Introduction

For several decades, debates about the nature and extent of the apparent decline in the global labor movement have evolved, driven by differing interpretations of observable trends. These debates have given rise to both optimistic views of a potential union revitalization (Bernaciak et al. Reference Bernaciak, Gumbrell-McCormick and Hyman2014; Frege and Kelly Reference Frege and Kelly2004; Murray Reference Murray2017; Senén and Haidar Reference Senén and Haidar2009; Voss and Sherman Reference Voss and Sherman2000) and pessimistic forecasts predicting a permanent decline linked to organizational, institutional, and market-related factors (Beaumont Reference Beaumont1987; Farber and Western Reference Farber and Western2001; Kollmeyer Reference Kollmeyer2021; Kuruvilla et al. Reference Kuruvilla, Das, Kwon and Kwon2002).

More recently, changes in labor relations driven by new technologies, along with the impacts of globalization and national labor market liberalization policies, have further intensified the pressure on unions in terms of their ability to influence and mobilize (Basualdo et al. Reference Basualdo, Letcher, Nassif, Barrera, Bosch, Copani, Peláez and Rojas2019; Martínez et al. Reference Martínez, Mustchin, Marino, Howcroft and Smith2021; Meyer Reference Meyer2019; Neto et al. Reference Neto, Afonso and Silva2019).

Despite these shifting realities and contrasting interpretations, measuring union power remains a challenging endeavor for scholars. A major limitation in academic approaches to union power is their reliance on broad indicators such as union density or collective bargaining coverage (Crouch Reference Crouch2017; Visser Reference Visser2006), which often fail to capture the nuances of unions’ mobilization capacity, internal strength, and capacity for collective action (Kelly Reference Kelly2015; Metten Reference Metten2021; Roos and Yu Reference Roos and Yu2023). This issue is particularly problematic in regions like Latin America, where access to systematic data varies significantly, and where unionism has developed unevenly across different sectors of society. As a result, standardized measures like union density provide only a partial and often insufficient basis for understanding the complexity of labor movements in the region.

The power resources approach (PRA) provides a more comprehensive framework for understanding union dynamics, as it moves beyond conventional indicators and adopts a multidimensional perspective (Schmalz et al. Reference Schmalz, Ludwig and Webster2018). However, the complexity of measuring these dimensions in a comparative framework has largely restricted its application to specific case studies, limiting broader analyses of union trajectories and contexts.

This research note introduces a methodology, grounded in the PRA, for empirically measuring and analyzing union power, enabling cross-national comparisons. Drawing on an original database constructed through narrative coding—covering ten dimensions of the labor movement across 17 Latin American countries between 1990 and 2020—we operationalize various union power resources and classify countries according to their distribution. This approach provides an empirical foundation for identifying and analyzing different patterns of unionism at the national level in Latin America. By systematically mapping these variations, this framework aims to enhance our understanding of unions’ roles in diverse socio-political contexts, providing insights into their capacities, strategies, and long-term influence on labor relations and policymaking.

The article is structured into four sections. The first provides a brief theoretical review that establishes the analytical framework and discusses the challenges of empirical measurement. The second introduces the database, detailing the methodology, variable operationalization, and validation strategy. The third applies this framework by examining the distribution and evolution of union power across Latin America and proposes a preliminary typology of unionism in the region based on these resources. Finally, the fourth section discusses the findings, reflecting on the strengths and limitations of the proposed approach.

The Power Resources Approach and its Shortcomings

Unions are organizations of workers whose primary goal is to collectively negotiate the sale of their members’ labor force, which encompasses various disputes over the distribution of social labor surplus and opens up possibilities for politicization (Anderson Reference Anderson and Martínez Heredia2010; Campusano et al. Reference Campusano, Gaudichaud, Osorio, Seguel and Urrutia2017; Edwards Reference Edwards1990; Hyman Reference Hyman1981; Medel et al. Reference Medel, Velásquez and Pérez2021; Santella Reference Santella2014). Consequently, to achieve their immediate or long-term objectives, unions must wield sufficient power to counteract the opposing party’s pursuit of profit maximization.

Unionism initially arose as a defensive mechanism for workers against the power imbalances between employers and employees in wage labor relations. Although initially persecuted and repressed by the State, unions gradually emerged as critical actors in modern societies, fulfilling roles that ranged from drafting workplace petitions to spearheading significant political transformation processes (van der Linden Reference van der Linden2019). This evolution of unionism drew the attention of various intellectuals who aimed to understand its potential and define its unique characteristics across different national contexts. The interest in unionism in Latin America has led to the creation of significant analytical and classificatory works. These works are based on criteria such as the type of affiliated worker, the movement’s relationship with the political structure, and its stages of development (Campero Reference Campero1989; Di Tella et al. Reference Di Tella, Brams, Reynaud and Touraine1967; Faletto Reference Faletto1966; Petras Reference Petras1973; Touraine and Pécaut Reference Touraine and Pécaut1966; Zapata Reference Zapata1982, Reference Zapata1993).

A practical challenge with many of the classification frameworks developed is their limited replicability—either because their design did not consider this purpose or because they do not comprehensively address the most critical dimensions of unionism. In this context, the power resources approach (PRA) presents an alternative that aims to overcome these drawbacks.

Initially, researchers developed the PRA to identify categories that typify the forms of collective action within social movements and to explain their scope and limitations (McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977). Its application to the analysis of the labor movement is a more recent development (Korpi Reference Korpi1985), gaining significant traction over the past few decades. This evolution has taken place against a historical backdrop of prolonged declines in unionization rates and a resulting decrease in the global prominence of this social actor, although with notable variations and contradictory trends in specific regions and countries (Bernaciak et al. Reference Bernaciak, Gumbrell-McCormick and Hyman2014; Crouch Reference Crouch2017; Espinosa Reference Espinosa1997; Frege and Kelly Reference Frege and Kelly2004; Lehndorff et al. Reference Lehndorff, Dribbusch and Thorsten2018; Zapata Reference Zapata1994).

The core principle of the PRA is that the collective organization of workers must mobilize its available resources to strengthen its capacity to achieve its objectives (Schmalz et al. Reference Schmalz, Ludwig and Webster2018). Three key considerations emerge from this perspective.

First, the ability to utilize power resources depends on the prior development of organizational capacities that enable unions to deploy them effectively. Second, power resources are not evenly distributed, as certain unions have greater access to specific resources due to the structural position of their members within the economy. Third, neither the availability of power resources nor the ability to mobilize them remains static. The conditions of unionism evolve over time, either actively through strategic action or passively in response to external changes.

Building on these insights, scholars distinguish between the capacity for collective action and the ability to mobilize resources from various sources (Pérez Ahumada Reference Pérez Ahumada2023; Rhomberg and Lopez Reference Rhomberg, Lopez and Leitz2021). This distinction underpins the classification of four major forms of union power. Associational power refers to the ability to organize and mobilize members collectively. Structural power relates to the capacity to leverage economic disruption within the labor market. Institutional power reflects unions’ ability to mobilize resources within the state and policymaking arenas. Societal power (also known as social power) captures unions’ capacity to build alliances and mobilize resources within civil society (Brookes Reference Brookes2018).

