“Story” is the basis of the American Indian oral tradition . . . the vehicle for sharing traditional knowledge and passing it from one generation to the next. . . . When story is told effectively, it transcends time, as traditional knowledge lives on with each new listener becoming part of them and a part of the next generation [Fixico Reference Fixico2025:17].

Two coauthors are Western scientists who have been exploring the interrelationships between pinyon pine and Indigenous people of the Great Basin (Millar and Thomas Reference Millar and Thomas2026; Thomas and Millar Reference Thomas and Millar2023, Reference Thomas and Millar2024). After the authors presented some of their hypotheses at the 2023 Great Basin Anthropological Conference in Bend (Oregon), an Indigenous Nevadan commented, “You’re claiming that most pinyon came from the south. My tribe knows that pine nuts came from the north.” Millar and Thomas had prided themselves on integrating their distinctively diverse ecological and archaeological viewpoints, but when this tribal elder interjected his Indigenous perspective on these same issues, they immediately recognized their own shortsightedness.

This article reflects the resulting collaboration among members of five federally recognized tribes in the Great Basin,Footnote 1 a non-Native forest ecologist, and a non-Native anthropological archaeologist. We acknowledge that Indigenous ontologies differ significantly from the perspectives of Western science: “The Indigenous way of seeing things is . . . incongruent with the linear world. The linear mind looks for cause and effects, and the Indian mind seeks to comprehend relationships” (Fixico Reference Fixico2025:7). Although Indigenous communities often recognize a North American antiquity from Time Immemorial, “time is not a limiting factor in how memory work facilitates place-bound interactions with spirits, ancestors, and one another” (Zedeño et al. Reference Zedeño, Pickering and Lanoë2021:311). Instead, as Keith Basso (Reference Basso1996) aptly expressed it, “wisdom sits in places”—meaning that Indigenous oral histories typically function more like time capsules; they are overridden by the strong sense of space and place and thereby transcend linear time per se (Deloria Reference Deloria1973:80; Fixico Reference Fixico2025:18–21). We further acknowledge that what Western science deems “inanimate” is currently subject to ongoing cross-cultural reevaluation (Cruikshank Reference Cruikshank2005; Kimmerer Reference Kimmerer2013).

Viewing this ontological diversity as a strength, together we address Theft of Pine Nuts (TPN), one of the most widespread Indigenous oral histories in the Great Basin (Liljeblad Reference Liljeblad, d’Azevedo and Sturtevant1986).Footnote 2 We have assembled 61 variants of TPN (and closely related pinyon-origin legends) transcribed over the past 152 years. Contemporary Paiute, Shoshone, and Wá∙šiwFootnote 3 storytellers still share these narratives, and all five Indigenous collaborators heard one or more versions while growing up.

Four themes emerge: (1) pine nuts have been a driving force in Indigenous Great Basin lifeways for millennia, (2) several TPN oral histories pinpoint pine-nut homelands far beyond where pinyon trees grow today,Footnote 4 (3) TPN narratives encode shifting animal biodiversity in the past, and (4) massive ice barriers (likely dating to the Late Pleistocene) often thwarted pine-nut thieves. We believe these tribal oral histories offer fresh proxies from which Western science can test, expand, and reconstruct Quaternary relationships between Indigenous people and pinyon pine in the Intermountain West.

What Does Indigenous Oral History Mean?

After reciting a tribal oral history, one Southern Paiute elder emphasized, “This is not just a story; it is a true story” (quoted in Hittman Reference Hittman2013:210–211). Stoffle and Zedeño (Reference Stoffle and Zedeño2001:232–233) agree that Indigenous Numic oral history transcends mere “fairy oral histories” or “just-so-stories” because “oral history is much more than just words. . . . [It is] what has happened.” Fowler (Reference Fowler and Smith1993:xxxi) singled out Theft of Pine Nuts as “a testimony to the strength and power of oral tradition to those who might think that only written traditions can survive through time.”

Many have disagreed. After personally transcribing and publishing more than 70 pages of Numic oral histories, anthropologist Robert Lowie admonished readers never to “attach to oral traditions any historical value whatsoever under any conditions whatsoever” (Reference Lowie1915:598). Doubling down in his retirement address as president of the American Folklore Society, Lowie compared scientists believing that Indigenous oral traditions have “historical value” to “circle-squarers and inventors of perpetual-motion machines, who are still found besieging the portals of learned institutions” (Lowie Reference Lowie1917:161; see also Radcliffe-Brown Reference Radcliffe-Brown1952:3). Reinforcing this hard-lined, physics-based scientific professionalism of his mentor Franz Boas, Lowie set the tone for a century of Great Basin anthropology. Considerable tension remains today regarding the use of oral traditions in archaeology (e.g., McGhee Reference McGhee2008), which still at times dismisses Indigenous oral history as merely “myth” (Myers Reference Myers2001).

Standing Rock Sioux scholar Vine Deloria countered with the following statement:

Myth [is] a general term given to traditions of non-Western peoples. It basically means a fiction created and sustained by undeveloped minds [separating] non-Western traditions from the mainstream of science and keeping them comfortably lodged in the fiction classification because most of them contain references to activities of supernatural causes and personalities and are not phrased in the sterile language of cause and effect [Reference Deloria1995:186].

We join Deloria and many others in believing that Indigenous tribal oral histories can indeed, at times, reflect eyewitness observations that potentially provide new insights into the deep past (Angelbeck et al. Reference Angelbeck, Springer, Jones, Williams-Jones and Wilson2024; Deur Reference Deur2002; Echo-Hawk Reference Echo-Hawk2000; Ives Reference Ives, Johnson and Arlidge2024; Liljeblad Reference Liljeblad, d’Azevedo and Sturtevant1986; Sutton Reference Sutton1989, Reference Sutton1993; Wewa and Gardner Reference Wewa and Gardner2017; Whiteley Reference Whiteley2002; Zedeño et al. Reference Zedeño, Pickering and Lanoë2021).

