Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a complex condition characterised by metabolic irregularities such as abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, abnormal lipid levels, decreased HDL cholesterol and elevated blood glucose(Reference Saklayen1). Diagnosis is confirmed when at least three of these criteria are present concurrently(Reference Alberti and Zimmet2). MetS significantly increases the risk of chronic kidney failure, stroke, diabetes and CVD, leading to higher mortality rates(Reference Johnson, Armstrong and Campbell3,Reference Huang4) . This condition poses a significant risk for developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular issues, as it is marked by a combination of factors such as insulin resistance. Globally, MetS is a prevalent health concern. In the USA, its prevalence increased from 32·5 % in 2011–2012 to 36·9 % in 2015–2016(Reference Ranasinghe, Mathangasinghe and Jayawardena5,Reference Cuevas, Alvarez and Carrasco6) . Similarly, the Asia-Pacific region has seen rising trends. In Korea, studies have documented an increase in MetS prevalence from 24·9 % in 1998 to 31·3 % in 2007(Reference Lim, Shin and Song7,Reference Tran, Jeong and Oh8) . Specifically, the prevalence among Korean men rose from 25·8 % to 40·0 % between 2001 and 2020, while it decreased among women from 28·2 % to 26·2 %(Reference Park, Shin and Després9). These trends suggest gender-specific differences in MetS components and lifestyle changes. Sex and gender differences play a critical role in obesity and metabolic health, with men being more prone to visceral fat accumulation and earlier onset of cardiometabolic diseases, whereas women’s metabolic risk is shaped by hormonal fluctuations, reproductive factors and sociocultural influences on dietary preferences, such as food choices and beverage consumption patterns(Reference Kim, Kim and Sung10).

Soda consumption has increased globally, and it is estimated that sugary drinks can raise daily caloric intake by up to 50 %(Reference Duffey and Popkin11,Reference Popkin12) . In 2013, South Koreans consumed an average of 72·1 g of sugar daily, with a significant portion from beverages(Reference Lee, Kwon and Yon13). Between 2018 and 2022, average soda consumption in Korea increased from 42·8 g to 45·8 g per day(14). There are several studies that have reported adverse associations between high sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) intake, MetS and some of its components(Reference Shin, Kim and Ha15–Reference Chun, Choi and Chang17). However, there is a lack of studies that examine the association of soda consumption with MetS and its components, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, in Korean population. The pandemic has complicated the landscape, with potential cardiovascular complications and increased risk factors associated with MetS(Reference Cruz Neto, Frota Cavalcante and de Carvalho Félix18,Reference Dissanayake19) . Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that the relationship between SSB, including soda, and metabolic risk factors may differ by sex, with stronger associations often observed in women than in men. This highlights the importance of investigating sex-specific differences to identify vulnerable populations and inform tailored public health strategies(Reference Shin, Kim and Ha15).

Therefore, we aimed to assess the impact of soda consumption on MetS and its components in the general Korean adult population, stratified by sex, using data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). In addition, we conducted a stratified analysis by the COVID-19 periods to compare whether the association between soda consumption and MetS differs before and after the COVID pandemic.

Materials and methods

Study population

Our study used data derived from the 7th period (2017–2018) and 8th period (2019–2021) of the KNHANES, administered by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under the auspices of the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare. The KNHANES employed a sophisticated sampling design, incorporating multistage, stratified, clustered and probability-based methodologies to capture a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. This survey consists of three principal components: a health examination, a health interview and a nutrition survey. Detailed descriptions of KNHANES methodologies have been earlier documented in literature(Reference Kweon, Kim and Jang20). Data were gathered from 38 678 participants in 2017 (n 8127), 2018 (n 7992), 2019 (n 8110), 2020 (n 7359) and 2021 (n 7090). Among them, 31 365 participants completed the health examination, health interview and nutrition survey. From this pool, participants were sequentially excluded based on the following criteria: individuals aged < 19 or ≥ 65 years (n 13 164); those self-reporting a history of myocardial infarction, stroke or cancer, or taking medications for hypertension, dyslipidemia or diabetes (n 3981); lactating or pregnant women (n 188); individuals with extreme total energy intakes (n 274); subjects who fasted less than 8 h (n 522); participants with missing data on MetS (n 185), consisting of a total of 13 051 participants (5512 men, 7539 women). The flow chart in Figure 1 illustrates the inclusion criteria for the final eligible study population. Prior to the survey, each participant was provided with informed consent, and the KNHANES dataset received formal ethics approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on various dates in 2018 (2018-01-03-C-A, 2018-01-03-P-A, 2018-01-03-2C-A, 2018-01-03-3C-A).

