1. Introduction

The Iberian Massif is the largest and best-preserved segment of the European Variscan Orogen, extending across most of Portugal and western Spain (Martínez-Catalán et al. Reference Martínez-Catalán, Aller, Bastida and García-Cortes2008). It comprises variably deformed and metamorphosed Neoproterozoic and Palaeozoic rocks, intruded by Carboniferous granitoids during the Variscan orogeny. Based on a combination of stratigraphic, tectonic, metamorphic and magmatic criteria, the Iberian Massif has traditionally been divided into six zones (e.g. Lotze, Reference Lotze1945; Julivert et al. Reference Julivert, Fontboté, Ribeiro and Nabais-Conde1974; Farias et al. Reference Farias, Gallastegui, González Lodeiro, Marquínez, Martín-Parra, Martínez Catalán, de Pablo Maciá and Rodríguez-Fernández1987): Cantabrian, West-Asturian Leonese, Central Iberian, Galicia-Trás-Os-Montes, Ossa-Morena and South Portuguese. The Cantabrian and South Portuguese zones are external and preserve syn- to post-orogenic sedimentary sequences with minimal metamorphism. Toward the interior, Variscan deformation and metamorphism progressively intensify, reaching their peak in the Central Iberian Zone, which hosts numerous Variscan granitoids and anatectic domes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Geological sketch of the Central Iberian Zone (modified from Martínez-Catalán et al. Reference Martínez-Catalán, Martínez Poyatos, Bea and Vera2004) showing the location of different sectors from the Álamo Complex: (1) Villaseco-Pereruela; (2) Martinamor; (3) El Álamo-Bercimuelle, (4) Castellanos; (5) Mirueña; and (6) Sierra de las Yemas. The Galician-Castilian Lineament corresponds to the Northern CIZ metasediments and orthogneisses described by Villaseca et al. (Reference Villaseca, Merino, Oyarzun, Orejana, Pérez-Soba and Chicharro2014).

The Central Iberian Zone is commonly divided into three domains: the narrow Ollo de Sapo Domain to the north, the broad Schist–Greywacke Complex to the centre and south, and the Galician-Castilian gneissic lineament separating the two (Figure 1). Preliminary SHRIMP U–Pb zircon data (authors’ unpublished results) suggest that the magmatic sources of the Central Iberian granitoids were Ediacaran and Cambrian–Ordovician igneous rocks or immature sediments derived from them. However, only a few of these pre-Variscan rocks have survived the orogenic overprint. The oldest remnants include isolated gabbrodioritic bodies with zircon ages of 580 ± 3 Ma in the south (Talavera et al. Reference Talavera, Montero and Bea Barredo2008), and the 543 ± 6 Ma Almohalla granodioritic orthogneiss in the axial zone (Bea et al. Reference Bea, Montero and Zinger2003).

Cambrian–Ordovician rocks are more widespread and consist of variably deformed and metamorphosed peraluminous felsic granitoids and volcanic rocks, distributed along four NW-SE-trending lineaments, which include (Figure 1):

-

1. Ollo de Sapo Formation: Approximately 600 km long, bordering the Leonese Zone of Western Asturias, composed of augen gneisses with zircon rims dated to 490–475 Ma, surrounding Ediacaran or older cores. (Montero et al. Reference Montero, Bea, Gonzalez-Lodeiro, Talavera and Whitehouse2007; Bea et al. Reference Bea, Montero, Gonzalez-Lodeiro and Talavera2007).

-

2. Urra Formation: Located in the south near the Ossa–Morena Zone, less voluminous, composed of augen gneisses with abundant composite zircons (495–485 Ma rims and older cores; Sola et al. 2006, Reference Solá, Pereira, Williams, Ribeiro, Neiva, Montero, Bea and Zinger2008).

-

3. Central lineament: Medium-sized plutons of undeformed leucotonalites to granites (∼479 ± 4 Ma, SHRIMP U–Pb), with few or no inherited cores (unpublished data by P. Montero & F. Bea; see also monazite ages in Rubio-Ordóñez et al. Reference Rubio-Ordoñez, Valverde-Vaquero, Corretgé, Cuesta-Fernández, Gallastegui, Fernández-González and Gerdes2012).

-

4. Galician-Castilian Lineament: Situated between the Ollo de Sapo and the Schist–Greywacke Complex (Figure 1), with gneisses and metavulcanites. It extends from the Schistose Domain of Galicia–Trás-Os-Montes to the Spanish Central System, locally intersected by the Ávila Batholith. (Talavera et al. Reference Talavera, Montero, Bea, Lodeiro and Whitehouse2013).

The Álamo Complex (García de Figuerola et al. Reference García de Figuerola, Franco González and Castro1983) represents a key segment of the Galician-Castilian Lineament. It encompasses several sectors (Figure 2) that contain lithologies similar to those of both the Schist–Greywacke Complex and the Ollo de Sapo, exhibiting metamorphism ranging from low-grade to anatectic conditions. The complex is characterized by the presence of boron-rich rocks and the preservation of a complex pre-Variscan magmatic record within the Central Iberian Zone. Despite its complexity and transitional nature, the Álamo Complex remains poorly constrained in terms of magmatic chronology and fluid-related processes.

Figure 2. Simplified geological map of different sectors from the Álamo complex (based on García de Figuerola et al. Reference García de Figuerola, Franco González and Castro1983; Sánchez-Carretero et al. Reference Sánchez Carretero, Contreras López, Martín Herrero and Klein1991; Martín Parra et al. Reference Martín Parra, Martínez-Salanova, Moreno Serrano and Bellido Mulas1991; Monteserín et al. Reference Monteserín, Diez Balda, Bellido Mulas, García –Casquero, Martín-Serrano García and Santisteban Navarro1991; Hernández-Sánchez & Moro Benito, Reference Hernández-Sánchez and Moro Benito1991; Alonso Castro & López-Plaza, Reference Alonso Castro and López-Plaza1994; Diez-Balda et al. Reference Díez Balda, Martínez Catalán and Ayarza Arribas1995; Ares-Yañez et al. Reference Ares Yañez, Gutiérrez Alonso, Diez-Balda and Alvarez1995).

In this study, we present new field, petrographic, geochemical, isotopic and geochronological data that clarify the timing, sources and evolution of crustal melting events in this region. These findings provide key insights into the crustal reworking history of Central Iberia from the Neoproterozoic to the Carboniferous.

2. Field relations and petrography

Before describing the Álamo Complex, a brief review of the Ollo de Sapo and Schist–Greywacke Complexes is provided for comparative purposes.

2.a. The Ollo de Sapo Formation

The Ollo de Sapo Formation constitutes the largest accumulation of Cambrian–Ordovician magmatic rocks in Iberia, extending for approximately 600 km from the western Cantabrian coast to central Spain and forming the core of a Variscan anticlinorium. It comprises Cambrian–Ordovician felsic peraluminous volcanic rocks and granites, subsequently transformed into augen gneisses during the Variscan orogeny (Navidad, Reference Navidad1979; Navidad et al. Reference Navidad, Peinado, Casillas, Gutieérrez-Marco, Saavedra and Rábano1992; Diez Montes, Reference Díez Montes2007). Its name, translated as ‘Toad’s Eye’, derives from the deep-blue hue of quartz phenocrysts, caused by inclusions of sagenitic rutile (Parga-Pondal et al. Reference Parga Pondal, Matte and Cavdevilla1964).

The augen gneisses are characterized by K-feldspar megacrysts embedded within a foliated groundmass of quartz, oligoclase, K-feldspar, biotite, muscovite and, depending on the metamorphic grade, cordierite or garnet. Accessory minerals include apatite, ilmenite, zircon, monazite and occasional xenotime. Detailed studies reveal that most zircons possess rims dated between 490 and 475 Ma, which overgrow Ediacaran – and occasionally older – cores (Bea et al. Reference Bea, Montero, Gonzalez-Lodeiro and Talavera2007; Montero et al. Reference Montero, Talavera, Bea, Lodeiro and Whitehouse2009a).

2.b. The Schist-Greywacke Complex

The Schist–Greywacke Complex comprises a thick (up to ∼11 km), lithologically monotonous sequence of unfossiliferous Late Proterozoic to Cambrian shales and sandstones, interbedded with occasional conglomerates, limestones and sparse volcaniclastic rocks. Detrital zircons from these units are predominantly Ediacaran in age, displaying an age spectrum comparable to that of the inherited cores in the Ollo de Sapo zircons (Montero et al. Reference Montero, Talavera and Bea2017). Further details on the stratigraphy, composition and zircon geochronology of the complex are provided by Tassinari et al. (Reference Tassinari, Medina and Pinto1996), Rodríguez Alonso et al. (Reference Rodriguez Alonso, Díez-Balda, Perejón, Pieren, Liñán, López Díaz, Moreno, Gómez Vintanez, González Lodeiro, Martinez Poyatos, Vegas and Vera2004), Ugidos et al. (Reference Ugidos, Valladares, Barba and Ellam2003, Reference Ugidos, Sánchez-Santos, Barba and Valladares2010) and Talavera et al. (Reference Talavera, Montero, Martínez Poyatos and Williams2012).

2.c. The Álamo Complex

The Álamo Complex represents a discontinuous segment of the Galician–Castilian Lineament, extending for approximately 150 km W–E across the Central Iberian Zone, with exposures in six main sectors: Villaseco–Pereruela, Martinamor, Castellanos, El Álamo–Bercimuelle, Mirueña and Sierra de las Yemas (Figs. 1 and 2). The principal lithologies comprise psammitic–pelitic metasediments (MTS), gneisses, granites and pegmatoids, all of which were deformed and metamorphosed during the Variscan orogeny. A distinctive feature of the Álamo Complex is the abundance of tourmaline-rich rocks, which formed through polycyclic boron metasomatism affecting all lithologies and resulting in their widespread occurrence across the complex. Further details on these rocks are provided by Pesquera et al. (Reference Pesquera, Torres-Ruiz, Gil-Crespo and Jiang2005, Reference Pesquera, Torres-Ruiz, Gil-Crespo and Roda-Robles2009).

2.c.1. Metasedimentary rocks

The MTS consist predominantly of psammitic–pelitic rocks, similar to the schists and greywackes of the Schist–Greywacke Complex. Locally, they attain high-grade metamorphism, developing mineral assemblages comprising cordierite, sillimanite, biotite, ± K-feldspar, ± andalusite and ± tourmaline. The metamorphic zones are spatially narrow or incomplete, transitioning rapidly from the biotite zone to high-grade gneisses or schists, where low-pressure parageneses (sillimanite ± andalusite, cordierite) overlap with medium-pressure assemblages (garnet, staurolite). Migmatites and high-grade metamorphic rocks occur predominantly within antiforms or domes, particularly in the southern sectors, including El Álamo–Bercimuelle, Castellanos, Mirueña and Sierra de las Yemas.

2.c.2. Migmatites

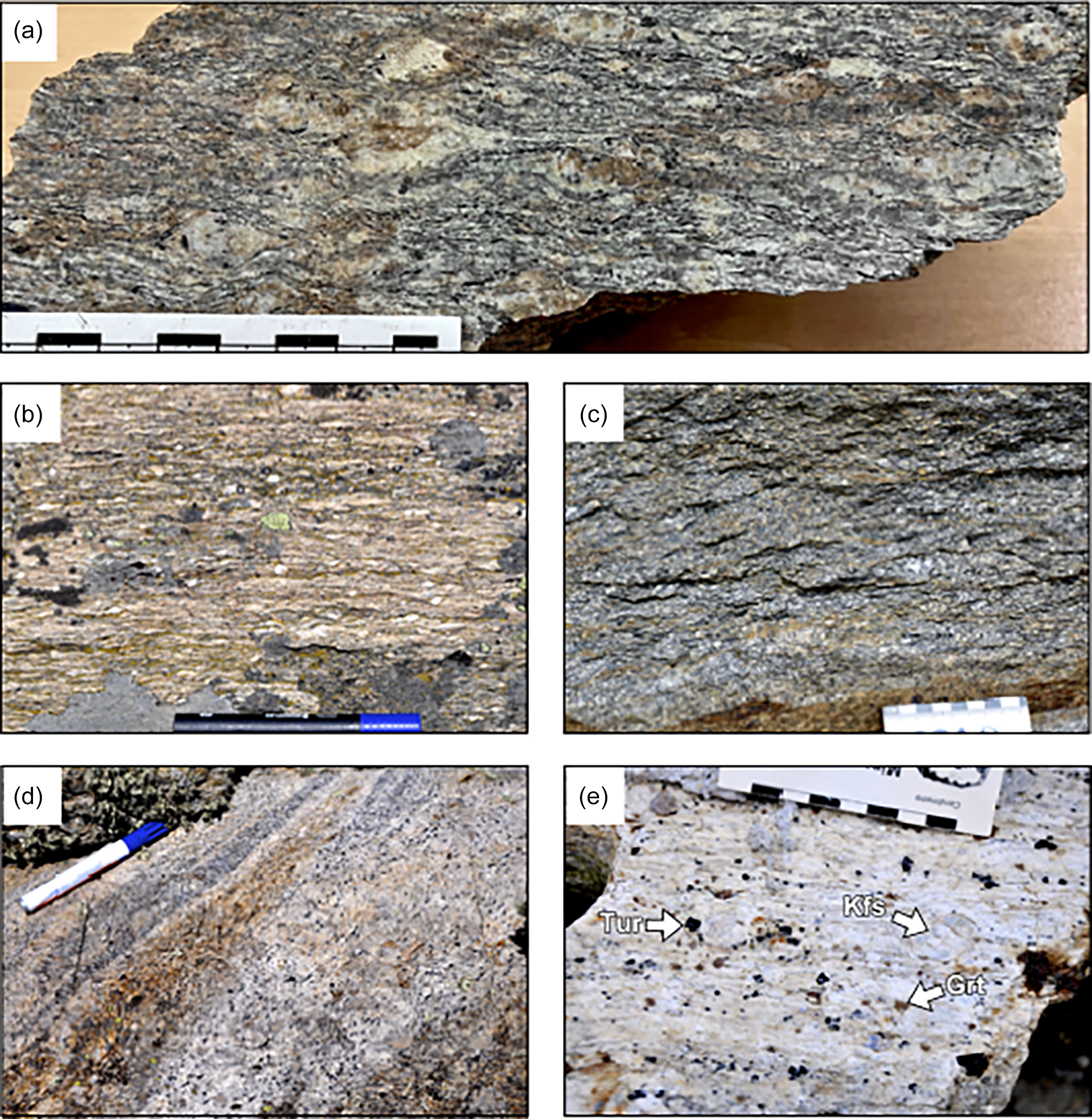

Migmatitic banded gneisses (BMG) in the Castellanos and Mirueña sectors consist of oval patches and lenticular layers of in situ neosomes, surrounded by a diffuse to conspicuous compositional layering subparallel to the regional foliation, likely resulting from progressive deformation. Lenticular, eye-shaped and σ-type quartz–feldspar porphyroclasts support this interpretation (Figure 3a). The compositional layering, predominantly on a millimetre scale, is defined by varying proportions of quartz + feldspar, ferromagnesian minerals (biotite ± cordierite ± tourmaline) and sillimanite, with apatite, zircon and monazite as common accessory minerals. The BMGs are likely derived from MTS and grade smoothly into stromatic migmatites (MX).

Figure 3. Field photographs of migmatites. (a) Migmatitic gneiss of stromatic character with leucosomes parallel to foliation and σ-porphyroclasts of plagioclase (b) Stromatic migmatite from the Castellanos area showing very thin, fine-grained leucosomes with the mineral assemblage plagioclase + quartz + biotite that are bordered by a very thin biotite-rich melanosome parallel to the foliation and compositional layering. The coarser-grained leucosomes are parallel to the layering and show boudinage and pinch-and-swell structures. However, thicker leucosomes that cut across the layering (L) can also be observed, possibly reflecting the injection of anatectic melt that was not generated ‘in situ’. The fine-grained grey layers (P) are probably the palaeosome slightly affected by partial melting. (c) Disharmonic fold with a boudinaged calc-silicate ‘resister’ acting as detachment level. Note the accumulation of leucosome in fold hinge zone and injection of leucosome in the interboudin zones. (d) Migmatite affected by shearing and boudinage. Schollen with a ghost layering derived from the stromatic metatexite (on top of the photography) are boudinaged with neosome ponding the boudin neck. Some domains of neosome have a nebulitic character and can be distinguished because they show neither foliation nor layering. A boudinaged thicker leucocratic lens can be observed in the central part of the photo that includes euhedral K-feldspar, plagioclase and interstitial quartz. (e) Diatexitic migmatite derived from psammo-pelitic protolith in the Sierra de las Yemas. It displays a relatively high proportion of schollen enclosed in leucocratic material, with irregular to sigmoidal shapes and various shades of grey. Some schollen have been largely assimilated appearing as ghost-like remains, while others display tiny light spots and veinlets of leucosome suggesting ‘in situ’ partial melting. (f) Migmatitic gneiss from the Bercimuelle area showing a subhorizontal foliation defined by biotite and elongate feldspar megacrysts.

