Introduction

In many parliamentary systems, especially where the legislature is elected through proportional representation and where no party typically gains a clear majority, a lengthier government formation process often ensues after an election is held. In such systems, parties must engage in inter‐party discussions to determine if a majority government is possible, or decide upon a viable minority cabinet that can command potential majorities for the passage of budgets and legislative initiatives. This process may require months of negotiations to ascertain which combinations of parties, and in which policy areas, there exist agreement upon before a government is installed. For example, in Sweden, a country where government formation has typically been a swift process, the 2018 election resulted in a drawn‐out formation process lasting 134 days (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Bäck, Hellström and Lindvall2020). In this case, the parties involved in bargaining reached compromises in several policy areas, which may have influenced the policies later implemented by the government. In this paper, we ask more generally, does a longer bargaining time influence the policy‐making capacity of governments?

The prevailing wisdom of the consequences of longer cabinet formation processes is that they are mainly associated with costs, and scholars have asked if coalition bargaining is ‘wasting time’ (Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2003). For example, Bernhard and Leblang (Reference Bernhard and Leblang2006) argue that external costs of coalition bargaining increase to the extent that it remains unclear what the new government will look like and in which direction a country will be heading. Specifically, economic actors’ reactions to uncertainty about future government policy can have detrimental effects, such as investment delays and currency and stock market volatility.

In line with a growing case study literature (see, e.g., Albalate & Bel, Reference Albalate and Bel2020; Bouckaert & Brans, Reference Bouckaert and Brans2012; Van Aelst & Louwerse, Reference Van Aelst and Louwerse2014), we challenge this prevailing wisdom and argue for a perspective that bargaining time might also be constructive (see also Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008). We focus on such potential consequences of longer bargaining periods on governments’ policy‐making productivity. We argue that bargaining time, regardless if it results in a written policy agreement, is an investment in future reform productivity. Longer formation processes suggest the occurrence of a sequence of offers and counter‐offers, which credibly reveal private information originally held by single parties, making party policy preferences, reservation values and walk‐away values public.

In addition, time spent negotiating the broad contours of an entire policy programme allows for logrolling within and beyond specific policy measures (de Marchi & Laver, Reference De Marchi and Laver2020). Longer negotiation periods also indicate that the bargaining parties have negotiated deals over conflicting policy issues and have allowed parties to build trust between them and gain support for future policies within the party organizations (Luebbert, Reference Luebbert1986). This should be especially important when the government consists of parties that are ideologically distant from each other since greater ideological differences in a prospective coalition come with greater challenges for the parties’ leadership in rallying their own parties behind the negotiators. We thus expect that longer negotiation periods mitigate problems of intra‐cabinet policy conflict, resulting in higher reform productivity.

We evaluate our theoretical expectations by combining a newly compiled data set on economic reform measures enacted in 10 Western European countries (1978−2017) produced by a coding of quarterly country reports issued by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) and the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) with information on the bargaining environment before the investiture of a government. Analysing our data set that includes 5180 reform measures by 104 coalition cabinets, we show that more time spent in coalition negotiation results in higher reform productivity and that such inter‐party exchange is more useful the greater the ideological conflict between the parties. As such, we conclude that coalition negotiations, even those that fail to reach an agreement, benefit government policy productivity.

These findings have important implications for our understanding of the consequences of extended government formation processes, suggesting that the setback of temporary uncertainty for financial markets caused by such political events may be outweighed by an increase in reform productivity during the cabinet's time in office. These findings may also contribute to our understanding of why some governments last longer than others, suggesting that cabinets that have taken a long time to form are likely to be more productive in terms of making much needed policy reforms, which should decrease the risk of government crises.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Coalition governments are a challenging form of government as they bring together parties that have competed in elections before cabinet formation and will do so again in the future. The parties in a coalition government often have different policy priorities and conflicting preferences regarding the contents of government policy and the allocation of portfolios. The dangers of governing in coalitions include disloyalty of the partners, conflict over and failure to make decisions in government, which may result in policy stalemate or early termination and electoral punishment for the parties involved. The literature on coalition governance has highlighted these dangers and investigated which mechanisms are chosen to tame them. Most of this work is concerned with institutions that come into being only after the coalition has been formed and that aim at policing and influencing the governing process (Strøm et al., Reference Strøm, Müller and Smith2010). The relevant institutions, for example, include watchdog junior ministers (Lipsmeyer & Pierce, Reference Lipsmeyer and Pierce2011; Thies, Reference Thies2001), shadowing ministers (Fernandes et al., Reference Fernandes, Meinfelder and Moury2016) and parliamentary committees (Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005). A few studies have focused on the front end of coalition governance and have investigated when formal coalition contracts are established (Müller & Strøm, Reference Müller, Strøm, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008) and how they may influence coalition governance and durability (Krauss, Reference Krauss2018; Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008).

Our main argument is that it is rewarding to start even earlier. We argue that considering the process of bargaining during the government formation stage is important in its own right and adds to our understanding of how policy productive a particular coalition is likely to turn out to be. We here elaborate on why coalition negotiations may have such positive consequences for government reform productivity. We note a variety of potential benefits associated with coalition negotiations, each of which we will explicate below: putting policy decisions in the hands of politicians who take a larger picture of the bargaining process, opening avenues for logrolling over different issue areas and issues which may appear on the government agenda only with considerable time difference and diffusion of responsibility for policy concessions among the party elite, are all favourable conditions for agreeing on a substantive policy programme in the bargaining arena of coalition formation.

Coalition bargaining is conducted by party leaders. Bargaining is a core task of all politicians, and its results are crucial for their professional careers (Sheffer et al., Reference Sheffer, Loewen, Walgrave, Bailer, Breunig, Helfer, Pilet, Varone and Vliegenthart2023). Bargaining over government formation is also important for their country's policy trajectory. Therefore, with the occasional exception, when parties bargain with other parties to show that a particular government is not viable, politicians are likely to be interested in the successful conclusions of a bargaining round. Experimental research indicates that politicians in bargaining situations aim for their own benefits but at the same time make constructive offers and counteroffers (Sheffer et al., Reference Sheffer, Loewen, Walgrave, Bailer, Breunig, Helfer, Pilet, Varone and Vliegenthart2023).

Qualitative accounts of the negotiation process (Andeweg et al., Reference Andeweg, De Winter and Dumont2011; Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Bäck and Hellström2021; Müller & Strøm, Reference Müller and Strøm2000) suggest that there are some important differences between inter‐party bargaining before the start of government as compared to once a coalition cabinet is in office. These differences relate to which actors participate, their goals and motivations, the attribution of responsibility to political actors, the timing of policy decisions to each other and, more generally, what is at stake. We suggest that these differences help forging inter‐party agreement on government policies in the context of coalition formation and lead to policy productivity gains of governments, even if no written agreement has been concluded.

