Introduction

Voters often express dislike for negative campaigning, but the fact that it continues to be a widespread practice across the democratic world suggests that political elites see it as a useful campaign tactic (Belt Reference Belt, Holtz-Bacha and Just2017). Previous work focusing on the US context has shown that negative ads that attack an opponent can have a meaningful impact on voter attitudes, but it is not a tactic that elites can employ without risk, as there is the potential for backlash or boomerang effects against the attacking candidate (Garramone Reference Garramone1984; Sanders and Norris Reference Sanders and Norris2005; Walter and van der Eijk Reference Walter and van der Eijk2019). Further, while the negative campaign literature is voluminous, it has been so focused on the United States that it is uncertain whether the findings generalise to other countries (Nai Reference Nai2020) because how voters interpret the extent to which a message is truly negative may depend on the standard political discourse in that country (Milazzo and Ryan Reference Milazzo and Ryan2024). Even within the United States, the particulars of the negative ads can shape the extent to which voters see an ad as actually being ‘negative’ – the civility and topical focus of the ad can shape perceptions of negativity (Dowling and Krupnikov Reference Dowling and Krupnikov2016). After decades of research, the answer to the question of how negative campaigning affects voters seems to be, ‘It depends’.

The conditional effect of negative campaigning means that there is still much we do not understand despite the large number of studies that already exist. In this paper, we draw on data from the OpenElections Project (www.openelections.co.uk) to create three treatments that reflect real-world negativity in British election leaflets. Our three treatment conditions leverage variation in the degree of negativity: (1) attacks focusing only on personal characteristics of an opponent, (2) attacks focusing on policy positions of the opponent, and (3) attacks that incorporate both the policy positions and the personal characteristics of the opponent. The treatments allow us to create distinct estimates of perceived negativity by comparing attacks that include a personal element and those where the personal element is omitted. We also leverage the message variation to estimate how these different types of messages affect voters’ feelings towards both the attacker and the target of the message. Finally, to provide additional nuance to our results, we disaggregate the above analyses by partisanship to explore how different types of voters react to negative messages. Our work adds to the growing literature demonstrating the importance and efficacy of local campaign activities in British elections (e.g., Cutts Reference Cutts2014; Denver, Hands, and MacAllister Reference Denver, Hands and MacAllister2004; Fisher, Cutts, and Fieldhouse Reference Fisher, Cutts and Fieldhouse2011; Pattie et al. Reference Pattie, Johnston and Fieldhouse1995, Trumm and Sudulich Reference Trumm and Sudulich2016).

The experiment in this paper differs from existing research in three important ways. First, our experiment differs from previous studies because it focuses on a contrast ad instead of a purely negative ad. This is important for the specific content we are examining: the difference between personal and policy attacks. Candidates will disclose personal information in an attempt to create positive parasocial relationships (McGregor Reference McGregor2018). Existing studies that find a backlash to personal attacks cannot account for the possibility that mentioning the positive personal traits of the sponsor will shield them from backlash.

Second, our case is Great Britain; this is a context where negative campaigning is common, but the norms surrounding it are very different from the most common case studied, the United States. This is especially important since the perceived civility and negativity of an attack affect the efficacy of a negative ad (Brooks and Geer Reference Brooks and Geer2007; Mattes and Redlawsk Reference Mattes and Redlawsk2014). Within the context of British politics, there is great variation in the extent to which candidates personalise their campaigns, with some candidates focusing primarily on messages related to the parties’ platforms (Townsley, Trumm, and Milazzo Reference Townsley, Trumm and Milazzo2022). As a result, specific personal messages may strike some voters differently than they do in the United States, where personalisation of campaigns is more common.Footnote 1

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, our experiment examines the effects of negative campaigning using a largely ignored medium: the election leaflet. Despite the leaflet being a ubiquitous form of campaigning for parties throughout the world, the research has almost exclusively focused on whether partisan leaflets mobilise voters (see e.g., Niven Reference Niven2006 in the USA and Townsley Reference Townsley2025 in Britain). Almost no attention has been paid to whether leaflets influence how voters perceive candidates.Footnote 2 The medium may matter, as voters’ affective responses to the negative messages contained in leaflets may differ from other ads since television and radio are able to influence message recipients using music and vocal tones in ways that the static text of leaflets cannot (Brader Reference Brader2006; but see Huddy and Gunnthorsdottir Reference Huddy and Gunnthorsdottir2000).

Our results provide several important implications for British elections and the study of campaign negativity more broadly. Namely, we find that personal attacks are perceived as more negative, while attacks on an opponent’s policy positions have little impact on voters. Moreover, we find that voter perception of negativity is important in affecting political attitudes and that there are significant boomerang effects for engaging in personal attacks, with attacker favourability declining most significantly among non-partisans and out-party respondents. Our paper contributes to this literature in several ways: (1) we offer novel findings related to British voters’ perception of negativity, the impact of different degrees of negativity, and how perception and effect are linked (2) we provide simultaneous estimates of both attacker and target favourability that allow us to directly observe a possibly null or backlash effect of negativity, and (3) we incorporate partisanship into our analysis, which has rarely been done outside of the US context.Footnote 3 Taken together, the multifaceted nature of our analysis allows us to offer nuanced insights that are new to this literature and will be of interest to academics, prospective parliamentary candidates, and political strategists.

Previous literature and theory

The ambiguous effects of campaign negativity

When scholars refer to a political campaign engaging in negative advertising, they typically mean that the message involves the ad’s sponsor criticising their opponent (Geer Reference Geer2006). Any critical message is negative, while types of negative messages are categorised based on other dimensions of the advertisement – for example, the tone of the criticism or the specific focus of the message (Brooks and Geer Reference Brooks and Geer2007). Of course, many campaign communications contain multiple messages with many appeals to voters, both criticising the opponent and praising the sponsor; these types of campaign communications are called ‘contrast’ ads (Fowler and Ridout Reference Fowler and Ridout2013).

The goal of negative ads is clear: to create a poor impression of the attack’s target in the minds of voters, thus causing them to prefer the attacker (Kaid Reference Kaid1997) or, if the voters prefer the opponent, to at least get them to abstain from voting (Krupnikov Reference Krupnikov2011). Contrast ads might have dual benefits for sponsors by creating a favourable impression of the attacker while harming the image of the opponent. At the same time, there are concerns that the negativity and potential incivility associated with negative ads could have effects beyond candidate evaluations. The fear is that politics having a generally negative tone could lead citizens to lower their political efficacy, trust in government, and feelings about the country (Lau, Sigelman, and Rovner Reference Lau, Sigelman and Rovner2007).

The effects of negative campaigns have been widely studied for decades using both experimental methods (e.g., Brader Reference Brader2006; Haas, Hassan, and Morton Reference Haas, Hassan and Morton2020; Krupnikov and Piston Reference Krupnikov and Piston2015) and negativity in ads during actual campaigns (e.g., Freedman and Goldstein Reference Freedman and Goldstein1999; Jackson and Carsey Reference Jackson and Carsey2007; Ridout and Walter Reference Ridout and Walter2015; Walter, van der Brug, and van Praag Reference Walter, van der Brug and van Praag2014). The dependent variables studied include vote choice (e.g., Krupnikov Reference Krupnikov2012; Somer-Topcu and Weitzel Reference Somer-Topcu and Weitzel2022), turnout (e.g., Ansolabehere and Iyengar Reference Ansolabehere and Iyengar1995; Finkel and Geer Reference Finkel and Geer1998; Krasno and Green Reference Krasno and Green2008), political efficacy (e.g., Ansolabehere et al. Reference Ansolabehere, Iyengar and Simon1994; Dardis, Shen, and Edwards Reference Dardis, Shen and Edwards2008), and many more. This literature has produced a diverse range of findings (see Dowling and Krupnikov Reference Dowling and Krupnikov2016, Haselymayer Reference Haselmayer2019, Lau, Sigelman, and Rovner Reference Lau, Sigelman and Rovner2007 for comprehensive overviews). Notable US studies showing that negative messaging can decrease voter preferences for the target include Kahn and Kenney (Reference Kahn and Kenney2004), Merritt (Reference Merritt1984), and Pinkleton (Reference Pinkleton1997). However, in a succinct demonstration of the complex nature of this literature, each of these works also finds evidence that negativity harms voter evaluations of the attacker.