The following sections examine each of these power resources in greater depth and discuss key challenges in their empirical observation. Addressing these issues is essential to developing a robust measurement strategy.

Defining Union Power Resources

A clear definition of union power resources is essential for their meaningful classification and measurement. This process lays the groundwork for identifying the conditions that enable or constrain unions’ collective capacity across different contexts.

Associational power is often regarded as the foundational dimension within the power resources approach (PRA), as it stems directly from workers’ collective organization within unions and their capacity to develop and deploy repertoires of action (Wright Reference Wright2000, 962). By its nature, this form of power requires both the formulation and execution of strategies (Gumbrell-McCormick and Hyman Reference Gumbrell-McCormick and Hyman2013; Silver Reference Silver2005). As a result, associational power often serves as a “pivot” that integrates and activates other forms of union power. In other words, all other dimensions of union power rely, to some extent, on unions’ ability to mobilize their members, making associational power the foundation of effective collective action (Brookes Reference Brookes2018, 254–55).

A widely used indicator of associational power is union membership level and union density as a proportion of the total workforce. However, additional factors also shape this dimension, including the ability to mobilize members, levels of internal participation, organizational infrastructure, and strategic efficiency (Pérez Ahumada Reference Pérez Ahumada2023; Schmalz et al. Reference Schmalz, Ludwig and Webster2018). These associational resources operate across multiple scales, from the workplace level—through factory committees or union branches—to the national level. Given their foundational role in union activity, associational power is often present in the mobilization of other union power resources, making it analytically complex to distinguish from other dimensions in some contexts.

Structural power stems from the position workers hold within a specific productive structure (Wright Reference Wright2000), as it provides them with the objective ability to disrupt the production or distribution of goods and services by halting their own work and that of other workers connected in the production process. This type of power is intrinsic to unionism and linked to its strategic economic position (Womack Jr. Reference Womack2007). Some authors suggest that a second dimension of this power arises from the dynamics of supply and demand in the labor market, specifically how easily workers can be replaced at a given time (Silver Reference Silver2005, 26–27).

The extent to which unions can mobilize structural power varies according to the economic significance of their sector and the specific labor market conditions at a given moment. These factors shape unions’ disruptive potential. However, a strategic position alone does not guarantee the effective exercise of structural power. Its activation requires strong associational power, as even the mere threat of disruption can be a powerful tool in achieving union objectives without the need for direct action (Fox-Hodess and Santibáñez Reference Fox-Hodess and Santibáñez2020). In many cases, the potential for disruption itself is sufficient to influence negotiations and secure labor demands (Greer Reference Greer, Arnholtz and Refslund2024).

Societal power refers to unions’ ability to generate support, build alliances, and establish legitimacy within civil society. This can take the form of coalitional power, through networks with other organizations and social movements, or discursive power, by shaping public debates, influencing political agendas, and fostering collective beliefs that legitimize union demands (Schmalz et al. Reference Schmalz, Ludwig and Webster2018).

Some scholars distinguish between coalitional and discursive power as separate resources (Arnholtz and Refslund Reference Arnholtz, Refslund, Arnholtz and Refslund2024a), though they are often conceptualized together. In many cases, discursive power serves as a foundation for coalitional power, as establishing credibility and influencing public discourse are necessary conditions for unions to engage in cooperation and joint mobilization with other social movements.

As a whole, societal power plays a crucial role in amplifying both associational and structural power (Fox-Hodess and Santibáñez Reference Fox-Hodess and Santibáñez2020; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Kim and Villegas2020). This is particularly evident in moments of political and social crisis, such as general strikes or large-scale protests, where unions often take on a coordinating role in broader collective action (Osorio and Velásquez Reference Osorio and Velásquez2021). By securing alliances and maintaining public legitimacy, societal power enhances unions’ capacity to influence both policy and workplace struggles.

Finally, Institutional power refers to unions’ ability to mobilize resources within the state, including influence over labor policies, political parties, and legislators responsible for drafting and implementing these policies (Pérez Ahumada Reference Pérez Ahumada2023). These resources often emerge from previous negotiations and struggles between unions, the state, and employer associations (Schmalz et al. Reference Schmalz, Ludwig and Webster2018). As a result, unions can continue to leverage institutional power even when the associational strength that initially secured these gains has weakened.

Like other forms of union power, institutional resources fluctuate over time. For unions to maintain or expand their institutional influence, they must actively engage with governments and political parties responsible for legislating labor policies. This ongoing interaction shapes their ability to secure favorable policy changes. In this sense, as some scholars argue, unions’ relationships with governments and legislators should be considered an institutional resource rather than a societal one, as they operate within formal political and policymaking arenas (Pérez Ahumada Reference Pérez Ahumada2023).

The Challenge of Measuring Union Power: A Conceptual Proposal

One of the main challenges in applying the PRA to unionism is the difficulty of translating its theoretical definitions into measurable empirical observations (Arnholtz and Refslund Reference Arnholtz, Refslund, Arnholtz and Refslund2024b). Beyond the general complexities of operationalizing concepts, the core issue is that power resources refer to capacities—whether for collective action or resource mobilization—that often remain latent. In many cases, the mere potential to exercise power, rather than its actual deployment, is sufficient to exert pressure. The clearest example of this is the strike, where the threat of action can serve as a powerful bargaining tool (Perrone et al. Reference Perrone, Wright and Griffin1984).

From a methodological perspective, qualitative data collection techniques can help diagnose the presence and distribution of latent power resources within unions. However, this approach is difficult to apply in comparative analyses involving large datasets. A more practical alternative is to focus on the effective manifestation of power resources, assuming that their mobilization provides the best approximation of their capacity. This approach acknowledges that union power may sometimes be underestimated when it exists only in latent form or overestimated when mobilization occurs in a specific context without indicating a sustained capacity.

Applying this framework in a comparative perspective also requires defining a unit of analysis that adequately represents unionism at the chosen scale of study. While this is straightforward when examining a single company or sector, it becomes more complex when comparing unionism across countries. At this broader level, the concept of the labor movement provides a suitable analytical category. This refers to the segment of unionism that, regardless of its specific demands, directs its repertoire of action toward advancing workers’ interests beyond the company level. The labor movement integrates both grassroots and higher-level union organizations, transforming them into a deliberative social force with its own objectives, strategies, and actions (Becher Reference Becher, García, Becher and Cano2024). Although these strategies may not always be fully aligned, they collectively represent the broader union landscape and its role in shaping social and economic policies. In other words, the labor movement consists of publicly visible union activity, usually organized through national labor confederations or other central bodies that coordinate union action at a larger scale.

In the context of associational power, traditional organizational capacities play a central role. These include union membership level, internal cohesion, material infrastructure, and accumulated experience. However, beyond these structural attributes, it is crucial to evaluate how effectively unions translate their organizational strength into broader union power.

Associational power should not only be measured in isolation but also assessed in relation to the mobilization of other power resources. According to theoretical expectations, associational power acts as a “pivot,” either reinforcing or constraining other dimensions of union power (Pérez Ahumada Reference Pérez Ahumada2023). Analyzing these interactions provides deeper insight into a union’s capacity to leverage its internal resources effectively and exert influence across different arenas of labor relations.

