1 China and the Evolution of the Global Economic Order

China’s rise has given new momentum to the decades-long calls from across the Global South for a more balanced world economic order. In October 2024, the expanded Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) coalition, now significantly larger than the economies of the Group of 7 (G7), met to build alternatives to the World Bank (WB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and international payment systems, and to reform the Western-led ‘legacy’ institutions. A month earlier, fifty heads of African states traveled to Beijing to seek financing for infrastructure and clean energy from China’s two global ‘policy banks’, the China Development Bank and the State Export-Import Bank of China. A year before, China hosted the tenth anniversary of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), celebrating the over US$1 trillion invested in the Global South and Europe, and committed to a new wave of investment, especially for green development. Heads of state in attendance from across the Global South, along with the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General, applauded the BRI and collectively called for deeper reforms of the global economic order.

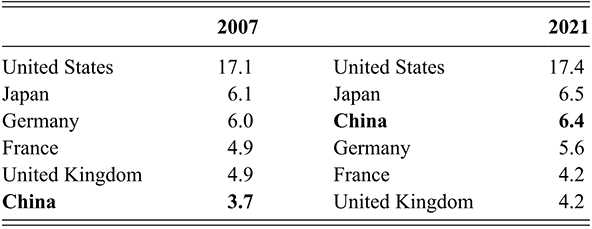

This Element traces the role of China in re-making the rules, norms, authority patterns, and institutional arrangements that make up the established Bretton Woods system. The analysis highlights China’s role in establishing key elements of an extended transition or transformation to the emerging global economic order.Footnote 1 Our analytical starting point is that we are in the interregnum phase of an extended period of world order change, which is giving rise to a new global economic order that entails either a fundamental remaking of the Bretton Woods system or even more profound changes that can be called ‘post-Bretton Woods’. By ‘rules’, we mean explicit, formal, legally binding arrangements, whereas we understand ‘norms’ as implicit, widely shared expectations about appropriate behavior, though not legally binding, such as voluntary codes of conduct or shared intersubjective understandings. Both rules and norms, especially when reinforced through institutions, are conceived as crucial for ordering behavior, social reality outcomes, and authority patterns in international organization (Finnemore and Sikkink, Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998; Barnett and Finnemore, Reference Barnett and Finnemore2004).

We center on the Bretton Woods institutions (BWIs) forged at the UN Monetary and Financial Conference held in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in 1944, where the Allied representatives met to undertake the unprecedented endeavor of planning the international economic order (Frieden, Reference Frieden, Lamoreaux and Shapiro2019). The resulting BWIs – the dollar-gold standard, IMF, and WB – formed the core of the post-World War II global economic order that aimed to maintain peace through stable and shared growth and prosperity. At first, the Bretton Woods regime seemed to preside over two decades of robust world trade and growth with relative financial stability, though more so in higher-income economies. The system came under immense pressure at the end of the 1960s as the United States ran persistent current account deficits and exposed the limits of the IMF to manage the system of dollar-gold pegged exchange rates. In 1971, the United States suspended the convertibility of the dollar into gold and abandoned it in 1973 (Eichengreen, Reference Eichengreen2019).

As the dollar-gold standard and fixed exchange rate regime came to an end, the BWIs shifted from “embedded liberalism,” whereby markets are embedded within rules and norms to promote stability, cooperation, full employment, and equity, to become the standard-bearers of “neo-liberalism” that favored the reduction of the state in economic affairs over more universal, private market-determined approaches to welfare. In the midst of this global policy and regulatory transformation, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) assumed the seat of “China” at the IMF and the WB in 1980. China embarked on an extended period of market reforms and opening to the world economy during the 1980s and 1990s. China’s membership in these institutions was largely beneficial for both China and the global economy. The BWIs cannot take full credit for China’s growth miracle by any means, but they did provide substantial policy advice, technical assistance, and financing that supported China’s economic reforms (Jacobson and Oksenberg, Reference Jacobson and Oksenberg1990; Hu Reference Angang2004; Chin, Reference Chin2012). The assistance from the IMF and WB in supporting China’s growth and stability has proved indispensable for the West as well, as China’s global integration provided new markets, lower priced goods, and increased channels for diplomatic exchange (Kastner, Pearson, and Rector, Reference Kastner, Pearson and Rector2019).

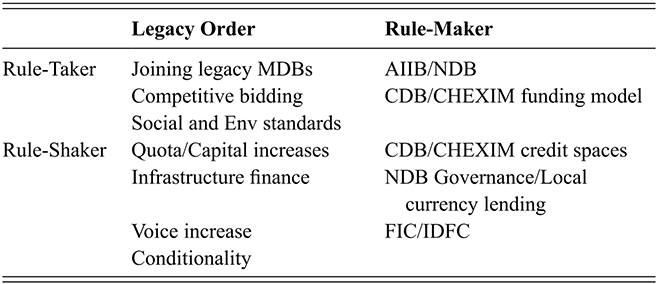

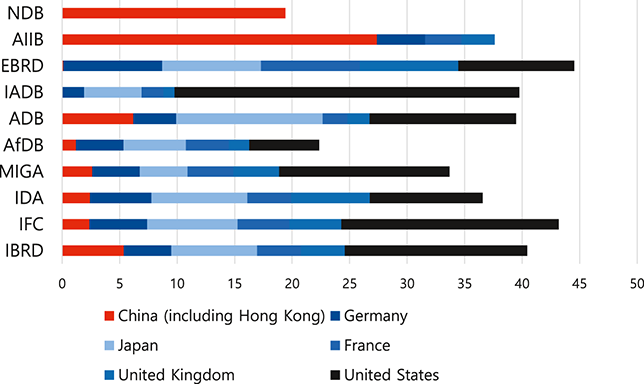

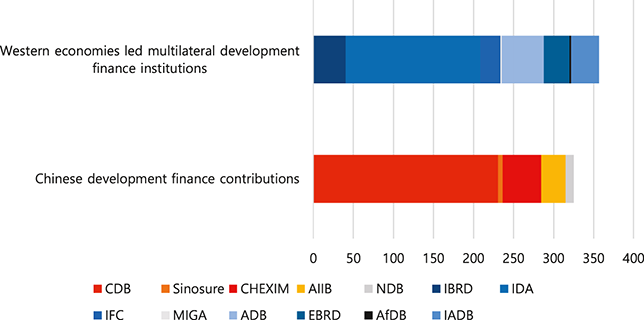

In this twenty-first century, we are seeing the emergence of a less-centralized, more fragmented, and globally diverse system. The US dollar, capital markets, and central banks still occupy the core of the monetary and financial systems in the advanced economies, and the IMF continues to serve as the main lender of last resort for most lower-income countries. Middle-income countries have pushed back on the North-South asymmetry as they work to create parallel institutions and policy space to determine domestic policies. Chief among those present at the creation of these alternative institutions is China. Parallel to the evolution of the BWIs, China has established or co-established a number of international economic institutions that, cumulatively, have similar financial firepower and mirror the functions of the IMF and the WB. These institutions have spurred economic growth, provided emergency financing, and increased the agency of developing countries in international economic affairs.

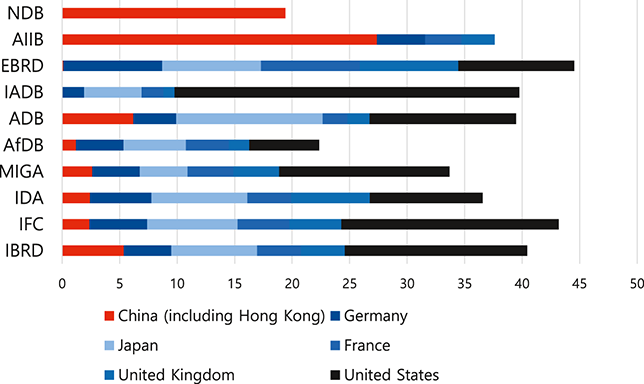

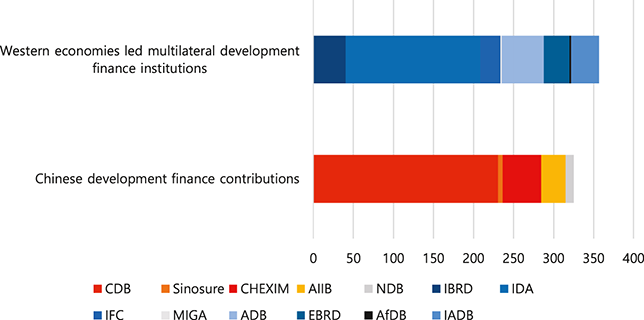

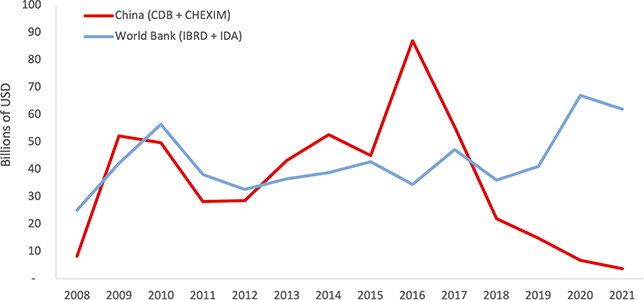

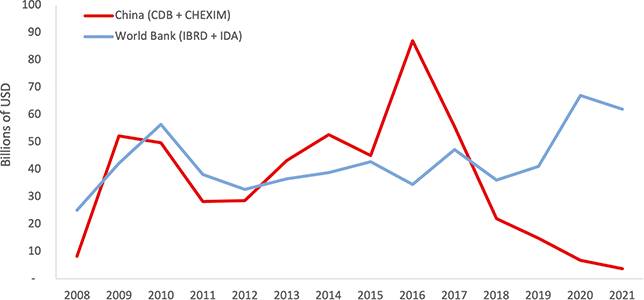

In the realm of global development finance, China’s two state policy banks – China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China – have provided roughly the same amount of financing to developing countries during the same time period as the WB (2008–2022). China played a leading role in establishing two new Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs): the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the BRICS-led New Development Bank (NDB). In the international monetary realm, China’s central bank helped to build an “Asian regional financial safety net,” known as the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization (CMIM), and, since 2008, China has supported the growing international use of its national currency, the renminbi (RMB), for trade finance and emergency financial support. China has also provided accompanying RMB currency swap lines for trade financing and liquidity support and has built a Cross-border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) for direct cross-border settlement of transactions using RMB. This new infrastructure is analogous to the US dollar payments system, comprising the US Federal Reserve-owned Fedwire, the private sector counterpart Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS), and the Society for Worldwide Inter-bank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), headquartered in Belgium.

