1. Introduction

Multiparty government frequently involves delegation to ministers, giving rise to information asymmetries that can be threatening to individual parties. There is now a solid understanding of how parties navigate these problems in the domestic arena (e.g. Thies, Reference Thies2001; Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2004; Reference Martin and Vanberg2011; Lipsmeyer and Pierce, Reference Lipsmeyer and Pierce2011; Carroll and Cox, Reference Carroll and Cox2012; Klüver et al., Reference Klüver, Bäck and Krauss2023; Klüser, Reference Klüser2024). However, similar problems arise when coalition governments delegate ministers to negotiate at the international level, such as in the Council of the EU (hereafter Council). Because ministers belong to only one of the coalition parties, delegation creates information asymmetries between insiders, who hold negotiation responsibility, and outsiders, who are sidelined. Outsiders thus face the risk of ministerial drift where insiders exploit their information advantage and advance their own party’s preferences rather than the coalition compromise. While recent scholarship has begun to examine these dynamics (Finke and Herbel, Reference Finke and Herbel2015; Franchino and Wratil, Reference Franchino and Wratil2019; Kostadinova and Kreppel, Reference Kostadinova and Kreppel2022), we still know little about the mechanisms coalitions use to resolve delegation problems in these settings.

This paper argues that committees in the European Parliament (EP) provide sidelined coalition parties with opportunities to shadow their coalition partners, functioning similarly to committee oversight in national parliaments (cf. Hallerberg, Reference Hallerberg2000; Kim and Loewenberg, Reference Kim and Loewenberg2005; Carroll and Cox, Reference Carroll and Cox2012; Krauss et al., Reference Krauss, Praprotnik and Thürk2021). In the strong bicameral system of the EU, committees in the EP frequently interact with the Council and are vastly important for providing their members with detailed insights into the legislative process (Ringe, Reference Ringe2009). Moreover, committee membership is a prerequisite for becoming a rapporteur, which allows members of the EP (MEPs) to intervene even more directly in policymaking. By serving on committees that correspond to Council meetings where their national party lacks ministerial representation, MEPs thus gain insight into legislative developments and oversight over their coalition partners. In doing so, sidelined parties can reduce information asymmetries within the coalition, thereby mitigating the risk of ministerial drift.

Yet, very few national parties have enough MEPs to sit on all committees, forcing them to make strategic trade-offs. Because of this scarcity, committee choice is an informative outcome reflecting parties’ priorities. I argue that coalition parties navigate these trade-offs by considering both their status as insiders or outsiders and their misalignment with coalition partners relative to other actors in the Council, as these factors shape the risk posed by information asymmetries and ministerial drift. Among committees where a coalition party is sidelined, parties should prioritize those where their policy positions differ most strongly from their coalition partners, relative to other governments in the Council. Similarly, sidelined and misaligned MEPs should pursue rapporteur assignments on bills that are particularly controversial among coalition partners. Analyzing committee appointments in the 6–9th term of the EP (2004–2024) and rapporteur assignments in the 6–8th term (2004–2019), I find strong support for the empirical implications of the theoretical argument.

These findings have important implications for our understanding of international policymaking and coalition governance. Delegation problems for coalition governments in the international arena extend far beyond the EU. Ministerial-level meetings in forums such as the G7, NATO, the OECD, the WTO, and the Council of Europe similarly rely on delegation to individual ministers. For instance, the G7 countries held 23 meetings at the ministerial level in 2024.Footnote 1 Understanding how sidelined coalition parties can navigate these problems within different institutional contexts is thus paramount. In the Council of the EU, this paper highlights the role of parliamentary oversight and strong bicameralism as mechanisms of control. While such institutional features are not universally present across international organizations—even if parliaments are becoming more common (Rocabert et al., Reference Rocabert, Schimmelfennig, Crasnic and Winzen2019)—the findings underscore a broader point that mechanisms for monitoring ministers matter in international settings, not just in domestic arenas.

The findings of this study also square nicely with studies of domestic coalition policymaking that emphasize the role of parliamentary oversight and committees in resolving coalition conflict (Kim and Loewenberg, Reference Kim and Loewenberg2005; Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011; Carroll and Cox, Reference Carroll and Cox2012; Krauss et al., Reference Krauss, Praprotnik and Thürk2021). Beyond domestic politics, the EP plays a similarly crucial role in resolving the delegation problems that afflict coalition governments. The increasing strength of the EP in European bicameralism (for an overview, see Hix and Høyland, Reference Hix and Høyland2013) has enabled sidelined coalition partners to obtain a degree of oversight that would not otherwise be possible. This underscores the significance of the EP’s institutional evolution for the functioning of European and EU governance. As EU policymaking takes on an increasingly prominent role in domestic politics (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009), mechanisms to resolve conflicts among coalition parties become crucial for producing policies that reflect the preferences of the citizens who voted these parties into office.

2. Domestic and international coalition policymaking

Coalition governments face many of the same problems in the EU that they also encounter in the domestic sphere. Ideological differences within multiparty governments create incentives for coalition parties to pursue partisan goals while they have to overcome their differences to engage in policymaking with joint accountability (cf. Huber, Reference Huber1996; Laver and Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996; Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011). Domestically, coalitions rely heavily on delegation of policymaking tasks to individual ministers (Laver and Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996). This generates opportunities for coalition parties to gain information advantages over their coalition partners and creates the risk of ministerial drift (Laver and Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996; Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005, Reference Martin and Vanberg2014; Klüver and Bäck, Reference Klüver and Bäck2019).

In EU policymaking, similar issues arise because member states delegate negotiation tasks to individual ministers. Recent scholarship has started to explore this delegation by applying theories of coalition policymaking to the EU (seeDörrenbächer et al., Reference Dörrenbächer, Mastenbroek and Toshkov2015; Finke and Herbel, Reference Finke and Herbel2015, Reference Finke and Herbel2018; Franchino and Wratil, Reference Franchino and Wratil2019; Kostadinova and Kreppel, Reference Kostadinova and Kreppel2022). Here, the need for delegation results from the institutional setup of the Council of the EU which meets in different sectoral configurations.Footnote 2 For meetings in a specific configuration, governments send the minister responsible for the relevant portfolio. Conversely, this implies that coalition parties that do not control the relevant portfolio are excluded from direct involvement in these talks, making them outsiders in these Council configurations. Importantly, the same coalition party will be an insider in other configurations. Insider and outsider status thus always depend on the Council configuration.

