Introduction

Understanding local movements and migration across vast landscapes are essential for the identification of factors affecting the survival of migratory species and for the application of effective conservation measures and management strategies (Berger Reference Berger2004, Newton Reference Newton2007). Migration data provide insights into the periodical utilisation of specific areas, timing, stop-over sites, migratory connectivity and migratory behaviour (Berthold et al. Reference Berthold, Gwinner and Sonnenschein2003, Helbig Reference Helbig, Berthold, Gwinner and Sonnenschein2003, Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Bowlin, Bisson, Shamoun- Baranes, Diehl and R2009, Si et al. Reference Si, Xu, Xu, Li, Zhang and Wielstra2018). Furthermore, the use of satellite tracking data has largely improved our understanding of the interactions of birds with anthropogenic activities at different scales (such as agriculture and fisheries), the ecology of diseases like avian influenza and the connectivity between outbreak areas and bird locations (Newton Reference Newton2008, Li et al. Reference Li, Meng, Liu, Yang, Chen and Dai2018). All this information has provided more accurate baseline data for decision-makers about conservation and sustainable management of endangered species (Cooke Reference Cooke2008).

The optimal migration theory includes the time- and energy-minimisation hypotheses (Alerstam and Lindström Reference Alerstam, Lindström and Gwinner1990). The time-minimisation hypothesis assumes that birds should minimise spring migration time (pre-breeding migration) in order to arrive early at their breeding grounds (Hedenström and Alerstam Reference Hedenström and Alerstam1997, Kölzsch et al. Reference Kölzsch, Müskens, Kruckenberg, Glazov, Weinzierl, Nolet and Wikelski2016, Lameris et al. Reference Lameris, Scholten, Bauer, Cobben, Ens and Nolet2017). This would give them some advantages, such as a higher chance of occupying the best nesting sites and benefitting from the early highly nutritious spring bloom, ensuring a better survival for early-hatched chicks (Hedenström and Alerstam Reference Hedenström and Alerstam1997, Ward Reference Ward2005, Lameris et al. Reference Lameris, Scholten, Bauer, Cobben, Ens and Nolet2017). On the contrary, during autumn (post-breeding) migration birds are not driven by such time pressure and can thus reduce their migration speed by increasing the time spent in stop-over sites or making more stops along the flyway (Drent et al. Reference Drent, Both, Green, Madsen and Piersma2003, Nilsson et al. Reference Nilsson, Klaassen and Alerstam2013, Kölzsch et al. Reference Kölzsch, Müskens, Kruckenberg, Glazov, Weinzierl, Nolet and Wikelski2016). This is why post-breeding migration is expected to minimise the total energy cost of migration and migrants are therefore expected to use the energy-minimisation strategy (Hedenström and Alerstam Reference Hedenström and Alerstam1997). Moreover, the arrival of most migrants at wintering and breeding sites is greatly dependent on the selection of favourable stop-over habitats (Si et al. Reference Si, Xu, Xu, Li, Zhang and Wielstra2018, Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Li, Yu and Si2018). The selection of any stop-over site depends on environmental and anthropogenic variables, such as available food supplies, levels of competition and the security of the sites against disturbance and threats such as predation and poaching (Clausen et al. Reference Clausen, Christensen, Gundersen and Madsen2017, Lameris et al. Reference Lameris, Scholten, Bauer, Cobben, Ens and Nolet2017). For instance, migratory birds can skip some stop-over sites because of an increase in predators or avoid stop-over sites near human settlements (Li et al. Reference Li, Meng, Liu, Yang, Chen and Dai2018, Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Li, Yu and Si2018). Previous studies have outlined the negative impact of human settlements on birds’ stop-over and foraging sites via direct disturbance by the farming community (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Wang, Cao, Zhang, Jia and Lee2017, Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Li, Yu and Si2018). In addition, unfavourable weather conditions can force migratory birds to rest, forage, and seek shelter (Hübner et al. Reference Hübner, Tombre, Griffin, Loonen, Shimmings and Jónsdóttir2010). Therefore, understanding migration timing and the identification of stop-over sites during migration is critical to any species conservation plan (Ruth et al. Reference Ruth, Barrow, Sojda, Dawson, Diehl and Manville2005, Shariati-Najafabadi et al. Reference Shariati-Najafabadi, Darvishzadeh, Skidmore, Kölzsch, Exo and Nolet2016).

According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (BirdLife International 2016), 38 species (22%) of waterfowl (ducks, geese, and swans) are globally under some category of threat. Historically, many waterfowl have sustained significant population declines due to both, intrinsic (ecological history) and extrinsic effects (habitat loss and fragmentation, especially through drainage for agriculture, and hunting) (Madsen Reference Madsen1993, Long et al. Reference Long, Székely, Kershaw and O’Connell2007). This might be the case of the Ruddy-headed Goose Chloephaga rubidiceps, which is the smallest of the five South American sheldgeese. This species has two separate populations: one sedentary, which resides in the Malvinas/Falkland Islands and one migratory population (the mainland South American population) that overwinters mainly in Southern Buenos Aires province (Pampas region, Central Argentina) and breeds in Southern Patagonia (Argentina and Chile). Recently, new findings postulated that these two populations are genetically isolated as they do not share mtDNA haplotypes (Bulgarella et al. Reference Bulgarella, Kopuchian, Di Giacomo, Matus, Blank, Wilson and McCracken2014) and have dissimilarities based on their nuclear DNA (Kopuchian et al. Reference Kopuchian, Campagna, Di Giacomo, Wilson, Bulgarella and Petracci2016). However the latest IUCN Red List considered this species as ‘Least Concern’ (BirdLife International 2016). This is due to the fact that the Ruddy-headed Goose is still considered by IUCN to have a large global population which is estimated to range between 43,000 and 82,000 individuals (Woods and Woods Reference Woods and Woods2006, BirdLife International 2016), taking into account the two separate populations. While the Malvinas/Falklands population appears to be of ‘Least Concern’ (Woods and Woods Reference Woods and Woods2006, BirdLife International 2016), the population on mainland South America has decreased considerably and recent estimates indicate that the population size is less than 800 individuals, around 10% of the estimated population in the 1900s (Cossa et al. Reference Cossa, Fasola, Roesler and Reboreda2017, Pedrana et al. Reference Pedrana, Bernad, Bernardos, Seco Pon, Isacch and Muñóz2018a). As a result, this population has been categorised as critically endangered in Argentina (AA/AOP and SAyDS 2017), and endangered in Chile (CONAMA 2009), and was declared a ‘Natural Monument’ in Buenos Aires and Santa Cruz provinces (Argentina). The decrease in the continental Ruddy-headed Goose population has mainly been attributed to increased predation by invasive predators, degradation of breeding areas due to livestock, and illegal hunting (Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Blank, Benegas, Mateazzi, De Blanco and Matus2003, Blanco and de la Balze 2006, Pedrana et al. Reference Pedrana, Bernad, Maceira and Isacch2014, Cossa et al. Reference Cossa, Fasola, Roesler and Reboreda2017). Furthermore, the decline in the continental population is also related to habitat change and degradation at stop-over sites along migration flyways, although these factors remained unresearched (Pedrana et al. Reference Pedrana, Seco Pon, Isacch, Leiss, Rojas and Castresana2015, Reference Pedrana, Seco Pon, Pütz, Bernad, Gorosabel and Muñoz2018b).

