Introduction

Seafood production constitutes an important but relatively understudied component of agri-food issues. Intensive aquaculture, in particular, has received little attention in critical agri-food research so far. Yet, as wild fish catches stagnate globally, marine aquaculture (farming of marine species) have started to assume a bigger role in seafood production. Consequently, we increasingly observe an expansion in the intensive and larger-scale aquaculture operations typically done by a few vertically integrated multinational corporations based on global commodity chains connecting different parts of the Global North and Global South countries through trade relations (Çifçi Reference Çifçi2024; Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà Reference Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà2019; Olafsdottir et al. Reference Olafsdottir, Mehta, Richardsen, Cook, Gudbrandsdottir, Thakur, Lane and Bogason2019; Rainbird and Ramirez Reference Rainbird and Ramirez2012). Tracking these global commodity chains of farmed fish has potential for uncovering the changing power dynamics and their socio-ecological implications for the production and consumption of seafood worldwide.

Since the 1950s, seafood production has been substantially restructured: the traditional labor-intensive, small-scale model of fishing and aquaculture has been replaced by capital-intensive modes of production. In this process, fishing activities became increasingly industrialized and expanded geographically, to new regions, farther offshore, and into deeper seas and oceans (Clausen and Clark Reference Clausen and Clark2005; Pauly et al. Reference Pauly, Christensen, Dalsgaard, Froese and Torres1998). As a result, marine fish catches increased substantially from the 1970s onwards; however, simultaneously, overcapacity and overaccumulation of capital in industrial marine-capture fisheries led to overfishing, collapse of various fish stocks, and degraded marine ecosystems (Pauly Reference Pauly2018). Not only the habitats of marine species, but also the livelihoods of fisher people and coastal communities have been undermined in this process. Since the 1990s, due to the expansion and overexploitation of marine resources, fish catches have been stagnating and declining globally (ibid.). For the last decades, therefore, national and international fisheries policies have prioritized intensive aquaculture to compensate for the global fall in marine fish catches. In this context, intensive marine aquaculture has received attention in the scientific literature as a technical, spatial, and/or socio-environmental fix (Brent et al. Reference Brent, Barbesgaard and Pedersen2020; Longo and Clark Reference Longo and Clark2012; Saguin Reference Saguin2016). This emphasis on intensive aquaculture was based on the idea of replacing a hunting- and gathering-type of fishing activity by a more controlled cultivation model in the seas and oceans, following in the footsteps of the “Green Revolution,” through mechanization, vertical integration, economies of scale, intensified use of inputs such as feed and medicines, and capital-intensive production techniques carried out by a handful of globally operating large-scale aquaculture enterprises that dominate the aquaculture and seafood production sector today.

This transformation of seafood production practices and expansion of globalized and capitalized chains have led to complex international trade dynamics between the Global South and Global North, as well as rising inequalities along the seafood chain. To understand these structural changes in seafood production, in this article, we focus on two distant geographies, Turkey and West Africa, and two marine fish species, farmed sea bass and sea bream (SBSB), the two most important exported fish species by the Turkish aquaculture enterprises.

Beginning from the 2000s, the Turkish aquaculture sector emerged as an important actor in the global value chain of SBSB production and is currently the primary supplier of these two species to the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom (UK). While Greece led global SBSB production in the 2005–2012 period, after the economic crisis in Greece, vertically integrated and large-scale (with annual production higher than 1,000 tonnes) Turkish aquaculture companies became the leading actors in global SBSB production (WWF 2021), considered as “consolidated and mature” similar to the “Norwegian-dominated salmon industry” (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2025, 3). A few large Turkish aquaculture corporations like Kılıç Deniz, for instance, expanded their operations beyond the production of SBSB. Their operations span the upstream activities (fish meal and fish oil (FMFO) production in West Africa and fish feed production in Turkey) towards further downstream operations (distribution and sales in Europe and the UK) in the supply chain (Çifçi Reference Çifçi2024; Knudsen Reference Knudsen2025). Kılıç Deniz, for instance, became one of the top fifteen aquaculture corporations worldwide, with its sales of US$ 500 million in 2023 (GRAIN 2024).

Indeed, the period between 2001 and 2017 was marked by increasing integration of Turkey into global value chains, high economic growth, and rising exports (World Bank Group 2022). The country rose from a “basic manufacturing” country to an “advanced manufacturing and services” country in the last decade via supportive government policies encouraging rising exports (ibid.). While the most important commodities in terms of engagement in global value chains were motor vehicles, metals, apparel, and other machinery and electrical equipment (ibid.), agri-food commodities such as cotton and farmed seafood (e.g. farmed SBSB) also became part of the global value chains at about the same time. Third-party certification for sustainability received attention in this period with its potential to increase the exports of these commodities. For instance, certification for organic cotton and “better cotton” was adopted by cotton farmers in Şanlıurfa with the hope of increasing access to international markets and exports (Kahraman Reference Kahraman2019). Similarly, SBSB producers adopted several certifications for product quality, safety, and sustainability in order to become integrated in the global SBSB value chain (Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà Reference Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà2019; Knudsen Reference Knudsen2025). In the same period, the aquaculture sector received substantial governmental support, in terms of subsidized credits, tax rebates, and further financial support to reduce investment costs in Turkey (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2025).

Turkey’s geopolitical interests in Africa (Financial Times 2024) coincided with and supported rising SBSB production. Growing political and economic relations of Turkey in Africa led to multiple bilateral agreements with African countries including Mauritania, Senegal, and Somalia, where Turkish fishing vessels started to catch small pelagic fish to be used in the feed production for SBSB production. Moreover, the “agriculturalist” approach adopted by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry over the last five decades was also instrumental for conceptualizing and supporting “fisheries” as another form of agricultural practice where the aim was to increase seafood production (via aquaculture) rather than managing marine fish stocks sustainably (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2004, Reference Knudsen2009, Reference Knudsen2025). Collaboration with Japanese and Norwegian experts since the 1990s for increasing aquaculture production was also an integral part of the Ministry’s fisheries policy, which facilitated capacity building of Turkish aquaculture companies for rising SBSB production from the 2000s onwards (ibid.).

The present study adopts a single commodity approach using the theoretical lens of “commodity frontiers” (Moore Reference Moore2000) to offer insights into the Turkish aquaculture companies’ roles and strategies in the global value chain of SBSB, examining its trade dynamics, unequal relationships, and socio-ecological implications in West Africa and Turkey. Our research questions are two-fold: first, we focus on how seafood production has been transformed via expanding commodity frontiers of capital-intensive marine aquaculture of SBSB in Turkey. Second, we aim to uncover why and how SBSB production continues to lead to global and regional socio-ecological inequalities and injustices along the value chain of SBSB.

Methodologically, the research is based on in-depth interviews conducted with key stakeholders of the aquaculture and fish feed sectors in Turkey and a review of non-governmental organization (NGO) reports, legislative documents, and the International Trade Centre (ITC) Trade Map database. By using political economy and political ecology lenses, we aim to offer critical insights into the agrarian change and political economy and ecology of agri-/seafood systems by scrutinizing the expansion of marine commodity frontiers together with power relations along the global value chain of SBSB.

The article is structured as follows: the theoretical framework focusing on the expansion of marine commodity frontiers, on which we build our study, is presented in the next section. The methodology that we employed for this research is then presented. The following section provides our findings on the global value chain of farmed SBSB, uncovering the dominant and complex role of Turkish aquaculture companies. We then scrutinize the upstream of the value chain, on FMFO production in West Africa, and then focus on the socio-ecological implications of the SBSB value chain in West Africa and Turkey. The last section brings together the analyses of the expanding marine commodity frontiers with the current dynamics of agri-/seafood systems and concludes the article.

