Upholding fundamental principles and breaking new ground. Staying committed to socialism with Chinese characteristics, we must keep pace with the times, adapt to the evolution of practice, and take a problem-oriented approach, so that from a new starting point, we can promote innovations in theory and practice, in our institutions and culture, and in all other aspects.

Third Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of ChinaFootnote 1

Gradual adaptive change, hallmarked by policy innovation, has been a pivotal driver of China’s economic boom and a key source of its resilience.Footnote 2 Understanding policy innovation is crucial to grasping China’s reform trajectory and its political resilience. On the one hand, policy innovation has become a vital tool for addressing emerging challenges, unlocking the potential of existing institutions and mobilizing resources to resolve crises in traditional governance models. On the other hand, the profound impact of institutional change on policy innovation cannot be overlooked. Local governments’ innovation patterns have varied significantly across different reform periods. Many studies have explored specific innovation models and how these have endowed China’s institutional structure with extraordinary adaptive capacity.Footnote 3 However, few have analysed the interaction between these models as part of an overarching multi-mechanism model.Footnote 4

“Innovation championship” (chuangxin jinbiaosai 创新锦标赛), as proposed by Xufeng Zhu, is an example of a model characterized by a singular mechanism, central recognition, wherein local governments compete for central recognition through innovative policies.Footnote 5 However, the singular mechanism model exhibits limitations in accounting for a wide range of policy innovation practices. Therefore, this study aims to assess the extent to which two theoretically independent mechanisms explain innovation in China, and to reconcile these mechanisms within a unified framework.

Our analysis of policy innovations from 2003 to 2022, as recorded in the government work reports of the central government and 31 provincial governments, suggests a more comprehensive “central and peer” (CP hereafter) model. By employing an innovation dichotomy – distinguishing between generation and borrowing – we find that the central recognition mechanism (the championship model), which encourages a focus on innovation generation, plays the primary role in subnational governments’ policy innovation, while the peer recognition mechanism fosters autonomous and problem-oriented innovations. This “peer review” process serves as a valuable reference for the central government to identify innovations worthy of being elevated to national strategies, thus complementing the central recognition mechanism. Meanwhile, the central authority regulates the balance between these two mechanisms: when the central authority is strong, there is a tendency for subnational governments to prioritize obtaining central recognition, thereby reducing the influence of peer recognition, and vice versa. Additionally, our analysis yields a valuable finding: an observable difference exists between the quality and quantity of innovation. We assess innovation quality through a novel metric, borrowing volume – that is, the total number of times innovations are borrowed after their generation. This indicator reveals that a government introducing a high volume of policy innovations does not necessarily create more high-quality innovations. It further expands the dimensions used to evaluate policy innovation capacity and enables the development of a more nuanced typology of innovative government.

Policy Innovation and a Government Typology Framework

Policy innovation refers to the adoption of a policy that is new to a specific government. It is important to distinguish innovation from invention, the latter being defined as the conception of original policy ideas.Footnote 6 Based on the difference in newness of the adopted policies, policy innovation can be categorized into two types: innovation generation and innovation borrowing.Footnote 7 Innovation generation occurs when a government develops a policy that is novel for other governments under the same judicial system. Innovation borrowing is a government’s adoption of an existing policy that has been generated under the same judicial system but is new to the borrowing government.

This paper also highlights the role of government type by making a finer distinction between those that generate innovations and those that borrow them.Footnote 8 As discussed previously, innovation generation and borrowing are distinct phenomena, and different governments exhibit varying preferences for each. At the collective level, some governments act as pioneers, frequently experimenting with untested initiatives and creating new options for all potential followers.Footnote 9 Some other governments assume the role of followers, preferring to identify and leverage proven innovations that can benefit them. This latter process not only tests the followers’ judgement and capacity for absorption but also implicitly evaluates the pioneers’ ability to generate effective and exemplary innovations.Footnote 10

From “Experimentation under the Shadow of Hierarchy” to “Innovation Championship”

In the Chinese context, the term “innovation” is often conflated with “experimentation.”Footnote 11 Innovation, specifically innovation generation, is an integral part of the experimentation process, marking the beginning of the experimentation cycle.Footnote 12 Experimentation typically involves the direct participation of higher administrative levels, which may initiate experiments in promising regionsFootnote 13 or participate midway in successful grassroots initiatives.Footnote 14 The primary aim of experimentation is to generate exemplary policy instruments that can be implemented nationwide, thereby maximizing their external benefits.Footnote 15 In contrast, the purpose of innovation can vary; it may seek to address the needs of local citizens or simply to create new approaches with “qualitative differences from existing routines and practices.”Footnote 16 Whether these innovations will be adopted elsewhere is often a secondary concern. In policy experimentation, the central government defines desired outcomes, while local governments develop instruments to achieve them.Footnote 17 Conversely, in policy innovation, the central government fosters an atmosphere conducive to innovation and uses various means to outline a vague and changing opportunity space in which local governments can innovate to achieve the ideal outcomes with necessary instruments.

The intricate relationship between innovation and experimentation in China stems from the traditional “innovation-pilot-diffusion” pattern embedded in its hierarchical governance system.Footnote 18 This tradition, shaped by a policy terminology and methodology originating from the formative revolution-era experience of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), legitimizes policymaking through the principles of “creating model experiments” (chuangzao dianxing shiyan 创造典型试验) and “proceeding from point to surface” (youdian jimian 由点及面).Footnote 19 Therefore, most policy innovations are closely tied to experimentation, although many fail to achieve the expected “from point to surface” effect. Innovations (experiments) are typically initiated by local officials who need to address urgent local issues and are often motivated by personal gains, such as short-term economic benefits and rent-seeking opportunities.Footnote 20 As a result, local innovations primarily occur in areas directly related to economic development, which are also major areas of concern for the central government. In this hierarchical system, local officials seek informal support from higher-level policy sponsors, which is crucial for their policy innovations to be designated as pilot projects. If these innovations yield positive results and gain support from more senior policymakers, they may be elevated to the national level through legislation and eventually implemented nationwide. In summary, this pattern combines decentralized, experimentation-style innovations with ad-hoc central interventions, which selectively incorporate local experiences into national policymaking following the “innovation-pilot-diffusion” sequence.