The aim of this study is to provide the first documentation of the complete migration cycle of the Ruddy-headed Goose by using solar satellite transmitters. In order to analyse their annual migration in detail, including the identification of stop-over sites along their flyway, breeding and wintering grounds, adults of this species were tracked from their wintering grounds in the Pampas region, Argentina, to their breeding sites in Southern Patagonia. The information provided by satellite tracking was used for the comparison of migration timing during spring and autumn migration. We urge that better knowledge and understanding of how Ruddy-headed Geese migrate through the landscape, provided by tracking the movements of individual birds, will help to improve the conservation efforts directed at this species and will contribute to the modification of the current status of ‘Least Concern’ under the IUCN criteria.

Methods

Study area and Ruddy-headed Goose tracking data

The mainland population of Ruddy-headed Goose overwinters in the Southern Pampas located in the south-east of Buenos Aires province, Argentina (between 36° and 41°S and 63° and 58°W). The climate is sub-humid mesothermal with a mean annual temperature of 10–20°C and a mean annual rainfall between 400 and 1,600 mm (Soriano Reference Soriano and Coupland1991). Currently, most of the original grasslands have been replaced by pastures and croplands, with a specific expansion of soybean croplands, since the 1970s (Baldi and Paruelo Reference Baldi and Paruelo2008).

In the wintering areas, Ruddy-headed Goose is generally associated with Upland Goose C. picta and Ashy-headed Goose C. poliocephala (Carboneras Reference Carboneras, Del Hoyo, Elliott and Sargatal1992). These species were historically considered harmful to agriculture and declared ‘agricultural pests’ by the Argentinian government in 1931 (Pergolani de Costa Reference Pergolani de Costa1955). All three species leave the Pampas region in August–September when they start their migration. There are two potential migration routes (Plotnick Reference Plotnick1961, Summers and McAdam Reference Summers and McAdam1993). One of them runs across eastern Patagonia along the Atlantic coast, and the second one is located more to the west, along the foothills of the Andes. However, recent studies show that the Upland Goose migrates via the Atlantic coast (Pedrana et al. Reference Pedrana, Seco Pon, Isacch, Leiss, Rojas and Castresana2015, Reference Pedrana, Seco Pon, Pütz, Bernad, Gorosabel and Muñoz2018b).

Six Ruddy-headed Geese were captured in their wintering area in the southern Pampas (38°33’S; 59°42’W) using foot-noose carpets. Geese were equipped with solar satellite transmitters (Solar PTTs, Model 23GS, 23-28 g solar PTT, North Star ST LLC, USA) which were attached to the birds’ back using a Teflon harness (Humphrey and Avery Reference Humphrey and Avery2014) (Table 1). Total mass of instruments including harness deployed on each bird was 33g, representing less than 3% of the individual’s body mass, thus minimising the effects of carrying an additional weight during movements (Casper Reference Casper2009). Blood samples were taken to assess the gender of the captured birds using DNA since this species does not display strong sexual dimorphism (Narosky and Yzurieta Reference Narosky and Yzurieta2010). The samples were taken by pricking a vein in the wing and absorbing a small droplet of blood onto a commercial filter paper (Quintana et al. Reference Quintana, López and Somoza2008). Individuals were also weighed using a digital balance (precision 0.10 g; Table 1). Birds were released as soon as possible after marking, typically within 30 minutes, back at their capture locations. Procedures for capture and handling were approved by the Buenos Aires Provincial Agency for Sustainable Development (OPDS), Argentina (N° 2145-2872/15).

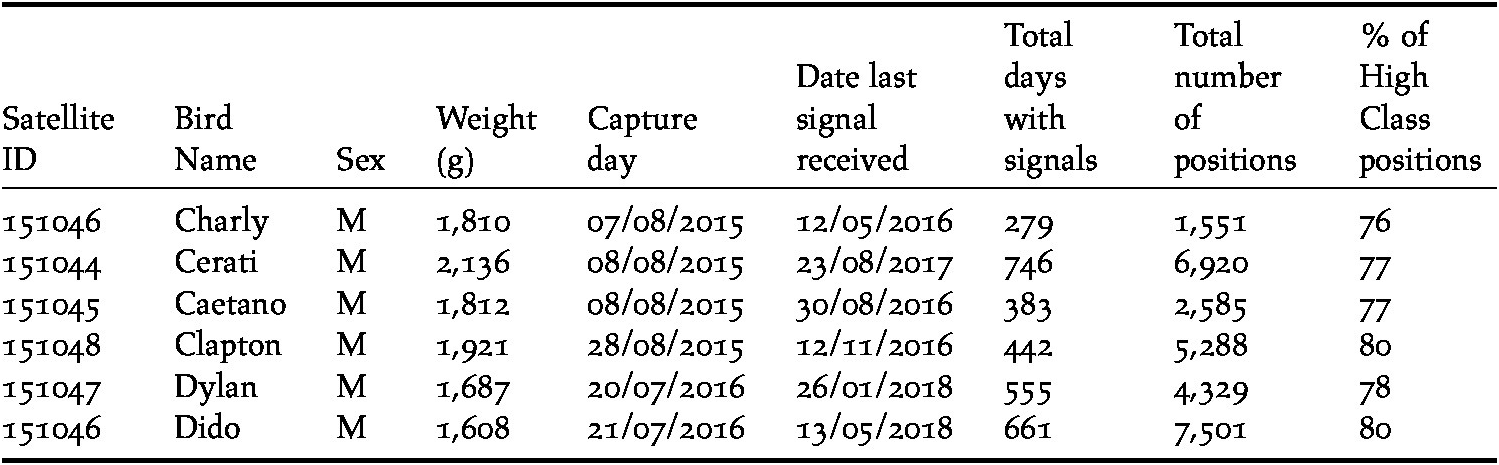

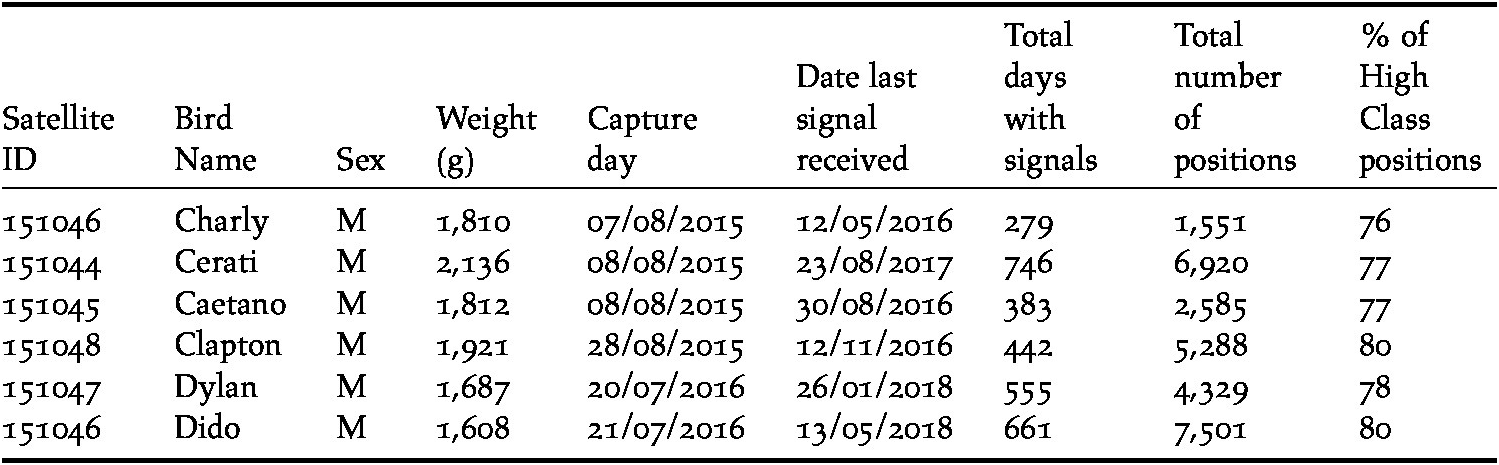

Table 1. Morphological data for Ruddy-headed Geese Chloephaga rubidiceps fitted with satellite transmitters and a summary of the performance of the transmitters.