Theorizing and tracking the global commodity chains of farmed fish at the expanding marine commodity frontiers

The industrialization of seafood production and the increasing reliance on capital-intensive and technologically advanced fishing methods in marine-capture fisheries have been escalating since the 1960s (Pauly et al. Reference Pauly, Christensen, Dalsgaard, Froese and Torres1998). At its initial stages, industrialization of fishing increased the global catches substantially; however, from the 1990s onwards, fish catches stagnated globally and eventually fell, even though the fishing effort of the overcapitalized industrial fisheries was still rising. In response to globally declining catches, intensive aquaculture production was proposed as an alternative to the collapsing wild fish stocks with the hope that it could meet the increasing global demand for seafood (Majluf et al. Reference Majluf, Matthews, Pauly, Skerritt and Palomares2024). Some scholars have conceptualized this strong emphasis on and support to intensive aquaculture as a techno-spatial and ecological “fix” (Brent et al. Reference Brent, Barbesgaard and Pedersen2020; Clausen and Clark Reference Clausen and Clark2005; Longo and Clark Reference Longo and Clark2012) and as a socio-technical innovation (Nolan Reference Nolan2019). While extensive aquaculture had long been a traditional way of cultivating fish species, typically done by subsistence producers, the recent technologically efficient, capital-intensive aquaculture methods emerged and expanded to new geographies and to new species, bringing about a diverse set of socio-ecological implications and injustices (Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà Reference Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà2019).

The globalization and capitalization of seafood production systems continue with a range of capitalist expansionary dynamics in the seas and oceans (Campling et al. Reference Campling, Havice and McCall Howard2012; Clausen and Clark Reference Clausen and Clark2005; Saguin Reference Saguin2016). These expansionary dynamics take a range of forms in marine environments. First, intensive aquaculture became a new “commodity frontier” to compensate for the “maturing commodity frontiers” in the industrial-capture fisheries, which we elaborate on in more depth below. Second, aquaculture companies continue to move to new geographies to open new fish farms and fish feed facilities. Third, there is another move – of both aquaculture enterprises and industrial fishing fleets – to new geographies with the purpose of extracting abundant raw materials there, i.e. a rush to small pelagic fish to be converted to FMFO and then to fish feed, mostly used to feed farmed fish. These “raw materials,” in other words, abundant smaller fish species that are high in nutritional value, but low in economic value, are usually sourced from geographies far away from the final farmed fish production. Fourth, aquaculture enterprises intensify their operations and utilize vertical integration so that they can increase their profits at each stage of the global supply chain. Fifth, they employ several marketing strategies such as third-party certification or bilateral/multilateral trade agreements to increase their marketing power and dominate global seafood markets (Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà Reference Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà2019).

To analyze this transformation of seafood production in the last decades, in this study, we draw on Jason Moore’s approach to the expansion of “commodity frontiers,” which synthesizes the global commodity chains perspective with world-systems theory (Moore Reference Moore2000). The global commodity chain analysis mainly focuses on “labor and production processes whose end result is a finished commodity” starting from the final product and following the chain backward until the initial steps of raw material extraction (Hopkins and Wallerstein Reference Hopkins and Wallerstein1986, 159). Building up on that approach, the commodity frontiers approach enables us to uncover the geographical expansion of extractive industries and the link between ecological transformation and the expansionary logic of capitalism by focusing on firms’ strategies on the production side as well as the relations of exchange from a world-historical perspective (Andreucci and Kallis Reference Andreucci and Kallis2017; Moore Reference Moore2000, Reference Moore2010a, Reference Moore2010b; Saguin Reference Saguin2016).

The global value chain literature, on the other hand, expands on the global commodity chain literature by emphasizing that these final products need not to be homogeneous commodities, but can also be differentiated products catered to the needs of final consumers. However, the global value chain analysis mostly lacks a specific focus on the appropriation and transformation of nature (Baglioni and Campling Reference Baglioni and Campling2017) and mostly prioritizes the investigation of exchange relations rather than the ecological and political relations on the production side. Yet, this is an important point that needs further analysis because capitalist enterprises (or states) seek to accumulate capital by utilizing “cheap labor” and “cheap nature.” This is why they often need to move their operations to new geographies (“commodity widening” as defined by Moore Reference Moore2010b), where they can extract abundant resources for low cost, mostly entailing dispossession and/or displacement of local communities, or grabbing of local resources (Andreucci and Kallis Reference Andreucci and Kallis2017; Nolan Reference Nolan2019), and hence where the production costs are the lowest possible. After the initial stage of opening of new commodity frontiers, “commodity deepening” strategies often follow, through a range of socio-technical innovations to increase the surplus obtained (Campling et al. Reference Campling, Havice and McCall Howard2012; Moore Reference Moore2010b; Nolan Reference Nolan2019). However, this appropriation involving commodity widening and deepening often leads to “maturing” conditions where profits reach their peak, and, after this stage, mature frontier conditions lead to the “closing” of a frontier or to the search for new ones (Campling et al. Reference Campling, Havice and McCall Howard2012; Nolan Reference Nolan2019).

To date, only a few scholars have applied the theoretical framework of the expansion of commodity frontiers to understand capitalist accumulation from the seas and oceans. Some of these studies focus uniquely on capture fisheries (Campling et al. Reference Campling, Havice and McCall Howard2012; Nolan Reference Nolan2019), while others include aquaculture–fisheries interactions to understand the current complex dynamics in seafood production (Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà Reference Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà2019; Saguin Reference Saguin2016). Most of the critical social science studies on aquaculture production, on the other hand, either consider intensive aquaculture as a socio-spatial or “protein fix” (Brent et al. Reference Brent, Barbesgaard and Pedersen2020) or as “enclosures” of marine spaces and a marine “metabolic rift” (Clausen and Clark Reference Clausen and Clark2005). These studies made significant contributions to the understanding of seafood systems and capitalist production relations; however, ecological and political dynamics of intensive (marine) aquaculture-capture fisheries relations as well as accumulation strategies from the perspective of commodity frontiers and agrarian change still need further attention.

The present article is a contribution to a special issue of New Perspectives on Turkey on the contemporary developments in the Turkish agrarian landscape through the lens of a single commodity focus. While other valuable contributions to this special issue examine the complex relations around agri-foods such as sweet cherries (Alt Reference Alt2025, adopting a commodity-frontier approach like the present article), our article analyzes a relatively understudied commodity in critical agri-food studies, namely, farmed SBSB using the theoretical approach of commodity frontiers (Moore Reference Moore2000). With this analysis, we aim to contribute to the critical discussions on Turkish agrarian “landscapes” by demonstrating how capitalism’s expansionary logic in the appropriation of “cheap nature” unfolds in Turkish (as well as African) “seascapes” through the global value chains of SBSB. We believe the discussions in this special issue are even more important given that there is only a small number of studies addressing agri-food commodities on the intersection of globalized value chains, third-party certification, and commodification of (sea-)food in Turkey (Kahraman Reference Kahraman2019; Suzuki Him and Gündüz Hoşgör Reference Suzuki Him and Gündüz Hoşgör2018).

Methodology

The methodology we adopted for this research encompasses qualitative methods that include a review of (i) sector and NGO reports with a global, regional, or national focus; (ii) governmental and legislative documents; (iii) ITC Trade Map dataset; and (iv) semi-structured in-depth interviews with key stakeholders from the aquaculture and fishing sectors and other social actors as explained below.

