In January of 1908, Ford Madox Ford (then Hueffer) watched the tide at Winchelsea advance:

The turn of the tide! – As I write the sea is at the turn of the tide, wearily, below my windows. – Will the turn of the tide come in 1908? Will this year begin to show us English Literature registering and presenting in a great body, Modern Life? Will it begin to show us that Literature can still do for this Age what it has done for all that preceded it? Will it register and give to our time a form and an abiding shape and stamp? I wonder.1

Recorded in his New Year column for The Tribune, Ford’s reflections are interesting for what they imply about his own sense of ‘Modern Life’ and for what they suggest, in a more representative way, about the confusion which fell over intellectual London in the decade before the war – that state of limbo which follows after one Age has seemed to ebb but the next has not yet surged into view.2 At the time of Ford’s article, a Victorian tradition in terminal decline survived in the national laureate Alfred Austin, while some of its elder statesmen (Swinburne, Meredith) continued to cast their shadows over the present. And yet there were no clear signs of it being replaced, so far as Ford could see: ‘We have, of course, the three or four writers. But are they enough to form an impulse, to found a school, to turn a tide? I wonder’ (CE, p. 52). Pound remembered it as a period of muddle: one in which ‘a few of the brightest lads have a vague idea that something is a bit wrong, and no one quite knows the answer’.3 These were the ‘brightest lads’ he would later call ‘the forgotten school of 1909’ – the school where, in Pound’s masculinist version of events, les imagistes received their education.4 But they had not come together at the time of Ford’s article. ‘As a matter of fact’, Pound claimed, ‘Ford knew the answer but no one believed him’.5

But what was the answer? The mood of Ford’s passage is uncertain, from its grammar to its concluding note of inconclusion. It seems to offer little in the way of definite answers and to prefer to ask questions. In his hesitation, Ford may be coming into his own idea of how Literature might register Modern Life. Indeed, he may be on his way to certain centrally important ideas in our critical narratives about modernist literature, as we will see. For the moment, though, the general atmosphere of confusion and inertia is the thing to note, because it calls into question the language of paradigm shifts and epistemological fractures on which accounts of modernism have themselves often seemed to rest. It might remind us that the idea of ‘modernism’ – as opposed to that of the ‘modern’, say, or the ‘new’ – was not one with which many of the writers we now call ‘modernist’ were notably occupied. It might return our attention to the things these writers did talk about, and to the more provisional language in which they chose to do so. Keeping this in mind, my concern here is with ‘Modern Poetry’, as Ford’s crucial essay of 1909 is entitled.6 More specifically, it is with the ways in which Ford and others began to conceive of self-consciously modern verse forms in terms of impressionism – terms which might themselves be thought of as interestingly, even illustratively retrograde, since impressionism had by then been superannuated by newer visual forms. (It was the so-called post-impressionists whom Virginia Woolf, half-seriously, credited with changing human character ‘on or about December 1910’.7) Ford’s writings about impressionism in fiction are now widely read, but he, along with Edward Storer, T. E. Hulme and F. S. Flint – all alumnae of the Forgotten School – began in the pre-war years to use the language of impressionism to describe what a modern kind of poetry might look like, and in particular as a vehicle for the assimilation of ideas about vers libre within English poetry. One aim of the present chapter is simply to draw attention to this fact, because even if ‘impressionism’ is the common term which joins together poets who have otherwise appeared hopelessly divergent, its importance has been obscured by later concepts or movements (imagism, vorticism) of which it was formative but which reside more certainly within the ideological enclosures of modernist studies.8 A second purpose for this chapter will be to suggest that while the different kinds of impressionism described by these writers involved ways of thinking about form that are often thought to be characteristically modernist, their poetics reflect a more complex and continuous kind of literary evolution than the one implied by our conventional period boundaries. Both claims are informed by a sense that what is ‘modern’ about the forms of impressionism discussed by the pre-imagist avant-garde – at least in their account of things – is their truthfulness to certain kinds of complexity and continuity.

In December of 1909, Ford returned to the subject of his New Year article in an essay entitled ‘Modern Poetry’. In the later essay his mood has hardened, and he seems in one way to double back on himself. ‘We make a mistake’, Ford argues, ‘in looking too eagerly for the figure of the great poet’ (CA, p. 173). His doubt about the capacity of ‘English Literature’ to present in a ‘great body, Modern Life’ is spun around, so that uncertainty becomes a sign of resurgence and the absence of greatness seems salutary. ‘When we lament today that we have neither a Tennyson nor a Browning, we lament too early’, Ford suggests, because the absence of a ‘monumental’ figure ‘would only go to show that now – as should be the case – the art of poetry is in sympathy with the spirit of the age’ (p. 173). Ford’s change in tone was prompted, in part, by contemporary events. A week earlier, he had marked the deaths of Swinburne and Meredith by announcing, in the pages of the English Review, ‘The Passing of the Great Figure’.9 Having spent much of his childhood ‘nervous and trembling’ in the company of the most eminent Victorians, he felt the symbolic passing of the Great Figure as a psychological relief (p. 174). But Ford’s change in mood has also to do with a broader sense of transition and revaluation. In an age inhospitable to ‘priestcraft’, as he called it, ‘we very much doubt whether a Ruskin or a Gladstone would today find any kind of widespread dominion’ (p. 118). For the Great Figure – specifically the Great Poet – had flourished on account of his ‘priestly glamour’: ‘[h]e commanded respect [not] because he was going to give pleasure’ but because he promised ‘to solve the riddle of the universe’ (p. 174); he belonged to a time when ‘men still generalised’ and ‘the functions of life could be treated as manifestations of a Whole’ (p. 180). ‘The trouble today’, Ford felt, ‘is that [we] are beginning to realise how much there is in the world to know, and how little of all that there is, is the much that we know’ (p. 178). The rapid growth of modern science seemed to have spelled the end for ‘Great poetry – poetry with the note of greatness’, because poetry of this kind ‘would seem to demand a simplicity of outlook upon a life not very complex’ (p. 175). ‘Until all the sciences have been so crystallised by specialists that one poet may be able to take them all in, and until we have that one poet’, Ford remarked, ‘we cannot have any more poetry of the great manner’ (p. 176). The great manner demanded an attitude of self-assured omniscience which amounted to a kind of conceit, but ‘the little patches, which are all that today we can grasp, are sufficient only to make any reasonable man more humble’ (p. 180). Accordingly, ‘with all the poetry of today’, ‘we are producing, not generalisations from facts more or less sparse’ but ‘small intimate shades of personalities’; not perfect symmetry but ‘fascinating irregularities’ of rhythm (pp. 177–8). Ford would ‘confess that for us this is a matter of the profoundest satisfaction’ (p. 178), for the Great Figure – ‘the long-bearded person of wind-blown aspect’ – now seemed an ‘altogether preposterous’ anachronism (p. 175). Thus, while Ford would concede that a descent from the note of greatness might seem ‘a symptom of degeneracy’, he professed himself sanguine, preferring ‘to regard it as a portent of a new birth’ (p. 178). Where previously an absence of Great Poetry had been a cause for concern, or at least for uncertainty, there is now a sense that poetry might already be doing for the Age what it had done for all that preceded, and that the more uncertain and wavering lyrics that Ford was encountering at the time of his essay were the best signs of this.

Ford’s caricatures of the Great Figure are well known, as are some of his later stipulations for the writing of Modern Poetry, particularly those elaborated in the ‘Preface’ to his Collected Poems of 1913 (published separately in Poetry magazine under the title ‘Impressionism – Some Speculations’) and in his famous essay of 1914, published in Poetry and Drama, ‘On Impressionism’.10 To begin with, however, it is useful to trace Ford’s arguments backwards, because their origins give a vivid indication of the attraction of ‘impressionism’ as a term for describing new and irregular verse forms. We have already seen that the notion of irregularity was itself central to the aesthetics and the rhetoric of the impressionist painters.11 As Ford’s critical vocabulary (of ‘shades’, ‘patches’, ‘renderings’) might lead one to suspect, his thinking about modern literature is closely related to his thinking about contemporary art. In fact, the clearest precedent for Ford’s arguments about modern poetry is in the contrast he began to draw at the turn of the century between the impressionist painters and a specific group of Victorian Great Figures, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.12 The opposition, in which impressionism is seen as a clear-sighted ‘modern’ corrective to the nostalgic fantasies of Pre-Raphaelitism, would become a recurring motif in Ford’s criticism, serving as an emblematic antagonism in his narratives about modern art and his sense of his own maturation as an artist. But the comparison exerted a particular pressure on Ford’s thought in the early years of the century as he attempted to free his poetry from what he called ‘the powerful shadow of Pre-Raphaelism [sic]’.13 Its most pointed expression came in a book of art criticism entitled The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood: A Critical Monograph (1907), in which the French painters serve at various points as a collective benchmark against which to measure the achievements of the Brotherhood, as well as exemplars of the art of intimate shades and irregular rhythms which Ford later uses as a paradigm for contemporary verse.

The contrast is apparent almost from the first word of Ford’s study, which begins with a description of Pre-Raphaelitism as a ‘Mountain in a very French revolution of the plastic arts’ (PRB, p. 2). He credits the original trio with pre-empting this revolution – ‘Rossetti, Hunt, and Millais [strove] before all things to be themselves and to render the world as they saw it’ (p. 8) – but he also argues that they had lapsed into a banal form of genre painting, ‘a kind of innocuous daily bread’ (p. 5). Even at his most sympathetic, Ford’s concessions to the correctness of the Brotherhood’s founding impetus are outweighed by his reservations about the paintings they produced:

Pre-Raphaelism was [a] return to Nature, in that it led the Arts and followed the tide of humanity in England. And, in so far as it was possible as it were to nail Nature down to record her most permanent parts these Pre-Raphaelites succeeded very miraculously in rendering a very charming, a very tranquil, and a very secure England.

‘Charming’ suggests preciousness and a beauty which is entrancing but possibly deceptive, ‘nail down’ a violence reminiscent of the crucifixion. There is an implication that the means undoes the end: that nature is unfixable, or, when fixed, no longer natural; and that the attempt to reflect nature by fixing it fails because of the impulse to fix itself. It prompts a comparison:

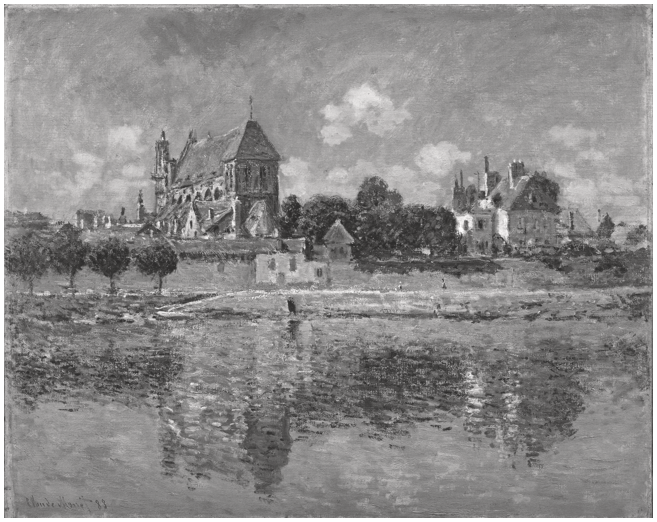

They never convey to us, as do the Impressionists, or as did the earlier English landscape painters, the sense of fleeting light and shadow. Looking at [John Everett] Millais’ nearly perfect Blind Girl, or at Mr. [William Holman] Hunt’s nearly perfect Hireling Shepherd [Figure 3.1], one is impelled to think, ‘How lasting all this is!’ One is, as it were, in the mood in which each minute seems an eternity. Nature is grasped and held with an iron hand. There is not in any of the landscapes that delicious and delicate sense of swift change, that poetry of varying moods, of varying lights, of varying shadows that gives to certain moods and certain aspects of the earth a rare and tender pathos.

Ford’s prose is thick with opposed terms which associate impressionism with vitality and Pre-Raphaelitism with a deadening airlessness.14 Ford notes that one of ‘the Impressionists’ – ‘Renoir perhaps, or Monet, it matters very little since the spirit of all was identical’ – had said that ‘every time that I commence a new picture I plunge into a river and commence to learn to swim’.15 The maxim (in fact one of Manet’s) suggests an approach that is spontaneous and particular; its result is ‘the orchestra of splashes’ that Ford saw in the thick impasto of impressionist painting. By contrast, the somewhat forbidding figure in whom the spirit of Pre-Raphaelitism is personified petrifies his subjects in the heavy gloss of his ‘prismatic enamels’ (p. 118).

Figure 3.1 William Holman Hunt, The Hireling Shepherd (1851), Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester, UK.

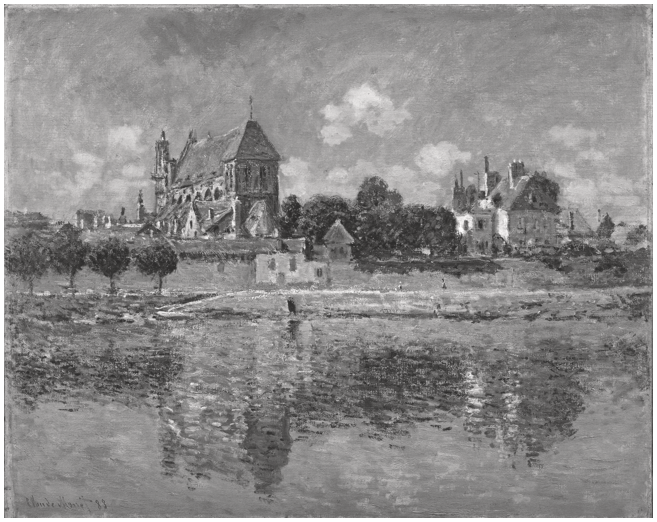

We can see the outlines of the binary that will structure Ford’s later criticism taking shape. The detail of the contrast was informed by contemporary events. Ford began writing The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood shortly after Paul Durand-Ruel’s exhibition of impressionist painting at the Grafton Galleries, which ran throughout January and February of 1905. In the book he discusses paintings on display at the Grafton and responds to specific criticisms levelled at the exhibition in the press.16 The testiest of these was authored by an eminent figure associated with the Brotherhood itself, Sir Philip Burne-Jones, who launched a broadside against ‘The Experiment of “Impressionism”’ in the March issue of The Nineteenth Century and After.17 He took particular exception to the impressionist focus on light, and to the French poet Camille Mauclair, who had mounted a defence of the French painters in his monograph The French Impressionists (1903), a translation of which was published alongside The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood as part of Duckworth’s ‘Popular Library of Modern Art’. (Ford was certainly aware of Mauclair’s book, since it is referenced in the front matter of his own study.18) Burne-Jones quotes Manet’s pronouncement that ‘The principal person in a picture is light.’19 He then excerpts from Mauclair’s study a passage about Monet which paraphrases that aphorism: ‘Light is certainly the essential personage who devours the outlines of the objects[.] One can see the vibrations of the waves of the solar spectrum, drawn by the arabesque of the spots of the seven prismatic hues juxtaposed with infinite subtlety.’20 Besides the ‘periphrastic eloquence’ of Mauclair’s prose, what Burne-Jones objects to is not so much the manner in which light is painted – though he does object to this – as the fact that ‘the new creed involves the exclusion [of] “the literary idea”’, which leaves the paintings ‘deplorably barren of incident’ and complicit in ‘an unworthy cause’.21 Ford takes up this argument in his monograph, most notably in his unfavourable comparison of Hunt’s canvases with the more evanescent ‘beauties of, say, M. Pissaro’s [sic] “Boulevarde Montmartre”, or even of Claude Monet’s “Église de Vernon”’ (PRB, p. 117). Ford refers here to one of Pissarro’s series of fourteen views depicting the Boulevard Montmartre (1897) and to one of several paintings made by Monet of the church at Vernon. The juxtaposition is prompted by Mauclair’s book, which contains reproductions of Pissarro’s Boulevard Montmartre, matinée de printemps (1897) and Monet’s Vue de l’église de Vernon (1883, Figure 3.2).22 In the text on either side of Monet’s painting, Mauclair distinguishes the Pre-Raphaelites’ allegorical portrayals of ‘religious or philosophic’ themes from Monet’s sketchy treatment of his religious subject, in which the emphasis is not on the church but on the atmospheric effects travelling across its surface.23 Ford’s encapsulation of this difference is also a juxtaposition of the arguments of Mauclair and Burne-Jones and pivots on the same quotation: ‘It was, I think, Monet who said: “The principal person in a picture is the light”: the Pre-Raphaelites had by 1849 arrived at the conclusion that the principal person in a picture was the Incident pointing a moral’ (PRB, p. 114). To Burne-Jones’s specific complaint that the impressionists had renounced the ‘literary idea’, Ford replies that the Pre-Raphaelite pursuit of the ‘Literary Ideal’ – ‘[their] doctrine that a picture must enshrine some worthy idea’ (p. 114) – had led to nature being ‘falsified’, frilled with ‘theatrical effects of light’ and symbolic accessories (p. 121). In so far as this was true, he argued, the Pre-Raphaelite painters had ‘reverted to one at least of the doctrines of the Grand Style’ and missed ‘the road along which modern art was travelling’, which was towards the sketchy notation of fugitive effects of light and haze (p. 114).

Figure 3.2 Claude Monet, Vue de l’église de Vernon (1883), Yamagata Museum of Art, Yamagata, Japan.

Two significant facts become apparent here. The first is that, as Ford was writing his book about the Pre-Raphaelites, he was not only reading about impressionism, but making it into a nonpareil in his thinking about modern art. The second is that it was through his art criticism that Ford arrived at the polarities – of the intimate against the monumental, of fleeting moods against moral certainties, of varying ‘aspects’ as opposed to a coherent ‘Whole’ – which would structure his later arguments about modern poetry.24 Indeed, in the wake of the Grafton show, the language and imagery of Ford’s art criticism bleeds into his literary essays, becoming central to his emerging sense of what a modern poetry would look like. Looking out from his window at ‘the great western-going highway’ in his essay of 1909, he sees ‘innumerable motes of life in a settled stream, in a never-ceasing stream’; ‘not so many great lives as an infinite flicker of small vitalities’ (CA, p. 185). The metaphor connects to the impressionist splashes of paint described in Ford’s monograph and also evokes a related literary form – the ‘never-ceasing stream’ being a relative of Pater’s Heraclitean flood of impressions and calling to mind Symons’s synthesis (itself indebted to Pater) of the ‘dark stream’ of the mind and the ‘human stream’ of the metropolis.25 In turn, the turbulent motion of the stream provided Ford with an emblem for a new outlook and a new prosody. Thus, in ‘Modern Poetry’, Ford remarks that ‘all [our] impressions are so fragile, so temporary, so evanescent, that the whole stream of life appears to be a procession of very little things, as if, indeed, all our modern life were a dance of midges’, but reframes this as an opportunity: ‘[for] there seems to us to be so much more of poetry in all the little lights that whirl past, in the shadows that flicker, in the tenuous and momentary reflections seen in the polish of carriage panels’ (CA, p. 186). If ‘[we] have grown personal, intimate, subjective’, as he argues in another essay of 1909, then the loss of ‘the sense of a whole, the feeling of a grand design’ would be offset by a fuller attention to the rendering of evanescent impressions.26 The breaking down of traditional forms into ‘vague rhythm[s]’ and ‘irregular lines’ might sacrifice the symmetry of a poem, but this would be compensated by that sense of intimacy and swift change Ford had found in Monet and Pissarro.27

As we will see, the question of irregular lines was a recurrent preoccupation for Ford in the years following the Durand-Ruel exhibition. But he was not alone in searching for forms that would capture the flickering and tenuous sensations of what he calls ‘modern life’, nor in drawing inspiration from the ‘poetry of varying moods’ that he associates with the impressionists in the process. As he was writing his essay on ‘Modern Poetry’, Ford was being brought into contact with a group of poets who shared his views about poetry and who had made him conscious ‘that there is a new quality, a new power of impressionism, that is open to poetry’.28 Rather than looking up at ‘two or three enormous poets like Tennyson or Rossetti, whom one suspected always of posing, of forcing the poetic note’, Ford tells us, he had made the acquaintance of ‘a whole circle of smaller, more delicate, and more exquisite beings’ (CA, p. 179).

Which circle he is referring to Ford does not specify, but one important group of poets known to him had formed in the time between his New Year article of 1908 and his 1909 essay. ‘The forgotten school’ is an inspired misnomer, evoking both fraternity and fractiousness. Even in the most basic sense, the group was bound together by disagreement, being the product of a spat in the review pages of Alfred Orage’s revamped Fabian weekly, the New Age. In January of 1909, the Poets’ Club – a group convened each month by the banker and amateur poet Henry Simpson at the United Arts Club in Mayfair – had published a Christmas anthology including poems by Margaret Sackville, Henry Newbolt, F. W. Tancred, Selwyn Image and the club’s secretary, T. E. Hulme. The book was met with disdain by F. S. Flint, the newly appointed poetry correspondent at the New Age, who panned the booklet in his February ‘Recent Verse’ column.29 He dismissed the group as a ‘dining-club and after-dinner discussion association’, remarking that ‘evening dress is, I believe, the correct uniform; and correct persons – professors, I am told! – lecture portentously to the band of happy and replete rhymesters’ – as if to imply a correlation between the members’ decorousness and their ‘pretty way of ornamenting’ poems.30 Conjuring an image of Verlaine ‘in a café hard by with other poets, conning feverishly and excitedly the mysteries of their craft’, Flint contrasted the Poets’ Club’s ‘after-dinner ratiocinations [in] suave South Audley Street’ with a two-volume anthology of French symbolist poetry, Poètes d’aujourd’hui (1900), which he called ‘the flower of thirty or more years’ conscious and ardent artistic effort [by] pioneers, iconoclasts, craftsmen, and artists who fought for their art against ridicule’.31 The symbolist escape from orthodoxy had already served as an important touchstone for Flint: in November 1908, he had called for ‘a revaluation of all poetical values’ and praised a new collection entitled Mirrors of Illusion (1907) by Edward Storer, who, having ‘drawn inspiration from the French’, had ‘fought his way out of convention’ by abandoning orthodox patterns of metre and rhyme.32 The same critical revaluation was implied by his February column, in which he announced that, compared with ‘the living beauty’ of the French vers libre, ‘the Poets’ Club is death’.33 Hulme retorted a week later in a letter to the magazine, dismissing ‘the granitic Flint’ and his credentials as an authority on French verse: ‘historically, Mr Flint is inaccurate. The founders of the modern “vers libres” movement were Kahn and Laforgue’ (not Verlaine, as Hulme wrongly felt Flint had implied).34 But the correction disguised a common conviction. In 1908, Hulme had delivered a ‘Lecture on Modern Poetry’ in which he also recommended the adoption of vers libre in English poetry, and he was impressed enough by Flint’s criticisms to contact him privately after reading his review. Together they formed a new group, which met at the Tour Eiffel café in Percy Street for the first time on 25 March 1909. According to Flint, those present at the first meeting of Hulme’s ‘Secession Club’ included Edward Storer, Florence Farr, Joseph Campbell and Francis Tancred.35 Pound was introduced at the fourth of the group’s weekly meetings (in April) a few days after the publication of Personae (1909). The meetings did not last long. ‘Hulme was ringleader’, Flint remembered, but his interest in poetry subsided by the latter part of 1910, and so the Forgotten School ‘died a lingering death at the end of its second winter’.36 As a grouping, they were ‘modern’ in the Fordian sense: tenuous, fleeting, complex. It is not easy to see them as a coherent whole – in many ways their personalities (and often their poetry) seem jarringly mismatched – but for a short period they shared a set of significant convictions, both among themselves and also, crucially, with Ford. Ford’s exact relation to the group is unclear, but what evidence exists suggests tantalising proximities. By the spring of 1909 he was friendly with Flint, whom Ford would come to think of as ‘one of the greatest men and one of the beautiful spirits of the country’.37 In July, Ford would publish parts of Flint’s debut collection, In the Net of the Stars (1909), in his newly established English Review. In January of 1910, Flint recommended Ford’s essay on ‘Modern Poetry’ in the New Age.38 Pound met Ford in March or April of 1909 – just as he was being introduced to the Thursday evenings at the Tour Eiffel – and seems to have divided his time between Percy Street and South Lodge in Kensington, where Ford had installed himself alongside Isobel Violet Hunt.39 When Hulme first encountered Ford is not known. They knew each other by 1912 at the latest, when Ford began attending Hulme’s Tuesday night salons. (Jacob Epstein found him ‘a very pontifical person’.40 So they must have met. And Ford must have pontificated.) Given Ford’s closeness to Pound and Flint, the chances seem good that he was introduced to Hulme earlier. Whether or not they had all come into contact with him by 1909, the Tour Eiffel group would certainly have known of Ford’s criticism and the English Review. Given Flint’s recommendations, it seems implausible that Ford’s writings were not discussed at the Tour Eiffel. Likewise, it seems improbable that Ford was unaware of the meetings taking place there. Indeed, the critical pronouncements of all these writers echo each other at crucial moments.

As Flint later recalled of the Forgotten School, ‘what brought the real nucleus of this group together was a dissatisfaction with English Poetry as it was then (and is still, alas!) being written’.41 We have already observed Flint’s own hostile attitude towards ‘correct’ prosody in his review of Storer’s Mirrors of Illusion, but Storer himself voices a similar frustration in an essay attached to that volume, in which he inveighs against ‘pedants [whose] lady-like and finical conception of poetry’ required classical subjects to be treated in ‘the dear old-fashioned iambic pentameter’ (MI, p. 81). Proficiency of rhythm is ‘at best, admirable as a piece of empty virtuosity’, he felt, and even then ‘there is no real pleasure to be derived from watching mountebanks and conjurers’ (p. 81). Rather than ‘strait-jacketing [poems] in rhythm and rhyme’ (p. 87), Storer would propose an ‘impressionistic’ prosody, stripped of ‘all unessential and confounding branches of literary art’ (p. 102). In his ‘Lecture’ of the following year, Hulme also took aim at a defunct poetic idiom – ‘women whimper and whine of you and I alas, and roses, roses all the way’ – and a style of ‘religious incantation’ which aimed to induce ‘a kind of hypnotic state’ (CWH, p. 51). Regular metre ‘is for the art of chanting’, he suggested (p. 54).42 The ‘new visual art’ would involve ‘recording impressions by visual images in distinct lines’; it would depend ‘not on a kind of half sleep produced, but on arresting the attention’ (p. 54). ‘We can’t escape from the spirit of our times’, Hulme argued: ‘What has found expression in painting as Impressionism will soon find expression in poetry as free verse’ (p. 53). Meanwhile, as early as 1900 or 1901, Ford – who later styled himself as the ‘doyen of Vers Libre in English Literature’ – had proposed retiring a ‘professional-poetic dialect’ which was ‘involved, pompous, and full of archaisms’ and replacing it with the more natural rhythms of a ‘spoken language [which] is direct, forcible and simple’.43 Ford had evidently begun to describe his own verse in these terms by 1909 or earlier, as a letter from Violet Hunt in June of that year indicates. ‘Are they’, she asks of his poems, ‘the thoughts that drift away off a man’s mind, like the thistle down off the fields when the winds of life blow? Just what has to come away!’, adding, ‘You won’t make the thought tight and packed. [Because] then it would be Browningesque and not Impressionist.’44 The description implies a condensation that is distinct from Browningesque compression, the distillation only of what ‘has to come away’, but also a new fidelity to the ‘drift’ of thought which is enabled by a certain kind of looseness.

Aside from the fact that impressionism serves here as a shared model for more flexible verse forms, what sticks out is the phrase vers libre (‘free verse’, or ‘verse freed’). Variable rhythms and line lengths would not seem to bear any necessary connection to impressionist painting; varieties of irregular metre had existed in Greek, Latin and English medieval verse, and it is customary also to refer to a nineteenth-century Anglophone strain of variable metre which emerges independently of the impressionist exhibitions, running from Coleridge and Emerson, through Whitman and Hopkins.45 As Hulme’s reply in the New Age indicates, however, the specific notion of vers libre had been brought to the attention of the Forgotten School by the French poet Jules Laforgue, and his friend Gustave Kahn, editor of La vogue, the journal in which the earliest examples of vers libre appeared. In particular, they were responding to Kahn’s ‘Préface sur le vers libre’ (1897), in which he describes a poetry where the line is no longer a predetermined rhythmic unit but the combined result of smaller, irregular measures (‘fractions organiques’).46 Kahn’s theories of vers libre were derived in part from the nascent science of ‘psychophysique’, to which he had been introduced by his friend Charles Henry (who had himself absorbed them from Gustav Fechner’s 1860 treatise Elemente der Psycho-Physik). The psychophysical argument that the observed nature of external phenomena is contingent on the perceiving subject supplied Kahn with an apparently empirical justification for vers libre (which he called ‘an adherence in literature to the scientific theories [of] M. Charles Henry’) as an accommodation of rhythms that were not commonly shared conventions but expressions of a unique psychological disposition.47 Psychophysics drew on the positivism of Taine and Comte and overlapped with Schopenhauer’s epistemology, and thus shared a significant intellectual heritage with impressionist aesthetics; it is unsurprising, therefore, that Kahn and Laforgue married their psychophysical justifications for vers libre to the example of impressionist painting, which offered a precedent for the shedding of ideal forms in favour of styles tailored to individual perception. One of the most famous early statements associated with vers libre appeared in Laforgue’s 1883 essay on impressionist painting, in which he puts forward the claim, ‘as illustrated by Fechner’s law’, that ‘[e]ach man is [a] kind of keyboard on which the exterior world plays in a certain way. My own keyboard is perpetually changing, and there is no other like it. All keyboards are legitimate.’48 The Fechnerian precept enables Laforgue to translate the painters’ argument against ‘The Prejudice of Traditional Line’ – their hypothesis that ‘form [is] obtained not by line but by vibration and colour’ – into a cognate argument about aural harmonies, claiming that ‘the eye knows only luminous vibration, just as the acoustic nerve knows only sonorous vibration’.49 Exploiting the ramifications of this argument for poetry, Laforgueduly suggests that while the technique of decomposing dead form into ‘living lines’ had yielded the ‘“forest voices” of Wagner’ and the ‘dancing strokes’ of Monet and Pissarro, it had been approached only haphazardly by ‘certain of our poets’ and was yet to be ‘systematically’ applied in verse.50 When Laforgue duly published his own vers libre experiments in La vogue in 1886, Kahn would defend the poems with an identical frame of reference, claiming that vers libre was the equivalent of ‘the multitonality of Wagner and the latest techniques of the Impressionists’, as if to identify a panaesthetic tendency to decompose which, in verse, expressed itself in lines that were complex, wavering, polytonic.51 In his ‘Préface’, Kahn suggests again that the Parnassian poets lived in a world in which ‘impressionism had barely been born’ and which ‘kept them accustomed to strictly delimited contours, carved out, almost sculpted’.52 For both Kahn and Laforgue, ideas of personality, inwardness, flux – the notion of the ever-streaming, ‘perpetually changing’ self – were touchstones for a new prosody that would elude the strict delimitations of regular metre, and which found a visual parallel in the ‘vibration and colour’ of impressionist painting. The central thrust of their argument is that such a prosody would be a rhythmical expression of the poet’s unique temperament under the varying pressures of circumstance. Unshackled from the constraints of formal symmetry, it would reflect the vibrancy and flux of experience itself.

Variations of this argument became enormously influential in the early decades of the twentieth century, just as vers libre would be one of the dominant terms by which modernist verse was both defined and denigrated. Indeed, the idea that a poem might be ‘free’ would become the compelling stylistic issue for poets not just of the 1910s and 1920s, but of the twentieth century as a whole. It is not my purpose to add to the vast body of scholarship already devoted to modernist arguments over vers libre, nor to comment on the validity of the modernist dismissal of regular metre on historical grounds.53 I would like, however, to draw attention to the foundational role played by Ford and the poets of the Forgotten School in assimilating the idea of vers libre within English poetry. And I would also like to suggest that, as it had been in France, the language of impressionism was instrumental in this process. In some instances this will be a case of direct imitation of the French poets; in others, the connection between impressionism and vers libre will be arrived at more obliquely. As their exchange in the New Age indicates, Kahn’s ‘Préface’ was not only known to Flint and Hulme by 1909 but also forming their views about modern poetry.54 Kahn is also referenced at various moments in Storer’s criticism, including in the essay appended to Mirrors of Illusion. And Ford, too, will often describe vers libre as a form of impressionism, though he does not mention Kahn or Laforgue specifically.55 For all, impressionist style provides a template for the decomposition of the pentameter line. Collectively, their writings about vers libre mark an important early stage of the assimilation of that idea within English poetry. They also indicate how a conception of prosody that eventually became synonymous with modernist poetry was defined through analogies with a nineteenth-century aesthetics to which modernist rhetoric was often hostile.

We have already seen that the broad strokes of Ford’s conception of modern poetry have their roots in the art criticism he wrote following the Grafton show.56 Ford’s more specific arguments about vers libre were accelerated by his comparisons of the impressionists and the Pre-Raphaelites, so that the contrast we observe in the art criticism begins also to sustain an argument about variable metre. The opposition is there in ‘Modern Poetry’, in its juxtaposition of ‘irregular lines’ against ‘the clarion note’ of the Great Figure (CA, p. 177). It is there, too, in his 1913 essay on impressionism and poetry, in which he wonders if there is ‘something about the mere framing of verse, the mere sound of it in the ear’ that obstructs ‘the faithful rendering of the received impression’, throwing its practitioner ‘into an artificial frame of mind’.57 Perhaps its clearest expression comes in a ‘Lecture on Vers Libre’ which Ford delivered in the 1920s, in which he remembered having ‘to listen to numbers of people like the Rossettis and Browning and Tennyson reading verse aloud’ (CWF, p. 156). ‘They held their heads at unnatural angles’, he recalled, chanting ‘words no one would ever use, to endless monotonous, polysyllabic, unchanging rhythms, in which rhymes went unmeaningly by like the telegraph posts, every fifty yards, of a railway journey’ (p. 156). As in Hunt’s letter, but in the inverse way, form correlates with a frame of mind, so that metrical monotony is felt to produce (or to be produced by) an unnatural way of thinking. By contrast, the sort of poem Ford remembered wanting to write ‘would be like the quiet talking of someone walking along a path behind someone he loved very much – quiet, rather desultory talking, going on, stopping, with long pauses, as the quiet mind works’ (p. 156). Presumably Hunt is recalling this sort of conversation when she asks if she should describe the loose, unpacked poems she had received from Ford as ‘Impressionist’. And certainly Ford’s early advocations of vers libre were articulated using metaphors which originate in his art criticism. In his 1914 review of the first imagist anthology, for example, Ford sets up an analogy between the turbulence of the stream and the line of vers libre as a wave emanating from within the poet. He suggests that ‘the rhythm of your utterances [is] characteristic [of] your mood at the time’; it has ‘an effect like that of a sea with certain wave-lengths going on and on and on. They may be long rollers, or they may be a short and choppy sea with every seventh sentence a large wave’ (CE, p. 157). The importance of vers libre lay in its faithfulness to this variability: ‘the justification for vers libre is [that] it allows a freer play for self-expression’; ‘in its unit [it is] an expression of the author’s brain-wave’ (p. 153).

As we have seen, this figure emerges in Ford’s essays following the Grafton show. The language of ‘brain-waves’ and the notion that rhythm is an expression of a unique temperament are also strikingly close to the psychophysical arguments of Kahn and Laforgue, of which Ford was certainly aware by the time he was writing ‘Modern Poetry’ – if not through his own reading then through Mauclair, whom Ford was commissioning for the English Review by 1908 and who was a vigorous proponent of Kahn’s arguments about metre.58 In turn, vers libre would be Ford’s dominant mode in the poems he wrote during the First World War – particularly his long poem ‘On Heaven’ (‘the best poem yet written in the “twentieth-century fashion”’ in Pound’s estimation) – in the verse drama Mister Bosphorus and the Muses (1923) and in his late masterpiece ‘Buckshee’ (1932).59 By 1914, Ford had become the major living spokesperson for the idea of literary impressionism. As his letter to Hunt would suggest, however, Ford had been employing the language of impressionism to describe his experiments with irregular rhythm for some time before this; and while the earliest of these experiments do not result in fully fledged vers libre, they do show Ford’s arguments about naturalness of utterance coming audibly to bear on his poetry, often in combination with conspicuously impressionistic visual effects.

One example would be the extraordinary opening poem to Ford’s 1910 collection Songs from London, a three-part dramatic monologue entitled ‘Views’ which reads like an impressionist rewriting of Browning’s ‘Two in the Campagna’ (1855). It begins by pushing the pentameter towards irregular and prose-like rhythms which catch the rhythms of thought, ‘going on, stopping, with long pauses, as the quiet mind works’:

It continues in increasingly fragmented paragraphs of blank verse, the first of which describes several different kinds of view:

At this early stage in Ford’s interest in irregular metre, the pentameter remains relatively intact; yet even here its outlines waver in ways that indicate that interest taking shape. The rhythms of the poem – rhythm being what Leighton calls the ‘ligament of poetry’, something ‘internal, variable, affected by subject matter and feeling [which] cuts across metrical regularity’ – halt and surge with the thoughts they convey, breaking up under the pressure of curiosity, dissolving into elliptical haze, then erupting through three vivid impressions of atmosphere and light.60 A year earlier, Ford had spoken of a poetry of intimate shades and irregular rhythms as a form of degeneracy. Not only are the ‘Views’ sustained by the poem’s rhythms views of decadence in a literal sense; they also compose a verse portrait of the cell of the self (the poem’s motto is ‘I do not know’) and a sort of ekphrasis, as though the poem were describing an impressionist canvas of Rome rather than the city itself. Indeed, the speaker’s evocation of the Roman skyline employs a vocabulary of refracted light and soft-focus which, in its references to ‘prism hues’ and tremulous outlines, precisely echoes the quotation from Mauclair’s study which Burne-Jones had singled out for criticism. Moreover, the poem’s plurality of views, both temporal and spatial, parallels those of the impressionist series to which Ford refers in his monograph on the Pre-Raphaelites. At the levels of imagery and line, in other words, there is a variability which shows the arguments about modern poetry that Ford was developing after the Grafton show leaving a definite imprint on his verse.

In the years following the publication of Songs from London, this imprint would deepen, yielding Ford’s first properly free verse poems. Effects of mist and ‘still grey light’ (CP, p. 33) are also central to ‘The Starling’, the vers libre poem which opens Ford’s 1911 collection High Germany, and which gives voice, like ‘Views’, to the uncertain reflections of an isolated speaker – often in language which recalls Ford’s writings about impressionist art and the psychology of vers libre. The markedly irregular and variably rhymed lines of the poem’s first stanza have ‘an effect like that of a sea with certain wave-lengths’, and are drawn to the same simile:

These are indeed ‘the thoughts that drift away off a man’s mind, like the thistle down off the fields when the winds of life blow’ (the correlation between Hunt’s phraseology, the speaker’s situation and his desultory manner is uncannily exact), and the drift of the speaker’s perceptions is reflected in the poem’s fluctuating lineation, which measures the irregular breaks of what Ford termed the ‘brain-wave’. A version of the metaphor informs the imagery of the poem, as an implicit correspondence between the ebb and flow of the speaker’s thoughts and the starlings’ surf-flung ‘orchestras of song’ – an image which amalgamates Hunt’s description with Ford’s ‘orchestra of splashes’ – becomes more pronounced in the poem’s third stanza, where the speaker listens to a lone starling ‘in soliloquy’:

The lines present a familiar analogy between birdsong and poetic utterance, suggesting an affinity between the changefulness of the starling’s song, which mimics the birds around it, and the thoughts and rhythms of the poem’s speaking voice, which both concern and exemplify the changefulness of the self in altering circumstances. Yet in registering the wavering movement of the quiet mind working, the lines also extend the metrical irregularity of the opening stanza in a way that marks, at the level of prosody, a moment of significant departure. They show Ford’s experiments with vers libre coming into a new phase of accomplishment, as that sense of intimacy and swift change he had admired in his art criticism began to be realised in the loosened forms of his poetry.

As Ford acknowledged, a certain kind of looseness distinguished his poems from the lyrics of the younger poets with whom he associated before the war (‘I write usually rather longer poems’; CWF, p. 162). In another sense, however, a shared interest in the looseness denoted by vers libre had meant that at ‘a given moment – in 1913–14 – I found myself, as a poet, aligned [with] a certain group of young men in England and France’.61 Indeed, there are striking continuities between his own thinking about free verse and that of the poets of the Forgotten School. Storer had made the argument against metrical regularity in his essay of 1907. ‘Form’, he felt, ‘should take its shape from the vital, inherent necessities of the matter, not be, as it were, a kind of rigid mould’:

There is no absolute virtue in iambic pentameters as such[.] There is no immediate virtue in rhythm or rhyme even. [Judged] by themselves, they are monstrosities of childish virtuosity and needless iteration. Indeed, rhythm and rhyme are often destructive of thought, lulling the mind into a drowsy kind of stupor with their everlasting, regular cadences and stiff, mechanical lilts.

The phraseology here is notably similar to Ford’s, just as the arguments of both pivot on a sense that ‘everlasting, regular cadences’ and ‘stiff, mechanical’ accents sap life from the thoughts they convey. Like Ford, Storer acknowledged an older English tradition of challenges to regular metre (his examples are Keats, Coleridge, Dobell); but like Ford, and with the same visual comparison, he also felt that the redundancy of certain traditional poetic forms had been thrown into stark relief by his historical moment. ‘Now-a-days’, he remarked, ‘all we can hope to do is to picture imperfectly one tiny little portion of [existence]. This is really specialisation, or what may be called separatism in the highest forms of art, and is the logical outcome of impressionism’ (MI, p. 82). ‘Judged in the light of such a criterion’, the ornate symmetries of ‘such difficult and precious forms as the ballade the triolet, the villanelle’ seemed to Storer ‘a species of gallantry more [than] serious art’; the heirlooms of ‘elegant dilettante French and Italian gentlemen’ rather than forms which bore any ‘vital, inherent’ relation to the experiences they were now being employed to describe (pp. 85, 107–8).

Casting about for a solution, Storer found himself drawn initially (and somewhat contradictorily) to the art of the early Renaissance:

One cannot help seeing in the pictures of the early Italian and Dutch artists a wonderful naïveté, and an almost childish unconsciousness of what terrible and vital thing they were playing with in the supreme and exquisite ease with which they painted their master-pieces. Now-a-days, we have plenty of the self-consciousness of art, without, perhaps, so fine an endowment of corresponding creative vitality and force.

The nearest contemporary approximations to the unbridled creative vitality of the primitive painters were, he felt, to be found in recent French painting. Like Hulme and Pound, Storer would come to dislike impressionism’s ‘dreamy-creamy’ mistiness, but at the time when he was composing Mirrors of Illusion it served as a vital model.62 For ‘Impressionism’, Storer argues, ‘has shown us a technique which seeks apparently to belittle itself in order that there might be more room for the art itself’ (p. 101).63 The definition is idiosyncratic, but the notion of impressionism as a form of ascesis provided Storer with a template for a poetry that is distinctly minimalist and ‘non-materialistic’ (p. 85). At descriptive and prosodic levels, he argues, ‘rigorous exactitude’ carries with it ‘the musty smell of age and pedantry’ (p. 95). Refinement and concision are enlivening because they reduce the friction imposed by form on the effervescence of the soul, which ‘is (metaphysically) a centrifugal, infectious force, seeking to escape its prescribed sphere’ (p. 84), but whose expression is stymied by ‘colossal self-imposed difficulties and constrictions’ (p. 107). In an attempt to breathe into verse the vitality and force he associated with the French painters, Storer would propose the elimination not just of narrative but also of the straitjackets of regular rhythm and rhyme.

The closest precedent in English for the ‘limpid and amorphous’ metre prescribed by Storer’s essay was the unrhymed pentameter line, but he suggests that this form might be made still more pliable: ‘If blank verse [is] cut up and spaced, so that the lines are not always of equal length, but rise and fall with the swell of thought and imagery, a still more plastic and natural form is obtained even than blank verse of unfailingly regular lines’ (p. 109). The metaphor here is identical to Ford’s, implying the same organic relationship between line and thought and the same conception of thought itself as something fundamentally fluent and irregular. It is suggestive that Storer is well informed of contemporary incarnations of this sort of verse, of which he remarks, ‘this is, of course, only the vers libre, supposed to be the invention of M. Gustave Kahn, and since then, adopted by French poets like Verhaeren, Vielé-Griffin, Henri de Regnier, Cte Robert de Montesquiou, etc.’ (p. 110). More significant is the definition of ‘good poetry’ which results from Storer’s alignment of vers libre with the ‘elusive enchantments’ of impressionist art (p. 112). Such a poetry, he says, would ‘be made up of scattered lines, which are pictures, descriptions or suggestions of something at present incapable of accurate identification’, like ‘stray notes torn from the burning page of some wonderfully beautiful symphony’ (pp. 102, 105).

In its emphasis on evocative fragments and ‘scattered’ or irregular lines, the definition is not only Storer’s most eloquent attempt to describe a free verse style that would express the ‘swell of thought’, but also a vivid articulation of the poetic possibilities suggested by ‘the bridge of impressionism’ (p. 85). It amounts to both a curiously exact description of the manner of much early modernist poetry and a kind of self-endorsement, since Storer had himself experimented with such scattered lines and resonant images in Mirrors of Illusion. Some are cast adrift within longer poems, as in the following vers libre fragment from ‘Hellebore and Henbane’, which shapes itself to the winding route of the stream:

Others are note-like in a more literal sense, as in ‘Street Magic’, a poem comprised of a single sentence broken across four unevenly arranged, irregularly trimetric lines:

But perhaps the most interesting example of the sort of stray note Storer describes in his essay is a short poem entitled ‘Image’, which is attached as a kind of epigraph to Mirrors of Illusion. It is a compound metaphor sustained over three unrhymed, irregular lines, which are cut up and spaced to follow the swell of the imagery they convey – imagery which, by contrast with its manner of arrangement, is notably conventional:

Like many other pieces from the collection, the poem falls back upon a diction of forsakenness, faintness, loveliness – and so on – associated with a prominent tradition of nineteenth-century verse (that of Keats, Swinburne, Rossetti). Yet the radical compaction and prosodic variation of Storer’s ‘Image’ is extraordinarily prescient, as its title might lead one to expect. Indeed, it was on the basis of such poems that Flint would later describe Mirrors of Illusion as ‘the first book of “Imagist” poems’.64

Storer is not now widely read, but Mirrors of Illusion was a minor revelation for the poets of the Tour Eiffel, where, as Flint remembered, ‘[t]here was also a lot of talk and practice among us, Storer leading it chiefly, of what we called the Image’.65 Flint was the member of the group on whom Storer made the strongest impression and who first recognised the significance of his emphasis on metrical flexibility and self-expression. In turn, vers libre became a central component of both Flint’s poetry and his efforts to introduce French verse to an English readership, just as his conception of vers libre would be coloured by the visual analogies through which he was introduced to that idea by Storer and the French poets. In his New Age column of December of 1909, Flint remembered his excitement on encountering Storer’s descriptions of ‘impressionistic’ verse in Mirrors of Illusion: ‘Mr Storer was feeling his way to a poetry that should be [stripped] of all the trappings of argument and description’, one that approached ‘a form of expression, like the Japanese, in which an image is the resonant heart of an exquisite moment’.66 The remark puts Flint and Storer in touch with haiku and the wider phenomenon of Japonisme, for which impressionist art had been partly responsible and which had become embedded in the language surrounding the idea of impressionist literature. In his Studies in Seven Arts (1906), for example, Arthur Symons had compared the ‘simplified drawing’ of Degas, Whistler and Rodin to ‘the Japanese’, finding in their mutual sparsity a paradigm for a poetry in which ‘description is banished that beautiful things may be evoked’ and ‘the regular beat of verse is broken in order that words may fly, upon subtler wings’.67 Flint admired Symons and collaborated with him in translating the works of Émile Verhaeren. It seems significant, therefore, that a year after the publication of Symons’s Studies, Flint wrote a review of an English selection of haiku for the New Age in which he also proposed a new lyric style inspired by the Japanese form and vers libre: ‘The day of the lengthy poem is over. To the poet who can catch and render, like the Japanese, the brief fragments of his soul’s music, the future lies open.’68

Flint’s comparisons of the haiku to Storer’s verse in his 1909 review indicate that he is defining a new, compact kind of lyric in direct response to specific interpretations of impressionism. The language of his critical analogies also suggests an awareness of the conceptual origins of vers libre. The phrase ‘soul’s music’, in particular, connects his argument back to the psychophysical theories of Kahn and Laforgue, recalling Laforgue’s descriptions of the individual’s internal keyboard in his essay about impressionist painting. This resonance is heightened by the remark which follows, in which Flint employs a cognate image to express hostility towards received forms, particularly the iambic line: ‘A poet should listen to the individual rhythm within him before he turns, if ever, to the accepted form. He should not be content to grind an iambic barrel-organ.’69 Storer had been dismissive of the claims made for Kahn – ‘we were using vers libre in England without making any fuss about it, long before it rose to the eminence of a movement in France’ (MI, p. 110) – and Flint will also acknowledge an English tradition of variable prosody. In his review of Storer’s poems he rejects ‘mechanical rhythm’ in favour of ‘vers libre [or] verse phrased according to the flow of the emotion’, before quoting examples of the latter from Keats and Francis Thompson.70 As the phrase vers libre indicates, however, the real stimulus for Flint’s own criticism was recent French verse – ‘[our] poets once went to France with disastrous results, but there is much, I think, to be learned there now’ – just as his borrowings from the French introduce to his conception of ‘the flow of emotion’ a set of arguments and assumptions derived from comparisons with impressionist art.71 This is perhaps most apparent in a long review, written in July of 1909, of Paul Delior’s Remy de Gourmont et son oeuvre (published earlier that year). Flint praises the ‘strange musicality’ of de Gourmont’s poems and implicitly aligns them with the idea of vers libre (‘M. de Gourmont is a liberator’).72 He also quotes Delior’s analogy between the sprayed taches of impressionist painting – their ‘rich prismatic decomposition’, as Laforgue put it in his version of the comparison – and de Gourmont’s ‘supple’ rhythms, which convey ‘an infinity of souls [passing] through all the shades in which the day discomposes its light’.73 In Delior’s usage, as in Kahn and Laforgue’s, the analogy figures the self not as a clearly delineated figure, but as a many-hued spectrum whose complexion is constantly altering. It suggests a subjectivity that is variable, contingent, mirage-like. In turn, this idea of the self justifies the decomposition of the clearly defined poetic line into diffuse patterns of rhythm which fluctuate with the emotion they convey. This argument carries over into Flint’s praise for de Gourmont’s poems, which suggests the revivification of a lyric self parched by metrical convention:

They are veritable ambrosia and nectar, and reading them the dry blood of the mind becomes ichor, and one trembles with the penetrating intoxication of novelty. [It] is impossible to pass through these books without feeling that new eyes and a new understanding are being given to one; [fresh] with the dew of a new morning the earth again awaits the re-born artist.74

The overheated prose disguises an important continuity between Flint’s thinking about metrical flexibility and the arguments of the French verlibristes, as well as Ford and Storer. In his New Age essays of 1908 and 1909 in particular, vers libre is said to be a vitalising form – or an enlivening flirtation with formlessness – in which the flow of thought is allowed to carve out a path of its own rather than being broken up into uniform metrical blocks. Both the blurring of the clearly defined line into irregular patterns of rhythm and the conception of thought that these rhythms convey have a precedent in impressionist aesthetics.

Claims for Flint’s significance in histories of twentieth-century literature have traditionally been made on the basis of his translations and his criticism, but his poems represent important early explorations of the metrical freedom described in his essays and articles. This is particularly evident in those lyrics which self-reflexively address the prosodic license sponsored by vers libre itself. ‘Palinode’ was published in the New Age in 1908, shortly before Flint reviewed Storer’s collection. ‘I have grown tired of the old measures wherein I beat my song’, its speaker laments in syllabically bloated (‘broad-browed’) lines of irregular but highly rhythmical metre:

‘Enchanted’, from cantare, associates ‘chanting’ and ‘lies’ (the same association is made in Hulme’s ‘Lecture’ and Ford’s writings about vers libre). The poet’s song is said to be unmoored from the untruths of the ‘old measures’ and set in time to a more expansive swell. The metaphor parallels that which we find in the essays of Ford and Storer and seems to imply not only the breakage of an old form but also the immolation of a former identity – a twofold rupture which clears the way for twinned renewals of rhythm and self.

A year after he published ‘Palinode’, just as the Tour Eiffel meetings were getting into full swing, Flint published In the Net of the Stars. In the introductory note, he describes a formal flexibility that he suggests will be exemplified by the poems which follow: ‘I have, as the mood dictated, filled a form or created one. [In] all, I have followed my ear and my heart.’76 Indeed, the poems describe themselves in terms that suggest both a project of poetic self-definition and a corresponding programme of metrical enlargement. The approach yields heterogenous lines and patterns of rhyme which, in ‘Monody’ for example, bleed across stanzas:

Like Storer, Flint falls back on a conventional set of images; yet the speaker describes an organic power over shape which the poem itself exemplifies (even if this power of expression conveys a sense of powerlessness and loss). He does so, moreover, in terms of the lunar and tidal, implying flow and a symbiotic relation between the celestial and terrestrial. The significance of this relationship becomes apparent in the more upbeat verse ‘Foreword’ to the third section of the collection, which recycles imagery from the earlier parts of the book to establish correspondences between the liquid unity of the consciousness it delineates and the fluency of the forms which body it forth:

Splashed rhymes – rhymes that leak from terminal positions into the bodies of stanzas – twine and intertwine in a variable but discernibly ‘rhythmic’ pattern, fluidity and organicism being themselves intrinsic to the metaphoric range of the poem, in which the ripened fruits of the interior and self-enclosed are transformed first into wine, then into the ‘pale blossoms’ of an inflorescence of lightly patterned echoes.

By the time he composed his ‘Lecture on Modern Poetry’, Hulme had read Flint’s review of Storer’s volume (and almost certainly In the Net of the Stars). As Flint, Ford and Storer had done, he recommends a purging of old forms to make way for a newer, more flexible kind of verse. ‘The old poetry’, he suggests, ‘dealt essentially with big things’, and ‘the expression of epic subjects leads naturally to the anatomical matter and regular verse’; ‘the modern’, he argues, ‘is the exact opposite of this’: ‘it has become definitely and finally introspective and deals with expression and communication of momentary phrases in the poet’s mind’ (CWH, p. 53). The image recalls Ford’s portraits of the modern poet and foreshadows his suggestion that ‘modern poetry must be almost altogether introspective’.79 Like Ford, Hulme found the ‘old poetry’ ill-suited to his own needs. As he remembered:

I came to the subject of verse from the inside rather than from the outside. There were certain impressions which I wanted to fix. I read verse to find models, but I could not find any that seemed exactly suitable to express that kind of impression, except perhaps a few jerky rhythms of Henley, until I came to read the French vers libre which seemed to exactly fit the case.

The connection between impressions, modernity and vers libre is sponsored by a visual precursor. ‘What is this new spirit, which finds itself unable to express itself in the old metre?’ asks Hulme. ‘Are the things that a poet wishes to say now in any way different to the things that former poets say? I believe that they are’:

We are no longer concerned that stanzas shall be shaped and polished like gems, but rather that some vague mood shall be communicated. In all the arts, we seek for the maximum of individual and personal expression, rather than for the attainment of any absolute beauty[.] There is an analogous change in painting, where the old endeavoured to tell a story, the modern attempts to fix an impression. We still perceive the mystery of things, but we perceive it in entirely a different way – no longer directly in the form of action, but as an impression, for example Whistler’s pictures. We can’t escape from the spirit of our times. What has found expression in painting as Impressionism will soon find expression in poetry as free verse.

Hulme’s argument is close to the reasoning we find in the essays of Ford and Hulme’s fellow members of the Forgotten School. In lieu of ‘absolute beauty’, there is an emphasis on self-expression which requires the breakage of regular verse forms and their replacement with ‘free’ forms able to communicate fugitive shades of feeling. In particular, there is a feeling that regular metre falsifies the variable impressions it is summoned to convey, and a sense that the impression itself requires more flexible forms, whether in the splashed taches of impressionist painting or the loosened rhythms of vers libre.

More explicitly than do those of the other writers I have been discussing, Hulme’s analogies between impressionism and vers libre bring out the metaphysical dimensions of this argument. In the ‘Lecture’, Hulme suggests that art forms reflect frames of mind:

The ancients were perfectly aware of the fluidity of the world and of its impermanence; there was the Greek theory that the whole world was a flux. But while they recognized it, they feared it and endeavoured to evade it, to construct things of permanence which would stand fast in this universal flux which frightened them.

On this view, regular metre is an expression of existential anxiety, bringing the formless chaos of the world to intelligible expression through formal symmetry. ‘Hence the fixity of the form of poem and the elaborate rules of regular metre’ (p. 52). By contrast, ‘[t]he whole trend of the modern spirit is away from that’: ‘we frankly acknowledge the relative. We shall no longer strive to attain the absolutely perfect form in poetry’ (p. 53). It is well known that Hulme’s relativism was cultivated through his readings of Henri Bergson, to whose Essai sur les données immédiates de la conscience (1889) he was introduced a year before writing his ‘Lecture’, and which struck him with the force of revelation, as ‘a kind of mental explosion’.80 In particular, he was struck by Bergson’s suggestion that emotional states permeate one another without precise outlines, ‘as happens when we recall the notes of a tune, melting, so to speak, into one another’, but that ‘we instinctively solidify our impressions in order to express them in language’, so that ‘we confuse the feeling itself, which is in a perpetual state of becoming’, with the words we use to express it.81 What is less often remarked upon is that this explosion coincided with Hulme’s discovery of contemporary French poetry. Hulme had read André Beaunier’s La poésie nouvelle (1902) by 1905 or 1906; he read Kahn’s ‘Préface’ and Remy de Gourmont’s Le problème du style (1902) while studying in Belgium in 1908. Hulme’s interests in Bergson, impressionism and vers libre end up inflecting one another. In a review of Tancrède de Visan’s L’attitude du lyrisme contemporain (1911) for the New Age in August of 1911, he draws analogies between recent French verse and the vitalist current in Bergson’s thought, suggesting that ‘they are both reactions against the definite and the clear, not for any preference for the vague as such, nor for any mere preference for sentiment, but because both feel [that] the clear conceptions of the intellect are a definite distortion of reality’ (CWH, p. 58). Such analogies bring Bergson’s philosophy into correspondence with the poetics of broken or wavering line articulated by Kahn and de Gourmont, prompting Hulme’s own argument that perceptual experience is in a ‘continuous and unanalysable state of flux’ and therefore incompatible with the discrete rhythmic units prescribed by regular metre (p. 58). Thus, in his ‘Lecture’ he suggests:

Regular metre to this impressionist poetry is cramping, jangling, meaningless, and out of place. [It] destroys the effect just as a barrel organ does, when it intrudes into the subtle interwoven harmonies of the modern symphony.

As numerical time does in Bergson’s writings, here metrical regularity has a mortifying effect. By contrast, the impressionist poem is animated by the movements of the mind: ‘the length of the line is long and short, oscillating with the images used by the poet; it follows the contours of his thoughts and is free rather than regular’ (p. 52).

Hulme’s definition of impressionist poetry accommodates vers libre within a form which might seem to imply a set of distinct, even opposed aesthetic values. Hulme was introduced to the haiku at the Tour Eiffel meetings by Flint, who had himself come to the form via the French philosopher and doctor Paul-Louis Couchoud. In 1906, Couchoud had written a series of articles about the haiku in which he described a form of epigrammatic brevity whose freshness was untainted by the intellect:

Japanese poetry avoids wordiness and explanation. A single flower lies by itself on the snow. Bouquets are forbidden. The poem springs from an instantaneous lyric impulse, that wells up before thinking or passion have directed or made use of it[.] Words are the obstacle.82

The haiku might be thought of as a granular form, a discrete poetic particle that would be impressed on the mind of the reader. But for Couchoud the emphasis falls on the ‘immédiatement donnée’ of consciousness, the liquid flow of the ‘lyric impulse’ which sustains an intuitive connection of two disparate images, and which is preserved from the distortions of language by being spatially implied rather than explicitly narrated. This paradox would be absorbed into the poetics that Hulme elaborates in his ‘Lecture’, in which he suggests that the poet, when ‘moved by a certain landscape’:

selects from that certain images which, put into juxtaposition in separate lines, serve to suggest and to evoke the state he feels[.] Two visual images form what one may call a visual chord. They unite to suggest an image which is different to both.

The emphasis is on both unification and separation; the poem is split into two poles only in order that they might sustain a constant flow of analogic force in the mind. In his Introduction to Metaphysics (1903), Bergson had argued that intuition could be elicited through the juxtaposition of contrasting images, suggesting that ‘No image will replace the intuition of duration, but many different images, taken from quite different orders of things, will be able, through the convergence of their action, to direct the consciousness to the precise point where there is a certain intuition to seize on.’83 It is a model of cognition that is anti-rational: one in which the mind comprehends by leaping between things on impulse rather than by deliberative reasoning. But it would provide a cogent rationale for Hulme’s poetic analogies, which he calls ‘a method of sudden arrangement of commonplaces [in which the] suddenness’ – like ‘the accidental stroke of a brush’ – ‘makes us forget the commonplace’ itself, startling the mind into consciousness of its own flowing continuity (CWH, p. 39).

It is in this respect that Hulme’s interpretation of the haiku begins to complement his arguments about free verse. In Hulme’s short poems, figurative analogies are sustained by a parallel movement between different metrical forms, or by an escape into the space between forms as such. Published in December of 1909, Hulme’s ‘The Embankment’ (being ‘The fantasia of a fallen gentleman on a cold, bitter night’) is a haiku-like poem in which complex metrical patterns vary with the images they convey:

Hulme’s final metaphor is at once a deflationary allusion to Yeats’s ‘Cloths of Heaven’ and an example of the kind of sudden and unusual arrangement described in his notebooks. This compressed juxtaposition is augmented by the poem’s oscillation between long and short lines, full and assonant rhyme, regular and irregular stress. Thus, the poem opens with an alexandrine and an irregular hendecasyllable. In their unusual length and exuberant alliteration, both lines reflect the abundance they describe. The shorter third line serves as a miniature volta, signalling a shift from the past to the present and from affluence to indigence. Correspondingly, the line marks a moment of metrical change yet also initiates a rhyme scheme which tethers it to the poem’s opening and conclusion, thus constituting, at the level of aural sense, a moment of significant continuity. Indeed, it points to the most crucial continuity of all, since the rhyming vowel stressed by the line is also the pronoun designating the self. This delicate variation continues in the fourth line, a tetrameter with a feminine ending which reflects the speaker’s newly ‘fallen’ condition. The poem’s form alters again in its final third, its concluding sentence being split across three iambic lines which fan out with the rapid dilation of the poem’s metaphoric range. The dilation has a significance in the immediate context of the poem, where social descent paradoxically yields insight into the imaginative expansion and ascent that is the ‘very stuff of poesy’. In a broader sense, it exemplifies how two formal impulses – one towards order and regularity, the other towards flux and variability – can be made to relate to each other so as to foreground the transition between impressions of a lyric self that are different but nonetheless connected. Indeed, the poem’s internally fluctuating relationship between continuity and rupture not only parallels the paradox intrinsic to a theory of vers libre which would ‘fix’ fleeting impressions, but in its tense accommodation of both qualities – of flux and fixity, flow and permanence – also bears a startling resemblance to the impression metaphor itself.

Quoting Hulme’s poem in his ‘Reflections on Vers Libre’ (1917), Eliot noticed the connection between the kinds of variable prosody discussed by the Tour Eiffel group and the concept’s wider intellectual context:

The most interesting verse which has yet been written in our language has been done either by taking a very simple form, like the iambic pentameter, and constantly withdrawing from it, or taking no form at all, and constantly approximating to a very simple one. It is this contrast between fixity and flux, this unperceived evasion of monotony, which is the very life of verse. [It] is obvious that the charm of these lines could not be, without the constant suggestion and the skilful evasion of iambic pentameter.

Eliot’s reference to the life-giving qualities of a metre that ebbs and flows highlights the vitalist philosophy which underlay the vers libre experiments of Ford and the Forgotten School. After the group disbanded, their sense that a variable prosody might reflect the ‘infinite flicker’ of perception more truly than regular measures became an important touchstone for much modernist poetry – including, in however fraught a fashion, Eliot’s own verse.84 In the years following the cessation of the Tour Eiffel meetings, for example, it passed into Pound’s imagist manifesto, the third law of which was ‘[a]s regarding rhythm: to compose in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in sequence of a metronome’.85 As the century wore on, it became the dominant mode for poetry written in English. Yet in the process of its being assimilated, the origins of vers libre were quickly forgotten. Only a month after publishing his manifesto, Pound told Harriet Monroe that ‘the question of “vers libre” is such old game. It’s like quarrelling over impressionism or Manet.’86 The virtues of Manet and impressionism (like those of vers libre) were by then self-evident, but also tedious to discuss. They are spoken of as if they represented a battle that had been won, or a dispute that was too old to seem relevant. Indeed, Pound would often present imagism as an antidote to impressionism – a corrective to its blurriness and inexactness, its lack of clear definition. For a short but important period, however, the poets of the Forgotten School found in the impressionist haze a precedent for the undulant and irregular rhythms which underwrite imagism itself. Impressionism was not only the common term for writers who were in many ways mismatched; it also enabled them to join together a conception of the self as an unbroken stream and a prosody that was correspondingly complex and flexible. If impressionism began to cede its place in the poetic imagination to newer visual forms after 1909, the lasting effects of this final engagement should not be forgotten.