Introduction

The white mullet, Mugil curema Valenciennes (Mugilidae), is a widely distributed fish species occurring on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts of the Americas, with some records from the west coast of Africa (Crosetti et al. Reference Crosetti, Blaber, González-Castro and Ghasemzadeh2016; Durand et al. Reference Durand, Shen, Chen, Jamandre, Blel, Diop, Nirchio, García-De León, Whitfield, Chang and Borsa2012; Froese and Pauly Reference Froese and Pauly2025). This euryhaline mugilid species is thought to spawn offshore with its larvae migrating for nursing from the ocean to coastal environments, such as rivers, lagoons, and estuaries, where they remain until reaching sexual maturity (Barletta and Dantas Reference Barletta, Dantas, Crossetti and Blaber2016; da Silva et al. Reference da Silva, Teixeira, Batista and Fabré2018). This species has commercial value and is captured in different parts of Mexico along with the grey mullet, Mugil cephalus Linnaeus. Both species constitute an important economic resource for the artisanal fisheries in coastal lagoons and offshore areas of Mexico and are considered as secondary consumers (Ibáñez-Aguirre and Gallardo-Cabello Reference Ibáñez-Aguirre and Gallardo-Cabello2004). The position of M. curema in the food web has been proposed as one of the major factors determining the diversity of their parasite fauna (Paperna and Overstreet Reference Paperna, Overstreet and Oren1981; Whitfield Reference Whitfield, Crosetti and Blaber2016).

Metazoan parasites are typical components of marine and estuarine fishes and play a major role in ecosystem functioning and energy flow; furthermore, parasites are known to regulate host populations, and they provide information about their hosts (Giari et al. Reference Giari, Castaldelli and Timi2022; Lafferty et al. Reference Lafferty, Allesina, Arim, Briggs, DeLeo, Dobson, Dunne, Johnson, Kuris, Marcogliese and Martinez2008; Williams et al. Reference Williams, MacKenzie and McCarthy1992; Wood and Johnson Reference Wood and Johnson2015). Some studies have addressed the parasite fauna of the white mullet in particular geographical regions. Up to the present time, the parasitological record of this host species across its distributional range contains 88 taxa including myxozoans, monogeans, digeneans, cestodes, acanthocephalans, nematodes, malacostracans, copepods, and hirudineans (Falkenberg et al. Reference Falkenberg, de Lima, Vieira and Lacerda2022). However, information on the parasite fauna of M. curema in the Yucatán Peninsula is very scarce (Andrade-Gómez and Pérez-Ponce de León Reference Andrade-Gómez and Pérez-Ponce de León2024).

As a part of a research project aimed at describing the metazoan parasite fauna of marine and estuarine fishes of the coast of Yucatán, we studied specimens of M. curema from four coastal lagoons, with the objective of reporting the taxonomic composition of the parasites of this host species by using newly generated molecular data contrasted with some morphological features of the specimens. Additionally, we updated the checklist of the metazoan parasite fauna of M. curema along its distributional range.

