1. Introduction

The recent literature on party systems demonstrates that social cleavages (Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967), political institutions (Riker, Reference Riker1987; Chhibber and Kollman, Reference Chhibber and Kollman2004), or the interaction of these two jointly influence the establishment of a party system (Cox, Reference Cox1997). In the Indian context, where regional parties have systematically grown, a recent body of literature attempts to explain the origin of regional parties. However, some scholars maintain that the origin of regional parties in India is not adequately explained by existing theories (Chhibber et al., Reference Chhibber, Jensenius and Suryanarayan2014; Shrimankar, Reference Shrimankar2020).

These scholars argue that India’s party system demonstrates a remarkable variation in regional party strength across states, which cannot be fully explained by social cleavages or political institutions alone. To explain the creation and electoral growth of regional parties in India, there is a new approach that explores the role of party organization. This exploration contributes to a theoretical debate raised by Ware (Reference Ware2007) regarding how a party’s internal organization affects other parties in the system and how it competes or coordinates with its opponents.

Similarly, Chhibber and others (Reference Chhibber, Jensenius and Suryanarayan2014) argue that politicians are incentivized to move between parties for better career advancement opportunities. This perspective is compelling for explaining why regional parties are created and continue to grow electorally. Regional parties are mostly less organized than national parties, making incumbents easier to access higher offices. Because less organized parties are usually administered by informal rules, politicians in regional parties can pursue internal promotions or expand their leadership roles beyond formal disciplines.

I embrace this notion but attempt to address several limitations that this theory overlooks. First, the theory of party organization based on career advancement often fails to consider individual incentives for reelection. If the decision to change one’s affiliation reduces their reelection prospects, politicians have less incentive to move to regional parties. Second, it insufficiently explains the varying degree of regional party strength across Indian states. Precisely, it shows limitations to explain why the organizational level of a party changes over time or across states.

In this article, I consider the role of regionally based social cleavages in conjunction with party organization. Given the deeply entrenched social cleavages, distributive preferences often diverge between national and regional parties. Cleavages negatively impact the organization of national parties, which aim to address nationalized issues clearly but localized issues ambiguously (Rabushka and Shepsle, Reference Rabushka and Shepsle1972). As cleavages become pronounced in peripheral areas, regional parties that prioritize localized issues are more easily created and electorally successful.

Social cleavages negatively affect the organizational level of national parties, creating favourable conditions for the electoral growth of regional parties. I specify the relationships between social cleavages, national party organization, and the electoral growth of regional parties. Regional cleavages initially impede the organizational cohesion of national parties. This organizational decline then accelerates the exit of regional-level politicians, leading to the creation and growth of regional parties.

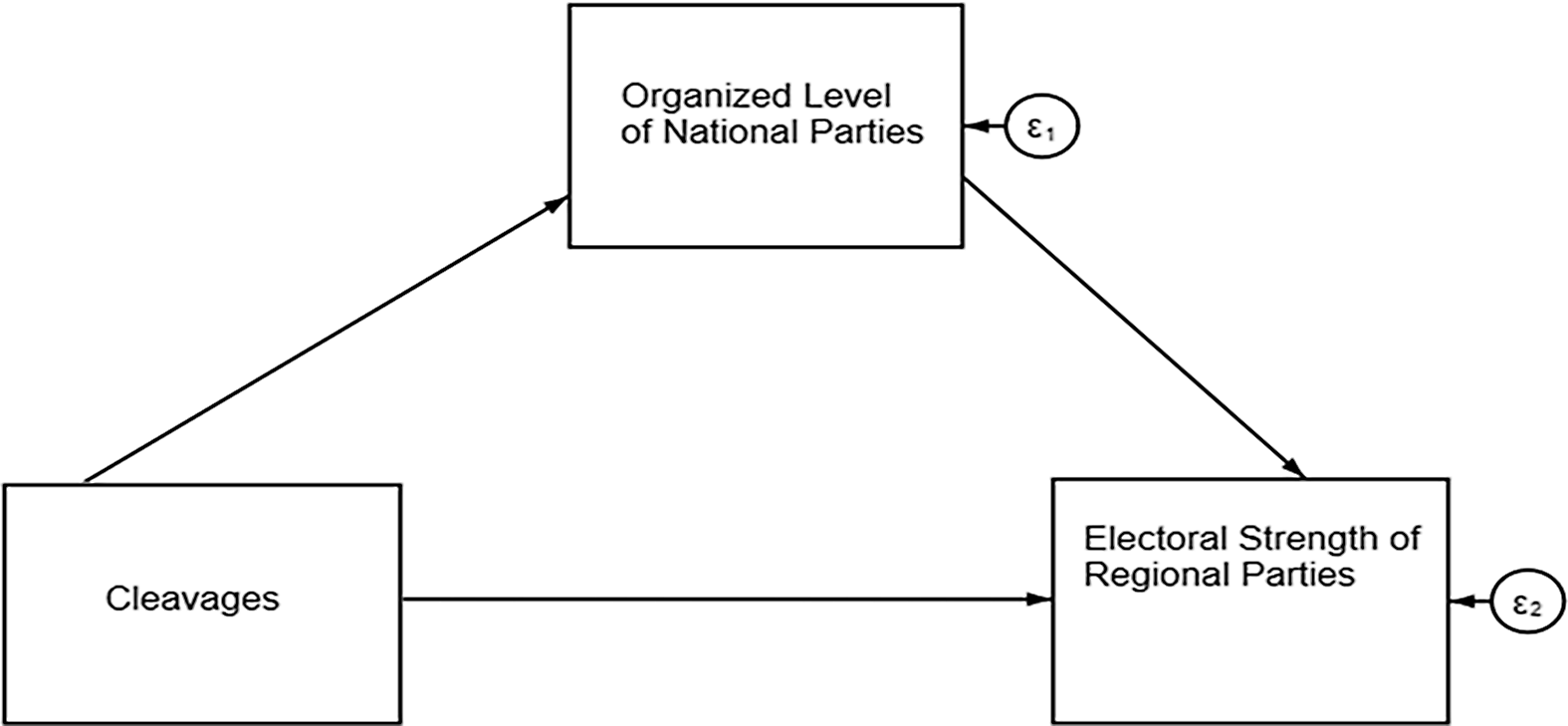

To test my arguments, I employ path analysis, a technique within structural equation modelling (SEM). This method allows me to separate the direct and indirect effects of cleavages on the growth of regional parties. Specifically, it estimates how cleavages affect regional party strength, treating the organizational level of national parties as a mediator. Although this method is suggestive and has limitations in establishing causal relationships among variables (Denis and Legerski, Reference Denis and Legerski2006), it benefits from the temporal ordering in which the decline of national party organization historically precedes the growth of regional parties in India (Ziegfeld, Reference Ziegfeld2016).

