Introduction

Historically, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in girls and women remains under- or misdiagnosed leading to significant personal and societal consequences [Reference Hinshaw, Nguyen, O’Grady and Rosenthal1]. Girls under 12 years are diagnosed with ADHD almost four times less often than boys (1:4.8), but this ratio becomes closer to equal by adulthood [Reference Martin, Langley, Cooper, Rouquette, John and Sayal2, Reference Murray, Booth, Eisner, Auyeung, Murray and Ribeaud3]. This suggests that many girls are overlooked during childhood, leading to delayed diagnoses [Reference Hinshaw, Nguyen, O’Grady and Rosenthal1]. A lack of awareness among clinicians may underlie this delay in diagnosis [Reference Attoe and Climie4], while other factors such as differences in symptom presentation [Reference Slobodin and Davidovitch5]; “male-stereotype” diagnostic criteria [Reference Mowlem, Agnew-Blais, Taylor and Asherson6]; parental, referral, and informant bias may also influence diagnosis in girls [Reference Slobodin and Davidovitch5, Reference Young, Adamo, Asgeirsdottir, Branney, Beckett and Colley7]. Additionally, hormonal fluctuations significantly impact women with ADHD. Therefore, sex and gender differences, as well as psychosocial expectations must be considered to improve female-specific research and clinical practice.

ADHD and female gender: Psychosocial expectations and contextual burden

Currently, girls may not meet diagnostic thresholds unless their symptoms are particularly severe or accompanied by additional problems, such as emotional difficulties or academic impairment [Reference Quinn and Madhoo8]. Masking of symptoms in girls and comorbid anxiety and depression also complicate the diagnosis of ADHD; these factors may result in a low index of clinical suspicion for ADHD in females [Reference Hinshaw, Nguyen, O’Grady and Rosenthal1, Reference Quinn and Madhoo8, Reference Quinn9]. Furthermore, developmental, social, and cultural influences can affect the accuracy of diagnoses throughout the female lifespan. For instance, societal norms play a significant role in shaping perceptions of appropriate behaviour, and these norms may vary by gender [Reference Attoe and Climie4] and ethnic group [Reference Shi, Hunter Guevara, Dykhoff, Sangaralingham, Phelan and Zaccariello10, Reference Waite and Ivey11], potentially impacting how symptoms are recognised and interpreted. The novelty of research on female ADHD may also play a role [Reference Oroian, Costandache, Popescu, Nechita and Szalontay12]. (Recent) research describes distinct cognitive [Reference Stibbe, Huang, Paucke, Ulke and Strauss13], social [Reference Faheem, Akram, Akram, Khan, Siddiqui and Majeed14], clinical [Reference Hayashi, Suzuki, Saga, Arai, Igarashi and Tokumasu15], psychiatric [Reference Siddiqui, Conover, Voss, Kern, Litvak and Antunes16, Reference De Rossi, Pretelli, Menghini, D’Aiello, Di Vara and Vicari17], neurochemical [Reference Endres, Maier, Feige, Goll and Meyer18], neuroanatomical [Reference Valera, Brown, Biederman, Faraone, Makris and Monuteaux19–Reference Peterson, Duvall, Crocetti, Palin, Robinson and Mostofsky21], prescription rate [Reference Martin, Langley, Cooper, Rouquette, John and Sayal2, Reference Kok, Groen, Fuermaier and Tucha22], and emotional challenges [Reference Attoe and Climie4] in female compared to male ADHD. Girls and women with ADHD often face unique comorbidities: cognitive [Reference Mahendiran, Brian, Dupuis, Muhe, Wong and Iaboni23], binge eating [Reference Appolinario, de Moraes, Sichieri, Hay, Faraone and Mattos24], chronic fatigue [Reference Young, Adamo, Asgeirsdottir, Branney, Beckett and Colley7], social [Reference Greene, Biederman, Faraone, Monuteaux, Mick and DuPre25], substance use [Reference Young, Adamo, Asgeirsdottir, Branney, Beckett and Colley7], anxiety, and mood comorbidities [Reference Attoe and Climie4, Reference Young, Adamo, Asgeirsdottir, Branney, Beckett and Colley7, Reference Quinn and Madhoo8, Reference Hayashi, Suzuki, Saga, Arai, Igarashi and Tokumasu15, Reference Quinn26, Reference Fraticelli, Caratelli, De Berardis, Ducci, Pettorruso and Martinotti27]. The management of ADHD in females may be suboptimal, where underdiagnosis and referral bias predominate [Reference Rapoport and Groenman28], and the following areas are neglected: differences in symptom presentation [Reference Young, Adamo, Asgeirsdottir, Branney, Beckett and Colley7], research prioritising sex differences in ADHD [Reference R29], and finally, the implications of gender differences in the psychosocial treatments of ADHD [Reference Camara, Padoin and Bolea30]. Failure to recognise and diagnose ADHD in women can result in prolonged periods of impaired self-esteem, difficulties in interpersonal relationships, challenges with self-regulation, and increased self-blame [Reference Attoe and Climie4].

