Non-technical Summary

Giant sea scorpions were important in ancient seas as top predators within the food chain. However, their evolutionary history remains unclear. The well-known Xiaxishancun Formation from Qujing City in Yunnan, China, preserves various fauna including three species of sea scorpions. Here, we report new material of two sea scorpion species from this region and provide discussions on their morphology and ecology: Erettopterus qujingensis and Pterygotus wanggaii. In addition, given the ambiguity in previous cheliceral denticle nomenclature for sea scorpions, we introduce a new framework to define those denticles based on their relative position. This involves three basic types, within one containing two subtypes: TD, terminal denticle; MD, median denticle (including: MMD, modified MD, and OMD, ordinary MD); BD, basal denticle. Additional description is supplemented for the cheliceral denticles of E. qujingensis, a species that is distinguished from Pterygotus wanggaii by its different number of MMDs.

Introduction

Eurypterids (sea scorpions) are a group of Paleozoic aquatic chelicerate arthropods that lived from the Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) to the Late Permian (Changhsingian), with > 250 described species (Tetlie, Reference Tetlie2007; Braddy, Reference Braddy2022). Despite the diversity and wide distribution of eurypterids, their fossil remains are relatively scarce in China (Tetlie et al., Reference Tetlie, Selden and Ren2007), comprising only nine species (Table 1). Among all eurypterids, the superfamily Pterygotioidea Clarke and Ruedemann, Reference Clarke and Ruedemann1912 is the most diverse clade, encompassing hughmilleriids, slimonids, and pterygotids. However, it is unclear whether this apparent diversity was a result of their dispersal ability (Tetlie, Reference Tetlie2007), the adaptation in prey capturing with their chelicerae (Lamsdell, Reference Lamsdell2022), or taxonomic over-splitting (Ciurca and Tetlie, Reference Ciurca and Tetlie2007; Braddy, Reference Braddy2022; Lamsdell, Reference Lamsdell2022). Biomechanical analyses of their telson and swimming appendages suggest that Pterygotioidea were active swimmers (Plotnick, Reference Plotnick1985; Tetlie, Reference Tetlie2007; Bicknell et al., Reference Bicknell, Simone, Meijden, Wroe, Edgecombe and Paterson2022; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023).

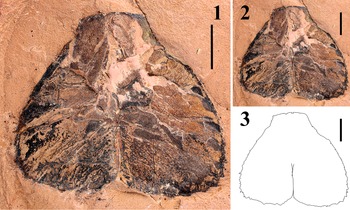

Table 1. Eurypterid species described from China in chronological sequence

The family Pterygotidae (Tetlie, Reference Tetlie2007; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, McCoy, McNamara and Briggs2014; Lamsdell, Reference Lamsdell2022) existed from the Lower Silurian (Llandovery) to the Middle Devonian (Eifelian) (Tetlie, Reference Tetlie2007; McCoy et al. Reference McCoy, Lamsdell, Poschmann, Anderson and Briggs2015; Plotnick, Reference Plotnick2022). Pterygotids include some of the largest arthropods ever to have lived, reaching body lengths of up to two and half meters or more (Kjellesvig-Waering, Reference Kjellesvig-Waering1964; Chlupáč, Reference Chlupáč1994; Braddy et al., Reference Braddy, Poschmann and Tetlie2008; Lamsdell and Braddy, Reference Lamsdell and Braddy2010; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023). The family contains five genera (excluding the fragmentary Necrogammarus Woodward, Reference Woodward1870): Acutiramus Ruedemann, Reference Ruedemann1935; Ciurcopterus Tetlie and Briggs, Reference Tetlie and Briggs2009; Erettopterus Salter in Huxley and Salter, Reference Salter, Huxley and Salter1859; Pterygotus Agassiz, Reference Agassiz and Murchison1839; and Jaekelopterus Waterston, Reference Waterston1964; covering ~58 species, rendering it the most diverse clade within the order Eurypterida (Lamsdell and Selden, Reference Lamsdell and Selden2017; Lamsdell, Reference Lamsdell2022; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that several species might turn out to be synonyms reflecting ontogenetic or preservational variation within the species (Lamsdell, Reference Lamsdell2022; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023).

Notable morphologies of Pterygotidae include their enlarged chelicerae and dorsoventrally compressed pretelson (Tetlie and Briggs, Reference Tetlie and Briggs2009). Pterygotids were carnivorous and varied in size, visual acuity, and cheliceral denticle morphology, thus these different genera were probably specialized predators. Such morphology allowed them to occupy various ecological niches as active predators (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, McCoy, McNamara and Briggs2014; McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Lamsdell, Poschmann, Anderson and Briggs2015; Bicknell et al., Reference Bicknell, Kenny and Plotnick2023; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023). Consequently, pterygotids achieved a nearly global distribution except in Antarctica (Miller, Reference Miller2007; Tetlie and Briggs, Reference Tetlie and Briggs2009; Lamsdell and Legg, Reference Lamsdell and Legg2010; Wang and Gai, Reference Wang and Gai2014; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022, Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023; He et al., Reference He, Wang, Dai, Lu and Yang2024). Based on their earliest fossil record dating back to the Llandovery Epoch of the Silurian Period, pterygotids might have originated from Laurasia (Tetlie, Reference Tetlie2007). However, more fossils have been discovered from Gondwanan regions in recent decades, offering more evidence of their early dispersal and evolution history. Pterygotid material from Yunnan Province in China has been reported in the past three years, revealing a diversity of coexisting species that exhibit notable similarities, e.g., comparable faunal composition and morphologies, with their European counterparts (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022, Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023). The Xiaxishancun Formation dates to the Lochkovian Epoch of the lowermost Devonian (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Xue, Liu and Wang2007; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wang, Zhu, Mann, Herten and Lücke2011, Reference Zhao, Jia, Min and Zhu2015, Reference Zhao, Zhang, Jia, Shen and Zhu2021). This formation includes three species of eurypterids: Malongia mirabilis Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Xue, Lamsdell and Selden2022; Parahughmilleria fuea Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023; and Pterygotus wanggaii Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023. However, the ecology and detailed morphologies of Chinese pterygotids remains a mystery due to the rarity of their fossils as well as their poor preservation.

Despite the wide distribution and diversity of pterygotids, identifications of their cheliceral morphologies have been somewhat confusing in previous research (e.g., Ciurca and Tetlie, Reference Ciurca and Tetlie2007; Miller, Reference Miller2007; Wang and Gai, Reference Wang and Gai2014; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023). As such, a new nomenclatural framework is proposed for the cheliceral dentition based on their relative position, which maximizes interauthor consistency and reproducibility. In the current contribution, we apply this framework to newly collected pterygotid specimens assigned to Erettopterus qujingensis and Pterygotus wanggaii from the Xiaxishancun Formation, and interpret their ecology—how different pterygotids coexisted in the same area and how they utilized their chelicerae for predation.

Geological setting

The Xiaxishancun Formation, ~51 m thick, is characterized by yellow sandstone and green shale from a continental deposit, and yields abundant fish remains (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Giles, Friedman and Zhu2017), some early land plants (Xue, Reference Xue2012), and arthropods (Lamsdell and Selden, Reference Lamsdell and Selden2013; Selden et al., Reference Selden, Lamsdell and Qi2015; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023). Based on the miospore assemblage, this formation is considered early Lochkovian in age (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Xue, Liu and Wang2007; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wang, Zhu, Mann, Herten and Lücke2011, Reference Zhao, Jia, Min and Zhu2015, Reference Zhao, Zhang, Jia, Shen and Zhu2021). The Streelispora newportensis–Chelinospora cassicula Assemblage Biozone (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Cai, Wang, Li, Gao, Wang, Geng and Wang1994; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Xue, Liu and Wang2007) approximately corresponds to the Emphanisporites micrornatus–Streelispora newportensis Assemblage Biozone of the Lochkovian age (Richardson and McGregor, Reference Richardson and McGregor1986; Fang et al., Reference Fang, Cai, Wang, Li, Gao, Wang, Geng and Wang1994; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Xue, Liu and Wang2007). Additionally, carbon isotope analyses revealed that positive δ13Corg shifts occurred and reached a peak value of −25.2 % in the lowest part of the Xiaxishancun Formation (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wang, Zhu, Mann, Herten and Lücke2011, Reference Zhao, Jia, Min and Zhu2015, Reference Zhao, Zhang, Jia, Shen and Zhu2021), corresponding to a global positive shift from the uppermost Silurian to the lowermost Devonian. The study area is situated in close proximity to the Kudangtang reservoir (24.869415°N, 103.080886°E) near Yiliang County (Fig. 1.1), Kunming City; the specimens were excavated from the lower part of the Xiaxishancun Formation (Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1. Geological setting of the excavation site in Qujing City: (1) site where fossils were excavated; (2) geological setting of the Xiaxishancun Formation, with the specific layer where pterygotid materials were excavated. Scale bar = 2 km.

Materials, methods, and abbreviations

Materials

All specimens are deposited in the Dalian Shell Museum, Dalian, Liaoning Province, China, and designated with unique serial numbers: DS (Dalian Shell Museum) + specific morphological structure (e.g., cmf, cheliceral movable finger) + date of excavation (in YMD) + positive/negative parts (a/b).

We tentatively assigned the chelicera (DS-cmf20230426a-b) and the coxa (DS-sac20230426a-b) to the same species, because they were excavated from the same layer of the same deposit (Site 1); it is possible that they even belong to the same individual. Three more cheliceral specimens (DS-c20240508, DS-cmf20240508, DS-cff20240513) were excavated from a nearby deposit (Site 2) close to Site 1. However, given their distinctive cheliceral dentition compared with the earlier specimen, they were considered heterospecific. Additional tergites (DS-t0120230907a-b, DS-t0220230907a-b, DS-t0320230907) and fragmentary chelicerae (DS-cff20230907a-b) were excavated from a slightly more distant location (Site 3), which were tentatively deemed conspecific with specimens from Site 1 considering the overall location proximity and matrix property.