Recording Great Basin Oral History

During the decade following the 1859 Comstock silver discovery, Indian agent Jacob Lockhart watched the local Indigenous population plummet and advised Nevada governor James W. Nye that “in view of their rapidly diminishing numbers and the diseases to which they are subjected . . . the Washoes would soon all be gone, and the need for a reservation would be eliminated” (Price Reference Price1980:13). But resilient Wá∙šiw, Paiute, and Shoshone communities refused to go extinct, shifting their seasonal economies to the demands of wage labor, attaching themselves to mines and ranches alongside white settlers, and defining new niches to maintain their deep cosmological ties to sacred pinyon stands and ancestral mortuary places.

US president Ulysses S. Grant tried to forestall such tribal resilience with an aggressive policy of de-Indianizing the Indians. The Carson Indian School (later called the Stewart Indian School) opened in 1890 specifically to assimilate Paiute, Shoshone, and Wá∙šiw youngsters, shearing off their hair and forbidding Native languages (Williams Reference Williams2022). In the 1920s, Superintendent J. E. Jenkins (Reno Indian Agency) expanded the process to abolish all traditional ceremonies because they were “heathenish,” “savage,” and “barbarous.” He banned Indigenous healing practices because each “doctor [functioned as] a spiritual leader, a judge in civil and political matters of the tribe as well in family disturbances” (Nevers Reference Nevers1976:81–82).

Assimilation politics failed to halt the uniquely Indigenous survivance strategies of Great Basin tribes (Supplementary Material 1). Wá∙šiw Elder Melba Rakow recalls an aunt telling stories of standing up to school authorities: “She would gather girls together for games on the playground and speak in Washoe; she didn’t care about the punishment that would follow” (Gordon Reference Gordon2019). Shortly after the Walker River Day School opened in 1890, Paiute students repeatedly ran away to harvest fall pine nuts with their families—not returning until pine-nutting was complete. Families also retreated into remote deserts and mountains to keep passing along their sacred knowledge and oral histories, which grandparents typically recounted at night to children until they fell asleep.

The assimilation agenda alarmed the so-called salvage anthropologists, and many headed west to record the remnants of traditional subsistence practices, ceremonies, religion, dances, and languages from the “vanishing Indian” (Redman Reference Redman2021). During the formative period of American anthropology, Franz Boas (American Museum of Natural History and Columbia University) dispatched doctoral students Alfred Kroeber, Robert Lowie, and Edward Sapir to the Great Basin to seek out those who understood “the importance attached to storytelling, not only as entertainment but also for its presumed educational value, made the storyteller an indispensable member of the local group” (Liljeblad Reference Liljeblad, d’Azevedo and Sturtevant1986:650). These Boasian students (and, eventually, their own students) recorded more than 1,000 Numic and Wá∙šiw oral histories (summarized in Supplementary Materials 2 and 3)—33% before 1925 and another 60% in the next quarter century—in effect, reifying the aphorism that “it’s not oral history until a white anthropologist writes it down.”

This all changed when Red Power activism emerged from the 1960s civil rights movement. Inspired by the Alcatraz takeover and the American Indian Movement, Great Basin tribes evolved new ways of passing along their language, practices, and histories to younger generations (Crum Reference Crum1994:56, 160–165; Jorgensen Reference Jorgensen, d’Azevedo and Sturtevant1986; Thomas Reference Thomas2000). Several tribes started their own newspapers, and no fewer than a dozen published their own tribal histories between 1972 and 1983 (Alley Reference Alley, d’Azevedo and Sturtevant1986:Table 1). When tribal member Jo Anne Nevers (Reference Nevers1976:1) wrote WA SHE SHU: A Washo Tribal History, she explicitly “tried to portray, from our viewpoint . . . Washo life as we have known it.” In the process, Great Basin tribes preserved literally hundreds of tapes and transcripts of their storytellers within tribal archives: “In a very real sense, [these] archives represented a transfer to Indian communities some measure of power over their own lives” (Alley Reference Alley, d’Azevedo and Sturtevant1986:604).

Theft of Pine Nuts Oral Histories

Theft of Pine Nuts is a remarkably widespread story of still-remembered experiences from the timeless cosmological age of the trickster Coyote and the other animal people (Hultkrantz Reference Hultkrantz, d’Azevedo and Sturtevant1986). Untold generations of Indigenous storytellers repeated the Theft of Pine Nuts, first transcribed in 1873 when Northern Paiute Elder Naches told How Pine Nuts Were Obtained to John Wesley Powell (then-director of the Smithsonian’s Bureau of Ethnology; Fowler and Fowler Reference Fowler and Fowler (editors)1971:247–248). Relatively well versed in the Ute and Southern Paiute languages, Powell translated the Northern Paiute storyline into English, which we summarize this way:

In the world before humans, pinyon was absent from Coyote’s land, but he and his animal companions could smell pine nuts cooking far off. They traveled north to steal some pine nuts and bring them home. But the land of Sand Hill Crane was covered with an Ice Sky. Coyote tried to break through the ice by running at it, but he only broke his nose and everyone laughed. Lightning Hawk then flew high up and zoomed down to break open the ice. Back in his homeland, Coyote chewed the stolen pine nuts, then spit them all over the ground, where they grew. This was the origin of the pine-nut trees about the Tiv-a Kaiv, pine-nut mountain.

Four decades later, an unidentified Northern Shoshone storyteller in Lemhi (Idaho) told Robert Lowie (Reference Lowie1909:246–247) an almost identical legend called The Theft of Pine Nuts.

Table 1 documents five dozen variants of TPN oral histories, and Figure 2 plots our best estimates of where each narrative was told (amplified in Supplementary Material 5; select narratives appear in Supplementary Material 4). Coauthor Misty Benner first heard Theft of Pine Nuts in 1985 from her father (Walker River Paiute) when they lived in northern California; 15 years later, her grandparents shared similar pine-nut stories during the wintertime on the Schurz reservation (Table 1:Legend #21). Coauthor Donna Cossette (Fallon Paiute Tribe) listened to Mother of the Pine Nut in 1993–1994 at her family’s traditional pine-nut camp in the northern Stillwater Range, as told by her aunt Helen Thomas Williams (a Koop-Ticutta) and Toi-Ticutta Elder Helen Stone (who had just published this story in Coyote Tales and Other Paiute Stories You Have Never Heard Before [Stone Reference Stone1991:40–49]; Table1:Legend #39).

