It is difficult to find an account of nineteenth-century Russian music that does not emphasize Anton Rubinstein’s role in the institutionalization of native musical culture.Footnote 1 By establishing the Russian Musical Society in 1859, he gave Russia its first regular professional concert series. By establishing the Saint Petersburg Conservatory three years later, he created the first domestic institution that provided systematic professional training to composers and performers. The RMS instantly became the centre of the Saint Petersburg concert scene and remained so until its demise following the revolution, while the Conservatory’s alumni have gone on to occupy prominent roles in global musical culture ever since Tchaikovsky graduated as part of the first class in 1865. Within a few years, Rubinstein’s brother Nikolai created sister institutions of the RMS and Conservatory in Moscow, and in subsequent decades a vast network of RMS branches opened up across the Russian Empire, extending from Helsinki to Tbilisi, and from Kiev to Vladivostok.

Rubinstein’s institutions were ultimately immensely successful, but they were met with resistance during their formative period in the 1860s, particularly from Mily Balakirev and his associates. The Balakirev circle accused Rubinstein of subjecting Russian musical culture to pedantic German routine at the Conservatory and took issue with his supposedly conservative programming at the RMS concerts.Footnote 2 Not only did they wage a protracted war against Rubinstein’s institutions in the press, but they also created an alternative to them in the Free Music School, which trained amateur performers and hosted an annual concert series. Yet the Balakirev circle’s opposition was short-lived and largely withered away by the early 1870s, just as the circle itself disintegrated as a cohesive artistic community. By 1872, the FMS was bankrupt, Balakirev had become a recluse, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov – Balakirev’s most successful student – had accepted a position at the Conservatory. In subsequent decades, only fringe voices made objections to the role of the Conservatory and RMS in Russian musical life, and this affirmative view has only strengthened in the twentieth century.Footnote 3

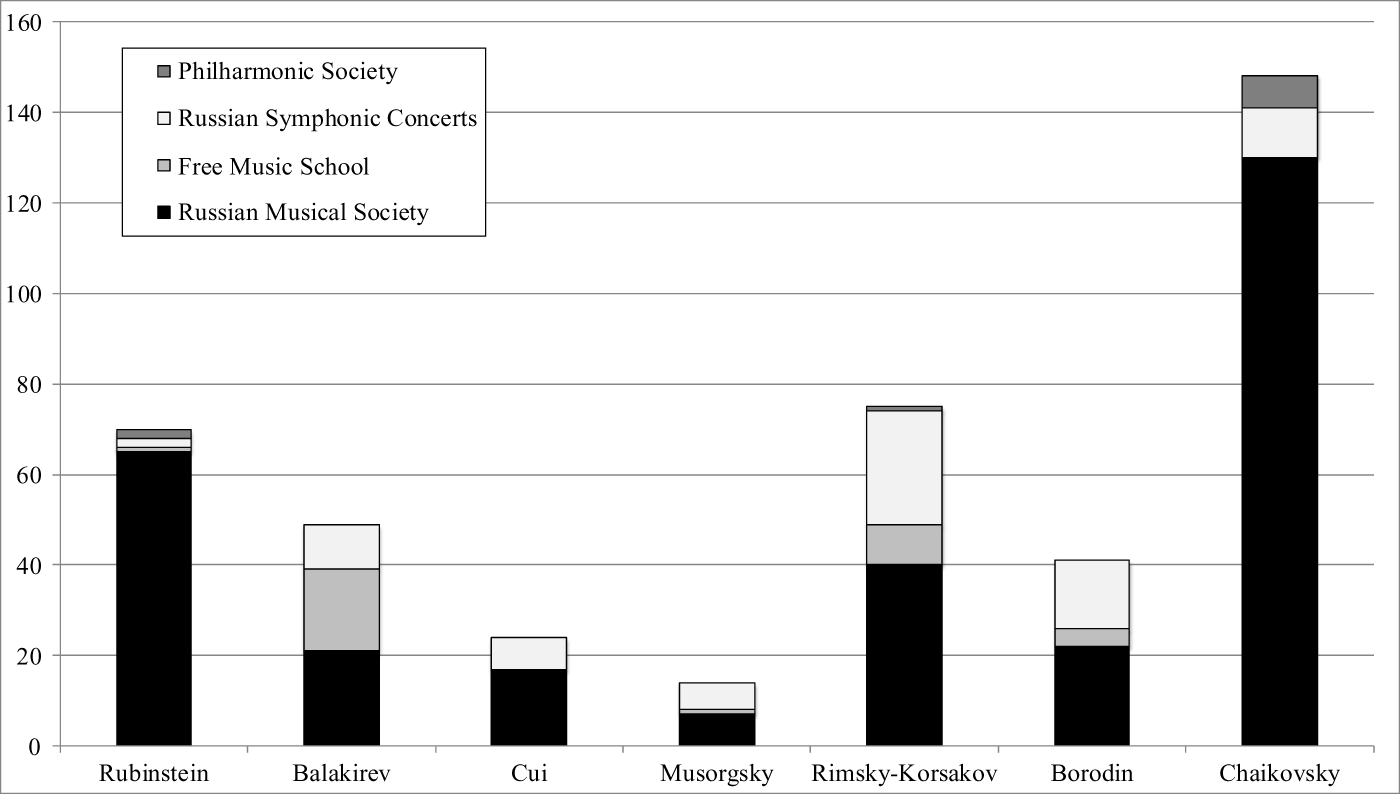

Throughout the nineteenth century, Rubinstein was also a much more successful composer than the Balakirev circle. His Demon (1871) quickly became one of the most popular operas in Russia and achieved more performances than all of the Balakirev circle operas combined before the end of the century.Footnote 4 In the realm of instrumental music, his orchestral works were performed more frequently at major Russian concert series than those of any Balakirev circle composers save for Rimsky-Korsakov (see Figure 1).Footnote 5 Whereas the Balakirev circle members struggled to get any performances outside of Russia until the 1890s, Rubinstein’s works were also mainstays across European stages and concert halls.Footnote 6

Figure 1. Performances of selected orchestral compositions by Rubinstein, the Balakirev circle members and Tchaikovsky at major concert series in Saint Petersburg and Moscow between 1859 and 1899.

It is the Balakirev circle’s compositions, however, that occupy centre stage in modern histories of Russian music, whereas Rubinstein’s works are typically mentioned in passing only. Broadly, the side-lining of Rubinstein’s music has been justified by historians in two ways: because they saw it as lacking nationalist qualities, and because they perceived it as aesthetically conservative. For much of the twentieth century, these criteria were paramount for histories of Russian nineteenth-century music, the Balakirev circle members were positioned as the stars of these histories, and Rubinstein was but a foil to these stars.Footnote 7 Whereas Balakirev and his associates thus developed a national style, pursued realism in opera and focused on programme music in instrumental genres, Rubinstein supposedly composed in a pan-European idiom and rejected musical innovations past early Romanticism, continuing to write number operas and non-programmatic instrumental works.

This conventional portrayal of Rubinstein’s music does not quite hold up as one becomes more familiar with his immense body of work. Instead, one encounters a dizzying diversity of genres and styles, ranging from operatic imitations of Glinka (Dmitry Donskoy) and the Balakirev circle (The Merchant Kalashnikov) to grand opéra (Nero), and from classicist symphonies (No. 1 and 3) to instrumental works written on detailed literary programmes (Don Quixote and Lenore) in quintessentially Lisztian fashion. Many of these works were widely performed in Russia throughout the nineteenth century, and they were also studied, appreciated and imitated by native composers, including Tchaikovsky and even the Balakirev circle members themselves (though they rarely admitted as much).Footnote 8 The gap between the historical record and the perception of Rubinstein’s music in most modern histories is vast.