Methods

Fossils were retrieved with a 20 oz Estwing Brick Hammer and cleaned with a small chisel. Photographs were taken vertically from above by focus stacking, using a Canon 5DSR with Sigma 70 mm F2.8 macro lens, mounted onto an MJKZZ stacking rail. For the median denticles of DS-cmf20230426a and DS-cff20230907a, a Laowa 25 mm F2.8 macro lens was used in combination with Kenko extension tubes. Photographs were captured in RAW files, converted to TIFF files, and then stacked in ZereneStacker (https://zerenesystems.com/) using the PMax algorithm. The resulting images were then modified in Adobe Photoshop©, underwent cropping, rotation, and optical parameter adjustments (e.g., contrast, brightness). The photograph of IVPP-I4593 was emended from that by Wang and Gai (Reference Wang and Gai2014).

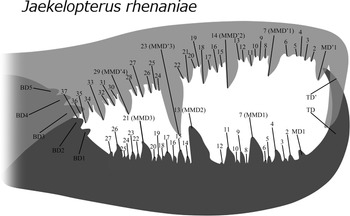

Terminology for cheliceral dentition follows the new nomenclatural framework already applied by Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Lamsdell, Wang, Chen, Selden and He2025). Specifically, it includes three major denticle types: terminal denticle, basal denticle, and median denticles (including ordinary median denticles and modified median denticles) (Fig. 2), which will be detailed in the discussion section.

Figure 2. Nomenclature of cheliceral dentition based on the current methodology. Median denticles (MD) are here defined as the denticle row containing all denticles on the cheliceral finger (like MMD, modified median denticle), with the exception of the terminal denticle (TD) and the basal denticle (BD). Figure reconstructed by Junyi Chin based on the Willwerath chelicera from Jaekelopterus rhenaniae described by Braddy et al. (Reference Braddy, Poschmann and Tetlie2008).

Length and width measurements of lunules represent the distances from the edge of each lunule parallel and perpendicular to the body axis respectively. Analysis of the morphological difference between Pterygotus wanggaii and Erettopterus qujingensis was based on two main parameters: denticle BW and the linear distance between MMD1 and MMD2 (and MMD’1 and MMD’2) on cheliceral fingers. We only included the BW of the MMD (and MMD’) because the ML of MMD (and MMD’) was affected by the taphonomy in some specimens, introducing potential biases that could cause errors to our result. On the contrary, the BW of those denticles was easier to measure, being more stable in their preservation. A scatter plot was introduced to visualize the BW ratiometrics between MMD1 and MMD2 (and MMD’1 and MMD’2), along with those between the BW of one MMD (and MMD’) and the distance between its adjacent MMD (and MMD’) (Fig. 10). Silhouettes in different colors on the graph represent different specimens (Fig. 10). We assumed that different pterygotid species tended to show different ratiometrics in terms of their MMD (and MMD’) BW as well as their relative distance. In that case, this could be the most reliable method to identify pterygotid species. Because some data from GMG20211001003, IVPP-I4593, and YN-415005 were absent from the original literature, we have remeasured those data based on the figures provided in the original paper. The actual measurements of specimens were rounded up to two decimal places in our paper and graph, whereas the ratiometrics shown in the graph (Fig. 10) were rounded up to three decimal places. All specimen measurements are in millimeters (mm) unless otherwise stated.

Abbreviations

BD, basal denticle; BW, base width; BW i, base width of the ith MMD (movable finger) or MMD’ (fixed finger), the ‘i’ stands for ‘item in the sequence’ (e.g. when i = 1, it refers to the first item); c, chelicera; cff, cheliceral fixed finger; cmf, cheliceral movable finger; CMFL, cheliceral movable finger length; d, distance between the 1st and 2nd MMDs; MD, median denticle (= MMD + OMD); ML, maximum length; MMD, modified median denticle; MW, maximum width; OMD, ordinary median denticle; PD, proximal denticle; sac, swimming appendage coxa; t, tergite; TBL, total body length; TD, terminal denticle; te, telson. Denticles on the fixed finger (e.g., MD’) were separated from those on the movable finger (MD) by a prime at the upper right corner.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Types, figures, and other specimens examined in this study are deposited in the following institutions: Dalian Shell Museum (DS), Dalian, Liaoning province, China; Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH), Chicago, Illinois, USA; Geological Museum of Guizhou (GMG), Guiyang, Guizhou province, China; Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Beijing, China; Landessammlung für Naturkunde (LS), Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany; Royal Ontario Museum (PWL), Toronto, Canada; and Southwest Petroleum University (YN), Chengdu, Sichuang Province, China.

Systematic paleontology

Order Eurypterida Burmeister, Reference Burmeister1843

Superfamily Pterygotioidea Clarke and Ruedemann, Reference Clarke and Ruedemann1912

Family Pterygotidae Clarke and Ruedemann, Reference Clarke and Ruedemann1912

Pterygotidae gen. indet. sp. indet

Occurrence

Examined locality: lower middle part of the Xiaxishancun Formation, between the second layer of siltstone and the second layer of shale. Excavated near a lake in proximity to the Kudangtang Reservoir (24.869415°N, 103.080886°E), close to Qujing City, Yunnan, southwestern China (Fig. 1.1).

Description

DS-t0120230907a-b is a pair of partially preserved, black tergites in yellow siltstone (Fig. 3.1, 3.2), retaining dense lunules varying in length (0.92–3.56) and width (0.37–0.68).

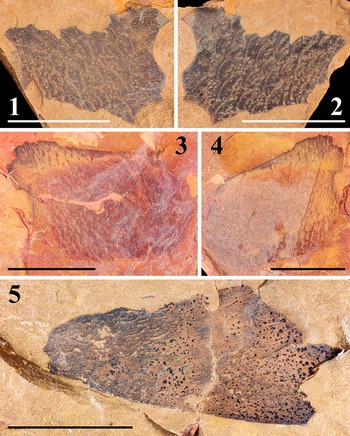

Figure 3. Tergite fragments assigned as unidentified pterygotid: (1, 2) tergite fragments in negative (1; DS-t0120230907b) and positive (2; DS-t0120230907a) parts; (3, 4) tergite fragments in positive (3; DS-t0220230907a) and negative (4; DS-t0220230907b) parts; (5) single tergite fragment (DS-t0320230907). Scale bars = 10 mm.

DS-t0220230907a-b is a pair of partially preserved, red tergites in orange siltstone (Fig. 3.3, 3.4), retaining dense lunules varying in length (0.30–1.69) and width (0.06–0.3).

DS-t0320230907 is a partially preserved, black tergite in yellow siltstone (Fig. 3.5), retaining a few broader lunules varying in length (0.54–1.72) and width (0.18–0.30).

Remarks

All specimens reported herein can be assigned to medium-sized pterygotids given the dense lunules on the tergites. The key identification of Pterygotidae can be stated as follows: carapace round to trapezoid, with large, ovoid, marginal eyes; ventral shields broad; chelicera large, elongated, with numerous large denticles; walking legs slender, cylindrical, undifferentiated, without spines; swimming legs proportionately small; genital appendage unsegmented, type A appendage spatulate (club-shaped), type B appendage expanded elliptical (diamond-shaped); metastoma ovoid, notched anteriorly; telson paddle-shaped; body surface covered in large lunules (emended from Miller, Reference Miller2007).

Genus Pterygotus Agassiz, Reference Agassiz and Murchinson1839

Type species

Pterygotus anglicus Agassiz, Reference Agassiz1844.

Pterygotus wanggaii Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023

Figure 4. Chelicerae specimens assigned as Pterygotus wanggaii Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023: (1, 2) cheliceral movable finger, positive (1; DS-cmf20230426a) and negative (2; DS-cmf20230426b) parts; (3, 4) cheliceral fixed finger, positive (3; DS-cff20230907a) and negative (4; DS-cff20230907b) parts; (5, 6) MMD of cheliceral movable (5; DS-cmf20230426a) and fixed (6; DS-cff20230907a) finger. Scale bars = 5 mm (5, 6); 10 mm (1−4).

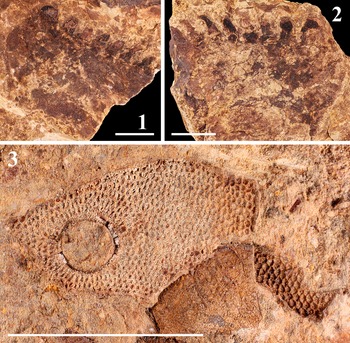

Figure 5. Coxa of Pterygotus wanggaii Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023 and fragment of Polybrachiaspida preserved alongside the chelicera: (1, 2) coxa of swimming appendage assigned as Pterygotus wanggaii, negative (1; DS-sac20230426b) and positive (2; DS-sac20230426a) parts; (3) head fragment of Polybrachiaspida preserved alongside DS-cmf20230426a. Scale bars = 10 mm (1, 2); 20 mm (3).

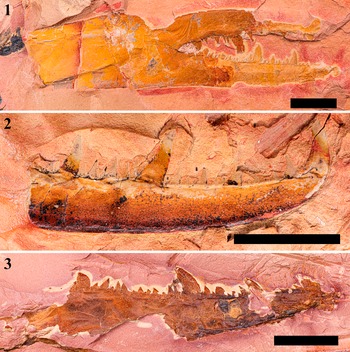

Figure 6. Chelicera specimens assigned as Erettopterus qujingensis Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022: (1) chelicera, DS-c20240508; (2) chelicera fixed finger, DS-cmf20240508; (3) chelicera movable finger, DS-cff20240513. Scale bars = 5 mm (1, 2); 10 mm (3).