ADHD and female sex: A theoretical framework of hormonal interplay

Biologically, an underlying theoretical framework suggests that varying oestrogen levels modulate the dopaminergic neurotransmission that is involved in ADHD pathophysiology [Reference Dorani, Bijlenga, Beekman, van Someren and Kooij31]. This hormonal influence extends beyond ADHD, with the (pre)menstrual phase consistently associated with symptom exacerbation across various psychiatric conditions, including psychosis, depression, suicidality, and alcohol use disorders [Reference Handy, Greenfield, Yonkers and Payne32].

In ADHD, periods of lower circulating oestrogen are believed to impact dopaminergic neurotransmission negatively, leading to cyclical variations in symptom severity [Reference Attoe and Climie4, Reference Young, Adamo, Asgeirsdottir, Branney, Beckett and Colley7] and diminished premenstrual treatment response to psychostimulants [Reference de Jong, Wynchank, van Andel, Beekman and Kooij33]. ADHD symptoms in women may exhibit fluctuations corresponding to hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle, with potential exacerbation during the premenstrual phase. Consequently, the timing of diagnostic assessments and treatment response evaluations in relation to the menstrual cycle may significantly influence both the establishment of an ADHD diagnosis and the perceived efficacy of interventions. This temporal relationship underscores the importance of considering hormonal fluctuations when assessing and treating ADHD in adult women [Reference Rapoport and Groenman28]. We propose that researchers and clinicians systematically consider the menstrual cycle phase and hormonal status to capture accurately the dynamic nature of ADHD symptoms in women and optimise therapeutic outcomes.

Since 2002, our specialised adult ADHD clinic treats approximately 1000 adults with ADHD per year, of which about 60% are women. Our team includes psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, doctors, and nurse practitioners, who have extensive experience in the assessment and treatment of ADHD in women across the lifespan, including expertise in hormonal and reproductive mental health. Some of our female patients report monthly fluctuating symptoms. We recently published a case series describing a small group of women with premenstrual worsening of ADHD and mood symptoms as well as less effect of current ADHD medication premenstrually [Reference Handy, Greenfield, Yonkers and Payne32]. Additionally, we treat many female patients who are diagnosed for the first time with ADHD as they present with (peri)menopausal exacerbation of symptoms. Our clinical experience has informed several research initiatives, including a pilot questionnaire distributed at a 2016 conference for women with ADHD (n = 200), revealing a two- to three-fold increase in premenstrual, postpartum, and (peri)menopausal mood symptoms compared to the general Dutch population (unpublished data).This was confirmed by our subsequent study in women with a formal diagnosis of ADHD [Reference Dorani, Bijlenga, Beekman, van Someren and Kooij31].

In this study, we offer a clarifying framework to understand fluctuating symptom levels in female ADHD as well as practical tools for research and clinical practice.

