Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is one of the most common causes of hospitalization and mortality in the United States. Reference Xu, Murphy, Kochanek and Bastian1 There have been racial disparities observed in CAP pertaining to incidence, severity, treatment, and outcomes which pose a public health concern. Reference Lippert, Buscemi, Saiyed, Silva and Benjamins2,Reference Burton, Flannery and Bennett3 Limited, conflicting data exist regarding racial disparities in antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance. Reference Fortin-Leung and Wiley4–Reference Charani, Mendelson and Ashiru-Oredope7 A few studies have suggested that Black, Hispanic, and lower-income people are at increased risk of community-acquired drug-resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from a typically sterile body site (e.g., blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and internal body fluid) and drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae CAP. Reference See, Wesson and Gualandi8,Reference Restrepo, Velez, Serna, Anzueto and Mortensen9 However, socioeconomic factors explained these observed differences—there was no racial predisposition to harboring resistant pathogens after adjusting for confounders. Reference See, Wesson and Gualandi8,Reference Restrepo, Velez, Serna, Anzueto and Mortensen9 Given the paucity of literature evaluating whether racial disparities exist in treatment selection for patients hospitalized with CAP—particularly as most existing data on antimicrobial stewardship disparities focus on the outpatient setting—additional studies are needed. Reference Kim, Kabbani and Dube10 The aim of this study was to describe racial differences in antibiotic prescribing for patients hospitalized with CAP.

Methods

Sample

We conducted a retrospective cohort study across 11 Cleveland Clinic community hospitals. We included patients ≥18 years of age who were admitted with a diagnosis of CAP from November 1, 2022, to January 31, 2025. CAP cases were identified using ICD-10 diagnostic codes, and we also included patients for whom clinicians documented CAP in free-text diagnosis fields. Although a patient may have been admitted multiple times during the study period, we considered each admission as an independent observation. Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of cystic fibrosis, were discharged from an acute care hospital within the last 7 days, had hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) indicated in their problem list, were admitted to the intensive care unit within 24 hours, had comfort care measures, had any bacterial pathogen isolated in blood or respiratory cultures 72 hours prior to admission, transferred from another hospital, or had an unknown race or ethnicity. This study was approved by Cleveland Clinic’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The primary predictor variable was patient race, which was self-reported. Comparisons were limited to non-Hispanic Black (NHB) and non-Hispanic White (NHW) patients due to small sample sizes and heterogeneity among patients from other racial and ethnic groups, which precluded statistically reliable subgroup analyses. Therefore, these other groups were excluded from the analysis. Race was conceptualized and used as a social, rather than biological, variable to reflect the influence of structural and interpersonal factors on healthcare delivery. Reference Peek11

The primary outcome was extended-spectrum antibiotic (ESA) guideline-concordant CAP therapy. This encompassed both patients for whom ESA therapy was recommended and who received it, as well as those for whom ESA therapy was not indicated and who appropriately did not receive it. ESA guideline concordance was based on the 2019 IDSA/ATS guidelines Reference Metlay, Waterer and Long12 whereas clinical severity was defined by the 2007 IDSA/ATS CAP severity criteria guidelines. Reference Mandell, Wunderink and Anzueto13 Treatment of non-severe pneumonia was considered guideline-concordant if it included a beta-lactam plus a macrolide or respiratory fluoroquinolone with the addition of or escalation to MRSA or Pseudomonas aeruginosa coverage only in the event of prior respiratory isolation of these organisms in the past year or in response to a positive blood culture. Conversely, treatment of severe pneumonia was considered guideline-concordant if it included a beta-lactam plus a macrolide or a beta-lactam plus a respiratory fluoroquinolone with the addition of MRSA and/or Pseudomonas coverage in the setting of prior respiratory culture isolation within the past year or recent hospitalization with IV antibiotics in the past 90 days. We defined non-extended spectrum antibiotics (non-ESA) as ampicillin/sulbactam, amoxicillin/clavulanate, ceftriaxone, cefdinir, cefuroxime, cefpodoxime, azithromycin, doxycycline, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin. All other antibiotics targeting CAP treatment were defined as ESA.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were collected for all patients. Clinical variables, including indicators of clinical stability, disease severity, CURB-65 scores, and ventilatory support were assessed within the first 24 hours of hospital admission and were derived from the minimum and maximum recorded values during that period.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation (SD); non-normally distributed variables as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. Parametric and non-parametric methods were used to compare demographic and clinical differences by race. Rates of concordant ESA therapy were compared across racial groups and hospitals. The association between racial group and guideline concordance was assessed using two multivariable logistic regression models adjusting for age, gender, ADI, and comorbidities (diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, renal failure, dialysis, liver disease, immunocompromising condition, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder), clinical instability on day 1, and American Thoracic Society (ATS) severity. Variables were selected based on bivariate associations, literature, and clinical judgment regarding anticipated impact on guideline concordance. The first model did not adjust for hospital; the second did. Because < 1% of our sample was missing any data (ATS severity), we conducted a complete case analysis rather than using other adjustment techniques. Tests were two-sided with a significance level of 0.05. Analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.0.

Results

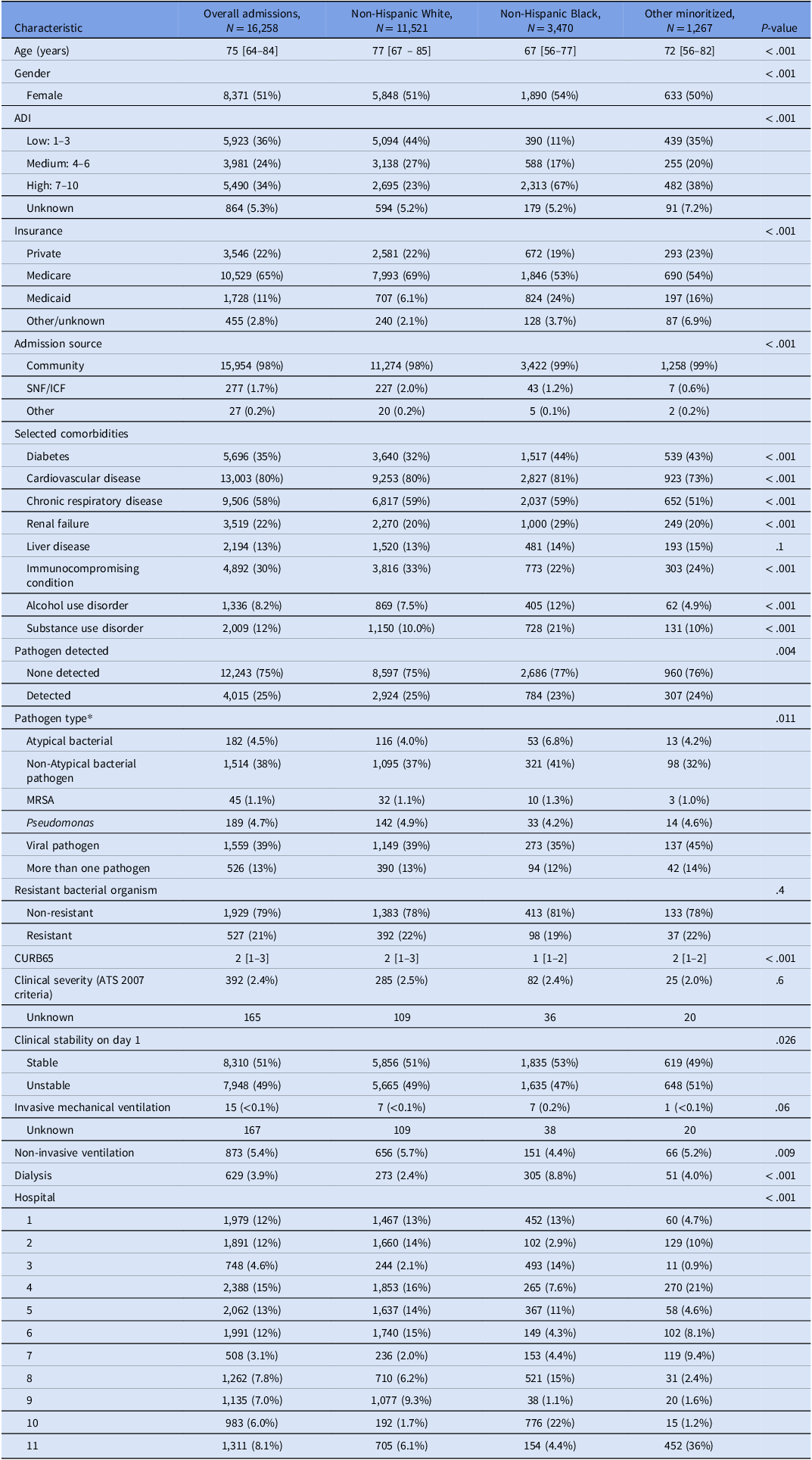

From November 1, 2022, to January 31, 2025, there were 14,991 eligible patient admissions included in the sample. There were 13,091 unique patients, with 89% of patients having one eligible encounter. Table 1 describes the sample population by race. Compared to NHW, NHB were more likely to be younger, female, live in a higher area of deprivation, and have Medicaid insurance. They were also more likely to have diabetes, renal failure, alcohol and substance use disorder, and be clinically stable on day 1, but less likely to have an immunocompromising condition. No significant differences were observed amongst groups regarding resistant organism isolation.

Table 1. Demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics of admissions for community-acquired pneumonia, stratified by race

Note. IQR, Interquartile Range; ADI, Area Deprivation Index; SNF, Skilled Nursing Facility; ICF, Intermediate Care Facility; ATS, American Thoracic Society; CAP, Community-Acquired Pneumonia; ESA, Extended Spectrum Antibiotic; MRSA, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

*Categories are mutually exclusive. Data presented as n (%) for categorical variables and median [IQR] for continuous variables, unless otherwise specified.

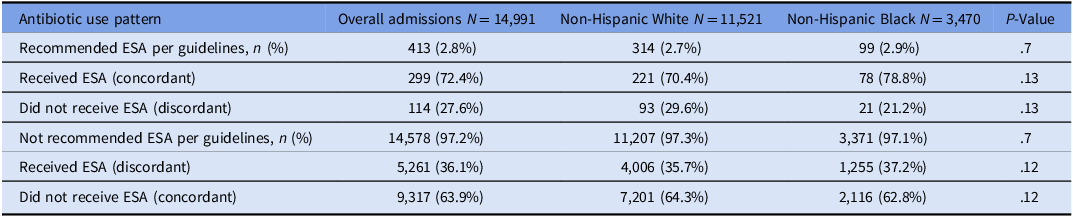

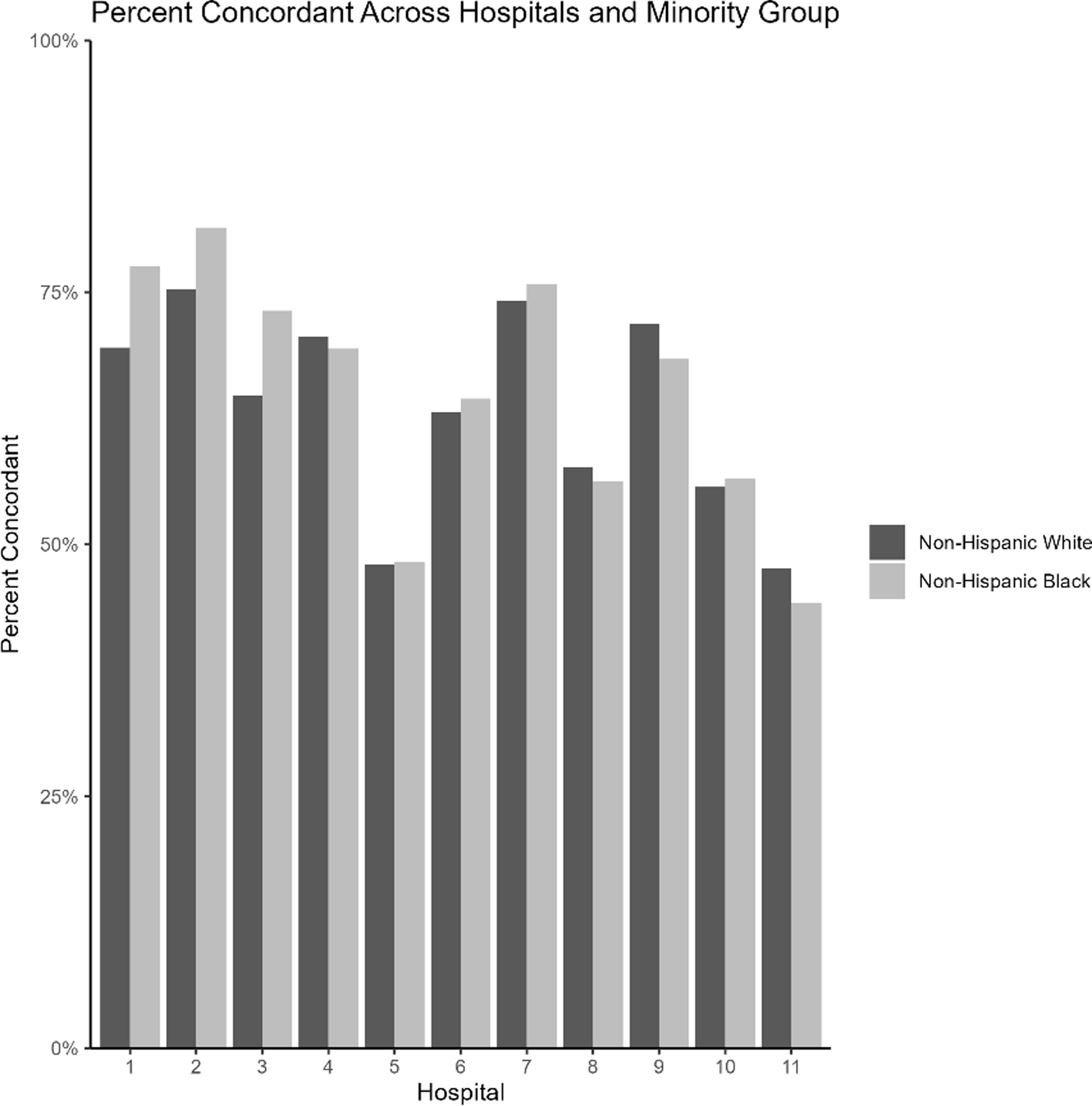

The percentage of NHW patients varied across the 11 hospitals from 19.8% to 96.6% (Supplemental Table 1). Overall, 413 (2.8%) of patients met the current guidelines for ESA (Table 2). Among those recommended to receive ESA per guidelines, 72.4% received an ESA within 24 hours. Of those not recommended to receive ESA per guidelines, 36.1% received an ESA within 24 hours. The primary outcome, guideline concordance of ESA, was moderate to moderately high. Specifically, concordance was 64.4% in NHW patients and 63.2% in NHB patients (P = .2), while hospital-level concordance ranged widely from 44% to 82% (Figure 1). NHB patients were more likely than NHW patients to receive ESA without a documented indication (37.2% vs 35.7%; P = .121), indicating potential overuse. Furthermore, ESA prescribing with an appropriate indication was more common among NHB patients compared to NHW patients, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (78.8% vs 70.4%; P = .133) (Table 2).

Table 2. Patterns of extended-spectrum antibiotic (ESA) use by race among hospital admissions for community-acquired pneumonia

Note. ESA, Extended Spectrum Antibiotic. Data presented as n (%) for categorical variables.

Figure 1. Percent of concordant cap therapy across hospitals and racial group.

Multivariable logistic regression was performed to evaluate the association between race and ESA guideline-concordant CAP therapy, with and without adjustment for hospital. Adjusting for patient-level characteristics had no impact on the odds of receiving ESA guideline-concordant therapy (adjusted OR, 0.91; 95% CI [0.83, 1.00]). After adjusting for hospital, NHB patients were more likely to receive ESA therapy concordant with CAP guidelines (adjusted OR, 1.17; 95% CI [1.06, 1.3]). Hospital-specific guideline concordance is presented in Supplemental Figure 1, with adjusted odds ratios ranging from 0.85 to 1.63 with wide confidence intervals.

Discussion

This study assessed the association between race and ESA prescribing in hospitalized patients with CAP and found that NHB patients were more likely to receive ESA therapy consistent with CAP guidelines after accounting for hospital-level variation, despite no difference observed after adjusting for patient-level characteristics. We found no difference in the probability of a resistant organism isolated during the current hospital admission or severity of illness—two factors that might be expected to increase the use of ESA—based on race. These findings indicate that differences in CAP treatment are largely attributable to variation in where minoritized and non-minoritized patients receive care.