Although my theories emphasize the role of cleavages, I caution against interpreting this influence as deterministic. I maintain that India’s party system has been transformed due to the interaction between social cleavages and existing institutions. This means that cleavages are not likely to impact regional party strength without particular institutional conditions. These conditions include the presence of a national party that exercises nationwide electoral influence, such as the Indian National Congress (INC) during its era of single-party dominance.

This paper proceeds as follows. The second chapter reviews the existing theories of party organization and its impact on the party system. The third chapter elaborates on the theoretical mechanism of party system transformation. Next, I test my theories with a path-analytic model. Finally, I conclude this article with a robustness check and a summary of my findings.

2. What is party organization?

For the creation of regional parties, the cleavage-based approach has been widely embraced (Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967).Footnote 1 It overlooks the role of political institutions that shape or transform the party system (Duverger, Reference Duverger1959; Riker, Reference Riker1982). Following Cox (Reference Cox1997), who proposed that a new party can be created from the interaction between cleavages and political institutions, a growing body of literature sheds light on the dynamics of existing institutions to explain the origin of regional parties. For instance, Ziegfeld (Reference Ziegfeld2016) emphasizes elite-level coordination between parties.

Chhibber et al. (Reference Chhibber, Jensenius and Suryanarayan2014) found the role of party organization crucial. They argue that political entrepreneurs are incentivized to create new parties when it is difficult to seek higher office within existing parties. Organized parties are less likely to offer opportunities for sudden and rapid career promotion to particular politicians. These politicians are incentivized to create new regional parties in areas where the organizational level of national parties is weaker.

Several questions remain. First, politicians prize reelection over party promotion; without reelection, career advancement is meaningless. Second, many cases show established regional politicians switching to or founding new regional parties, rather than ambitious newcomers seeking higher office. Third, what exactly constitutes party organization? These points suggest that party organization and regional party growth share only a partial causal link. The growth of regional parties may be driven more directly by factors beyond party organization.

Then, I identify two issues that Chhibber and his colleagues (Reference Chhibber, Jensenius and Suryanarayan2014) overlook. To begin, they do not sufficiently explain why the level of party organization changes.Footnote 2 Next, their conceptualization of party organization is unclear. The career promotion explanation is incomplete, as party organization needs to be understood within the context of intergovernmental relationships. Party organization concerns the interaction between national organizations at the central level and regional branches at the state level (Borz and De Miguel, Reference Borz and de Miguel2019; Ibenskas and Bolleyer, Reference Ibenskas and Nicole2018).

For regional-level politicians, prioritizing localized issues specific to their jurisdiction may be the most effective path to reelection. However, once decoupled from the central organization, career advancement to higher office becomes unlikely, because regionally committed politicians have little reason to be promoted to the national level in the first place. Ambitious politicians may agree to contribute to group-level success in hopes of being rewarded after a national-level victory – but only if the expected gains outweigh their narrowly defined regional interests.

In this sense, party organization may be associated with programmatic coherence (Janda, Reference Janda1980; Borz and Janda, Reference Borz and Janda2018). However, I do not equate the two. My approach conceptualizes parties as social organizations designed to enable collective action among groups with conflicting distributive interests. In order to facilitate successful collective action, formal organizational discipline (e.g. monitoring, resource flows, candidate selection, or routines that reduce intra-party transaction costs) is required to lower transaction costs and align all branches for joint campaigning.

As Olson (Reference Olson1965) argues in his seminal work, organizations exist to enable successful collective action between members. National parties often unify diverse regional factions to compete in national elections, and an organized structure is crucial to coordinate these efforts. This necessitates formal mechanisms of discipline that ensure uniform behaviour across regional branches, thereby reducing transaction costs and facilitating coordination (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988).

For the organization, investing party resources in a single issue that appeals to the broadest population ensures efficiency. In contrast, spreading resources across multiple, incompatible distributive issues impedes economies of scale, because this fragmentation dilutes the party’s core platform and weakens its ability to mobilize support across branches. It raises transaction costs and reduces returns from collective campaigning, reinforcing the need for an organized structure.

Therefore, programmatic coherence that emerges from such coordination is merely a possible byproduct, not the defining character of party organization. Programmatic coherence around a single issue can be understood as a coordination feature of campaign communication (Kitschelt, 2000). An issue is considered nationalized when a single speech, slogan, media buy, or leader visit can be reused across multiple states with little or no additional cost.Footnote 3 This form of nationalization reflects the communicative efficiency made by strong organizational integration and should not be interpreted as a marker of ideological uniformity.

However, party organization comes at a cost. Regional branches are often pressured to ignore their own issues that conflict with shared party values, which centre on nationalized issues. Yet these issues do not necessarily benefit all regions. For example, while economic development benefits most of the population, it offers little to regions lacking initial endowments. Regional cleavages, by specifying localized demands, hence, widen the gap between regional and national concerns. Regional politicians increasingly struggle to reconcile these conflicting demands.

Regional branches may incentivize regional branches to free-ride. While relying on other branches to uphold shared campaign tasks, each focuses on localized issues to secure local support. Regional politicians prioritize political survival through reelection, as ignoring to do so means losing power. Coordination between national and regional branches may break down under regional cleavages, pressuring regional politicians and their followers to risk political survival.

Of course, the federalism literature argues that organized parties can allow regional branches to develop independent agendas that coexist with national-level agendas across different tiers of government (Ordeshook and Shvetsova, Reference Ordeshook and Shvetsova1997). Organizational flexibility, which balances national and regional branches, can help ensure success in national elections (Filippov et al., Reference Filippov, Ordeshook and Shvetsova2004; Myerson, Reference Myerson2006). In the Indian context, similarly, Shrimankar (Reference Shrimankar2020) explains that party organization reflects the degree of autonomy regional branches hold in relation to the national leadership.