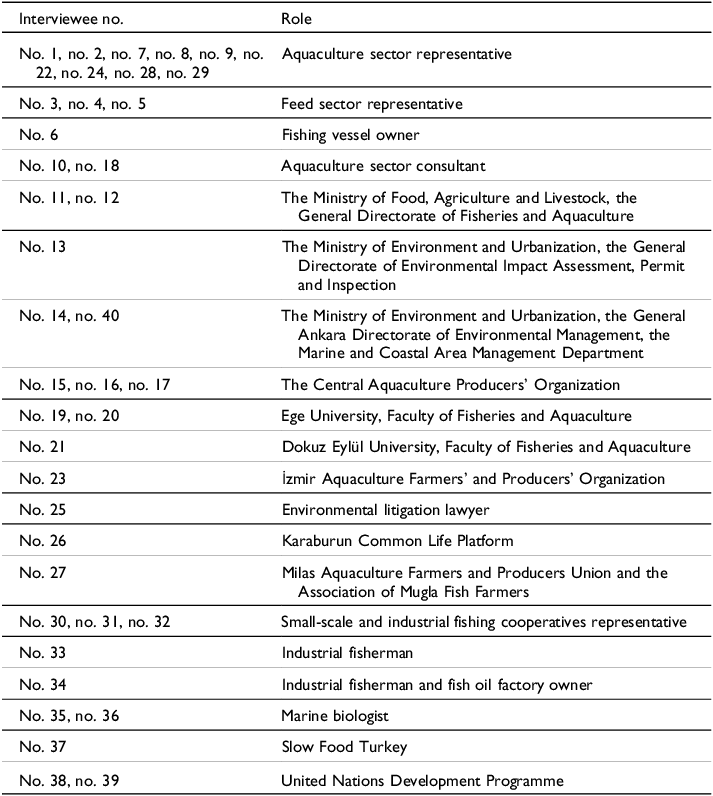

The data-gathering process benefited from two periods of fieldwork. The first one was conducted in İstanbul, Ankara, İzmir, and Muğla between 2015 and 2016 when the significant growth of the aquaculture sector in Turkey was becoming visible. In this period, thirty in-depth interviews were carried out with key stakeholders representing the aquaculture and fish feed sectors, marine scientists, governmental organizations, environmental lawyers, industrial and small-scale fishers, as well as civil society representatives. In the second phase in 2023, ten semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted online with fewer but more established actors in the field, including the representatives of aquaculture enterprises and the fish feed sector, and aquaculture consultants from Turkey. Even though the second period of interviews included fewer respondents, these actors were able to represent around 54 percent of Turkey’s total farmed SBSB production in 2023, and approximately 86 percent of the fish feed production. In total, we were able to reach forty interviewees for the study, selected first through a preliminary search to identify the key actors and later via the snowball sampling method in which each respondent provided the contacts of further key actors for the study (see Table 1 for the list of interviewees).

Table 1. List of interviewees

Finally, we reviewed the ITC Trade Map database for farmed SBSB production, which enabled us to track its global trade patterns. We also used the relevant commodity codes to retrieve trade data for FMFO imports to Turkey, which are being used for fish feed production. The data obtained gave us crucial insights for uncovering the role of the Turkish aquaculture enterprises in the global value chain of the farmed SBSB.

The data from in-depth interviews were transcribed and coded through open-coding methods, and analyzed to identify the role of Turkish aquaculture enterprises in the global SBSB value chain. Together with the data obtained from the ITC Trade Map database and secondary sources, the interviews enabled us to uncover the expansion of marine commodity frontiers as well as the rising inequalities along the global SBSB chain, which will be discussed in the next section with further empirical details.

Growing SBSB production and exports from Turkey to Europe and the UK

In the last two decades, Turkey has emerged as the dominant producer of farmed SBSB globally. While the Greek aquaculture companies had been dominating SBSB production until 2013, the Greek financial crisis put an end to this (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2025; WWF 2021). From 2002 to 2022, the production of sea bass in Turkey increased ten-fold, and production of sea bream grew twelve-fold (General Directorate of Fisheries and Aquaculture 2023). Figure 1 depicts the recent growth of SBSB production in Turkey from 2000 onwards.

Figure 1. Sea bream and sea bass production in Turkey between 2000 and 2022 in tonnes.

Source: General Directorate of Fisheries and Aquaculture (2023)

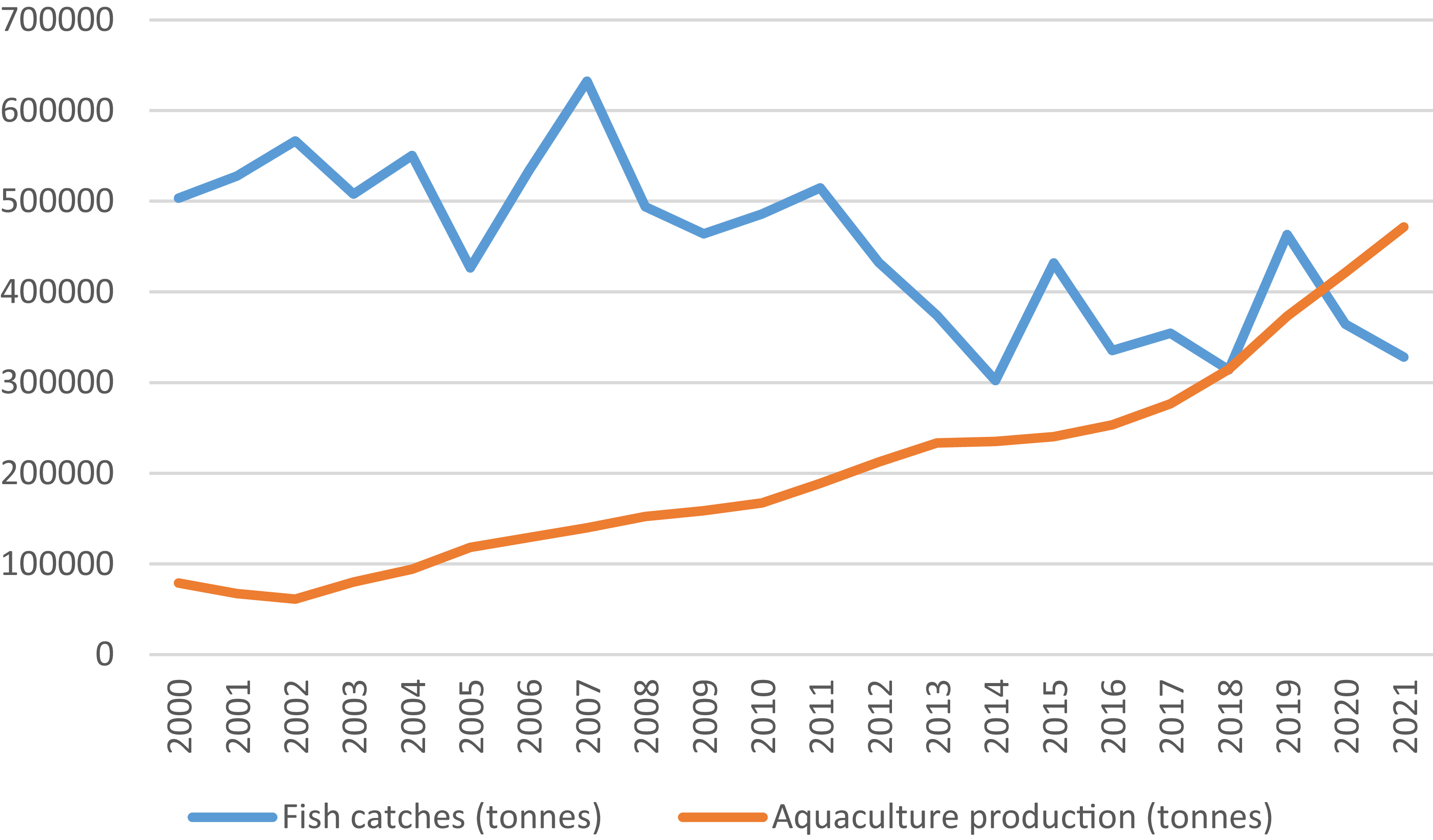

This surge in SBSB production was mainly achieved through government subsidies provided to the aquaculture sector that began in the 1990s. The specific subsidies provided to aquaculture between 2003 and 2019 amounted to US$ 743 million (Atalay and Maltaş Reference Atalay, Maltaş, Çoban, Demircan and Tosun2020); however, more generalized support in terms of various types of investment and export benefits likely exceed this figure (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2025). Since the 1970s, the “agriculturalist” approach adopted by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry had been instrumental for increasing the attention to and support for aquaculture production in Turkey, as the Ministry and other government authorities considered aquaculture as an economic activity to increase “production” and exports rather than ensuring sustainable use of marine resources (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2009, Reference Knudsen2025). Furthermore, economic liberalization from the 1980s onwards created an economic and political environment favorable for foreign investors, including Norwegian capital, which played an important role for importing equipment and feed from Norway to the Turkish SBSB sector (ibid.). As a result, both total aquaculture production and SBSB production and exports of seafood in Turkey rose substantially. In 2020, total aquaculture production surpassed the wild marine fish catches for the first time in history (Çöteli Reference Çöteli2023) (Figure 2). In 2022, the country exported about 245,000 tonnes of seafood to ninety-six countries, generating a revenue of US$ 1.6 billion, most of which originates from the exports of SBSB in addition to rainbow trout (Turkish salmon) (Dünya Gazetesi Reference Gazetesi2023). The growth of demand in Europe and the UK for SBSB grew in the same period as well (Llorente et al. Reference Llorente, Fernández-Polanco, Baraibar-Diez, Odriozola, Bjørndal, Asche, Guillen, Avdelas, Nielsen, Cozzolino, Luna, Fernández-Sánchez, Luna, Aguilera and Basurco2020; WWF 2021).