Eighty years after their founding, the BWIs are under intense scrutiny for their lackluster responses to the international financial crises of the mid- to late-1990s and 2007–09, as well as their limited ability to respond to the increased prevalence of climate change, growing sovereign debt distress, the persistence of global economic inequities, pandemic preparedness, and for the lack of voice and representation for the majority of the membership that resides in the Global South. Inside the corridors of the BWIs, there is growing awareness of the need to reform the IMF and WB. Some Western governments have come around to supporting the reform of the institutions, including the United States, which had the largest hand in creating the BWIs and in maintaining them.

How has China’s role expanded inside the BWIs and outside? What are China’s motivations, interests, and goals inside the BWIs and outside? How have the BWIs responded to China and further engaged with China, and why? What have been the motivations among the Western powers, and how have their responses evolved over time in relation to China’s evolving behavior? Are Western governments motivated as enlightened hegemons, organically seeking to improve the provision of global public goods? Or are Western powers now seeing a growing “China threat” and competition from other Global South powers and pushing back? What is next?

Whereas earlier scholarship identified China largely as a “rule taker” inside the BWIs and accepting of the existing rules and established order, we argue that China has increasingly become a “rule-maker,” a creator of new rules, norms, and standards through the establishment of parallel institutions outside of the BWIs. This hybrid behavior has further enabled China to gain more influence as a “rule shaker” inside the BWIs. The hybrid positioning opens the door for China (and other Southern nations) to choose whether to remain engaged and pursue further reforms of the BWIs or focus instead on developing alternative rules, norms, and institutions outside the BWIs. Most countries in the Global South, so far, have tried to avoid making a binary choice between one or the other and have sought to benefit from engaging both inside and outside the BWIs. Through their hybrid efforts, China and other Southern nations are gradually bringing about transformational changes in the global economic order.

We see China’s hybrid positioning as an exercise of two-way countervailing power. By creating alternative institutions and coalitions outside of the BWIs, China has presented a credible possibility of exit from the BWIs, while these outside activities also simultaneously pave the way for China or others to leverage the extra-forum activity to pressure for changes in the rules, norms, and standards back inside the IMF and WB. At times, this phenomenon has been a conscious objective, and at others, a result of an increasingly integrated co-evolution. And at times, countervailing monetary power has also resulted from the interventions of others, including the representatives of Western nations motivated by a strategy to keep China inside the BWIs.

The majority of the literature in the social sciences has also depicted China as playing an “inside-outside” game to the betterment of China, while the implications for the system as a whole are still debated (e.g. Shambaugh, Reference Shambaugh2013; Wang, Reference Wang2018; Kastner, Pearson, and Rector Reference Kastner, Pearson and Rector2020; Friedberg, Reference Friedberg2022). However, the studies that have focused on China and the BWIs (Wang, Reference Wang2018; Kastner, Pearson, and Rector, Reference Kastner, Pearson and Rector2019; Malkin and Momani, Reference Malkin, Momani and Zeng2019) have tended to argue that despite whatever alternative institutional arrangements that China has fostered, these outside efforts are largely about China exerting influence back into the Bretton Woods systems, and as such, are ultimately status quo-oriented. By conceptualizing the countervailing power instead as two-way leverage, we suggest instead that China is increasing its influence within the BWIs, providing functions similar to the BWIs, but also creating alternative non-BWs institutional options and policy space, and paving a potential off-ramp from the BWIs in the event the BWIs are deemed no longer fit for purpose. Finally, we emphasize that the outcome of China’s exercise of hybrid positioning and two-way countervailing power is a gradual transformation towards a more balanced, multi-polar global economic order.

The Twentieth Century Global Economic Order

In his classic book, The World in Depression, economist and former statesman Charles Kindleberger argued that the Great Depression of 1929 spread from the United States to the rest of the world because the global community lacked a global leader and a set of rules that could provide five global public goods: a stable monetary and exchange rate system; a lender of last resort to provide liquidity to distressed nations; counter-cyclical and long-run public lending; open markets in recessions; and international policy coordination across these issues. Britain attempted a global economic conference in 1933 but failed to lead, as the rising United States also failed to step into the void. This interregnum triggered industrialized countries to erect trade barriers and implement beggar-thy-neighbor currency devaluations that drastically reduced international trade and foreign investment, hastening the global spread of the Great Depression and accentuating geopolitical tensions ahead of World War II.

It seemed, though, that the same mistake would not be made twice when, amid the great destruction of World War II, the United States hosted the 1944 UN Monetary and Financial Conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire (Helleiner, 2014a). US Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr., premised the negotiations on the notion that, “prosperity, like peace, is indivisible. We cannot afford to have it scattered here or there among the fortunate or to enjoy it at the expense of others. Poverty, wherever it exists, is menacing to us all and undermines the well-being of each of us. It can no more be localized than war, but spreads and saps the economic strength of all the more favored areas of the earth” (James, Reference James2012, 413). Under this rubric, those gathered rejected a return to the classical liberal order of the gold standard and the League of Nations, which forced countries to “adjust” to international payment fluctuations through austerity. Instead, a new set of institutions was built under what was termed “embedded liberalism,” whereby markets were rooted in domestic institutions geared toward promoting stable growth, social welfare, and full employment (Ruggie Reference Ruggie1982; Helleiner, Reference Helleiner1994; Eichengreen, Reference Eichengreen2019).

To this end, the cornerstone of the system that negotiators at Bretton Woods agreed upon was a fixed dollar-gold standard that allowed countries to deploy capital controls to provide insulation from external shocks and space for full employment policies, while also permitting countries to adjust their national currency-dollar-pegs in exceptional circumstances. Relatedly, the IMF was created to facilitate an orderly system of international payments at stable and adjustable exchange rates and regulated capital flows. Most importantly, the Fund was charged with providing short-term international liquidity to avoid deflationary adjustments and to maintain stable exchange rates during balance of payments shortages (Eichengreen, Reference Eichengreen2019). Under the Articles of Agreement that established the IMF, member states were assigned “quotas,” which were roughly based on the country’s share of international trade and gross domestic product (GDP). IMF quotas determined the amount of gold and dollars that each member had to contribute to the Fund, but also the relative amount of drawing and voting rights that a member could exercise.

The IMF was created to monitor the stability of the financial system and provide short-term liquidity support, whereas the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) was established to provide medium- to long-run post-war reconstruction and counter-cyclical development financing. It was commonly understood that the terms and conditions of private markets did not function in a counter-cyclical manner and that public investment was needed to repair war-torn Europe and later to raise living standards in developing countries. IBRD member countries contribute (paid-in and callable) capital roughly commensurate to their trade and GDP, determining their relative levels of voting power. This base capital is used as collateral to tap capital markets and on-lend to borrowing member states at cheaper rates (Humphrey, Reference Humphrey2022). The IBRD has since evolved into a “World Bank Group” that includes the IBRD (non-concessional financing), the International Development Association (IDA, highly concessional loans and grants), the International Finance Corporation (equity), the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, and the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes.

In addition to the economic and security rationale for establishing the BWIs, scholars have argued that negotiators also sought to correct governance failures at the global level. Kindleberger attributes the failure of the 1933 World Economic Conference in London to the decline of British hegemony (Kindleberger, Reference Kindleberger1973). By linking the fixed but adjustable gold standard to the United States dollar, and through the effective veto power derived from the quota and capital/voting system of the IMF and the IBRD, the Bretton Woods order essentially made the United States, and later the West, the hegemons of systemic stability in charge of the provision of international public goods. Later known as “hegemonic stability theory,” the idea was challenged by scholars within the Liberal Institutionalist canon, who argued that as long as members (including new members such as China) collectively adhered to the norms and rules of the system, a hegemon may not be necessary for the maintenance of the order, what political scientists refer to as “regime theory” (Keohane, Reference Keohane and Keohane1984). More critical scholars saw the same period as the making of the post-World War II US-centered hegemonic world order, combining the exercise of consensus (public goods provision) and coercion (military power), or structural power. Some have seen US hegemony as in crisis from the early 1970s onward, whereas others see the continuation of US dominance based on its assertion of inter-related structures of power (Cox, Reference Cox1987; Gilpin, Reference Gilpin1987; Strange, Reference Strange1987).

In the late-1940s and 1950s, the BWIs were primarily focused on the industrialized world but became more “global” in their institutional reach as former colonies gained independence and as the Cold War thawed in the 1990s. The period between the 1980s and the late 2000s is generally considered the era of “neo-liberalism” and the “Washington Consensus.” Since then, a debate has emerged between those who argue that US and Western hegemony has continued and those who see the world order as shifting toward a more pluralistic, diverse, fragmented, or multipolar order (Helleiner, Reference Helleiner2014; Drezner, Reference Drezner2014; Jones, Reference Jones2014; Alden and Vieira, Reference Alden and Vieira2005; Barma, Ratner, and Weber, Reference Barma, Ratner and Weber2007; Drezner, Reference Drezner2007a; Cox, Reference Cox and Schechter2002; Ikenberry and Inoguchi, Reference Ikenberry, Inoguchi, Ikenberry and Inoguchi2007; Cohen, Reference Cohen2008). Scholars who argue the latter perceive a diminution of US power and leadership and less widely accepted norms, rules, and institutions amid a greater mix of national and regional powers, more diverse sources of norms and influences, and corporate or societal actors, forming a less-centralized, more negotiated, messier, multi-centered world economic order (Kissinger, Reference Kissinger2010; Bremmer, Reference Bremmer2012; Kupchan, Reference Kupchan2012; Kirshner, Reference Kirshner2014; Acharya, Reference Acharya2017; Layne, Reference Layne2018).