This line of argument still overlooks the role of regional cleavages as a barrier to collective action. Even if organizational flexibility succeeds in certain contexts, regional cleavages are likely to permanently hinder its structural entrenchment. Even if a party is a strategic amalgamation loosely uniting region-specific factions, it would face a constant burden of justifying why relaxing formal disciplines that facilitate collective action serves its members’ interests—a burden that grows as regional cleavages deepen and localized issues become the dominant agenda.

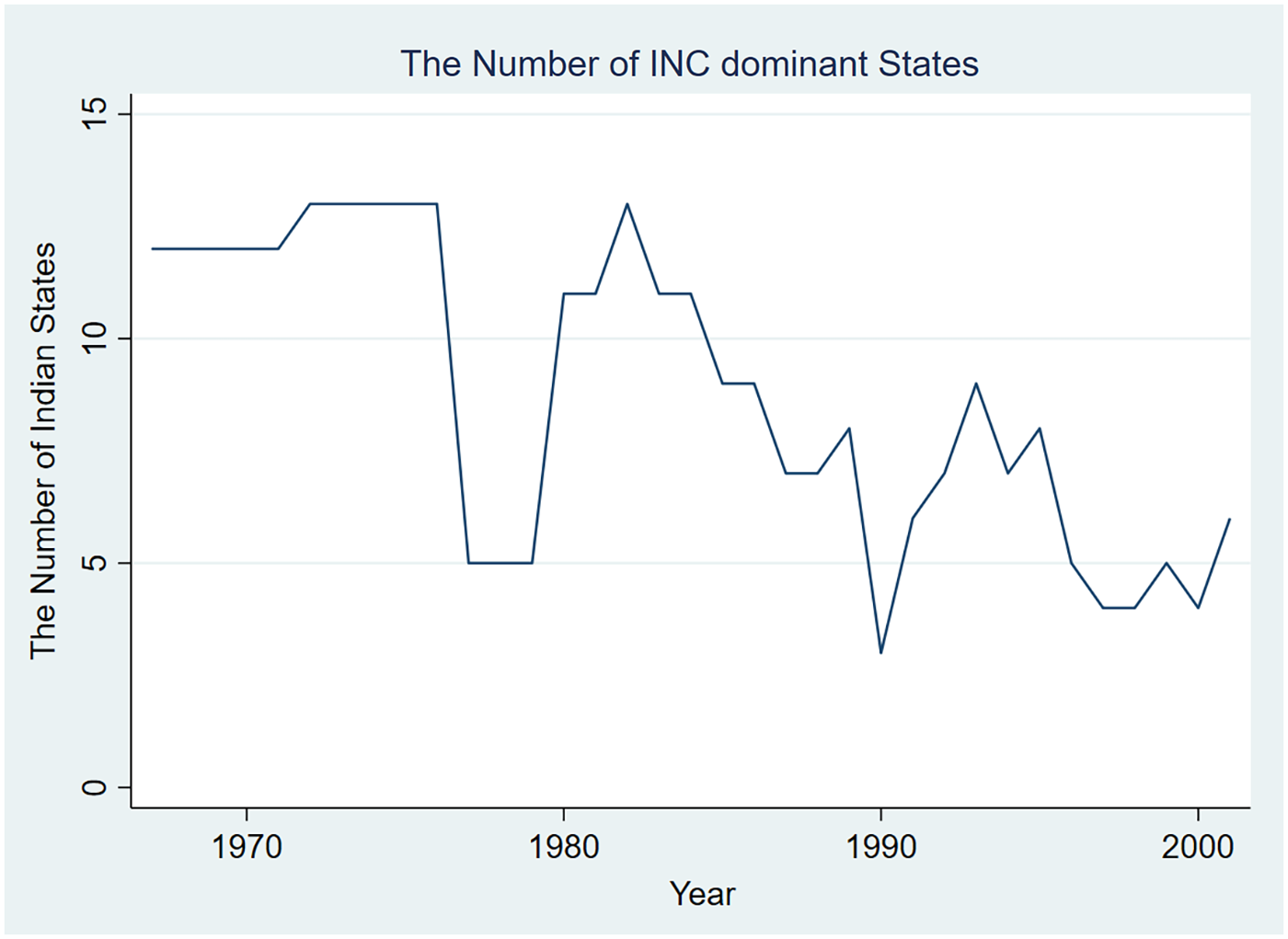

In other words, such flexibility may be only a short-term phenomenon tied to the periodic success of national elections. The case of the INC illustrates the rise and fall of organizational strength. Despite its heyday marked by all-encompassing nationalism and a nation-building agenda centred on socialism (Weiner, Reference Weiner1964; Brass, Reference Brass1994; Tudor, Reference Tudor2013), the decline of its single-party dominance was driven by its organizational decay, which preceded the rise of regional parties. Figure 1 summarizes this theoretical background.

Figure 1. Path-analytic framework.

3. How regional cleavages erode party organization

Organizational flexibility of national parties under regional cleavages may represent a risky continuation of path dependence. It may foster the illusion that a greater organization possibly accommodates regional cleavages. This is not the case. Not only does this explanation fail to address the ‘depth’ of regional cleavages and the longitudinal erosion of party structures, but it also ignores the possibility that such cleavages may be submerged or frozen, rather than fully activated (Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). In other words, cleavages may remain silent for extended periods but can resurface when triggered by specific events (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi1998).

When regional cleavages are submerged, national parties can benefit from a strong organizational structure that appeals to a broad electorate. However, once these cleavages are activated, such parties are likely to suffer the most. Rabushka and Shepsle (Reference Rabushka and Shepsle1972) offer insight into this dynamic. They examine how multiethnic political organizations often disintegrate in postcolonial states by deep regional cleavages. These organizations typically form to unite diverse ethnic groups around a common goal—such as independence—rather than to compete with one another.

After achieving independence, such coalitions often assume responsibility for nation-building. However, this exposes internal contradictions and strains their cohesion. Independence marks a path-breaking moment that fundamentally changes the rules of the game. When alien rule leaves out, multiethnic coalitions lose their incentive to cooperate. As the logic of distribution replaces the logic of extraction (Rabushka and Shepsle, Reference Rabushka and Shepsle1972: 79), questions over how to allocate internal resources within the organization become increasingly salient.