International negotiations in the Council enable insiders to obtain information advantages because their ministers are directly involved in the policymaking process and the negotiations with other member states. To name but a few benefits, these ministers can obtain information about the legislative state of play, context on proposed legislation, positions and issues of other negotiators, and they have access to informal discussions on the fringes of the negotiations—merely by virtue of being insiders. This information asymmetry matters because ministers’ privileged access also provides them with opportunities for engaging in ministerial drift. This may take the extreme form of voting against the will of the coalition partner or more subtle forms such as pursuing amendments, persuading other negotiators, or omitting the position of their coalition partner.Footnote 3

To prevent such behavior, sidelined coalition partners have to find ways to reduce information asymmetries. While coalition partners in domestic settings can use information directly to amend bills, such levers are largely absent in the EU context. However, information still plays a crucial role. In particular, outsiders require information to anticipate potential drift, which enables them to raise awareness of policy disagreements within the coalition—both among other negotiators in the Council and co-partisans at the domestic level. Information is also instrumental in holding insiders accountable ex post and increase reputational and political costs for non-compliance with the coalition compromise. Monitoring thus functions as an indirect constraint: by reducing uncertainty about what happens in EU policymaking and in the Council, outsiders are better equipped to credibly threaten punishment for ministerial drift. Moreover, monitoring can also induce self-restraint: ministers may refrain from ministerial drift because they are aware they are being shadowed and thus anticipate that deviation will be detected.

When outsiders lack the necessary information to detect deviations from the compromise, insiders can credibly claim to both their coalition partners and other negotiators that they are honoring the coalition compromise even when they are not. This is especially true in the case of the EU with its highly complex and oftentimes technical nature of policy. While some information may be accessible to sidelined coalition partners, it is often difficult to obtain, and other aspects remain entirely out of reach for those not directly involved in the negotiations. Many Council discussions are held behind closed doors, precluding external scrutiny and making outsiders heavily dependent on the information relayed by the insider back home—even where reporting obligations or domestic scrutiny procedures exist.Footnote 4

In domestic policymaking, coalitions resolve these issues in a number of ways. A vast literature has identified several institutional mechanisms for reducing information asymmetries and reining in ministerial drift. In addition to executive mechanisms (e.g. Thies, Reference Thies2001; Lipsmeyer and Pierce, Reference Lipsmeyer and Pierce2011; Moury, Reference Moury2011; Klüser and Breunig, Reference Klüser and Breunig2023; Klüver et al., Reference Klüver, Bäck and Krauss2023; Klüser, Reference Klüser2024), parliamentary oversight plays a crucial role for coalition parties (e.g. Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2004, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011, Reference Martin and Vanberg2020, Kim and Loewenberg, Reference Kim and Loewenberg2005; Carroll and Cox, Reference Carroll and Cox2012). In the aggregate, these institutions are effective in resolving the central tension of coalition governance as several studies suggest that actual coalition policy output is much more reflective of compromise than ministerial drift (Goodhart, Reference Goodhart2013; Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2014).

At the European level, too, such institutions have been found to be effective in mitigating the delegation problems discussed above. While some highlight executive institutions (Franchino and Wratil, Reference Franchino and Wratil2019; Kostadinova and Kreppel, Reference Kostadinova and Kreppel2022), others point to the role of parliamentary scrutiny (Finke and Dannwolf, Reference Finke and Dannwolf2013; Finke and Herbel, Reference Finke and Herbel2015, Reference Finke and Herbel2018). Yet, these studies focus exclusively on national oversight provided by national parliaments and overlook the importance of the EP in the strong bicameral system of the EU. This is problematic because national-level institutions may be insufficient for coalition oversight; not only because coalition partners often rely on information relayed by the responsible minister, but also because such mechanisms are not uniformly available across EU member states (Kassim, Reference Kassim2013; Winzen, Reference Winzen2022). Below, I argue that EP committees play a crucial role for monitoring coalition partners in the EU.

3. (European) parliamentary oversight

Through their direct involvement in legislative processes, committees provide their members with information and enable monitoring of ministerial behavior (cf. Döring, Reference Döring1995; Strøm et al., Reference Strøm, Müller and Smith2010). In the EP, committee oversight is particularly crucial due to the volume, technical nature, and complexity of EU policymaking that all but prevents MEPs from having any detailed information on many of the legislative files and numerous amendments on which they vote (Ringe, Reference Ringe2009). Consistent with the EP’s characterization as a working parliament, committees become pivotal in providing MEPs with the necessary policy expertise and information (Ringe, Reference Ringe2009).

For coalition parties, this makes some committees more attractive than others. Committees in the EP are sectorally organized in a way that closely resembles the division of policymaking across the different Council configurations. By serving on a corresponding EP committee, sidelined coalition parties thus gain access to crucial background information on legislative proposals and ongoing developments in a given policy area. This contextual knowledge does not necessarily grant direct or real-time insights into the Council’s often opaque proceedings, but it equips sidelined parties with the expertise to interpret and constrain their partner’s behavior in EU policymaking—both ex ante and ex post. For example, they may seek out allies among other countries’ negotiators in the Council or they may provide domestic co-partisans with the necessary information to leverage domestic oversight institutions more accurately.Footnote 5 Regardless of the specific form, constraint requires policy expertise as even perfect observability is useless if outsiders lack the expertise to understand what is at stake or to formulate preferable and credible policy alternatives (cf.Martin and Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011).

Committee membership also enables MEPs to be appointed as rapporteurs for specific legislative proposals. As one of the most influential roles in the EP, rapporteurship provides direct access to inter-institutional negotiations and more detailed information on legislative files (Kreppel, Reference Kreppel2002; Mamadouh and Raunio, Reference Mamadouh and Raunio2003; Yoshinaka et al., Reference Yoshinaka, McElroy and Bowler2010). This makes rapporteurships particularly attractive for outsiders, as they provide both deeper informational access and more immediate influence on policy outcomes.