Additionally, more recent studies in multiparty systems show that negative messaging has the potential to harm both the target and the attacker (Duggan, Crepaz, and Kneafsey Reference Duggan, Crepaz and Kneafsey2024) and may largely benefit idle third-party candidates (Galasso, Nannicini, and Nunnari Reference Galasso, Nannicini and Nunnari2023). Some analyses have suggested that the primary outcome of negative messaging is backlash or ‘boomerang’ effects against the attacker (Garramone Reference Garramone1984; Sanders and Norris Reference Sanders and Norris2005), while others such as Kaid (Reference Kaid1997) find that negativity can damage the target without backfiring on the sponsor. Ansolabehere and Iyengar (Reference Ansolabehere and Iyengar1995) and Ansolabehere et al. (Reference Ansolabehere, Iyengar and Simon1994) have suggested that negative messaging can depress turnout (or ‘demobilise’ voters), though later works such as Brooks (Reference Brooks2006), Finkel and Geer (Reference Finkel and Geer1998), and Goldstein and Freedman (Reference Goldstein and Freedman2002) have challenged these findings.

If a summation of this vast literature is possible, then it must be that the effects of negative campaigns are highly conditional on the types of messages and the election context (Dowling and Krupnikov Reference Dowling and Krupnikov2016). In this vein, previous work has shown that effects can be dependent on whether the message triggers an emotional reaction (Brader Reference Brader2006), whether an attack is seen as unprovoked or a retaliation (Lau and Rovner Reference Lau and Rovner2009), the ideological proximity of the target to the attacker (Ceron and d’Adda Reference Ceron and d’Adda2016), the presence of viable and ideologically proximate alternative candidates (Duggan, Crepaz, and Kneafsey Reference Duggan, Crepaz and Kneafsey2024; Mendoza, Nai, and Bos Reference Mendoza, Nai and Bos2024), as well as respondent attributes such as political ideology (Jung and Tavits Reference Jung and Tavits2021) and personality traits (Nai and Maier Reference Nai and Maier2021; Nai and Otto Reference Nai and Otto2021). Importantly for this paper, these conditional effects of negativity are themselves conditioned by the country in which the study takes place. For example, Nai et al. (2024) find that women candidates who go negative are especially likely to be ‘punished’ by voters in countries with low levels of gender equality in government. Hence, the fact that the campaign negativity literature largely examines the effects of television ads in the United States means our understanding of campaign negativity around the world is still limited despite the decades of research devoted to the topic.Footnote 4

These are obvious limitations for a research area where the effects are dependent on the elements of the message, the campaign context, and the media in which campaign communications are delivered. Foremost, the election systems and laws governing campaigning differ across countries, and negative campaigning is simply more common in the United States than in many other democracies (Fowler and Ridout Reference Fowler and Ridout2013; Walter Reference Walter2014). One country where voters should expect significant levels of negativity is the United Kingdom, where negativity is a common campaign tactic even if party leaders feign outrage at the negativity in British politics (Duggan and Milazzo Reference Duggan and Milazzo2023; Walter Reference Walter2014). However, the OpenElections archive suggests that the type of negativity in British campaigns is distinct from that found in US politics. Negative messaging in British politics can be considered tame by US standards, and this is particularly the case for personal attacks. For example, the seminal work on US elections by Brooks and Geer (Reference Brooks and Geer2007) uses a treatment (designed to be a realistic representation of US campaigning) that attacks a candidate based on their history of several failed marriages. Attacks on family life or other intimate personal issues are essentially non-existent in British campaigns, with personal criticism being largely focused on whether the candidate has ties to the constituency, their educational background, or their career. Additionally, Brooks and Geer (Reference Brooks and Geer2007) only find a difference between negativity about issues and traits when the tone of the attack is uncivil, but different political cultures will differ in what it takes to cross the line from civil to uncivil. As such, it is necessary to reconceptualise what constitutes personal or uncivil attacks in British politics and test the effects of these types of messages.Footnote 5

One similarity with the United States – but still different from many European countries – is that national politics in Britain, though not local politics in the home nations beyond England, is dominated by two parties. For these reasons, some of the lessons from the American context might apply to British politics. At the same time, there are major differences in the campaign contexts of Britain and the USA. Most notably, campaigns in Britain utilise a comparatively ‘tame’ type of negativity, take place over a shorter period, are without paid television advertising, and place parties, rather than candidates, at their centre. These differences make it difficult to ascertain whether the current negativity literature generalises to the British case.

Reconceptualising policy and personalisation for campaign leaflet communication

Our study concentrates on the most common form of campaign communication in British general elections – the election leaflet.Footnote 6 Election leaflets remain the most common form of campaign contact in British general elections, as political parties and their candidates spend more money on designing and distributing election leaflets than on any other campaign activity.Footnote 7 Moreover, there is clear evidence that voters engage with leaflets. According to the British Election Study Internet Panel (BESIP), almost 90 per cent of respondents who recalled being contacted by a political party after the 2024 General Election indicated they received at least one leaflet during the campaign. The BESIP also suggests there is a reasonable level of active voter interaction with campaign leaflets. Of the respondents who received a leaflet, 52 per cent reported that they had read a campaign leaflet, letter, text, or email during the campaign. If we look at those respondents who reported that they voted in the 2024 General Election, the figure rises to 56 per cent (Fieldhouse et al. Reference Fieldhouse, Green and Evans2021). Thus, voters not only remember receiving election leaflets, but they also recall reading them.

Leaflets provide a great source of heterogeneity in campaigns across constituencies. This is true both in form – some leaflets are postcards while others are essentially short magazines – and substance. Because of this variation, campaign leaflets are an important form of campaign communication to study as scholars increasingly see the important role of campaigns within British constituencies, despite all the focus on the parties and their leadership during the campaigns (see e.g., Duggan and Milazzo Reference Duggan and Milazzo2023; Fisher Reference Fisher, Robinson and Fisher2005; Johnston et al. Reference Johnston, Pattie and Cutts2012; Milazzo, Trumm and Townsley Reference Milazzo, Trumm and Townsley2021, Shephard Reference Shephard2007).

Obviously, there are many potential forms of negativity in leaflets that we could investigate; this study looks at effects dependent on whether the negativity is focused on the personal attributes of the candidates or their policy positions. In their study of various dimensions of campaign negativity, Brooks and Geer (Reference Brooks and Geer2007) refer to this as the ‘focus’ of the message.Footnote 8 This is arguably an understudied dimension of negative advertising, as candidates even in party dominated systems have attempted to incorporate what Van Aelst, Sheafer, and Stanyer (Reference Van Aelst, Sheafer and Stanyer2012) refer to as the ‘privatisation’ of the candidate – that is, an increasing attention to the candidate as a person rather than the holder of a particular political office.Footnote 9 Indeed, in recent British elections candidates have attempted to craft their campaign messages to highlight their personal strengths (Milazzo and Townsley Reference Milazzo and Townsley2020; Trumm et al. Reference Trumm, Milazzo and Duggan2023), and parties have chosen candidates with stronger local ties to a constituency (Butler, Miori, and Ford Reference Butler, Miori and Ford2025) despite the importance of party-focused campaigning in the UK’s electoral context.

While the personalisation of political campaigns has continued to increase in the 21st century (McAllister Reference McAllister, Dalton and Klingemann2007), individual politicians have always had incentives to present themselves in ways that suggest they are similar to their constituents or, at a minimum, understand their constituents and empathise with them (Fenno Reference Fenno1978). The introduction of television (a visual medium) and then social media (an interactive medium) has only increased the appeals centred on personal characteristics (McGregor Reference McGregor2018; Van Aelst, Sheafer, and Stanyer Reference Van Aelst, Sheafer and Stanyer2012). Members of parliament can present themselves this way when they meet with constituents; incumbents and challengers can create personalised posts on social media. But these methods only reach the small percentage of deeply involved voters who pay outsized attention to politics (Krupnikov and Ryan Reference Krupnikov and Ryan2022).

