INTRODUCTION

When writing about the landscape surrounding Novara, the western part of the Spanish Duchy of Milan, an anonymous chronicler did not leave any room for doubt. What unrolled before his eyes in 1584 was far from a bountiful arcadia: it was a desolated, ruinous, miserable, and unfertile scenery.Footnote 1 Water was tainted, population in decline. Illness befell herds and children. The chronicler attributed this dystopian view to the cultivation of rice. At the end of the Cinquecento, this crop started to appear as a food staple in the diet of various sectors of Italian society, from peasants in the countryside to aristocrats in the cities. It featured in banquets, especially in desserts such as the riso alla ciciliana (rice in the Sicilian manner) and riso alla turchesca (rice after the Turks) as much as in the soups that confraternities and charities offered to the poor.Footnote 2 Authorities responsible for food distribution in Milan, such as the Vicario della Provvisione (Deputy of the Magistracy of Provision), saw rice as a resilient crop with the potential to take societies out of periods of scarcity, complementing and substituting wheat and other major crops at times of bad harvest. Indeed, rice featured in food provisioning documentation and legislation, as well as in medical treatises, as an alternative for wheat in breadmaking, and as a means of enriching broth.

The crop was also attractive because it guaranteed high and quick yields in marshy areas that would otherwise have been left uncultivated, offering a reliable rate of return that allowed small and large landowners to amortize their investments.Footnote 3 The Duchy of Milan was characterized by the presence of large plains, cultivated with cereals such as wheat, rye, and millet. Though rice was not uniformly present throughout Northern Italy, recent studies, in particular by socioeconomic historian Matteo di Tullio, have highlighted that this cereal began to represent a significant percentage of the grains stored by the communities of various areas of the Duchy of Milan at the end of the sixteenth century.Footnote 4 This was, Di Tullio has noted, exactly when the import of rice from Asia became challenging because of the expansion of the Ottomans in the Middle East. It was this global constraint that prompted rice cultivation in other parts of Europe, including Northern Italy.Footnote 5 But rice was not at all new to Europe: it had been cultivated in other parts of the Italian peninsula and in Southern Spain, and from there exported to the Flanders, since the fourteenth century. Beginning in the fifteenth century, its cultivation had also been encouraged in the Ottoman Balkans, where it was seen as a symbol of state consolidation.Footnote 6

Studies in rural and economic history have already highlighted how the diffusion of rice farming in Northern Italy and the Po plain and the transformation of the landscape it engendered provoked multifaceted reactions from peasantry to small and large landowners.Footnote 7 These various social groups were forced to reorganize their ways of living—not only in terms of the management of local natural resources, especially water and soil, but also in terms of workforce procurement and contractual relations, and with regard to the cultivation of other crops such as wheat and, later on, maize.Footnote 8 Northern Italian rice fields mostly consisted of marginal and marshy, waterlogged areas that were repurposed over time by profiting from the nature of clay soil and the humidity of the climate.Footnote 9 Historian Luigi Faccini has made the longue durée claim that the hydrological changes introduced in the area in the twelfth century, meant to facilitate land reclamations, were key to the expansion of riziculture later in the sixteenth century. He argued that the creation of a tight network of river channels and the exploitation of natural underground water springs represented the “essential background” for rice cultivation and for a “capitalist transformation of agriculture.”Footnote 10 Such an association between hydraulic interventions, rice fields, and a capitalist management of the countryside had already notably been advanced by Fernand Braudel, who posited it as key to understanding the unequal wealth and land distribution in the lower plains of the Po.Footnote 11 More recently, this view of rice fields as a symbol of proto-capitalist ventures has evolved into a more nuanced understanding of the expansion of rice cultivation, focusing on how population growth contributed to the diffusion of rice farming, the transformation of dietary habits, and the change in relations among social groups.Footnote 12

The present article relies on this rich literature, fundamental to understanding the socioeconomic dynamics underlying the introduction of rice in Northern Italy. It departs from it, however, by reflecting not only on the vexed and frequently posed question of how rice was appropriated by several actors, but also on how these appropriations went hand in hand with ways of seeing the landscape and its improvement. Actors ranged from institutions managing the productivity of lands and food provisioning to members of the clergy and landowners, from reason-of-state theorists commenting on the dangers of wetlands to humanists writing about hydraulics, botany, agricultural practices, and breadmaking.Footnote 13 The paper relies on a set of documents concerning surveys conducted by Milanese magistracies on the novarese, between the 1570s and the 1580s, and reports of clergymen on contested areas. This latter genre of historical sources is given particular attention. Examining these anonymous documents in detail—paying attention to the language used and reading between the lines—allows the historian to unveil otherwise invisible aspects regarding the perceptions, fears, and reactions of individuals to the material changes caused by the inception of rice cultivation at the end of the Cinquecento. The sources used in this paper also bring to light the lives of those who were kept “out of sight” from the landscape, as Barbara Bender and Margot Winer put it—namely, the often-overlooked rice laborers.Footnote 14 Their contributions were frequently overshadowed by landowners and tenant farmers, the elite who left written records while petitioning Milanese institutions. These sources reveal the ecological dimensions of rice fields, and especially the way contemporaries recounted the spontaneous transformation of matter happening in stagnant waters. They shed light on what it meant to improve the environment, depicting rice cultivation as an ingenious, albeit immoral and wicked practice of land improvement. In sum, using these documents brings together the sources and methodologies of social history, especially of a history from below, with the questions posed by environmental history and the history of science about how early modern societies harnessed, conceived of, and appropriated natural resources.Footnote 15 The paper puts these local sources into dialogue with printed material such as medical and political treatises, diplomatic correspondence, contemporary legislation, and mechanical tracts to understand how rice and rice cultivation shed light on some broader, and often pressing, questions characteristic of early modernity. It also engages with intellectual history, by showing how the language of these anonymous reports resonated with larger contemporary debates regarding demography, territorial consolidation, and, more specifically, processes of population and depopulation, as they emerged in the writings of figures such as Giovanni Botero and Ludovico Settala.

Rice did more than respond to the “subsistence question”—that is, the process of finding means of guaranteeing the survival of the community.Footnote 16 Indeed, it was far from an exclusively instrumental resource. Rather, rice was what I term an ambiguous resource, a crop that was at once generative and disruptive, a plant that relied on processes of environmental amelioration and at the same time questioned them. Rice fields became possible because of the presence of hydraulic infrastructures resulting from land-reclamation and canalization interventions initiated in the late Middle Ages. They partook in a concept of improvement exemplified, in the early modern period, by the grand works of the English Fens, the transformation of marshes into cultivable lands under Henry IV in France, and the massive drainage operations in the Netherlands and the Venetian Republic.Footnote 17 At the same time, the practice of rice cultivation questioned the established equivalence between improving and draining. Rice economies revolved around mastering water: rice fields required frequent flooding, and were usually located in lowlands that could only possibly have been converted into drylands through significant investments in drainage projects, often financially inaccessible to small landowners. Contemporaries saw rice cultivation as a practice that increased wealth: rice was commercially relevant, as a cash crop in the domestic market and as an export commodity. The increasing prominence of rice in the economy of the region can be contextualized in the broader role that Milan played as a dynamic and prosperous commercial center, connecting Italy with Northern Europe.Footnote 18 This wealth, however, was also seen as the outcome of a selfish model of entrepreneurship, fostered by reckless individuals, and producing unprecedented environmental changes. While it is undeniable that other crops—the well-known wheat, the equally new potato, and the later-established maize—were also subject to symbolic, cultural, and immaterial projections, rice prompted more reflection on the disruption of morality and the natural order.Footnote 19

Rice certainly tapped into discourses of extractivism, commercial strength, and food self-sufficiency; it was represented as an important crop for sustaining a growing population that could no longer be fed on wheat exclusively.Footnote 20 Anthropologist Francesca Bray has brought to the fore how histories of rice intersect, on a global scale, with “the emergence of the early-modern world economy, and the global networks and commodity flows of industrial capitalism.”Footnote 21 Indeed, the history of rice exemplifies the early modern interdependence and entanglement of humans and nature, across technology, infrastructure, and embodied knowledge.Footnote 22 As will become clear later in this article, sixteenth-century agronomical treatises describing rice banks precisely unveil how human agency and labor relations shaped the transformation and conceptualization of natural elements such as soil, water, and crops in the early modern period.Footnote 23 More broadly, early modern discourses on rice and rice fields give insight into contemporary knowledge systems and the contribution of forms of visible, as well as invisible, labor, from the foreign and unnamed migrants of the plains of Lombardy to the enslaved Black African people who brought and acclimatized African rice varieties to North American and Portuguese soils.Footnote 24

The diffusion of rice also prompted tangible alterations in the landscape. This process coincided with a phase of extreme demographic fluctuation, following both a devastating Europe-wide plague epidemic and decades of warfare in Northern Spanish Italy, which caused significant depopulation in the last decade of the sixteenth century.Footnote 25 Contemporaries contended that rice turned dry lands into wet and inhospitable environments characterized by the presence of a foreign and waged workforce whose everyday conduct was incompatible with the principles of the Counter-Reformation. As the chronicler’s account featured at the beginning of this paper suggests, discourses on rice fields also held, in themselves, broader theological and political significance. The chronicler wrote in the 1580s, when Cardinal Carlo Borromeo (1538–84) was consolidating his Counter-Reformation agenda. As will be shown later in this article, he observed that rice cultivation rendered its workforce resistant to the practice of confession. Confession was the key institution of the Counter-Reformation and one of the pillars of Borromeo’s project to establish social control and mold a community of devout Christians. Even rice field–specific infrastructures such as the banks separating rice fields reflected this negative transformation of the landscape: contemporary chroniclers depicted these interstitial locations as places where rice field workers met sudden death, thus revealing the imbrication of ecological and “technological systems.”Footnote 26

The 1580s were years of extreme unrest in the Spanish monarchy, of which the Duchy of Milan was only a small, albeit key, part. As emphasized by Josep M. Delgado and Josep M. Fradera, “the Spanish Empire’s loss of the German states, as well as the Low Countries’ rebellion of 1568–1581…had catastrophic consequences for the monarchy in terms of its geopolitical position, finances, and legitimacy.”Footnote 27 These factors favored the development of reason-of-state theorizations, which were closely associated with projects focused on territorial consolidation and, most importantly, with demographic growth.Footnote 28 Rice cultivation, it appeared, posed a potential threat to these endeavors. Extracting rice from the soil not only unsettled and revolutionized the landscape. It also corrupted the souls of those who worked in or lived close to rice paddies. It altered their bodies. Even in the framework of early modern neo-Hippocratic medicine this crop was a peril. For example, high quantities of water were required to cultivate it. Water often stagnated, affecting the air, which in turn could provoke any number of physical ailments. Beginning in the 1570s, numerous gride (public decrees) and edicts establishing the distance between rice fields and inhabited centers were issued by the Milanese Magistrato di Sanità (Health board) and the Magistrato Straordinario (Extraordinary magistracy).Footnote 29 These official orders ruled that rice fields could only be located at a distance of six miles from the city of Milan; this minimum distance was reduced to five miles for smaller cities.Footnote 30 These distances were assessed and established by engineers, directly employed by these various magistracies. This legislation was also grounded in the medical conception that associated noxious air and vapors with the spreading of the plague. In the words of the anonymous chronicler, rice fields unrooted the original goodness (pristina bontà) of lands (terre) and engendered unruliness.Footnote 31