Naturally, coalition parties can only gain this access if their MEPs are willing and able to take national party considerations into account when pursuing appointments in the EP. Regarding their willingness, it is important to note that MEPs rely crucially on their national party for reelection and their career (Hix, Reference Hix2002; Faas, Reference Faas2003; Frech, Reference Frech2016). In addition to congruent goals, this incentivizes MEPs to work in the interest of their national party.Footnote 6 On the ability to affect committee appointments, EU scholars have produced an enormous body of work on the drivers of committee appointments in the EP (for overviews, seeHix and Høyland, Reference Hix and Høyland2013; Martin and Mickler, Reference Martin and Mickler2019). Formally, committee members are appointed by party groups (rule 216 of the EP’s rules of procedure), and rapporteurs are assigned by the committee (rule 51), where in practice the posts are auctioned among party groups (Häge and Ringe, Reference Häge and Ringe2020). Indeed, several studies highlight the role of party groups (Kreppel, Reference Kreppel2002; McElroy, Reference McElroy2006; Yordanova, Reference Yordanova2009; Yoshinaka et al., Reference Yoshinaka, McElroy and Bowler2010). While these studies show that appointments are largely proportional to party group strength in the parliament at large, there is also ample evidence that MEPs’ national parties and individual interests matter (e.g.Kreppel, Reference Kreppel2002; Mamadouh and Raunio, Reference Mamadouh and Raunio2003; Kaeding, Reference Kaeding2004; Whitaker, Reference Whitaker2005, Reference Whitaker2019; Hoyland, Reference Hoyland2006; McElroy, Reference McElroy2006; Costello and Thomson, Reference Costello and Thomson2010). These studies show that MEPs are indeed successful in pursuing specific committees for personal or national party reasons.Footnote 7

Similar arguments have been made about committee appointments and chair positions in national legislatures (Hallerberg, Reference Hallerberg2000; Kim and Loewenberg, Reference Kim and Loewenberg2005; Carroll and Cox, Reference Carroll and Cox2012). Although the effect on policy outcomes is disputed (Sieberer and Höhmann, Reference Sieberer and Höhmann2017; Fortunato et al., Reference Fortunato, Martin and Vanberg2019; Krauss et al., Reference Krauss, Praprotnik and Thürk2021), ministers are more likely to be shadowed by a committee chair from another coalition party when ideological divisions within the coalition are large (Carroll and Cox, Reference Carroll and Cox2012; Chiru and De Winter, Reference Chiru and De Winter2023).Footnote 8 Regardless of this ongoing debate, appointment patterns at least suggest that coalition parties expect to make up for their disadvantage through committee shadowing.

Yet, applying the logic of shadowing to the EU level is less straightforward due to several idiosyncrasies of the EP and its committee system. One such idiosyncrasy is that most national parties only receive a handful of seats in the EP.Footnote 9 With the median MEP holding only two committee posts, committee membership is a scarce resource. This forces national parties to make trade-offs in seeking appointments to specific committees because they cannot sit on every standing committee. In turn, this makes committee membership a meaningful indicator of their priorities. Research at the national level has put much emphasis on committee chairs because parties can have members on all standing committees. The scarcity at the European level thus provides insights into the value of committee membership in itself.

Another consequential difference is the driver of coalition parties’ motivations at the European level. In addition to their status as insiders or outsiders and ideological divisions within the coalition as the driving force of committee appointments (Carroll and Cox, Reference Carroll and Cox2012), parties also need to take into account the average position of other negotiators in the Council, which provides a focal point. Focusing on the most simple case of a two-partyFootnote 10 government involving parties ![]() $A$ and

$A$ and ![]() $B$, there exist three unique position orderings up to scale reversal when all actors hold distinct positions

$B$, there exist three unique position orderings up to scale reversal when all actors hold distinct positions ![]() $\theta_j$. First, when the ordering is

$\theta_j$. First, when the ordering is ![]() $\theta_A \lt \theta_\text{Council} \lt \theta_B$, both parties would be concerned about ministerial drift if they were outsiders because successful ministerial drift by the partner implies that the resulting policy would move away from the outsiders’ ideal point. In this setting, it is also credible to assume that the outsider could intervene by allying with others in the Council. Consequently, reducing the information asymmetry in this setting is crucial. Second, for

$\theta_A \lt \theta_\text{Council} \lt \theta_B$, both parties would be concerned about ministerial drift if they were outsiders because successful ministerial drift by the partner implies that the resulting policy would move away from the outsiders’ ideal point. In this setting, it is also credible to assume that the outsider could intervene by allying with others in the Council. Consequently, reducing the information asymmetry in this setting is crucial. Second, for ![]() $\theta_A \lt \theta_B \lt \theta_\text{Council}$ or

$\theta_A \lt \theta_B \lt \theta_\text{Council}$ or ![]() $\theta_B \lt \theta_A \lt \theta_\text{Council}$ the risk of ministerial drift is more ambivalent. If the left coalition partner is the outsider, it will actually prefer ministerial drift by the coalition partner as this would move the policy in the preferred direction of the outsider.Footnote 11 In the remaining cases where the right coalition partner is the outsider, the risk of ministerial drift increases as it moves closer to the Council and away from the insider. In summary, the risk of ministerial drift for coalition parties is driven by their position relative to their coalition partner and others in the Council as well as their status as an outsider. The risk of delegation is greatest in policy areas where parties are outsiders and are misaligned with their coalition partners. If coalition dynamics matter for committee appointments in the EP, this should inform parties’ committee choices, which yields the following hypothesis.

$\theta_B \lt \theta_A \lt \theta_\text{Council}$ the risk of ministerial drift is more ambivalent. If the left coalition partner is the outsider, it will actually prefer ministerial drift by the coalition partner as this would move the policy in the preferred direction of the outsider.Footnote 11 In the remaining cases where the right coalition partner is the outsider, the risk of ministerial drift increases as it moves closer to the Council and away from the insider. In summary, the risk of ministerial drift for coalition parties is driven by their position relative to their coalition partner and others in the Council as well as their status as an outsider. The risk of delegation is greatest in policy areas where parties are outsiders and are misaligned with their coalition partners. If coalition dynamics matter for committee appointments in the EP, this should inform parties’ committee choices, which yields the following hypothesis.

H1: Coalition parties pursue committee appointments in policy areas where they are misaligned with their coalition partner(s) relative to others in the Council and where they lack direct representation in the corresponding Council configuration.

For rapporteur assignments, coalition parties need to consider an additional trade-off when pursuing these posts. Because rapporteurships follow a strong principle of proportionality (Kreppel, Reference Kreppel2002; Yoshinaka et al., Reference Yoshinaka, McElroy and Bowler2010), coalition parties are unlikely to be assigned more rapporteurships in the aggregate. Even if an MEP has good reasons for seeking rapporteurships on a specific committee due to coalition dynamics, they are still competing with other members of the committee. If coalition dynamics matter, however, MEPs from coalition parties will make additional trade-offs at the bill level. In particular, MEPs in committees where they are misaligned and sidelined should pursue rapporteurships on bills where they expect high levels of disagreement with their coalition partner. For instance, there may be certain issues within the policy areas that are particularly divisive among coalition partners, while others are less contentious. I thus expect that MEPs who joined a committee for reasons of coalition oversight will pursue rapporteurships on proposals related to the former, which yields the second hypothesis.

H2: Coalition parties pursue rapporteurships in policy areas where they are misaligned with their coalition partner(s) relative to others in the Council and where they lack direct representation in the corresponding Council configuration, particularly on divisive bills.