The coalition governance literature cited above notes the challenges arising from the centrality of cabinet members at the governance stage when policies are made (Laver & Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996). The government formation process sidelines these politicians and centres on the grandees of the parties as the key actors. Party leaders remain central throughout the process, calling upon policy experts to help them determine the contours of the final deal. While individual politicians may anticipate a ministerial role in a subsequent government, they lack such standing and influence at this initial bargaining stage. In a sense, the roles are reversed from the governance stage, where decision‐making is delegated downward. In the formation situation, the delegation is upward, as party leaders have the overarching goal of ensuring their party's government participation, rather than specific policy choices.

Of course, these party leaders must weigh the cost of policy concessions against the benefits of government participation and appointment power, but the choice at the negotiation stage is still the leader's, not the subsequent appointees. Having weighed these costs and benefits, and thereafter agreed to a whole package, when it comes to the implementation of such policies, inter‐party differences on specific policies should be less of an issue in inhibiting reform productivity. Time spent negotiating the broad contours of a policy programme allows for logrolling within and beyond specific policy measures (de Marchi & Laver, Reference De Marchi and Laver2020).

While this article focuses on the challenges inherent in governing in coalitions, these are not the only constraints on reform productivity (Weaver & Rockman, Reference Weaver and Rockman1993). For instance, institutionally strong second chambers, politically incongruent with the first chamber and constitutional courts, can considerably limit the scope of governments. The presence of such institutional veto players (Tsebelis, Reference Tsebelis2002) should depress a government's reform productivity. While we acknowledge the importance of such constraints, for reasons of space this paper confines to statistically control for their presence (see ‘Methods and Data’ section; for an analysis focusing on veto players and reform productivity, see Angelova et al., Reference Angelova, Bäck, Müller and Strobl2018).

Informational gains associated with coalition negotiations

When coalition negotiations begin, the parties at the bargaining table do not have all information relevant for striking a deal. For one thing, despite all information about party stances and pledges readily available, parties do not know for sure the policy priorities and preferences of other parties. To provide one drastic example of revealing information in bargaining a coalition deal, we refer to what was probably the most important decision in Austrian politics in several decades – approaching the EU and eventually becoming a member in 1995. It was in the negotiations establishing the SPÖ‐ÖVP grand coalition in 1986 when the issue of EU accession – an issue that was not present in the 1986 election campaign – received a decisive push. The SPÖ revealed that it was willing to move in the direction of EU membership, relaxing its long‐held stance of incompatibility with the country's military neutrality. This unforeseen move helped forging the grand coalition and maintaining it until 1999. While learning at that scale in coalition negotiations may be rare, it is common that the parties need negotiations to find out on which issues they can find agreement with other parties.

Longer coalition formation processes suggest the occurrence of a sequence of offers and counteroffers, which would credibly reveal private information originally held by single parties (Diermeier & van Roozendaal, Reference Diermeier and van Roozendaal1998). Party policy ‘preferences, reservation values, and walk‐away values’ are made public (Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008, p. 359). In this way, each day spent bargaining produces substantive information that can help in later bargaining periods. Political information is revealed through an extended process whereby parties can determine on which policies majorities are possible and on which issues time ought not be spent during the subsequent governing term because a majority would be impossible to construct. Saalfeld's (Reference Saalfeld, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008) analysis provides some evidence of these unobservable information exchanges. He finds that longer bargaining time increases the likelihood of a replacement cabinet but not early dissolution/elections. These results suggest that a longer bargaining time could have provided parties with information on what alternative majorities were possible, and as such, a new government could form without the need for new elections.

This bargaining process might be especially important when minority cabinets form. In such negotiations, support parties are made aware of the areas for which they may be able to contribute to a parliamentary majority, while governing parties concurrently learn which initiatives they can advance that are likely to achieve majority support, so as to avoid looking ineffective in the eyes of the public. The negotiation process reveals the parties’ private information, but it also reveals information about the negotiators themselves and about intra‐party cohesion. Party leaders learn how assertive their interlocutors are as well as how much party loyalty they can assert within their party. In this manner, more realistic agreements can be reached, which parties are less likely to back down on at a later stage. In other words, unreliable or unstable coalition partners can be identified ex ante through extended negotiations. Such information gains can prevent the formation of a coalition that would be unable to produce steady policy output. Longer negotiation periods can thus be used to identify which potential parties are best able to commit to a productive governing term.

As media reports, party press releases, or leaked documents make their way to the public and interest groups, governing parties learn ex ante which policy areas might produce a public backlash or a rebellion of key party constituencies or interest groups. In the German coalition negotiations following the 2021 election, for example, the Christian Democrats (CDU) leaked that it was interested in a coalition with the Liberal FDP and the Greens. This allowed all relevant parties to assess how the public would react to such an arrangement. Ultimately, such a coalition did not form, and one may wonder to what extent the pushback from party supporters influenced the smaller parties’ decisions to not work with the CDU.

Finally, coalition negotiations provide the opportunity to make information gains with respect to the policy instruments to be employed. When it comes to such detail, some parties have little more to offer than campaign slogans and broad‐brush manifesto claims. Even when parties have seriously thought about such instruments, the discussions may show that envisaged levers are unlikely to work in practice, that they are inefficient, or that legal constraints prevent their use. Experienced and resourceful parties may make considerable gains in such technical discussions. As one scholar of negotiation processes has put it, ‘it is less important to sell one's own position than to eliminate alternatives … showing that better alternatives are impossible and possible alternatives are worse for the other party’ (Zartman, Reference Zartman2008, p. 27). Such insights may be fostered when coalition negotiators have access to information from neutral institutions such as economic research institutes or the administration. In the words of Peterson and De Ridder (Reference Peterson and De Ridder1986, p. 566), ‘the negotiation process is largely ‘a process of discovering, mapping, and creating a consensus on certain issues’. In any case, finding agreed upon policy instruments requires time but is important for the subsequent policy productivity of government.

How the bargaining process contributes to government productivity

Forging policy agreements requires negotiations between the parties aiming for a coalition government. Such negotiations typically begin with fixing a plan of how to structure the process and a rough time plan. They continue with bargaining over policy issues and conclude with portfolio design and allocation (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Ilonszki and Müller2019, Reference Bergman, Bäck and Hellström2021; Müller & Strøm, Reference Müller and Strøm2000). Coalition governance principles are likely addressed early on, with the institutional solutions taking shape towards the end of the negotiations. The lion's share of time is spent on policy. Some time is spent on fixing issues on which the parties agree, but most time and effort goes into discussing the issues which may potentially divide partners.