Figure 2. Wild fish catches versus aquaculture production in Turkey (in tonnes).

In 2022, about 40,900 tonnes of sea bass were exported from Turkey to its top five export destinations: the UK, Italy, the United States, the Netherlands, and Greece. In addition, 53,100 tonnes of sea bream were exported to Italy, Greece, the Netherlands, Spain, and Portugal in the same year (International Trade Centre 2023). The total value of these exports amounted to US$ 486 million (ibid.). While the exports of SBSB to Europe had been mainly fresh or frozen whole fish in the past, consumer demand has changed this towards increasing product differentiation including fish fillets in serving-size bags along with their sauce, for instance (WWF 2021). The total quantity of exports to the EU is growing; however, the growth in value terms has been declining since 2017 due to the oversupply and falling prices of SBSB in European markets (WWF 2021).

Currently, most of the Turkish aquaculture facilities producing SBSB are located in İzmir and Muğla provinces. As of 2019, there were 380 fish farms rearing SBSB in Turkey (WWF 2021). Most of the leading aquaculture companies producing SBSB are vertically integrated throughout the value chain in terms of fish feed production, hatchery, growth of juveniles, further grow-out, processing, packaging, transportation, sales, and marketing in Europe and the UK (ibid.). Vertical integration has been an ongoing process and strategy of economically powerful aquaculture firms since the beginning of the 2010s (Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà Reference Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà2019). For instance, Gümüşdoğa, Kılıç Deniz, and Group Sagun have managed to expand their operations – as well as marine commodity frontiers in SBSB production (ibid.) – and established their own companies in Greece, Italy, and the Netherlands to enable marketing and distribution of their products. Our interviewee representing one of the biggest Turkish aquaculture companies noted the following:

There is high demand for SBSB in Europe. We have a distribution company in Greece that operates in the form of a mobile app to deliver our products to our customers. Our customers there are not end-users, but businesses like restaurants, hotels, and fish markets. The company has been in operation since 2015 (Interviewee no. 1, aquaculture sector representative).

The Netherlands constitutes an important distribution center for Europe in terms of Turkish SBSB production:

You observe the Netherlands taking the lead in exports, this is because it functions as our distribution center for Europe (Interviewee no. 7, aquaculture sector representative).

Initially, in the 1990s, Norwegian experts played a crucial role in the transfer of know-how for SBSB production, and Norwegian aquaculture companies continue to play an important role in SBSB aquaculture in terms of the equipment used in SBSB production as well as the production of feed and equipment (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2025). Turkish aquaculture companies have further engaged in recent technical innovations such as vaccination, automatic feeding systems, and recirculating aquaculture systems for hatcheries, which have been enhancing “commodity-deepening” strategies in the SBSB sector (Atalay and Maltaş Reference Atalay, Maltaş, Çoban, Demircan and Tosun2020; WWF 2021).

Overall, we observe the Turkish SBSB sector developing into a globally dominant actor from the 2000s onwards, with the help of governmental support for increasing production and exports for aquaculture. In this process, Turkish aquaculture companies accumulated capital and expertise and made further steps towards ensuring access to their most essential input, namely, fish feed mainly produced from FMFO in West Africa, which we explore in the next section.

Going upstream in the global SBSB value chain: expanding commodity frontiers of Turkish SBSB production in West Africa for fish feed

Farming of carnivorous species such as SBSB requires huge volumes of aquaculture feed processed, mostly, using FMFO, which are derived from wild stocks of small pelagic fish such as anchovy, sardines, and sardinella. In addition, non-marine ingredients such as soybean meal and by-products of the fishing industry are also added to the fish feed (Fry et al. Reference Fry, Love, MacDonald, West, Engstrom, Nachman and Lawrence2016). Yet, the importance of FMFO as a crucial ingredient still continues for the aquaculture sector (Majluf et al. Reference Majluf, Matthews, Pauly, Skerritt and Palomares2024). FMFO is mostly extracted in the Global South, with Northwest Africa being the key supplier. The production of feed for aquaculture has been rising steadily since the 2000s, its volume tripling from 2000 to 2020 (ibid.). Global demand for FMFO has been growing mainly due to the aquaculture sector (Thiao and Bunting Reference Thiao and Bunting2022). This growth is very problematic, as it often leads to overfishing of small pelagic fish, damages marine ecosystems, diverts wild fish catches from direct human use to aquaculture production, undermining food security and livelihoods in low-income countries, and reduces the traceability of the fish feed due to the globalization of the FMFO trade (Shea et al. Reference Shea, Wabnitz, Cheung, Pauly and Sumaila2025; Thiao and Bunting Reference Thiao and Bunting2022).

The Fish in:Fish Out (FIFO) metric is the primary indicator measuring how much wild fish is required to produce 1 kg of farmed fish (Majluf et al. Reference Majluf, Matthews, Pauly, Skerritt and Palomares2024). While its magnitude for different species is disputed among marine scientists and aquaculture sector representatives, the FIFO metric in fact indicates “the specific dependence aquaculture has on wild capture fisheries” even though “much of the aquaculture sector [is] seeking to portray farmed seafood as a solution or alternative to wild capture fisheries” (Tacon et al. Reference Tacon, Metian and McNevin2022, 136). Indeed, since its first estimation in the 2000s by Naylor et al. (Reference Naylor, Goldburg, Primavera, Kautsky, Beveridge, Clay, Folke, Lubchenco, Mooney and Troell2000), FIFO has been shown to be substantially larger than 1 for carnivorous species (including SBSB), implying serious reliance on wild fish stocks.

While China and Norway have traditionally dominated the global FMFO imports in the last two decades, Turkey has recently emerged as one of the most important fish meal importers worldwide, with at least 6 percent of imports globally in 2019 (International Trade Centre 2023; Thiao and Bunting Reference Thiao and Bunting2022). Most of the FMFO imported to Turkey is used for fish feed production for farmed SBSB.

Initially, the Turkish aquaculture companies relied on anchovies and sprat for producing fish feed, which was mainly captured in the Black Sea by large-scale industrial fishers, initially in Turkish waters. However, later, Turkish industrial fishers expanded their commodity frontiers to other countries’ waters in the Black Sea, to Georgia and Abkhazia in the 1990s. Yet, the Black Sea fisheries went through serious socio-ecological crises in the same time period: the stocks of top predator species declined mainly due to the growing and intensifying fishing activities of technologically advanced industrial fisheries. Overfishing and invasive species were putting further pressure on the remaining fish stocks, and the result was a significant fishery crisis for small-pelagics, especially, anchovy, in the years 1989–1990 (Ulman et al. Reference Ulman, Zengin, Demirel and Pauly2020). As a result, over the last fifty years, at least seventeen fish species became commercially extinct in the Black Sea (ibid.). Today, the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea combined have the second most overfished stocks in the world (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2022). Anchovy catches in Turkey have been declining as a result of this process as well, from 280,000 tonnes in 2000 down to 126,000 tonnes in 2022 (General Directorate of Fisheries and Aquaculture 2023).

In response to the declining catches in the Black Sea (despite an increase in fishing effort), Turkish industrial fishers with the biggest vessels and capital started to expand their geographical reach to African waters by employing “commodity-widening” strategies. Starting from 2015, Turkish purse seiners (gırgır in Turkish) but, also, to a lesser extent, trawlers (trol in Turkish) with a large fishing capacity (vessel length varying between 33 to 50 meters) expanded their fishing activities to West African waters. Expansion was first to Mauritania, with which in 2018 Turkey signed a bilateral fishing agreement,Footnote 1 enabling Turkish vessels to buy fishing licenses and quotas in Mauritanian waters to catch pelagic fish species.

There are currently three categories of fishing activities in Mauritania: artisanal, national coastal, and industrial offshore fisheries. The second category is dominated by Chinese and Turkish fishing vessels, whereas the third category is dominated by European vessels operating within a system of bilateral fishing agreements with Mauritania (T.C. Ticaret Bakanlığı 2022). Of the fish caught within the second and third categories, 90 percent are pelagic fish (ibid.). Turkish fishing vessels are granted concession rights and buy fishing licenses when they sign contracts with fish-processing and marketing enterprises in Mauritania, and they have an obligation to land the fish they catch in Mauritania (ibid.). As of June 2018, there were forty-two Turkish fishing vessels operating in Mauritanian waters catching small pelagics, including sprat, sardine, mackerel, and horse mackerel (Öztürk Reference Öztürk2018). These wild fish species are processed as FMFO in Mauritania, mostly by Chinese and Turkish companies (Financial Times 2024; Öztürk Reference Öztürk2017). Major Turkish aquaculture companies involved in fish feed manufacturing, as a form of vertical integration in the value chain, made strategic acquisitions of FMFO factories in Mauritania to enhance the accessibility of high-quality fish meal for fish feed production (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2017). Currently, Mauritania ranks second in the number of FMFO factories globally, with forty-two factories, after Peru (Shea et al. Reference Shea, Wabnitz, Cheung, Pauly and Sumaila2025).

While Mauritania was the first destination for Turkish industrial fishers in African waters, Turkey signed bilateral fishing agreements with other countries in Africa including Somalia,Footnote 2 Senegal,Footnote 3 Algeria,Footnote 4 Guinea,Footnote 5 the Gambia,Footnote 6 Tunisia,Footnote 7 and Oman.Footnote 8 According to the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Turkish industrial fishers are catching about 1 million tonnes of fish in the oceans worldwide (typically in African waters), which is about three times the catch volume in Turkish waters (NTV 2023). The agreements signed with African countries are part of more general, geopolitical strategic interests of Turkey in Africa and involve not only cooperation in terms of fisheries, but also in “trade, investment, cultural projects, security and military cooperation, development projects” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2025).

Recently, fisheries regulations in Mauritania became stricter: a new Mauritanian legislation requires that a larger proportion of fish catches be processed as canned or frozen fish by fish meal producers so that it is directed towards direct human consumption. Our interviewees from the aquaculture sector confirmed this changing trend:

[The] Mauritanian government started to prioritize canned products, for example, due to their higher added value, rather than fish meal. Fish meal factories have been told to set up freezing and packaging facilities. We could resist this for three to four years. Now, with the pressure from the Mauritanian government, our business has reached an impasse. We are slowing down operations there (Interviewee no. 2, aquaculture sector representative).

Consequently, the number of Turkish vessels in Mauritania fell to twenty-five recently (Interviewee no. 6, fishing vessel operator). However, it is not only the new Mauritanian directive that led to a downsizing of Turkish fishing operations in Mauritania. Small pelagic fish catches have been declining in West Africa substantially since the rise of fish meal processing in 2010 in the region, growing about ten-fold between 2010 and 2019 (Greenpeace Africa and Changing Markets Foundation 2021). Indeed, recent reports show that small pelagic fish stocks are under extreme fishing pressure in West Africa (Thiao and Bunting Reference Thiao and Bunting2022). For instance, sardinella and bonga are already overexploited, mainly related to the operations of the fish-based feed industry there (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2020). However, these species are essential for local communities living in Africa, in terms of nutritional value and their socio-economic needs, especially for low-income groups (Corten et al. Reference Corten, Braham and Sadegh2017; Thiao and Bunting Reference Thiao and Bunting2022). Civil society organizations reported that most of the fish caught in the region is directly processed into FMFO for export purposes (Greenpeace Africa and Changing Markets Foundation 2021; Western Sahara Resource Watch 2022). As a result, prices of locally consumed fish rose, and local communities, especially local women processing fish, are severely impacted by the growing fish meal industry in the region (Thiao and Bunting Reference Thiao and Bunting2022). This process endangers local food security in West Africa and leads to protests by local people (EJ Atlas Reference Atlas2021; Greenpeace Africa and Changing Markets Foundation 2021; World Ocean Review n.d.).

In fact, Turkish industrial fishers operating in Mauritania complained in a parliamentary meeting in Turkey that they have exhausted the fish stocks in Mauritania, admitting they did not comply with the limits assigned by the fishing quotas there (Yeşil Gazete Reference Gazete2023). In response, however, the Turkish Embassy in Nouakchott, Mauritania, issued a press release, refuting the allegations and stating that the Turkish fleet in Mauritania is well-respected because it complies with the regulations regarding the vessel size (tonnage) limitations and areas closed for fishing (Akşam Gazetesi Reference Gazetesi2023).

Overall, this process of immense expansion and eventual decline implies that marine commodity frontiers are currently “maturing” in Mauritania (Campling et al. Reference Campling, Havice and McCall Howard2012; Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà Reference Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà2019; Nolan Reference Nolan2019), through stricter regulations by the Mauritanian government as well as declining pelagic fish stocks; consequently, the high “ecological surplus” initially obtained by the Turkish industrial fishers is currently shrinking.

In response to the maturing commodity frontiers in Mauritania and West Africa, Turkish industrial fishers have started to expand their operations to new marine commodity frontiers. Oman on the Indian Ocean has emerged as a new commodity frontier, to where Turkish industrial fishers and fishing and aquaculture capital can further expand, seeking for cheap and abundant raw materials – and thus a high ecological surplus – from another ocean:

New fishing grounds are emerging in the Arabian Peninsula [e.g. Oman], and the geographical diversity increases as the amount of catches decreases [in West Africa]. Habitats are being destroyed as a result of overfishing there (Interviewee no. 10, aquaculture sector consultant).

The role of Oman became recently visible in international trade data: in 2022, Morocco, Georgia, Oman, and Mauritania were the main suppliers of fish meal to Turkey; and Norway, Chile, Georgia, and again, Oman, were the top four suppliers of fish oil to the country (International Trade Centre 2023). Our findings from the interviews were in line with the trade data. For instance, fish meal from Morocco and anchovies from the Black Sea (including Georgia and Abkhazia) continue to be an important source of FMFO for the Turkish SBSB production:

The company from which we purchase fish meal has been the same over the years; we’ve been sourcing fish meal from the same producer in Morocco for the last twenty-two years. However, the supply of fish oil is quite variable; using anchovy oil [from the Black Sea] results in higher-quality feed, and adding a certain amount of sardines achieves optimal quality. … The protein content in fish meal varies by country; the protein content in Turkish fish [anchovies] is around 72–74 percent, fish from Morocco 66 percent, and from Peru between 71 and 73 percent (Interviewee no. 5, feed sector representative).

The protein content of anchovies is around 74–75 percent. Anchovy meal is more valuable compared to fish meal coming from Mauritania and Chile. … Fish meal mostly comes from Abkhazia to us, and we also procure from Morocco and Chile. We prefer anchovy as much as possible for fish oil (Interviewee no. 8, aquaculture sector representative).

We source only 15 percent of the fish feed raw materials domestically, while the remaining, particularly fish meal and fish oil, is procured from abroad. We make purchases from countries such as South Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, Peru, and Chile (Interviewee no. 5, feed sector representative).

Another crucial ingredient for fish feed production is plant-based protein from soybean meal (Majluf et al. Reference Majluf, Matthews, Pauly, Skerritt and Palomares2024). About 30 percent of plant-based proteins for the aquaculture feed comes from soybeans (Ergün et al. Reference Ergün, Yiğit, Yılmaz, Çoban, Demircan and Tosun2020). However, the fish feed companies need to import this ingredient as well, as soybean production in Turkey cannot cover the domestic demand, typically from Argentina, Russia, and Brazil (OEC World Reference World2024).

Due to the challenges such as overfishing and climate change, the aquaculture sector is compelled to utilize more plant-based raw materials (Interviewee no. 10, aquaculture sector consultant).

Based on these insights, Figure 3 provides a sketch of the global value chain of SBSB relying on the ITC Trade Map dataset and our interviews. The chain starts with industrial fishing vessels, which catch small pelagics in the Black Sea and in African waters (both in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans). These provide their catches to the FMFO producers in Africa, which is then procured into fish feed in Turkey by fish feed companies, combined with FMFO imported from South America (Peru and Chile, for instance) as well as plant-based proteins from soybean meal, imported from Argentina, Russia, and Brazil. This fish feed is then used by Turkish aquaculture enterprises producing SBSB; the last stage is the exporting of final products to the main destinations in Europe and the UK.

Figure 3. Sketch of the global value chain of SBSB with links to Turkish aquaculture enterprises.

Source. Authors’ compilation based on the ITC Trade Map and interviews

The fish feed industry is making efforts towards decreasing the share of marine-based ingredients in the feed (due to rising prices and declining supply of FMFO globally), and currently the share of FMFO in fish feed is declining (Majluf et al. Reference Majluf, Matthews, Pauly, Skerritt and Palomares2024). Since the 1990s, the feed industry is increasingly using the by-products of the seafood processing industry as well (ibid.). New ingredients are also being developed and tested to replace FMFO in the feed, such as algae, bacteria, yeast, insects, and rapeseed oil in order to reduce dependency on wild fish stocks. However, these experiments have had mixed effects regarding the nutritional requirements and growth of farmed carnivorous fish species, and the question regarding scalability and sustainability of these alternatives still stays open for the future (ibid.). Hence, FMFO are still crucial components of the feed of carnivorous farmed species (Ergün et al. Reference Ergün, Yiğit, Yılmaz, Çoban, Demircan and Tosun2020). Indeed, our interviewees noted that the fish feed for SBSB production in Turkey currently consists of 10–30 percent fish meal, 8–20 percent fish oil, and other (plant-based) protein sources such as soybean, corn, and wheat. Turkish aquaculture companies have also experimented with algal oil, which has a high omega-3 content, replacing fish oil; however, its use is currently quite limited (around 5 percent as a share of non-fish ingredients) (ibid.).

Figure 4 visualizes the global value chain (or the commodity frontiers) of the SBSB production on a world map, depicting the main sources of strategic ingredients for SBSB production, namely, FMFO from Africa and the Black Sea, which is later processed as fish feed in Turkey, the aquaculture facilities (fish farms) in Turkey, and the main export destinations for the SBSB in Europe and the UK (where the Netherlands has a special role in the international trade of SBSB, being a major distribution center for Europe). The next section focuses on the socio-ecological impacts and emerging conflicts and injustices created by the SBSB value chain in Africa and Turkey.

Figure 4. Map of the sea bass and sea bream commodity frontiers linked to Turkish aquaculture production. FMFO, fish meal and fish oil.

Source: Authors’ own compilation

Socio-ecological implications and conflicts of SBSB production at the expanding commodity frontiers in West Africa and Turkey

The surge in fish feed production (Greenpeace Africa and Changing Markets Foundation 2021) has given rise to huge socio-ecological impacts and conflicts in West Africa. Greenpeace Africa estimates that around half a million tonnes of fresh small pelagic fish each year are redirected to FMFO production that could have fed thirty-three million individuals in Africa (ibid.). In Mauritania, for instance, the number of fish meal factories increased from five to forty-one between 2009 and 2020 (Touron-Gardic et al. Reference Touron-Gardic, Hermansen, Failler, Dia, Tarbia, Brahim, Thorpe, Bara Dème, Beibou, Kane, Bouzouma and Arias-Hansen2022), the main buyers of fish meal being Chinese and Turkish fish feed producers (ibid.). The aquafeed industry defends the FMFO industry’s continued exploitation of marine resources by claiming that markets for small pelagic fish for the direct consumption by local residents have never been well established. However, this claim is not true, neither in West Africa, nor in South Asia, where local markets do exist and new markets are emerging with changing consumer preferences (Majluf et al. Reference Majluf, Matthews, Pauly, Skerritt and Palomares2024). The recent surge in FMFO production raises concerns about not only local food security and access to food, but also sustainable use of fish stocks globally (Thiao and Bunting Reference Thiao and Bunting2022). For instance, sardinella and bonga species, used for fish feed production in West Africa, are currently overexploited stocks, for which the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2020) has called for strong and urgent action to rebuild their stocks.

In terms of employment, the few jobs that are created by the FMFO industry are often temporary and uncertain, and, mostly, local residents do not benefit from new lower-grade factory jobs but foreign workers from China or surrounding African countries (Thiao and Bunting Reference Thiao and Bunting2022; Touron-Gardic et al. Reference Touron-Gardic, Hermansen, Failler, Dia, Tarbia, Brahim, Thorpe, Bara Dème, Beibou, Kane, Bouzouma and Arias-Hansen2022). FMFO production raises the price of fish and undermines the availability in local markets for direct human consumption, reducing local livelihoods, especially those of local fish-processing women (Thiao and Bunting Reference Thiao and Bunting2022). In Senegal, for instance, fish consumption fell by 50 percent from 2009 to 2018 (Deme et al. Reference Deme, Deme and Failler2022). There is also evidence that overexploitation of fish in Senegal contributed to the impoverishment and emigration of Senegalese fishing communities to the EU, especially Spain (Pauly et al. Reference Pauly, Nauen, Le Manach, Palomares, Sumaila and Lopez-Ahedo2025). Public health around the FMFO production facilities is also under threat: smoke and waste water issues are common causes of respiratory and skin diseases, particularly for children and older individuals (Majluf et al. Reference Majluf, Matthews, Pauly, Skerritt and Palomares2024; Thiao and Bunting Reference Thiao and Bunting2022). All these factors lead to conflicts between coastal communities in West Africa and the foreign fishing fleets (Desierto Liquido Reference Liquido2016). Artisanal fishers complain that the fishing operations of purse seiners cannot feed the local people with fresh fish as they do not have cooling facilities (Coalition for Fair Fisheries Arrangements 2021). Instead, these fresh fish end up in FMFO factories.

Socio-ecological impacts created by the SBSB aquaculture industry are not limited to West Africa. There are discontent and conflicts around the aquaculture facilities in Turkey as well, especially on the Aegean and Mediterranean coasts, where intensive fish farming pollutes and damages marine ecosystems and has a negative impact on other sectors like tourism and small-scale fisheries (Gazete Vatan Reference Vatan2021). Scientific studies have shown that intensive marine aquaculture is often associated with environmental problems such as discharge and accumulation of heavy metals and organic matter, disease outbreaks, use of chemicals such as antibiotics and pesticides, and genetic, prey-predation, and food-related interactions with other wild species in marine environments (Farmaki et al. Reference Farmaki, Thomaidis, Pasias, Baulard, Papaharisis and Efstathiou2014; Sunlu et al. Reference Sunlu, Başaran, Aksu, Çoban, Demircan and Tosun2020; Zoli et al. Reference Zoli, Rossi, Costantini, Bibbiani, Fronte, Brambilla and Bacenetti2023). Studies specifically focusing on Turkish marine aquaculture production have provided evidence for its potential and observed negative impacts on marine macrofauna (Koçak and Katağan Reference Koçak and Katağan2005), the marine environment, and sediments (Aksu Reference Aksu2009; Küçüksezgin et al. Reference Küçüksezgin, Pazi, Gonul, Kocak, Eronat, Sayin and Talas2021), and on Posidonia oceanica sea meadows vital for the health of Mediterranean marine ecosystems (Koçak et al. Reference Koçak, Uluturhan, Yücel Gier and Aydin Önen2011; Taşkın et al. Reference Taşkın, Bilgiç, Minareci and Minareci2024).

Along the global value chains of aquaculture, some of these negative socio-ecological impacts are being addressed by third-party certification for sustainability (Bush et al. Reference Bush, Belton, Hall, Vandergeest, Murray, Ponte, Oosterveer, Islam, Mol, Hatanaka, Kruijssen, Ha, Little and Kusumawati2013). The main export partners of the Turkish SBSB companies, Tesco supermarkets in the UK and other retailers in Europe, require their suppliers to meet specific product quality and sustainability certifications. With their export-oriented business models, in the late 2000s, the Turkish SBSB sector had already started to comply with EU standards regarding fish welfare and food safety (Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà Reference Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà2019). The main certifications that SBSB companies in Turkey currently adopt are: (i) Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) focusing on environmental and social sustainability, including workers’ rights and traceability along the supply chain; (ii) Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP) covering environmental aspects, food safety, animal welfare, and traceability; and (iii) Global Good Agricultural Practice (GLOBALG.A.P.) on food safety, occupational health and safety, animal welfare, ecological impacts, and transparency along the supply chain (WWF 2021). The ASC has stricter environmental criteria than GLOBALG.A.P. regarding the conservation of the habitat, water quality, biodiversity impact assessment, intentional lethal actions, genetic integrity (including a ban on the use of transgenic fish), energy use, greenhouse gas emissions, and antibiotics use. Social criteria as regulated by the ASC are also stricter, including access of workers to trade unions, protection of young workers (ages fifteen to eighteen years), a wage higher than the national minimum wage (a basic-needs wage), and stakeholder engagement with neighboring communities.

In addition to these key schemes, other schemes adopted by Turkish aquaculture companies are British Retail Consortium (BRC) Global Standard and International Featured Standards (IFS) focusing mainly on food safety and food quality, Friend of the Sea certification addressing environmental sustainability, Sedex membership on social and environmental sustainability including workers’ rights, and International Organization for Standardization (ISO) on food quality, food safety, energy management, and occupational health and safety. Moreover, Halal certification is also obtained to widen the export opportunities in countries with Islamic beliefs dominating food consumption practices (WWF 2021). In contrast to SBSB producers, the exporters of “Turkish salmon” (salmon trout) in Turkey have just recently started to acquire ASC certification to expand their export opportunities to Europe, as these certifications are not required in their previous export destinations in Russia and the Far East (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2025), signaling that acquisition of sustainability certification is strongly contingent upon export market requirements.

The [farmed] seafood sector is more advanced in terms of meeting sustainability standards compared to other sectors [in Turkey] because it is an EU exporter. The use of certifications is very widespread, e.g. certifications like ASC and Best Aquaculture Practices are often met even though they incur costs for the aquaculture enterprises (Interviewee no. 10, aquaculture sector consultant).

We are constantly under inspection. The UK, for instance, has once sent an entire shipment to destruction due to a minor letter error on the label at customs (Interviewee no. 8, aquaculture sector representative).

Our interviewees further mentioned the financial support of the Turkey Exporters Assembly (TIM) that covers a non-negligible proportion of their expenses for acquiring product quality certifications (Interviewee no. 9, aquaculture sector representative). Indeed, TIM has announced that the assembly will provide an annual support of US$ 250,000 for each exporting company (not only in the aquaculture sector but also in other sectors) to compensate them for their certification and laboratory test costs required in the export destination country (TIM, n.d.).

While certification schemes related to environmental and social criteria seem to be promising to improve the production-related impacts of the sector, sustainability certification for the global value chains of seafood is criticized on the grounds that environmental impacts beyond one specific enterprise (for instance, cumulative effects of multiple farms on water quality, degradation of mangroves, etc.) are often not part of these schemes (Bush Reference Bush2018; Bush et al. Reference Bush, Belton, Hall, Vandergeest, Murray, Ponte, Oosterveer, Islam, Mol, Hatanaka, Kruijssen, Ha, Little and Kusumawati2013). Even the ones with stricter criteria like the ASC do not consider environmental costs of processing, distribution, and transportation (Bush et al. Reference Bush, Belton, Hall, Vandergeest, Murray, Ponte, Oosterveer, Islam, Mol, Hatanaka, Kruijssen, Ha, Little and Kusumawati2013) and often reflect the economic interests of powerful actors in the supply chain (Belton et al. Reference Belton, Murray, Young, Telfer and Little2010). Moreover, it has been argued that certification can legitimize the existing extractivist fishing activities, as well as the expanding commodity frontiers of the seafood industry (Campling and Havice Reference Campling and Havice2018; Le Manach et al. Reference Le Manach, Jacquet, Bailey, Jouanneau and Nouvian2020). For instance, the Mauritanian fisheries have been recently assessed as reaching stage 4 of achievement of the environmental NGO Sustainable Fisheries Partnership, which implies that these fisheries are progressing towards sustainable fishing activities. However, this is strongly disputed, as critiques voice their concerns regarding the continued overcapacity and overfishing in West Africa, arguing that Mauritanian fisheries cannot be certified as “sustainable” without a genuine reduction in the number of fish meal factories and overcapacity of the international fishing fleet, including the Turkish purse seiners (Standing Reference Standing2022).

Indeed, our interviews with the aquaculture sector representatives revealed that certifications that SBSB producers acquire tend to adopt a relatively narrow definition of socio-ecological sustainability, ignoring overfishing, overcapacity of the industrial fishing fleet, and other local impacts of the aquaculture industry:

We are transitioning to green energy by enhancing solar-power capacity, and our carbon footprint scores are projected to reach zero by around 2027. Our fishing vessels will be electric-powered. Other major companies are also undergoing a green transformation, and taxes will increase if renewable energy and environmental standards are not met (Interviewee no. 1, aquaculture sector representative).

Sector representatives we interviewed had noted that there is pressure for the substitution of FMFO by other non-fish ingredients and alternative protein sources:

There is now pressure [from the retailers in the EU and the UK] to shift towards plant-based alternatives in fish feed (Interviewee no. 8, aquaculture sector representative).

However, this is not only related to the requirements of certification but is mainly due to the globally rising prices of FMFO. Since whole fish (instead of fish remnants) is mostly preferred for the production of FMFO, declining fish stocks in West Africa have raised the input prices of fish feed production, especially that of fish oil (Touron-Gardic et al. Reference Touron-Gardic, Hermansen, Failler, Dia, Tarbia, Brahim, Thorpe, Bara Dème, Beibou, Kane, Bouzouma and Arias-Hansen2022; Majluf et al. Reference Majluf, Matthews, Pauly, Skerritt and Palomares2024). Indeed, rising FMFO prices as well as prices of alternative protein sources such as soybeans are a big concern for the Turkish aquaculture industry, limiting further growth of the sector:

Until this year, we were growing by 200–300 percent annually, but due to global conflicts and the crisis in China, we won’t take major steps; we’ll stay in the same place for two to three years. We’ve stockpiled fish meal for several years (Interviewee no. 1, aquaculture sector representative).

Given these complex socio-ecological dynamics of SBSB production, the next section synthesizes our findings on the production and exports of SBSB, as well as the fish feed requirements and socio-ecological conflicts along the SBSB value chain with a specific reference to Moore’s (Reference Moore2000) expanding commodity frontiers framework.

Discussion and conclusion

The case of farmed SBSB production illustrates the expansionary dynamics of capitalism in marine environments through the aquaculture–fisheries interactions in Turkish and West African waters. In this section, therefore, our aim is to elaborate on these expansionary mechanisms manifesting themselves in Turkish SBSB production in more depth. To this end, below, we discuss the theory on the expansion of commodity frontiers (Moore Reference Moore2000) together with the empirical data we presented in the previous sections.

First, exploring the chronology/development of the expansionary mechanisms of intensive marine aquaculture in Turkey, we observe that the sector has been supported by governments over the last five decades with an “agriculturalist” approach to increase production and “water produce” exports (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2009, Reference Knudsen2025). From the 2000s onwards, intensive aquaculture was given special attention by the Turkish fishery sector and authorities in order to compensate for the declining wild fish catches and profits of the industrial fishers in the Black Sea. Government subsidies beginning from 2003 promoted the growth of intensive marine aquaculture and encouraged new Turkish enterprises to join the SBSB sector (Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà Reference Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà2019). Governmental support and environmentally suitable conditions of the seas around Turkey led to a significant surge in intensive marine aquaculture production, where SBSB production rose exceptionally quickly, more than ten-fold between 2002 and 2022 (General Directorate of Fisheries and Aquaculture 2023). Given this context, we argue that the expansion of marine commodity frontiers of Turkish SBSB production entails the following main strategies: (i) commodity widening: a geographical expansion of industrial fishing to West Africa and, more recently, to Oman, and establishment of fish feed factories in West Africa; (ii) intensified production and processing of SBSB taking place in Turkey involving commodity-deepening strategies through the use of new technologies in aquaculture production; and (iii) “commodity marketing” strategies of SBSB (Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà Reference Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà2019), within which Turkish SBSB are predominantly supplied to the lead firms in the EU and UK (such as Tesco supermarkets), catering to their requirements as well as consumer preferences there. These strategies demonstrate how Turkish aquaculture enterprises expanded their operations to sustain and increase profits and market share for SBSB (Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà Reference Ertör and Ortega-Cerdà2019; Moore Reference Moore2000).