4. Data & methods

4.1. Dependent variables

I create two original data sets of committee appointments in the 6th through 9th term of the EP (2004–2024) and rapporteur assignments in the 6th through 8th term (2004–2019). For the former, I obtain lists of MEPs sitting on the 20 standing committees of the EP from the parliament’s official website.Footnote 12 I treat chairs, full, and substitute members alike, as all positions can be used to obtain information. To study rapporteur assignment, I collected data on more than 10,000 legislative files that were proposed during the period of observation from the EP’s legislative observatory.Footnote 13 For each legislative file, I consider all rapporteurs that were assigned by any committee.

The final data set of committee appointment contains all theoretically possible combinations of committees and national parties for each legislative term. Dyads are only included if the national party held at least one seat in the EP in the legislative term, but include all parties regardless of whether they are in government or the opposition.Footnote 14, This party-level focus enables the comparison of both insiders and outsiders with parties in the opposition.

For the rapporteur assignments, I proceed similarly, combining each instance where a rapporteur was assigned with the national parties represented in the EP at the time of assignment. However, I only keep dyads where the national party belongs to the same party group as the party of the rapporteur that was actually assigned, which takes into account the actual assignment process (cf. Häge and Ringe, Reference Häge and Ringe2020, for a similar approach). Because these positions are highly valuable, national parties are unlikely to have much power over this first step. Instead, it is more plausible that national party delegations can bargain over the assignment within their own group. By focusing on these plausible within-group alternatives, I thus obtain the relevant counterfactuals while keeping the number of observations reasonable. The same ParlGov party IDs are also used for this data set.

In both data sets, I generate the dependent variables of committee appointment or rapporteur assignment, which are 1 when a national party has a member on the committee or holds a rapporteur post and 0 when they do not. In the final data sets, the average national party is represented in 34% of committees and is chosen as the rapporteur within its party group in 7% of cases. More descriptive statistics on these and all other variables are summarized in Appendix A. For both data sets, I only keep observations during periods when coalition governments were in office.

4.2. Identifying insiders and outsiders

To meaningfully compare parties’ committee and rapporteurship choices, I determine each party’s status as insiders or outsiders in a given policy area or as opposition parties. I first identify opposition parties using information from the ParlGov database (Döring and Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2019).Footnote 15 Distinguishing between insiders and outsiders among the government parties then depends on the party’s responsibility for a given Council configuration. This information is obtained using an empirical approach by combining participant lists of Council meetings with the WhoGov database (Nyrup and Bramwell, Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020). The lists were obtained from the official website of the CouncilFootnote 16 and combined with WhoGov via fuzzy string matching within each country sample. I code parties as insiders if they had at least one minister participating in a meeting of that configuration in a year and as outsiders otherwise.Footnote 17 Using this approach, more than one party from a coalition can be the insider party in a given Council configuration.Footnote 18

In a last step, I transpose this information to the committee level by matching each committee with the Council configuration that best corresponds to the work done in the committee. This, too, is done using an empirical approach. More specifically, I obtain further data on the 10,000 legislative files used to identify rapporteurs mentioned above. For each file, I analyze the lead committees that are most frequently assigned to legislative files that fall under the purview of each Council configuration. For a detailed matching table and further details of this process, refer to Appendix C. In combination, all of these steps yield a categorical variable that identifies each observation as opposition, insider, or outsider.

4.3. Measuring misalignment and disagreement

Next, I turn to the other incentives driving parties to seek appointments. First, I create a general measure of ideological misalignment of parties’ policy positions. This is based on a combination of data on parties and cabinets from ParlGov (Döring and Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2019) and party positions from the Manifesto project (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2019).Footnote 19 Second, I measure bill-specific disagreement from roll-call votes (Hix et al., Reference Hix, Frantescu, Hagemann and Noury2022). While ideological misalignment relates to the general disagreement of the party relative to coalition partners and others in the Council, bill-specific misalignment captures disagreements at a more fine-grained level. This is crucial for picking up on the trade-offs at the bill level necessary for rapporteur assignments.

4.3.1. Relative ideological misalignment

Intuitively, the relative ideological misalignment of a party measures how close the party is to the (other parties in) government compared to how close it is to the average position in the Council. Because the research design models appointments as party choices, this measure must be comparable for all party-committee dyads—whether they are insiders, outsiders, or in the opposition. Throughout, I use parties’ policy positions on a logit scale (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011), which are obtained by matching a number of policy dimensions defined by Laver and Shepsle (Reference Laver and Shepsle1990); Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011), and Volkens et al. (Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2019) with the ten Council configurations as described above. For further details, refer to Appendix D. Because these issue positions vary across policy areas and do not share a common scale, I rescale them within each committee to have unit variance. Government and Council positions are also obtained from these party positions using seat- and vote-weighting as described below.

Relative misalignment is measured as the difference between a party’s ideological distance to the government (excluding itself, if applicable) and its distance to the Council:

\begin{equation}

\Delta_j = \big|\theta_j - \theta_{G\setminus j} \big| - \big|\theta_j - \theta_{\text{Council}\setminus G}\big|

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\Delta_j = \big|\theta_j - \theta_{G\setminus j} \big| - \big|\theta_j - \theta_{\text{Council}\setminus G}\big|

\end{equation} where ![]() $G$ is the set of parties in government,

$G$ is the set of parties in government, ![]() $\theta_{G\setminus j}$ is the seat-weighted average Government position excluding party

$\theta_{G\setminus j}$ is the seat-weighted average Government position excluding party ![]() $j$ itself, and

$j$ itself, and ![]() $\theta_{\text{Council}\setminus G}$ is the voting-power weighted average Council position excluding the position of the government itself.

$\theta_{\text{Council}\setminus G}$ is the voting-power weighted average Council position excluding the position of the government itself.

For any party, the measure captures the potential risk of being excluded from negotiations in a given Council configuration. If the party belongs to the opposition, ![]() $\theta_{G\setminus j}$ is identical to the government position

$\theta_{G\setminus j}$ is identical to the government position ![]() $\theta_G$ such that its relative misalignment is based on a comparison with all coalition parties and the Council. If the party is an outsider, the measure reflects the degree to which its preferences diverge from its coalition partners relative to the Council. If the party is an insider, the measure captures the risk that other coalition parties may seek to monitor or constrain its actions based on how ideologically distant it is from them and the rest of the Council.

$\theta_G$ such that its relative misalignment is based on a comparison with all coalition parties and the Council. If the party is an outsider, the measure reflects the degree to which its preferences diverge from its coalition partners relative to the Council. If the party is an insider, the measure captures the risk that other coalition parties may seek to monitor or constrain its actions based on how ideologically distant it is from them and the rest of the Council.

