1. Introduction

Contra graecum, against the Greek, is a phrase used in the critical apparatus of the so-called Oxford Vulgate, a scholarly edition of the Vulgate text which was published in the first half of the twentieth century.Footnote 1 Even today, the Oxford Vulgate still offers the most extensive presentation of textual variants of the Latin tradition of many books of the New Testament. In addition to over fifty Vulgate witnesses, the critical apparatus also includes information from Old Latin manuscripts, early Christian authors and additional references to printed editions. Its editorial text of the Vulgate, however, has been replaced by that of the so-called Stuttgart Vulgate.Footnote 2 One special feature of the apparatus is the numerous references to Greek sources, in particular remarks concerning the relation of the Greek and Latin trad-ition. In this regard, the phrase contra graecum is used to indicate when certain manuscripts, individual early Christian authors or the entire Latin attestation reads a text that is not (or only rarely) present in the Greek witnesses. It is this phenomenon of the Greek and Latin witnesses fundamentally differing which is the focus of this contribution. Specifically, for illustrative purposes, three examples from 1 Corinthians are discussed, a letter for which both the Editio Critica Maior and the Vetus Latina edition are currently being produced at KU Leuven.

2. 1 Cor 7.33–4 and the Case of a Passive Perfect Dividing Verses

The first example for a fundamental difference between the Greek and Latin starts with a difference in editions. As is well known, the current chapter and verse divisions of the New Testament are not ancient. Modern chapters follow a division from the thirteenth century, traditionally connected with Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury (1207–28). The verse divisions largely follow that of the printed edition of Robert Estienne (lat. Robertus Stephanus) in 1551. That edition presents not only a Greek text but also two versions of the Latin text, Erasmus’ Latin translation in the outer column and a Vulgate version in smaller print in the inner column.Footnote 3 With one exception in 1 Corinthians, the Nestle-Aland 28/UBS 5 editions follow this verse division, in line with von Soden’s edition of 1913.Footnote 4 Already in Estienne’s edition of 1551, the verse number at 1 Cor 7.33–4 differs between the Greek and the Latin text. The following extracts include the verse division and punctuation in Estienne 1551, in Nestle-Aland 28 and in the Stuttgart Vulgate (5th edition).

Estienne 1551 (presenting mainly the Majority Text)

7.33 ὁ δὲ γαμήσας μεριμνᾷ τὰ τοῦ κόσμου, πῶς ἀρέσει τῇ γυναικί. μεμέρισται ἡ γυνὴ καὶ ἡ παρθένος. 34 ἡ ἄγαμος μεριμνᾷ τὰ τοῦ κυρίου, ἵνα ᾖ ἁγία καὶ σώματι καὶ πνεύματι· ἡ δὲ γαμήσασα μεριμνᾷ τὰ τοῦ κόσμου, πῶς ἀρέσει τῷ ἀνδρί.

Latin on the outer side (Erasmus)

7.33 at qui duxit uxorem, solicitus est de his quae sunt mundi, quomodo placiturus sit uxori, et divisus est. 34 et mulier caelebs et virgo, curat ea quae sunt Domini, ut sit sancta cum corpore, tum spiritu: contra, quae nupta est, curat ea quae sunt mundi, quomodo placitura sit viro.

Latin on the inner side (Vulgate)

7.33 qui autem cum uxore est, solicitus est quae sunt mundi, quomodo placeat uxori, et divisus est. 34 et mulier innupta et virgo, cogitat quae Domini sunt, ut sit sancta et corpore et spiritu: quae autem nupta est, cogitat quae sunt mundi, quomodo placeat viro.

Nestle-Aland 28

7.33 ὁ δὲ γαμήσας μεριμνᾷ τὰ τοῦ κόσμου, πῶς ἀρέσῃ τῇ γυναικί, 34 καὶ μεμέρισται. καὶ ἡ γυνὴ ἡ ἄγαμος καὶ ἡ παρθένος μεριμνᾷ τὰ τοῦ κυρίου, ἵνα ᾖ ἁγία καὶ τῷ σώματι καὶ τῷ πνεύματι ἡ δὲ γαμήσασα μεριμνᾷ τὰ τοῦ κόσμου, πῶς ἀρέσῃ τῷ ἀνδρί.

Stuttgart Vulgate (the verse division matches that of the Oxford Vulgate)

7.33 qui autem cum uxore est sollicitus est quae sunt mundi quomodo placeat uxori et divisus est 34 et mulier innupta et virgo cogitat quae Domini sunt ut sit sancta et corpore et spiritu quae autem nupta est cogitat quae sunt mundi quomodo placeat viro.

The different verse divisions, and even more so the different punctuations hint at the editorial interpretation of a textual attestation that is complex and diverse. The main issue affecting the sentence and verse division is the interpretation of the passive perfect form μεμέρισται, which can refer to both the masculine ὁ γαμήσας and the feminine ἡ γυνή. Both interpretations are reflected in the punctuation of modern editions. Nestle-Aland 28 interprets μεμέρισται as a masculine form with the subject ὁ γαμήσας (‘the married man is divided [in his interests]’). Estienne in 1551 reads it together with ἡ γυνὴ καὶ ἡ παρθένος (‘divided is the woman and the virgin’).