This article traces the origins and construction of Rubinstein’s modern image as a composer. Recent investigations have revealed that this image is a caricature, perpetuated by the Balakirev circle and subsequently absorbed into modern discourse.Footnote 9 That is indeed the case, and the origins of this caricature can be traced to the Balakirev circle’s attacks on Rubinstein’s compositions in the early 1860s, as they competed with him for resources and the public’s attention on the Saint Petersburg concert scene. In the late 1860s, however, their opposition suddenly vanished, and they unfurled an entire campaign in the press to support Rubinstein’s recently completed symphonic works, Ivan IV and Don Quixote. The initial impetus for this rapprochement appears to have been the deteriorating financial situation at the FMS, with Balakirev turning to Rubinstein for support as a last resort. Quickly, however, this marriage of convenience developed into a sincerer relationship, culminating in a brief period in 1871, during which the Balakirev circle and Rubinstein formed something akin to an artistic community. While this community did not last, most of the Balakirev circle members maintained friendly relationships with Rubinstein for the remainder of their lives. It was primarily through the efforts of Vladimir Stasov, starting in the 1880s, that this rapprochement was erased from history and replaced with the image of Rubinstein as the enemy of the Balakirev circle and all progressive national music.

Reception of the ‘Ocean’ Symphony and Faust in the Early 1860s

Rubinstein’s image as a cosmopolitan conservative composer can be traced back to the writings of the Balakirev circle in the early 1860s.Footnote 10 As part of their opposition to Rubinstein’s institutions, Balakirev’s associates waged a protracted press campaign against his compositions, and held them up as cautionary examples of the dangers of German routine being forced onto Russian musicians at the Conservatory. In private correspondence, the circle’s attitude toward Rubinstein’s music was more nuanced, particularly in the early years of the decade, and included a qualified appreciation of works such as the ‘Ocean’ Symphony and the Second Piano Concerto.Footnote 11 In public, however, the circle’s judgments were unfailingly withering, accusing Rubinstein of uninspired replication of archaic compositional forms and techniques.Footnote 12 It did not matter whether the work at hand was the relatively conventional four-movement ‘Ocean’ symphony or the formally ambiguous Faust symphonic poem, the Balakirev circle’s published reviews condemned them all the same.

After its premiere in 1852, the ‘Ocean’ Symphony quickly became one of Rubinstein’s most popular compositions and attracted the praise of critics across the continent, including August Wilhelm Ambros and Eduard Hanslick.Footnote 13 To some extent, the praise was elicited by the elegance of the Symphony’s formal construction, seemingly modelled on the more adventurous works of Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Schumann.Footnote 14 Thus the exposition of the first movement, set up in essentially Romantic fashion as two characteristic tableaux,Footnote 15 moves from C major to the somewhat unusual E minor.Footnote 16 Even more surprisingly, the secondary theme returns in C minor in the recapitulation, thus precluding the customary modal shift to major. As if to compensate for the absence of the expected G major secondary tonality in the exposition, much of the development is taken up by a tonally stable juxtaposition of the primary and secondary themes in G major. The expected resolution of the recapitulation in C major is in turn delayed until the coda, which functions as a kind of second, telescoped recapitulation, where the primary and secondary themes succeed each other in the tonic major. The G major development and C major coda thus compensate for the tonal deviations of the secondary theme in the exposition and recapitulation, respectively, and substantially depart from their conventional functional roles in the process.

It was, however, the programmatic aspects of the symphony that drew particular attention from critics, many of whom went to great lengths to describe the impressions elicited by each movement.Footnote 17 Since Rubinstein provided no written programme, these interpretations varied substantially (some recurring themes notwithstanding, particularly the conception of the second and third movements as depictions of the calm sea and a sailors’ dance). Some critics wrote of the naturalistic qualities of the symphony, while others were more concerned with its poetic and ideational content. Some spoke about the work as a whole, while others described individual movements. One reviewer of a performance in Königsberg relayed the detailed programme of the symphony supposedly told to him by Rubinstein himself, while the Russian cartoonist Nikolai Ievlev lampooned the symphony’s perceived naturalism on the pages of the satirical journal The Spark (Figure 2). What all of these writers had in common, however, was that they took up Rubinstein’s implicit offer to interpret the symphony programmatically, and because of this they viewed him as decidedly aligned with progressive aesthetic currents of the time.

Figure 2. Nikolai Ievlev’s caricature of an audience after a performance of the ‘Ocean’ Symphony. Reproduced from Iskra 37 (1865): 500.

Compared to all of these accounts, the Balakirev circle’s public appraisal of the ‘Ocean’ is remarkable for its unqualified dismissal of the symphony as unoriginal and outdated. This appraisal, published in the Saint-Petersburg Times on 8 February 1869, was penned by Borodin, who temporarily stood in for Cui as the official spokesman of the circle.Footnote 18 After positing that the ‘Ocean’ consists of a ‘repetition of platitudes from Mendelssohnian routine’, Borodin focused his attention on the symphony’s lack of clearly articulated programmaticism, caused by the conventionality of its musical forms:

The symphony aims to present a musical depiction of the ocean. Why is there then a conventional division of the symphony into four parts? What relation does each of these parts have to the portrayal of the ocean? What does the Adagio mean that serves as the introduction to the finale, etc.? All of this remains unclear: no programme is attached to the symphony, and the music itself is not sufficiently characteristic. One simply hears here some sort of typical symphony, constructed according to the conventional symphonic form.Footnote 19

Borodin’s assessment of the ‘Ocean’ was at odds with the views of other nineteenth-century critics, but it was nominally consistent with the Balakirev’s circle publicly avowed aesthetic ideals in the late 1860s, which emphasized the replacement of conventional forms with ad hoc ones governed by extramusical poetic or representational goals.Footnote 20 Within this value system, the orchestral compositions of Liszt and Berlioz received the highest marks, while the works of Mendelssohn and Rubinstein were portrayed as pedantic replications of archaic compositional formulas. For a symphonic work to be satisfactory in the 1860s, Borodin’s review implied, it had to be a symphonic poem in the Lisztian vein.

Given Borodin’s stated expectations for a successful work of symphonic music, one would have expected the Balakirev circle to have shown more appreciation for Rubinstein’s Faust, premiered in Saint Petersburg in 1865. Almost certainly inspired by Liszt’s symphony on the same topic,Footnote 21 Rubinstein’s single-movement Faust is formally more unusual than the opening movement of the ‘Ocean’.Footnote 22 The composition seems to begin in line with sonata form conventions, but the supposed exposition in B flat major gradually becomes tonally unmoored and leads not only to a series of developmental sections based on earlier material, but also to static episodes during which entirely new material is introduced, including a chorale and a woodwind cantilena. Eventually, we arrive at what could be an off-tonic recapitulation in F minor, but it quickly gives way to yet another extended development section that includes yet another episode with a new cantilena.Footnote 23 When the themes from the slow introduction return in altered shape (tritones instead of perfect fifths) to conclude the work, we have heard little resembling a satisfactory recapitulation, either thematically or tonally.

The formal liberties of Faust, seemingly in service of its poetic subject, brought Rubinstein into greater proximity with the Balakirev circle’s stated aesthetic of instrumental music than any of his earlier works. Indeed, if we are to believe the reception of Faust in the years following its premiere, Rubinstein achieved having listeners interpret the composition by reference to the Faust legend. For example, the German critic Louis Köhler understood the work’s formal perturbations as depicting the vacillations of Faust himself, who ‘fails to achieve a final conciliation with himself and with existence’.Footnote 24 Feofil Tolstoy, writing in Saint Petersburg, suggested that Rubinstein ‘left the drama aside, and took Faust merely as a prototype of perpetually unsatisfied curiosity, dying under the burden of hopeless sadness and despair’.Footnote 25 Even Hermann Laroche, usually reluctant to interpret compositions programmatically, acknowledged that Faust ‘successfully conveys the overarching mood of the initial scenes of Goethe’s poem’.Footnote 26 Cui’s review of the Saint Petersburg premiere of Faust in 1865, however, is nearly indistinguishable from Borodin’s assessment of the ‘Ocean’. After acknowledging the poetic intentions indicated by the composition’s title, Cui proceeded to declare Faust a failure as a work of programme music, and concluded that it is ‘in no way different from Rubinstein’s countless other works, which are marked by a poverty of ideas and content, excessive length, and formal routine’.Footnote 27

Cui and Borodin’s assertions regarding Rubinstein’s antiquated forms and unsatisfactory programmaticism are thus neither representative of broader contemporary reception patterns, nor particularly sensitive to the nature of the works in question. The fact that the ‘Ocean’ was widely regarded as a successful work of programme music made little difference to them, as did the fact that the poetic subject and formal design of Faust placed it in proximity with the musical ideals of the New German School. Since the Balakirev circle members had proclaimed themselves champions of these ideals, and since they viewed Rubinstein as their enemy, they were unwilling to give him any credit for his attempts at writing programme music. It did not seem to matter that most of the circle’s own orchestral compositions at this time were either written in highly conventional forms (for example, Balakirev’s King Lear from 1862), entirely lacked programmatic paratext (for example, Borodin’s Symphony No. 1 from 1867), or both (for example, Rimsky-Korsakov’s Symphony No. 1 from 1865). It is true that Rimsky-Korsakov’s two most recent orchestral works, Sadko (1867) and Antar (1868), were based on custom formal layouts seemingly in service of poetic narratives, and we may perhaps be inclined to think that a year later Borodin was castigating Rubinstein on the grounds that his own circle had finally produced works that accorded with their stated ideology. The circle’s surprisingly positive reaction to Rubinstein’s Ivan IV in the autumn of 1869, however, only eight months after Borodin’s review of the ‘Ocean’, suggests that their musical preferences were neither as rigid as Borodin and Cui made them out to be earlier in the decade, nor driven solely by aesthetic considerations.