When party preferences diverge and the issue is salient for all parties, the negotiations typically unfold by a stepwise process of narrowing the gaps between the parties via mutual concessions until a compromise is found. The literature on political negotiations tells us that each such step requires time (and patience from the other side) (Zartman & Berman, Reference Zartman and Berman1982). Periods of toughness aim at raising the price for concessions; they are followed by periods of softness once negotiators have shown their commitment to the case and prepared the ground for making concessions in inter‐party communication (Luebbert, Reference Luebbert1986). The process also serves as a means of identifying issues which have different salience for the partners (because their preferences are ‘tangential’) which may be settled by logrolling, allowing each partner to anchor its party positions on the salient issues in the coalition deal. Such solutions turn zero‐sum into positive‐sum games (Zartman & Berman, Reference Zartman and Berman1982; Raiffa et al., Reference Raiffa, with Richardson and Metcalfe2002, p. 279).

Even negotiations on issues which remain unresolved can have a productive function, as they provide valuable information on what is feasible in a particular coalition and what is not. Such issues might be explicitly excluded from policy‐making as political actors refrain from initiating policies with a high likelihood of failure when in office. De Marchi and Laver (Reference De Marchi and Laver2020) explicitly model such ‘tabling’ of issues. Self‐restraint in addressing issues helps in concluding the bargain over government formation. Once the government has been installed, it helps avoiding unproductive conflict and allows focusing time and energy on politically viable reform areas. While tabling issues thus may allow for productivity gains, it also involves considerable risk as external shocks may activate the issues and enforce hard‐to‐resolve problems on the government agenda (de Marchi & Laver, Reference De Marchi and Laver2020, Reference De Marchi and Laver2023).

Studies of the bargaining process have focused on one crucial aspect – its duration (de Marchi & Laver, Reference De Marchi and Laver2020; De Winter & Dumont, Reference De Winter, Dumont, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008; Diermeier & van Roozendaal, Reference Diermeier and van Roozendaal1998; Ecker & Meyer, Reference Ecker and Meyer2020; Golder, Reference Golder2010; Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2003). Explanations to why some cases are characterized by severe ‘bargaining delays’ have centred on actors’ uncertainty about the preferences and strategies of potential partners and the political complexity of the bargaining situation. Uncertainty always exists, but it seems particularly important in a newly elected parliament (Golder, Reference Golder2010). Also, the presence of larger extremist parties has been found to make the formation process more challenging and hence longer (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Hellström, Lindvall and Teorell2023). Some studies have also explored the relevance of institutional factors such as formation rules (De Winter & Dumont, Reference De Winter, Dumont, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008; Golder, Reference Golder2010). For our purpose, the studies by Ecker and Meyer (Reference Ecker and Meyer2020), and de Marchi and Laver (Reference De Marchi and Laver2020), are particularly relevant, as they focus on the policy agenda the negotiators need to address.

While most studies try to explain the total length of the formation period, Ecker and Meyer (Reference Ecker and Meyer2020) focus on the individual bargaining rounds. Of particular interest is their focus on preference tangentiality (negotiating parties are concerned about different and not incompatible issues) and preference divergence (negotiating parties are concerned about the same issues but have divergent preferences). Preference divergence typically requires the ‘tabling’ of issues or hard‐to‐find compromise solutions, while preference tangentiality allows for logrolling strategies. Ecker and Meyer (Reference Ecker and Meyer2020) find that parties are less likely to enter coalition bargaining in case of strong preference divergence and are more likely to positively conclude the talks in shorter time the more tangential their preferences are.

Behaviourally modelling government formation as a high‐dimensional logrolling process, de Marchi and Laver (Reference De Marchi and Laver2020) show that different party system configurations are associated with varying logrolling opportunities. The fewer opportunities the bargaining parties have to conduct logrolls, the more difficult and hence time consuming the bargaining process.

The literature thus provides important insights into coalition bargaining processes and why some of them take considerably longer than others. A few authors have also considered what bargaining duration signals about the likely future of the cabinet. King et al. (Reference King, Alt, Burns and Laver1990) posit that longer periods of bargaining suggest a complex partisan environment that will lead to earlier dissolution of cabinets. Yet their empirics support an alternative position advocated by Strøm (Reference Strøm1985) in which a longer bargaining time makes the parties realize that prospective alternative potential constellations will be costly to form and retrospectively realize that their negotiating time had cleared away potential obstacles to government unity. In other words, a longer bargaining time should increase party readiness to compromise in subsequent bargaining rounds or when in office. Following this line of argument, one could thus expect a greater number of policy compromises to arise from longer bargaining times.

As other instances of uncertainty, extended coalition negotiations may indeed produce external costs. Time spent upon coalition formation also reduces the time remaining for governing and enjoying the spoils of office. For these reasons, parties with the ambition to govern are typically aware that time is a scare resource that is to be spent wisely. If they do so, they make an investment with the expectation that it will pay off. In contrast to those who focus on the uncertainties before and during the bargaining period, we highlight the ex post effect, suggesting that the bargaining period reduces future governing uncertainty.

The substantive motivation for the study of bargaining duration rests on the political and economic costs of long bargaining durations (Bernhard & Leblang, Reference Bernhard and Leblang2006; Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2003). The external costs of coalition bargaining increase to the extent that it remains unclear what the new government will look like and in which direction a country will be heading. Specifically, as mentioned above, economic actors’ reactions to uncertainty about the future government policy can have detrimental effects such as investment delays and currency and stock market volatility (Bernhard & Leblang, Reference Bernhard and Leblang2006).Footnote 1

Accordingly, Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2003) have asked whether long formation periods are ‘wasting time’. Any seasoned political observer can name coalition negotiations that moved with glacier speed and while installing a government produced little in terms of policy. Yet there are reasons to expect that such cases are infrequent as the public is aware of the amount of time spent at the bargaining stage. This, in turn, might raise general expectations that the outcome outweighs the costs of uncertainty. Parties are aware of the potential criticisms of ‘wasting time’ and the scorn they will receive for apparently meagre results (‘The mountains circled and a little mouse was born’). Accordingly, parties are likely to aim for results in the negotiations that can be ‘marketed’ to the mass media in the short term and which will make the resulting government more productive in the longer term. To the extent they succeed in these goals, the time investment has been a worthy one.