Table 1. Compiled List of the 61 Versions of Theft of Pine Nuts Oral Narrative Analyzed in This Study.

Coauthor Wilson Wewa (Paiute/Palouse) began learning tribal oral histories in the 1970s and then traveled with his grandmother throughout the western Great Basin to compile the narratives he eventually published in Legends of the Northern Paiute (Wewa and Gardner Reference Wewa and Gardner2017:xiiv): “Part of being a Northern Paiute, a little part of it, has now been told and written in the oral histories and stories of this book.” Wewa synthesized several partial versions of TPN heard from family members at Schurz and Pyramid Lake into Wolf Makes Pine Nut Trees (Wewa and Gardner Reference Wewa and Gardner2017:25–26; Table 1:Legends #33 and 40).

Coauthor Herman Fillmore heard Legend of the Large Bird That Grew Pine Nuts (Table 1:Legend #52) in 1999 or 2000 while attending the immersion school Wá∙šiw Wagayay Maŋal (“the house where Wá∙šiw is spoken”). Here, tribal elders spoke the Wá∙šiw language to teach preschoolers through eighth graders traditional cultural values and oral histories (covering all subjects except math, because no known vocabulary for mathematics exists in Wá∙šiw). Today serving as the tribe’s culture/language resources director, Fillmore worked alongside tribal teachers Lisa Enos, Melba Rakow, Mischelle Dressler, and Mitchel Osorio to develop a children’s book featuring this oral history in both Wá∙šiw and English languages (Enos and Rakow Reference Enos and Rakow2014).

Coauthor Diane Teeman (Burns Paiute tribal member) first heard Theft of Pine Nuts from her great-aunt gapu Footnote 5 Lillian Frank Maynard in the early 1980s. Teeman and illustrator Brett A. Sam are presently preparing this storyline in Neme yaduana (“Paiute talk”) for the Burns Paiute Tribe’s language-immersion preschool to promote literacy in Neme yaduana and perpetuate tribal oral history and culture.

The considerable variability within such a “story” enhances (rather than diminishes) the credibility of the narrated events, with the multiple versions of a single oral history suggesting both age and social importance (Nabokov Reference Nabokov2002). Some oral narratives survive multiple generations because they periodically enrich material contexts and events with new experiences (Zedeño et al. Reference Zedeño, Pickering and Lanoë2021). We believe that the tribal oral histories embodied in Theft of Pine Nuts can help bridge a chasm that has long separated Indigenous knowledge from Western scientific perspectives.Footnote 6

Why Were Pine Nuts a Driving Force in Indigenous Lifeways?

Indigenous Perspectives on Pine Nuts

In 1873, Northern Paiute Elder Naches told of the animal people holding a great council to decide what foods are the best. Little Rabbit (Ta-vu) said,

Let us go to sleep and dream. All who have good dreams can eat pine-nuts, and all who have not must search for something else. So they fell into a deep sleep. Pi-aish, It-sa, the mountain sheep, and many others had bad dreams. Others there . . . had good dreams. When they all awoke from their sleep those who had thus learned that they were to live on pine-nuts went away to the mountains where the pine-nuts grew, but those who had bad dreams remained behind and complained bitterly of their lot [Fowler and Fowler Reference Fowler and Fowler (editors)1971:218].

In 1930, Billy Steve (Northern Paiute, Table 1:Legend #2) echoed these sentiments, with Coyote explaining why he stole pine nuts from his neighbors: “‘Why, I smell something good’ [and] went toward the north. . . . After Coyote had eaten those pine nuts, he went home. . . . The girls all wanted to dance with Coyote because they could smell that he had eaten something good. They said, ‘This young man smells good’” (Kelly Reference Kelly1938:395–396).

Great Basin Indigenous oral histories reinforce the power of pine nuts as both being food and possessing deeper cosmology. When Captain Jim (Wá∙šiw) visited US president William Henry Harrison, he held out a handful of pine-nut flour and said simply, “This food from the pine nut trees is what my people eat . . . it is the same as our mother’s milk” (Inter-Tribal Council of Nevada 1974:14). Sorely tested over the past two centuries (Supplementary Material 5), this unique relationship to pinyon pine nuts remains a sacred part of many Indigenous lifeways in the Great Basin.

Western Science Perspectives on Pine Nuts

John C. Frémont became “almost obsessed” with pinyon pine in January 1844 during his wintertime traverse of the Sierra Nevada after he purchased from Indigenous locals a skin bag with a few pounds of pine nuts: “When roasted, their pleasant flavor made them an agreeable addition to our now scanty store of provisions” (Frémont Reference Frémont1845). Wá∙šiw pine nuts are also credited with rescuing survivors of the ill-fated Donner Party two years later (Lanner Reference Lanner1981:96–97). The existence of junipers was well known to Western scientists, but Frémont would bring pinyon pine to their attention, having formally recorded the name Pinus monophylla in his journal.

Western science has since overwhelmingly confirmed Frémont’s conclusion that pine nuts were an Indigenous staple. Anthropologist Julian Steward (Reference Steward1938:27) agreed that, although ethnohistoric Shoshoneans consumed more than three dozen plant species, pinyon pine remained “the most important single food source where it occurs.” Although subsequent research has nuanced Steward’s generalization, today’s archaeology solidly demonstrates that significant pinyon procurement spans at least 7,000 years (Thomas and Millar Reference Thomas and Millar2024).