Recent scholarship in the history of science and art has revisited the concept of unruliness, applying it to scientific objects and using it to reinterpret depictions or narratives of landscape, where it has been deployed as a conceptual framework for understanding Aristotelian natural cycles of decline and renewal.Footnote 32 Indeed, early modern thinkers normalized unruliness, since it encompassed alterations and deterioration in the natural, sublunar environment. In the case of rice fields, however, unruliness was seen not as something exclusive to nature but rather as the outcome of human intervention, of sin and moral depravity. Cultivating rice was often regarded as an immoral choice, in that rice paddies degraded the soil. Accounts from the period describe paddy water infiltrating nearby fields cultivated with vines and other crops, and rotting their roots. Additionally, the presence of rice paddies impeded the cultivation of any other crop, and the deployment of human industria. Contemporary observers viewed rice and its waters as agents of contamination and deterioration, projecting this vision onto the landscapes of Lombardy.Footnote 33

This article is structured in three parts. The first briefly contextualizes rice cultivation in conflicts of jurisdiction and contemporary legislation. It also brings to light a special survey of the rice fields surrounding Novara, launched by the Spanish governor of the time, Carlos de Aragona, and conducted by the Magistrato Straordinario in 1584. This part examines the text of one of the manuscript documents contained in this survey in order to explore how rice was seen as an ambiguous and unruly resource, capable of unsettling the order of nature. The second part examines contemporary discourses that relate the presence of rice fields to processes of demographic decline, in particular as they emerge in the writings of reason-of-state theorist Giovanni Botero. The third part highlights how the waterscapes of rice cultivation attracted mechanical and medical practitioners, who respectively focused on rice fields as symbols of greed and disease. It explores how rice was contested even in debates on diet and breadmaking, and in humanistic, medical, and botanical texts as well as in legislation on grain provisioning.

SURVEYING DISORDERED AND UNRULY LANDSCAPES

In 1576, when writing to Cardinal Carlo Borromeo during a plague epidemic, the then governor of the Duchy of Milan, Antonio de Guzmán y Zuñiga, the Spanish Marquis of Ayamonte (1530–80), had to admit that gride establishing a distance between rice fields and cities damaged public revenues, because of their negative impact on the “gains brought about by rice commercialization.”Footnote 34 A promoter of anti-rice policies, Ayamonte argued that “public utility and health should prevail on private comodità,” and appealed to Borromeo in the hope that the cardinal would withdraw the edict he had himself issued in response to those of Milanese magistracies.Footnote 35 Borromeo’s decree aimed to safeguard the interests of local aristocracy and ecclesiastical orders, both of whom were landowners and his supporters. In the words of Ayamonte, the cardinal’s edict “reserved the right to determine and declare whether the lands are, or are not, suitable for producing anything other than rice,” a right that was supposed to be exerted by state institutions through civil law.Footnote 36 The entire controversy appeared in print at the end of the Cinquecento.Footnote 37 It included legal documents signed by the ecclesiastical judge in Milan expressing concerns about the interference and restrictions placed by secular authorities on the church’s properties, rights, and affairs. It also integrated a list of concessionaries who were allowed to cultivate rice by various Milanese magistracies, the edicts issued by the Magistrato Straordinario on rice fields and rice in the context of provisioning, and the governor of the Duchy of Milan’s rulings.Footnote 38

And yet, though rice triggered conflicts between secular and lay power, not even Milanese state institutions completely embraced the anti-rice edicts they themselves had issued. In a letter to the governor of the Duchy of Milan dating from 1596, the president of the duchy’s Royal Entrate Straordinarie (the institution controlling ports, rivers, and water channels) complained about the extremity of the punishments against landowners or tenant farmers who did not respect the distances between rice fields and cities, and proposed to limit penalties to fines, criticizing the use of corporal punishment, which had by then been introduced.Footnote 39 In the second half of the sixteenth century, rice also played a crucial role in sustaining the Spanish army, which was frequently in Lombardy for extended periods for military training or utilized the region as a layover during journeys to Flanders after the onset of the Dutch Revolt in 1567.Footnote 40 The relevance of rice in a military context is made explicit by the anonymous author of the chronicle on rice fields in Novara, who argued that the leading justifications for central institutions to relax the prohibition on rice cultivation around the city were directly linked to the presence of “continuous army quartering” and the imperative for tenant farmers to meet tax obligations.Footnote 41 Rice became a way to ease social unrest caused by wheat flour shortages and to help offset rising taxes from decades of war in the duchy since the fifteenth century. Also, part of the payments of rice laborers consisted in rice, a practice at the origin of a rural proverb in use in Northern Italy, riso paga riso (rice pays rice), as a later and compilatory early nineteenth-century source on rice cultivation reports.Footnote 42

Rice field legislation also aimed at regulating practices of labor procurement with the goal of putting an end to the abuses of the recruiters of rice laborers, who were known as capi de risaroli. Entrusted by landowners with the procurement of a seasonal labor force, the capi de risaroli were in charge of supervising the activities of rice cultivation and harvesting operated by laborers. At the time, the labor force for the cultivation of rice was represented by salaried workers who lived on the farms of their employers and had a somewhat stable occupation, lasting from a few months to a few years, as well as by day laborers, who came from the surrounding hills, mountains, and contiguous plains.Footnote 43 These two types of laborers worked side by side, though the former often lived in small and temporary dwellings built seasonally, following the harvesting of hay and rice. A contemporary edict issued in 1589 described the capi de risaroli as cruel and ruthless entrepreneurs who physically exploited workers as if they were “galley slaves,” beating them and withholding their wages and essential nourishment.Footnote 44 This grida followed a direct inspection of rice fields requested by the then governor of the Duchy of Milan and led by agents of the Magistrato Straordinario. It deprecated the capi de risaroli for attracting children and boys with promises and enticements, and established that it should be landowners (patroni de’ i campi) and their farmers who employed their workforce, paying them the same wage as if they worked in other fields and vineyards, “neither using violence against them nor forcing them to work when they fell sick, or when they could not work, because in this case it is enough to dismiss them, paying for as long as they served.”Footnote 45 The violence evoked in rice field legislation resonates also in the account provided by the anonymous author who depicted the countryside of Novara as a desolate landscape.

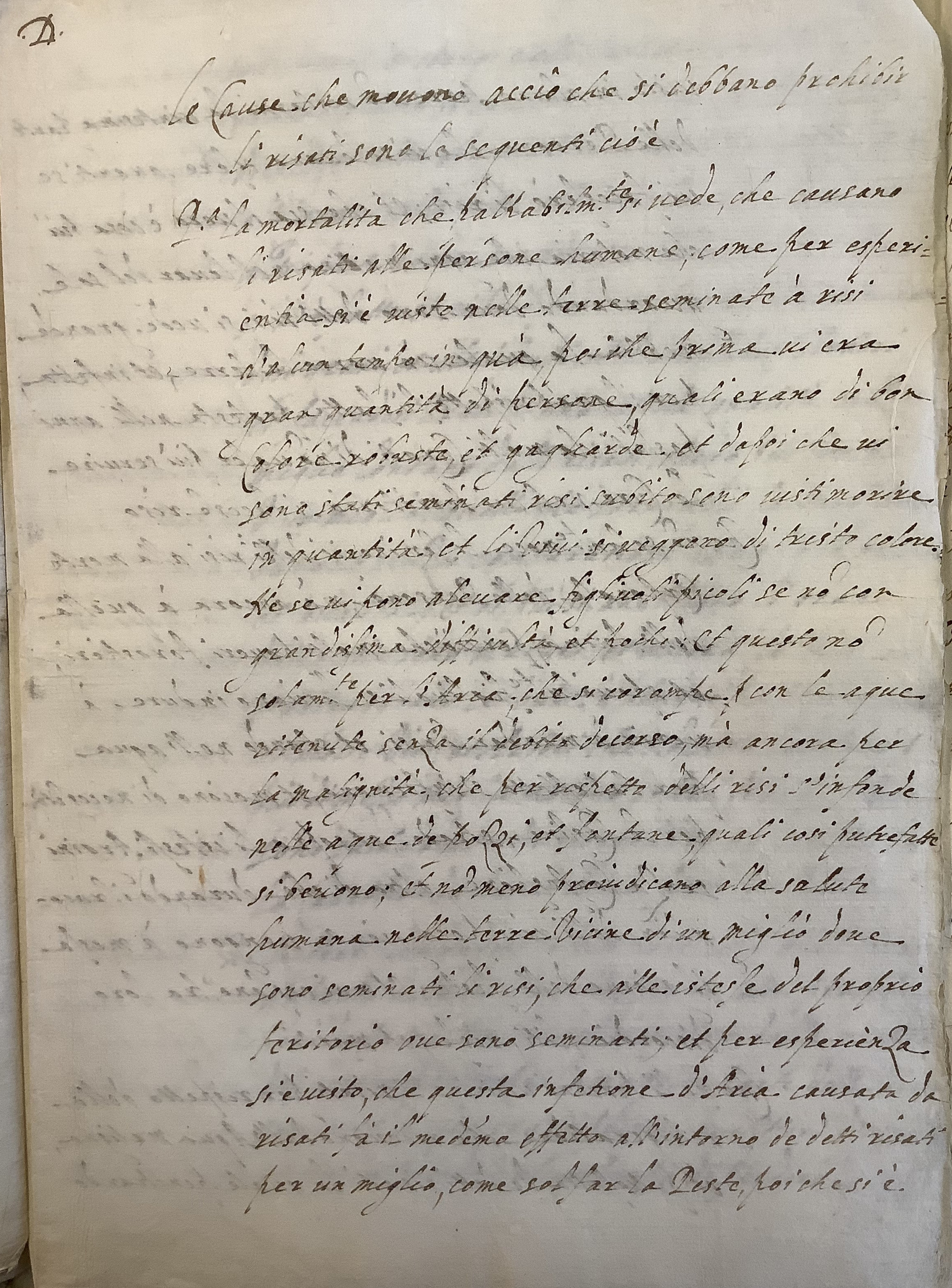

In his manuscript, titled Le cause che movono acciò che si debbano prohibir li risati (Reasons to prohibit rice fields) and appearing marked as D in the archival folder, the author recounted the reasons rice fields should be eradicated. This document was part of a larger survey that the Milanese Spanish government entrusted to the Magistrato Straordinario in order to gather information on the impact that rice cultivation had in various regions of the duchy, and in the surroundings of Novara in particular. This survey, which took place in 1584, was based on a series of written documents and a drawing by engineer Giovanni Battista Clarici (1542–1602).Footnote 46 As can be seen from the letter that one of the deputies of the Magistrato Straordinario sent to the Spanish governor of Milan, the documents on which the survey relied were marked as A, B, C, D, E. B and D were anonymous, while A, C, and E were signed.Footnote 47 A was a plea to preserve rice fields, written by one of the deputies of the Magistrato Ordinario, Scipione Gallarato, on behalf of a local landowner, Renaldo Tetone.Footnote 48 Tetone backed rice cultivation, claiming that his lands and the lands of his farmers would remain uncultivated (inculte) if not sown with rice. He claimed that those lands were cold and low and thus difficult to sow with other crops. Tetone also argued that the water of rice fields flowed freely, given that the countryside of Novara was rich in irrigation ditches (roggie). He thus dispelled the widely held belief that stagnant waters were the most evident feature of rice fields and that rice fields thus represented a threat to public health.Footnote 49 He kept the drawing made by Clarici in mind.