Policy innovation has become deeply embedded in the career trajectories of officials due to changes in the cadre evaluation system. Since 2004, the central government has sought to reshape the incentive and pressure structure imposed on local officials, especially in terms of policy innovation, to cultivate a team of cadres with comprehensive qualities and strong innovation capabilities.Footnote 21 The changes are evident in two aspects. First, the new system provides career incentives for conducting policy experiments, creating models and implementing innovative policies that extend beyond areas with promising short-term economic returns. Cadres who consistently develop innovative approaches and achieve “excellent” ratings in areas such as economic development, social governance and administrative management are more likely to be considered for promotion.

Second, this performance evaluation system establishes a framework of control and pressure for disciplining cadres.Footnote 22 The pressure comes from continuous ranking and the risk of falling behind.Footnote 23 Failure to be “innovative” in devising and implementing policies to address pressing problems leads to lower evaluation scores, which can hinder individual career advancement. As a result, local officials must weigh the risks of a lack of policy innovation against their personal career security when determining the extent of their engagement in policy innovation. Although the rules of the system may be adjusted in response to changing political goals – for example, sometimes prioritizing incentives (the “policy innovation imperative”)Footnote 24 and at other times emphasizing pressure (“policy experimentation under pressure”)Footnote 25 – local officials remain motivated, whether by the prospect of career advancement or securing their positions, to adopt novel policies that are expected to score well in central government evaluations and earn them political capital.

These changes have sparked a wave of policy innovation competition among local governments, known as the “innovation championship.”Footnote 26 In this championship, two forces work together to drive innovation: signals from the central government indicating that innovations in certain policy areas are desirable, and the cadre evaluation system – particularly the target responsibility system – that ties innovation to officials’ career advancement.Footnote 27 As a result, local governments are motivated to devise innovations that not only align with the priorities of the central government but also stand out as pioneers rather than followers.Footnote 28 In this championship, frequent innovation generation becomes an effective strategy to capture central attention. The more new policies local governments implement, the higher the chances that some will be selected as pilot projects, a status that increases their visibility to higher authorities and ultimately contributes to the career advancement of local officials. This strategy does not imply reckless generation;Footnote 29 high-cost innovations tend to be avoided because of the considerable risks of failure, unless the officials possess reliable and supportive higher-level political resources.Footnote 30 In contrast, local governments usually avoid imitating policies from other areas, especially neighbouring ones.Footnote 31 They generally borrow innovations only when these policies have been formally recognized and elevated to the national level.Footnote 32 Failing to effectively implement innovations promoted by the central government can result in losing political points. In conclusion, the championship model posits that local policy innovations are primarily driven by local officials’ desire to maximize career advancement opportunities, which hinge on central government recognition. Therefore, we conceptualize this single operating mechanism of this model as the “central recognition mechanism.”

However, notable discrepancies exist between the expected competition and the actual findings. As observed in our research and noted by other scholars, some innovations emerge or spread without formal attention from the central government.Footnote 33 Some studies even argue that the political incentives underpinning the championship model do not significantly influence local government behaviour.Footnote 34

A plausible explanation suggests an innovation-driving mechanism that operates independently of the “innovation championship” model. Scholars posit that officials are motivated to promote innovation by intrinsic factors rather than by extrinsic incentives, such as promotion or punishment. Zhu has noted how entrepreneurial officials promote new solutions among peer governments, fostering widespread innovation without direct central support.Footnote 35 Orion Lewis, Jessica Teets and Reza Hasmath together have demonstrated that citizen-oriented officials are less responsive than entrepreneurial officials to changing structural incentives.Footnote 36 Even when the institutional context shifts to discourage innovation, citizen-oriented officials continue to innovate, motivated primarily by problem-solving imperatives rather than the pursuit of central recognition. This problem-driven logic is further substantiated by empirical evidence. Xuelian Chen and Xuedong Yang have revealed that 73.5 per cent of local officials identify resolving challenges as the primary impetus for innovation.Footnote 37 The problems and challenges driving policy innovations stem from two key dimensions.Footnote 38 First, changes in local residents’ demands serve as catalysts for innovation.Footnote 39 Such evolving demands typically correlate with gradual shifts in economic, political, social or technological conditions. When mismatches between public service supply and demand become pronounced, tensions manifest as emerging societal needs, thereby prompting local governments to innovate. Second, substantial alterations in external conditions also drive policy innovation.Footnote 40 Drastic changes can create situations where established policies are ill-equipped to address new challenges, making innovation imperative.

Drawing on the current literature, we argue that alongside the central recognition mechanism, a peer recognition mechanism also operates. Unlike the central recognition mechanism, the peer recognition mechanism does not overemphasize the generation of policy innovations, nor does it prioritize borrowing existing solutions. It propels policy innovation through a problem-solving orientation.Footnote 41 Literature has delineated these two mechanisms of innovation, yet few studies have analysed the interaction between these models as part of an overarching dual-mechanism model. Therefore, this article aims to assess the extent to which they account for innovation in China by introducing a dual-mechanism model. Empirically investigating this more complex model may provide a clearer picture of policy innovation in local governments, address existing gaps in the literature and offer valuable insights for designing future guidance on policy innovation.

Notably, strong bureaucratic incentives make provincial governments a crucial or most likely case for investigating the central recognition mechanism.Footnote 42 Higher-level officials with the potential for promotion beyond their home provinces – such as provincial and certain municipal leaders – are typically eligible to participate in the innovation championship.Footnote 43 For provincial leaders, the opportunity to advance to central leadership roles (i.e. a seat on the CCP Politburo) serves as a strong incentive to engage in this innovation competition. Additionally, because provincial governments constitute a form of local government and their leaders bear responsibility for local development, addressing public issues continues to be a central objective of their innovation efforts.Footnote 44 Hence, studying provincial policy innovation, which is subject to the dynamics of both central and peer recognition mechanisms, promises valuable insights into the dual-mechanism model.

Data and Methods

The lack of representative and sufficient official cases has significantly hindered the academic exploration of policy innovation in China.Footnote 45 To overcome this challenge, we conducted automated text analysis on provincial and central government work reports (hereinafter GWRs, or the reports). This analysis enabled the creation of a comprehensive database on provincial policy innovations, spanning 2003 to 2022, with 383,182 initiatives across various policy areas.Footnote 46 To derive more comprehensive and robust findings, we combined network analysis and case studies.