Figure 7. Outline sketch of the cheliceral specimens of Pterygotus wanggaii Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023: (1, 2) DS-cmf20240426a, outline sketch on the original specimen (1) and separately (2); (3, 4) GMG 20211001003, outline sketch on the original specimen (3) and separately (4); (5, 6) IVPP-I4593, outline sketch on the original specimen (5) and separately (6). Scale bars = 10 mm.

Type specimens

Holotype, GMG 20211001003; paratypes, GMG 20211001004–8; paratype IVPP–I4593.

Diagnosis

Pterygotus with chelicera bearing three MMD’s (= principal or primary denticles) and six OMDs (≈ intermediate denticles); cheliceral denticles exhibiting size differentiation, bearing ridges; all denticles upright, slightly pointing posteriorly; first MMD located on middle part of finger; third MMD elongate, longer than first MMD (modified from Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023).

Occurrence

Type and examined locality: Lower part of the Xiaxishancun and Xitun formations (Wang and Gai, Reference Wang and Gai2014); Xiaxishan Reservoir (103.698351°N, 103.698351°E) near Qujing City, Yunnan, southwestern China (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023).

Description

DS-cmf20230426a (ML 63.76, BW 19.76) is a cheliceral movable finger preserved in an orangish to yellowish siltstone, with 1 TD and 26 MD’s (including 2 MMD’s). 9 OMD’s present between MMD1 (ML 7.80, BW 3.53) and MMD2 (ML 10.13, BW 4.98); OMD4 posterior to MMD1 is slightly enlarged. Only the anterior section with several MDs was preserved in DS-cmf20230426b (ML 35.78), sharing identical ML and BW of its MMD’s with DS-cmf20230426a (Figs. 4.1, 4.2, 4.5; 7.1, 7.2).

DS-cff20230907a (ML 30.74, BW 6.47) is a partially preserved cheliceral fixed finger in a grey siltstone, missing TD, preserving 9 MD’s, including 1 MMD’ (ML 7.03, BW 1.7). Only a single MMD’ and OMD’ were preserved in DS-cff20230907b (ML 31.72), sharing an identical BW with DS-cff20230907a (Fig. 4.3, 4.4, 4.6).

DS-sac20230426a-b is a pair of partially preserved swimming appendage coxae in a yellow siltstone (Fig. 5.1, 5.2), missing nearly 75% of their original size (a, ML 35.05, BW 27.24; b, ML 38.33, BW 27.51; excluding denticles). Only seven coxal denticles were preserved in DS-sac20230426a and 8 in its counterpart. The eight coxal denticles in DS-sac20230426b, of which only three preserved their tips, were sequentially measured as (ML/BW, in mm): 5.04/5.31, 5.21/4.66, 4.45/4.22, 4.80/4.03, 5.21/3.86, 5.03/3.46, 4.41/3.32, and 4.14/3.29.

Materials

DS-cmf20230426a-b, DS-cff20230907a-b, DS-sac20230426a-b (Figs. 4.1–4.6, 5.1, 5.2, 7.1, 7.2).

Remarks

Two species of pterygotids are known from Qujing City: Erettopterus qujingensis and Pterygotus wanggaii. The movable finger of DS-cmf20230426a bears nine OMDs between MMD1 and MMD2, with OMD5 enlarged after MMD1 (Fig. 7.1, 7.2), similar to the dentitions observed in the holotype (GMG 20211001003) and the first described specimen (IVPP-I4593) of Pterygotus wanggaii (Fig. 7.3–7.6). The overall shape of the cheliceral outline of DS-cmf20230426a also matches the morphology seen in those specimens (Fig. 7). As a result, we assign the chelicera (DS-cmf20230426a-b) and coxa (DS-sac20230426a-b) materials to Pterygotus wanggaii, based on their morphology and locality. Although the condition of cheliceral denticles in DS-cff20230907a-b is quite fragmentary, it has a similar morphology on the edge of MMD2 with that of DS-cmf20230426a (Fig. 4.5, 4.6), and both specimens were discovered from the same formation. Therefore, we tentatively regard them as conspecific.

Genus Erettopterus Salter in Huxley and Salter, Reference Salter, Huxley and Salter1859

Type species

Erettopterus bilobus Salter, Reference Salter1856.

Erettopterus qujingensis Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022

Figure 8. Outline sketch of the cheliceral specimens assigned as Erettopterus qujingensis Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022: (1, 2) DS-cmf20240508, outline sketch on the original specimen (1) and separately (2); (3, 4) DS-c20240508, outline sketch on the original specimen (3) and separately (4); (5, 6) DS-cff20240513, outline sketch on the original specimen (5) and separately (6); (7, 8) YN-415005, outline sketch on the original specimen (7) and separately (8). Scale bars = 5 mm (1−4); 10 mm (5−8).

Figure 9. Telson specimen assigned as Erettopterus qujingensis Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022: (1) original specimen, DS-te20240508; (2, 3) outline sketch on the original specimen (2) and separately (3). Scale bar = 5 mm.

Type specimens

Holotype, YN-415005; paratypes, YN-415001–4, 6–10.

Diagnosis

Erettopterus with cheliceral fixed finger bearing with three MMD’s (= principal or primary denticles) and an acute, inversed TD’; cheliceral denticles exhibiting size differentiation, with MMD’2 being the largest; metastoma broad, oval, with rounded shoulders and deep median notch (modified from Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022).

Occurrence

Only known from the type and examined locality: upper part of the Yulongsi Formation (Přídolí Eopch, the late Silurian), south of Liaojiaoshan area (25.474544°N, 103.696914°E) near Qujing City, Yunnan, southwestern China (emended from Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022).

Description

DS-c20240508 (ML 68.72, BW 12.97) is a chelicera with complete cheliceral manus and both fingers preserved in yellow siltstone (Figs. 6.1, 8.3, 8.4). Movable finger (ML 36.81, BW 7.14) bears 21 MDs (including 2 MMDs; MMD2, ML 3.91, BW 2.21; MMD3, ML 1.97, BW 2.16), missing the anterior section (including TD and a set of MDs [including one MMD]), with posterior section concealed within fixed finger (BDs not visible). Fixed finger (ML 41.94, BW 14.35) bears 39 MD’s (including 3 MMD’s), missing complete TD’; eight OMD’s between MMD’1 (ML 3.1, BW 1.86) and MMD’2 (ML 4.08, BW 2.62); OMD’5 posterior to MMD’1 slightly enlarged; 15 OMD’s between MMD’2 and MMD’3 (ML 1.99, BW 1.83); OMD’1 and OMD’10 posterior to MMD’2 slightly enlarged.

DS-cmf20240508 (ML 14.69, BW 2) is a partially preserved cheliceral movable finger in yellow siltstone (Figs. 6.2, 8.1, 8.2), with TD and 24 MDs (including 3 MMDs, MMD1 incomplete) but missing the posterior section that included all BDs. Nine OMDs between MMD1 (ML 1.26, BW 0.83) and MMD2 (ML 2.76, BW 1.38); OMD4 and OMD8 posterior to MMD1 slightly enlarged; 10 OMDs between MMD2 and MMD3 (ML 1.9, BW 1.07); OMD4 and OMD7 posterior to MMD2 slightly enlarged.

DS-cff20240513 (ML 53.1, BW 7.78) is a cheliceral fixed finger preserved in yellow siltstone (Figs. 6.3, 8.5, 8.6), with 1 TD’ and 33 MD’s (including 3 MMD’s). Eight OMD’s between MMD’1 (ML 2.87, BW 2.3) and MMD’2 (ML 5.02, BW 3.01); OMD’5 posterior to MMD’1 slightly enlarged; 15 OMD’s between MMD’2 and MMD’3 (ML 2.36, BW 2.23); OMD’1 and OMD’12 posterior to MMD’2 slightly enlarged.