Ivan IV’s Success and the Balakirev Circle’s Change of Heart in 1869

The impetus and musical material for Rubinstein’s Ivan IV, completed in 1868, originated in two abandoned opera projects, both set during the reign of Ivan the Terrible.Footnote 28 By electing the infamous monarch as the subject of his symphonic picture, Rubinstein tapped into a highly topical theme in mid-nineteenth-century Russia. At least since Nikolai Karamzin’s History of the Russian State (1818), the reign and personality of Ivan IV had fascinated the native public, and by the 1860s he had become a favourite subject for artists in various media, resulting in paintings such as Vyacheslav Schwarz’s Ivan the Terrible by the Body of his Slain Son (1864), and literary works such as Alexey Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan the Terrible (1866). Whereas Western European audiences largely knew about the tsar only in vague terms, even a simple mention of his name elicited a rich web of associations for Russian listeners, and this goes a long way to explain why Ivan IV became one of Rubinstein’s few compositions that was more successful domestically than abroad. Not only did Russian critics readily bring their knowledge of Ivan’s life to their interpretations of the symphonic picture’s unfolding, but they also appreciated the stylized allusions to Russian folk and church music that Rubinstein had included throughout.

A comparison of German and Russian critics’ reactions to Ivan IV illustrates the role that familiarity with the historical subject played for nineteenth-century listeners. German writers were baffled by Rubinstein’s choice of programmatic title, left unexplained since there was no accompanying written programme. One critic described the confusion of a Munich audience about who the Ivan in question even was, and continued by asserting that the monarch is incapable of evoking the wealth of impressions conjured up by subjects such as Coriolan, Mazeppa and Prometheus.Footnote 29 Furthermore, German writers noted that although the symphonic picture’s formal layout was relatively ordinary, consisting of a readily recognizable sonata framed by a slow introduction and coda, they were unable to understand the significance of individual themes and episodes within this layout, or the relationship of these themes and episodes to each other. In one of the most extensive discussions of Ivan IV in the German press, Friedrich Stade was particularly perplexed by the meanings of the secondary theme in the exposition (Example 1a) and the brief episode in A flat major at the end of the development (Example 1b).Footnote 30 Both passages struck him as entirely lacking organic correspondence to the composition as a whole, yet he was at a loss with regard to their programmatic significance.

Example 1a. Ivan IV, secondary theme (bars 134–148).

Example 1b. Ivan IV, chant episode at the end of the development (bars 346–354).

The reactions of Russian critics to Ivan IV were in many ways the opposite to those of their German counterparts. Instead of doubting the suitability of the tsar as the subject of a programmatic composition, many Russian writers explicitly underscored that they deemed Ivan’s psychological complexity and tumultuous reign to be fertile ground for musical creations. They also readily projected their understanding of this complexity and tumultuousness onto Rubinstein’s composition, and interpreted its musical events as illustrations of Ivan’s contradictory personality. For example, Alexander Famintsyn understood Ivan IV as a depiction of the tsar’s multifaceted character, ‘at times gloomy, at times infuriated, at times sanctimonious’,Footnote 31 while another critic deemed it a portrayal of Ivan’s ‘abrupt shifts from wild ferociousness and anger to repentance and a downcast, melancholy emotional state’.Footnote 32 Two passages that Russian critics regularly cited as particularly characteristic and effective in depicting the tsar’s personality were precisely the two passages that had most bewildered German critics. The first of these, namely the secondary theme of the exposition (Example 1a), was commonly understood to be a folk song stylization,Footnote 33 while the second, namely the A flat major episode at the end of the development (Example 1b), was widely associated with liturgical music and Ivan’s sanctimoniousness. Whereas German writers could not make any sense of this developmental episode, the Russian critic Ivan Pryzhkov deemed it crucial to the portrayal of Ivan’s character, since, he asserted, ‘it is well-known, that it was in times of sanctimoniousness and prayer, that Ivan often gave his most horrific orders of execution’.Footnote 34

What is most remarkable about Ivan IV’s reception in Russia, however, is that in the autumn of 1869, the Balakirev circle joined in the adulations, seemingly forgetting the utter disregard that they had expressed for Rubinstein’s music only a few months earlier. On 16 October 1869, with the symphonic picture yet to be premiered in Saint Petersburg, a review of the recently published score appeared in the Saint-Petersburg Times. The Times was widely known as the press organ of the Balakirev circle, yet the signature below the review in question was not the customary ‘***’ used by Cui, nor the ‘Ъ’ and ‘Н’ used by Borodin and Rimsky-Korsakov, respectively, when they briefly stood in for Cui in the spring of 1869. Instead, the article was signed by a certain ‘В. Г. [V. G.]’, and behind this pseudonym was none other than Balakirev himself.Footnote 35 In what is his only known piece of published music criticism, Balakirev dedicated some space to discussions of works by Cui and Tchaikovsky, but the primary focus of the article was on Ivan IV, and what he had to say about the symphonic picture represented a remarkable about-face in the attitudes of his circle toward Rubinstein:

The musical picture in question is nothing else but a large overture, such as Litolff’s overture to the drama The Girondists, and differs from the latter only through its greater solidity of musical craft and a lesser brightness of colours. Rubinstein’s orchestration is far inferior to Litolff’s French orchestration – full of effects to excess. Rubinstein, however, far exceeds Litolff in terms of formal control and compositional technique in general. The composition itself has a number of places that are positively beautiful and powerful, such as the Poco piu mosso fugato in the introduction, the canonic imitation of a figure from the second theme on a C pedal at the end of the middle section, and the movement in thirds at the end of the Allegro on the F pedal in the violins. The conclusion of the overture is quite beautiful and dramatic. Given all that has been said, one listens to the composition with great interest, notwithstanding the mediocrity and routineness of the main themes. Among the shortcomings of the overture, one should also mention the inability of the author to imbue the work with Russian colour – something that he attempted, as it is apparent from the second theme of the Allegro, which is somewhat similar in its opening to Susanin’s phrase ‘Why speak of the wedding’. At the end of the middle section, the author seemingly wanted to depict a monastery (Lento, 4 cellos solo), but unfortunately, he resorted to same model as Mr. Nápravník in his church chorus in The Nizhny-Novogorodians, namely Bortnyansky. To depict Russian monasteries, moreover during the time of Ivan the Terrible, by way of music à la Bortnyansky is a crude blunder about which one should speak no further. Nonetheless, this composition should undeniably be counted among Mr. Rubinstein’s best works.Footnote 36

Most immediately striking in Balakirev’s review is the shift in tone compared to Borodin and Cui’s reviews of Faust and the ‘Ocean’. Whereas the earlier reviews were primarily rhetorical exercises, heavy on dogmatic assertions but light on concrete evidence, Balakirev had produced a detailed, thoughtful discussion of Rubinstein’s latest symphonic picture. Even more surprisingly, Balakirev’s verdict was remarkably positive, particularly given his notorious willingness to find faults even within those compositions that he idolized and held up as models for emulation.Footnote 37 Most significantly, however, his review signalled a larger reconfiguration of his circle’s stated aesthetic priorities, as well as of the status that they were prepared to grant Rubinstein as a composer.

One aspect of this reconfiguration was the abandonment of the reductive opposition of free programmaticism and pedantic formal conventionality that had been a hallmark of the circle’s criticism in earlier years. Given Borodin and Cui’s emphasis that the ‘Ocean’ and Faust failed as programme music because of their conventional form, one would have expected Balakirev to censure Ivan IV on the same grounds. Particularly compared to Faust, Ivan IV’s adherence to sonata norms is quite clear, notwithstanding minor departures, such as the absence of cadential closure in the exposition and recapitulation. Yet in his review, Balakirev not only placed little emphasis on the viability of Ivan IV’s programmaticism, but was clearly also not bothered by its ‘large overture’ form (that is, sonata with introduction and coda). Instead, he specifically praised Rubinstein’s handling of form, and deemed it superior to that of Litolff – a significant verdict given that Litolff’s Girondists and Symphonic Concertos were part of a limited group of works that Balakirev valued highly throughout his life.Footnote 38 Rubinstein’s reliance on established forms was no longer automatically equated with obsolete, conservatory-induced mechanicism, and neither were the contrapuntal compositional techniques employed throughout Ivan IV, such as the fugato in the introduction and the canonic imitation in the development. In earlier years, the Balakirev circle members often spoke disparagingly of such techniques,Footnote 39 yet these were precisely the passages that Balakirev singled out as personal highlights in his review.

In a reversal of earlier assertions by Borodin and Cui, Balakirev was now willing to acknowledge Rubinstein as a composer of merit. As the second half of his review indicates, however, he was yet unwilling to admit him into the pantheon of Russian composers. Balakirev left no doubt that his otherwise positive evaluation of Ivan IV had nothing to do with the Russian programmatic subject or with Rubinstein’s efforts to imbue the composition with national colour – efforts that Balakirev perceived to be a complete failure. Like many other Russian critics, Balakirev singled out the secondary theme and the choral episode as Rubinstein’s most obvious attempts to give the work national character, and he even identified their stylistic roots in Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar and Bortnyansky’s sacred music, respectively.Footnote 40 However, he dismissed these attempts as unsuitable for the task, without explanation in the case of the secondary theme, and because of apparent anachronism in the case of the choral episode.Footnote 41 Although Balakirev did not suggest more appropriate musical methods for signifying the reign of Ivan the Terrible, one can fathom that the alternatives he had in mind were chains of variational melodic restatements and modal harmonic writing – two techniques that had become calling cards of his circle’s instrumental aesthetic by the late 1860s.Footnote 42 Balakirev was willing to cede some ground to Rubinstein as a composer, but he was clearly not ready to abandon his self-appointed role as the ordained prophet of Russian national music.

Balakirev’s unexpected praise for Ivan IV was a major event in Russian musical discourse, notwithstanding the qualifications. Though his pseudonym may have veiled his precise identity, few readers of the Saint-Petersburg Times would have had doubts about the review’s factional allegiance, since the Times had served extensively as a journalistic venue for the Balakirev circle since 1864. Any remaining uncertainty regarding the circle’s fondness of Ivan IV was removed two weeks later, when Balakirev personally conducted the Saint Petersburg premiere of the work at a concert of the Free Music School, on 2 November 1869. This premiere was in turn followed by Cui’s review of the performance, in which he restated Balakirev’s points and concluded that ‘Mr. Rubinstein’s musical-characteristic picture is far better than anything that he has written up until now’.Footnote 43 Together, Balakirev and Cui’s reviews and the performance of Ivan IV at the FMS were clear signals to the Russian public that the circle’s former animosity toward Rubinstein’s music, on full display only eight months earlier in Borodin’s review of the ‘Ocean’, had given way to qualified approval. Judging by the reviews themselves, the catalysts for this approval were partially a relaxation of the circle’s earlier aesthetic dogmatism, and partially the musical qualities of the new composition, and there is good reason to believe that the circle members genuinely enjoyed listening to Ivan IV.Footnote 44 Yet a closer investigation of the circumstances in which this change of heart toward Rubinstein occurred suggests that there were also more pragmatic causes. In order to understand these causes, we need to consider in greater detail how the circle’s relationship with Rubinstein was shaped by the changing institutional landscape of the time.

Institutional Drivers of the Rapprochement between the Balakirev Circle and Rubinstein

During Rubinstein’s tenure as the head of the RMS and Conservatory, through the spring of 1867, the Balakirev circle treated him with unrestrained derision.Footnote 45 Not only did they consistently subject his compositions to withering reviews in the press (for example, Cui’s discussion of Faust), but they also persistently launched attacks on his programming choices at the RMS concerts, and on what they perceived to be the misguided premise of operating a conservatory on Russian soil.Footnote 46 The letters of the circle members attest to the fact that their hostile attitudes toward Rubinstein were not mere public posturing, since their correspondence is also littered with disdainful remarks about ‘Stupidstein’, the ‘German Musical Ministry’ (the RMS) and ‘the puddle’ (the ‘Ocean’ Symphony).Footnote 47 Balakirev himself had spoken favourably about some of Rubinstein’s compositions in the early years of the decade, but such displays of appreciation disappeared from his letters in later years, and were replaced by the same sorts of slurs that marked the writings of his associates.Footnote 48 It appears that Rubinstein did not reciprocate this hostility in any way, and instead repeatedly extended olive branches toward the Balakirev circle. Not only did he continuously include their compositions in his concerts, and even conducted premieres of works by Cui, Musorgsky and Apollon Gussakovsky, but he also attempted to involve Balakirev in the activities of the Conservatory, such as in organizational discussions and annual examinations of the students.Footnote 49 Such attempts at conciliation were, however, unconditionally rejected by Balakirev and his associates, and particularly after the commencement of the FMS concerts in 1862, they began to view Rubinstein as their main adversary, to be denigrated at every opportunity.

In the winter of 1867, when the circle learned of Rubinstein’s intention to resign from the RMS and Conservatory because of disputes with faculty, they erupted with Schadenfreude.Footnote 50 Not only were they elated about their rival’s bad fortune, but they also viewed Rubinstein’s resignation and subsequent departure from Russia as an opportunity to expand their own institutional clout in the local musical scene.Footnote 51 For some time, Cui and Stasov had been bombarding the press with reports of Balakirev’s achievements as a conductor, along with insinuations that he was overdue for a more prominent role.Footnote 52 Rubinstein’s departure eliminated a direct competitor, and made it more likely that Balakirev would be awarded another, more prestigious conducting position. At the time, Balakirev was particularly hoping to take over the symphonic concerts of the Imperial Theater Directorate, yet the summer of 1867 brought an entirely unexpected turn of events. After making it clear to the RMS directors that he would not be returning to Russia in the autumn, Rubinstein recommended Balakirev as his successor at the RMS.Footnote 53 The directors in turn convinced the Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna (the patron of the institution) to accept this proposal, and on 10 September 1867, Balakirev was officially instated as the next music director of the RMS.Footnote 54 Against all odds, the opposition between the RMS and FMS, which had shaped Saint Petersburg musical life for the past five years, suddenly ceased to exist, with Balakirev having become the musical director of both institutions.

The institutional realignments that took place in the summer of 1867 had little impact on the Balakirev circle’s hostile attitude toward Rubinstein. Notwithstanding the fact that Rubinstein had apparently helped Balakirev obtain the conducting post at the RMS, and the fact that he was no longer even residing in Russia, the circle continued to attack him in their published writings and correspondence.Footnote 55 In the autumn of 1868, when Rubinstein briefly came back to Saint Petersburg, they even speculated that he had returned to partake in a conspiracy to replace Balakirev again as the music director of the RMS.Footnote 56 Although plans to remove Balakirev from the RMS were indeed underway at that point in time, headed by Elena Pavlovna, there is no evidence that Rubinstein was in any way involved in them.Footnote 57 Quite the contrary, during his visit, Rubinstein initially made another attempt at conciliation by dedicating the ‘Russian Dance and Trepak’ from his National Dances, Op. 82 to Balakirev. In the end, however, he reconsidered the dedication, citing a concern that ‘Balakirev may decline this honour, since he and his party decidedly do not value me at all’.Footnote 58 Balakirev did conduct Rubinstein’s ‘Ocean’ during the fifth concert of the 1868–69 RMS season, but it was in response to this performance that Borodin published his withering review discussed above.Footnote 59 Throughout Balakirev’s tenure as the conductor of the RMS concerts, from 1867 to 1869, his circle’s attitude toward Rubinstein was thus effectively identical to their attitude in earlier years.

