This book charts a nonlinear history of both the idea and the practice of architectural rebuilding roughly from the establishment of the Principate under Augustus in the late first century BCE to Justinian’s Christianized empire of the mid sixth century CE. It argues that “old” buildings and the mechanisms through which their age was framed by later architectural modifications – whether celebrated, recast, or masked – shaped Roman and late antique experience of time in materially perceptible and place-specific terms. As we shall discover, this was a world in which architectural restoration did not strive for faithful replication of the original appearance of damaged structures. Instead, rebuilding projects, and descriptions of them, often explicitly emphasized observable properties of the revised structure. They might extol the new while simultaneously celebrating the building’s ancient origins, deploring its recent ruinous state, and selectively expunging traces of intervening chapters of the building’s biography.

Centering ancient rebuilding as an object of study in its own right reveals it to be a powerful political, social, and religious tool for patrons of many stripes and an endeavor deeply embedded and highly visible within larger systems of benefaction, exchange, virtue, and memorialization. Emperors, elite benefactors, clerics, and collective groups deployed architectural rebuilding as a means to renegotiate relationships between past and present and to project those relationships forward to subsequent generations. Regardless of whether patrons’ wishes were met, through monumental text and other differences of form or appearance, restored or revised buildings staged confrontations between old and new, the pre-existing and the introduced, that presented users with a means of witnessing and positioning themselves in relation to change. This book demonstrates the ways in which rebuilt structures, in the dichotomy between their continued existence and their alteration, affected understanding of one’s place in a temporal continuum in terms that were directly, somatically experienced by those who encountered them.

Rebuilding and Restoration in Historical Perspective

My study takes us into the worlds of those who lived in the Roman and early Byzantine empires to examine the phenomenon of architectural rebuilding from their perspective. I am principally concerned with what their revised architecture reveals about the built environment’s role in shaping lived experience of temporality and change, but it is important to approach that deep past with a self-awareness about our own world’s perspectives and biases, especially as they pertain to the often fraught responses to architectural damage and restoration. For this, the recent destruction of a historic landmark and the responses it has engendered are illustrative.

It is now once again possible for both churchgoers and tourists to visit the cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, restored in short order after the devastating fire of 2019 (it reopened as scheduled on December 7, 2024 with a ceremony that included chant of the Te Deum originally planned for April 15, the fifth anniversary of the start of the fire).Footnote 1 The blaze at the centuries-old cathedral that was broadcast around the world in real time on April 15–16, 2019 expanded debates about how best to respond to architectural destruction beyond the desks of architects and bureaucrats and into international, public discourse (Fig. I.1). The sides boiled down to two broad camps: traditionalists (advocating restoration of the church more or less “as it was” before the fire) vs. architectural progressives (who envisioned a structure revised though innovative design and/or materials to reflect our current age).Footnote 2 Despite the announcement of an international competition that attracted a host of creative designs from international firms, it turns out the traditionalists, supported by the weight of public opinion, have come out ahead.Footnote 3

Figure I.1 Burning of the roof and spire of the Cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris, on April 15, 2019

The Parisian fire reminds us that destruction events force the issue of making decisions about historic buildings and engaging with their temporal orientations.Footnote 4 One needs to decide which “direction” any rebuilding project should go (including whether it should happen at all). The terms of the design debate waged in the aftermath of the twenty-first-century conflagration at Notre Dame are embedded in modern, Western sensibilities toward historic monuments. That position sees the value of the structures as connections to the past yoked to their appearance as past (i.e., not modern) which in this case is doubly loaded by the cathedral’s central position in conceptions of both national and religious identity. Even when particulars are contested, we tend to want our historic buildings to look and feel historic so that their “other-time-ness” is palpable and presents an experiential means of accessing the past. This is what confers what we read as authenticity.

At the same time, our sense of the historically “authentic” does not necessarily mean historically “accurate.”Footnote 5 We expect a materially perceptible sense of time’s passing, some form of patina, from historical monuments. An appearance of having aged is central to what makes them affective, capable of engendering emotional response and connection, what Alois Riegl influentially characterized as a monument’s Alterswert, rendered in English as “age value,” and it can be in conflict with their value as historical evidence (the “historical value,” or historische Wert, in Riegl’s typology).Footnote 6 If wiped clean of visible signs of aging, we may perceive a monument or object to be “soulless” or “fake” (i.e., inauthentic), as witnessed in the frequent criticism or downright outcry over conservation projects seen to render historical monuments too bright, too clean, too flat. A classic example is the Sistine Chapel cleaning of 1980–94, and the frequent refrain also surfaced in discussions over the recent Notre Dame project.Footnote 7 Interventions deemed overly sterile offend our sensibilities of how a historic monument should look, and they seem to rob it of some aspect of its power (by which it is usually meant that they prohibit that which is old from conforming to our ideals about the past).

But it is essential to recognize that such ideas and values are not universal, nor do they surface only at moments of catastrophic destruction.Footnote 8 Revering an old building’s signs of age grew out of debates waged both in print and in the material appearance of real buildings that picked up speed over the course of the nineteenth century.Footnote 9 The Cathedral of Notre Dame was in fact one of the pivotal monuments through which this contest played out, standing at the heart of the wave of romantic medievalism that fueled Victor Hugo’s novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame (French original: Notre-Dame de Paris, 1831), which in turn affected the conception and reception of the ideas of Jean-Baptiste Lassus and Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, the central figures behind the nineteenth-century restoration of the Parisian cathedral.Footnote 10 They advocated for the unity of the appearance of a monument which frequently involved the new fabrication of lost elements (which in this case included Viollet’s design of the wood and lead spire that so dramatically plunged from the building in flames in 2019 and had replaced, at a taller scale, the thirteenth-century timber spire dismantled at the end of the eighteenth century), a position that ran counter to the anti-restorationist principles of other contemporaries, including John Ruskin in England.Footnote 11

Such competing views on the authenticity of restoration work would have been quite foreign to those living in the Mediterranean in the first centuries CE. Recent scholarship has demonstrated that, on the one hand, in Roman literature, ruins of ancient cities could be powerfully evocative and advance moralizing ends, functioning as Catherine Edwards puts it, “as both warning and consolation,” to “move those who do not actually witness them.”Footnote 12 At the same time, on the other hand, Romans did not generally judge harshly rebuilding projects whose design introduced innovations or whose materials strayed from those used in the structures that they replaced.Footnote 13 They do not appear to have shared the modern appreciation for weathering and signs of time’s damage that Riegl dubbed “age value,” and as Richard Jenkyns put it, they for the most part lacked “the feeling that the scars and wrinkles of age were a proper part of a building’s maturation.”Footnote 14

But though Romans didn’t generally set out to restore old buildings along the lines we do, they too grappled with challenges posed by destroyed historical structures, deteriorating urban fabric, and aging infrastructure. Catastrophic destruction events as well as more gradual damage required response, and for the ancients, rebuilding projects were occasions for spotlighting attention on old structures and the people, events, and values with which historic buildings were associated (or could be made to be). Though the terms and effects of ancient rebuilding projects differ in significant ways from our own, architectural interventions on pre-existing buildings instantiated and communicated information about the past and present of particular places, sites, and structures. Once the rebuilding work was complete, when the scaffolding came down and the workmen had left the site, the “re-finished” building redefined users’ understanding of the site’s age, history, and present significance.

The Illusion of the Finished Building and the Static City: Ways of Writing – and Experiencing – Architectural Histories

In this book I contend that, because of this capacity (or liability, depending on one’s perspective) to variously reference and be seen in juxtaposition to their former selves (and perhaps hint more pointedly at their potential futures), rebuilt buildings operate in significantly distinctive ways from new construction projects. By altering the perception of their origins and life cycles in the eyes (and bodies) of subsequent users, rebuilt buildings challenge the structures and conventions that condition our approaches to history in general and architectural history in particular.