To understand this, the Latin attestation yields helpful information. As so often the case when it comes to the so-called versions (i.e. early translations of the Greek text), they are a useful source not only for understanding the transmission of the New Testament text but also for its interpretation.Footnote 5 This is in particular the case in those instances where the target language cannot fully mirror the source text. In Latin, the passive perfect form consists of the auxiliary verb esse (‘to be’) and the perfect passive participle, which is formed as masculine, feminine or neuter. In the Latin transmission of 1 Cor 7.33–4, both the masculine (divisus) and the feminine form (divisa) are attested, the latter in several Old Latin witnesses.Footnote 6 The reading divisa led to an interpretation of the passage in various Christian authors who discuss a difference between a(n) ‘(unmarried) woman’ and a ‘virgin’. One of these authors is Jerome who, however, is aware of different attestations and interpretations of the passage. In Contra Iovinianum 1.13.260, he writes:

nunc illud breviter admoneo, in Latinis codicibus hunc locum ita legi: ‘divisa est mulier et virgo’. quod quamquam habeat suum sensum et a me quoque pro qualitate loci sic edissertum sit, tamen non est apostolicae veritatis. si quidem apostolous ita scripsit ut supra transtulimus: sollicitus est quae sunt mundi, quomodo placeat uxori, et divisus est.

Now I briefly remind [you] of this, that in the Latin manuscripts this passage is read as follows: ‘divided is the woman and the virgin’. Although this has its own meaning and has been interpreted in that way by me too according to the context of the passage, it does not testify to apostolic truth. For the apostle certainly wrote as we have translated above: ‘he is anxious about the affairs of the world, how to please his wife, and he is divided’.Footnote 7

Jerome clearly favours the masculine reading as the intended reading of Paul. Yet that did not stop him from also finding sense and meaning in the feminine form, divisa. Also, the Vulgate favours the masculine, with Vulgate editions consequently reading it as the end of the sentence in verse 33. In the Greek attestation, however, it is the (later) Majority Text that connects μεμέρισται with the following feminine noun, which is where Estienne’s edition of 1551 also places it. The rendering in Nestle-Aland 28, however, is divided in its ‘loyalty’: the punctuation identifies μεμέρισται as part of the sentence in verse 33, yet it is placed within verse 34. Much more could be said on the editorial texts of the Greek and Latin and on the very complex textual attestation of this passage, ‘one of the most widely known textual problems in the Pauline epistles’.Footnote 8 In the context of this contribution, however, it is worth reflecting on the founding moment of modern verse divisions. From the very beginning in 1551, the Greek and Latin verse traditions go against each other, reflecting different attestations of the text. When editing a text, editors must make decisions. With that in mind, it seems that Estienne – just like Jerome – was aware of different interpretations of the text but did not see any need to harmonise them in his edition, let alone in his verse division.

3. 1 Cor 15.5 and the Case of the Disciples

Another example of a place where the Latin tradition goes against the Greek is 1 Cor 15.5, concerning the appearance of Christ to his disciples. In the Greek transmission, Christ appeared to ‘the twelve’. By contrast, in the Latin transmission, he appeared to eleven, a number which the Latin manuscript tradition consistently reads contra graecum.

Nestle-Aland 28: καὶ ὅτι ὤφθη Κηφᾷ εἶτα τοῖς δώδεκα

Stuttgart Vulgate: et quia visus est Cephae et post haec undecim

There are only a few exceptions among the extant Greek manuscripts in which ‘eleven’ is read instead of ‘twelve’. The critical apparatus of Nestle-Aland 28 lists the first hand of Codex Claromontanus, Codex Augiensis, and Codex Boernerianus. Metzger in his Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament also mentions minuscules 330 and the first hand of what he still knew as manuscript 464, but which has now been reunited with 252 in the Kurzgefasste Liste der griechischen Handschriften des Neuen Testaments. Based on collations of test passagesFootnote 9 and ongoing work on the Editio Critica Maior (ECM) of 1 Corinthians, also the majuscule 0150 and 11 minuscules (43, 378, 451, 469, 935, 1108, 1609, 1722, 2110, 2400 and 2716) can be added to this list of Greek manuscripts which read ‘eleven’.Footnote 10

3.1 The Bilingual Evidence

The earliest witnesses reading ‘eleven’ are Greek-Latin bilingual manuscripts, which are a fascinating group of texts in their appearance and in their potential mutual influence. In almost all instances, the two languages in such bilingual manuscripts are not a direct translation of each other. However, they often portray awareness of the other language. This can, for example, be seen when the text in both languages is aligned in so-called sense-lines, that is corresponding units of text of various lengths. Mutual influence between the languages can also be seen when readings are adapted and when glosses and corrections are added, be it by the first hand or at a later point.Footnote 11