Materials and methods

Host and parasite collection

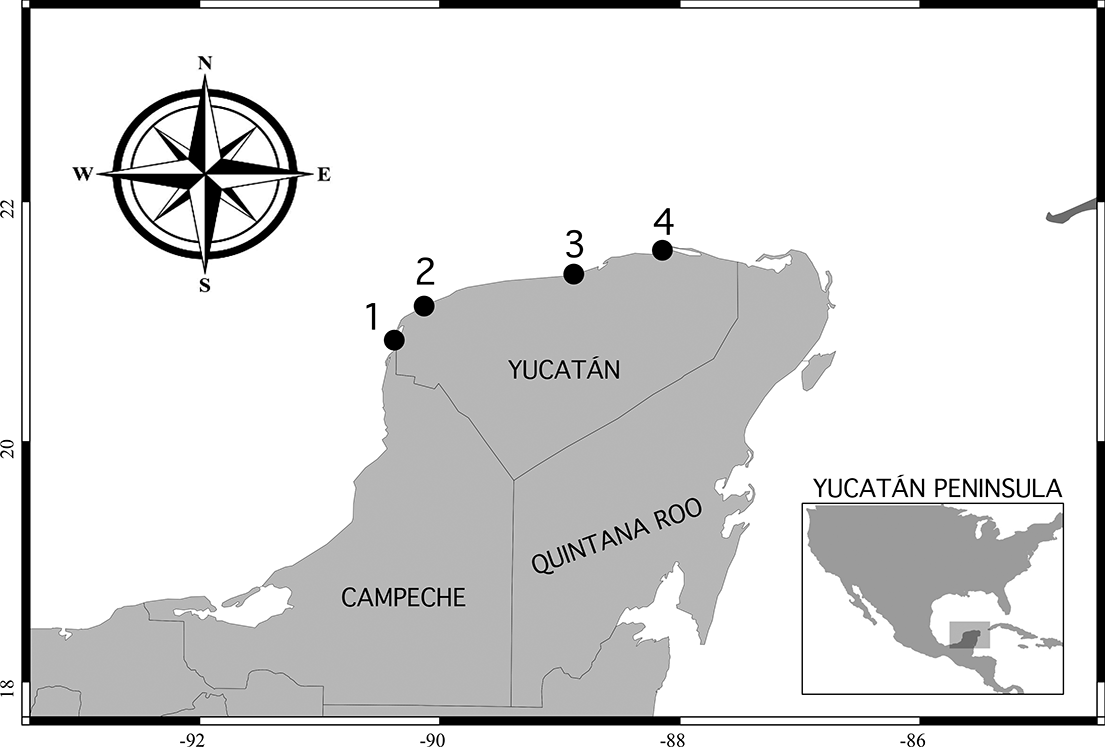

Seventy-three specimens of M. curema (7–33 cm, mean 17.1) were collected between May 2022 and January 2024, in four coastal lagoons of northern Yucatán that are not connected, i.e., Celestún (20° 50′ 53″N, 90° 24′ 22″W), La Carbonera (21° 08′ 01″N, 90° 07′ 55″W), Dzilam de Bravo (21° 23′ 39″N, 88° 53′ 20″W), and Ría Lagartos (21° 35′ 47″N, 88° 08′ 44″W) (Figure 1). Specimens were sampled under the collecting permit No. PPF/DGOPA-001/20, using seine and cast nets, kept alive, and transported to the laboratory for examination. Hosts were identified according to Gallardo et al. (Reference Gallardo-Torres, Badillo-Aleman, Rivera-Felix, Rubio-Molina, Galindo de Santiago, Loera-Pérez, García-Galano and Chiappa-Carrara2014). Individuals were euthanized by spinal severance (pithing) following the procedures accepted by the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA, 2020). The parasitological survey included the examination of the external surface. The eyes, gills, brain, gastrointestinal tract, heart, and liver were removed and placed in Petri dishes with 0.85% saline solution and examined for parasites using a stereomicroscope. The body cavity and muscle were thoroughly scrutinized for encysted parasites. Metazoan parasites were collected from each individual host except for myxozoans. Helminths were fixed in near-boiling saline and transferred to vials with 100% ethanol, whereas copepods were fixed in 70% ethanol.

Figure 1. Map indicating the sampled localities of Mugil curema collected in coastal lagoons in Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico.

Morphological study

In the laboratory, trematodes were stained with Mayer’s paracarmine and mounted on permanent slides with Canada balsam. Monopisthocotylans were mounted in Hoyer or Gray & Wess medium to study the sclerotized structures. Copepods were mounted in semi-permanent slides with 50% glycerine for morphological examination (Lamothe-Argumedo Reference Lamothe-Argumedo1997). Mounted specimens were examined and photographed under a bright-field Nikon DS-Ri1 microscope. Original descriptions or redescriptions were used to identify morphologically most of the metazoan parasites, i.e., Overstreet (Reference Overstreet1971); Ho and Lin (Reference Ho and Lin2009); Andrade-Gómez et al. (Reference Andrade-Gómez, Pinacho-Pinacho, Hernández-Orts, Sereno-Uribe and García-Varela2017, Reference Andrade-Gómez, Ortega-Olivares, Solórzano-García, García-Varela, Mendoza-Garfias and Pérez-Ponce de León2023, Reference Andrade-Gómez, da Silva and Pérez-Ponce de León2025); Louvard et al. (Reference Louvard, Cutmore, Yong, Dang and Cribb2022); González-García et al. (Reference González-García, García-Varela, López-Jiménez, Ortega-Olivares, Pérez-Ponce de León and Andrade Gómez2023); Andrade-Gómez and Pérez-Ponce de León (Reference Andrade-Gómez and Pérez-Ponce de León2024). Voucher specimens of 10 helminth species were deposited at the Colección Nacional de Helmintos (CNHE), and a voucher specimen of copepod species at the Colección Nacional de Crustaceos (CNAR), Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City. Finally, the infection parameters, i.e., prevalence, mean intensity, and intensity range, were estimated following Bush et al. (Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997).