This is because we tend to write ancient architectural history in terms of the construction of new buildings. The task involves recovery and recuperation of old monuments from decades, centuries, or millennia of post-construction transformation. In temporal terms, this mode of history production analyzes individual buildings as products of a particular time and place. It privileges singular moments of production as essential to understanding the position of specific structures within larger sequences, such as histories of vaulting, evolutions of building types, and so on. Such series and lineages are the building blocks of analysis of developmental patterns of architectural form, technology, and style. Thus, this type of architectural history identifies patterns of development between buildings as they have been plotted on a timeline, but it generally does not address changes that individual structures undergo and the ways those changes impacted later audiences. Moreover, in focusing on new, completed buildings it implicitly establishes a temporal hierarchy that privileges originating moments (and often the individuals and cultures contemporary to them) and relegates buildings’ later intervenors and users to secondary status (or worse). Modifications or other less-than-total reworkings are generally overlooked or dismissed, seen to detract from the central object of the study, the “original” structure. A fully reconstituted building (i.e., one that replaced an earlier, destroyed one on the site) may be identified as a rebuild, but to all intents and purposes it is most often treated as a new project. At issue is no less than how we tell the history of buildings – and what histories we credit buildings with telling.

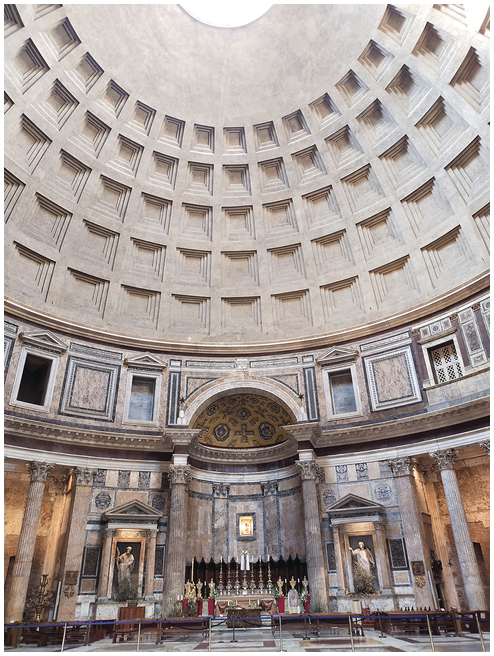

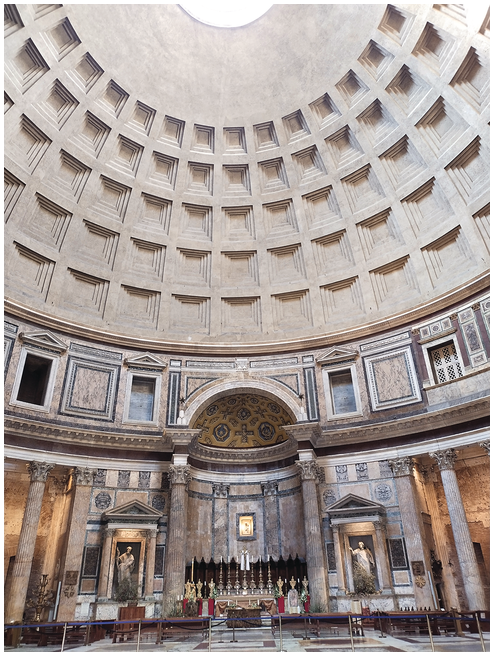

While the larger project of this book aims to outline widespread Roman strategies of time-shaping through architectural modification, I want to set the stage with two of the most recognizable, studied, and oft-quoted ancient and late ancient buildings in the Mediterranean, Rome’s Pantheon and Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (Istanbul) (Figs. I.2–I.5), to illustrate the temporal conventions that underpin our modes of architectural history writing.Footnote 15 Both buildings are wondrously extant and still in use. They were both also replacements of earlier iterations on the site: The original Pantheon was constructed in the Augustan period by Augustus’ lifelong friend and eventual son-in-law, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, and the first Hagia Sophia was consecrated in 360 CE by Constantine’s son Constantius II in the generation after his father’s foundation of the new capital on the Bosporos. However, in our textbooks and more specialized studies, even as mention is made of the existence of destroyed structures that once occupied the spot, it is as products of the second and sixth centuries CE, respectively, that the Pantheon and Constantinople’s “Great Church” (μεγάλη ἐκκλησία, as it was regularly called for much of its life) are tethered to singular patrons, Hadrian and Justinian, and imbued with canonical status.

Figure I.2 Pantheon, Rome (present state)

Figure I.3 Pantheon, interior, Rome (present state)

Figure I.4 Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

Figure I.5 Hagia Sophia, interior, Istanbul

Nevertheless, it is important to bear in mind that categorizing the structures as such – or only as such – artificially and deceptively flattens the temporal multidimensionality that was, and continues to be, fundamental to their cultural currency. It entails acts of excision to think away later additions or alterations and acts of recuperation of actual or hypothesized lost elements (through archaeology, textual and archival sources, or comparanda-based extrapolation) to retrieve what is prized as the “original.” The Roman Pantheon we study, for example, has been mentally swept free of the liturgical furnishings and devotional images that have accreted within since its dedication as a church to St. Mary by Boniface IV in the early seventh century.Footnote 16 In our reconstruction of the high imperial Roman monument, gone too are the post-classical funerary installations of Raphael and other sixteenth-century artistic luminaries and of Italy’s first modern kings, Vittorio Emanuele II and his son, Umberto I.Footnote 17 We no longer have to think away the seventeenth-century bell towers (which had in turn replaced the original thirteenth-century one) since those were actually removed in the restoration campaigns of the 1880s in order to render the structure more classical and less church-like, a fact that illustrates the extent to which desire for recouping lost or “corrupted” originals can impact the physical fates of structures and drive modern restoration practices of the sort evoked in the previous section.Footnote 18 Similarly, efforts to access Justinian’s Great Church in the Byzantine capital entail mentally subtracting the figural mosaics added to its upper surfaces over the middle and late Byzantine centuries, as well as the Ottoman minarets, minbar, mihrab, and the great calligraphic discs suspended from the dome that accompanied its centuries-long use as a mosque, the Ayasofya Camii (Figs. I.4–I.5).Footnote 19 Other long-lost internal, space-defining and ritual-structuring features of the Justinianic church, including ambo, solea, and ciborium, can only be approximated from literary sources.Footnote 20 It is through such scholarly acts of imagining out post-construction elements and resupplying lost original ones that we gain access to, indeed construct on paper if not materially, an image of Hadrian’s Pantheon and Justinian’s Hagia Sophia.

Nevertheless, though still far from the norm, scholars have in recent decades ascribed increased value to post-classical chapters of ancient structures and devoted increased attention to process over product. In this convention-bucking approach to architectural history, buildings’ material transformations and continuities offer evidence of their changing cultural and political roles for different historical audiences. Some research in this vein draws on models of the longue durée promoted by Fernand Braudel and other historians of the Annales School to point attention to the explanatory force of long-term, structural change (e.g., economic, institutional, environmental).Footnote 21 In adopting a telescopic temporal lens and analyzing the histories of individual buildings through time (diachronically), such work shares a focus on questions that transcend discrete moments of architectural production, and privileges instead the investigation of transformation and change over time.Footnote 22 It is through these scholarly efforts that we now have a clearer understanding, for example, of the Pantheon’s appearance and status as a Christian church and its currency in cultural contests surrounding the formation of the early nation state of Italy.Footnote 23 Given its central position as the imperial and patriarchal church of the Byzantine Empire, Hagia Sophia’s post-Justinianic history has been more heavily examined than the post-Hadrianic Pantheon. Only belatedly, however, has a significant degree of attention been focused on the building’s place and appearance amidst changing Ottoman imperial politics and ceremony, or its charged position during the formation of the early nation state of Turkey when it was converted to a secular museum in the 1930s, a history particularly highlighted now with its reconsecration as a functioning mosque in 2020.Footnote 24

Yet, even with the increase in longue durée studies, there remains a critical disconnect between ancient Roman preoccupation with the historicity of their buildings and the ways that most modern scholars have approached those same built structures. In particular, architectural rebuilding has only begun to be examined as an ancient phenomenon in its own right, and we still have much to learn about its diverse strategies, local inflections, perceived effects, and changes over time.Footnote 25 Indeed, with the exception of examination of a single material practice – the reuse of architectural elements (spolia) – most scholarship that has sought better understanding of long-term transformation in the ancient built environment concentrates on histories of individual cases, whether spectacular, singular monuments, or specific neighborhoods, cities, or regions.Footnote 26 Building on the insights of this work, I subscribe to a diachronic approach to Roman and late antique architecture and to the mandate to remain ever alert to the ways early modern and modern values and interventions have tinted the lenses through which we view those earlier periods, but my aim in this project is not to reconstruct building biographies that stretch from origin points to present. Rather, eschewing the tendency to characterize post-construction histories as “afterlives,”Footnote 27 I strive to access something of emic perspectives on architectural change – how, in other words, it was experienced and understood by contemporary users – through the buildings themselves.

While Romans certainly prized and invested heavily in new construction, both in terms of the real monetary outlay of rulers, elites, and communities and in the systems of social capital that rewarded them, this book reveals the great extent to which they also recognized (and were simultaneously concerned about) what I call the openness of architecture, that is, its capacity to write and rewrite history and to (re)structure temporal patterns. Ruination, whether through fire, earthquakes, or war, as well as slower processes of decay and dilapidation, were simultaneously both causes of real concern and events that were exploited by ancient and late ancient actors to justify architectural investment and change.Footnote 28 Our approaches to architectural history can and should do more to account for ancients’ deep self-consciousness in the histories of their buildings – not only of origins, but also of destruction and reconstruction – as well as architecture’s potential for projecting or ensuring secure futures. A central goal of the present book is thus to draw more attention to Roman and late antique sensibilities toward buildings not only as finished products but also as unstable things, things that were susceptible to change and that bore the capacity to alter chronologies as well as nonlinear temporal experiences.

Temporalities and Roman Architecture

Work from a variety of disciplinary angles has been expanding our understanding of personal, collective, and cultural times – plural! – and of the different patterns and velocities of those experiential temporalities that operate distinctly from yet are intertwined with quantified time (i.e., subdivided into regular units such as minutes, hours, or days).Footnote 29 But while scholarly investigation of historically and culturally diverse perceptions of time has been a multifarious project, with the important exception of memorial studies (to which I will return shortly), examination of time and temporality in the ancient world has largely been a textual endeavor.Footnote 30 This work has provoked new and deeper sensitivity to the radical change in temporal regimes affected through state control and religious transformation. Scholars of antiquity have drawn attention, for instance, to the crucial social-structuring functions of various ancient systems of time-marking, counting, and synchronizing diverse locales, including quadrennial Olympiads, the accumulative sequences of the Seleucid era, Roman years named after the two eponymous consuls holding annual office, provincial years, and Byzantine indiction cycles (the sequentially numbered 15-year units originally tied to tax-collection schedules).Footnote 31 Alongside such enumerated (or named, in the case of consular dates) sequences of years, larger era-scale divisions of time, such as the technological and moral sequences of metallic ages (bronze, iron, etc.), pre- and post-lapsarian times, or the Roman saecula, set temporal boundaries that both informed understanding of one’s place in time in relation to other periods and were discursively malleable (witness Augustus’ new Golden Age).Footnote 32 Jewish and Christian apocalyptic thought ushered in a new temporality of “end times” that converted one’s life into an extended period of “waiting,” while the recalibration of historical time on a universal, and Christianized, scale in the deeply influential synchronizing project of Eusebius drafted a new, Christian form of teleological history.Footnote 33 Christian thought on time, eternity, and life after death, as well as Christian ritual and devotional practices – from the liturgical calendar’s negotiation of “mobile” (e.g., Easter) and “fixed” (e.g., saints’ days, the Nativity, and Epiphany) feasts to daily set hours of prayer and ascetic ideals of imitatio Christi – transformed the rhythm and experience of one’s imagined temporal horizons and everyday experience.Footnote 34

Nevertheless, despite this rich body of literature on ancient time, the active role of material culture as both a means of manipulating temporal patterns and an agent that shaped users’ perceptions and understanding of time has remained sidelined. Where examination has included more direct and systematic examination of material culture has been in the narrower sense of relationship to the past through the cultivation of what has been dubbed cultural or collective memory.Footnote 35 This research has led to deeper sensitivity toward the distinctly material and spatial terms through which monuments contributed to the formation of broad and localized group identities (e.g., as Romans, as Ephesians, as household members, as Jews, as Christians) and the construction of memorial and/or sacred landscapes (e.g., the Forum Romanum, the Holy Land).Footnote 36 Yet, memorials strictu sensu comprise a relatively narrow subset of architecture, even if they are seen to include both monuments purpose-built to commemorate (e.g., tombs, war memorials, honorific statues) and those that only come to take on memorial roles through later associations with particular individuals or events (e.g., historic homes, battlefields, sites of epiphany).Footnote 37

In this book, I contend that the “time-making” role of the Roman built environment extends well beyond the purview of purpose-built commemorative monuments. On the one hand, public buildings of all sorts were imbued with a memorial function to a degree familiar but nevertheless far exceeding and differently charged than those carried by the building names and public inscriptions in our modern world. This is due to the distinctive social mechanics of patronage behind Roman public architecture and to the honorific discourse and calendars of communal celebration in which that patronage system was embedded (more on this in Chapters 1 and 2). In addition, patterns of long-scale intervention, reuse, and reinvention of the fabrics of cities operate along modalities that may relate to those of written sources (whether historical or literary), but in their material, visual, and spatial qualities are also fundamentally distinct from them. This pastness, as Shannon Lee Dawdy has written, is “a quality that is sensed (not narrated, not remembered) … It refers to the sensation of being in the presence of a lifeworld that existed prior to the present.”Footnote 38 On my reading, architectural rebuilding brings temporal consciousness to the surface, whether by explicitly linking construction work to an external timeline (as with foundation and rebuilding inscriptions), by forging connections and comparisons between select times (i.e., projects framed as continuities or ruptures that “activate” some pasts and not others), by presenting a sense of former days, or by shaping expectations for future durability or change.

I return now to our two case-study sites, the Pantheon and Hagia Sophia, to illustrate in particular two timeline-bending aspects of architectural rebuilding, the analysis of which will be developed further in the book chapters that follow. The first is the notion of co-presence. In contrast to the linear sequences of elements (from construction materials to inscribed texts and surface decoration) that our academic typologies construct, in long-used and adapted or revised structures, select aspects of the old regularly existed alongside the new, at the same time. Anthropological and philosophical discourses draw attention to material culture’s variable durabilities and patterns of use, as shaping on the one hand relative scales of time and on the other a temporality of “co-presences” or of “simultaneity,” given that, as George Kubler put it, “the simultaneous existence of old and new series occurs at every historical moment save the first.”Footnote 39 In short, this thinking points to the connections and contrasts between differently “timed” elements in our surroundings and to our embodied engagements with those material elements as giving rise to varieties of social and cultural experiences of temporality, which are separate from though often in dialogue with the narrative time of literature and history and sequential time that is measured and marked through intervals of evenly spaced units by devices such as clocks and calendars.Footnote 40 Second, even when older chapters or iterations of a structure no longer exist in material reality, they can be remembered or conjured by later replacements in ways that defined that earlier building for later audiences. For those historical actors, the pasts they understood their buildings to have had were culturally and socially significant, whether or not accurate by the standards of modern empirical study.