The oldest of the three bilinguals listed in Nestle-Aland 28 as a witness of the reading ‘eleven’ is Codex ClaromontanusFootnote 12 (GA 06, VL 75, D/d; Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, grec 107, 107A, and 107B), which was copied probably in Southern Italy around the middle of the fifthFootnote 13 century ce. The text is presented in sense-lines on facing pages, with the Greek written in majuscule script on the left, and the Latin written on the right page in uncial script. The second bilingual is Codex Boernerianus (GA 012, VL 77, G/g; Dresden, Sächsische Landesbibliothek, A. 145b), which was copied in St. Gall in 860/870 ce. It is an interlinear manuscript, meaning that the Latin text in insular minuscule script is written above the Greek text. The Latin is mainly based on that Greek text and follows the Greek grammar and word order. Thus, there are unique readings in the Latin not otherwise attested in extant manuscripts (for which an example is given in the third example below). The manuscript is also known for its many pairs of alternative readings in the Latin part, usually separated by vel (‘or’). The third is Codex Augiensis (GA 010, VL 78, F/f; Cambridge, Trinity College, B.17.1), copied in Reichenau in the last third of the ninth century ce. It presents the text in two columns, with Greek always being in the inner and broader column and Latin always being in the outer and narrower column of each page. As such, this arrangement is different to the more common presentation in two columns in other bilingual manuscripts, where one language is usually always on the left and the other always on the right. The Greek part of Codex Augiensis is either a direct copy of Codex BoernerianusFootnote 14 or comes from the same source. The Old Latin text is close to Vulgate readings. These are the readings at 1 Cor 15.5:

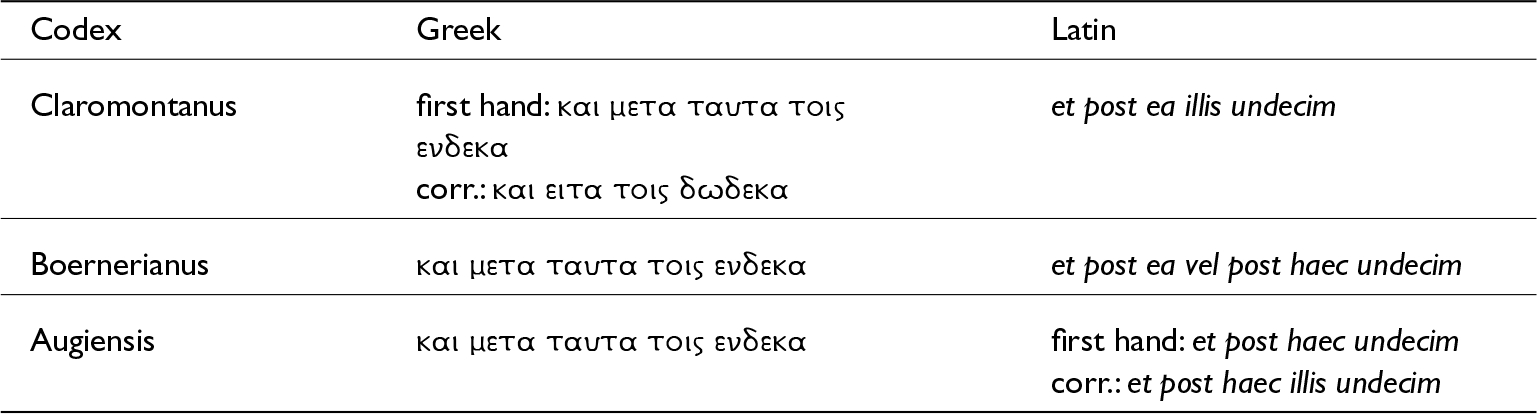

Table 1. Bilingual evidence at 1Cor 15.5

These readings show that there is cross-influence between the languages. Not only do all of them read the number eleven in Greek and Latin, but they also share the same prepositional phrase beforehand. The Latin side reads either et post haec or the alternative et post ea,Footnote 15 with Codex Boernerianus reading both and introducing the alternative reading with vel (‘or’). Both the et and the following phrase go against the Greek attestation except for these three bilinguals, where the Greek side (καὶ μετὰ ταῦτα) corresponds with the Latin. The rest of the Greek transmission reads either εἶτα (e.g. in P46) or ἔπειτα (e.g. in Codex Sinaiticus), which usually is translated as deinde in Latin.Footnote 16 Yet, as the apparatus of the Oxford Vulgate says at 1 Cor 15.5, apud latinos non redditur: neither εἶτα nor ἔπειτα is rendered in Latin.

