I

When considering the history of sight loss in the Post Office (PO), a single figure usually comes to mind: that of Henry Fawcett, ‘the blind postmaster’.Footnote 1 Blinded at the age of twenty-five in 1858, in 1865 he was elected to Parliament, and in 1880 was appointed Postmaster General.Footnote 2 From writings, paintings, and cartoons to sculpture, representations of Fawcett focussed attention on his blindness. Historians of disability have followed suit, using his blindness as a means to interrogate Victorian ideas about sight and visual culture, as well as the role disability played in shaping the biographical subject.Footnote 3

For disability historians, however, Fawcett’s blindness raises two issues. The first concerns the terminology of visual impairment, which spans a continuum from the total absence to the presence of limited sight.Footnote 4 The second concerns the nature and extent of visual impairment more widely. With a few notable exceptions, blindness has continued to dominate discussions of defective vision.Footnote 5 While historians of disability have focussed on blindness itself and the institutional and philanthropic means of providing for those who were deemed to be blind, they have paid less attention to other elements of the continuum, particularly the incidence of poor eyesight and the relationships between visual impairment and work.Footnote 6 For historians of work, Fawcett’s blindness also poses further questions about the relationships between work, the workplace, and types of disability, and about the kinds of industries and occupations which have hitherto been the focus of attention in relation to disability.

In this article, we explore these issues in the context of the British PO, one of the most important branches of the Civil Service and, by the turn of the century, the largest employer in Britain with over 167,000 employees.Footnote 7 Of all the agencies of the state, the PO was the one with which the public interacted most frequently, and because of this, as Patrick Joyce has argued, it also came to represent the state itself.Footnote 8 The efficient functioning of the PO depended on a variety of factors, including the ocular ability of its workforce, and for that reason good vision was an important consideration when recruiting workers and retiring them from service. This was not merely for the sake of efficiency but also because of economy, since mis-sorted mail meant additional costs, and workers who were forced to retire early because of poor vision, along with other conditions, added to the expense of pensions, paid for by the Treasury.

Ocular standards in the service industries, let alone other sectors of the British economy, have rarely attracted historians’ attention. Labour historians concerned with the relationships between work, disability, and industrialization have largely focussed on accidents, injuries, and industrial diseases in the more dangerous trades, such as factory work, mining, or chemicals.Footnote 9 Similarly, the social model of disability, which continues to dominate historical discussions of impairment and work, has tended to focus on physical impairments in the workplace more than sensorial ones.Footnote 10 As a consequence, historians interested in work, together with those concerned with disability, have struggled to identify the extent of impairment at the workplace beyond these so-called ‘dangerous trades’ in which disabled workers were visible reminders of occupational dangers. However, while most histories of disability at work have focussed on these visible physical impairments, other less visible, or even invisible, impairments were no less important, even though they might pose different sets of challenges in relation to the historical record.Footnote 11 The loss of a limb, for example, is a clear form of physical impairment, but poor vision begs the question of degree of sight loss. As Coreen McGuire has remarked, these invisible impairments, such as hearing loss and breathlessness, pose epistemological as well as historical challenges to scholarship.Footnote 12 To this list of largely invisible sensorial impairments we can add defective eyesight. Making visible the extent of this impairment, and addressing these challenges, are the prime concerns of this article.

The lack of attention to eyesight at work emphasizes the importance of situating visual impairment in the tertiary sector as a legitimate field of interest.Footnote 13 Tertiary occupations, such as transport and communications, office work, and retailing, were the fastest growing sector of the British economy in the second half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 14 A priori we might expect these occupations to have a substantial effect on workers’ health, not least because of the round-the-clock nature of employment and the toll that shift work and night time working, which were common elements of labour practices in the PO, takes on the human body and mind.Footnote 15 Exploring the importance of visual impairment in the PO therefore offers an insight not just to the medical but also to the social aspects of disability in a sector that has hitherto largely been ignored in histories of disability.