Figure 1. Study participants were included in the study after the exclusion criteria. Note: The figure shows the selection process of the study population from the initial sample in the KNHANES 2017–2021 dataset. Participants were first filtered by age (excluding those under 19 or over 65 years). Further exclusions were made for individuals with a history of stroke, myocardial infarction or cancer, those taking medications for dyslipidemia, hypertension or diabetes, pregnant or lactating women, individuals with extreme total energy intakes (< 500 or > 5000 kcal/d), those who fasted for less than 8 h and those with missing MetS data. The final eligible sample consisted of 13 051 adults aged 19–64 years, divided into 5512 men and 7539 women.

Assessment of soda consumption

The intake of soda was evaluated using a 24-h dietary recall technique, following the coding guidelines of the KNHANES(21). We used the intake of sustenance classification, specifically the food code (NF-INTK). A total of thirty-five different types of carbonated beverages were categorised, including soda, lemonade, orange soda, grape soda, cola, tonic water, fruit-flavoured sodas and other carbonated drinks, excluding artificially sweetened or diet versions. In this study, the adult population was categorised into five groups based on their soda consumption levels. These five groups include one group for non-drinkers and four quartiles for soda consumers. The quartiles for soda consumption were defined as follows. For the overall adult population, the quartiles were defined as: Q1 < 53 g/d, Q2 53–< 210 g/d, Q3 210–< 373 g/d and Q4 ≥ 373 g/d. For men, the quartiles were: Q1 < 125 g/d, Q2 125–< 258 g/d, Q3 258–< 420 g/d and Q4 ≥ 420 g/d. For women, the quartiles were: Q1 < 42 g/d, Q2 42–< 189 g/d, Q3 189–< 315 g/d and Q4 ≥ 315 g/d.

Assessment of metabolic syndrome

In order for a diagnosis of MetS to be made, a person must exhibit at least three of the following criteria (1) abdominal obesity (waist circumference ≥ 90 cm for men and ≥ 85 cm for women); (2) elevated blood pressure (systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 85 mmHg); (3) low HDL-cholesterol (fasting HDL-cholesterol < 40 mg/dl for men and < 50 mg/dl for women); (4) hypertriglyceridaemia (fasting triglyceride ≥ 150 mg/dl) and (5) hyperglycaemia (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dl). The researchers meticulously measured the waist circumferences of the participants, noting the measurements to the nearest 0·1 cm. Blood pressure readings were then taken after a brief 5-min rest in a seated position, with three readings recorded at 30-s intervals. The average of the second and third readings of both systolic and diastolic pressure was utilised for further examination. Fasting blood samples were collected after ≥ 8 h of fasting to measure HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides and fasting plasma glucose. Lipid profiles were analysed using the enzymatic method with an automatic biochemical analyser (Hitachi 7600-210 in 2017–2018; Labospect 008AS in 2019–2021). HDL-cholesterol was measured using a homogenous enzymatic colourimetric method in 2017–2018 and an enzymatic method in 2019–2021. Triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol and fasting plasma glucose levels were assessed in accordance with the protocols outlined by the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III(22) and the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity criteria(Reference Kim, Kang and Kang23).

Confounding variables

Information regarding demographic and lifestyle variables, encompassing age, diet quality, physical activity levels and alcohol consumption, was gathered through personal interviews or self-administered questionnaires. Educational attainment was divided into three categories: ‘middle school or below’, ‘high school’ and ‘college or higher’. Alcohol consumption was stratified into the following categories: never/rarely, 1–4 times per month and ≥ 2 times per week. We categorised physical activity into high and low levels. High physical activity was defined as participating in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity activity per week, at least 75 min of vigorous-intensity activity per week, or a combination of both moderate and vigorous activities totalling at least 150 min per week (with 1 min of vigorous activity equating to 2 min of moderate activity). Diet quality was assessed as either high or low using a revised version of the Diet Quality Index for Koreans (DQI-K). The evaluation considered eight factors, including protein, cholesterol, whole grains, fruits, vegetables, sodium and the proportion of energy derived from fat and saturated fat. Each factor was allocated DQI-K points according to predefined thresholds, such as the Korean Dietary Reference Intakes. The total DQI-K score for each participant ranged from 0 to 9. A DQI-K score of 0–4 represented high diet quality, while a score of 5–9 represented low diet quality(Reference Shim, Lee and Moon24,Reference Lim, Lee and Shin25) . In addition, the total amount of energy consumed was meticulously calculated and examined as a continuous factor.