Molecular analysis

To confirm the morphological identifications, the 19 sampled taxa were processed for molecular analyses including some hologenophores (Pleijel et al. Reference Pleijel, Jondelius, Norlinder, Nygren, Oxelman, Schander, Sundberg and Thollesson2008). Genomic DNA was isolated using the protocol of Andrade-Gómez et al. (Reference Andrade-Gómez, Ortega-Olivares, Solórzano-García, García-Varela, Mendoza-Garfias and Pérez-Ponce de León2023). For most taxa, the D1-D3 domains of the 28S rRNA were amplified by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) using the primers 391 (5′-AGCGGAGGAAAAGAA ACTAA-3′) and 536 (5′-CAGCTATCCT GAGGGAAAC-3′) (García-Varela and Nadler Reference García-Varela and Nadler2005). For the nematode, the cytochrome oxidase subunit II (COII) was amplified using 210 (5′-CACCAACTCTTAAAATTATC-3′) and 211 (5′-TTTTCTAGTTATATAGATTGRTTYAT-3′) (Nadler and Hudspeth Reference Nadler and Hudspeth2000). For the copepod the cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) was amplified using LCO1490 (5′-GGT CAA CAA ATC ATA AAG ATA TTG G-3′) and HCO2198 (5′-TAA ACT TCA GGG TGA CCA AAA AAT CA-3′) (Folmer et al. Reference Folmer, Black, Hoeh, Lutz and Vrijenhoek1994). PCRs (13 μL) consisted of 0.5 μL of each primer (10 μM), 2.5 μL of 10 m PCR Rxn buffer, 7.92 μL of water, 2 μL of genomic DNA, and 0.08 μL of MyTaq™ DNA Polymerase. PCRs were carried out in a MiniAmp Thermal Cycler using an amplification protocol that included an initial denaturation at 94ºC for 1 min, followed by 30 cycles at 94ºC for 1 min for denaturation; 50ºC for 28S and 44ºC for COI and COII for 1 min for annealing; and 72ºC for 2 min for extension, and post-amplification extension for 7 min at 72ºC. PCR products were visualized on a 1% agarose TAE gel using 6X TriTrack DNA Loading Dye. PCR products were treated with Exo-SAP (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and were sequenced by the Sanger method at the Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de México. Sequences obtained in this study were deposited in GenBank. Molecular identification was tested through a BLAST search (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) at NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

In this study, an arbitrary sequence identity value for the 28S rRNA gene ≥99% was considered valid to achieve a species-level designation. For COI and COII, a similarity threshold of ≥95% was applied for species-level identification. For those parasite taxa not identified to species-level based on the BLAST search, phylogenetic tree was built to show the phylogenetic position with respect to other members of their families. Five databases were constructed separately, four of them for 28S rDNA, i.e., Didymozoidae Monticelli, 1888; Haplosplanchnidae Poche, 1926; Hemiuridae Looss, 1899; and Bucephalidae Poche, 1907, and one for COI mtDNA, i.e., Bomolochidae Claus, 1875. The best-fit model of molecular evolution for each dataset was calculated with the jModel Test version 0.1.1 program (Posada Reference Posada2008) using the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The phylogenetic analyses were performed using maximum likelihood (ML) on CIPRES Science Gateway v3.3 (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Pfeiffer and Schwartz2010). The ML was carried out with the RAxML-HPC2 on ACCESS (8.2.12) (Stamatakis Reference Stamatakis2014), using 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Trees were drawn using FigTree v.1.3.1 (Rambaut Reference Rambaut2012).

Parasite checklist

The checklist reported in the present study contains information from Falkenberg et al. (Reference Falkenberg, de Lima, Vieira and Lacerda2022), and also, we included additional information published for M. curema since then, including Andrade-Gómez et al. (Reference Andrade-Gómez, González-García and García-Varela2021, Reference Andrade-Gómez, Ortega-Olivares, Solórzano-García, García-Varela, Mendoza-Garfias and Pérez-Ponce de León2023, Reference Andrade-Gómez, da Silva and Pérez-Ponce de León2025); Andrade-Gómez and Pérez-Ponce de León (Reference Andrade-Gómez and Pérez-Ponce de León2024); Fuentes-Olivares et al. (Reference Fuentes-Olivares, Rodríguez-Santiago, Garcés-García and Ávila-Torres2024); González-García et al. (Reference González-García, García-Varela, López-Jiménez, Ortega-Olivares, Pérez-Ponce de León and Andrade Gómez2023); Minaya et al. (Reference Minaya, Iannacone, Alvariño and Cepeda2021); Morales-Martínez et al. (Reference Morales-Martínez, Muñoz-García, Figueroa-Delgado, Chávez-Güitrón, Osorio-Saravia, Saavedra-Montañez, Martínez-Maya, Rubio and Villalobos2022); Morales-Serna and Camacho-Zepeda (Reference Morales-Serna and Camacho-Zepeda2024); Rosas-Valdez et al. (Reference Rosas-Valdez, Morrone, Pinacho-Pinacho, Domínguez-Domínguez and García-Varela2020); Santos-Gueretz et al. (Reference Santos-Gueretz, Barbosa-de Moura and Laterça-Martins2022); Vieira et al. (Reference Vieira, Agostinho, Negrelli, da Silva, de Azevedo and Abdallah2022, Reference Vieira, Osaki-Pereira, Abdallah, Oliveira, Duarte, da Silva and de Azevedo2024); Warren et al. (Reference Warren, Ksepka, Truong, Curran, Dutton and Bullard2024). Moreover, we incorporated records from two parasite databases of M. curema, i.e., the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), and the Colección Nacional de Helmintos (CNHE), Instituto de Biología, UNAM, Mexico City; finally, we added to the checklist all the new records of the present study.

