Prolonged labour is associated with poor pregnancy outcomes with high levels of both maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. Obstructed labour can lead to uterine rupture, postpartum haemorrhage, sepsis and obstetric fistulae, complications which tend to be seen more commonly in the developing world where reliable healthcare provision is less available. In the developed world catastrophic results from these complications are rare but the caesarean section (CS) rate has been steadily increasing over the last few decades and CS itself is not without risk of maternal morbidity and mortality especially when performed as an emergency [Reference Bewley and Cockburn1, Reference Villar, Carroli and Zavaleta2]. At least one-third of all CS are performed for dystocia and over two-thirds of women who have a CS in their first labour request an elective CS in a subsequent pregnancy [Reference Thomas and Paranjothy3]. Caesarean delivery can also lead to problems in future pregnancies including Caesarean scar pregnancy, uterine rupture and placenta accreta spectrum disorder [Reference Hemminki and Merilainen4], complications which are now included in the preoperative consent taking.

The poor maternal and fetal outcomes due to prolonged labour and need for CS for dystocia and, by consequence, repeat CS for previous CS may be reduced by expeditious management of poor progress in all stages of labour, especially early in the first. This chapter discusses some of the physiological events of the first stage of labour, the way in which labour progress is measured, and interventions which may be instituted when progress in the first stage of labour is suboptimal. Care during labour should be aimed towards achieving the best possible clinical outcome for both the woman and baby [5].

Normal Labour

The first stage of labour is defined as the period between onset of active labour and full dilatation. Active labour starts with regular, painful uterine contractions, with or without a ‘show’, which are associated with progressive cervical effacement and dilatation, membrane rupture and descent of the presenting part culminating in delivery of the baby followed by the placenta and membranes. Classically, membrane rupture occurs spontaneously at full dilatation but can happen at any time during the process including before the onset of active labour. In certain circumstances, which are discussed later in this chapter, the membranes may need to be ruptured artificially.

Although labour is a progressive process, it is normally divided into first, second and third stages (Table 2.1) for the purpose of management. Definition of the stages of labour needs to be clear to allow full understanding and effective communication between the woman and her attendant staff. In most cases, the outcome in terms of duration of labour and likely mode of delivery can be predicted prospectively by observing the progress of cervical dilatation and descent of the presenting part.

| Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| First | Onset of active labour to full dilatation |