Statistical analysis

We classified individuals into five groups based on soda consumption: non-drinkers, and four quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4) for soda consumers, for the total adult population. We utilised the PROC SURVEYREG and PROC SURVEYFREQ procedures to calculate the mean and prevalence of demographic and lifestyle variables using SAS 9.4 software. Multivariable-adjusted OR and 95 % CI for MetS according to soda consumption were determined with the PROC SURVEYLOGIST procedure. We conducted a stratified analysis based on the COVID-19 pandemic, dividing data into pre-COVID-19 (2017–2019) and post-COVID-19 (2020–2021) periods. The interaction between soda consumption and the COVID-19 periods in relation to MetS was analysed using PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 software. A two-tailed P-value of less than 0·05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of Korean adults by soda consumption. Compared with people in the lowest group (non-drinkers), those in the highest group (Q4) of soda consumption were more likely to be younger. For men, there was a significant association between educational attainment and soda consumption. Individuals in the highest consumption category (Q4) were less likely to have attained a college education or higher. Both men and women in the high soda consumption group tended to consume less alcohol compared with those who did not consume soda. Additionally, a higher prevalence of current smoking was observed among women in this group. Physical activity levels did not show significant differences across the various soda consumption groups. Diet quality, evaluated through the DQI-K, indicated that individuals with high soda consumption had higher DQI-K scores, reflecting poorer dietary quality. These individuals also had higher total energy intakes, with a larger proportion of their caloric intake derived from carbohydrates and lower proportions from proteins.

Table 1. Characteristics of study population according to soda consumption in Korean adults aged 19–64 years*

DQI-K, a modified diet quality index for Koreans; *Values are presented as means (standard errors) for continuous variables, and number and weighted % for categorical variables; †High physical activity was defined as at least 75 min of vigorous activity per week, at least 150 min of moderate activity per week or at least 150 min of a combination of vigorous and moderate activity per week; ‡Adjusted for age (continuous), education (≤ middle school, high school, or ≥ college), DQI-K (high diet quality, low diet quality), alcohol consumption (never/rarely, 1–4/month, or ≥ 2/week), smoking status (non-smoker, former smoker or current smoker), physical activity (low or high) and total energy intake (continuous). § P-values obtained from the χ2 test for categorical variables and from PROC SURVEYREG procedure for continuous variables.

DQI-K, Diet Quality Index for Koreans.