Clarici was no ordinary engineer. Indeed, the sixteenth-century Milanese artist Paolo Lomazzo (1538–92), in his Trattato dell’arte della pittura, scultura et architettura (Treatise on the art of painting, sculpture, and architecture, 1585) described him as “architect and taker of distances, heights, and depths of mountains, hills, and waters,” while the humanist Paolo Morigia argued that Clarici had made drawings of the entire city and Duchy of Milan, “with his measurements and distances, as well as the positions and numbers of cities, castles, villages, lands, towns, and farmhouses.”Footnote 50 Engineers were tasked with ensuring that all these edicts concerning distances between insalubrious places and inhabited areas were respected. Their measurements were sources of evidence in the conflicts that ensued between farmers, landowners, and state magistracies. By referring to Clarici to justify his positive opinion of rice fields, Tetone shielded himself behind an important, authoritative figure, while at the same time embracing a specific culture of knowledge. As we know from a sixteenth-century plea from engineer Giovanni Maria Robecchi to the Magistrato Straordinario, one of the primary duties of engineers was the regulation of water channels and the assessment “delas aguas, y siminteras de el aroz” (of waters and rice seedbeds), a specification that reveals the tight imbrication of water management, agricultural undertakings, and surveying endeavors.Footnote 51 Not everyone, however, held Tetone’s view on rice fields.