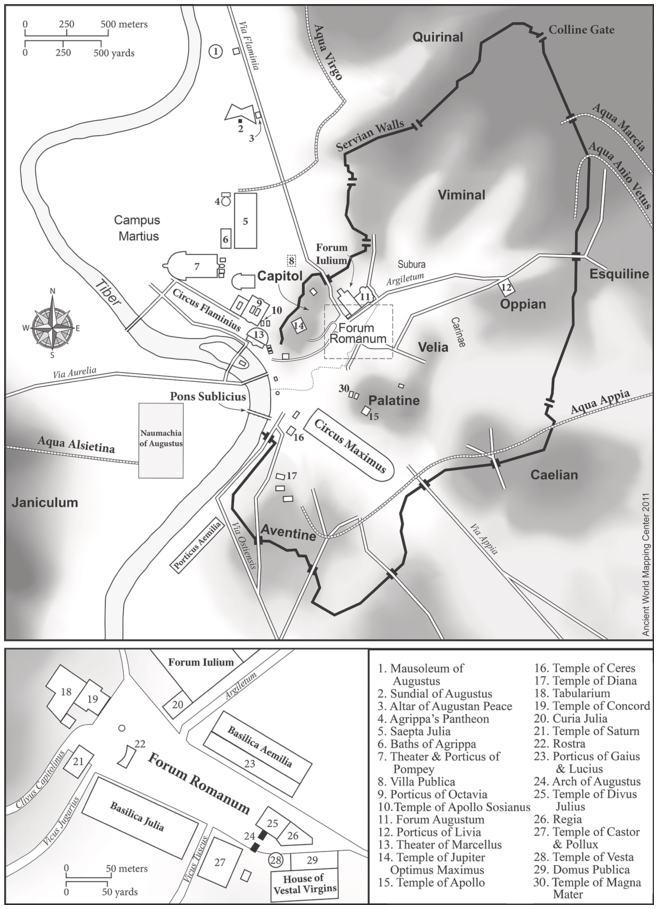

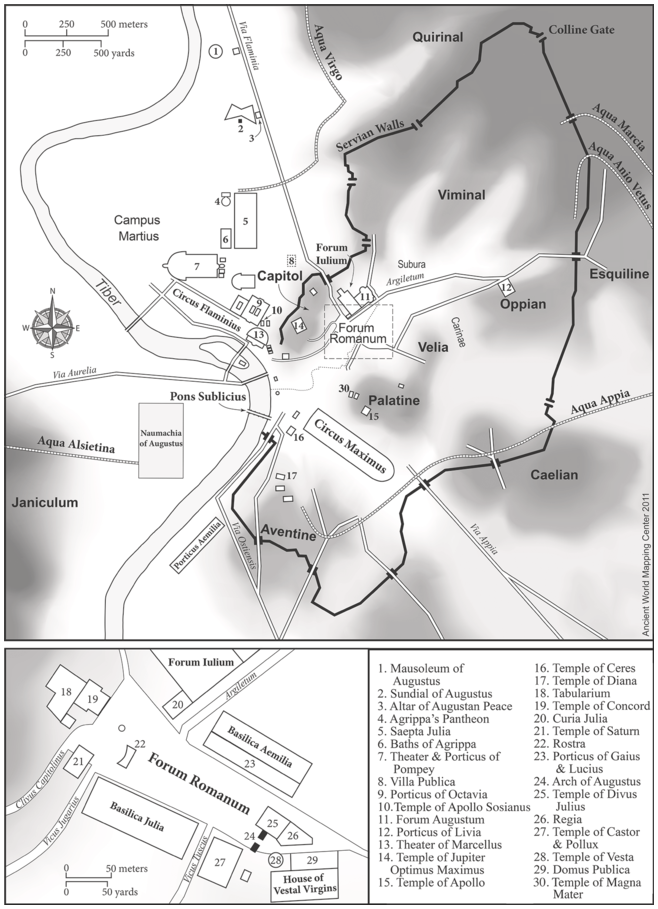

The Pantheon’s mediation between tradition and novelty famously appears front and center on its facade (Fig. I.2). In a move that might strike modern sensibilities as one of marketing or false advertising, the structure is not what it explicitly purports to be in the massive letters that were emblazoned on its face in the Roman period and renewed in the late nineteenth century (Figs. I.2 and I.6). Here we read what appears to be the building’s own origin story: “Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, consul for the third time made (it),” a bold, straightforward statement of architectural authorship by the right-hand man and son-in-law of the Emperor Augustus.Footnote 41 However, we know from the testimony of ancient historians and from manufacturers’ marks on the Pantheon’s brick construction materials that the building on which the monumental text is written was not constructed by Agrippa, but rather completed under Hadrian (likely started under Trajan) in the second century CE.Footnote 42 Ancient sources also testify, however, that Trajan’s/Hadrian’s structure replaced one on the same spot that had been built there by Agrippa in the Augustan period, had been burned in a fire in 80 CE, then had been restored by Domitian (the extent of the Domitianic interventions is unknown), and finally had been catastrophically destroyed during Trajan’s reign in 110 CE by another fire, this time attributed to lightning.Footnote 43 Though our knowledge about the appearance of the Agrippan building and the extent of the damage it suffered in the year 80 is hampered by the still-extant superimposed structure, excavations of the 1990s have revealed that its porch was basically the same size and faced north as the current building does and therefore would have looked across the low-lying plain of the Campus Martius to the Mausoleum of Augustus with which it was aligned (Fig. I.7, nos. 4 and 1).Footnote 44

Figure I.6 Pantheon, detail of facade inscription: Hadrianic inscription above (letters restored in nineteenth-century bronze), Severan restoration inscription below

Figure I.7 Map of Rome at death of Augustus in 14 CE

Figure I.7Long description

In Campus Martius, the upper left quadrant of the large plan has 30 labeled features. They include the following, roughly from top to bottom. Aqua Virgo, Via Flaminia, 1. Mausoleum of Augustus, 2. Sundial of Augustus, 3. Altar of Augustan Peace, 4. Agrippa’s Pantheon, 5. Saepta Julia, 6. Baths of Agrippa, 7. Theater and Porticus of Pompey, 8. Villa Publica, 9. Porticus of Octavia, 10. Temple of Apollo Sosianus, Circus Flaminius, 13. Theater of Marcellus. Within the circuit of the Servian Walls, labeled features include, from roughly top to bottom: Viminal Hill, Subura, 11. Forum Augustum, Forum Iulium, Argiletum, 12. Porticus of Livia on the Oppian Hill, the Capitol Hill on which is 14. Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the Forum Romanum, for which see detailed plan below, the Velia, the Palatine, on which is 30. Temple of Magna Mater and 15. Temple of Apollo, Circus Maximus, 16. Temple of Ceres, 17. Temple of Diana, and the Aventine. Outside the line of the Servian Walls, in the north, are labeled, the Quirinal and the Colline Gate, to the east, from top to bottom, the Aqua Marcia, Aqua Anio Vetus, Esquiline, Aqua Appia, to the south, from right to left, the Caelian, Via Appia Via Ostiensis, Porticus Aemilia, to the west, the Tiber River and Pons Sublicius, and left of the river, from south to north, the Janiculum, Aqua Alsietina, Naumachia of Augustus, and Via Aurelia. The detail plan of the Forum Romanum includes the following labeled structures, clockwise from top. Forum Iulium, 20. Curia Julia, Argiletum, Basilica Aemilia, 23. Porticus of Gaius & Lucius, 25. Temple of Divus Julius, 26. Regia, 29. Domus Publica, House of Vestal Virgins, 28. Temple of Vesta, 24. Arch of Augustus, 27. Temple of Castor & Pollux, Vicus Tuscus, Basilica Julia, 22. Rostra, Vicus Jugarius, 21. Temple of Saturn, Clivus Capitolinus, 19. Temple of Concord, and 18. Tabularium.

All that said, it seems unlikely that the facade inscription was intended as an explicit deception, even if for much of the Pantheon’s later history the text was taken at face value.Footnote 45 Given that the previous building on the site and the fires that twice damaged it were known to ancient historians, and no doubt to contemporary Roman inhabitants, something more subtle, less literal seems to be going on here. Some scholars have suggested that the text Hadrian installed on the completed building replicated that of the lost Augustan-era structure as a pious and humble retrospective gesture, though other scholars have been more circumspect on this point.Footnote 46 Since the Agrippan one is gone, we cannot be certain, but it is at least plausible that the Hadrianic text written in the spare style of other Agrippan inscriptions could have been an archaizing invention.Footnote 47

Whether or not the Hadrianic text literally copied that precursor’s dedication inscription, it is clear the text intentionally manipulated the temporal associations of the second-century structure to (re)position it in relation to the Augustan age, even as both the physical inscription and the entablature it adorned postdated the Augustan construction by over 125 years. Moreover, it is highly unlikely that the Agrippan text looked like the Hadrianic one since, as Mary T. Boatwright has observed, “the 70-cm height of the current letters is more than double that known of metal-letter building inscriptions of Augustus: for instance, the letters on the inscription of Mars Ultor were 23cm tall.”Footnote 48 Thus, even if Hadrian’s inscription did reproduce the earlier text, it almost certainly translated it into a different material idiom that heightened, even exaggerated, the Augustan reference. Equally significantly, by evoking the Agrippan structure and simultaneously making no direct reference (at least none that we can perceive) to its Domitianic predecessor, the second-century Pantheon bends linear time to make the now-ancient Augustan age “present” while simultaneously leapfrogging over and suppressing the more recent chapter of architectural intervention.Footnote 49

