1. Introduction

Gender disparities in the labour market remain a persistent challenge worldwide, as women continue to face structural barriers limiting their economic opportunities. These inequalities are deeply rooted in social and economic systems, as highlighted by Boserup (Reference Boserup1970) and Goldin (Reference Goldin2014, Reference Goldin2021), and are perpetuated by institutional norms and practices restricting women's access to education and employment. Despite improvements in poverty reduction and human development, gender inequalities in employment have either persisted or worsened, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (Goldin, Reference Goldin2014; Fosu, Reference Fosu2015; World Bank, 2017).

Over the past 15 years, Africa's sustained economic growth has not translated into significant progress in gender equity within labour markets (ECA, 2018; ILO, 2019). Women continue to carry a disproportionate burden of unpaid domestic work, performing more than 75 per cent of such tasks, 3.2 times more than men (United Nations, 2020). If current trends persist, women will still spend 9.5 per cent more time and 2.3 additional hours per day on unpaid activities by 2050. This invisible workload constrains women's ability to engage in paid work, as tasks such as water collection, firewood gathering, food preparation, and childcare disproportionately fall on them. Consequently, women's labour force participation (55 per cent) remains well below that of men (78 per cent) (World Economic Forum, 2020).

These inequalities have long been analysed by scholars emphasizing the structural and behavioural factors that perpetuate gender gaps in labour supply (Boserup, Reference Boserup1970; Goldin, Reference Goldin1990). Building on Gazier and Petit (Reference Gazier and Petit2019), women's labour supply can be defined as the number of weekly hours allocated to both paid and unpaid activities. Understanding these dynamics has become even more crucial in the context of climate change, which is reshaping labour market conditions and exacerbating existing gender inequalities. By affecting sectors where women are concentrated, altering household responsibilities, and influencing time allocation between domestic and market work, climate change further constrains women's participation in economic life.

In Burkina Faso, climate change is already a tangible reality, characterized by rising temperatures, declining rainfall, and recurrent extreme events such as floods and droughts (GIZ, 2020). Under the RCP 2.6 and RCP 6.0 scenarios, average temperatures could rise between 1.9°C and 4.2°C by 2080, while rainfall may decrease by up to 7.3 per cent by 2050. Past climate shocks have reduced cereal yields (millet, sorghum, maize) by about 10 per cent (Ochou and Quirion, Reference Ochou and Quirion2022) and farm income by 3.6 per cent (Ouédraogo, Reference Ouédraogo2012). Long-term projections suggest that a 5°C increase could result in a 93 per cent decline in farm income (Ouédraogo, Reference Ouédraogo2012), while reduced rainfall is expected to aggravate water scarcity and economic vulnerability (WaterAid, 2021).

Against this background, this study seeks to answer the following question. What is the economic impact of temperature and precipitation variations on women's labour market participation in Burkina Faso? The objective is to assess the effects of climate change on women's labour supply, considering differences by gender, skill level, and area of residence.

To address this issue, we employ a static computable general equilibrium (CGE) model incorporating climate shocks alongside gender, residence, and qualification differentials (Souratié et al., Reference Souratié, Koinda, Decaluwé and Samandoulougou2019). This framework allows for the simulation of various climate scenarios and their effects on women's employment across sectors and regions. By integrating economic, gender, and environmental dimensions, this study contributes to understanding how climate change amplifies labour market inequalities and provides policy insights for promoting gender-sensitive adaptation strategies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature, Section 3 outlines the methodology, Section 4 presents the results, and Section 5 concludes with policy recommendations.

2. Review of the literature

The analysis of women's labour market participation has followed two main theoretical perspectives. The first highlights socio-economic determinants such as human capital, gender norms, and wage structures as key factors shaping women's participation (Becker, Reference Becker1965; Boserup, Reference Boserup1970; Arrow, Reference Arrow, Ashenfelter and Rees1973; Heckman, Reference Heckman1979; Killingsworth and Heckman, Reference Killingsworth, Heckman, Ashenfelter and Layard1986). The second emphasizes exogenous shocks that alter women's employment opportunities, showing how macroeconomic or structural changes transform gender dynamics (Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Autor and Lyle2004; Goldin, Reference Goldin2014, Reference Goldin2021).

Within this second framework, climate change can be viewed as a large-scale economic shock disrupting labour markets, particularly for women. Building on Acemoglu et al. (Reference Acemoglu, Autor and Lyle2004) and Goldin (Reference Goldin2014, Reference Goldin2021), this study examines how climate variability affects women's economic activities in Burkina Faso. According to Martinez-Fernandez et al. (Reference Martinez-Fernandez, Hinojosa and Miranda2010), climate change influences labour markets through three channels. The first is environmental, as temperature and rainfall fluctuations lead to agricultural decline, resource depletion, and infrastructure degradation, thus reducing food availability and employment. The second operates through regulatory policies, as adaptation and environmental measures modify production structures and labour demand. The third involves social perceptions, where awareness of climate risks shapes labour decisions and household time allocation.

Empirical evidence shows that climate shocks exacerbate gender inequalities by increasing women's unpaid workloads and reducing their paid employment opportunities. Water scarcity forces women to spend more time collecting water (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Hirai and Kim2016; Howard et al., Reference Howard, Calow, Macdonald and Bartram2016), while declining agricultural yields raise household labour burdens, disproportionately affecting women (Cororaton et al., Reference Cororaton, Tiongco, Inocencio, Siriban-Manalang and Lamberte2018; Escalante and Maisonnave, Reference Escalante and Maisonnave2022; Ngepah and Mwiinga, Reference Ngepah and Mwiinga2022). Climate-induced income instability further limits women's financial independence and labour market participation. Empirical studies confirm these effects globally. Antonelli et al. (Reference Antonelli, Coromaldi, Dasgupta, Emmerling and Shayegh2021) find that rising temperatures reduce low-skilled labour in rural Uganda; Abou-Ali et al. (Reference Abou-Ali, Hawash, Ali, Abdelfattah and Hassan2023) show similar negative effects in MENA; Dasgupta et al. (Reference Dasgupta, van Maanen, Gosling, Piontek, Otto and Schleussner2021) and Shayegh and Dasgupta (Reference Shayegh and Dasgupta2024) highlight that global warming particularly harms low-skilled female workers.

Despite this growing literature, few studies explore the indirect effects of climate change on women's labour participation in rural Africa. This study contributes by quantifying these impacts for Burkina Faso.

3. Methodological approach

3.1. Rationale for choosing a computable general equilibrium model

Analysing the impact of climate change on women's economic activities requires a methodological framework that captures both direct and indirect effects. Economists have used various tools to assess the consequences of climate shocks, ranging from econometric and partial equilibrium models to CGE models.

Econometric and partial equilibrium approaches provide useful insights into how temperature and rainfall variations affect agricultural yields and incomes (Ouédraogo, Reference Ouédraogo2012). However, these models remain limited in scope: they often focus on sector-specific relationships and fail to account for the broader economic repercussions of climate shocks. Partial equilibrium models, in particular, overlook the spillover effects that climate-induced changes in agriculture may have on labour markets, household incomes, and intersectoral linkages. Since climate shocks propagate through production and demand chains, affecting the entire economy, a more comprehensive framework is needed.

To address these limitations, researchers increasingly use CGE models, which provide a holistic perspective on economic interactions (Fontana and Wood, Reference Fontana and Wood2000; Montaud et al., Reference Montaud, Pecastaing and Tankari2017; Zidouemba, Reference Zidouemba2017). Unlike partial equilibrium models, CGE models incorporate the interdependence between sectors and agents, allowing for simultaneous analysis of the direct effects of climate shocks on agriculture and their indirect impacts on employment, production structures, and welfare.

This study adopts a CGE framework for Burkina Faso, integrating climate shocks (rising temperatures and declining rainfall) as changes in agricultural productivity. These affect other sectors through economic linkages. By simulating labour market adjustments, the model also examines how existing gender disparities may amplify women's vulnerability to climate change.

3.2. The model description

Our model builds on the static PEP-1-1 modelFootnote 1 (Decaluwé et al., Reference Decaluwé, Lemelin, Robichaud and Maisonnave2013). In line with the standard PEP-1-1 structure, the model represents the government, households, enterprises, and the rest of the world. The government collects taxes on income, production, and trade, and allocates resources to current expenditures and transfers while respecting a budget constraint. Enterprises receive factor incomes (capital), which are either redistributed to households or saved. International trade follows the Armington assumption, with imperfect substitutability between domestic and imported goods, and a constant elasticity of transformation specification for export supply. The balance of payments ensures consistency between foreign savings, the trade balance, and capital flows. These macroeconomic closures (detailed in Section 3.2.4), together with household behaviour and production activities, guarantee a complete and internally consistent general equilibrium framework.