The primary means for candidates to present themselves to voters who are less engaged is through the unsolicited campaign communications that they send to large numbers of voters – i.e., their leaflets. These leaflets, however, are a relic of a campaigning era that predates the personality-driven mass media of the current age, potentially causing voters to process the personal information contained in leaflets differently than they would television ads or social media posts. An important way UK election leaflets differ from US television ads, which has been the focus of the negativity research, is that leaflets include a wide variety of messages in a single leaflet. While it makes sense in the context of US elections to study positive and negative ads separately, that does not reflect the reality of many UK election leaflets. Hence, it is important to study campaigning negativity in the context of contrast ads that attempt to highlight differences in policy and personal traits rather than simply attacking an opponent’s policies or personal traits.

Candidates may believe that a mix of positive and negative messages may shield them from the documented backlash that comes from attacks on personal traits in purely negative ads. The hope would be that positive personalisation leads to increased positive affect on the part of voters towards the candidate, and voters who have positive affect towards a candidate give those candidates more leeway (Piston et al. Reference Piston, Krupnikov and Milita2018). This logic makes sense in the context of a long US election campaign in which the effects of negative ads depend on their timing (Krupnikov Reference Krupnikov2011). If a candidate can increase positive affect via personalisation early in the campaign with a series of positive messages, there might be more leeway later in the campaign for less desirable behaviours.

This changes, however, in the shorter UK campaign context with the positive and negative messages appearing on the same leaflet. A candidate saying, ‘I am just like you’ may attract voters if repeated enough times to have its maximal effect (Lipsitz and Padilla Reference Lipsitz and Padilla2024). If that positive message is immediately followed with a statement saying, ‘My opponent is not one of us’, then the leaflet could fail to lower voters’ evaluations of the opponent while increasing the perception that the attacker is engaging in unfair campaigning. The positive messaging in the first sentence has not had enough time to become the voter’s primary association with the candidate, and thus the negative message operates the same as a purely negative message that voters might see in other campaign contexts.

Evidence from other contexts suggests that negativity containing attacks on the personal life of a candidate can affect voters differently when compared with other types of attacks (Brooks and Geer Reference Brooks and Geer2007; Kahn and Kenney Reference Kahn and Kenney1999; Nai and Maier Reference Nai and Maier2021). Further, while voters will expect candidates to debate their policy positions, messages related to personal characteristics of the candidates may be perceived as inappropriate or irrelevant (Fridkin and Kenny Reference Fridkin and Kenney2011). This may be especially true in the British context, where negative attacks are typically focused on parties and their leadership and where it is seen as more negative to mention a candidate by their name rather than their party (Milazzo and Ryan Reference Milazzo and Ryan2024). This leads us to our first hypothesis:

H1: Attacks including personal elements will be perceived as more negative than policy-based negative messages and positive messages.

The fact that debates in British politics focus on parties as a whole or party leaders in particular leads to a greater risk that personal messages will be seen as more negative. The candidate who attacks their opponent’s personal characteristics might damage themselves more than they damage their opponent. Backlash against the sponsors of negative ads is well documented (Galasso, Nannicini, and Nunnari Reference Galasso, Nannicini and Nunnari2023; Roese and Sande Reference Roese and Sande1993; Walter and van der Eijk Reference Walter and van der Eijk2019; but see Nai and Maier Reference Nai and Maier2021 for a discussion of how backlash effects are not uniform among voters). Our treatments, like leaflets in British politics generally, do not attack the candidate on personal dimensions that would be considered completely out of bounds – for example, we do not discuss intimate details of the candidate’s life. At the same time, voters may lower their evaluation of the attacking candidate because they believe the candidate is not focused on issues that affect the voter’s lives.

On the other hand, anything a candidate mentions sets the campaign agenda and primes the voters to decide based on that dimension (Milita et al. Reference Milita, Simas and Ryan2017). As a result, if a candidate contrasts their personal characteristics with their opponent’s characteristics, then the voters may decide that the election should be decided based on the personal characteristics of the candidates. And if the attempted personalisation by the leaflet’s sponsor is effective, then the voters should have a more positive impression of the sponsor than the opponent. This may shield the sponsor from backlash as voters give candidates greater leeway when they have positive affect towards a candidate (Piston et al. Reference Piston, Krupnikov and Milita2018).

But this is where the specific medium of the leaflet matters because there is reason to doubt the personalisation of leaflets will have the desired effect of inoculating the sponsor from criticism. Personalisation is meant to aid politicians by creating a ‘parasocial’ relationship between the politician and voters (McGregor Reference McGregor2018). Voters are supposed to feel that they identify with politicians they have never actually met. This may work with television, which actively engages all the senses (Druckman Reference Druckman2003; Graber Reference Graber1990), or social media because the candidates can interact with voters (Kenski, Kim, and Jones-Jang Reference Kenski, Kim and Jones-Jang2022; McLaughlin and Macafee Reference McLaughlin and Macafee2019). The major concern campaign professionals have about direct mail appeals (like leaflets) in the US case is that they are less engaging when compared with activities such as face-to-face canvassing (Gerber and Green Reference Gerber and Green2000; see also Townsley Reference Townsley2025 for discussion of such effects outside the US). Hence, creating this parasocial relationship is less likely with leaflets than with other media. As a result, candidates may not be able to shield themselves from the backlash of going negative even if they attempt to create positive feelings via personalisation.

In sum, candidates might use tactics such as personalisation and contrast messaging – appeals that include negative messages about their opponents – to create a positive impression of themselves paired with a negative impression of their opponent. The risk with these tactics has always been that voters not only lower evaluations of the opponent due to the content of the messages, but also the attacker, because the attacker is seen as engaging in unfair campaigning (Kahn and Kenney Reference Kahn and Kenney2004). The risk is especially high with personalised messages because many voters find the discussion of those types of traits irrelevant to the politician’s job (Fridkin and Kenney Reference Fridkin and Kenney2011). The positive parasocial relationship that personalisation is meant to create with voters might allow the candidate more leeway (McGregor Reference McGregor2018; Piston et al. Reference Piston, Krupnikov and Milita2018). But the ubiquitous form of media in British elections, the campaign leaflet, lacks the vividness and affordances to create the type of parasocial relationship and warm feelings that would shield them from the backlash. This discussion suggests two hypotheses:

H2: Attacks including personal elements will not affect the favourability of the target candidate.

H3: Attacks including personal elements will reduce the favourability of the attacking candidate when compared to policy-based negative messages and positive messages.

As we discussed earlier, the literature on the persuasive power of partisan leaflets is limited. As a result, there have not been any studies that look at variables that might condition the effects of negative messaging. A key moderating variable that has been ignored is the partisan match between the ad’s sponsor and the voter receiving the message. In fact, Doherty and Adler (Reference Doherty and Scott Adler2014), in one of the only studies to look at how partisan leaflets affect voter’s perceptions of candidates, focused on voters who were not affiliated with any political party.

The literature on partisan motivated reasoning suggests that voters will often process information through the lens of their allegiance to a given political party (Bolsen, Druckman, and Cook Reference Bolsen, Druckman and Cook2014; Leeper and Slothuus Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014). Partisan-motivated reasoning is often implicitly discussed as if it is biasing individuals away from an objective truth, but it also prevents voters from being overwhelmed by the constant flow of messages they receive (Cotter, Lodge, and Vidigal Reference Cotter, Lodge, Vidigal, Suhay, Gofman and Trechsel2020). It does not make sense for copartisans to suddenly turn on a candidate just because they hear something negative about the candidate, as processing information in this way would result in an inability to ever make a decision. This is especially true with biographical information since most would view these messages as irrelevant even in a non-partisan contest. As a result, when the target of the attack is a copartisan, there is absolutely no reason to believe they will be moved by personal attacks.