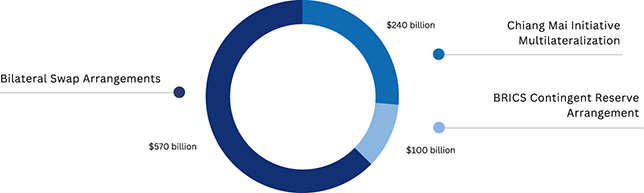

Since its onset in 1944, the Bretton Woods order has been evolving. The fiat US dollar still stands at the top of the global monetary pyramid, flexible exchange rates of varying degrees remain the norm, and international capital markets are the source of liquidity for most, except the poorest countries. From a multilateral perspective, the IMF – as the only institution with a global membership charged with maintaining global financial stability and still the holder of the largest emergency financing capacity – remains at the center of what is now referred to as the “Global Financial Safety Net” (GFSN). However, we also observe the emergence of a more multi-tiered and diverse GFSN that includes central bank swaps, regional financial arrangements (RFAs), newer contingent reserve arrangements, such as the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA), and national reserves. In terms of global development finance, the WB remains at the center of a system of MDBs that includes regional and inter-regional multilateral banks, which largely follow the WB financing and governance model. But we also see the emergence of newer self-styled “Southern development finance institutions” in the AIIB and NDB. National development banks and state policy banks also lend more internationally than the established MDBs. The Group of Twenty (G20), the resurrected G7, and the BRICS Plus grouping have emerged as the main informal consultative forums for the management of the global economy. The new and reshaped rules, norms, standards, and principles of this emerging global economic order are still heavily contested, as is the balance between efficiency and equity, and the degree of commitment to environmental sustainability. But their emergence can be tracked.

China and the Bretton Woods Institutions

China played a role in the formation of the post-World War II global economic order, represented by the Republic of China (1912–1949) at the Bretton Woods (BW) conference in 1944, and the People’s Republic of China (PRC, 1949 onward) has been a significant contributor since it officially assumed the seat of ‘China’ at the two main BWIs in 1980. The core strategic motive that has remained throughout China’s involvement with the BWIs is to learn and obtain what it needs to pursue its own national economic development objectives, without wholesale assimilation to the norms of the institutional order. Beijing has repeatedly stated that it is not seeking to undo or supplant the global order, but to re-balance it (Lin, Reference Lin, Lozoya and Bhattacharya1981; Gao, Reference Gao2023). For example, Liu Jianchao, head of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) International Department, recently told a US-based audience at the Council on Foreign Relations that, “China does not seek to change the current international order, still less reinvent the wheel by creating a new international order. We are one of the builders of the current world order and have benefited from it.” China’s goal, he said, was to “deliver a better life for the Chinese people” (Liu, Reference Liu2024).

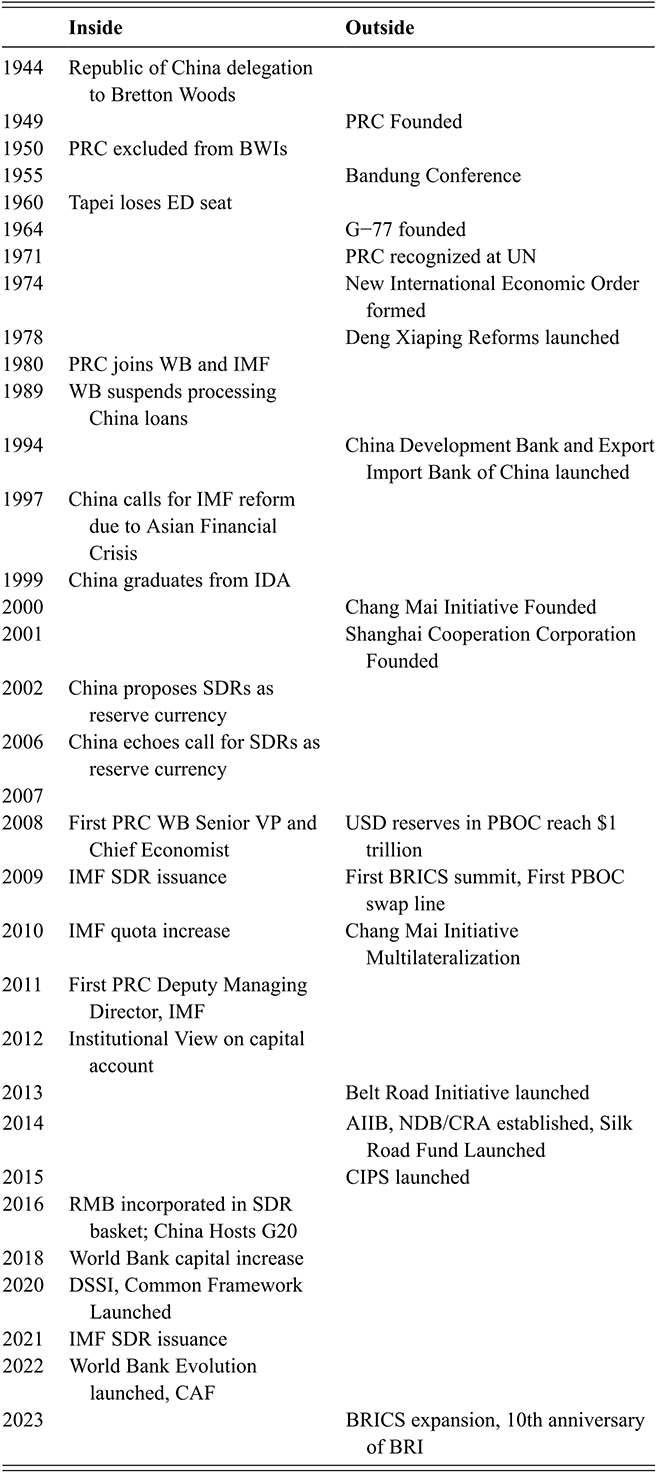

Whether the PRC is behaving solely or largely as a status quo actor, or, on balance, is behaving more as a system transformer, deserves further scrutiny. We address this question first by categorizing China’s related actions and the institutional outcomes as those inside the BWIs versus outside the BWIs. Next, we assess China’s behavior inside and outside the BWIs, and the resulting outcomes, using the rubric of “rule-taker,” “rule-maker,” and “rule-shaker.” We find that China is engaging in rule-making outside of the BWIs and rule-shaking inside the BWIs to such a degree that the rules and norms are being reshaped, and the global economic order is being incrementally transformed.

Table 1 provides a snapshot of the key moments of China’s engagement with the Bretton Woods order; subsequent sections will delve into more detail in tracing China’s evolving relations with each BWI institution. In the left-hand column, the table highlights the main elements of China’s involvement “inside” the BWIs. The right-hand column illustrates China’s major initiatives “outside” of the BWIs.

Table 1 Tracing China and the Bretton Woods Order

| Inside | Outside | |

|---|---|---|

| 1944 | Republic of China delegation to Bretton Woods | |

| 1949 | PRC Founded | |

| 1950 | PRC excluded from BWIs | |

| 1955 | Bandung Conference | |

| 1960 | Tapei loses ED seat | |

| 1964 | G−77 founded | |

| 1971 | PRC recognized at UN | |

| 1974 | New International Economic Order formed | |

| 1978 | Deng Xiaping Reforms launched | |

| 1980 | PRC joins WB and IMF | |

| 1989 | WB suspends processing China loans | |

| 1994 | China Development Bank and Export Import Bank of China launched | |

| 1997 | China calls for IMF reform due to Asian Financial Crisis | |

| 1999 | China graduates from IDA | |

| 2000 | Chang Mai Initiative Founded | |

| 2001 | Shanghai Cooperation Corporation Founded | |

| 2002 | China proposes SDRs as reserve currency | |

| 2006 | China echoes call for SDRs as reserve currency | |

| 2007 | ||

| 2008 | First PRC WB Senior VP and Chief Economist | USD reserves in PBOC reach $1 trillion |

| 2009 | IMF SDR issuance | First BRICS summit, First PBOC swap line |

| 2010 | IMF quota increase | Chang Mai Initiative Multilateralization |

| 2011 | First PRC Deputy Managing Director, IMF | |

| 2012 | Institutional View on capital account | |

| 2013 | Belt Road Initiative launched | |

| 2014 | AIIB, NDB/CRA established, Silk Road Fund Launched | |

| 2015 | CIPS launched | |

| 2016 | RMB incorporated in SDR basket; China Hosts G20 | |

| 2018 | World Bank capital increase | |

| 2020 | DSSI, Common Framework Launched | |

| 2021 | IMF SDR issuance | |

| 2022 | World Bank Evolution launched, CAF | |

| 2023 | BRICS expansion, 10th anniversary of BRI |

As the following sections will outline, the PRC’s engagement and relationship with the IMF can be defined as “highly professional,” though less convivial than with the World Bank. Jacobson and Oksenberg (Reference Jacobson and Oksenberg1990) were the first to conduct a detailed analysis of China and the BWIs and concluded: “At least in the first decade of its unfolding, the initial inclusion of China into the keystone International Economic Institutions was successful, judged by the standards of both sides. By and large, China abided by the rules that other large developing countries accepted. Moreover, China made discernible contributions to the operations of the BWIs as well” (17). Inside the BWIs, China’s “rule-taking” was and is manifested, first and foremost, by accepting the US dollar-denominated world economy. China’s trade, investment, and even its development assistance loans as a recipient were largely conducted in dollars. China also accepted the IMF’s surveillance activity and has internalized many of the IMF’s policy lessons, norms, and standards into its macroeconomic management, as well as its fiscal and financial systems.