Stromatic migmatites (MX) comprise pelitic layers (quartz + biotite + muscovite + plagioclase + sillimanite ± cordierite ± andalusite ± tourmaline) alternating with thin (<0.5 cm), very fine- to medium-grained leucosomes parallel to foliation and compositional layering (Figure 3b). Stromatic migmatites may be folded, showing leucosome migration and accumulation in interboudin zones of resistant layers and shear bands (Figure 3c). Leucosomes may be granitic (El Álamo–Bercimuelle sector) or trondhjemitic (Castellanos, Mirueña and Sierra de las Yemas sectors). In the latter, plagioclase (≤ An21) is the only feldspar present. Granitic leucosomes contain biotite ± cordierite ± muscovite as varietal minerals, with apatite ± tourmaline ± sillimanite ± andalusite as accessory phases. Trondhjemitic leucosomes, in contrast, are muscovite-dominated over biotite and contain large (up to 800 μm long) subhedral to euhedral apatite crystals, zircon and occasional tourmaline. Some plagioclase crystals include fine-grained (100–300 μm) kyanite prisms (Figure 4a), occasionally accompanied by sillimanite (fibrolite); the two aluminosilicates are never in direct contact. Textural criteria (Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Argles, Warren, Harris and Kunz2023) suggest that kyanite crystallized from the melt, indicating high-pressure partial melting during the Ediacaran events.

Figure 4. Microstructures of migmatites from the Álamo Complex. (a) Kyanite (Ky) included in plagioclase (Pl) within a trondhjemitic leucosome of a metatexite. (b) Interstitial pool of quartz (Qz) enclosing euhedral to subhedral plagioclase together with tabular biotite from a diatexite migmatite. Interstitial tourmaline occurs elsewhere of the thin-section. (c) Euhedral plagioclase with oscillatory zoning in the leucosome of a diatexite migmatite. (d) Perthitic K-feldspar megacryst (Kfs) with simple twinning in augen gneiss. Note the presence of rectangular quartz within the megacryst, which is coated by a clump of euhedral to anhedral crystals of K-feldspar and plagioclase with interlobate grain boundaries. Some K-feldspar grains have highly cuspate forms with tapering extensions along the intergranular boundaries. (e) Euhedral cordierite (Crd) in migmatized gneiss, together with biotite, plagioclase, quartz and K-feldspar. (f) Plagioclase porphyroclast with patchy zoning in a dark gneiss, surrounded by the dominant foliation defined by micas.

Diatexitic migmatites (DX) range from schollen and schlieren to massive mesocratic nebulites. Schollen structures occur in transitional zones from stromatic metatexites to diatexites (Figure 3d) and may form elongated, lenticular blocks parallel to foliation, or oval-to-subrounded blocks scattered within the leucocratic neosome without structural coherence (Figure 3e). Schlieric diatexites comprise subparallel leucocratic and biotite-rich schlieren, likely derived from schollen blocks. Diatexites commonly display a granular texture, with interlocking equant crystals of biotite, euhedral plagioclase and anhedral quartz ± cordierite ± K-feldspar ± tourmaline, with a weak foliation defined by biotite (Figure 4b). Plagioclase exhibits well-defined crystal faces against interstitial quartz and displays various zoning patterns (Figure 4c). Their composition varies from plagioclase- and biotite-rich to cordierite-rich diatexites. Quartz (∼12–47 vol%), oligoclase (∼5–36 vol%), K-feldspar (∼1–14 vol%) and biotite (∼15–35 vol%) are the major phases, with cordierite locally reaching ∼10 vol% and muscovite up to 5 vol%. Common accessory minerals include sillimanite, tourmaline, ilmenite, apatite and zircon.

2.c.3. Gneisses

The Álamo Complex contains a diverse suite of gneisses comparable to those of the Ollo de Sapo Formation. Their protoliths were predominantly igneous, as indicated by plagioclase porphyroclasts exhibiting well-developed zoning. These rocks are grouped as ‘orthogneisses’, although those derived from volcanoclastic rocks may contain a sedimentary component. Based on fabric, texture and mineralogy, four main types are distinguished: (i) migmatized gneisses (MAG), (ii) dark gneisses (DN), (iii) medium- to coarse-grained mesocratic to leucocratic gneisses (ON and ONL) and (iv) fine- to medium-grained gneisses (FM).

Migmatized augen gneisses (MAG) are fine-grained rocks with oval feldspar megacrysts (mostly < 2.0 cm) elongated parallel to the foliation (Figure 3f). They comprise quartz (34–36 vol%), K-feldspar (21–23 vol%), plagioclase (20–23 vol%), cordierite (3–13 vol%), biotite (8–14 vol%), sillimanite (<1 vol%), with apatite, zircon and ilmenite as principal accessory minerals. Dumortierite occurs sporadically in the Bercimuelle gneisses. Plagioclase megacrysts (An16–24) are subrounded to euhedral, with normal to patchy zoning (12–28% An), often displaying embayments by K-feldspar and quartz. K-feldspar megacrysts, some exhibiting Carlsbad twinning, are perthitic and commonly enclose small quartz crystals (Figure 4d). Cordierite forms subhedral to euhedral crystals, partially pinnitized (Figure 4e). Despite intense deformation, several textural features indicate in situ partial melting: large corroded quartz or feldspar crystals coated by K-feldspar + quartz ± plagioclase aggregates with inter-lobate to polygonal outlines; cuspate K-feldspar and quartz grains forming films along grain boundaries; string-of-beads textures; feldspar-rich pockets interpreted as pseudomorphs after melt; and rectangular quartz indicative of β-quartz growth (Figure 4c).

Dark gneisses (DN) form a typical lithology of the Castellanos antiform and the Mirueña horst, commonly interlayered with leucogranites and pegmatoids. These fine- to coarse-grained rocks exhibit a mylonitic fabric, containing quartz with undulose extinction and subgrains (44–48 vol%), anhedral to subhedral oligoclase (20–26 vol%), subhedral biotite (22–24 vol%), muscovite (5–9 vol%) and tourmaline (3–9 vol%). Plagioclase augens and tourmaline porphyroclasts (<1 cm), with strain shadows of fine-grained quartz ± biotite ± plagioclase, are wrapped by thin folia of prismatic micas and recrystallized quartz ± plagioclase ribbons (Figure 4d). Apatite, ilmenite and zircon are common accessory minerals.

Mesocratic (ON) to leucocratic (ONL) gneisses of granitic composition occur throughout the Álamo Complex. They typically form lenticular to elongated tabular bodies interleaved with metasedimentary rocks, often associated with tourmaline-bearing leucogranitic sheets. These medium- to coarse-grained rocks exhibit pervasive foliation and commonly an S/C fabric, with feldspar and quartz ± tourmaline porphyroclasts (Figure 5a). They comprise quartz (35–41 vol%), perthitic microcline (10–21 vol%), oligoclase to albite (24–30 vol%), biotite (4–16 vol%), muscovite (2–14 vol%) and tourmaline (<0.1–3.0 vol%), with apatite, Fe–Ti oxides and zircon as the main accessories.

Figure 5. Field photographs. (a) Orthogneiss of San Pelayo (Martinamor area) with a S-C fabric. Quartz ribbons, feldspar lenses and biotite films define the mylonitic foliation that wraps around the feldspar porphyroclasts. (b) Fine to medium-grained gneiss showing a C-type shear band cleavage (from upper left to lower right) that transects the main foliation. A dextral sense of shear is inferred from σ-type porphyroclasts of feldspar. (c) Biotite-rich dark gneiss with fine- to medium-grained plagioclase porphyroclasts. (d) Compositional layering in leucogranite consisting of alternating layers of two-mica granite with accessory tourmaline (dark layers) and granite with muscovite-tourmaline (light layers). (e) Strongly foliated pegmatoid with porphyroclasts of K-feldspar (Kfs), tourmaline (Tur) and garnet (Grt).

Fine- to medium-grained leptinitic gneisses (FM) form lenticular to tabular sheets (<5 m thick) in the Pereruela antiform and western Bercimuelle area. They occur interspersed within the metasedimentary sequence and display a C/S fabric, including small σ-type and tadpole-shaped porphyroclasts of feldspars and quartz. These rocks are granitic, with variable compositions: quartz (23–40 vol%), K-feldspar (13–42 vol%), oligoclase to albite (12–35 vol%), biotite (3–17 vol%), muscovite (4–16 vol%), and apatite as the most abundant accessory mineral. Myrmekites are common. Depending on the biotite modal fraction, these rocks may be mesocratic or leucocratic.

2.c.4. Leucogranites and pegmatoids

Leucogranites and pegmatoids occur throughout the Álamo Complex, ranging from tourmaline-bearing two-mica varieties (MBTL) to muscovite + tourmaline varieties (MTL). They occur as thin sheet-like to lenticular bodies interlayered with MTS and gneisses, and also as small stocks and discordant veins. In some localities, alternating MBTL and MTL layers are present (Figure 5b). Contacts with the metamorphic rocks are generally sharp, lacking evidence of contact metamorphism, or occur through a narrow zone of alternating thin layers of leucogranite and host rock.

Leucogranites and pegmatoids commonly display foliation, which may be strongly mylonitic, with quartz, K-feldspar, tourmaline and garnet porphyroclasts wrapped by fine-grained lamellae of white micas and quartz + feldspar (Figs. 5c). Modal compositions are 31–42% quartz, 27–56% feldspar, 0.0–7.0% biotite, 5–15% muscovite and up to 5% tourmaline. Tourmaline and biotite tend to display an antipathetic relationship in granitic systems, as common granitic melts have very limited access to the three-phase Tur–Bt–Ms field, as shown by phase relations and differentiation paths in the Al2O3-B2Al2FeO7-FeO (ABF) diagram (Pesquera et al. Reference Pesquera, Torres-Ruiz, García-Casco and Gil-Crespo2013). Accessory minerals include apatite, zircon, monazite, andalusite (<2%) and garnet (<0.8%), while sillimanite and cordierite are occasional. Tourmaline occurs as clasts or porphyroclasts in deformed rocks or as subhedral to euhedral prismatic crystals of variable colour. Common textures include tourmaline nodules with leucocratic halos, interpreted as related to late boron-rich fluids.

Pegmatoids comprise coarse-grained quartz, K-feldspar, albite, tourmaline and garnet, with abundant apatite, locally forming asparagolite crystals.

2.c.5. Variscan granitoids

Intrusive bodies occur in the Castellanos antiform, where a monzogranite is locally in contact with a mafic body, both occupying an area of approximately 6 km2 (Figure 1). The contact between the two is sharp, although local mingling and limited mixing can be observed. The monzogranite is homogeneous, fine- to coarse-grained and exhibits a seriate to porphyritic texture. It contains subrounded to angular, variably digested metasedimentary xenoliths (mostly < 10 cm). Its modal composition is quartz (23–29 vol%), alkali feldspar (24–27 vol%), plagioclase (31–37 vol%), biotite (7–11 vol%) and muscovite (3–6 vol%). Tourmaline nodules (<3 cm) and tourmaline + feldspar + quartz-bearing miarolitic cavities are common. Cordierite, andalusite and dumortierite occur occasionally. In the Castellanos sector, small leucogranitic bodies (e.g. sample CAS-13-7) are also present, compositionally identical to the MTL leucogranites but displaying a different zircon SHRIMP U–Pb age distribution (see Section 4.i).

The mafic body is medium-grained, with a massive fabric and subhedral equigranular texture. Its modal composition consists of quartz (1–18 vol%), andesine to labradorite (52–60 vol%), amphibole ± pyroxene relics (<12 vol%) and biotite (20–23 vol%). Prismatic apatite (up to 1.8 mm long), ilmenite, pyrite and zircon are common accessory minerals.

In the Mercadillo locality, within the El Álamo–Bercimuelle sector, a small (∼1 km²), heterogeneous tonalitic body crops out. It is composed of plagioclase (An21–44), biotite and quartz, with apatite, ilmenite and zircon as principal accessory minerals. The tonalite contains abundant subrounded to angular metasedimentary xenoliths that are variably digested. Their partial assimilation produced muscovite, K-feldspar and cordierite as minor constituents.

All these intrusive bodies yield abundant Variscan-age zircons, consistent with crystallization during late Carboniferous magmatism. The Castellanos monzogranite, the associated mafic body and the Mercadillo tonalite do not appear to be related to the Álamo materials, except for local assimilation. For the sake of simplicity, they were therefore excluded from the geochemical study.

3. Geochemistry

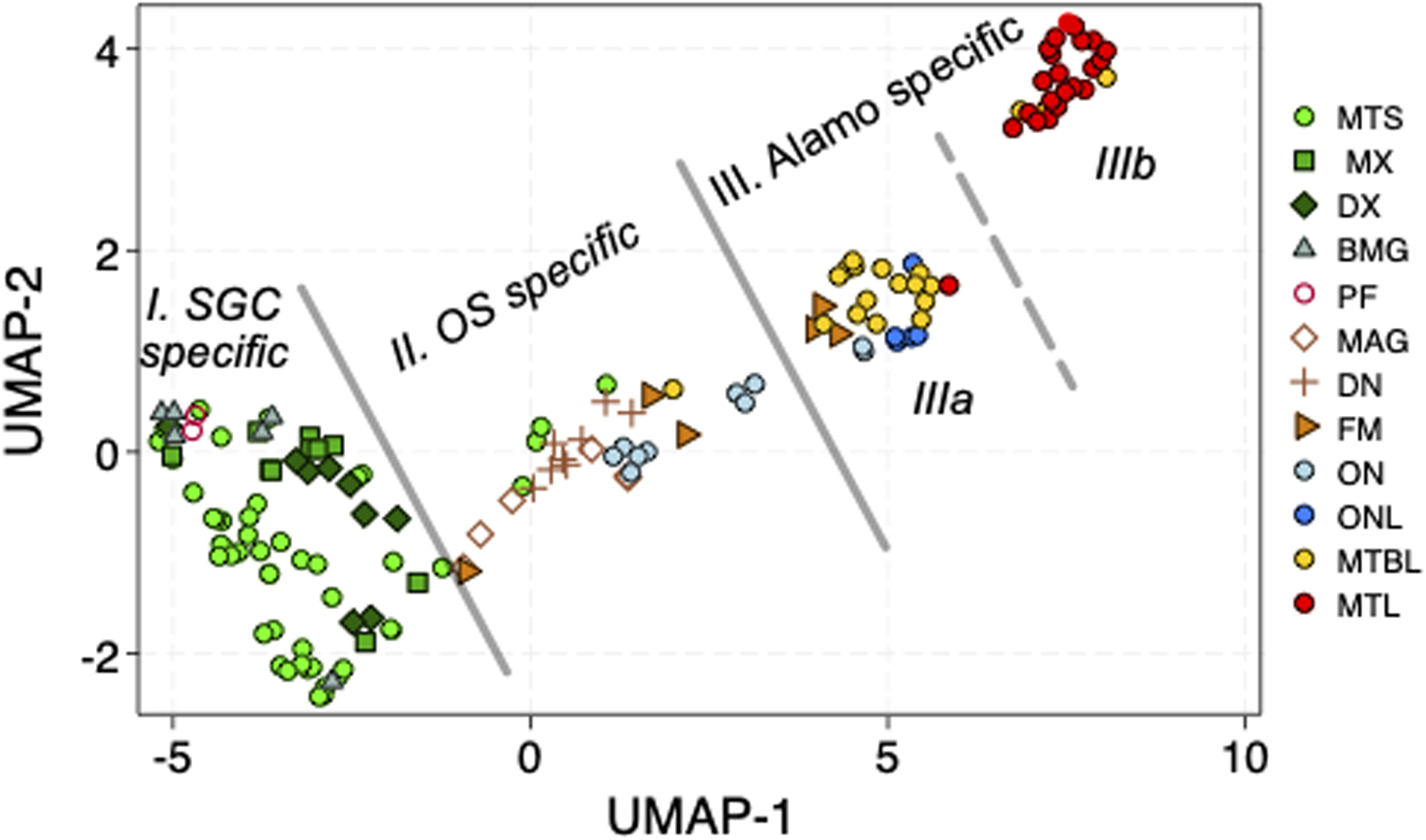

Bulk-rock major and trace element compositions for representative Álamo lithologies are reported in Supplementary Table S1 (analytical methods in Appendix). Initial data exploration employed UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction; McInnes et al., Reference McInnes, Healy and Melville2018), a technique that enables visualization of high-dimensional datasets by projecting them into a lower-dimensional space – typically two dimensions – while preserving local relationships among samples. The variables included all major and trace elements, excluding MnO, B and F due to low analytical precision or incomplete data, together with three derived parameters: (i) aluminium saturation index (ASI), (ii) the sum of CIPW normative quartz, orthoclase and albite and (iii) estimated heat production. This resulted in a (159 × 51) data matrix, which was normalized prior to UMAP application to account for differing units and variances among variables. The Castellanos monzogranite, associated mafic rocks and the Mercadillo tonalite were excluded from the analysis, as their protoliths are not genetically related to the Álamo Complex. Nevertheless, representative compositions of these lithologies are included in Supplementary Table S1.