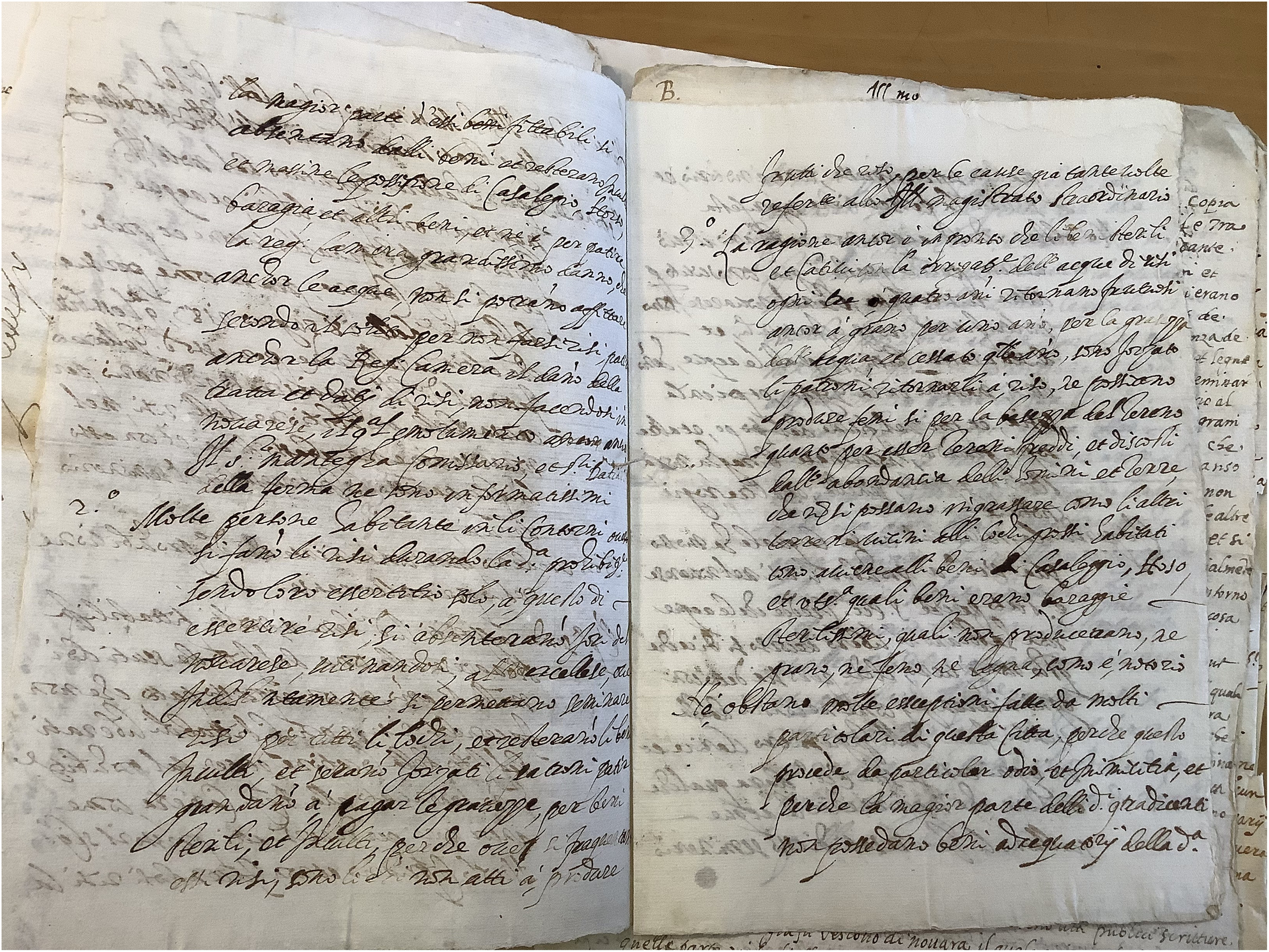

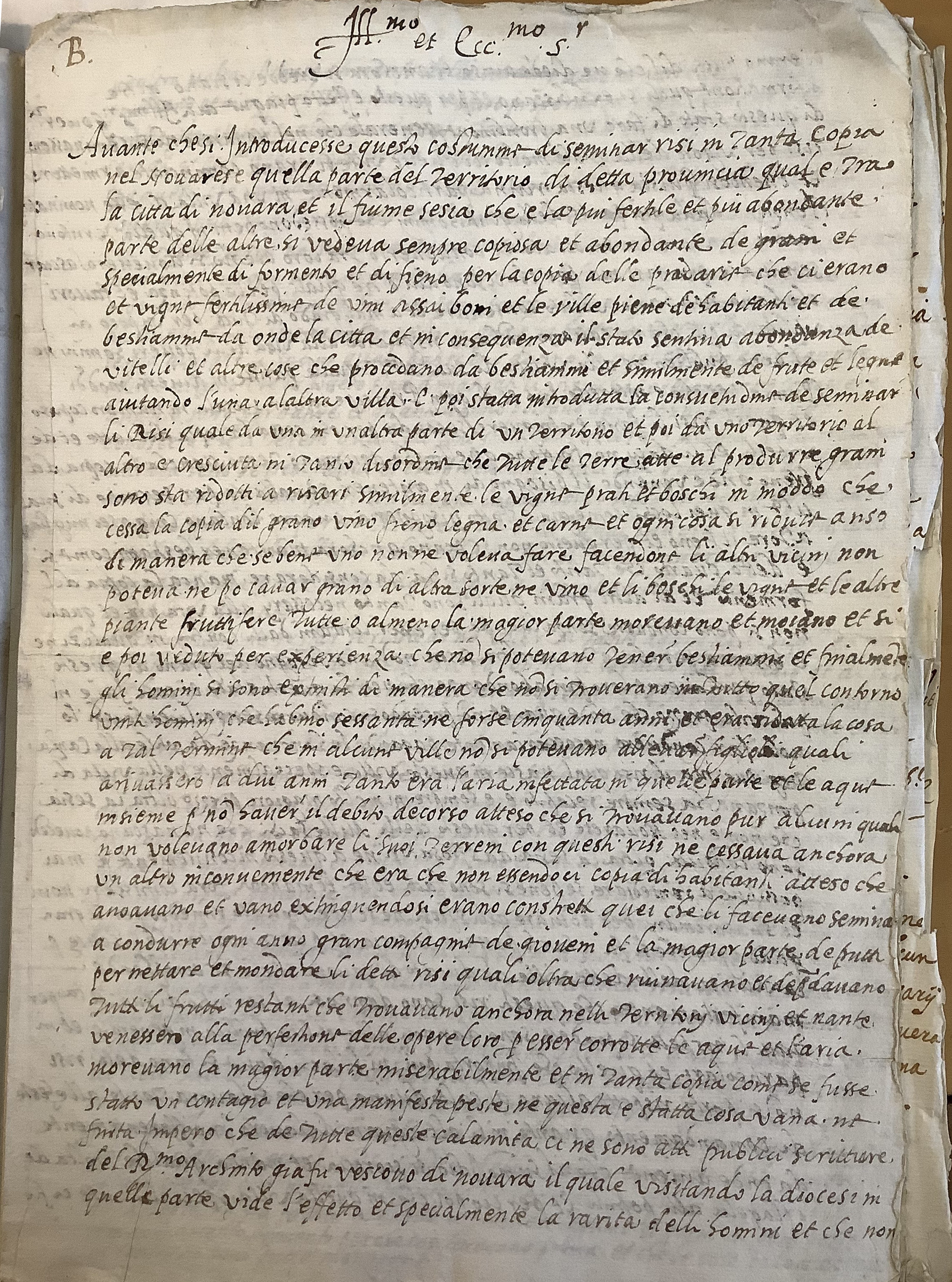

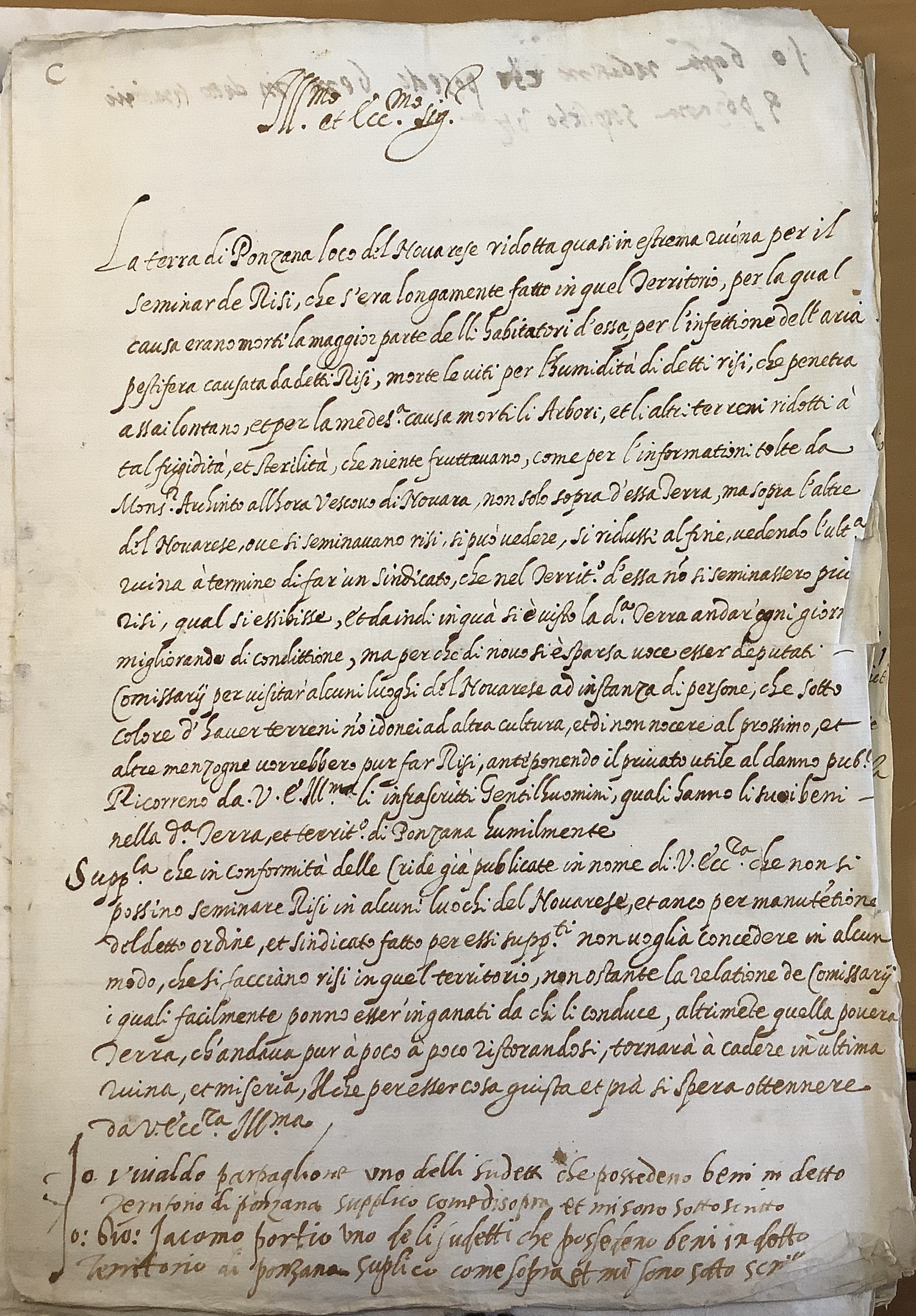

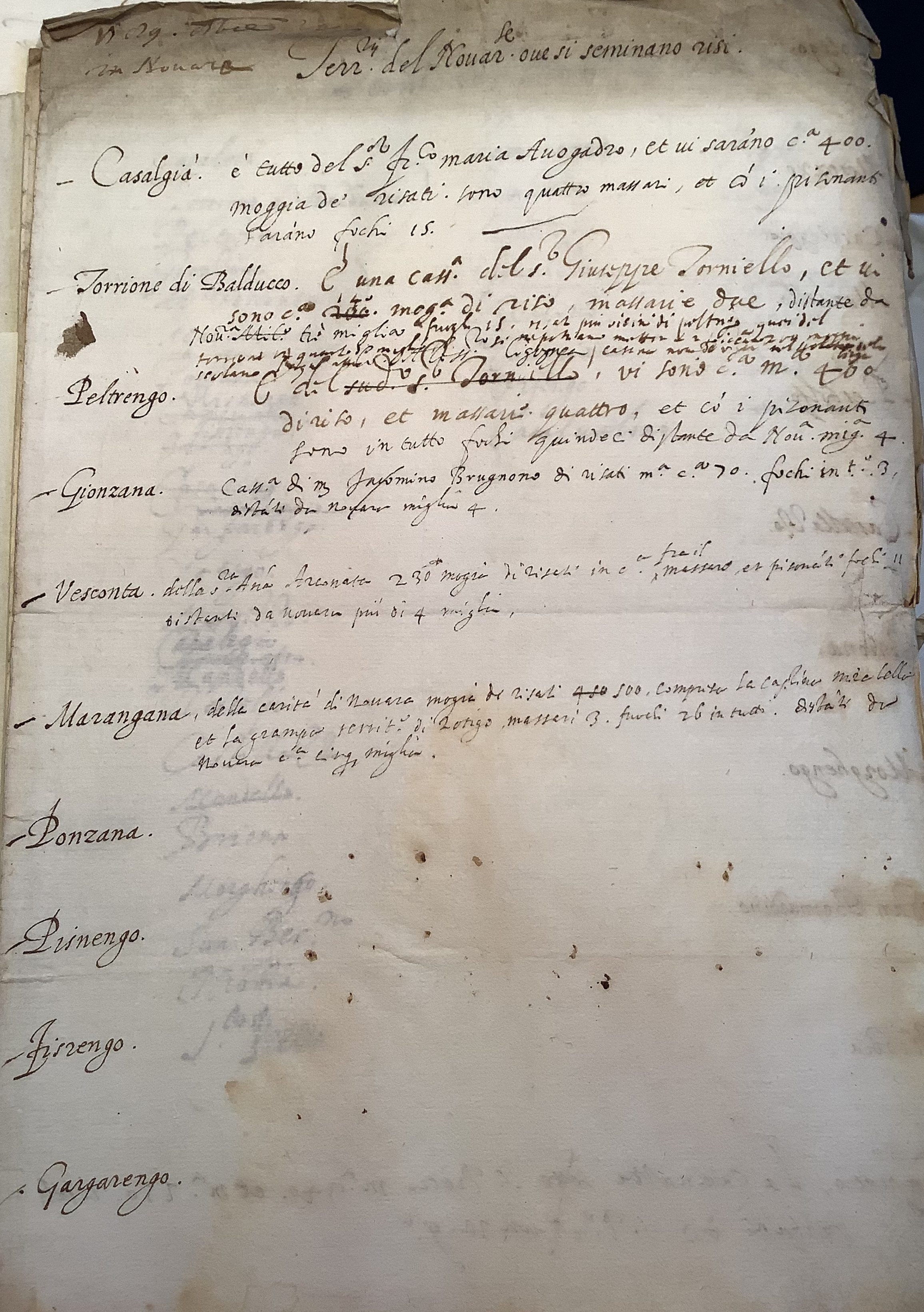

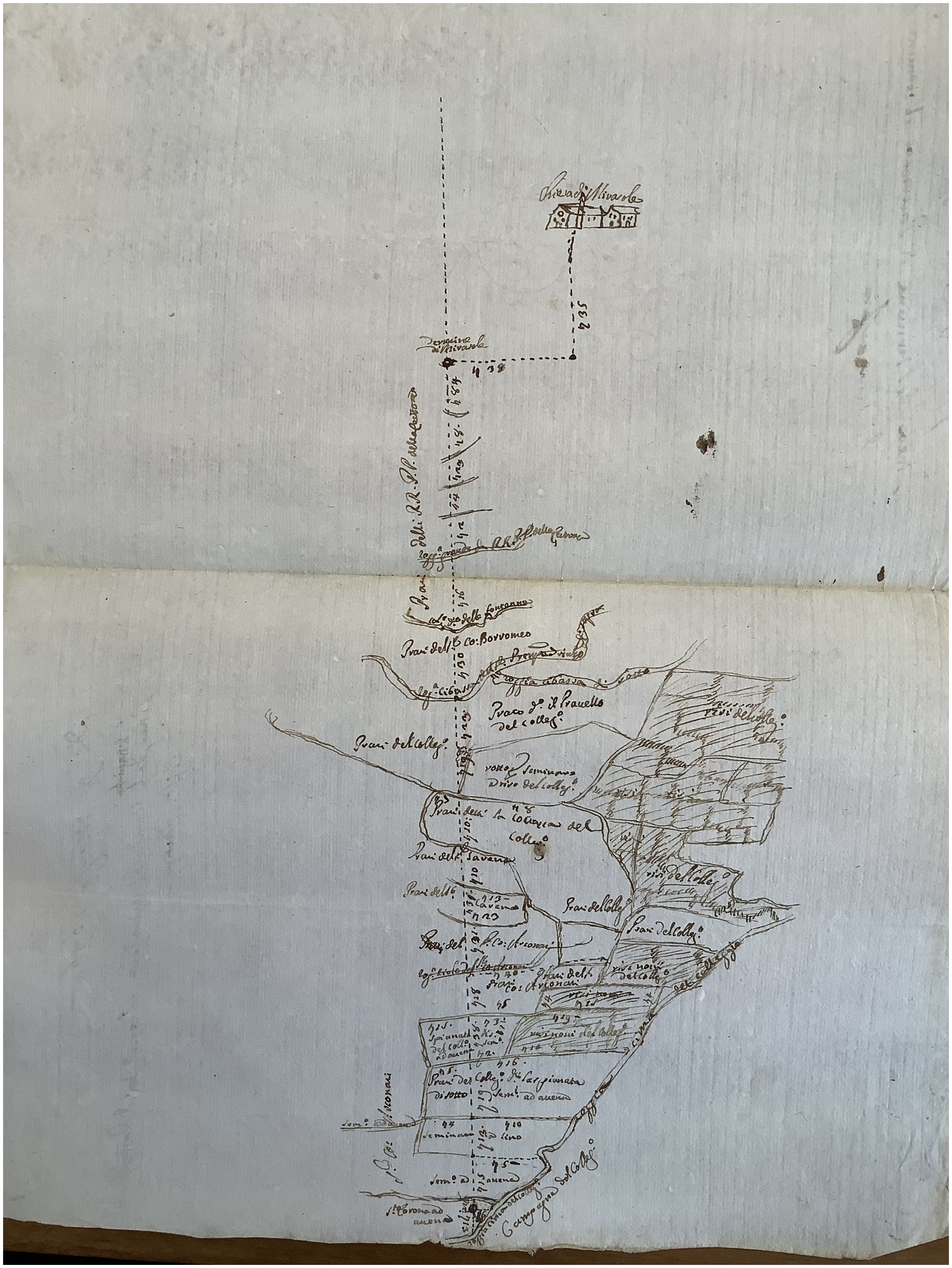

As document C shows, for example, local landowners appealed against him and others who invested in the cultivation of rice, calling for a medical assessment (document E) of air salubrity in areas proximate to rice fields.Footnote 52 The two anonymous documents, B and D, which will be extensively examined in the next section, detailed the reasons why rice fields should be extirpated. These two documents closely described geographical sites and their environmental characteristics. Though authorship cannot be established with certainty, their emphasis on theological and religious Counter-Reformistic ideas, as well as knowledge of curial visits of the Novara countryside, suggest that both authors might have been members of the clergy. The combination of documents that compose the survey testifies to how understandings regarding lands, resources, and productivity were flexible and constantly negotiated over time, reflecting beliefs, individual and group interests, and knowledge systems (figs. 1–4).