A similar logic applies to the attacking candidate. The norm in British politics has been to attack parties and leaders instead of particular candidates. It is obviously a violation of this norm to attack a candidate based on their personal traits and their backgrounds. As a result, this is why most voters will lower their favourability towards the attacker. On the other hand, copartisans of the attacker will be motivated to support the tactics of a candidate who shares their partisan identity (Claassen and Ensley Reference Claassen and Ensley2016; Claassen, Ensley, and Ryan Reference Claassen, Ensley and Ryan2025). In fact, Redlawsk (Reference Redlawsk2002) shows that partisan-motivated reasoners engage in so much counterarguing that they actually increase the favourability of candidates from their party when they receive negative information about them. In the British context, the negative campaigning on personal information may be such a norm violation that favourability is not increased but is simply stable. Our expectations, therefore, are more aligned with previous work showing that voters perceive attacks by their preferred candidates as less negative than when attacks are carried out by other parties (Haselmeyer, Hirsch, and Jenny Reference Haselmayer, Hirsch and Jenny2020). That is, we expect that attacker favourability will be unaffected for both attacker and target copartisans, as effects are largely baked in for these respondents.Footnote 10 As such, we need to moderate our previous expectations, as not all voters will respond to the personal attacks in the same way.

H4: Attacker favourability will fall for out-party and non-partisan respondents but will be unaffected for both attacker and target copartisans.

Experimental design, data, and methods

In line with the seminal taxonomy outlined by Brooks and Geer (Reference Brooks and Geer2007), this paper is interested in two important dimensions of campaign messages. Namely, we explore message tone (positive vs. negative) and message focus (personal vs. policy).Footnote 11 Using these two dimensions, we explore the effects of different types of negative messaging on three outcome variables: (1) the perceived negativity of the attack, (2) the favourability of the attacking candidate, and (3) the favourability of the target candidate. To do so, we conduct a novel online population-based survey experiment. The experiment is designed to mirror a scenario that voters might reasonably experience during a general election campaign. Respondents were exposed to a combination of images modelled on real election communications distributed by two candidates (one Labour candidate and one Conservative candidate) contesting a hypothetical seat.Footnote 12

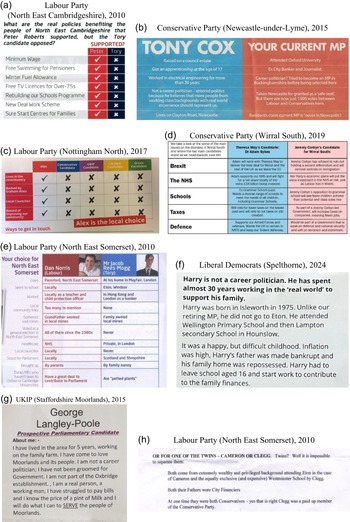

Exemplar leaflets used in the experimental design

To ensure that our leaflet represents a realistic example voters might expect to receive in a general election campaign, we rely on the OpenElections project (www.openelections.co.uk) – an original dataset of content-coded leaflets from British general elections between 2010 and 2024. With respect to candidate-focused negativity, we observe two types of messages: messages where an opposing candidate is referred to more generally and those where the opponent is mentioned by name. Whilst ‘naming and shaming’ was more common during the 2010 General Election campaign in the aftermath of the 2009 expenses scandal, targeting an opposing candidate without using their name remains the most common approach to candidate-on-candidate negativity that we observed in the leaflets across the 4 general elections. Therefore, we use this approach as a model for our vignettes. In Figure 1A–H, we present examples of how candidates target their opponents in their communications. These examples illustrate how candidates use both personal and issue-based messages to try to undermine their opponent(s).

Figure 1. Examples of candidate negativity from actual election leaflets. Treatments in our experiment most closely match example b.

As evidenced by Figure 1, we note a persistent attack type in the leaflet archive that attempts to paint some candidates as out-of-touch elites. Many of these attacks draw on personal information such as attending elite schools or universities (e.g., Eton and Oxford), being career politicians or bankers, being absent from the constituency, and/or having no local ties to the constituency. Such barrages are intended to appeal to the social identity of voters and to capitalise on feelings of animosity towards the out-group member – the targeted politician (Huber Reference Huber2022). This attack type may be well designed to achieve its intended goal; Campbell and Cowley (Reference Campbell and Cowley2014) find that British voters may prefer candidates that do not have a university degree and that candidates living outside the constituency are at a significant disadvantage. We design the personal attacks in our treatment to closely resemble these real-world examplesFootnote 13 .

As noted earlier, these examples may not be considered overtly negative by US standards, but they constitute a large class of personal attack types in British politics. Similarly, we draw on the leaflet archive to present our policy-based attacks. In keeping with our interest in constituency-level campaigns, we choose issues that are local and ideologically neutral (i.e., we would expect broad support for the highlighted issues in both the electorate and amongst the candidates). Accordingly, our vignettes were designed to closely approximate how voters would encounter leaflets in the real world.Footnote 14 This approach provides the experimental design with an element of mundane realism, which improves our ability to generalise findings from the experiment (Kinder and Palfrey Reference Kinder and Palfrey1993).

Experimental stimuli

Our experiment used a 2 x 4 design, in which each respondent was exposed to a vignette composed of one leaflet image from the current MP and one leaflet from the non-incumbent challenger. While the seat is always a Labour/Conservative battleground, we vary the party of the incumbent and the challenger. Finally, as previous research suggests that incumbent MPs are less likely to employ negative messages (Duggan and Milazzo Reference Duggan and Milazzo2023),Footnote 15 the leaflet image for the incumbent MP is always neutral – i.e., it includes no negative or positive statements. On the other hand, the challenger leaflet employs four possible frames:

-

1) a control (positive) frame, where the challenger focuses on the merits of his own policy and personal attributes;

-

2) a contrast (negative) policy frame, where the challenger targets his opponent’s policy positions in addition to the positive mentions of their own policy and personal attributes;

-

3) a contrast (negative) personal frame, where the challenger targets his opponent’s personal attributes in addition to the positive mentions of their own policy and personal attributes;

-

4) a contrast (negative) personal/policy frame, where the challenger targets both his opponent’s policy and personal attributes in addition to the positive mentions of their own policy and personal attributes.

The policy positions and personal attributes highlighted/attacked are kept constant across the treatmentsFootnote 16 . By holding both the neutral target frame and the positive elements from the attacker message constant across vignettes, we can isolate and cleanly estimate treatment effects for each of our three negativity frames while presenting the message in a way that closely hues to real contrast negative messages used in British election leaflets. As we stated earlier, having the treatment messages incorporate both positive (about the sponsor) and negative (about the opponents) statements allows us to test the way personalised politics is increasingly practised; an attempt to create a positive image of the personal life of the sponsor while then attempting to lower the image of the challenger.

The result is 8 possible treatments – four possible frames for a Conservative attacker (with a Labour target) and four possible frames for a Labour attacker (with a Conservative target). The full design allows us to estimate the effect of policy-based attacks, personal attacks, and both personal and policy attacks compared to a message that contains no attacks, which in turn allows us to test our hypotheses regarding the impact of different types of attacks. Additionally, we compare each of the three treatment conditions to each other. This allows us greater insight into whether personal attacks have a different impact than policy attacks (e.g., comparing the treatment containing both attack types to the two treatments containing only one attack type provides a further test on whether personal attacks are perceived differently and have different effects). We also split the analysis by the relationship of the respondent’s partisanship with the candidates’ partisanship. That is, we analyse the results separately for situations in which (1) the attacker and respondent are copartisans; (2) the target and respondent are copartisans; (3) the respondent does not support any party; (4) the respondent supports a party other than the Conservative or Labour parties.