Results

A total of 1,588 specimens of metazoan parasites were recovered from M. curema in 4 coastal lagoons of Yucatán, Mexico. These specimens represented 19 taxa including 1 monopisthocotylan, 15 trematodes, 1 acanthocephalan, 1 nematode, and 1 copepod (Table 1). Twelve of the 19 taxa were identified to species level using molecular and morphological data. In the BLAST search, sequenced specimens reached a percentage identity value ≥99% for LSU for most taxa, and ≥95% for COII in the nematode. The species identified were the monopisthocotylan Ligophorus yucatanensis Rodríguez-González, Míguez-Lozano, Llopis-Belenguer & Balbuena, 2015; the trematodes Sinistroporomonorchis minutus Andrade-Gómez, Ortega-Olivares, Solórzano-García, García-Varela, Mendoza-Garfias & Pérez-Ponce de León, 2023; S. yucatanensis Andrade-Gómez, Ortega-Olivares, Solórzano-García, García-Varela, Mendoza-Garfias & Pérez-Ponce de León, 2023; S. glebulentus (Overstreet, Reference Overstreet1971); Parasaturnius maurepasi (Overstreet, 1977); Saccocoelioides olmecae Andrade-Gómez, Pinacho-Pinacho, Hernández-Orts, Sereno-Uribe & García-Varela, 2016; Mesostephanus cubaensis Alegret, 1941; M. microbursa Caballero y C., Grocott & Zerecero, 1953; Ascocotyle (Phagicola) longa Ransom, 1920; Cardiocephaloides medioconiger (Dubois & Vigueras, 1949); the acanthocephalan Floridosentis mugilis (Machado Filho, 1951); and the nematode Contracaecum fagerholmi D’Amelio, Cavallero, Dronen, Barros & Paggi, 2012 (Table 1). In addition, in the BLAST search, the copepod showed an identity value of 85% for COI with Nothobomolochus gerresi Pillai, 1973 (MK643338); therefore, we built a phylogenetic tree to define their phylogenetic position; the specimens of copepods were also studied morphologically and closely resemble Bomolochus aff. nitidus Wilson C.B., 1911.

Table 1. Parasite species composition for Mugil curema in Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico

** Published either in Andrade-Gómez et al. (Reference Andrade-Gómez, Ortega-Olivares, Solórzano-García, García-Varela, Mendoza-Garfias and Pérez-Ponce de León2023, Reference Andrade-Gómez, da Silva and Pérez-Ponce de León2025) or González-García et al. (Reference González-García, García-Varela, López-Jiménez, Ortega-Olivares, Pérez-Ponce de León and Andrade Gómez2023).

Abbreviations: DS, Developmental stage; LC, life-cycle; GB, Genbank accession number; Identity BLAST, percent identity in BLAST; SI, site of infection; Specimens deposited either at the Colección Nacional de Helmintos (CNHE) or Colección Nacional de Crustaceos (CNAR).

Six taxa were not identified to species level, i.e., Hemiuridae gen. sp., Schikhobalotrema sp. 1; Schikhobalotrema sp. 2; Saccularina sp.; Bucephalus sp.; and Scaphanocephalus sp. (Table 1). With the exception of the latter, the phylogenetic position of these species was further tested through ML analyses. The 28S ML tree of the two new isolates of Hemiuridae gen. sp. formed an independent clade as the sister group of two major clades of hemiurids with strong nodal support. The first clade contained species of Hemiurus, Parahemiurus, and Myosaccium; and the second clade included species of Aphanurus, Lecithocladium, Elytrophalloides, Ectenurus, and Dinurus (Figure 2A). Regarding the adult haplosplanchnid trematodes, the four isolates of 28S were nested within the genus Schikhobalotrema in two independent clades, with high support values, suggesting two putative species. Two isolates (Schikhobalotrema sp. 1) were nested as the sister group of S. minuta + S. acutum, whereas the other two isolates (Schikhobalotrema sp. 2) were nested as the sister group of the clade formed by S. minuta + S. acutum + Schikhobalotrema sp. 1 (Figure 2B). Lastly, the three COI sequences of the adult copepod Bomolochus aff. nitidus were nested as the sister group of Bomolochus cuneatus, even though the genus Bomolochus resulted paraphyletic (Figure 2C). For the larval forms, the newly sequenced 28S isolates of the didymozoid trematode Saccularina sp. were nested as the sister group of Saccularina magnacetabulata (OL336033) with strong nodal support (Figure 3A). Finally, the newly sequenced isolate of the larval bucephalid trematode (Bucephalus sp.) was nested as the sister group of Bucephalus margaritae (Figure 3B).