Here, we can also draw on the literature that focuses on the role of written coalition agreements. While some authors have deemed written coalition agreements ‘little more than window dressing’ (Laver & Schofield, Reference Laver and Schofield1990, p. 189) or merely ‘symbolic’ (Timmermans, Reference Timmermans1998, p. 419), others suggest that such documents have an important role in coalition governance. Written coalition agreements document what has been agreed upon during the negotiations, and if communicated well, such contracts help maintain the commitment of the parties and reduce conflict between them. Coalition agreements can also serve that purpose by including mechanisms for monitoring and conflict management and resolution (Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Bräuninger, Debus and Indridason2016). Indridason and Kristinsson (Reference Indridason and Kristinsson2013) use the length of a coalition bargaining process as a proxy for comprehensiveness in terms of covering policy issues and details of cooperation. Krauss (Reference Krauss2018) finds that the time spent bargaining is correlated with the length of agreements and the strength of included control mechanisms. Shorter agreements and/or bargaining time might be able to settle initial policy conflicts or identify broad goals, but they are less likely to provide guidance or constraints on future coalition issues (Indridason & Kristinsson, Reference Indridason and Kristinsson2013).

While it is most intuitive to see a relationship between the input in terms of time invested into negotiating a particular coalition deal and the resulting coalition cabinet's subsequent policy output, our argument goes beyond bargaining rounds that were successfully concluded by government formation. Even bargaining rounds that do not result in a written and public policy agreement, are potentially useful as each round produces substantive information that can help in further bargaining rounds. These inputs can relate to information derived from the administration, such as the workability of policy means, or the budgetary leeway the new government will have. Other types of information generated in unsuccessful bargaining rounds relate to the policy compatibilities with other parties – which policies produce spontaneous consent, which seem within the feasibility of negotiations and where are the red lines that cannot be transgressed?

Such information is particularly valuable when building minority government, when coalition discipline of majority coalitions is expected to be weak, when the enactment of particular policies requires surplus majorities and when issues are particularly sensitive in society and policies require broad consensus. Finally, parties may also learn about how their own party organization reacts to looming compromises on specific issues.

The more details potential coalition members discuss during bargaining, the clearer the policy benchmarks and the more difficult it should be to renege subsequently during a government. Such reasoning is used by Warwick (Reference Warwick1994) who argues that a greater amount of bargaining time indicates a high level of detail in negotiations, which could subsequently produce governing coalitions lasting longer. Thus, we would expect that a greater investment of time spent in negotiating a potential agreement would subsequently lead to greater productivity over the government's tenure. Following this line of argument, we hypothesize that

H1: The longer the bargaining period when a coalition government forms, the greater the government's reform productivity.

When an extended bargaining process is particularly useful

Regardless of how diligently the negotiators work, unforeseen contingencies will not be covered during the government formation process. There are also problems of enforcement. Anything agreed to during negotiations relies upon the parties themselves for enforcement. There is no third‐party or a neutral arbiter (law court or court of arbitration) to implement policies discussed during the negotiation period. For settling differences in implementing outcomes associated with a contract, a structured communication process between the partners is one such approach towards conflict resolution (Frydlinger & Hart, Reference Frydlinger and Hart2023). This is what coalition designers do by establishing mechanisms and procedural rules for conflict management (Andeweg & Timmermans, Reference Andeweg, Timmermans, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008), describing the process by which disagreements will be settled, such as holding special meetings.

We argue that the process of negotiating the coalition is fundamental for further cooperation. It helps create a mutual understanding beyond the letter of any document produced and in making the partnership work in practice. Through the negotiations, parties become better aware of the sensitivities and red lines of their partners. Negotiators also know about the many alternative policy solutions for the various issues that have been discussed and dismissed until joint solutions have been found. This induces future ministers to feel the constraints set forth. Negotiators also learn about each other in terms of the individuals’ sincerity, reliability, intra‐party assertiveness and confidentiality. Negotiation processes may also create bonds of camaraderie and mutual considerateness from a joint endeavour.

In short, negotiation processes may create trust and social norms that are essential for successful cooperation under a coalition contract. The more that parties invest in negotiating the coalition deal, the more they can later capitalize on this investment. Thus, the time spent negotiating the formation of a coalition agreement can be viewed as investing time in a co‐specific asset, meaning that returns from that investment depend heavily on the joint cooperation of the partners (Hall & Soskice, Reference Hall, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001; Wood, Reference Wood, Hall and Soskice2001). We expect that longer bargaining processes generate more trust among the actors involved in coalition bargaining.

This should be especially important when parties are ideologically distant from each other since such bargaining situations should create greater challenges for the parties’ leadership in rallying their own parties behind the coalition negotiators. According to Luebbert (Reference Luebbert1986), the duration of coalition negotiations is determined first and foremost by intra‐party concerns, as party elites require time and effort to sell the substance of the emerging coalition deal to their own parliamentary party group and the party at large. Such consensus building is of immediate importance when the coalition deal requires confirmation via inclusive decision‐making mechanisms within the parties (De Winter & Dumont, Reference De Winter, Dumont, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008). However, party consent to government policy remains crucial for the passage of policy throughout the lifetime of a coalition (Timmermans, Reference Timmermans2006). The intra‐party processes accompanying coalition bargaining are thus part and parcel of the investment into negotiations and functional to government reform productivity. They should also reduce the danger of backbench rebellions in parties that have made painful policy concessions during the formation process, as these are seen as an integral part of a bigger deal (Williams, Reference Williams2011).

Consider the following thought experiment. Rather than negotiating the terms of a coalition themselves, a coalition is presented with an agenda identical in content but drafted by external experts, say political scientists. Coalition actors would then lack the extra information from the negotiation process, including getting to know the sensitivities of the partners, the knowledge about tried and dismissed alternative solutions and how the deal is balanced over different policy sectors and issues. The coalition actors would also miss the camaraderie that emerges from long and eventually successful negotiations. Also, the parties at‐large would lack background information on why their party has agreed to some concessions. Viewed from this perspective, it is easy to see that the bargaining process may make an important contribution to make the coalition deal working in the practice of governing. While building trust between the parties and broad intra‐party consensus through the bargaining process are important to any coalition, they are all the more important, the further apart the partners. Any policy concessions made during the process of bargaining should thus face less electoral costs than when made ad hoc, lacking a political balancing made during a governing term. We thus expect that

H2: A longer bargaining period in coalition formation mitigates the negative effect of intra‐coalition ideological conflict on reform productivity.

Methods and data

Dependent variable: Economic reform productivity

In our analyses, we examine 10 Western European countries that have experience with coalition government. The countries included are Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden. We have selected a 35‐year time‐period (1978−2017) for external validity purposes beyond any set of unique temporal circumstances such as economic crises, the fall of communism or specific stages of the European integration project. The focus of our analysis is on changes to the status quo on the classic left–right dimension that has been the primary dimension of European competition in the post‐war years (see, e.g., Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2014).