Methods

Clinical expertise and protocol development process

This protocol was developed collaboratively by the three authors in an iterative manner: DW and SJJSK are psychiatrists with a background in adult ADHD research, including biological rhythms and female-specific aspects of ADHD. SJJSK is a professor of adult ADHD and was a co-founder of the Head Heart Hormones (H3)-Network in the Netherlands, an interdisciplinary collaboration aimed at improving women’s health care, amongst General Practitioner (GPs), psychiatrists, gynaecologists, and cardiologists treating women. In addition, DW and SJJSK are editor and founder (respectively) of the DIVA Foundation, providing a semistructured clinical interview for diagnosing ADHD translated into more than 30 languages. MdJ is a medical doctor, cultural analyst, and doctoral researcher currently analysing data from a large online survey of women with ADHD.

Clinical insights were informed by direct patient care (including many women presenting with (peri)menopausal exacerbation of symptoms and first-time ADHD diagnoses in adulthood), regular multidisciplinary case discussions, and ongoing participation in national and international ADHD research networks.

Literature review and integration

To complement clinical experience, we conducted a targeted literature review focusing on hormonal influences on (1) ADHD symptomatology in women and (2) diagnostic and treatment considerations. Relevant references were identified through PubMed and Embase searches (keywords: “ADHD,” “women,” “hormones,” “menstrual cycle,” “menopause,” “diagnosis,” “treatment”), as well as through the review of bibliographies from key articles and clinical guidelines published between 2000 and April 2025. Key findings from the literature were synthesised and integrated with clinical observations to inform the development of practical tools and recommendations. Where appropriate, we also consulted online sources identifying similar research gaps in women with ADHD [Reference R29].

Protocol development process

Initial protocol drafts were based on observed clinical patterns and unmet needs, particularly regarding symptom fluctuations across hormonal transitions. These drafts were refined through discussion and updated to reflect emerging evidence from the literature.

Results

Review: Periodical worsening of symptoms

We identified four articles meeting our search criteria in PubMed and Embase (published 2000–2024) that directly addressed hormonal influences on ADHD symptomatology, diagnosis, or treatment in women [Reference Camara, Padoin and Bolea30, Reference Burger, Erlandsson and Borneskog34–Reference Haimov-Kochman and Berger36].

A systematic review described the relationship between sex hormones, reproductive stages, and ADHD. It concluded that hormonal transitions (puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause) can significantly influence symptom severity and treatment response, but that empirical data remain sparse [Reference Camara, Padoin and Bolea30].

Review: Menstrual cycle and symptom fluctuation

A qualitative study exploring the lived experiences of women with ADHD regarding the menstrual cycle’s impact on their symptoms [Reference Burger, Erlandsson and Borneskog34]. Participants consistently reported that ADHD symptoms – particularly inattention, emotional dysregulation, and executive dysfunction – worsened during the late luteal and menstrual phases, coinciding with declining oestrogen levels. Many women perceived reduction in the efficacy of their usual ADHD medication during these phases. Two other studies described how cognitive functions and ADHD symptoms may fluctuate with hormonal changes throughout the menstrual cycle [Reference Roberts, Eisenlohr-Moul and Martel35, Reference Haimov-Kochman and Berger36]. The first highlighted that ADHD symptoms were highest during the early follicular and early luteal (postovulatory) phases, when oestrogen levels are low or rapidly declining, especially in women with high trait impulsivity [Reference Roberts, Eisenlohr-Moul and Martel35]. The second proposed that the interaction between oestrogen and the neurotransmitters dopamine and noradrenaline, could underlie some clinical features of ADHD in women [Reference Haimov-Kochman and Berger36]. Oestrogen modulates these neurotransmitter systems and may influence cognitive and emotional regulation [Reference Eng, Nirjar, Elkins, Sizemore, Monticello and Petersen37].

Pharmacotherapy adjustments

We previously published a community case series, where nine women with ADHD and premenstrual symptom worsening underwent individualised increases in psychostimulant dosage during the premenstrual phase. All participants experienced improvements in ADHD and mood symptoms, with minimal adverse events. Premenstrual inattention, irritability, and energy levels improved to resemble those of non-premenstrual weeks, and all women opted to continue with the adjusted regimen [Reference de Jong, Wynchank, van Andel, Beekman and Kooij33].