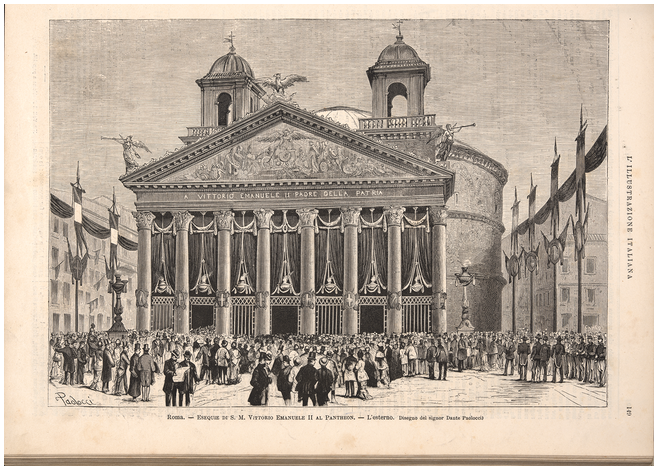

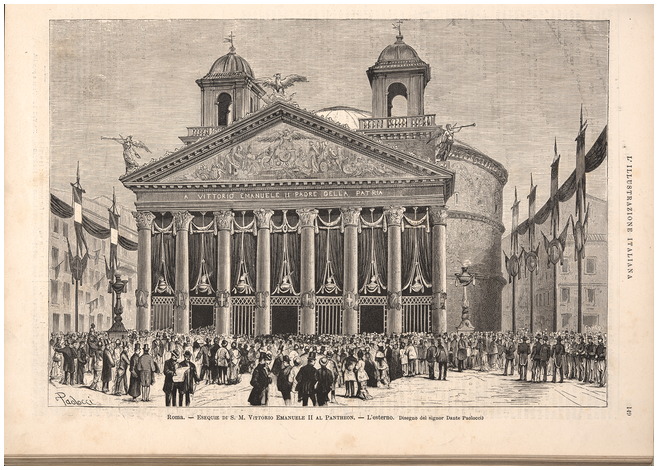

Nor was it the last time that the Augustan connection was reactivated and thereby reinvented at and via the Pantheon’s public-facing inscriptions. Multiple interventions across its history as an active structure constituted repeated efforts to engage the building as a powerful time-shaping engine. One of these commemorated restoration work that was carried out in 202 CE by the Emperor Septimius Severus and his son Caracalla and was placed on the Pantheon’s architrave directly below the Hadrianic text, in immediate visual dialogue with it, though at a smaller scale and not bronzed (it no doubt would have been painted; see Fig. I.6).Footnote 50 Since we have no evidence that the facade was recarved when, roughly 400 years later, the Pantheon was transformed into a church, it may be that both of these imperial inscriptions were still perceptible, but eventually the metal letters of the Hadrianic dedication went missing, either intentionally or unintentionally detached, leaving their negative impressions to communicate the words. It was only in the nineteenth century, amid renewed political interest in the building as a symbol of state, that large visible letters were again set up, but when they were, they did not at first resemble the ancient text except in scale. The occasion was the official funeral of Vittorio Emanuele II, for which, in a tense détente with the Church, and despite the deceased king’s excommunication for the army’s march on Rome, it was agreed that the ecclesiastical building would be transformed. The arrangement included a massive, if temporary (though widely disseminated through images in the patriotic press), inscription installed on the facade that hailed him, in Italian, as father of the country (“Padre della Patria”), an exact translation of Augustus’ title of “pater patriae” (Fig. I.8).Footnote 51

Figure I.8 Engraving of the Pantheon exterior decorated for the secular, state funeral exequies of King Vittorio Emanuele II, February 16, 1878, published in L’Illustrazione italiana (1878, 149)

Finally, it was in the context of subsequent contestation over the permanent location of Vittorio Emanuele’s royal tomb (which in the end was erected inside the Pantheon despite the Vatican’s protestations) that the restored letters we see on the facade today were installed in 1895 (Fig. I.6). Forged from 800 kg of bronze supplied by the Ministry of War and adorning a church structure recently “re-Classicized” through the removal of its bell towers just over a decade earlier, the re-metalled inscription declared the character of the Pantheon as secular symbol of the state, vividly reasserting the monument’s association with the Augustan era through the massive re-evocation of Agrippa’s patronage.Footnote 52 The Severan inscription below received no such parallel renewal. The form – whether textual, material, or both – of each of these third- to nineteenth-century inscriptions was conditioned by and responded to the pre-existing Hadrianic one that hailed Agrippa’s act of construction. They constituted, in other words, responses to that Augustan age and drew on it for their own currency while simultaneously pointing renewed attention to the original Augustan building and conferring upon it the status of model, or benchmark.

Hagia Sophia too, as we see it today, was a replacement of earlier iterations of the structure that had been damaged and restored on multiple occasions before the construction of Justinian’s Great Church, and it demonstrates further time-bending possibilities that can accompany architectural rebuilding. The original dated back to the early decades of the capital. Though we cannot be sure whether Constantine himself had started or even envisioned a church to “Holy Wisdom” (it is not mentioned in Eusebius’ biography of the emperor), most scholars today think it unlikely and follow the authority of the Chronicon Paschale and other early Byzantine sources who report that the church was inaugurated under his son Constantius II in 360.Footnote 53 Early in the next century (404 CE) it burned in a fire that broke out amid the tumult surrounding the expulsion of the bishop, John Chrysostom, by the emperor, Arcadius.Footnote 54 Arcadius and his heir, Theodosius II, presided over the rebuilding of Hagia Sophia, which was inaugurated on October 10, 415.Footnote 55 It was this Theodosian iteration of the church that was destroyed in Justinian’s reign by the fires sparked in the days of widespread unrest known as the Nika riot that devastated much of the central part of the city, including parts of the imperial palace, Hagia Eirene, and the Senate House (again) in January, 532.Footnote 56

In comparison to the pre-Hadrianic Pantheon, our knowledge of the pre-Justinianic Hagia Sophia is more limited, but it does appear that the rebuilt Hagia Sophia maintained nearly the same orientation and a parallel topographic relationship to the facing street and to the nearby church of Hagia Eirene as its immediate predecessor on the site had. Excavations carried out in the 1930s on the west side (i.e., in front) of the church revealed the marble pavement and several columns of the entrance portico of the Theodosian-era church below the Justinianic-period atrium (Fig. I.9).Footnote 57 These remains confirm the consistent street access of the church in its fifth- and sixth-century iterations, even as the excavated columnar courtyard suggests an apparent classicism of the earlier church’s design (it is thought likely that it was basilican in plan) that was rejected in Justinian’s rebuilt church.Footnote 58 For, like the second-century Pantheon, the sixth-century Hagia Sophia exhibited a bravura architectural design – it was crowned by a massive dome, but in this case one whose base was pierced by a ring of forty windows so that it appeared, as famously reported in a contemporary ekphrasis by Procopius, to be suspended from heaven rather than held up by architectonic supports.Footnote 59 Thus, from an experiential, architectural design standpoint, we can comfortably say that in its day Justinian’s Great Church was ultra-modern and would not have been mistaken for a centuries-old structure.