Two problems arise during this period. First, sub-coalitions demand conflicting distributive preferences. Each seeks to address its own localized issues, but given limited distributive resources, the coalition cannot satisfy every group’s demands. Second, the coalition becomes oversized. As Riker (Reference Riker1962) argues, it no longer needs to include everyone since 50% + 1 of the vote is sufficient to retain power. As a result, ‘local’ criteria may determine who is expelled and who remains in the coalition. This increases the likelihood that one group turns against another, eventually reinforcing the distinctiveness of regional cleavages across different regions.

The coalition manages these challenges by explicitly promoting nationalized issues such as territorial integrity and economic growth while keeping localized issues deliberately ambiguous. It marginalizes smaller factions focused on local interests, which accuses them of undermining nation-building. This strategy can even justify suspending democratic rights to preserve state integrity (Rabushka and Shepsle, Reference Rabushka and Shepsle1971). As the only truly national organization, the coalition claims legitimacy over national issues and maintains its leadership by keeping those issues salient.

However, the salience of localized issues tends to persist, whereas nationalized issues are more volatile. Because localized issues are closely tied to the daily needs, their importance may grow over time unless addressed. Once localized issues finally replace nationalized ones as the dominant agenda, the absence of political actors willing to address them leads to an emergence of ambitious, office-seeking political entrepreneurs outside the coalition. These actors have incentives to outbid the coalition on localized issues, threatening the sub-coalition’s support base.

The result is the breakdown of brokerage institutions that bind each branch together. During national elections, organizational cohesion between branches is likely to weaken as localized issues grow more salient in each region. Regional branches may struggle to mobilize personnel and funds and to promote their campaign promises effectively. When party discipline breaks down, then national-level politicians and party workers have fewer incentives to support regional branches as well.

Incumbents of regional branches are most affected by this decoupling, which accelerates the erosion of internal party organization. As long as they remain in the coalition, they risk losing their reputation as respected community leaders and being blamed for neglecting localized issues. When they struggle to control their followers within the branch, they increasingly rely on centralized decision-making over party discipline or personalize branch resources for their own political survival.

This strategy becomes less effective with time. At that point, incumbents may find greater incentives to create regional parties focused on localized issues and position themselves as their leaders. As they were initially community leaders as a part of nation-building process, they could easily claim regional leadership in the periphery and compete against the weakened branch of multiethnic coalitions.

Forming national parties is less attractive given the distributive demands of the local population. As factional leaders, incumbents show limitations to build national parties and compete against the coalition focused on broader issues. In contrast, by creating regional parties, they easily mobilize resources for their homeland, sending a credible signal of their commitment to localized issues. Finally, regional cleavages undermine the organizational cohesion of national parties by weakening their regional branches, which facilitates the growth of regional parties.

4. What is the reaction of national parties?

I still acknowledge the possibility that regional parties can expand in certain areas despite the presence of well-organized branches of national parties. In other words, regional cleavages may directly foster the electoral growth of regional parties without necessarily diminishing the organizational strength of national parties.

In plural societies, national parties often face a fundamental coordination problem: sustaining vertical organizational cohesion while competing across heterogeneous state-level electorates (Rabushka and Shepsle, Reference Rabushka and Shepsle1972; Habyarimana et al., Reference Habyarimana, Humphreys, Posner and Weinstein2007). These two objectives are often in conflict—but they are jointly attainable only when parties succeed in reducing coordination costs. To mitigate the risks of fragmentation, parties often prioritize cohesion, despite the costs of losing their electoral influence.

National parties may prioritize organizational cohesion to prevent internal breakups. Expelling or allowing the defection of ethnic groups focused on localized demands may weaken the electoral influence but at least help preserve its organizational integrity. Malaysia’s expulsion of Singapore from the coalition illustrates this logic. A reduction in organizational size does not necessarily signal an inability to rebuild a winning coalition (Bormann, Reference Bormann2019).

The literature on federalism substantiates this claim. As many scholars maintain (e.g. Horowitz, Reference Horowitz1985), the federal system mandates state-level government to address localized issues directly, enabling national parties to avoid distributive conflicts within the central government. Despite the theory that federalization reduces the electoral influence of national parties (Brancati, Reference Brancati2008), it might be efficient in preserving the minimum organizational strength of national parties.

Similarly, in districts where regional parties have already grown, it is not uncommon for national parties to abstain from participating in district-level elections (Stepan et al., Reference Stepan, Linz and Yadav2011). For national parties, investing their resources in localized goods is not beneficial, given their lower probability of winning in the first place. Adeney (Reference Adeney2007) and Tummala (Reference Tummala2009) also observe a pattern in India where some national parties withdraw their participation from district-level elections.

Therefore, national parties are sometimes incentivized to allow the electoral growth of regional parties at the state level in order to preserve their organizational cohesion across different tiers of government. In other words, cleavages have direct effects on the creation and growth of regional parties. In regions with distinct cleavages, these effects could bypass the impact of national party organization.

5. Empirical strategies

My theories hypothesize both direct and indirect effects of cleavages on the electoral growth of regional parties in India. The indirect effects are measured by examining the mediating role of national party organization between cleavages and regional party strength. The direct effects measure the impact of cleavages on regional party strength. I empirically test my hypotheses using a simple SEM. By employing a path-analytic model, I differentiate between the direct and indirect effects of cleavages. This approach allows me to isolate the mediating effects of national party organization, which has already been influenced by cleavages.

5.1. Classifying parties as regional or national

The distinction between national and regional parties in India is critical.Footnote 4 While the Election Commission of India classifies parties as national or regional based on widely recognized criteria involving vote and seat shares in each election, I find this method arbitrary. This approach can lead to frequent reclassification of parties based on fluctuating electoral performances, which does not align with my objectives. Alternatively, Ziegfeld (Reference Ziegfeld2016) proposes measuring the geographical concentration or dispersion of a party’s supporters.

Using the Adjusted Vote Fragmentation Index (VFI), Ziegfeld explains that a party with a VFI score below 0.25—a threshold also used by the US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission—is classified as a regional party. Conversely, a score above this threshold indicates a national party. Ziegfeld (Reference Ziegfeld2016: Chapter 2) argues that this threshold is effective because the classification of parties does not change dramatically over time, as few parties have VFI scores that fall between 0.18 and 0.25. The list of national and regional parties is included in the appendix.