As the pinyon-pine woodland spread across much of the upland Great Basin during the Holocene, it offered a readily available, easily stored resource that facilitated Indigenous dispersals into these same regions at the same time. Although pinyon pine did not “cause” these Indigenous movements (Thomas and Millar Reference Thomas and Millar2024), pine nuts doubtless underwrote the costs of large-scale get-togethers such as fandangos and sweat-house gatherings (Robinson and Thomas Reference Thomas2024; Thomas Reference Thomas2024). Pine nuts also helped hunters, and it is hardly coincidental that the widespread distribution of the 100+ large-scale communal artiodactyl hunting facilities closely correlates with the spread of the pinyon woodland (Hockett and Dillingham Reference Hockett and Dillingham2023:124). These supravillage gatherings not only expedited social networking by strengthening kinship ties and group solidarity but also expanded the local gene pool, enhancing both individual and group fitness (MacDonald and Hewlett Reference MacDonald and Hewlett1999; Thomas and Millar Reference Thomas and Millar2024). In these ways, pinyon-nut procurement became a driving force that helped define Indigenous lifeways for millennia (Supplementary Material 5).

Pine nuts played a survivance role in the Indigenous Great Basin in a way reminiscent of American bison and Great Plains foragers. Despite the deep dependence on pine nuts or bison, the ecological consequences attached to these paramount staples facilitated vastly different behavioral responses. Great Plains mobility was long conditioned by migratory patterns of bison herds across the prairie. Pine nuts, what Frémont called “this simple vegetable”—quite literally rooted in one place—are best exploited through seasonal mobility patterning. Bison and pine nuts were pivotal resources that triggered complex behaviors fostering distinctive social cohesion and cultural traditions spanning millennia.

Why Do Theft of Pine Nuts Oral Histories Reflect Pinyon on the Move?

Indigenous Perspectives

The Theft of Pine Nuts storyline describes animal people traveling to places where pinyon trees grew. Forty-one of the TPN oral histories specify the direction of distant pine nuts from the narrator’s homeland (Table 1): north (27), east (7), west (4), and south (3). Surprisingly, only one-third of the TPN variants identify pine-nut homelands within the current range of today’s pinyon woodland.

Western Science Perspectives

Why do so many Theft of Pine Nuts narratives pinpoint pine-nut homelands where pinyon does not grow today? Western science approaches this inquiry by questioning whether the “pine nuts” featured in the TPN stories were actually Pinus monophylla. In Millar et alia (Reference Millar, Thomas, Benner, Cossette, Fillmore, Teeman and Wewa2025) we thoroughly dissect this issue and conclude that in regions where pinyon pines currently grow, the TPN narratives almost certainly refer to a species of extant pinyon (Pinus monophylla and/or Pinus edulis). Because this assumption becomes more challenging for narratives told outside the current distribution of pinyon, we also entertain the possibility that pine nuts referenced in the TPN oral histories could be taxa other than pinyon—including limber pine (P. flexilis), sugar pine (P. lambertiana), whitebark pine (P. albicaulis), and/or ponderosa pine (P. ponderosa).Footnote 7

Singleleaf pinyon pine (Pinus monophylla) and its relatives (Pinus subsection Cembroides) evolved more than 60 million years ago in southwestern North America (Millar et al. Reference Millar, Thomas, Benner, Cossette, Fillmore, Teeman and Wewa2025), migrating north and south in sync with glacial-interglacial fluctuations. The latest Pleistocene cold climates in the central and northern Great Basin forced pinyon to retreat southward into an ice-age Mojave Desert refugium. As temperatures warmed, pinyon pine migrated northward in ragged wave-like fashion across the Great Basin approximately 7,000–8,000 years ago, reaching its current northern boundary at today’s “pinyon curtain”—roughly parallel to the Humboldt River—only within the last few centuries (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Current distribution of singleleaf pinyon pine (dark shading) in the southwestern United States. Gray shading is the hydrological Great Basin (DataBasin; https://databasin.org/, accessed September 20, 2025).

Thomas and Millar (Reference Thomas and Millar2024) propose an alternate hypothesis (Millar and Thomas Reference Millar and Thomas2026). They argue that beyond the well-documented southern Mojave-region refugium, scattered ice-age pinyon populations must have persisted in high-latitude northern refugia, from which they expanded as climates became favorable (Figure 3). They also hypothesize that pinyon may have migrated north of the current “pinyon curtain” at times during the Middle Holocene but died out as climates cooled in the last 4,000 years.

Comparing Western Science and Numic Perspectives

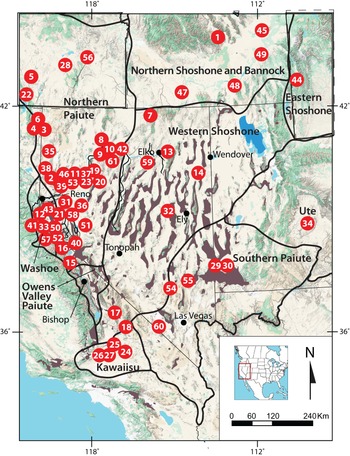

We can meld scientific and Indigenous ontologies in a tribe-by-tribe comparison of the 55 Numic-language variants of Theft of Pine Nuts (Table 1; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of 61 Theft of Pine Nuts oral histories in the Great Basin. The numbered red dots refer to the legend numbers listed on Table 1. Tribal boundaries are modified from d’Azevedo (Reference d’Azevedo and Sturtevant1986).

Southern Paiute (Legends #29, 30, 54, 55, 60)

After spending the Late Pleistocene in the lower elevations of the southern Mojave refugium, increasing Holocene temperatures pushed pinyon upslope and northward into the basins around the Spring Mountains and the Las Vegas region. All five Southern Paiute oral histories tell how the animal people imported pinyon pine from scattered nearby localities within 100 miles (160 km) of their homeland (likely the Spring Mountains), with no mention of ice barriers.

Nuwä [Kawaiisu]/Panamint (Legends #17, 18, 24, 25, 26, 27)

Pinyon persisted in the Mojave refugium into the Early Holocene, outside their current range until increasing temperatures extirpated pinyon pines in the foothills and lower elevations (Figure 3). These Nuwä narratives describe Coyote importing pine nuts from Owens Valley to the north, about 125 miles (200 km) away.