Figure 2. Maximum likelihood trees showing the phylogenetic position of adult parasites of M. curema from Yucatán. (A) Hemiuridae gen sp.; (B) Schikhobalotrema spp. inferred with 28S rDNA. (C) Bomolochus aff. nitidus inferred with COI. Bootstrap support values >80 are indicated (*). Scale-bar = number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Figure 3. Maximum likelihood trees inferred with 28S rDNA showing the phylogenetic position of metacercaria of M. curema from Yucatán. (A) Saccularina sp.; (B) Bucephalus sp. Bootstrap support values >80 are indicated (*). Scale-bar = number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Overall, in this study, the parasite fauna included 2 ectoparasite taxa, i.e., the copepod Bomolochus aff. nitidus, and the monopisthocotylan Ligophorus yucatanensis, whereas 17 endoparasites were recovered from different organs of their hosts. The monopisthocotylan L. yucatanensis was present in the four sampled localities, and it is one of the most abundant; still, a low similarity of the parasite fauna of M. curema was found among localities (Supplementary Table S1). Of the 17 endoparasite taxa, 9 were adults, and 8 were larval forms. The adult endoparasites included one acanthocephalan (F. mugilis), and eight trematodes (P. maurepasi, Sa. olmecae, Si. minutus, Si. yucatanensis, Si. glebulentus, two putative species of Schikhobalotrema; and one taxon identified as Hemiuridae gen. sp). The larval endoparasitic forms corresponded to the nematode C. fagerholmi, and seven trematodes (C. medioconiger, A. (P.) longa, M. cubaensis, M. microbursa, Saccularina sp., Scaphanocephalus sp., and Bucephalus sp.) (Table 1). Overall, trematodes were the most species-rich group with 15 taxa recorded, including 8 adults and 7 metacercariae (Table 1; Figure 4).

Figure 4. Photomicrographs of some representative metazoan parasites of M. curema of the coasts of Yucatán Peninsula. Adult trematodes (A) Sinistroporomonorchis minutus; (B) Sinistroporomonorchis glebulentus; (C) Schikhobalotrema sp. 2; (D) Schikhobalotrema sp. 1 Hologenophore; (E) Hemiuridae gen sp. Hologenophore; (F) Saccocoelioides olmecae; Larval trematodes (G) Bucephalus sp.; (H) Cardiocephaloides medioconiger; Monopisthocotyla (I) Ligophorus yucatanensis; Copepoda (J) Bomolochus aff. nitidus. Scale bars: (A–D, F–I) 100 μm; (E) 500 μm; (J) 200 μm.

Discussion

In this study, 10 metazoan parasite taxa of M. curema were recorded for the first time, i.e., the trematodes Sa. olmecae, M. microbursa, M. cubaensis, C. medioconiger, Saccularina sp., Bucephalus sp., Schikhobalotrema sp. 1 and sp. 2, Hemiuridae gen. sp., as well as the nematode C. fagerholmi. In contrast, of the nine taxa previously recorded in M. curema, six were previously reported in Yucatán, i.e., Si. minutus, Si. yucatanensis, Si. glebulentus, L. yucatanensis, P. maurepasi, and Scaphanocephalus sp. (Andrade-Gómez et al. Reference Andrade-Gómez, Ortega-Olivares, Solórzano-García, García-Varela, Mendoza-Garfias and Pérez-Ponce de León2023; Reference Andrade-Gómez, da Silva and Pérez-Ponce de León2025; Andrade-Gómez and Pérez-Ponce de León Reference Andrade-Gómez and Pérez-Ponce de León2024; González-García et al. Reference González-García, García-Varela, López-Jiménez, Ortega-Olivares, Pérez-Ponce de León and Andrade Gómez2023). Furthermore, the copepod B. aff. nitidus, the acanthocephalan F. mugilis, and the metacercariae of Ascocotyle (Phagicola) longa represent a new locality record for this host (Morales-Serna et al. Reference Morales-Serna, Gómez and Pérez-Ponce de León2012; Rosas-Valdez et al. Reference Rosas-Valdez, Morrone, Pinacho-Pinacho, Domínguez-Domínguez and García-Varela2020; Scholz et al. Reference Scholz, Aguirre-Macedo and Salgado-Maldonado2001).

Species identification

Thirteen of the 19 metazoan parasite taxa recorded in this study were identified at the species level using morphological and molecular characters (Table 1). The only identified species that did not reach ≥95% for COI was the copepod Bomolochus aff. nitidus. Morphologically, the copepod resembles B. nitidus according to the key species proposed by Ho and Lin (Reference Ho and Lin2009). This copepod was originally described from M. cephalus in Beaufort, USA, and was also recorded in M. curema from two estuaries in northeastern Brazil (Golzio et al. Reference Golzio, Falkenberg, Praxedes, Coutinho, Laurindo, Pessanha, Madi, Patricio, Vendel, Souza, Melo and Lacerda2017; Wilson Reference Wilson1911). However, it is possible that the newly sampled specimens represent a new species since they exhibit some characteristics not reported previously, such as the presence of nonplumose setae in the basal joint of the fifth leg; this trait was not described by Wilson (Reference Wilson1911) in the original description. Still, a proper description of the species will require sampling and sequencing specimens of B. nitidus from the type locality to corroborate whether the specimens of the present study are conspecific. Interrelationships within the Bomolochidae Claus, 1875 also need a further assessment as recently suggested by Swaraj et al. (Reference Swaraj, Reshmi, Rijin, Drisya, Jose-Priya and Kappalli2025).