Satellite tags were programmed to transmit with a duty cycle of 6h on/18h off (local time, GMT-3). Geographical locations were provided by the Argos service, with location accuracy (class designation) calculated using the Kalman filtering method (ARGOS Reference ARGOS2016). We only used Argos locations with accuracy classes 0, 1, 2 and 3 (i.e. high class positions; accuracy ≤ 1,000 m) for further analysis which accounted for most (≥ 75%) fixes while the other locations with less accurate location classes (A, B, Z) were not considered (i.e. lower class positions). Positional data were then incorporated into a Geographical Information System and the minimum distance between positions was calculated based on the assumption that the bird travelled in a straight line between two consecutive positions (Table 1).

Delineation of stop-over, breeding and wintering sites

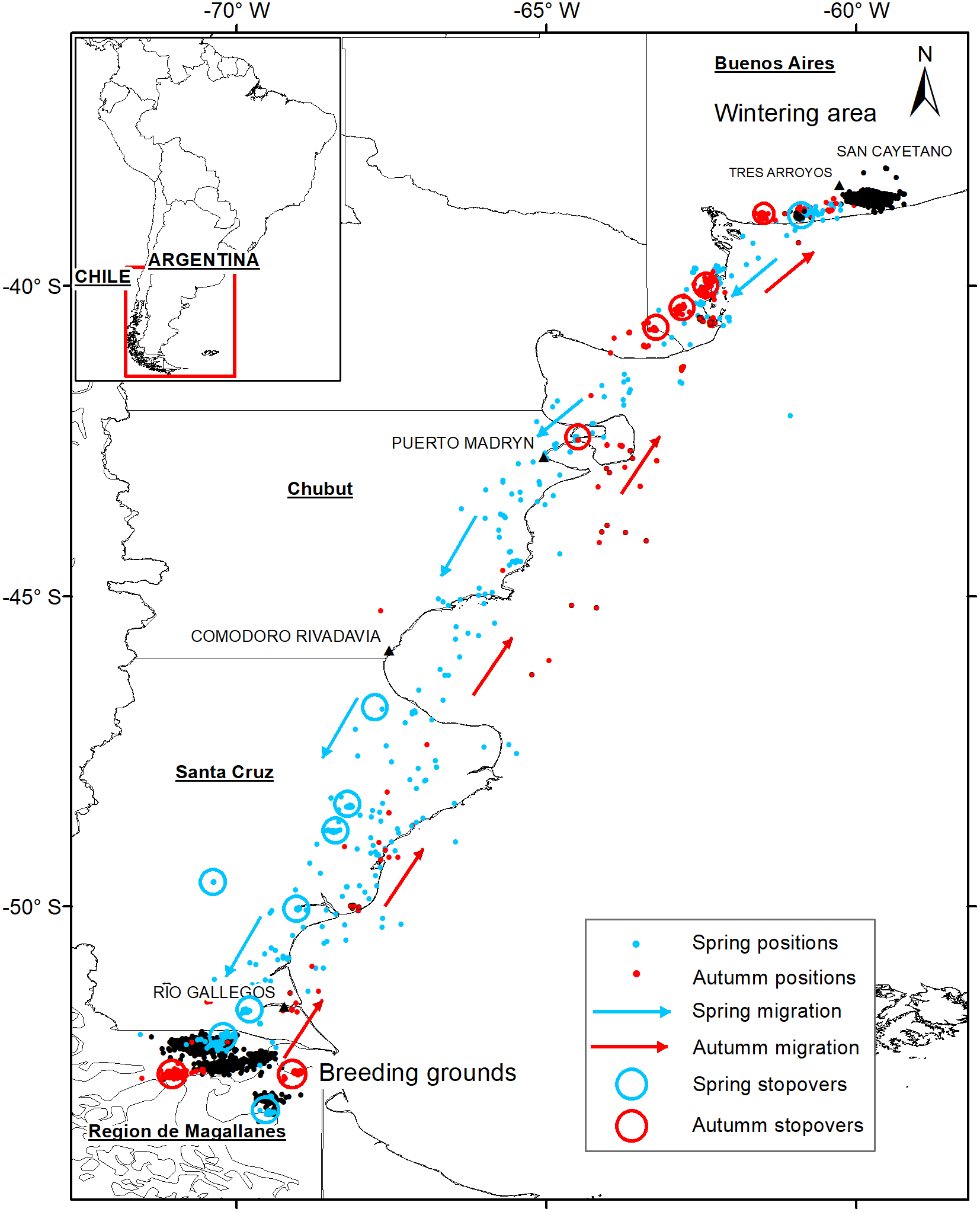

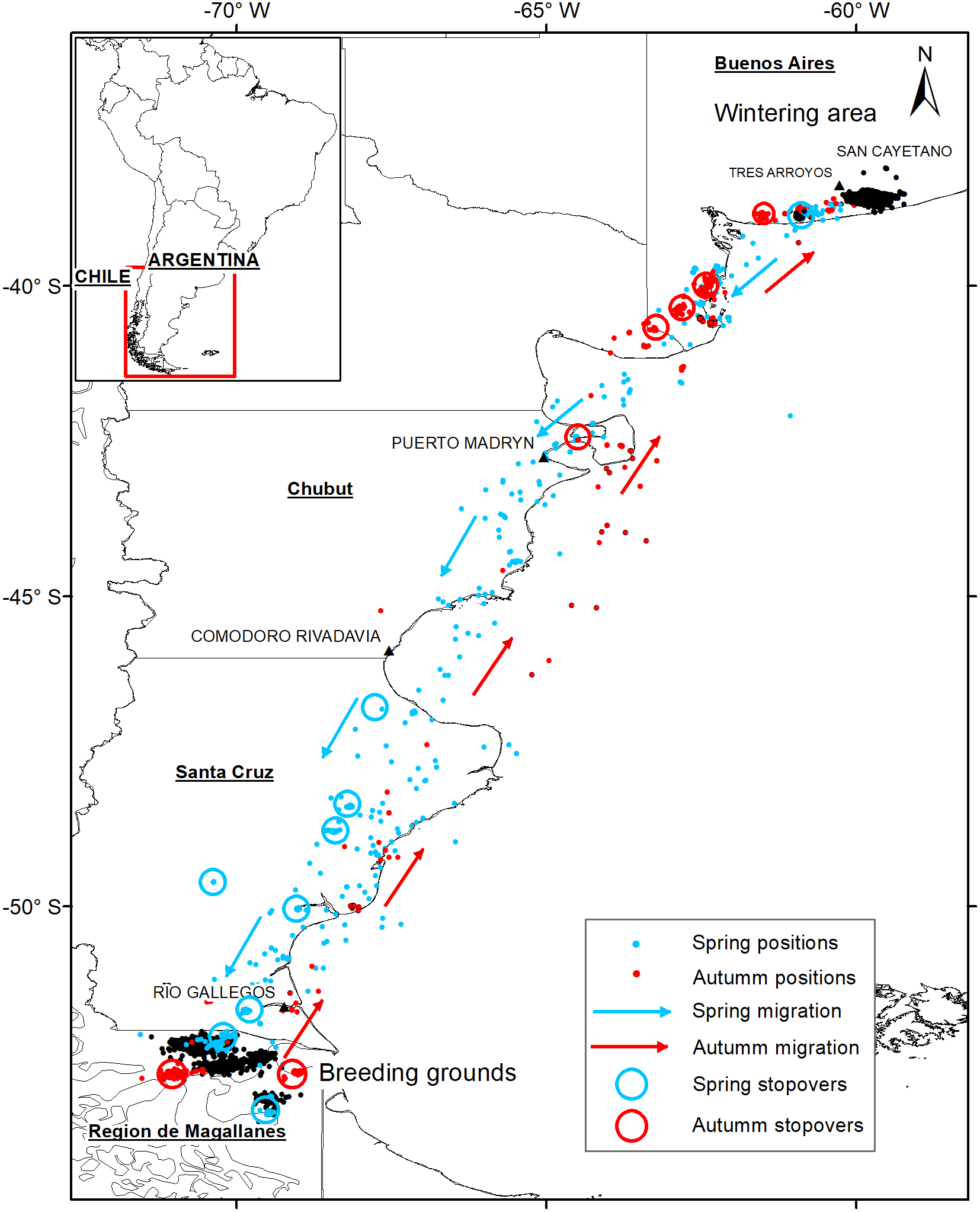

We defined wintering grounds as places used by Ruddy-headed Goose from May to August inside the south-east of Buenos Aires province boundaries (Tres Arroyos and San Cayetano districts; Figure 1). The breeding grounds were considered as sites used by the species from end of August to May in Patagonia (Figure 1). For the spring (southbound) migration, we considered all positions between the last positions in the wintering grounds until arrival at the breeding grounds. For the autumn (northbound) migration, we considered tracks from the last position obtained in their breeding ground until arrival in the wintering