Figure I.9 Remains of portico of Theodosian Hagia Sophia at west end of church excavated in the 1930s

Indeed, the degree to which the rebuilt Hagia Sophia pointed backward to its earlier chapters at all is difficult to assess but seems slim. We have no evidence, for example, of a dedication inscription on the mid sixth-century church that might have either referenced, obfuscated, or blatantly neglected the preceding buildings on the site or their imperial patrons.Footnote 60 Some of the vast amount of marble used in Justinian’s church seems to have been repurposed from elsewhere, but we cannot be sure that it was from the earlier church on the site.Footnote 61 The only secure, aboveground holdover from the earlier iteration was the round annex building known as the skeuophylakion (treasury) on the northeast side of Hagia Sophia. The structure appears to have largely survived the destruction wrought by the Nika uprising and was repaired and expanded as part of the construction of the Justinianic complex, though whether it was used as a treasury in the earlier complex as it was in later times is uncertain.Footnote 62

Thus, while it would have been well known to contemporary audiences that Justinian’s architectural masterpiece was a replacement of the older church destroyed in the civic unrest of 532, from available (admittedly incomplete) evidence it does not appear that the structure trumpeted connections to its earlier imperial patrons. If this was indeed the case, then it would have been in pointed contrast with a different building, one that before the inauguration of Justinian’s Hagia Sophia had been the largest church in the Byzantine capital. The church that held that distinction was the lavish basilica of Hagios Polyeuktos, built in the years before the Nika riot by Anicia Juliana, who was a descendant of the Theodosian line through both her parents, wife to a husband whom a riotous crowd had attempted to declare emperor, and mother of a son who served as consul very young and for whom she seems to have had imperial designs.Footnote 63 Hagios Polyeuktos too was a replacement for an earlier church on the site, but it was not shy about declaring this status. An extensive and elaborately carved verse inscription that surrounded the church celebrated Anicia Juliana’s patronage and cast the current structure as a rebuild of a church that had originally been dedicated by the patron’s great-grandmother.Footnote 64 We will meet this church and its inscription again (in Chapter 6), but here it is useful to point out that, in addition to her own ancestors and the biblical King Solomon, the verses inscribed on her church drew explicit connection between Juliana’s project and the construction works of both Constantine and Theodosius, and Constantine also evidently starred in a mosaic decoration in the complex as well.Footnote 65

Justinian’s apparent downplaying of any explicit connections to Hagia Sophia’s previous patrons from the Constantinian and Theodosian lines may thus also have been motivated by the desire to distance his own rebuilding project from that of Juliana, in the rich decorative and epigraphic program of which such lineages were central.Footnote 66 Justinian’s church, in other words, played off both its contrast with the immediately preceding structure on the spot (even if it’s difficult for us now to access the extent of this) and can be seen to do so as part of a competitive discourse between contemporaries who were using the explicit opportunities that rebuilding afforded to cast comparison backward to earlier builders – or soft-pedal such connections – as a form of cultural capital.

It is also the case, however, that patrons cannot necessarily control the history lessons that their architecture ends up relating to their audiences. This is especially true as enduring and modified buildings are encountered by later viewers. The stories that subsequent generations tell of their city’s old buildings reveal architectural construction, destruction, and rebuilding events to be particularly labile moments in which distant times are connected to present, witnessable conditions. Though nowadays, as we have seen, most scholars believe that Hagia Sophia did not yet exist in Constantine’s early fourth-century capital city, it turns out that medieval sources were not so uniform in their discussion of the church’s origins.Footnote 67 Constantine appears as either the builder or the initiator of the first Hagia Sophia in the wildly popular historical tales of George Hamartolos (also known as George the Monk), first penned in the ninth century, and in a number of other ninth- and tenth-century narratives, including the text known as the Narrative about the Construction of the Temple of the Great Church (Diegesis) that was later incorporated into the collection known as the Patria of Constantinople.Footnote 68 The late eleventh- or early twelfth-century universal history by George Kedrenos, compiled from earlier sources, has Constantine building the original Hagia Sophia and donating gem-encrusted Gospel books to it; his son Constantius is then said to have finished as well as rebuilt (there are inconsistencies in the text) and reconsecrated it in 360.Footnote 69 Gilbert Dagron attributed this confusion on the part of medieval authors to the entry in the early seventh-century Chronicon Paschale for the year 360, which opens with an indication of the consecration of the Great Church on February 15 of that year and then links the event to the seating of the bishop, relating that “not many days after the enthronement of Eudoxius as bishop of Constantinople, the inauguration of the Great Church of the same city was celebrated after a little more than 34 years since Constantine, victorious and venerable, laid the foundations.”Footnote 70 The foundations in question, Dagron argues, were not those of the church, as taken by later authors, but of the city of Constantinople, and subsequent modern scholars have followed suit in recognizing the inaccuracy of those medieval texts on the initiation of the Great Church. At issue, however, in this scholarly correction to the record is not just that Kedrenos and the other later sources “got it wrong.”Footnote 71 Though we no longer countenance a Constantinian hand in the original church, it is nonetheless the case that the building did evoke his memory and patronage for many later audiences. Likewise, as Alessandro Taddei observes, the seventh-century Chronicon’s naming of Constantine and not Constantius “represents a significant step in the progressive effacement of the figure of Constantius from the historical record … [which] evidently had its origins in the perception of the figure of Constantius II as an ‘Arian ruler’.”Footnote 72 Thus, rather than dismissing the later sources as unreliable, I suggest we consider them significant for revealing the terrific degree of latitude that architectural construction work, especially the act of rebuilding, gave to write and rewrite histories.

It is also tempting to view a famous tenth-century mosaic installed in Hagia Sophia in light of this heavily inflected medieval connection of the church to the figure of Constantine (Fig. I.10). The mosaic was set in the lunette over the entrance to the narthex from the southwest vestibule, a space that recent investigation has demonstrated was added sometime between 565 and 574 (i.e., shortly after Justinian’s death) to serve as the entrance vestibule to the patriarchal palace and which later, in the Middle Byzantine period, when the image was installed, served as the imperial entrance to the church (it was here on certain major holidays that the emperor doffed his crown and joined the patriarch before proceeding into the church).Footnote 73 The mosaic shows fourth- and sixth-century emperors Constantine and Justinian in parallel if not quite equal terms.Footnote 74 They are dressed as contemporary, Middle Byzantine sovereigns and bear gifts to the splendidly enthroned Virgin and Child in the center of the composition. Justinian appears in the privileged position on the Virgin’s right, is labeled “Justinian, the famous emperor,” and offers a representation of his domed church, while Constantine, who carries a representation of the walled city of Constantinople, is both rendered in larger scale and given a larger-sized and more fulsome inscription: “Constantine, the great emperor among the saints.”Footnote 75 The image places the two historically separated emperors together in the same pictorial space and time (or rather heavenly non-time) as the figures of the Virgin and Child, thanks, in the logic of the image, to their acts of building – and rebuilding.Footnote 76

Figure I.10 Mosaic of Virgin and Child enthroned, receiving gifts from Justinian (left) and Constantine (right), tenth-century, southwest vestibule, Hagia Sophia

Until late nineteenth-century empirical study of brickstamp and archaeological evidence from the Pantheon in Rome, early modern and modern sources attributed the construction of the extant version of the Pantheon – the one we now know to be Trajanic/Hadrianic – to the Augustan period based on the authority (believability) of the facade inscription.Footnote 77 In a similar fashion, medieval and later audiences wrote Constantine into the early history of the Hagia Sophia church (and then mosque), a connection that I expect fueled and was reinforced by the later image of the city founder paired with Justinian that was added to the church in the Middle Ages. Our modern scholarly tools have debunked the literal truth of these origin claims and revised the timelines we now construct for the buildings, but it is clear that multiphased buildings such as these, especially ones carrying such political and religious import, were understood as multitemporal entities and that the contours of that multitemporality could be both fluid and contested – in other words, that they could be in and of the viewer’s present and could simultaneously be a vehicle for casting different narratives and temporal connections toward different pasts.

Nowadays, as we’ve seen, the Pantheon and Hagia Sophia are regularly hailed in popular and scholarly literature alike as the two best preserved ancient Roman and early Byzantine structures. And they are terrifically well preserved, but imagining them as Roman buildings of the second and sixth centuries CE, respectively, requires not only thinking away centuries of intervention and reinvention, but also diminishing their status as replacements and downplaying any relationship they may have forged in antiquity and beyond to the earlier buildings on the site.Footnote 78 So, ought we to see the Pantheon as a Trajanic/Hadrianic building, a Severan one, an early medieval papal building, a Renaissance one, or a modern one? I’d propose that we acknowledge it to be all those things, just as the building we know as Hagia Sophia played a formative role in the experiences of inhabitants and visitors to sixth-century Constantinople, to the later Byzantine and Ottoman capital, and to the modern Turkish metropolis. In their variable relationships to their former iterations as well as in the very fact of their continued or reasserted existence and use under new social, political, and cultural conditions, buildings that have been restored or revised defy straightforward categorization as “of” one or another particular moment or age. This may appear on the one hand an obvious statement, but pursuing its implications poses a significant reorientation of our usual way of thinking and writing about historical architecture and heterogeneous built environments to understand the temporal shapes and connections that they offer and invite. I’d suggest, therefore, that alongside the empirical data that facilitate the construction of fixed timelines that are essential to our histories, we need also to pursue examination of nonlinear temporal forms of material time-making to access the kind of historicity that long-used structures could hold for their users.