Figure 1. ASMI, Agricoltura PA 53, Document A. With kind permission of the Milan State Archive (permission number: 1679, 24/03/2025).

Figure 2. ASMI, Agricoltura PA 53, Document B. With kind permission of the Milan State Archive (permission number: 1679, 24/03/2025).

Figure 3. ASMI, Agricoltura PA 53, Document C. With kind permission of the Milan State Archive (permission number: 1679, 24/03/2025).

Figure 4. ASMI, Agricoltura PA 53, Document D. With kind permission of the Milan State Archive (permission number: 1679, 24/03/2025).

The 1584 rice fields survey was not the first of its kind. Indeed, it built on a survey conducted in 1575. Guided by agents of the Magistrato Straordinario, and based on the reports of landowners, clergymen, physicians, engineers, and land surveyors, the 1575 survey comprised lists of those territories in the surroundings of Novara that were cultivated with rice. These lists brought together information concerning specific locations, indicating the names of landowners, individuals, and religious orders alike, as well as the extent and yields of their rice fields (fig. 5).Footnote 53 They were the outcome of the note-keeping practices of members of thelocal administration, who interfaced with engineers (who practiced trigonometry, took measurements, and made calculations) as well as with landowners and farmers, who provided knowledge concerning the quantities of produce generated by their lands. These lists effectively embodied negotiated forms of social, administrative, and technical knowledge and reflected the practice of visitas generales in Spanish American territories, inspections with the aim of collecting information regarding taxation, demography, and natural resources in the Spanish Crown’s overseas domains.Footnote 54 In the context of rice fields, record-keeping methods were developed to gather data about a highly valuable resource, crucial for both internal and external trade. Simultaneously, however, these practices aimed to manage the inherent disorder associated with rice cultivation, while also securing territorial and political control.Footnote 55

Figure 5. ASMI, Agricoltura PA 69, list of rice fields around Novara (1575). With kind permission of the Milan State Archive (permission number: 1679, 24/03/2025).

According to the author of document D of the survey, the region surrounding Novara, initially home to a thriving population, experienced a significant demographic decline following the introduction of rice cultivation. From the author’s perspective, the cultivation of rice, unlike other agricultural endeavors (such as planting wheat, vines, and other trees), did not fall into the category of an industrious and productive activity and rather led to the detrimental and unruly transformation of lands and their surroundings. The farther away lands cultivated with other crops were from rice fields, the more hope locals had that these cultivations would survive. Once fertile and capable of producing “everything” (ogni cosa), land cultivated with rice was corrupted and overrun by uncontrolled organic growth. The anonymous chronicler explicitly attested to this transformation, recounting its visible aspects and arguing that “every morning, at sunrise, looking toward where the rice is planted, one sees thick fog moving toward the lands, infecting them.”Footnote 56

The cultivation of rice carried with it a symbolic association with disorderly, ungodly forces and the potential for living organisms to spontaneously emerge from decomposing substances. This idea posed a challenge to the prevailing belief that the origin of life and living entities could be explained only by the intelligent intervention of a higher power.Footnote 57 In the account, the process of spontaneous generation itself was portrayed as caused by the infiltration of contaminated water that penetrated surrounding fields, destroying their produce. In the words of the anonymous author: “The malignant and rotten water of rice fields broadly percolates underground in the lands nearby and, through a cooling process (refrigeratione), it causes worms, zuchette (as they are called), and other animals that damage wheat, vineyards, forests, hay, and other produce, as can be seen on the basis of past and present experience.”Footnote 58 In this brief description, the author elaborated on the ecology of rice fields as sites where water, through a process of putrefaction, and under the right environmental conditions, produced animals—in particular, pests such as worms and zuchette. Zuchette was a local term for what two centuries later would have been called gambero da terra, or, in eighteenth-century Linnean classification, Gryllotalpa vulgaris (1758), in English known as the cricket mole.Footnote 59 Burrowing underground, zucchette destabilized the soil, eating plant roots and creating tunnels that reached nearby crops, such as vines. Contemporary sources argued that, since the water of rice fields often stagnated even when it was meant to flow slowly, it corrupted the air, at the same time reaching and contaminating the water of wells and fountains, which then became undrinkable and poisonous.Footnote 60 The water of rice fields also allegedly caused more generally devastating effects, with adverse reverberations for the entire duchy.

In the words of the author of another document contained in the survey, document B, rice was a disaster, a real calamity (calamità).Footnote 61 The more rice cultures expanded, the more other cultures, such as wheat, hay, and vines, as well as wood and meat production, ran short in terms of supply. Others referred to rice as a form of ruination of the landscape (ruina), and to its waters as corrupt (putrefatta) and malign (maligna); by contrast, lands liberated by rice fields were described as fertile (fertile), fructiferous (fruttifera), and characterized by abundance (abbondanza) and by a great quantity of vassals (vassalli), highlighting the political dimension of discourses on anthropogenic transformations of nature. Other contemporary accounts, for example in the form of petitions to the Magistrato Straordinario from landowners such as Rinaldo Parpaglione and a Giacomo Portio (document C), also emphasized the extreme ruination (estrema ruina) of lands when they began to produce rice, attributing the death of city inhabitants to the pestiferous infection caused by stagnant water, and the death of vineyards to the humidity produced by rice fields.Footnote 62

Petitions to extirpate rice fields reveal how contemporaries interpreted the transformations in the landscape as the outcome of human action, and how they attributed an important weight to the influence of environmental factors on the human body. Ricescapes were not usual landscapes but special sites that brought to the fore the fact that natural causes and human agency coexisted and were codependent. To put it in the terms of the recent historiography on cropscapes, they were “assemblages” of humans, materials, environmental factors, and technologies “formed around a crop”—in this case, around rice.Footnote 63 Rinaldo Parpaglione and Giacomo Portio, the two landowners criticizing the diffusion of rice cultivation, argued that rice fields were the result of the greed of other proprietors. They accused such landlords of being too concerned with their private interest and of only seeing rice as a good investment to maximize their profits. Parpaglione and Portio defined such individuals as “people who prioritized individual gains over the public good.”Footnote 64

And yet, once created through such individually motivated human intervention, the ecosystem of rice fields acquired an agency of its own, and allegedly became itself a cause of moral corruption, endangering the power of the state and the church. This resulted from a combination of natural, environmental elements and the attendant organization of labor. As highlighted in the previous section, rice workers were compelled to toil at unsustainable pace, enduring both physical and moral deterioration. The author of document D also explained that rice workers did not have time to go to church on Sundays. Furthermore, he asserted, they often died while working on site, and their dead bodies were found in the vicinities of their dwellings, in the streets, and on the banks separating rice fields. This way of dying was theologically problematic, since it made it impossible to access confession on the deathbed.Footnote 65 In some cases, confession was not an option in the everyday life of the communities surrounded by rice fields. The same account also described the dioceses serving those communities as deserted, since clergymen did not want to dispense their pastoral care in those regions. The author went even further, claiming that the fact that many rice field workers often could not respect festive days might provoke God’s anger, and that the communities would run the risk of receiving his curses (flagelli). This was one of the reasons—the same author claimed—that landowners such as Rinaldo Parpaglione and Giacomo Portio begged authorities to eradicate rice fields. The author also reported the outcome of a pastoral visit paid by the recently appointed bishop of Novara, Romolo Archinto (1533–76), between 1574 and 1576, during which the bishop witnessed the severe depopulation of the region.Footnote 66 In sum, the motivations to remove rice fields mentioned in the various documents composing the survey of the Magistrato Straordinario were at once material and moral. As the author of document D underlined, “rice was harmful because it provoked the corporeal death of people, as much as the death of their soul.”Footnote 67

RICE, MEDICINE, AND INDUSTRIA

The medical and demographic concerns highlighted by the author of document D can be placed within the broader framework of public health issues and the theoretical discourse on territorial consolidation, in particular the writings of physician Ludovico Settala (1552–1633), reason of state theorizer Giovanni Botero (1544–1617), and agricultural writer Agostino Gallo (1499–ca. 1570). As to medical concerns, the management of rice fields was not only at the center of the preoccupations of the Magistrato Straordinario but also a principal concern of the Magistrato di Sanità. Following the humanistic medical readings of the Hippocratic corpus, and of On Airs, Waters and Places (AWP) in particular, the medical community saw the stagnant waters of rice fields and their effect on air quality as a root of disease transmission. This is why rice fields figured among the sites whose salubrity, or lack thereof, physicians had to assess. As part of the Magistrato Straordinario survey in 1584, three members of the Novara College of Physicians, Serafino Reveslati, Giovanni Battista Valente, and Gaspar Chiappa were summoned to visit rice fields around Novara. They decreed that rice could be cultivated on the condition that rice fields were one mile from cities. Most importantly, they shared their observations on water flows. They claimed that “as long as the water of rice fields ran freely, unstoppable, and rice fields did not turn into marshlands, they could cause very little damage to the air and universal human health, in particular when they did not occupy a large space.”Footnote 68 Physicians were fundamental in processes of decision-making, especially in magistracies such as the Magistrato di Sanità and the Magistrato Straordinario. They were called to assess environmental dangers and potential public health threats such as cesspits or manholes emanating foul air, cisterns, marshes, and stagnant waters.Footnote 69

In the course of the sixteenth century, the Hippocratic AWP received much commentary, including from the Milanese physician Ludovico Settala. Serving as medical deputy during the Milan plague epidemic of the 1570s, Settala centered his explanation of plague and disease transmission on noxious vapors, thereby distancing himself from theories involving seeds and corpuscles.Footnote 70 In his Latin commentary on AWP, published in Cologne in 1590, Settala dedicated extensive sections to water in different states, and to stagnant waters in particular. He claimed that stagnant waters were recognizable because of their unpleasant (ingratus) and slimy (limosus) taste, putrid odor (putrido odore), and dark color (colore atro).Footnote 71 If ingested in the summer, stagnant waters affected the stomach, while in the winter, descending slowly in the bladder, they provoked pleurisy.