area. Individual stop-over sites, where birds rest, refuel or await better weather conditions (Hübner et al. Reference Hübner, Tombre, Griffin, Loonen, Shimmings and Jónsdóttir2010), were characterised by assemblages of subsequent positions with a displacement of less than 30 km for at least 48 h (van Wijk et al. 2012).

Figure 1. Migration pathways of Ruddy-headed Geese tracked in 2015–2018. Grey (blue) indicates spring migration and black (red) autumn migration. Circles show stop-overs during spring migration and autumn migration. Black points in Buenos Aires province indicate wintering grounds and black points in Patagonia specified breeding grounds.

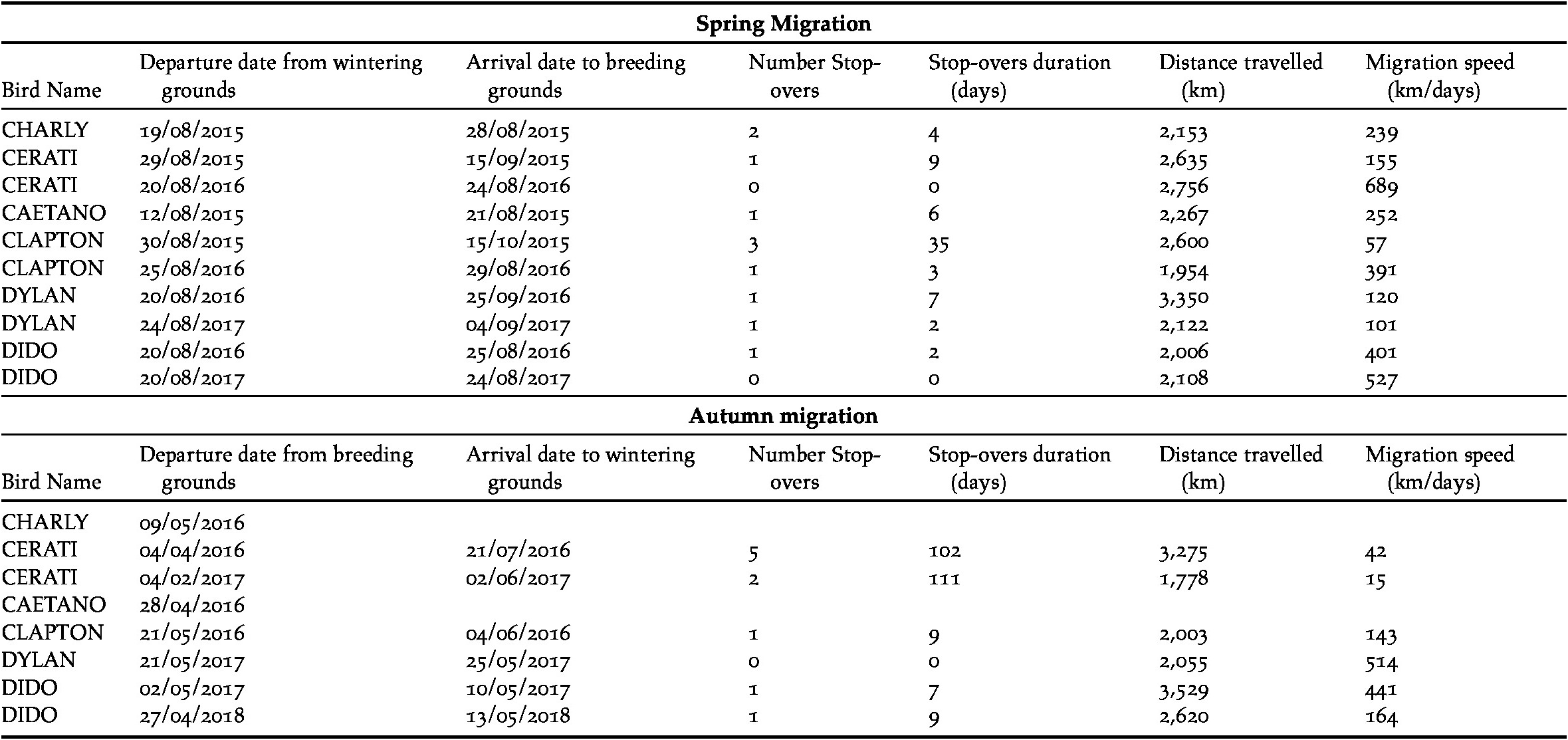

For each migration track, we determined the beginning of the spring/autumn migration, arrival at breeding/wintering site, number and duration of stop-overs (number of days spent in the stop-overs), distance travelled and migration speed. Total duration of migration was calculated as the time (days) spent travelling between the breeding and wintering sites (autumn migration) and vice-versa (spring migration), including the time spent in stop-over sites. This differs from the general definition of migration duration, which would also include the time of fuelling for migration at the breeding/moulting or last wintering site, respectively (Kölzsch et al. Reference Kölzsch, Müskens, Kruckenberg, Glazov, Weinzierl, Nolet and Wikelski2016). Migration speed was estimated as the total migration distance divided by the duration (in days) of the entire migration.