Nonetheless, from the outset of its membership, China did not support the Fund’s policy conditionality that called for slashing government spending and reducing the role of the state in economic affairs – a position that became even more steadfast following the IMF’s disastrous record during the Asian Financial Crisis (Jacobson and Oksenberg, Reference Jacobson and Oksenberg1990; Helleiner and Momani, Reference Helleiner, Momani, Helleiner and Kirshner2014; Nolan, Reference Nolan2021). To avoid conditionality, China has only taken technical assistance loans from the IMF. Throughout its history, China has called for greater voice and representation of developing countries and reform of IMF conditionality. As a participant in coalitions with East Asian countries, and later the BRICS, the PRC played a key role in reforming rules such as a 2010 increase in quotas – and thus, voting power – for China and others, as well as the IMF’s updated stance on capital account liberalization and capital controls in 2012 (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2015; Grabel, Reference Grabel2018; Roberts, Armijo, and Katada, Reference Roberts, Armijo and Katada2018; Kastner, Pearson, and Rector, Reference Kastner, Pearson and Rector2019). Since 2011, a PRC national has been appointed to a Deputy Managing Director position at the IMF. In addition to increasing quotas at the IMF, China has succeeded in being a voice for other rule changes, such as increasing the size of the GFSN through issuances of the IMF’s reserve accounting tool, Special Drawing Rights (SDR), and for expanding the use of the SDR as a reserve management tool. On a number of occasions, China has gone so far as to call for an increased role for the SDR and a reduced role for the US dollar as the de facto global settlement and reserve currency (Chin, Reference Chin2014; Helleiner and Momani, Reference Helleiner, Momani, Helleiner and Kirshner2014). China also successfully lobbied the IMF membership for the RMB to be included in the SDR reserve basket in 2016 (Wang, Reference Wang2018; Kastner, Pearson, and Rector, Reference Kastner, Pearson and Rector2019). The United States has resisted increased use of SDR, seeing expanded use as a potential threat to dollar supremacy and US political objectives at the IMF.

In terms of global development finance, China’s engagement inside the World Bank has been comparatively convivial, particularly during the 1980s and 1990s when China was “learning” the norms, rules, and standards of the World Bank and undergoing “socialization” (Jacobson and Oksenberg, Reference Jacobson and Oksenberg1990; Johnston, Reference Johnson2008). During its first-two decades as a member of the World Bank, China absorbed economic reform policy advice and lessons from pragmatic experts willing to work within the economic policy limits of China’s Communist Party-state-led system, including maintaining a role for state companies while also supporting the growth of the private sector (Bottelier, Reference Bottelier2007). During the 1980s and 1990s, China and the Bank co-produced numerous studies on economic reform that helped Chinese officials chart their own reform path, including future Premier Zhu Rongji. Moreover, China benefited from numerous World Bank (and Asian Development Bank) concessional loans before “graduating” from IDA in 1999.

Despite the rather warm relations, as we will show in our section on the World Bank and development finance, China has played a strong hand and succeeded in changing the Bank’s norms and rules. For example, China was able to avoid adopting many of the “shock therapy” and “Washington Consensus” suite of rapid privatization and marketization policies that other developing countries had to accept to receive World Bank financing (Bottelier, Reference Bottelier2007). Indeed, even as China was engaging constructively with the BWIs and has continued to “learn” and absorb from the BWIs, it has also taken part in efforts to reform the BWIs, constructed its own set of institutions, and joined other Southern-led coalitions to push for changes to the BWIs.

Starting in the late 1990s, China began to work outside the BWIs to address international monetary and global development finance needs that were largely unmet or left unaddressed by the BWIs and the Western powers. On the monetary front, working outside of the IMF, China co-founded the Chiang Mai Initiative in 2000, together with the ten ASEAN nations, Japan, and South Korea (“ASEAN+3”), to provide a regional emergency liquidity fund operated by and for East Asian member countries. ASEAN+3 boosted the reserve pool of the Chiang Mai Initiative in 2010 to $240 billion, and China, in turn, supported the creation of a similar “Contingent Reserve Arrangement” with the BRICS nations in 2014. What is more, like many of its East Asian counterparts, China has amassed large national foreign exchange reserves to self-insure and insulate itself from financial instability and reliance on the IMF. China’s national reserves reached US$1 trillion in 2007, topped out at an unprecedented $4 trillion in 2014, and now stand at over US$3 trillion. China also began to support the growing international use (“internationalization”) of its national currency, the renminbi (RMB), in 2008, creating and launching its own cross-border RMB direct payments system, the CIPS, in 2015. The new rules of these alternative institutional arrangements are detailed in Section 2.

Operating outside of the World Bank, China has also played a major role in expanding development financing globally. In 1994, China established the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM), mainly to provide domestic lending for the country’s national development and concessional state policy-related trade financing, respectively. Two decades later, CDB and CHEXIM are among the largest development lenders in the world, and from 2010–2020, they provided more financing to developing countries than the World Bank. These two banks, alongside China’s Silk Road Fund, are the flagship institutions for China’s outbound development finance, including financing Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects, the ambitious pan-regional connectivity stratagem that China launched in 2013. These financial institutions, together with China’s state commercial banks, have provided upwards of US$1 trillion in financing to BRI partner and developing countries.

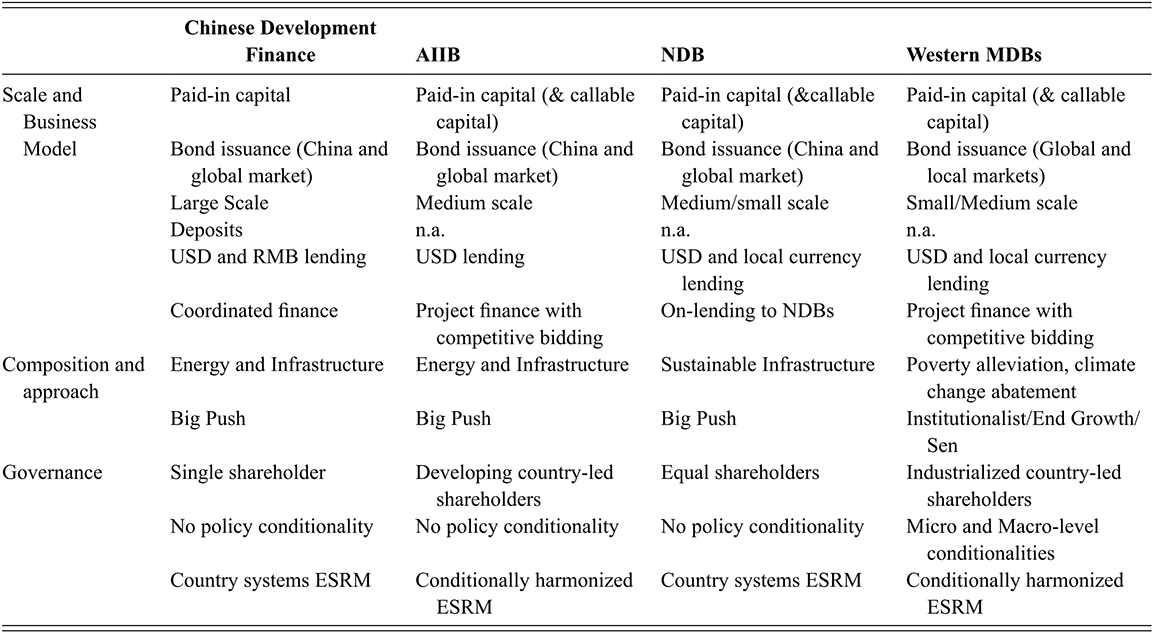

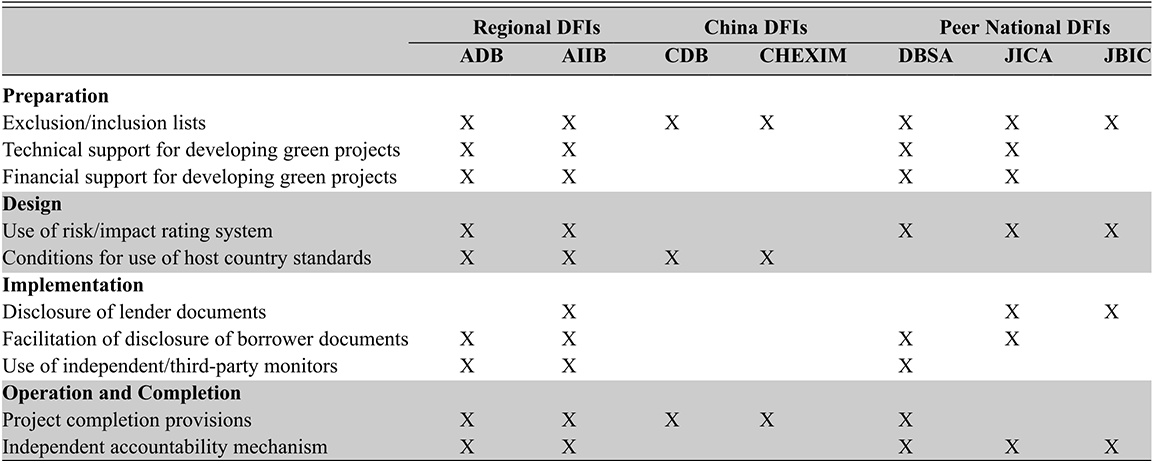

Furthermore, China has helped establish two new MDBs: the BRICS-led NDB and the 109-member AIIB, launched in 2015 and 2016, respectively. In Table 1 and Table 2, we list the creation of AIIB and NDB as examples of China acting as a rule-maker outside the BWIs, as these alternative institutions exhibit a spectrum of new and existing rules and norms. Some of their other rules are almost the same as those of the Western-dominated BWIs, but with China at the center of the table at the AIIB. However, even in the AIIB, and especially with the NDB, we see examples of norms and rules that differ from the BWIs, such as South-South cooperation and alternative rules whereby the founding BRICS member-countries each make equal financial contributions and hold equal votes in the NDB, despite differences in the respective sizes of their national economies. Furthermore, the NDB, as well as China’s state policy banks, allow a higher degree of policy autonomy for borrowers, unlike the Western-dominated BWIs. For example, the NDB and CDB both operate according to “host country standards,” for environmental, social, and governance (ESG) safeguards. Finally, the CDB and China’s central bank both support the norm of counter-cyclical financing, especially in emergency crisis scenarios, whereas the IMF has a sustained history of supporting and demanding fiscal consolidation and austerity, that is, pro-cyclical measures in both crisis and normal scenarios.