From a geochemical perspective, the petrographic classes can be grouped into four main clusters (Figure 6). The first group (GI) includes MTS, migmatites and banded migmatitic gneisses. Their chemical compositions are similar to those of the Schist–Greywacke Complex; their UMAP parameters are poorly correlated, reflecting large chemical variability. The second group (GII) includes a few silicic MTS and gneisses with little or no tourmaline, with compositions comparable to the Ollo de Sapo augen-gneisses. Upon migmatization, they develop trondhjemitic leucosomes that plot in the same field. The third and fourth groups (GIII; GIV) encompass the variety of felsic tourmaline-bearing rocks that are characteristic of the Álamo Complex. GIII can be further subdivided into GIIIa, which includes the most leucocratic orthogneisses and MBTL leucogranites, and GIIIb, comprising MTL leucogranites and two MBTL samples containing accessory biotite. The UMAP groups are purely compositional and do not imply age or direct genetic relationships.

Figure 6. UMAP projection of the Álamo Complex samples reveals partitions that correspond well with the lithology. Group I (GI) comprises metasediments and the migmatites derived from them, while Group II (GII) consists of orthogneisses. Groups IIIa and IIIb (GIIIa and GIIIb) comprise the felsic, tourmaline-bearing rocks characteristic of the Álamo Complex. Specifically, GIIIa includes the most leucocratic orthogneisses and MBTL leucogranites, whereas GIIIb consists of two MBTL leucogranites containing accessory biotite, along with the MTL leucogranites. (MTS: metasediments; MX: stromatic migmatites; DX: diatexites; BMG: banded migmatitic gneisses; PF: porphyroids; MAG: migmatized augen gneisses; DN: dark gneisses; FM: fine-medium grained gneisses; ON: medium- to coarse-grained gneisses; ONL: medium- to coarse-grained leucogneisses; MBTL: two-micas leucogranite with tourmaline; MTL: tourmaline-muscovite leucogranite).

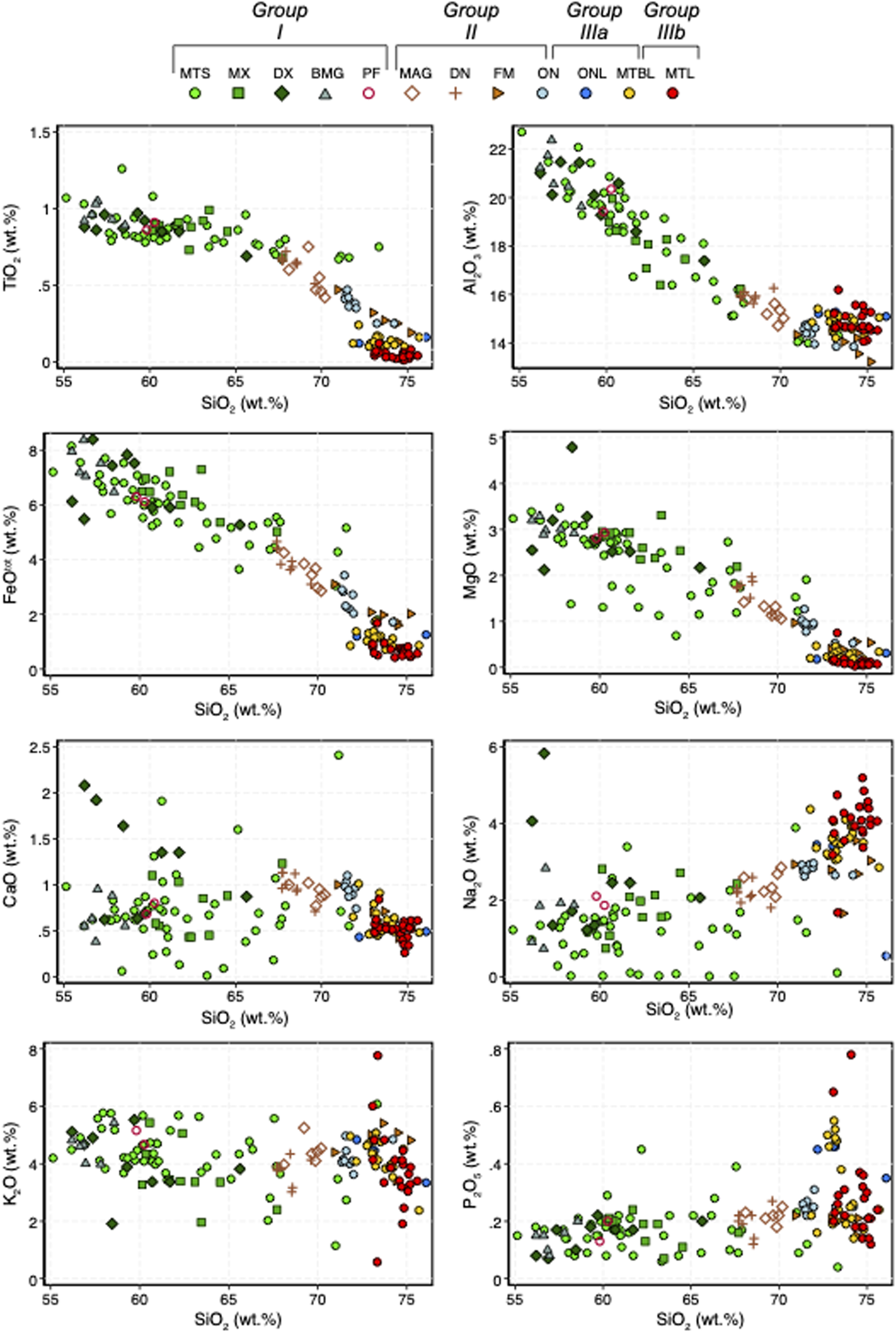

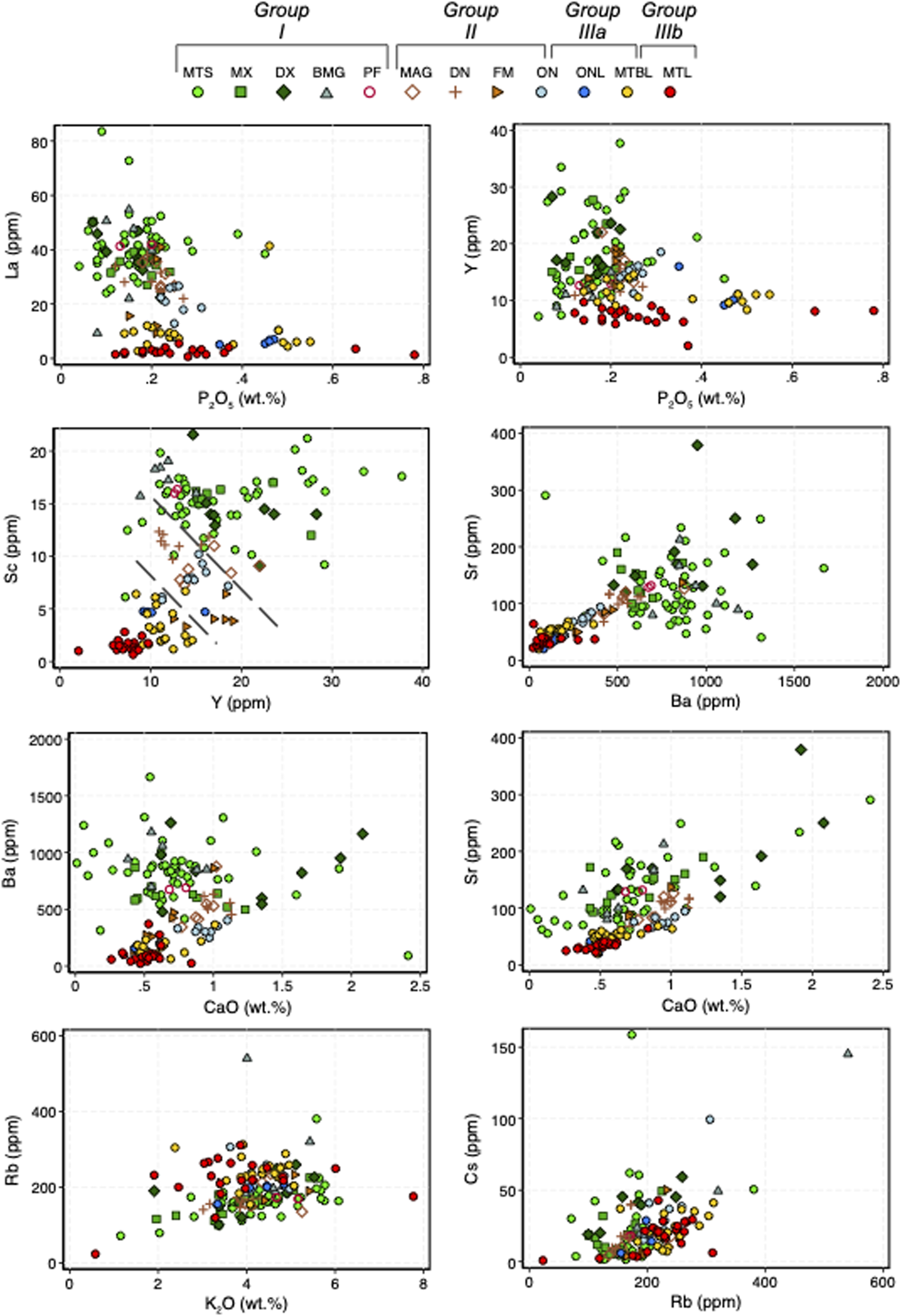

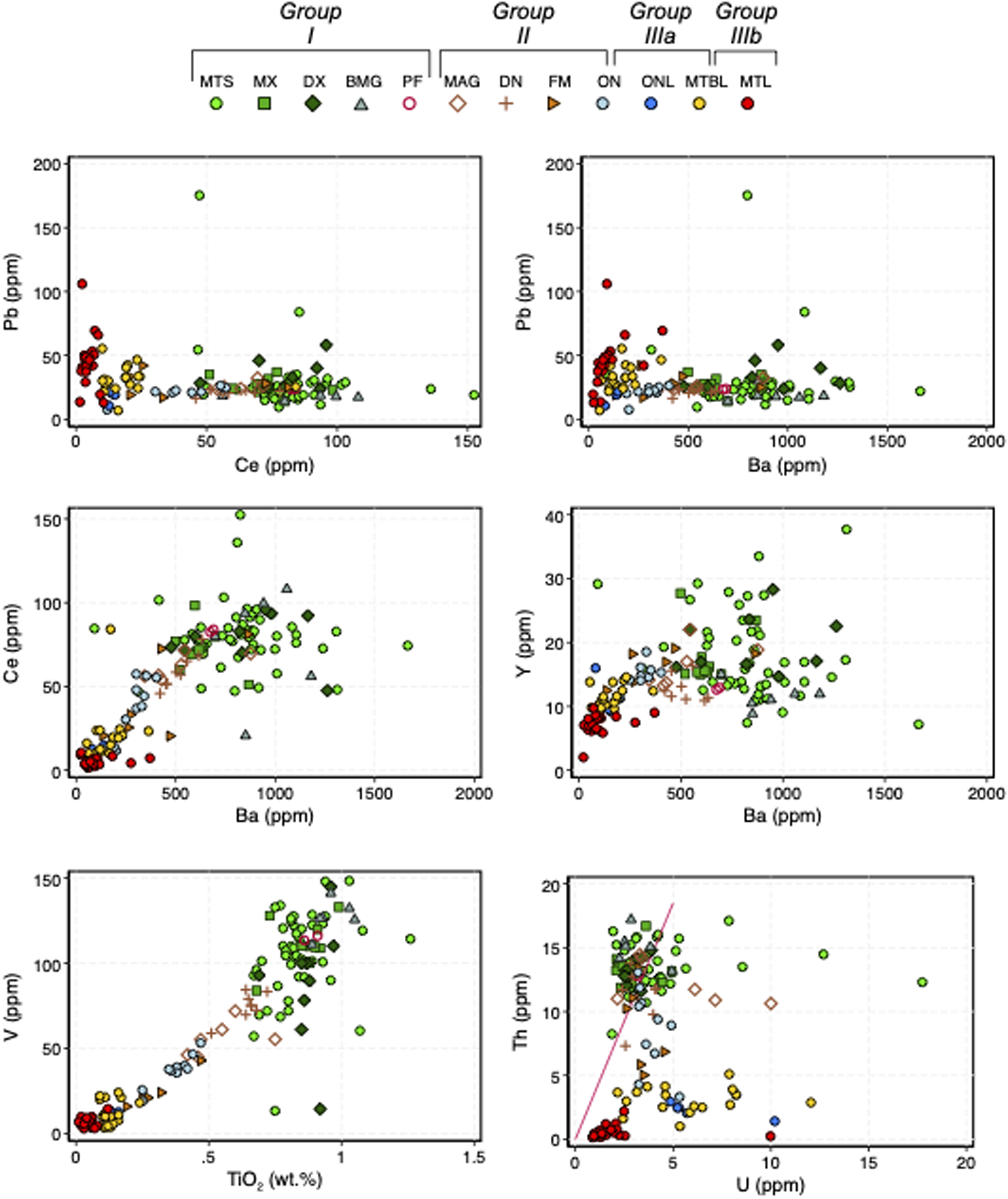

The four groups are also reflected, albeit more subtly, in binary plots (Figs 7, 8, 9). These show that GII and GIII are the most silicic, whereas GIIIa and particularly GIIIb are significantly depleted in TiO2, FeOtot, CaO, Sc, Y, LREE, Sr and Ba, but enriched in Na2O and Rb relative to groups I and II. TiO2, FeO, MgO, Sc and V correlate well with SiO2 in GII, but are uncorrelated in GI and cluster independently in GIIIa and GIIIb (Figs 7, 8, 9). Similar trends are observed for Sr vs Ba, V vs Ti and LREE vs Ba. P2O5 shows little variation with SiO2 in groups I and II, but increases markedly in some members of GIIIa and GIIIb (Figs 8, 9). These interelement relationships reflect the unequivocal sedimentary origin of GI and indicate that GII and GIII are primarily composed of distinct leucocratic granitoids not directly related by magmatic evolution.

Figure 8. Trace element variation diagrams. La and Y show no correlation with P2O5, indicating minimal influence of monazite and xenotime on REE distribution. GIII is depleted in Sc, Y, LREE, Sr and Ba, but enriched in Rb relative to GII and GI. TiO2, FeO, MgO, Sc and V correlate with SiO2 in GII, but not in GI, and cluster independently in GIIIa and GIIIb; Ba and Sr exhibit the same pattern. See text for details. Symbols are as in Figure 6.

Figure 9. Correlations among trace elements. Pb shows little variation in GI and GII, but increases markedly in GIII, particularly in GIIIb; it does not correlate with either Ba or LREE. Ce and Ba are well correlated in GII and, to a lesser extent, in GIII. Y vs. Ba and V vs. TiO2 exhibit a similar pattern. Zr/Hf clusters around the average crustal ratio, with no significant decrease in the most felsic rocks (see text for explanation). Th and U are fully decoupled in GII, which is enriched in U relative to Th. Symbols are as in Figure 6.

This interpretation is supported by the observation that all three groups have very similar Zr/Hf ratios, approximately 35 (Table S1), comparable to the average continental crust (e.g., Rudnick & Fountain, Reference Rudnick and Fountain1995), indicating that zircon fractionation – which typically occurs in highly differentiated granites (Bea et al. Reference Bea, Montero and Ortega2006) – was not significant. Similarly, the weak correlations between Rb–K2O and Rb–Cs, despite most gneisses having K/Rb < 160 (characteristic of highly fractionated granites; e.g., Ahrens, Reference Ahrens and Wedepohl1969, and references therein), support this conclusion.