Figure 3. Hypothesized northward migration of pinyon pine from the southern Pleistocene refugium and outward from four Pleistocene refugia at higher latitudes in the western and eastern Great Basin. These are estimated from midden locations and radiocarbon dates (Supplementary Material 6) and, for the northeast California refugium, from ethnographic evidence and herbarium records (Millar and Thomas Reference Millar and Thomas2026). Brown polygons denote five Late Pleistocene refugia, red arrows show movement out of the refugia during the Early Holocene, and blue arrows show subsequent movement. Gray shading is the hydrologic Great Basin.

Paiute Oral Histories from Inyo-Mono

Figures 3 and 4 chart the Western science interpretation of pinyon pine progressively moving northward to arrive in Owens Valley by 11,000 BP.Footnote 8 With a single exception, the four dozen transcribed oral histories recorded by Steward (Reference Steward1936) in Inyo-Mono fail to include Theft of Pine Nuts. Maybe Coyote did not need to steal pine nuts from someplace else because pinyon pine flourished locally for a long time. Or perhaps, as Bettinger (Reference Bettinger and Beck1999) sees it, the superior plant resources of Owens Valley simply overshadowed pine nuts, with intensive pinyon procurement not beginning until approximately 1350 BP; Thomas and Millar (Reference Thomas and Millar2023) dispute this hypothesis.Footnote 9

Figure 4. Hypothesized Pleistocene and Early Holocene refugia for pinyon pine within the far western Great Basin (modified from Millar and Thomas Reference Millar and Thomas2026).

Legend #15 is the lone exception. Western science documents pinyon arriving in the Mono Lake region by around 5750 BP (Figure 4). Did Bridgeport Tom’s narrative describing Coyote smelling and stealing pine nuts to the east take place sometime before that? These animal people had to navigate a huge ice wall to get back home, making this classic Theft of Pine Nuts legend the southernmost mention of the massive ice barrier.

Paiute at Pyramid Lake, Walker Lake, and Dayton (Legends #2, 12, 21, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 46, 51, 53)

Pinyon pine reached the Stillwater Range about 1150 BP, Walker Lake (Wassuk Range) by 1100 BP, and Schurz by 800 BP (Figure 4). Several of these Northern Paiute oral histories describe Coyote bringing pine nuts back from homelands controlled by the Western, or Old Crane, people. All but four narratives (#12, 21, 35, and 51) describe impenetrable ice barriers.

Paiute in the Humboldt and Carson Sinks (Legends #8, 11, 16, 19, 20, 23, 31, 33, 61)

These nine TPN stories almost exclusively describe stealing pine nuts to the north of today’s “pinyon curtain” (Figure 1). Oral histories #11, 16, 19, and 20 also emphasize a seemingly impassible ice barrier separating them from the pinyon woodlands.

Surprise Valley Paiute (Legends #3, 4, 6)

Today, the pinyon-pine woodland nearest to Surprise Valley (northeastern California) grows more than 125 miles (200 km) to the south (near Reno, Nevada). The three local Gidii’tikadu (Groundhog eaters) oral histories tell of Coyote and Wolf once having access to local pine nuts, but when Coyote spit up the swallowed seeds, they grew into junipers. Wolf was more successful when he sprinkled pine-nut seeds to the south, where pinyon trees still grow. Narrative #3 details an ice barrier.

Paiutes in Oregon (Legends #5, 22, 28, 56)

All available TPN narratives support Diane Teeman’s (Burns Paiute) summary:

For us in the northernmost reaches of the cultural extent of the Great Basin, we have a story of stolen pine nuts as well, only our story tells us that pine nuts once grew here in southeastern Oregon, until they were stolen by Crow, who sliced a slit in his leg and hid the pine nuts in his wound then flew south with them [Teeman Reference Teeman2024:183].

In Legend #5, Nina Naneo (Northern Paiute, originally from Summer and Silver Lakes) tells of a local pinyon source 30 miles (50 km) from Yamsay Mountain and another at Gearhart Mountain, 20 miles (30 km) away. Oral histories #5 and #56 contain ice barriers.

Western Shoshone (Legends #7, 9, 10, 13, 14, 42, 59)

Western science documents the arrival of pinyon pine at Gatecliff Shelter (Western Shoshone territory), presumably having migrated from the Mojave refugium by 5290 BP. The archaeology demonstrates almost immediate Indigenous use of pine nuts (Thomas Reference Thomas1983).

Western Shoshone (Newe) scholar Steven Crum (Reference Crum1994:5–6) feels otherwise, noting that “although accounts vary, depending on the storyteller, all agree upon one thing: the pine nuts came to the Newe from a northern location.” Transcribed Western Shoshone TPN oral histories strongly support Crum, all but one specifying a northern pinyon source between Owyhee and Boise (Idaho). Arthur Johnson (Goshute; Legend #14) is the lone exception, with Coyote stealing pine nuts from someplace far to the west (toward California). Only narrative #7 includes an ice barrier.

Northern Shoshone (Legends #1, 32, 44, 45, 47, 48)

Although pinyon pine grows today in scattered Idaho localities, six Northern Shoshone TPN narratives point to a northern pinyon refugium. Oral history #32 describes an ice barrier.

Ute (Legend #34)

In Legend #34, Coyote smelled pine nuts on the east wind and, after stealing this “wonderful food” from the Crane People, he escaped through an ice door to plant pine nuts in his homeland. Kaelin (Reference Kaelin2017:91–99) locates this legend near the Four Corners area, but because this narrative was apparently derived from Kroeber (Reference Kroeber1901) and Mason (Reference Mason1910), the proper location is almost certainly southeast of Salt Lake City.

Implications

When direction is specified, roughly half of the Numic Theft of Pine Nuts oral histories point to pinyon trees growing to the north of the narrator. Based on a limited sample of these TPN oral histories, Mark Q. Sutton (Reference Sutton1987, Reference Sutton1993) concluded that the northern origin of pinyon was simply a natural geographic consequence of Lamb’s (Reference Lamb1958) Numic Spread hypothesis. Sutton argued that because Numic speakers were migrating northward within the last millennium from their Panamint / Death Valley Numic homeland, all pinyon-pine woodlands would naturally have been growing to their north.

We respectfully disagree. Multiple issues cloud the highly controversial Numic Spread hypothesis, the primary problem being the assumption of complete population replacement by Numic speakers within the last several centuries. Recent DNA and archaeological investigations indicate otherwise (Moreno-Mayar et al. Reference Moreno-Mayar, Vinner, de Barros Damgaard, Fuente, Chan, Spence and Allentoft2018; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Cossette, Benner, Camp and Robinson2025; Willerslev and Meltzer Reference Willerslev and Meltzer2021) and demonstrate that in the Great Basin (as elsewhere), language, biology, and culture must be treated as independent variables (per Boas [Reference Boas1904] in his founding principles of American anthropology).

The archaeological distribution of prayerstones underscores the same point (Stoffle et al. Reference Stoffle, Van Vlack, O’Meara, Arnold and Cornelius2021; Thomas Reference Thomas2019). Grounded in Southern Paiute oral history, the prayerstone hypothesis holds that selected incised stone artifacts served as votive offerings deliberately emplaced where spiritual power (puha) was known to reside; they were typically accompanied by prayers to receive personal power and to express thanks for prayers already answered. The 3,500+ documented prayerstones establish an unbroken cosmological continuity from pre–5000 BP at Gatecliff Shelter to the emplacement of 19 prayerstones in an 1880s Western Shoshone wickiup (Thomas Reference Thomas2019:14). Spanning seven states and seven millennia, these long-standing, multiple constellations of prayerstone practice undermine any assumption of complete population replacement by single, late, and simultaneous Numic spread across the Great Basin. For similar reasons, we believe that the 55 TPN narratives transcribed from Numic speakers could well span a vastly deeper history prior to the alleged arrival of the Numic language within the last several centuries.

Because so many Numic oral histories point to pine-nut homelands north of the modern pinyon boundary (Figure 1), we suggest the likely locations to be the Warner Mountains (11 cases), Owyhee (7), Pyramid Lake (6), Lemhi (3 [central Idaho and Wyoming]), the Santa Rosa Range (2), the Humboldt Range (1), and the Goose Creek Mountains (1). If so, then Theft of Pine Nuts narratives support the Thomas and Millar (Reference Thomas and Millar2024) hypothesis of pinyon-pine survival in high-latitude refugia or short-lived Holocene expansions that subsequently died out (Figure 3). These hypotheses clearly require additional testing, and at a minimum, TPN oral histories offer fresh proxies for Western scientists to confirm, refute, and/or expand previous judgments of pinyon-pine natural history.

Comparing Western Science and Wá∙šiw Perspectives

Of the six pinyon oral histories in the Wá∙šiw language (Legends #43, 49, 50, 52, 57, 58), only Legend #57 directly addresses the theft of pine nuts. A century ago, Bill Cornbread told Robert Lowie (Reference Lowie1939:338–339) that Paiute people to the east stole local Wá∙šiw pine nuts. Similar thefts are independently described in Numic oral histories (including #8, 19, 41, and 39). These oral histories are further supported by Western science (Figure 4; Supplementary Material 6), which documents the first arrival of pinyon pine in Wá∙šiw territory at least several centuries (perhaps a full millennium) before pinyon arrived in Paiute territory (around the Carson Sink and Walker Lake).

Beyond this single story of pine-nut theft, Wá∙šiw oral history instead expands on the evolution of local pinyon ecosystems within their homeland (pinpointed by Western science [Figure 4] to be ca. 2150–1370 BP). In Legend #52, a large flightless black and white bird walked with other animal people along icy mountaintops carrying a pouch of pine nuts to share with his Wá∙šiw friends. A parallel narrative (#58) tells of crows flying into the Wá∙šiw homeland with beaks full of pine nuts; when blocked by the massive ice barrier, Chickenhawk broke through the ice so Crow could plant pine nuts among the Wá∙šiw.

Narratives #47, 49, and 50 tell how Wolf preserved the Carson Valley as an “Eden” so that the Wá∙šiw people could keep practicing the gumsabáy (fandango celebrations). Although Coyote upset the balance by making game scarce and torching the pinyon woodland, Wolf scattered pine nuts that sprang up magically. Knowing that the hungry and weakened Wá∙šiw could not reach the pine nuts, Wolf lopped off the pinyon treetops to create the so-called pygmy conifers (Charlet Reference Charlet1996), from which they could easily harvest nuts and cones.

Herman Fillmore (coauthor, Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California) distinguishes the Numic theft narratives elaborated above from mainstream Wá∙šiw oral histories that underscore biogeography and shifting ecological balances within the pinyon homeland. Rather than painting the huge swath of glacial ice as a barrier preventing pine-nut theft, for instance, Wá∙šiw narratives acknowledge that inhospitable conditions can sometimes make food scarce. To Fillmore, the uniqueness in Wá∙šiw oral history lies in the passing down of tribal perspectives on people, land, animals, and pine nuts—conveying causes and effects within a deep sense of place. This perspective reprises Fixico’s (Reference Fixico2025:17) sense of “story” as traditional knowledge that transcends time and involves new listeners from the next generations.

Why Do Theft of Pine Nuts Oral Histories Encode Shifting Animal Biodiversity?

Indigenous Perspectives on Animal People

Theft of Pine Nuts oral histories go back to time immemorial, when animal people—such as Wolf, Coyote, Rabbit, Bear, and Mountain Lion—could talk and behave as human beings, each with well-delineated individual personalities. Animal people could also accomplish supernatural feats that set moral standards and guidelines for human behavior (Fowler and Fowler Reference Fowler and Fowler (editors)1971:241; Hultkrantz Reference Hultkrantz, d’Azevedo and Sturtevant1986:637–638; Johnson Reference Johnson1975:12; Kelly Reference Kelly1932:137; Lowie Reference Lowie1924:228, 229; Shimkin Reference Shimkin1947:329; Smith Reference Smith1940:119, 193; Steward Reference Steward1943:257; Zedeño et al. Reference Zedeño, Pickering and Lanoë2021:309).