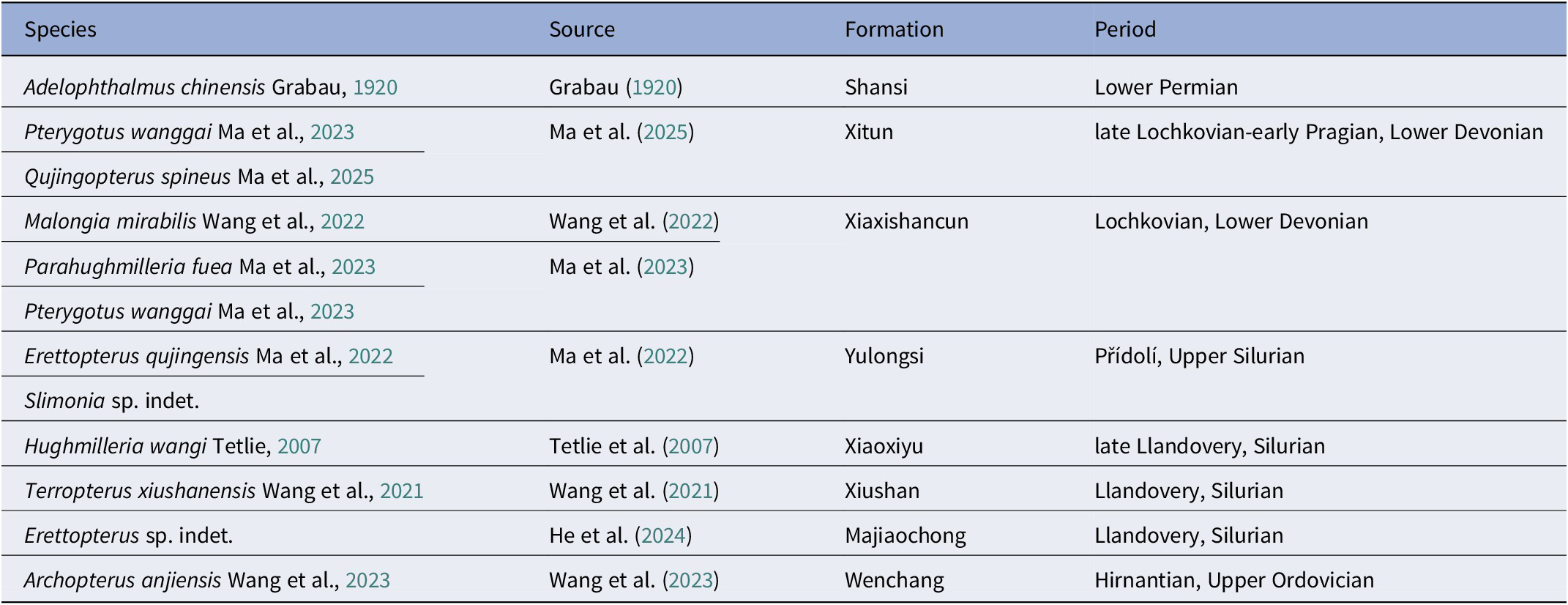

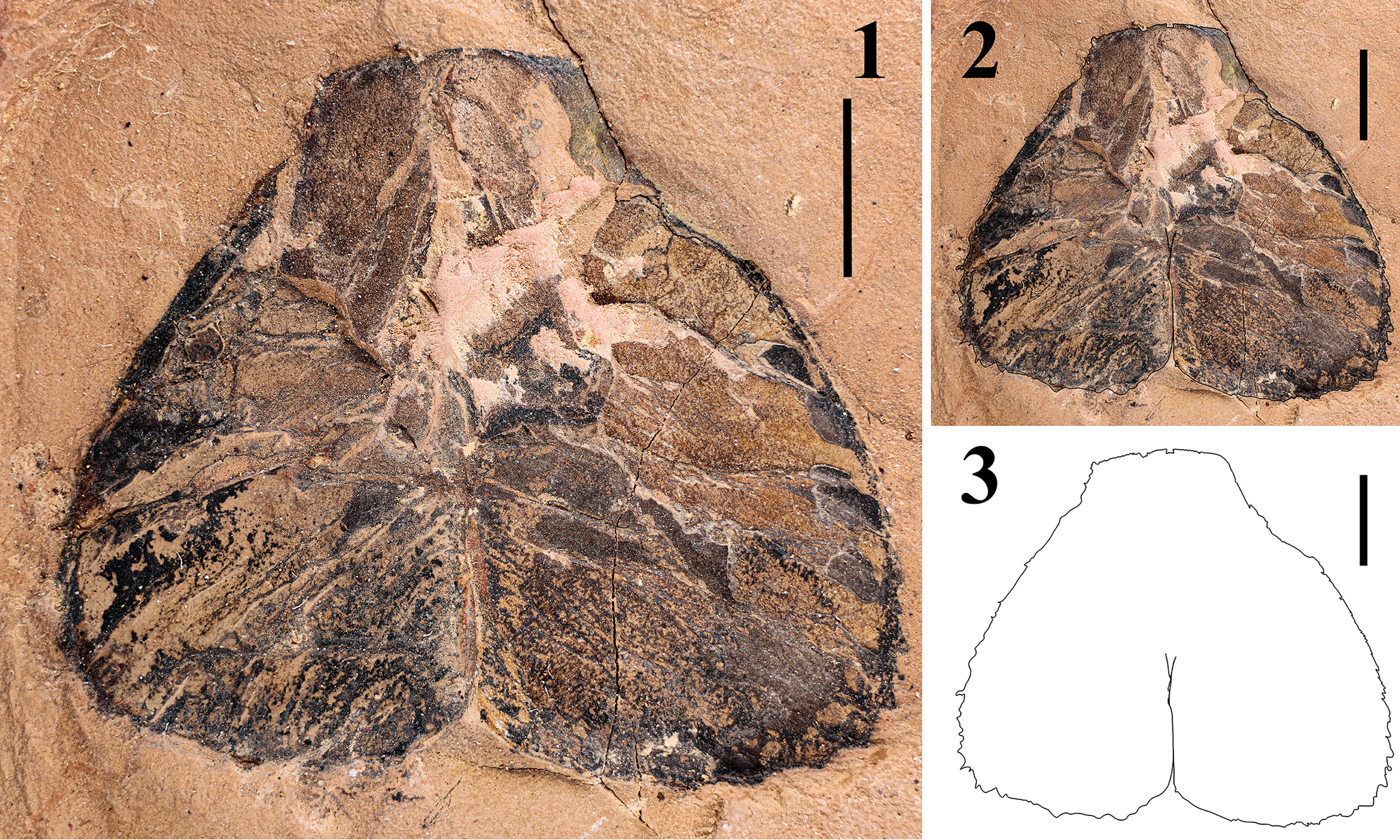

DS-te20240508 (ML 20.52, MW 24.07) is a complete, bilobed telson preserved in yellow siltstone (Fig. 9.1–9.3), with a serrated margin, left lobe bearing 17 denticles, and right lobe bearing 18 denticles.

Materials

DS-t0120230907a-b, DS-t0220230907a-b, DS-t0320230907, DS-c20240508, DS-cmf20240508, DS-cff20240513, DS-te20240508 (Figs. 6.1–6.3, 8.1–8.6, 9.1–9.3).

Remarks

The other three specimens (DS-c20240508, DS-cmf20240508, DS-cff20240513) showed a distinct dentition pattern compared to that of Pterygotus wanggaii by bearing three MMDs (and MMD’s) on each finger with more OMDs after MMD2. After comparing the morphology of the fixed finger in DS-c20240508 and DS-cff20240513 with the holotype of Erettopterus qujingensis, YN-415005 (Fig. 8.7, 8.8), we confirm that the observed dentition matches the pattern seen in the latter. Notably, the fixed finger bears three MMD’s, with an interval of eight OMD’s between MMD’1 and MMD’2, and an interval of 15 OMD’s between MMD’2 and MMD’3; OMD’5 was also slightly enlarged after MMD’1 (Fig. 8.3–8.8). Furthermore, although the original authors claimed that the complete terminal denticle was not preserved in YN-415005 (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022, p. 4), our examined specimens indicate that the TD’ of E. qujingensis terminates in an acute angle, but is relatively small. This suggests that the denticle immediately anterior to the ‘i1’ (sensu Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022, p, 5, fig. 4.1) on YN-415005 is in fact the terminal denticle.

Interestingly, according to our examined specimens, the OMD’ series posterior to MMD’2 exhibits a considerable variation in its denticle enlargement. Specifically, both DS-c20240508 and DS-cff20240513 bear 15 denticles between MMD’2 and MMD’3, and the OMD’ immediately posterior to MMD’2 is enlarged in both specimens. However, another enlarged denticle was located differently on the fixed finger, indexed as OMD’10 on DS-c20240508 and OMD’12 on cff20240513, respectively (Fig. 8.3–8.6). YN-415005 shows a similar condition in denticle enlargement as well, in which its OMD’11 is enlarged (Fig. 8.7, 8.8). These observations imply that the enlarged OMDs are clustered within a specific section in pterygotids’ cheliceral fingers, and it might be a diagnostic feature of Erettopterus qujingensis. However, whether this feature is common among all species remains enigmatic at the current stage due to the scarcity of cheliceral materials.

Lastly, because a bilobed, vertically compressed telson is the key diagnostic feature of the genus Erettopterus (Ciurca and Tetlie, Reference Ciurca and Tetlie2007), we tentatively assign the specimen DS-te20240508 to the telson of E. qujingensis, considering that the dentition of the chelicerae excavated from the same locality matches that of the holotype specimen (YN-415005).

By applying our cheliceral nomenclature, based on the currently examined cheliceral specimens (DS-c20240508, DS-cmf20240508, DS-cff20240513) and the early description for the holotype (YN-415005), in combination with the newly discovered telson specimen (DS-te20240508), the diagnosis of Erettopterus qujingensis is revised as follows: Erettopterus of large size; cheliceral denticles exhibiting size differentiation; movable finger bearing three MMDs, MMD1 and MMD2 with interval of nine OMDs, OMD4 and OMD8 slightly enlarged after MMD1 (Figs. 6.2, 8.1, 8.2); fixed finger ending with acute TD’, bearing three MMD’s, with MMD’2 being largest among all denticles; MMD’1 and MMD’2 with interval of eight OMD’s, OMD’5 slightly enlarged after MMD’1; MMD’2 and MMD’3 with interval of 15 OMD’s, OMD’1 and OMD’10-12 slightly enlarged after MMD’2 (Figs. 6.1c, 8.3–8.8); metastoma broad, oval, with rounded shoulders and deep median notch; telson bilobed, with serrated margin.