While I have showcased the Pantheon and the Hagia Sophia here in this introductory chapter, I also believe the apparent uniqueness of both form and preservation of these “blockbuster” buildings hampers our appreciation of the ways in which they participate in broader cultural practices of manipulating time through architectural transformation and modification. In an effort to correct for this exceptionality bias while also avoiding superficial generalizations, I therefore adopt two strategies in this book. First of all, I anchor my analysis to the close scrutiny of a variety of diverse case-study monuments brought into comparison and conversation with each other. I strive to do so without losing the trees in the forest in order to better understand relationships between built environments and time as expressed and experienced in different places and phases of the Roman and late Roman world. At the same time, I aim to contextualize discrete rebuilding projects within a wider set of cultural practices and institutions – social, religious, moral, and political – in order to identify common mechanisms and chart how those mechanisms were deployed across the period of study. Readers will no doubt find additional examples, some of which may run counter to or extend beyond the patterns and paradigms mapped out in this book. I consider that a good thing, as my aim is not to supply a comprehensive account but to present some new observations and ideas about long-lived architecture that will, hopefully, continue to evolve as tested and explored against other sites and their audiences.

Approaches to the Times of Things (Especially Buildings): Key Concepts and Tools

My engagement with material culture situates ancient urban structures within current interdisciplinary discussions of social and cultural time by drawing on insights from multiple disciplines and approaches, including social-geography, phenomenology, and cultural-memory studies. In terms of the sources considered, the project is broadly ecumenical. I study extant architectural remains alongside dedication inscriptions, literary accounts, and numismatic evidence, but the ends to which I put these sources – that is, the questions I focus on – center architecture, exploring the ways that interaction with the built environment shaped perceptions and understandings of time. Before delving deeper into the book’s examination of historical evidence, I offer a brief introduction to some of the critical ideas and approaches not yet discussed that have informed my thinking on the issues at play in this book.

Reuse and Appropriation

Selective quotation or recontextualization of older material objects (as, for example, by transforming their spatial and material frame through architectural modification) shifts their meaning. As Robert Nelson emphasizes in an influential essay on appropriation, this is an active process, involving personal actions and decision-making, rather than a passive one of the sort that the word “influence” implies.Footnote 79 Especially productive use of such ideas has been made by scholars investigating the “cultural biographies” of objects (including not only spolia but also gifts and other kinds of transferred possessions).Footnote 80 In my own research on concepts and practices of architectural rebuilding, I find that considering renovation and adaptation as a form of appropriation, one that transforms both the fabrics and the histories of pre-existing structures, helps us see how such interventions shift and redefine meanings and roles for old buildings in the present. Particularly valuable is Nelson’s idea that appropriation often comes off as seamless, even insidious, what we could also describe as both unmarked and unremarked.Footnote 81 As he writes: “when appropriation does succeed, it works silently, breaching the body’s defenses like a foreign organism and insinuating itself within, as if it were natural and wholly benign.”Footnote 82 At issue here, then, is what we could call the naturalizing force of appropriation, its ability to transform the appropriated object’s earlier meanings and associations while at the same time crafting its new context and appearance as normal and appropriate. It is the scholar’s job, in Nelson’s charge, to break appropriation’s naturalizing spell.Footnote 83 For me this has meant asking how architectural rebuilding shifts a structure’s prior associations and meanings in ways that come off as appropriate, even unremarkable.

Material Culture

Indeed, this very notion of the “unremarked” has come under wider scholarly scrutiny. It has been one of the central insights of so-called Thing Theory that most of the time we pay little attention to the everyday stuff around us, and that therein lies its power.Footnote 84 In our quotidian experience, things just are. We wear, use, or otherwise interact with them while going about our business of living. But in forming the armatures of our existence, material things – from clothing, tools, and furnishings, to streets and buildings – fundamentally condition and structure our ways of being in the world. What “things” we use, and how we use them, not only distinguishes us from one another individually and collectively (in terms of gender, age, class, culture, time in history, etc.), but also forms a means through which we “read” others, interact with the divine, generate knowledge about our world, and pass it on in our present and across generations. Recognizing the fundamental roles that things writ large play in forming, not just reflecting or representing, subjects has shifted the center of gravity of much critical consideration of objects and built environments today (e.g., our clothes, phones, cars, houses, and cities), and I share this work’s sense of urgency for adjusting our lens away from writing narratives that focus exclusively on human agency. I see this as a complement to architectural histories that focus on the formal developments of buildings, their overt political messages, and/or their social and religious functions. A material-culture-studies approach does not negate these insights, but privileges architecture’s dialectic, subject-forming role. In other words, the built environment is indeed shaped by patrons, architects, laborers, and users, but in turn it also shapes all those figures. It is both made by (us) and makes (us), and the present project probes that line, that conversation, or dialectic between Roman and late Roman physical buildings and the embodied experiences of those who created and interacted with them.

Entanglement and Repair

Not only is human existence intimately bound up with material things, but they require our ongoing investment to keep them functional as things (that is, as objects instead of raw material or detritus; as buildings instead of ruins). Things, in other words, are demanding, and lock users into obligations of care at individual and societal levels, a relationship that has been framed as “entanglement” in recent literature.Footnote 85 In complex societies, the degree of entanglement is concomitantly complex: Consider for a moment not just the labor, materials, and expense of maintaining and repairing valuable possessions such as a car or a house today, but also the societal structures and institutions needed to support those investments, from material supply chains and skilled labor markets, to insurance industries, state-organized fire control, and road infrastructure.Footnote 86 At the same time, things’ regular need of maintenance and repair presents moments of renewed investment and engagement with them as opportunities and choices. As Steven Jackson writes, “it is … precisely in moments of breakdown that we learn to see and engage our technologies in new and sometimes surprising ways.”Footnote 87 Another way of putting it, from the perspective of historians looking back at extant ancient things, would be that we can see in every act of repair, restoration, or rebuilding (as well as of excavation, conservation, collection, and display) an engagement with, reactivation of, and commentary on the “old” thing.

Affordance and Path Dependency

There is also a degree to which the things themselves condition the choices made by those carrying out repairs or interventions. Any act of architectural rebuilding, repair, or modification is, in other words, a response to the pre-existing structure, not only its historical associations but also its physical form and materials. Initially coined by James Gibson in his work on embodied perception and response and further explored and developed in a variety of fields, the concept of the affordance of environments and of physical objects refers to what they offer (or “afford”) and how they condition interactions with them. Gibson described organisms’ interactions with the material world as responses to perceived properties and the invitations and constraints that those physical properties engender.Footnote 88 A classic example is the handle.Footnote 89 Whether on a vessel, tool, or door, handles invite users to a particular physical engagement with the object and discourage others. They “tell” you where and how to grasp and manipulate it. They do not necessarily force or prohibit other types of physical interaction (you can lift a pitcher from the neck, hold an axe upside down, or set a pot on its side rather than its base), but their physical properties encourage otherwise. They offer feedback (e.g., through their size, orientation, weight, texture, degree of resistance), and they present constraints and consequences for different types of interaction, which often cost the user more in bodily terms (energy, discomfort), psychological terms (sense of frustration, loss), and/or material resources (spilled contents, broken vessels, replacement expenses).Footnote 90 In this sense, old buildings present a range of affordances – that is, physical invitations and constraints – that encourage certain forms of response and present variable “costs” for others. Structural elements (a building’s foundation and supports – i.e., its “bones”) and its surrounding built and natural topography “cost” the most in every sense to alter, and this fact leads to a form of “path dependency” whereby the sites of older buildings as well as their orientations to other features (e.g., adjacent structures, flanking roads, elevation changes, or the sun) more frequently remain stable even as their surface appearances and sometimes even function might be more readily transformed.