| Second | Full dilatation to delivery of baby |

| Third | Period between delivery of baby and placenta and membranes |

The Partogram

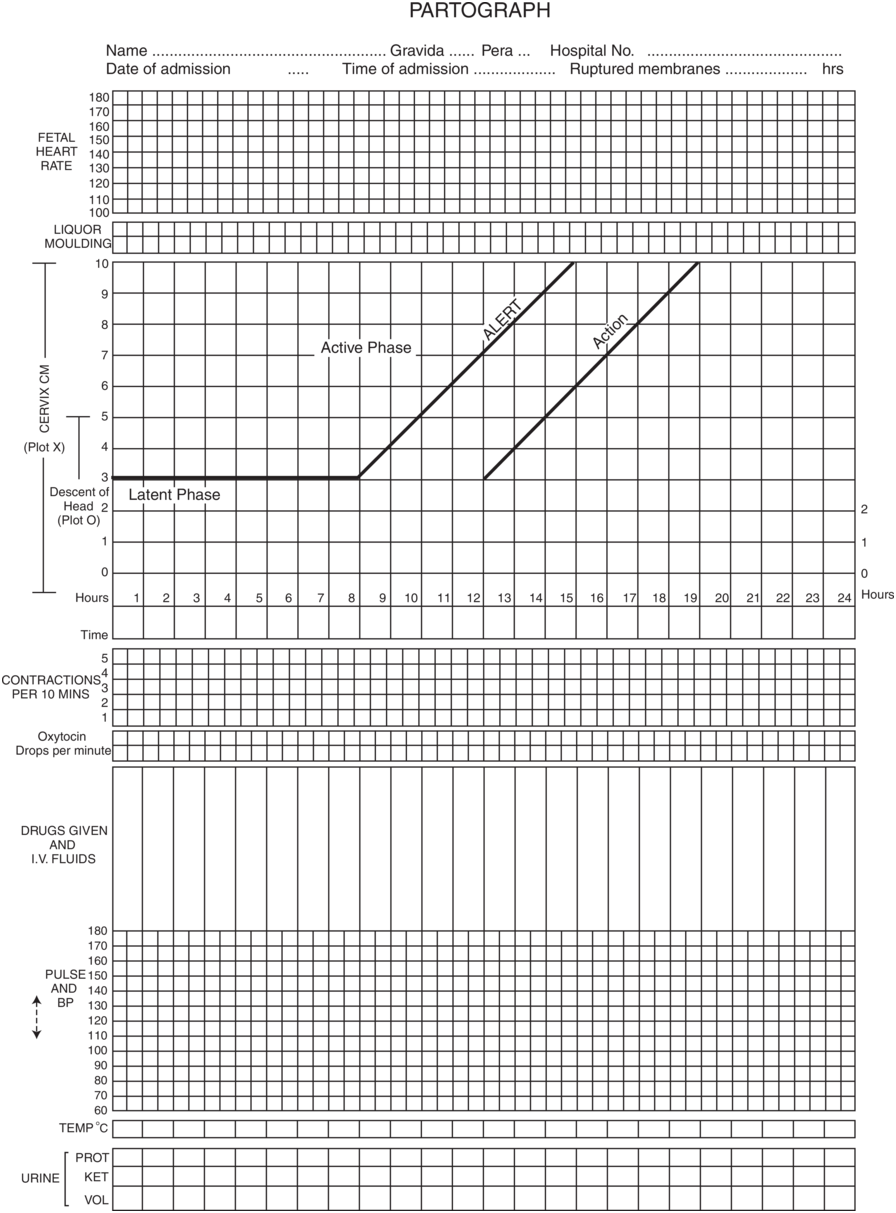

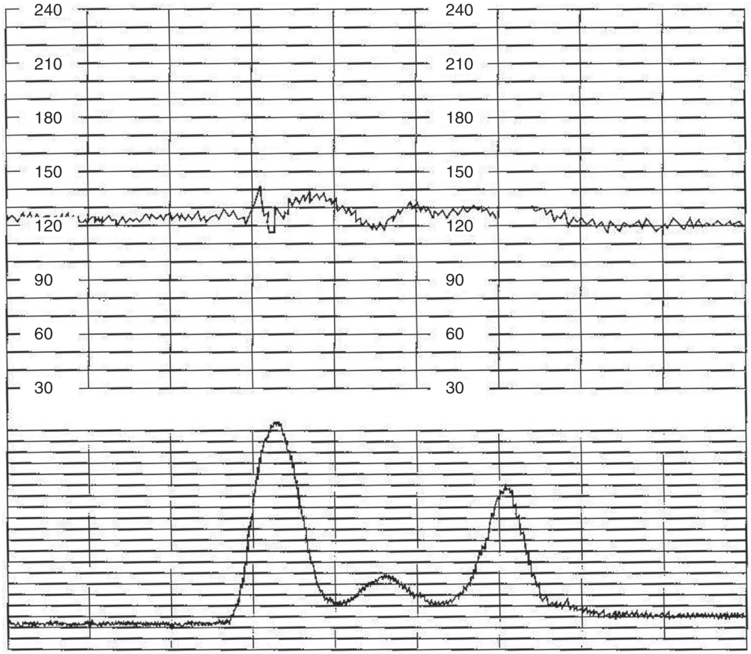

Friedman was one of the first clinicians to study labour progress [Reference Friedman6]. In 1954 he published his findings on the change in cervical dilatation of 100 consecutive primigravid women in spontaneous labour at term plotted against time. The resulting graph forms the basis of the modern partogram – a representation of labour progress along with other key events on a single page (Figure 2.1). This pictorial document facilitates the early recognition of poor labour progress. As well as cervical dilatation, recorded parameters include the level of the presenting part (in fifths of the fetal head above the pelvic brim which corresponds to the various stations or level of head to the ischial spines in centimetres above or below), the fetal heart rate (FHR), the frequency and duration of uterine contractions and the character of amniotic fluid. Maternal vital signs and any drugs used in the labour are also recorded. Plotting of the cervical dilatation at regular intervals enables prediction of the time of onset of the second stage of labour.

Figure 2.1 The WHO partograph.

Figure 2.1Long description

The partograph includes the following fields along with a dotted entry space at the top. Name, Gravida, Pera, hospital number, date of admission, time of admission, ruptured membranes and hours. A gridded area to record the fetal heart rate over time. A gridded area for recording the liquor molding. A graphical representation of cervix C M and descent of head 2 over time in hours. The horizontal axis represents a time range which ranges from 1 through 24. The vertical axis represents cervix C M, which ranges from 0 through 10. The latent phase originates at (0, 3), remains stable until (8, 3), and rises as alert until (15, 10). A linearly increasing line representing action which originates at (12, 3) and terminates at (19, 10). A gridded area is given for recording contractions, oxytocin drops per minute, drugs given and I V fluids, pulse and B P, temperature, and urine. The values are estimated.

Nomograms of Cervical Dilatation

Studies of the rate of cervical change during labour among women in different countries have shown similar patterns suggesting that ethnicity has little influence on the rate of cervical dilatation or on uterine activity in spontaneous normal labour [Reference Philpott7–Reference Arulkumaran, Gibb, Chau, Singh and Ratnam12].

Observational studies during the first stage of labour have shown that the rate of cervical dilatation is composed of two phases: the ‘latent’ phase and the active or ‘established’ phase [5]:

The ‘latent’ phase is defined as a period of time in late pregnancy when there are painful contractions with some cervical change including effacement and dilatation up to 4 cm.

The ‘established’ first stage of labour is when regular painful contractions are associated with progressive cervical dilatation from 4 cm to when the cervix can no longer be felt (10 cm).

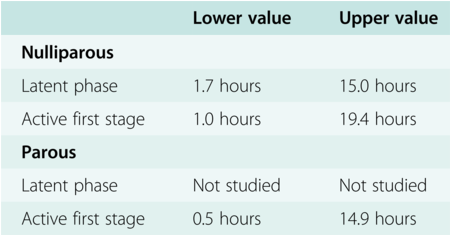

Pooled findings from a number of studies in the past showed that the range of upper limits for the duration of a normal first stage of labour in primips and multips was 8.2–19.4 hours and 12.5–14.9 hours respectively (see Table 2.2) [5]. However, in the past 15 years further studies have suggested that duration of spontaneous labour may be longer [Reference Laughton, Branch, Beaver and Zhang13, 14]. In a retrospective study conducted at 19 US hospitals, the duration of labour was analysed in 62 415 parturient women who all had normal vaginal delivery of a singleton fetus with normal perinatal outcome. In this study, the active phase started after 5 cm cervical dilatation and the 95th percentile rate of active phase dilatation was substantially slower than the standard rate derived from Friedman’s work, varying from 0.5 cm/h to 0.7 cm/h for nullipara and 0.5 cm/h to 1.3 cm/h for multipara.

Table 2.2 Summary table showing ranges for duration of stages of labour

| Lower value | Upper value | |

|---|---|---|

| Nulliparous | ||

| Latent phase | 1.7 hours | 15.0 hours |

| Active first stage | 1.0 hours | 19.4 hours |

| Parous | ||

| Latent phase | Not studied | Not studied |

| Active first stage | 0.5 hours | 14.9 hours |

Using the Friedman curve to facilitate identification of women at risk of prolonged labour, a line of expected progress can be drawn on the partogram; this is referred to as the ‘alert line’. If the rate of cervical dilatation falls to the right of this line, labour progress is slow. Conventionally, the line of acceptable progress has been based on the slowest 10th percentile rate of cervical dilatation observed in women who progress without intervention and deliver normally, which is 1 cm per hour. However, to allow for women who reach the accelerative phase of active labour a little later, a further line, ‘the action line’, is drawn parallel and 1–4 hours to the right of this to indicate when intervention is required. During the peak of the active phase of labour, the cervix dilates at a rate of 1 cm per hour in both nulliparas and multiparas. Multiparas appear to dilate faster because they have shorter labours overall; not only do they seem to have a shorter latent phase resulting in a more advanced cervical dilatation on admission, they also have an increased rate of progress as full dilatation approaches.

The Consortium on Safe Labor data highlighted two important features of contemporary labour progress. First, between 4 and 6 cm nulliparous and multiparous women dilate at the same rate and slower than previously thought and beyond 6 cm multipara dilate more rapidly. Second, the accelerative phase of active labour, when the rate of change of cervical dilatation over time is maximal, often does not start until at least 6 cm. The same Consortium did not address the duration required for the diagnosis of labour arrest although it did suggest it should not be made before 6 cm dilatation raising the question of whether the definitions of normal and abnormal labour need to be modified.

There is no consensus as to the ‘correct’ placement of the action line. The actual presence of an action line on the partogram is more important than the precise time interval between it and the alert line as its presence should ensure that action is taken if labour progress falls. Accordingly, the proportion of labours deemed to have unsatisfactory progress may vary from 5% to 50% depending on where the action line is placed. Studies looking at the efficacy of the use of the partogram, and comparison of a partogram with an action line and one without are needed.

Studies using a 2-hour action line seem to increase women’s satisfaction without any difference in intervention rates [5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) [15] and, more recently, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE, in its 2014 guidelines on intrapartum care) recommend the use of a 4-hour action line [5]. Influencing factors include the level of nursing and medical care available for the supervision of labour once oxytocin has been commenced, the risk of complications associated with prolonged labour (likely to be higher in more disadvantaged communities) and social factors.

Diagnosis of Labour

The diagnosis of true labour at term can be difficult but is more so in the preterm period when the consequences of a wrong diagnosis may be more impactful especially for the neonate. If the contractions are painful and regular and if the cervix is >4 cm dilated (in other words, in the active phase), there is little difficulty in diagnosing labour. Uterine contractions without effacement and dilatation of the cervix, also known as Braxton Hicks contractions, are common in the third trimester and usually abate spontaneously. Preterm premature tightenings are also not uncommon although, in the absence of cervical dilatation, a pathological cause should be sought. Labour itself is initiated by a complex interplay of hormonal, mechanical and electrical factors that have still not yet been fully elucidated. One trigger may be through the increase in ‘gap junctions’ or connexin proteins seen between myometrial cells before labour starts [Reference Denianczuk, Towell and Garfield16]. To differentiate between strong Braxton Hicks contractions or premature tightenings and the latent phase of labour, 2-hourly examinations, preferably done by the same examiner, may be required to detect any progressive cervical change and diagnose labour.