We introduce a time allocation dimension to better capture gender-specific labour dynamics, particularly the balance between paid and unpaid work. This refinement allows for a more detailed analysis of household labour trade-offs, emphasizing the impact of domestic responsibilities on women's economic participation. Labour supply is expressed in hours rather than individuals, offering a granular view of workforce allocation. The model accounts for gender, skill level, and area of residence, reflecting key labour market disparities. Women allocate more time to unpaid domestic work, limiting their market participation (Denton, Reference Denton2002). Lower-skilled individuals engage in climate-sensitive sectors, while rural workers, largely dependent on agriculture, are more vulnerable to climatic fluctuations. Household production is modelled as a labour-intensive process, relying solely on household members’ working hours, with male and female labour treated as imperfect substitutes. We do not disaggregate capital and intermediate inputs by gender because (i) no reliable input/output data exist on gendered use of intermediates, (ii) doing so would substantially increase parameterization without empirical support, and (iii) unlike labour, which in the Burkinabe context is clearly sex-differentiated, capital and inputs are generally pooled at the household level. In agriculture, women may cultivate small plots, but ownership typically remains with the male household head. In other sectors as well, women mainly use household capital made available to them rather than distinctly female-owned assets. Capturing such distinctions would therefore require strong, unverifiable assumptions. While this simplification excludes potential differences linked to “female-controlled capital” or gender-specific input mixes, the CGE model retains its core strengths: economy-wide price-mediated linkages, sectoral reallocation, and full household income–expenditure feedback with gender-differentiated labour markets.

Households maximize a Stone-Geary utility function. This functional form accounts for subsistence consumption levels, which are particularly relevant in low-income economies such as Burkina Faso, where a significant portion of household consumption is dedicated to basic necessities (e.g., food, water, and housing). Unlike the Cobb-Douglas function, the Stone-Geary utility function allows for income-dependent consumption patterns, reflecting how climate shocks (e.g., agricultural declines) may force households to prioritize essential goods over discretionary spending.

3.2.1. The structure of the production function

To assess the differentiation of production factors by gender, the standard production function has been modified (Figure A1 in the online appendix). The production process follows a four-level structure, as proposed by Decaluwé et al. (Reference Decaluwé, Lemelin, Robichaud and Maisonnave2013), Zidouemba et al. (Reference Zidouemba, Kinda, Nikiema and Hien2018), and Souratié et al. (Reference Souratié, Koinda, Decaluwé and Samandoulougou2019). At the highest level, total production in each sector  $\left( {XS{T_j}} \right)\,$is defined as a fixed-share combination of total value added

$\left( {XS{T_j}} \right)\,$is defined as a fixed-share combination of total value added  $\left( {V{A_j}} \right)\,$and intermediate consumption

$\left( {V{A_j}} \right)\,$and intermediate consumption  $\left( {C{I_j}} \right)$. The relationship between these two components follows a Leontief production function, assuming strict complementarity and no substitution between inputs:

$\left( {C{I_j}} \right)$. The relationship between these two components follows a Leontief production function, assuming strict complementarity and no substitution between inputs:

where ![]() ${v_j}$ and

${v_j}$ and ![]() $i{o_j}$ represent the Leontief coefficients for value added and intermediate consumption, respectively. At the next level, total value added (

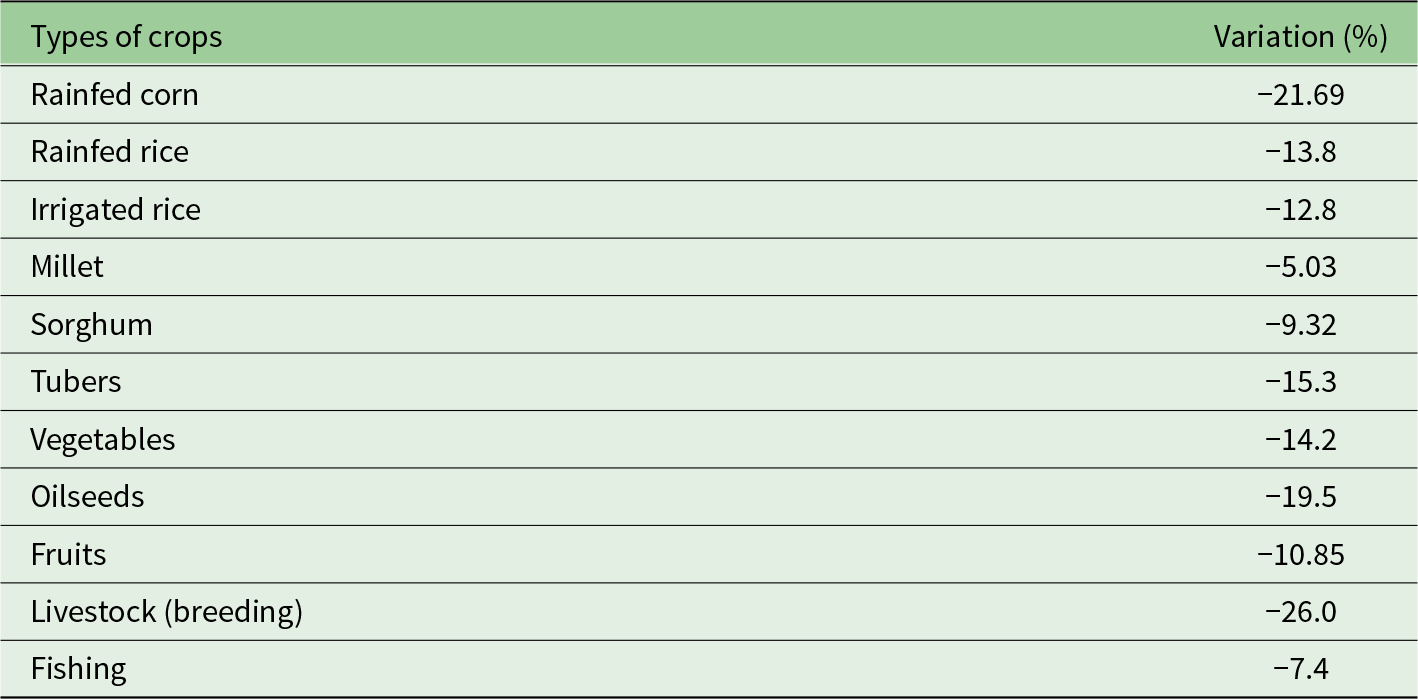

$i{o_j}$ represent the Leontief coefficients for value added and intermediate consumption, respectively. At the next level, total value added (![]() $V{A_j}$) is a constant elasticity of substitution (CES) function of composite capital (

$V{A_j}$) is a constant elasticity of substitution (CES) function of composite capital (![]() $KD{C_j}$) and composite labour (

$KD{C_j}$) and composite labour (![]() $LD{C_j}$). This structure assumes imperfect substitutability between the two production factors,

$LD{C_j}$). This structure assumes imperfect substitutability between the two production factors,

\begin{equation}V{A_j} = B_j^{VA}{\left[ {\alpha _j^{VA}LDC_j^{ - \sigma _j^{VA}} + \left( {1 - \alpha _j^{VA}} \right)KDC_j^{ - \sigma _j^{VA}}} \right]^{ - 1/\sigma _j^{VA}}}.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}V{A_j} = B_j^{VA}{\left[ {\alpha _j^{VA}LDC_j^{ - \sigma _j^{VA}} + \left( {1 - \alpha _j^{VA}} \right)KDC_j^{ - \sigma _j^{VA}}} \right]^{ - 1/\sigma _j^{VA}}}.\end{equation}From this equation, the demand for composite labour and composite capital can be derived as

\begin{equation}LD{C_j} = {\left[ {\frac{{\alpha _j^{VA}R{C_j}}}{{\left( {1 - \alpha _j^{VA}} \right)W{C_j}}}} \right]^{\sigma _j^{VA}}}KD{C_j},\end{equation}

\begin{equation}LD{C_j} = {\left[ {\frac{{\alpha _j^{VA}R{C_j}}}{{\left( {1 - \alpha _j^{VA}} \right)W{C_j}}}} \right]^{\sigma _j^{VA}}}KD{C_j},\end{equation} with  $\beta _j^{VA}$ representing the value-added distribution parameter which captures the sensitivity of agricultural sectors to climate change. Since climate sensitivity varies across crops, this parameter is crop-specific.

$\beta _j^{VA}$ representing the value-added distribution parameter which captures the sensitivity of agricultural sectors to climate change. Since climate sensitivity varies across crops, this parameter is crop-specific.  $B_j^{VA}$ denotes the productivity parameter, while

$B_j^{VA}$ denotes the productivity parameter, while  $\rho _j^{VA}$ is the elasticity parameter governing factor substitution.

$\rho _j^{VA}$ is the elasticity parameter governing factor substitution.