Government work reports as a comparable, diachronic pool for innovation analysis

We define the GWRs as a standardized collection for analysing policy innovation, comprising a series of comparable policy initiatives. Within this collection, each initiative represents an independent unit of potential innovation – categorized as generation, borrowing or non-innovative – and serves as the fundamental basis for assessing the innovativeness of the reports.

Using GWRs as research data also offers four advantages. First, the public availability of these reports ensures that our findings can be replicated in future research. Second, as official government documents, the reports adhere to strict standards. Their formalized representation and semantic computability satisfy the preconditions for automated text analysis.Footnote 47 Third, each report includes sections reviewing performance of the past year and outlining “total arrangements” (general plans) for the upcoming year. The latter section provides valuable information for studying a government’s overall innovation initiatives, as its broad scope, which covers hundreds of programmes or policies across various areas, mitigates the risk of lack of representativeness due to focusing on a limited set of policy domains.Footnote 48 Fourth, implementation mechanisms, such as the “GWR targets break-down document,” annual performance evaluations and supervision by the People’s Congress Standing Committee, ensure the commitments in the reports are effectively carried out.Footnote 49

Although GWRs provide a standardized and relatively stable source of policy initiatives, concerns about selective disclosure persist. As Vincent Brussee argues, Chinese government documents may exhibit variations in disclosure practices,Footnote 50 particularly through (1) temporal selectivity, wherein governments alter the number of disclosed policy documents over time, resulting in dramatic shifts in observed innovation, and (2) spatial selectivity, wherein governments in different jurisdictions may disclose policies in diverse policy areas (for example, economic reforms rather than social welfare). Prior research has demonstrated that GWRs possess sufficient cross-jurisdictional consistency to support reliable comparisons across localities and produce generalizable findings.Footnote 51 To address the concern of temporal selectivity, we conducted supplementary analyses of provincial GWRs on longitudinal consistency (see Appendix B-The Temporal Selectivity Assessment of Government Work Reports in the online supplementary materials). Our tests show that provincial GWRs possess less temporal selectivity in disclosure than do provincial policy documents.

Automatic text analysis

We leverage a novel automated text-analysis method that integrates machine learning and natural language processing to compute innovation indices based on textual similarity. This method comprises the following two parts.

(1) Data cleaning. For each GWR in our sample, we extract only the “total arrangements” sections (see Figure A1) and remove extraneous content (such as political jargon) through both automated and manual screening.

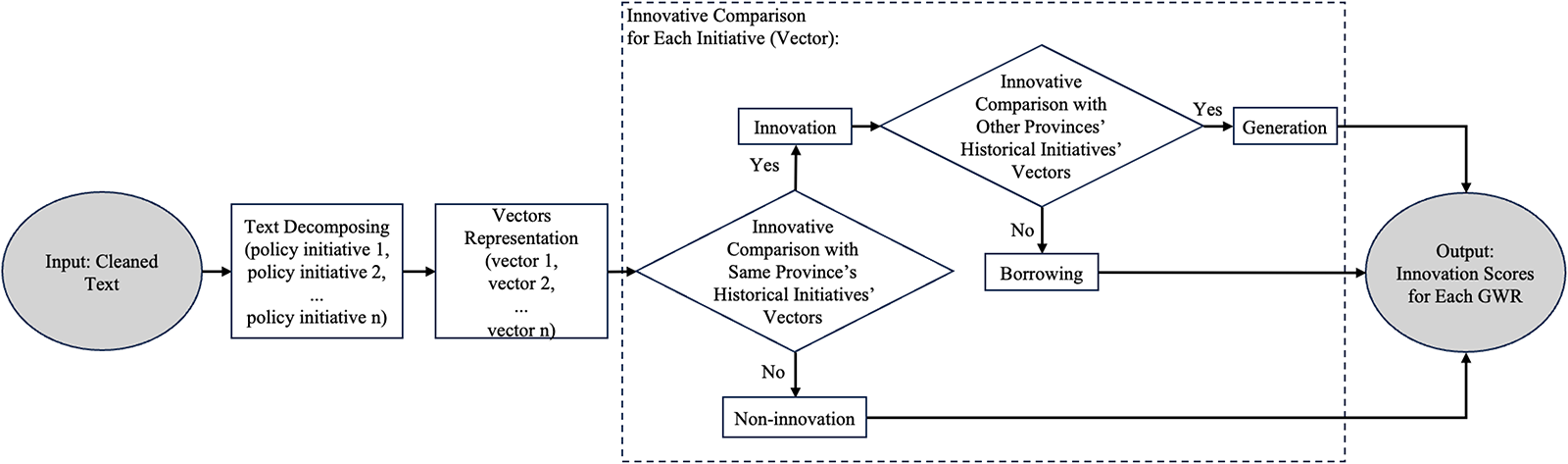

(2) Innovation calculation. Innovation calculation involves determining whether each policy initiative is innovative and assigning an innovation score to each GWR (see Figure 1). First, we segment the cleaned text into discrete sentences, with each sentence representing a single policy initiative (see Appendix A-Step 2: Text Decomposition in the online supplementary materials). Next, we generate vector representations for each policy initiative through dependency syntactic parsing and pre-trained language models (see Appendix A-Step 3: Word Set Extraction and -Step 4: Vector Representation in the online supplementary materials). Using these vectors, we systematically compare each initiative against: (1) all historical initiatives within the same province’s GWRs, and (2) all historical initiatives from other provinces’ GWRs. These comparisons enable us to identify whether an initiative constitutes innovation generation or borrowing (see the online Appendix A-Examples for specific examples).

Figure 1. The Process of Innovation Calculation for Each Provincial GWR

Following the steps above, we compute annual innovation scores for each government by aggregating the innovation assessments of all policy initiatives outlined in its reports, yielding two indices for innovation generation and innovation borrowing, respectively. The innovation generation/borrowing index measures the change in the quantity of innovations generated/borrowed by a government during a given period.