While poor eyesight attracted widespread public attention in Britain from the 1920s, the roots of those concerns stretched back into the nineteenth century.Footnote 16 As Gemma Almond has recently remarked, better measurement and understanding of visual acuity underpinned ‘the growing demand for enhanced vision in an increasingly visual, modern Victorian world’.Footnote 17 The growing importance of vision during the Victorian period, associated with the expansion of print culture, faster means of transport, the spread of advertising, and shifts in employment, meant that visual acuity assumed a more prominent position as the century progressed.Footnote 18 The first half of this article therefore explores the terminology and significance of deteriorating eyesight within the context of postal work. Using a subset of data drawn from the pension records of 26,500 postal employees who retired between 1860 and 1908, we explore the extent to which poor eyesight was a reason for retirement and how that varied by place, person, and time.Footnote 19 In this context, we explicitly argue that disability associated with poor eyesight was a socially constructed category dependent on the needs of the PO as the employer and its ability to construct workplaces which ameliorated the impact of vision impairment.Footnote 20

The second part of the article therefore addresses the institutional responses and technological landscapes of work which comprised the contexts within which visual impairment needs to be interpreted. In doing so, we are mindful of Chris Otter’s suggestion that histories of light and vision should simultaneously engage with ‘technology, the eye, and politics’.Footnote 21 While poor eyesight was a hindrance to individual workers, it was the bureaucratic and actuarial risks that this posed which motivated the management to take action. Understanding this set of concerns involves examining the importance of medical inspection by PO doctors which worked to exclude those with significant sight loss from postal work. The employment of doctors as medical gatekeepers to employment was a conspicuous feature of how the PO operated from the mid nineteenth century onwards.Footnote 22 However, what was understood to constitute significant or irreparable sight loss varied across government departments, and different definitions served as a point of contention between PO management and the Civil Service Commission (CSC). Here, the case of the partially sighted worker provided the PO authorities with the opportunity to articulate what the doctors it employed saw as the unique sensory demands of postal labour. In other areas, too, the PO sought to address the problem of ill-health and ocular strain through new prophylactic measures, particularly improved lighting. The importance of visibility as well as vision reflected the growing significance of night work in the organization of modern metropolitan life – itself a considerable source of concern in relation to workers’ health – and illuminating workspaces was one aspect of the wider movement to conquer the hours of darkness in the modern city.Footnote 23

II

By calling attention to the broader institutional and technological contexts that went into defining and demarcating defective sight in the PO, this article contributes to a growing historiography that understands the workplace as central to the evolution of different kinds of ‘parameter[s] of impairment’.Footnote 24 We draw on the social model of disability that recognizes a distinction between impairment arising as a result of a physical or mental condition, and disability, which occurs as an outcome of the barriers and constraints imposed on individuals with an impairment that hinders their participation at the workplace or in society more widely.Footnote 25 We also recognize that the history of impairment itself is associated with managerial strategies relating to risks at the workplace. Indeed, as Mara Mills and Dan Bouk argue, the history of impairment ‘is as much bureaucratic and actuarial as it is medical’.Footnote 26 Central to this was the gathering and collation of information relating to workers’ health which involves what Ian Hacking has termed ‘biopower’ – the process by which management or the state more widely identifies individuals with specific levels of medico-actuarial risk based on the assessment of impairment and the ability to undertake tasks.Footnote 27

This process gained shape and gathered momentum in the nineteenth century with the development of more standardized approaches to the collection of medical information about individuals and its uses to minimize actuarial risk against sickness. William Farr was instrumental in establishing this approach during his tenure at the General Register Office, including the creation of a standardized nosology of diseases and its use to estimate actuarial risks.Footnote 28 The approach was also adopted in the PO, where from mid-century the regular monitoring of ill health became a significant feature of bureaucratic strategies to manage the workforce.Footnote 29 Doctors employed by the PO, mainly in a part-time capacity but also on a full-time basis in larger cities, were responsible for examining candidates for office, monitoring their sick leave, providing assistance and, when called upon, to identify workers unable to perform their tasks for medical reasons with a view to recommend retirement. From the early 1890s, the Chief Medical Officer for the PO published annual reports on sickness rates in every post office at which a doctor was employed. The gathering and collation of information about individual employees, which has in part survived by its inclusion on the pension forms of retired workers, forms the evidence upon which this article is based.

III

The same year that Fawcett assumed his role as Postmaster General in 1880, a London sorter by the name of John Cooney retired from the PO due to ‘loss of sight’.Footnote 30 He was joined by H.J. Lawrence, a forty-three-year-old London postman retiring with what was described as chronic ophthalmia – an inflammatory eye condition that could lead to blindness.Footnote 31 Henry J. Turner, too, retired from the PO in 1880 due to ‘defective eyesight’, leaving his position as overseer after twenty-five years’ service. These individuals are just a handful of the 599 workers who retired from the PO between 1860 and 1900 due to some form of sight loss or defective vision.Footnote 32 Between 1860 and 1908, over 26,500 postal workers retired with a pension or gratuity, the majority of whom did so for medical reasons. For the 16,776 individuals who retired before 1900, a short but distinct medical cause of retirement was noted on the pension form, and for these workers we therefore have a precise reason for retirement provided by a medical practitioner.Footnote 33 This evidence provides multiple vantage points from which to study the terminology and historical significance of sight loss. What terms were used by PO doctors to indicate visual impairment? How was poor vision related to age? Was retirement for that reason more common in some places and occupations than others?

Good vision was important in the PO for two main reasons. First, the work itself depended on a high standard of visual acuity. Sorting letters at speed, for example, involved the ability to read handwritten addresses quickly, often in poorly lit offices and frequently at night. In the PO’s Money Branch it was also important to identify numbers and letters clearly to avoid errors. Secondly, as in other branches of the Civil Service, a job in the PO was considered a job for life. Therefore, the authorities had to be confident that recruits were sufficiently healthy to continue in employment for up to forty years, and this depended on, among other criteria, possessing good eyesight with no obvious symptoms of disease. Once they were permanently employed, known as being ‘established’, workers who remained in employment for at least ten years became eligible for a pension. However, in order to join the establishment, applicants not only had to pass the Civil Service exam, they also had to undergo a medical examination, conducted by a doctor employed by the PO.Footnote 34 As Kenneth Macleod, surgeon to the Indian Medical Service, noted in 1895, the doctors tasked with making this assessment did so for three reasons: ‘competency, efficiency, and pensionary liability’.Footnote 35 The PO examination involved questioning the family history of sickness, checking for signs of ill health and vaccination, recording various physical measurements relating to chest size, height and weight, together with tests for hearing and eyesight. The desire to standardize the medical examinations involved clear instructions on how doctors should proceed and included the use of pre-printed forms on which to record the outcomes.Footnote 36 This process of gathering medical information about individuals using standardized methods of examination and categories aligns with what Hacking has described as the exercise of ‘biopower’ – the use of comprehensive measures of biological processes, the incorporation of statistical analyses to identify normal ranges of such processes, and the interventions arising from such knowledge and applied to the entire social body or specific groups.Footnote 37 As Hacking has remarked, ‘counting is hungry for categories’, and in order to achieve categorization, standards are required against which to assess individual outcomes.Footnote 38

IV

Establishing a common standard for testing eyesight, and the use of that information to determine employment outcomes, is a clear example of the exercise of biopower. PO doctors who conducted the initial medical examinations for entry to the permanent workforce were instructed to ensure that candidates had good vision in both eyes, with or without glasses, basing their assessment on the use of Snellen charts or their equivalent which became widely available from the 1860s.Footnote 39 Such charts, first created by Hermann Snellen and published in English for the first time in 1862, included a series of letters of diminishing size that could be read by a person with average visual acuity at a distance of six metres.Footnote 40 This measure, in turn, became the functional norm against which an individual’s eyesight could be measured and compared.Footnote 41 For those occupations that demanded good eyesight, such as the railways, the armed forces, and the PO, establishing this standard was an important yardstick against which to assess whether or not an individual was capable of performing their duties.

From the 1860s it was increasingly common in a variety of Civil Service occupations to test vision using standard Snellen charts. In 1864 the Army ordered one thousand Snellen charts.Footnote 42 In 1877 the Civil Service Commission (CSC) recommended that candidates for the engineering division in naval dockyards should, prior to applying, have a medical examination that included the use of Snellen tests.Footnote 43 The importance of establishing a standard method of assessing vision in recruits to military and government posts was emphasized in 1886 by Sir Joseph Fayrer, then President of the Medical Board of the India Office, who also recommended the use of Snellen charts.Footnote 44 By the late 1880s, therefore, vision testing of recruits using Snellen charts was standard practice in both the armed services and other branches of the Civil Service including the PO. In 1900, Dr Arthur Wilson, Chief Medical Officer at the PO, noted that candidates should have normal vision in both eyes based on the use of Snellen charts.Footnote 45 Glasses could be used to correct defective vision but limits were set as to the nature and strength of the lenses that were necessary in order to see the charts correctly. Wilson noted that in the early 1900s, approximately 20 per cent of applicants required glasses to correct their vision sufficiently to justify being accepted for employment.Footnote 46 This requirement, however, emphasized the importance that the PO placed on a high level of visual acuity, since, as Dr Brudenell Carter noted in his report on children’s eyesight in London conducted in 1896, ‘vision of half the normal acuteness would probably carry the great majority of working people through their daily duties without much inconvenience’.Footnote 47 However, the PO authorities required a higher standard of vision from their employees.

V

While those who began working in the PO were therefore likely to have had relatively good eyesight, with or without glasses, it was not uncommon for defective vision to be cited as the reason for having to retire prematurely on medical grounds. It was the responsibility of the local PO doctors to monitor sickness and to recommend retirement on medical grounds when a condition meant that a worker was no longer able to perform their duties efficiently. The evidence arising from this medical assessment of retirement (included in the pension forms) provides the basis from which to assess the impact of defective vision on the working life of postal employees.

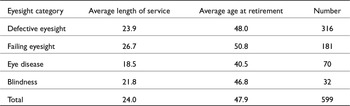

The medical nomenclature that doctors used was by no means standardized and the terminology of vision loss or deficiency used in the pension records was often imprecise and idiosyncratic. Between 1860 and 1900, there were over 260 different separate diagnoses of eye or vision disorders, mainly utilizing phrases such as ‘failing eyesight’, ‘defective vision’, ‘impaired vision’, ‘weak eyes’, ‘affection of the eyes’, or ‘decayed vision’, sometimes together with other conditions. Despite this diversity, these causes fall into four main categories, listed in Table 1, affecting 599 workers who were forced to retire primarily because of vision related disability.Footnote 48 Of this number, the large majority (551) were male employees. Women began to be employed in large numbers after 1870, when the Post Office took over the telegraph companies, but even by the end of the century they only comprised around 20 per cent of the workforce.

Table 1. Eye conditions of postal pensioners, 1860–1900

Source: The Postal Museum, POST 1 Treasury Letters, 1860−1900.

Notes: Defective eyesight includes the general terms: defective, impaired and imperfect vision, weakness of the eyes, weak eyesight, dimness of vision, short sightedness, myopia, amblyopia, astigmatism, cataract, and presbyopia. Failing eyesight includes the term failing or decaying eyesight or vision. Eye disease includes the terms affection, blepharitis, choroiditis, conjunctivitis, corneitis, glaucoma, haemorrhage of the retina, inflammation of the eyes, iritis, keratitis optic atrophy, optic neuritis, ocular paralysis, ophthalmia, ophthalmitis. Blindness includes the term blindness and loss of sight or vision.

Defective eyesight and failing eyesight were the most common categories of vision-related conditions noted on the pension forms, and indeed there is considerable overlap in the use of these terms. However, while both were closely associated with ocular ageing, there were also subtle differences. The term ‘defective eyesight’ or ‘defective vision’, for example, was used on eighty-four occasions, with other terms, such as ‘impaired vision’, ‘imperfect vision’, and ‘weakness of sight’, also contributing to the category along with several other specific conditions such as astigmatism and cataract. These kinds of visual impairments hint at the emerging knowledge that came about with the increased use of the ophthalmoscope and the better understanding of the refractive properties of the eye.Footnote 49 Failing eyesight, by contrast, was often used in conjunction with co-morbidities more closely associated with the ageing process, including failing memory and health, general debility, and senile decay. The average ages associated with each category suggest that different groups of workers were affected: the more chronic types of conditions included in the broad categories of defective and failing eyesight, together with blindness, tended to affect older workers compared to the category of eye diseases, which referred more to acute and inflammatory conditions, such as blepharitis, conjunctivitis, and ophthalmia, which were more common in younger employees.

When broken down by decade the numbers are relatively small, so interpretation of any trend is necessarily tentative, but it is notable that eye diseases became proportionally more common as causes of retirement in the 1880s and, particularly, the 1890s, parallelling the mounting concerns also expressed about poor eyesight in children and wider questions about the fitness of the British population to sustain the imperial race.Footnote 50 At the same time the group of terms related to defective eyesight decreased in importance, with blindness and failing eyesight remaining fairly constant as proportions of eyesight-retirees. Such differences were likely the outcome of a combination of factors, including the invention of the ophthalmoscope in 1851, which led to a significant growth of knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of vision resulting in more specific diagnoses of diseases of the eye. From the 1870s and 1880s, ophthalmology emerged as a specialist field of medicine, and while the doctors employed by the PO tended to be general practitioners rather than specialists, those who were practising in the latter decades of the century would have been exposed to new ophthalmic knowledge as students and also in the medical press of the time.Footnote 51 Meanwhile, as noted above, more precise measurements of visual acuity were being introduced from the 1860s, and this in turn was accompanied by the growing availability of cheap and effective spectacles with which to correct vision, making conditions such as myopia less of a handicap in the workplace.Footnote 52

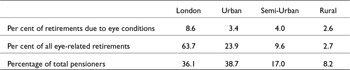

While the diversity of terms used to describe poor vision by PO doctors can be linked to important differences in workers’ ages and length of service, collating these into a single category of ‘poor eyesight’ allows us to gauge its relationship with the characteristics of place and the nature of work. Information about pensioners’ place of work shows that retirement because of poor eyesight was over twice as important in London compared to elsewhere. Table 2 shows that eyesight-related retirements were heavily concentrated in the capital, which accounted for nearly two-thirds of the total, nearly twice as high as the proportion of pensioners from the city. The relative concentration in London is emphasized by the fact that 8.6 per cent of medical retirements of workers there were linked to defective vision compared to between 3.4 and 4 per cent in other types of urban and semi-urban places.

Table 2. Eyesight as a cause of retirement by place, 1860–1900 (per cent)

Source: The Postal Museum, POST 1 Treasury Letters, 1860–1900.

Notes: London is defined as anyone working within the census definition of London for the closest census year; urban defined as anyone working in a town with a population greater than 10,000 in the closest census year; semi-urban defined as anyone working in a location with a population density greater than 0.3 people per acre in the closest census year; rural defined as anyone working in a location with a population density less than 0.3 people per acre in the closest census year. For further information on defining locational category see Harry Smith, ‘Building the Addressing Health Pensions Database’, Addressing Health Working Paper 1 (2023) DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.27152.17920.

There is no reason to believe that environmental conditions in London compared to other urban places were any more or less likely to result in defective eyesight and therefore we need to take into account other factors that could explain the geographical differences in the incidence of eye-related retirements. A key factor is the occupational structure of postal work in each place. Table 3 examines the occupational characteristics of those who retired for reasons to do with poor eyesight. It shows the percentage of the total of all retirees accounted for by each occupational group and compares that to their contribution to the total of eyesight-retirees. The table shows that there were certain occupations where poor eyesight was more likely to lead to retirement, notably sorting, clerical work, and management – all occupations in which reading quickly and accurately was essential. Sorters, in particular, who often worked at night and at high intensity, were more likely than other categories of workers to retire because of poor eyesight. Although they comprised around one in eight of pensioners during our period, they accounted for nearly one in five of those who retired because of visual impairment.

Table 3. Occupational categories of sight retirees, 1860–1900

Source: The Postal Museum, POST 1 Treasury Letters, 1860–1900.

Notes: Figures in bold are occupations whose share of sight-related retirements are higher than their share of all retirements, e.g. clerks make up 10.2 per cent of all retirements but 13 per cent of sight-related retirements. A small number of miscellaneous occupations had no sight-related retirements.

The successful completion of postal work depended on manual dexterity and visual acuity. A sorter, for example, was expected to be able to deal with around two thousand letters a day, and a telegraphist was required to translate thousands of clicks of the telegraph machine into text using a form of typewriter.Footnote 53 In the context of the huge expansion in the volume of mail and messages that took place in the second half of the nineteenth century, pressures of time and space became acute, particularly in the capital. London was where much of the mail posted in the country was sorted, where foreign mail arrived, and where the telegraph system was focussed. It was there, too, that space was in short supply, and the PO struggled throughout the period to balance the rapidly increasing volume of mail which flowed into and out of its central headquarters buildings with the amount of space available. Such pressure on space extended the pressure on time, and it was in London where night-time working and split shifts to manage the amount of work required to sort the mail in a timely manner were most common.Footnote 54 Lighting conditions, therefore, were of great importance, and where illumination was poor, working conditions were more difficult, especially for those with poor eyesight. The fact that London accounted for such a high proportion of eyesight-related causes of retirement, therefore, had less to do with conditions in the city than with the composition of the postal workforce and the nature of work – a reminder that identifying the ‘parameters of impairment’ relies on understanding the context in which it occurs as much as the nature of the condition to which it refers.

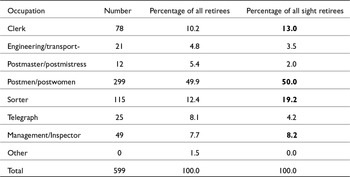

The occupational characteristics of retirees which helped to account for London’s importance were also important in explaining the age at which employees were forced to retire, and here there were variations depending on job type. Age at retirement for vision-related retirees undertaking different roles is shown in Figure 1. For clerks and telegraphists, both of which included comparatively large numbers of women, the age at retirement was relatively low. However, even if female employees were discounted from the calculations, the mean age of retirement for men in these two occupational groupings was 45.3 years for clerks and 42.1 years for telegraphists, compared to an average of 49.5 years for the other occupational groups. Sorters, too, often retired relatively early because of poor eyesight. In these types of jobs, eyesight was of critical importance: clerks often dealt with postal orders, introduced in 1881, and were therefore responsible for financial transactions. The telegraphist’s eyesight needed to be acute to work at the speeds required, so poor vision in both cases was a critical limitation in their ability to continue to work effectively. Sorters often had to work at high intensity, and poor eyesight would also have limited their ability to work at the speeds necessary to deal with the volume of mail in a timely manner.

Figure 1. Age at retirement of vision-related retirees, 1860–1900.