Recycling and Sustainability

“If it can’t be reduced, reused, repaired, rebuilt, refurbished, refinished, resold, recycled, or composed, then it should be restricted, redesigned, or removed from production.”Footnote 91 In our twenty-first century, these words, associated with folk singer icon Pete Seeger, have been emblazoned across public spaces around the world to promote a variety of progressive, nonprofit organizations, including Greenpeace, BrightVibes, and 1 Million Women.Footnote 92 The popularity of the quote is indicative of our age’s pressing concerns surrounding waste and sustainable resource management. Of course, the world of the Romans was not one cognizant of global warming or one in which recycling, as we use it, was a staunchly defended moral position, marketing tool, and political rallying cry. And yet they did reuse and adapt everyday things and materials as well as monuments, sites, and buildings. Plus, there is plentiful ancient testimony that demonstrates Roman concern with both material things’ histories and their potential durations. Similarly, many of our modern senses of temporality are shaped by modern technologies of time measurement, travel, and communication (e.g., mechanical clocks to ice cores, locomotive engines to jet planes, telegraphs to web-based news media) as well as the new, expanded units through which history is written and our place in it is understood (think “Deep History,” the “Anthropocene,” and the “Doomsday Clock”).Footnote 93 None of these figures in the worlds of pre-modern historical actors, but they too had senses of time that were informed and conditioned by technologies of timekeeping, travel and communication, and knowledge about and access to other cultures and worlds, as well as scales and practices of history writing.

So, while this is not a book that looks backward in an effort to recover early chapters of modern sustainability culture or heritage practices (it is not intended as an etiological exercise), I am cognizant of the political and cultural charge in our world, at our moment, and of the range of issues surrounding appropriated, rebuilt, or repurposed structures for us today. My primary aim is to examine the attitudes and effects of long building histories for individuals living in the Roman and late Roman empires, but I do so recognizing that this project is very much born of our present moment and has benefited from current critical and popular attention to questions surrounding the temporality of material things as well as socially responsible production and consumption and as such is part of a growing body of literature examining such issues in the ancient world. Scholars’ questions, mine included, are born out of and shaped by the world in which they are written. Acknowledging the conditions of our position allows us to be clear about our aspiration to take our historical evidence on its own terms while also appreciating its relevance and currency for our own day. It also lends us perspectives on the ancient world distinct from those of earlier generations of scholars, whose own contemporary concerns differ from ours, and this can in turn propel our scrutiny of different data and lead to new observations and insights about even well-known material.

Roadmap and Readers

My investigation spans the Mediterranean and encompasses the roughly six centuries between Augustus and Justinian in an effort both to better understand broad chronological patterns and to identify productive points of comparison across diverse regions and types of sites. The book is driven by questions that are themselves inherently diachronic: How and why did rebuilt buildings announce themselves as such (as opposed to new construction)? How did they affect urban rhythms and temporal patterns? How did imperial and private patrons capitalize on and manipulate the legacy of previous benefactors in rebuilding pre-existing structures? How did alterations to the built environments of Roman cities emplace and spatialize local and imperial histories? How did period rhetoric about temporality, renewal, and material durability relate to rebuilding practices, their commemorative “packaging,” and the responses they aimed to elicit? What were the cumulative effects of multiple epigraphic, decorative, and spatial transformations over a building’s long ancient history? Focusing on a wide range of public architecture (I leave private architecture of houses and tombs to another project since it intersects differently with euergetistic patronage systems and engages different audiences), I aim to explain the social and cultural “work” that rebuilding performed in imperial centers and provincial peripheries across these centuries of profound political and religious transformation.

To do so, I have organized the work into three interrelated sections. The first set of chapters operates at the level of patrons and their communities – imperial and local – to grapple with architectural rebuilding as a mechanism through which shared pasts, presents, and futures were articulated and substantiated. Chapter 1 examines architectural rebuilding as an ideological virtue. In particular, I look to histories, coins, and inscribed statue bases to chart the place and shape of architectural rebuilding (in comparison with and juxtaposition to new construction projects) within the broader commemorative landscape of honor and virtue in cities across the Mediterranean. The next chapter, a pendant to the first, argues for the importance of temple anniversaries and other festivals associated with rebuilding for writing, experiencing, and synthesizing chronologies in time and space at the lived, local level. Chapter 3 focuses on the mechanisms through which certain special temple buildings were invested with an essential future-oriented “prospective” role for empire and how in the face of crisis – especially the physical destruction of the buildings along with the challenge to the claims for continuity and security that came with them – those mechanisms were renewed or transformed.

The rest of the book turns to examine specific material mechanisms through which rebuilt buildings conditioned and reified Roman and late Roman temporalities. The suite of chapters comprising Part II homes in on monumental building inscriptions as central means through which individual buildings shaped perceptions of their own architectural histories and of temporal change more broadly. The first of these investigates assemblages of epigraphic records of architectural interventions that accumulated on buildings over their long ancient lives. My analysis of these encrusted epigraphic environments charts a range of strategies that benefactors adopted in setting up their own commemorative texts vis-à-vis those of earlier patrons and the effects of those decisions on the inscriptions’ reception by contemporary audiences. Chapter 5 layers in investigation of notions of empire and longevity, examined here through the lens of more mundane and pervasive structures – its streets and public highways – to reckon with the attenuated and amalgamated temporalities that these infrastructures construct through the accumulation of large- and small-scale acts of maintenance and repair and the referencing of those interventions by milestone monuments. Chapter 6 digs deeper into the textual conventions deployed in many of the monumental inscriptions set up on restored structures. In particular, I point to how they responded to and influenced the experience of the inexorable degradation of time through a rhetoric of ruin and fragmentation that both naturalized and justified the form or extent of rebuilding and that shifted in late antiquity to increasingly vivid, sensorially affective forms.

Moving from revised buildings’ monumental texts to their material surfaces and spatial arrangements, the book’s final section expands our investigation into “unmarked” ways in which new contexts reframed old elements. Chapter 7 argues that change over time was regularly characterized and symbolized in terms of vividly contrasting architectural substances, in which marble (especially) was used to chart (and critique) urban progress and to modulate a balance between tradition and innovation. The book’s final chapter turns to questions of spolia and converted buildings. My discussion reorients conventional approaches to these debated topics by exploring architectural reuse through the lens of lived experience. Focusing on evidence for original doorways blocked in later phases of a building’s occupation at a series of repurposed sites, I make a case for studying conspicuous traces of a building’s former use as a window into social and somatic modes of temporality not captured by official commemorative inscriptions or building histories.

Throughout the project, I have aimed for the work to be accessible and of use to multiple audiences. Though scholars in Roman and late antique/early Byzantine studies (art and architectural historians as well as cultural historians more broadly) will be most familiar with the specific sites and their historical framework, my hope is that the book will also be valuable to individuals interested in questions of restoration, temporality, and the built environment in other times and places as well. To that end, I have endeavored to gloss and unpack specialized material, I have referenced historical dates using modern month names and year conventions (BCE/CE), and, when quoting primary sources, I have referred to easily available editions and translations whenever possible.Footnote 94

~ ~ ~

Like other forms of visual and material culture, buildings are cultural products, and they arise from the collaborative efforts and vision of patrons, designers, and craftspeople. But also like other forms of visual and material culture, buildings are cultural forces that in turn condition the movements, perspectives, responses, and worldviews of those who create, use, and encounter them. By juxtaposing Roman discussions about and practices of rebuilding, the book exposes broader dynamic processes at work between the human production of material culture and architecture’s formation of individual and shared subjectivities and perspectives about time. Both textual evocations and physical evidence of old structures – dilapidated and patinaed or rebuilt and conspicuously re-“newed” – affect how our present relates to the past (or specific pasts), and how we understand the span of our lives and that of the age in which we live in terms of built environments that extend beyond it in both directions, preceding and outlasting us. One book cannot adequately cover all these issues, but I hope to advance our conversation in ways that prove thought-provoking and that stimulate new reflections on old architecture, then and now.