As mentioned above, the Greek attestation for ἕνδεκα is infrequent and the oldest extant witnesses are Greek–Latin bilingual manuscripts.Footnote 17 While accommodation towards one language has been detected in these bilinguals, Fröhlich and other scholars of the Latin bible observed that this usually happens ‘at the expense of the Latin text’.Footnote 18 In 1 Cor 15.5, however, such an accommodation seems unlikely, given that the overall Latin attestation for eleven is predominant and the overall Greek attestation for the number eleven is weak. The non-bilingual manuscripts known today which read ἕνδεκα are 14 in number and several of them are suspected or known to be closely related, including the commentary manuscripts 0150 and 2110.Footnote 19 Also the Greek rendering καὶ μετὰ ταῦτα does not seem attested outside the bilinguals and may rather have been influenced by the Latin tradition in which this reading is strongly attested.Footnote 20

3.2 Evidence in Early Christian Authors

While evidence for the number twelve in the Latin biblical manuscripts is almost inexistent,Footnote 21 there is awareness of the number twelve in Latin early Christian authors.Footnote 22 For example, Augustine discusses the passage in De Consensu Evangelistarum 3.25.70–1,Footnote 23 when he compares the different stories of appearances of Jesus Christ after his resurrection in the gospels and in Paul. His purpose is to show

‘not only that the congruence of the four evangelists shines forth from this matter, but also that they agree with Paul the apostle, who speaks about this matter in the 1 Epistle to the Corinthians’.

… non solum ut elucescat etiam ex hac re convenientia quattuor Evangelistarum, verum etiam ut cum Paulo apostolo consonent, qui de hac re in Prima ad Corinthios Epistula ita loquitur (3.25.70; CSEL 43: 366).

What follows is a harmonising discussion of the account of the four Gospels and Paul, which Augustine concludes by stating that there are no discrepancies in the accounts. After this, he cites 1 Cor 15.3–8. His commentary on the passage shows that he was aware of both readings, eleven and twelve.Footnote 24

sic autem non apparet quibus duodecim, quemadmodum nec quibus quingentis. fieri enim potest, ut de turba discipulorum fuerint isti duodecim nescio qui. nam illos quos apostolos nominavit non iam duodecim, sed undecim diceret, sicut nonnulli etiam codices habent, quod credo perturbatos homines emendasse putantes de illis duodecim apostolis dictum, qui iam Iuda extincto undecim erant. sed sive illi codices verius habeant qui undecim habent, sive alios quosdam duodecim discipulos Paulus velit intellegi, sive sacratum illum numerum etiam in undecim stare voluerit, quia duodenarius in eis numerus ita mysticus erat, ut non posset in locum Iudae nisi alius, id est Matthias, ad conservandum sacramentum eiusdem numeri subrogari; quodlibet ergo eorum sit, nihil inde existit quod veritati vel istorum alicui veracissimo narratori repugnare videatur (3.25.71; CSEL 43: 370–1).

But thus, it is not clear to which twelve [Christ appeared], just as (it is) not (clear) to which five hundred. For it could be that these twelve were some from the crowd of the disciples; I do not know which. For he could no longer refer to those whom he called apostles as twelve but as eleven, as some codices have it and which I believe some confused people emended, thinking that it was said about the twelve apostles who were now eleven after Judas had died. But whether those codices have a more accurate reading which have eleven, or whether Paul wanted some other twelve disciples to be meant, or whether he would have wanted the sacred number also to remain in the eleven, because among them the number twelve was so mystical that in order to preserve the mystery of that number no one else could be elected in Judas’ place except MatthiasFootnote 25 ; – now whichever of these may be the case, nothing results from it that could seem to contradict the truth or any most truthful narrator among them.

The question of how the number twelve can refer to a group of eleven people is also discussed elsewhere by Augustine. In his Quaestiones in Genesim 1.117.4, Augustine explains the use of the number twelve as a synecdoche. That is a figure of speech which refers either to a part of something in place of the whole (pars pro toto) or to the whole in place of a part (totum pro parte).Footnote 26

Nulla tamen est facilior solutio quaestionis huius, quam ut per synecdochen accipiatur. Ubi enim pars maior est aut potior, solet eius nomine etiam illud conprehendi quod ad ipsum nomen non pertinet. Sicut ad duodecim apostolos iam non pertinebat Iudas, qui etiam mortuus fuit cum dominus resurrexit a mortuis, et tamen ipsius duodenarii numeri nomen apostolus in epistula sua tenuit, ubi ait eum adparuisse ‘illis duodecim’. Cum articulo enim hoc Graeci codices habent, ut non possint intellegi quicumque duodecim, sed illi in eo numero insignes.

For there is no easier solution to this question than to understand it by means of a synecdoche. For where the part is greater or more important, one usually understands by its name also that which does not belong to the name itself. Judas, who was already dead when the Lord rose from the dead, thus no longer belonged to the twelve apostles. And yet the apostle retained the name of the very number twelve in his letter, where he says that he (= Christ) appeared to ‘the twelve’ [1 Cor 15.5]. For the Greek codices have the article here, so that not any twelve can be meant, but those identified in that number.Footnote 27

These examples from Augustine show that the absence in extant biblical manuscripts does not imply an absence of awareness of different readings. It is noteworthy that despite the discrepancy, Augustine did not see the need to disregard one of them. On the contrary, he found meaning in both.