Unlike associational power, structural power is best assessed through disruptive actions, particularly strikes. Work stoppages represent a direct exercise of structural power, as they can significantly disrupt production and distribution processes. While this approach does not capture latent structural power, it operates on the assumption that a credible strike threat requires a prior history of mobilization—an empirical indicator that can be observed and analyzed.

At a broader scale, the most effective way to assess structural power is by examining sectoral strikes, particularly in industries that are highly interconnected within the economy. Unions operating in these sectors hold greater leverage, as their work stoppages can trigger disruptions across supply chains and production networks, amplifying their bargaining position. Analyzing how and where unions mobilize structural power is therefore essential for evaluating their ability to shape economic and political decision-making.

The coalitional dimension of societal power can be assessed by examining unions’ ability to coordinate or mobilize resources alongside other social movements, either at the national or international level. This includes joint campaigns, protests, marches, or solidarity-based actions that reflect shared objectives. However, latent capacities, such as informal social ties between union leaders, affiliates, and activists from other movements, are far more difficult to observe unless they materialize in collective actions.

The discursive dimension of societal power requires instruments that measure unions’ capacity to influence public debate and shape discussions within civil society. This dimension also relates to the level of public trust in unions as institutions. However, measuring discursive power presents methodological challenges, particularly in comparative research, as it requires large-scale data collection that is difficult to standardize. Potential approaches include public opinion surveys and media analysis to estimate unions’ social legitimacy and visibility. Despite these challenges, the presence of strong alliances with civil society organizations can serve as an indirect indicator of unions’ societal legitimacy. In contexts where unions maintain stable and active networks with other movements, it is reasonable to infer that they hold a degree of public credibility and recognition beyond the workplace.

Institutional power can be assessed from multiple angles. A common approach is to examine the extent to which labor institutions protect trade union rights, including freedom of association, collective bargaining, and the right to strike. However, while these legal frameworks define the potential for union influence, they do not necessarily reflect unions’ actual capacity to exercise these rights. For this reason, it is more valuable to analyze how unions effectively engage with labor courts and regulatory institutions responsible for enforcing labor laws.

From the perspective of this study, a key indicator of institutional power is unions’ direct participation in state institutions, particularly those involved in shaping labor relations and policy reforms. This includes formal engagement in tripartite bodies, policy advisory councils, or legislative commissions.

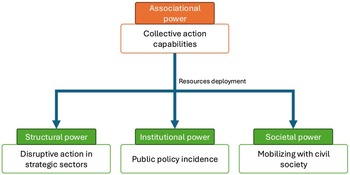

Another relevant measure is the strength of unions’ ties to political parties with legislative influence. The extent of union-party linkages can shape unions’ ability to advance labor-friendly policies, influence decision-making processes, and secure institutional support for workers’ demands (Murillo Reference Murillo2001). Figure 1 provides a diagram summarizing the proposed definitions.

Figure 1. A Conceptual Framework of Union Power.

Source: Authors’ elaboration, adapted from Pérez Ahumada (2023, 40).

The following section introduces a methodology that translates this conceptual framework into a strategy for data collection, measurement, and analysis.

Data and Methods

The Movlab Database

To achieve the objectives of this study, we employed the MovLab databaseFootnote 1 , an innovative dataset grounded in narrative codingFootnote 2 (Gamson Reference Gamson1975; Hodson Reference Hodson1999; Lieberman Reference Lieberman2010), that compiles information on labor movements in 17 Latin American countries between 1990 and 2020.

We developed this database in two phases. First, we and a team of researchers produced 17 in-depth and systematically structured qualitative reports, one for each country in the study. These reports trace the main dimensions of unionism in each country and analyze their evolution over the three decades under examination. Each report is anchored in a carefully selected body of bibliographic references, chosen to represent the most significant scholarship on unionism in the respective country for the study period.

Each report provides a comprehensive examination of ten key dimensions of unionism, including: (1) mapping of union organizations, (2) strength of unionism across economic sectors, (3) resources and activities, (4) internal organization, (5) services for members, (6) demands, (7) tactics, (8) repression, (9) links with institutional politics, and (10) connections with civil society.

Completing all reports took approximately a year and a half, with each report averaging around 60 pages in length.

In the second phase, we developed a set of variables and corresponding categories based on the ten dimensions covered in the narrative reports. We systematically assigned values to relevant segments of the narratives across all countries and time periods analyzed. To ensure methodological rigor, we followed the principles outlined by Hodson (Reference Hodson1999) and Lieberman (Reference Lieberman2010), which provide practical and validated guidelines for converting qualitative narratives into quantitative data. To facilitate this transformation, we created a coding sheet that structured the conversion of labor organization narratives into numerical codes.Footnote 3 Throughout the process, we held regular meetings to oversee the coding process and systematically assessed inter-coder reliability, ensuring the accuracy and validity of the results.

With 527 observations spanning 17 countries over 31 years, MovLab provides a comprehensive mapping of changes in labor field structures, the demands and tactical repertoire of labor movements, their relationships with political parties, governments, and other movements, among other dimensions. A key strength of this database lies in its ability to enable systematic comparisons of labor organizations and movements across different geographic units (i.e., countries) over time. This study relies on MovLab version 1.0, as of December 2024.

Drawing on this dataset, the next section outlines the operationalization strategy employed to develop each indicator of union power.

Measuring Union Power: Operationalization Strategy

To assess associational power, we incorporated four key indicators. First, mobilization capacity quantifies the ability of union federations or overarching organizations to mobilize their memberships for collective action—a crucial factor in organizing effective protests or strikes. This capacity is rated on a scale from 1 (None) to 4 (High).

Second, we included organizational capacity an indicator that provides a general inference of the organizational capacities of the main supra-organizational unions in each country. Coding teams derived this measure from the country reports, analyzing factors such as membership size, the structure of union confederations, and levels of participation. Organizational Capacity reflects the ability of unions to establish strong and stable organizational structures and is rated on a scale from 1 (none) to 4 (high).

Third, we developed a material resources index to evaluate the tangible assets controlled by labor organizations. This index considers four key dimensions that indicate whether unions exercise control over pension fund management, infrastructure, media holdings, and factory ownership. The material resources index was normalized to a 0 to 1 scale.

Finally, we included the supra-union organizational experience variable, which measures the experience level of the main supra-union organizations. This variable ranges from 1 to 3, where 1 indicates limited experience, meaning that either no national union confederations exist, or they were established very recently. At the other end, 3 represents extensive experience, where major confederations have a longstanding history of union struggle. We normalized all four variables on a 0 to 1 scale and constructed a composite associational power index by averaging them. The set of four variables used to construct this index achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.81, indicating excellent internal consistency.

Structural power is one of the most challenging forms of union power to capture, as it often remains latent and unobservable, rooted in the strategic positions of unions within the economy and labor market. However, when it manifests, it should be measurable through its effects. To assess structural power, we drew on the framework outlined in the previous section, focusing on the observable deployment of this form of power. We implemented this measurement strategy in two stages.

First, using information from the narrative reports, we identified the three most economically significant sectors in each country, which we termed strategic sectors. These sectors vary across countries; for instance, some economies are more reliant on mining, while others depend on agriculture or manufacturing (see Table A1 from the online supplement for a complete list of strategic sectors by country).