Crucially,  $B_j^{VA}$ is influenced by climate change. Climate shocks alter total factor productivity, which is modelled as a function of an annual depreciation rate dictated by variations in rainfall and temperature

$B_j^{VA}$ is influenced by climate change. Climate shocks alter total factor productivity, which is modelled as a function of an annual depreciation rate dictated by variations in rainfall and temperature ![]() $(climateshoc{k_j})$. The productivity parameter becomes

$(climateshoc{k_j})$. The productivity parameter becomes

\begin{equation}B_j^{VA} = \,B_j^{VA}\,\left( {1 - climateshoc{k_j}} \right).\end{equation}

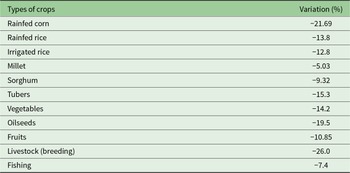

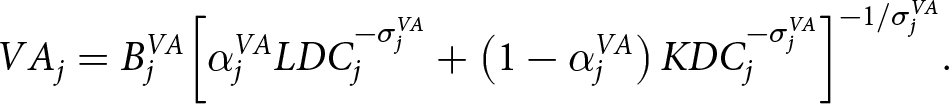

\begin{equation}B_j^{VA} = \,B_j^{VA}\,\left( {1 - climateshoc{k_j}} \right).\end{equation} The variable ![]() $climateshoc{k_j}$ represents the expected impact of climate change on sectoral productivity and is expressed as a percentage change in yields. Its values are calibrated from empirical studies (Zidouemba, Reference Zidouemba2017; World Bank, 2020; Sawadogo and Fofana, Reference Sawadogo and Fofana2021) and are reported in Table 1. The shocks vary by activity, ranging from −5.03 per cent for millet to −26 per cent for livestock, thereby capturing the heterogeneity of climate impacts across sectors. These percentage changes are applied in the model as multiplicative shocks to sectoral value-added functions. This specification allows us to simulate both moderate and extreme weather events (e.g., droughts, heatwaves, or flooding) depending on their intensity, while ensuring that the parameter remains grounded in observed and projected impacts for Burkina Faso.

$climateshoc{k_j}$ represents the expected impact of climate change on sectoral productivity and is expressed as a percentage change in yields. Its values are calibrated from empirical studies (Zidouemba, Reference Zidouemba2017; World Bank, 2020; Sawadogo and Fofana, Reference Sawadogo and Fofana2021) and are reported in Table 1. The shocks vary by activity, ranging from −5.03 per cent for millet to −26 per cent for livestock, thereby capturing the heterogeneity of climate impacts across sectors. These percentage changes are applied in the model as multiplicative shocks to sectoral value-added functions. This specification allows us to simulate both moderate and extreme weather events (e.g., droughts, heatwaves, or flooding) depending on their intensity, while ensuring that the parameter remains grounded in observed and projected impacts for Burkina Faso.

Table 1. Variation in agricultural yields (%)

Source: World Bank (2020); Zidouemba (Reference Zidouemba2017) and Sawadogo and Fofana (Reference Sawadogo and Fofana2021).

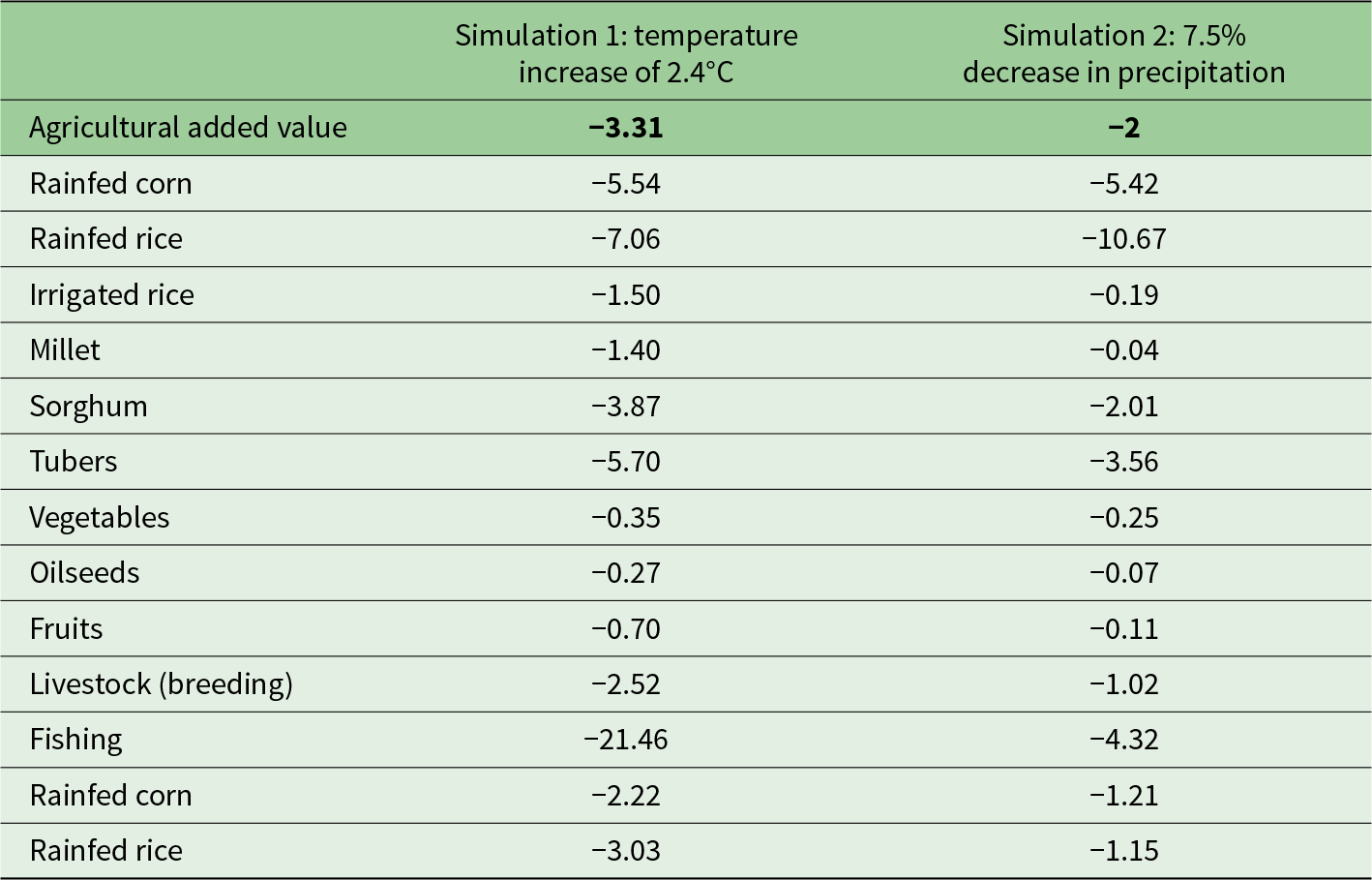

At the third level, the composite labour demand ![]() $(LD{C_j})$ is further disaggregated by skill level, distinguishing between skilled

$(LD{C_j})$ is further disaggregated by skill level, distinguishing between skilled  $\left( {L{Q_j}} \right)$ and unskilled labour

$\left( {L{Q_j}} \right)$ and unskilled labour  $\left( {LN{Q_j}} \right)$ using a CES function. The mathematical form is as follows:

$\left( {LN{Q_j}} \right)$ using a CES function. The mathematical form is as follows:

\begin{equation}LD{C_j} = B_j^{LDC}{\left[ {\beta _j^{LDC}LQ_j^{ - \rho _j^{LDC}} + \left( {1 - \beta _j^{LDC}} \right)LNQ_j^{ - \rho _j^{LDC}}} \right]^{ - 1/\rho _j^{LDC}}}.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}LD{C_j} = B_j^{LDC}{\left[ {\beta _j^{LDC}LQ_j^{ - \rho _j^{LDC}} + \left( {1 - \beta _j^{LDC}} \right)LNQ_j^{ - \rho _j^{LDC}}} \right]^{ - 1/\rho _j^{LDC}}}.\end{equation}From this equation, the demand function for skilled labour is given by

\begin{equation}L{Q_j} = { }{\left[ {\frac{{\beta _j^{LDC}}}{{\left( {1 - \beta _j^{LDC}} \right)}}\frac{{WN{Q_J}}}{{W{Q_J}}}} \right]^{\sigma _j^{LDC}}}LN{Q_j}.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}L{Q_j} = { }{\left[ {\frac{{\beta _j^{LDC}}}{{\left( {1 - \beta _j^{LDC}} \right)}}\frac{{WN{Q_J}}}{{W{Q_J}}}} \right]^{\sigma _j^{LDC}}}LN{Q_j}.\end{equation}At the final level, each skill category is further disaggregated by gender, distinguishing between male and female workers. The labour functions for skilled and unskilled male and female workers are specified as shown below.