3.3 Concluding Thoughts on 1 Cor 15.5

In his Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (19942: 500), Metzger said about this passage:

Instead of recognizing that δώδεκα is used here as an official designation, several witnesses, chiefly Western, have introduced the pedantic correction ἕνδεκα.

Given that the entire Latin tradition reads this ‘pedantic’ rendering as well, three more thoughts may be added. First, the different attestations in each language tradition are strong. Secondly, Latin patristic literature attests to an awareness of the variant readings in the manuscript tradition and potentially also a difference between Greek and Latin. Thirdly, the discrepancy in the textual attestation is not seen as a problem or as something that needs to be corrected. On the contrary, a harmonising treatment of textual discrepancies is well known from early Christian authors. This reflects a theological understanding that textual variants would not compromise the truth of scripture.Footnote 28

4. 1 Cor 14.11 and the Case of the Barbarian

The third example for a Latin reading contra graecum is 1 Cor 14.11 which stands in a passage on speaking in tongues and different languages and their intelligibility (1 Cor 14.6–14). The question is who the barbarian in 1 Cor 14.11 actually is. The answer differs depending on the language. The Greek text identifies two different kinds of barbarians.

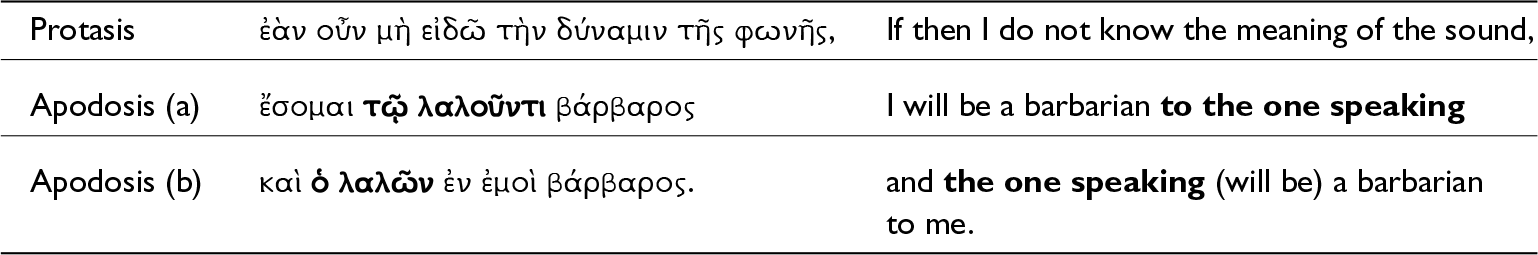

Table 2. Greek text at 1 Cor 14.11

The first barbarian (a) is the listener who does not understand the speaker’s words, as the protasis implies. The second barbarian (b) is the speaker who is incomprehensible to the listener. In both instances, the listener is the first-person narrator of the protasis who does not understand the meaning. In the Greek rendering, there is one scene, one act of communication: one speaker, one listener. Both the listener and the speaker are described respectively as barbarians in the eyes of the other. In the Latin tradition, however, the case is different. As a starting point, the Vulgate text is given and translated below next to the Greek.