Everything changed in the spring of 1869, when Elena Pavlovna sent Balakirev notification of his dismissal from the RMS.Footnote 60 Balakirev was incensed by the dismissal, since he had lost the most conspicuous conducting position in Saint Petersburg. He had, however, retained leadership of the FMS concerts, as well as the press support of his associates, and with these means at his disposal he renewed his rivalry with the RMS. In order to make the FMS concerts competitive with those of the RMS, Balakirev expanded the FMS season from its usual one or two concerts to five, made noteworthy programming choices such as the Saint Petersburg premiere of Liszt’s Legend of Saint Elizabeth, and invited famous soloists, including Conservatory faculty as well as the director of the Moscow RMS branch, Rubinstein’s brother Nikolai. The invitation of such soloists was a particularly significant achievement for Balakirev, since it indicated to all of Saint Petersburg that the best musicians in Russia supported the FMS, notwithstanding their professional affiliations with its rival institution. Accordingly, such invitations constituted a symbolic victory over his former employer, and indeed, Elena Pavlovna was so incensed by Nikolai’s performance at an FMS concert that she refused to receive him when he subsequently attempted to make his obligatory appearance before her.Footnote 61

It was at the height of this arms race between the FMS and RMS that Balakirev decided to include Ivan IV in one of the FMS concerts. In a letter to Nikolai Rubinstein from 25 September 1869, Balakirev revealed his intensions for the 1869–70 season of the FMS.Footnote 62 He discussed at lengths the Conservatory faculty members that he was able to enlist as soloists for his concerts, and gleefully imagined the fury that these enlistings would elicit from Elena Pavlovna. He also begged Nikolai himself to perform at one of the concerts, and asserted that he was ‘willing to do anything’ for this to happen; seemingly in order to ingratiate himself, he announced that he decided to dedicate his Islamey to Nikolai. Finally, at the conclusion of the letter, Balakirev asked Nikolai to mail the orchestral parts for Ivan IV, which Nikolai had premiered in Moscow a few months earlier.Footnote 63 After receiving the parts, Balakirev scheduled Ivan IV to be performed in the second concert of the FMS season, on 2 November 1869, and prior to this performance, he penned his affirmative review in the Saint-Petersburg Times, fuelling audience anticipation for the concert.Footnote 64 Through the performance of Rubinstein’s symphonic picture, along with the media attention generated by his review and Cui’s follow-up after the concert, Balakirev thus achieved two goals at once in his competition with the RMS. Not only did he demonstrate to the rest of Saint Petersburg that the newest, most interesting music of the time was to be heard at the FMS concerts, but he also sent a clear signal that he had now joined forces with one of the most prominent musicians in Europe, and moreover the original founder of the RMS. The performance of Ivan IV was, in short, a major coup for Balakirev in his attempt to elevate the FMS above the RMS as the premier concert institution in Saint Petersburg.

Notwithstanding this public gesture of rapprochement with Rubinstein, Balakirev was apparently not yet ready for such rapprochement in private. In his letter to Tchaikovsky from 1 December 1869, Balakirev’s tone toward Rubinstein was still disdainful, and after acknowledging Rubinstein’s arrival in Saint Petersburg, he indicated that ‘of course, I will not go to see him’.Footnote 65 Over the course of the 1869–70 concert season, however, it gradually became clear that the FMS was not covering its costs, partially because it had engaged in a ticket price war with the RMS, and partially because its expenditures had skyrocketed due to the enlistment of famous soloists.Footnote 66 Already in November, Balakirev had complained about the financial situation to Tchaikovsky, and by the winter he was engaged in frantic efforts to secure additional funding sources. At one point, in a move that incurred the wrath even of Cui and Stasov, he went so far as to attempt to organize a special benefit concert featuring Adelina Patti and other stars of the Saint Petersburg Italian Opera troupe, who had been publicly attacked by the circle only months earlier for their perceived corruption of domestic audience tastes. As the financial situation of the FMS deteriorated, Balakirev also warmed up to Rubinstein, and on 22 December 1869, only three weeks after asserting that he categorically refused to have any contact with him, he wrote to Tchaikovsky again, informing him that ‘Anton Rubinstein came to visit me’.Footnote 67

By the autumn of 1870, the 1870–71 season of the FMS concerts was under threat of cancellation because of a lack of funding, and it is at this point that Balakirev’s attitude toward Rubinstein changed most dramatically. His letter to Nikolai Rubinstein from 3 September 1870 is a testament to this reversal of sentiment toward his former enemy:

Having arrived here, I heard that your brother was also here on his way to the Tver Governorate, and that the [Russian] Musical Society invited him to take part in their concerts, but the information regarding his response is contradictory: some say that he agreed, while others claim that he flat-out refused. Only you can tell me the truth in regard to this question, which interests me very much. I would very much like that he would also take part in my concerts, if that is only possible for him given his relationship with her highness the patron [Elena Pavlovna]. Accordingly, I ask for your advice. You probably have seen your brother and know the true state of things. I have inquired whether he will stop by here. They say that he will not be here before October, and that would be too late for me. My programme has to appear in the first half of this month, and it would do me an immense favour if you could respond as soon as possible. … If you find it best if I write to your brother myself, I would be happy to do so – just notify me of his address.Footnote 68

Balakirev’s letter was part of his attempt to get an even more impressive line-up of soloists for the 1870–71 FMS season than the one he had arranged for the previous one – in the same letter he had also asked Nikolai to help him engage Ferdinand Laub, while Nikolai himself had apparently already promised to take part. In his reply from early October, however, Nikolai rescinded his promise, implying that participation in FMS concerts would ‘compromise the standing of the Moscow Conservatory’ due to pressure from Elena Pavlovna.Footnote 69 Instead, he suggested that Balakirev should reach out to Anton himself, who was at the time residing in Saint Petersburg, surmising that ‘he will not refuse to replace me’.

Balakirev took Nikolai’s advice to see Anton, and reported about the result in letters to both Tchaikovsky and Nikolai, making the encounter seem like a friendly gathering:

[To Tchaikovsky] I have met Anton Rubinstein here, with whom we are not only beginning to talk, but also enter into arguments. He is a good fellow, and likeable, but I still have the same opinion of him as before.Footnote 70

[To Nikolai Rubinstein] I have not spoken a single word with your brother about the concerts, not because I have something against him (quite the opposite, we have seen each other not infrequently, and did not leave unpleasant impressions on each other), but for completely other reasons, which would have very much compromised him before the [Russian] Musical Society, from which it would be difficult for him to disengage given his [temporary] residence in Saint Petersburg.Footnote 71

In suggesting to Nikolai that he did not ask Anton to partake in the FMS concerts because he did not want to put him in a compromising position with the Saint Petersburg establishment, Balakirev was probably bluffing. Although he officially continued to plan the upcoming concert season through the rest of the calendar year, it was becoming clear already by the middle of October that the concerts would not be financially possible, and indeed the season never took place.Footnote 72 An unexpected outcome of Balakirev’s meetings with Rubinstein, however, was a complete rapprochement of the latter with Balakirev and his associates – a rapprochement that briefly resulted in regular private meetings and even something resembling an artistic association between them. Already during one of their first meetings, Rubinstein introduced Balakirev to his newly composed and unpremiered symphonic picture Don Quixote. A few days later, on 19 October 1870, Balakirev in turn played Don Quixote for his entire circle, save for Cui, at a gathering at Liudmila Shestakova’s house.Footnote 73 There is no record of the attendees’ reactions to this performance, but one can imagine that they were rather surprised, since Don Quixote turned out to be, in some ways, a quintessentially Lisztian symphonic poem.