5.2. Dependent variable

I measure regional party strength from 15 major states in India. I do not account for all 28 states. The largest 16 states account for over 95% of the total population (Government of India, 2011), and the remaining states are often considered outliers. However, my sampling of 15 states is due to the availability of data on party organizations. The existing information on party organization covers these 15 major states (Chhibber et al., Reference Chhibber, Jensenius and Suryanarayan2014) and includes state-level elections from 1977 to 2004. I structure my dataset in a state-year format, resulting in 380 observations.Footnote 5

I use the vote share of all regional parties receiving at least one seat in the state assembly. As a result, I count the sum of vote shares of all regional parties as an observation. The decision to consider state-level elections is straightforward: the primary concern of regional parties is to maximize their influence within a state government, and it is relatively rare for them to expand their electoral influence outside their ethnic homelands or ambitiously challenge national leadership.

The coalition politics of India substantiate my focus on state-level elections. As argued, regional parties often coordinate with national parties to further establish their dominant positions within their homelands. National parties may decide not to participate in some district-level elections where they are less likely to be supported and are rewarded by inviting regional parties into governing coalitions (Tummala, Reference Tummala2009; Ziegfeld, Reference Ziegfeld2012). Alternatively, regional parties may not participate in national elections and assist national parties (Stepan et al., Reference Stepan, Linz and Yadav2011).

Vote shares of regional parties in national elections cannot measure their electoral strength. They are initially less interested in national elections and have an incentive to trade their national-level performance for greater leadership within their regions. Moreover, state-level elections are relatively free from coalition politics compared to national elections due to reduced bargaining complexity (Laver, Reference Laver1989; Roubini and Sachs, Reference Roubini and Sachs1989). With these considerations, state-level elections are less biased to independently compare regional party strength with their national counterparts.

5.3. Independent variables

5.3.1. Cleavages

There are two independent variables: cleavages and the level of party organization. To measure cleavages, I use two indicators – the Regional Distinctiveness Index (RDI) and the Over-Representation Index (ORI), a variation of the RDI (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2020; Cartrite and Miodownik, Reference Cartrite and Miodownik2016). Using the idea of Markusen and Schrock (Reference Markusen and Schrock2006), both indicators capture how the group composition of a given state is dissimilar from the national average. They reflect the extent to which particular groups are demographically concentrated in a single state, making regional branches more exposed to factionalized demands compared to the broader national context.

Considering religious groups (Hindu/Muslim/Other) as well as the Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) from the NES 2004 data (Heath Reference Heath2005), the RDI measures the overall magnitude of demographic divergence between a state and the national average: it rescales the result to a 0–1 range, where 0 denotes an identical composition and 1 denotes maximal divergence. On the other hand, the ORI considers only positive deviations—groups that are over-represented in a given state relative to their national weight—so quantifies the extent to which a state is ‘specialized’ in particular communities.

A high RDI indicates strong demographic misalignment. This forces state branches to balance multiple, often conflicting, local demands with national programmatic goals. A high ORI shows that one or a few groups hold disproportionate demographic weight. These groups can demand targeted benefits that clash with the centre’s broader coalition strategy. In both cases, the central leadership faces a dilemma. Enforcing discipline risks alienating key regional voters. Relaxing discipline, on the other hand, weakens vertical integration. Either choice disrupts coordination between regional branches and the national leadership.

5.3.2. Party organization

Second, in order to assess the level of party organization, the CJS data (Chhibber et al., Reference Chhibber, Jensenius and Suryanarayan2014) is applied in my analysis. This dataset compiled information on the organizational structure of all Indian parties that garnered at least 5% of the vote share in state elections spanning from 1967 to 2004. Each state/party branch is employed as a unit of analysis, treating each party branch as an observation. This approach indicates that the same party may exhibit varying levels of organizational strength across different states simultaneously.

This variation could reflect differences in leadership within states or the party’s interactions with other political leaders at both state and national levels. Every party branch is assigned a score of 1, 2, or 3, with 3 indicating the strongest organization and 1 the lowest. A party is considered less organized if it lacks a clear succession plan, has fluid and election-focused roles for party officials, and provides limited opportunities for advancement. Such a party relies on the charisma of a charismatic leader, and commentators often describe its decision-making process as ‘ad hoc’.

Shrimankar (Reference Shrimankar2020) uses this data to measure the autonomy of regional branches. While this approach is relevant, the data more accurately capture the unpredictability of regional branch behaviour relative to national-level expectations. This unpredictability makes it difficult to enforce a shared campaign task, as internal uncertainty increases. As a result, successful collective action becomes unlikely, given the rising transaction costs between branches.

While most Indian parties are believed to have unclear organizational structures, Chhibber and his colleagues (Reference Chhibber, Jensenius and Suryanarayan2014) discuss that some states have parties with highly formalized organizational structures. The CPI(M) in West Bengal is one such case. Bhattacharya (Reference Bhattacharya2002) notes that the CPI(M) has established a broad organizational network, formalized discipline over representatives, and maintained full control over the selection of candidates. Survey responses also suggest that they aim to provide promotional chances based on routinized procedures (Bhaumik Reference Bhaumik1987: 162).

On the other hand, the Bihar branch of the INC in 1967 is considered less organized, owing to intensified internal factional strife and the defection of sub-coalitions. Rudolph (Reference Rudolph1971: 1125) also notes that some intra-party factions within the INC continued to appeal to princely or feudal interests, which remained largely unconstrained by the senior leadership in Delhi. These examples suggest that a party branch’s organizational strength is closely tied to its relationship with the national party organization in the central government.

5.3.3. Descriptive information

Since my focus is on the organizational level of national party branches, I measure the organizational strength of the most voted national party in each Indian state. In my measurement, national parties are classified as those with electoral influence across multiple states. These parties require an organized structure to coordinate across branches and optimize electoral outcomes, regardless of their platforms.