Next, we identified instances of mobilization within these strategic sectors. To capture these events, we constructed and coded three variables—Strategic Sector Capacity 1, Strategic Sector Capacity 2, and Strategic Sector Capacity 3—using the previously established methodology. These variables measure the extent of disruptive activities in the three main strategic sectors of each country, rated on a scale from 0 to 2: 0 indicates no disruptive activity; 1 represents disruptive activities without the majority support of the sector’s unions; and 2 denotes disruptive activities backed by a majority of unions in the sector.

Mobilization in strategic sectors does not necessarily occur annually but tends to emerge during specific periods, making it more appropriate to capture using defined time intervals. In this study, we measured structural power across presidential terms rather than arbitrary time periods, as unions often seek to demonstrate their strength in relation to political authorities, typically aiming to influence policy reforms or legislative changes. To more accurately reflect mobilization power in these sectors, we used the highest recorded value during each presidential term (see replication script in the data repository for coding procedures).

For instance, if the mining sector—deemed strategic in Chile—mobilized with majority union support during Michelle Bachelet’s presidency (2006–10), we would code that Strategic Sector Capacity as 2 for that entire four-year term. Although this approach has limitations and potential biases, it provides a reasonable approximation of latent structural power. Theoretically, structural power only becomes effective once prior mobilization establishes credibility and influence. Moreover, this measurement strategy aligns with our theoretical framework, which posits that structural power relies on associational power as a catalyst.

Finally, we included a general structural power indicator that assesses the overlap between the two most mobilized sectors and their structural power, rated on a scale of 0 to 2: 0 indicates no overlap; 1 indicates that only one mobilized sector possesses structural power; and 2 indicates that both main mobilized sectors exhibit structural power.

We normalized all four variables on a 0 to 1 scale and constructed a composite index of structural power by averaging them. The set of four variables used to construct this index yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.73, indicating satisfactory internal consistency.

In measuring societal power, we followed our conceptual framework by focusing on its coalitional dimension, aiming to capture the intensity of relationships between unions and diverse social actors. Historically, three major social sectors—resident, peasant, and indigenous organizations—have exerted significant influence in Latin American societies, regardless of a country’s development level. Accordingly, we assessed societal power using three variables that gauge the strength of union ties with these groups, each rated on a scale from 0 (no relationships) to 5 (strong, formal, and enduring connections actively leveraged to advance shared interests). We normalized the variables to a 0–1 scale and combined them into a composite societal power index by taking their average. The three variables used to construct this index achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75, indicating satisfactory internal consistency.

Following our conceptual framework, we measured institutional power by emphasizing unions’ effective participation in policymaking bodies, government consultations, and formal recognition as indicators of institutional power.Footnote 4 Consequently, we included four variables. First, we used government legitimation of unionism to gauge the extent of recognition and legitimacy the government grants to labor organizations, assigning values from 0 (low recognition) to 3 (high recognition).

Second, union participation in public policies evaluates union influence in policymaking on a scale from 1 (low) to 3 (high). A low score indicates no involvement of labor organizations in tripartite bodies, working groups, or government commissions. A medium score reflects participation in these spaces but with ineffective or inconsistent outcomes over time. A high score denotes regular and effective engagement in these forums, contributing to sustained policy influence.

Third, influence in government measures the extent to which the labor movement aligns with and influences government decision-making. It is rated from 1 (low or no influence) to 3 (explicit affinity and influence between major labor organizations and the government).

Finally, responsiveness and openness to dialogue assesses the government’s willingness to engage with union demands. This variable ranges from 1 (the government is unwilling to negotiate with labor organizations) to 3 (the government generally shows openness to revisiting union demands, adjusting policies to reach agreements).

Although we do not directly measure unions’ ties to political parties, we account for them indirectly. Union-state relations—particularly government responsiveness and inclusion in public policy discussions—are inherently shaped by partisan structures (Korpi Reference Korpi1985; Murillo Reference Murillo2001). Since political parties mediate these interactions, their influence is embedded in our indicators, capturing their role as intermediaries between unions and the state.

As with previous indicators, we normalized all four variables to a 0–1 scale and constructed a composite institutional power index by averaging them. These four measures demonstrated excellent internal consistency, achieving a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88.

As outlined in the previous section, associational power primarily refers to the organizational capacities of trade unions at the national level. In contrast, the subsequent dimensions of union power focus more on their observable deployment in various contexts, including interactions with the state, mobilization within strategic sectors, and alliances with broader social movements.

Each of the four union power indices was constructed by assigning equal weight to its internal component indicators. As discussed in González et al. (Reference González, Sehnbruch, Apablaza, Pineda and Arriagada2021, 118), weighting schemes in multidimensional indices can be based on normative, empirical, or equal-weighting criteria. In the construction of these indices, we adopted an equal-weighting approach within each index to ensure transparency and to avoid introducing normative assumptions about the relative importance of individual indicators. One of the aims of this article is precisely to generate comparative evidence that may inform future debates on the relative salience of different union power resources and their constituent elements.

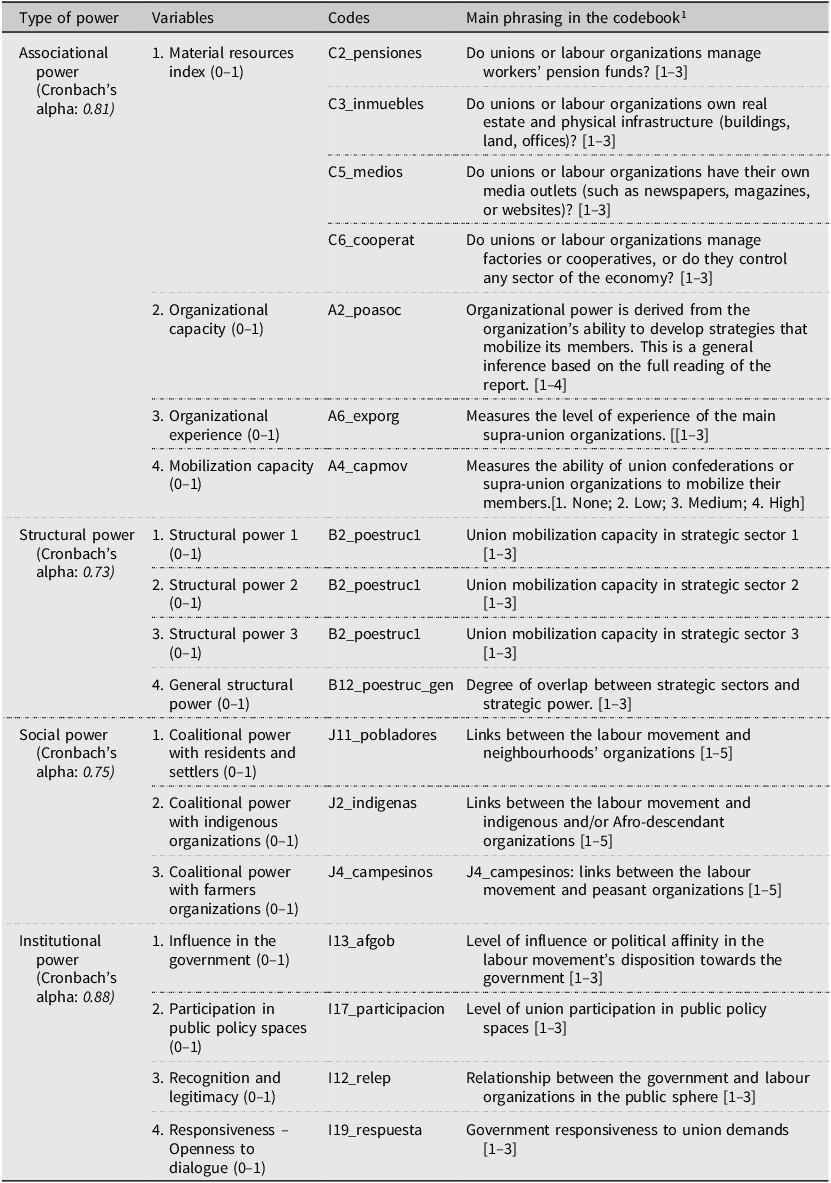

A summary of the indexes, their corresponding variables, and the phrasing used for each indicator is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Indicators for Types of Union Power

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on MovLab data.