A conceivable alternative to this is to replace ![]() $\theta_{G\setminus j}$ with the position of the insider in a given Council configuration. While this variant is intuitive from the perspective of outsider parties in coalitions with more than two members,Footnote 20 it is less suitable for the party-level design used here. In particular, this alternative does not extend well to the perspective of insiders, which makes it difficult to compare behavior across insider and outsider status. I discuss this alternative in more detail in Appendix I.2, where I also replicate the main analysis using this specification and show that the results remain largely robust despite the limitations of this measure.

$\theta_{G\setminus j}$ with the position of the insider in a given Council configuration. While this variant is intuitive from the perspective of outsider parties in coalitions with more than two members,Footnote 20 it is less suitable for the party-level design used here. In particular, this alternative does not extend well to the perspective of insiders, which makes it difficult to compare behavior across insider and outsider status. I discuss this alternative in more detail in Appendix I.2, where I also replicate the main analysis using this specification and show that the results remain largely robust despite the limitations of this measure.

To see how ![]() $\Delta$ captures parties’ incentives induced by delegation risks, it is useful to link it to the logic of the unique position orderings discussed earlier. Focusing on party

$\Delta$ captures parties’ incentives induced by delegation risks, it is useful to link it to the logic of the unique position orderings discussed earlier. Focusing on party ![]() $A$,

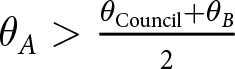

$A$, ![]() $\Delta_A$ is positive for all cases where

$\Delta_A$ is positive for all cases where ![]() $\theta_A \lt \theta_{\text{Council}} \lt \theta_B$, because party

$\theta_A \lt \theta_{\text{Council}} \lt \theta_B$, because party ![]() $A$ is closer to the Council than to its coalition partner. In addition,

$A$ is closer to the Council than to its coalition partner. In addition, ![]() $\Delta_A$ is also positive when

$\Delta_A$ is also positive when ![]() $\theta_B \lt \theta_A \lt \theta_{\text{Council}}$, provided that

$\theta_B \lt \theta_A \lt \theta_{\text{Council}}$, provided that  $\theta_A \gt \frac{\theta_{\text{Council}} + \theta_B}{2}$, matching the idea that incentives depend on how far

$\theta_A \gt \frac{\theta_{\text{Council}} + \theta_B}{2}$, matching the idea that incentives depend on how far ![]() $A$ leans toward one side. Conversely,

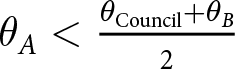

$A$ leans toward one side. Conversely, ![]() $\Delta_A$ is negative when

$\Delta_A$ is negative when ![]() $\theta_A \lt \theta_B \lt \theta_{\text{Council}}$, and in cases where

$\theta_A \lt \theta_B \lt \theta_{\text{Council}}$, and in cases where ![]() $\theta_B \lt \theta_A \lt \theta_{\text{Council}}$ and

$\theta_B \lt \theta_A \lt \theta_{\text{Council}}$ and  $\theta_A \lt \frac{\theta_{\text{Council}} + \theta_B}{2}$. Finally,

$\theta_A \lt \frac{\theta_{\text{Council}} + \theta_B}{2}$. Finally, ![]() $\Delta_A = 0$ if and only if

$\Delta_A = 0$ if and only if ![]() $\theta_A$ lies exactly midway between the two positions.

$\theta_A$ lies exactly midway between the two positions. ![]() $\Delta$ thus precisely reflects the incentive structures implied by the different position orderings as discussed before in a single continuous measure.

$\Delta$ thus precisely reflects the incentive structures implied by the different position orderings as discussed before in a single continuous measure.

To illustrate further, consider the second Faymann cabinet that governed Austria between 2013 and 2016. In the grand coalition of the social democratic SPÖ and the Christian-democratic ÖVP, the former held the labor ministry, making the latter an outsider in the EPSCO Council. The issue position of the ÖVP at the time was ![]() $-2.2$, which is much closer to the average Council position at

$-2.2$, which is much closer to the average Council position at ![]() $-2.7$ than the position of its own coalition partner SPÖ at

$-2.7$ than the position of its own coalition partner SPÖ at ![]() $-3.9$. This is reflected by the

$-3.9$. This is reflected by the ![]() $\Delta$ value for the ÖVP in this policy area which can be computed as

$\Delta$ value for the ÖVP in this policy area which can be computed as  $\Delta_{\text{\"{O}VP}} = \big|{-}2.2 - ({-}3.9)\big| - \big|{-}2.2 - ({-} 2.7)\big| = 1.7 - 0.5 = 1.2$ indicating that it is more closely aligned with the Council position than with the SPÖ. And indeed, the ÖVP during the Faymann cabinet had MEPs on both committees that frequently interface with the EPSCO Council.

$\Delta_{\text{\"{O}VP}} = \big|{-}2.2 - ({-}3.9)\big| - \big|{-}2.2 - ({-} 2.7)\big| = 1.7 - 0.5 = 1.2$ indicating that it is more closely aligned with the Council position than with the SPÖ. And indeed, the ÖVP during the Faymann cabinet had MEPs on both committees that frequently interface with the EPSCO Council.

4.3.2. Bill-specific disagreement

For the analysis of rapporteur assignments, I create an additional measure of disagreement at the level of bills, which is based on parties’ voting behavior in roll-call votes (RCVs) in the EP (Hix et al., Reference Hix, Frantescu, Hagemann and Noury2022). The full procedure is described in Appendix E, but is based on each party’s voting disagreement with the other governing parties (excluding itself if it is in government) across a set of very fine-grained subject codes used to classify EU legislation. For each bill, disagreement is defined as the average of a party’s subject-specific disagreement scores across the subjects to which the bill is assigned. The final measure ranges from full agreement (0) to full disagreement (1).

This data is then matched with the set of legislative proposals from the legislative observatory, which enables me to identify which subject each RCV relates to. These fine-grained subject codes classify legislation in a hierarchical system with over 400 unique codes. Using these codes, I compute each party’s average voting disagreement for every subject. Finally, I use this information to compute the bill-specific disagreement by averaging parties’ subject-specific codes, using those subjects under which the bill is classified. The final measure ranges from full agreement (0) to full disagreement (1).