We compared spring and autumn migration first by simple measures as number and duration of stop-overs, distance travelled and overall migration speed. We used Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) to analyse the influence of season on the different response variables measured in this study. We analysed the number of stop-overs and stop-over duration using GLMM with a Poisson error structure and negative binomial, respectively. In the second case, we chose this in order to decrease the dispersion parameter. In all models, we tested the fixed-effect of the migration, which is a two-level categorical variable (spring and autumn), and to include possible differences that we did not measure between individuals, we set the identity of each individual and the year as a random effects. We evaluated all possible models and we compared competitive ones using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). All the analyses were done in R studio (R Development Core Team Reference Team2017) using package ‘lme4’. All the results are presented as mean ± standard error.

Results

All Ruddy-headed Geese captured were males (Table 1) and wintered near Tres Arroyos city in the south-eastern corner of Buenos Aires province (Figure 1). In addition, all of them returned to the same areas where they were captured one year before. Tracked birds left their wintering sites between 12 and 30 August and migrated 2,395 km (± 131), on a wide front, to their distant breeding grounds in the Patagonian region (Table 2). All birds performed spring migration mainly over land (Figure 1). Tracked geese arrived at their breeding grounds less than two weeks after departing their wintering grounds (14 ± 5 days) and remained in southern Patagonia during summer for at least seven months (225 ± 30 days). All presumed breeding grounds recorded in this study were located in southern Chile, mainly in the Magallanes region and were revisited by the birds in subsequent years.

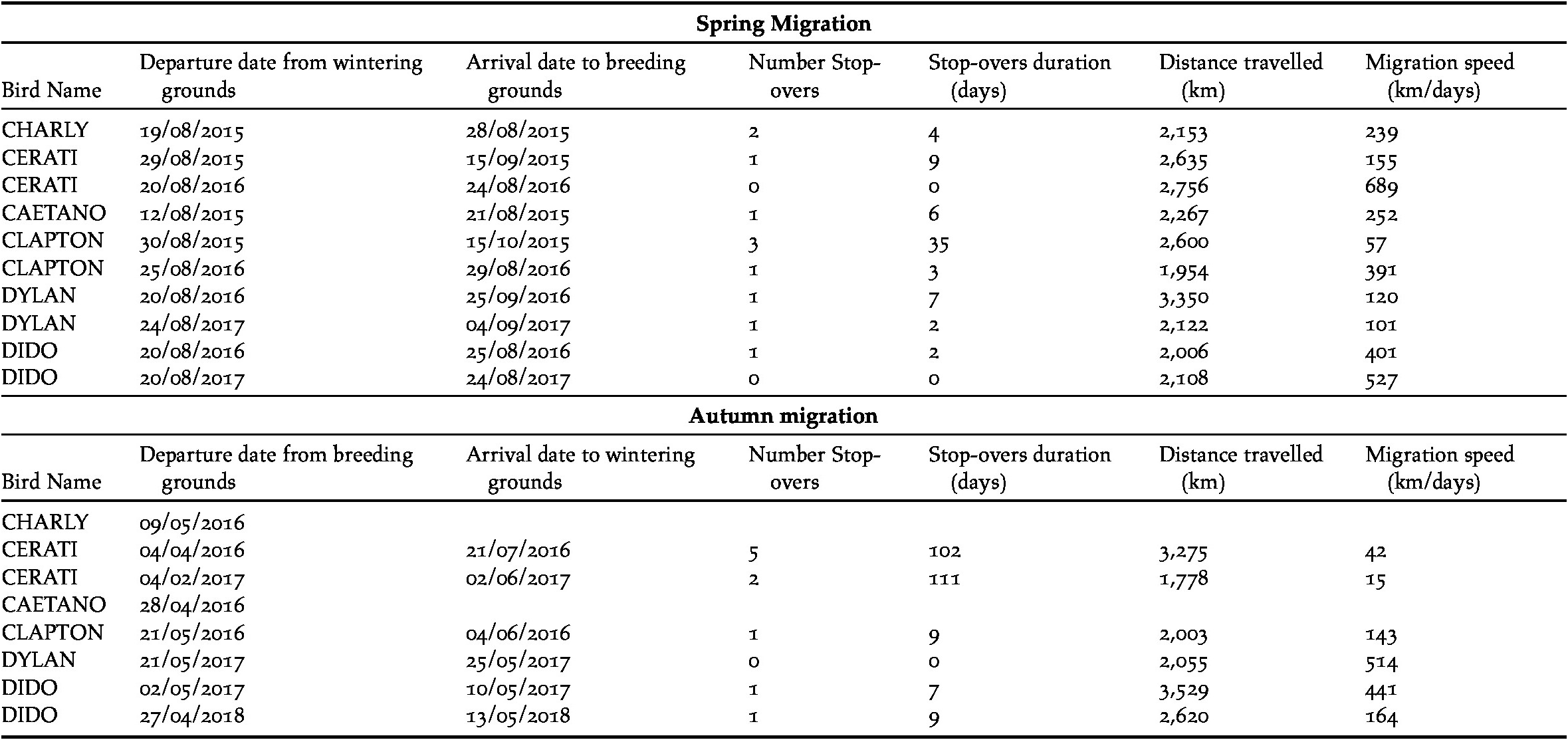

Table 2. Summary of migration phenology for all tracked Ruddy-headed Geese.

Birds migrated during austral autumn between 27 May and 21 June (Table 2). The distance travelled from their breeding sites to their wintering grounds was 2,353 km (± 314) (Table 2). Geese moved along the Atlantic coastline and took more than one month (39 ± 19 days) to arrive to their wintering grounds. The autumn migration was directed over the sea or close to the coastline (Figure 1). We lost the signal of two of our tracked geese before they started their autumn migration.