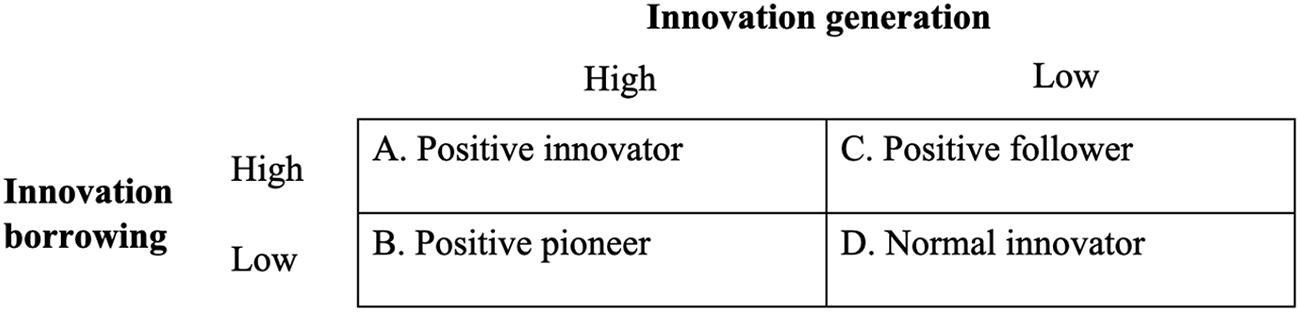

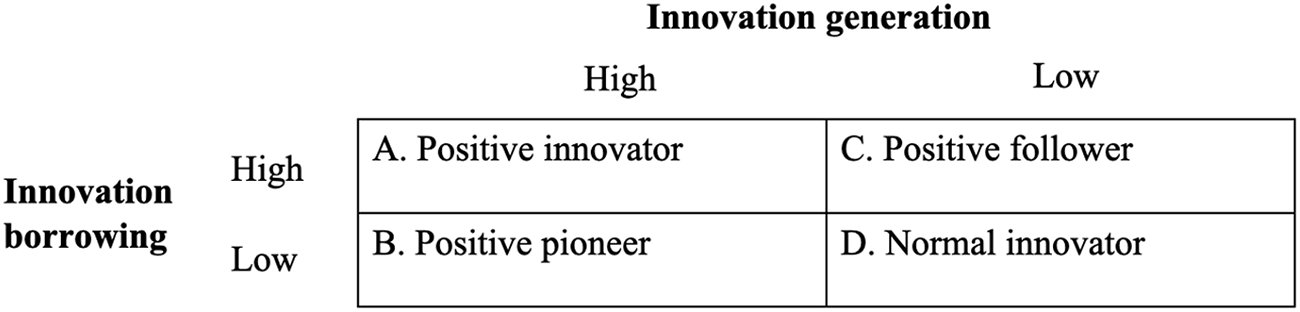

This study classifies all provincial governments based on the two innovation indices. If a government’s innovation borrowing score exceeds threshold X, it is considered a “positive follower”; otherwise, it is deemed a “normal follower.” The same principle applies to the classification based on the innovation generation score (see Figure 2). Threshold X is calculated as 40 per cent of the maximum score plus 60 per cent of the average score for all governments on an index.

Figure 2. Classification of Innovative Government Types

Network analysis

Using network analysis, we further explore the characteristics of different innovative governments and the connections between them. In this network, each node represents a government unit, with directed edges indicating the flow of innovations from one node to another. The weight of each edge corresponds to the number of innovations borrowed from the originating node by the destination node within a given period. We calculate several centrality metrics, which are key to identifying the importance of a node within the network.Footnote 52 These metrics include (a) degree centrality, measured by the average weight of edges connected to a node, which reflects the total number of innovations a government has borrowed from others plus the number of times its generated innovations are borrowed by others; and (b) closeness centrality, measured by the average distance from a node to all other nodes, which reflects how many times innovations generated by a government are borrowed by other provinces. These centrality metrics are incorporated into the network node attributes.

We compare two networks to examine the differences in provincial policy innovation with and without central government involvement. The first network comprises nodes representing 31 provincial governments and the State Council (Guowuyuan 国务院), along with the edges between them. The second network excludes the State Council node and omits all central-generated and central-borrowed innovations from the edge weight calculations.

Qualitative analysis

Although our supplementary analyses and prior research mitigate concerns about the dataset’s objectivity, best practices for large-scale documentary analysis necessitate integrating qualitative material to enhance validity.Footnote 53 Accordingly, we included two representative cases, interview data and a range of supplementary news, including news reports, media interviews,Footnote 54 policies and secondary commentary, to provide critical contextual insights and help triangulate and interpret our quantitative findings. Two cases are from Zhejiang province: the Multi-field Consolidation Project (duotian taohe gongcheng 多田套合工程) and the Government Service Value-added Reform (zhengwu zengzhihua gaige 政务增值化改革).