To illustrate, consider a coalition party with a disagreement value of 1 for a specific bill. This party voted in opposition to its coalition partners on all votes on the subjects relating to the proposed bill. At a value of 0, the party was aligned with its coalition partner on all votes. As one might expect, disagreement in the sample is relatively low and right-skewed with average values of disagreement at 0.1 and 0.15 for government and opposition parties, respectively. Notwithstanding, there is considerable variation and parties do occasionally fully disagree on bills—even among coalition partners.Footnote 21

4.4. Statistical model

To test the theory’s empirical implications, I employ several binary logistic models that regress the indicators of committee membership and rapporteur assignment on the interaction of a party’s status and its ideological misalignment. In the analysis of rapporteur assignments, I also add the bill-specific disagreement in a three-way interaction. For committee appointment, hypothesis H1 thus implies a positive relationship between ![]() $\Delta$ and appointment when parties are outsiders. For rapporteur assignment, H2 also implies a positive relationship when there is disagreement at the bill level.

$\Delta$ and appointment when parties are outsiders. For rapporteur assignment, H2 also implies a positive relationship when there is disagreement at the bill level.

As with all observational studies, these relationships may be confounded by a range of factors. For example, small parties may on average be more misaligned with their coalition partners and have fewer MEPs that can sit on committees. Not accounting for party size would thus lead to a negative relationship between the two key variables in the analysis, which would obfuscate the interpretation. Instead of attempting to control for individual variables such as party size, I opt for very fine-grained fixed effects.

In particular, I successively add fixed effects accounting for cabinet parties and committees as well as their interaction with the legislative term. By adding party and cabinet IDs in an interaction, this accounts for any idiosyncrasies of parties, coalitions, and specific parties within specific coalitions. This is important because the same party may act in a certain way in one coalition but behave fundamentally differently in another. In total, the analysis includes 433 cabinet-party-term fixed effect groups for committee appointments and 701 for rapporteur assignments, while committee-term fixed effects account for 90 and 60 groups, respectively.

By including these fixed effects, all remaining variation in the measure of misalignment stems from differences across committees in terms of policy-specific misalignment and varying party status in the different committees for coalition parties. Thus, misalignment is freed of any variation stemming from overall levels of ideological disagreement among coalition partners. This highlights how restrictive these interaction fixed effects are.

The fixed effects also account for other key drivers of the appointment processes. For example, including cabinet-party fixed effects also controls for European party groups because the former are nested in the latter. Similarly, committee fixed effects take into account differences in the overall size or attractiveness of different committees. By interacting these two sets of fixed effects with the legislative term in the EP, the models further take into account time-varying components relating to each. Especially for parties, this is important because the strength of their delegation typically changes with the EP election heralding the start of the new election.

Finally, the analysis of rapporteur assignment includes a variable controlling for national party strength within the committee. This variable measures the percentage of committee members belonging to the party in question. Including this control helps address differences in baseline committee membership and accounts for the mechanistic effect of proportionality in rapporteur assignments (Kreppel, Reference Kreppel2002; Yoshinaka et al., Reference Yoshinaka, McElroy and Bowler2010). Because this also creates the risk of introducing post-treatment bias as the variable is itself hypothesized to be affected by the very same explanatory factors, I replicate the analysis without this variable in Appendix F.2. This does not affect the results meaningfully.

5. Results

5.1. Committee appointments

Table 1 contains estimates of the committee appointment models. In line with theoretical expectations, they show that outsiders are indeed more likely to be appointed to committees where they are misaligned with their coalition partner relative to others in the Council. This finding is robust across all models, even with the most restrictive fixed effects. Since they account for a broad range of alternative explanations such as EP party group based arguments, party type, or cabinet idiosyncrasies, this can be viewed as strong support in favor of hypothesis H1.

Table 1. Binary logistic regression estimates. DV: Committee appointment. Standard errors in parentheses