Stop-overs and migration routes

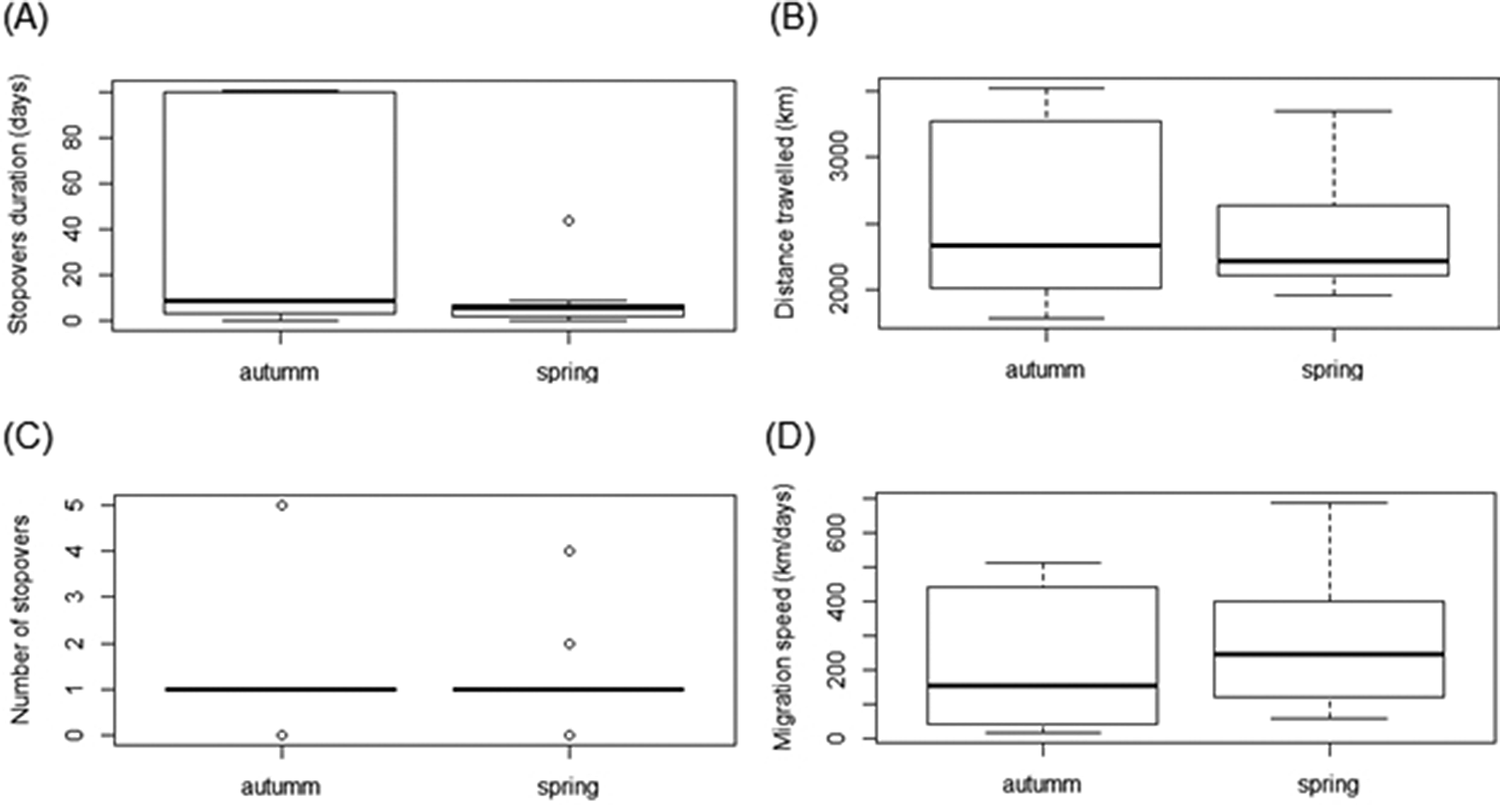

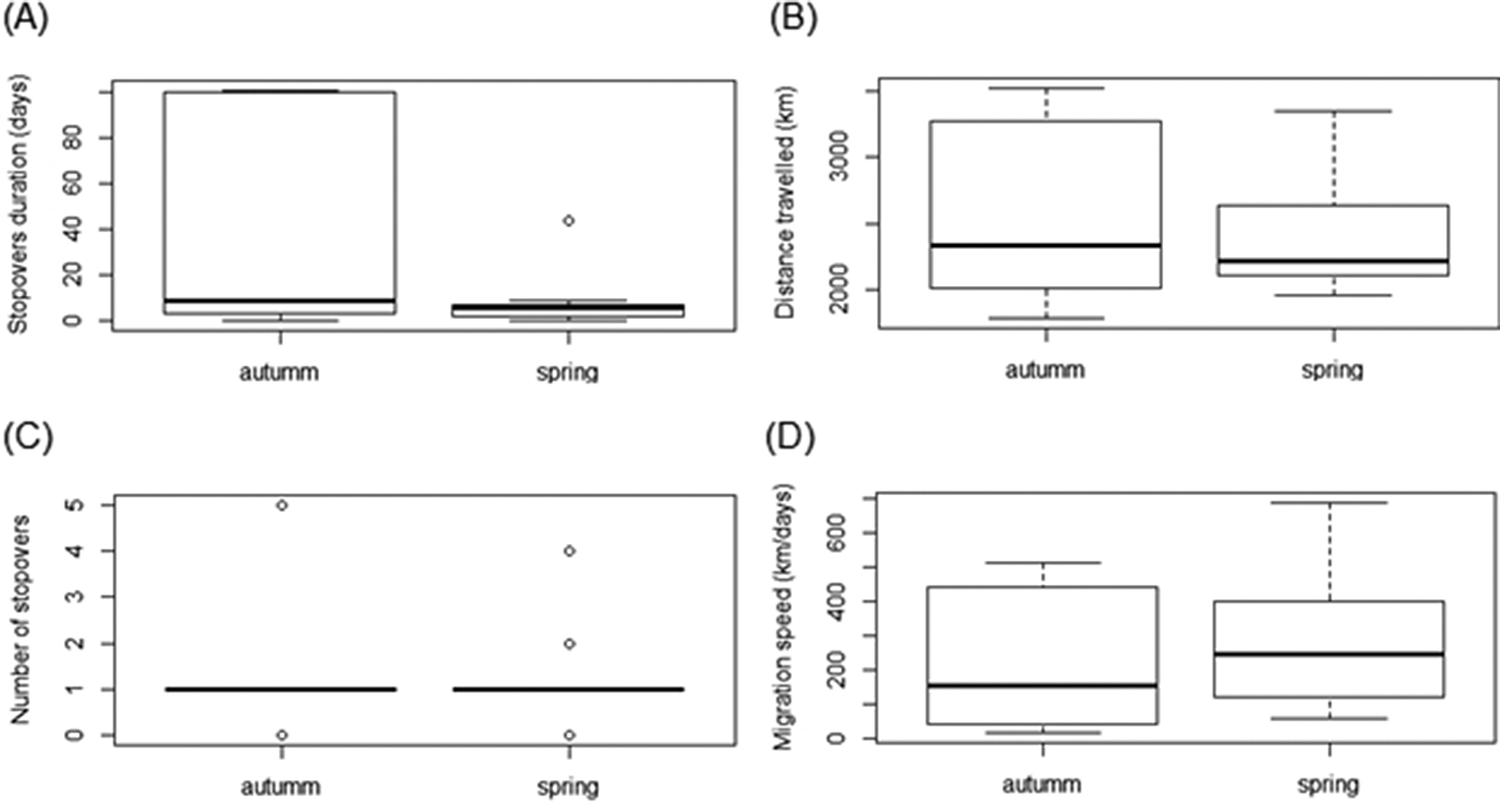

Stop-over duration, which is the most widely used measure to compare spring and autumn migration, was significantly different in our two data sets (β = -1.49 ± 0.72, P < 0.01, Table 2, Figure 2a). Geese spent more days in the stop-over sites in the autumn than in the spring migration (on average, spring migration: 6.8 ± 3.3 days; autumn migration: 32.3 ± 17.7 days). The autumn migration lasted, on average, 39 days, while spring migration was significantly shorter, lasting 14 days (Table 2). Nevertheless, the mean distances travelled during both migration periods were similar (2,395 km in spring versus 2,300 km in autumn, β = -270.27 ± 305.9, P = 0.4, Figure 2b). The number of stop-overs between seasons (β = -0.43 ± 0.61, P = 0.48, Figure 2c) and the overall migration speed (β = 62.84 ± 109.8, P = 0.6, Figure 2d) did not differ significantly. In general, stop-overs of tracked birds were situated close to their final destination. Thus, stop-overs during spring migration were mainly located in southern Patagonia while stop-overs during autumn migration were situated in southern Buenos Aires province (Figure 1). Birds did not necessarily use the same stop-overs during subsequent migrations.