For skilled labour:

\begin{equation}L{Q_j} = { }B_j^{LQ}{\left[ {\beta _j^{LQ}LHQ_j^{ - \rho _j^{LQ}} + \left( {1 - \beta _j^{LQ}} \right)LFQ_j^{ - \rho _j^{LQ}}} \right]^{{{ - 1} \!\mathord{\left/

{\vphantom {{ - 1} {\rho _j^{LQ}}}}\right.}

\!{\rho _j^{LQ}}}}},\end{equation}

\begin{equation}L{Q_j} = { }B_j^{LQ}{\left[ {\beta _j^{LQ}LHQ_j^{ - \rho _j^{LQ}} + \left( {1 - \beta _j^{LQ}} \right)LFQ_j^{ - \rho _j^{LQ}}} \right]^{{{ - 1} \!\mathord{\left/

{\vphantom {{ - 1} {\rho _j^{LQ}}}}\right.}

\!{\rho _j^{LQ}}}}},\end{equation} \begin{equation}LH{Q_j} = {\left[ {\frac{{\beta _j^{LQ}}}{{\left( {1 - \beta _j^{LQ}} \right)}}\frac{{WF{Q_J}}}{{WH{Q_J}}}} \right]^{\sigma _j^{LQ}}}LF{Q_j},\end{equation}

\begin{equation}LH{Q_j} = {\left[ {\frac{{\beta _j^{LQ}}}{{\left( {1 - \beta _j^{LQ}} \right)}}\frac{{WF{Q_J}}}{{WH{Q_J}}}} \right]^{\sigma _j^{LQ}}}LF{Q_j},\end{equation} \begin{equation}LN{Q_j} = { }B_j^{LNQ}{\left[ {\beta _j^{LNQ}LHNQ_j^{ - \rho _j^{LNQ}} + \left( {1 - \beta _j^{LNQ}} \right)LFNQ_j^{ - \rho _j^{LNQ}}} \right]^{{{ - 1} \!\mathord{\left/

{\vphantom {{ - 1} {\rho _j^{LNQ}}}}\right.}

\!{\rho _j^{LNQ}}}}}\,,\end{equation}

\begin{equation}LN{Q_j} = { }B_j^{LNQ}{\left[ {\beta _j^{LNQ}LHNQ_j^{ - \rho _j^{LNQ}} + \left( {1 - \beta _j^{LNQ}} \right)LFNQ_j^{ - \rho _j^{LNQ}}} \right]^{{{ - 1} \!\mathord{\left/

{\vphantom {{ - 1} {\rho _j^{LNQ}}}}\right.}

\!{\rho _j^{LNQ}}}}}\,,\end{equation} \begin{equation}LHN{Q_j} = {\left[ {\frac{{\beta _j^{LNQ}}}{{\left( {1 - \beta _j^{LNQ}} \right)}}\frac{{WFN{Q_J}}}{{WHN{Q_J}}}} \right]^{\sigma _j^{LNQ}}}LFN{Q_j}.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}LHN{Q_j} = {\left[ {\frac{{\beta _j^{LNQ}}}{{\left( {1 - \beta _j^{LNQ}} \right)}}\frac{{WFN{Q_J}}}{{WHN{Q_J}}}} \right]^{\sigma _j^{LNQ}}}LFN{Q_j}.\end{equation} uations (8) and (10) define the CES aggregation of male and female labour within each skill category: ![]() $LHQ$ and

$LHQ$ and ![]() $LHNQ$ represent male skilled and unskilled labour, while

$LHNQ$ represent male skilled and unskilled labour, while ![]() $LFQ$ and

$LFQ$ and ![]() $LFNQ$ represent female skilled and unskilled labour, respectively. Equations (9) and (11) correspond to the first-order conditions that determine the demand for male labour as a function of female labour and relative wages. This specification explicitly captures gender differences in labour markets by treating male and female workers as imperfect substitutes within each skill category.

$LFNQ$ represent female skilled and unskilled labour, respectively. Equations (9) and (11) correspond to the first-order conditions that determine the demand for male labour as a function of female labour and relative wages. This specification explicitly captures gender differences in labour markets by treating male and female workers as imperfect substitutes within each skill category.

3.2.2. Incorporating non-market production into the model

To account for the impacts of climate change on the well-being of men and women, we integrate non-market production activities into the model, drawing inspiration from Cockburn et al. (Reference Cockburn, Maisonnave, Robichaud and Tiberti2016). A key distinguishing feature of our model, compared to standard models, is the explicit incorporation of domestic production.

In this framework, each active household member has a finite number of hours, which they allocate between domestic production (LZ) and market production (LS). The decision-making process involves an arbitrage between market and domestic work. Time allocated to the non-market sphere generates home-produced goods, which are entirely self-consumed by the household and do not enter market transactions.

The labour supply is determined by four key assumptions that shape the way individuals allocate their time between different activities. First, we assume that time allocation is perfectly separable between market production and domestic production. This means that individuals cannot engage in multiple activities simultaneously. As a result, labour supply is endogenously determined, as individuals make choices based on the trade-offs between these competing activities. Second, domestic production relies exclusively on household labour and does not require intermediate inputs or capital. This assumption reflects the reality that domestic tasks, such as childcare, cooking, and cleaning, are primarily labour-intensive and are carried out within the household without external resources. Third, male and female domestic labour are imperfect substitutes, meaning that they do not contribute equally to household production and cannot be easily interchanged. The Cockburn et al. combination is modeled using a CES function, where time allocation is determined through a constrained maximization process, taking into account elasticity of substitution and opportunity costs.

Finally, we consider that labour supply varies not only by gender but also by skill level and place of residence. Empirical evidence supports this approach. Households with lower skill levels are generally more dependent on economic activities that are highly sensitive to climate shocks, making their labour supply more volatile and vulnerable to environmental changes. At the same time, rural households are primarily engaged in agriculture, a sector directly exposed to climate change, making their labour supply less stable than that of urban households.

Based on these assumptions, total domestic production (![]() ${Z_h}$) is expressed as the sum of male (

${Z_h}$) is expressed as the sum of male (![]() $LZ{H_h}$) and female (

$LZ{H_h}$) and female (![]() $LZ{F_h}$) domestic labour, capturing the full extent of household labour contributions. That is,

$LZ{F_h}$) domestic labour, capturing the full extent of household labour contributions. That is,

Using a CES specification, domestic production is modelled as

\begin{equation}{Z_h} = { }B_h^{zlab}{\left[ {\beta _h^{zlab}LZF_h^{ - \rho _h^{zlab}} + \left( {1 - \beta _h^{zlab}} \right)LZH_h^{ - \rho _h^{zlab}}} \right]^{ - \frac{1}{{\rho _h^{zlab}}}}}.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{Z_h} = { }B_h^{zlab}{\left[ {\beta _h^{zlab}LZF_h^{ - \rho _h^{zlab}} + \left( {1 - \beta _h^{zlab}} \right)LZH_h^{ - \rho _h^{zlab}}} \right]^{ - \frac{1}{{\rho _h^{zlab}}}}}.\end{equation}From this equation, the demand for female labour in domestic production is given by

\begin{equation}LZ{F_h} = {\left[ {\frac{{\beta _h^{zlab}}}{{\left( {1 - \beta _h^{zlab}} \right)}}\frac{{WZ{H_h}}}{{WZ{F_h}}}} \right]^{\sigma _h^{zlab}}}LZ{H_h}.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}LZ{F_h} = {\left[ {\frac{{\beta _h^{zlab}}}{{\left( {1 - \beta _h^{zlab}} \right)}}\frac{{WZ{H_h}}}{{WZ{F_h}}}} \right]^{\sigma _h^{zlab}}}LZ{H_h}.\end{equation} Further disaggregation of female domestic labour (![]() $LZ{F_h}$) into skilled (

$LZ{F_h}$) into skilled (![]() $LZF{Q_h}$) and unskilled (

$LZF{Q_h}$) and unskilled (![]() $LZFN{Q_h})$ labour follows a similar CES formulation:

$LZFN{Q_h})$ labour follows a similar CES formulation:

\begin{equation}LZ{F_h} = { }B_h^{zlabf}{\left[ {\beta _h^{zlabf}LZFQ_h^{ - \rho _h^{zlabf}} + \left( {1 - \beta _h^{zlabf}} \right)LZFNQ_h^{ - \rho _h^{zlabf}}} \right]^{{{ - 1} \!\mathord{\left/

{\vphantom {{ - 1} {\rho _h^{zlabf}}}}\right.}

\!{\rho _h^{zlabf}}}}},\end{equation}

\begin{equation}LZ{F_h} = { }B_h^{zlabf}{\left[ {\beta _h^{zlabf}LZFQ_h^{ - \rho _h^{zlabf}} + \left( {1 - \beta _h^{zlabf}} \right)LZFNQ_h^{ - \rho _h^{zlabf}}} \right]^{{{ - 1} \!\mathord{\left/

{\vphantom {{ - 1} {\rho _h^{zlabf}}}}\right.}

\!{\rho _h^{zlabf}}}}},\end{equation} \begin{equation}LZF{Q_h} = {\left[ {\frac{{\beta _h^{zlabf}}}{{\left( {1 - \beta _h^{zlabf}} \right)}}\frac{{WZFN{Q_h}}}{{WZF{Q_h}}}} \right]^{\sigma _h^{zlabf}}}LZFN{Q_h}.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}LZF{Q_h} = {\left[ {\frac{{\beta _h^{zlabf}}}{{\left( {1 - \beta _h^{zlabf}} \right)}}\frac{{WZFN{Q_h}}}{{WZF{Q_h}}}} \right]^{\sigma _h^{zlabf}}}LZFN{Q_h}.\end{equation} Similarly, male domestic labour (![]() $LZ{H_h}$) is divided into skilled (