However, geographical expansion to Mauritania, where, in Moore’s (Reference Moore2000) terms, a high ecological surplus was obtained by both Turkish and Chinese fishing vessels and fish feed factories gave rise to “maturing” frontier conditions, as the harvesting of cheap and abundant resources (small pelagic fish important for the local food and nutritional needs) led to alarming rates of overfishing and overexploited fish stocks, especially those of sardinella and bonga (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2020). Currently, therefore, the Mauritanian waters are becoming a “closing” frontier, similar to Ghana’s small pelagic fisheries discussed by Nolan (Reference Nolan2019), as the fishing and aquaculture industry cannot sustain the same levels of profitability of the last decade, due to collapsing fish stocks and the Mauritanian government’s recent restrictions regarding the fish feed-processing industry. While these conditions of closing frontiers leave the local communities in a severe struggle for their livelihoods (Financial Times 2024; Nolan Reference Nolan2019), the industrial fisheries and aquaculture enterprises were quick to move to other distant waters, for instance, to the productive seas of Oman in the Indian Ocean, to compensate for the falling amount of fish catches and profits.

Second, we argue that not only “cheap labor,” but also “cheap nature” in Turkey and West Africa were important leverage points for the Turkish SBSB producers. The literature on SBSB production emphasizes mostly the first, namely, cheap labor, based on the fact that non-EU countries are in a favorable economic condition because of lower labor costs (Llorente et al. Reference Llorente, Fernández-Polanco, Baraibar-Diez, Odriozola, Bjørndal, Asche, Guillen, Avdelas, Nielsen, Cozzolino, Luna, Fernández-Sánchez, Luna, Aguilera and Basurco2020). Complementing this, there are literature and reports pointing to the constant depreciation of the Turkish Lira as a further source of competitive advantage for the SBSB producers in Turkey (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2017). However, we argue that the boom observed in the farmed SBSB production in the last twenty years in Turkey goes beyond cheap labor and cheap local currency conditions. Rather, the expansion of the fish feed and aquaculture sectors relied heavily on the fact that the “nature is cheap” in Turkey as well as in African waters, where the tremendous negative socio-ecological impacts of the SBSB value chain are easily ignored by the aquaculture sector and governmental authorities. While government incentives for the aquaculture sector and easier licensing of marine enclosures by the government (ignoring the cumulative impacts of fish farms and local environmental conflicts resulting from these negative impacts) made nature “cheap” in Turkish waters, bilateral fishing agreements between Turkey and African countries, as well as the Mauritanian government’s reliance on Turkish (and Chinese) fishing vessels for generating economic revenues and local employment, also rendered nature (marine environments) cheap in West Africa. Therefore, adopting a single commodity focus and tracking both the value chain of SBSB and the “ecological surplus” (Moore Reference Moore2000) that is being extracted by Turkish aquaculture companies, we argue that the expansion of marine commodity frontiers to African waters mainly serves the interests of Turkish aquaculture companies as well as consumers in the Global North (the EU and the UK), including, partially, middle-income Turkish consumers who can afford to buy farmed SBSB (about half of the farmed SBSB is consumed internally in Turkey according to the statistics of the General Directorate of Fisheries and Aquaculture 2023).

Third, vertical integration of Turkish aquaculture enterprises was a critical strategy to increase profits and market share in European markets for SBSB. Integrating the different stages of the value chain in their operations, such as fishing, fish feed production, hatcheries and cultivation of fish, processing and packaging, and distribution and marketing in European centers such as the Netherlands and Greece, they were able to extract a larger share of this ecological surplus. Indeed, similar commodity-deepening strategies have been followed by the salmon aquaculture industry in Norway and Chile, for instance (Feedback Global Reference Global2024; Kvaløy and Tveterås Reference Kvaløy and Tveterås2008; Olson and Criddle Reference Olson and Criddle2008). Moreover, the experimentation and use of the most recent advanced “socio-technological innovations” (Nolan Reference Nolan2019, 2) such as automatic feeding, improved vaccines, and recirculating aquaculture systems in hatcheries further contributed to the commodity-deepening strategies of the Turkish aquaculture companies. However, given the collapsing fish stocks and globally rising prices of FMFO and soybean meal, the aquaculture industry is currently experimenting with other socio-technical innovations, such as the use of algal oil in the feed in order to sustain future profits. Yet, the wide-scale implementation and scalability of these new technologies are currently questionable (Majluf et al. Reference Majluf, Matthews, Pauly, Skerritt and Palomares2024).

Last, but not least, third-party certification schemes, as required by the lead firms in the global value chain of SBSB, such as Tesco supermarkets and other retailers in the EU and UK, were another integral part of the expansion of SBSB production by Turkish aquaculture enterprises. While some of these certificates mainly target food safety and quality standards (e.g. BRC Global Standards, IFS), others are about ensuring environmental sustainability standards of the industry (e.g. ASC, GLOBALG.A.P.). These certificates were vital for the Turkish SBSB companies’ commodity marketing strategies aiming to improve access to European markets and to raise exports, and are also partially supported financially by the Turkish Export Assembly. Indeed, the “Turkish salmon” producers are now acquiring these certificates as well in order to widen their export destinations towards Europe (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2025). In the case of SBSB, Turkish aquaculture companies have been mostly successful in establishing and sustaining operations downstream of the supply chain (sales and distribution) thanks to their adoption of third-party certification and establishment of distribution centers in Europe. Similarly, Bush (Reference Bush2018) argued that eco-certification in the global salmon and shrimp aquaculture value chains constitutes a hands-off form of regulation that is often more successful in chains with a higher degree of vertical integration. In this context, Turkish SBSB production can be considered another case of successful commodity marketing strategies through the adoption of eco-certificates. Further studies are needed to investigate the specific conditions under which third-party eco-certification facilitates the expanding frontiers of SBSB producers in Turkey.

Given the asymmetric power relations between the vertically integrated aquaculture companies and the local fishing communities in West Africa, third-party certifications are arguably “certifying the unsustainable,” hiding the impacts of the feed footprint of aquaculture in West Africa and serving the interests of global aquaculture enterprises (Feedback Global Reference Global2024; Standing Reference Standing2022). Indeed, as the recent GRAIN report argues, intensive aquaculture in “seascapes,” like its counterpart of industrial agriculture on the agricultural “landscapes,” “is about producing global commodities that flow from the cheapest areas of production to wherever they can be sold at the highest price” (GRAIN 2024, 4). Indeed, eco-certification does not ensure that fish stocks in West Africa are in a healthy condition. To the contrary, fish stocks have been collapsing in Mauritania (Touron-Gardic et al. Reference Touron-Gardic, Hermansen, Failler, Dia, Tarbia, Brahim, Thorpe, Bara Dème, Beibou, Kane, Bouzouma and Arias-Hansen2022), Senegal (Pauly et al. Reference Pauly, Nauen, Le Manach, Palomares, Sumaila and Lopez-Ahedo2025; The Guardian 2025), and in Ghana (Nolan Reference Nolan2019), while the “cheap” ecological surplus is appropriated by industrial fishing and aquaculture enterprises in order to be converted first to fish feed and then to economically more valuable farmed fish species, including SBSB. The certification of this process of resource appropriation is a major problem that creates the illusion of “sustainably sourced fish” by obscuring the Global South–Global North power relations and inequalities. There are also several complaints regarding illegal fishing and intentional rotting of pelagic fish by the fishing vessels in Mauritania so that the catch cannot be admitted for direct fresh use by local residents and instead is supplied to FMFO processors (Financial Times 2024).

Given this analysis, we conclude that a closer look at the global commodity chain of farmed SBSB production in Turkey provides crucial insights into the capitalist expansion and agrarian change in land- and seascapes. Turkish industrial fisheries and aquaculture enterprises have emerged as important suppliers of SBSB to the EU and UK, utilizing the ecological surplus in both Turkey and West Africa, and expanding, similar to their counterparts in the farmed salmon industry, via commodity widening, deepening and marketing strategies, thanks to vertical integration, bilateral fishing agreements, socio-technical innovations, and third-party certification schemes hiding the socio-ecological impacts of production. This process, however, has undermined the local access to food and impoverished local coastal communities in West Africa, further contributing to the overexploitation of pelagic fish stocks worldwide. Thus, we argue that expanding commodity frontiers of Turkish SBSB production exacerbated the existing power asymmetries and inequalities between the Global North and Global South via capitalist seafood production and consumption practices.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers and the editors of the Special Issue for their constructive comments.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.