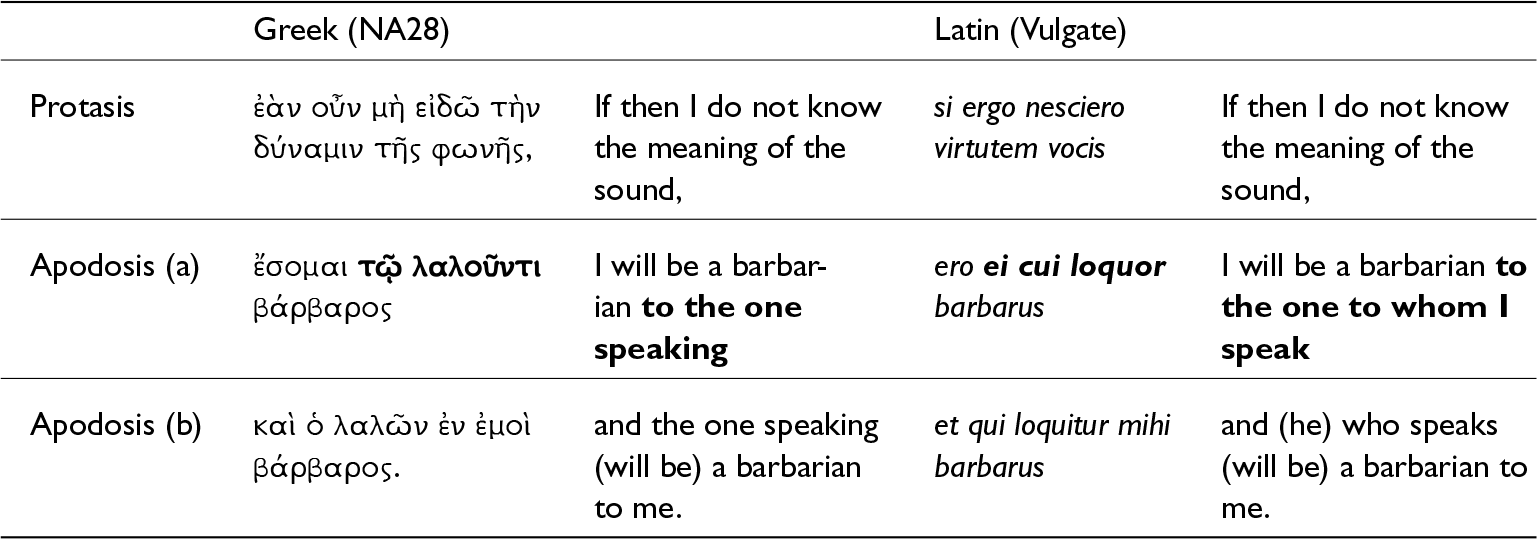

Table 3. Greek and Latin text at 1 Cor 14.11

In Latin, there are thus also two barbarians, but both are the speakers: once it is the first-person narrator (a), once it is another person (b). Instead of one act of communication, there are two acts, two speakers. The main difference between the Greek and Latin is in the first part of the apodosis. In the Greek, the speaker is the other person who is speaking. In the Latin (and contra graecum), the speaker is the first-person narrator of the protasis. The scenario of the first apodosis is thus that the speaker himself does not understand what he is saying, and it is this which makes him a barbarian to the listener. Before asking the question under what circumstances a speaker may not understand his or her own words, a closer look at the Latin textual transmission is in order.

4.1 The Manuscript Attestation

(a) Contra graecum

The Latin attestation is consistent in identifying two speakers as the barbarians. The two Greek participles are rendered as relative clauses. This is not unusual as such. On the contrary, there is a tendency in Latin to replace participles by relative clauses with a finite verb. This occurs regularly also when the Latin could have replicated the Greek participle, as is the case here (λαλοῦντι > loquenti; λαλῶν > loquens). The predominant Latin rendering of 1 Cor 14.11 is attested already prior to the Vulgate in various Old Latin manuscripts.

VL 54, 58, 78, (88): si ergo nesciero virtutem vocis ero ei cui loquor barbarus et qui loquitur mihi barbarus

VL 76: si ergo ignorem virtutem vocis ero ei cui loquor barbarus et qui loquitur mihi barbarus

Without a change in meaning, Codex Gigas (VL 51) reads the first relative clause without an antecedent, and the so-called Freising Fragments (VL 64), which are lacunose in the first part, read the pronoun ille as an antecedent in the second part.

VL 51: si ergo nesciero virtutem vocis ero cui loquor barbarus et qui loquitur mihi barbarus

VL 64: [… e]t ille qui loquitur mihi ba[r]barus

Unlike in the previous example from 1 Cor 15.5, where the early bilinguals read the same text in the Greek and Latin, here in 1 Cor 14.11 all bilinguals which preserve text in both languages do not correspond to each other (with the exception of Codex Boernerianus as described below).Footnote 29

(b) Cum graeco

The Latin reading in 1 Cor 14.11 contra graecum is remarkably strong: as far as the author can see, none of the Greek extant witnesses reads a text similar to the Latin. Whereas on the Latin side, only two manuscripts read a text that represents the Greek tradition.

The first is a bilingual witness, the interlinear Greek–Latin Codex Boernerianus. As mentioned already above, this codex offers a direct translation of the Greek text present in the same manuscript, so that the Latin regularly follows the Greek grammar and word order. It is therefore not surprising but rather to be expected that this one manuscript has a literal rendering matching the Greek tradition, not the attestation of other Latin manuscripts. In the first apodosis, the participle in Greek is replicated in Latin (loquenti). In the second apodosis, the Greek participle is rendered as a relative clause with the literal replication of the Greek participle in Latin (loquens) given as an alternative reading introduced with vel (‘or’).

GA 012: ἐὰν οὖν μὴ γινώσκω τὴν δύναμιν τῆς φωνῆς, ἔσομαι τῷ λαλοῦντι βάρβαρος καὶ ὁ λαλῶν ἐμοὶ βάρβαρος

VL 77: si ergo nesciero virtutem vocis ero loquenti barbarus et is qui loquitur vel loquens mihi barbarus

If then I do not know the meaning of the sound, I will be a barbarian to the one speaking and he, who speaks, or the speaking one, a barbarian to me.

The so-called anonymous Budapest commentary VL 89 is the second Latin witness which reads a text reflecting the Greek meaning, both in its lemma text and in its commentary.Footnote 30 There, the first participle in Greek (τῷ λαλοῦντι) is rendered ei qui loquitur (‘to him who speaks’), thus differently than in VL 77. The second apodosis corresponds to VL 77 insofar as the same antecedent, the personal pronoun is, is read ahead of the relative clause, which differs from other renderings in the Old Latin witnesses (ille in VL 64 but no antecedent in VL 51, 54, 58, 76, 78 and 88).