Don Quixote and the Short-Lived Artistic Community of Rubinstein and the Balakirev Circle

Whereas Rubinstein had supplied no programme for Ivan IV, Faust and the ‘Ocean’ save their titles, he furnished Don Quixote with a detailed written programme derived from the Cervantes novel.Footnote 74 Inspired by chivalric romances, Don Quixote embarks on a series of adventures, including dispersing a flock of sheep whom he imagines to be monsters, imploring a village woman whom he perceives to be Dulcinea to accept his love, and freeing a group of convicts only for them to nearly beat him to death. In setting this programme, Rubinstein abandoned all allusions to sonata form and instead structured Don Quixote as a succession of episodes that reflect the progression of the literary plot. The extramusical significance of these episodes is clarified not only by their relative placement within the sequence of events, but also through a series of expressive techniques nowadays firmly associated with Liszt’s symphonic poems.Footnote 75 Like these symphonic poems, and unlike Rubinstein’s earlier compositions, Don Quixote is laden with general pauses, abrupt changes of meter and key, thematic transformations, unorthodox instrumentations, harmonic progressions by thirds (for example, bars 35–52), and musical topics (for example, a pastorale to represent the scene with the sheep). The cumulative effect of these techniques is a pronounced characterization of individual sections, allowing enculturated listeners to identify the extramusical meanings of musical events with little ambiguity. Indeed, across the many nineteenth-century reviews of Rubinstein’s symphonic picture, there was little disagreement about the identification of various narrative scenes in the music.Footnote 76

The responses to Don Quixote in Russia were overwhelmingly positive, with a number of writers remarking that the programmatic goals of the composition forced Rubinstein to be more inventive in his melodic writing, orchestration and harmonization than ever before.Footnote 77 Few voices, however, were as loud and persistent in their praise as Cui. Within a year of the Saint Petersburg premiere, on 21 February 1871, Cui published an entire three articles containing glowing assessments of Don Quixote. The first and most extensive of these articles also included an extended programmatic interpretation of the composition:

This is what things have come to these days: Mr. Rubinstein, this firm and reliable pillar of pure symphonic music, – even he has turned to programme music. … Don Quixote belongs to Mr. Rubinstein’s best compositions: it is full of interest, and demonstrates talent and a sense of humour. Don Quixote’s theme, in unison, somewhat in the Wagnerian style, successfully portrays his fantastic impulses, ignorant of all reality. The ferment and disarray of his thoughts is also depicted well. The slow and limping trot of the emaciated Rocinante, which precedes each episode, is excellent, comical, and at the same time musical. The pastorale of the sheep is very original and characteristic. The etude with the supposed Dulcinea is superb, and contains a very fortunate contrast between the coarse, flat and dull theme of the peasant women and their mockery of Don Quixote on the one hand, and his Wagnerian striving on the other. The scene with the convicts is weaker than the others. The death of the hero – his theme is shattered and pathetic, interrupted by timpani – elicits not only laughter toward the unfortunate knight, but also compassion.Footnote 78

The overt catalyst for Cui’s appreciation of Don Quixote was its detailed narrative programmaticism, and there is little reason to doubt that his enthusiasm was genuine. After all, his reviews came at what was arguably the crest of the Balakirev circle’s association with Lisztian radicalism, and Rubinstein’s latest work accorded to these principles more so than any of his earlier compositions. Just as in the case of Balakirev and Cui’s positive public assessments of Ivan IV, however, there appear to have been auxiliary motivations that also influenced Cui’s appraisal of Don Quixote. By January 1871, the occasional encounters between Rubinstein and Balakirev, initially originating in Balakirev’s desire to enhance the prestige of the FMS concerts, had grown into regular musical gatherings at which the entirety of the Balakirev circle was present. These meetings, focused on the demonstration and discussion of new compositions by the participants, largely resembled the meetings of the circle itself in earlier years, and in some ways, Rubinstein effectively became a member of their artistic community. The fervour with which Cui embraced Don Quixote in the press was thus similar to the partisan fervour with which he had supported the compositions of his associates throughout the 1860s.Footnote 79

The fragmentary evidence of Rubinstein’s encounters with the Balakirev circle during this time yields some insight into what their association entailed. The first verifiable joint meeting took place at Dmitry Stasov’s house on 23 January 1871, with the entirety of the circle in attendance; as one attendee recalled, there were heated debates on matters concerning Russian music, but unanimous delight when Rubinstein performed on the piano.Footnote 80 On 26 February, Balakirev conducted Rubinstein’s Piano Concerto No. 2, with the composer as soloist, at a concert in the Bolshoi Theater in Saint Petersburg.Footnote 81 On 3 March and 10 March, the first two and only meetings took place of an artistic club that Rubinstein had organized with the intention of bringing together Russian writers, visual artists and musicians. Balakirev was not only in attendance (as were probably other members of his circle), but was even elected to a leadership committee that was formed during one of these meetings.Footnote 82 On 17 April, Rubinstein wrote to Dmitry Stasov, inquiring when he would be able to attend a private performance of Alexander Dargomyzhsky’s Stone Guest (yet to be staged) that Stasov had promised him, citing a need to ‘have a thorough understanding of the musical state of Russia prior to his departure abroad for the summer.Footnote 83 This private performance took place on 23 April, and the next day Vladimir Stasov reported to Alexandra Molas that Rubinstein deemed the work a mere curiosity, inferior to Mozart’s Don Giovanni and unlikely to find popular success on the stage.Footnote 84 On 19 May, shortly prior to Rubinstein’s departure from Saint Petersburg, Vladimir Stasov wrote to Rimsky-Korsakov, inviting him to yet another evening of music making, asking him to bring sketches of his opera The Maid of Pskov, and expressing hope that Balakirev, Borodin and Rubinstein would be in attendance.Footnote 85

The Balakirev circle’s artistic alliance with Rubinstein in the spring of 1871 was merely the first step in a far-reaching factional realignment that took place in Russian musical life that year. By the summer it became clear that Rubinstein would not be returning to Saint Petersburg on a permanent basis in the near future. In the spring, there were rumours that he was about to be offered some sort of important post in Saint Petersburg, but no such offers came forth, and he eventually accepted a year-long position as the music director of the Gesellschaft für Musikfreunde in Vienna for the 1871–72 season.Footnote 86 At the same time, momentous shifts were underway at the RMS and Conservatory, initiated by the instatement of Mikhail Azanchevsky as the head of both institutions.Footnote 87 Azanchevsky’s reforms included a modernization of RMS programming, with its focus shifted further toward contemporary music and works by Russian composers, but his most radical move was to invite Rimsky-Korsakov, one of the Balakirev circle’s own, to teach composition and orchestration at the Conservatory.Footnote 88 Surprisingly, Rimsky-Korsakov’s associates did not object to the move, and he accepted the position in late July, after only brief deliberation. By the autumn of 1871, the opposition between the Balakirev circle and the Conservatory establishment, which had shaped Russian musical culture for much of the past decade, was suddenly a thing of the past.

Prior to relocating to Vienna in the autumn of 1871, Rubinstein briefly returned to Saint Petersburg, and initially his relationship with the Balakirev circle appeared to be just as amicable as earlier in the year. In a speech that he gave at the ninth anniversary of the foundation of the Conservatory, on 8 September 1871, Rubinstein singled out the circle members (along with Tchaikovsky and Laroche) as the ‘young composers who comprise our hope and – I boldly proclaim this – our glory and our musical future’.Footnote 89 Two days later, Rubinstein met with Musorgsky, and Musorgsky described this meeting with great warmth in a letter to Vladimir Stasov:

1. Yesterday I saw dear Rubin, and he is thirsting for a meeting as passionately as we do; 2. He is designating Wednesday for this deed; 3. He will arrive on Wednesday with a new opera, and this opera he will demonstrate to us, namely: general Bacchus [V. Stasov], Dimitrius Vasilyevich [D. Stasov], the admiralty [Rimsky-Korsakov], Kvey [Cui] and myself, the sinful one; 4. He named Balakirev and Borodin among the audience, but this will hardly come true; 5. He will sing his opera, and therefore has begged that no one should be there besides us. For this reason, we need to know where Rubin should go with his opera – to you or to Dmitry Vasil’evich – decide and let Rubin know (better in person); they say that he resides in the Hotel de France, and, one thinks, is at home in the morning, until 11 or noon, or so. Rubin was passionate to a delight – a lively and excellent artist.Footnote 90

For all of Musorgsky’s anticipation and enthusiasm, however, Rubinstein’s demonstration of Demon, which took place on 15 September 1871, marked the conclusion of the brief period of artistic association between the two factions. In some ways, Demon should have been as welcomed by the attendees as they had welcomed Don Quixote a few months earlier, since Rubinstein’s new opera exhibited qualities that were highly valued by the circle. Not only was it Rubinstein’s first opera in Russian since the early 1850s, but it was also based on a poem by a canonic Russian author, dealing with supernatural forces, and set in the Caucasus. Moreover, Rubinstein depicted this setting through substantial attention to local colour, deploying Georgian melodies, and even using the circle’s own orientalist trademark technique for portraying languor, namely the 5–#5–6–♭6–5 melodic pattern in an inner voice over a static bass.Footnote 91 Even the circle’s desire for the usage of original literary texts à la Dargomyzhsky’s Stone Guest was partially satisfied by the third act of Demon, much of which is based directly on Mikhail Lermontov’s poem. Save for a few instrumental scenes, however, Rubinstein’s demonstration left the attendees cold, and it was only after he performed works by other composers that ‘the general mood changed and became joyous and solemn’.Footnote 92 Notwithstanding this positive conclusion to the evening, Rubinstein was apparently so distraught by the negative reception of his new opera that he became ill for multiple days. This gathering was the last time that the Balakirev circle and Rubinstein ever met in private to perform their own compositions for each other, and in subsequent years their contact was more limited.