Settala drew a connection between stagnant waters and the female womb. He argued that, just as humidity jeopardized fertility in women, stagnant waters prevented the seeds of cereal plants from rooting.Footnote 72 Settala projected a specific, marshy landscape onto the female body, thus relating neo-Hippocratic medical knowledge with contemporary discourses regarding soil fecundity, as well as processes of population and depopulation. Although the many anonymous authors of the 1584 survey did not make explicit reference to neo-Hippocratic medical theories, they brought together ongoing ideas about the material environment of rice fields, and their implication for the preservation of moral and political order.

The demographic decline witnessed by the various individuals writing about rice fields also evoked an even broader and more pressing concern for a sixteenth-century state such as the Duchy of Milan: the loss of control and mastery over the state’s territories and their natural resources, including its population. The author of document B argued that one of the reasons in favor of the removal of rice fields was “to have vassalli in copious number, because rice extinguishes them.”Footnote 73 Another document commented on the fact that rice “interrupted the wealth of wheat” and provoked a rarità degli homini (scarcity of humans). And in a short, later memoir, the bishop of Novara wrote that he had learned that in ten days thirty-three men had died all of a sudden in Novara, “without help, neither spiritual, nor temporal.”Footnote 74 Relying on contemporary birth registers, he argued that only one twentieth of the original population of regions cultivated with rice survived, comparing the effects of rice to the impact of plague outbreaks in communities.

Population started to emerge as a key factor in contemporary discourses on reason of state, and in particular in the theorization of Giovanni Botero. Counselor to the archbishop Carlo Borromeo in Milan, and writing at the time of the consolidation of the Spanish overseas empire, Botero was the first theorist of reason of state who attributed centrality to the economic, wealth-producing, spatial, and industrial (as in human industria) dimension in the constitution of the greatness (grandezza) of the state, and to the function of knowledge and science in exerting power.Footnote 75 Recent literature has emphasized that Botero offered a new perspective on the concept of reason of state, rethinking the political landscape by merging the protection of Christendom with the challenges of an evolving statehood at a time of religious conflicts and an expanding global order.Footnote 76

According to Botero, a flourishing and growing population (gente) represented a state’s true strength (vere forze).Footnote 77 This is because it was only through human industria and ingegno that the environment was transformed, waters tamed, marshes reclaimed and drained, and commodities traded through river channels and by sea.Footnote 78 In his Delle cause della grandezza delle città (On the causes of the greatness of cities, 1588), Botero emphasized the importance of population and industria in bolstering the state’s economy. He argued that genuine wealth was found not in mines abundant with precious metals but, rather, in the labor of people who cultivated the land, processed raw materials, and engaged in trade.Footnote 79 He praised knowledge of nature and natural resources, of geography and demographics, as of paramount importance in practices of statecraft, and emphasized the significance of princely involvement in improvement initiatives, such as “draining marshes, clearing and cultivating unproductive forests, [and] supporting and assisting those interested in investing in these endeavors.”Footnote 80 In his later work, Discorso intorno allo Stato della Chiesa (Discourse on the state of the church, 1599), Botero also addressed issues related to river floods and stagnant waters. Focusing on projects to divert the river Aniene to purify Roman air, he praised the orderly nature of rivers and dikes, opposing them to the unruly nature of floods and the stagnant waters they produced. He emphasized that reclaimed lands, where rivers and waters flowed freely, were inhabited by active and industrious communities, while marshlands were portrayed as marginal areas: “peasants fall ill, afflicted by noxious air and soil, by the heat of the sun during the day, and by the cold of the moon during the night.”Footnote 81

In line with Botero’s approach, and as locations dominated by still waters, rice fields were sites posing a tangible threat to the fundamental texture of society, namely human industria. Contemporaries, however, did not see this process of devastation as necessarily irreversible. Rice fields could be destroyed, and their lands made generative of many a crop. This “reverse” transformation is also evoked and confirmed in another section of the account of one of the anonymous chroniclers: “Although it may seem that removing rice cultivation results in the land not immediately producing as well as before, this is due to the harmful effects of rice rather than the quality of the soil. Indeed, most of the lands previously used for rice cultivation were once fertile and capable of producing abundant crops. Furthermore, given some time to rid themselves of the negative effects caused by rice cultivation, these lands will return to their former fertility. This was exemplified in the Brandina province of Novara, where, after the inhabitants voluntarily ceased rice cultivation, the land began to yield various crops marvelously.”Footnote 82

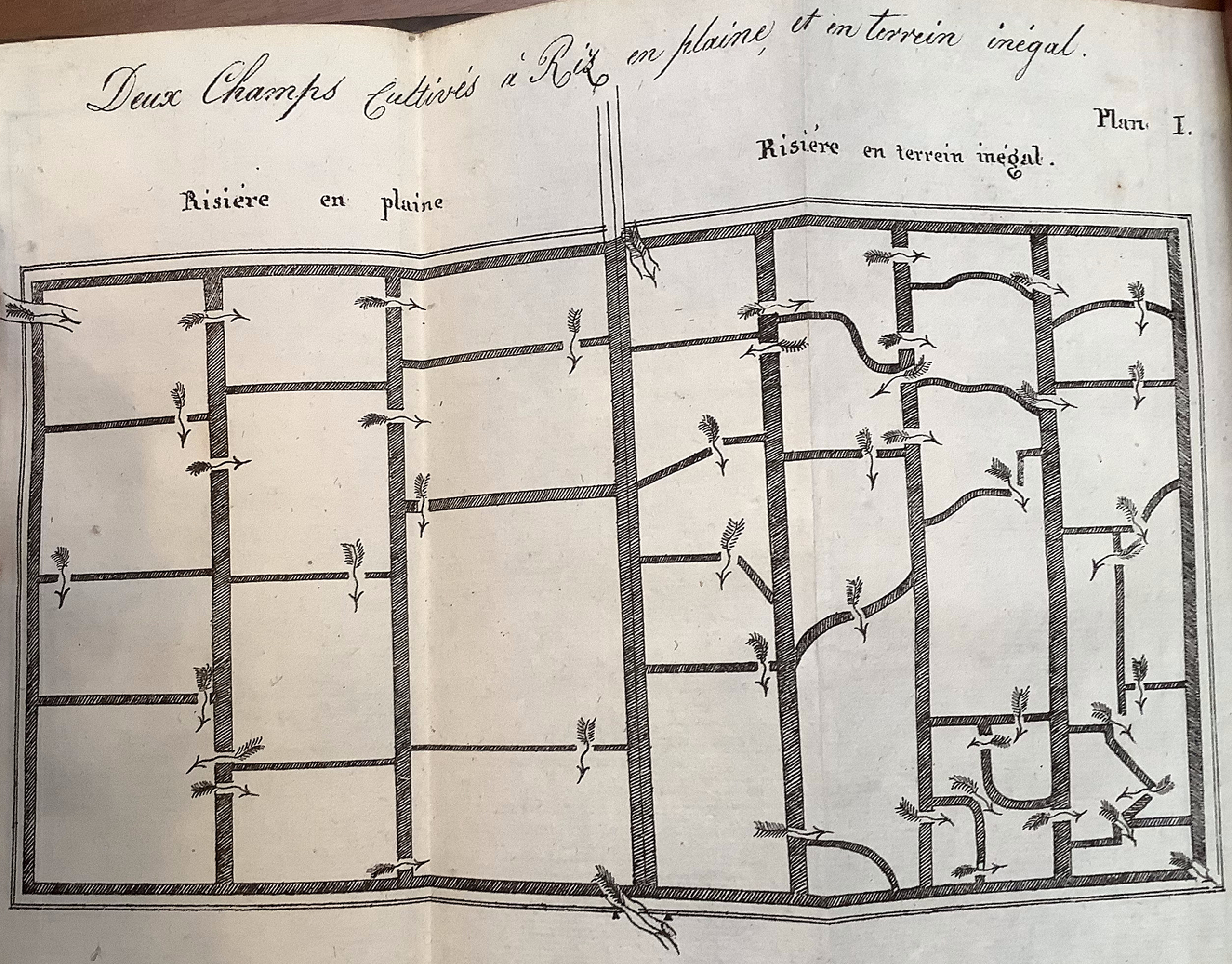

This last observation reflects contemporary rice cultivation patterns, exemplified by the agricultural writer Agostino Gallo, in his Le Vinti giornate di agricultura (The twenty days of agriculture, 1569). Gallo explained that on the Northern Italian peninsula rice could be cultivated in the same slot of land for two or three consecutive years. He did not make any reference to the many figures involved in growing rice, such as the multifarious migrant workforce or the capi de risaroli, roles that instead are described in rice-related legislation and manuscript reports. He rather referred to an abstract “agriculturalist,” and underlined that cultivating rice required a particular commitment in terms of procedural organization and knowledge distribution.Footnote 83 Even though rice workers are invisible in Gallo’s account, they were at the center of the manual practices described, evidence thus of the exchanges between humanist culture and vernacular knowledge.Footnote 84 According to Gallo’s analysis, when rice was growing, rice workers attended to the cultivation of the crop by making sure that water remained at the same level of “two fingers,” and that it kept flowing.Footnote 85 Water flows were ensured by the disposition of rice field banks (fig. 6). Most of those followed the inclination of the land plot, while two banks were disposed transversally, marking the beginning and the end of the rice field. Rice fields were thus structured in imperfect squares, connected to each other through passages that allowed water to keep streaming (fig. 7). Rice to be sown usually arrived in big sacks and unhusked. A common practice was to immerse the sacks directly in the water of plots. Rice workers would then tear them up to sow the grains as soon as they started to sprout. They paid tactile attention to the texture of the grains, drying the water once they realized the grains had softened too much (quando s’immorbida troppo il riso).Footnote 86 Finally, rice workers let the sun dry rice ears, and reintroduced water for their final sprout. Managing and enclosing waters were one of the main concerns of sixteenth-century states, which consolidated their power through the creation of hydraulic infrastructures. These included creating networks of water channels to transport commodities, controlling river banks to prevent floods, and implementing irrigation techniques, efforts that also led to a progressive mathematization of water knowledge.Footnote 87 Keeping the banks clean and steady was one of the priorities of rice laborers. However, as contemporaries reported, banks often broke under water pressure, and water invaded nearby roads. Indeed, as Carlo Poni has highlighted for small-farm agriculture in the central-eastern part of the Italian peninsula, the practice of constructing ditches and regulating water flows—as well as the repurposing of the organic waste and soil accumulated in ditches as fertilizer—reflected a broader early modern drive toward the rationalized use of natural resources and space.Footnote 88

Figure 6. ASMI, Agricoltura PA 65. Sketch with rice fields banks, end of the seventeenth century. With kind permission of the Milan State Archive (permission number: 1679, 24/03/2025).

