025, pp 9-34

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

20 - Elements of a Critical History of International Law

- from Part VI - Criticism and Reconstruction of the Legitimacy of International Law

-

- Book:

- The Law and Politics of International Legitimacy

- Published online:

- 14 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 24 July 2025, pp 373-391

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Difficult Public History and National Identity in Aotearoa New Zealand: A Narrative Approach to Museum Analysis

-

- Journal:

- Nationalities Papers , FirstView

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 May 2025, pp. 1-23

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

“Faithful Guardians of the National and State Border”: Refugees, Land Reform, and Colonization in the Post-1918 Central European Borderlands

-

- Journal:

- Nationalities Papers / Volume 53 / Issue 6 / November 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 May 2025, pp. 1310-1331

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

7 - Conclusion

- from Part III

-

- Book:

- Representants and International Orders

- Published online:

- 15 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 May 2025, pp 249-269

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A political epistemology for extinction studies? On the ideas of preservation and replenishment

-

- Journal:

- Cambridge Prisms: Extinction / Volume 3 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 April 2025, e8

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Korea, A Unique Colony: Last to be Colonized and First to Revolt

-

- Journal:

- Asia-Pacific Journal / Volume 19 / Issue 21 / November 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 March 2025, e3

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Chapter 19 - Oratory: Persuasion in Performance

- from Part III - Genres

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Nineteenth-Century American Literature and Politics

- Published online:

- 06 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 March 2025, pp 319-331

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

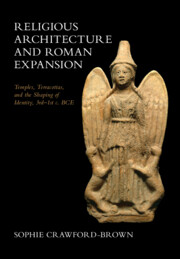

Religious Architecture and Roman Expansion

- Temples, Terracottas, and the Shaping of Identity, 3rd-1st c. BCE

-

- Published online:

- 06 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 March 2025

Chapter 7 - The Emergence of an Ars mensoria

- from Part IV

-

- Book:

- The <I>artes</I> and the Emergence of a Scientific Culture in the Early Roman Empire

- Published online:

- 22 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 February 2025, pp 316-371

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Spanish Land Grants and the Cielo Vista Ranch

-

- Book:

- American Grasslands

- Published online:

- 06 February 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 February 2025, pp 11-25

-

- Chapter

- Export citation