The three unidentified trematodes (Hemiuridae gen. sp., and Schikhobalotrema sp. 1 and sp. 2) may represent new species, but more detailed taxonomic work is required to test the hypothesis, and formal species descriptions of these taxa will be presented separately. Interestingly, the hemiurid trematode morphologically resembles species in the genus Hysterolecitha Linton, 1919, which currently is considered a member of the family Bunocotylidae Dollfus, 1950 (WoRMS, 2025, Hysterolecitha Linton, 1910. Accessed at: https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=108770 on 2025-09-11) but see Duong et al. (Reference Duong, Cribb and Cutmore2023) who considered the genus belongs to the family Lecithasteridae Odhner, 1905. The type species, H. rosea Linton, 1910, was described from an acanthurid in the Gulf of Mexico, and one species, H. elongata Manter, 1931, was described from M. cephalus also from the Gulf of Mexico (see Overstreet et al. Reference Overstreet, Cook, Heard, Felder and Camp2009). Currently, no 28S rDNA sequences are available for any of the 22 species included in the genus. Even though the specimens sampled in the present morphologically resemble members of Hysterolecitha, the BLAST analysis of 28S surprisingly yielded a similarity with the hemiurid Brachyphallus crenatus (Rudolphi, 1802), and not even with any bunocotylid (nor a lecithasterid) deposited in GenBank; this was corroborated through the phylogenetic analysis, which showed that the specimens nest within the clade containing species of Hemiuridae (Figure 2A). Furthermore, the two lineages of Schikhobalotrema uncovered in this study differed 5% from S. acutum (Linton, 1910), a species widely distributed from the Gulf of Mexico to the Indo-West Pacific (Pérez-Ponce de León et al. Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Solórzano-García, Huston, Mendoza-Garfias, Cabañas-Granillo, Cutmore and Cribb2023, KY852464). The phylogenetic analyses showed that they actually represent two independent lineages, and it is possible that they also represent undescribed species.

For some of the larval forms reported in the present study, including Saccularina sp., Bucephalus sp., and Scaphanocephalus sp., sequence data did not match any 28S rDNA sequence available in the GenBank dataset, and, morphologically, adult forms are required to accomplish the identification to species level. Instead, five larval forms were identified because their sequences matched those available in GenBank. Our findings corroborate the importance of using morphological and molecular data for the correct identification of parasite larval forms, as pointed out previously by Grano-Maldonado et al. (Reference Grano-Maldonado, Andrade-Gómez, Mendoza-Garfias, Solórzano-García, García-Pantoja, Nieves-Soto and Pérez-Ponce de León2023) and Espínola-Novelo et al. (Reference Espínola-Novelo, Solórzano-García, Guillén-Hernández, Badillo-Alemán, Chiappa-Carrara and Pérez-Ponce de León2023, Reference Espínola-Novelo, Solórzano-García, Badillo-Alemán, Chiappa-Carrara, Guillén-Hernández and Pérez-Ponce de León2025).

Infection parameters and comparison among localities

The prevalence of infection of parasite populations was relatively low in all sampled localities, with most taxa having prevalence less than 50%, although we acknowledge that host sample size is variable among localities. Irrespective of the fact that a relatively low similarity in species composition was found among localities. Two parasite taxa were recorded in the four localities analysed, whereas six taxa were recorded in only one locality. Ligophorus yucatanensis, one of the more frequent and abundant parasites, was sampled in all four localities. Overall, in each of the sampled localities, a different species reached the highest prevalence and mean intensity values (Supplementary Table S1). A similar pattern was observed in other fish species studied in the same coastal lagoons of Yucatán, such as the checkered puffer, Sphoeroides testudineus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Pech et al., Reference Pech, Vidal-Martínez, Aguirre-Macedo, Gold-Bouchot, Herrera-Silveira, Zapata-Pérez and Marcogliese2009). This cannot be considered as a general pattern because in other studies conducted in fundulids and cyprinodontids in the same coastal lagoons (see Espínola-Novelo et al., Reference Espínola-Novelo, Solórzano-García, Guillén-Hernández, Badillo-Alemán, Chiappa-Carrara and Pérez-Ponce de León2023, Reference Espínola-Novelo, Solórzano-García, Badillo-Alemán, Chiappa-Carrara, Guillén-Hernández and Pérez-Ponce de León2025), parasite communities are dominated by two species, which occur in all localities and exhibit the highest prevalence and abundance values. This might be a result of the position that species occupy in the food web in these ecosystems. Fundulids and cyprinodontids are small-sized fish that are highly consumed by fish-eating birds. The two common and abundant parasite species in these hosts close their life cycle when birds feed on them, and this may disperse the infection more effectively among coastal lagoons (Espínola-Novelo et al. Reference Espínola-Novelo, Solórzano-García, Guillén-Hernández, Badillo-Alemán, Chiappa-Carrara and Pérez-Ponce de León2023, Reference Espínola-Novelo, Solórzano-García, Badillo-Alemán, Chiappa-Carrara, Guillén-Hernández and Pérez-Ponce de León2025). Instead, parasite larval forms of M. curema and S. testudineus are not dispersed among localities at the same rate since they are not highly consumed by fish-eating birds.