After being allocated to a treatment and viewing the corresponding images, the respondent was asked to indicate on a scale from 0 (very unfavourable) to 10 (very favourable) how they feel about each candidate, with the incumbent candidate in the treatment being presented first. They were also asked to rate the negativity of each candidate’s leaflet on a scale from 0 (very negative) to 10 (very positive). The exact question wording is available in the online Supplementary Appendix (S1). To explore how the effects are moderated by partisanship, we asked respondents to indicate which party they most closely identified with.Footnote 17 Following the work of Somer-Topcu and Weitzel (Reference Somer-Topcu and Weitzel2022), our partisanship variable contains four categories: attacker copartisan (N = 418), target copartisan (N = 383), out-party (N = 262), and non-partisan (N = 351).

Our choice to present the incumbent frame as neutral while including positive attributes in the challenger control frame may have some drawbacks; most notably, it may create a large discrepancy between the control group values for our measures of attacker and target favourability. However, we find no such issue in the distribution of these variables in our control group.Footnote 18

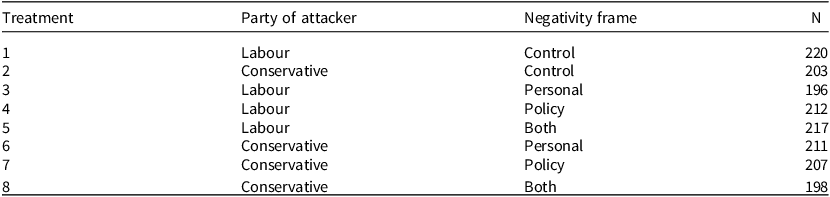

The survey experiment was conducted by YouGov on 28 June 2022, with 1,664 respondents allocated across each of the 8 treatments. Footnote 19 The median time taken for a respondent to complete the survey was 12.5 minutes (lower quartile = 9.36 minutes, upper quartile = 16.77 minutes)Footnote 20 . Table 1 shows the number of respondents assigned to each treatment group (see the Supplementary Appendix (S1) for full details on the stimuli used for each treatment group).

Table 1. Allocation of respondents by treatment group

Results

Overall results

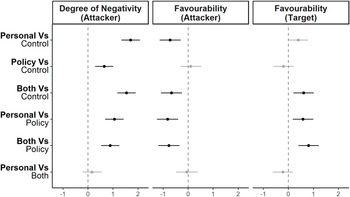

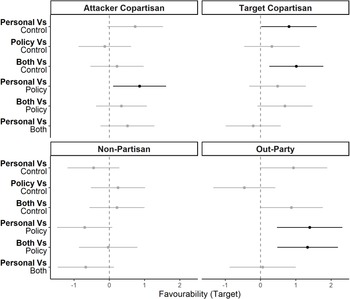

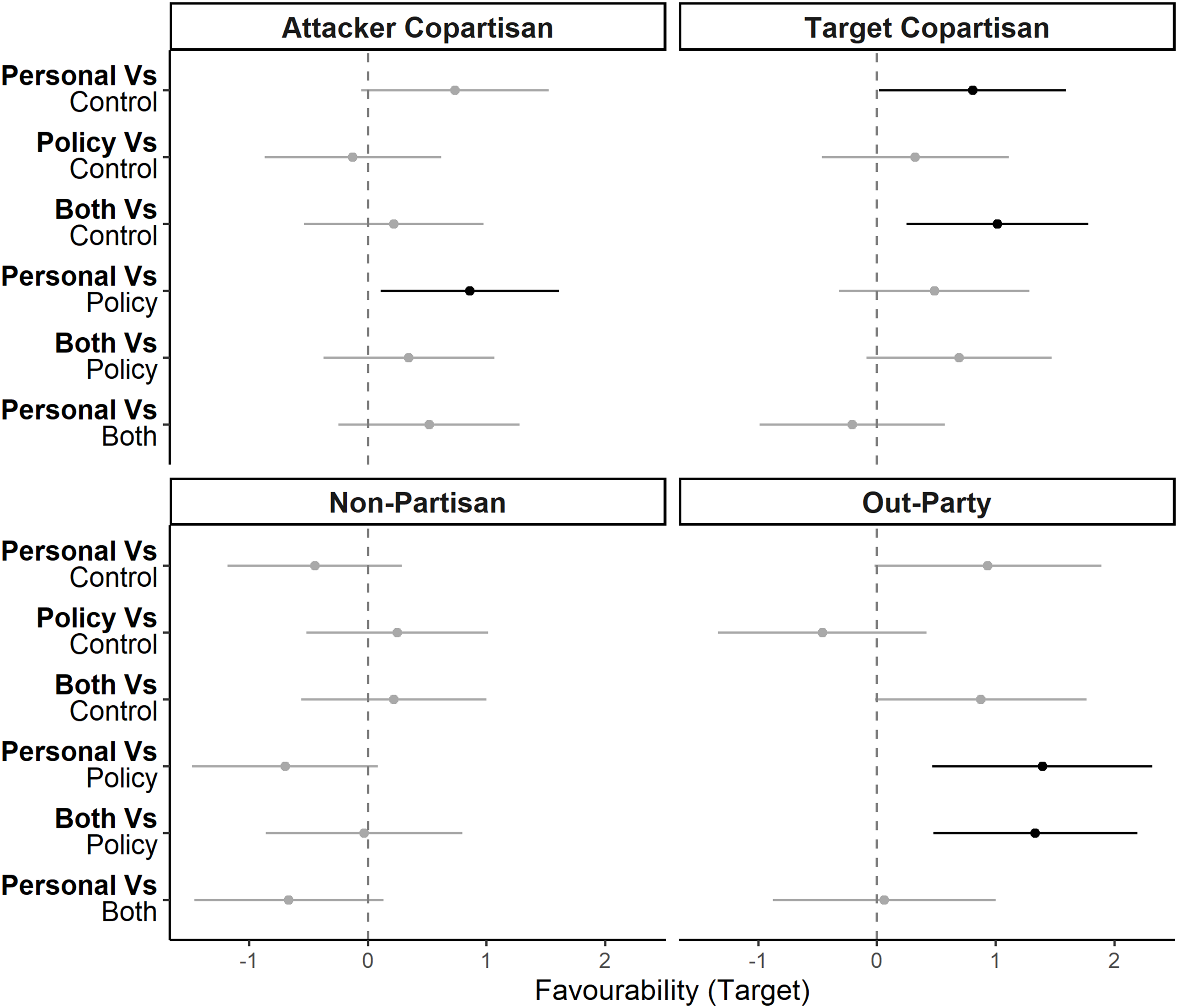

To test our hypotheses, we run regression models to estimate treatment effects for three dependent variables: (1) the perceived negativity of the attacking candidate, (2) the favourability of the attacking candidate, and (3) the favourability of the targeted candidate. In these models, we compare all possible pairwise combinations of our treatments; that is, we compare each negativity frame against the control as well as all three negativity frames (personal attacks, policy attacks, or both personal and policy attacks) with each other. In Figure 2, we do this for all respondents by pooling attacks from both the Labour and Conservative parties and ignoring the partisanship of the respondent.

Figure 2. Pairwise treatment effects.