Clinical protocol

Assessment

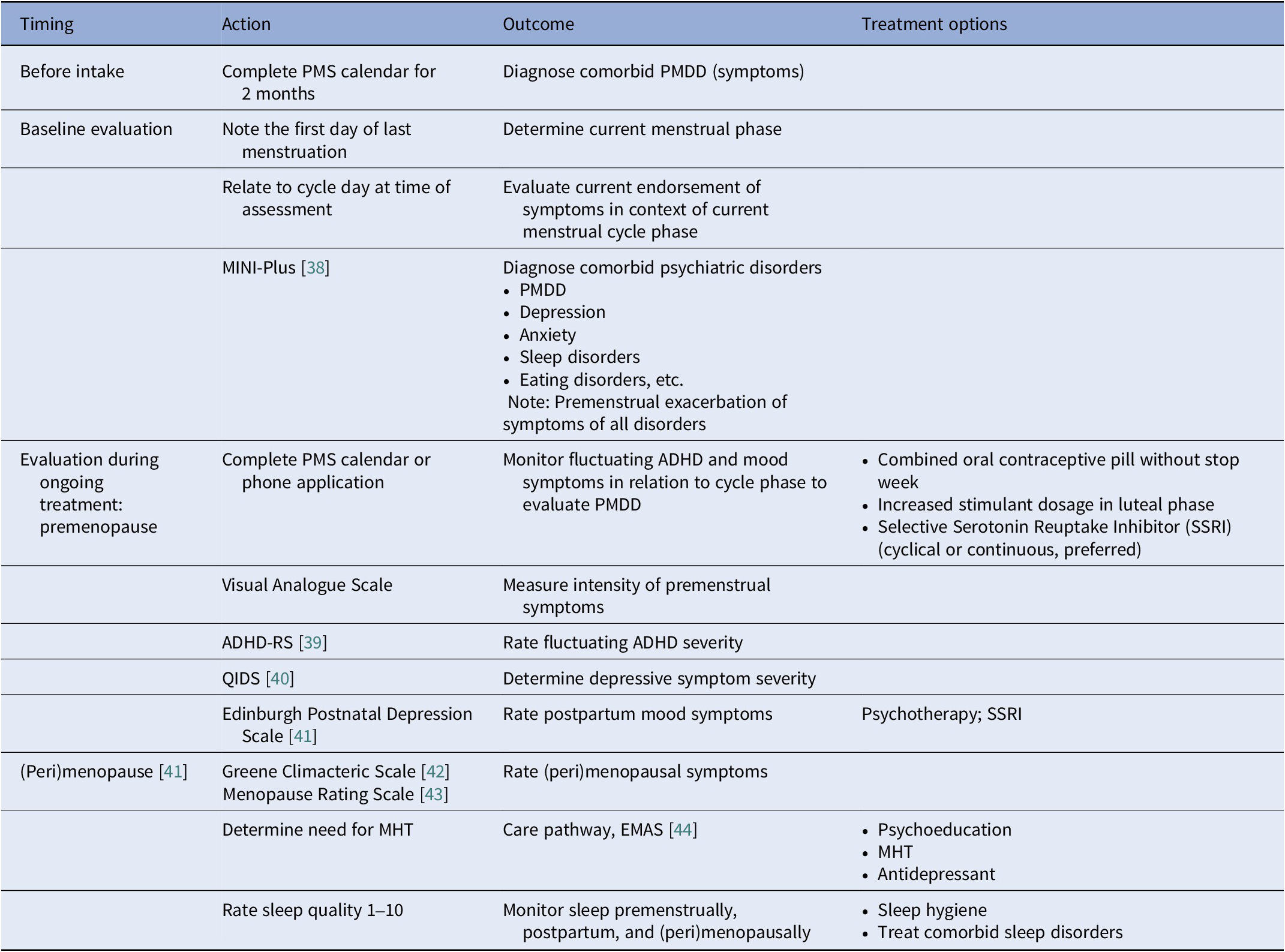

Based on our clinical experience, we recommend menstrual cycle awareness: consider menstrual phase when assessing symptoms and treatment response. At baseline evaluation, routine assessment should include the first day of last menstruation, average cycle length, and use of hormonal contraception or hormone therapy. The current menstrual phase (follicular or luteal) should be determined to contextualise symptom severity and treatment response. Daily tracking should continue throughout treatment to monitor symptom fluctuations across the cycle. ADHD and mood symptoms should be tracked daily for at least 2 months. A premenstrual syndrome (PMS) calendar and a scale for the severity of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) symptoms are helpful here (see Table 1). Useful menstrual cycle applications include Clue, Euki, Flo, Glo, Natural cycles, and Periodical. Comorbidities such as PMDD, (peri)menopausal depression, anxiety, somatic symptoms, and sleep disorders should be screened for, using validated questionnaires. The MINI-Plus has been validated across diverse populations and settings, demonstrating its diagnostic accuracy for a range of psychiatric disorders, including PMDD. It is particularly effective in clinical environments where comprehensive psychiatric evaluation is necessary and is considered the gold standard [Reference Gunter, Arndt, Wenman, Allen, Loveless and Sieleni45]. During the menstrual cycle and female lifespan, fluctuating ADHD symptom frequency and severity should be assessed. The ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS) is widely used and determines the impact on life activities [Reference Murphy and Adler46]. For monitoring of comorbid symptoms, questionnaires such as the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS, for depressive symptom severity) have been validated in adults and is sensitive to treatment changes [Reference Trivedi, Rush, Ibrahim, Carmody, Biggs and Suppes47]. Rating sleep quality from 0 to 10 can be useful to track fluctuating symptoms of sleep problems. Postpartum, females with ADHD should be screened for depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, which has been validated in various adult populations, including community samples [Reference Wickberg and Hwang48]. Women with ADHD who are above 40 years should also be screened for (peri)menopausal symptoms, using the validated Greene Climacteric Scale, [Reference Barentsen, van de Weijer, van Gend and Foekema49]. Furthermore, the Menopausal Rating Scale also effectively measures menopausal symptoms and is valid in comparison to established tools [Reference Schneider, Heinemann, Rosemeier, Potthoff and Behre50] (Table 1).