Species composition

The white mullet is a secondary consumer in the food web (Paperna and Overstreet Reference Paperna, Overstreet and Oren1981; Whitfield Reference Whitfield, Crosetti and Blaber2016). The composition of the parasite fauna corroborates that position of the host in the food webs of coastal ecosystems; 68% of the species represented autogenic species, i.e., adult forms whose life cycle is completed in the aquatic ecosystem, whereas 32% were allogenic species, i.e., larval forms that require the fish to be consumed either by a mammal or a fish-eating bird to complete their life cycle. Two parasite species of the white mullet, Saccularina sp. and Bucephalus sp., complete their life cycle when the fish is eaten by a larger fish species, whereas the remaining larval forms complete their life cycle when the fish is eaten by a bird or a mammal (Costa-Marchiori et al. Reference Costa-Marchiori, Magenta-Magalhães and Pereira-Junior2010; Cribb et al. Reference Cribb, Barker and Beuret1995; D’Amelio et al. Reference D’Amelio, Cavallero, Dronen, Barros and Paggi2012; Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Fernández, Valente, Cremer, Castilho and Silva2020; González-García et al. Reference González-García, García-Varela, López-Jiménez, Ortega-Olivares, Pérez-Ponce de León and Andrade Gómez2023; Hernández-Mena et al. Reference Hernández-Mena, García-Prieto and García-Varela2014; Louvard et al. Reference Louvard, Cutmore, Yong, Dang and Cribb2022; Nadler et al. Reference Nadler, D’Amelio, Dailey, Paggi, Siu and Sakanari2005; Ondračková et al. Reference Ondračková, Hudcová, Dávidová, Adámek, Kašný and Jurajda2015; Pina et al. Reference Pina, Barandela, Santos, Russell-Pinto and Rodrigues2009).

Some previous studies have documented the diversity of metazoan parasites of M. curema in coastal lagoons in distant geographical areas across the Americas; at least three studies have been conducted in Brazil, three in Mexico, and one in Peru. The findings of our study are compared with those of other studies. For instance, Fajer-Ávila et al. (Reference Fajer-Ávila, García-Vásquez, Plascencia-González, Ríos-Sicairos, García de la Parra and Betancourt-Lozano2006) reported the presence of seven parasite taxa in 292 specimens of M. curema (mean length 21.2 cm) sampled in 2 costal lagoons in Northwestern Mexico; Minaya et al. (Reference Minaya, Iannacone, Alvariño and Cepeda2021) studied 25 specimens of the species (mean length 30 cm) from one locality of Peru, and reported only four taxa; Morales-Martínez et al. (Reference Morales-Martínez, Muñoz-García, Figueroa-Delgado, Chávez-Güitrón, Osorio-Saravia, Saavedra-Montañez, Martínez-Maya, Rubio and Villalobos2022) studied 122 specimens of M. curema (mean length 19.3 cm) from a lagoon in the Southwestern Pacific coast of Mexico, and reported only two species. Santos-Gueretz et al. (Reference Santos-Gueretz, Barbosa-de Moura and Laterça-Martins2022) studied 282 specimens of M. curema in one locality of the northern coast of Brazil and reported 5 taxa. Falkenberg et al. (Reference Falkenberg, de Lima, Vieira and Lacerda2022) studied 60 individuals of this host species (mean length 22.8 cm) also in one locality of Brazil, reporting 16 parasite taxa. Lastly, Fuentes-Olivares et al. (Reference Fuentes-Olivares, Rodríguez-Santiago, Garcés-García and Ávila-Torres2024) analysed 131 individuals of this mugilid (mean length 31.7 cm) from one locality of Veracruz, in the Gulf of Mexico, and reported six parasite taxa (see Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the metazoan parasites of Mugil curema based on studies conducted in estuarine environments across the Americas