Figure 2. Boxplots of (a) stop-over duration, (b) distances travelled, (c) number of stop-overs, (d) overall migration speed between autumn and spring migration of Ruddy-headed Geese, tracked between 2015 and 2018.

Discussion

This study presents the first migratory flyway of the Ruddy-headed Goose in mainland South America based on satellite tracking data. Previous studies, based on banded individuals and questionnaires (Lucero Reference Lucero1992, Rumboll et al. Reference Rumboll, Capllonch, Lobo and Punta2005), postulated two potential migration routes for the continental geese populations, including the Ruddy-headed Goose (Plotnick Reference Plotnick1961, Summers and McAdam Reference Summers and McAdam1993). One of them runs across eastern Patagonia along the Atlantic coast, and the second is located more to the west along the foothills of the Andes. Our data on Ruddy-headed Geese migration suggest that only the route along the Atlantic coast was used. Moreover, previous satellite tracking studies on Upland Geese performed concomitantly to this study recorded the same eastern migration route (Pedrana et al. Reference Pedrana, Seco Pon, Isacch, Leiss, Rojas and Castresana2015, Reference Pedrana, Seco Pon, Pütz, Bernad, Gorosabel and Muñoz2018b). Similarly to Pedrana et al. (Reference Pedrana, Seco Pon, Pütz, Bernad, Gorosabel and Muñoz2018b), our tracked birds took the route along the Atlantic coast, although further west overland, during the spring migration. On the contrary, our results indicate that autumn migration took place offshore. Despite these subtle differences, the use of the (eastern) migration route by the Ruddy-headed Goose, as revealed by our datasets, along with other Chloephaga species (Pedrana et al. Reference Pedrana, Seco Pon, Isacch, Leiss, Rojas and Castresana2015, Reference Pedrana, Seco Pon, Pütz, Bernad, Gorosabel and Muñoz2018b), could be partially related to the gregarious behaviour shown by the species. They comprised mixed flocks during spring and autumn migrations (Pedrana et al. Reference Pedrana, Seco Pon, Pütz, Bernad, Gorosabel and Muñoz2018b). Other explanations could be related to exogenous factors such as weather, particularly winds and topography (Alerstam and Hedenström Reference Alerstam and Hedenström1998, Farmer and Wiens Farmer Reference Farmer and Wiens Farmer1998) which influenced the migratory behaviour of birds. Mixed-species flocks may serve to decrease an individual’s risk of predation (Myers Reference Myers1983, Krause and Ruxton Reference Krause and Ruxton2002, Zoratto et al. Reference Zoratto, Santucci and Alleva2009) and many goose species, including Chloephaga, have been traditionally recorded comprising mixed flocks (Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Zalba, Belenguer, Pugnali and Rodríguez Goñi2003, Blanco and de la Balze Reference Blanco, de la Balze, Boere, Galbraith and Stroud2006). On the other hand, it is documented that mountains and high plateaus such as the Andean mountains might act to shape connectivity between breeding and wintering grounds among migratory birds (Alerstam and Hedenström Reference Alerstam and Hedenström1998, González-Prieto et al. Reference González-Prieto, Bayly, Colorado and Hobson2016). This may be due to the strong, constant west winds which are characterised not only by their persistence during the year but also by their intensity (Oesterheld et al. Reference Oesterheld, Aguiar and Paruelo1998, Paruelo et al. Reference Paruelo, Beltran, Jobbagy, Sala and Golluscio1998). Hence, we hypothesise that the use of the eastern migration route by geese is affected by a combination of the flocking behaviour of several Chloephaga species and the prevailing weather conditions. Further research is needed to elucidate the effect of such stressors on the migration strategy of the Ruddy-headed Goose.

Our results also reinforce the statement that spring migration in most avian migrants is faster than autumn migration (Ward Reference Ward2005, Kölzsch et al. Reference Kölzsch, Müskens, Kruckenberg, Glazov, Weinzierl, Nolet and Wikelski2016). Autumn migration towards the wintering areas of tracked Ruddy-headed Geese lasted three times longer than the spring migration. Nonetheless, this difference was only associated with the time spent in the stop-over sites, but not with the distance and speed travelled or the number of stop-overs. Köppen et al. (Reference Köppen, Yakovlev, Barth, Kaatz and Berthold2010) found similar results in Bar-headed Goose Anser indicus and other shorebird species (Nilsson et al. Reference Nilsson, Klaassen and Alerstam2013). There are many possible factors affecting the time spent in stop-over sites, such as food availability, weather conditions, intra- and interspecific competition, predators and sex, age class, and endogenous parameters (Jenni and Schaub Reference Jenni, Schaub, Berthold, Gwinner and Sonnenschein2003, Nilsson et al. Reference Nilsson, Klaassen and Alerstam2013). Spring migration in Ruddy-headed Goose occurs closer to the summer solstice, so days are longer, and birds may have more daylight to forage during spring than during autumn migration. This could provide the birds with more daylight to replenish their energy stores at the stop-over sites, potentially resulting in less time spent in these areas (Nilsson et al. Reference Nilsson, Klaassen and Alerstam2013). It could also be that birds are avoiding intense (westerly) wind speeds in Patagonia, which in this area show a maximum between September and January (Paruelo et al. Reference Paruelo, Beltran, Jobbagy, Sala and Golluscio1998). Several studies show that migrants bear a certain threshold wind factor which indicates to them whether to depart or let several days pass before departing (Weber et al. Reference Weber, Alerstam and Hedenström1998). As the age of the birds was unknown, we cannot consider the influence of individual experience, but it might contribute to foraging efficiency (Heise and Moore Reference Heise and Moore2003, Gall et al. Reference Gall, Hough and Fernández-Juricic2013). At the individual level, for example, subcutaneous fat deposits may influence stop-over duration (Moore and Kerlinger Reference Moore and Kerlinger1987, Woodrey and Moore Reference Woodrey and Moore1997, Gannes Reference Gannes2002, Goymann et al. Reference Goymann, Spina, Ferri and Fusani2010). Therefore, in spite of the small sample size, the mass range of our tracked birds (1,608–2,136 g) might show other sources of variation for stop-over duration. However, due to the lack of associated parameters indicating individual quality and energy stores, the reason for the differences in the time spent at stop-over sites remains purely speculative.