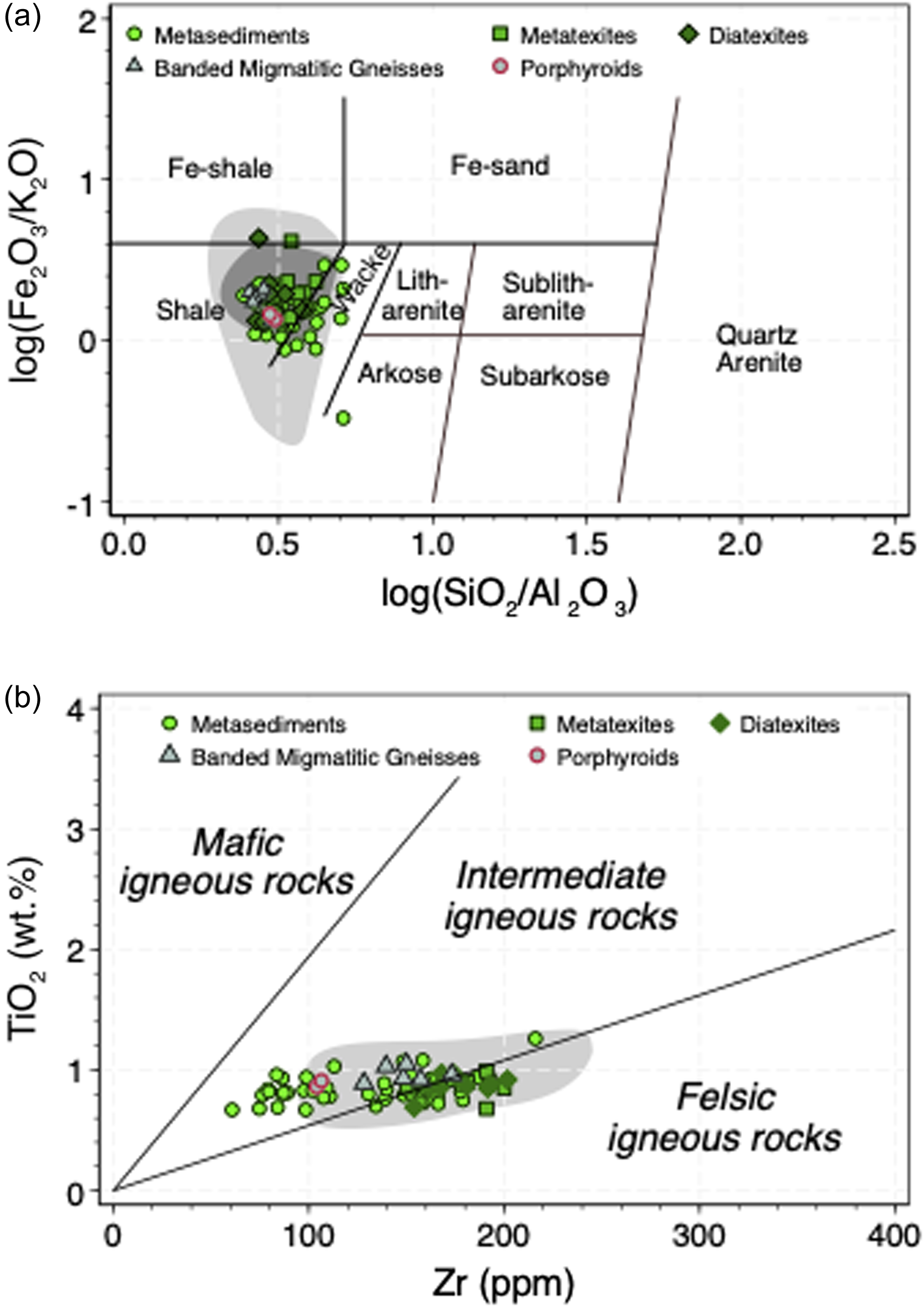

3.a. Group GI

In the SandClass diagram (Herron, Reference Herron1988), the Álamo MTS and their derived migmatites plot within the shale and wacke fields, overlapping the domain defined by neighbouring rocks of the Schist–Greywacke Complex, although slightly shifted towards the wacke field (Figure 10a). Student’s t-tests comparing the average compositions of both units (at the 97.5% confidence level) indicate that Álamo MTS are significantly enriched in SiO2, CaO, K2O, Rb, Sr, Ba, Sn, Mo and U, and exhibit higher heat production. In contrast, they have lower concentrations of TiO2, total FeO, V, Cr, Ni, Ga, Y, Zr, Hf and rare earth elements (REEs) compared to the Schist–Greywacke Complex (Supplementary Table S2). The A–CN–K diagram (not shown) suggests that Group I compositions follow a moderate weathering trend towards illite/muscovite formation, indicative of an intermediate to felsic source (Nesbitt & Young, Reference Nesbitt and Young1984). This interpretation is supported by their Zr/TiO2 ratios (Figure 10b; see Hayashi et al. Reference Hayashi, Fujisawa, Holland and Ohmoto1997).

Figure 10. (A) Siliciclastic sediment classification (Herron, Reference Herron1988). Álamo metasediments and migmatites plot in the shale–wacke fields, slightly shifted toward wackes, overlapping the neighbouring Schist–Greywacke Complex. (B) TiO2 vs. Zr plot showing that Álamo metasediments and migmatites derive from intermediate to felsic source rocks (Hayashi et al. Reference Hayashi, Fujisawa, Holland and Ohmoto1997).