In the present study, 19 metazoan parasite taxa were found in 73 individuals of M. curema (mean length 17.1, 7–33 cm) (Table 2). The parasite species richness herein reported is similar to that reported by Falkenberg et al. (Reference Falkenberg, de Lima, Vieira and Lacerda2022) in one locality in Brazil (n = 60; mean length 22.8 cm), although they differ overall in the species composition. For example, these authors reported the presence of eight copepod species, whereas the present study reported only one species (B. aff. nitidus). Instead, here 15 trematode taxa were reported, whereas Falkenberg et al. (Reference Falkenberg, de Lima, Vieira and Lacerda2022) reported only two. Interestingly, the taxonomic composition of the parasite fauna of M. curema of this study also differs from that of a study conducted in a relatively closer locality in the Gulf of Mexico, not only in species richness but also in species composition. Fuentes-Olivares et al. (Reference Fuentes-Olivares, Rodríguez-Santiago, Garcés-García and Ávila-Torres2024) analysed M. curema from Tuxpan, Veracruz, but they only reported the presence of six taxa, and the acanthocephalan Floridosentis mugilis is the only parasite species shared between both studies (Table 2). Only seven out of 48 metazoan parasite taxa listed on Table 2 are recorded in two or more localities, i.e., Ascocotyle (Phagicola) longa, Floridosentis mugilis, Ergasilus lizae, Ergasilus sp., Caligus sp., Lernaeopodidae gen. sp., and Contracaecum sp. This might suggest that only these parasites possess a strong association with M. curema regardless of the location, although only three are identified up to species level (Fajer-Ávila et al. Reference Fajer-Ávila, García-Vásquez, Plascencia-González, Ríos-Sicairos, García de la Parra and Betancourt-Lozano2006; Falkenberg et al. Reference Falkenberg, de Lima, Vieira and Lacerda2022; Fuentes-Olivares et al. Reference Fuentes-Olivares, Rodríguez-Santiago, Garcés-García and Ávila-Torres2024; Minaya et al. Reference Minaya, Iannacone, Alvariño and Cepeda2021; Morales-Martínez et al. Reference Morales-Martínez, Muñoz-García, Figueroa-Delgado, Chávez-Güitrón, Osorio-Saravia, Saavedra-Montañez, Martínez-Maya, Rubio and Villalobos2022; Santos-Gueretz et al. Reference Santos-Gueretz, Barbosa-de Moura and Laterça-Martins2022); it is uncertain whether or not the lernaeopodid copepod and the larval Contracaecum represent a single and widely distributed species. At this time, it is not possible to describe a general pattern.

Moreover, Falkenberg et al. (Reference Falkenberg, de Lima, Vieira and Lacerda2022) performed the first checklist of the metazoan parasites of M. curema. These authors compiled all the available information until 2022 and listed 88 parasite taxa. The bibliographical search conducted in the present study yielded 44 additional records of metazoan parasite taxa. These records, plus the additional 10 provided in the present study from Yucatán coastal lagoons, raised the known number of metazoan parasites of M. curema to 142 taxa (Table 3). An updated checklist was then performed, including the novel information provided in this study. The list includes 9 myxozoans, 65 trematodes, 18 monogeneans, 2 cestodes, 6 acanthocephalans, 9 nematodes, 2 hirudineans, 27 copepods, 3 malacostracans, and 1 ichthyostraca (Table 3). Considering the wide distribution range of the white mullet and the number of studies published describing their parasite fauna, it seems possible to postulate that more species will be found in further studies. The use of several sources of information, including molecular markers, will be useful to increase the number of species records for this host species. Here, the use of molecular data in combination with some morphological characteristics (Figure 4) was fundamental to identify 10 taxa, which are reported for the first time in this host species (one nematode and nine trematodes). In that context, our study contributes to the understanding of the parasite diversity of an economically important fish species with a wide distribution range. We pose that studies designed to provide baseline information for the analysis of data regarding the ecosystems where hosts and parasites live are very important, as it is now highly recognized that parasites play an important role in all ecosystems, and they provide valuable information about aquatic ecosystem health within the context of environmental parasitology (see Sures et al. Reference Sures, Nachev, Schwelm, Grabner and Selbach2023); the information we have generated in this study will be useful in further studies of parasites as bioindicators of the ecosystem health, and studies of the role of parasites in food webs in coastal lagoons.

Table 3. List of metazoan parasites recorded in Mugil curema across its distributional range

Abbreviations: AC, Atlantic Coast; Bra, Brasil; CS, Caribbean Sea; Cur, Curazao; Ecu, Ecuador; GoM, Gulf of Mexico; Mex, Mexico; MS, Mediterranean Sea; Nig, Nigeria; PC, Pacific coast; Pe, Perú; PR, Puerto Rico; Sen, Senegal; SLE, Sierra Leone; USA, United States; Ven, Venezuela.

Sources: (1) Falkenberg et al. (Reference Falkenberg, de Lima, Vieira and Lacerda2022); (2) WoRMS (2025); (3) CNHE (2024); (4) Present work.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X25101065.

Acknowledgements

LAG thanks SECIHTI for the postdoctoral fellowship ‘Estancias Posdoctorales por México Modalidad Académica’ (CVU 640068). We thank Luis García Prieto for providing the updated database of Mugil curema from the CNHE. We sincerely thank Alfredo Gallardo Torres, Laboratorio de Biología de la Conservación, Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM, for lab facilities and the identification of hosts. We are grateful to Laura Marquez and Nelly López, LaNaBio, for their help with sequencing DNA. We thank Norberto Colín for allowing us to use the Molecular Biology lab of ENES-Mérida.

Financial support

This research was supported by grants from the Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Inovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT-UNAM IN200824 to GPPL; IN204425 to MGV; IG201121 and IN205425 to XCC).

Competing interests

None.

Study permits

Fish were sampled under the collecting permit No. PPF/DGOPA-001/20 issued to Alfredo Gallardo by the Comisión Nacional de Acuacultura y Pesca. Fish were humanely euthanized following the protocols described by the 2020 edition of the AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals.