Introduction

It is almost inevitable that experiences in one life domain, such as leisure, have implications for one’s experiences and achievements in other life domains, such as work or athletics. To conceptualize and model such cross-domain influences, scholars have introduced the concept of “spillover” (Greenhaus & Beutell, Reference Greenhaus and Beutell1985; Staines, Reference Staines1980). Spillover refers to the transfer of emotions, cognitions, or behaviors from one domain of life to another (Rodriguez-Muñoz et al., Reference Rodriguez-Muñoz, Sanz-Vergel, Demerouti and Bakker2014). In their Work–Home Resources (W-HR) model, Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker (Reference Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker2012) depict spillover as an indirect process that comprises antecedents in one life domain, mechanisms that connect experiences across domains, and outcomes in another life domain, originally focused on the interface between the work and the home domain. Spillover is a bidirectional process in which domains can mutually affect each other. In the current study, we apply the basic premises of the W-HR model (Du et al., Reference Du, Derks and Bakker2018; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Reference Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker2012) to the world of elite sports. To this end, we use a qualitative lens to examine spillover from off-sports life domains to the sports domain among elite athletes, illuminating what it is that athletes do outside of their sports and how these activities spill over to affect their sports experience.

Off-sports-to-sports spillover is triggered by athletes’ actions and experiences outside of sports, that is, by what they do and feel at moments, days, or longer periods that are free of formal sports activities. The current literature, however, offers little insight into spillover processes from the perspective of elite athletes. Most spillover studies have been conducted in the work-home context, examining how experiences at home relate to work behavior and performance, or vice versa (e.g., Steed et al., Reference Steed, Swider, Keem and Liu2021). Relatedly, and also predominantly staged in the work-home setting, recovery research has identified how activities and experiences at home can promote as well as undermine recovery from work by affecting a wide range of indicators of employee well-being (e.g., Sonnentag et al., Reference Sonnentag, Venz and Casper2017, Reference Sonnentag, Cheng and Parker2022). Such recovery activities and experiences represent the step from antecedents to mechanisms in the WH-R model, illustrating how on-the-job activities can help or hinder replenishment of personal resources that became depleted by work demands.

More specific to the sports domain, research has addressed the link between off-sports time and sports outcomes, but focused primarily on the physical component (i.e., physical recovery after exertion; Eccles et al., Reference Eccles, Balk, Gretton and Harris2022), for example, on the role of sleep in relation to sports performance (e.g., Halson, Reference Halson2014). Another relevant line of sports research considers the combination of life domains from a dual-career perspective (e.g., Hallmann & Weustenfeld, Reference Hallmann and Weustenfeld2025; Torregrosa et al., Reference Torregrosa, Ramis, Pallarés, Azócar and Selva2015). This research offers impactful insights into challenges and benefits involved in combining an athletic career with study or work and how to best support dual-career athletes, but generally does not zoom in on more fine-grained psychological spillover mechanisms across domains.

In all, while the above-outlined research provides relevant background, specific research on athletes’ activities and experiences while off sports and their connection to experiences and outcomes in the sports domain is largely lacking. An exception is a quantitative study among student athletes (Postema et al., Reference Postema, Van Mierlo, Bakker and Barendse2022), focused on study crafting as an antecedent of study-to-sports spillover, defining study crafting as “behaviour that refers to shaping the study environment to create a better fit between a student’s skills, needs, and abilities and the study environment, and create a feeling of purposefulness” (p. 71). Their findings provide initial support for the occurrence of spillover from study to sports among high-level athletes. However, as illustrated in Eccles and Kazmier’s (Reference Eccles and Kazmier2019) work on psychological rest among high-level student athletes, off-sports experiences are not limited to studying but involve a wide range of potential activities and experiences. More research is needed to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the types and array of activities that elite athletes pursue in other life domains, and how these activities may spill over to affect their athletic experience. The current study, therefore, aims to gain nuanced insight into athletes’ own accounts of both their off-sports activities and their views on how these activities affect their athletic life. In addition to extending current conceptual knowledge of the spillover phenomenon, from a more applied perspective, such insights can contribute to the (re)design of strategies and interventions that athletes, coaches, clubs, and professional associations or other athlete support structures could use to optimize athletes’ well-being, fitness, and performance.

Theoretical Background

Spillover processes can be positive or negative. A positive, energizing indirect process from one life domain to another is called enrichment (Greenhaus & Powell, Reference Greenhaus and Powell2006). Based on the W-HR model (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Reference Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker2012), enrichment may occur when contextual resources (e.g., social support, growth opportunities) enhance personal resources (e.g., energy, confidence) that can be used in the sports domain. For example, an athlete engaging in study-related activities during off-sports time (antecedent) may experience a sense of accomplishment (mechanism), enhancing confidence and energy in sports training (outcome). A negative, depleting indirect process is called interference (Greenhaus & Beutell, Reference Greenhaus and Beutell1985) and can arise when contextual demands (e.g., overload, scheduling challenges) undermine one’s personal resources (diminished energy, mental distraction), causing unfavorable sports outcomes. For example, when the study activities are highly demanding and cause mental fatigue (mechanism), resulting in tiredness and underperformance in training (outcome).

Off-sports activities can vary in effort and function. Broadly, they can be more passive, restful, and low-effort or more (pro)active and effortful, each with distinct implications for athletic functioning (Eccles & Kazmier, Reference Eccles and Kazmier2019). This distinction emerges from stress recovery theories and research on recovery from work (Meijman & Mulder, Reference Meijman, Mulder, Drenth and Thierry1998; Sonnentag et al., Reference Sonnentag, Venz and Casper2017, Reference Sonnentag, Cheng and Parker2022). In sports, passive recovery includes low-intensity activities—such as resting, watching TV, or napping—promoting physical and mental restoration after demanding training or competition. These activities provide physical as well as mental rest as they place minimal strain on the individual and support replenishment of depleted energy reserves (Kellmann et al., Reference Kellmann, Bertollo, Bosquet, Brink, Coutts, Duffield, Erlacher, Halson, Hecksteden, Heidari, Kallus, Meeusen, Mujika, Robazza, Skorski, Venter and Beckmann2018). Resource-based theories highlight that recovery may also occur through deliberate, more active engagement in off-sports activities that stimulate personal growth and build new resources, such as learning something new, volunteering, or pursuing a creative hobby. These activities may not reduce fatigue directly but instead enhance meaning, self-efficacy, or autonomy, expanding the athlete’s resource reservoir beyond the baseline (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Bakker and Field2018; Petrou et al., Reference Petrou, Bakker and Van den Heuvel2017; Ten Brummelhuis & Trougakos, Reference Ten Brummelhuis and Trougakos2014). Conceptually, both passive and active off-sports activities may lead to enrichment or interference. To the extent athletes engage in activities that further deplete available resources, they may thwart recovery and trigger interference and adverse sports outcomes. To the extent athletes pursue off-sports activities that result in resource recovery or gain, they may experience enrichment and beneficial sports outcomes.

In the realm of recovery research, specific recovery activities can trigger different recovery experiences, that is, the experience of feeling recovered through relaxation, detachment, mastery, or control (Sonnentag et al., Reference Sonnentag, Cheng and Parker2022; Sonnentag & Fritz, Reference Sonnentag and Fritz2007). Recovery experiences reflect valuable personal resources that can function as spillover mechanisms that connect activities and experiences across domains. Relaxation reflects the experience of rest and low physical activation. Detachment is the experience of leaving work—or sport—behind. Mastery represents a sense of success or achievement resulting from engagement in challenging situations, while control relates to the experience of autonomy in shaping one’s nonwork time. By influencing these recovery experiences, off-sports activities can promote or hinder perceived well-being, which may carry over into the sports domain (Sonnentag et al., Reference Sonnentag, Cheng and Parker2022).

Aside from some exceptions focusing on detachment (e.g., Balk et al., Reference Balk, de Jonge, Oerlemans and Geurts2017) and psychological rest (e.g., Eccles et al., Reference Eccles, Balk, Gretton and Harris2022), mirroring spillover research, recovery research has mainly addressed recovery from work demands through experiences in the home domain. Although elite sports have commonalities with work (e.g., Van Breukelen et al., Reference Van Breukelen, Van Der Leeden, Wesselius and Hoes2012), elite athletes face unique demands and challenges, including intense physical exertion with a well-established need for physical rest. In this distinctive environment, athletes’ off-sports activities and experiences, recovery needs and effectiveness, and spillover experiences may differ considerably from those in a generic work population, challenging the applicability of prior insights from existing spillover and recovery research. Given the paucity of research in this group, it remains unclear how elite athletes spend their time outside of sports and how their off-sports activities affect their sports experiences and performance.

The present study adopts a qualitative approach to explore off-sports-to-sports spillover, aiming to inform future theorizing on spillover processes among elite athletes. The qualitative design allows an in-depth exploration of the activities elite athletes engage in, the outcomes they experience in the sports domain, and the mechanisms that connect domains. We address two research questions. First, what is it that elite athletes do in their off-sports time, and what themes or categories emerge in the activities they report (Research Question 1)? Second, how and when do off-sports activities enrich or deplete elite athletes’ sports experience, and what antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes of spillover do they experience (Research Question 2)? In addressing the first research question, we adopt a realist epistemology, assuming that athletes’ activity reports reflect actual behaviors that can be organized into meaningful categories, while recognizing that our analysis is shaped by our interpretive frame (cf. Maxwell, Reference Maxwell2012). For the second research question, we shift to a critical realist perspective (cf. Maxwell, Reference Maxwell2012) using a hybrid approach combining inductive and deductive strategies (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Reference Fereday and Muir-Cochrane2006) to provide an in-depth descriptive analysis of athletes’ own experiences of off-sports-to-sports spillover.

Method

Procedure and Participants

The sample included two distinct groups. Sample 1 is a group of professional soccer players, based on which we answered the first research question regarding the type of activities elite athletes engage in off sports. Sample 2 is a sample of elite speed skaters whose input we used to answer both research questions. While our sampling was partly driven by access and thus reflects convenience sampling, combining these two samples in answering our first research question served a clear purpose. In the absence of prior empirical information about elite athletes’ off-sports activities, we sought to maximize the potential breadth of reported off-sports activities. Validating the initial findings from the soccer players based on a different group of athletes helped us achieve this and allowed us to explore consistencies and differences in these athletes’ off-sports activities. While both samples reflect high-level elite sports with steep physical and mental demands within a professional sports environment, the samples also differ in many ways, an issue we will return to in our discussion.

Sample 1 consisted of male soccer players from the first and second teams of a professional soccer club in the Netherlands that competed at the highest national level at the time of the study. All players aged 18 or older were invited to participate in the study. Upon approval from the relevant research ethics committee and as part of a larger research project, the players completed a paper-based survey after giving informed consent. The survey included an open-ended question asking participants to list their off-sports activities: “Besides soccer, what activities do you generally engage in?” In total, 46 male soccer players answered this question and were included in the current study. Their average age was 21.74 years (SD = 3.58). They trained 4–6 days a week for 1.5–2.5 hours each time. Of these players, 49% had completed secondary education, 36.2% had completed vocational education, and 4.1% had a bachelor’s degree. At the time of the study, 12 players (26%) were enrolled in formal education.

Sample 2 included 15 professional speed skaters (9 women, 6 men, all Dutch) who competed in speed skating on at least a national level. Fourteen of them (had) competed internationally, for example, in World Cups, European Championships, and/or World Championships in past seasons and/or the present season. The skaters were between 19 and 31 years old (M = 21.80, SD = 2.70), an age profile similar to that of the soccer players. At the start of the interview, participants gave informed consent after having been informed about the study goals, assured they could withdraw from the study at any time, and explained that all data would be treated confidentially. All participants agreed to the interview being audio-recorded. The interviews were transcribed verbatim, and these transcripts were the basis for our analysis.

The speed skaters were interviewed to obtain descriptive information about their off-sports activities and experiences, and their possible connection to their athletic experience. Interviews are a valuable tool in gaining in-depth information about the experiences of and meaning attributed by individuals (Smith & Sparkes, Reference Smith, Sparkes, Smith and Sparkes2016). The interviews were semi-structured, and interview questions focused on obtaining descriptions of the spillover process. Specifically, we aimed to explore and distinguish the antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes of spillover, while also examining how the athletes experienced connections between these elements. Where appropriate, we included open-ended and follow-up questions for nuance and clarification. These interview data served two purposes. First, to validate the category framework of off-sports activities that we developed from the soccer player sample, based on a different group of athletes. Second, to explore how elite athletes experience spillover between the off-sports and sports domains.

Strategy of Analysis

To identify the activities that athletes engage in off sports (Research Question 1), we conducted a stepwise thematic content analysis (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006; Weber, Reference Weber1990) to develop and validate a category framework of off-sports activities. In Step 1, two raters (the first and second authors of this paper) independently made a first categorization of the activities reported by the soccer players. This initial step entailed collapsing (near) identical codes and gradually sorting and combining similar activity descriptions. In Step 2, both raters, still independently, repeated the first step to condense the first categorization into axial codes, reflecting fewer and more central categories, and added category descriptions. In Step 3, the raters met to compare and discuss their categories and descriptions and determine the final categorization. To verify the categorization, they reassigned all original activities to the final categories, refining the category descriptions where appropriate. In Step 4, a third rater (the third author of this paper) independently assigned all activities that were mentioned by the soccer players and speed skaters to a category in the final framework. This rater is an expert on cross-domain spillover but had not been involved in Steps 1 to 3 and was at that point unaware of both the categories and the reported off-sports activities. In this final step, the off-sports activities obtained from the speed skater sample were added to the list of activities. The first author extracted these activities from the interview transcripts by applying a structural code to identify any specific off-sports activities the skaters mentioned. These activities had not been used to develop the category framework and could therefore be used to assess saturation, that is, evaluate whether the framework was appropriately exhaustive, or whether additional categories should be added. This additional validity check is commonly recommended for qualitative studies focused on developing category frameworks (see, e.g., Moore et al., Reference Moore, Van Mierlo and Bakker2022).

To investigate elite athletes’ own experiences of off-sports to sports spillover (Research Question 2), we analyzed the interviews with the speed skaters. We adopted a hybrid inductive-deductive analysis approach (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Reference Fereday and Muir-Cochrane2006), following a 6-step thematic analysis plan (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Clarke, Weate, Smith and Sparkes2016; Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). The steps involved (1) becoming familiar with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) writing the report. The initial coding was conducted by the first author. In Step 1, they first scanned and then read and reread all interview transcripts, making short summaries of each transcript to form an overall impression and taking notes to register potentially relevant codes and meanings. In Step 2, initial codes were generated. Our initial coding strategy was guided by grounded theory coding principles, including iterative open coding, constant comparison, and attunement to emerging patterns and theoretical relevance (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz, Morse, Bowers, Charmaz, Clarke, Corbin and Stern2016; Cresswell, Reference Cresswell2013). The first author systematically identified and selected relevant text fragments, iteratively revisiting and reviewing the transcripts to refine the coding and ensure completeness. In Steps 3 to 5, we shifted to a deductive theory-driven approach that involved grouping the initial codes into the two main spillover patterns identified in the literature: enrichment (i.e., positive spillover; Greenhaus & Powell, Reference Greenhaus and Powell2006) and interference (i.e., negative spillover; Greenhaus & Beutell, Reference Greenhaus and Beutell1985). The enrichment and interference quotes were then split into antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes, and the grouping of codes and assigned themes was reviewed and discussed among the authors to fine-tune the assignment to and naming of themes. Finally, in Step 6, the most frequently mentioned and relevant antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes were identified and used to describe the mechanisms of off-sports-to-sports spillover as experienced by the elite speed skaters in our sample.

Results

Elite Athletes’ Activities in Off-Sports Time

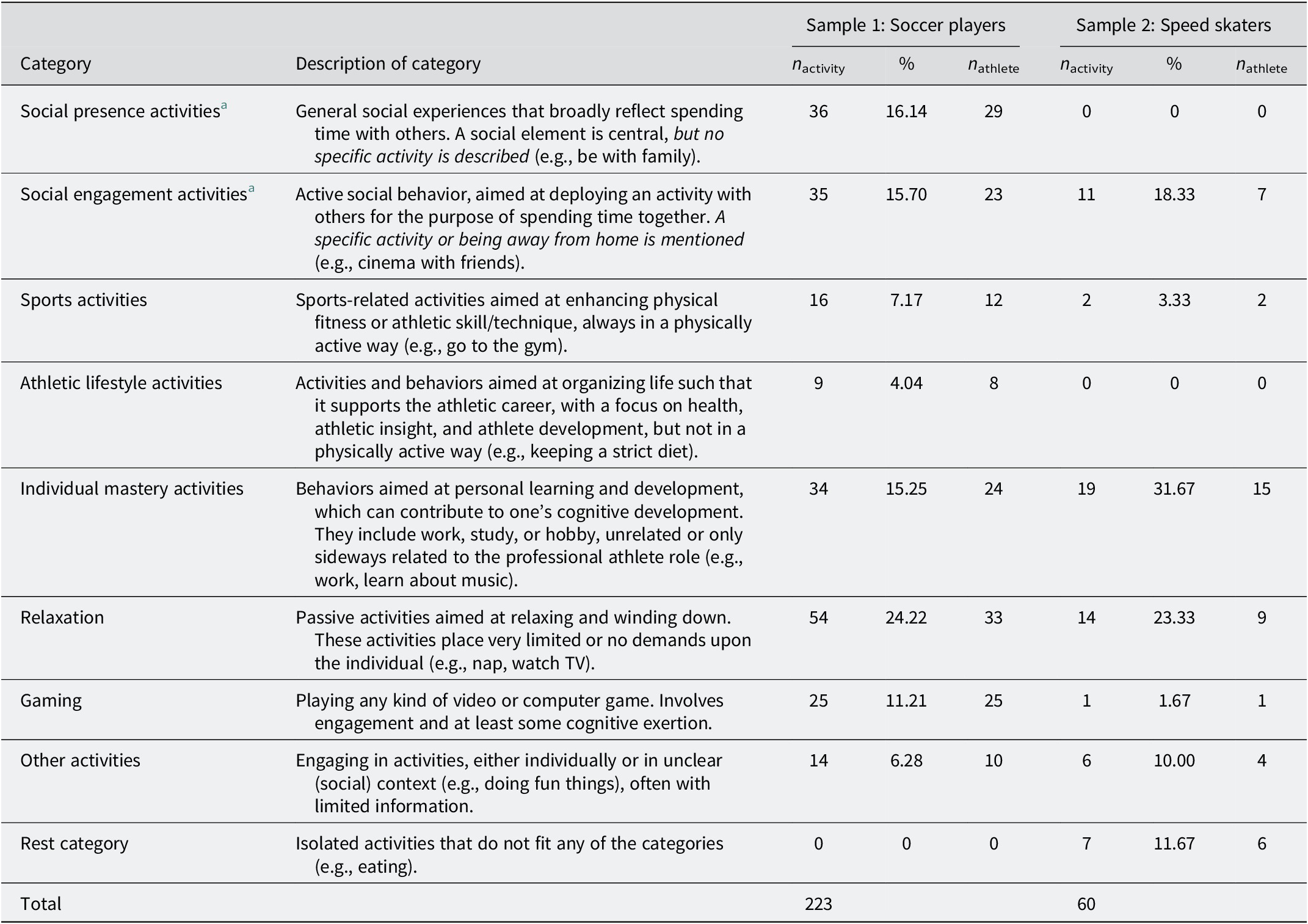

First, to examine what elite athletes do in their off-sports time (Research Question 1), we analyzed and categorized all 235 off-sports activities reported by the soccer players. After collapsing identical listings, 225 unique activities remained, ranging from what we labeled as low-effort or more passive behaviors and activities (e.g., relaxing, watching TV) to higher-effort or more active behaviors and activities (e.g., cooking workshop, studying for an exam). Table 1 displays the final categories with descriptions and frequencies. The development phase (Steps 1–3) resulted in nine categories. In Step 4, the third rater reassigned all soccer player activities to the specified categories, plus the 60 activities extracted from the speed skater interviews. This step led to minor changes in our category descriptions to resolve unclarities and avoid potential misinterpretation. Most importantly, the two social categories raised questions, as apparent from different assignment choices compared to the original intentions, which led us to revise the category descriptions to clarify the distinction (Table 1).

Table 1. Overview of categories and the occurrence of activities within each category for soccer players and speed skaters

Note: We excluded 2 reported “activities” from the soccer sample, as they did not reflect an activity.

a Categories that were clarified based on the independent rater’s reassignment of activities to categories—clarification in italics.

Two categories relate to social experiences. We labeled them social presence and social engagement activities. Social presence broadly refers to spending time with family or friends, without identifying a specific activity or purpose (e.g., “spending time with my family”), while social engagement relates to deliberate active social behavior aimed at deploying activities with others (e.g., “doing fun activities with my little brother or with friends,” or “playing board games”). Such social experiences were highly prevalent, reflecting 32% of all activities in the soccer sample and 18% in the speed skater sample.

The next two categories are closely tied to being a professional athlete. Both sports activities and athletic lifestyle activities involve organizing life outside the formal athletic context in a way that supports the athletic career. Sports activities refer to sport and exercise to boost physical fitness (e.g., “going to the gym”), while athletic lifestyle activities focus on accommodating and advancing one’s athletic skills and career (e.g., “watching soccer on TV to improve my weaknesses,” or “keeping a strict diet”). These two categories comprised 11% of all reported activities, with one or more reports from 18 soccer players (39%). This indicates that, for these players, being an athlete defines part of their off-sports life and identity and permeates other life domains. Notably, speed skaters mentioned only a few of such activities, with just two instances of sports activities.

Next, “individual mastery activities” reflect actions and experiences conducive to personal learning and development in a domain unrelated or only sideways related to the elite athletic context, for example, “following a Spanish course,” “studying media & journalism,” or “reading booksFootnote 1.” The activities in this category can be qualified as relatively high in effort and cognitive activation and often have a goal-directed component. Mastery activities were highly prevalent: More than half of the soccer players and all speed skaters described one or more activities in this category.

The relaxation category refers to activities athletes engage in to rest and wind down, for example, “sleeping,” “checking social media while lying on the couch,” or “watching TV and Netflix to relax.” Typically, these activities are undemanding, with little activation of the physical and mental system (Stone et al., Reference Stone, Kennedy-Moore and Neale1995), allowing restoration of physical resources. It is again a prevalent category, including 54 descriptions, with 72% of the soccer players and 60% of the speed skaters mentioning one or more relaxation activities.

“Gaming” emerged as a separate category. Activities in this category were simply described as “gaming” or “PlayStation,” mostly without explanation and without mentioning the presence of others. Gaming can mean many things and, depending on the type of game (e.g., prosocial, violent, puzzle), can be challenging and enhance cognitive or emotional skills, social and interactive, sports-related (e.g., when playing soccer games), or relaxing. Our current data included no further information on the nature of the gaming activities. Moreover, the speed skaters in our sample reported only one gaming activity, so we were unable to gain more in-depth insight into the nature of gaming among these athletes. We therefore consider this a preliminary category that requires follow-up.

A last category (“other activities”) was created for activities that could not be assigned to any of the substantive categories, and most were reported only once. Often, these reports lacked specificity and might have fit another category if more background had been available. “Having coffee,” for example, might reflect social engagement if it was with friends in a café, or relaxation if it was a quiet coffee moment alone at home. A small subset comprised household tasks, specifically “cooking,” “good cooking,” “household,” “grocery shopping,” and “walking the dog.” In all, the “other” activities were difficult to interpret, illustrating a limitation of the written activity reports from the soccer players that we return to in the discussion.

In the final step, we validated the category framework using the off-sports activities reported by the speed skaters. All the activities they reported could be assigned to one of the above categories. Moreover, the speed skaters reported activities in most categories—except social presence and athletic lifestyle activities—suggesting that the category framework is appropriately complete and saturated as well as representative of the things professional athletes do in their off-sports time. Despite major differences between these two athletic contexts, the observed alignment between activities reported by the speed skaters with the activities derived from the soccer players tentatively indicates substantial commonalities in the types of activities elite athletes pursue while outside of sports.

The samples also differed in several ways that are worth noting. First, 11 of the 15 speed skaters (73.3%) were students and went to school or university, which was much less common among the soccer players (n = 12, 26.1%). This explains at least in part the higher frequency of mastery activities among the speed skaters (soccer players 15%, skaters 31%), for whom such activities were often study-related. Second, compared to the soccer players, the speed skaters had more time-intensive training schedules. Soccer players mostly trained once a day for 1.5–2.5 hours, whereas most skaters routinely did two daily training sessions of several hours; if they trained endurance, one training could take up to 4 hours. This limited their opportunities to engage in off-sports activities, even more so for those who combined sports and study. This seems a plausible explanation for the lower frequency of sports activities, gaming, and, to some extent, social activities in the speed skater sample. Notably, relaxation and rest were equally prevalent in both groups, comprising 23% of the activities for the speed skaters and 24% for the soccer players.

In all, the category framework includes a mix of (a) more passive low-effort activities (e.g., relaxation) and (b) more active higher-effort activities (e.g., athletic lifestyle activities). It includes social (e.g., social presence), physical (e.g., sports activities), and cognitive (e.g., individual mastery) activities, presenting a first systematic overview of the things elite athletes do during off-sports time.

The Spillover Process as Experienced by Athletes

Next, we analyzed the semi-structured interviews with the speed skaters to address how and when they experience that off-sports activities enrich or deplete their experiences in the athletics domain. After initial open coding, we identified antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes of the spillover process that athletes described based on the W-HR model (Du et al., Reference Du, Derks and Bakker2018; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Reference Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker2012). We classified code groups as antecedents when relating to activities in an off-sports domain, as mechanisms when reflecting personal resources or recovery experiences acquired or depleted through off-sports experiences, and as outcomes when comprising sports-related experiences and outcomes described in connection to off-sports experiences. We distinguished between enriching and interfering relationships from off sports to sports and considered contextual influences. To ensure relevance, we focused mainly on factors that were mentioned by multiple athletes, or, if only mentioned once, were central to the experience of spillover.

Off-Sports to Sports Enrichment

Asked about specific moments at which off-sports activities positively influenced sports outcomes, the skaters mostly talked about school or study. This is consistent with the nature of this sample: The speed skaters had rigid training schedules and many also went to school or university or had a job, leaving limited time for off-sports activities in the family or leisure domain. Skaters also mentioned issues related to work or leisure.

Antecedents of Off-Sports-to-Sports Enrichment

When athletes mentioned that an activity outside of the sports domain contributed positively to personal resources or sports outcomes, we coded it as an antecedent of off-sports-to-sports enrichment (see Table 1). Their explanations in the interviews illustrate how the speed skaters experienced the antecedents and their impact. Skaters described key antecedents related to social engagement, individual mastery, and relaxation activities. The most commonly mentioned enriching activities were related to proactive behaviors aimed at optimizing their study situation, helping them receive the right amount of support, or making school or work more engaging. All skaters offered such examples, which align with the concept of study crafting (Postema et al., Reference Postema, Van Mierlo, Bakker and Barendse2022): Making purposeful adjustments to improve the fit between study and athletics. As one skater noted:

You make a plan with your academic advisor but have to take the initiative to arrange changes with the course coordinators. If you do that, then most things are possible.

And another athlete referred to deliberately organizing fun at school:

You can make school fun yourself. That does not always mean I have a good day [performing] at school. But if I feel good and enjoy school, I’ll be happier during training.

In addition to proactively organizing their mastery activities, some athletes also identified the content of these activities as relevant to potential enrichment. One participant, for example, studied nutrition and found that their coursework for certain topics helped them gain insights that made them a better athlete.

Social engagement activities were another recurring theme. Athletes emphasized the value of maintaining friendships outside of sports: “It is good to hang out with friends and keep up your social life.” And others described how hanging out with non-sports friends and having non-sports-related conversations affected them positively:

[…] just being around other people. I loved sitting next to my smelly study friends, still recovering from a night out, with different stories to tell.

Finally, the athletes also mentioned rest and relaxation, but less often than the mastery activities. Moreover, the connection to athletic outcomes was less direct. They would mainly mention having a training-free day or being able to “chill” between trainings as important. As one skater put it: “Basically, it’s good to rest and use that energy in my training sessions.”

Interestingly, many speed skaters seemed to associate rest with mental disengagement rather than with restful, more passive activities. They often described how being active in another domain contributed to mental rest and detachment, reflecting the notion of psychological rest (Eccles & Kazmier, Reference Eccles and Kazmier2019) rather than the more physically restful activities we qualified as “relaxation activities.” One interviewee compared studying to just relaxing: “Yeah, I actually feel more rested in my head when I’m studying.”

Enrichment Mechanisms

The mechanisms affected by athletes’ off-sports activities broadly fell into four clusters: Cognitive, intellectual, emotional, and physical resources. The most frequently reported mechanism was cognitive detachment: Mentally stepping away from sports. This helped skaters return to their sports feeling refreshed. As one skater who worked a job alongside their athletic career said: “When I arrive at training, I think, great, I’ve been completely away from skating.” Another described how their mastery activities supported detachment more effectively than more passive relaxation:

If your turns go badly in training, you can come home, sit on the couch, and dwell on it all day. And if you do something else [studying or working], you do not think about it and step onto the ice the next day feeling refreshed.

Enhanced confidence was another cognitive personal resource the athletes gained mainly through off-sports mastery activities. Achievements in another domain and success in balancing two domains boosted their general self-confidence: “If you get a good grade, you feel good and gain confidence. This shows you are also capable of other things than skating.”

The athletes also mentioned several examples of intellectual resources gained when off-sports activities provided knowledge and skills relevant to the sports context. One skater explained how keeping up with his full schedule benefited his self-regulation skills and sense of control. Another saw a specific use for skills developed through their study:

In my studies, I write a lot of papers. Next year, I might skate for a new team and need to write a motivation letter to get selected. That’s easier when you have had lots of writing experience.

Emotional mechanisms referred to positive experiences in off-sports domains that boost athletes’ mood, which they carried into the sports domain, as illustrated in the above quote on organizing fun at school. Finally, physical resources were mentioned more generally, referring to the importance of rest and relaxation for recovery. These speed skaters seemed to consider physical rest a necessary condition for doing elite sports rather than as an enriching influence.

Outcomes of Off-Sports-to-Sports Enrichment

Positive sports outcomes were mostly mentioned in relation to more active, higher-effort off-sports activities, often related to school, study, or work. They included enhanced motivation and energy, feeling more confident as an athlete, reduced worry and stress for competitions, and enhanced sports performance. Illustrating the motivating potential of off-sports activities, a skater enrolled in university described how training would feel as an outlet from both positive and negative study experiences, enhancing their training motivation: “After a good day at university, training goes easily. After a tough day at university, it is great to let things go in training.” And another explained how studying would boost their energy:

Some courses interest me a lot, I really enjoy working on them. This makes me feel less bored between training sessions and start the next training more energized.

Athletes also described the potential of off-sports activities to boost confidence in their athletic abilities. One skater explained how the confidence they gained from study successes carried over to their sports: “When I pass a course, I get a very good feeling. This gives you confidence in your abilities on the ice as well as at school.” In general, some athletes also described seeing their study as a safety net that made them less dependent, insecure, and hence more relaxed in their sports.

Stress reduction was also mentioned as an outcome of enrichment. Some skaters offered examples of how their involvement in high-effort non-sports-related activities helped them disengage from sport and could reduce nerves or stress before tournaments, which benefited their sports performance. For example:

At school, the day before a major tournament, I’m not thinking about skating and cannot worry about it. And I noticed how the skating went better, and how I felt more relaxed on my way to the tournament.

Finally, as also illustrated above, several athletes felt that their off-sports activities contributed more generally to their athletic performance. One of them attributed this to a combination of mastery and social engagement activities, both derived from their study:

I had a good study rhythm. I had a great group of fellow students with whom I hung out, and that entire pre-season period, I skated very well and set personal records.

Off-Sports to Sports Interference

The speed skaters also talked about antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes of negative spillover, detailing how some off-sports activities could undermine sports outcomes.

Antecedents of Off-Sports-to-Sports Interference

Considering how things they did off-sports might undermine their sports, skaters mentioned activities in the relaxation and mastery activity categories. Noticeably, several athletes first thought of the negative effects of “doing nothing,” or over-engagement in passive relaxation like extended rest without cognitive engagement. Comparing seasons of full focus on skating with seasons of parallel activity in study or work, they described feeling mentally and physically under-stimulated during sports-only seasons. As one skater explained:

[When your only focus is skating] you are either training or taking mandatory rest. I had so much time to rest. It increased my energy levels. But it did not make me happy and that cost me energy.

And another shared:

It was quite relaxed living at home and having food made for me, lying on the couch for six hours a day, but I realized my brain needed stimulation. I was super bored at times.

On the other hand, mastery-related activities were also commonly mentioned as triggers of interference, especially during periods of high academic or work pressure. Multiple skaters mentioned that intense studying for exams or completing school deadlines could deplete their energy and disrupt training. For example:

The weeks before the deadline are hectic. I’m so busy with school that I am more tired and sometimes skip training.

Another skater, looking back at combining mandatory school with junior elite skating:

When I was younger and had to go to school every day, this had negative effects; after an exam week I could just forget about doing competitions.

Finally, travel between work or school and sports was also mentioned as a burdensome activity that could contribute to feeling busy and cause scheduling conflicts.

Interference Mechanisms

We identified two clusters of off-sports-to-sports interference mechanisms, aligned with the analysis of antecedents. First, over-engagement in active, effortful off-sports activities, mostly related to study and work, could at times deplete athletes’ personal resources: Tiredness, lack of sleep, stress, and reduced mental fitness, particularly during busy periods when studying for exams or working long hours. Several athletes had experienced feeling tired because their day was so full, or a lack of sleep after staying up late or waking up early to study for exams. One athlete described how a major school project affected their well-being: “You sleep little, you’re typing all the time, and your brain is overloaded – basically you just don’t feel good.”

The second cluster involved over-engagement in passive, low-effort activities, often as a direct consequence of a lack of involvement in the more active, high-effort off-sports activities. Athletes described a lack of external structure or stimulation, causing under-stimulation, boredom, rumination about sports, and lack of detachment. The following quote illustrates this experience, which was shared by many athletes when referring to periods when they did not study or work alongside their sports:

I wasn’t working at the time, so I had my full focus on skating, but I had a lot of free time in between and became bored. That’s when I decided to look for an internship.

In both cases, interference emerged when these athletes were unable to sufficiently recover or mentally reset, either due to excessive demands from or absence of meaningful off-sports activities. Similarly, López de Subijana et al. (Reference López de Subijana, Barriopedro and Conde2015) found that time management was one of the most challenging factors for athletes in Spain who combine studying and athletics.

Outcomes of Off-Sports-to-Sports Interference

When asked about negative outcomes of off-sports activities, skaters again identified effects stemming from both passive, low-effort, and active, high-effort sports engagement. Skaters linked unilateral engagement in low-effort activities to a lack of focus, feeling slow and lazy, and low energy and reduced performance in their sport. As one athlete described:

lf I do nothing [instead of studying between two same-day training sessions], I feel I’m dozing off and just waiting for my second training. I only really wake up halfway through training.

Another athlete reflected, in relation to a period free of study activities: “Especially in more explosive training sessions, I’d notice I was slower.”

In contrast, it stood out how most skaters initially said they experienced no major negative outcomes of engagement in active high-effort off-sports activities, explicitly identifying enrichment as the dominant process. Still, when prompted, they recalled occasional short-term effects, including reduced focus, fatigue, conflict, and reduced performance. Several athletes recalled instances of reduced focus in training after a busy day of off-sports activities: “I’m a dreamy person, and if I’d had to concentrate on homework for a long time, I noticed I couldn’t keep my focus during training.”

For some athletes, their engagement in off-sports activities resulted in conflict with their coach. They described how their coach would be unsupportive of their off-sports commitments, insisting on full focus on sports: “If you had a training camp and an exam, he’d say: just cancel the exam, you must come to the camp.” One skater, however, explained that—while being frustrating—the conflict with their coach became a drive for proving they could do well in both domains:

No, my performance did not suffer. I did things my way anyway. And then I’d outperform teammates who did listen [to the coach] and I’d think, nice, I showed you.

Finally, underperformance is related to skipping or reduced performance in training or competition. It was mentioned only by athletes who were actively enrolled in school. They described occasions where they skipped training or decided not to skate in a tournament as a last resort when choosing to prioritize study activities (e.g., studying for an exam): “Then I’d skip a practice competition, because otherwise it wouldn’t go well anyway.” And another athlete:

If I could not do my training and my coach said I had to, I just would not. I’m the kind of person who will bend over backwards to make it work, but sometimes I just cannot.

Conditional Factors of Spillover

Athletes identified several factors affecting the likelihood or strength of positive or negative spillover between off-sports and sports domains: (a) autonomy in scheduling, (b) support and flexibility, (c) supporting teammates, (d) intrinsic motivation for off-sports activities, and (e) clear prioritization.

Autonomy, support, and flexibility were often related. Many athletes emphasized the importance of being able to tailor their schedules to successfully combine activities across domains: “You need to go after it yourself, but if you do, most things can be arranged.” Skaters with access to elite sports arrangements at school often benefited from extra time, flexible deadlines, and adjusted attendance requirements: “If I couldn’t take an exam, I could postpone it, so there I had a lot of freedom.” In contrast, lack of flexibility and support were experienced as contextual demands that contributed to interference:

They [school] just do not care. They say they support elite athletes, but they offer nothing. Well, some extra time but otherwise you are on your own.

Supportive teammates helped athletes deal with demands resulting from off-sports activities, especially when they shared similar experiences:

First, I’ll spend some time complaining with my teammates. They all know there’s better days and worse. After, it is nice to let it go and just enjoy skating.

Intrinsic motivation for off-sports activities could also promote enrichment or help reduce interference. One of the skaters explained:

I really wanted to do this because it seemed super interesting. If you know what you want and what’s important to you, it’s easier to combine.

Lack of motivation had the opposite effect, triggering cross-domain interference: “At that time, I didn’t enjoy high school at all, and school and skating both went worse for it.”

Finally, nearly all speed skaters mentioned setting clear priorities as key to managing competing demands:

Sometimes, I can decide what time I train. I always try to work around my lectures, but if it really does not fit, I’ll skip the lecture. Sport is my priority.

Some athletes experienced negative spillover when prioritizing proved impossible. In most cases, this resulted in discontinuing the off-sports activities. For example:

I wanted to finish my studies but just could not combine it. Skating came first. I wasn’t prepared to skip training and could not afford to. As soon as I’d quit studying, I began skating fast the week after.

Illustrative of their elite status, all speed skaters in our sample prioritized their sports over activities in other life domains, while valuing involvement in off-sports mastery activities. To the extent that their choices were understood and supported in both domains, this facilitated off-sports-to-sports enrichment and limited interference.

Discussion

With this study, we aimed to uncover what elite athletes do in their time off from sports and how these activities spill over to affect their sports. Our exploration produced a category framework of off-sports activities and a qualitative analysis of spillover experiences, distinguishing antecedents, linking mechanisms, outcomes, and contextual factors as outlined in the W-HR model (Du et al., Reference Du, Derks and Bakker2018, Reference Du, Bakker and Derks2020; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Reference Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker2012). Highlighting athletes’ own perspectives and experiences, the findings enrich current understanding of off-sports-to-sports spillover in elite sports.

Contributions to Theory

A Framework of Elite Athletes’ Off-Sports Activities

The framework advances eight categories of elite athletes’ off-sports activities: social presence, social engagement, sports, athletic lifestyle, individual mastery, relaxation, gaming, and other activities. These categories span physical (sports, athletic lifestyle, relaxation), social (social presence, engagement), and cognitive (individual mastery, gaming) dimensions. Whereas prior research has emphasized physical aspects of off-sports time, such as rest and sleep (e.g., Halson, Reference Halson2014), the current findings indicate the need for a holistic view that captures the full array of off-sports activities and their implications for the sports domain.

Spillover and recovery theory (e.g., Meijman & Mulder, Reference Meijman, Mulder, Drenth and Thierry1998; Sonnentag et al., Reference Sonnentag, Venz and Casper2017, Reference Sonnentag, Cheng and Parker2022) distinguishes passive low-effort activities from more active higher-effort ones. Passive activities are physically and mentally undemanding and help replenish personal resources (Kellmann et al., Reference Kellmann, Bertollo, Bosquet, Brink, Coutts, Duffield, Erlacher, Halson, Hecksteden, Heidari, Kallus, Meeusen, Mujika, Robazza, Skorski, Venter and Beckmann2018), whereas higher-effort activities can be more demanding (Balk & Englert, Reference Balk and Englert2020) but may expand resources beyond baseline (Sonnentag et al., Reference Sonnentag, Cheng and Parker2022). In our framework, “relaxation” was the only clearly low-effort category, yet it was a large one, accounting for approximately a quarter of all reported activities.

Just over half of the reported activities reflected more active, high-effort social, cognitive, or physical engagement. Many of these activities resembled crafting behaviors; deliberate efforts to align tasks and relationships or job demands and resources with personal needs and abilities (Tims & Bakker, Reference Tims and Bakker2010; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Reference Wrzesniewski and Dutton2001). Although originally applied to work, crafting also occurs in study (Postema et al., Reference Postema, Van Mierlo, Bakker and Barendse2022) and leisure (Petrou & Bakker, Reference Petrou and Bakker2016). The high-effort social activities in our framework align with relational crafting, defined as initiatives to influence the quality or amount of interaction with others (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Reference Wrzesniewski and Dutton2001). Half of the soccer players and speed skaters mentioned deliberate social engagement, often with a purposeful component such as maintaining a social network outside sports.

High-effort cognitive activities comprised individual mastery activities and, tentatively, gaming. Mastery activities focused on learning and development, often unrelated or just loosely related to the athlete’s role. In job crafting terminology, these activities typically involve crafting structural resources and/or challenging demands (Tims et al., Reference Tims, Derks and Bakker2016). Athletes pursued them to gain new skills or expand career options, for example, by learning about real estate or studying medicine. For some, mastery activities also satisfied a need for cognitive challenge, offering enjoyment when working on complex intellectual tasks.

Gaming emerged as a tentative second cognitive category. Most video/computer games have cognitive components such as task-switching, attentional control, and time processing (Nuyens et al., Reference Nuyens, Kuss, Lopez-Fernandez and Griffiths2019). Gaming was frequently reported by soccer players but much less by speed skaters. Because our short-response format with soccer players provided limited detail, we could not distinguish game genres (strategic, social, violent), which vary in activity level, engagement, and impact (Halbrook et al., Reference Halbrook, O’Donnell and Msetfi2019). Depending on athletes’ motives and game genre, gaming could also reflect social engagement (multiplayer formats), mastery (cognitively demanding or strategic games), or athletic lifestyle activities (soccer games, which were popular among the soccer players). Future research should explore the nature and function of gaming for elite athletes and its role in cross-domain spillover.

Comparison of the two samples revealed both similarities and differences in reported activities. All speed skater activities fit the categories derived from the soccer sample, offering preliminary support for the framework’s comprehensiveness. Differences emerged, however, in terms of frequencies. On the one hand, soccer players engaged more in physical and athletic lifestyle activities, which might signal limited detachment from sports. Detachment is vital because it relates to, for example, reduced risk of injury (Balk et al., Reference Balk, de Jonge, Oerlemans and Geurts2017) and can help prevent mental fatigue and motivational decline (Eccles & Kazmier, Reference Eccles and Kazmier2019). Speed skaters, on the other hand, reported more mastery activities, likely reflecting their frequent dual-career engagement. Soccer players also reported mastery activities, but it seems likely that their relatively favorable financial and athletic career prospects reduced their need for parallel study or work (cf., Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Vickers, Fletcher and Taylor2022). Future research should further explore differences between different sports settings in athlete engagement in different types of off-sports activities, also considering motives and situational influences.

Athletes’ Experiences of Off-Sports-to-Sports Enrichment and Interference

The stories that speed skaters shared in the interviews offered an in-depth account of how activities outside their sports could enrich or interfere with their athletic achievements, extending research on recovery (e.g., Balk & Englert, Reference Balk and Englert2020; Sonnentag et al., Reference Sonnentag, Venz and Casper2017, Reference Sonnentag, Cheng and Parker2022), mental rest (Eccles et al., Reference Eccles, Balk, Gretton and Harris2022; Eccles & Kazmier, Reference Eccles and Kazmier2019), and dual careers (e.g., Hallmann & Weustenfeld, Reference Hallmann and Weustenfeld2025). We show how these spillover experiences reflect specific sequences of antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes, illustrating that the basic premises of the W-HR model (Du et al., Reference Du, Derks and Bakker2018, Reference Du, Bakker and Derks2020; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Reference Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker2012) also apply to cross-domain spillover among elite athletes.

Enriching experiences were primarily linked to social engagement and mastery activities, which the skaters identified as essential for meeting their need for cognitive detachment, intellectual challenge, emotion regulation, and physical resources. In turn, these mechanisms could enhance motivational, cognitive, affective, and performance-related outcomes in their sports. Enrichment was thus predominantly associated with active high-effort off-sports activities that can contribute to meaningfulness and distraction (Wilson & Young, Reference Wilson and Young2023) and that recovery research has linked to both detachment and mastery experiences (Sonnentag et al., Reference Sonnentag, Venz and Casper2017). Psychological detachment, in turn, contributes to athlete well-being (Balk et al., Reference Balk, de Jonge, Oerlemans and Geurts2017; Eccles & Kazmier, Reference Eccles and Kazmier2019). Although some mentioned low-effort relaxation when talking about enrichment, skaters did not link it to specific performance benefits, instead considering restful activities a necessary condition for doing elite sports.

Interference was most often linked to over-engagement in either mastery or relaxation activities. Athletes experienced one-sided engagement in relaxation activities as under-stimulating, prompting rumination about sports, lack of detachment, and reduced focus, energy, and performance in the athletic domain. On the other hand, heavy demands from mastery activities would deplete their energy, undermine general well-being, and interfere with mental focus and performance in training or competition. Restful activities are invaluable for high-level athletes, helping them unwind and recover (Stone et al., Reference Stone, Kennedy-Moore and Neale1995). Yet, echoing Wilson and Young’s (Reference Wilson and Young2023) finding that “doing nothing” did not suffice for athlete recovery, speed skaters in our study felt unfulfilled when spending too much time in relaxation and identified this as a direct trigger of cross-domain interference. At the same time, the skaters described how off-sports activities occasionally became overly demanding and undermined their sports efforts. This dual pattern underscores the importance of balancing active, high-effort, and more passive, lower-effort activities during off-sports time.

Achieving such a balance is challenging and requires that athletes identify and use effective strategies (Eccles & Kazmier, Reference Eccles and Kazmier2019), even more so in dual-career settings where sport is combined with study or work (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Vickers, Fletcher and Taylor2022). In shaping their off-sports activities, skaters in our study prioritized strategies that sustained their athletic careers. Many negotiated elite sports arrangements at school and made strategic use of options for flexibility in scheduling coursework, exams, and deadlines. Others deliberately pursued work or leisure activities that allowed easy alignment with training schedules. Overall, the athletic career took precedence, and athletes used different cognitive, social, and physical crafting strategies to organize their study, job, and leisure activities to sustain their sports. Many skaters also described examples of spillover from sports to other life domains, mainly when their sports conflicted with off-sports activities, illustrating the bidirectional nature of spillover.

Finally, context strongly shaped spillover: The same activity could enrich or interfere depending on situational factors such as institutional flexibility, support, and autonomy in scheduling, which have also been identified as facilitators or constraints in more specific dual-career contexts (Hallmann & Weustenfeld, Reference Hallmann and Weustenfeld2025). Lack of support, or conflict over priorities, led to disbalance and overload, which undermined sports outcomes and could result in withdrawal from non-sport activities. When athletes felt supported by academic institutions and advisors, employers, friends, teammates, and/or coaches, they could more readily balance off-sports and sports activities so that off-sports activities could translate into athletic gains.

Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

While our qualitative approach offers rich insight into athletes’ spillover experiences, it also has limitations. First, the category framework was developed from short written responses by the soccer players, often with limited clarification and no opportunity for follow-up. This may have affected the categorization of activities, as illustrated, for example, by the “reading books” activity that we classified under mastery activities but that has also been qualified as a relaxing activity (Sonnentag & Fritz, Reference Sonnentag and Fritz2007). The same activity may have different functions, depending on factors such as target group (e.g., elite athletes versus office workers) or motives for engaging in it. Similarly, the “gaming” category remains preliminary, as different game genres can have different functions and effects (e.g., Halbrook et al., Reference Halbrook, O’Donnell and Msetfi2019; Jin & Li, Reference Jin and Li2017) that we could not identify based on the short responses. Interviews with speed skaters, by contrast, did offer clarification. As such, assignment of these activities to the categories was less ambiguous, as illustrated by the absence of speed skater activities in the social presence category; without exception, their clarification pointed at more deliberate and active social engagement. On the whole, the activities from the speed skater sample fit the initial categories and necessitated no new categories or revised category descriptions, providing tentative support for the framework. The distribution of activities across categories, however, did differ. To further validate and fine-tune the category framework, future research should consider richer data collection methods across different elite sport settings to allow a more detailed and generalizable understanding of athletes’ off-sports activities and motives for engaging in them.

The differences between our two samples also raise questions about the generalizability of off-sports activities and spillover experiences across sport domains. What athletes do off sports and how this affects their sport likely depends on multiple factors. The current findings offer a first glimpse into this largely unexplored territory, but much work remains to be done. As only skaters were interviewed in depth about spillover, we cannot infer soccer players’ experiences. In professional male soccer, players have access to financial and professional resources and career prospects that are unavailable to many other elite athletes, which limits their need to engage in parallel study or work activities (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Vickers, Fletcher and Taylor2022). Sport-specific characteristics may also play a role. Speed skating is a more individual sport with fewer interdependencies among teammates. Among other things, this might allow more room for individualized training arrangements to better align sports requirements with off-sports activities.

Off-sports activities and spillover might also be affected by athletes’ personal circumstances. Women elite athletes, for example, have been shown to face more risk factors for mental health, including caring responsibilities, family planning, and wage disparity (Pascoe et al., Reference Pascoe, Pankowiak, Woessner, Brockett, Hanlon, Spaaij, Robertson, McLachlan and Parker2022), which might influence off-sports activity patterns and spillover experiences. Moreover, research on employee recovery from work suggests that high-duty off-the-job activities such as household or childcare can undermine recovery experiences (Sonnentag et al., Reference Sonnentag, Cheng and Parker2022). Overall, our current observations about off-sports-to-sports spillover processes are specific to elite speed skating, and further research is needed to test their generalizability to other settings and populations.

Spillover is a complex process that requires participants to recognize relevant factors across domains and be aware of whether and how they are related. While interview methods are well-suited for gaining descriptive insights on athlete experiences, mentally reconstructing the spillover processes and mechanisms is challenging in a single interview (Smith & Sparkes, Reference Smith, Sparkes, Smith and Sparkes2016). Future research could add preparatory or follow-up steps to help athletes recall and elaborate on specific experiences and underlying motives. Methods such as day-reconstruction (e.g., Kahneman et al., Reference Kahneman, Krueger, Schkade, Schwarz and Stone2004) or event-based designs (e.g., Morgeson et al., Reference Morgeson, Liu, Cannella, Hillman, Seibert and Tushman2025) could provide valuable tools for this purpose.

Finally, our study was retrospective and interpretative, with athletes describing general activities rather than recounting specific experiences on a day-by-day basis. All participants were active in their elite careers at the time. To advance insight into spillover processes over time, it would be interesting to conduct more longitudinal research at both micro and macro levels. Micro-level studies could use survey and day-reconstruction methods to identify and connect specific occurrences of antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes, in line with the within-person perspective advocated by the W-HR model. Macro-level studies could follow athletes across career phases and transitions. For example, literature shows that combining academics and athletics may have long-term positive effects on well-being after sports retirement (e.g., Torregrosa et al., Reference Torregrosa, Ramis, Pallarés, Azócar and Selva2015). The question may arise whether this is due to athletes’ involvement in academics per se, or more generally to personal development in a non-sports domain. Combining such micro-and macro-level perspectives can also help advance understanding of how athletes can optimize the balance between active, effortful, and passive, lower-effort off-sports activities on both the short (daily or weekly) and longer (season or career) term.

Practical Implications

Our findings show that off-sports activities range from passive, low-effort to more active, high-effort, and can be cognitive, physical, and/or social in nature. Results align with previous qualitative research indicating that rest for athletes involves more than just physical inactivity but can also involve cognitive and/or social activities and experiences (e.g., Eccles & Kazmier, Reference Eccles and Kazmier2019). Our current findings might inform athletes and their trainers/coaches of the wide range of off-sports activities and experiences athletes engage in and their potential to enrich or interfere with athlete well-being and performance. Coaches may consider individual training schedules or other adjustments to support athletes in combining and balancing their sports with their off-sports activities and possibly encourage proactive mastery-oriented off-sports activities to the extent possible. Moreover, clubs could consider facilitating off-sports development by providing crafting or mastery rooms as well as relaxation rooms to stimulate engagement in different off-sports activities.

Conclusion

Athletes engage in a wide variety of off-sports activities that tap into cognitive, social, and physical facets of life. These different types of activities can contribute to interference as well as enrichment from off-sports to sports, depending, in part, on the availability of supportive structures across domains that help athletes balance their involvement in multiple life domains. The category framework may be considered a first step toward developing an in-depth process-view of spillover and well-being among elite athletes. We hope that our findings encourage scholars and practitioners to consider the potency of engagement in off-sports (developmental) opportunities, for athletes’ personal development as well as their athletic achievements.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ariane B. M. Smit for her contribution to the data collection for this study.

Author contribution

A.P.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, formal analysis, writing original draft, project administration; H.v.M.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, analysis, writing—reviewing & editing, project administration, supervision; A.B.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, review & editing, project administration, supervision.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.