Figure 7. Gaspare Antonio de Gregory, water flows, as depicted in Solution du problème économico-politique concernant la conservation ou la suppression de la culture du riz (Turin, 1818). With kind permission of the Académie d’Agriculture de France.

RICE, WATER, AND BREAD

Rice fields catalyzed ways of thinking about strategies of water control and distribution. These featured in the appeals to Milanese magistracies of self-proclaimed “inventors,” such as Giuseppe Ceredi (1520–70) from Piacenza, who looked for patronage and sponsorship for his water machine. More specifically, in 1565, Ceredi sought support from Milanese magistracies for his device (stromento) designed to “draw water from royal and navigable rivers, as well as lakes, ponds, and areas with abundant water collection, in a quantity sufficient to irrigate the lands as needed.”Footnote 89 He asked to have his device patented so that “no one could draw water to irrigate lands…without paying as much as the inventor will consider honest.”Footnote 90 Ceredi’s project initially encountered opposition from the Magistrato Straordinario and the Vicario di Provvisione in Milan, Alessandro Archinto, who declined to allocate funds to the machine, fearing it would jeopardize the duchy’s economy. As Ceredi reports in his treatise Tre discorsi sul modo d’alzare l’acque da’ luoghi bassi (Three discourses on the way to raise water from low places, 1567), Archinto believed that his invention might convert wheat fields into pastures, posing a potential threat to urban food supplies. In the words of Archinto, as recounted by Ceredi: “One can hope that this discovery will prove highly beneficial for pastures; however, for grains, of which our magistrate takes special care in ensuring abundance, it will be quite the opposite: considering that the land that will be converted into pastures might be so extensive that, with this convenience taken away from grain cultivation, the remainder may not be sufficient to maintain the state’s abundance. It would indeed be better, especially for the poor, if they were to run out of meat and cheese sooner than bread.”Footnote 91

With the above, the Vicario di Provvisione was asking Ceredi to negotiate on resource hierarchy, privileging certain staples over others. Rice figured as part of this discourse, and Ceredi himself cautioned against the indiscriminate use of the machine for irrigating rice fields. He combined his knowledge of Archimedean mechanics that inspired his device with insights from ancient medical texts, especially Strabo, and a neo-Hippocratic approach to understanding landscapes. Ceredi envisioned that technological and engineering interventions could transform and tame landscapes, facilitating the movement of water to serve local economies. Nevertheless, both landowners and state institutions needed to ensure that these interventions aligned with the core principles of neo-Hippocratic medical practice. Achieving such a balance required a thorough understanding of specific landscapes and climates, a point Ceredi emphasized by suggesting that using the machine for rice cultivation would be acceptable only if rice fields were exposed to northern winds (venti boreali). Such exposure would dissipate humidity and “protect neighbors from universal infirmities.”Footnote 92 According to Ceredi, such environmental conditions enabled cities such as Piacenza, Ravenna, and Venice to be salubrious despite the presence of extensive marshes and rice fields. On the contrary, cities such as Pavia and Cremona, also surrounded by marshy areas and characterized by riziculture, suffered from severe depopulation, because they were hit by southern winds (venti australi).Footnote 93 The machine eventually gained sponsorship from Milanese institutions under the premise that it would not facilitate the cultivation of rice but, rather, that of essential staples like “millet, fava beans, and beans,” crucial elements in the diets of the less affluent.Footnote 94 By expressing his fear that his machine could be appropriated and abused by “greedy humans, who would invest in numerous and large rice fields,” Ceredi partook in the general vision of rice fields as symbols of immorality.Footnote 95

Ceredi’s evocation of rice fields as threats to food provisioning and public health, along with Gallo’s description of rice farming practices and Settala’s and Botero’s emphases on stagnant waters and their unruly consequences, shed light on the entanglement between bodily, social, and natural elements in sixteenth-century ecologies. Gallo stressed the importance of placing rice field banks so that they followed the inclination of the soil, a testament to the interplay between natural resources, in this case soil and water flows, and human labor. Settala gave a medical reading of stagnant waters, one of the key features of rice fields. Even though contemporary accounts, such as Gallo’s, as well as state legislation tell us that the water in rice fields was supposed to be in motion, frequent technical failures due to the inability to set the banks correctly meant that water was, indeed, often motionless. Settala’s vision of the impact of marshy environments on the human body, and of the female womb and its fertility in particular, suggests the Hippocratic imbrication of environmental factors and bodily health; Botero took this further by adding another layer of significance, the political. He argued that un-reclaimed and marshy lands were the symptoms of a lack of industria, potentially unrooting the power of the state and its forze, which consisted in its population.

As per the writer of document D of the survey of the Magistrato Straordinario, even the appearance of individuals residing and toiling in proximity to rice fields near Novara suggested that the cultivation of this crop had a detrimental effect on their physical well-being. According to the author of this document, before the inception of rice fields, individuals were “robust, of good color, and red-blooded.” But the color of their facial skin abruptly became “gloomy” (tristo colore) once rice fields started to appear. This emphasis on skin color draws connections to the Galenic medical framework of the time, underscoring the importance of managing the six non-naturals for a healthy life.Footnote 96 In this framework, skin color was believed to signify humoral balance or imbalance, acting as a potential indicator of disease.Footnote 97 In fact, the author of the document also questioned the salubrity of rice as nourishment. He criticized those “few, wealthy individuals” who consumed the crop as a luxury good, and claimed that it was “foreigners who mostly liked rice,” putting in danger “the material goods and the life of the persone huniversali.” He even attacked the export of rice: since it made rice scarce, thus also triggering an increase in prices. He finally added, however, that rice was not that good for the poor either: “while it may seem that the poor benefit from rice as a substitute for bread, it is clear that they would be much better off and much healthier if they were sustained by the wheat they harvest instead of rice.”Footnote 98