Table 1. Assessment tools and treatment options for ADHD and comorbidities according to the female life phases: The menstrual cycle, postpartum, and (peri)menopause

EMAS, European Menopause and Andropause Society; MHT, menopausal hormone replacement therapy; PMS, premenstrual syndrome; PMDD, premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

Treatment considerations

During treatment, we recommend psychoeducation about the impact of menstrual cycle and hormonal transitions on ADHD symptoms, if possible, in a group setting [Reference de Jong, Wynchank, Michielsen, Beekman and Kooij51]. Ongoing cycle and symptom tracking may foster better insight and self-management. We suggest monitoring ADHD medication effectiveness across the menstrual cycle and considering increasing psychostimulant dosage in the luteal phase if premenstrual worsening of ADHD and mood symptoms occur, with individualised dosing and careful monitoring. Increased psychostimulant dosage is not a substitute for SSRIs in depressive symptoms, or oral contraceptives for somatic complaints, but may be used complementarily. For comorbid PMDD, we recommend considering SSRIs (either luteal phase only or continuously) and psychotherapy. Combined oral contraceptives (without a stop week) may be considered for somatic symptoms and to stabilise hormone levels. For women over 40 years or with (peri)menopausal symptoms, hormone therapy and/or ADHD medication for new or worsening cognitive and mood symptoms can be considered. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and antidepressants (SSRIs, Selective Serotonin-Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitor (SNRIs), bupropion) may be considered for mood and somatic symptoms (Table 1).

Discussion

Women with ADHD appear to have periodical worsening of symptoms, closely related to hormonal fluctuations [Reference Rapoport and Groenman28, Reference Dorani, Bijlenga, Beekman, van Someren and Kooij31, Reference de Jong, Wynchank, van Andel, Beekman and Kooij33]. Therefore, female-specific research and clinical practice require different approaches as women transition between different life phases. Adequate treatment of females with ADHD requires consideration of the impact of hormonal fluctuations [Reference Hinshaw, Nguyen, O’Grady and Rosenthal1, Reference Young, Adamo, Asgeirsdottir, Branney, Beckett and Colley7].