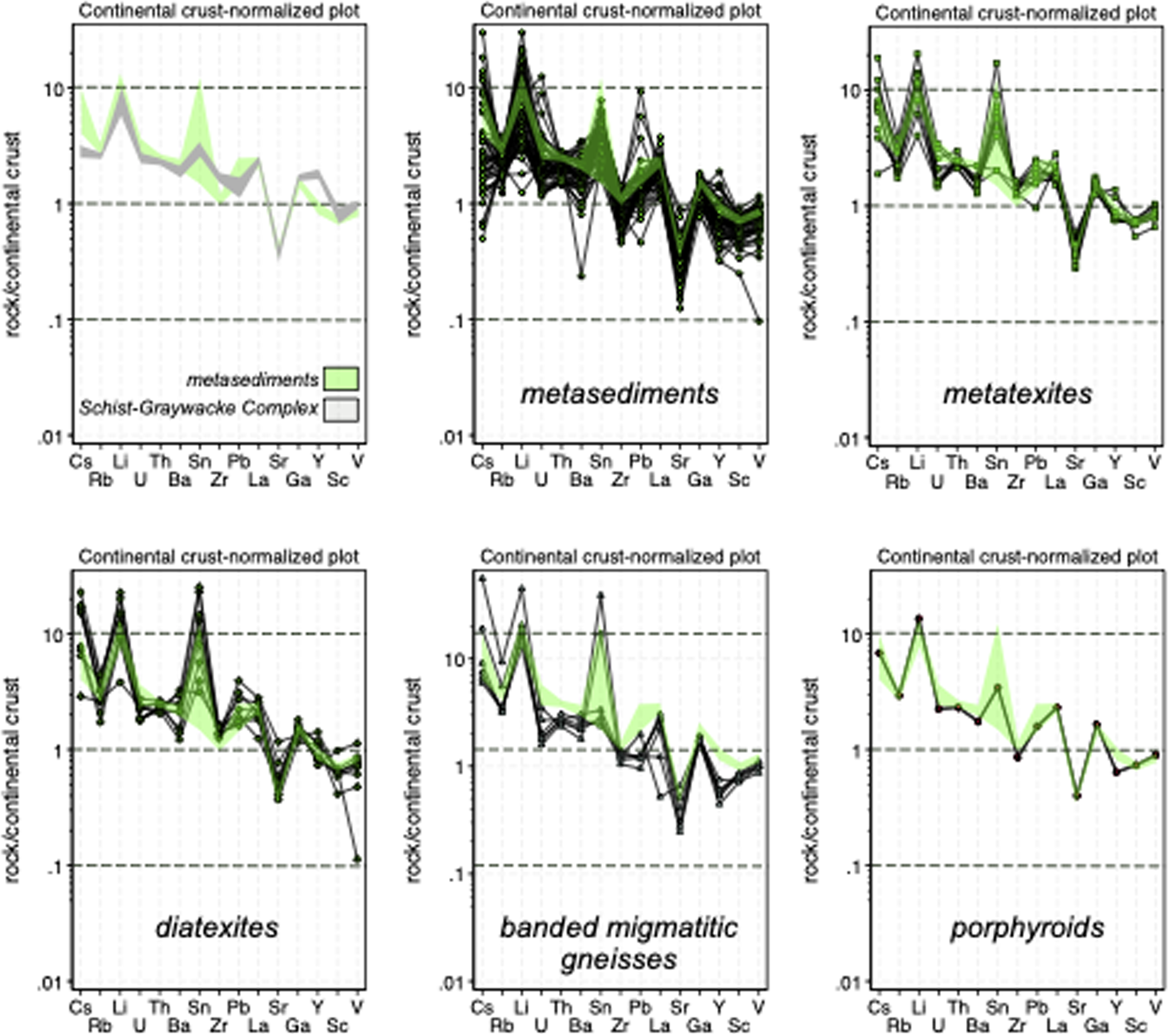

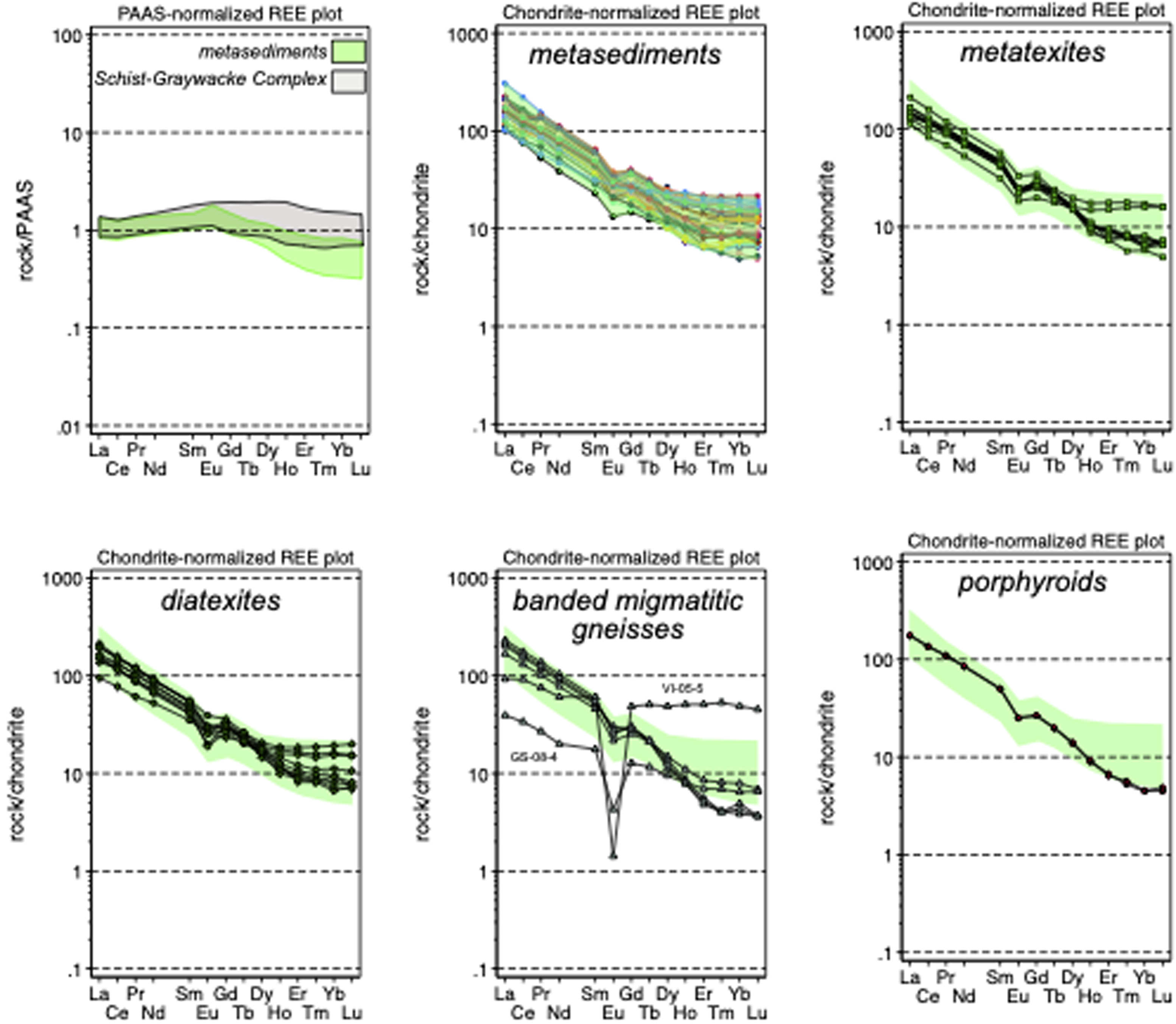

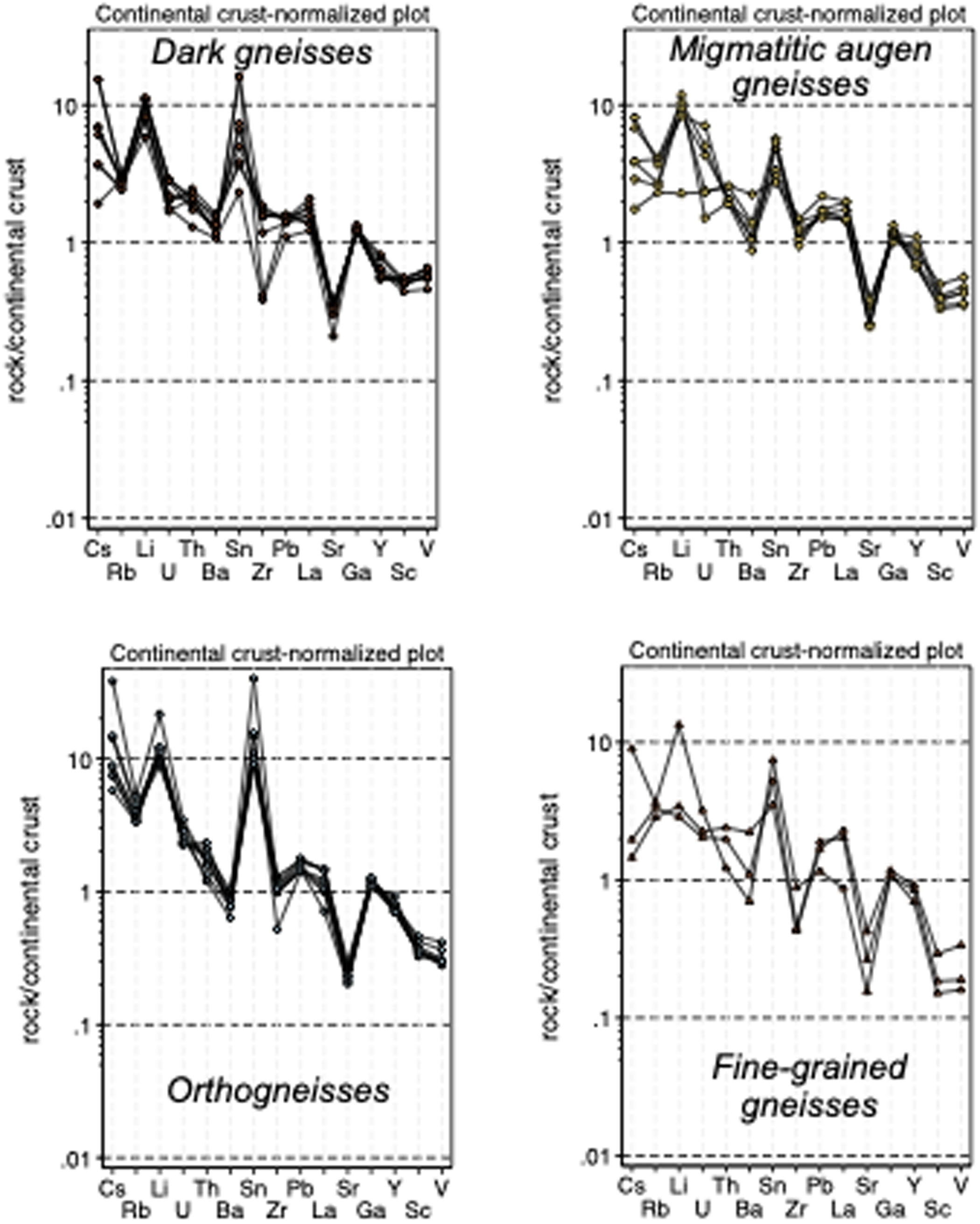

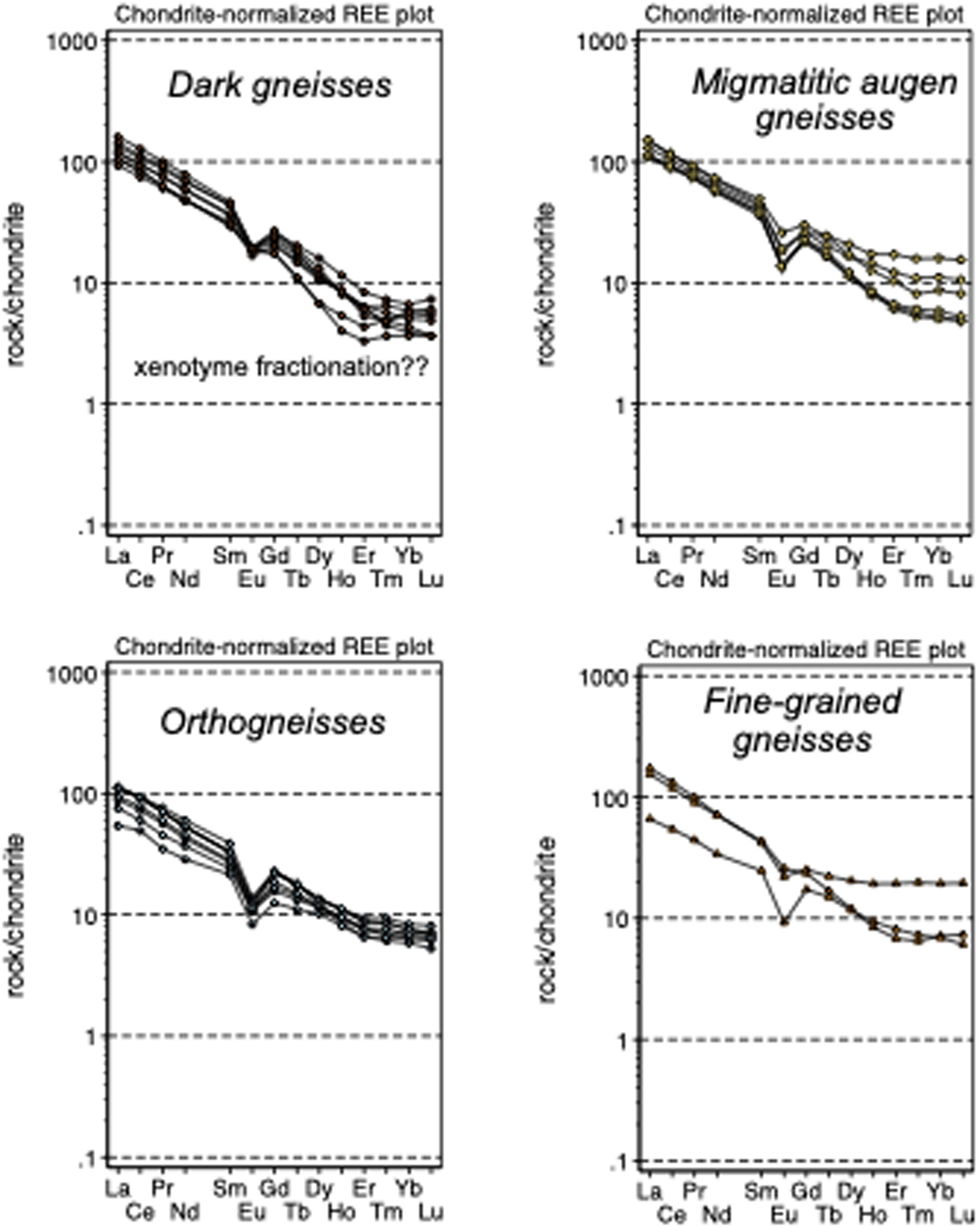

Continental crust–normalized trace element patterns (using values from Rudnick & Fountain, Reference Rudnick and Fountain1995) highlight compositional differences relative to the Schist–Greywacke Complex, particularly the pronounced enrichment in Sn. This enrichment is further accentuated in the migmatites and some banded migmatitic gneisses (Figure 11). When normalized to the Post-Archaean Australian Shale average (Figure 12), the Álamo MTS display a weak positive Eu anomaly and pronounced HREE depletion – features absent in equivalent lithologies from the Schist–Greywacke Complex. Chondrite-normalized REE patterns of the migmatites generally overlap with those of the MTS, with the exception of two banded migmatitic gneisses (Figure 12). These exhibit a pronounced negative Eu anomaly, a subtle negative Nd anomaly – consistent with monazite fractionation (Bea & Montero, Reference Bea and Montero1999, and references therein) – and, in one instance, HREE enrichment with a flattened REE distribution. Such features suggest derivation from a garnet-bearing granitic protolith and underscore the compositional diversity of the source materials involved in the formation of the Álamo Complex.

Figure 11. Continental crust–normalized trace element plots for Umap group GI (Rudnick & Gao, Reference Rudnick, Gao, Holland, Turekian and Rudnick2003). All samples show pronounced Li and Sn peaks.

Figure 12. PAAS- and chondrite-normalized plots for Umap group GI (PAAS values from Nance & Taylor, Reference Nance and Taylor1976; chondrite values from McDonough & Sun, Reference McDonough and Sun1995). Álamo metasediments are HREE-deficient relative to the Schist–Greywacke Complex. The two migmatitic gneisses show distinct patterns, likely due to garnet-bearing protoliths.

3.b. Group GII

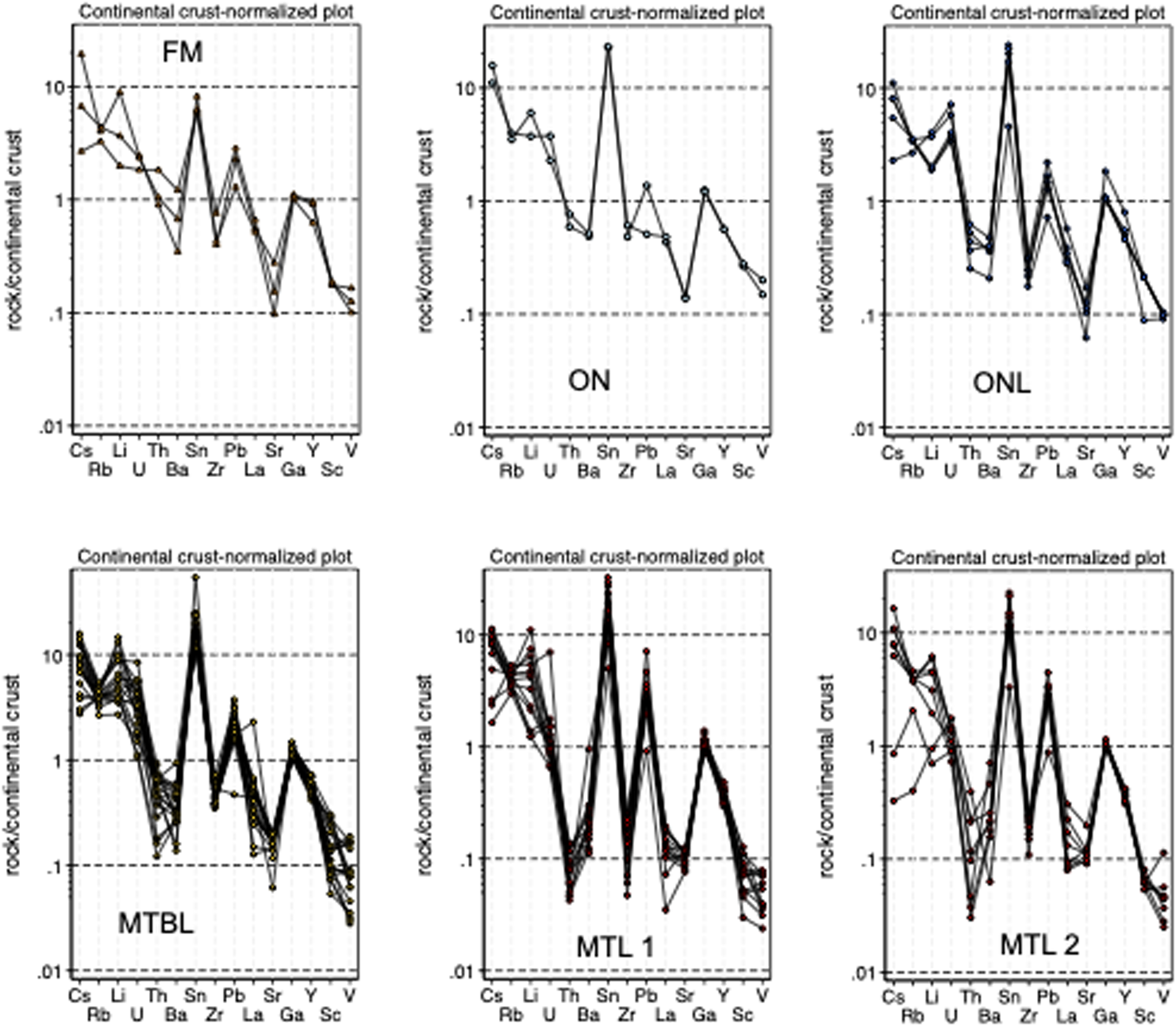

This group comprises strongly foliated gneisses of orthoderived origin, consistent with the pronounced inter-element correlations observed (Figs. 7, 8, 9). Based on increasing SiO2 content, Group II rocks can be petrographically subdivided into DN (SiO2 ∼ 67.7–69.6 wt.%), MAG (∼ 69.6–70.2 wt.%), medium- to coarse-grained gneisses (∼ 71.3–72.0 wt.%) and fine-grained gneisses (∼ 72.9–74.6 wt.%). These rocks are felsic and peraluminous, with K2O > Na2O, and their major element compositions are broadly similar to those of the Ollo de Sapo gneisses within the same silica range. Their trace element signatures are likewise comparable to those of the Ollo de Sapo gneisses, although frequently enriched in Li, Cs and Sn – paralleling the enrichment observed in Álamo MTS relative to the Schist–Greywacke Complex (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Continental crust–normalized plots for Umap Group GII (Rudnick & Gao, Reference Rudnick, Gao, Holland, Turekian and Rudnick2003). Li and Sn peaks characteristic of Álamo materials are especially pronounced in the orthogneisses. The yellow band shows the group average ± two standard deviations.

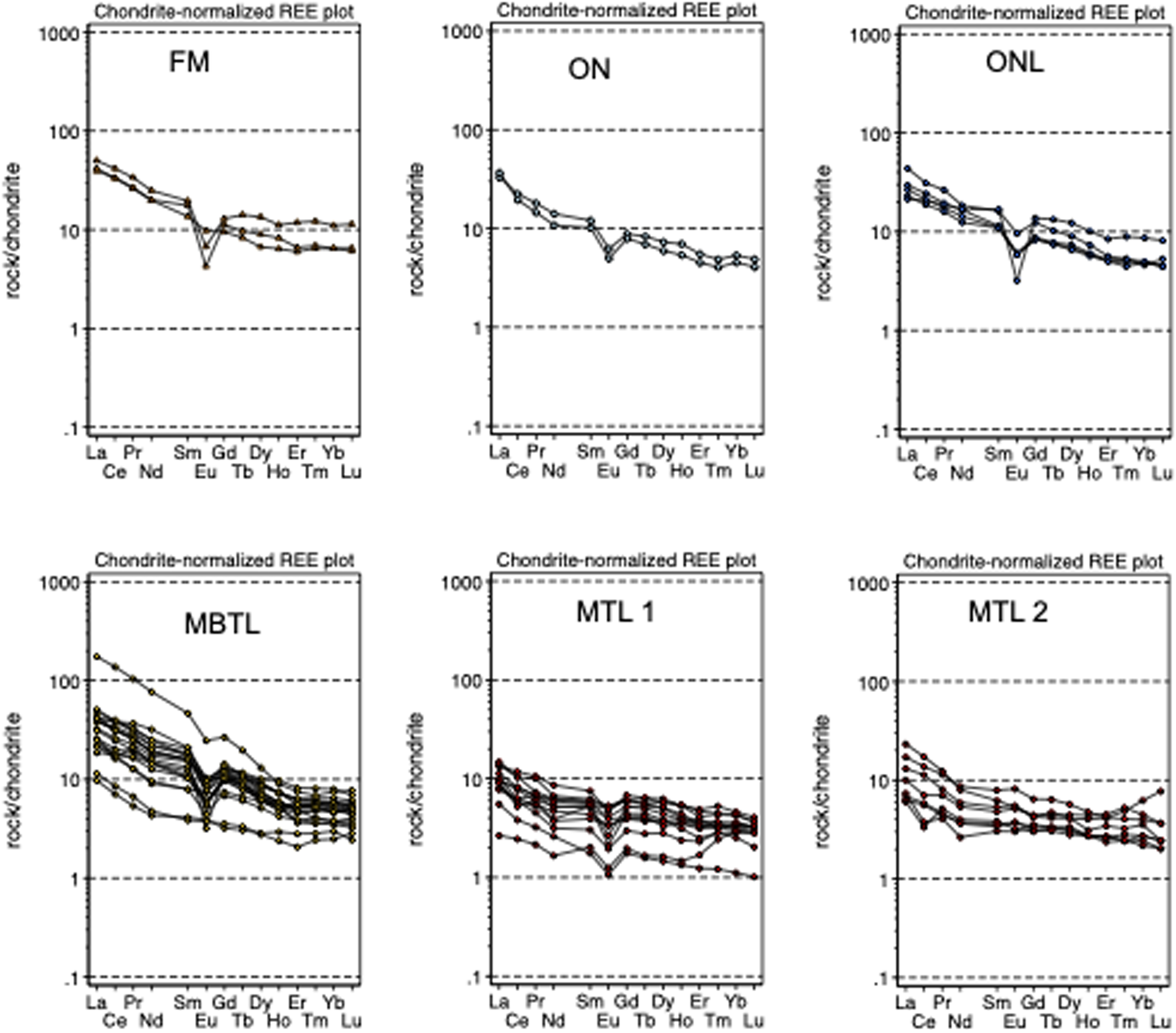

The lower-silica DN exhibit pronounced HREE depletion, particularly in Dy–Ho–Er and Y, similar to that observed in the banded migmatitic gneisses, likely reflecting a primary feature of the protolith (Figure 14). The remaining samples plot within the same compositional field as the Ollo de Sapo gneisses, with LaN values around 100, LuN near 10, and Eu*/Eu values typically ranging between 0.6 and 0.7.

Figure 14. Chondrite-normalized plots for Umap group GII (McDonough & Sun, Reference McDonough and Sun1995). Most samples show typical metasedimentary patterns, except for slightly lower Dy–Er abundances in some dark gneisses, likely related to xenotime fractionation.

3.c. Groups GIIIa and GIIIb

Groups GIIIa and GIIIb comprise lithologies unique to the Álamo Complex, with no direct equivalents in either the Ollo de Sapo or the Schist–Greywacke Complex. Group GIIIa includes muscovite–biotite–tourmaline leucogranites (MBTL), together with tourmaline-bearing leucocratic orthogneisses and certain fine-grained gneisses. Group GIIIb encompasses muscovite–tourmaline leucogranites (MTL), as well as a few MBTL samples in which biotite occurs only as an accessory mineral. Most rocks in both groups are highly silicic (SiO2 ∼ 73–76 wt.%), with low contents of TiO2, total FeO, and MgO, and relatively high Na2O concentrations (Figure 7).

Despite overall similarities, the MTL leucogranites exhibit notable compositional differences. They are depleted in TiO2, FeO, MgO, REEs, Ba, Sr, Th and U, and are clearly distinguished in plots such as La or Y vs. P2O5, Sc vs. Y and Th vs. U (Figs. 7, 8, 9). For a given K2O content, the MTL rocks are enriched in Rb but poorer in Cs relative to the other lithologies. MTL samples also have lower Th and U concentrations than MBTL. Both groups display notably low Th/U ratios (0.3–0.6), in stark contrast to the remaining Álamo Complex rocks, which – apart from a few outliers – cluster around a Th/U value of ∼3.7, consistent with mantle- and crustal-derived compositions.