+ p ![]() $ \lt $ 0.1, * p

$ \lt $ 0.1, * p ![]() $ \lt $ 0.05, ** p

$ \lt $ 0.05, ** p ![]() $ \lt $ 0.01, *** p

$ \lt $ 0.01, *** p ![]() $ \lt $ 0.001

$ \lt $ 0.001

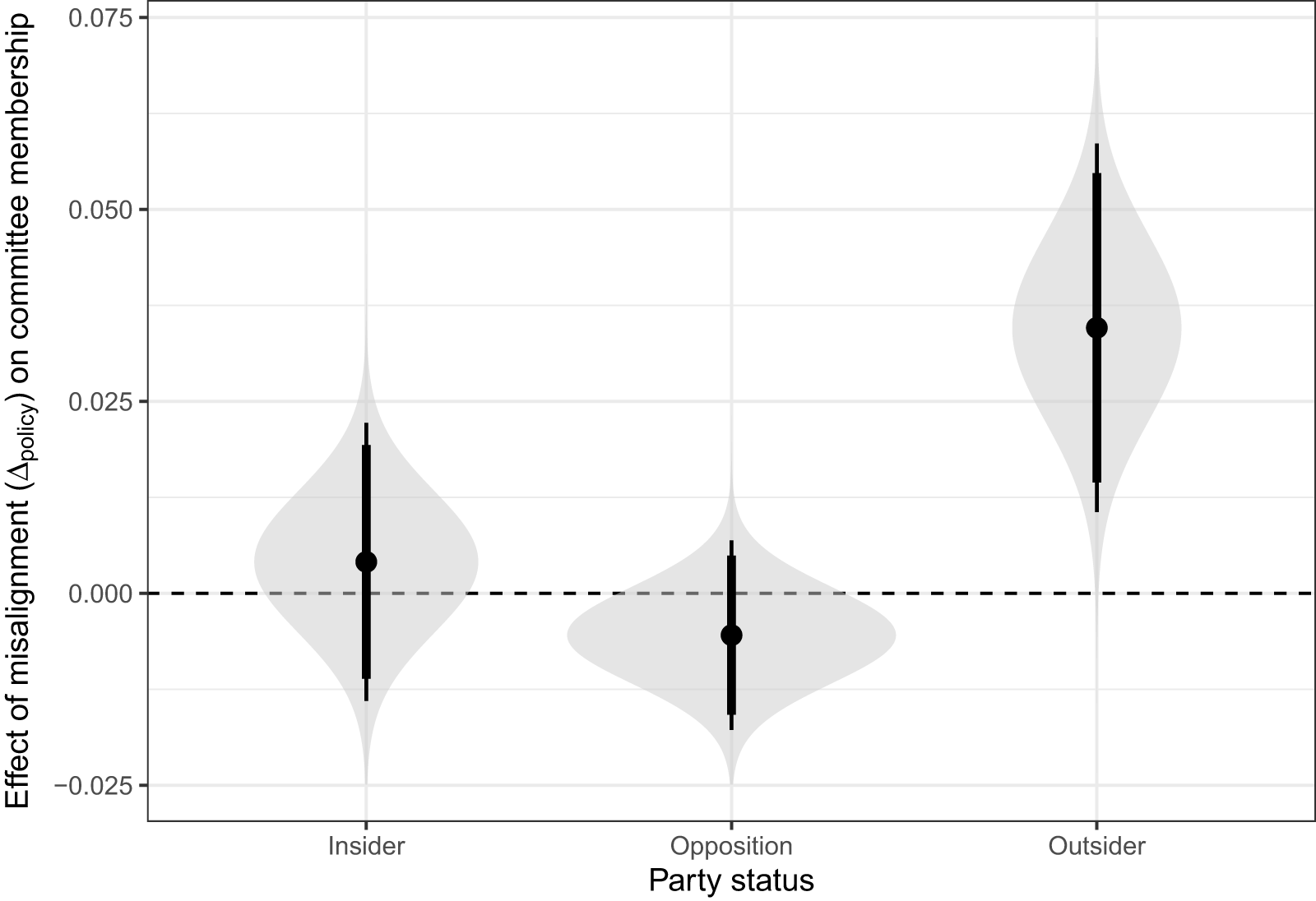

Illustrating the magnitude of this effect, Figure 1 shows the average marginal effects of ideological misalignment by party status. The estimates are based on model 4, which includes the most restrictive fixed effects. Crucially, the figure highlights that ideological misalignment is a key factor for parties when they are sidelined in the Council. Such outsiders are ![]() $3.5$ percentage points (pp) more likely to be appointed to a committee in which they are one standard deviation more misaligned with their coalition partner.

$3.5$ percentage points (pp) more likely to be appointed to a committee in which they are one standard deviation more misaligned with their coalition partner.

Figure 1. Average marginal effects of ![]() $\Delta_{\text{policy}}$ on the predicted probability of committee appointment. Estimates based on model 4 in Table 1. Thick and thin lines indicate

$\Delta_{\text{policy}}$ on the predicted probability of committee appointment. Estimates based on model 4 in Table 1. Thick and thin lines indicate ![]() $90$% and

$90$% and ![]() $95$% confidence intervals, respectively. Shaded eyes represent confidence distributions.

$95$% confidence intervals, respectively. Shaded eyes represent confidence distributions.

As the figure further shows, the same does not hold for parties that are in the opposition or insiders that do have access to the Council negotiations. Especially the null effect for opposition parties is noteworthy. One might expect that these parties seek EP oversight through the EP in policy areas where they are particularly misaligned with their government. An explanation for this finding may be that the opposition has little to gain from reducing its information asymmetry, as it is unlikely to have any influence on the minister’s behavior. Instead, opposition MEPs may be more interested in exercising scrutiny more publicly, e.g. through parliamentary questions (cf. Proksch and Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2011).

5.2. Rapporteur assignments

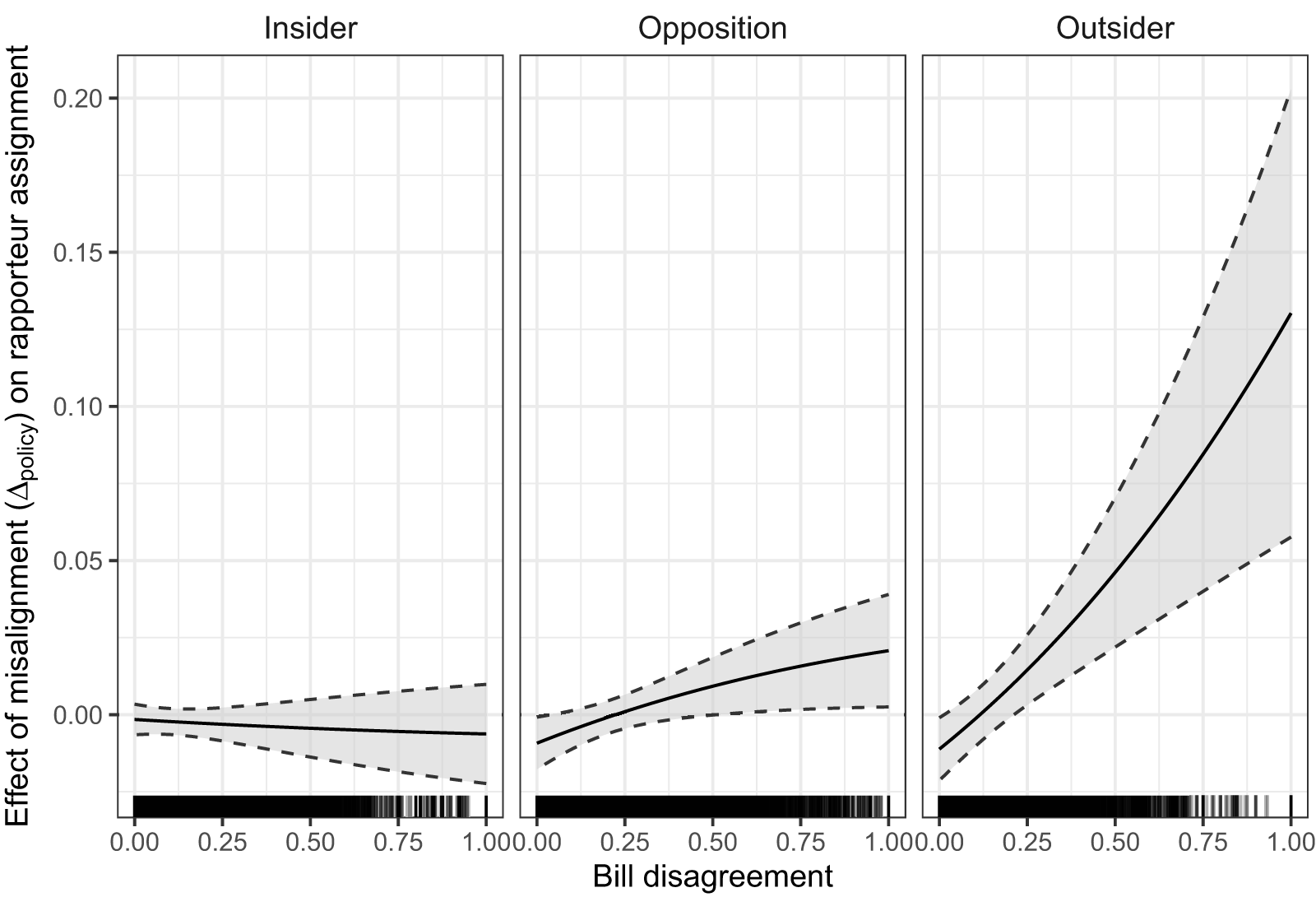

Turning to rapporteur assignment, the models include three-way interactions by adding bill disagreement. This reflects the argument that misaligned outsiders must also make trade-offs at the bill-level. To facilitate the interpretation, I focus on the visual presentation of findings shown in Figure 2 and relegate the full regression table to section F.1 of the Appendix. The figure shows that ideological misalignment does matter for rapporteur assignment of outsiders, but only for bills where they are sufficiently divided with their coalition partner. In these cases, outsiders are substantially more successful in their pursuit of rapporteur assignments. While there is no such effect for insiders, opposition parties seem to follow a similar logic—albeit to a much lesser extent.