We have identified authoritative sources that report on such policies in a standardized format over an extended time period in quarterly or monthly country reports issued by the EIU and (bi)yearly OECD country reports.Footnote 2 After manually coding more than 1000 EIU and OECD reports, we have identified 5180 specific reforms made by 104 coalition governments. Such an empirical strategy allows us to examine actual policy output, instead of relying on expenditure or budget measures.

The EIU and OECD reports contain information on economic and political developments in a given country, including information about concrete policy changes that might affect potential business investors or international organizations. OECD reports are a standard information tool for government agencies and academics for detailed information on economic policies. The EIU reports collect information from various channels including official government documents, contact with government officials and media reports. Student coders were trained in identifying relevant policy measures and coding measures that seek to change status quo policy either by law, decree, action of national government or approval of government initiatives by the legislature. The reform areas that coders were instructed to identify are listed in online Appendix A. The online Appendix also includes more detailed information on the coding process, coder training and a discussion on inter‐coder reliability.

After identifying socio‐economic reform measures in the reports, we total the amount of reforms that occurred during a government's term. If a reform occurred on the cusp between two governments, secondary sources were sought out to properly associate a reform with a given government. After the total number of reforms per government was identified, a project leader verified that the content of the reforms does indeed fall within our substantive areas of interest. If there is a discrepancy in the number of reforms, then an additional research assistant was asked to differentiate between the differing counts until the two agreed.

Measurement of the independent variables

Most independent variables come from the Party Government in Europe Database (PAGED) (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Bäck and Hellström2021), which builds upon previous coalition politics data sets (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Ilonszki and Müller2019, Reference Bergman, Bäck and Hellström2021; Müller & Strøm, Reference Müller and Strøm2000; Strøm et al., Reference Strøm, Müller and Bergman2003, Reference Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008) hosted by the European Representative Democracy Data Archive (ERDDA). This database contains information on government formation processes as well as the subsequent make‐up of governments. Since our primary theoretical assumption is that time spent during negotiations is used to develop a productive policy agenda, we make use of a variable identifying the number of days of negotiation for the Successful Round that led to the formation of a government.

To evaluate our second hypothesis (H2, the conditioning effect of bargaining time on intra‐coalition policy conflict), we also use the PAGED data set to identify the parties contained within the governing coalition. We follow Becher's (Reference Becher2010) operationalization of ideological divergence as the unidimensional distance between the most extreme left and right parties in the governing coalition. Because our dependent variable is a measure of socio‐economic reform productivity to identify positions on socio‐economic policy, we use the ‘state involvement in the economy’ left–right value suggested by Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011), which is based on data drawn from the comparative manifesto project (MARPOR; see, e.g., Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2017).Footnote 3 This measure is based on Tsebelis’ (Reference Tsebelis2002) assumption that each partisan member of government is a potential veto player.Footnote 4 Such an operationalization is frequently used in the current research on socio‐economic policy reforms (see, e.g., Aaskoven, Reference Aaskoven2019; Zohlnhöfer & Voigt, Reference Zohlnhöfer and Voigt2021).

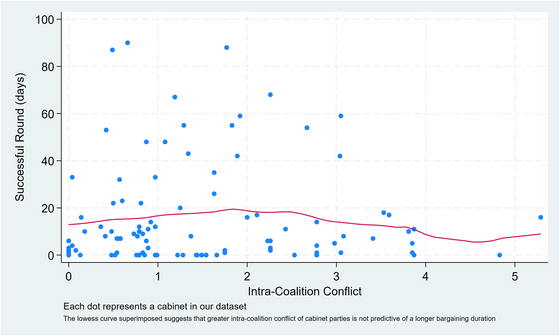

Figure 1 displays the relationship between intra‐coalition conflict and the total number of days in the successful cabinet duration process, also with a smoothed local polynomial. Different bargaining rounds within a coalition negotiation may contain different constellations of potential parties. Here displayed is the final constellation and how many days it took for those parties to agree to form a government. Note from Figure 1, though perhaps not intuitively, that there is no correlation between the duration of negotiations and the ideological range of the resulting coalition (r = −0.08, p < 0.94). This is in line with findings that indicate no relationship between ‘preference divergence’ and the duration of government formation (Ecker & Meyer, Reference Ecker and Meyer2020).

Figure 1. Successful bargaining duration and intra‐coalition conflict.

We use several control variables included in the PAGED data set that could affect reform output. As these might also be affected by bargaining time, the resulting effects of these variables would demonstrate an indirect, mediated effect of bargaining time. With their inclusion, we isolate the direct effect of bargaining time (Saunders & Blume, Reference Saunders and Blume2019). First, we include a measure of the comprehensiveness of the coalition agreement, coded as to whether there is agreement on no issues (0), a few selected policies (1), a variety of issues (2) or whether the coalition is based on a comprehensive policy programme, covering most issue areas in some detail (3). Second, we include a measure of whether there are discipline‐related rules included in the agreement. Varieties in commitment to coalition discipline in legislation are coded 0 (no commitment to coalition discipline), 1 (commitment to discipline only on explicitly listed policies), 2 (some policy areas explicitly excluded from coalition discipline) or 3 (always a commitment to having coalition discipline).

As our argument goes beyond bargaining rounds that were successfully concluded by government formation, we also include total bargaining time, which is the total number of days from the start of bargaining (including unsuccessful rounds) and the formation of a government. The PAGED data set also identifies the duration of the government, for which we control as mechanically, longer governments may also be more productive. This variable along with the majority status of government has been identified as impacting government productivity (Angelova et al., Reference Angelova, Bäck, Müller and Strobl2018), and it also indicates if a government was a minority, minimal winning or surplus coalition. As such, we include these controls to assess the incremental validity of our key independent variables (Wysocki et al., Reference Wysocki, Lawson and Rhemtulla2022).

We also control for potentially confounding effects of economic factors Footnote 5 on reform output – calculated as the average of three macroeconomic indicatorsFootnote 6 during the duration of a given cabinet: (1) unemployment rate, (2) the percentage of elderly population (over 65) and (3) the average GDP growth over the cabinet term. Greater proportions of the unemployed and elderly put financial pressure on regimes to alter social or labour policies, although a large share of beneficiaries might also limit a blame‐avoiding government's efforts at reform (Pierson, Reference Pierson and Pierson2001). Relatedly, GDP growth directly impacts a government's taxation revenues while recessions might produce conditions favouring Keynesian demand management through increased government spending or subsidization of labour or business or demand‐side policy measures of market‐liberalization, stimulating entrepreneurship and investment.