Cheliceral dentition nomenclature

The nomenclature of pterygotid cheliceral denticles (or teeth) remains markedly inconsistent across studies, resulting in considerable terminological confusion and inaccuracy (abbreviations coined herein for brevity). As early as Sarle (Reference Sarle1902, p. 1104), the distal end of the cheliceral finger was described as a “stout, striated, nearly perpendicular mucro.” Three types of “subtriangular, striated denticles” were identified based on their relative size to the mucro: the primaries (PD), secondaries (SD), and tertiaries (TD). Clarke and Ruedemann (Reference Clarke and Ruedemann1912, p. 39, 48, 50) redefined the curved ‘mucro’ as a ‘terminal tooth’ (TT). Subsequently, Waterston (Reference Waterston1964, p. 16, fig. 3) proposed a revised classification consisting of three major types of cheliceral teeth: the principal tooth (PT), the intermediate tooth (IT), and the minute intervening tooth (MIT). The PT category encompassed the previously defined TT, characterized by their broader width, longitudinal striations, and inward orientation. These were sequentially labeled as ‘d’ followed by a number indicating their position in a distal-to-proximal sequence. For example, the TT was designated as ‘d1,’ being the first PT. The IT were defined as smaller teeth situated between adjacent PT, whereas the MIT were even smaller structures found between adjacent IT. It is plausible to establish the following equivalences between the already existing terms: TT = mucro (sensu Sarle, Reference Sarle1902), PT = PD (sensu Sarle, Reference Sarle1902), IT = SD (sensu Sarle, Reference Sarle1902), MIT = TD (sensu Sarle, Reference Sarle1902). However, in the same work, Waterston (Reference Waterston1964, p. 21) introduced yet another confusing term while discussing Pterygotus anglicus (see Waterston, Reference Waterston1964, fig. 4): the ‘primary median tooth’ (PMT), or ‘a primary tooth in the middle’ of the cheliceral movable finger, with a corresponding counterpart on the fixed finger. Because he essentially retained the terms IT and MIT for this species, it is likely that this ‘primary tooth’ (not in the same sense as Sarle’s ‘primary denticle’) represents a specialized PT (or Sarle’s PD), although he did not provide an unambiguous definition. One month later in the same year, Kjellesvig-Waering (Reference Kjellesvig-Waering1964) adopted the terms TT (Kjellesvig-Waering, Reference Kjellesvig-Waering1964, p. 347–349, 356, 357) and PT (Kjellesvig-Waering, Reference Kjellesvig-Waering1964, p. 349, 355) while introducing another novel term, the central tooth (CT) (Kjellesvig-Waering, Reference Kjellesvig-Waering1964, p. 346, 348, 349, 356, 357), which could in reality correspond to the PMT coined by Waterston (Reference Waterston1964). Unfortunately, none of his diagrams explicitly labeled or distinguished these different tooth types (Kjellesvig-Waering, Reference Kjellesvig-Waering1964, p. 338, 347, 350). In fact, in his earlier work Kjellesvig-Waering (Reference Kjellesvig-Waering1961, p. 82) had already defined the principal denticle as a single, centrally positioned tooth on the movable finger—being the largest—practically equivalent to the PMT (sensu Waterston). In Acutiramus, the most elongated oblique denticle on the fixed cheliceral finger was referred to as the ‘master denticle’ by Laub et al. (Reference Laub, Tollerton and Berkof2010). Chlupáč (Reference Chlupáč1994, fig. 1) followed the terminological framework proposed by Waterston (Reference Waterston1964), recognizing the TT (Chlupáč, Reference Chlupáč1994, p. 147, 148, 151–153) as a subtype of PT (Chlupáč, Reference Chlupáč1994, p. 148–152). However, he did not adopt the two other terms (IT and MIT), but instead likely subsumed them under a single category, referring to them as ‘smaller’ or ‘small’ teeth (Chlupáč, Reference Chlupáč1994, p. 148, 151, 152). Additionally, he sporadically renamed the PT as the ‘main tooth’ (Chlupáč, Reference Chlupáč1994, p. 150, 152).

More recently, cheliceral teeth have been referred to as ‘denticles’ (e.g., Ciurca and Tetlie, Reference Ciurca and Tetlie2007; Miller, Reference Miller2007), although inconsistencies and confusion persist across these works. Miller (Reference Miller2007) employed four categories: terminal (td), principal, primary, and intermediate denticles. The terminal denticle corresponds to the ‘terminal tooth’ of Clark and Ruedemann (Reference Clarke and Ruedemann1912) and Waterston (Reference Waterston1964), referring to the distal curvature. However, unlike Waterston’s scheme, Miller (Reference Miller2007, p. 987) treated the terminal denticle as a separate category, distinct from the principal denticle (= ‘principal tooth,’ sensu Waterston, Reference Waterston1964). In contrast, he followed Waterston (Reference Waterston1964) in identifying an enlarged central denticle as the ‘primary denticle’ (d1). His definition of ‘intermediate denticles’ (dn, in which n takes integers ≥ 2, with denticles ordered from distal to proximal and skipping d1) diverged from Waterston’s (Reference Waterston1964) concept, and based on his description and diagram (Miller, Reference Miller2007, p. 987, fig. 5), these essentially correspond to the remaining ‘principal teeth’ aside from td and d1. Miller (Reference Miller2007) did not clearly define the ‘principal denticle,’ a term mainly used in his figure captions, but it likely encompassed both the ‘primary’ and ‘intermediate’ denticles. Likewise, Ciurca and Tetlie (Reference Ciurca and Tetlie2007) inconsistently used two terms for the same structure: ‘terminal denticle’ (Ciurca and Tetlie, Reference Ciurca and Tetlie2007, p. 727, 731, 732) and ‘distal denticle’ (Ciurca and Tetlie, Reference Ciurca and Tetlie2007, p. 727, 732, 734). They adopted the term ‘principal denticle’ but did not retain its subtype, the ‘primary denticle.’ Notably, the authors avoided complex denticle abbreviations in their diagrams, instead using En (with n taking integers, labeled in an apparently arbitrary order) and Ed to denote, respectively, the principal and distal denticles of their target taxon, Erettopterus. Nevertheless, they similarly specified the largest principal denticle (‘large central denticle’; Ciurca and Tetlie, Reference Ciurca and Tetlie2007, p. 732) as E1, analogous to d1 of Miller (Reference Miller2007). In contrast to prior studies, the identification of principal denticles in their work does not consistently correlate with conspicuous size enlargement (Ciurca and Tetlie, Reference Ciurca and Tetlie2007, fig. 3). Both IT and MIT seemed to be completely obliterated and were instead referred to collectively as ‘small denticles’ (Ciurca and Tetlie, Reference Ciurca and Tetlie2007, p. 727).

Most subsequent works claimed to follow the terminology proposed by Miller (Reference Miller2007)—specifically, treating the largest principal denticle as the primary denticle. To begin with, Lamsdell and Legg (Reference Lamsdell and Legg2010, fig. 1) adopted the abbreviations td and d, while introducing a new abbreviation (i)—one absent in Miller’s original work—to denote intermediate denticles. However, as deduced above, the ‘intermediate denticles’ were originally defined as the principal teeth (sensu Waterson, Reference Waterston1964) that exclude TT and PMT. In other words, both intermediate and primary denticles were subsumed under the category of principal denticles in Miller’s (Reference Miller2007) system. In contrast, those alleged ‘intermediate denticles’ identified by Lamsdell and Legg (Reference Lamsdell and Legg2010) were conspicuously smaller than those labelled d, which they separately termed as ‘principal denticles.’ Thus, their framework effectively recognized three main types of denticles: terminal denticle, principal denticles (including the single primary denticle as a subtype), and intermediate denticles. This same framework was later adopted by Lamsdell and Selden (Reference Lamsdell and Selden2013). A typographical error appeared in the work by Lomax et al. (Reference Lomax, Lamsdell and Ciurca2011), who also cited Miller (Reference Miller2007) but mistakenly referred to the ‘principal denticle’ as the ‘principle denticle’. Because their study included no diagrams, it remains uncertain whether they correctly interpreted and applied the original definitions. Other confusions emerged in more recent studies that also asserted to follow Miller (Reference Miller2007). Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022) essentially adopted the framework modified by Lamsdell and Legg (Reference Lamsdell and Legg2010) but simultaneously introduced a synonymous term for the terminal denticle— ‘distal denticle’ (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022, p. 3). More confusingly, they used the terms ‘principal’ and ‘primary’ denticles interchangeably (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022, p. 4), sometimes treating them as synonyms (e.g., “between the primary denticles,” “third primary denticle”), and at other times suggesting a hierarchical relationship [i.e., primary as a subtype; “Primary denticle (d1´),” “Anterior principal denticle (d2´),” “Third principal denticle (d3´)”]. This conflation of terminology—treating ‘primary’ as synonymous with ‘principal’—was radically perpetuated by Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023). To illustrate, both ‘primary’ and ‘principal’ were applied to d1 (or d1´) and d3 (or d3´), whereas d2 was solely referred to as the ‘anterior principal denticle’ (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022, p. 3, 4).

Both terminologies (principal or primary), despite their original referential difference (one as a specific type of another), invite interpretative ambiguity and reflect subjectivity in definition. For example, the adjective ‘principal’ (or ‘primary’, if considered synonymous), although not explicitly explained in its original source (Waterston, Reference Waterston1964), could imply a crucial ecological function of the designated denticles, which can be justified by recognizing them as the main contributors to puncture and fixation during predation. Conversely, one could equally argue that the smaller denticles that constitute the majority of the denticle count should instead be considered ‘principal’ (or ‘primary’, if synonymous). More plausibly, the original definition of principal or primary denticles was based on their size relative to other denticles—although this was not always consistently applied, because some subsequent works included smaller denticles within this category. Ultimately, however, the central issue lies in the lack of reproducibility in identifying these denticle types. No published work has systematically clarified the unambiguous distinction between ‘intermediate’ and ‘principal’ (or ‘primary’, if synonymous) denticles (sensu Lamsdell and Legg, Reference Lamsdell and Legg2010), and these were most likely identified by perceptual judgment rather than more objective quantitative criteria.