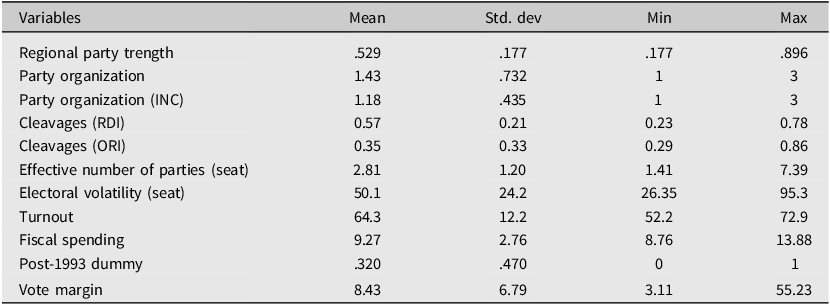

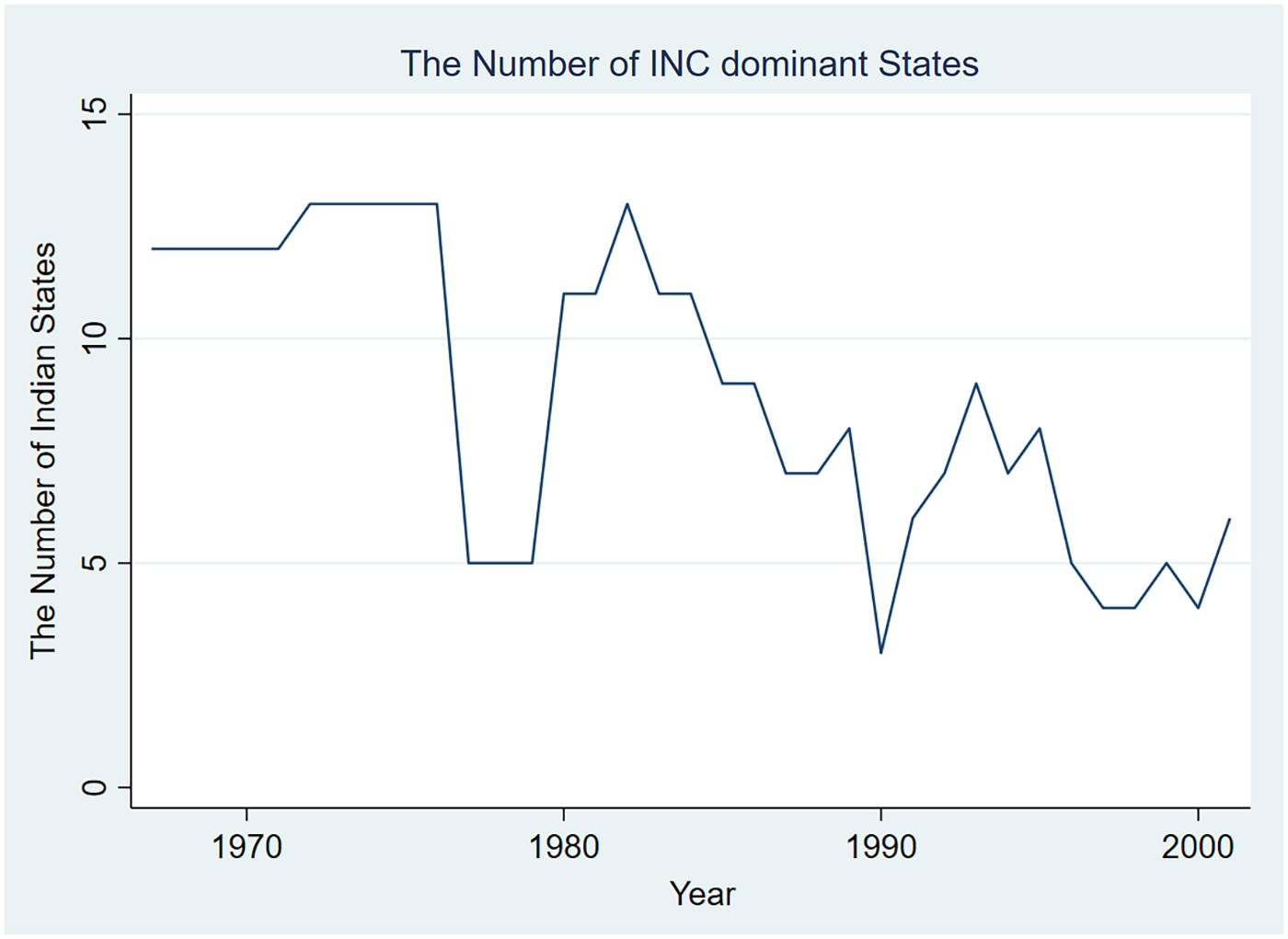

Despite this, it is worth considering the historical dominance of the INC as a nationwide ruling party in most states. As shown in Figures 2 and 3, both the number of states where the INC held power and the organizational strength of its state branches declined over time. This makes it plausible to examine how regional cleavages and organizational erosion contributed to the end of the INC’s single-party dominance.

Figure 2. The number of INC-dominant states over time.

Figure 3. Comparing organized levels of two different groups.

It is thus useful to distinguish between states of the INC and (the most voted) non-INC national parties. I assess the organizational strength of the INC and non-INC national parties in separate models. This allows me to examine whether regional cleavages have differential effects on INC and non-INC branches. While the INC is more likely to experience organizational decline due to its highly nationalized appeal and high coordination costs, it is worth exploring whether a similar dynamic also affects other national parties that may be less nationalized than the INC.

Therefore, my analysis distinguishes among three groups. The first includes national parties that received the most votes in state elections. The second focuses specifically on the INC. The third consists of non-INC national parties, even if they were not the most voted party in a given state. In cases where the INC receives the highest vote share, the national party with the next closest vote margin is included in this third group.

Figure 3 supports this argument. The left plot compares the mean organizational strength of INC branches to that of the most voted non-INC branches in each state. The organizational strength of the INC declines more sharply. It is probably due to the INC’s broader organizational reach across the country, making it more vulnerable to the effects of regional cleavages. Then, it is plausible to infer that less nationalized parties are less vulnerable to the effects of regional cleavages.

Then, the right plot compares two groups within the INC: states where the INC is the ruling party and those where it is not. The former group shows a sharper decline in organizational strength. This suggests that when the INC holds a majority in the state, its branches are forced to make a distributive decision between nationalized and localized issues. In contrast, when the INC is not in power, its branches are less directly exposed to the pressures of regional cleavages, making their organizational ties to the national party less vulnerable to erosion.