VL 89: igitur si nesciero virtutem vocis ero ei qui loquitur barbarus et his (l. is) qui loquitur mihi barbarus

From the perspective of textual history, VL 89 is an interesting witness.Footnote 31 It transmits the biblical text as lemmata within a commentary, which was probably originally composed in Rome around the year 400 ce.Footnote 32 It mainly preserves Old Latin readings without those adaptations towards the Greek which can be seen in bilinguals and largely without corrections towards typical Vulgate readings. In the case of 1 Cor 14.11, however, VL 89 is the most ‘Greek’ witness of all the extant manuscripts. Without an accompanying Greek text of a bilingual to account for the Greek rendering in Latin (as in Codex Boernerianus), there is not much further explanation as to why this one witness reads a text cum graeco and contra latinum.Footnote 33

4.2 Early Christian Renderings

It is now time to return to the Latin rendering that a speaker appears as a barbarian to the listener when the speaker (!) does not understand his or her own words. One can argue that the Latin tradition might primarily think of speaking in tongues when reading 1 Cor 14.11, and not of a known human language in general or of the sound and meaning of signals (as in 1 Cor 14.7, 8, 10). At this point, it would be helpful to consider some non-Christian sources and their use and meaning of the word ‘barbarian’ and the intelligibility of languages, both in documentaryFootnote 34 and literaryFootnote 35 sources. However, as these would be studies in their own right, the focus here shall remain on early Christian interpretations of the biblical passage. Unlike in the previous example regarding the question of eleven or twelve in 1 Cor 15.5, the author has not been able to find any passage where variant readings are discussed by early Christian authors in relation to 1 Cor 14.11. However, in Ambrose, there seems to be at least awareness of the Greek biblical rendering according to which both speaker and listener are barbarians. In De excessu fratris Satyri 2.106,Footnote 36 he writes:

non enim satis est tubam videre nec sonum eius audire, nisi proprietatem sonitus intellegas. Etenim si incertam vocem det tuba, quomodo quis parabit se ad bellum? Unde oportet vocis tubae nos scire virtutem, ne videamur barbari, cum tubas huiusmodi aut audimus aut loquimur. Et ideo cum loquimur, oremus, ut eas nobis spiritus sanctus interpretetur (2.106, CSEL 73: 308)

For it is not enough to see the trumpet or to hear its sound unless you understand the proper signification of the trumpet sound. For if the trumpet gives an unclear tone, how will anyone prepare himself for war? Therefore, it is necessary that we understand the meaning of the tone of the trumpet, so that we do not appear as barbarians when we either hear or produce [literally: speak] such trumpet sounds. And so, when we speak, let us pray that the Holy Spirit interprets these [sounds] to us.

Ambrose thus emphasises that in order not to appear as a barbarian, the understanding of a sound is crucial for both the listener and the speaker. This reflects again the Greek rendering in 1 Cor 14.11. With a reference to 1 Cor 14.13, he also expresses the necessity for prayer to be able to understand one’s own words.

Vice versa, the idea that the speaker needs to understand himself is also expressed in the Greek tradition by John Chrysostom in his Homily 35 on 1 Corinthians (CPG 4428; PG 61: 299–300). There, he also comments on 1 Cor 14.11 and refers to it once more after having cited 1 Cor 14.13–15:

Εἶδες πῶς κατὰ μικρὸν τὸν λόγον ἀνάγων δείκνυσιν, ὅτι οὐκ ἄλλοις ἄχρηστος μόνον ὁ τοιοῦτος, ἀλλὰ καὶ ἑαυτῷ, εἴ γε ὁ νοῦς αὐτῷ ἄκαρπος; Ἄν γάρ τις φθέγγηται μόνον τῇ Περσῶν γλώσσῃ, ἢ ἑτέρᾳ τινὶ ἀλλοτρίᾳ, μὴ εἰδῇ δὲ ἃ λέγει, ἄρα καὶ ἑαυτῷ λοιπὸν ἔσται βάρβαρος, οὐχ ἑτέρῳ μόνον, διὰ τὸ μὴ εἰδέναι τὴν δύναμιν τῆς φωνῆς. Καὶ γὰρ ἦσαν τὸ παλαιὸν καὶ χάρισμα εὐχῆς ἔχοντες πολλοὶ μετὰ γλώττης, καὶ ηὔχοντο μὲν, καὶ ἡ γλῶττα ἐφθέγγετο, ἢ τῇ Περσῶν, ἢ τῇ Ῥωμαίων φωνῇ εὐχομένη, ὁ νοῦς δὲ οὐκ ᾔδει τὸ λεγόμενον. Διὸ καὶ ἔλεγεν, Ἑὰν προσεύξωμαι τῇ γλώττῃ, τὸ πνεῦμά μου προσεύχεται, τοῦτ’ ἔστι, τὸ χάρισμα τὸ δοθέν μοι καὶ κινοῦν τὴν γλῶτταν, ὁ δὲ νοῦς μου ἄκαρπός ἐστι.