To address the persistent inconsistency and lack of objectivity in cheliceral denticle terminology, the third author of this study previously proposed a new terminological framework as an external advisor, which has been already applied by Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Lamsdell, Wang, Chen, Selden and He2025). This scheme was based on the cheliceral nomenclature developed by Soleglad and Fet (Reference Soleglad and Fet2003, p. 29, 30, 32) for the order Scorpiones (a phylogenetic relative of eurypterids; Tetlie, Reference Tetlie2004), which was modified to accommodate the distinct morphological characteristics of pterygotid chelicerae, in which all pterygotids possess a single row of cheliceral denticles, in contrast to the two rows found in scorpions. This provisional system introduced four denticle types: terminal denticle (TD), median denticle (MD), modified median denticle (MMD), and proximal denticle (PD). Following a more thorough review of additional historical literature on pterygotid chelicerae during the current investigation, a refined framework has now been established. Specifically, three fundamental types of denticle are defined based on their relative position along the movable finger of the chelicera: a single (or occasionally double) terminal denticle (TD), a series of median denticles (MDs), and a series of basal denticles (BDs). In cases where one or more MDs are notably elongated or more robust than usual, they are specified as ‘modified median denticles (MMDs)’, whereas the remaining MDs are automatically termed ‘ordinary median denticles (OMD)’. All BDs (= ‘axial denticles’, sensu Laub et al., Reference Laub, Tollerton and Berkof2010) are unequivocally confined to the proximal flange (sensu Laub et al., Reference Laub, Tollerton and Berkof2010) unique to the movable finger (absent from the fixed finger) and strongly angled against the finger axis. Hence, the fixed finger entails only two basic types (TD’ and MD’) with one comprising two subtypes (MMD’ and OMD’). The enumeration of MDs follows a ‘distal-to-proximal’ sequence with subscripts denoting their order (Fig. 2): the most distal MD is designated as the first, with the same for MMDs, OMDs, and BDs. All MMDs are incorporated within the MD series, because MMDs are essentially specialized MDs (assuming MDs are homologous precursors of MMDs). For instance, MMD2 is equivalent to MD13 on the movable finger specimen of Jaekelopterus rhenaniae (Jaekel, Reference Jaekel1914). In the presence of MMDs, OMDs are enumerated following the same sequence by skipping MMDs. The present framework differs from the earlier one in several key aspects: the term distal denticle (DD) has been replaced with terminal denticle (TD) due to the prevalent usage of the latter and the unnecessary introduction of the former (albeit already seen on other works); proximal denticle (PD) has been revised to basal denticle to avoid potential confusion with principal or primary denticle; median denticle (MD) is now treated as a family category encompassing two subtypes (MD sensu Ma et al., Reference Ma, Lamsdell, Wang, Chen, Selden and He2025 is equivalent to OMD); the enumeration is treated separately for MD and its two subtypes. Additionally, the semantic pairing of ‘terminal’ and ‘basal’ is more appropriate and conceptually coherent, whereas ‘distal’ typically pairs with ‘proximal’.

A key feature of our nomenclatural framework lies in the quantitative identification of MMD, which aims to ensure reproducibility across authors, based on the relative size of denticles compared with the majority of MDs. Fossils are inherently susceptible to taphonomic distortion, and not all retain their original form from when the organism was alive. To minimize subjectivity, we invoked the maximum parsimony principle by taking into account only the preserved contour of the denticle. All MDs (including potential MMDs) are first measured for their maximum length (ML) and base width (BW), with average values subsequently calculated for each metric. Denticles that exceed both the average ML and BW but are not smaller than one-quarter of the second-largest BW measured are classified as MMDs. However, this approach can lead to the underestimation of these metrics if the preserved contours are highly irregular or incomplete. At present, it is beyond our capacity to implement a more accurate methodology in which the authenticity is maximized by deriving ML and BW after reconstructing denticles, because this would require an empirical reference system grounded in a sufficiently large sample of well-preserved pterygotid cheliceral fossils. Furthermore, the first MD posterior to the terminal denticle (TD or TD’) should not be recognized as an MMD in any case to avoid confusion, because its shape can be highly variable.

One could argue that the introduction of those new terms (MD, MMD, OMD) is unnecessary, because the core issue of lacking reproducibility could ostensibly be resolved by applying the new quantification method to the existing terms (i.e., principal and intermediate denticles). This is a valid point; however, these new terms maintain logical consistency with other elements of the revised terminology, because all three basic types are defined based on positional relationships rather than relative size or presumed ecological function. Moreover, the hierarchical terminology—in which MMD and OMD are nested within MD—implicitly conveys a homology assumption. In cases in which no discernible MMD is present, all denticles (except TD and BD) can simply be classified as MD (the family type), without losing diagnostic designation. That said, we acknowledge that both the prior and present classification systems—which rely heavily on relative denticle size—can be influenced by preservation integrity and ontogenetic variation of the chelicerae. Furthermore, the numerical thresholds applied in this study are admittedly arbitrary to some extent, and further tests are required to confirm its applicability across all eurypterids in which the MMD delimited via quantification aligns with the naive judgement based on cursory visual inspection. Nevertheless, our aim is not to eliminate subjectivity entirely, but rather to improve reproducibility, reducing the reliance on inconsistent individual interpretations across different researchers.

Morphological difference between Erettopterus qujingensis and Pterygotus wanggaii

Beyond differences in cheliceral dentition, the ratiometric of the major denticles (MMDs and MMD’s) reveal notable distinctions between the two pterygotid species. In Pterygotus wanggaii, the BW proportions of MMD1 and MMD2 (and MMD’1 and MMD’2) are close to 1, suggesting that these denticles are approximately equal in size. Specifically, Pterygotus wanggaii exhibits a larger BW ratio between MMD1 and MMD2 on both the movable and fixed fingers (Fig. 10.1, 10.2), indicating that MMD1 is relatively more robust in this species compared to Erettopterus qujingensis. In contrast, Erettopterus qujingensis shows a noticeably smaller BW ratio between MMD’1 and MMD’2, and its MMD’ distance ratio is relatively larger, indicating that MMD’2 is significantly wider than MMD’1 (Fig. 10.2).

Figure 10. Scatter plots showing the ratiometric differences (BW1/ BW2; BW1/d; BW2/d; the same as fixed fingers) in Xiaxishancun Formation pterygotids: (1) movable finger; (2) fixed finger, denoted with a prime. Silhouettes: red = DS-cmf20240508a (Erettopterus qujingensis Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022); light orange = DS-cmf20230426a (Pterygotus wanggaii Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023); gray = GMG 20211001003 (Pterygotus wanggaii); gold = IVPP-I4593 (Pterygotus wanggai); yellow = DS-c20240508 (E. qujingensis); dark orange = DS-cff20240513 (E. qujingensis); black = YN-415005 (E. qujingensis). BW, base width; d, distance between the 1st and 2nd MMDs.

However, because our analysis of Erettopterus qujingensis is based on a single specimen with a rather incomplete denticle row (DS-cmf20240508) that is missing the posterior section, the ratiometrics for this species should be interpreted cautiously. Comparatively, the cheliceral morphology of DS-cmf20230426a (assigned to Pterygotus wanggaii) provides a more reliable reference (Fig. 10.1). Therefore, we conclude that Erettopterus qujingensis possesses a proportionally larger MMD’2 compared to Pterygotus wanggaii, whereas MMD’1 and MMD’2 in Pterygotus wanggaii are nearly equal in width (Fig. 10). We opted to measure the base width of MMD (and MMD’) rather than maximum length to quantify cheliceral morphology because complete denticle structures are rarely preserved in pterygotid fossils. Additionally, the length and curvature of these denticles can be affected by taphonomic processes. Smaller individuals, with their thinner cuticles, are more prone to postmortem deformation, which can alter the apparent orientation of cheliceral denticles. This variation in preservation is evident when comparing the smaller holotype YN-415005 (Fig. 8.7, 8.8) to the larger specimen DS-cff20240513 (Figs. 6.3, 8.5, 8.6). Consequently, we advocate against using MMD (and MMD’) curvature as a diagnostic character in smaller specimens. Due to the fragmentary nature of the chelicerae assigned to Pterygotus wanggaii, the diagnostic feature of Pterygotus wanggaii will be limited to: ‘movable finger bearing two MMDs, MMD1 and MMD2, with an interval of nine OMDs, OMD4 slightly enlarged after MMD1’, based on our methodology.

Variation in pterygotids’ cheliceral denticles

In previous papers, various researchers claimed that their pterygotid specimens had experienced ontogenetic allometry in their cheliceral denticles (e.g., Braddy et al., Reference Braddy, Poschmann and Tetlie2008; Lamsdell and Selden, Reference Lamsdell and Selden2013). Lamsdell and Selden (Reference Lamsdell and Selden2013) noted that the cheliceral denticles in Jaekelopterus howelli (Kjellesvig-Waering and Størmer, Reference Kjellesvig-Waering and Størmer1952) exhibited ontogenetic allometry based on an elongated ‘intermediate denticle’ (hereafter referred to as the ‘stiletto’) from a cheliceral fossil FMNH PE 9436 (Lamsdell and Selden, Reference Lamsdell and Selden2013, p. 24, fig. 17a, p. 36, fig. 24b–d). However, whether other cheliceral denticles will form a ‘stiletto’ is highly suspicious in pterygotids. Indeed, such a slender structure would easily fracture during hunting, and those pterygotids would face a hard time accommodating this long denticle without growing a specialized furrow or sheath on the opposing finger. Yet no such structure has been described in J. howelli or other pterygotids. A thin, delicate denticle is unlikely to represent sexual dimorphism, as such a characteristic is absent in other pterygotids as well as in nonpterygotid eurypterids. It would be hard to imagine how pterygotids would apply this structure for mating or any behavior associated with intraspecific competition. Therefore, we argue that the allometry of the rapidly growing ‘intermediate denticle’, which forms into a ‘stiletto’, is highly dubious in pterygotids given its abnormal morphology and unknown function. The ‘stiletto’ in FMNH PE 9436 might be taphonomic, considering its rarity and the fact that it is a separated section from the chelicera (Lamsdell and Selden, Reference Lamsdell and Selden2013, fig. 17a). In fact, Braddy (Reference Braddy2022) has already argued that the elongated denticle is evidently a misidentification of a piece of cuticle or plant matter rather than a cheliceral denticle.

However, because fossil records of intact exuviae encompassing the entire ontogenetic history are unknown for any pterygotid, it is impossible to determine the specific instar of a presumably immature cheliceral specimen because the size variation range of each instar is unknown. Theoretically, a large, immature individual of a penultimate instar might have a different BW2/d (base width of MMD2/distance between two MMDs) ratio compared with that of adults, even if they are similar in size, considering the possible allometry in cheliceral morphology (Braddy et al., Reference Braddy, Poschmann and Tetlie2008). Although the ratio of BWi and d in DS-cmf20230426a is distinct compared with GMG 20211001003 and IVPP-I4593 (Fig. 10.1), it is possible that this specimen is a large immature individual, given it similar cheliceral morphology. However, due to its fragmentary nature, it could be taphonomic as well. In that case, DS-cmf20230426a-b might correspond to a freshly molted individual that died and was washed to the nearshore region. The scattered cheliceral and denticle margins, along with the unnatural bending of the TD, illustrate that the specimen was soft before it was fossilized (Figs. 4.1, 4.2, 7.1, 7.2). The soft finger might have been reshaped during the fossilization process after it was dismantled from the chelicera. Despite the fact that the number of OMDs (and OMDs’) between adjacent MMDs (and MMDs’) was relatively constant based on observed specimens, the pattern of enlargement of OMD (and OMD’) showed considerable variability. Most of the enlarged denticles clustered in a certain range of positions (e.g., OMD’10–12 after MMD’2 on the fixed finger), rather than being ontogenetically invariant like the number of OMDs (OMDs’) between adjacent MMDs (and MMDs’) or the relative position of MMDs themselves. Pterygotids might have centralized the enlarged OMD to a specific position between their adjacent MMDs for predatory needs, implying possible identifications of different species based on those dentition patterns—provided that complete cheliceral specimens are available.

Ecology of pterygotids in the Xiaxishancun Formation

Ecologically, pterygotids have long been considered active predators (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Lamsdell, Poschmann, Anderson and Briggs2015; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023). Early interpretations described them as nektonic organisms, capable of actively chasing down prey and capturing them with their chelicerae once within striking range (Clarke and Ruedemann, Reference Clarke and Ruedemann1912; Trewin and Davidson, Reference Trewin and Davidson1996). Poschmann et al. (Reference Poschmann, Schoenemann and McCoy2016) further suggested that Jaekelopterus rhenaniae was an agile hunter, based on analyses of its visual acuity. More recent studies, however, have portrayed pterygotids as relatively slow swimmers, suggesting that they might have approached prey more gradually before snapping at them (Bicknell et al., Reference Bicknell, Kenny and Plotnick2023; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023). This reinterpretation might be ecologically reasonable, given that many of their presumed prey (e.g., pteraspids and osteostracans) were also slow swimmers protected by heavy armor (Morrissey et al., Reference Morrissey, Braddy, Bennett, Marriott and Tarrant2004, Reference Morrissey, Janvier, Braddy, Bennett, Tarrant and Marriott2006). As such, high speed and agility might not have been crucial for pterygotids, even if they operated as pursuit predators. Braddy (Reference Braddy2023, table 1) further observed that armored fish commonly co-occurred with certain pterygotids, particularly Pterygotus and Jaekelopterus, but not with Acutiramus and Erettopterus. Pterygotus is often associated with osteostracans, whereas Jaekelopterus appears more frequently alongside osteichthyans, placoderms, and pteraspids. This faunal association, alongside a predation trace fossil on the headshield of Lechriaspis patula Elliott and Petriello, Reference Elliott and Petriello2011 (a pteraspid), suggests that some pterygotids were likely piscivorous, or at least opportunistically preyed upon armored fishes. This hypothesis is supported by biomechanical analyses of their chelicerae, which reveal the capacity to withstand substantial impact forces (Elliott and Petriello, Reference Elliott and Petriello2011; Bicknell et al., Reference Bicknell, Simone, Meijden, Wroe, Edgecombe and Paterson2022; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023). Furthermore, Pterygotus and Jaekelopterus exhibit more robust cheliceral morphologies than Acutiramus and Erettopterus, including thicker cheliceral fingers and more strongly developed denticles (Braddy, Reference Braddy2023). These traits likely represent adaptations for handling heavily armored prey. Their shared morphological traits, combined with similar visual acuity, imply that Pterygotus and Jaekelopterus might have employed comparable hunting strategies, reinforcing their classification as active predators (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Lamsdell, Poschmann, Anderson and Briggs2015).

The gigantism observed in pterygotids is commonly interpreted as part of an evolutionary arms race with early fish (Romer, Reference Romer1933; Briggs, Reference Briggs1985; Braddy et al., Reference Braddy, Poschmann and Tetlie2008; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023). According to Cope’s Rule, larger body sizes confer selective advantages in competition and predation avoidance, potentially facilitating population stability (Hone and Benton, Reference Hone and Benton2005; Braddy et al., Reference Braddy, Poschmann and Tetlie2008). However, some researchers have argued that pterygotid gigantism might instead reflect ecological opportunism, filling a niche in the absence of other large predatory swimmers rather than evolving directly in response to vertebrate competition (Lamsdell and Braddy, Reference Lamsdell and Braddy2010). For example, the large size seen in some Acutiramus specimens is not strongly correlated with the presence of armored Agnatha or jawed vertebrates in the associated fauna (Braddy et al., Reference Braddy, Poschmann and Tetlie2008; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023).

We estimated the size (using TBL as the proxy) of Pterygotus wanggaii individuals based on a framework of proportional inference constructed from more complete materials of other pterygotids. Specifically, two metrics were used as the numerator and denominator respectively, CMFL and TBL. Braddy et al. (Reference Braddy, Poschmann and Tetlie2008) estimated two possible TBL of Jaekelopterus rhenaniae based on a cheliceral material (PWL 2007/1-LS) they examined, and the known TBL/CMFL ratios of Acutiramus (233 cm) and Pterygotus (259 cm). Because we do not have the original metrics for these two genera, and Pterygotus wanggaii is a Pterygotus, the TBL/CMFL ratios were indirectly calculated from the CMFL (28.8 cm) and the TBL estimations (259 cm) of J. rhenaniae. Consequently, we derived two TBL estimations for Pterygotus wanggai by multiplying the CMFL of our examined materials (DS-cmf20230426a, GMG 20211001003, and IVPP-I4593) to the Pterygotus-based TBL/CMFL ratios. The result indicates that DS-cmf20230426a corresponds to an individual ~57.6 cm in total length measured from the anterior carapace margin to the tip of the telson. The type specimen, GMG 20211001003, yielded a similar estimate of ~60.1 cm, whereas IVPP-I4593 was estimated at 53.7 cm. However, due to the incompleteness of these specimens, size estimations based on cheliceral length alone can lack precision. Notably, only a few adult pterygotids have been recovered from mass-molt deposits, and no larger individuals have been reported from the same formation (Poschmann et al., Reference Poschmann, Tetlie and Haven2006). Given the comparable sizes of these specimens and the absence of larger examples, we consider them to represent adult individuals, which renders Pterygotus wanggaii a medium-sized pterygotid within this family.

Another pterygotid, Erettopterus qujingensis, could have reached lengths > 90 cm based on tergite and metastoma material, making it one of the largest known species within its genus and notably larger than Pterygotus wanggaii (see Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022). The coexistence of two large pterygotid species within the same formation is relatively rare in the fossil record. However, a well-documented example exists in the Williamsville beds of the Bertie Formation, where Acutiramus macrophthalmus Hall, Reference Hall1859 and Pterygotus cobbi Hall, Reference Hall1859 coexisted (Tollerton, Reference Tollerton1997). In that case, Acutiramus macrophthalmus appears to have attained a larger size than Pterygotus cobbi (see Clarke and Ruedemann, Reference Clarke and Ruedemann1912), suggesting niche differentiation to reduce competition—an ecological dynamic that might have also applied to E. qujingensis and Pterygotus wanggaii.

The coexistence of these two large pterygotids in the same deposits might have been facilitated by differences in prey preference, as suggested by variations in their cheliceral morphology. The Xiaxishancun and Xitun formations (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Lamsdell, Wang, Chen, Selden and He2025), which preserve Pterygotus wanggaii, also contain a diverse assemblage of Agnatha. This faunal association supports the interpretation of Pterygotus being piscivorous. In Pterygotus wanggaii, the MMDs are relatively blunt and rounded compared to the sharper denticles seen in some of its congeners, e.g., Pterygotus cobbi, and in other pterygotids like Erettopterus qujingensis. This blunt morphology is consistent across both fingers, as observed in multiple specimens (DS-cmf20230426a, DS-cff20230907a-b, IVPP-I4593, GMG 20211001003).

Well-armored Agnatha like polybranchiaspids have been recovered from the same formation. Notably, a fragmentary specimen of Polybranchiaspis sp. indet. was found in association with DS-cmf20230426a (Fig. 4.3), implying that these armored fishes could have been potential prey for Pterygotus wanggaii. Many of these osteostracans exceeded 10 cm in body length, making them nearly one-fifth the size of Pterygotus wanggaii. If a pterygotid failed to dispatch such large, heavily armored prey with a single strike, slender denticles might easily fracture during the ensuing struggle. The blunt MMDs of Pterygotus wanggaii could thus represent an adaptation for crushing rather than puncturing, enabling them to effectively deal with these robust Agnatha. However, it remains unclear whether the bluntness of these denticles reflects adaptive morphology or feeding wear in mature individuals. In contrast, Erettopterus qujingensis exhibits slenderer, sharper denticles and thinner cheliceral fingers (Figs. 7, 8), suggesting a preference for less-armored prey, thereby avoiding competition with Pterygotus wanggaii. Moreover, the larger chelicerae of E. qujingensis might have allowed it to function as a generalist predator, capable of subduing a broader range of prey types, including larger and more defensively equipped species (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Lamsdell, Poschmann, Anderson and Briggs2015; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023). Based on observations of body-size development in other eurypterids (Lamsdell and Selden, Reference Lamsdell and Selden2013) and modern scorpions, it is hypothesized that pterygotids likely ceased molting upon reaching adulthood. As a result, they would have been unable to repair damage to their cheliceral denticles through molting, potentially retaining worn or damaged structures throughout their adult life. Over time, this accumulated wear could have impaired their ability to effectively capture prey, ultimately leading to starvation.