A hospital’s access to resources and its system-level process of care can be an important driver of disparities. Hausmann and colleagues sought to examine within and between-hospital racial/ethnic disparities in quality indicators and mortality for hospitalized patients with pneumonia and found that Black and Hispanic patients were significantly more likely to be treated at urban and large/teaching hospitals and hospitals with diverse patient populations than White patients. Reference Hausmann, Ibrahim and Mehrotra14 Moreover, they demonstrated that patients receiving care at hospitals serving higher concentrations of Black and Hispanic patients had lower odds of receiving 7 of 8 recommended process quality indicators which included appropriate antibiotic selection within 24 hours of admission. Reference Hausmann, Ibrahim and Mehrotra14 Similarly, Jha and colleagues identified that hospitals with either a higher volume or proportion of Black patients were most often large, urban teaching hospitals and provided lower quality of care for pneumonia than hospitals with a low volume of Black patients. Reference Jha, Orav, Li and Epstein15

Historic racialized housing and zoning policies, including redlining, have shaped residential patterns and constrained healthcare access for minoritized populations, often channeling care toward hospitals serving their immediate communities. Reference Lin, Hammond, Esposito, Majewski, Foraker and Joynt Maddox16 They may also not be aware of differences in care quality, especially if they are not easily identified. Efforts to reduce these disparities should therefore target overall performance at hospitals with large minority patient populations.

We found that in slightly more than half of hospitals within our system, NHB patients were more likely than NHW patients to receive guideline-concordant antibiotics; however, these hospitals served primarily NHW patients suggesting that hospital-level factors may be more influential than prescriber bias. The current evidence is mixed related to within-hospital variation of the impact on race on CAP-guideline-concordant care. Two studies found within-hospital racial disparities in CAP management which included measures such as receipt of pneumococcal and influenza vaccinations, smoking cessation counseling, initial antibiotic timing, and oxygenation assessment. Reference Hausmann, Ibrahim and Mehrotra14,Reference Jha, Orav, Li and Epstein15 Another study found no racial differences in the receipt of CAP-guideline-concordant antibiotics between Black and White patients aged ≥65 years, regardless of admission to a medical ward or intensive care unit within the Veterans Health Administration. Reference Frei, Mortensen and Copeland17 Similar to our findings, Hasnain-Wynia and colleagues found that almost half of the racial/ethnic disparities for oxygenation assessment for CAP and antibiotic therapy within 8 hours of arrival for CAP reflected between-hospital rather than within-hospital factors. Reference Hasnain-Wynia, Baker and Nerenz18 Taken together, these findings suggest that quality improvement initiatives including antimicrobial stewardship efforts should target hospitals with higher concentrations of minority patients, and further research should seek to understand the association between where minoritized patients seek care and the quality of care that they receive.

A key strength of this study is its focus on inpatient management of CAP, an area where literature on racial and ethnic disparities remains limited compared to outpatient care. This investigation reflects real-world conditions, where antibiotic prescribing decisions were made independently by clinicians without protocolized intervention. The study included a diverse mix of hospital settings (e.g., urban teaching hospitals and smaller community hospitals) and clinician types (e.g., hospital-employed vs private-practice providers) within a single health system, enhancing generalizability.

There are several limitations. First, our analysis compared only NHB and NHW patients; we were unable to evaluate other racial or ethnic minority groups due to small sample sizes and heterogeneity. Second, we lacked data on factors influencing hospital choice, limiting assessment of potential selection biases. Third, CAP cases were identified using ICD-10 codes and provider-entered free-text diagnoses, which may introduce misclassification. Finally, we were unable to directly measure prescriber bias or reasons for hospital-level variation in prescribing. The lack of racial differences in prescribing within hospitals suggests that such bias, if present, may not be a major driver. Nonetheless, residual confounding by unmeasured factors cannot be excluded, underscoring the need for further research.

Conclusion

Overall, among patients hospitalized with CAP, NHB patients were more likely than NHW patients to receive ESA guideline-concordant care. This difference appears to be driven by hospital-level factors rather than individual patient characteristics. Future research should explore the underlying reasons for interhospital variation in prescribing practices to support more equitable and effective antibiotic stewardship.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2025.10371.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1R01HS028633). None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.