1 This table provides a summarised version of each indicator rather than the full phrasing. For a more detailed description, please refer to the codebook available on Dataverse.

While Cronbach’s alpha assesses the internal consistency of the items within each index, it does not determine whether they collectively measure a single latent construct or if multiple factors are present. To address this limitation, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to verify that the items within each index capture a single underlying dimension rather than multiple power resources. Establishing unidimensionality is crucial for ensuring the validity of the indexes, confirming that they represent a coherent, theoretically grounded, and empirically robust measure.

First, we included the full set of items in a parallel factor analysis which we used to determine the appropriate number of factors to retain. The results, presented in Figure A1 in the online supplement, indicate that four factors adequately capture the structure of the data, providing strong empirical support for a four-factor model.

We then performed an exploratory factor analysis using a four-factor solution with maximum likelihood estimation and varimax rotation, shown in Table 2. The resulting factors closely align with the dimensions of union power. Institutional power loads heavily on variables reflecting government recognition and policy influence. Associational power shows strong loadings on measures of unions’ capacity to mobilize and organize members. Structural power is associated with unions’ capacity to mobilize in strategic economic positions. Societal power reflects unions’ abilities to form alliances and maintain influence within civil society.

Table 2. Factor Loadings for Dimensions of Union Power and Their Communalities

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on MovLab data.

The total communalities value of 9.14 indicates that the extracted factors provide a meaningful representation of the underlying dimensions of union power. Given that the table includes 15 observed variables, the extracted factors explain approximately 61% (9.14/15) of the variance across all variables. This suggests a relatively strong explanatory power, confirming that the factor solution captures a substantial portion of the relationships among the variables.

Because the factors are orthogonal and include both positive and negative values, we used the linear indices constructed from the associated variables in subsequent analyses. These linear indices enhance interpretative clarity and facilitate statistical procedures such as cluster analysis, which require positive values. To further validate this approach, we assessed construct validity through a correlation analysis between the linear indices and the factors extracted from the factor analysis. The correlations were exceptionally strong, ranging from 0.92 for the associational, societal, and structural power indices to 0.95 for the institutional power index. These findings confirm the robustness of the indices and their strong alignment with the underlying factors, reinforcing their suitability for analytical purposes.

Results: Assessing Union Power in Latin America

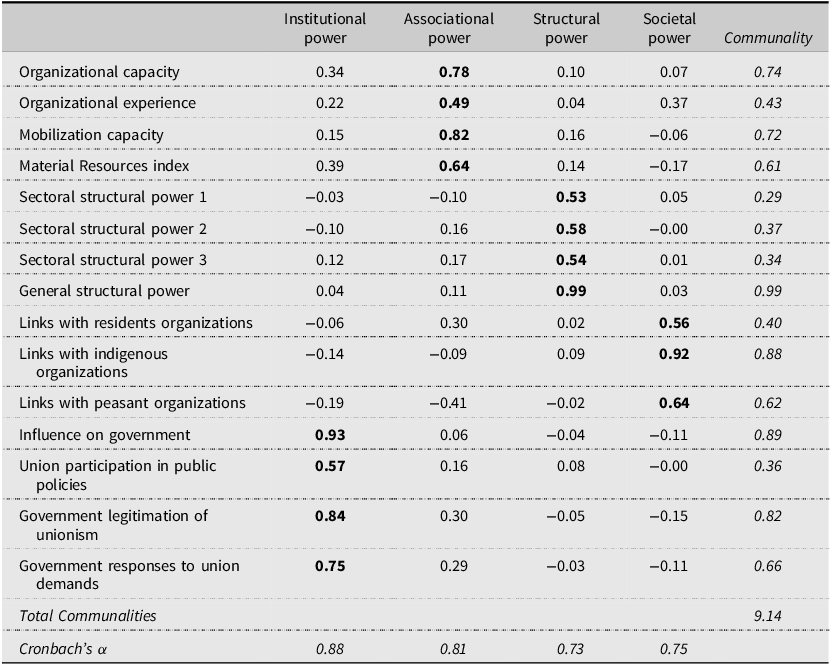

Despite significant differences in the labor relations systems and union structures across the countries analyzed, Figure 2 offers an initial global overview of how the four types of union power evolved in Latin America between 1990 and 2020. Each line shows how the level of each type of power changed over time, standardized for easier comparison.

Figure 2. Temporal Evolution of Power Resources in Latin America (1990–2020).

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on MovLab data.

The figure shows that structural and institutional power among Latin American unions increased during the first two decades of the analysis but declined over the last decade. Associational power has remained relatively stable, while societal power, though generally stable, has exhibited slightly greater volatility. These trends provide a broad overview, but a more detailed country-level analysis is necessary to fully understand the underlying dynamics.

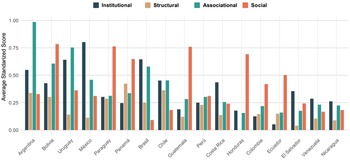

Figure 3 presents the average standardized scores for four dimensions of union power—institutional, structural, associational, and social—across Latin American countries. The variation in scores highlights significant cross-national differences in the configuration of union power.

Figure 3. Distribution of Power Resources Across Latin American Countries (1990–2020).

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on MovLab data.

Argentina, Uruguay, and Bolivia display the highest levels of union power across most dimensions, particularly in associational power. This reflects the historical strength of their labor movements, where well-established union confederations have maintained a strong organizational presence (Etchemendy Reference Etchemendy2019). In contrast, Nicaragua, Venezuela, and El Salvador consistently show low scores across all dimensions, suggesting weaker union influence. This may be linked to factors such as authoritarian governance, labor market informality, and state co-optation or repression of independent union activity. Intermediate cases exhibit more complex patterns of union power. Overall, Figure 3 is a first approach to the heterogeneous nature of union power in Latin America.

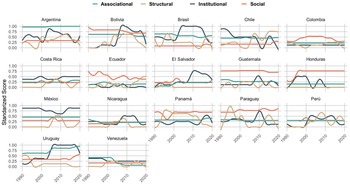

While country-level averages provide an important first step for comparing union power across Latin America, they mask important internal and temporal variations. Figure 4 illustrates the evolution of the four dimensions of union power across 17 Latin American countries between 1990 and 2020. This longitudinal perspective reveals distinct national trajectories and shifting patterns of union influence over time.