Soda consumption and metabolic syndrome

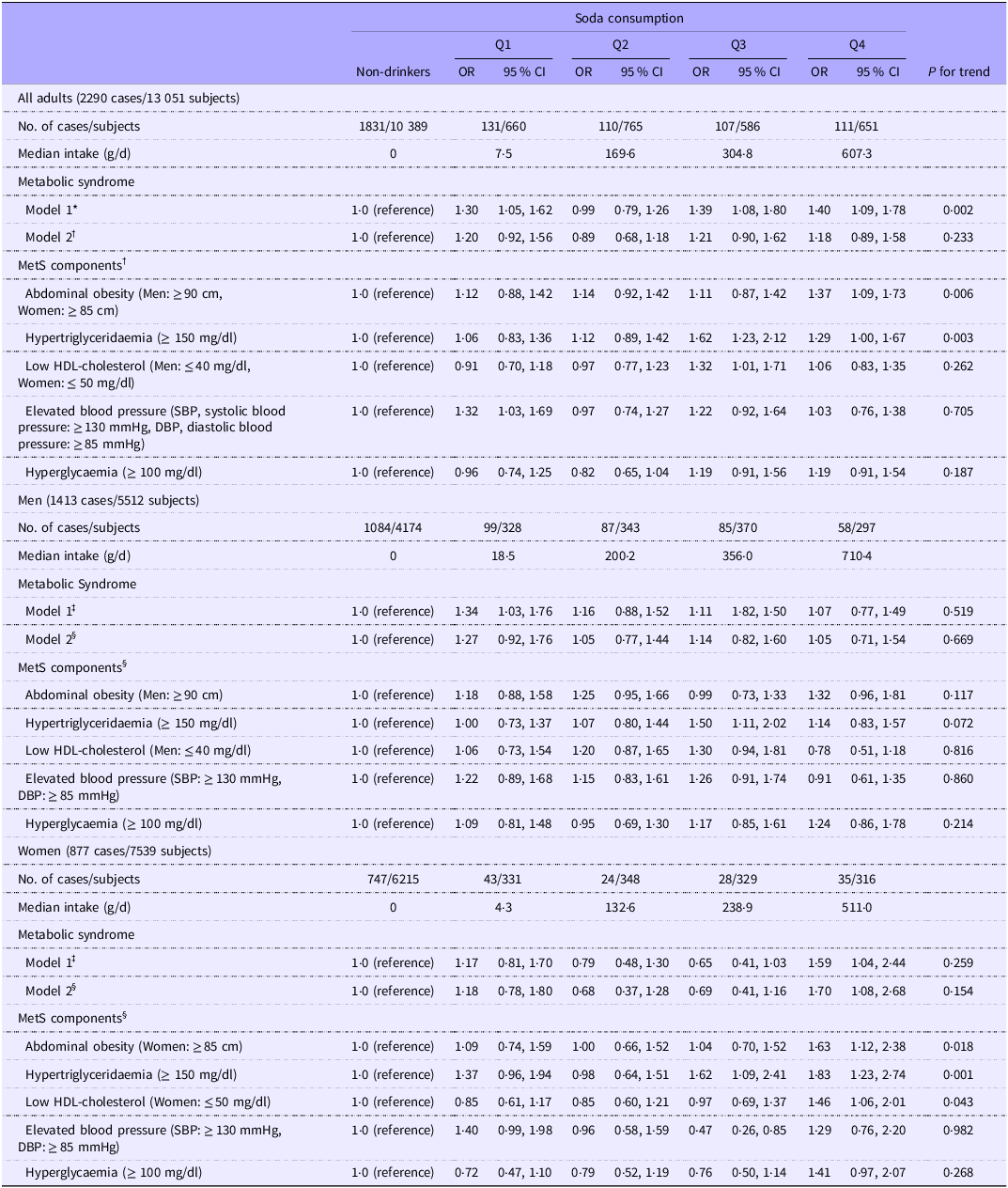

Table 2 shows the results of multivariable logistic regression analysis examining the association between soda consumption and MetS and its components. After adjusting for multiple covariates, there was no significant association between soda consumption and MetS overall. For the components of MetS, however, adults in the highest quartile of soda consumption (≥ 373 g/d) had 37 % higher odds of abdominal obesity compared with non-drinkers (OR = 1·37, 95 % CI: 1·09, 1·73; P-trend = 0·006). Similarly, higher soda consumption was associated with an increased odd of hypertriglyceridaemia, with individuals in Q3 (210–< 373 g/d) and Q4 (≥ 373 g/d) having 62 % (OR = 1·62, 95 % CI: 1·23, 2·12) and 29 % higher odds (OR = 1·29, 95 % CI: 1·00, 1·67), respectively, compared with non-drinkers (P-trend = 0·003).

Table 2. Multivariable adjusted OR for metabolic syndrome according to soda consumption and types in Korean adults aged 19–64 years

*Adjusted for age (continuous) and sex; †Adjusted for age (continuous), sex, education (≤ middle school, high school, or ≥ college), KDQI (high diet quality, low diet quality), alcohol consumption (never/rarely, 1–4/month, or ≥ 2/week), smoking status (non-smoker, former smoker or current smoker), physical activity (low or high) and total energy intake (continuous); ‡Adjusted for age (continuous); §Adjusted for age (continuous), education (≤ middle school, high school, or ≥ college), DQI-K (high diet quality, low diet quality), alcohol consumption (never/rarely, 1–4/month, or ≥ 2/week), smoking status (non-smoker, former smoker or current smoker), physical activity (low or high) and total energy intake (continuous).

MetS, metabolic syndrome.

When analysed by gender, women in the highest quartile of soda consumption (≥ 315 g/d) had 70 % higher odds of having MetS compared with non-drinkers (OR = 1·70, 95 % CI: 1·08, 2·68). Additionally, women in Q4 exhibited 63 % higher odds of abdominal obesity (OR = 1·63, 95 % CI: 1·12, 2·38, P-trend = 0·018) and 46 % higher odds of low HDL cholesterol (OR = 1·46, 95 % CI: 1·06, 2·01, P-trend = 0·043). For hypertriglyceridaemia, soda consumption in Q3 (189–< 315 g/d) and Q4 (≥ 315 g/d) was associated with 62 % (OR = 1·62, 95 % CI: 1·09, 2·41) and 83 % (OR = 1·83, 95 % CI: 1·23, 2·74) higher odds (P-trend = 0·001). Notably, these associations were not observed in men.