Have you seen how he [= Paul], gradually bringing forward the argument, shows that such a person is not only useless to others but also to himself, if indeed ‘his mind is unproductive’ to him? For if somebody speaks only in the Persian tongue or in any other foreign tongue but does not understand what he is saying, then he will be a barbarian to himself too, not only to the other, because he does ‘not know the meaning of the sound’. For indeed there were many in the past who also had the gift of prayer with a tongue. And they prayed, and the tongue uttered a sound while praying either in the Persian or the Roman language. But the mind did not understand what was being said. Therefore, he also said: ‘If I pray in a tongue, my spirit prays’, that is the gift given to me and moving the tongue, ‘but my mind is unproductive’.

This may not necessarily mean that an equivalent to the Latin reading of 1 Cor 14.11 was also present in the Greek. However, it may show that, when reading the entire passage in context, the expectation that the speaker too would need to understand his own words was present in Greek interpretations.Footnote 37 It may be that such an understanding may have become predominant and caused the Latin attestation. As pointed out above, versions are often a useful source for analysing how a New Testament passage was read and interpreted in a certain context. It seems that the Latin tradition predominantly interpreted 1 Cor 14.11 in relation to speaking in tongues (1 Cor 14.9, 13). The Greek, however, in its rendering still includes other languages and sounds (1 Cor 14.7, 8, 10).

4.3 Concluding Thoughts on 1 Cor 14.11

Metzger does not comment on 1 Cor 14.11 in his Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament. Perhaps, this is inherent in the nature of the example: why would a consistent transmission in Greek look at potential other versional readings? Moreover, it is even standard practice in creating critical editions, including the Editio Critica Maior, to look only at those instances in the versions which support an extant Greek variant reading. From such a perspective, the Latin rendering of 1 Cor 14.11 is useless to a Greek critical edition. And vice versa, why should a Latin critical edition with such a strong attestation contra graecum bother too much about a Greek transmission that does not provide in its extant witnesses a Vorlage, an exemplar, for the Latin reading? Yet once more it is the bilingual evidence that makes one pause and look deeper. For the Latin wording may be against the Greek textual evidence, but it is not necessarily against a Greek interpretation of the entire passage. This is particularly noticeable when reading 1 Cor 14.11 through the lenses of speaking in tongues in 1 Cor 14.9, 13, as executed both in Latin (Ambrose) and in Greek (Chrysostom).

5. Conclusions: pars pro toto

The three examples of differences between the Greek and the Latin transmission of the New Testament in this contribution were discussed from the perspective of the Latin, which reads a text contra graecum, potentially with interpretative consequences. The first example was from modern printed editions and the challenges that come with punctuation and verse division at a place where the textual transmission is complex. Unlike scholars who talk about variant readings in their presentations or in articles, editors have to make decisions and have to select one variant (or two) in their editorial text. While they can still tell the more complex story in their critical apparatus and commentary, they have to trust that scholars using their editorial text will understand that it is a text of the New Testament, not the text.

The second example was about the different number of people to whom Christ appeared in 1 Cor 15.5. It was an example where the overall Latin transmission is consistent with only very little support in the Greek tradition, which may have been influenced from the Latin altogether. Perhaps Metzger is right, and the Latin tradition here is simply pedantic. However, it is often in exactly those small details that the big questions can be asked. Where do these differences come from? Why have they never been adapted to each other? The answer to the latter is not that people were not aware of the differences but rather that people did not understand them as a threat or as diminishing the meaning of the biblical text, as was explicitly visible in some of the early Christian authors.

The third example from 1 Cor 14.11 and the case of the barbarian speaker was one where there is no support in Greek for the Latin reading, and, moreover, where discussion in the early Christian authors does not provide too much additional insight. One could argue that it is usually the case that the speaker also understands his or her own words (or at least has an idea what he or she wants to say) when speaking in another language. Therefore, a point can be made that the Latin rendering, which implies that the speaker does not understand his own words, has ‘frozen’ or ‘narrowed’ the passage to refer to speaking in tongues only (cf. 1 Cor 14.9, 13).Footnote 38

Having discussed three examples from ongoing research on bilinguals and 1 Corinthians, one may think that these are rather random and may not provide a conclusive picture. Perhaps that is true, especially for the overly pessimistic. While each example may be unique, it ultimately reflects the main challenges that make the textual history of the New Testament so complex and so fascinating: contamination, coincidence of readings, incompleteness of the textual attestation – and in the case of bilingual manuscripts, the proof of cross-influence with and without further impact on the overall transmission of the New Testament.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to this contribution was conducted as part of the FWO (Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek – Vlaanderen) Odysseus Type I research project ‘1Cor – Text, Transmission and Translation of 1 Corinthians in the First Millennium’ (G0E9821N) and the BICROSS project (‘The Significance of Bilingual Manuscripts for Detecting Cross-Language Interaction in the New Testament Tradition’), which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme (Grant Agreement No. 101043730 – BICROSS – ERC-2021-COG). Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.

Competing interests

The author declares none.