Figure 4. Evolution of Power Resources Across Latin American Countries (1990–2020).

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on MovLab data.

Associational power remains the most stable dimension across countries, with Uruguay and Argentina exhibiting consistently high levels. Institutional power, while relatively stable, fluctuates in response to changing political conditions, reflecting unions’ varying capacity to influence public policy. Social power appears particularly stable in most cases but shows some variation in others, notably in Ecuador and Colombia. These fluctuations suggest that unions in certain countries experience shifts in societal support or their connections with broader social movements depending on political contexts. Structural power, represented by the gold line, exhibits the greatest variation throughout the period, as it captures unions’ capacity to mobilize within strategic sectors. In countries such as Chile, for instance, structural power has increased significantly in recent years, reflecting a resurgence of labor strikes in key economic sectors (Medel et al. Reference Medel, Velásquez and Pérez2021).

The relative stability of associational power over time—compared to the more pronounced variation in institutional, structural, and societal dimensions—reflects the long-term organizational legacies it captures, such as mobilization capacity, internal cohesion, and accumulated experience at the supra-organizational level. These features are structurally embedded and evolve more slowly than dimensions like institutional or societal power, which respond more directly to shifts in political opportunities or alliance dynamics. This temporal asymmetry is analytically meaningful: it underscores that the dimensions of union power do not necessarily co-evolve and reinforces the value of treating them as distinct rather than collapsing them into a single index. It also illustrates the strategic adaptability of unions, which may draw more heavily on certain forms of power—such as societal alliances—when others, like institutional access, are restricted.

The figure also highlights sharp contrasts between subregions. The Southern Cone countries generally maintain higher levels of associational power, reinforcing their historically strong and institutionally embedded union movements. In contrast, Central American countries such as Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador display consistently low scores across all dimensions, particularly in institutional and structural power, reflecting weaker union structures and limited state recognition. Venezuela and Nicaragua also show persistently low levels of union power, with further declines toward the end of the period, suggesting an increasingly restrictive environment for union activity.

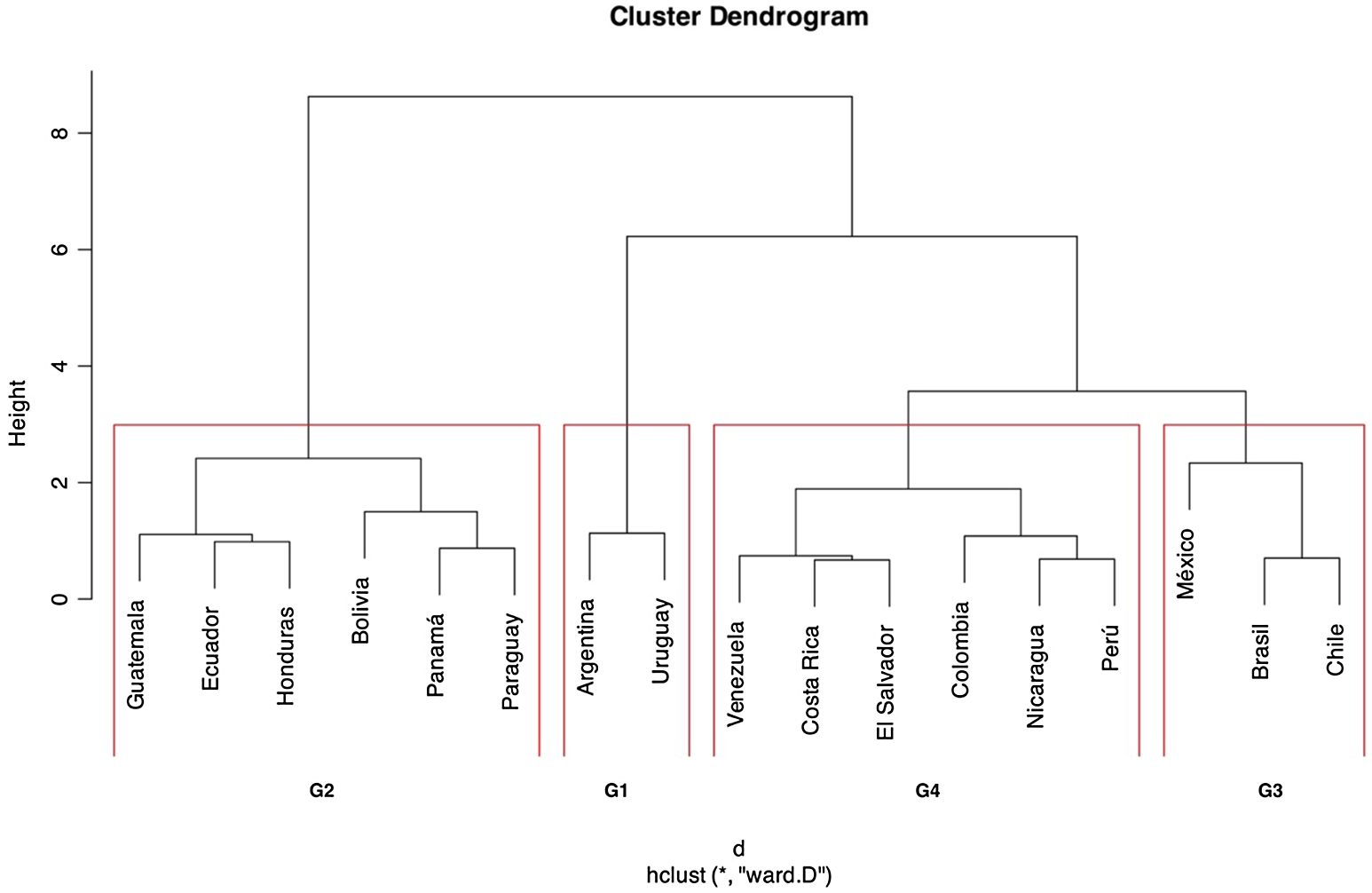

Although the previous scores offer a preliminary understanding of unionism in Latin America, it is crucial to adopt a classification approach that links these distributions to typologies reflecting the region’s diverse historical legacies and contemporary realities. The hierarchical clustering method allows for grouping countries based on the relative configuration of their four types of power resources rather than solely on their absolute levels of union power. By revealing how these dimensions interact within each national context, hierarchical clustering adds a texture that enables a deeper and more meaningful understanding of the structural characteristics and strategic choices of labor movements in Latin America.

The dendrogram in Figure 5 classifies Latin American countries into four distinct clusters based on their union power configurations, applying the K-means procedure. This method groups countries according to shared patterns rather than absolute equivalence in union strength. The height of the connections on the vertical axis indicates the degree of similarity between countries within a group, with lower connections reflecting greater similarity.

Figure 5. Hierarchical Clustering of Latin American Countries Based on Power Resources.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on MovLab data.

Group 1 includes Argentina and Uruguay. Group 2 consists of Guatemala, Ecuador, Honduras, Bolivia, Panama, and Paraguay. Group 3 comprises Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. Group 4 includes Venezuela, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Colombia, Nicaragua, and Peru. This classification underscores the diverse structures of union power across the region.