With a targeted literature review, we examined hormonal influences on ADHD symptomatology, diagnosis, and treatment in women. We identified four primary studies directly addressing these influences [Reference Camara, Padoin and Bolea30, Reference Burger, Erlandsson and Borneskog34–Reference Haimov-Kochman and Berger36]. The literature is therefore sparse and much remains to be clarified in this field.

The qualitative study we reviewed suggested that ADHD symptoms worsened during the late luteal and menstrual phases, coinciding with declining oestrogen levels [Reference Burger, Erlandsson and Borneskog34]. Our own patients perceived reduction in the efficacy of their usual ADHD medication during these phases [Reference de Jong, Wynchank, van Andel, Beekman and Kooij33]. As described in two other studies reviewed, cyclical hormonal fluctuations, and especially rapid declines in oestrogen, appear to exacerbate ADHD symptoms [Reference Roberts, Eisenlohr-Moul and Martel35, Reference Haimov-Kochman and Berger36]. Fluctuations in oestrogen and progesterone have been shown to affect ADHD symptom severity and executive functioning significantly across the menstrual cycle [Reference Quinn and Madhoo8, Reference Roberts, Eisenlohr-Moul and Martel35]. Oestrogen may modulate neurotransmitter systems central to attention and executive function. Through its effects on dopamine pathways, it is also reported to impact inhibitory control, which is relevant to emotional regulation [Reference Haimov-Kochman and Berger36]. In adulthood, girls and women with ADHD experience more emotional dysregulation than males with ADHD. Emotional dysregulation in ADHD is often misattributed to other disorders, such as (bipolar) depression or personality disorders [Reference Quinn and Madhoo8]. Women and girls frequently internalise their symptoms, which may result in comorbid depression, anxiety, and eating disorders [Reference Attoe and Climie4, Reference Young, Adamo, Asgeirsdottir, Branney, Beckett and Colley7–Reference Quinn9, Reference Fraticelli, Caratelli, De Berardis, Ducci, Pettorruso and Martinotti27]. One study found that girls with ADHD are 2.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with major depression than their female peers without ADHD [Reference Biederman, Ball, Monuteaux, Mick, Spencer and Mc52]. It is plausible that the additional impact of hormonal fluctuations on the female body and brain account for (some of) the observed sex differences. Combined, these findings support the hypothesis that cyclical hormonal fluctuations, especially in oestrogen, can exacerbate ADHD symptoms in women and influence treatment response.

Assessment

To provide a more comprehensive perspective and contextualise our findings, we also make recommendations for assessment and treatment based on our clinical experience and other key articles related to this topic. This broader approach enables us to address several additional themes relevant to female-specific ADHD research and clinical practice.

When evaluating ADHD for the first time, clinicians and researchers should routinely ask about the first day of the last menstruation and cycle length, or use of hormones [Reference Schmalenberger, Tauseef, Barone, Owens, Lieberman and Jarczok53]. With this information in mind, it can be determined whether the woman is in the follicular or luteal phase of her menstrual cycle. The relationship between the current endorsement of symptoms and the current menstrual cycle phase may give insights into why the symptoms are particularly severe at a specific time: typically, ADHD and mood symptoms are most intense around ovulation and in the late luteal phase. They diminish after the first few days of menstruation [Reference Dorani, Bijlenga, Beekman, van Someren and Kooij31, Reference de Jong, Wynchank, van Andel, Beekman and Kooij33]. Also, the timing of the evaluation with regard to the menstrual cycle phase may shed light on current treatment response and guide dosing of psychostimulant medication.

