Introduction

Paternal perinatal depression (PPND) is increasingly recognised as a common condition that can affect fathers and parents but also have an indirect impact on mothers and infants (Thiel et al. Reference Thiel, Pittelkow, Wittchen and Garthus-Niegel2020, Paulson et al. Reference Paulson, Keefe and Leiferman2009). The perinatal period, is defined as the time between conception and up to one year postpartum (Tsai et al. Reference Tsai, Kiss, Nadeem, Sidhom, Owais, Faltyn and Van Lieshout2022) and so includes both antenatal and postnatal periods. The perinatal period is universally considered the most vulnerable time for emergence of psychiatric disturbances in women (Koukopoulus et al. Reference Koukopoulos, Angeletti, De Chiara, Simonetti, Kotzalidis, Janiri, Manfredi and Sani2020). It is now acknowledged that this risk extends to fathers too. However, at time of publication PPND was not included in International Classification of Diseases 11 (ICD-11) or Disease Statistics Manual-5 (DSM-5). During the early postnatal period, fathers face many new stressors arising from their newborn’s needs (Hildingsson and Thomas, Reference Hildingsson and Thomas2014) and relationship changes (Kamalifard et al. Reference Kamalifard, Hasanpoor, Kheiroddin, Panahi and Payan2014). Studies have shown the transition to fatherhood can negatively impact men’s health causing distress, anxiety, and increased risk of depression (Kim & Swain, Reference Kim and Swain2007). Recent systematic reviews have found wide variations in estimated prevalence of PPND from 2.9% to 23.8% (Shafian et al. 2022) and 1.2% to 25.5% (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Li, Qiu and Xiao2021). This wide variation may be attributed to diverse settings, sample size, recruitment strategies, inclusion and exclusion criteria, assessment timepoints, cut-off scores, the use of different measurement tools, and the cultural setting of the study (Philpott et al. Reference Philpott, Leahy-Warren, FitzGerald and Savage2022). A 2017 Irish study found the prevalence of paternal postnatal depression to be 28% (Philpott & Corcoran, 2018). Risk factors for PPND include a history of depression, financial or life stressors, and lack of social support (Edward et al. 2015).

The EPDS was developed by Cox et al. (1987) as a screening tool for postnatal depression. It is now the most commonly used screening tool to assess for PPND (Philpott, Reference Philpott2016). It is comprised of 10 self-report questions, scored from 0–3 giving a score range of 0–30. Higher scores indicate a greater load of depressive symptoms. The majority of studies of maternal depression using the EPDS have used a cut-off score of 12 or greater (Murray & Carothers, Reference Murray and Carothers1990). In general, a lower cut-off point is accepted in screening for PPND, as it is thought that men tend to be less expressive about their feelings (Carlberg et al. 2018). One study found cut-off scores of 7–10 are generally accepted for men (Shafian et al. Reference Shafian, Mohamed, NasutionRaduan and Anne2022). A separate study by Matthey et al. (2001) found a score of > 9 was the optimum cut-off for depression. If the EPDS is to be consistently used to screen for depression in new fathers it is important that a reliable cut-off point is determined and established in different populations (Edmondson et al. 2010).

Goodman (2004) identified the influence social support, relationship satisfaction, and role adjustment can have on developing paternal depression, emphasising the need for increased attention to fathers’ emotional well-being during the postpartum period. The SSPS closely aligns with known risk factors for paternal depression. The SSPS aims to measure Social Safety – the subjective sense of being secure, supported and not threatened in social relationships, and Social Pleasure – the extent to which social interactions are experienced as enjoyable and rewarding (Kirsch et al. 2021). The SSPS is composed of 11 self-report items rated on a Likert Scale from 1–5. Total scores range 11–55. Higher scores indicate greater feelings of social safety and pleasure. Lower scores indicate distress, social threat, or lack of pleasure in social contexts.

The aim of this study was to establish the rate of positive screenings using the EPDS in fathers or co-parents of the children of new or expectant mothers attending the Rotunda Hospital between July 2023 and January 2024. It also sought to identify key predictors of positive screenings including historical, obstetric, infant, demographic, and relationship variables. This study looked at the perinatal period as there are fewer studies available on this population compared to postnatal studies. To our knowledge it is the first study of its kind in Ireland.