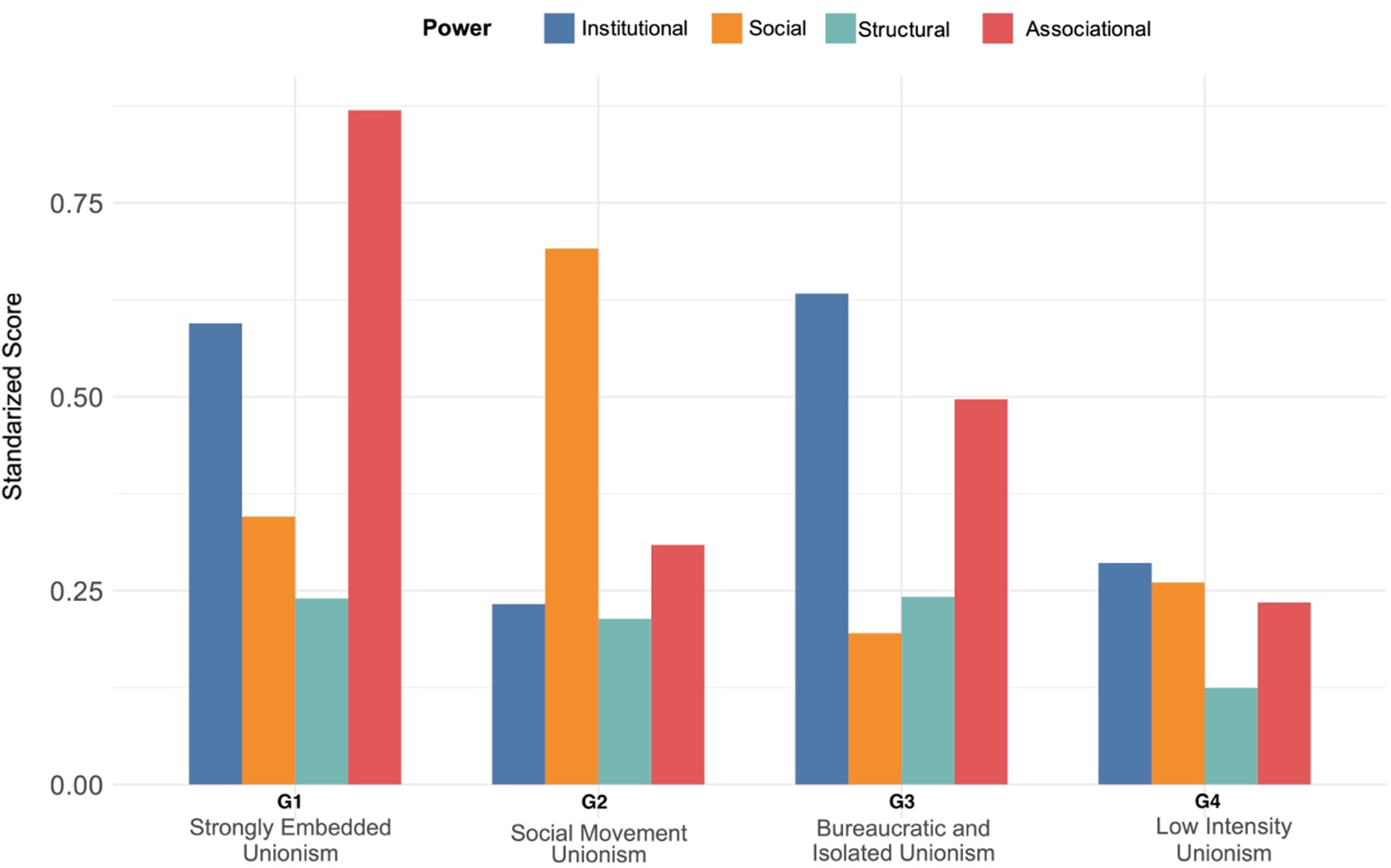

To improve the interpretation of each group, Figure 6 displays the distribution of union power within each cluster, enabling a more in-depth comparative analysis. Based on these distributions, each country’s affiliation to its respective group, and the earlier findings, we propose a name for each group and offer an exploratory analysis of their key characteristics.

Figure 6. Distribution of Power Resources across Unionism Typologies Derived from Hierarchical Clustering.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on MovLab data.

We designate the first group as “strongly embedded unionism” (Argentina and Uruguay), representing the most structured and resilient form of unionism in the region. Characterized by robust associational power, stable organizational structures, and a broad membership base, their embedded nature fosters internal cohesion and amplifies their influence across multiple dimensions of union power, particularly in institutional bargaining and negotiations with the state. The labor movements in this cluster function as central actors within national labor systems, combining a deeply rooted organizational tradition with high levels of institutionalization. Unlike other forms of unionism that depend on episodic cycles of mobilization, embedded unionism is distinguished by its stability, continuity, and self-sustaining organizational capacity within both labor and political spheres. Argentina and Uruguay represent this model, with unions that maintain high affiliation rates, strong collective bargaining power, and sustained influence over labor policy (Etchemendy Reference Etchemendy2019). While they can mobilize on a large scale when necessary, their primary strength lies in institutional endurance and the ability to shape long-term labor and social policies.

The second group is the social movement unionism (Guatemala, Ecuador, Honduras, Bolivia, Panama, and Paraguay), and represent a type of unionism that thrives on collective action and solidarity beyond the boundaries of industrial relations. It is characterized by high levels of social power, as unions leverage their ties with marginalized groups and social movements to amplify their demands (Roberts Reference Roberts2008). However, labor movements often struggle with low institutional recognition and limited structural power, making sustained mobilization and grassroots engagement crucial to their influence. This model is particularly prevalent in contexts where institutional channels for labor representation are weak or inaccessible, compelling unions to seek legitimacy and power through extra-institutional mobilization. While their institutional influence may be constrained, their ability to mobilize societal support provides them with an alternative source of political leverage.

We designate the third group as “bureaucratic and isolated unionism” (Brazil, Chile, and Mexico), a highly institutionalized but socially disengaged form of labor organization. Although unionism in these countries receives formal recognition and participates in policy discussions and collective bargaining, this institutional integration often occurs at the expense of grassroots mobilization and broader alliances, leaving them detached from wider societal struggles. Characterized by strong institutional power but weak social support, they rely primarily on legal frameworks, tripartite negotiations, and state-mediated bargaining rather than direct worker mobilization. Neoliberal labor reforms in Brazil, Chile, and Mexico have further weakened traditional mobilization strategies while preserving union engagement in institutional negotiations (Cook Reference Cook2010). Despite their formal presence in policymaking, these unionisms face challenges in extending its influence beyond the institutional sphere, making them increasingly vulnerable to political shifts and detached from grassroots labor struggles.

Finally, low-intensity unionism (Venezuela, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Colombia, Nicaragua, and Peru) represents a weakly institutionalized and fragmented model of labor organization, characterized by limited associational, institutional, structural, and social power. In this context, unions struggle to establish a meaningful presence in labor relations due to restrictive legal frameworks, economic instability, state repression, or internal organizational weaknesses. Consequently, their ability to mobilize workers, influence policy, or engage in broader social movements remains marginal and inconsistent. Unlike more embedded or institutionally recognized forms of unionism, low-intensity unionism lacks strong organizational structures and operates in highly precarious conditions. Additionally, these unions often face state hostility or employer resistance, further limiting their capacity to function effectively. While episodes of labor activism may arise in response to specific crises, these unions generally lack the long-term organizational resilience needed to sustain labor struggles. As a result, unionism in these countries tends to be reactive, with minimal influence in national labor politics.