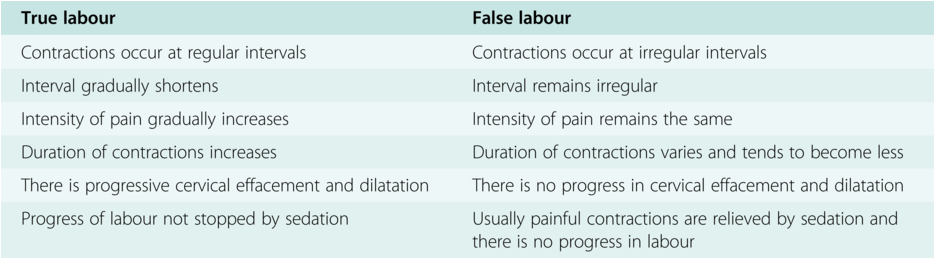

Differentiating points between false and true labour are shown in Table 2.3.

Management of the First Stage of Labour

The general principles of management of the first stage of labour are:

initial assessment

observation of progress

close monitoring of the fetal and maternal condition

intervention if labour becomes abnormal

adequate pain relief, emotional support and hydration

Initial Assessment

On admission at term with labour symptoms, a detailed history needs to be taken from the woman followed by clinical examination and basic investigations. High-risk factors, either pre-existing or newly acquired, should be identified from the history and antenatal notes [5].

The history of the presenting complaint should include details on the length, strength and frequency of her contractions as well as the associated pain and any vaginal bleeding or discharge and pattern of fetal movements.

General examination should include general appearance including pallor, jaundice, oedema and evidence of dehydration, maternal pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate and temperature. In some high-risk settings these observations can be used to ascribe a (modified early obstetric warning score and used as an aid to subsequent management.

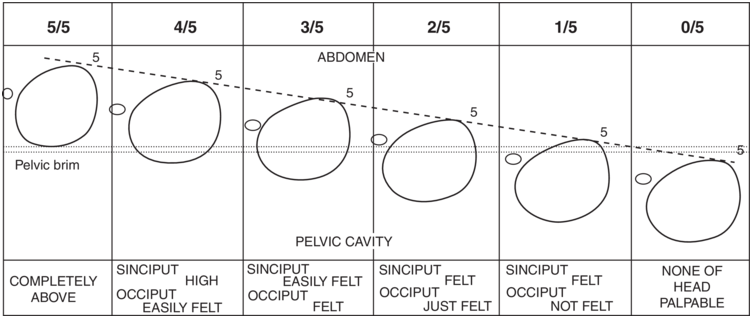

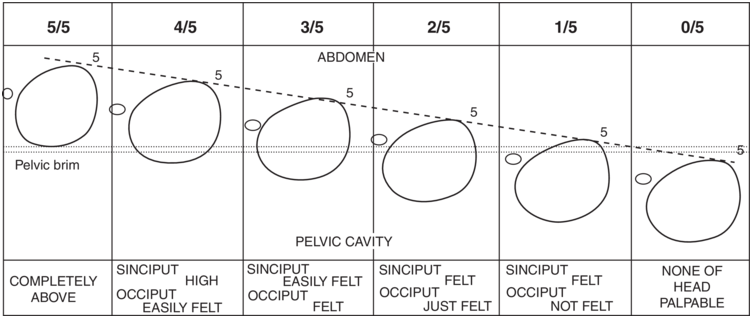

Abdominal palpation should be performed to determine the fundal height (and clinical estimate of fetal weight), the baby’s lie, presentation, position and engagement of the presenting part. With an empty bladder, the level of the head should be estimated in ‘fifths’ (Figure 2.2) – which indicates descent of the head in fifths and excludes variation due to excessive caput and moulding and that produced by different depths of pelvis and is easily reproducible.

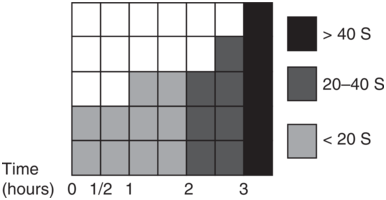

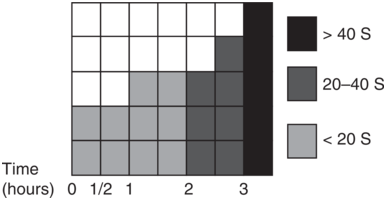

Figure 2.2 Clinical estimation of descent of head in fifths palpable above the pelvic brim. Uterine contractions should be assessed by palpation, with relevance to their frequency and duration (every 30 minutes) and assessed over a 10-minute period (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.2Long description

The first column header reads, completely above, which indicates that the descent is above the pelvic brim with a numerical fraction of 5 by 5 at the top. The second column header reads, Sinciput high occiput easily felt, which indicates that the descent is slightly within the pelvic brim with a numerical fraction of 4 by 5 at the top. Similarly, the third to sixth column headers read, Sinciput easily felt occiput felt, Sinciput felt occiput just felt, Sinciput felt occiput not felt, and none of the head palpable with numerical fractions 3 by 5, 2 by 5, 1 by 5 and 0 by 5, respectively, given at the top. A slant line connects all descents numbered 5.

Figure 2.3 Quantification of uterine contractions by clinical palpation. Frequency per 10 minutes is recorded by shading the equivalent number of boxes. The type of shading indicates the duration of each contraction.

Figure 2.3Long description

The horizontal axis represents time in hours, including 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, and 3 hours. Light shading between 0 and 2 hours indicates durations of contraction of less than 20 seconds. Mid-tone shading between 2 and 3 hours indicates durations of 20 to 40 seconds. Dark shading beyond 3 hours indicates durations greater than 40 seconds.

The fetal heart rate should be auscultated for a minimum of 1 minute immediately after a contraction and compared with the maternal pulse and recorded as a single rate [5]. A vaginal examination should be offered to check on cervical dilatation if the woman appears to be in established labour.

Vaginal Examination

The diagnosis of active labour is dependent on a careful cervical assessment to define dilatation, effacement, consistency, position and station of the head. These are more important than ‘soft’ indicators, such as regular contractions, a show, or even amniotic membrane rupture.

When conducting a vaginal examination:

be sure that the examination is necessary and will add important information to the decision-making process

recognise that a vaginal examination can feel intrusive for a woman, especially if she is already in pain or highly anxious

explain the reason for the examination and what is involved

ensure the woman’s informed consent, privacy, dignity and comfort

explain sensitively the findings of the examination and any impact on the birth plan to the woman and her birth companions [5]

The vulva and vaginal areas should be wiped clean prior to examination and the following points should be noted during vaginal examination:

any abnormal vaginal discharge

the colour and quantity of any amniotic fluid and whether it is clear, blood-stained or contains meconium

the consistency, position, effacement and dilatation of the cervix (best expressed in terms of Bishop’s score)

the presenting part in relation to the ischial spines, caput and moulding of the head

adequacy of the bony pelvis for childbirth

Investigations

Urinalysis should be performed for protein, ketones and sugar. Commercial dipsticks will also test for leukocytes, nitrites and blood indicative of a possible urinary tract infection. Commercial kits are available for the detection of the presence of fibronectin or fetal proteins in posterior fornix fluid which may be useful if there is a doubt about diagnosis of pre-labour rupture of membranes and the patient is preterm although these can also give a false positive result [Reference Berghella and Saccona17].