5.3.4. Control variables

I use several control variables expected to influence regional party strength. Beyond social cleavages, I include political institutions relevant to the growth of regional parties. The first is the Effective Number of Parties (ENP), calculated following Laakso and Taagepera (Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979). As the number of effective parties increases and no single party can easily secure a majority, political entrepreneurs are more likely to form new parties to become pivotal players or position themselves for inclusion in governing coalitions (Nooruddin and Simmons, Reference Nooruddin and Simmons2015).

I add the vote margin between the top two parties, regardless of whether they are national or regional. A narrow margin may signal a chance for political entrepreneurs to form a new party as a potential moderator between the competitors. The third is electoral volatility, measuring how much voter support shifts between parties from one election to the next. It indicates the stability of the party system and serves as a proxy for the extent to which politicians switch parties (Chhibber et al., Reference Chhibber, Jensenius and Suryanarayan2014).

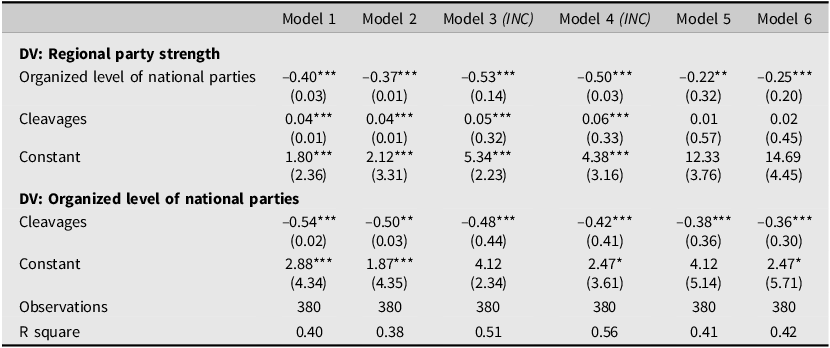

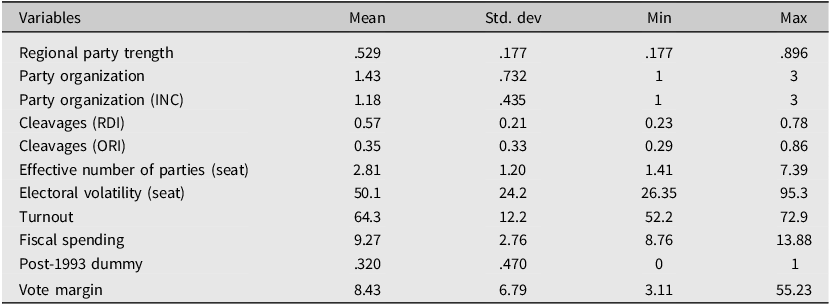

Table 1. Descriptive information of key variables

The fourth is turnout. State elections are often considered second-order elections, seen as less important than national contests (Reif and Schmitt, Reference Reif and Schmitt1980; Schakel and Swenden, Reference Schakel and Swenden2018). If this is the case, higher turnout suggests that the local population places greater importance on state elections, creating favourable conditions for the growth of regional parties rooted in subnational politics.

The next consideration is decentralization, which is believed to promote the electoral growth of regional parties by empowering state governments and increasing the importance of state elections (Brancati, Reference Brancati2008). Due to the lack of fine-grained state-level data, I use two proxies. The first is the fiscal expenditure of each state government. As a state’s fiscal spending grows, decisions about where to allocate resources become more politically significant. The second is a post-1993 dummy variable capturing the decentralization reform introduced by the 75th Constitutional Amendment. This reform reshaped the governmental structure and enhanced the policymaking authority of the third tier of government, thereby increasing the salience of state elections (Ziegfeld, Reference Ziegfeld2012; Massetti and Schakel, Reference Massetti and Schakel2017). The information on these key variables is summarized in Table 1.

6. Results

One key difference between a simple linear regression and SEM is that the latter typically does not estimate the impact of control variables on the dependent variable. This approach preserves the theoretically assumed direction of paths, so it does not alter or imply any new causal relationships (Winship and Mare, Reference Winship and Mare1983). In path analysis, control variables thus only influence the strength of the estimated effect along each path.

There are six different models in my analysis. While the first and second models employ the organized level of the most voted national party, the third and fourth models use the organized level of the INC in each state. The fifth and sixth models use the organized level of the non-INC. While the first, third, and fifth models employ the RDI index, the second and fourth use the ORI index. In every model, I successfully estimate the indirect effects of cleavages that pass through party organization as a mediating variable.

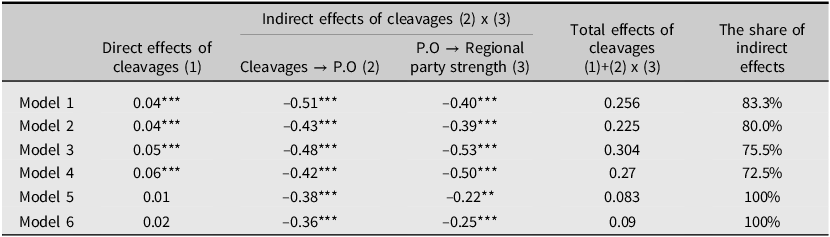

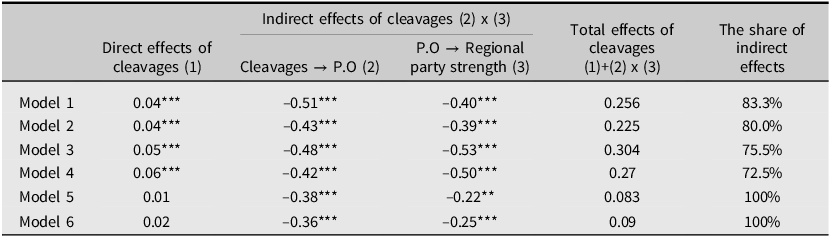

Table 2 summarizes the results. In model 1, when cleavages increase by 1 unit, it likely lowers the organizational level of national parties by 0.54. Then, a decreased organizational level is associated with a 40% growth in the total vote shares of all regional parties. Since indirect effects are calculated by multiplying these two direct effects, the mediating effect of party organization (indirect effects of cleavages) is 0.216.