$LZ{H_h}$) is divided into skilled (![]() $LZH{Q_h}$) and unskilled (

$LZH{Q_h}$) and unskilled (![]() $LZHN{Q_h}$) labour:

$LZHN{Q_h}$) labour:

\begin{equation}LZ{H_h} = { }B_h^{zlabh}{\left[ {\beta _h^{zlabh}LZHQ_h^{ - \rho _h^{zlabh}} + \left( {1 - \beta _h^{zlabh}} \right)LZHNQ_h^{ - \rho _h^{zlabh}}} \right]^{{{ - 1} \!\mathord{\left/

{\vphantom {{ - 1} {\rho _h^{zlabh}}}}\right.}

\!{\rho _h^{zlabh}}}}},\end{equation}

\begin{equation}LZ{H_h} = { }B_h^{zlabh}{\left[ {\beta _h^{zlabh}LZHQ_h^{ - \rho _h^{zlabh}} + \left( {1 - \beta _h^{zlabh}} \right)LZHNQ_h^{ - \rho _h^{zlabh}}} \right]^{{{ - 1} \!\mathord{\left/

{\vphantom {{ - 1} {\rho _h^{zlabh}}}}\right.}

\!{\rho _h^{zlabh}}}}},\end{equation} \begin{equation}LZH{Q_h} = {\left[ {\frac{{\beta _h^{zlabh}}}{{\left( {1 - \beta _h^{zlabh}} \right)}}\frac{{WZHN{Q_h}}}{{WZH{Q_h}}}} \right]^{\sigma _h^{zlabh}}}LZHN{Q_h}.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}LZH{Q_h} = {\left[ {\frac{{\beta _h^{zlabh}}}{{\left( {1 - \beta _h^{zlabh}} \right)}}\frac{{WZHN{Q_h}}}{{WZH{Q_h}}}} \right]^{\sigma _h^{zlabh}}}LZHN{Q_h}.\end{equation}3.2.3. Implicit valuation of domestic production

The implicit price of domestic production ( $P_h^{hom}$) is determined by the weighted average wages of male and female domestic labour,

$P_h^{hom}$) is determined by the weighted average wages of male and female domestic labour,

\begin{equation}P_h^{hom} = \frac{{WZ{F_h}LZ{F_h} + WZ{H_h}LZ{H_h}}}{{{Z_h}}}.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}P_h^{hom} = \frac{{WZ{F_h}LZ{F_h} + WZ{H_h}LZ{H_h}}}{{{Z_h}}}.\end{equation}Similarly, the average wage rates for female and male domestic labour are derived as

\begin{equation}WZ{F_h} = \frac{{WZFN{Q_h}LZFN{Q_h} + WZF{Q_h}LZF{Q_h}}}{{LZ{F_h}}},\end{equation}

\begin{equation}WZ{F_h} = \frac{{WZFN{Q_h}LZFN{Q_h} + WZF{Q_h}LZF{Q_h}}}{{LZ{F_h}}},\end{equation} \begin{equation}WZ{H_h} = \frac{{WZHN{Q_h}LZHN{Q_h} + WZH{Q_h}LZH{Q_h}}}{{LZ{H_h}}}\,.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}WZ{H_h} = \frac{{WZHN{Q_h}LZHN{Q_h} + WZH{Q_h}LZH{Q_h}}}{{LZ{H_h}}}\,.\end{equation} On the demand side, we assume that all domestic production (![]() ${Z_h}$) is entirely self-consumed by the household:

${Z_h}$) is entirely self-consumed by the household:

The value of domestic production (![]() ${Z_h}$) is determined by its opportunity cost. This is the expected rate of remuneration on the labour market in the non-domestic sphere of the economy by the various active members of the household who implement it:

${Z_h}$) is determined by its opportunity cost. This is the expected rate of remuneration on the labour market in the non-domestic sphere of the economy by the various active members of the household who implement it:

\begin{equation}P{Z_h}.{Z_h} = \mathop \sum \limits_l {W^l}.LZ_h^l.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}P{Z_h}.{Z_h} = \mathop \sum \limits_l {W^l}.LZ_h^l.\end{equation}3.2.4. The model closures and implementation

To ensure macroeconomic consistency, the model follows closure rules. First, it defines the nominal exchange rate as the numeraire, reflecting the reality that Burkina Faso, as a small open economy, has no influence over international prices. First, the model assumes a fixed current account balance, meaning the country cannot engage in unlimited borrowing from international financial markets. Second, the government account closure is based on the assumption that public expenditures are exogenous and public savings adjust to variations in government revenues. In addition to the government and external balance closures, we specify assumptions for the labour and goods markets. Third, the labour market is modelled under perfect competition, with fully flexible wages ensuring the absence of involuntary unemployment in equilibrium. Labour supply is determined endogenously, as households allocate their time between domestic and market activities in response to wage signals and preferences. Finally, likewise, goods markets including agriculture are assumed to clear through flexible prices that adjust to balance supply and demand.

The model is implemented in GAMS. The system of equations is solved using the constrained nonlinear system solver. The model is calibrated with the social accounting matrix (SAM) of Burkina Faso, ensuring consistency with the country's economic structure. Given its static nature, it does not incorporate historical validation of the business as usual scenario. However, standard equilibrium properties, including Walras’ Law, are explicitly verified by ensuring that the sum of excess demands across markets, particularly in the last market (corn market), is zero in all simulations.

3.3. Data source and descriptive statistics

The model is calibrated using a gender disaggregated SAM developed by Souratié et al. (Reference Souratié, Koinda, Decaluwé and Samandoulougou2019) for Burkina Faso. This matrix maps economic interactions across four household categories, businesses, the government, and the external sector, covering 132 goods and services, including 47 agricultural products, and 74 activity accounts, 29 of which are agricultural. To align with research objectives, the SAM is aggregated into 29 economic sectors, including 12 agricultural sectors and 29 product categories. Labour categories remain disaggregated by gender and skill level, but household groups are consolidated into rural and urban classifications. Labour substitution elasticities between men and women are sourced from the existing literature (Denton, Reference Denton2002).

We also rely on two key databases (Table A1 in the online appendix). The first dataset, drawn from the OECD time budget database (2018), provides information on time allocated to domestic and paid work. Collected in 2018 by the OECD, this data was compiled to assess the hidden contributions to GDP that are often overlooked in conventional economic measurements. The second dataset comes from the Harmonized Survey on Household Living Conditions (EHCVM), conducted in 2018 by the National Institute of Statistics and Demography (INSD). The objective of this survey was to evaluate the current living conditions of the Burkinabe population, particularly in response to global changes, and to identify key socio-economic challenges. To assess the impact of climate change on women's labour supply in Burkina Faso, these datasets are disaggregated by gender (male and female), skill level (skilled and unskilled), and place of residence (rural and urban). An analysis of this data (Figure A2 in the online appendix) reveals that women spend an average of 6 hours and 15 minutes per day on domestic work. Rural women dedicate 6 hours and 31 minutes daily, slightly more than their urban counterparts, who spend an average of 6 hours per day on unpaid household tasks. Furthermore, unskilled women devote 5 hours and 44 minutes to domestic work, compared to 4 hours and 24 minutes for skilled women. Figure A2 illustrates the distribution of time spent by men and women on unpaid domestic labour, highlighting the persistent gender gap in time allocation.

The valuation of the average time spent by women on domestic activities yields the results presented in Figure A3 (online appendix). Analysing this data reveals a significant gender disparity in the monetary value of domestic production, particularly in rural areas. Women's domestic labour is estimated at 3,010,217 FCFA (Franc of the African Financial Community), compared to 303,731 FCFA for men, highlighting the disproportionate burden of unpaid work carried by women.

When broken down by skill level, the differences remain pronounced. Among unskilled individuals, the estimated value of domestic work reaches 2,924,347 FCFA for women, compared to 311,067 FCFA for men. For skilled individuals, the valuation stands at 2,127,665 FCFA for women and 190,749 FCFA for men. Figure A3 illustrates the significant economic contribution of women's unpaid labour, particularly among rural and unskilled populations, and underscore the gendered nature of time allocation in domestic activities.

3.4. Simulation scenarios

The objective of this research is to analyse the impact of climate shocks on women's economic activities in Burkina Faso. To achieve this, two distinct climate shocks are examined separately: an increase in temperatures, leading to a decline in agricultural yields, and a decrease in precipitation, reducing the availability of water resources for consumption.