Hydration in Labour

Oral intake is often restricted in labour to reduce the risk of gastric aspiration and Mendelson’s syndrome should general anaesthesia be required. Women may drink during established labour, and isotonic drinks may be more beneficial than water [5].

When hydration is necessary in labour, it is best to use normal saline or Hartmann’s solution, to maintain a more physiological fluid and electrolyte balance. This may also help to avoid water intoxication if intravenous oxytocin is used over a long period in high doses.

Observations during the Established First Stage of Labour

Regular maternal and fetal observations need to be made during the first stage of labour to detect changes in maternal or fetal well-being and should be recorded on the partogram. The following observations should be recorded during the established first stage of labour:

half-hourly contraction frequency

hourly maternal pulse

4-hourly temperature and blood pressure

regularity of bladder emptying

A vaginal examination should be performed every 4 hours or if there is concern about progress or in response to the woman’s wishes.

Fetal heart rate should be auscultated every 15 minutes in the first stage and every 5 minutes in the second stage for a minimum of 1 minute after a contraction.

Mobility and Posture in Labour

The mother does not need to be confined to bed in early labour. Ambulation, or even sitting in a chair. may increase the pelvic diameters and assist in the descent of the fetal head and should be encouraged. When recumbent, either by choice or once an epidural has been sited, the woman should not be completely dorsal to avoid aorta-caval compression which can cause fetal bradycardia [5].

Use of Analgesia and Anaesthesia

Women should be encouraged to request analgesia at any time during labour when they need it. Non-pharmacological measures are available but nitrous oxide (Entonox), intramuscular narcotics (e.g. pethidine, diamorphine) and epidural analgesia are the most widely used forms of pain relief for labour. TENS, while perhaps helpful in the early stages, may not be effective in women in well-established labour [5]. Women with back problems and unsuitable for regional anaesthesia may be considered for intravenous remifentanyl but will need close monitoring for respiratory depression.

A more detailed discussion of analgesia in labour is found in Chapter 3.

Meconium

Meconium-stained amniotic fluid (MSAF) is seen in between 15% and 20% of term pregnancies, usually reflective of gestation due to fetal gut maturity beyond 34 weeks and usually of little significance especially if it is thin. However, thick MSAF may indicate an underlying placental problem causing reduced liquor volume and can be associated with poor neonatal outcome due to meconium aspiration from intrauterine gasping or when the baby takes its first breath which accounts for 2% of perinatal deaths. The appearance of fresh meconium in labour should prompt evaluation of fetal well-being. Continuous electronic fetal monitoring should be commenced and fetal scalp blood sampling should be considered if there are fetal heart rate abnormalities. MSAF is not necessarily an indication for immediate delivery if thin and the fetal heart rate is normal, but if thick and fresh and associated with an abnormal fetal heart pattern, early delivery should be considered, particularly in high-risk pregnancies.

As part of ongoing assessment in the first stage of labour, the presence or absence of significant meconium should be documented on the partogram [5].

If significant meconium is present in labour, a paediatrician should be on standby at delivery [5].

Diagnosis of Poor Progress of Labour

Progress in labour is confirmed by observing successive effacement and dilatation of the cervix and descent of the presenting part.

A labour partogram, with the anticipated progress line for an individual patient, can be used by all care providers who have been trained to assess cervical dilatation and helps identify women with slow progress who might need intervention. In a WHO multi-centre trial in Southeast Asia involving over 35 000 women, the introduction of the partograph, as part of an agreed labour management protocol, was associated with a reduction in prolonged labour from 6.4% to 3.4%, and a reduction in the number of labours requiring augmentation from 20.7% to 9.1%. The CS rate fell from 9.9% to 8.3%. There were also improvements in fetal and maternal mortality and morbidity among all women, nullips and multips alike, and there was a decrease in intrapartum stillbirths from 0.5% to 0.3% [15].

Dystocia

The term ‘dystocia’ refers to poor progress of labour or a difficult labour and is diagnosed when the rate of cervical dilatation is slower than anticipated as indicated by a deviation from the ‘chosen’ action line on the partogram [5, Reference Duignan, Studd and Hughes11].

Three distinct patterns of abnormal progress have been described [Reference Studd, Clegg, Saunders and Hughes18–Reference Arulkumaran, Koh, Ingemarsson and Ratnam21]. These are:

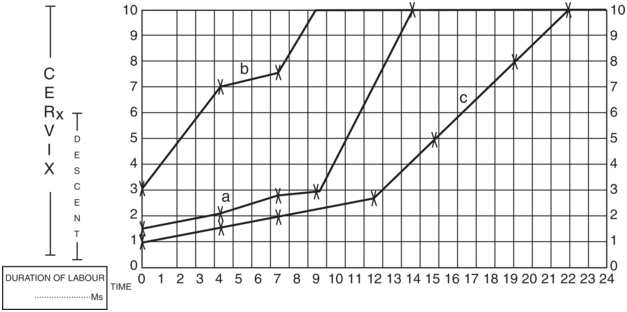

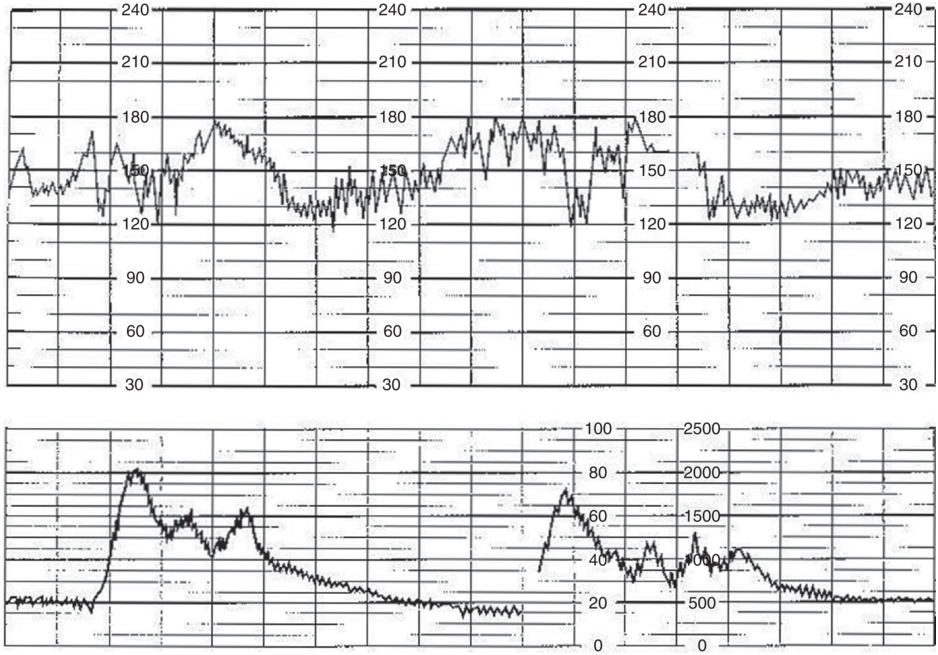

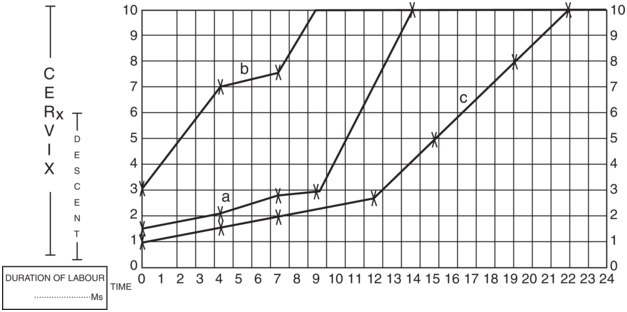

The duration of the latent phase is difficult to define. It is considered prolonged if it is greater than 15 hours in a nullipara but has not been studied in detail in parous patients so there is no such available figure [5]. Once established in the active phase of labour, primary dysfunctional labour (PDL) is diagnosed when the progress falls to the right of the nomogram. If labour progresses normally in the early active phase but the cervix dilatation stops or slows thereafter, SACD is diagnosed (Figure 2.4). It is not uncommon for more than one of these abnormal labour patterns to exist in the same patient since they frequently share a common aetiology. The descent of the presenting part (expressed as fifths) palpable abdominally is also an integral component of the partogram, and it too is plotted at each review. A poor rate of descent may be an indication of a developing mechanical problem in the labour.

Figure 2.4 Various forms of dysfunctional labour: a) prolonged latent phase; b) secondary arrest of labour; c) prolonged latent phase and primary dysfunctional labour.

Figure 2.4Long description

Line A originates at (0, 1.5), rises, and terminates at (13.5, 10), which illustrates a prolonged latent phase, characterized by a slow and gradual increase in cervical dilation over an extended initial period of labor. Line b originates at (0, 3) and terminates at (8.2, 10), which illustrates a secondary arrest of labor, where cervical dilation progresses for a time and then ceases entirely, indicating no further advancement in labor. Line c originates at (0, 1) and terminates at (22, 10), which represents prolonged active-phase labor, demonstrating a consistent but slower-than-expected rate of cervical dilation during the active phases. The values are estimated.

If delay in the established first stage is suspected, the following factors should be taken into account:

parity

uterine contractions

cervical dilatation and rate of change

station and position of presenting part

the woman’s emotional state

Poor progress has been related to problems with the three ‘P’s, namely:

powers – strength and frequency of the uterine contractions

passages – resistance of the birth canal

passenger – related to the size, position, degree of flexion, etc. of the baby

The specific cause of poor progress in labour is not always apparent but problems with the powers, passages and passenger are frequently interrelated.

The commonest abnormality of the first stage of labour is PDL, occurring in up to 25% of spontaneous primigravid labours [Reference Studd, Clegg, Saunders and Hughes18] and 8% of multiparas [Reference Cardozo, Gibb, Studd, Vasant and Cooper19] and is most often due to inadequate uterine activity.

It is much less common to see SACD than PDL, affecting around 6% of nulliparas and only 2% of multiparas. Although the commonest cause, especially in nulliparas, is also inefficient uterine activity, it is far more likely to be due to relative disproportion than PDL. Secondary arrest does not always indicate genuine cephalo-pelvic disproportion, as inadequate uterine contractions can be corrected, resulting in spontaneous vaginal delivery [Reference Gibb, Cardozo, Studd, Magos and Cooper20]. Unfavourable pelvic diameters are rarely a cause of true cephalo-pelvic disproportion in the developed world, but there may be a problem with the passages (e.g. a congenitally small pelvis, a deformed pelvis due to fracture following an accident or masses in the pelvis). A diagnosis of secondary arrest (especially in a multiparous woman) should prompt a search for obvious problems in the passenger as the fetus is more commonly the cause of relative disproportion by presenting a larger diameter due to a malposition or deflexion or both. In these cases, the dystocia may be overcome if the flexion and rotation to an occipito-anterior position can be encouraged by optimising the efficiency of the uterine contractions. Dystocia due to malpresentations such as shoulder or gross disproportion with a fetus with hydrocephalus and a head circumference above 400 mm cannot be corrected, and strengthening the contractions will just make the situation worse leading to further, often serious complications.

Management Options: Augmentation Indications

Prolonged labour is associated with high rates of maternal infection, obstructed labour, uterine rupture and postpartum haemorrhage, which may end in maternal morbidity and rarely mortality.

In many areas of the developing world it remains a common axiom ‘not to allow the sun to set twice on a woman in labour’ in order to prevent such tragic outcomes. In the early 1970s, Philpott and Castle in Harare, Zimbabwe, O’Driscoll and his colleagues in Dublin and Studd in the UK all advocated and popularised the concept of partogram use and augmentation of labour affected by dystocia to reduce the incidence of prolonged labour. This package of obstetric interventions is frequently referred to as the ‘active management of labour’.

Active management is based on the principle of anticipating and identifying a problem early and taking action (Box 2.1). It is highly prescriptive and very interventional. Increasing uterine power, which is the commonest problem, is one of several components of an active management policy which also helps to overcome any borderline disproportion by promoting flexion, rotation and moulding in vertex presentation. However, randomised control studies suggest that while it does shorten the length of labour it has little or no effect on the rate of CS or maternal or fetal morbidity [Reference Lopez-Zeno, Peaceman, Adashek and Socol22, Reference Frigoletto, Lieberman and Lang23].

Special antenatal classes to prepare women for labour

Strict criteria for diagnosing labour

Routine 2-hourly vaginal examination

Early amniotomy

Early recourse to oxytocin

A designated midwife in constant attendance and continuous one-to-one support during labour

A guarantee that labour would last no longer than 12 hours

Box 2.1 shows the principal components of the active management of labour package. Clearly not all aspects of the package directly contribute to enhancing labour progress but those focused on the woman’s support and well-being including continuity of care during pregnancy and childbirth, one-to-one midwifery care in labour, reassurance, pain relief and hydration do make it highly woman-centric [5].

The decision to augment labour should be governed by the rate of cervical dilatation based on the partogram after the exclusion of gross disproportion or malpresentation. Minor degrees of disproportion due to malposition and poor flexion of the head may be overcome by oxytocin infusion. More forceful uterine contractions cause flexion at the atlanto-occipital joint and reduce the presenting diameter. This allows rotation of the occiput from a posterior to an anterior position. The increased force of contraction helps moulding, that is, the overlapping of skull bones over the suture lines, which helps to reduce the presenting diameter of the head. It may increase the pelvic dimensions due to the descending head distending the pelvis and widening the sacroiliac and symphysis pubic joints. The parietal, occipital and frontal bones of the skull first come together (moulding), followed by one parietal bone going under the other. The occipital and frontal bones traverse below the parietal bones. If sutures meet each other it is moulding +, if gentle digital pressure is adequate to reduce the overlapping of the bones, it is recorded as moulding ++, and when digital pressure does not restore the over- lapping bones to their original position, it is recorded as moulding+++. Caput is the soft tissue swelling caused by the oedema of the scalp that develops as the fetal head descends in the pelvis. The degree of caput increases in prolonged labour, although it is a less reliable sign of mechanical disproportion compared with moulding.