Group GIII rocks exhibit distinctive trace element patterns when normalized to continental crust values, featuring progressively deeper negative anomalies in Th, Ba, Sr and La, a pronounced Sn enrichment, and highly variable Cs and Li contents (Figure 15). Chondrite-normalized REE patterns indicate that GIII rocks have lower REE concentrations than GII rocks, display flatter profiles and exhibit variable Eu anomalies. Notably, as total REE concentrations decrease, the Eu anomaly tends to vanish, particularly in certain MTL leucogranites (Figure 16). For clarity, MTL samples are subdivided into two subgroups: MTL1 (with a negative Eu anomaly) and MTL2 (lacking an Eu anomaly).

Figure 15. Continental crust–normalized plots for Umap groups GIIIa and GIIIb (normalization values from Rudnick & Gao, Reference Rudnick, Gao, Holland, Turekian and Rudnick2003).

Figure 16. Chondrite-normalized plots for Umap groups GIIIa and GIIIb (McDonough & Sun, Reference McDonough and Sun1995). These rocks show the lowest REE contents and minimal LREE/HREE fractionation within the Álamo Complex. MTL samples with a negative Eu anomaly (MTL1) and those without (MTL2) are shown separately for clarity.

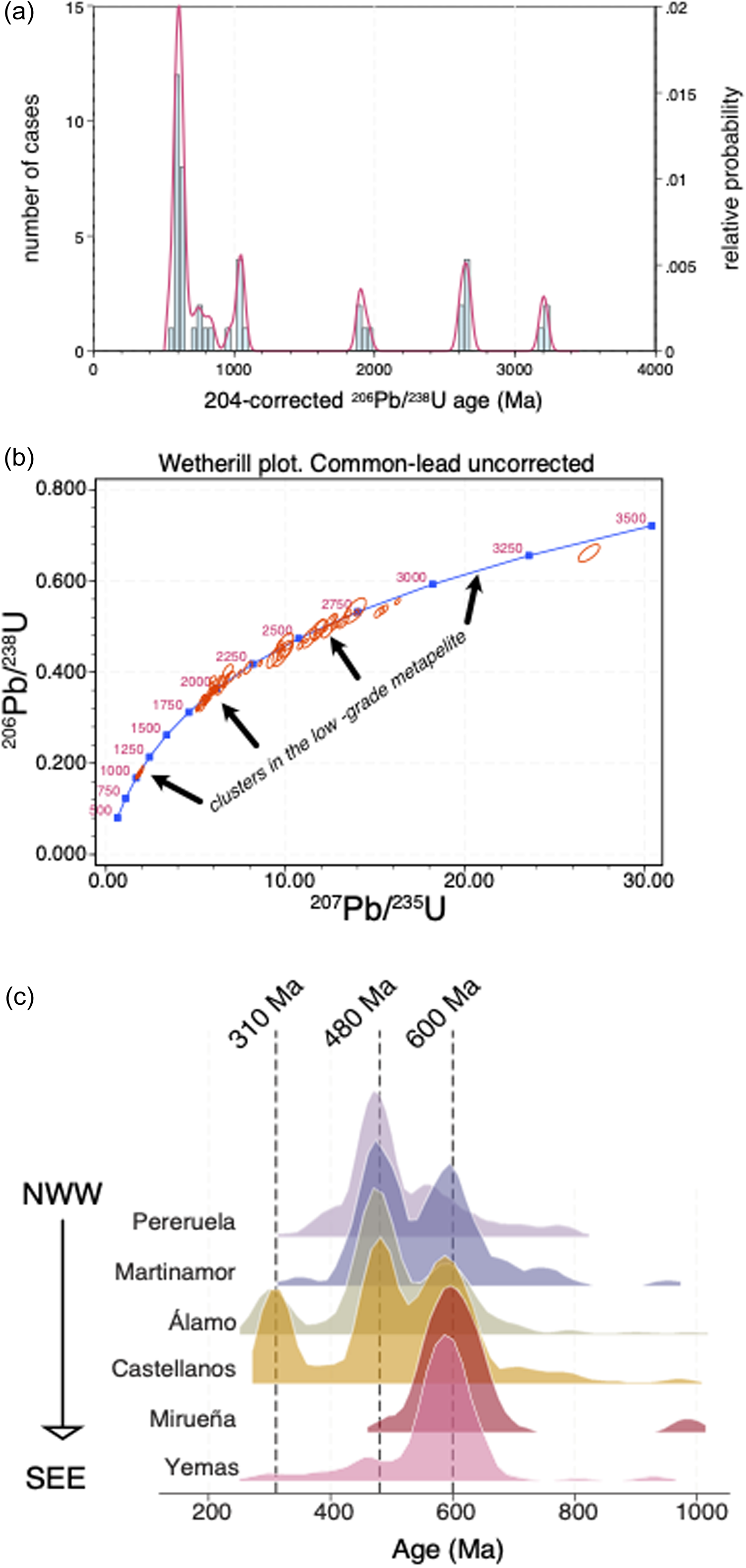

Figure 17. (a) Frequency plot of detrital zircon SHRIMP U–Pb ages from a shale of the Schist–Greywacke Complex, for comparison with pre-Cambrian zircons of the Álamo Complex. Most zircons are Ediacaran; minor Cryogenian, Tonian–Stenian, Palaeoproterozoic (∼1.9 Ga), Neoarchaean (∼2.6 Ga) and Mesoarchaean (∼3.2 Ga) grains are also present. Mesoproterozoic zircons are absent. (b) Wetherill concordia plot of pre-Ediacaran zircons from the Álamo Complex. Most crystals are cores rimmed by younger zircon, affected by Pb diffusion (Bea & Montero, Reference Bea and Montero2013), producing the observed discordias. Age distribution is comparable to the SGC shale. (c) Ridgeline kernel density plot of zircons <1.0 Ga, arranged from NNW to SSE. Main peaks correspond to Ediacaran and Cambrian–Ordovician ages. Variscan ages appear mainly in Castellanos and Álamo sectors. See text for discussion.

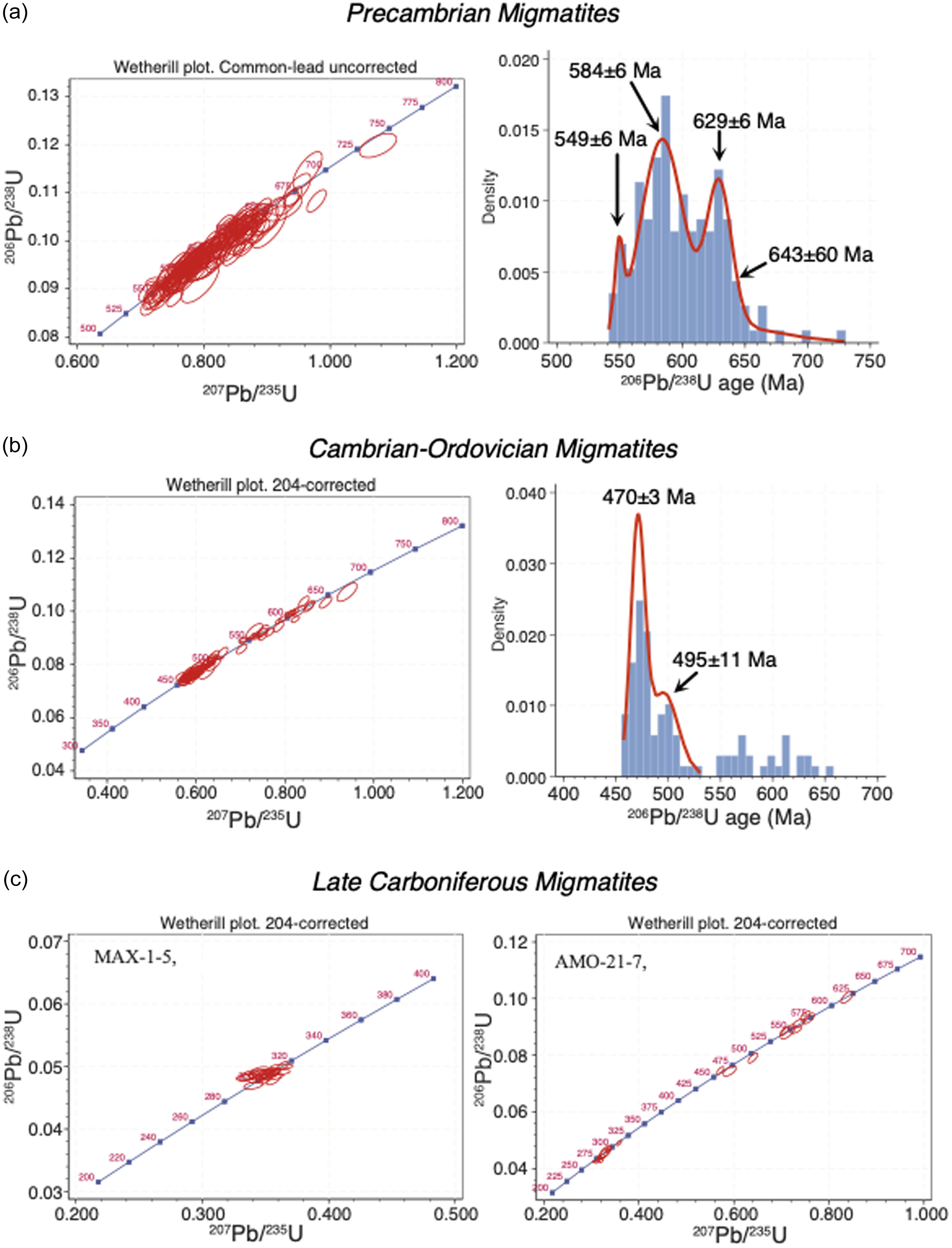

Figure 18. (a) Concordia plot, histogram and age-density distribution of migmatites without Cambrian–Ordovician or younger zircons. A finite mixture model identifies three main Ediacaran zircon populations at 549 ± 6 Ma, 584 ± 6 Ma and 629 ± 6 Ma, plus a minor cluster near 640 ± 60 Ma. Older Ediacaran zircons occur as cores rimmed by younger overgrowths. (b) Migmatites with Cambrian–Ordovician zircons show a bimodal population at 495 ± 11 Ma and 470 ± 3 Ma. Ediacaran cores are rimmed by Cambrian–Ordovician overgrowths; despite Pb diffusion and few grains, the three Precambrian age groups remain recognizable (note different scales). (c) Concordia plots for migmatites containing Late Carboniferous zircons. Sample MAX-1-5 shows no inherited zircon. (see text).

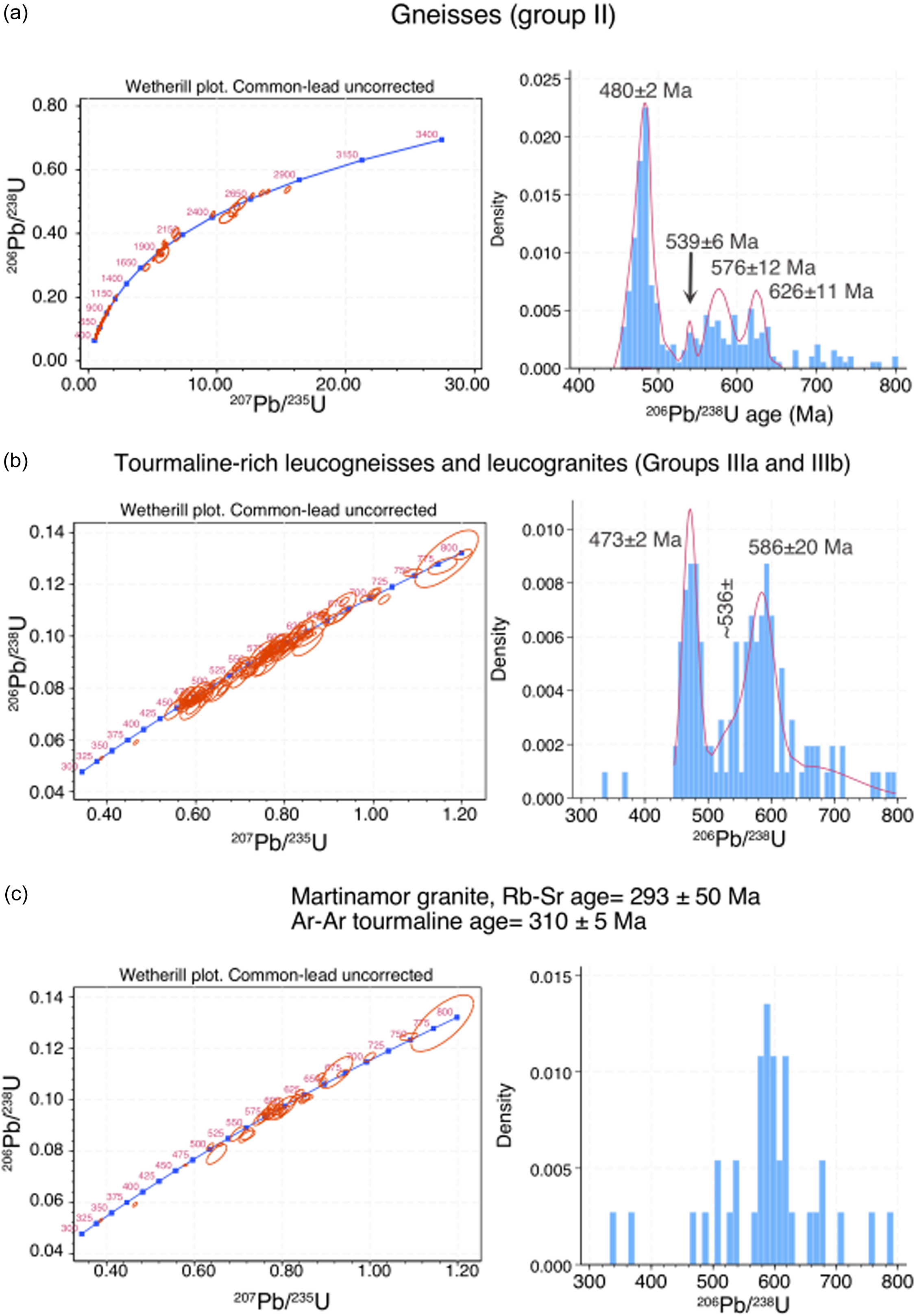

Figure 19. (a) Concordia plot, histogram and age-density distribution of orthogneisses. A prominent Cambrian–Ordovician peak (480 ± 2 Ma) and abundant Ediacaran inheritance with three main age groups match those in the Precambrian migmatites. (b) Tourmaline-rich leucogranites of GIIIa and GIIIb show similar Cambrian–Ordovician and Ediacaran zircon distributions, with a minor Late Carboniferous component. (c) The Martinamor leucogranite is Variscan based on previous Rb–Sr and Ar–Ar data, although most zircons are Ediacaran.