Further analysis considered the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the relationship between soda consumption and MetS. Table 3 presents these findings. During the post-pandemic period, adults in the highest quartile of soda consumption (≥ 416 g/d) showed a significantly higher odds of MetS compared with non-drinkers (OR = 1·56, 95 % CI: 1·04, 2·34), while the association was not significant in the pre-pandemic period (P–interaction = 0·031). The observed interaction with COVID-19 pandemic, however, was not significant when analysed separately by gender.

Table 3. Multivariable adjusted OR for metabolic syndrome according to soda consumption by pre and post COVID-19 pandemic in Korean adults aged 19–64 years

*Adjusted for covariates including, age (continuous), sex, education (≤ middle school, high school, or ≥ college), KDQI (high diet quality, low diet quality), alcohol consumption (never/rarely, 1–4/month or ≥ 2/week), smoking status (non-smoker, former smoker or current smoker), physical activity (low or high) and total energy intake (continuous); †Adjusted for covariates including, age (continuous), education (≤ middle school, high school or ≥ college), DQI-K (high diet quality, low diet quality), alcohol consumption (never/rarely, 1–4/month, or ≥ 2/week), smoking status (non-smoker, former smoker or current smoker), physical activity (low or high) and total energy intake (continuous); ‡Participants were classified based on whether their data were collected before or after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Discussion

Our study shows a significant association between soda consumption and the risk of MetS, particularly among women. Women in the highest quartile of soda consumption had a 70 % higher risk of MetS compared with non-drinkers, even after adjusting for potential confounders. Additionally, high soda consumption in women was significantly associated with specific MetS components, including abdominal obesity, low HDL-cholesterol and hypertriglyceridaemia. In contrast, no significant associations were observed between soda consumption and MetS or its components in men. It is important to note that men consumed larger amounts of soda overall, as reflected in the higher quartile cut-off values compared with women. Despite this higher level of consumption in men, the significant association with MetS was observed only among women. This finding suggests that women may be more susceptible to the adverse metabolic effects of soda consumption.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies that have highlighted the adverse metabolic effects of soda consumption, particularly among women. For example, Shin et al. reported a 61 % higher risk of MetS prevalence in Korean women aged 35–65 years, consuming ≥ 1 serving of SSB per day compared with women in the non-SSB-drinker group(Reference Shin, Kim and Ha15). Similarly, Kang et al. found that Korean women aged 40–69 consuming ≥ 4 servings per week of soft drinks had an 82 % higher risk of MetS prevalence compared with non-drinkers(Reference Kang and Kim26). These studies, along with findings by An et al. (Reference An, Kim and Seo27), consistently demonstrate gender specific risk patterns, supporting our results that adult women may be more vulnerable to the metabolic risks associated with soda consumption compared with men. Sex differences likely reflect complex interactions between hormones and fructose metabolism. Oestrogen influences the expression and activity of fructose-metabolising enzymes, including ketohexokinase-C, and lipogenic transcription factors such as carbohydrate response element-binding protein, creating metabolic environments where fructose preferentially undergoes de novo lipogenesis(Reference Softic, Gupta and Wang28,Reference Mirtschink, Jang and Arany29) . Under chronic fructose exposure, ketohexokinase-C activation appears to overwhelm oestrogen’s protective effects on endoplasmic reticulum stress pathways, with this relationship being particularly pronounced in females(Reference Park, Helsley and Fadhul30). Women’s higher subcutaneous adipose tissue facilitates visceral fat redistribution under chronic fructose load, creating a ‘double-hit’ metabolic burden through both increased hepatic lipogenesis and enhanced peripheral fat storage(Reference Kovačević, Brkljačić and Vojnović Milutinović31–Reference Chang, Varghese and Singer33). This interplay between hormonal status and fructose metabolism may explain why women, despite consuming less soda overall, demonstrate stronger associations with MetS risk.