One can hypothesize many reasons for why the artistic rapprochement between Rubinstein and the Balakirev circle fizzled out as quickly as it did. For one, by 1871, the circle as such was already dissolving, and as the individual members embarked on their individual artistic paths, their meetings became less frequent and eventually ceased altogether.Footnote 93 Moreover, after Rimsky-Korsakov joined the Conservatory staff, there was no longer the need for a strategic alliance to oppose the Saint Petersburg musical establishment headed by Elena Pavlovna.Footnote 94 Perhaps Rubinstein had also made the circle members uncomfortable with his composition of Demon, since the opera could have been perceived as an encroachment on their territory, and since there were only limited resources for the staging of native operas in Russia.Footnote 95 It could also be that Rubinstein was too frustrated by the circle’s reception of Demon, as well as by the frequent arguments that seem to have taken place during the meetings, and abandoned the hope of ever establishing any sort of functional artistic collaboration with the circle. Finally, it is also possible that the circle members simply genuinely disliked most of Rubinstein’s compositional pursuits starting with Demon, and thus did not feel that an artistic association would be a productive pursuit.Footnote 96

Whatever the reasons may have been that caused Rubinstein and the Balakirev circle members to stop presenting their compositions to each other for critique, their joint meetings continued throughout the 1870s, albeit less frequently and in a different format. In this new format, Rubinstein was exclusively a performer, predominantly of canonic repertory by deceased composers, and effectively treated the others to private performances, which they in turn greeted with great enthusiasm. One such meeting took place in May 1874 at Vladimir Stasov’s house, attended by the entire former circle, save for Balakirev, as well as by Ivan Turgenev and a number of others. The response to Rubinstein’s performance of works by Beethoven, Chopin and Schumann, was, according to the recollections of one attendee, as relayed by Mikhail Goldstein, overwhelming:

when Rubinstein finished, we all ran to him and began to kiss his hands, knees, head … There were all kinds of exclamations – ‘devil’, ‘god’, ‘wizard’. Vladimir Stasov kept shaking Borodin while repeating: ‘Look, Anton Grigoryevich, Alexander Porfiryevich has gone completely limp!’ Anton Grigoryevich looked in the direction where Borodin was sitting, and smiled, seeing his face wet with tears. Borodin kept smiling and repeating his favourite utterance: ‘What the hell is this!’ From the corner one could hear the enthusiastic tenor of Rimsky-Korsakov, who was waving around his long arms, having at this point completely forgotten about his glasses, which had slid down to the end of his nose. … We all stood up from our places. There were no words. I do not even remember whether we said farewell to Rubinstein or to the hosts. No one touched the dinner.Footnote 97

Such private performances continued occasionally into the 1870s, ceasing altogether only by the early 1880s,Footnote 98 and most of the former circle members preserved a reverent attitude toward Rubinstein’s pianism to the end of their lives. Many of them also maintained respectful personal relationships with Rubinstein, and had mostly positive things to say about him in their letters and memoirs. One notable exception was Vladimir Stasov, and it was his changing attitudes toward Rubinstein in later years, inclusive of a desire to forget the rapprochement of the early 1870s, that ended up shaping modern histories of Russian music.

Vladimir Stasov and the Erasure of Rubinstein from Histories of Russian Music

The events described in the preceding pages marked a major junction in nineteenth-century Russian music history. The artistic rapprochement between Rubinstein and the Balakirev circle signified the resolution of a conflict that had defined Russian music in the 1860s, and although this rapprochement was short-lived, most of the participants remained on amicable terms with each other for the remainder of their lives. For example, Musorgsky recalled Rubinstein’s name with warmth in the autobiography that he wrote shortly before his death,Footnote 99 Rimsky-Korsakov worked with him extensively when Rubinstein became head of the Conservatory again from 1887 to 1891,Footnote 100 and Cui maintained friendly personal communication with Rubinstein and even dedicated compositions to him.Footnote 101 In turn, Rubinstein not only reciprocated the collegiality of the former circle members, but also actively promoted their music, such as when he introduced Viennese and Parisian audiences to Rimsky-Korsakov’s compositions, in 1872 and 1882, respectively.Footnote 102 Moreover, although the Balakirev circle’s press campaign in support of Ivan IV and Don Quixote may have been partially driven by pragmatic considerations, Rimsky-Korsakov and Cui openly expressed their admiration for these works until their deaths. One of the most telling illustrations of such admiration can be found in Cui’s La musique en Russie (1880), written in order to indoctrinate French audiences into the Balakirev circle’s conception of Russian music.Footnote 103 In his account, Cui doubted the longevity of much of Rubinstein’s music, but he excepted Ivan IV and Don Quixote from this judgment, asserted that ‘the Russian national genius has left its imprint quite clearly’ on Ivan IV, described Don Quixote as ‘full of verve and wit’, and concluded that both compositions ‘belong without question to the Russian school’.Footnote 104

And yet, Rubinstein’s programmatic compositions and his association with the Balakirev circle in the early 1870s are largely absent from modern histories of Russian music. For example, neither of the two most recent Western surveys of the subject as much as allude to the rapprochement between Rubinstein and the circle, and although one of them does briefly mention Ivan IV, it describes it by way of 1860s Balakirev circle clichés, as the conservative foil to Balakirev’s progressive King Lear.Footnote 105 In a few instances, particularly in scholarship focused specifically on Rubinstein, references appear either to some of the encounters between Rubinstein and the circle in the early 1870s, or to the programmatic orchestral works, but almost invariably, these references are fragmentary and lacking context. Even a specialized study of the relationship between the circle and Rubinstein makes no mention of the transformation of this relationship in the wake of Balakirev’s dismissal from the RMS in 1869,Footnote 106 while another recent article on the subject mentions this transformation only in passing, and explains it to be the result of Rubinstein’s desire ‘to rescue the common cause of Russian music’.Footnote 107 Mentions of Ivan IV and Don Quixote are similarly rare in the literature, and often contain confounding assertions that are difficult to reconcile with the narrative presented above: one recent publication thus refers to Ivan IV as a ‘concession to the aesthetics of the Russian nationalists’,Footnote 108 while another states that it would be misguided to speak of Rubinstein’s turn toward the symphonic poem in the late 1860s.Footnote 109 Such a substantial gap between conceptions of Rubinstein’s role in Russian music history at the end of the nineteenth century on the one hand, and at the end of the twentieth on the other inevitably begs the question as to what happened to Rubinstein’s status over the course of this century. While the explanation is undoubtedly multifaceted, it appears that the erasure of Rubinstein from modern histories is in many ways the result of efforts by Vladimir Stasov starting in the 1880s.Footnote 110