All stop-over sites used by Ruddy-headed Geese were located closer to the final destination (i.e. wintering and breeding grounds; Figure 1), showing that the first part of the migration is much faster than the second part. Similar results were found by Green et al. (Reference Green, Alerstam, Clausen, Drent and Ebbinge2002) in Brent Goose Branta bernicla bernicla. There are various potential reasons for this: the amount and/or quality of stop-over habitat closer to the endpoint might be better than other habitats elsewhere along the migration route; or birds might have adequate stored energy and nutrients, which allow them to stay aloft for longer periods of time (Hutto Reference Hutto1998, Stafford et al. Reference Stafford, Janke, Anteau, Pearse, Fox, Elmberg, Straub, Eichholz and Arzel2014). The first could be true, for example, in stop-overs located on the northbound migration near the Pampas region that is characterised by large areas of crops and pastures dissected by lakes and marshes (Soriano Reference Soriano and Coupland1991). Another explanation could be that until very recently (to 2005) stop-over habitats scattered along the intermediate section of the migration route (i.e. northern Patagonia and Pampas region) were under legal hunting pressure. As previously recorded, some birds seem to adjust their migratory journeys in order to minimise energy consumption and thus to enhance their chances of survival (Vansteelant et al. Reference Vansteelant, Bouten, Klaassen, Koks, Schlaich and Diermen2015, Goymann et al. Reference Goymann, Lupi, Kaiya, Cardinale and Fusani2017, Monti et al. Reference Monti, Grémillet, Sforzi, Dominici, Bagur and Navarro2018). Similarly, for many species, foraging conditions are better in spring than in autumn, which allows shorter stop-overs with higher foraging gain, leading to shorter migration duration (Shamoun-Baranes et al. Reference Shamoun-Baranes, Baharad, Alpert, Berthold, Yom-Tov, Dvir and Leshem2003, Reference Shamoun-Baranes, Bouten and Emiel Van Loon2010, Vansteelant et al. Reference Vansteelant, Bouten, Klaassen, Koks, Schlaich and Diermen2015). Regardless of the use of stop-over areas closer to the final destination, tracked birds were not always faithful to their stop-over sites during subsequent migrations, meaning that these birds might not choose the same stop-overs. It could be that herbivores like the Ruddy-headed Goose rely heavily on the energy and nutrients built up concurrently while breeding and/or wintering, which allows them to reach different areas closer to their destination (Giunchi et al. Reference Giunchi, Baldaccini, Lenzoni, Luschi, Sorrenti, Cerritelli and Vanni2019). Another explanation could be that because suitable stop-over habitats for the birds are under variable intensive cropland management, the selection of stop-over habitat by geese closer to their final destination is directly influenced by such management (Giunchi et al. Reference Giunchi, Baldaccini, Lenzoni, Luschi, Sorrenti, Cerritelli and Vanni2019). Actually, some wildfowl migrating overland are known to follow a stepping-stone strategy, taking advantage of the food they find en route (Viana et al. Reference Viana, Santamar, Michot and Figuerola2013). Several studies revealed that stop-over sites and migration routes are dynamic systems evolving over time (Jonker et al. Reference Jonker, Kraus, Zhang, Hooft, Larsson and van der Jeugd2013, Clausen et al. Reference Clausen, Madsen, Cottaar, Kuijken and Verscheure2018). Hence, it is expected that migration patterns may also vary in response to environmental change (Clausen et al. Reference Clausen, Madsen, Cottaar, Kuijken and Verscheure2018).

Despite the differences in the migration routes taken, some pronounced similarities in the data gathered between southbound and northbound migrations became evident (at least in terms of distance travelled, speed of migration and the number, but not the location, of stop-overs) indicating a strong fidelity of the birds to their annual migration routes. Moreover, our data provided clear evidence that the autumn migration routes of the Ruddy-headed Goose (along with the Upland Goose, see Pedrana et al. Reference Pedrana, Seco Pon, Isacch, Leiss, Rojas and Castresana2015, Reference Pedrana, Seco Pon, Pütz, Bernad, Gorosabel and Muñoz2018b) include areas with high anthropogenic pressure, mainly competition for grazing areas and illegal hunting. Along their northbound migration routes, birds spent one and a half months, most likely replenishing their energy deposits. On the other hand, the identified breeding area of Ruddy-headed Geese is located within the Magallanes region, in southern Chile. They remained in their breeding grounds for at least seven months, indicating that they might be successful breeders. The Magallanes region is the second least populated region of Chile and much of the land is rugged or closed off for sheep farming and is unsuitable for human settlement. Although several sites within this ecosystem have been identified as Important Bird Areas (Devenish et al. Reference Devenish, Díaz Fernandez, Clay, Davidson and Zabala Yépez2009), modern threats to breeding Ruddy-headed Geese include nest predation by the grey fox Pseudalopex griseus and introduced American mink Neovison vison, combined with the disappearance of tall grasses due to overgrazing by sheep and cows (Blanco and de la Balze Reference Blanco, de la Balze, Boere, Galbraith and Stroud2006, Cossa et al. Reference Cossa, Fasola, Roesler and Reboreda2017). In addition, attempts to assess the health status of Ruddy-headed Geese, or further conserve the species in southern Patagonia, is currently restricted to a single emergency rehabilitation station for live poached geese (among other avian groups) located in the Strait of Magellan, Chile, coupled with a restoration programme aimed at rearing geese in captivity (Matus and Blank Reference Matus and Blank2017).

Recommendations for Ruddy-headed Goose conservation

Our results suggest that threats posed to the species during its autumn migration encompass mainly human activities (i.e. competition with croplands for grazing areas and poaching), thus calling for actions to implement management. For instance, one management action could be creation of alternative feeding areas along Ruddy-headed Goose stop-over sites, as previously proposed for other migrants (Fox et al. 2017). These areas could be managed to create disturbance-free zones with palatable food and enhanced spatial characteristics and restore good-quality conditions such as through control of introduced carnivores, maintaining protective vegetation cover and preventing illegal hunting (Cossa et al. Reference Cossa, Fasola, Roesler and Reboreda2017). Cossa et al. (Reference Cossa, Fasola, Roesler and Reboreda2018) produced some management recommendation for the breeding areas that should be also applied especially in the Patagonian stop-overs, for instance, excluding livestock to avoid disturbance.

Since most stop-over sites and breeding or wintering grounds delineated in this study occurred on private land, we believe that management measures should engage local farmers and citizens into Ruddy-headed Goose management. Involving stakeholders in co-management is a way to alleviate conflicts between wildlife and human activities (Tombre et al. Reference Tombre, Eythórsson and Madsen2013, Fox et al. 2017). Moreover, these could promote citizen science to further increase the perceived value and help the conservation of this endangered species. Compensatory payments have been implemented in several European countries (e.g. Norway; Tombre et al. Reference Tombre, Eythórsson and Madsen2013). This could involve provision of special feeding and buffer areas for birds where farmers receive compensation in return (Cope et al. Reference Cope, Vickery, Rowcliffe, Boere, Galbraith and Stroud2006, MacMillan et al. Reference MacMillan, Hanley and Daw2004), effectively protecting geese in their stop-over sites. It could also include restoration and protection of natural habitats.

Further studies should include health status assessment, increasing the number of sampled individuals and also the quality condition of stop-over sites. These measures could provide a better understanding of migration timing and the importance of stop-over sites for Ruddy-headed Geese in mainland South America thereby improving the conservation prospects of the species. It is essential to increase information about the spatial distribution of environmental and human drivers on Ruddy-headed Goose distribution in order to address threats posed to the species along its migration routes and to comprehend the selection of stop-over sites in the future.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nicolás Charadia, Leandro Olmos, Juan Pablo Isacch, Néstor Maceira, Ricardo Matus, Olivia Blank, Daniel Novoa, and Daniel MacLean for their generous help with fieldwork and logistical support. This work was funded by Antarctic Research Trust, INTA (PNNAT-1128053) and National Agency for Science and Technology, Argentina (PICT 2012- 0192). The procedure used in this study was assessed and approved by the Buenos Aires Provincial Agency for Sustainable Development (OPDS), Argentina (Licence Number: 0023352/18).