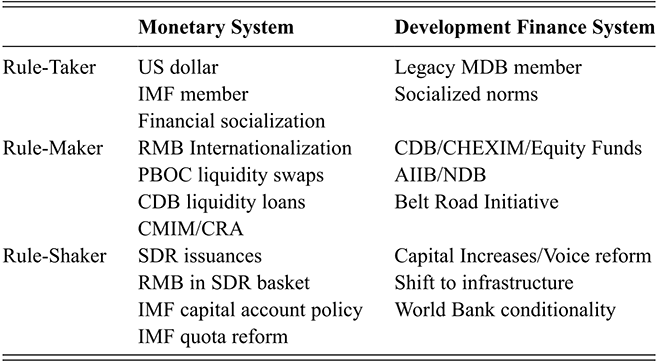

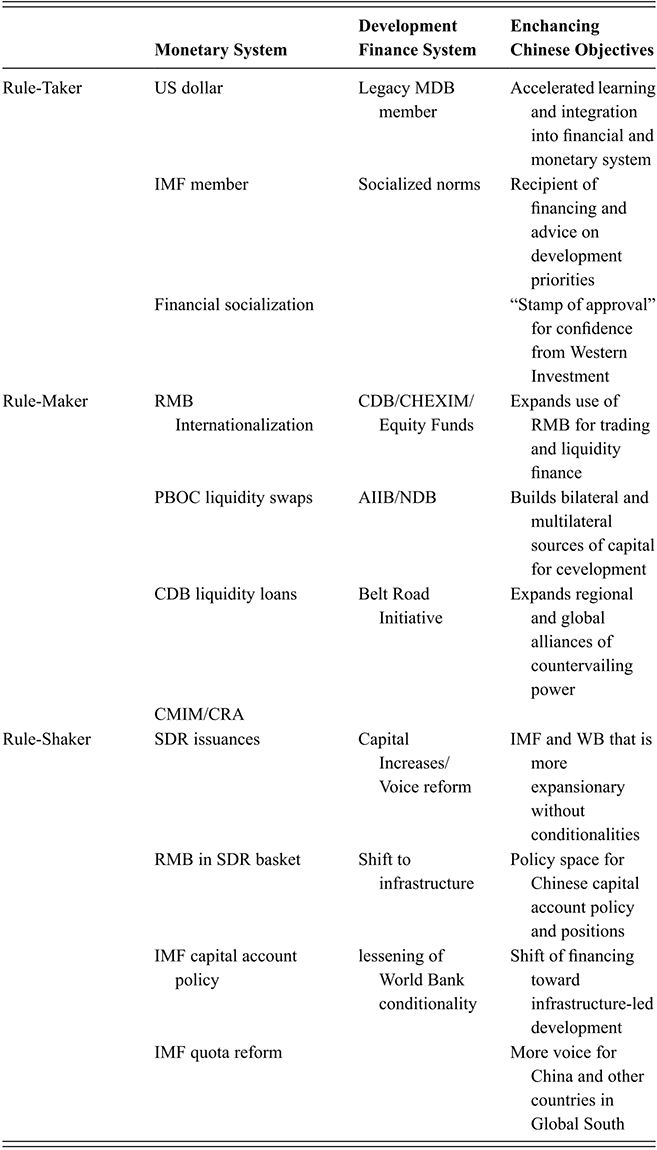

Table 2 China’s countervailing power in the Bretton Woods System

| Monetary System | Development Finance System | |

|---|---|---|

| Rule-Taker | US dollar | Legacy MDB member |

| IMF member | Socialized norms | |

| Financial socialization | ||

| Rule-Maker | RMB Internationalization | CDB/CHEXIM/Equity Funds |

| PBOC liquidity swaps | AIIB/NDB | |

| CDB liquidity loans | Belt Road Initiative | |

| CMIM/CRA | ||

| Rule-Shaker | SDR issuances | Capital Increases/Voice reform |

| RMB in SDR basket | Shift to infrastructure | |

| IMF capital account policy | World Bank conditionality | |

| IMF quota reform |

China’s Growing Monetary and Financial Power

The size and reach of China’s economy, its absorption of the established norms, rules, and standards of the BWIs, and its role in supporting the creation of parallel institutions have given China a unique position as a rule-taker, rule-maker, and rule-shaker in the international monetary and financial systems.

Earlier research on the role of China in the BWIs concluded that China was “playing our game,” as a “rule-taker” that largely accepted the rules of the BWIs. More recent scholarship has come to see China as a partial rule-taker and burgeoning reshaper of existing rules, or what we call a rule-shaker inside the BWIs. Some of the latest literature has examined how China is starting to work outside the BWIs to create new institutions, new rules, and norms. When it comes to the consequences for the international system or world order, the consensus in these studies is that China is still largely a status quo actor, “taking” and “reshaping” the existing rules within the BWIs.

We also argue that this hybrid stance – one foot in, one foot out – does grant China more voice within the BWIs and inside the existing international monetary and financial systems. However, we differ from the aforementioned studies in three respects. First, we see China’s growing contributions inside the BWIs, and China’s creation of new institutions and new rules outside of the BWIs, as giving China “two-way countervailing power.” In conceptualizing “countervailing monetary and financial power,” we draw on John Kenneth Galbraith’s (Reference Galbraith1952) term “countervailing power,” and the scholarship in International Political Economy that has long established that the industrialized countries hold great economic power and leverage access to their large economies to exert power over other countries (Hirschman, Reference Hirschman1945; Strange, Reference Strange1976, Reference Strange1987, Reference Strange1988; Cohen, Reference Cohen1998, Reference Cohen2007; Andrews, Reference Andrews2006; Drezner, Reference Drezner2007b). Galbraith’s study focused on the post-war US economy, which he showed was not functioning well because of a concentration of economic power in large industrial companies. Galbraith examined how workers and input providers could form coalitions to collectively bargain and pressure the state to create regulations to introduce more market competition and make markets more efficient. Drawing on Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1970), Gallagher (Reference Gallagher2015) adapted Galbraith’s concept to analyze the international monetary realm, showing how the BRICS countries exercised countervailing monetary power at the IMF to shift IMF policy on capital controls by forming new institutions outside the IMF, threatening to “exit” in terms of extra-forum leverage, and forming coalitions with key staff and other countries inside the IMF. In this Element, we expand the concept of “countervailing monetary and financial power” to examine China’s behavior in both the international monetary and global development finance realms. We find that China is leveraging its domestic capabilities and international institutions in two directions simultaneously: as a rule-taker and rule-shaker within the BWIs, and as a rule-maker outside of the BWIs (see Table 2).

Second, China’s hybrid positioning paves the way for China (and other countries) to exit the BW system, if or when it sees the need to. Due to China’s increased capabilities within its own institutions and its own financial resources, China has increased its contributions to the World Bank, and it no longer “needs” the services of the BWIs as it did in the 1980s and 1990s. As we discuss later in this volume, China has never taken a balance of payments loan from the IMF. The combination of these factors, and the largesse and relative success that China has achieved in creating alternative institutions, has triggered the West to think that China could exit or push to rival the BWIs. Depending on how other influential members of the BWIs react to China’s institutional reform efforts, inside or outside the BWIs, whether they welcome or resist them, will affect whether China and other developing countries choose to continue working within the BWIs or outside. The decision and outcomes are not preordained.

Third, we see China leveraging its influence and power to advance globally transformative changes in the direction of a less-US-centered, more diffuse, globally-diverse, negotiated, multi-centered global economic order. These trends and patterns with regard to China’s taking, making, and shaking of the rules and norms are examined in more detail in the next two sections. Finally, we discuss what could happen if China continues to push ahead with its hybrid positioning. Is the West likely to continue to engage China to increase its stakeholdership in the BWIs, or treat China more as a threat? As this Element goes to press in 2025, Western governments are pushing back against China’s global rise, hybrid positioning, and countervailing power, and have shifted to compete with China on the global terrain, in relations with the Global South, within the BWIs, and at the UN. We will address which outcome is more likely and what it means for China, the Global South, and the West.

2 How China Remakes the Global Monetary System

Since assuming the seat of “China” inside the IMF, the PRC has largely embraced the US dollar as the de facto global currency and the US dollar payments system, and has behaved as an active member in the Fund. For the last forty years, Beijing has played along as a rule-taker in the IMF, and Chinese officials have established a “professional relationship” with the Fund as a member in “good standing” by learning the rules and significantly increasing China’s contributions to the IMF.Footnote 2 As an IMF member, and even while being a rule-taker, Beijing’s main domestic objectives have been to pursue needed national economic reforms, maintain a sufficient degree of policy autonomy on national economic policy, and ensure economic stability inside China. However, over time, China has increasingly pushed for changes inside the IMF and for altering rules and norms in the global monetary system more broadly, which are relevant for other nations, both developing and developed.

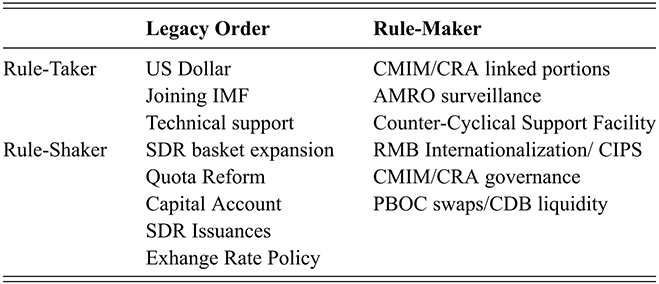

For forty years, China has internalized the core rules of the IMF, such as the terms of borrowing and repayment, requirements on surveillance and national economic information provision, membership contributions and quota-based voting shares, as well as adhering to some extent to the Fund’s policy norms, such as on exchange rates and current and capital account opening (see Table 3). Moreover, China has largely operated in accordance with the combination of rules and norms for the dollar-centered international monetary and reserve system. But on the policies and regulations that Beijing has deemed essential for ensuring the stable management of the national economy, China has protected its policy space to determine the exact exchange rate regime, capital account regulations, monetary, macroeconomic and fiscal policies, and reserve management and foreign currency crisis-insulation strategies.