For the first climate shock, the associated climate scenario is based on the new generation of five climate projections selected by IPCC (Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani, Connors, Péan, Berger, Caud, Chen, Goldfarb, Gomis, Huang, Leitzell, Lonnoy, Matthews, Maycock, Waterfield, Yelekçi, R and Zhou2022). Specifically, this study relates to the SSP5-8.5 scenario, which the (IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani, Connors, Péan, Berger, Caud, Chen, Goldfarb, Gomis, Huang, Leitzell, Lonnoy, Matthews, Maycock, Waterfield, Yelekçi, R and Zhou2022) considers a likely trajectory by 2050. This scenario projects a temperature increase of 2.4°C, reflecting the failure of mitigation policies and the continuation of current trends in primary energy consumption and the energy mix. Given its suitability for medium-term climate impact studies, this SSP5-8.5 scenario forms the basis for the first simulation (Scenario 1) in this research.

In the broader literature, there is a consensus that extreme climate events, particularly rising temperatures, negatively affect the agricultural sector. However, the mechanisms through which these shocks impact agriculture remain debated. Some studies (Zidouemba, Reference Zidouemba2017; Jägermeyr et al., Reference Jägermeyr, Müller, Ruane, Elliott, Balkovic, Castillo, Faye, Foster, Folberth, Franke and Fuchs2021) suggest that extreme climate events primarily affect agriculture by reducing crop yields. Others (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Feng, Oppenheimer and Pytlikova2016; Dhifaoui et al., Reference Dhifaoui, Khalfaoui, Jabeur and Abedin2023) argue that the main transmission channel is through rising agricultural prices, which indirectly affect food security and labour dynamics.

In the specific case of Burkina Faso, empirical studies predict a significant decline in agricultural yields by 2050 (Zidouemba, Reference Zidouemba2017; World Bank, 2020). Building on this literature, this research aims to assess how variations in agricultural yields influence the labour market, with a particular focus on gendered labour supply responses and sectoral employment shifts.

In addition to rising temperatures, declining precipitation represents another major climate shock that threatens Burkina Faso's economy, particularly by affecting water availability and its cascading effects on various sectors. According to the WaterAid (2021) report on climate change and water security, the country is expected to experience a 3.4 per cent reduction in rainfall by 2025 and a 7.5 per cent decline by 2050, depending on the scenario considered. This reduction in precipitation is projected to lead to a significant decrease in water resources across all major river basins, further straining access to this essential resource. Compared to the reference period of 1961–1990, water availability is expected to decline by 68.9 per cent in the Comoé Basin, 73 per cent in the Mouhoun Basin, 29.9 per cent in the Nakambé Basin, and 41.4 per cent in the Niger Basin by 2050. These figures indicate that Burkina Faso could face severe water shortages, with serious implications for agriculture, household consumption, and overall economic stability (Zidouemba, Reference Zidouemba2017).

Given these alarming trends, this research adopts the pessimistic scenario from the WaterAid report, which assumes a 7.5 per cent reduction in precipitation by 2050. To provide a comprehensive assessment of climate change's impact on women's labour supply, this scenario will be simulated alongside the decline in agricultural yields. This combined approach allows for a better understanding of how these climate shocks interact and influence labour dynamics, particularly in sectors where women are heavily represented. Figures A4 and A5 and Table A2 in the online appendix show the descriptive statistics of extreme weather events in Burkina Faso.

4. Results and discussion

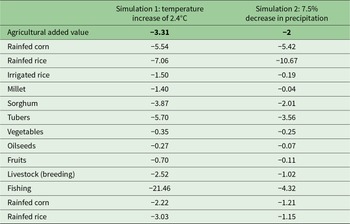

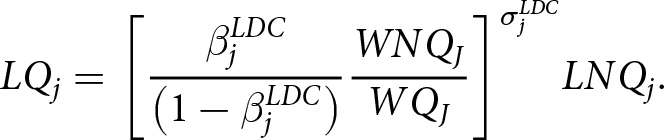

4.1. Impact on agricultural added value

The results presented in Table 2 indicate that extreme climatic events, specifically temperature variations (Scenario 1) and precipitation variations (Scenario 2), have a negative impact on agricultural productivity in Burkina Faso. However, the effects are not uniform across all crops, as different crops exhibit varying degrees of sensitivity to climate change. Those that are more climate-sensitive experience a more pronounced decline in value added, highlighting the uneven vulnerability of different agricultural sectors. The decline in agricultural yields due to extreme climatic events translates into an overall reduction in agricultural value added, further weakening the sector's contribution to the economy. Under Scenario 1, where temperatures rise by 2.4°C, agricultural value added declines by 3.31 per cent, which translates into a loss of approximately 69 billion FCFA. In Scenario 2, where precipitation decreases by 7.5 per cent, the reduction in agricultural value added is 2 per cent, equivalent to 41 billion FCFA. These substantial economic losses highlight the vulnerability of the agricultural sector to climate shocks, reinforcing the need for climate adaptation strategies to mitigate these negative effects and safeguard rural livelihoods. These findings align with empirical evidence from Sawadogo and Fofana (Reference Sawadogo and Fofana2021) and (Awiti, Reference Awiti2022), reinforcing the established understanding that extreme climate events negatively affect agricultural productivity.

Table 2. Impact of climate change on agricultural added value

A similar trend is observed for food crop yields, which also decline in response to both temperature and precipitation shocks. However, in both scenarios, the impact is more severe on rainfed crop production, reflecting the sector's higher dependence on climate conditions. Cereal yields, in particular, experience notable declines, dropping by 5.54 per cent in Scenario 1 (temperature variations) and 5.42 per cent in Scenario 2 (precipitation variations). This increased vulnerability can be attributed to the traditional nature of agricultural practices in Burkina Faso, where most farming activities are carried out extensively and manually, with limited soil fertilization. As Combary and Savadogo (Reference Combary and Savadogo2014) highlight, these small family farms – typically less than 5 hectares and primarily managed by women – have low production efficiency, making them highly susceptible to climate shocks.

In Burkina Faso, cereal crops such as millet, sorghum, and corn form the staple diet of most households, which explains why many families prioritize their cultivation to ensure food security. However, given the physical intensity of agricultural labour, which is performed outdoors under direct sunlight, an increase in temperatures (as predicted in Scenario 1) could pose significant occupational health risks. Extreme heat conditions are likely to affect workers’ physical capacities, reduce their endurance, and lead to a loss of working hours, ultimately lowering household productivity (World Bank, 2020).

These findings reinforce the idea that climate change acts as a threat multiplier for agricultural activities in Burkina Faso, exacerbating existing challenges and placing additional strain on vulnerable farming communities. The results of this study are consistent with the work of Ochou and Quirion (Reference Ochou and Quirion2022) and Ouédraogo (Reference Ouédraogo2012), who similarly find that climate change negatively affects agricultural output. However, these conclusions contradict the findings of Mendelsohn et al. (Reference Mendelsohn, Nordhaus and Shaw1994), who argue that rising global temperatures could enhance agricultural productivity in some regions by extending growing seasons and increasing CO2 concentrations. While such effects may hold in certain temperate zones, they appear less applicable to Burkina Faso's predominantly rainfed and small-scale agricultural system, where temperature increases and water shortages are more likely to reduce yields than to create growth opportunities.

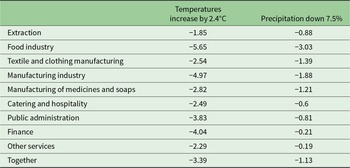

4.2. Impact on non-agricultural sectors

The negative impact of climate change on agricultural value added extends beyond the agricultural sector, triggering a chain reaction that spills over into non-agricultural sectors through supply and demand mechanisms, in accordance with Walras’ law. Given the interconnections between economic sectors, captured by the Leontief coefficient, variations in agricultural production due to temperature and precipitation changes inevitably affect the demand for goods and services in other industries.

Sectors that are closely linked to agriculture – particularly the agri-food industry, manufacturing, catering and hospitality, textiles, clothing, medicine, and soap production – experience sharp declines in value added, as shown in Table 3. This downturn can be attributed to two key transmission mechanisms. First, the decline in agricultural value added leads to a reduction in intermediate demand, as downstream industries rely heavily on raw materials from agriculture. Second, climate-induced shocks cause an increase in the price of agricultural products, making inputs more expensive for sectors that depend on them. These combined effects weaken industrial activity, slow down production, and disrupt supply chains.

Table 3. Impact of climate change on the value added of non-agricultural sectors

These findings align with previous research, particularly the work of Sawadogo and Fofana (Reference Sawadogo and Fofana2021) and Escalante and Maisonnave (Reference Escalante and Maisonnave2022), which also highlight the indirect economic consequences of climate change on industrial and service sectors. The results observed in this study stem from the transmission mechanisms embedded in our CGE model, which adheres to Walrasian principles. By capturing the general equilibrium effects of climate change, the model illustrates how shocks in one sector can reverberate across the entire economy, reshaping production structures and influencing market equilibrium conditions.