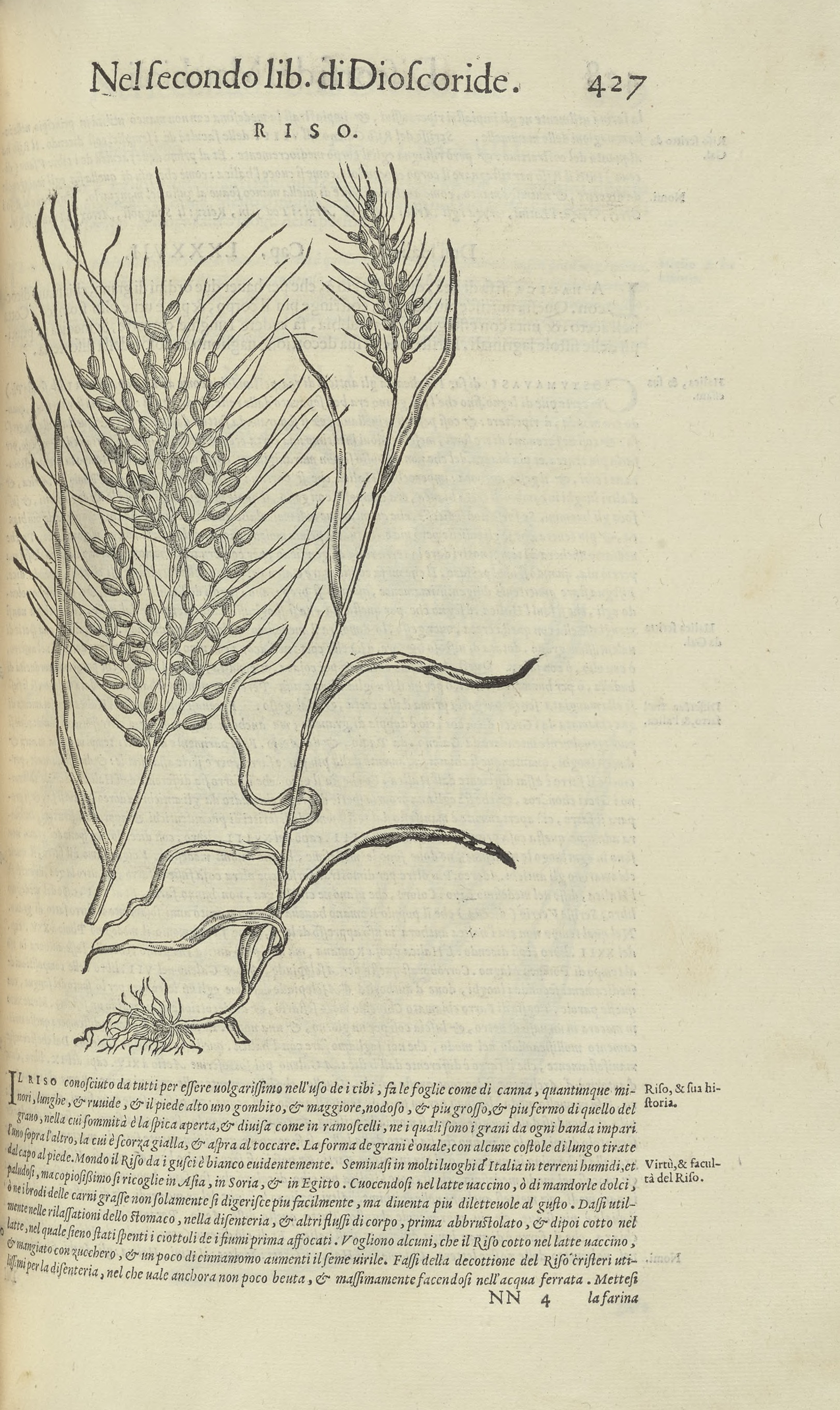

The multiple worries voiced by the author of this last document went beyond the unruly effects of rice cultivation on the landscape to implicitly address the impact that rice might have on the body through diet. As argued by historian Alexandra Walsham, early modern people did not conceive of the landscape as the inert and lifeless backdrop of historical events; rather, they endowed it with forms of agency.Footnote 99 More recently, assessing the early modern origins of the Anthropocene, Nicolas Terpstra has called for further studies of how early modern individuals appropriated, experienced, and adapted to environmental factors, including weather and seasons, and of how these elements were believed to influence both communal and individual lives.Footnote 100 Landscapes were also, however, sites of narratives of crop and food production, inextricably bound to histories of natural resources and provisioning, labor, infrastructures, and knowledge making.Footnote 101 As the case of rice exemplifies, the introduction of new crops in the landscape, as much as in the diet, also catalyzed the Counter-Reformation imperative of policing individual behavior, a process that extended to the control of eating practices.Footnote 102 In the sixteenth century, the medical community kept discussions on rice and its effects on population parallel to inquiries regarding its impression on individual bodies.Footnote 103 Certainly, rice featured in medical regimens, appeared on the table of diplomats, and was included in the diet that charitable institutions offered to the poor already in the second half of the Cinquecento. For example, in 1591, the agent of Don Pedro de Mendoza, Spanish ambassador in Genoa, bargained with the Magistrato Straordinario so that Don Pedro could bring one ton of husked “white” rice to Genoa “for his own use and without paying duties.”Footnote 104 In sixteenth-century Milan, and especially during the 1576 plague outbreak, rice was also integrated in dietary plans and sold by local retailers to charities and parishes alongside rye. In his 1595 celebration of Milanese industriousness, humanist Paolo Morigia (1525–1604) included rice in those crops offered in great quantities to the Milanese Case Pie.Footnote 105 The use of rice in a medical context emerged in Andrea Matthioli’s (1501–78) reading of the Greek Dioscorides, I Discorsi (Reference Matthioli1568), in which the physician claimed that rice was useful to block bodily fluids, but at the same time that it would only do so “mediocrely,” since it lacked in nutritive properties (fig. 8).Footnote 106 On the other hand, a decade later, in his Herbario Novo (New herbal, 1575), the Roman physician Castore Durante (1529–1590) praised rice as a medicament for fertility (together with a preparation combining cinnamon, sugar, and milk), and as a decoction to cure dysentery.Footnote 107 At times of bad harvests, rice also turned into the object of mercantile speculation. Sometime in the sixteenth century, Alfonso Gallerato, Vicario della Provvisione, the figure responsible for supervising food provisioning and establishing grain prices in the city of Milan, found himself faced with the need to buy 3,000 units of husked rice from Pietro Pallavicino, merchant and member of a renowned patriciate family from Genoa, an event that testifies to the economic potential of this crop.Footnote 108

Figure 8. Andrea Matthioli, image of rice plant, I Discorsi (1568), 427. With kind permission of the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

When it came to breadmaking, rice flour was frequently employed in combination with rye and millet flours. In particular, rice flour was a key ingredient (together with rye) in pane di mistura, a type of darker bread in use by most sectors of society at the time. The rice used in breadmaking, thus for internal consumption, was unhusked, while the rice intended for export had to go through a process called sbiancamento, literally whitening—that is, rice husking. This is the reason that, during the 1590s, years of dearth for the Duchy of Milan, the practice of sbiancamento was prohibited. In that decade, rice was used to compensate for the lack of wheat flour in breadmaking, and played a central role in provisioning the city of Milan.Footnote 109 This prohibition was reiterated later in the early 1600s, when the Presidente e Maestri delle Regie Ducali Entrate (President and masters of the royal ducal revenues) had established that only one third of all harvested rice could be husked, and thus potentially exported, leaving the other two thirds to make bread and for the poor, who used it “in breadmaking and soups.”Footnote 110 As a possible ersatz, rice tapped into narratives of scarcity and famines.Footnote 111 In his Discorso sopra la carestia, e fame (Discourse on dearth and hunger, 1591) the cleric Giovanni Battista Segni (1550–1610) reported that, in the case of the dearth of wheat, rice could be mixed, albeit in small proportion, with wheat flour, after practices in use “in the Levant, India and the island of Japan.”Footnote 112

There was no real consensus, however, on the use of rice as nourishment, especially in bread mixtures. A few years earlier, bread made of wheat flour combined with decotto di riso (rice decoction) was put center stage of a debate between physician Giovanni Francesco Arma and Giovanni Francesco Costeo (b. 1565), the son of Giovanni Costeo, personal physician to Duke Emanuele Filiberto. Appealing to medieval and ancient authorities, in particular to Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Galen, and to his own direct observation of peasants, Arma argued that rice decoction conferred too much weight and humidity to bread, thus making digestion difficult.Footnote 113 He also claimed that rice-based bread would not be as nutritious as exclusively wheat-based bread and that it would affect the liver and spleen, potentially provoking kidney stones.Footnote 114 On the other hand, Costeo attacked Arma for his excessive reliance on ancient authors rather than on experience (esperienzia).Footnote 115 He argued that it was precisely from his experience with peasants that he had learned that rice was considered less heavy than wheat when added in soups. He questioned the authority of the ancients because of their lack of “knowledge of the endless things” (cognizione di infinite cose). Among these “endless things” he recounted “clockworks and print,” contemporary inventions in “logic, medicine, and astrology,” and, finally, the proportion of rice in the ricey bread mixture under attack.Footnote 116 The case of Costeo and Arma suggests that rice became ever more present in the medical culture of the time, such that it turned into a contentious object that brought together humanistic knowledge with contemporary concerns regarding shifting dietary regimens across different sectors of society.Footnote 117 The case also sheds light on the limits of a food provisioning system that was mostly based on wheat and looked for strategies to address scarcity, especially in the aftermath of the epidemics that affected the Italian peninsula in the 1570s.Footnote 118 If rice had almost an agency of its own in rural spaces, where it was accused of being the culprit of air insalubrity, depopulation, and even death, this resource was increasingly policed when reaching urban walls.

In September 1569, the Magistrato Straordinario and the Dodeci di Provisione (Twelve deputies of provisioning), institutions entrusted with provisioning the city of Milan, obliged any secular or lay person who wanted to introduce and sell rice flour to bakers in the city to first pass through the New Broletto market (Broletto Novo).Footnote 119 This market was the site where appointed state officials weighed, assessed, and priced rice flour, as well as grains such as wheat, rye, and millet.Footnote 120 Before being stored in the building at the Broletto, rice flour had to pass through one of Milan’s various sostre, points of entrance for merchandise, usually situated along the city’s main water channel (Naviglio Grande). At the sostre, state officials sorted flours and grains into different categories (wheat, rye, millet, rice). Rice flour was then sold and distributed only to those bakers (prestinari) who specialized in the production of pane di mistura venale (mixed bread for sale). The prestinari of pane di mistura were allowed to use rice flour for baking, as well as to sell it to anyone who needed it for personal consumption. By contrast, bakers who produced the pane bianco venale (white wheat bread intended to be sold) “shall not dare accepting, exchanging, asking to buy rice flour,…nor hoarding it in their bakeries or using it for their own familiar consumption, in any given quantity.” Millers and farinai could not blend rice with wheat, rye, or millet flours either, because their amalgamation would alter the original quality of bread loaves and affect their prices.Footnote 121

CONCLUSION

This article has used the history of the inception of rice cultivation in the Duchy of Milan, and in Northern Italy more broadly, as a lens to explore the multifaceted ways early modern individuals interpreted natural resources, moving from the sites of rice production to rice as a form of nourishment. For many period observers, the deterioration caused by rice was not only materially tangible but also strongly symbolic, invested with theological and, more broadly, cultural, political, and social meanings. In sixteenth-century Milan, rice was an ambiguous object, at the same time an instrument of social control, a resource key to human survival at times of scarcity, a cause of depopulation, and the symbol of a degenerate form of improvement. Rice was politically relevant, and debates surrounding it tapped into contemporary concerns and theories of territorial control and population. The fact that rice was a cash crop, as we have seen from sources concerning its commercialization both within and outside of the Duchy of Milan, brings to the fore that the imperatives of subsistence and state self-sufficiency were more prominent than those concerning the preservation of bodily health, especially at times of unfavorable economic conjunctures and crises. This tension between the imperatives of public health and those of grain provisioning emerged both from the Turinese querelle between Arma and Costeo and from the multifarious archival references to how eating rice unsettled the Galenic balances of those who lived and toiled in rice fields.

Rice fields were also sites where various cultures of knowledge were projected and negotiated. The physician Giuseppe Ceredi sought material support from various magistracies to build his hydraulic machine, at the same time highlighting that rice was not the most important of resources, and portraying rice farming as a greedy, immoral practice that served the interest of the few, rather than of the most. Ceredi was not alone in evoking rice fields while developing water-related technologies. In 1569, the lesser-known Johannes Jacobo de Strata from Turin also appealed to Milanese institutions to have his “secrets and very useful inventions” sponsored and patented, as reported in a document signed by the then governor of the Duchy of Milan.Footnote 122 In the memoire de Strata sent to Milanese magistracies, he explained the multifarious purposes of his “machines and contrivances”—from pumping water for mills for the production of flour from “any grain,” paper, textiles, and sawdust, to the irrigation of pastures and, more generally, of what he named “places which are weak in terms of water.”Footnote 123 All these purposes, he claimed, had the broader goal of turning initially sterile lands into fertile territories. Finally, de Strata reported that his devices assisted in “sowing and harvesting rice.”Footnote 124 In de Strata’s account of landscape transformation through the application of his inventions, rice did not feature as a calamity. In this sense, de Strata’s account is symptomatic of the multiple appropriations of a resource such as rice: instead of appearing as an unruly and dangerous crop it was indirectly portrayed in the context of a discourse on how to increase wealth, soil fertility, and productivity. Similarly, in his praise of arcadia and rurality, the self-proclaimed “ancient agriculturalist” Giuseppe Falcone (d. 1597) underlined how practices of rice farming were intertwined with the ability to master water and the employment of “men who attended to that task.” He also related the cultivation of rice to the feeding of members of the rural labor force, who had “stomachs of steel.”Footnote 125

Rice had multiple lives: as a crop, it was part and parcel of discourses on wealth production and food provisioning. It had the power to metamorphose rural landscapes and triggered various forms of knowledge and social negotiations. A commodity in internal and external trade, rice reflected ideas about the victualing system of early modern societies, as it emerges from its role at times of scarcity and as an ersatz for wheat in breadmaking. As a resource, it had a specific place in the order of nature and crop hierarchy, as poetically evoked in the Tipocosmia (Reference Citolini1561), a mnemotechnical treatise by the humanist Alessandro Citolini (ca. 1500–ca. 1582).Footnote 126 Using as models the classification of wheat, rye, and barley, Citolini classified rice as a plant (herba) and edible grain (biada), including it as a component in his architecture of knowledge. As we can infer from the many documents that Milanese magistracies and various individuals produced around rice, this crop was not a natural resource like any other: it was a cultural, albeit equivocal and ambiguous, object that could potentially provoke an unruly transformation of the order of nature and at the same time play an important part in shaping the way contemporaries perceived and experienced their surroundings.

***

Lavinia Maddaluno is a fellow at the Paris Institute of Advanced Studies. She is interested in the history of political economy, science, and the environment in Europe in the longue durée (1500–1800), with special attention to the history of food and to how early moderns conceptualized and harnessed natural resources. After a PhD at Cambridge University (2018), she received various postdoctoral fellowships, from Villa I Tatti to the Warburg Institute and the EUI (Florence). Lavinia is the author of the monograph Science and Political Economy in Enlightened Milan (1760–1805), published in 2024 for the Voltaire Foundation.