Results

Differentiation of provincial governments’ innovation roles

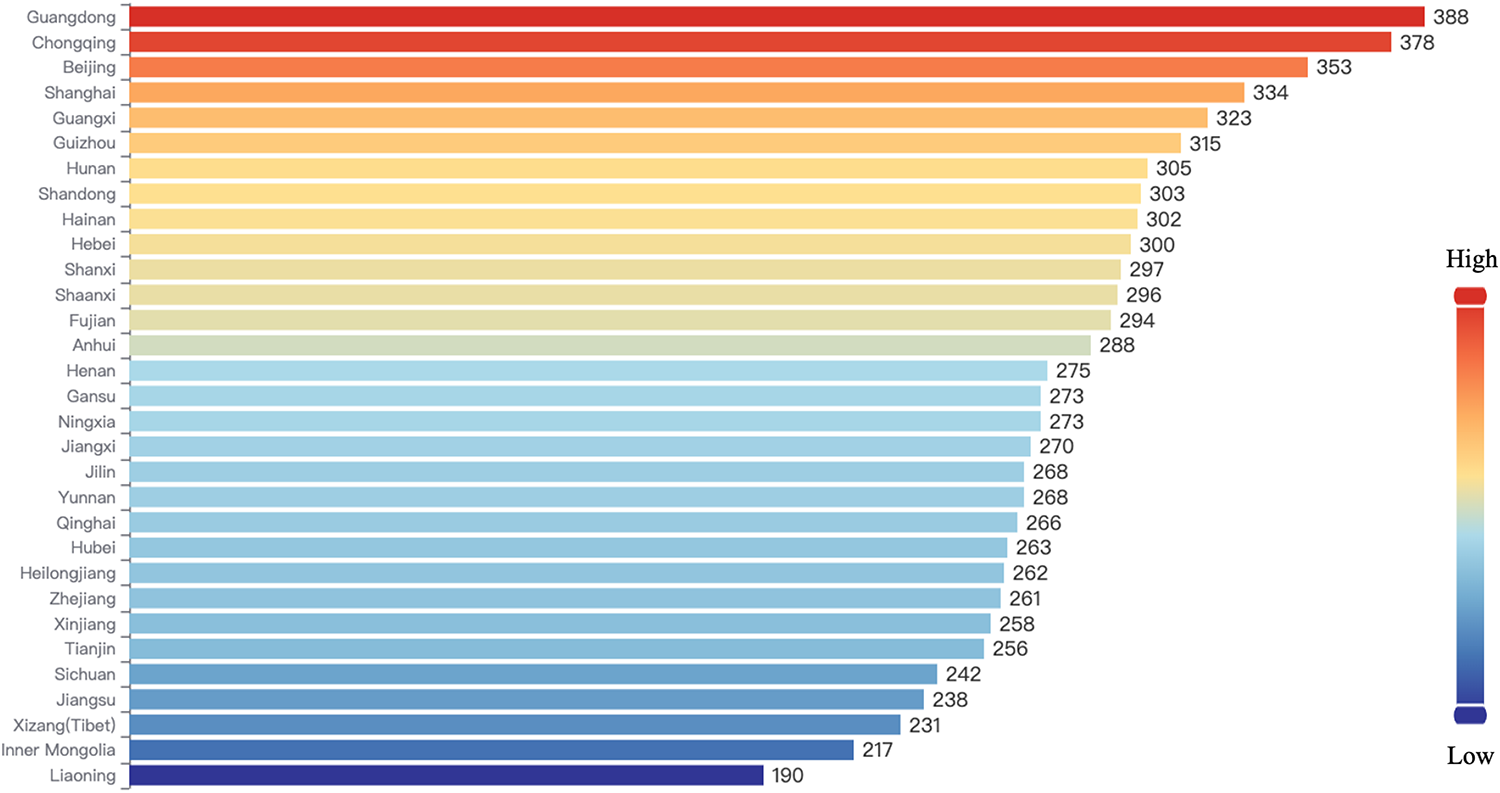

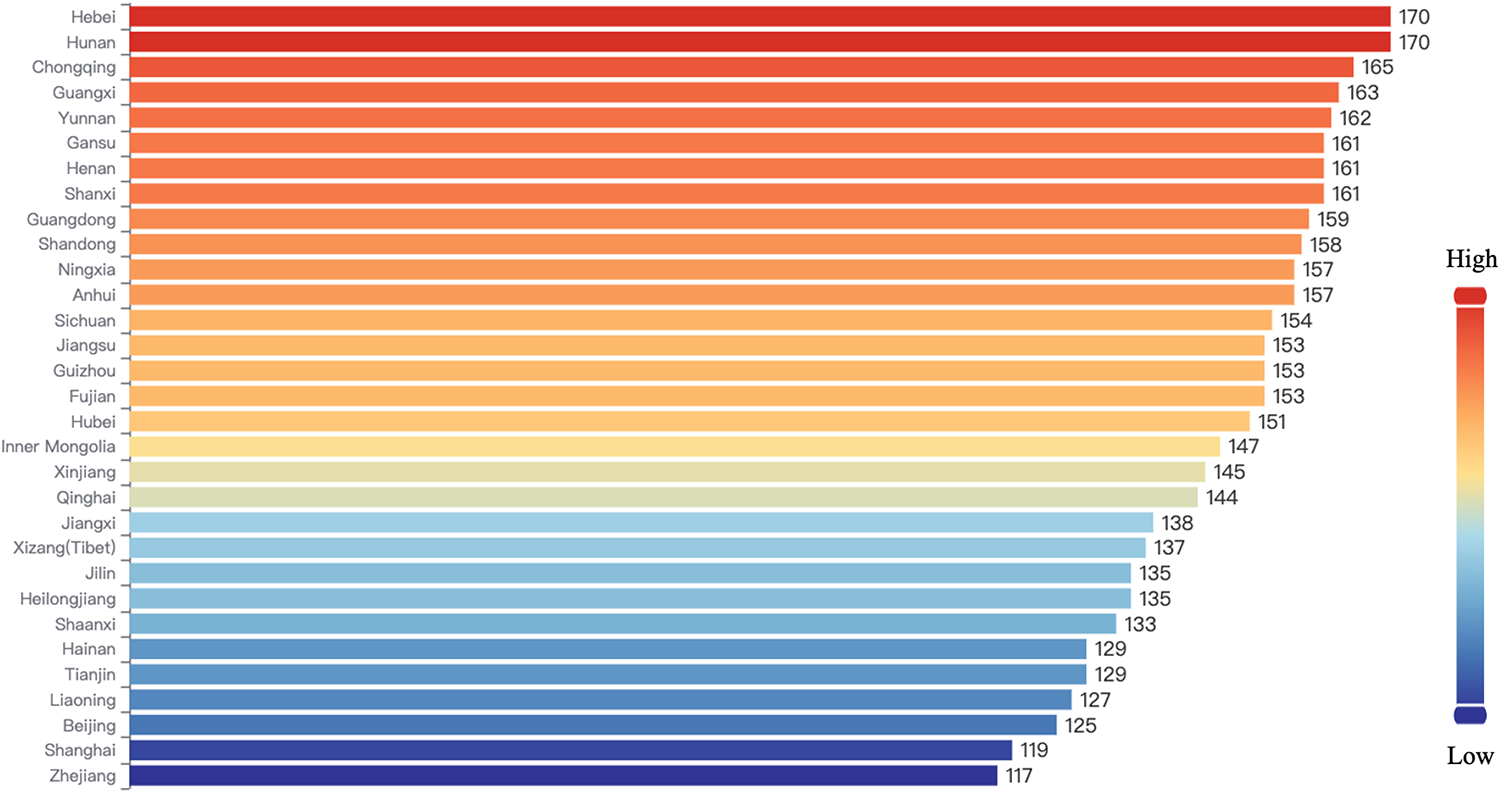

First, we analyse the spatial distribution of the average scores of two innovation indicators for 31 provincial governments from 2003 to 2022 (see Figures 3 and 4). Overall, provincial governments have maintained robust innovation performance over the past 20 years, with the number of innovations generated significantly higher than the number of those borrowed. On average, each province generates 283.42 innovations per year (SD = 18.19) and borrows 147.33 (SD = 13.69).