As described earlier, ADHD commonly co-exists with symptoms of PMDD [Reference Dorani, Bijlenga, Beekman, van Someren and Kooij31]. All women with ADHD should be screened for PMDD, and to identify a possible diagnosis, women should complete a PMS calendar for at least 2 months. By tracking ADHD and mood symptoms in relation to their menstrual cycle, they may gain insights into the impact of the various menstrual phases on fluctuating symptom severity of mood symptoms. We routinely include this in the psychotherapy group we have designed for with ADHD and PMDD [Reference de Jong, Wynchank, Michielsen, Beekman and Kooij51]. During their ongoing treatment and in research studies, women with ADHD should continue to use the PMS calendar or smart phone applications for reporting cycle phase [Reference de Jong, Wynchank, Michielsen, Beekman and Kooij51]. These tools will improve the reliability and validity of clinical and research findings. Monitoring symptom fluctuations per menstrual cycle phase may also be relevant to other (co-existing) psychiatric disorders, such as autism and bipolar disorder [Reference Hinshaw, Nguyen, O’Grady and Rosenthal1, Reference Handy, Greenfield, Yonkers and Payne32].

Female-specific norms may need to be developed for the different phases of the menstrual cycle to prevent what we have noted from clinical experience: underdiagnosis of ADHD in the follicular phase of the cycle and undertreatment in the luteal phase. We recently published an article with several colleagues using this as a starting point [Reference Kooij, de Jong, Agnew-Blais, Amoretti, Bang Madsen and Barclay54].

While the average age for menopause is 51 years, a genome-wide association study showed that women with ADHD may have an earlier menopause [Reference Demontis, Walters, Martin, Mattheisen, Als and Agerbo55], making them vulnerable to the vasomotor (thermoregulatory problems such as hot flushes and night sweats), somatic (palpitations, fatigue, joint pain, insomnia), psychological (depressed or anxious mood, irritability), and genitourinary symptoms (vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, urinary frequency, urgency, or incontinence). Specific attention should be paid to sleep in this population, as women and men with ADHD have chronic sleep problems, which often worsen in women during (peri)menopause [Reference Fuller-Thomson, Lewis and Agbeyaka56]. Disrupted sleep can worsen concentration and mood problems. Once (peri)menopausal symptoms occur, care should be taken to distinguish new-onset “brain fog” and cognitive problems from an exacerbation of previously undiagnosed ADHD but present from childhood.

Monitoring and treatment

The two pillars of gold standard ADHD treatment are psychological and pharmacological interventions. Both warrant a female-specific approach [Reference Hinshaw, Nguyen, O’Grady and Rosenthal1].

The menstrual cycle in women (with ADHD) needs to be discussed openly, breaching taboo. Premenstrual depressive symptoms worsen self-esteem and clinical outcomes time after time, if they remain unaddressed [Reference Attoe and Climie4]. In addition, for women who lack a sense of timing and an overview, gaining insights into the fluctuation of ADHD symptoms is a particularly valuable first step. Simultaneously, the effectiveness of ADHD medications should be monitored across the cycle and, if necessary, adjusted [Reference de Jong, Wynchank, van Andel, Beekman and Kooij33]. We base this suggestion on our case study; however, a randomised controlled trial is necessary to have more certainty on the efficacy of premenstrual psychostimulant dose adjustment. When there is a comorbid diagnosis of PMDD, our suggestion of an SSRI (in the luteal phase only or preferably continuously) is supported by the literature [Reference Alpay and Turhan57]. Other studies suggest a combined oral contraceptive, particularly where somatic symptoms predominate [Reference Freeman58]. We favour oral contraceptive use, without a stop week, to stabilise hormone levels, based on our clinical experience. However, this has not been supported by the literature, and more research is needed [Reference Eisenlohr-Moul, Girdler, Johnson, Schmidt and Rubinow59].

For monitoring of symptoms during the menstrual cycle, questionnaires as cited in Table 1 are useful for ADHD, PMDD, depressive symptom severity, and rating sleep quality to track fluctuating symptoms. Systematic monitoring is important because it enables identification of cyclical patterns in symptom exacerbation, thereby supporting more precise diagnosis and facilitating individualised treatment adjustments, such as optimising medication timing or dosage. This approach also encourages patients to recognise and understand their own symptom fluctuations, enhancing engagement and communication with clinicians.