Methods

Study setting and research design

This study utilised an anonymous cross-sectional survey conducted at a major standalone urban obstetric hospital in Ireland. The research was designed to assess mental health symptoms and social satisfaction in fathers and co-parents during the perinatal period. As fathers and co-parents were not patients of the maternity hospital, the survey was distributed indirectly via their partners. The study was conducted over a seven-month period, from July 2023 to January 2024, and captured data from both antenatal and postnatal contexts. A questionnaire was created using SurveyMonkey, which included demographic and clinical questions, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), and the Social Safety and Pleasure Scale (SSPS). Participants accessed the survey by scanning a QR code printed on research flyers.

Participants and recruitment

Recruitment relied on mothers attending antenatal or postnatal care being informed about the study and encouraged to share participation details with their partners. Flyers containing the survey QR code were distributed across multiple hospital services including antenatal clinics, postnatal wards, and perinatal mental health clinics. This method enabled broad reach across different stages of the perinatal period, while maintaining participant anonymity.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Individuals were eligible to participate if they were aged 18 years or older and were partners of women attending the hospital for antenatal or postnatal care. Individuals were excluded if they were under 18 years of age, or if the pregnancy involved a stillbirth, a diagnosis of a fatal foetal abnormality, or a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was completed using SPSS. Linear variables were compared using t tests. Categorical variables were compared using chi squared tests of analysing data compared to the EPDS screening as screening positive or negative, that is, it was treated as a binary variable. A Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyse the data relating to the SSPS as it was non-parametrically distributed.

An EPDS cut-off score ≥ 9 was used to indicate screening positive for depression. This was analysed as a binary outcome, that is, screened positive versus screened negative for depression.

A variable called ‘History of Mental Illness’ was created, it is a composite variable that is positive when an individual answered ‘Yes’ to any one of the following questions 1) Have you a history of mental illness? 2) Are you linked with a Mental Health Service (MHS)? 3) Have you been linked with a MHS in the past? or 4) Are you taking medication for your mental health? A ‘History of Mental Illness’ was then treated as a binary variable, that is, if answering ‘Yes’ to any of those four questions, you were seen as positive for a history of mental illness and if answering ‘No’ to all four questions respondents did not have a history of mental illness.

Results

In total, there were 123 respondents. 115 had completed the EPDS and these were included in the study. While it is not possible to capture the exact number of fathers during any period as some will not be involved during a pregnancy. There were 8,442 babies delivered in the Rotunda in 2023 (The Rotunda Hospital Annual Report, 2023). Using this figure there would have been approximately 4,925 deliveries during the 7 month study period from July 2023 to January 2024. Taken as a percentage 123 respondents would only equate to 2–3% of total fathers/co-parents during the study period. It should be noted that due to our recruitment strategy it was not possible to approach all fathers. Consequently, this response rate would be a significant under estimate.