Table 3 China and the Re-making of Global Monetary Affairs

| Legacy Order | Rule-Maker | |

|---|---|---|

| Rule-Taker | US Dollar | CMIM/CRA linked portions |

| Joining IMF | AMRO surveillance | |

| Technical support | Counter-Cyclical Support Facility | |

| Rule-Shaker | SDR basket expansion | RMB Internationalization/ CIPS |

| Quota Reform | CMIM/CRA governance | |

| Capital Account | PBOC swaps/CDB liquidity | |

| SDR Issuances | ||

| Exhange Rate Policy |

What makes China’s role particularly impactful, however, is that China has also taken actions as an IMF member, acting beyond its national context to affect changes that are of direct relevance to developing country members in the IMF more broadly. Working inside the IMF, China has long advocated for increases in its voice and that of developing countries within the IMF. China has advocated for quota increases for itself and other developing countries as an IMF member, as well as for policy and operational changes in the Fund, such as less onerous conditionality in response to crises.

But China has also worked outside of the IMF to create new institutions, new rules, and establish alternative norms, including new lines of emergency financing outside of the IMF (see Table 3). As a new rule-maker outside of the Fund, China was a co-lead creator and member of the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization (CMIM) and the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) – two new emergency liquidity funds for its member countries. Moreover, China has amassed a large, historically unprecedented foreign exchange reserve, which it uses for self-insurance. China has also allocated a substantial amount of these reserves to provide new liquidity through bilateral arrangements with other developing countries outside of the BWIs. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC), stocked with more than US$3 trillion and other reserves, has become a liquidity supplier to other countries through a significant number of bilateral renminbi-based currency agreements and swap arrangements. More recently, the CDB has also been providing emergency liquidity and budget support for countries in debt distress across the Global South. With these new China-backed bilateral and multilateral institutional arrangements (see Table 3), which operate in parallel to the IMF and play similar functions, China has advanced new or modified rules and established alternative norms that are different from those of the IMF.

After increasing its contributions within the IMF and having created new institutions outside of the Fund, with new rules and alternative norms, China has also looked back into the IMF and leveraged its growing influence both inside and outside of the IMF to shake-up the rules or reshape the rules and the established norms within the Fund. In a growing number of instances since the late 1990s, China, as a “rule-shaker,” has used such two-way leverage to lead in pushing for changes in the rules and norms within the IMF in issue-areas such as quota and voice reforms, exchange rate management, reserve management, and emergency and non-crisis liquidity provision. Working inside and outside of the IMF, China’s hybrid behavior is producing outcomes that are gradually transformative in the realm and global system of international currencies. China has embraced the international use of the US dollar as a rule-taker, but it has also supported an increased role for the euro and the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) as international money and reserve currencies, calling for increased use of SDRs as emergency liquidity for developing countries in ways that have been resisted by the United States. Beijing has also advocated for an increased global role for its national currency, the renminbi (RMB), as a medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value, including for official reserve management purposes. China has done so by pushing for the RMB’s inclusion in the IMF’s SDR reserve basket.

This section first details how China has acted as a rule-taker in the IMF and the existing international monetary system. It then examines how China has been a new rule-maker, creating alternative institutions that operate according to new rules and norms outside the IMF. Finally, it focuses on China as a rule-shaker back within the IMF, as the driver of fundamental modifications of existing rules and norms inside the Fund. The cumulative effect is that China and its partners have opened the door for exploring alternatives inside the IMF and exist options outside (see Table 3). The path that China will choose in the future – inside or outside the IMF – or whether it can maintain the hybrid positioning, is not preordained. Much will depend on the degree of modification that will be accepted or tolerated by the Western powers inside the IMF. But we turn first to the details of China as a rule-taker, new rule-maker, and rule-shaker in relation to the IMF.

China as Rule-Taker

China’s integration into the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and its embrace of the US dollar after the late 1970s were significant changes for China and for the established Bretton Woods order. By entering the dollar order, the PRC was able to engage in international trade and absorb foreign direct investment to a much greater extent than during the Maoist period (1949–1976). From the 1980s onward, China built capital markets that were increasingly integrated into the global financial system. Integration into the established international monetary and reserve system combined rule-taking and norm-taking behavior for China. IMF membership enabled China to learn the rules, standards, and norms of the dollar order.

From the early 1980s to the mid-1990s, China largely behaved as a rule-taker within the IMF, adhering to the many rules and standards of the Fund. In joining the IMF, the PRC gained the benefits of Fund membership, but membership required it to also agree to obligations such as sharing data and information with the members of the Fund, subjecting itself to multilateral rules and scrutiny, and delegating a degree of its national economic sovereignty to the multilateral institution (Jacobson and Oksenberg, Reference Jacobson and Oksenberg1990).

In the 1980s and 1990s, China underwent rapid and dramatic national economic reforms, development, and modernization. International Relations scholars have argued that China’s “socialization” to the international rules, its absorbing and internalizing of the lessons and policy norms of the IMF, and some degree of internal transformation characterized the nature of China’s relations with the global institutions (Pearson Reference Pearson, Johnston and Ross1999; Johnson, Reference Johnson2008). However, it is important to observe that China’s “socialization” to IMF rules and norms did not occur in a static institutional context, as the IMF itself (and World Bank) were themselves undergoing profound changes from the early 1970s onward, toward “neoliberalism” and the “Washington Consensus.”

The foundational academic study of China’s entry and participation in the IMF (and the World Bank and the GATT) from 1945 to the decade of the 1980s, by Jacobson and Oksenberg (Reference Jacobson and Oksenberg1990), details the PRC’s original goals when it acceded to the IMF:

1. Learn the technical requirements for managing a modern, market-oriented financial system that meets international standards.

2. Gain information about other countries and their economies.

3. Reconnect with foreign economic institutions through IMF programs.

4. Expulsion of the Taipei regime from the IMF and its further marginalization in the international community.

5. Demonstrate that the PRC is a “friendly member of the international community.”

The most straight-forward examples of China’s internalization of IMF rules and norms pertained to the obligations of IMF membership spelled out in the “Articles of Agreement.” The Articles required China to take on five dimensions of rules. First, the PRC had to ratify its membership and pay its quota to the Fund. When the PRC entered the IMF in 1980, the PRC assumed the ninth-largest quota, the largest of any developing country. Subsequently, in September 1980, the Fund authorized a special increase in the PRC’s quota from SDR 550 million to SDR 1.2 billion, and then increased it further to SDR 1.8 billion in November 1980, and again to SDR 2.39 billion in 1983 (Jacobson and Oksenberg, Reference Jacobson and Oksenberg1990, 32, 121). As China made these membership payments and became a major shareholder of the Fund’s financial resources, it took a collective interest as a prudent co-manager of the finances.

A second form of China’s IMF rule-taking relates to borrowing from the Fund. China had to learn the evolving policy norms of the Fund and internalize the rules in order to minimize the effects of the IMF’s policy conditionality, which is attached to the Fund’s loans. The PRC absorbed the IMF’s rules on the upper limit of borrowing from its allotted reserve tranche to avoid triggering a challenge from the Fund and the related need to justify the loan request based on the balance of payment needs of the borrower.Footnote 3 The IMF’s conditionality is controversial because it requires the borrower to implement domestic policy changes, such as loosening exchange rates, cutting public sector employment, government subsidies, and public spending. China has avoided the IMF’s conditionality. The PRC has only borrowed twice from the Fund, in the early and mid-1980s, and it has not done so since. In spring 1981, at a time when China was struggling with its post-Mao economic reforms, including balance of payments, Beijing drew from the IMF for its first credit tranche of SDR 450 million and a Trust Fund loan of SDR 309 million, for a total of SDR 759 million from the Fund’s General Reserve Account (Jacobson and Oksenberg, Reference Jacobson and Oksenberg1990, 122).Footnote 4 In May 1983, the government swiftly repaid the first credit tranche, and made good in full in 1984.Footnote 5 In November 1986, China borrowed SDR 600 million for purchases and a SDR 30 million loan (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2000; IMF, 2021a; IMF, 2021b), repaying both in full and early.

Other IMF rule-taking that China was obligated to fulfill under the Fund’s Articles included the publication of IMF materials in Chinese and their dissemination inside China to the relevant stakeholders. To meet the Article IV requirements, China had to hold bilateral discussions with the IMF, typically every year, when an IMF staff team visits the country, collects economic and financial information, and gives recommendations to the officials on the country’s economic policies. China must provide a range of national economic and financial information related to its fiscal and macroeconomic situation and exchange rate policy to the IMF’s Article IV team. Under Article VIII (Section v), related to the Fund’s oversight of its members’ exchange rate policy, China is required to collect and publish economic statistics according to the IMF’s standards, and the Fund engages in exchange rate policy surveillance and provides its assessment.

Related to its annual consultations, surveillance, and advisory roles, the Fund has also provided considerable technical assistance and technical training to China in the areas of the Fund’s competence. Since 1980, experts have traveled to China to conduct training sessions, and large numbers of younger Chinese officials have attended seminars and courses organized by the IMF in Washington, DC. The IMF Bureau of Statistics taught PBOC officials the concept of “balance of payments” and helped them improve their methodology for compiling balance of payments statistics according to IMF standards, as well as the central bank’s related accounting practices (Jacobson and Oksenberg, Reference Jacobson and Oksenberg1990, 122). After “taking” the IMF procedures, PBOC officials returned to China, and compiled their balance of payments statistics using the IMF standards, though they kept the data secret (neibu, or internal) in 1982, 1983 and 1984. In 1985, the PBOC modified its behaviour and published the balance of payments statistics in the public domain for the first time, according to IMF norms. In due course, IMF staff continued to work closely with Chinese officials to improve their monetary supply data and external debt statistics.