Beyond their involvement in agricultural and non-agricultural sectors, women are highly engaged in domestic activities, which constitute a significant part of their daily workload. The data reveal that, on average, women dedicate more than six hours per day to unpaid domestic labour (Figure A2). Given the central role of domestic work in shaping women's overall labour participation, it is essential to examine how climate change influences their ability to engage in both market and non-market activities. The following section provides a detailed analysis of the impact of climate change on women's labour supply, exploring the ways in which temperature and precipitation variations affect their economic opportunities and time allocation between domestic and paid work.

4.3. Impact of climate change on the labour market

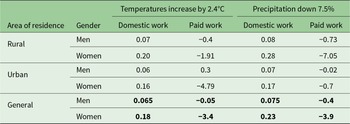

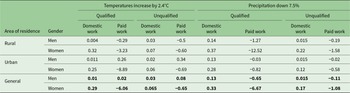

The results presented in Table 4 highlight the adverse effects of climate change on women's economic and domestic activities. The decline in agricultural value added due to temperature increases (Scenario 1) and reduced precipitation (Scenario 2) not only affects agriculture but also extends to non-agricultural sectors, significantly altering women's labour dynamics.

Table 4. Impact of climate change on labour supply depending on the area of residence

Climate shocks lead to an increase in domestic workloads and a reduction in paid employment opportunities for women. The overall supply of women's domestic labour could increase by 0.18 per cent in Scenario 1 and by 0.23 per cent in Scenario 2, with a greater impact observed in rural areas. In rural regions, women's domestic workload could increase by 0.20 per cent in Scenario 1 compared to 0.16 per cent in urban areas, while in Scenario 2, the increase could reach 0.28 per cent in rural areas versus 0.17 per cent in urban areas. This disparity underscores the heavier burden that rural women bear in the face of climate shocks.

The impact of climate change on human health further compounds the challenges faced by women. Rising temperatures are associated with an increase in vector-borne diseases such as malaria, hypertension, dengue fever, and cholera (Sorensen et al., Reference Sorensen, Saunik, Sehgal, Tewary, Govindan, Lemery and Balbus2018), which disproportionately affect pregnant women, children, and the elderly. In Burkina Faso, as in many African countries, women are primarily responsible for caring for sick family members, a role that becomes even more demanding when climate shocks threaten the availability of medicinal plants and traditional remedies, forcing women to spend more time searching for these scarce resources.

In addition, reduced rainfall exacerbates water scarcity, increasing the time and effort required for water collection, a task that predominantly falls on women. Water shortages lead to longer waiting times at wells, further limiting women's ability to engage in income-generating activities. Similarly, rising temperatures contribute to deforestation and drought, making firewood increasingly difficult to find. Women must travel longer distances in search of these essential household resources, intensifying their already heavy domestic burdens.

These findings are consistent with previous research by Dickin et al. (Reference Dickin, Segnestam and Dakouré2021) and Graham et al. (Reference Graham, Hirai and Kim2016), who also identify increased time spent on domestic chores such as water and firewood collection as a common coping strategy among women facing climate shocks. However, Shayegh and Dasgupta (Reference Shayegh and Dasgupta2024) challenge the assumption of a linear relationship between climate shocks and domestic labour supply, suggesting that beyond a certain threshold, extreme climate conditions may actually reduce women's ability to engage in any form of labour.

Alongside the increase in unpaid domestic work, climate shocks significantly reduce women's participation in the labour market. The supply of paid employment for women may decrease by 3.4 per cent in Scenario 1 and by 3.9 per cent in Scenario 2, with notable differences between urban and rural areas.

In Scenario 1, where the primary shock is rising temperatures, the decline in paid employment is more pronounced in urban areas than in rural areas. Urban women account for 69.9 per cent of the workforce in paid employment, compared to only 7.1 per cent for rural women (INSD, 2006). However, urban employment opportunities, particularly in food retail, fruit and vegetable sales, and oilseed trade, are highly vulnerable to climate shocks. Rising temperatures accelerate food spoilage, leading to reduced sales and increased agricultural product prices, making these sectors less profitable. Additionally, without adequate transport, many women must travel long distances to access supplies, further limiting their ability to engage in market activities.

In Scenario 2, where the primary shock is declining precipitation, the decline in women's labour supply is greater in rural areas than in urban areas. Rural women typically engage in cereal marketing, food processing (fritters, millet and peanut pancakes), handicrafts, and local beverage production (millet-based beer), all sectors that are directly tied to agricultural productivity. The decline in agricultural yields due to reduced rainfall results in lower production of raw materials, thereby limiting rural women's ability to sustain these businesses.

Additionally, rural women carry a disproportionate share of family responsibilities, including water and firewood collection and food provision (ILO, 2019). As resources become scarcer due to climate shocks, these tasks become even more time-consuming, leaving women less time and energy for income-generating activities. In some cases, women prioritize saving their limited financial resources for emergency needs, rather than reinvesting in business ventures, as a strategy to cope with unpredictable climate conditions.

These findings align with previous studies by Sanon (Reference Sanon2012) and Chitiga et al. (Reference Chitiga, Maisonnave, Mabugu and Henseler2019), who document a negative relationship between climate change and women's labour force participation. However, they contrast with the results of Babugura (Reference Babugura2010) and Jungehülsing (Reference Jungehülsing2010) who suggest that climate shocks can actually increase women's participation in paid employment, often as a survival strategy.

4.4. Impact of climate shocks by skill level

Given the importance of human capital as a determinant of women's labour market participation, this research also explores how climate change affects women differently based on their level of qualification. The results, presented in Table 5, show that skilled women are more affected by job losses than their unskilled counterparts. The supply of paid work for skilled women could decrease by 6.06 per cent in Scenario 1 and by 6.67 per cent in Scenario 2, while for unskilled women, the decrease could reach 0.65 per cent and 1.08 per cent, respectively.

Table 5. Impact of climate change on labour supply according to skill level

This discrepancy is partly explained by the high concentration of skilled women (47 per cent) in non-agricultural sectors (INSD, 2018). In Burkina Faso, skilled women predominantly work in agri-food processing and catering, sectors that depend heavily on agricultural raw materials (OECD, 2018). The decline in agricultural yields, fruit production, and livestock availability due to climate shocks results in reduced supplies for food processing and manufacturing industries, leading to lower labour demand for skilled women. These findings are consistent with the work of Escalante and Maisonnave (Reference Escalante and Maisonnave2022) and Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Ding, Han, He and Zhang2023), who also observed a strong link between climate-induced agricultural declines and job losses among women in food processing and trade. However, they contradict the conclusions of Dasgupta et al. (Reference Dasgupta, van Maanen, Gosling, Piontek, Otto and Schleussner2021) and Shayegh and Dasgupta (Reference Shayegh and Dasgupta2024), who argue that low-skilled workers are more vulnerable to climate-related employment losses than their skilled counterparts.

As a consequence of job losses, skilled women shift part of their lost working hours to domestic labour, though to a lesser extent than unskilled women. In Scenario 1, the domestic labour supply of skilled women could increase by 0.29 per cent, while for unskilled women, it rises by 0.065 per cent. In Scenario 2, the increase could reach 0.33 per cent for skilled women and 0.17 per cent for unskilled women. This reflects the economic adaptation strategies adopted by women, where job losses in the labour market lead to a reallocation of time toward unpaid domestic responsibilities.

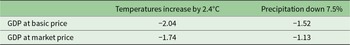

4.5. Impact of climate change on the economy

The impact of climate change on women's labour supply extends beyond individual employment outcomes, influencing the entire Burkinabe economy (Table 6). The decline in women's participation in paid work and the increase in domestic labour burdens contribute to an overall reduction in economic activity, ultimately affecting GDP growth.

Table 6. Impact of climate change on GDP

In Scenario 1, where temperatures rise, real GDP at market prices – which reflects the total value added from the production of goods and services – declines by 1.74 per cent, while in Scenario 2, characterized by reduced precipitation, it falls by 1.13 per cent. Similarly, real GDP at basic prices, which represents the production and distribution of primary resources across industries, contracts by 2.04 per cent in Scenario 1 and 1.52 per cent in Scenario 2.

Several factors explain these results. First, the decline in agricultural value added reduces the country's export capacity, forcing Burkina Faso to increase its reliance on imports, which negatively impacts trade balances. Second, the decline in women's paid labour supply leads to a drop in household income, reducing final consumption and investment expenditures, which further slows economic activity. Third, the reduction in agricultural yields affects the availability of raw materials for agro-industries, limiting production capacities. In addition, agricultural processing industries are severely impacted by rising and unstable prices of agricultural products, making it difficult for businesses to maintain stable production levels.

These findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating the significant macroeconomic costs of climate change. Stern (Reference Stern2007) estimates that if no mitigation measures are taken, climate change could cost up to 5 per cent of global GDP annually by 2100. Similarly, Nordhaus (Reference Nordhaus2018) projects a loss of 8.5 per cent of GDP for a 6°C temperature increase by the end of the century. The findings in this study align with these global projections, reinforcing the urgent need for climate adaptation strategies to mitigate economic losses and protect vulnerable populations, particularly women, from the disproportionate burdens of climate change.