Western Science Perspectives on Animal Biodiversity

Theft of Pine Nuts oral histories also encode the past biodiversity of Western science. Some TPN narratives have specific geographic indicators that some modern Great Basin taxa had different distributions and habitats in the past (as detailed in Millar et al. Reference Millar, Thomas, Benner, Cossette, Fillmore, Teeman and Wewa2025; see also Sutton Reference Sutton1989)—suggesting independent proxies to expand Western-science reconstructions of historic species distributions.

The TPN narratives mention 24 mammal taxa, 17 birds, and six reptiles—with Coyote, Wolf, and Mouse the most common mammals. These oral histories shed light on extirpated species (such as gray wolf and grizzly bear), taxa with different historic ranges (bighorn sheep), and species that have expanded in range (mountain lion and deer). Indigenous narratives also corroborate some specific historical locations reconstructed in Western science (including beaver in northern Sierra Nevada) and offer new geographic insights on other taxa (such as black bears near Pyramid Lake and around Death Valley).

Crow, Woodpecker, and Crane are the most mentioned birds. Twenty-seven TPN oral histories speak of a bird (usually hawk) hiding stolen pine nuts within a fresh cut inside a rotten, sore, or stinking leg; when planted, this leg cast off pinyon trees after reaching the thieves’ homeland. We see rotting legs as possibly relating to the mulching of pine nuts, which hastens their germination when planted by birds in fall.

The crow family (Corvidae) accounts for one-third of the birds in the oral histories. Considering the pivotal role of corvid birds in spreading pinyon seeds, we find it curious that none of the TPN narratives obviously reference Clark’s Nutcracker, a bird common to the pinyon woodlands and a primary pinyon-nut disperser.

Why Do Massive Ice Barriers Sometimes Thwart Pine-Nut Thieves?

Indigenous Perspectives on Ice Barriers

The most eye-catching motif in Theft of Pine Nuts is the towering wall of ice. Piudy (Legend #4: Surprise Valley Paiute) tells of the animal people who “travelled until they came to an ice blockade. It stood from sky to earth.” Billy Steve (Legend #2: Pyramid Lake) said that when “they found a blockade of ice just like these mountains; it was all ice. . . . They all stopped there; they couldn’t go across.” These ice sheets appear in the northernmost 22 of the TPN variants, largely clustered along the eastern Sierra Nevada slope (north of Mono Lake) and extending across the far northern reaches of the Great Basin.

Western-Science Perspectives on Ice Barriers

TPN oral histories leave no doubt that these “ice barriers” far transcended mere winter snow or persistent snowbanks, therefore begging another question: If such narratives potentially embody eyewitness accounts, where could Indigenous storytellers have ever seen an “ice blockade . . . sky to earth?”

Western science documents that glaciers and large permanent ice fields like this disappeared from the Great Basin a very long time ago. As we detail elsewhere (Millar et al. Reference Millar, Thomas, Benner, Cossette, Fillmore, Teeman and Wewa2025), massive ice barriers of the magnitude described in the TPN narratives vanished from the Great Basin more than 18,000 years ago (during the Late Glacial Maximum). After that, glacial advances produced only much more modest ice features.

But contemporary Western science lacks convincing evidence that humans were around in the Great Basin 18,000–21,000 years ago to observe these Late Pleistocene glaciers. Paisley Cave 5 (Oregon), the earliest well-documented human presence in the Great Basin, is dated at approximately 14,500–14,100 BP (Jenkins et al. Reference Jenkins, Davis, Stafford, Campos, Hockett, Jones and Cummings2012; see also Moreno-Mayar et al. Reference Moreno-Mayar, Vinner, de Barros Damgaard, Fuente, Chan, Spence and Allentoft2018; Willerslev and Meltzer Reference Willerslev and Meltzer2021). By this time frame, people arrived too late to witness Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) glaciation (Hittman Reference Hittman2013:210–211). More ancient possibilities exist (e.g., Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Bustos, Pigati, Springer, Urban, Holliday and Reynolds2021; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Madsen, Sisson, Becerra-Valdivia, Higham, Stueber and Bean2022; Rowe et al. Reference Rowe, Stafford, Fisher, Enghild, Quigg, Ketcham, Sagebiel, Hanna and Colbert2022) and will doubtless multiply in the future. But today’s archaeology suggests that Great Basin people could only have witnessed the smaller remnants of LGM deglaciation (completed by ∼15,000 years ago). Alternately, perhaps these oral histories carried over from earlier times in North American Arctic environments. Either way, this would require oral transmission persisting for more than 15,000 years (Angelbeck et al. Reference Angelbeck, Springer, Jones, Williams-Jones and Wilson2024; Fiedel Reference Fiedel, Walker and Driskell2007; Ruuska Reference Ruuska2026). Although such estimates exceed many approximations of time depth for Indigenous oral history, at a minimum, they provide testable hypotheses for the future.

Conclusions

Western science has long debated the historical validity of orally conveyed traditions, with tensions persisting among advocates and detractors on both sides (Dorson Reference Dorson1963; Mason Reference Mason2006; McGhee Reference McGhee2008). We align with Indigenous scholars who advocate oral history and tribal input as a way of generating more powerful insights into deep history of the Great Basin (Blackhawk Reference Blackhawk2006; Brewster Reference Brewster2003; Crum Reference Crum1994; Forbes Reference Forbes1967; Teeman Reference Teeman2024). Although still a minority voice, an increasing number of anthropologists are similarly promoting the inclusion of oral history into archaeological perspectives (e.g., Carroll et al. Reference Carroll, Zedeño and Stoffle2004; Connolly et al. Reference Connolly, Ruiz, Jenkins and Deur2015; Hittman Reference Hittman2013:207; Ives Reference Ives, Johnson and Arlidge2024; Myers Reference Myers2001; Stoffle and Zedeño Reference Stoffle and Zedeño2001; Stoffle et al. Reference Stoffle, Van Vlack, O’Meara, Arnold and Cornelius2021, Reference Stoffle, Arnold, van Vlack, Johnson and Arlidge2024; Sutton Reference Sutton1987, Reference Sutton1989, Reference Sutton1993; Thomas Reference Thomas2000, Reference Thomas2019, Reference Thomas2020, Reference Thomas2024; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Cossette, Benner, Camp and Robinson2025).