As shown in Table 3, when the direct effects (0.04) are included, the total effect is 0.256. This suggests that regionally based social cleavages, initially entrenched in a given region, are associated with a 25.6% increase in the vote shares of all regional parties in state-level elections. Although the direct effects are relatively modest, the indirect effects emphasize the importance of organizational structures within national parties to explain the creation and growth of regional parties.

Table 2. The direct and indirect effects of cleavages to regional party strength

Table 3. Subdivisions of the total effects of cleavages

I also verify the direct effects of cleavages on the organizational level of national parties. These direct effects are significant only in the first four models, which focus on the organizational level of the most-voted national party and the INC. This nuance suggests that the INC branch is more influenced by direct cleavages in terms of organizational level during its period of single-party dominance.

I find that the organizational strength of the INC declines more sharply than that of other parties in the presence of regional cleavages. This suggests that the broader a party’s organizational network spans across regions, the more vulnerable it is to being undermined by regional cleavages. As a party’s organizational structure expands across a broader region, transaction costs for successful collective action between branches are likely to increase accordingly.

Models 5 and 6 support my findings. When party organization is measured based on the most voted national parties other than the INC, regional cleavages show limited impact in reducing their organizational strength. I interpret this for two reasons. First, these parties were less ‘nationalized’ than the INC, so they had less need for a highly organized structure. Compared to the INC, their electoral influence during the period under study was narrower across states. They may have been less exposed or less sensitive to the effects of deeper regional cleavages.

For instance, although both the INC and the Communist Party of India (Marxist), or CPI(M), are classified as national parties, the CPI(M)’s electoral influence is largely limited to a few states, primarily Kerala. Local demands in Kerala become especially important to the party, requiring greater responsiveness to local concerns. Despite its ideological commitment to communism, allocating internal resources towards this ideal may be less efficient for maximizing electoral outcomes.

In all models, the coefficient values of the indirect effects are greater than the direct effects of cleavages. This highlights the significant role of national party organization in the electoral growth of regional parties. This suggests that many regional parties may have originated from within national parties. Even when their founders were not formally affiliated with national parties, political entrepreneurs may have inherited existing organizational structures to create new parties, rather than mobilizing entirely new personnel or resources independent of national parties.

This analysis contributes to the broader debate on the origins of regional parties. My interpretation assumes the nationwide presence of a dominant party, as exemplified by the INC during its era of single-party dominance. In the absence of such dominance, national parties tend to fragment. They have less incentive to pursue a nationwide platform aimed at broad electoral appeal and may instead focus on more factionalized issues. In such contexts, the growth of regional parties may be limited.

The growth of regional parties may be related to single-party dominance along with regional cleavages. Beyond India, similar patterns can be observed in Malaysia and Ethiopia, where regional parties emerge from single-party dominance by the UMNO (United Malays National Organization) and the EPRDF (Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front) despite persistent pressure from ethnic divisions across regions. In other words, these cases suggest that the rise of regional parties may be tied to the presence of a multiethnic coalition under centralized leadership and its subsequent organizational erosion in the face of regional cleavages.

7. Conclusion

The main theory elaborated in this article is that the organizational structure of national parties can impact the creation and growth of regional parties. I also found that the extent to which a party is organized is initially affected by regionally based social cleavages. In this case, cleavages influence the national party organization, which indirectly affects regional party strength. To statistically test the relationship between cleavages, party organization, and regional party strength, I use the method of path analysis between these three factors.

Using state-level election data from 1967 to 2004, I verify a statistically significant relationship between cleavages, the level of party organization, and regional party strength. I affirm that cleavages negatively impact the organizational structures of national parties, which precedes the electoral growth of regional parties. Finally, decreased organizational cohesion of national parties is likely to increase the total vote share of regional parties. In addition to the indirect effects of cleavages, my estimation found direct effects of cleavages on regional party strength. In some cases, the influence of national party organization can be bypassed or nullified.

Of course, path analysis alone, as a statistical method, cannot establish causality among a set of variables. Indeed, my model is not entirely free from the possibility of reverse causality, whereby the electoral growth of regional parties may diminish the organizational strength of national parties. Despite this endogeneity, I maintain that my model still benefits from the temporal precedence of declining national party organization relative to the growth of regional parties.

Recent studies of Indian politics explicitly show that regional parties began to expand following the end of the INC’s single-party dominance. For example, Ziegfeld (Reference Ziegfeld2016) observes that the erosion of the Congress system weakens the organizational strength of national parties, thereby creating opportunities for new parties to become pivotal players when any party holds a guaranteed majority. This causal context allows me to infer that causal modelling is feasible—albeit with limitations—among cleavages, the organized level of national parties, and the growth of regional parties.

The main contribution of this article is its theoretical improvement regarding party organization. Although some literature discusses its impact, many still overlook the reasons why the level of party organization varies across states, even within the same party. This article finds that deeply entrenched social cleavages, such as religion, language, tribe, or caste, can alienate regional-level politicians by pressuring them to be more responsive to localized issues. It undermines the institutional linkage of national parties that prioritize programmatic coherence across states.

Lastly, my theory requires one assumption to address external validity outside of India: there should be a strong national party that exercises its nationwide influence across all states. Otherwise, national parties would be fragmented and have fewer incentives to maintain the provision of nationalized goods, as they would have no reason to appeal to a broader base of electorates. This situation incentivizes them to provide localized goods to selectively reward their core supporters or deter the electoral growth of rival parties.

While this article highlights the organizational dynamics of national parties, it also has limitations. My framework places less emphasis on coalition politics, which remain central to India’s party system. Nevertheless, it suggests that distributive cleavages negotiated within parties can extend to coalition formation. National parties must weigh whether to accommodate or ignore factional demands, knowing that neglected factions may later reemerge as coalition partners.

This decision turns on a comparison of the distributive resources required to satisfy intra-party factions versus those needed to secure external coalition partners. Party organization in India may evolve with an eye to external coalition possibilities.

The relationship between single-party dominance and the growth of regional parties needs further examination in future research. Under this condition, cleavages might overcome institutional constraints such as electoral rules, to explain the growth of regional parties. This suggests a theoretical possibility that single-party dominance combined with regionally based cleavages can be the institutional origin of the creation and electoral growth of regional parties. I observe that Malaysia reveals a similar trend of party system transformation. Future comparative work on India, Malaysia, or Mexico could enrich the core theory of this article.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109925100157