4.6. Robustness tests of the results: sensitivity analysis

The simulation results confirm that climate change has a negative impact on women's labour supply in Burkina Faso. However, these findings are sensitive to the parameters used in the model calibration, meaning that even small variations in these parameters could lead to changes in the main results.

To ensure the robustness of these findings, the literature commonly employs sensitivity analysis on the elasticity parameters used in CGE models (Zidouemba et al., Reference Zidouemba, Kinda, Nikiema and Hien2018; Escalante and Maisonnave, Reference Escalante and Maisonnave2022). This approach involves adjusting the values of substitution elasticities between key variables to evaluate the stability of the model's predictions.

Following this methodology, this study conducts a sensitivity analysis by modifying the elasticities of substitution between male and female labour supply in the labour market. Specifically, the values assigned to these elasticities are doubled and then reduced by 50 per cent to examine the extent to which the main results hold under different assumptions. This approach allows for an assessment of the reliability of the model's conclusions regarding the impact of climate change on women's labour participation.

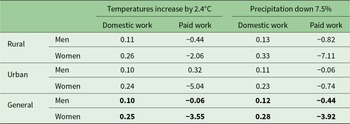

4.6.1. Increase in the values of the elasticities of substitution

The results presented in Tables 7 and 8 indicate that higher elasticity values lead to a slightly greater increase in domestic work supply and a more pronounced decline in paid employment for women, compared to the baseline simulation. In Scenario 1 (temperature increase) and Scenario 2 (precipitation decline), the supply of domestic work for women could increase by 0.25 per cent and 0.28 per cent, respectively, whereas in the baseline simulation, these increases were 0.18 per cent and 0.23 per cent. Similarly, the supply of paid work for women may decrease by 3.55 per cent and 3.92 per cent, compared to 3.4 per cent and 3.5 per cent in the baseline scenario.

Table 7. Impact of climate change on labour supply depending on the area of residence

Table 8. Impact of climate change on labour supply according to skill level

When disaggregating by area of residence, the results confirm that the increase in domestic work supply is more pronounced in rural areas than in urban areas. In the high elasticity scenario, domestic work supply could increase by 0.26 per cent and 0.33 per cent in rural areas, compared to 0.20 per cent and 0.28 per cent in the baseline simulation.

A similar trend is observed when analysing the results by qualification level. Regardless of skill level, the adjustments due to higher elasticities lead to greater variations in labour supply compared to the baseline scenario, reinforcing the initial findings that climate change disproportionately increases women's domestic workload while reducing their participation in the paid labour market.

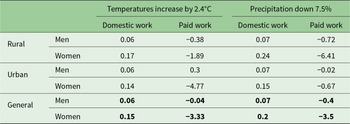

4.6.2. Reduction of the values attributed to the elasticities of substitution by 50 per cent

The results presented in Tables 9 and 10 indicate that lower elasticity values continue to produce positive effects on domestic work supply and negative effects on paid employment for women, though the magnitude of these impacts is less pronounced compared to the baseline simulation.

Table 9. Impact of climate change on labour supply depending on the area of residence

Table 10. Impact of climate change on labour supply according to skill level

As observed in previous simulations, women remain the most affected group, regardless of their qualification level or area of residence. However, when using lower elasticities, the increase in domestic work supply is slightly smaller, with values of 0.15 and 0.2 per cent in Scenarios 1 and 2, respectively, compared to 0.18 and 0.23 per cent in the baseline simulation. Similarly, the decline in women's paid labour supply is also slightly reduced, with a decrease of 3.33 and 3.5 per cent in Scenarios 1 and 2, respectively, compared to 3.4 and 3.5 per cent in the baseline scenario. These results suggest that while the overall trend remains unchanged, the degree of labour market adjustment in response to climate shocks depends on the elasticity values used in the model. A lower elasticity of substitution reduces the sensitivity of labour supply adjustments, meaning that women's shifts between paid and domestic work occur at a slower rate when substitution between different forms of labour is more rigid.

The analysis of the sensitivity scenarios reveals only minor variations compared to the baseline simulation, confirming the overall robustness of the results. As in the previous simulations, climate shocks continue to have a dual impact, increasing the supply of domestic labour while reducing women's participation in paid work. Regardless of qualification level or area of residence, the trends observed in the sensitivity scenarios remain consistent with those in the baseline simulation. While variations in elasticity values lead to slight fluctuations in the magnitude of these effects, the overall direction and significance of the impact remain unchanged.

These findings reinforce the robustness of this research, as the sensitivity analysis does not indicate any substantial deviation in the way climate shocks affect women's economic activities. This consistency across different scenarios strengthens confidence in the model's predictions and underscores the systematic link between climate change and gendered labour market dynamics in Burkina Faso.

5. Conclusion and implication of economic policies

Climate change is reshaping economic landscapes across the globe, and in Burkina Faso, its impact is particularly evident in the agricultural sector and the labour market. While a vast body of research has explored the economic consequences of climate change in Burkina Faso, few studies have examined its specific impact on women's economic activities. Women play a crucial role in both agricultural production and domestic labour, yet their vulnerability to climate shocks remains poorly understood. This research seeks to fill that gap, analysing how rising temperatures and declining rainfall affect women's labour supply, economic participation, and overall well-being.

Using a static CGE model, calibrated with a gender-disaggregated SAM, this study evaluates two key climate change scenarios. The first scenario simulates the effects of a 2.4°C increase in temperature on agricultural yields, while the second examines the consequences of a 7.5 per cent reduction in precipitation on water availability by 2050. In addition to economic modeling, the analysis is supported by household survey data from the National Institute of Statistics and Demography (INSD, 2018) and time-use data from the OECD (2018).

The findings reveal that climate change deepens gender inequalities in Burkina Faso's labour market, exacerbating the already unequal distribution of paid and unpaid work. As extreme weather events reduce agricultural productivity, women are forced to allocate more time to domestic tasks, while simultaneously losing access to formal employment opportunities.

Rural areas are the most affected, as women's labour supply shifts disproportionately toward unpaid domestic work. In regions where access to water, firewood, and other essential resources is already precarious, declining precipitation intensifies the burden on women, who must travel longer distances to secure these necessities. The research also shows that skilled women are more affected by job losses than their unskilled counterparts, as they are more likely to work in sectors dependent on agricultural supply chains, such as food processing and trade.

This shift in labour dynamics has macroeconomic consequences. The loss of women's participation in the formal labour market contributes to a decline in real GDP, affecting both household income and national economic stability. The results highlight the urgent need for targeted policies to support women's economic resilience in the face of climate change.

Climate change is reshaping economic and social structures, with women bearing a disproportionate share of its impacts. As climate shocks reduce agricultural yields and intensify domestic responsibilities, targeted adaptation strategies are essential to protect women's livelihoods and economic opportunities.

One of the most pressing challenges is the impact of climate change on agriculture, particularly cereal crops and fruits, which are staple foods in Burkina Faso. To counteract declining yields, climate-smart farming techniques must be promoted to ensure food security and women's income, in line with the UN's Sustainable Development Goal 2.

At the same time, women's domestic workload is increasing, as water sources dry up, firewood becomes scarcer, and caregiving responsibilities expand due to climate-related health risks. To ease this burden, investments should focus on subsidizing butane gas, constructing water wells, expanding access to childcare and elderly care, and providing free healthcare for children.

Beyond the household, climate change is also threatening women's participation in agro-food processing and trade, as rising temperatures accelerate food spoilage and disrupt supply chains. To sustain these industries, policies must improve food storage infrastructure, facilitate access to credit, and introduce labour-saving technologies that increase efficiency and reduce physical strain.

Finally, with agriculture becoming increasingly unpredictable, it is crucial to diversify women's economic opportunities beyond farming. Encouraging female entrepreneurship through vocational training linked to financing, investment in climate-resilient sectors, and the development of skills in digital services and small-scale industries can provide more stable and sustainable income sources.

It is important to acknowledge certain limitations of the model that could influence the interpretation of the results. One key limitation is the exclusion of leisure from the time allocation framework. In reality, individuals make trade-offs between market labour, domestic work, and leisure, and the omission of leisure may lead to an incomplete representation of labour supply adjustments in response to climate shocks. This simplification assumes that any reduction in paid work or increase in domestic responsibilities directly translates into a shift between these two activities, without considering how individuals might also adjust their leisure time. Future research should incorporate leisure as a separate choice variable to provide a more nuanced understanding of labour allocation dynamics, particularly in response to climate-induced economic disruptions.

Additionally, the model operates within a static framework, meaning it does not account for long-term adaptation strategies that households and businesses might adopt over time. Climate change effects unfold over decades, and individuals may adjust their skills, migration decisions, or employment choices in response to evolving environmental conditions. A dynamic modelling approach could help capture these progressive adaptation mechanisms and provide a more comprehensive assessment of the long-term gendered impacts of climate change.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X25100387.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or known personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.