Empirical analysis

We here present analyses using multi‐level negative binomial count regression models on the total number of economic reform measures per cabinet. Negative binomial models are suitable for over‐dispersed count data, meaning that the conditional variance exceeds the conditional mean, which is true for all our models (indicated by the alpha coefficients in Table 1). As cabinets are nested within countries, we must be concerned with country‐level heterogeneity, as some nations might tend to have a greater number of reforms than others. For example, country‐specific characteristics in the design of social policy, or levels of taxation, are factors that might produce a higher or lower potential for reform that cannot be captured by variables included in the models. The use of hierarchical models accounts for differences in country‐level means and clustered errors for country‐level heterogeneity in reform productivity.Footnote 7

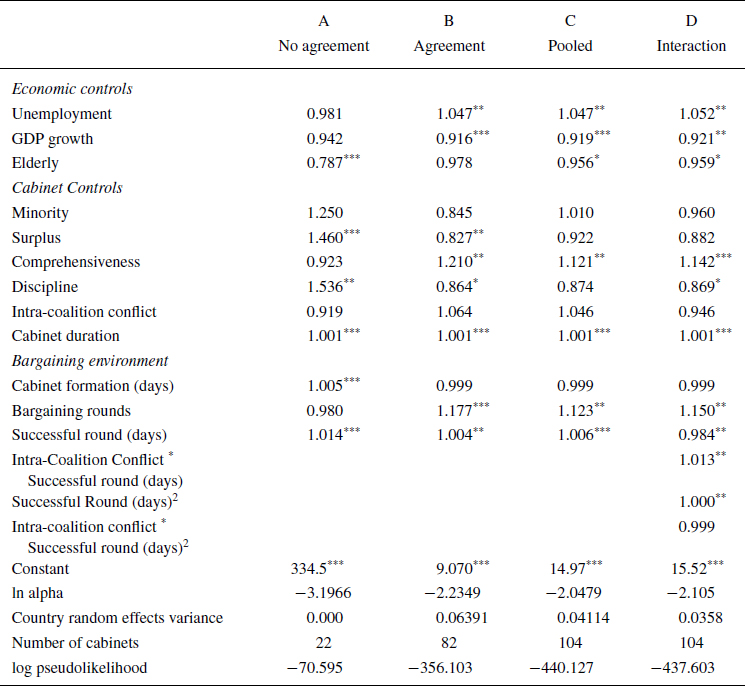

Table 1. Analyses of bargaining time and reform productivity

Note: Country random‐effect coefficients and clustered errors.

Incident rate ratios displayed. Base cabinet type is minimum winning

*** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1

As our theoretical section was suggestive of potentially different mechanisms between governments that do and do not come to a formal written agreement, we separately analyse the impact of the independent variables on the count of total socio‐economic reform productivity. As a reminder, our key variable we are looking for the direction and significance of is the effect of bargaining time. We expect this to be positively signed and statistically significant. A third model pools all governments in a single model. Our second hypothesis focuses on the conditioning role that intra‐coalition conflict might have on the effect of bargaining time. A fourth model introduces this conditional effect.

When positing interaction effects, Berry et al. (Reference Berry, Golder and Milton2012) have several suggestions that challenge the authors to test as many predictions as conditional theory would allow. One is to posit, even if not a specific hypothesis, relationships with both variables as possibly ‘conditioning’ the other (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Golder and Milton2012, p. 653). A second suggestion is to identify expected marginal effects at the extremes of the constituent variables (p. 658). A third, in light of the two noted above, is to not depend on linear functional forms if it is not appropriate to do so (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Golder and Milton2012, p. 669). According to our theoretical argument, we expect that for cabinets with internal conflicts, greater time allows for them to work through such conflicts. That said, we made no claim that these conflicts could be worked through in a single day. As such, we would predict that at low levels of bargaining time, there would be no marginal impact of more time (I). Likewise, should there be low levels of ideological conflict, additional days might also have no marginal benefit (II). The benefit of additional time instead would be predicted to affect cabinets with medium‐to‐high levels of intra‐coalition conflict (III). At the other extreme, we make no claim that an infinite number of days of bargaining would produce an infinite amount of reforms on conflictual cabinets. There comes a point at which the marginal benefit of further negotiations diminishes (perhaps to zero) (IV). In such situations, the recommended model would thus be quadratic in nature (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Golder and Milton2012, p. 670). As such, in our interactive models, we include a squared term on the number of days in the successful bargaining round. Positing these specific locations for significant and insignificant marginal effects solves the ‘multiple comparison problem’ and false positive rates that might be associated with introducing conditional relationship between variables (Esarey & Sumner, Reference Esarey and Sumner2018, p. 1146).

In our regression output table, we use incident rate ratios, which can be interpreted as the per cent increase in counts when an independent variable increases by one scale step. As such, coefficients greater than 1 indicate a greater number of reforms, while coefficients smaller than 1 indicate fewer reforms. For hypothesis 1 to be supported, we are looking to see a coefficient greater than one and statistically significant. For hypothesis 2 to be supported, we are looking to see a coefficient greater than one and statistically significant on the interaction term.

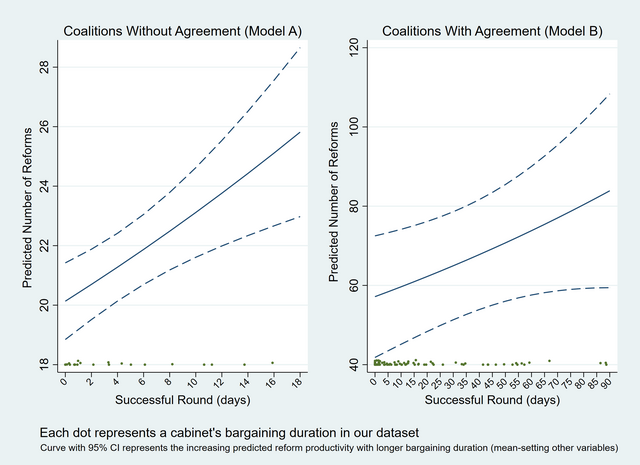

We analyse each of our hypotheses in turn predicting the count of reforms per cabinet. We have argued that the length of time for a successful bargaining round should influence reform productivity, whether or not a cabinet had a formal agreement. In model A we analyse the effect of bargaining time on cabinets without a coalition agreement, and in model B we analyse only those with such an agreement. The length of time in a successful bargaining round is significant in both models, and an incident rate ratio above 1 indicates a greater amount of productivity for each additional day. In cases without an agreement, we can see that for each additional day of bargaining, one can expect 1.4 per cent more reforms. For those with an agreement, each day of bargaining produces 0.4 per cent more reforms. While previous research has shown that coalitions with agreements tend to produce a greater number of reforms (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Angelova, Bäck and Müller2023), one can see that bargaining time itself seems to be more valuable per day for those that lack an agreement. These findings are visualized in Figure 2, illustrating predicted levels of reform productivity over the range of the number of days spent bargaining (model A and model B).