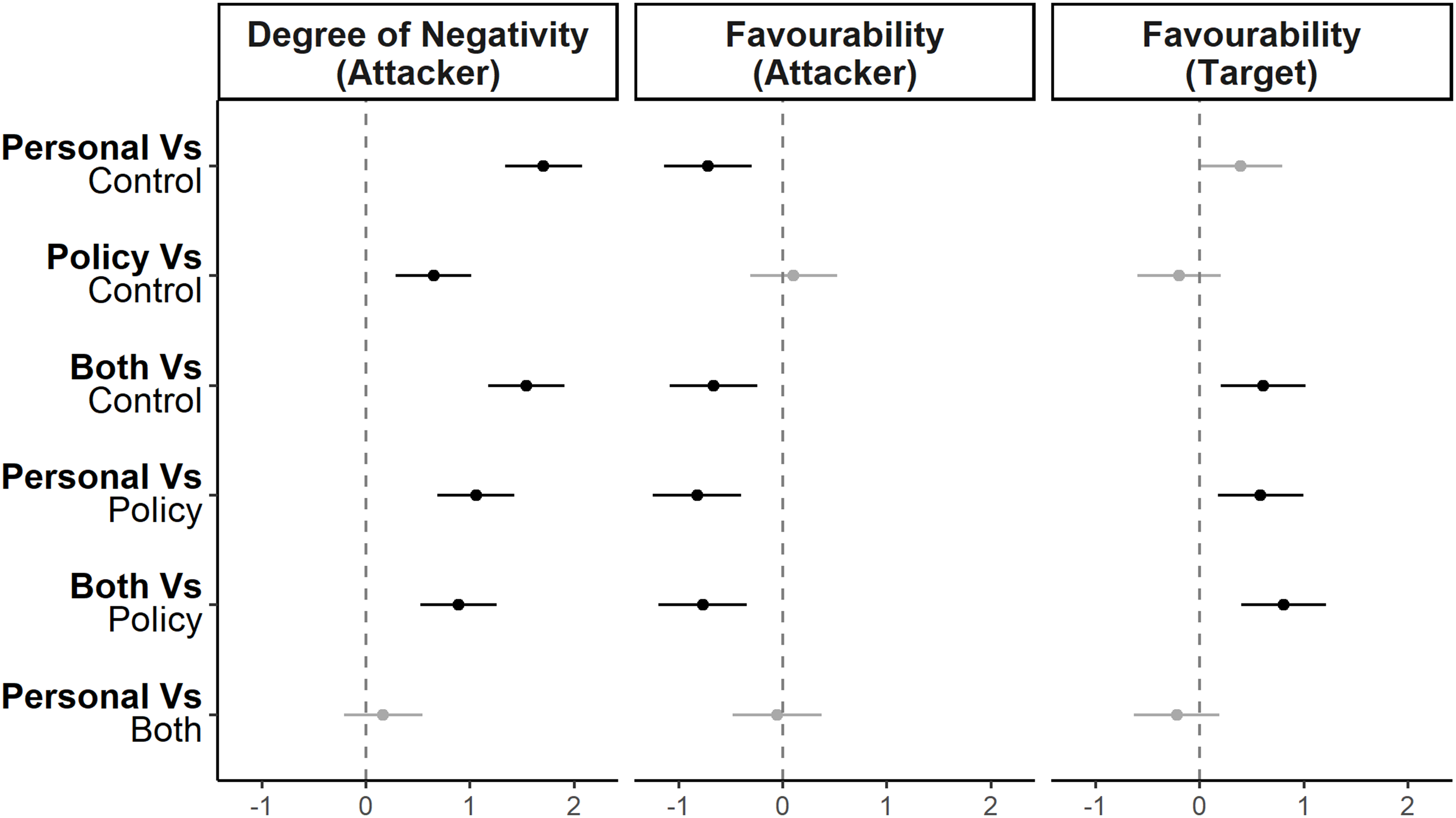

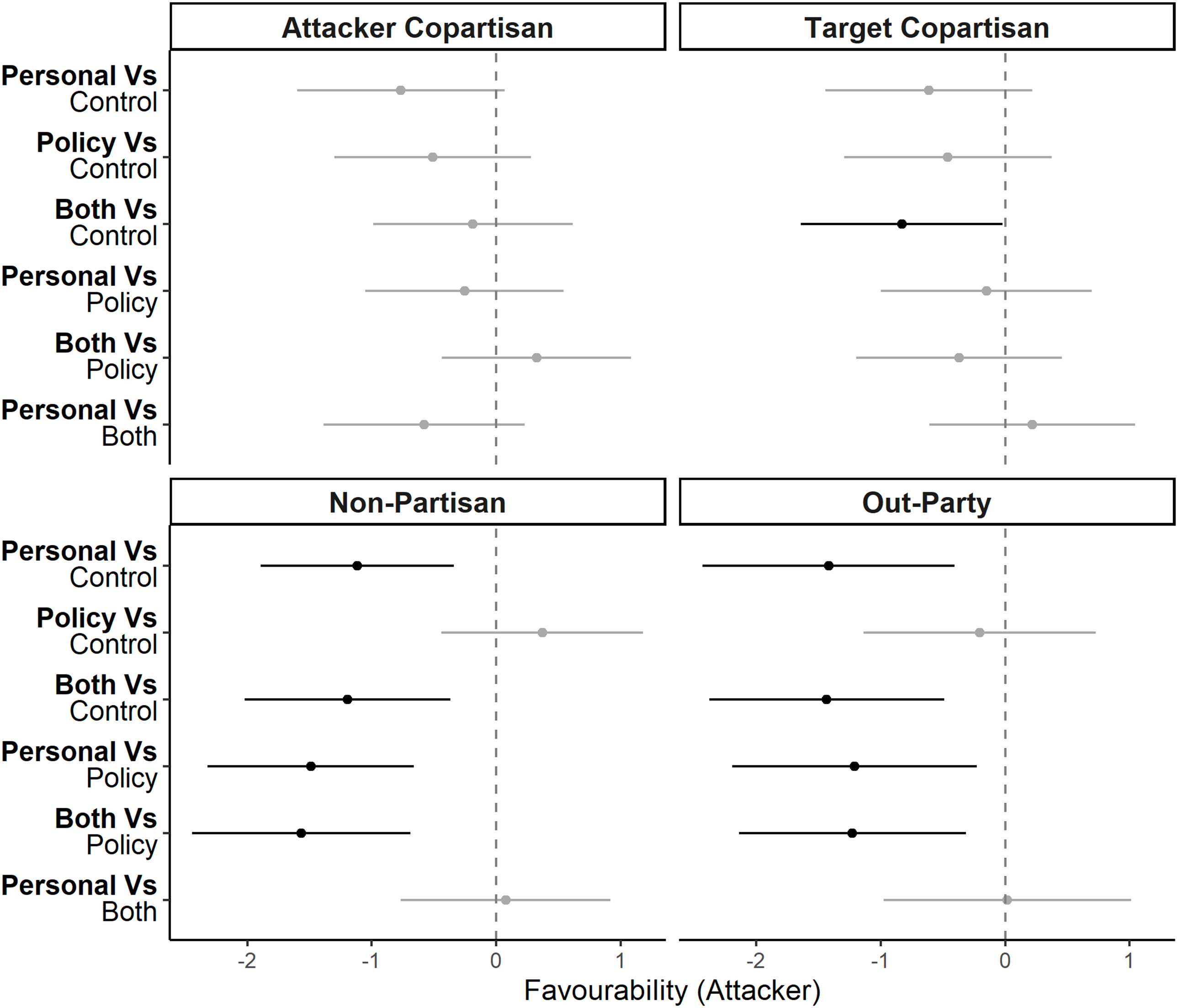

Our findings are shown in Figures 2–5; we present only graphical results in the main text to improve clarity, provide for better visualisation of uncertainty, and increase accessibility for readers that may be less familiar with quantitative methods (King, Tomz, and Wittenberg Reference King, Tomz and Wittenberg2000; Kastellec and Leoni Reference Kastellec and Leoni2007)Footnote 21 . Results in Figure 2 are split into three panes, one for each of our three dependent variables (the relevant dependent variables are listed above the estimates). Each pane in Figure 2 shows the pairwise treatment effects for each of the three negativity types in contrast to the control group (i.e., the treatment with only positive statements about the sponsor), as well as the contrast estimates for each of the treatment groups versus each other.Footnote 22 Each point in the plot is the difference between the mean of the dependent variable for the treatment in bold and the mean of the dependent variable for the treatment listed after the word ‘vs’. Results are statistically significant at the 0.05 level if the estimate is displayed in black; otherwise, estimates are presented in grey. Statistically significant results to the left of the dashed line indicate a decrease (e.g., a decrease in favourability), and to the right of the line indicate an increase (e.g., an increase in perceived negativity).

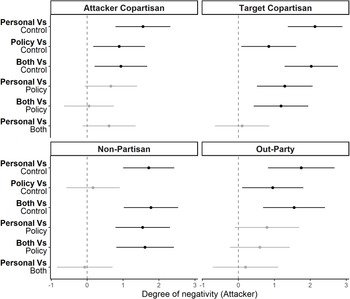

Figure 3. Pairwise treatment effects by partisanship (degree of negativity – attacker).