Beyond biological mechanisms, psychosocial factors may contribute to the sex-specific associations observed in this study. Women demonstrate higher susceptibility to stress-induced emotional eating behaviours, particularly involving increased consumption of high-energy, palatable foods, including soda(Reference Thompson and Romeo34,Reference Finch and Tomiyama35) . The COVID-19 pandemic intensified psychological distress, with women experiencing significantly higher levels of anxiety, depression and emotional eating compared with men(Reference Prowse, Sherratt and Abizaid36,Reference Güner and Aydın37) . Previous studies have shown that psychological distress is directly associated with increased intake of SSB among women(Reference Grieger, Habibi and O’Reilly38), indicating that unmeasured psychological variables such as anxiety may have influenced dietary patterns during this period. The heightened psychological burden experienced by women during the pandemic, combined with their greater tendency to use food as a coping mechanism, may contribute to understanding the overall sex-specific vulnerability to soda-related metabolic risks observed in our study. These findings highlight the importance of considering psychosocial determinants in future longitudinal research examining dietary behaviours and metabolic health outcomes, particularly over extended pandemic periods.

Excessive soda consumption has been strongly linked to MetS risk through various mechanisms. Soda, sweetened with high-fructose corn syrup, promotes hepatic de novo lipogenesis, increasing plasma triglycerides and contributing to metabolic disturbances(Reference David39–Reference Giacchetti, Sechi and Griffin43). Frequent soda consumers also tend to have unbalanced dietary patterns, such as higher calorie and fat intake with lower dietary fibre, which exacerbate these effects(Reference Duffey and Popkin44,Reference Park, Kim and Kang45) . These metabolic disruptions provide a biological basis for the observed associations between soda consumption and MetS risk in our study. The Framingham Heart Study found a significant association between SSB consumption and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, which is consistent with our findings of soda’s association with MetS risk and its components, such as abdominal obesity, low HDL cholesterol and hypertriglyceridaemia(Reference Park, Yiannakou and Petersen46). Another study conducted in Taiwan showed significant associations between higher SSB consumption and increased MetS, including waist circumference, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, both in males and females. However, an important sex difference was observed with SSB consumption significantly associated with elevated blood pressure and fasting blood glucose only in females. This discrepancy may be partially explained by the influence of sex hormones, particularly oestrogen, on lipid metabolism and blood pressure regulation. Oestrogen is known to positively modulate the renin-angiotensin system, promote fat transport and increase triglyceride and lipoprotein levels. These hormonal effects could render women more sensitive to the metabolic risks associated with SSB consumption compared with men.(Reference Kuo, Chen and Chan47). Together, these studies emphasise the need for global public health strategies to mitigate the adverse metabolic effects of soda consumption.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, soda consumption increased, with individuals in the highest quartile of intake showing a 56 % higher risk of MetS compared with non-drinkers. The COVID-19 pandemic seems to further impact soda consumption and MetS prevalence. Our study observed an increased proportion of adults consuming high amounts of soda and sugar during the pandemic, with a corresponding rise in MetS prevalence. These findings underscore the need for public health strategies to mitigate the adverse metabolic effects of soda consumption, exacerbated by the pandemic(Reference Oh, Park and Park48,Reference Kim and Kye49) .

This study, despite utilising large-scale KNHANES data, has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional design prevents establishing causal relationships between soda intake and MetS. Additionally, the reliance on 24-h recall data, reflecting only the previous day’s intake, may not fully capture habitual dietary patterns. Furthermore, our study did not measure psychological variables such as anxiety, depression or stress levels, which may have influenced dietary behaviours during the pandemic period and contributed to the sex-specific associations observed. However, this study is the first to explore the association between soda consumption and MetS during the COVID-19 period in Korean adults, distinguishing soda from total SSB. Moreover, the large, nationally representative sample enhances generalizability, and the consistent use of 24-h recall data from 2017 to 2021 ensures accuracy. Therefore, this detailed methodology offers valuable insights into the relationship between soda intake and MetS, especially in the context of pandemic-related dietary changes.

In conclusion, this study reveals a significant association between soda consumption and an increased risk of MetS, particularly among Korean women, with findings observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, a period when both soda intake and MetS prevalence rose. While these findings provide valuable insights for informing public health policies and dietary recommendations, further longitudinal research is crucial to establish causal relationships and strengthen the evidence.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants and staff of seventh and eighth periods (2017–2021) of KNHANES for their valuable contributions.

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Korean government (grant number NRF–2021R1F1A1050847). The National Research Foundation of Korea had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decisions to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows – Conceptualisation, Y. J. and S. W.; formal analysis, S. W.; investigation, Y. J. and S. W.; data curation, Y. J. and S. W.; funding acquisition – Y. J.; writing – original draft preparation, S. W.; writing – review and editing, Y. J. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

There are no conflicts of interest.