Figure 2. Predicted number of reforms for coalitions with and without an agreement.

The average number of reforms for coalitions without agreements is 23. Judging by the 95 per cent confidence interval of such a prediction, the left graph suggests that should a government form without an agreement, one would predict that it might not reach this level of productivity unless a week is spent in bargaining with its coalition partners. The average number of reforms for coalitions with an agreement is 57. Judging by the 95 per cent confidence interval of such a prediction, the right graph suggests that unless coalitions spend at least more than a month negotiating, they might not be able to be more productive than average.

There are some other results to note in these models (see Table 1). For cabinets without an agreement, a longer total formation period also would predict a more productive cabinet. This is holding constant the length of the successful round, meaning that time spent in negotiations before the official bargaining of the government formed aids in productivity. This supports our argument that information sharing beyond bargaining rounds that were successfully concluded by government formation aids in producing subsequent reforms, perhaps learning what opposition parties might be supportive of, or which policy instruments are feasible. This reasoning is also supported by the number of bargaining rounds variable being significant and positive for cabinets with an agreement. Interpreting the coefficient suggests that for each inconclusive bargaining round, one can expect 18 per cent more reforms of the subsequent cabinet.

Model C is a pooled model of all 104 coalitions in the sample. Remaining noteworthy is the statistical significance of our key variable of the length of time that a successful bargaining round takes; second, the number of previous bargaining rounds also remains significant. Also, in the online Appendix, we include models that control for the presence of a pre‐electoral agreement. These coalition governments make about 25 per cent more reforms; however, many of these cases do not receive the productivity benefits of bargaining time since over 60 per cent of these cases technically have no bargaining time. This is suggestive of two routes towards reform productivity: a pre‐electoral agreement or a longer bargaining duration.

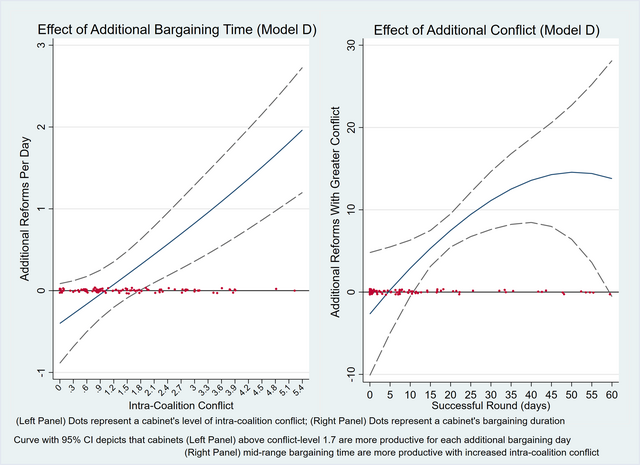

Finally, we estimate whether successful bargaining time has an impact on mitigating the potential negative effects of coalition conflict. We examine this in Model D in Table 1 and remind our readers that ‘The statistical significance of a multiplicative interaction term is seen as neither necessary nor sufficient for determining whether x has an important or statistically distinguishable relationship with y at a particular value of z’ (Esarey & Sumner, Reference Esarey and Sumner2018, p. 1145). Though not a sufficient condition, we do instruct the reader to note that the interaction between intra‐coalition conflict and bargaining days is correctly signed and statistically significant. The quadratic term is also correctly signed, suggesting that the productivity gains associated with increasing bargaining time decrease at some point. To minimize our potential false positive rate, we present marginal effects plots, but then also specifically examine the several predicted marginal effects at the extremes as posited earlier (p. 1159). Such a plot can also aid us in determining what is the range of days that results in more reforms for conflictual cabinets. As such, we graph these marginal effects in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Additional reforms predicted by the interaction of conflict and bargaining days.

We posited marginal relationships of our conditional variables at each of the extreme positions as suggested by Berry et al. (Reference Berry, Golder and Milton2012, p. 258). Examining first the left plot of Figure 3, we predicted that the benefits of additional bargaining time would affect cabinets with mid‐to‐high levels of intra‐coalition conflict (III), while at low levels of conflict, this additional bargaining time might not automatically produce productivity gains (II). We can see that for cabinets with less than the mean of 1.5 value of conflict, we cannot make a prediction on the direction of impact of additional bargaining days, as the marginal effects plot demonstrates that the predicted effect is indistinguishable from zero. For cabinets having a greater than 1.8 value of conflict, however, we can note that having one additional bargaining day would likely result in a greater number of socio‐economic reforms, with the most conflictual cabinets in our sample perhaps benefiting with two additional reforms per additional day of bargaining. Take, for example, a cabinet with a 1.8‐value of conflict. With minimal levels of bargaining, this cabinet would be expected to produce 47 reforms, while a cabinet with 10 days of bargaining would be expected to produce 50 reforms. While a cabinet with 1.8 value of conflict would benefit with three more reforms, a cabinet with double the conflict (3.6) would benefit with an expected additional 13 reforms. With minimal bargaining, this more conflictual cabinet would be predicted to produce 43 reformsFootnote 8 while with 10 days of bargaining, this cabinet would be predicted to produce 56 reforms.

Turning to the right plot of Figure 3, we predicted that having a low number of days would not be sufficient to benefit from the gains of negotiation (I). Instead, it would appear that conflictual cabinets would need at least 10 days before any productivity gains could be realized. Yet additional days do not always lead to an increased number of reforms produced. After about 2 months of bargaining,Footnote 9 there is no longer a statistically significant positive effect on additional days (IV). One can then suspect that if ideological differences cannot be mended after 2 months, then some other mechanism besides additional time would be needed to increase the productivity of these cabinets.

We run a series of robustness checks which are presented in the online Appendix (see Appendix B, Tables 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, 1e, 1f, 1g, 1h, and 1i), including additional controls for coalition agreements, economic controls, lagged dependent variables, fixed effects, institutional veto players and potential confounders. The Appendix documents how effect sizes of our key independent variables alter with each of these additional controls; none of these results lead us to doubt the robustness of the findings presented in the main document.