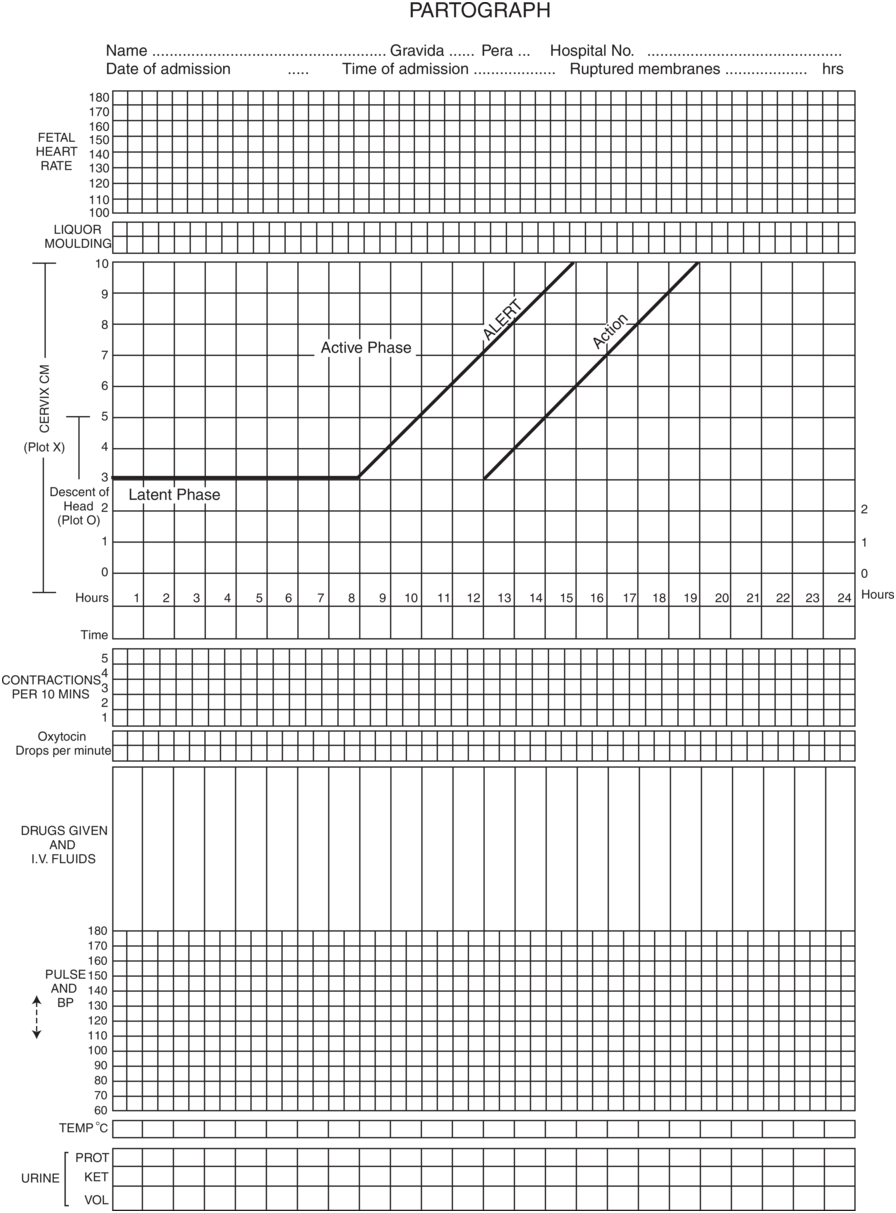

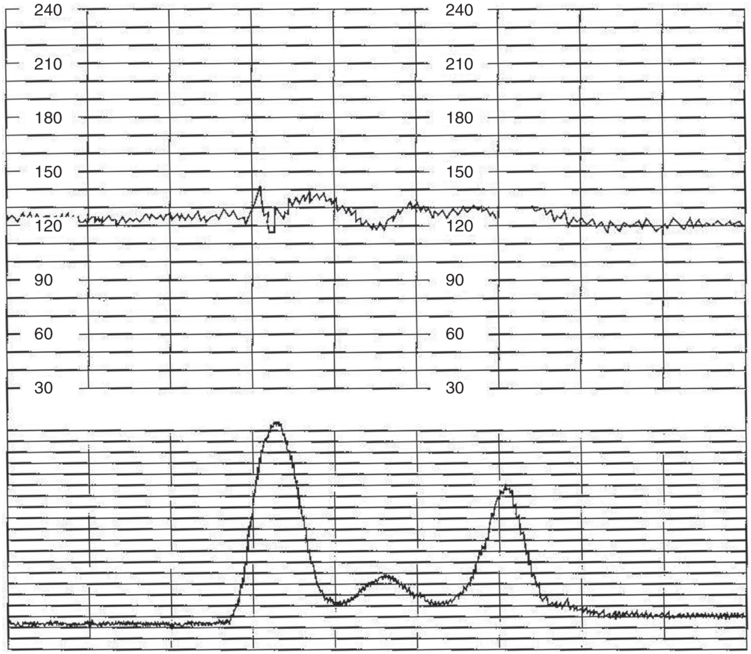

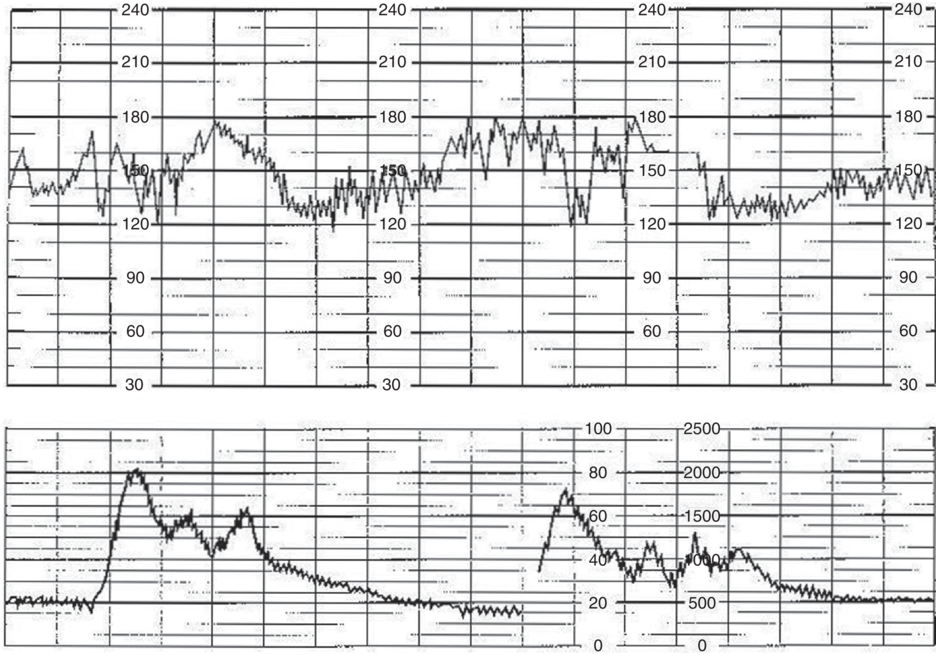

When to Augment Labour

The mechanical ‘efficiency’ of uterine contractions should be defined in terms of their clinical effect (i.e. the resultant cervical dilatation and descent of the head) and not in relation to the magnitude of uterine contractions, because normal labour progress is observed with a wide range of uterine activity in both nulliparas and multiparas. The more rapid the rate of progress for a given level of uterine activity, the more ‘efficient’ the contractions. It is also important to recognise the difference between inefficient uterine activity and ‘in-coordinate’ contractions. Inefficiency is the failure of the uterus to work in a way to result in normal labour progress and can be demonstrated when cervimetric progress is abnormal in the absence of disproportion (although both of these often co- exist). In-coordinate uterine action is a descriptive term for a pattern of tocographic tracings (Figures 2.5 and 2.6). Most records of uterine contractions will show some degree of irregularity which are not necessarily associated with abnormal labour progress. Therefore, the decision to augment labour should primarily depend on dynamic effects of the uterine activity on cervical dilatation after disproportion and malpresentation have been excluded rather than actual contraction pattern. The issue of whether oxytocin augmentation is appropriate in the presence of slow progress but apparently normal contractions as demonstrated by intrauterine pressure measurement needs further elucidation.

Figure 2.5 Mild degree of in-coordination of uterine contractions.

Figure 2.6 Severe degree of in-coordination of uterine contractions.

Further research is required into how cervical resistance contributes to abnormal labour progress. Traditionally, the active management of labour has focused on how enhancing the uterine contractions with oxytocin improves outcome. However, a significant proportion of oxytocin-augmented labours for abnormal progress still result in CS, implying that there are other factors involved. A recent in-vivo study suggested that cervical smooth muscle activity contributed to the duration of the latent phase [Reference Pajntar, Leskosek, Rudel and Verdenik24]. Other researchers have highlighted the importance of the head-to-cervix relationship, linking this to the intrauterine pressures developed during labour [Reference Gough, Randall, Genevier, Sutherland and Steer25, Reference Allman, Genevier, Johnson and Steer26]. Further research on this important topic is essential.

Augmentation in the Latent Phase of Labour

The mainstay of management of a prolonged latent phase is to avoid unnecessary intervention. The decision to augment in the latent phase should be based on clear medical or obstetric indications, since augmentation with an unfavourable cervix is associated with a high risk of CS. However, when a woman at term has been experiencing frequent, painful contractions for a long time with no progress, in the absence of evidence of other pathology, some action has to be taken. In these circumstances, augmentation may be appropriate.

Augmentation in the Active Phase of Labour

Many patients are admitted in the active phase with cervical dilatation >3 cm. The expected progress line or ‘alert line’ can be drawn at 1 cm/h on the partogram. Proponents of active management augment labour when the progress is anywhere to the right of this alert line. Alternatively, augmentation may be instituted only when the progress has deviated to the right of the ‘action line’ drawn 1–4 hours parallel to the alert line. By allowing time for labour to establish spontaneously, fewer patients will require augmentation with only 19% of nullips given 2 hours to establish needing augmentation compared with 55% given no time [Reference Philpott7, Reference Studd, Clegg, Saunders and Hughes18]. Although outcomes are similar regardless of management approach, prompt intervention does decrease the duration of labour and may be more appropriate especially when labour ward staffing is inadequate and/or number of beds is limited. To reduce the need for intervention the action line may be drawn 4 hours to the right of the alert line without affecting obstetric outcomes. The WHO study with the action line drawn 4 hours to the right of the alert line still showed a reduction in prolonged labour and CS rates [15]. The NICE guidelines on intrapartum care published in 2014 also support the use of the 4-hour action line [5].