Sometimes, for instance, Western science has relied on Indigenous oral history to describe singular and catastrophic geologic events (such as megathrust earthquakes, eruptions, and tsunamis). A Wá∙šiw creation story describes a massive Late Pleistocene tsunami in ancestral Lake Tahoe (California) that brought water high on the Carson Range (the lake’s eastern flank) and destroyed villages on its east shore (Fillmore Reference Fillmore2017). This tsunami is well established geologically as dating to 12,000–21,000 years ago (Moore et al. Reference Moore, Schweickert and Kitts2014). Similarly, Klamath oral tradition recalls the violent eruption of Mt. Mazama (Oregon) approximately 7,700 years ago. Details of these eyewitness accounts have been confirmed by modern geological studies (Barber and Barber Reference Barber and Barber2004), and they are accepted today by many archaeologists working in the area (e.g., Budhwa Reference Budhwa, Mackenthun and Mucher2021; Connolly et al. Reference Connolly, Ruiz, Jenkins and Deur2015). Here, we expand these more measured applications by seeking out elements encoded in oral histories regarding pinyon-pine ecology and reflecting their long-term significance and survivance among Indigenous Great Basin communities.

Four key findings emerge from the 61 Theft of Pine Nuts variants, each offering unique and fresh approaches to assess long-term ecological dynamics.

1. TPN oral histories and Western scientific research overwhelmingly document the deep and long-lasting significance of pinyon pine as a driving force in Indigenous Great Basin lifeways.

2. Multiple TPN narratives pinpoint pine-nut homelands to the storyteller’s north, far beyond where pinyon trees grow today. This Indigenous oral history supports the Thomas and Millar (Reference Thomas and Millar2024) hypothesis of high-latitude Late Pleistocene / Early Holocene refugia in some localities not previously considered by Western science.

3. TPN oral histories extend the distribution of multiple Great Basin taxa before Euro-American contact.

4. The striking presence of massive ice barriers in Theft of Pine Nuts narratives must closely correlate with Late Pleistocene (LGM) glaciers and ice caps; subsequent advances (∼13,000–11,700 years ago) lacked adequate ice to fit such descriptions. Although sense of place is vastly more important than linear time in Indigenous oral histories, TPN legends suggest the possibility of ice barrier narratives 15,000 years ago.

We join an increasing number of Indigenous scholars, environmental scientists, ethnographers, and archaeologists in promoting the potential of oral history as a fresh way to test Western scientific hypotheses and expand knowledge broadly. This outlook expands on previous perspectives that employed Indigenous knowledge merely as a “control” on Western-scientific hypothesis testing (e.g., Franks et al. Reference Franks, Nunn and McCallum2024).

Believing that these insights warrant further paleoenvironmental investigation, Millar has already embarked on multiple field surveys along the northern tier of the Great Basin in search of previously unrecognized high-latitude pinyon refugia. She is attempting to locate current or past occurrence of pinyon by consulting unpublished herbarium records, seeking out unrecorded midden sites, reanalyzing existing pollen data for pinyon-type pollen, and considering additional proxies (including the current distribution of Pinyon Jays and starch analyses on grinding stones for evidence of pine nuts). Informed by the TPN oral histories, these field and laboratory studies are ongoing. We encourage others to do the same.

In short, we argue that so-called myths can potentially convey significant historical landmarks if used judiciously and in conjunction with independent forms of corroboration (Parks Reference Parks1985:57). This belief reflects Roger Echo-Hawk’s (Reference Echo-Hawk2000:285) sage counsel that “written words and spoken words need not compete for authority in academia, nor should the archaeological record be viewed as the antithesis of oral records. Peaceful coexistence and mutual interdependence offer more useful paradigms for these ‘ways of knowing.’”

Acknowledgments

We thank Catherine Fowler for her input and for generously providing us with previously unpublished legends of Theft of Pine Nuts. We also gratefully acknowledge the thoughtful reviews by Shelly Davis-King, Glenn Farris, Michael Hittman, Richard Hughes, Kent Lightfoot, Katelyn McDonough, David Rhode, Geoffrey Smith, Mark Q. Sutton, Maria Nieves Zedeño, and three anonymous reviewers. We also thank Diana Rosenthal Roberson, Lorann S.A. Pendleton, Anna Semon, Jenn Steffy, and Caitria O’Shaughnessy for helping prepare the manuscript. One of us (DHT) further acknowledges the late Vine Deloria Jr. (1933–2005), who jump-started this whole project. In his foreword to Skull Wars (Thomas Reference Thomas2000), Vine transcended his “almost incandescent rage” after reading my unvarnished history of archaeological-Indigenous interactions to argue that we must “build on the positive things now happening and work for a more cooperative and productive future” (Deloria Reference Deloria2000:xviii). Over the next five years, Deloria and Thomas planned a series of targeted archaeological digs in the (perhaps naïve) belief that the inevitable truths embedded in Native American oral history would eventually get the attention of (at least some) twenty-first-century archaeologists. This article is a step in that direction and, had he lived, Vine would have joined us as coauthor. We hope our effort serves his memory proud.

Funding Statement

This research was funded in part by the North American Archaeology Fund at the American Museum of Natural History.

Data Availability Statement

All data used as the basis for this analysis are included in Millar et alia (Reference Millar, Thomas, Benner, Cossette, Fillmore, Teeman and Wewa2025) and the Supplementary Material section.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2025.10128.

Supplementary Material 1. The Survivance Concept (text).

Supplementary Material 2. Transcribing Great Basin Oral History (table).

Supplementary Material 3. Recording Indigenous Oral History in the Great Basin (text).

Supplementary Material 4. Selected Original Accounts of Theft of Pine Nuts (text).

Supplementary Material 5. Post-Colonial Indigenous Survivance in the Great Basin (text).

Supplementary Material 6. Pinyon Pine Late Pleistocene and Holocene Dates and Locations (table).