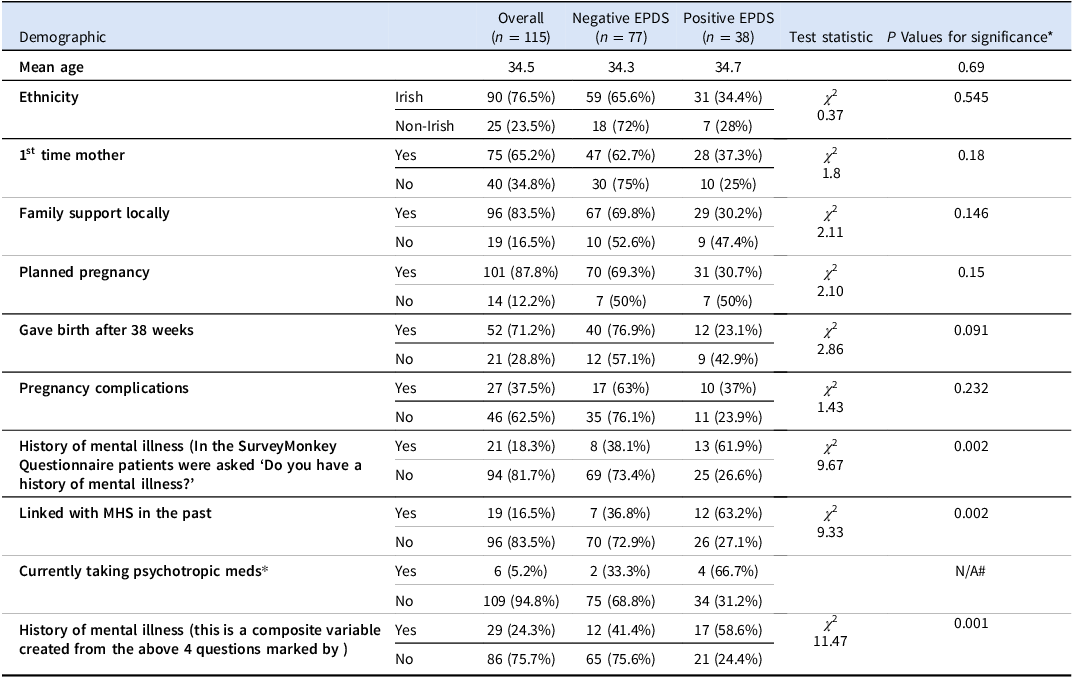

The average age of respondents was 34.45 years, approximately three-quarters (76.5%) were Irish, 87.8% had third level education, 96.5% were employed, and 100% of respondents were in a relationship with the mother of their child. The relevant positive findings and any unexpected relevant negatives are described in Table 1. The data for education, employment, being in a relationship or co-habiting could not be meaningfully statistically analysed due to low cell count. There was no association between positive screening EPDS and data for gender (P = 0.420); duration of relationship (P = 0.979); being a 1st time father/co-parent (P = 0.612); number of children (P = 0.653); or if their partner was postnatal or antenatal (0.199).

Table 1. Demographic and descriptive characteristics of the study population and comparison of the groups that screened positive and negative for depression

# Statistical tests were not presented when low cell count prevented valid results.

Of 115 respondents, 73 had postnatal partners and 42 had antenatal partners. Among our respondents, 33% had an EPDS score of ≥ 9 and 17.4% had an EPDS score of ≥ 12. There was a higher rate of positive EPDS screenings in the antenatal group (40.5%, 17/42) compared to the postnatal group (28.8%, 21/73). This difference between the groups was not significant, P = 0.199.

Using the composite variable described above 24.3% of respondents had a ‘History of mental illness’. There was a significant association with positive EPDS screening for patients who self-reported a history of mental illness (P = 0.002) or were linked with MHS in the past (P = 0.002). The composite variable provided an even stronger association (P = 0.001). Individuals with a ‘History of mental illness’ were more likely to screen positive for depression with an odds ratio of 4.38, (95% CI 1.80, 10.65). None of the other demographic, relationship, or obstetric variables were significantly associated with EPDS scores.

Analysing absolute EPDS scores, the mean overall score was 7.08 (SD 4.92), mean negative EPDS screenings was 4.25 (SD 2.35), and mean positive EPDS screenings was 12.82 (SD 3.58). The mean EPDS score for respondents with a history of mental illness was 9.93 (SD 5.6), respondents without a history of mental illness had a mean EPDS score of 6.12 (SD 4.2). This difference was significant (Mann–Whitney U test P = < 0.001). Question 10 on the EPDS is ‘The thought of harming myself has occurred to me’ . A past history of mental illness was associated with having experienced thoughts of self-harm in the past 2 weeks (P-value 0.007).

The average SSPS scores for the entire sample was 45.94 (SD 9.01). SSPS scores were higher in the group that screened negative for depression using the EPDS (49.43 (SD 5.59)), than those that screened positive (38.35 (SD 10.37)), thus indicating higher levels of social and pleasure satisfaction in the non-depressed group. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare SSPS to the variables listed in table 1 and their EPDS scores. SSPS scores were positively associated with screening positive for EPDS (P = 0.001); a self-reported history of mental illness (P = 0.027) and the composite variable – ‘A History of Mental Illness’ (P = 0.053).

Discussion

In 2023, the World Health Organisation reported the rate of depression in men was 4% (World Health Organisation, 2023). The results in this study suggested significantly higher levels in the perinatal population. Using EPDS score of ≥ 9 to identify people screening positive for depression, our results suggested up to 33% of fathers and co-parents screened positive for depression in the perinatal period. Even using a higher cut-off score, typically used in women, of ≥ 12, 17.4% screened positive for depression. Our finding using a cut-off of ≥ 9 is higher than any of the rates recorded in recent systemic reviews by Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Li, Qiu and Xiao2021), 1.2%–25.5% or Shafian et al (Reference Shafian, Mohamed, NasutionRaduan and Anne2022) 2.9%–23.8%. This is potentially explained by recruitment bias described below. However, our study aligned well with a prior Irish study from 2017, (Philpott & Corcoran, Reference Philpott and Corcoran2018), which recorded positive EPDS scores ≥ 9 in 28% and EPDS scores ≥ 12 in 12% of new fathers. They identified a number of risk factors for positive screenings including having an infant with sleep problems, a previous history of depression, a lack of social support, poor economic circumstances, not having paternity leave and not being married. Our study also found a mental health history to be a risk factor but interestingly a lack of social support was not found to be a risk factor. Our study may have been under-powered to identify the lack of social support as risk factors for depression. However, the association between positive screening with lower SSPS scores may indicate impaired social support.