In the case of peri/postnatal depression, in addition to support and psychoeducation, SSRIs, certain stimulants, or other therapies can be used [Reference Kittel-Schneider, Quednow, Leutritz, McNeill and Reif60, Reference Bang Madsen, Bliddal, Skoglund, Larsson, Munk-Olsen and Madsen61], but full discussion of these is beyond the scope of this report.

For women who have compensated for their ADHD symptoms since childhood, sleep and executive function difficulties arising in the (peri)menopause may unmask an underlying ADHD diagnosis, in which case a combination of hormone therapy and ADHD medication is warranted. In addition, for (peri)menopausal exacerbation of ADHD, low mood, sleep, and somatic symptoms [Reference Young, Adamo, Asgeirsdottir, Branney, Beckett and Colley7, Reference Quinn and Madhoo8, Reference Camara, Padoin and Bolea30, Reference Dorani, Bijlenga, Beekman, van Someren and Kooij31], CBT [Reference Green, Donegan, Frey, Fedorkow, Key and Streiner62], and antidepressants such as SSRIs, SNRIs [Reference Guthrie, LaCroix, Ensrud, Joffe, Newton and Reed63], and bupropion can be considered. Also, mood, vasomotor and somatic symptoms, sleep disturbances, and sexual dysfunction during the (peri)menopause may improve with menopausal hormone replacement therapy [64]; however, this has not been specifically studied in women with ADHD. Hormone replacement is not currently approved for the treatment of (peri)menopausal depression, because of insufficient evidence, although a recent retrospective study of peri- and postmenopausal women suggested significant improvement of mood using Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) [Reference Glynne, Kamal, Kamel, Reisel and Newson65], but placebo-controlled studies are necessary. The “new” onset of executive function difficulties in the (peri)menopause should be investigated for underlying, undiagnosed ADHD.

Reflections on protocol development and implementation

Developing this female-specific ADHD protocol highlighted several challenges, particularly the limited availability of research or validated tools sensitive to hormonal fluctuations and the need for greater awareness among clinicians regarding the impact of the menstrual cycle on ADHD symptoms. Ensuring consistent engagement with symptom and cycle tracking can also be difficult for women with ADHD, who may already struggle with organisation and motivation.

Despite these challenges, implementing such a protocol offers clear benefits. It enables more accurate assessment and tailored treatment by accounting for cyclical symptom changes. It empowers women to understand and manage their condition better, possibly even improving treatment adherence. However, practical barriers such as the need for additional clinician training and the variability of menstrual cycles, especially in younger women, must be considered.

From a developmental perspective, while this protocol is primarily designed for adult women, its principles can be adapted for use in adolescent girls, particularly from the onset of menarche. Early incorporation of menstrual cycle tracking and symptom monitoring could facilitate earlier identification of ADHD and its comorbidities in girls, who are often underdiagnosed. Future research should focus on validating these approaches in younger populations and exploring how hormonal context can inform early intervention strategies, ultimately improving outcomes for females across the lifespan.

Conclusion

The theoretical context presented here serves as a starting foundation for addressing the unique challenges faced by women with ADHD in clinical practice and research. Recognising the impact of the female hormones on the symptom severity of ADHD, mood, and potentially other disorders, is essential for advancing our understanding of ADHD in women. Future research should prioritise including the menstrual cycle phase in investigations and clinical treatment, screening for premenstrual and postpartum depression in women with ADHD, as well as screening for early-onset (age <45 years) and severe (peri)menopausal symptoms, to develop more effective treatment strategies for women with ADHD. Additionally, efforts to adapt and validate these approaches for girls and younger females could facilitate earlier identification and intervention, leading to better care for women and girls with ADHD across the lifespan. Finally, while this study focuses predominantly on the impact of biological sex, the impact of gender roles and gendered psychosocial expectations should not be neglected.

Competing interests

DW and SJJSK declare that they have a financial interest in the ADHD Powerbank, an online video bank with educational, scientific videos about adult ADHD.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.