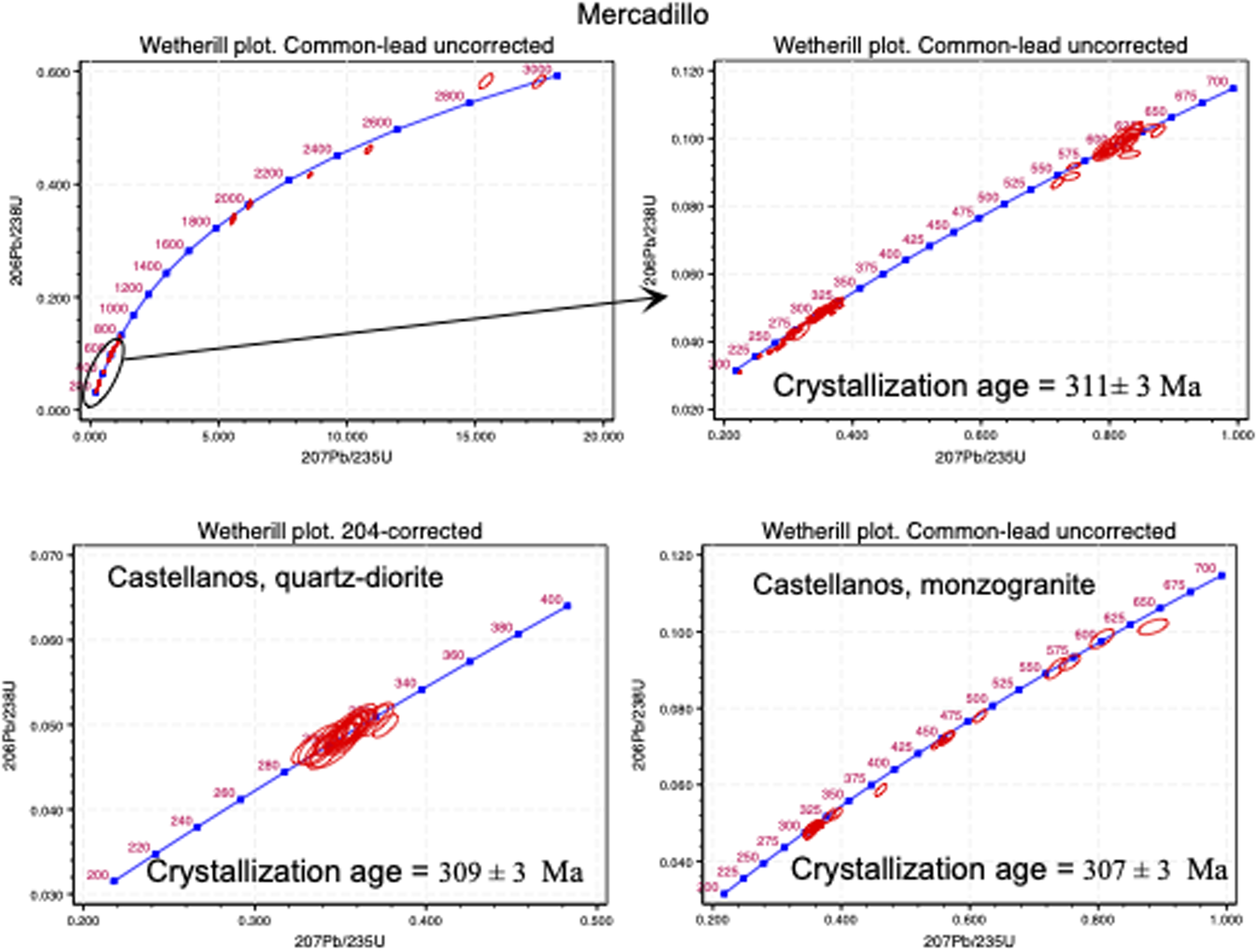

Figure 20. Concordia plots of Variscan rocks from the Castellanos Sector. (a) The Castellanos quartz diorite shows no inheritance and yields a crystallization age of 309 ± 3 Ma. The adjacent monzogranite crystallized at 307 ± 3 Ma and contains Cambrian–Ordovician, Ediacaran and one Palaeoproterozoic inherited zircon (not shown). (b) The Mercadillo granitoid, a small xenolith-rich stock, crystallized at 311 ± 3 Ma and includes abundant Ediacaran and minor Palaeoproterozoic–Archaean zircons, both discordant and concordant.

Another noteworthy feature is the contrasting behaviour of element pairs that typically correlate during magmatic processes, such as V–TiO2 and Tl–Rb. In Group II, these pairs show excellent correlations (R = 0.97 and 0.98, respectively), whereas in Group III, correlations are substantially weaker (R = 0.61 and 0.70), possibly reflecting the influence of boron metasomatism.

3.d. Sr-Nd isotopes

Bulk-rock Sr–Nd isotopic data are presented in Supplementary Table S3 (analytical methods in the Appendix). Sr isotopes are unreliable for constraining the origin of Álamo Complex rocks because their signatures have been modified by prolonged geological histories, intense deformation, repeated subsolidus fluid–rock interactions and high Rb/Sr ratios. In contrast, Nd isotopes are more resistant to post-magmatic alteration and therefore provide more robust constraints on source characteristics.

Depleted-mantle Nd model ages (TDM) were calculated using the age-dependent two-stage method of DePaolo et al. (Reference DePaolo, Linn and Schubert1991), which minimizes the influence of accessory phases (Bea et al. Reference Bea, Montero, Barcos, Cambeses, Molina and Morales2023) and exhibits only minor sensitivity to the crystallization age. For example, Álamo rocks yield mean two-stage model ages of 1.43 Ga, assuming an age of 480 Ma, and 1.46 Ga, assuming 600 Ma. Calculations employed λ = 6.542 × 10⁻12 a⁻¹ (Tavares et al. Reference Tavares and Terranova2018), depleted-mantle parameters 147Sm/144Nd = 0.21378 and 143Nd/144Nd = 0.513155 (Nägler & Stille, Reference Nägler and Stille1993; Nägler et al. Reference Nägler, Schafer and Gebauer1995) and CHUR values 147Sm/144Nd = 0.1966 and 143Nd/144Nd = 0.512638 (Jacobsen & Wasserburg, Reference Jacobsen and Wasserburg1980). Given the negligible difference in model ages, a representative crystallization age of 480 Ma was adopted, consistent with zircon ages of Cambrian–Ordovician rocks in Central Iberia (483 ± 3 to 477 ± 1 Ma; >20 massifs dated at the UGR SHRIMP facility).

The same age was used to calculate TDM for Ediacaran protoliths in order to assess whether they were sourced exclusively from Cambrian–Ordovician crust or also contain a juvenile component. Model ages computed at 600 Ma yield comparable results, but comparisons made at the time of anatexis are considered more rigorous.

All Álamo Complex rocks display similar Nd model ages of ∼1.4 ± 0.1 Ga, comparable to those of the Schist–Greywacke Complex and consistent with the average model ages of the Iberian Massif. These results indicate little or no juvenile input to the Álamo protoliths since at least the Late Neoproterozoic, implying a source dominated by reworked continental crust.

4. SHRIMP U-Pb dating

Zircon crystals from 29 representative samples of the Álamo Complex – including seven migmatites (ranging from metatexites through diatexites to leucosomes), twelve orthogneisses and ten leucogranites – were analysed using SHRIMP. The complete U–Pb dataset is provided in Supplementary Table S4, with analytical details reported in the Appendix. Prior to discussing individual rock types, we first compare the zircon age distributions of the Álamo Complex with those of the Schist–Greywacke Complex and the Ollo de Sapo Domain.

4.a. Zircon ages in the Schist-Greywacke Complex and the Ollo de Sapo Domain

Evidence from detrital SHRIMP U–Pb zircon geochronology indicates a maximum depositional age ranging from the Upper Ediacaran to the Lower Cambrian for the Schist–Greywacke Complex (Talavera et al. Reference Talavera, Montero, Martínez Poyatos and Williams2012), consistent with both the ichnofauna and the regional stratigraphy (Rodríguez Alonso et al. Reference Rodriguez Alonso, Díez-Balda, Perejón, Pieren, Liñán, López Díaz, Moreno, Gómez Vintanez, González Lodeiro, Martinez Poyatos, Vegas and Vera2004). This concordant dataset may have been derived from the ca. 2.6 Ga cluster present in low-grade metapelites. Grains older than 2.7 Ga are always discordant and are insufficient to define a discordia line.

Detrital zircons from a nearby low-grade shale in the Martinamor sector yield ages predominantly between 581 and 637 Ma, with subordinate Cryogenian and Tonian–Stenian populations, rare Palaeoproterozoic (∼1.9 Ga), Neoarchaean (∼2.6 Ga) and a few Mesoarchaean (∼3.2 Ga) grains (Figure 17a, b). The absence of Mesoproterozoic zircons supports a Gondwanan provenance for Central Iberia (cf. Nance et al. Reference Nance, Murphy, Strachan, Keppie, Gutiérrez-Alonso, Fernández-Suárez, Quesada, Linnemann, D’lemos, Pisarevsky, Ennih and Liegeois2008; Bea et al. Reference Bea, Montero, Talavera, Abu Anbar, Scarrow, Molina and Moreno2010, Reference Bea, Montero, Haissen, Molina, Lodeiro, Mouttaqi, Kuiper and Chaib2020; Chichorro et al. Reference Chichorro, Solá, Bento dos Santos, Amaral and Crispim2022).

Zircon crystals in the Ollo de Sapo gneisses typically exhibit Cambro–Ordovician rims (∼480 Ma) surrounding inherited Ediacaran or older cores (Bea et al. Reference Bea, Montero, Gonzalez-Lodeiro and Talavera2007; Montero et al. Reference Montero, Bea, Gonzalez-Lodeiro, Talavera and Whitehouse2007, Reference Montero, Talavera and Bea2017). The age distribution closely matches that of the Schist–Greywacke Complex, indicating a shared crustal heritage.

4.b. Pre-Ediacaran zircon crystals

Although less abundant, pre-Ediacaran zircons are present across Álamo samples. Wetherill concordia diagrams reveal distributions analogous to those of the Schist–Greywacke and Ollo de Sapo domains (Figure 17a, b). A distinct Tonian–Stenian peak is evident, with no true Mesoproterozoic zircons. A minor Orosirian peak (∼2.0 Ga) lies on a discordia, suggesting Pb diffusion (Bea & Montero, Reference Bea and Montero2013).

Between ∼2.2 and 2.7 Ga, the data display a continuum of concordant and subconcordant ages, indicative of metamictization and recrystallization in high-grade zircons (Halpin et al. Reference Halpin, Daczko, Milan and Clarke2012; Bea et al. Reference Bea, Montero, Haissen, Molina, Lodeiro, Mouttaqi, Kuiper and Chaib2020). This concordant sequence may have been derived from the ca. 2.6 Ga cluster present in low-grade metapelites. Grains older than 2.7 Ga are invariably discordant and insufficient to define a discordia line. The oldest analysed zircon grain, although discordant, likely exceeds 3.3 Ga.

4.c. Ediacaran and younger zircon crystals

Zircon crystals younger than 1.0 Ga across all lithologies display three major age peaks: (i) Ediacaran (∼600 Ma), (ii) Cambro–Ordovician (∼480 Ma) and (iii) Late Carboniferous (∼310 Ma) (Figure 17c). The latter peak is most pronounced in the Castellanos and Álamo sectors, although it remains subordinate to the older peaks.

4.d. Ediacaran migmatites

Five migmatite samples from Sierra de las Yemas, Mirueña and Castellanos (UMAP Group II) yield only Ediacaran or older zircon crystals. Of the 222 zircon grains analysed, 196 concordant or subconcordant spots define a polymodal Neoproterozoic cluster (164 analyses) and 32 older grains. Finite mixture modelling identifies three dominant Ediacaran populations: 549 ± 2 Ma (Ed1), 584 ± 3 Ma (Ed2) and 628 ± 3 Ma (Ed3), with a possible minor cluster at ∼643 Ma (Figure 18a).

The Ed1 population occurs either as rims of composite crystals or as homogeneous grains (Figure S1 c1, b4). The Ed2 population is the most abundant, comprising unrimmed crystals (Figure S1 a2, a3, d2, d3) and rims surrounding Ed3 or older cores (Figure S1 b1, b2, d1, e1, e2). The Ed3 population is primarily found in cores surrounded by Ed1 or Ed2 rims (Figure S1 b1, b3, e1). The spatial arrangement of rims and cores suggests multiple successive melting events acting on the same protolith.

4.e. Migmatized augen gneisses

In two migmatitic gneisses, 107 valid SHRIMP analyses reveal no Variscan ages. Instead, they identify 72 Cambro–Ordovician zircons, organized in a bimodal distribution (470 ± 3 Ma and 495 ± 11 Ma), together with 26 Ediacaran grains consistent with the migmatite clusters (Figure 18b; Figure S1 f1, 2–g3, 4). The Cambro–Ordovician ages are present in rims overgrowing Ediacaran cores (Figure S1 f1, 2, g3, 4) as well as in unrimmed crystals (Figure S1 f3, g1, 2).

4.f. Variscan migmatites

Two migmatite samples yielded Late Carboniferous zircons. A diatexite-like rock (sample MAX-1-5) contains exclusively Variscan zircon crystals (Figure S1 i11-3), dated at 308 ± 3 Ma, consistent with neighbouring appinitic intrusions of the Ávila batholith (Montero et al. Reference Montero, Bea and Zinger2004). Its cordierite-rich composition and zircon morphology suggest mafic magma–metasedimentary hybridization (Figure 18c).

The other sample (AMO 21-7) includes 37 low-quality zircon crystals. Among these, the Late Carboniferous zircons cluster between 284 and 309 Ma (discordant), interpreted as the age of migmatization. Most crystals are small and of uniform age (Figure 18c; Figure S1 h1, 2). A few grains yield older ages (1.9 Ga to Ediacaran), but their discordant patterns preclude robust interpretation.

4.g. Gneisses

Non-migmatitic orthogneisses display a major Cambro–Ordovician age peak (480 ± 2 Ma), accompanied by a secondary Ediacaran triplet corresponding to the Ed1–Ed3 populations (626 ± 11, 576 ± 12, 539 ± 6 Ma; Figure 19a). Cambro–Ordovician rims commonly surround older cores (Figure S2 a2; b1–4; c1,3; d2,3; g1,2; h1–4), while some zircons crystallized uniformly during this phase (Figure S2 a3; d4; h2). In a few instances, two Ediacaran populations can be observed within the same crystal, as illustrated in Figure S2 d1, where a 560 Ma rim envelopes a 640 Ma core. Ages older than Ediacaran were exclusively found in inherited cores (Figure S2 b1; c1; h4).

4.h. Leucogranites

Most leucogranites yield zircons with Cambro–Ordovician ages (474 ± 3 Ma) and significant Ediacaran components (587 ± 6, 618 ± 7 Ma), with occasional Cryogenian or Archaean grains (Figure 19b). In the Martinamor granite, only one zircon rim (out of 58 grains) yields a Late Carboniferous age (333 ± 3 Ma) over an Ediacaran core. This contrasts with Rb–Sr and Ar–Ar ages (∼293–310 Ma; Linares et al. Reference Linares, Pellitero and Saavedra1987; Bea et al. Reference Bea, Pesquera, Montero, Torres-Ruiz and Gil-Crespo2009), which are interpreted as reflecting differences in closure temperatures between the U–Pb zircon system and the Rb–Sr and Ar–Ar mica systems (Figs. 19c; S3 b).

Notably, the Ediacaran cluster is more prominent relative to the Cambro–Ordovician ages than in the gneisses. Ediacaran ages are mainly observed in restitic cores within Cambro–Ordovician rimmed grains (Figure S2 e4; f1, 3; i2 and Figure S3 a1; b1; c1; d1; d2; e1, 2, 3; f3) and less frequently in zircons of uniform age (Figure S3 a3; b3; c3; f4).

4.i. Variscan granitoids

A MTL leucogranite from Castellanos (sample CAS-13-7) contains small, irregular zircon crystals (Figure S3 j1–j3) defining a Variscan cluster with a mean age of 307 ± 4 Ma. The granite also hosts a few inherited Ediacaran zircons with ages around 611 Ma (Figure S3 j4–j6) and one Palaeoproterozoic grain. This rock is compositionally very similar to the Martinamor granite, seemingly representing a higher-temperature anatexis capable of generating melts able to dissolve and crystallize zircons.

The Castellanos monzogranite (sample MCR-9) yields concordant Variscan ages at 307 ± 3 Ma, together with inherited Cambro–Ordovician, Ediacaran and Palaeoproterozoic zircons (Figure 20). Variscan ages are mainly observed in long prismatic, unrimmed crystals (Figure S3 h1) and only rarely in rims (Figure S3 h2). Older ages occur exclusively in inherited cores (Figs. S10 h3, h4). The spatially associated quartz-diorite (sample CAS-11-16) contains only Variscan zircon crystals (Figs. S3 i1–i4), with an age of 309 ± 3 Ma, consistent within error with the monzogranite (Figure 20).

Finally, the granitoid (sample MER-21-1) contains a complex mixture of zircon populations, yielding a crystallization age of 311 ± 3 Ma (Figure 20). Inherited components include Ediacaran (22 grains; 605 ± 6 Ma), Cryogenian, Palaeoproterozoic (∼1.9 Ga) and a single Hadean grain (∼2.95 Ga) (Figure 21; Figure S3 g). The Variscan age cluster occurs mainly in uniform-age crystals (Figure S3 g1) and, to a lesser extent, in rims. Ediacaran and older ages are found in restitic cores (Figure S3 g2–g4) and uniform-age zircons. These Variscan crystallization ages are consistent with neighbouring Ávila Batholith granitoids (Montero et al. Reference Montero, Bea and Zinger2004) and display similar inheritance characteristics.