Figure 3. Spatial Distribution of the Annual Average Innovation Generation Index, 2003–2022

Figure 4. Spatial Distribution of the Annual Average Innovation Borrowing Index, 2003–2022

The Innovation Generation Index shows an even distribution across different regions, with a few provinces – notably Guangdong, Shanghai, Beijing and Chongqing – standing out with higher scores. These regions, particularly Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong, are considered the most developed in China and possess inherent innovation advantages, such as abundant resources and a more open environment. Moreover, as leaders in national reform, these regions often encounter emerging challenges earlier than others, prompting them to generate innovative solutions. Additionally, these provinces are vice-national regions, with their Party secretaries holding Politburo membership. Given the potential for promotion to the Politburo Standing Committee, these leaders may devote greater effort to generating innovations that yield exemplary and nationally applicable results. Furthermore, their access to higher-level political resources reduces concerns about the lack of central government sponsorship and increases their tolerance for the risks associated with innovation failures. As a result, they are more inclined to prioritize innovation generation.

The Innovation Borrowing Index is higher in central and western regions than in coastal areas. Owing to their lower levels of economic development and population density, these less developed provinces face constraints in conducting the resource-intensive experiments needed to generate novel solutions. Therefore, borrowing successful practices from pioneers might be a more cost-effective approach than developing entirely new solutions from scratch.

The analysis of government types reveals the distinct innovation roles among China’s provincial governments (see Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of Government Types, 2003–2022

While these descriptive data offer preliminary insights into the policy innovation levels and characteristics of provincial governments, they provide a limited understanding of more nuanced aspects. For example, do positive pioneers lead to greater innovation borrowing? How would provincial innovation characteristics change if central government-generated/-borrowed innovations were excluded? Would that significantly reduce the scale of innovation or alter a government’s innovation type? Next, we explore these details with a network analysis.

The innovation network of provincial governments

We further examine the relationships between various innovative governments and the impact of the central government on provincial innovation through network analysis. The networks are built using innovation data from 2003 to 2022.

The top ten provinces in terms of closeness centrality are predominantly from the eastern coastal regions – for example, Guangdong, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Beijing. These more developed areas possess the resources and experience necessary to generate exemplary innovations that are broadly borrowed. Unsurprisingly, the State Council ranks first, as borrowing innovations from the State Council is a significant aspect of the innovation championship. Notably, Zhejiang and Jiangsu rank in the top eight for closeness centrality, despite being ranked below 25th in innovation generation. This indicates that while they generate fewer innovations, those they do generate are widely borrowed. These two provinces are often pioneers in public service reforms, offering innovative and effective solutions for their jurisdictions and the entire country. For instance, in 2017, Zhejiang launched the “Visit once” service reform, which was subsequently adopted by 29 provinces.Footnote 55 Thus, a high volume of innovation generation does not guarantee that such innovations exert high levels of influence, as measured by closeness centrality.

In terms of degree centrality, Guangdong, the State Council and Chongqing exhibit the highest levels of association with all provinces. The top ten provinces also include those with high closeness centrality scores, such as Anhui and Jiangsu, as well as those known for extensive innovation borrowing, like Guangxi and Yunnan.

We conducted a network comparison to assess whether innovation connections among provincial governments persist when central-generated/-borrowed innovations are excluded. Analysis of the top ten provinces regarding closeness and degree centrality, both before and after excluding the State Council’s influence, shows consistent rankings. The results suggest that removing central government influence does not substantially change the roles of different governments in the innovation network. Provinces that often act as pioneers and network hubs continue to do so, even without the central government’s involvement.

The impact of central government influence

The analysis above provides valuable insights into the spatial and structural characteristics of provincial policy innovation from 2003 to 2022, while also highlighting the stability of these characteristics with or without central government influence. However, two aspects remain unresolved: 1) the temporal stability of these innovation patterns is unclear, as existing literature has documented substantial differences over time;Footnote 56 and 2) it is unclear to what extent central government recognition compels other governments to “borrow” specific innovations. To address these questions, we begin by examining the annual provincial-level trends in both the Innovation Generation Index and the Innovation Borrowing Index. We then decompose the Innovation Borrowing Index to investigate how it is affected by central government influence. This multi-level comparison of changes in policy innovation helps to uncover deeper insights.

We compare two periods to examine how changes in central steering impact provincial policy innovation. As previously mentioned, we analyse policy innovation data from 2003 to 2022, spanning the tenures of two leaderships, those of Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 and Xi Jinping 习近平. This situation provides a natural experiment to assess whether changes in central steering influence provincial governments’ preferences for policy innovation, especially regarding the innovation championship. Footnote 57

Results in Figure 5 reveal notable differences in policy innovation between the two periods. Under Xi’s administration, the Innovation Generation Index for provincial governments increased, compared to the Hu era (from an average of 279.03 per province to 288.73), while the Innovation Borrowing Index saw a decline (from an average of 155.10 per province to 137.83). When central-generated/-borrowed innovations are excluded, the decrease in non-central influenced innovation borrowing is more evident than the overall decrease in innovation borrowing (from an average of 145.60 per province to 125.20), suggesting a slight increase in central-influenced borrowing (from an average of 9.50 per province to 12.63). This indicates that with the increasing central coordination, provincial innovations related to the championship, both in terms of innovation generation and central-influenced innovation borrowing, have grown. In contrast, non-central influenced innovation borrowing has decreased as authority became more centralized.

Figure 5. Annual Changes in Two Innovation Indices with a Decomposition of the IB Index by Isolating Central Government Influence

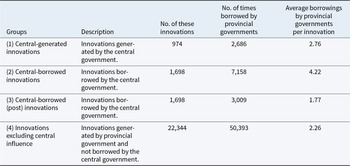

The results in Table 2 illustrate the effect of central selection on provincial borrowing. Overall, innovations bearing central influence – whether generated by the central government or borrowed by it – exhibit a higher degree of diffusion than those bearing no such influence. Groups 2 and 3 indicate that once an innovation is borrowed by the central government, its average number of borrowings increases by 1.77. Moreover, innovations later borrowed by the central government (Group 2) already exhibit a higher average of peer borrowings (2.45) before central borrowing than innovations without central influence (Group 4), which average 2.26 peer borrowings. This may suggest that innovations likely to be recognized by the central government are more prone to peer borrowing because they are better.