Our study included respondents during the perinatal period. This contrasts with Philpott & Corcoran’s (Reference Philpott and Corcoran2018) study which focused on the postnatal period. Although it was not statistically significant, our study identified a higher rate of positive EPDS screenings in the antenatal (40.5%) compared to the postnatal cohort (28.8%). This suggests PPND may at least be as common in the antenatal period and further research is warranted to evaluate if it is potentially more common. This is a highly significant null finding as there is a growing awareness of postnatal depression but a more limited identification of depressive symptoms in the antenatal setting.

In our study a history of mental illness was a significant factor in predicting a positive EPDS score. A known risk factor for PPND is a history of depression. A history of mental illness was also associated with respondents having experienced thoughts of self-harm. Respondents with positive EPDS scores had lower SSPS scores. This suggests respondents suffering with positive EPDS scores experienced their social world as less safe, warm and soothing.

The results highlight the perinatal period as a risky time for mental illness especially in vulnerable fathers and co-parents who have a history of mental illness. There is very limited consideration of fathers and co-parents in the existing Model of Care for Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Services in Ireland (HSE, 2017). Future revisions of this model of care should include consideration of fathers. This study demonstrates that enquiring about paternal mental health and history of mental illness should be a part of routine care during GP consultations and perinatal care of mothers-to-be/new mother’s. Identifying individuals with a history of mental illness could allow clinicians to be cognisant of the elevated risk of PPND and provide education, monitoring, and onward referral where appropriate.

Given the high rates of depressive symptoms seen in this study and the broad and lasting impact of PPND on a family (Thiel et al. Reference Thiel, Pittelkow, Wittchen and Garthus-Niegel2020; Aktar et al. Reference Aktar, Qu, Lawrence, Tollenaar, Elzinga and Bögels2019; Sweeney & MacBeth, Reference Sweeney and MacBeth2016; Gentile & Fusco, Reference Gentile and Fusco2017), further research on PPND is indicated. As this study was conducted via an anonymous online survey, it limited our ability to follow-up with participants. Future research could consider a non-anonymous design to explore both maternal and paternal depression, particularly given the well-documented association between the two. To our knowledge, such a study has not yet been conducted in Ireland. A non-anonymous approach could enhance recruitment and facilitate longitudinal follow-up to better understand the dynamics of perinatal mental health. Such a study would ideally include both quantitative and qualitative component.

Limitations

The greatest limitation of this study is the response bias due to the online nature of the study. Only a small percentage (2–3%) of all partners and co-parents in our recruitment window replied to the study. More distressed fathers/co-parents may rate mental health history more negatively but also may be more likely to participate. Our study likely overestimates the prevalence of PPND, however it also demonstrates that there is a significant body of fathers and co-parents describing high degrees of depressive symptoms. Conversely it is acknowledged in the literature that men are reluctant to seek help for their own health. This may somewhat dampen the effect of response bias (Rominov et al. Reference Rominov, Giallo, Pilkington and Whelan2018).

This study also highlights the difficulty in studying fathers and co-parents in maternity centres where they are not seen as patients. Steps could be taken to include them more in maternity care but this inclusion needs to be carefully balanced with the mother’’s right to confidentiality and be cognisant that rates of domestic violence rise in the perinatal period. A better focus for screening and intervention in this group may lie with primary care. Small sample size with high percentage of third level education and Irish descent suggests the results may be less generalisable to more diverse populations.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest there is an elevated risk, for fathers and co-parents, of developing symptoms of depression in the perinatal period. It suggests that the antenatal period and not just the postnatal period is a time of elevated risk. Our study highlights the challenges in accessing fathers and co-parents in an Irish maternity care setting. This was demonstrated by our response rate and the challenges we faced in recruiting fathers and co-parents. Given the known positive association between maternal and paternal depressive symptoms, screening for partner’’s mental health history at antenatal appointments should be considered. GPs could consider asking fathers’ to be or new fathers about their mental health history. Consideration for how best to support fathers and co-parents in the perinatal period should be incorporated in future models of care for the Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Service. This should be done in close collaboration with primary care as fathers/co-parents are not patients of maternity hospitals and would not be in a position to access Specialist Perinatal Mental Health Services. Obstetricians and midwives should also have pathways where they identify a concern.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Ethical approval was obtained prior to the commencement of this study from the Research Ethics Committee of the Rotunda Hospital, Dublin. Any personal data collected in this study was irrevocably anonymised at the point of collection, hence no personal data was used or stored for this study.