John Pierpont Morgan never had the security of working alongside a central bank in the US. Distrust of banks, especially central banks, was widespread in the US, and such suspicion ultimately contributed to the glaring absence of a lender of last resort in the payments system. Yet, described as having a massive, smoldering physical presence with the driving power of a locomotive,Footnote 1 he became the leading financier in the country, coordinating domestic private funds and funds from investors and central banks overseas to fight the recurring financial crises of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. His actions garnered him the role of lender of last resort in the US, even though no such formal institution existed. The purpose of our book is to chronicle and analyze Morgan’s interventions in financial crises, telling the story of how he learned the art of last resort lending by trial and error, and finding its relevance to issues that last resort lenders still face in the early twenty-first century. Figure 1.1 illustrates one contemporary view of Morgan’s dominating role as a central banker.

Figure 1.1 “Why should Uncle Sam establish one, when Uncle Pierpont is already on the job?” Illustration on the cover of Puck, vol. 67, no. 1718 (February 2, 1910).

Figure 1.1Long description

This illustration from Puck magazine is titled “the Central Banker.” It depicts a well-dressed man, J.P. Morgan, wearing a suit and a hat. He is surrounded by tall buildings, symbolizing wealth, and the bank buildings of New York, while his right hand reaches toward a child’s piggy bank, emphasizing his influence in business and industry. The caption reads Why should Uncle Sam establish one (a central bank) when Uncle Pierpont is already on the job?

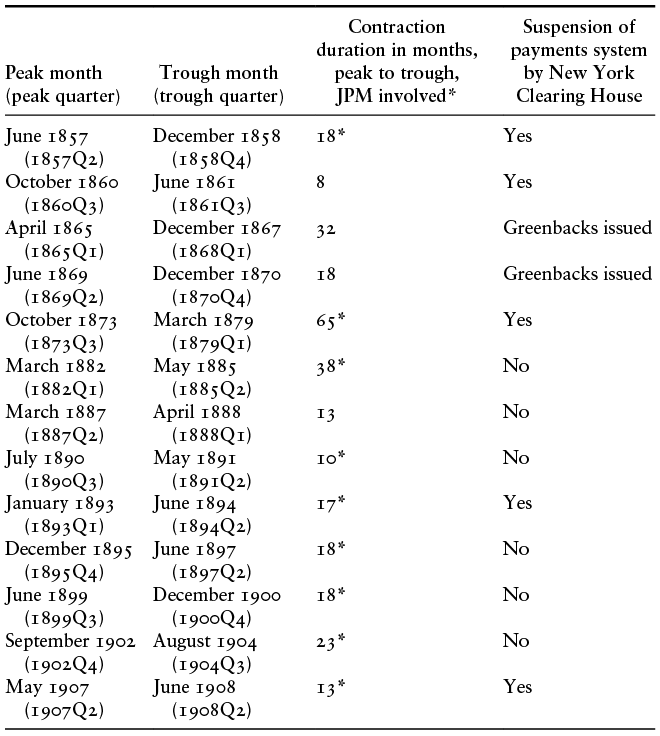

Our book is part of the Cambridge University Press Studies in Macroeconomic History series. In Table 1.1 we identify which US recessions were associated with disruptions to the payments system. We also identify the instances in which Morgan created a last resort loan.Footnote 2 The table shows the length of time between peak economic activity and troughs for each recession. Not all recessions were associated with banking crises; the payments system was disrupted to varying degrees indicated in the right column. Morgan created last resort loans in nine of the thirteen business contractions.

| Peak month (peak quarter) | Trough month (trough quarter) | Contraction duration in months, peak to trough, JPM involved* | Suspension of payments system by New York Clearing House |

|---|---|---|---|

| June 1857 (1857Q2) | December 1858 (1858Q4) | 18* | Yes |

| October 1860 (1860Q3) | June 1861 (1861Q3) | 8 | Yes |

| April 1865 (1865Q1) | December 1867 (1868Q1) | 32 | Greenbacks issued |

| June 1869 (1869Q2) | December 1870 (1870Q4) | 18 | Greenbacks issued |

| October 1873 (1873Q3) | March 1879 (1879Q1) | 65* | Yes |

| March 1882 (1882Q1) | May 1885 (1885Q2) | 38* | No |

| March 1887 (1887Q2) | April 1888 (1888Q1) | 13 | No |

| July 1890 (1890Q3) | May 1891 (1891Q2) | 10* | No |

| January 1893 (1893Q1) | June 1894 (1894Q2) | 17* | Yes |

| December 1895 (1895Q4) | June 1897 (1897Q2) | 18* | No |

| June 1899 (1899Q3) | December 1900 (1900Q4) | 18* | No |

| September 1902 (1902Q4) | August 1904 (1904Q3) | 23* | No |

| May 1907 (1907Q2) | June 1908 (1908Q2) | 13* | Yes |

To show how J. P. Morgan, a private citizen, became the de facto lender of last resort, we show first how he took on the role. He was able to adapt his successful use of the investment syndicate from his routine business transactions to his nonroutine, crisis last resort loan transactions. To do that, we show how he was able to motivate and incentivize private investors to participate in these crisis fundings by arranging the risk and reward incentives to appeal to private investors, remembering that he had no central bank backstopping these deals. As in his routine syndicates, he recruited subject matter experts (SMEs) along with investors who could provide the large financial capacity to make the deals work. Such experts, while lacking capacity on occasion, had specialized knowledge of the markets Morgan was trying to protect, keeping the syndicate on track. His deep network of contacts in industry and finance outside of the New York society circle were key to his success as the lender of last resort.

Then we show why he accepted this role. We provide evidence that he was certainly guided by the profit motive like any of the financiers and entrepreneurs of the Gilded Age, as were the central banks of England and France, but which had different stakeholders from Morgan. But he was also motivated by providing long run stability to financial and industrial markets, believing that this was a both the responsibility of any reputable businessman of high privilege and that this was the best environment for his own firm to produce profits. This longer run perspective was amplified by his long relationship with his father Junius, passing it on to his son Jack and beyond. In this way his actions were much like the intergenerational, dynastic investing of the House of Rothschild and the long horizons taken by the central banks of England and France.

To understand Morgan’s journey to being the lender of last resort, we should be aware that the path he followed, ultimately leading to the Federal Reserve Act, was laid down in the complicated and unpredictable financial setting of the US, a path that did not resemble anything found in Europe. He operated within a banking and payments system structured around unit banking (banking with little branching, albeit connected to other banks by a dense correspondent network) having no clear structure like the Bank of England to expedite payments across longer distances. He also grew up in an America that suffered far more periodic panics and financial crises compared to the major European countries. The most notable panics that Morgan would have dealt with directly during the national banking era (1863–1914) were in 1873, 1884, 1890, 1893, and 1907; Europe, in contrast, did not suffer from such recurring panics after 1866. Morgan learned from each panic, becoming increasingly adept at using his private sector skills to contain them, experiencing both failures and successes along the way. Morgan and his contemporaries may have been aware of the earlier efforts of Alexander Hamilton and of the First and Second Banks of the United States to stabilize the financial system between 1791 and 1836. But we have not uncovered any direct mentions in Morgan’s correspondence to those earlier American episodes, so we cannot assume that they informed his lender of last resort activities. We limit our analysis to only those events that he, his father, or George Peabody, his father’s partner, specifically referred to in their letters as evidence of Morgan’s learning how to create lender of last resort functions in a private sector setting. (See Sylla, Wright, and Cowen (Reference Sylla, Wright and Cowen2009) for Alexander Hamilton’s last resort loan during the early Panic of 1791–92.)