Table 2. The Effect of Central Selection on Provincial Borrowing

Findings

A novel central and peer model

The results indicate that the mechanism of central recognition (the innovation championship) fosters competition among local governments in innovation generation without strictly limiting the diffusion of innovations. Data from 2003 to 2022 reveal that innovation generation is the predominant choice for provincial governments, accounting for 66.7 per cent of total innovations, evidence that the central recognition mechanism captured the primary attention of provincial governments. However, contrary to previous literature suggesting that central recognition does “not yet seem to have resulted in many policies that were adopted outside of the locations where they originated,”Footnote 58 a significant number of innovative policies have been borrowed, amounting to roughly half of those generated. Most of these borrowed innovations are neither centrally generated nor centrally borrowed.

These instances of innovation borrowing that occur independent of central recognition indicate the existence of the peer recognition mechanism. This assertion is affirmed by secretaries from provincial government offices across diverse regions, who note that “they represent the two primary mechanisms driving policy innovation in local governance.”Footnote 59 The central recognition mechanism propels innovation generation – and the subsequent diffusion of central-generated or central-borrowed innovations – through top-down pressures or incentives. In contrast, the peer recognition mechanism fosters problem-driven innovations, whether generated locally or borrowed from peers.

Peer recognition differs from central recognition in that it is not one-off; each instance of problem-driven borrowing reinforces the recognition of the original innovation, since borrowed innovations are typically those that are deemed to be effective and exemplary.Footnote 60

According to the innovation diffusion theory, policy diffusion typically follows an S-shaped cumulative distribution curve,Footnote 61 implying that the peer recognition mechanism exhibits a tipping point: once the number of borrowings (recognition) surpasses a critical threshold, increased visibility triggers rapid and extensive diffusion. Prior to this tipping point, diffusion remains sluggish, as observed in our two case studies (see Tables 3 and 4). Potential adopters may identify borrowable innovations (i.e. “spread”Footnote 62 ) through specific channels, including visits and exchanges, media reports and academic activities and publications (see the online Appendix B-Innovation Spread Channels for the two detailed cases and supporting data).

Table 3. Timeline for the Generation and Borrowing of the Government Service Value-added Reform

Table 4. Timeline for the Generation and Borrowing of the Multi-field Consolidation Project

As borrowings accumulate, the peer recognition mechanism complements the central recognition mechanism by providing the central government with valuable information on innovations that are worth elevating to national policy. The statistics indicate that innovations that ultimately receive central recognition generally accrue more peer borrowings, even before central borrowing, than those that do not.

Central recognition accelerates the tipping point for horizontal diffusion under the peer recognition mechanism, enabling rapid nationwide borrowing. Our data show that once an innovation is adopted by the central government, its average number of provincial borrowings increases by 72.2 per cent (from 2.45 to 4.22). The effect is also illustrated by our two case studies. After State Council recognition, the Government Service Value-added Reform was borrowed by seven additional provinces within one year, tripling its pre-central recognition diffusion degree. In contrast, the Multi-field Consolidation Project, which was initiated around the same time but did not gain central recognition, had been borrowed by only two provinces by the end of 2024.

This dual-mechanism model, driven by both central and peer recognition, has led to differentiated roles among provincial governments and the formation of a collective innovation network. Governments that excel in generating innovations act as pioneers in the network, while those adept at absorbing and adapting innovations serve as positive followers. At the collective level, this model may represent the optimal approach to policy innovation for countries like China, which exhibit both regional economic decentralization, characterized by varying levels of innovation resources, and vertical administrative structures that reduce the cost of borrowing innovation due to homogeneity among governments.Footnote 63 Precisely, it allocates specific innovative roles to provincial governments, based on factors like resources and organizational conditions, to maximize collective innovation efficiency. As Sean Nicholson-Crotty and colleagues suggest, when subnational governments operate collectively rather than individually, the pioneers provide opportunities for other governments to borrow new solutions at a lower cost or of higher quality than they could develop independently.Footnote 64 Therefore, governments with fewer innovation resources are more likely to be receptive to innovation borrowing to make up for deficiencies in their capacity.Footnote 65

The extent of the influence of the central authority regulates the dynamics between the two mechanisms. Stronger central government makes local governments more receptive to authority, thereby amplifying the pressure mechanism’s influence.Footnote 66 This shift intensifies local governments’ focus on central recognition, weakening the effectiveness of peer recognition. As a result, the number of innovations addressing local needs and issues of residents – typically the source of high-quality, sustainable and easily diffused solutions – has decreased, which is reflected in a decline in the number of innovations recognized by awards or developed by officials with innovative personalities, as noted in the data analysed by Teets, Hasmath and Lewis.Footnote 67 Conversely, the number of innovations driven by the central government’s indirect or direct mandates has increased, reflecting the intensified competition in innovation generation observed by Xiaobo Hu and Fanbin Kong, along with a rise in innovation borrowing influenced by the central government, as noted by Abbey Heffer and Gunter Schubert.Footnote 68

The data reveal a persistent decline in borrowing driven by peer recognition. While top-down policy design facilitates the exploitation of innovation externalities by accelerating the emergence and diffusion of exemplary practices in priority sectors,Footnote 69 dispersed innovation driven by peer recognition has historically served as a cornerstone of the ability to adapt and change by continuously diversifying the national toolkit for addressing emerging challenges. The central government continues to play a guiding role in identifying viable innovations, defining permissible boundaries for experimentation and prioritizing policy domains – tasks that increasingly compel local governments to focus on solving centrally prioritized tasks rather than tackling local governance complexities. As one interview explained, “We submit a list of purportedly completed innovations to our superiors. Only when an innovation receives formal recognition do we proceed with its implementation.”Footnote 70

Excessive focus on these tasks is likely to lead to performance-oriented innovations that lack sustainability, waste resources and undermine administrative efficiency. This could gradually pose challenges to China’s policy adaptability and transformative capacity.Footnote 71 Therefore, to fully capitalize on the better adaptability inherent in dispersed policy innovation, it is important to establish an equilibrium between central and peer recognition mechanisms.

In summary, we propose that the central recognition mechanism (the championship) is the primary driving force behind provincial policy innovation, while the peer recognition mechanism provides a crucial complement. Together, they form a comprehensive Central and Peer (CP) model. Within the central recognition mechanism, local officials are motivated to pursue policy innovations that would gain them political capital for promotion. This mechanism emphasizes competition in generating new policies and discourages the borrowing of innovations that are not generated or borrowed by the central government. In contrast, the peer recognition mechanism encourages local governments to generate policies or borrow exemplary ones that address local needs and solve residents’ problems. Here, peer recognition acts as an incentive for local innovation and facilitates innovation borrowing by offering insights into which policies to adopt. Over time, the CP model has driven the differentiation of innovation roles among subnational governments, leading to an unexpected collective innovation pattern at the provincial level in China.