Exchange rate policy is another area in which China adhered to IMF rules and norms, at least during the first-two decades. From the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, and as advised by the IMF, China undertook rounds of adjustment for the RMB exchange rate regime. In the mid-1980s, China devalued the RMB by 15.8 percent to address its balance of payments problems during that period (Lardy, Reference Lardy1992). In 1996, China made the RMB freely convertible under the current account in order to comply with IMF Article VIII (PBOC 1996; IMF, 1996). China also undertook a series of policy and institutional reforms in its domestic financial sector, specifically central banking reforms and changes to corporate governance and financial legislation, as advised by the IMF, as part of the country’s “economic modernization” (Lardy, Reference Lardy1998, Reference Lardy, Economy and Oksenberg1999; Kent, Reference Kent2007).

For the first-two decades, and to some extent into the next two, through the IMF borrowing schemes, technical and policy assistance dialogs, and training programs, Chinese officials absorbed and internalized the policy and technical advice, procedures and methods, governance standards, and “best practices” of the IMF (Wang, Reference Wang2018). Jacobson and Oksenberg accurately described China’s record of participation at the IMF (and World Bank) in the initial period of membership as an “orderly process,” where both the IMF and China demonstrated a “methodical, cautious approach to building a relationship” (121, 127).

China as Rule-Maker

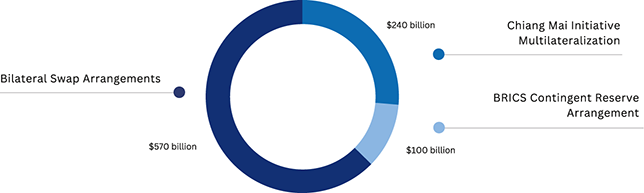

The 1997–98 Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) was a turning point for China’s relations with the BWIs. At IMF meetings in the 1980s through the mid-1990s, China called on members to increase the use of SDR but did not take concrete action to push for expanded use of SDR. Nor did China push to alter the institutional landscape at the system level, particularly the dominant role of the IMF in the multilateral governance of global liquidity and financial safety nets. However, this changed in the aftermath of the 1997–98 Asian Financial Crisis (AFC). Working outside the IMF, China has helped to build several bilateral and multilateral arrangements that mimic the lender-of-last-resort function of the IMF, albeit with different rules and norms (Figure 1).

Figure 1 China’s contribution to the Global Financial Safety Net (2023)

China’s financial and central banking officials – along with their counterparts in other East Asian nations – watched how the IMF and the US responded to the AFC and drew lessons, deciding to self-insure in order to avoid having to borrow from the IMF (Chin, Reference Chin2010, Reference Chin2012). China and East Asian governments self-insulated by building up large stores of foreign exchange reserves, which they could draw on unilaterally without needing approval – and they could use the reserves to help others. China and Japan have led the way among non-US nations in accumulating the largest US dollar reserves in the world.

On the multilateral front, China’s approach to the global financial safety net (GFSN) shifted from focusing on appealing to the IMF for additional financing for the South to promoting the SDR as an alternative supply of global liquidity and as a reserve option. Outside the IMF, China, Japan, and the ASEAN+3 nations allocated resources and diplomatic attention to building a regional financial safety net in East Asia: the Chiang Mai Initiative (CMI), which was later further expanded with more money and more functions, and renamed as the “Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization” (CMIM). In October 1998, amid the ongoing AFC, China’s central bank governor Dai Xianglong stood up at the joint annual discussions (IMF and World Bank) and stated China’s view that the

main cause of the crisis [AFC] is that international cooperation and the evolution of the international financial system lag far behind the economic globalization and financial integration process, and the speed of their liberalization exceeded the pace of enhancing the economic management abilities of the crisis-hit countries … Speculators with huge sums of capital are able to take large leveraged positions to control and manipulate markets for profit, accentuating market volatility … the international community has [still] not come to a consensus on effective mechanisms for the monitoring and containment of risks brought about by volatile capital flows.

Dai then offered: “It is our firm belief that by strengthening coordination and mutual support within the Asian region, the economic and financial development in Asia is bound to stabilize gradually” (IMF, 1998).

The agreement to create the CMI was announced in May 2000 at the ASEAN+3 finance ministers’ meeting. China, together with Japan, was the co-initiator of the CMI. In December 1998, at the second informal meeting of ASEAN+3 in Vietnam, China’s then Vice President Hu Jintao proposed that ASEAN+3 finance and central bank deputies meet to discuss further regional cooperation, and they did so in April 1999. In November 1999, at the third informal meeting of ASEAN+3 Leaders in Manila, China’s Premier Zhu Rongji suggested that the bloc should discuss how to institutionalize their regional economic and financial cooperation. In December 1999, the finance ministers agreed to establish “self-help and support mechanisms in East Asia.”

The CMI originally consisted of 15 bilateral swap agreements, totaling the equivalent of US$37.5 billion, including a US$1 billion ASEAN Swap. “Equivalent” because, although the majority of the CMI financing was in US dollars, Beijing struck a unique agreement with the CMI partners that the bilateral swap lines with China and other CMI partners be denominated in RMB. Despite the fact that East Asian countries have independently funded and managed the CMI, the expanded CMIM can still be conceptualized as having links to the IMF, in that the ASEAN+3 grouping decided to tie a portion of any future disbursement of the Chiang Mai funds to IMF approval (initially set at 90 percent of the borrowing quota requiring IMF approval and subject to IMF conditionality).

However, the intention of ASEAN+3 from the outset of the CMI discussions was to increase the operational autonomy of the CMI, away from the IMF, over time. In the two decades since CMI’s creation, ASEAN+3 has gradually increased the portion of CMI(M) swaps that can be allocated without IMF approval (Grimes and Kring, Reference Grimes and Kring2020). In May 2005, ASEAN+3 agreed to integrate economic surveillance procedures into the CMI framework and, importantly for increasing operational autonomy beyond the IMF, agreed to create an ASEAN+3 economic monitoring and advisory office called the “ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office” (AMRO). Relatedly, ASEAN+3 agreed to increase the size of swaps that could be withdrawn without an IMF-supported program from the original 10 percent to 20 percent (ASEAN+3, 2005). ASEAN+3 finance ministers further agreed to significantly increase the size of the swaps in the CMI, and by 2007, the size of the CMI swap pool had doubled to US$64 billion and 16 swap agreements.

After the 2008–09 GFC, China and the ASEAN+3 further boosted the CMI into CMIM, increasing the size of the regional swap fund from US$90 billion to US$120 billion. Importantly, the grouping moved ahead on “multilateralizing” the bilateral swap agreements into a “single [regionalized pool] contractual agreement.” CMIM took effect in March 2010 (AMRO, 2023). CMIM’s core objectives are (1) to address balance of payment and/or short-term liquidity difficulties in the ASEAN+3 region; and (2) to supplement existing international financial arrangements. China’s contribution (including Hong Kong) to the CMIM increased to US$38.4 billion. For some comparative perspective, the size of the CMIM at US$120 billion was relatively small compared to the national reserves of the Asian countries (US$5 trillion) and paled in comparison to the amounts deployed by G20 national governments and the ECB in response to the GFC – China’s domestic stimulus package alone was the equivalent of US$586 billion. Nonetheless, the increase in the size of the East Asian regional safety net required striking a new diplomatic consensus between China and Japan, as the two largest “co-contributors,” Korea (US$19.2 billion), and the ASEAN nations with a combined US$24 billion (Chin, Reference Chin2012).

The ASEAN+3 opened the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO) as a regional office for the CMIM in April 2011 in Singapore. The creation of this office was especially significant, as it signaled the ability to delegate surveillance and loan design, that is, new rule-making, to a self-governed body – a prerequisite for ending the CMIM’s subordination to the IMF (Grimes and Kring, Reference Grimes and Kring2020). To kick-start the rule-making, the ASEAN+3 finance ministers decided on the new basic rules for activating the swap agreements and the new rules for joint decision-making on their use (as a “first step toward multilateralization”), and delegated it to AMRO to work on the details and bring the proposals back to the ASEAN+3 finance ministers for decision-making.

One of the most noteworthy new rules of the CMIM relates to the activation and delivery of CMIM swaps, which makes the first draw on the CMIM immediate, rapid, targeted, and easy to access for the borrower, with more extensive justification required for a second draw. The technical reason for this approach is that crisis financing must be provided rapidly to help avert or contain a financial crisis. However, AMRO staff also gave “Asian”-specific cultural reasons for how the ASEAN+3 members of CMIM approach the broader issue of the stigma that becomes attached to the borrower that draws on emergency crisis liquidity in an actual crisis scenario: that rapid and easy access to crisis liquidity, and fast delivery of the first draw, can help to reduce the reputational stigma that is attached to borrowers of IMF-type loans and allow for national “face-saving,” which is said to be especially important in East Asian cultures.Footnote 6 As no ASEAN+3 member has drawn on the CMIM to date, there is yet to be a concrete case study of the delivery of this emergency fund. Nonetheless, the intention to devise rules that are informed by IMF rules and norms, but are more responsive to “Asian cultural characteristics,” can be observed.

In 2014, the ASEAN Plus Three decided to further increase the size of the CMIM by doubling it to $240 billion and also to increase the CMIM-IMF De-Linked Portion to 30 percent, as well as to extend the maturity and supporting period (AMRO, 2023) The ASEAN+3 also expanded the purpose of the regional safety net by introducing the “CMIM Precautionary Line,” a new crisis prevention facility, adding to the existing “CMIM Stability Facility,” aimed at crisis resolution. In March 2021, members also amended the CMIM Agreement to increase the IMF De-Linked Portion from 30 percent to 40 percent. Importantly, they also agreed to use their own local currencies for CMIM financing, in addition to the US dollar (see Figure 1). China and the other ASEAN+3 members have further indicated that they intend to completely de-link the disbursement of CMIM funds from IMF approval (Grimes and Kring, Reference Grimes and Kring2020). The ASEAN+3 members are now discussing how to further expand their financial cooperation under the CMIM umbrella, which would mean new purposes, more new rules, and norms.