The country had experimented with creating a central bank early on, but the experiment had not gone well, ending with the demise of the Second Bank of the United States in 1836. Policy makers subsequently chose a different path, one that resulted in three disparate pools of bank reserves. The US Treasury’s reserves could at times be used like those of a lender of last resort, but there were limitations. The private sector had fragmented reserves that were held by individuals, unit banks, and the clearinghouses formed by banks, most notably the one in New York. Finally, there were reserves held by European investors like the Rothschilds and central banks like the Bank of England and the Banque de France, reserves earmarked for non-US priorities. These three stockpiles of money available to solve a financial crisis had, by design, no formal channel through which they could be coordinated as last resort resources. At the same time, the country valued the public good of financial stability, which we define as the protection of the means of payment or the settlements system.Footnote 3 Without an official social contract to commit the country’s financial reserves in times of commercial peril, it fell to the private market to devise cooperation or commitment technologies to accomplish the task. Morgan eventually rose to meet that challenge.

We trace how Morgan learned to navigate the three pools of liquidity. Starting in 1853 at age sixteen, he learned international banking from his father, Junius, George Peabody in London. From them he learned merchant banking and then later, developed the practice of syndication for routine lending that brought bankers together to temporarily pool resources to make loans for capital and financial investments. He further developed his own negotiating techniques, especially the use of credible ultimatums to convince reluctant bankers to take collective action, pricing in profits large enough to make risk-bearing attractive.

Morgan’s techniques of channeling the private reserves to the distressed banks involved a standard concern: risk and reward had to balance. In order to access funds, borrowers had to find ways to convince lenders that their commitment to pay back was credible. Without the credibility of a central bank, Americans had to provide collateral that was trusted to back last resort loans. They often pledged ‘IOUs’ payable to US grain or cotton exporters (known as bills of exchange) or railroad bonds known to Europeans. Railroad bonds became an increasingly important form of collateral in the nineteenth century as the US railroad network expanded dramatically.

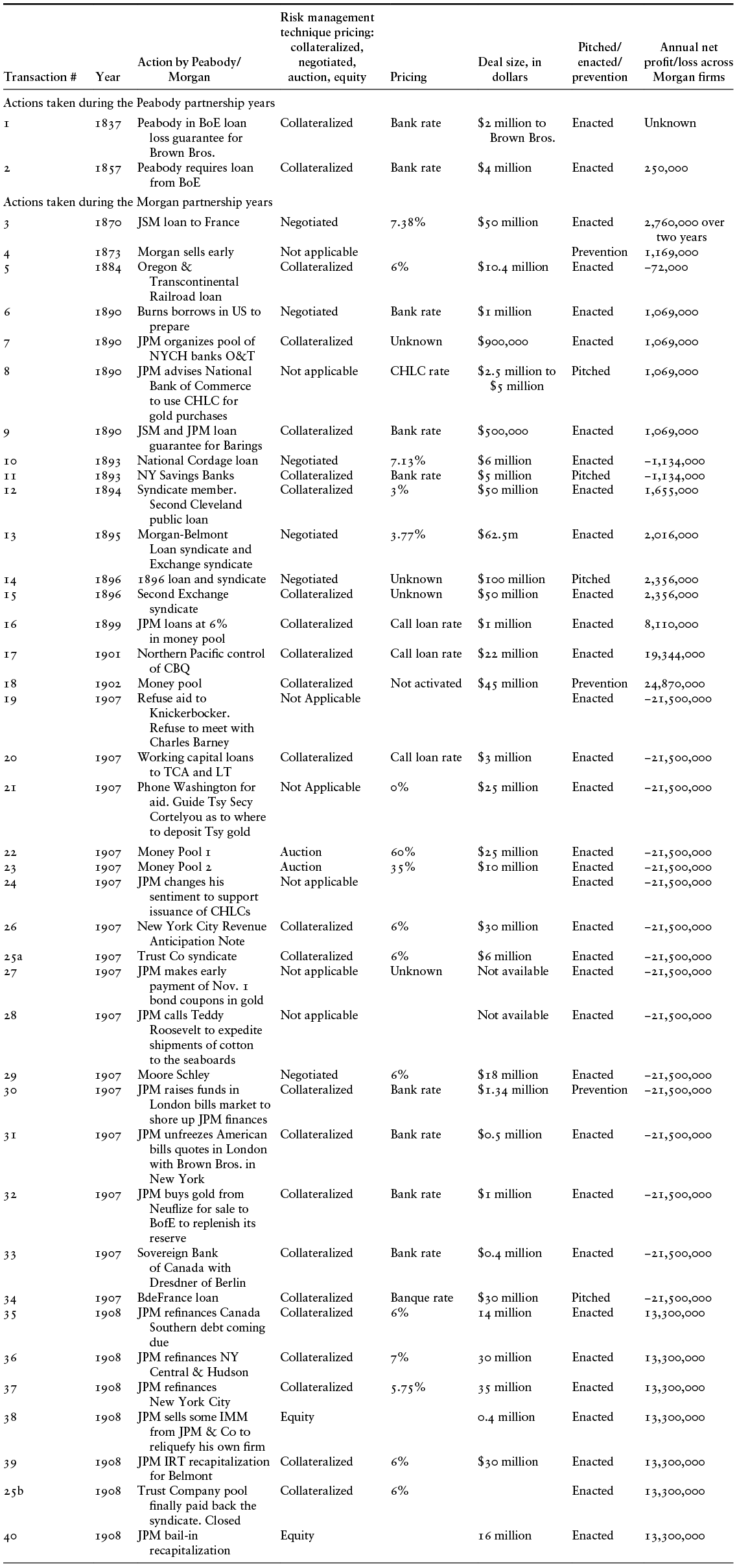

We classify Morgan’s last resort loans into three types. First, the many times in which he was able to coordinate reliable collateral, loans were priced at the prevailing risk-free rate. The fewer times when he was unable to secure adequate collateral, he negotiated financing at higher rates reflecting the presence of some risk, as in 1895 and 1896. Finally, the rare times when he either had no time to secure adequate collateral or when collateral was plunging in value, he arranged auctions of excess bankers’ reserves at exorbitant rates on the floor of the New York stock exchange, as during the Panic of 1907. In short, we find the more risk and uncertainty remaining in his transactions, the higher the price that was charged for emergency liquidity. His use of the profit mechanism as the device to coordinate last resort loans meant his facilities would not produce the outcome that we are acquainted with today when the Federal Reserve provides almost unlimited quantities of emergency funding at low interest rates.

We know of at least a dozen biographies of Morgan and books about his firm. Indeed, one has appeared almost every decade since he died. Burk, Chernow, Landes, and Hoyt cover the entire scope of the House of Morgan. Carosso’s exhaustive work examines Morgan’s investment projects in detail up to 1913, using the Syndicate Books as source evidence, providing more statistical detail than other works, while Horn’s recent work uses partners’ memos, covering the firm in the interwar period, after Morgan died. Pak analyzes the striated and hierarchical social milieu that formed the underpinning for Morgan’s activities. Hovey, Corey, Winkler, Satterlee, Allen, and most recently Strouse focus directly on Morgan’s life, with Satterlee’s biography being the only one that could be considered as authorized by Morgan himself. Our focus is different from all those works in that we do not look at his personal life resulting in another biography, nor do we recount details of his hundreds of private financial arrangements. Rather we limit our investigation to how he developed and adapted his syndicate structure to provide lender of last resort services in the US before the Federal Reserve System.

We rely on three primary archival data sources to support our different perspective: Morgan’s Syndicate Books, his General Ledgers, and his personal correspondence such as telegrams and letters to partners and customers. Information in his Syndicate Books explains how he organized financial deals and how he expanded these private dealings to take on systemic financial crises. The Syndicate Books are not accounting ledgers; they do not record debits or credits or systematic profits and losses. Instead, they record the types of transactions, the quantity of funds pledged, often the prices at which deals were floated, and the names of the syndicate participants, allowing us to identify investors Morgan viewed as subject matter experts or capacity investors. We can also get some idea of which investors Morgan chose to have repeated dealings with. While other financiers used the syndicate structure, we are not aware of other syndicate records that contain the detail of Morgan’s books, so unfortunately, we cannot draw meaningful comparisons with his peer bankers. Finally, by quoting from his correspondence to partners and testimony in various investigations, we bring Morgan’s own voice to our story. It is our hope that reading about crises from one person’s viewpoint makes crises writ large more readily understood by our readers.

We develop several appendices in which more technical analysis of Morgan’s actions fit into finance and economic theory, most likely of interest to policy makers, academics, and students of last resort lending, but not essential for readers who seek to generally understand the essential story of Morgan’s learning process as he designed last resort loans. The appendices include stylized balance sheet T-accounts to demonstrate how the New York Clearing House expanded loans during crises, regressions that estimate Morgan’s routine of including subject matter experts in his noncrisis securities underwritings, and stylized supply and demand analysis of the market for emergency liquidity in Morgan’s time, with suggestions for why Morgan’s upward sloping supply curve is very different from today’s supply of emergency funds of near limitless quantities at low interest rates supplied by the Federal Reserve. (See Technical Appendix 1.1 for the supply and demand graph.)

To aid the reader in seeing our story at a glance, we provide Table 1.2 listing the forty different actions Morgan took during financial crises. We analyze how the three sources of reserves could be coordinated to reveal the complexities within which he worked (Chapter 2). After that we explore Morgan’s normal business routines, describing his routine syndicate business in much more detail (Chapter 3). We then turn to a more chronologically ordered story, starting with his early, formative days in London and the panics before the National Banking Era began in 1863 (Chapter 4). We note his quickening pace of development in actions taken during the Panics of 1873, 1884, 1890, and 1893, with rocky relationships, close calls, outright failures, but also some spectacular successes along the way (Chapter 5). Then we turn to Morgan’s first effort to quell a system-wide crisis, not just a panicked banking system, but one in which the US Treasury nearly ran out of gold reserves in 1895 and 1896, threatening the international gold standard and US public finances. His ability to convince and coordinate domestic investors as well as major overseas agents like the Bank of England and the House of Rothschild in the refunding of the Treasury’s gold stock comes into sharp focus in his efforts in 1895/96 (Chapters 6 and 7). A few smaller crises before the Panic of 1907 reveal how Morgan had settled into the role of a de facto lender of last resort by coordinating small groups of Clearing House banks when their association did not (Chapter 8). Finally, the great Panic of 1907 sets the stage for Morgan’s powers as a lender of last resort to come into full view, coordinating funds from all three sources of reserves to save the banking system, the stock exchange, several large brokerages, and even the City of New York (Chapters 9 and 10). We examine the aftermath of the Panic and Morgan’s efforts in 1908 to recapitalize his own firm and others (Chapter 11). Finally, we examine Morgan’s legacy and relevance to ongoing modern discussions (Chapter 12), from finding echoes of his crisis coordination routines in the terms of the Aldrich–Vreeland Act in 1908, to finding possible motivations for his tacit support for founding the Federal Reserve in 1913, to finding suggestions that his pricing approach to last resort lending could illuminate how supplementary funding to public last resort loans could be structured today.

Table 1.2Long description

Table listing 40 financial transactions taken by Peabody and Morgan firms during financial crises from 1837 to 1908. Each row includes the transaction number, year, description of the action, the risk management technique pricing: collateralized, negotiated, auction, equity, pricing terms, the size of the deal in dollars, whether the action was pitched, enacted, or a preventive measure, and the corresponding annual net profit or loss across Morgan firms. Early entries from 1837 to 1857 show actions under Peabody, such as collateralized Bank of England loans. Later entries from 1870 onward involve Morgan firms engaging in large-scale national and international loans, market interventions, and coordinated syndicates, especially during the 1907 financial crisis. Notable repeated actions include collateralized loans at varying rates, auctioned money pools, equity-based recapitalizations, and active involvement with central banks and government officials. Deal sizes range from $0.4 million to $100 million, with profits and losses fluctuating significantly over time.