Stasov’s attitude toward Rubinstein in later years makes for a remarkable case study in duplicitousness, selective memory and desire to shape the writing of history. More so than any other of Balakirev’s associates, Stasov maintained extensive friendly contact with Rubinstein throughout the 1870s,Footnote 111 and as late as 1882 the two of them scheduled meetings for joint music making.Footnote 112 Such contact subsequently become more rare, but Stasov continued to visit Rubinstein with some regularity until the latter’s death in 1894, and overtly, the atmosphere between them appears to have been consistently friendly and polite.Footnote 113 Behind Rubinstein’s back, however, Stasov soon reverted to peddling the image of Rubinstein as the conservative cosmopolitan enemy of progressive national music that the Balakirev circle had conceived in the early 1860s.Footnote 114 In some instances, this entailed subjecting Rubinstein to duplicitous inquisitions during their meetings, where everything from Rubinstein’s German lackey to the stack of Russian opera scores on his piano was interpreted by Stasov as a sign of Rubinstein’s hatred for everything Russian, and subsequently reported on to anyone willing to listen.Footnote 115 In other instances, this entailed attacking his former associates for their associations with Rubinstein, such as when he implored for Rimsky-Korsakov not to take up Rubinstein’s offer to conduct the RMS concerts for the 1887–88 season. Instead, Stasov suggested with characteristically virulent xenophobia and anti-Semitism that Rimsky-Korsakov should let ‘Siecke, Goldstein, and all the kike and German trash participate’ in Rubinstein’s ventures.Footnote 116

Most significantly though, Stasov’s efforts to portray Rubinstein as the antithesis of everything Russian manifested themselves in his writings on music history, as well as in his efforts to influence the work of other historians. Briefly summarized, Stasov’s conception of music history entailed a divide between non-national composers who subscribed to pedantic professional musical training on the one hand (for example, Rubinstein and Tchaikovsky), and national composers whose music developed independently from European traditions and customs on the other (for example, Glinka and the Balakirev circle).Footnote 117 All evidence that nuanced or contradicted this conception was either swept aside with panache, or ignored altogether, and accordingly Stasov was unwilling to admit that Rubinstein had written compositions of value (aside from those that he perceived as written in the Balakirev circle’s style, such as the oriental dances in Demon), or especially the fact that Rubinstein had been effectively aligned with the Balakirev circle in the early 1870s.Footnote 118 Instead, the role that Stasov accorded to Rubinstein in his ample writings on music history was as the initiator of the pernicious Conservatory on Russian soil, and as a third-rate conservative composer who rejected all attempts at musical nationalism.

Stasov did not merely publicize this image of Rubinstein, but also made a great effort to manage the dissemination of information that could support or discredit it.Footnote 119 One particularly vivid illustration of this effort can be found in his response to Mikhail Goldstein’s description of Rubinstein’s meeting with the former Balakirev circle members in 1874.Footnote 120 This description, quoted above, was published shortly after Rubinstein’s death, and depicts in detail the friendliness, familiarity and adoration with which the circle members treated Rubinstein. This portrayal obviously squared poorly with Stasov’s thesis that Rubinstein was the eternal enemy of Russian national composers, and within seven days, Stasov responded to the article with his own version of the events. He began by exposing Goldstein’s identity (Goldstein had used a pseudonym for the article), superciliously noted that Goldstein was merely relaying someone else’s observations, and asserted that the account contained ‘certain infidelities’ that ‘substantially alter the character of that which really happened’.Footnote 121 The self-acknowledged purpose of Stasov’s response was to make sure that no one got the wrong impression about ‘the artistic relationships between Rubinstein and the ‘New Russian School’ during that time’. His own description of this relationship is a remarkable case study in selective memory and distortion of evidence:

A. G. Rubinstein sometimes visited my brother Dmitry and myself throughout the 60s and 70s, and in these instances always – in his own words, ‘with great pleasure’ – played for multiple hours straight many of the greatest creations by Beethoven, Chopin and Schumann, sometimes even Franz Schubert, so beloved both by himself and by all of us, ardent admirers of his truly genius playing. These listeners were, in those times, our entire former musical company: M. A. Balakirev, C. A. Cui, M. P. Musorgsky, N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov, A. P. Borodin. … This time around the reasons for our meeting were special. Firstly, at that point we had not heard Rubinstein amongst us for a while now. Since leaving his post as the director of the Conservatory in the beginning of 1867 and his departure abroad, he rarely visited Saint Petersburg for six or seven years, and even when he did visit, it was only briefly, merely for one, sometimes for two concerts; then he almost always immediately departed, so that we could not get him to perform for us.

Having been confronted with an account of Rubinstein’s private performances for the Balakirev circle, Stasov could hardly deny it, since many others were present at these performances. Accordingly, he instead resorted to minimizing the potential disruptive effects that this account could have on his own historical narrative. The way in which he achieved this was by decoupling Rubinstein’s performances for the Balakirev circle from the charged institutional and artistic context in which they originated in the autumn of 1869. Instead of being the by-product of an artistic collaboration that developed as an indirect result of Balakirev’s dismissal from the RMS in 1869, Rubinstein’s performances became occasional events that mostly took place before 1867, and moreover never extended beyond the canonic piano repertoire. The enthusiasm with which the Balakirev circle greeted Ivan IV and Don Quixote was now forgotten, as were the regular meetings in the winter of 1871 at which all of the participants would present their works-in-progress to each other. Instead, the circle members became opportunistic consumers of world-class piano recitals in the convenience of Stasov’s home.

Stasov’s efforts to discredit Rubinstein and to erase the events of the early 1870s from history went further, since he also repeatedly attempted to groom younger historians into rehearsing his narrative. For example, already before Rubinstein’s death, Stasov began writing letters to Nikolai Findeizen, the editor of the popular Russian Musical Newspaper, in which he insisted that Findeizen should be as critical as possible toward Rubinstein and the Conservatory.Footnote 122 Findeizen brushed off Stasov’s concerns as imaginary ones,Footnote 123 but other historians were not as independent-minded as he was. A particularly successful target of Stasov’s indoctrination was the Englishwoman Rosa Newmarch, whose ample publications on Russian nineteenth-century music ended up being a major carrier of Stasov’s prejudices into Western twentieth-century discourse, thus propagating his artificial divide between Rubinstein and ‘truly Russian’ composers.Footnote 124

Nevertheless, for decades, Stasov’s perspective remained merely one of many. For example, in 1929, the reputation of Rubinstein was still such that Boris Asafyev openly acknowledged the greatness of Rubinstein’s persona and his role in Russian music history.Footnote 125 It was only in the wake of Stalinism and the cultural doctrine of Andrei Zhdanov that Stasov’s views on Russian music history became canonized in the Soviet Union. In the case of Rubinstein, this meant begrudgingly acknowledging him as the founder of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, but largely ignoring his compositions and portraying them as the musical foil to the aesthetic of the Balakirev circle. The two major Soviet publications on Rubinstein after Stalin’s death, namely Lev Barenboim’s two-volume monograph and the three-volume collected writings of Rubinstein largely follow this model. The relative omission of Rubinstein’s music from Soviet historiography in turn further reinforced the omission of them that was already underway in the West since the early twentieth century, particularly since Western scholars were largely reliant on Soviet editions of primary sources, which were carefully culled to validate the Stasovian worldview.Footnote 126 The ultimate outcome of this process was that toward the end of the twentieth century, prevalent conceptions of Rubinstein’s compositions and his relationship with the Balakirev circle were often analogous to the views that Stasov expressed on the matters a century earlier, in his summative work The Art of the Nineteenth-Century (1901). According to this conception, Rubinstein was a cosmopolitan conservative, and locked in a perpetual battle with progressive Russian nationalist composers.

In 1868, Laroche had hypothesized that Rubinstein would have a difficult time achieving lasting fame as a composer because of his reluctance to engage in self-promotion.Footnote 127 Laroche turned out to be partially wrong, since during his lifetime Rubinstein enjoyed a success that was matched by few of his contemporaries. At the same time, Laroche was also partially right, since Rubinstein’s popularity turned out to be ephemeral, not least because he did nothing to counter Stasov’s attacks on him in the press. Even when he did publish three books at the end of his life, they barely so much as even mentioned his own compositions, or his relationship with the Balakirev circle. Only in a few instances did Rubinstein let this mask of dispassion slip briefly, to reveal his disappointment, frustration and fear regarding his role in music history. Toward the end of his autobiography of 1889, otherwise largely devoid of self-reflection, he briefly stopped his narration to wonder out loud about the way in which Stasov had marginalized him in the Russian musical world: ‘I wonder, how will this all end? It must resolve somehow. A confluence? This confluence will be strange. They do not want to know me at all, and consider me neither a Russian, nor a composer’.Footnote 128

Kirill Zikanov’s research on nineteenth-century orchestral music has been published in the Journal of the Royal Musical Association, Music and Letters and 19th-Century Music.