In fact, when the additional economic controls, lagged dependent variable and country‐fixed effects are all included in a model or in the model with confounders, the squared term becomes statistically significant at the 0.05 level and in several models is significant at the 0.1 level. This does not affect the significance or the substance of our findings, as these simply indicate that there is no marginal gain in productivity at the most extreme values for bargaining time. We also split the sample into those cabinets that formed after an election (1h) or between elections (1g). For both, more bargaining time is predicted to result in a greater number of reforms. The effect is stronger for those that form between elections (with bargaining days ranging from zero to 68). Alternatively, the conditioning effect of more bargaining time on ideological disagreement is only detectable for cabinets that formed post‐election (1g). Finally, we include a table (1i) with analyses where we control for the effective number of parliamentary parties and parliamentary seat share of extreme parties, which both create a more complex bargaining and policy‐making environment and could thus be a potentially confounding variable, as they have been shown to have an impact on bargaining time (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Hellström, Lindvall and Teorell2023) and could also affect legislative productivity. The effect of our key variable remains statistically significant and appropriately signed in all models.Footnote 10

Conclusions

Coalition governments team up political parties with different, and sometimes conflicting policy preferences. These parties also compete in elections and over government offices. Theoretically, this should result in governments that are politically unstable, which find it hard to make decisions. Yet, this bleak picture of governing with coalitions falls far short when examined with empirical data. Coalitions can also be stable, long‐living and policy‐productive. It is almost trivial to expect that greater preference compatibility between the coalition parties is likely to produce such effects. Instead, we have argued that negotiation before a coalition government forms and takes office can mitigate the unproductive aspects of coalition governance. In this paper, we have investigated the role that bargaining time has on the subsequent reform productivity of coalition governments.

We have argued that longer negation periods will increase reform productivity of cabinets and should help mitigate the negative effects of intra‐cabinet heterogeneity. We have tested these expectations using original data on over 5000 reform measures introduced by coalition governments in 10 Western European countries over a 35‐year period. We find that bargaining duration has considerable positive effects on a coalition's reform productivity. In general, we predict a 10 per cent increase in economic reform productivity of governments comparing those with negligible time spent bargaining to those spending the typical 2‐week period, and even greater productivity for those that go beyond what would be typical. Furthermore, bargaining duration seems to mitigate the negative consequences of intra‐coalition ideological conflict. Collectively, these results underline the value that coalition negotiation time, and the related inter‐party interactions, have for coalition governments’ reform productivity. Coalitions are not doomed to fail in making socio‐economic reforms and coalition bargaining is not ‘wasted time’. Coalition negotiations do matter for the policy‐making process. In particular, they help mitigate one of the central risks associated with coalition governments – policy stalemate.

These results are in line with some previous case study research, showing that longer bargaining periods do not always come with negative consequences. For example, analysing the case of Belgium after the 2010 election, Albalate and Bel (Reference Albalate and Bel2020) show that the Belgian economy did not suffer an economic toll from the record‐long government formation process taking over 500 days – instead, gross domestic product per capita growth was higher than would otherwise have been expected. Our results on policy‐making productivity could help us understand such positive effects of longer negotiation periods found in previous research.

The data on reform productivity used here were measures of an economic nature, and it is unclear whether foreign policy or cultural reforms would follow similar patterns, as perhaps reforms of this nature are more difficult to discuss before the commencement of a term. Theoretically, one could argue that the trust built between parties could be helpful, though these types of issues might be more contingent on circumstances or events occurring during the term, where previous coordinating capital might be of lesser value.

Also, as of today our understanding of what happens during the bargaining process is based largely on qualitative evidence. Unravelling such processes more deeply and coming up with indicators for quantitative analyses also appears an important research venue, such as identifying how much of the bargaining time is devoted towards policy, discipline, cabinet posts, etc. Future research might investigate whether different levels of overlap between coalition negotiators and ministers in the new cabinet affect reform productivity, with the expectation that the cabinet will be more productive, the more negotiators become ministers.

Another potential question for future research relates to the amount and quality of publicity the bargaining process receives (Spörer‐Wagner & Marcinkowski, Reference Spörer‐Wagner and Marcinkowski2010). While the literature on political negotiations generally considers privacy a condition for narrowing gaps between positions and reaching agreement (Martin, Reference Martin, Mansbridge and Martin2013), full privacy of such negotiations seems unrealistic in a media democracy. At the same time, the politics of informing the public about the negotiations might be played in a concerted manner by the parties or in a competitive mode, with each party releasing information strategically to support its bargaining position.

As mentioned earlier, we have here focused on the challenges inherent in governing in coalitions, but these are clearly not the only constraints on reform productivity. For instance, institutionally strong second chambers that are politically incongruent with the first chamber, and constitutional courts, and the presence of such or other institutional veto players (Tsebelis, Reference Tsebelis2002) are likely to depress a government's reform productivity. We suggest that such political constraints would be worth looking into for future research as it appears that greater constraints result in greater reform productivity, suggestive of logrolling processes at play.

Our research may also contribute to our understanding of how the government formation process influences cabinet stability. As mentioned, some scholars have suggested that longer periods of bargaining suggest a complex partisan environment that will lead to earlier dissolution of cabinets (see King et al., Reference King, Alt, Burns and Laver1990), whereas others have argued that longer coalition bargaining periods imply greater attention to detail in the negotiations, resulting in a higher level of cabinet stability (see, e.g., Warwick, Reference Warwick1994). Empirically, Saalfeld (Reference Saalfeld, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008) shows, analysing cabinets over the post‐war period in Western Europe, that the longer the coalition negotiations lasted at the formation stage, the lower the risk of early elections. We suggest that our research helps make sense of such findings since we show that a longer bargaining process results in a higher degree of reform productivity, which could strengthen a cabinet's chances of withstanding, for example, economic crises, which may otherwise have resulted in early termination of a cabinet. Future research could benefit from making use of our data on reform measures to evaluate a theoretical account focusing on how longer bargaining periods result in fewer government crises due to a high policy‐making capacity.

All in all, our results have important implications for our understanding of the functioning of parliamentary democracy, suggesting that, even though extended negotiations between parties forming coalition cabinets may come with some temporary uncertainty for financial markets, cabinets that have gone through such long bargaining processes may in fact be more productive in terms of making economic reforms during their time in office, since they are likely to have paved the way for efficient cooperation between the parties.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the SFB 884 ‘Political Economy of Reforms’ at the University of Mannheim and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, grants I 1607‐G11 and I 3793‐G27) for financial support. Hanna Bäck acknowledges financial support from the Swedish Research Council (2020‐01396). The authors also wish to thank the reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix A. Dependent Variable Construction

Table A1: Policy measures coded

Figure A1. Number of reforms per year over time and country

Appendix B. Supplementary Analyses