5. Discussion

5.a. Multiple anatectic episodes

The Álamo Complex records at least four significant episodes of crustal melting. Three of these occurred during the Ediacaran (∼628, ∼584 and ∼549 Ma), with a possible fourth event at ∼640 Ma (Figure 12a), under high-pressure conditions within the kyanite stability field. A later, lower-pressure melting episode is recorded during the Variscan orogeny (∼310–315 Ma). The Ediacaran age cluster is consistently observed across all analysed units, including Cambrian–Ordovician orthogneisses (Figure 12a, b) and leucogranites (Figure 13c). These signatures persist even in inherited zircon crystals of Variscan granitoids (e.g., Mercadillo and Castellanos monzogranites; Figure 14), despite thermal disturbance caused by entrainment in hot melts (Bea & Montero, Reference Bea and Montero2013). We interpret these Ediacaran ages as geologically meaningful rather than analytical artefacts, supported by the Almohalla orthogneiss with uniformly aged zircons at 543 ± 6 Ma (Bea et al. Reference Bea, Montero and Zinger2003) and the Aljucén gabbrodiorite at 580 ± 3 Ma in southern Central Iberia, which lacks inherited zircon components.

The occurrence of younger Ediacaran rims over older Ediacaran cores indicates repeated partial melting events acting upon the same protoliths – either granitoids or their sedimentary derivatives – with minimal juvenile input, as inferred from TDM model ages of ∼1.4–1.7 Ga. The two younger Ediacaran migmatization episodes (∼584 and ∼549 Ma) are clearly associated with the Cadomian orogeny, which involved crustal thickening and arc-related magmatism. These events are consistent with a collisional tectonic setting between continental blocks during the final stages of Rodinia’s break-up and the assembly of Gondwana.

In contrast, the older Ediacaran event (∼628 Ma) is typically linked to the Pan-African orogeny, which primarily affected the northern margin of Gondwana. While also involving crustal reworking, this episode is more closely related to extensive arc and back-arc processes, the closure of oceanic basins and subsequent continental collision. The preservation of Pan-African tectonic signatures in the Álamo Complex adds complexity to the region’s geodynamic history, indicating multiple overlapping tectonic events contributing to the final crustal architecture.

The presence of kyanite included within plagioclase in leucosomes of Ediacaran MX indicates high-pressure conditions in the Álamo Complex, comparable to other Ediacaran migmatites in the Central Iberian Zone, such as the Tormes Dome and the Ollo de Sapo Domain. These regions display similar zircon inheritance patterns and metamorphic conditions (Montero et al. Reference Montero, Bea, Gonzalez-Lodeiro, Talavera and Whitehouse2007; López-Moro et al. Reference López-Moro, López-Plaza, Gutierrez-Alonso, Fernández-Suárez, López-Carmona, Zieger-Hofmann and Romer2018). The Pan-African signature at ∼628 Ma, together with the younger Cadomian migmatization, highlights a protracted geodynamic history for this sector of the Iberian Massif, marked by multiple tectonic overprints and repeated crustal reworking.

By contrast, the Variscan episode (∼310–315 Ma) reflects a transition to lower-pressure conditions, consistent with crustal thinning, exhumation and the development of widespread anatectic domes. This Variscan melting event, recorded in the Álamo Complex and elsewhere in the Central Iberian Zone, represents a major tectonic reorganization that reworked pre-existing crustal structures.

5.b. Significance of the Cambro-Ordovician magmatism

Granitoids with Cambrian–Ordovician ages (∼482–465 Ma) dominate the Álamo Complex, and their zircon crystals frequently contain inherited Ediacaran cores, following the same three-peak pattern observed in the Precambrian migmatites. This pronounced zircon inheritance, a hallmark of the Ollo de Sapo Formation and related units, is likely linked to rapid melting and emplacement processes (Bea et al. Reference Bea, Montero, Gonzalez-Lodeiro and Talavera2007). Despite variations in texture, composition and mineralogy, the gneisses of the Álamo Complex and related rocks along the Galician–Castilian Lineament and Ollo de Sapo domain share several key characteristics: (i) a peraluminous nature; (ii) low Sr/Y ratios; (iii) comparable REE fractionation patterns and Eu anomalies; and (iv) identical zircon inheritance features. These similarities indicate a shared genetic origin, although the Álamo gneisses exhibit slightly younger ages (465–483 Ma), finer grain size and a predominantly plutonic character in contrast to the Ollo de Sapo units.

Zircon inheritance in the Álamo Complex shows a bimodal Ediacaran distribution, differing from the monomodal or trimodal patterns observed in the Ollo de Sapo and the Galician–Castilian Lineament (Talavera et al. Reference Talavera, Montero, Bea, Lodeiro and Whitehouse2013). Compared with these equivalents, Álamo lithologies are significantly enriched in Li, Rb, Cs, Sn and Pb. The tourmaline-bearing leucogranites display highly felsic compositions, low contents of Ba, Sr, REEs and high-field-strength elements (HFS), and unusually low Th/U ratios (∼0.3–0.6), nearly an order of magnitude below the continental average. Additionally, Zr/Hf ratios (∼35) remain constant even in the most evolved rocks, unlike typical magmatic differentiates. Eu anomalies range from negative to positive, particularly in the REE-poor MTL samples.

These features challenge the view that UMAP groups GIIIa and GIIIb represent evolved derivatives of GII orthogneisses. Instead, they are more consistent with low-temperature partial melts derived from GII or similar materials, likely influenced by B-rich fluids (see Section 5.c). Most zircon and monazite from the source remained in the residual phases during partial melting due to their low solubility in highly silicic, low-temperature, B-rich melts – the latter factor particularly affecting zircon solubility (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Zhu and Ni2025). The potential influence of B on monazite solubility remains to be verified experimentally, although preliminary results suggest a similar effect. Zircon retention prevented magmatic decoupling of Zr and Hf, while monazite retention produced melts depleted in U, Th, Th/U ratios and REEs. These melts display chondrite-normalized patterns with minimal Eu anomalies and a small but persistent negative Nd anomaly (e.g., Yurimoto et al. Reference Yurimoto, Duke, Papike and Shearer1990; Bea, Reference Bea1996).

Spatially, the Álamo Complex is associated with Sn and W mineralization, and rocks of Groups GI and GII are systematically richer in Sn and Li than equivalent lithologies from the Schist–Greywacke Complex or Ollo de Sapo.

Cambro–Ordovician magmatism in the Central Iberian Zone is linked to a rifting tectonic environment, a scenario supported by recent studies (Sanchez-García et al. Reference Sánchez-García, Chichorro, Solá, Álvaro, Díez-Montes, Bellido, Ribeiro, Quesada, Lopes, Dias da Silva, González-Clavijo, Gómez Barreiro, López-Carmona, Quesada and Oliveira2019). This rifting likely caused crustal thinning, facilitating partial melting of the lower crust and the generation of peraluminous melts, as observed in the Álamo Complex. The transition from Cadomian subduction to Cambro–Ordovician rifting remains debated and is beyond the scope of this study. Nonetheless, several features of the Álamo magmatism are inconsistent with a subduction-related origin: (i) absence of associated mafic rocks; (ii) felsic, peraluminous compositions unlike typical I-type subduction magmas; (iii) high B/Zr and B/Nb ratios, indicative of thickened crust or collisional settings (Leeman & Sisson, Reference Leeman and Sisson2002); and (iv) isotopic (Sr–Nd) and δ12O signatures (data not shown) pointing to long-lived crustal sources (Montero et al. Reference Montero, Bea, Corretgé, Floor and Whitehouse2009b). A fertile, radiogenic pre-Ordovician crust may have melted significantly at mid- to lower-crustal levels without major mantle input (Bea, Reference Bea2012). Consequently, the anatectic domain could have evolved largely independently of any underplated mantle-derived mafic magmas. However, it is possible that lithospheric extension during the Cambro–Ordovician modulated mantle upwelling and/or magma collection across the western European belts, explaining the synchronous occurrence of magmatic events.

5.c. Significance of tourmaline-rich rocks

Tourmaline-rich rocks are a distinctive feature of the Álamo Complex, where the metasedimentary sequence is enriched in B, Li and P (Pesquera et al. Reference Pesquera, Torres-Ruiz, Gil-Crespo and Jiang2005, Reference Pesquera, Torres-Ruiz, Gil-Crespo and Roda-Robles2009). During metamorphism and devolatilization, boron is progressively lost; consequently, its incorporation into anatectic melts depends on the thermal history and metamorphic grade of the source rocks, particularly the stability of boron-bearing phases.

The presence of muscovite under high-pressure conditions, together with both xenocrystic and newly formed tourmaline in Ediacaran migmatites, indicates that these minerals remained stable up to the onset of melting. Such stability likely limited boron loss during the pre-anatectic stages, facilitating its retention and subsequent incorporation into the melt. Consistent with this, B/Zr ratios systematically increase from migmatites to gneisses and leucogranites, rising from approximately 1.0 to values exceeding 10 (Table S1). These trends are interpreted as indicators of fluid mobility (Leeman & Sisson, Reference Leeman and Sisson2002), reflecting substantial boron mobilization and recycling during crustal reworking between the Cadomian and Variscan orogenies.

Boron enrichment is particularly evident in the associated peraluminous leucogranites, as demonstrated by the widespread presence of tourmaline. Tourmaline formation in granitic systems is primarily controlled by the boron content of the protolith, alongside the extent of partial melting and magmatic differentiation. These processes regulate boron concentration in the melt, which in turn dictates tourmaline stability. Although the activities of Al, Fe, Mg and Ti also affect its stability relative to other Al2O3-FeO-MgO (AFM) phases (e.g., biotite, cordierite), boron concentrations between 500 and 3000 μg g⁻¹ – depending on melt temperature – are generally required to achieve tourmaline saturation in granitic melts (Pesquera et al. Reference Pesquera, Torres-Ruiz, García-Casco and Gil-Crespo2013).

5.d. Variscan magmatism

Cambro–Ordovician magmatism ceased by ∼465 Ma, and Variscan anatexis began around 350 Ma during the Laurussia–Gondwana collision. This event produced granitoids of calc-alkaline affinity with minor mantle contributions, as well as B-rich peraluminous leucogranites chemically similar to their Cambrian–Ordovician counterparts.

Discrepancies between zircon U–Pb ages and Rb–Sr (or field-based) ages are a common feature in the Iberian Massif (Montero et al. Reference Montero, Bea, Corretgé, Floor and Whitehouse2009b; Bea et al. Reference Bea, Morales, Molina, Montero and Cambeses2021). Potential explanations include: (i) subsolidus alteration affecting the Rb–Sr system, and (ii) high melt fractions generated at relatively low temperatures that are insufficient to dissolve source zircons – particularly in the presence of external fluids. In highly felsic systems, such as the Martinamor leucogranite, elevated boron contents may depress the solidus, causing zircon under-saturation in the melt. Nevertheless, the system can remain sufficiently mobile to obliterate earlier structures, producing a body that appears late- or post-kinematic. Ongoing experimental work aims to test this hypothesis.

6. Conclusions

-

1. The Álamo Complex comprises six tectonometamorphic sectors, predominantly consisting of psammitic–pelitic MTS, gneisses, migmatites, leucogranites and tourmaline-rich rocks. These units record magmatic and metamorphic events spanning the Ediacaran to the Variscan, reflecting a protracted tectonometamorphic evolution.

-

2. U–Pb zircon dating identifies at least three Ediacaran migmatization events (549 ± 2 Ma, 584 ± 3 Ma and 628 ± 3 Ma) that occurred under high-pressure, kyanite-stable conditions, distinct from the lower-pressure Variscan migmatization (∼310 Ma).

-

3. Cambrian–Ordovician magmatism is widespread within the complex. Most gneisses and leucogranites from this period contain abundant inherited Ediacaran zircon cores, documenting repeated crustal reworking. These inheritance patterns closely mirror those observed in the Ediacaran migmatites.

-

4. Petrographic, geochemical and zircon inheritance similarities suggest a genetic link between the Álamo Complex, the Ollo de Sapo Domain and other portions of the Galician–Castilian Lineament, implying a shared geodynamic evolution over time.

-

5. The distribution and compositional characteristics of tourmaline-rich rocks indicate that Ediacaran materials were the primary source of boron. Remobilization during subsequent crustal melting led to polycyclic metasomatic processes within the region.

-

6. Variscan magmatism, particularly in the Castellanos and Álamo–Bercimuelle sectors, is recorded by small mafic and granitic intrusions, some of which are chemically evolved or locally contaminated. These intrusions are interpreted as satellite bodies of the Ávila Batholith.

-

7. Despite Variscan deformation, certain leucogranites, such as the Martinamor body, exhibit limited zircon dissolution and reprecipitation, thereby preserving older isotopic signatures. This preservation highlights the ability of some rocks to retain primary geological characteristics despite subsequent tectonometamorphic events.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756825100435

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Spanish National Plan Projects PID2020-114872GB-I00 and PID2023-149105NA-I00. We sincerely thank Michael Hartnady and Antonio Castro for their valuable reviews and insightful comments, which greatly improved the clarity and quality of this manuscript. This is IBERSIMS publication no. 123.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Appendix: Methods of study

Modal compositions were determined by point counting on two thin-sections perpendicular to the planar foliation and lineation of the rocks, respectively, using an electromechanical point counter and the reliability criteria of van der Plas & Tobi (Reference van der Plas and Tobi1965).

Rock samples (n = 165) including representative metasediments, migmatites, gneisses and granites were selected and analysed for major and trace elements by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and ICP- MS at the Activation Laboratories Ltd. (Actlabs, Canada). Boron was analysed by prompt gamma neutron activity.

Isotope Sr and Nd analyses of 20 representative samples of migmatites, gneisses and granites were performed at the Laboratory of Geochronology and isotope geology of the CIC-University of Granada (Spain). Samples for Sr and Nd isotope analyses were digested in a clean room using ultra-clean reagents and analysed by thermal ionization mass spectrometry (TIMS) in a Finnigan Mat 262 spectrometer after chromatographic separation with ion-exchange resins. Normalization values were 86Sr/88Sr = 0.1194 and 146Nd/144Nd = 0.7219. Blanks were 0.6 and 0.09 nanograms for Sr and Nd respectively. The external precision (2σ), estimated from the results of the last 10 replicates of the standard WS-E (Govindaraju et al. Reference Govindaraju, Potts, Webb and Watson1994), which is routinely analysed each 10 unknown samples, was better than 0.003% for 87Sr/86Sr and 0.0015% for 143Nd/144Nd. 87Sr/86Sr and 147Sm/144Nd were directly determined by ICP-MS (Montero and Bea Reference Montero and Bea1998), with a precision, estimated by analysing 10 replicates of the standard WS-E, better than 1.2% and 0.9% (2σ) respectively.

Zircon was separated using panning, first in water and then in ethanol. After eliminating the magnetic fraction from the concentrates with a neodymium magnet, zircons were handpicked under a binocular microscope and put in a SHRIMP megamount (Ickert et al. Reference Ickert, Hiess, Williams, Holden, Ireland, Lanc, Schram, Foster and Clement2008). Once mounted and polished, zircon grains were studied by optical and cathodoluminescent imaging, coated with a 10 nm thick gold layer, and analysed for U-Th-Pb using a SHRIMP IIe/mc ion microprobe at the IBERSIMS laboratory of the CIC-University of Granada, Spain. The SHRIMP U-Th-Pb analytical method roughly followed that described by Williams & Claesson (Reference Williams and Claesson1987), and is described in detail at www.ugr.es/ibersims. Uranium concentration was calibrated using the SL13 reference zircon (U: 238 ppm; Claoue-Long et al. 1995). U/Pb ratios were calibrated using the TEMORA-II reference zircon (417 Ma; Black et al. Reference Black, Kamo, Allen, Davis, Aleinikoff, Valley, Mundil, Campbell, Korsch, Williams and Foudoulis2004) which was measured every 4 unknowns, and crosschecked against the 91500 zircon (1065 Ma, Wiedenbeck et al. Reference Wiedenbeck, Hanchar, Peck, Sylvester, Valley and Whitehouse2004) everytime the analytical settings (e.g., duoplasmatron changed, detector sensitivity adjusted) changed, or against the OG1 zircon (3465 Ma, Stern et al. Reference Stern, Bodorkos, Kamo, Hickman and Corfu2009) if the analytical session included Mesoproterozoic or older zircons. When required, common lead was corrected from the measured 204Pb/206Pb, using the model of terrestrial Pb evolution of Cumming & Richards (Reference Cumming and Richards1975). Data reduction was done with the SHRIMPTOOLS software (downloadable from ∼www.ugr.es/∼fbea) using the STATA™ programming language. The crystallization ages are weighted average of 206Pb/238U ages if the discordance was ≤ 2%. The point-to-point reproductivility of the TEMORA-II standard were typically between 0.11% to 0. 40% for 206Pb/ 238U and 0.20% to 0.40% for 207Pb/206Pb.