The CMIM has, in turn, inspired the BRICS nations to create their own US$100 billion Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) as a similar emergency liquidity pool for the BRICS governments (see Figure 1). The former Brazilian Executive Director at the IMF and former Vice President of the NDB, Paulo Nogueira Batista Jr., writes that the CMI was the model that BRICS governments drew on to create their own liquidity safety net (Batista Jr., Reference Batista2021, 13–32). Batista Jr. visited the AMRO in Singapore in 2014 to learn about the CMIM first-hand, where he, Brazilian finance officials, and China’s central bank and finance officials relayed the lessons to the BRICS group.

The CRA was officially launched in 2015, with China, by far the largest committed contributor, allocating US$41 billion, while Brazil, India, and Russia agreed to each commit US$18 billion, and South Africa US$5 billion.Footnote 7 The BRICS governments set the amount that each country can draw from the CRA fund and the associated voting share for each member. Of particular note, China made a financial contribution that far outweighs its agreed access amount: after giving US$41 billion, China agreed to only draw up to US$21 billion if needed. This rule is underpinned by a new norm of international leadership that China is advancing of “giving more, taking less”; the PRC’s take on global leadership as sacrificing for the greater good and being generous in providing global public goods (Chin and Stubbs, Reference Chin and Richard2011). With its sizable national foreign reserves, Beijing does not need the CRA for insurance. The BRICS Plus members are now discussing adding more member-states to the CRA and expanding the size of the fund, and some researchers are discussing expanding the financial uses for the CRA beyond emergency crisis liquidity to non-crisis use, which means creating new rules and new norms among the CRA members.

In the informal realm of global governance, China has also played a role in creating alternative rules and norms to the IMF in response to the 2008–09 Great Financial Crisis. China acted as a new rule-maker, outside of the IMF, when it pushed for a portion of the US$1.1 trillion agreed upon by G20 country leaders for emergency economic fire-fighting to be allocated to regional institutions to deliver, rather than to the IMF (Chin, Reference Chin2010, Reference Chin2012). When the GFC erupted, leaders of the BRICS nations, especially Indian PM Singh and Brazilian President Lula emphasized that the GFC was not caused by developing countries, and that developing countries should not have to pay the price. Indonesia, China, India, South Korea, and Brazil pushed G20 leaders to support the creation of new lines of rapid, flexible counter-cyclical lines of emergency financing for developing and low-income countries but to be dispersed by regional development banks, not the IMF (Chin, Reference Chin2012).

China supported an Indonesian proposal to the G20 to allocate a portion of the new money promised to the IMF (at the April 2009 London G20 Summit) to the Asian Development Bank (ADB) instead. This financing would be flexible, fast-disbursing, and utilize front-loaded instruments that provide rapid assistance to developing countries in the Asian region that were considered “well-governed,” but nonetheless faced potential balance of payments crises due to the GFC.Footnote 8 With the backing of the G20, the ADB quickly created a new countercyclical instrument – the Countercyclical Support Facility – to provide budget support of up to US$3 billion for crisis-affected countries in Asia (ADB, 2009). However, the new “rule” for Asia had a broader global impact, as regional development banks in other regions of the world, such as the IDB and the AfDB, quickly followed the ADB’s example. They also drew on a portion of the new funds committed at the London G20 and established new regional-level facilities to provide rapid and more flexible counter-cyclical lines of credit to countries in their regions. These regional mechanisms prevented further contagion and helped to contain spillovers across the regions.

China has also initiated other new elements of the global financial safety net at the bilateral level (see Figure 1). When several of China’s trading partners experienced a liquidity crunch and a crisis of trade finance in 2008 and 2009 because of the global liquidity freeze, a number of these governments turned to Beijing for help, and to the PBOC specifically for emergency liquidity support. Like the US Federal Reserve, which offered emergency US dollar swap lines to US trading partners in periods of economic and financial uncertainty, the PBOC agreed to several bilateral currency agreements, denominated in RMB, including bilateral swap agreements (BSAs). However, the PBOC currency agreements are different from the US dollar swaps of the US Federal Reserve in that the RMB can be used for a wider range of purposes, such as “non-emergency” trade financing.

RMB-denominated BSAs were first signed with South Korea in 2008, and then with Argentina, Belarus, Hong Kong, Indonesia, and Malaysia in 2009. These countries were all confronting looming balance of payments crises amid the GFC, and the BSAs helped them avoid a full-on crisis. For these countries, settling their cross-border payments with business partners in China using RMB or their own national currency meant that an equivalent number of US dollars was freed-up to be used elsewhere.Footnote 9 In 2011, the PBOC signed more BSAs with other countries that were also facing balance of payments challenges due to the residual effects of the GFC, including Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Pakistan, and Thailand.Footnote 10 In 2010, the PBOC signed a BSA with Singapore to support the city-state’s desire to join Hong Kong as an offshore RMB transaction hub. Britain signed a bilateral currency swap agreement with the PBOC in June 2013 for similar reasons. In October 2013, the ECB also signed a bilateral RMB-Euro currency swap agreement as a liquidity backstop.

Starting in 2013, some of these governments drew on their PBOC swap lines, beginning with Pakistan, which reportedly used the RMB equivalent of US$600 million from its RMB 10 billion (US$1.5 billion) swap line with the PBOC and exchanged the RMB for US dollars. Facing a sharp decrease in its foreign exchange reserves, the State Bank of Pakistan did so to shore up its reserves, boost market confidence in the Pakistani economy, and gain approval for a US$6.65 billion IMF loan in June 2013 (Rana, Reference Rana2013). In 2015, Argentina was the next government to use its PBOC BSA for external liquidity when it was blocked from capital markets after defaulting on its sovereign debt. The PBOC allowed the Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA) to draw the RMB equivalent of US$2.7 billion from its RMB 70 billion (US$11 billion) swap line. Argentina used some of the RMB to pay for imports from China, which allowed the BCRA to keep its dollar reserves for other purposes and exchange some of the RMB into US dollars (Reuters, 2014; Devereaux, Reference Devereaux2015). Also in 2015, when Mongolia’s raw material exports waned, foreign investment fell, and foreign exchange reserves ran low, Mongolia drew the RMB equivalent of US$1.7 billion from its US$2.5 billion swap line with China. A senior economist at the Central Bank of Mongolia noted that the BSA was “one of the tools to absorb the shock of the balance of payments pressures” (Edwards, Reference Edwards2015).

Russia’s central bank accessed its BSA with the PBOC on various occasions from October 2015 to March 2016, after Western sanctions and falling oil prices put downward pressure on the ruble from 2014 onward (Xinhua, 2016). The amount of Russian drawings was not reported publicly, and China’s Xinhua News Agency only noted that the money was allocated to several Russian and Chinese counterparties to support bilateral trade and direct investment between the two nations (CBR, 2016). Ukraine also drew on its BSA with China in 2016, when Kyiv’s foreign exchange reserves fell below the IMF-mandated reserve target, and it gained approval from the PBOC to activate the swap with China (IMF, 2016, 7; McDowell, Reference McDowell2019, 136).

These examples show when, where, how, and why China’s swap agreements have served as lender-of-last-resort mechanisms outside the IMF for five countries that chose to activate a portion of their RMB swap lines for short-term needs: Argentina, Mongolia, Pakistan, Russia, and Ukraine. The Ukraine case was an example of linking a PBOC BSA to maintaining an IMF loan. There are other cases where a BSA from China was key for the partner country to secure an IMF loan, namely Pakistan and Mongolia. In November 2016, China also signed a BSA with Egypt, which opened the door for Cairo to secure an IMF credit line of US$12 billion. The IMF required Egypt to secure US$6 billion in bilateral liquidity before approving Egypt’s IMF program (IMF 2017; Reuters, 2016).

These swap lines continued through the COVID-19 pandemic period and the subsequent shocks, and an increasing number of countries also drew on those lines. China’s swaps and its other new lines of financing, particularly from China’s state policy banks, such as the China Development Bank, have become important sources of crisis-related liquidity as an alternative to the IMF (Sundquist, Reference Sundquist2021). Kaplan (Reference Kaplan2021) finds that China’s liquidity loans have given Latin American countries more room to maneuver recover, and avoid borrowing from the IMF. In 2008, after Ecuador was shut out of private capital markets, China provided a liquidity loan to help Ecuador return to the private capital markets more quickly than if it had undergone austerity measures from the IMF (Gallagher, 2016). By the end of 2023, the PBOC had over $400 billion in active currency swaps, with several developing countries benefiting from this liquidity finance, including Pakistan, Egypt, and Indonesia. Interestingly, in 2023, a swap agreement with the PBOC allowed Argentina to draw $2.7 billion to bridge its IMF program (Zucker Marques and Kring, Reference Zucker Marques and Kring2023). In 2024, Egypt also benefited from crisis-related financing from China, which helped secure Egypt’s US$8 billion IMF loan.

Working outside the IMF, China and its partners are advancing new rules and policy norms that serve as an alternative to the IMF, whether it is in the small- and medium-sized developing countries using bilateral currency agreements for emergency liquidity or trade financing, or with the CMIM and the BRICS CRA. China is acting as a new rule-maker and, in some cases, offering its own national currency, the RMB, rather than US dollars, along with the new rules. The country has also been adding new tiers and institutions to the GFSN, which creates the potential for China and partner countries to work outside of the IMF and the dollar, and according to a new set of rules and norms for lender-of-last-resort or nonemergency financing.

China as Rule-Shaker

China’s efforts at building alternative institutional arrangements, rules, and norms outside of the IMF have fed-back into the IMF. In some instances, the transmission back inside was intentional on the part of China’s officials. In other cases, it was not consciously undertaken by Chinese officials and their Southern partners but occurred rather through the force of example or was transmitted back by IMF staff, other officials, or national delegates inside the BWIs. The key outcome of this rule-shaking pattern is that the feed-back of the alternative rules, norms, and models actually results in changes to the rules and norms back inside the IMF. These changes represent an incremental altering – a shaking – of the established rules, norms, the preferred models, and lessons inside the Fund, in ways that reflect the rule and normative preferences of China and its Southern partners, or the experiences of the China-supported alternative institutions.