Figure 4. Pairwise treatment effects by partisanship (favourability – attacker).

Figure 5. Pairwise treatment effects by partisanship (favourability – target).

Each dependent variable is bounded between 0 and 10, with the x-axis indicating the size of the increase/decrease. The y-axis lists each pairwise contrast aligned with the corresponding estimate in the graph panes. For example, the first contrast effect in the left-hand pane (Personal vs. Control) indicates that the perceived negativity of respondents in the treatment group, including the personal attack, was 1.7 points higher than respondents in the control group (i.e., the group that received no negative messages). Finally, each of our analyses was run using sample weights provided by YouGov.Footnote 23

Results in the left-hand pane of Figure 2 suggest that respondents perceive all three treatments as more negative than the control. Put differently, respondents recognise criticism as negativity, even if it is related to policy. That said, the treatments, including personal attacks, are more negative than the attacks on policy. We can see this clearly in the bottom three estimates. The two treatment conditions that contain a personal attack element are perceived more negatively than the treatment containing only a policy element (i.e., ‘Personal Vs Policy’ and ‘Both Vs Policy’). When we combine this with the statistically insignificant result when we compare the two treatments containing a personal attack to each other (i.e., ‘Personal Vs Both’), this provides strong evidence that the presence of the personal attack elements is perceived more negatively. The middle pane suggests that the favourability of the attacking candidate is lower in treatments that include the personal attacks. The right-hand panel suggests that the favourability of the targeted candidate does not decrease in any of the treatments and may increase when they are attacked on personal grounds.

There is a striking consistency to the results in Figure 2 that suggests three conclusions about personal attacks. First, H1 is confirmed, as respondents perceive attacks that include personal content to be more negative. On the other hand, our expectations in H2 are not met because the favourability of the target candidate is actually higher in treatments that include personal attacks. Finally, we find support for H3, which stated the favourability of the attacking candidate would be lower in treatments that include personal attacks.

We can also conclude from the results in the figure that the attitudes of respondents are not moved by policy-based attacks. In other words, they perceive such attacks as fair game. However, these attacks are not sufficient to affect their perception of either the attacker or the target. For policy-based attacks then, this suggests a net null effect for attackers. However, when looking at treatments that include personal attacks, our findings suggest that respondents do not perceive these tactics as fair, and accordingly, their opinion of the attacker declines while their favourability of the target increases. This amounts to a double backlash, or boomerang effect, for the attacker.

Results by partisanship

Our fourth hypothesis (H4) suggests that partisan motivated reasoning should condition the effects in Figure 2 (Bolsen, Druckman, and Cook Reference Bolsen, Druckman and Cook2014; Leeper and Slothuus Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014; Somer-Topcu and Weitzel Reference Somer-Topcu and Weitzel2022). As such, we re-estimate the treatment effects by partisanship in Figures 3, 4, and 5. Each figure displays the results for a different dependent variable. The four panels in each figure display the results depending on the respondent’s partisanship. The top left panel displays the situation in which the attacker in the treatment and the respondent are in the same party. The top right panel displays the situation in which the respondent and the target of the attack are in the same party. The bottom panels display results for respondents who are not aligned with the party of the target or the party of the attacker. In the bottom left panel are non-partisan respondents while out-party respondents, i.e., respondents who support another party, are on the right.

The dependent variable in Figure 3 is the extent to which respondents agree that the attacker’s leaflet was negative. The results suggest that the increased perception of negativity among respondents is present across all partisan groups. As we would expect, the results are more muted for attacker copartisans and more pronounced for target copartisans. Most interestingly, the results for non-partisans in Figure 3 are more pronounced than either out-party or attacker copartisan respondents. Additionally, statistically significant effects of negativity are only observed among non-partisan respondents when the treatment included personal attacks. Figure 3 suggests that the increased perception of negativity seen in Figure 2 (for treatments that include personal attacks in particular) is largely driven by target copartisans and non-partisans.

Results for candidate favourability in Figures 4 and 5 suggest that both target and attacker copartisans are largely unaffected by the treatments (H4). This aligns with expectations, as these attitudes are baked in for the most part (e.g., Labour partisans are unlikely to change their rating of favourability for either their own candidate or the Conservative candidate based on these treatments). Figure 4 shows that the damage to the favourability of the attacking candidate is driven almost exclusively by the opinions of non-partisan and out-party respondents. Put differently, out-party and non-partisan respondents are more likely to punish a candidate engaging in a personal attack (H4). This serves to magnify the backlash, or boomerang effect, for the attacker as their favourability falls among those voters that may be most targetable (i.e., non-partisans) or those that may be deciding the best tactical way to use their vote (i.e., out-party respondents) given the majoritarian nature of the electoral system. Figure 4 also reinforces the finding that there is a clear difference in how respondents both perceive and respond to personal attacks in comparison to policy attacks. Finally, Figure 5 suggests that the negative messages have no impact on the favourability of the target for non-partisans and may even produce higher favourability for the target among out-party respondents in some cases. This behaviour could be driven by a dislike for negativity in general or respondents sympathising with the target of attacks.

In summary, our analysis offers the following findings: (1) significant evidence that personal attacks are perceived as more negative by voters, (2) voter perception of how negative an attack is important in whether or not their political attitudes are affected, (3) policy-based attacks do not seem to derive any benefit for the attacker, and (4) there are significant backlash effects for engaging in personal attacks, with attacker favourability declining among non-partisans and out-party respondents, and no evidence that target favourability is negatively impacted.

Post-hoc mechanism check

In designing the experiment, we assumed that respondents would interpret the leaflet statements in particular ways. For example, we assumed that stating someone went to Oxford is negative because that is how the statement is used in the leaflets we were mimicking. In April 2025, we ran a post-hoc mechanism check on the Prolific Platform to test if UK residents agreed with our assumptions. (N = 300). In the experiment, we took some of the statements from the leaflets in our main study and asked participants to imagine a prospective parliamentary candidate made the statement. This helps us understand exactly what the respondents are reacting to in our main experiment.

Each participant was asked about three types of statements, and within each statement there was a 2X2 experiment. One statement was about schooling (Oxford or an apprentice), another was about previous experience (politician or business owner), and the final statement was about policy (investing in housing or saving an historic building). Participants were randomly assigned to either consider that the candidate was making the statement about themselves or they were making the statement about their opponent.Footnote 24 Participants were then asked to rate how negatively they viewed the sponsor (i.e., the candidate making the statement), the opponent, how civil the campaign was, and how relevant the information was to their vote decision.

The results can be found in the Supplementary Appendix (S.6) but can be summarised fairly easily. Respondents were more likely to view a candidate negatively if they went to Oxford or were a career politician, suggesting that the contrast treatments should have lowered evaluations of the targeted candidate in the main experiment. However, we can also see a backlash effect. As many or more participants rated the sponsoring candidate as negatively when they spoke about the opponent regardless of what they said as they did when the sponsoring candidate claimed to hold a disliked background. They were also more likely to say the candidate was engaging in uncivil campaigning and that the biographical information was irrelevant.

In sum, the post-hoc experiment demonstrates why contrasting personal biographies failed to increase support for the sponsoring candidate. The respondents preferred the sponsor’s background to the target’s background. Enough believed, however, that discussing the background at all was uncivil and irrelevant to negate any positive effect of the positive personalisation and create a backlash due to the negativity.