Figure 2. Marginal effects of ![]() $\Delta_{\text{policy}}$ on the predicted probability of rapporteur assignment. Estimates based on model A4 in Table A5. Shaded areas represent

$\Delta_{\text{policy}}$ on the predicted probability of rapporteur assignment. Estimates based on model A4 in Table A5. Shaded areas represent ![]() $95$% confidence intervals.

$95$% confidence intervals.

MEPs who sit on committees where they are sidelined in the Council and misaligned with their coalition partner thus take into account further coalition-related dynamics in pursuing rapporteurships. This supports the argument that these MEPs face an additional trade-off at the bill-level. Also, here, this finding is robust to the inclusion of all fixed effects. It thus provides strong evidence in support of hypothesis H2.

As mentioned before, bill disagreement is highly right-skewed. As a result, about 80% of rapporteur assignments are not significantly affected by coalition dynamics. However, for the remaining 20%, the effect is immense. For a bill where outsiders are in full disagreement with their coalition partners, an increase in misalignment by one standard deviation increases the probability of rapporteur assignment by about ![]() $13$ pp. Compared to the baseline, this represents almost a threefold increase in the probability of rapporteur assignment.

$13$ pp. Compared to the baseline, this represents almost a threefold increase in the probability of rapporteur assignment.

5.3. Robustness, sensitivity, and scope

The findings presented here are scrutinized with several additional analyses and tests. First, the models are replicated in alternative statistical frameworks, namely as linear probability models and conditional logit models. The results, reported in Appendix sections G.1 and G.2, confirm that the findings are robust to these modeling choices and alleviate concerns regarding interactions in logit models and incidental parameter bias, respectively. Second, I further examine the two main effects of the multiplicative interactions with binning and kernel estimators in Appendix H. These analyses indicate that the assumptions of common support and linearity are reasonable. Third, I replicate the models using two different versions of the misalignment measure, namely general left-right positions and insider positions, respectively. The results based on left-right positions, shown in Appendix I.1, are similar for committee appointments, though weaker and falling just short of statistical significance. In contrast, the replication yields no comparable effects for rapporteur assignments, suggesting that rapporteurship is more closely driven by specific policy positions than broad ideological alignment. The results of the replication based on relative misalignment with the insider, shown in Appendix I.2, yield similar results to those presented here—albeit slightly weaker. This supports the robustness of the findings while also suggesting that the main definition of relative misalignment performs better. Finally, I assess the sensitivity of the findings to outliers and influential observations. This is particularly relevant for the analysis of rapporteur assignments, where the skewed distribution of bill disagreement raises the possibility that results are driven by a few unusual cases. As shown in Appendix J, the results are very robust to this scrutiny. In summary, these additional analyses lend credence to the robustness of the findings presented here.

6. Conclusion

Coalition governments face significant delegation problems in EU policymaking. This paper has argued that shadowing through the committees of the EP helps sidelined government parties to monitor their coalition partners in the Council. This has implications for MEPs’ committee choice and their pursuit of rapporteur posts within the committees. The empirical analysis provides strong support that MEPs belonging to coalition parties pursue committees and rapporteurships in policy areas where they lack direct access to the Council and where the risks arising from delegation problems are greatest. This provides strong support for the logic of committee shadowing in the EP.

In light of the rising prevalence of coalition governments (Hellström et al., Reference Hellström, Bergman, Lindahl and Gustafsson2024) and the high political authority of the EU (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Lenz and Marks2019), understanding how coalitions behave in EU policymaking is becoming increasingly important. This paper contributes to an emerging literature on how coalition governments affect political behavior within the multilevel system of the EU (see Franchino and Wratil, Reference Franchino and Wratil2019; Kostadinova and Kreppel, Reference Kostadinova and Kreppel2022; Nonnemacher and Spoon, Reference Nonnemacher and Spoon2023) by providing further evidence of the delegation problems that arise in such contexts and by offering a novel approach to oversight. Instead of focusing on domestic-level oversight, I show that the political system of the EU itself provides coalition parties with tools for monitoring their partners. This underscores the importance of identifying the specific institutional settings in which delegation problems emerge. Delegation to individual ministers is a common feature not only in the EU but also in many other international arenas, such as the G7, OECD, WTO, and the Council of Europe, making the insights here relevant beyond just the EU context. Effective oversight mechanisms are crucial for coalition governments in multilevel policymaking, as they help ensure that political compromises are upheld and that ministers adhere to compromises by mitigating delegation problems that could undermine the policymaking process.

This study is not without limitations. Most importantly, by focusing on appointment processes, it cannot fully answer to what extent outsiders can actually prevent ministerial drift in the Council. This is a difficult question—both conceptually and empirically—that deserves further attention in future research. The lack of transparency of the Council and in particular the lack of meaningful voting recordsFootnote 22 make it challenging to assess actual ministerial behavior in the Council. Ongoing debates in the study of domestic coalition policymaking about the effectiveness of committee shadowing in preventing ministerial drift (Sieberer and Höhmann, Reference Sieberer and Höhmann2017; Fortunato et al., Reference Fortunato, Martin and Vanberg2019; Krauss et al., Reference Krauss, Praprotnik and Thürk2021) further highlight the complexity of this issue. Nonetheless, committee appointments are a meaningful outcome in their own right. Unlike analyses at the national level, this study also shows that membership itself matters.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2025.10072. To obtain replication material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/7FTACV.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Zurich Political Economy Seminar Series (Spring 2025), the 2025 ECPR Conference of the Standing Group on Parliaments, and the 2025 ECPR General Conference. I am grateful to Tina Freyburg, Jonathan Klüser, Giorgio Malet, Frank Schimmelfennig, Jonathan Slapin, Georg Vanberg, David Willumsen, as well as the participants of the EUP Winter Retreat 2024 for their support and constructive feedback. I also thank Simon Hix for sharing the MEP survey data. Finally, I am indebted to the editor and the reviewers for their constructive comments. Any remaining errors are my own.

Competing interests

The author declares none.