A new classification of innovative governments

We have identified certain limitations in the existing classification of innovative government types. Our network analysis reveals that positive pioneers do not necessarily generate innovations that are widely adopted. One key reason is that these novel options may not be high-quality, exemplary innovations, which makes gaining peer or central recognition difficult. For instance, the eastern coastal regions, particularly Zhejiang and Jiangsu, are widely recognized as pioneers in policy innovation in China. Despite ranking below 25th in the sheer quantity of innovations generated, these provinces are ranked in the top eight for the number of times that their innovations are borrowed. Evaluating governments solely on the quantity of innovations generated might overlook the actual influence of these innovations and overestimate the contributions of provinces that prioritize sheer quantity over quality.

To address this issue, we revised our classification of the innovation generation dimension to account for how the quality of innovations influences their subsequent borrowing by others. Drawing on insights from Craig Volden and Everett Rogers, we recognize that borrowed innovations are typically of high quality, as few would adopt harmful or inefficient solutions.Footnote 72 Therefore, the number of times that an innovation is borrowed externally serves as a meaningful measure of the innovation’s influence. The revised dimension of innovation generation now incorporates both quantity and influence and is divided into four types: influential and positive pioneers, influential pioneers, positive pioneers and normal pioneers. The classification of innovative government types has been adjusted accordingly to reflect this more nuanced understanding.

Conclusion and Future Work

This study, which is grounded in empirical analysis, attempts to depict a comprehensive picture of policy innovation among provincial governments in China by developing an explanatory model that is more robust than a single model. By examining data from Chinese provincial GWRs from 2003 to 2022, we conclude that provincial policy innovation operates collectively under the dual influence of a central recognition mechanism (the innovation championship) and a peer recognition mechanism. This study defines this combined approach as the Central and Peer (CP) model, which integrates two different and theoretically independent mechanisms within a unified framework. Admittedly, a few exceptions remain – for instance, officials nearing retirement are more likely to avoid risks through “inaction”Footnote 73 – but the CP model nonetheless explains the vast majority of subnational policy innovations.

This study reveals that the influence of central authority regulates the dynamics between the two mechanisms within the CP model. An increase in central authority strengthens the central recognition mechanism, while a decrease enhances the peer recognition mechanism. This raises a critical question: what is the optimal authority configuration for promoting policy innovation? Should it prioritize decentralization, centralization, or find a balance between the two? The answer depends. When a burst of creativity and diverse ideas is needed, control should be relaxed in order to enhance incentives for spontaneity and reduce the focus on the central recognition mechanism. Conversely, when it is necessary to leverage the strengths of centralized authority, greater central steering should be emphasized to heighten the pressure from central recognition. Excessive central steering can lead to an overabundance of performance-oriented innovations with limited sustainability,Footnote 74 while excessive decentralization may “offer subnational actors extra bargaining power with which to ‘blunt’ the state leaders’ policy initiatives and ‘frustrate’ the upper-level authorities.”Footnote 75 Thus, the optimal authority configuration involves dynamic adjustments within a reasonable range. Although this study does not establish the precise parameters for this range, it offers a valuable starting point for future research on authority configurations and their impacts on policy innovation.

This paper introduces a novel typology of innovative governments based on the concept of newness. Drawing on existing research on innovative organizations,Footnote 76 we classify governments into four types: normal innovator, positive pioneer, positive follower and positive innovator, based on the two types of innovation, innovation generation and innovation borrowing. Furthermore, we refine the classification of the innovation generation dimension into influential and positive pioneers, influential pioneers, positive pioneers and normal pioneers. This refinement enhances our understanding of innovative governments and provides new insights for the theoretical development of innovative-organization classification.

This paper may respond to an interesting point: “Local leaders are incentivized to innovate, but not necessarily to do it well.”Footnote 77 Previous scholars have argued that Chinese policy innovation often struggles with sustainability.Footnote 78 The data analysis in this study finds a low borrowing volume for innovations, indicating that only a minority of innovations are borrowed after their generation. Both sustainability and innovation borrowing volume are important indicators of innovation quality. The poor performance in both indicators might be linked to the prevalence of performance-oriented innovations with limited sustainability. Two reasons drive such innovations. First, the primary purpose of innovation generation is usually not to respond to local problems but to create new “progress” that is different from previous practices. Second, local leaders often have short tenures due to high mobility, leading them to favour short-term effects when innovating.Footnote 79 Consequently, incoming leaders are likely to discard previous policies in favour of new ones that pursue short-term outcomes. As a result, accumulating performance-oriented innovations aimed at aligning with organizational priorities becomes the preferred strategy for many. Clearly, the central government needs a more in-depth, science-based performance evaluation system to assess the true quality of innovations developed by local officials. However, the tension between the short tenures of officials and the long duration needed to evaluate innovative policies poses a significant challenge. This challenge highlights the need for practical solutions and suggests potential research avenues for scholars studying the intersection of policy innovation and cadre promotion.

Despite the measures taken in this study, such as consistency analysis and qualitative case studies, to mitigate concerns about the fragility and changeability of the digital data used, the problem of temporal selectivity in government work reports remains unresolved. Therefore, we will provide access to the dataset for other scholars to replicate and test our findings.Footnote 80 More importantly, this will facilitate further research to explore, compare and discover more robust and convincing data and operationalization methods for policy innovation studies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary materials for this article can be found at at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741025101732.

Funding information

This research was supported by the Key Project of Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education of China [2023JZDZ036] and the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China [72434004].

Competing interests

None.

Junxing WANG is a public administration PhD candidate in the School of Public Affairs at Zhejiang University. His current research focuses on public sector innovation and computational social science.

Jianxing YU is a professor in the School of Public Affairs and the dean of the Academy of Social Governance at Zhejiang University, the director of the Laboratory for Statistical Monitoring and Intelligent Governance of Common Prosperity at Zhejiang Gongshang University, and the director of Zhejiang Provincial Key Lab of Computational Science for Common Prosperity. His research focuses on digital government, digital governance and social governance.