Conclusion and implications

Negative campaigning is one of the most studied areas of electoral politics. Nevertheless, by conducting an experiment outside of the United States and using the most common form of campaign communication in British general elections, the leaflet, we make a unique contribution to the literature. While there have been studies about when British parties and their candidates engage in negativity (e.g., Duggan and Milazzo Reference Duggan and Milazzo2023; Trumm, Milazzo, and Duggan Reference Trumm, Milazzo and Duggan2023; vanHeerde-Hudson Reference vanHeerde-Hudson2011; Walter and van der Eijk Reference Walter and van der Eijk2019), there has been little examination of the consequences of doing so. We can find no meaningful analysis on the impact of negativity on voter attitudes in Britain since Sanders and Norris (Reference Sanders and Norris2005). Further, unlike the existing U.S.-focused negative campaigns literature, we included both positive (about the sponsor) and negative (about the candidate) messages, which better reflects how modern candidates are using personalisation to sway voters than negative messages alone (McGregor, Lawrence, Cardona Reference McGregor, Lawrence and Cardona2017; McGregor Reference McGregor2018).

Using a novel survey experiment designed to replicate real election leaflet messaging, we explore how voters perceive the negativity of different types of attacks and how these messages impact assessments of both the author and the target of the message. The literature has shown mixed results for the effectiveness of negative campaigning. The results in this paper largely fall on the side that negative campaigning is ineffective and/or risky. For policy-based messages, we see neither a benefit nor a backlash to the attacker. On the other hand, our findings support the view that attacks focusing on personal characteristics are a risky strategy: they lower evaluations of the attacker while failing to harm the target. The post-hoc experiment confirms that the personalisation in the campaign leaflet fails to create a positive, parasocial relationship that shields the attacker from suffering backlash among out-partisans and, more crucially, the non-partisan voters. Such voters are particularly critical in two-party battlegrounds. As partisans tend to be less open to persuasion, out-party and non-partisan voters are exactly the individuals that a challenging candidate needs to attract to unseat their opponent.

Our analysis suggests a compounded backlash effect for attackers in that they damage themselves amongst arguably the most persuadable group in the electorate while also failing to impact the favourability of their target. This backlash among voters who do not back either major party is important, as the percentage of those voters is much greater outside the U.S. Beyond the American context, only Somer-Topcu and Weitzel (Reference Somer-Topcu and Weitzel2022) incorporate partisanship into analyses on negativity, but they estimate only the effect on the target. Our findings suggest a clear alignment between the type of messages that respondents perceive as being more negative and the types of messages in which the attacker suffers a backlash. This supports work from other contexts suggesting that voters may dislike negativity in general (Ansolabehere et al. Reference Ansolabehere, Iyengar and Simon1994) and personal attacks in particular (Fridkin and Kenney Reference Fridkin and Kenney2011). The main experiments and post-hoc study also offer new evidence on what constitutes negativity (particularly in personal attacks) in the British context and highlight how this may differ significantly when compared to the well-studied US case. The comparatively tame attacks that are perceived as negative by British voters may not be considered as such by US voters or voters from other contexts.

There are, of course, limitations to these findings. While we based our treatments on actual campaign leaflets from British general elections, there are many forms that negativity can take. It is possible that personal attacks could work – just not the ones presented here. Also, these treatments were presented in a vacuum. It is possible that a candidate could form a parasocial relationship with voters via personal appearances or social media, and the goodwill generated would cause voters to give them leeway in their leaflet’s messages (Piston et al. Reference Piston, Krupnikov and Milita2018). While these limitations suggest we might be overestimating the drawbacks of negativity, it is also possible that the one-shot nature of the experiment results is underestimating it. Voters may forgive a single leaflet with some negativity more than they would forgive a campaign with nothing but repeated negative messages (Banda and Windett Reference Banda and Windett2016). The use of fictional candidates in our treatments may also underestimate the magnitude of effects, as voter reaction to attacks on their real incumbent MP may be stronger.

There are five avenues of further research that we believe would be eminently feasible and beneficial to pursue: first, incorporation of the ‘civility’ dimension outlined by Brooks and Geer (Reference Brooks and Geer2007) would offer greater understanding of how British voters respond to negative messaging. For example, varying the civility of both policy- and personal-based attacks would offer insight into whether ‘uncivil’ policy attacks are perceived more negatively or have different impacts than the type employed in our vignettes. Additionally, such an analysis would allow for testing of the reasonable extrapolation, based on our results, that ‘uncivil’ personal attacks may have a larger backlash effect against the sponsor. Such an analysis would also necessitate a conceptualisation of what constitutes incivility in the British context in a similar way to the design of personal attacks in this paper. Second, there is significant scope to offer comparative analysis of different mediums of negative messaging in British politics. Traditionally, and due to significant restrictions on political advertising via TV and radio, unsolicited materials (i.e., leaflets) have been the key communication tool of British political actors. However, the expansion of the online space in recent years has offered political candidates and parties an unprecedented opportunity to produce and disseminate campaign videos. The work of Rossini et al. (Reference Rossini, Southern and Harmer2024) suggests that there may be many fruitful comparisons to be made between negative messaging in these traditional and emerging mediums of British politics. Third, in line with recent work (Nai and Maier Reference Nai and Maier2021; Nai and Otto Reference Nai and Otto2021), there is considerable potential in uncovering the heterogeneous effects of negative messaging based on the personal characteristics and personality traits of respondents. Such analyses would be of undoubted interest to both political scientists and political strategists. Fourth, Herrnson, Lay, and Stokes (Reference Herrnson, Celeste Lay and Stokes2003) suggest that female candidates may be more likely to experience backlash effects from negativity, while Fridkin, Kenney, and Woodall (Reference Fridkin, Kenney and Woodall2009) suggest that female candidates may better withstand attacks from male rivals. It is possible that varying the gender of the attacker, the target, or both may impact on the findings we present here, and this would offer greater insight into the effects of negativity in British campaigns. Finally, there is a relatively small but growing literature investigating the effects of negative messaging outside the US. However, this work largely focuses on outcomes such as perceived negativity, vote choice, or candidate favourability. There is significant scope to integrate measures such as political cynicism, political efficacy, and trust in government into studies of British politics. This would provide useful insight into the system-wide effects that negative messaging may be having on British democracy and politics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676525100418.

Data availability statement

The replication materials, including scripts and additional datasets used in our analysis, are publicly accessible via https://doi.org/10.17639/nott.7607.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Department of Political Science at Trinity College Dublin for the helpful comments received during their Friday Seminar series.

Competing interests

None.

Appendix A. Descriptive statistics for survey respondents

Note: 5.35% of respondents responded ‘Don’t know’ when asked about education level. There was also one missing value for this variable.

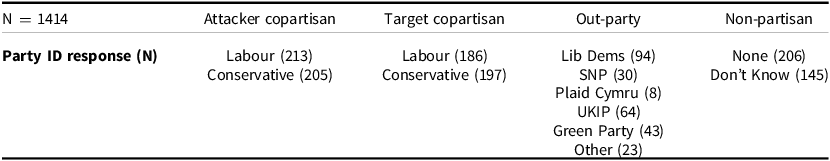

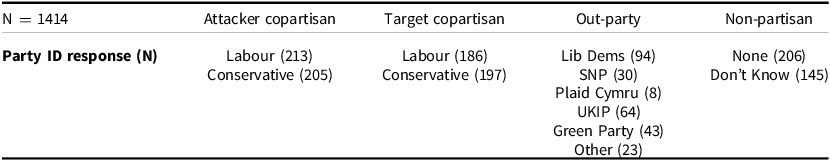

Appendix B. Partisanship and Party ID

The party ID question used to create our partisanship variable was worded as follows: ‘Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as Labour, Conservative, Liberal Democrat or what?’. Given that our treatment vignettes centre around Labour and Conservative candidates, respondents that identified with these two parties were allocated to either the attacker or target copartisan category. For example, if a respondent identified with Labour and was exposed to a treatment in which the Labour candidate was being attacked, they would be categorised as a target copartisan. Respondents that identified with any other named party were allocated to the out-party category. Finally, respondents that answered the Party ID question with either ‘None’ or ‘Don’t Know’ were allocated to the non-partisan category. Table D.1 provides the distribution of values for the Party ID variable and how they were allocated to the partisanship variable used in our analysis.

Table B1. Party ID values allocated to partisanship

Note: There were 250 missing values for the party ID question. As such, these observations were dropped from analyses including the partisanship variable.