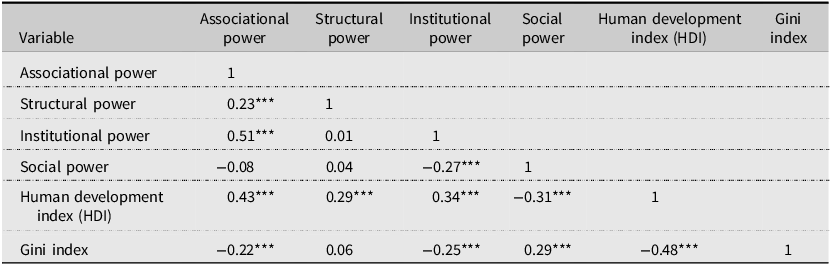

The previous groups’ provision and distribution of union power resources, reveal that these dimensions do not always align. To examine this further, Table 3 presents the correlations between different types of union power and other variables that we consider relevant for deeper analysis.

Table 3. Correlation Matrix of Power Dimensions, Human Development, and Income Inequality

The values in the matrix represent Pearson correlation coefficients. Statistical significance levels are indicated as follows: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on MovLab data.

The strongest correlation among union power dimensions is between associational and institutional power (0.51), indicating that unions with strong internal cohesion and broad membership bases tend to secure greater formal recognition and policy influence. This finding supports the view that associational power underpins institutional power: unions capable of mobilizing workers effectively are better positioned to participate in tripartite negotiations, engage state institutions, and shape labor policies. In contrast, weak associational power often leads to fragmented unionism, limiting institutional legitimacy.

Associational power also shows a moderate but noteworthy correlation with structural power (0.23), understood as workers’ ability to disrupt production through strategic positions in the economy. By contrast, institutional power exhibits a weak correlation with structural power (0.01), challenging the assumption that a strong institutional presence automatically translates into greater leverage in the production process. Rather, structural power is context-dependent, reflecting sectoral dynamics and hinging on associational capacity (Silver Reference Silver2005).

Social power—measured by unions’ ability to build alliances with civil society—reveals a near-zero correlation with associational power (−0.08). This suggests trade-offs between institutionalization and grassroots activism, as unions deeply embedded in formal negotiations may become less responsive to social movements, whereas those with limited institutional access often cultivate extra-institutional strategies (Roberts Reference Roberts2008). This tension echoes a longstanding divide in Latin American labor movements between corporatist unionism, which secures formal recognition but risks bureaucratization, and social movement unionism, which pursues broad social alliances but struggles to achieve institutional sway. The observed correlation patterns are consistent with the theoretical premise that union power is a multidimensional construct composed of distinct yet potentially interacting resources.

Correlations with the human development index (HDI) and the Gini coefficient provide additional insights. Strong associational (0.43) and institutional (0.34) power relate to higher HDI values and show negative relationships with the Gini (−0.22 and −0.25, respectively), in line with arguments that well-organized, institutionally recognized unions help reduce inequality and foster social progress (Freeman and Medoff Reference Freeman and Medoff1984). In contrast, social power displays a negative correlation with HDI (−0.31) and a positive correlation with the Gini (0.29), implying that extra-institutional union activism often arises in less developed or institutionally weaker contexts. These relationships are not necessarily causal; weaker governance or state capacity in such settings may hamper both labor rights enforcement and overall development.

Overall, these findings underscore the critical role of institutional frameworks in shaping unions’ influence and broader socio-economic outcomes. In the concluding section, we revisit these correlations and their implications for labor movements.

Conclusion

This research note introduces a conceptual and methodological framework for measuring union power resources and applies it to a comparative analysis across Latin America. The goal is to deepen our understanding of how unions position themselves and operate within different national contexts.

From a theoretical standpoint, it underscores the importance of distinguishing between potential and manifest forms of power. While associational strength often serves as a “pivot” for activating other forms of power, it does not automatically translate into institutional influence, economic leverage, or societal alliances.

A central methodological contribution of this study lies in the operationalization of four distinct dimensions of union power, moving beyond conventional metrics such as union density or formal bargaining coverage. Drawing on an original database constructed through narrative coding, which captures a wide range of variables across ten dimensions of labor movement activity in 17 Latin American countries over three decades, we apply hierarchical clustering to classify countries into distinct models of unionism. The “organizationally embedded unionism” model reflects historically robust associational power embedded within protective labor relations frameworks, providing unions with significant institutional leverage. At the opposite end of the spectrum, “low-intensity unionism” encompasses countries with limited union traditions which, at least during the period analyzed, show minimal mobilization across all dimensions of union power.

Between these extremes, unions appear to adopt two distinct strategies. In countries with a strong corporatist legacy (Schmitter, Reference Schmitter1974) or historically close ties between unions and political parties, declining associational power is often offset by institutional power. These unions maintain influence through residual labor relations frameworks, even as their mobilization capacity weakens—a pattern we define as “bureaucratic and isolated unionism.” Conversely, where corporatist traditions are weaker or absent and associational power is also low, unions compensate by developing societal power through alliances with civil society organizations, forming what we term “social movement unionism.” While these classifications require further empirical testing, they suggest that unions adjust their strategies based on the resources available to them, shaping distinct labor activism trajectories across the region.

Additionally, the findings suggest an inverse relationship between institutional and societal power when associational power is weak, as indicated in Table 3. This implies that unions engage more with civil society when institutional channels are ineffective, whereas strong institutional frameworks tend to discourage alliances with social movements. This challenges the assumption that a large membership base necessarily results in sustained political or economic power. Instead, the relationships between power resources are complex and not always synergistic.

Despite its contributions, we recognize that our data and methodological strategy have limitations that require future adjustments. For instance, further research could refine the measurement of power resources, incorporate additional indicators, and explore causal relationships between different dimensions of union strength in greater depth.

Another limitation is that this study may underestimate structural power in cases where unions possess greater associational strength, as the latent capacity for mobilization is not fully captured in our analysis.

While our indicators are designed to capture national-level patterns, we acknowledge that local-level associational dynamics may require alternative measurement strategies. Future research could extend this framework by incorporating more disaggregated or temporally sensitive indicators to explore these interactions more fully. Future research could address this by incorporating more temporally sensitive indicators or disaggregated data, such as administrative records, survey-based measures, or case-level observations of grassroots mobilization.

This methodology should be viewed as a first step towards a more comprehensive comparative study of union power in Latin America. Further efforts are needed to generate new insights into how unions adapt their strategies and deploy their resources in response to political and social contexts across different regions.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2025.10018

Data availability statement

Data files can be accessed at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/FCUEYP

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Nicolás Somma for his leadership of the MovLab Project (Fondecyt Grant No. 1200190). Rodrigo Medel acknowledges support from Fondecyt Grants No. 1251051 and No. 1240777, as well as from the ANID Millennium Science Initiative Program (Grant No. NCS2024_065).

Competing interests

Rodrigo M. Medel and Sebastián Osorio Lavin declare none.