As a Gondwanan pterygotid, the ancestor of Pterygotus wanggaii might have migrated from Laurasia, although the timing of this dispersal remains uncertain. Pterygotus wanggaii is among the few pterygotids discovered in Asia and is one of only three recorded from China (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022, Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023; He et al., Reference He, Wang, Dai, Lu and Yang2024). The earliest known pterygotid from China is an unidentified Erettopterus species from the Majiaochong Formation, dating to the Llandovery Epoch, making it one of the oldest pterygotid fossils globally (Tetlie, Reference Tetlie2007; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023; He et al., Reference He, Wang, Dai, Lu and Yang2024). By contrast, E. qujingensis is a much later and significantly larger species that coexisted with Pterygotus wanggaii, and based on its cheliceral denticle morphology, it might be more closely related to Euro-American species, e.g., Erettopterus osiliensis (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1883) (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Selden, Lamsdell, Zhang, Chen and Zhang2022). This suggests that pterygotids might have crossed the Paleo-Tethys Ocean multiple times during the Silurian among different evolutionary lineages (He et al., Reference He, Wang, Dai, Lu and Yang2024). Furthermore, Poschmann et al. (Reference Poschmann, Tetlie and Haven2006) proposed that medium-sized Acutiramus spp. inhabited marine environments and returned to freshwater or nearshore breeding sites only as adults—possibly explaining the abundance of smaller juveniles and the relative scarcity of adults. A similar pattern might apply to other pterygotids, given comparable records of mass-molt assemblages (Vrazo and Braddy, Reference Vrazo and Braddy2011). Thus, the multiple adult and juvenile chelicerae, alongside numerous fragmentary tergites recovered from the Xiaxishancun Formation, could represent a breeding or mass-molting site for E. qujingensis and Pterygotus wanggaii. However, because the Xiaxishancun Formation is a continental deposit representing a swamp or deltaic environment, it is also possible that these remains were transported from nearby aquatic habitats (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Giles, Friedman and Zhu2017).

Lastly, although some pterygotids have been discovered in freshwater deposits, conspecific material has also been reported from marine settings. Several specimens attributed to Pterygotus have been recovered from marginal marine deposits in North America dating to the Eifelian Epoch (Plotnick, Reference Plotnick2022). Similarly, a coxa assigned to Jaekelopterus rhenaniae (PWL 2015/21-LS) was found in the marine Hunsrück Shale of Germany (Poschmann et al., Reference Poschmann, Bergmann and Kühl2017). However, this particular specimen shows evidence of decay and might have been transported postmortem rather than representing an individual that lived and died in situ (Poschmann et al., Reference Poschmann, Bergmann and Kühl2017). Despite such uncertainties, the occurrence of pterygotid fossils in both freshwater and marine deposits suggests ecological plasticity. This ability to tolerate a range of salinities likely facilitated their dispersal across marine barriers and contributed to their widespread, global distribution.

Reconstruction of pterygotids

The reconstruction of pterygotid chelicerae has long been debated. Earlier reconstructions often depicted the chelicerae with four or more segments, a misinterpretation now understood to result from taphonomic fractures during fossilization (Laub et al., Reference Laub, Tollerton and Berkof2010; Schmidt and Melzer, Reference Schmidt and Melzer2024). More recent studies, particularly on Acutiramus, suggest that pterygotid chelicerae were positioned in an ‘euthygnathous’ orientation: extending forward from the body with the manus folded beneath—based on three-dimensional (3D) modeling and comparisons with modern Opiliones, which also possess elongated chelicerae (Schmidt and Melzer, Reference Schmidt and Melzer2024). This configuration likely restricted the vertical movement of the chelicerae, because their coxae were situated beneath the prosomal carapace (Bicknell et al., Reference Bicknell, Kenny and Plotnick2023; Schmidt and Melzer, Reference Schmidt and Melzer2024). Additionally, the articulation between the cheliceral coxae and the carapace in Acutiramus appears relatively fragile and prone to damage, especially when engaging with large or vigorous prey (Bicknell et al., Reference Bicknell, Kenny and Plotnick2023).

Acutiramus is frequently found in association with less heavily armored arthropods, e.g., phyllocarids, and possesses a comparatively high chelicera-to-body size ratio. This suggests a predatory strategy focused on delivering swift strikes for disabling prey, which would then be processed using the coxal gnathobases (Bicknell et al., Reference Bicknell, Kenny and Plotnick2023; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023). Consequently, it is plausible that some pterygotids evolved elongated but structurally delicate cheliceral coxae to enable greater striking distance—potentially facilitating ambush-style attacks. This strategy could have limited their prey size to organisms no larger than the spread of their open cheliceral fingers. Pterygotids might have held their chelicerae tucked beneath the body while swimming near the substratum, only extending them forward during brief bursts of activity (e.g., a strike), because frequent repositioning or holding the chelicera in a forward posture could have led to fatigue or damage. In one hypothetical hunting strategy, pterygotids would visually detect prey, swim slowly above them, and then rapidly snap their chelicerae downward. Alternatively, they might have relied more heavily on tactile cues, holding their chelicerae beneath the body and striking reflexively when prey came within range (Fig. 11.2). This latter method could explain why species like Acutiramus exhibit lower visual acuity compared to genera like Pterygotus and Jaekelopterus, yet are still considered active predators (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Lamsdell, Poschmann, Anderson and Briggs2015; Bicknell et al., Reference Bicknell, Simone, Meijden, Wroe, Edgecombe and Paterson2022; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023). Furthermore, the slender cheliceral fingers and elongated, serrated denticles of Acutiramus likely allowed for inducing large, deep wounds that incapacitated prey after a successful strike, minimizing the need for extended handling. Combining morphologies like relatively fragile joints and relatively low visual acuity, Acutiramus might not need to deal with struggling prey as frequently. Whether genera like Pterygotus and Jaekelopterus employed a similar strategy remains unclear. However, their higher visual acuity, more robust chelicerae, and associations with heavily armored prey, e.g., armored fishes, suggest they might have relied more on active pursuit and precise visual targeting (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Lamsdell, Poschmann, Anderson and Briggs2015; Braddy, Reference Braddy2023).

Figure 11. Reconstruction of Pterygotus wanggaii Ma et al., Reference Ma, Zhang, Lamsdell, Chen, Selden and Chen2023 and speculated hunting behavior of Acutiramus. (1) Reconstruction of Pterygotus wanggaii. Missing parts based on the reconstruction of other pterygotids by Junyi Chin and described materials from known species. (2) Speculated hunting behavior of Acutiramus. Species habitus was based on the 3D reconstruction of Acutiramus by Bicknell et al. (Reference Bicknell, Kenny and Plotnick2023) and modern chelicerata.

Conclusion

The specimens assigned to Erettopterus qujingensis and Pterygotus wanggaii reported in this study have provided additional diagnostic features that clarify their morphology and stratigraphic distribution. Materials from the Xiaxishancun Formation attributed to E. qujingensis extend the temporal range of this species from the Přídolí Epoch of the Late Silurian into the Lochkovian Epoch of the Early Devonian. This extension suggests that climatic shifts across the Silurian–Devonian boundary might have had a limited impact—if any—on the extinction of some pterygotid taxa. Moreover, the discovery of a probable breeding and mass-molting site shared by both E. qujingensis and Pterygotus wanggaii implies that these species were likely permanent residents of the region. This, in turn, supports the hypothesis that pterygotids migrated into Gondwana multiple times during the Silurian–Devonian interval, with distinct lineages establishing themselves independently.

The position-based cheliceral nomenclature employed in this study offers a more systematic and less ambiguous alternative to earlier dentition classifications, which often relied upon subjective, inconsistent definitions. However, the effectiveness of this methodology depends on the preservation of complete denticle rows, making it unsuitable for fragmentary or incomplete specimens. Taphonomic processes can result in the loss or deformation of denticles, introducing uncertainty into the identification and measurement of denticles like the determination of MMD. For future taxonomic work employing this system, it is recommended to use either complete chelicerae or isolated fingers with fully preserved denticle rows. Nevertheless, a broader comparative dataset is essential to account for potential intraspecific variation in cheliceral morphology.

Our proposed hunting strategy might help explain the evolution of the highly elongated cheliceral coxae and the relatively slow swimming capacity of pterygotids. Rather than pursuing prey in active chases, these eurypterids likely relied on stealth and ambush tactics, striking from above with their extended chelicerae. This behavioral model aligns with their morphology and helps contextualize their predatory adaptations. However, despite various hypotheses, there is no conclusive evidence that gigantism in eurypterids was driven by external factors, e.g., temperature, oxygen availability, environmental setting, or faunal diversity (Ruebenstahl et al., Reference Ruebenstahl, Koch, Lamsdell and Briggs2024). Instead, we propose that the evolution of large body size in eurypterids might have been linked to ecological opportunity or competitive dynamics—possibly including an evolutionary arms race with early vertebrates. Ultimately, any behavioral reconstruction for extinct taxa like pterygotids remains speculative. Their unique morphology has no clear modern analog among extant aquatic arthropods, underscoring the evolutionary novelty of these ancient predators.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Bicknell for his support regarding the measurement of the specimens and discussing the possible behavior of pterygotids, and J. Chin for guiding the reconstruction and providing the reconstruction of the chelicera in Figure 2. We express our gratitude to J.A. Dunlop, M. Poschmann, J. Lamsdell and an anonymous referee for the review of this paper. This work was supported by the China Geological Survey (DD20230208404) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 42172129).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.