The Role of Artificial Rupture of the Membranes

In normally progressing labour amniotomy should not be performed routinely [Reference Smyth, Markham and Dowswell27]. However, if the first stage of labour is slow to establish and the membranes are intact, artificial rupture of the membranes (ARM) or amniotomy can be performed with consent, after explanation that it should help increase the strength and pain of contractions although it does not lower the rate of CS or operative vaginal deliveries [5]. As well as enhancing the strength of contractions when labour progress is abnormal, amniotomy allows assessment of the volume and nature of the liquor in a high-risk labour especially if the FHR pattern is abnormal and allows attachment of a fetal scalp electrode or insertion of an intrauterine pressure catheter. There are some risks to ARM including cord prolapse, if the presenting part is high, and an increased risk of intrauterine infection if the labour is long. Furthermore, there is also an increased rate of fetal heart abnormalities possibly due to cord compression as a consequence of reduced amniotic fluid.

Oxytocin Dosage and Time Increment Schedules

For women making slow progress in spontaneous labour, oxytocin use is associated with a reduction in the time of delivery of approximately 2 hours as compared with no treatment but does not increase the normal delivery rate [Reference Bugg, Siqqiqui and Thornton28]. Women should be advised that oxytocin usage should bring forward the time of birth but may not influence the mode of birth or other outcomes [5].

Oxytocin receptors in the uterus increase during pregnancy and labour and the uterus may be sensitive to small doses of administered oxytocin. The drug is best titrated in an arithmetical or geometric manner starting from a low dose. Oxytocin should not be administered by gravity-fed drips, because they are unreliable and potentially unsafe. Preferentially, intravenous oxytocin should be administered using a peristaltic infusion pump. Overdosage may lead to uterine hyperstimulation and fetal distress, while a suboptimal dose may lead to failure to progress in labour, resulting in unnecessary intervention. The dangers of uncontrolled infusions include severe fetal hypoxia and uterine rupture.

Published protocols vary widely in terms of the oxytocin dilution. Higher-dose regimens of oxytocin (4 mU per minute or more) were associated with a reduction in the length of labour and chance of CS, and an increase in spontaneous vaginal birth. However, there is insufficient evidence to recommend that high-dose regimens are advised routinely for women with delay in the first stage of labour [Reference Kenyon, Tokumasu, Dowswell, Pledge and Mori29]. A more detailed discussion of oxytocin administration for augmenting labour may be found in Chapter 20, relating to induction and augmentation of labour.

Achievement of Optimal Uterine Activity and the Measurement of Uterine Contractions

There remains a dearth of literature regarding the level of uterine activity that should be produced by oxytocin titration to produce a good obstetric outcome, although with the recent development of non-invasive electrical monitoring methods based on bioelectrical signals produced by the contracting uterus akin to EEG and ECG monitoring there has been renewed interest. These methods overcome the limitations of the subjective nature of palpation, probe placement of external tocographs and risks of intrauterine pressure measurement but have not yet been incorporated into common clinical practice because of lack of technology, cost and need for training [Reference Rosen and Yogev30].

It has been suggested that the use of intrauterine pressure catheters may identify those who are most likely to need a CS for failure to progress by allowing measurement of pressure under the curve in Montevideo units (MVU). Uterine activity less than 200–250 MVU is considered inadequate and unlikely to affect expected cervical dilatation and fetal descent. The pressure required to reach full dilatation generally seems to decrease with sequential labours regardless of mode of delivery of preceding deliveries [Reference Steer, Carter and Beard31]. It is known that active contraction area measurements using an intrauterine pressure catheter correlate better with the rate of cervical dilatation than do the individual components of frequency or amplitude of contractions. Despite this, there is little evidence that using an intrauterine pressure catheter to measure uterine activity or using oxytocin titration to achieve a preset active contraction area profile is associated with a better obstetric outcome in augmented labours in terms of operative delivery rates and fetal outcomes compared with an oxytocin infusion titrated against the frequency of contractions [Reference Arulkumaran, Yang, Ingemarsson, Piara and Ratnam32].

Furthermore, the routine use of uterine pressure catheters is not recommended because of the risk of bleeding, infection and uterine perforation [Reference Madanes, David and Cetrulo33, Reference Wilmink, Wilms, Heydanus, Moi and Papatsonis34]. Uterine activity, therefore, has to be judged clinically, on the basis of the frequency and duration of the palpated contractions. As a guide, a frequency of three contractions in 10 minutes is an appropriate target uterine activity with oxytocin titration, but if there is no progress with this frequency the oxytocin dose may be increased to achieve a frequency of four or five in 10 minutes, providing the FHR pattern is normal. Overall, there is only a limited place for intrauterine pressure measurement outside a research setting.

In certain high-risk cases (such as pregnancies complicated by intrauterine growth restriction and in those where medico-legal concerns are important) there are theoretical advantages to using intrauterine pressure catheters. In addition, internal tocography can be valuable in very obese women, where external tocography is less reliable. The use of intrauterine pressure catheters has also been recommended in women with a previous CS who are being augmented for poor labour progress. A sudden decline in uterine activity may precede any clinical signs of scar rupture, such as scar pain, vaginal bleeding or maternal collapse.

Duration of Augmentation

There is general agreement that the use of the partogram and oxytocin augmentation for the management of abnormal labour progress is valuable. However, there is far less consensus regarding how long augmentation should continue before performing a CS for ‘failure to progress’.

It has been recommended that a vaginal examination is performed 4 hours after starting oxytocin in established labour and if cervical dilatation has increased by 2 cm or more further assessments can be done at 4-hourly intervals. If the cervical dilatation is less than 2 cm and the labour is allowed to continue, a further assessment should be done after 2 hours with a view to CS if the progress remains suboptimal [5].

Fetal and maternal surveillance and monitoring of the progress of labour are essential to avoid iatrogenic fetal morbidity.

Current Thinking and Future Directions of Care: Possible Role of AI

At the end of the day, obstetric outcomes are related to quality of maternity care. Much of pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity occurs in the perinatal period [Reference Lawn, Blencoe and Oza35] and is a reflection of quality of peripartum care, suggesting that financial investment in research in this area has the potential to save many lives.

While the partogram is currently the main tool to guide labour management it is only one of several contributors to labour outcome and has its limitations. Moreover, it has failed to show any clinical benefit to obstetric outcomes in low- and middle-resource countries where, arguably, the greatest barriers to decision-making and appropriate clinical action taken in response to complex labour information within the healthcare system exist. In addition, in this setting, the roles of the family of the pregnant woman and the community are key and have the potential to become the drivers for better quality of care once there is recognition that improved healthcare provision is linked to improved outcome.

It is for this reason that the WHO embarked on the BOLD (Better Outcomes in Labour Difficulty) project in two South African countries, Nigeria and Uganda, which helped in the development of a simple labour decision support tool – Simplified, Effective, Labour Monitoring to Action (SELMA) – a Passport to Safer Birth – which is focused on engagement of healthcare providers to enhance a woman’s birth experience [Reference Oladapo, Souza and Bohren36, Reference Souza, Oladopo and Bohren37]. This project aligns with the WHO’s vision of a world where every pregnant woman and newborn receives quality care throughout pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal period. The end product is the WHO Labour Care Guide, which incorporated the results from the mixed method study that looked at utility, acceptability, challenges and barriers to women-centred care aimed at promoting and monitoring birth experience [Reference Patabendige, Wickramasooriya and Dasanayake38].

Respectful Care

Non-clinical interventions to improve delivery experience are not well understood and are not always generalisable. As previously mentioned, even in the developed world, one-to-one care for primips has been shown to lower epidural rate and increase the chance of normal delivery.

Respectful care is defined as care that maintains dignity, privacy and confidentiality of women throughout pregnancy and birth and ensures freedom from harm and mistreatment which have been linked to adverse obstetric outcomes. It also enables informed choice and continuous support during labour and birth [Reference Puthussery, Bayih and Aborigo39]. This should be a fundamental human right for all women and prioritises a woman’s autonomy in decision-making around management options during childbirth.

To enable innovation and improvement of the doctor–patient relationship and to align medicine as a profession to other corporate professions, the medical staff should ideally be considered as the healthcare provider and the patient as the client, which allows user feedback to improve processes and should enable integration of the patient’s values and preferences into management options.

Labour Care Guide

Provision of good-quality intrapartum care requires the skill to identify high-risk labours and recognise women with risk factors, and the knowledge to use the partogram including when to start it, correctly place the action and alert lines and ethnic variations in pattern of labour and when and how to intervene if a complication develops. A positive attitude to intervention, when required, is also needed. The WHO Labour Care Guide differs from the WHO partogram used up to date in having more alert features that include: a) companion at birth – present or absent; facilitating hydration/ nutrition/ pain relief; supine or lateral position of mother; b) fetal heart rate; base line rate, variable and late decelerations; c) colour of amniotic fluid: clear; blood stained; meconium; d) moulding +; ++; +++; e) cervical dilatation starting at 5 cm, allowing more time for each cm dilatation (e.g. 5 hours for 5–6 cm dilatation, 4 hours for 6–7 cm, 3 hours for 7–8 cm), joint decision-making of management with the mother and additional features.

The goal of the BOLD project is to address shortcomings in existing care provision in low- to middle-resource countries by developing an evidence-based labour algorithm (SELMA) and, through community engagement, produce a more efficient, high-quality pattern of care to improve obstetric outcomes. Aided by AI techniques, which allow the non-linear data relationship to identify multidimensional classifiers that could be applied to predict expected progress and labour outcomes in women, SELMA should help providers overcome the challenges of interpreting complex labour information and translating it into appropriate clinical actions thereby optimising labour management and reducing unnecessary interventions. It may even, if successful, provide an alternative to the partogram in the future. Optimisation of task shifting by supported decision-making and individualising care would increase efficiency of the care process, improve the provider’s skills and raise community expectations through improved outcomes.

Summary

Labour is a natural physiological phenomenon leading to childbirth. Many women enjoy a safe uncomplicated vaginal birth of a healthy baby, but a small proportion continue to suffer complications from a prolonged labour and its sequelae which has led to the development of several obstetric interventions to minimise obstetric adverse outcomes. The widespread use of these has met with a degree of scepticism among some patients and clinicians over their actual necessity, highlighting the need for rigorous scientific evaluation to ensure high-quality, evidence-based, safe obstetric care is being offered to ensure the best possible outcome for both mother and baby.