VI

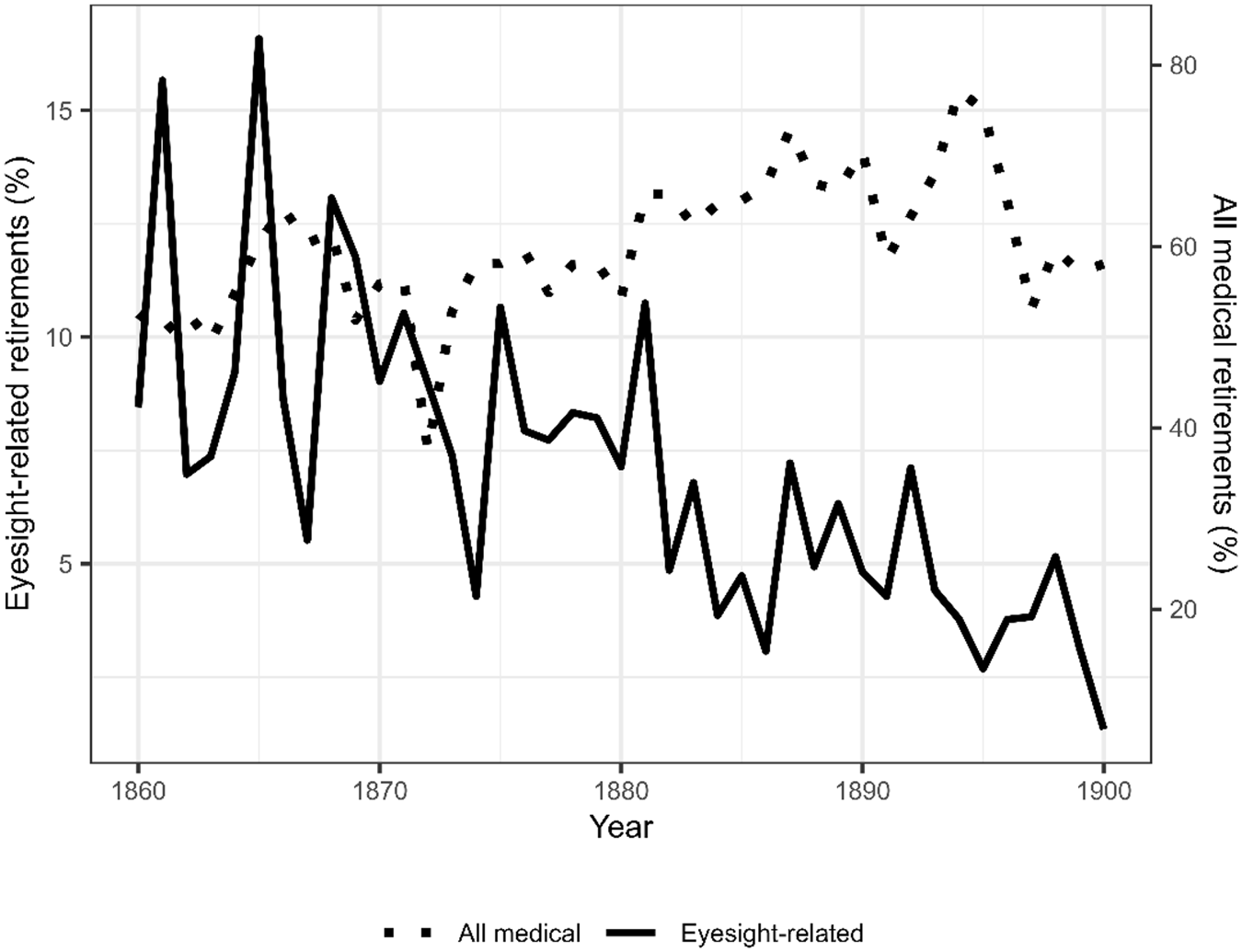

While occupational characteristics largely drove the incidence of poor eyesight as a reason for retirement, its relative importance changed over time. Figure 2 shows the percentage of retirements from postal work for all medical reasons and the share resulting from poor eyesight between 1860 and 1899, the last full year for which data exist. Over the period, retirement on medical grounds rose from around 50 per cent in the 1860s and 1870s to between 60 and 70 per cent in the 1880s, peaking in the 1890s. By contrast, the relative importance of eyesight as a reason for medical retirement fell, from around 10–13 per cent in the 1860s to 8 per cent in the following decade, and to around 5 per cent from the mid-1880s onwards.

Figure 2. Medical and eyesight related retirements, 1860–1899.

The decline in vision-related retirements witnessed in the pensions data was likely to have been the outcome of several factors, including the fact that the growing proportion of retirees who retired for medical reasons could have masked the effects of poor eyesight as a reason for leaving work. It could also have been related to changes in working practices, access to spectacles, and developments in ophthalmic knowledge and treatments. These included efforts by the PO to impose more stringent medical examinations for new recruits, including standard eye tests, as well as efforts to improve lighting, which allowed employees with weak eyesight to continue working for longer than would otherwise have been the case. An important technological change that would have had an impact on the importance of eyesight was improved lighting. As discussed by Kristin Hussey and others, the pressures on space and working practices encouraged the extensive use of artificial illumination, which in turn created the imperfect lighting conditions characteristic of workplaces and living spaces in Victorian cities.Footnote 55 These conditions were especially problematic in the PO. Postal work demanded a light that was constant and capable of allowing employees to inspect a dizzying array of written and printed matter, as well as parcels and telegraphs. Handwriting could be poor, and addresses often difficult to interpret, especially in the foreign mail. Numerous postal tasks therefore demanded a high standard of visual acuity. A rigid regime of visual inspection in particular characterized the task of sorting mail. In the ‘wild sea of letters’ at the sorting department of St Martin-Le-Grand,Footnote 56 sorters had to deal with ‘calligraphic [mysteries]’ in the form of messy handwriting, idiosyncratic abbreviations, and unfamiliar place names.Footnote 57 Telegraphists, too, were seen as victims of undue ocular strain by medical practitioners, with ‘the constant watching and reading telegraphic messages […] causative of strain of the attention and of the visual organs’.Footnote 58 Those who worked as telegraphists, too, linked the technical demands of their role with the ‘great strains on [their] eyesight’, especially when considering the speeds at which they were expected to work (up to 400 words a minute by the late 1890s), and the fact that ‘men are continually employed on Morse slip writing from 6pm to 1.30am, during which time the gas is invariably lit’.Footnote 59

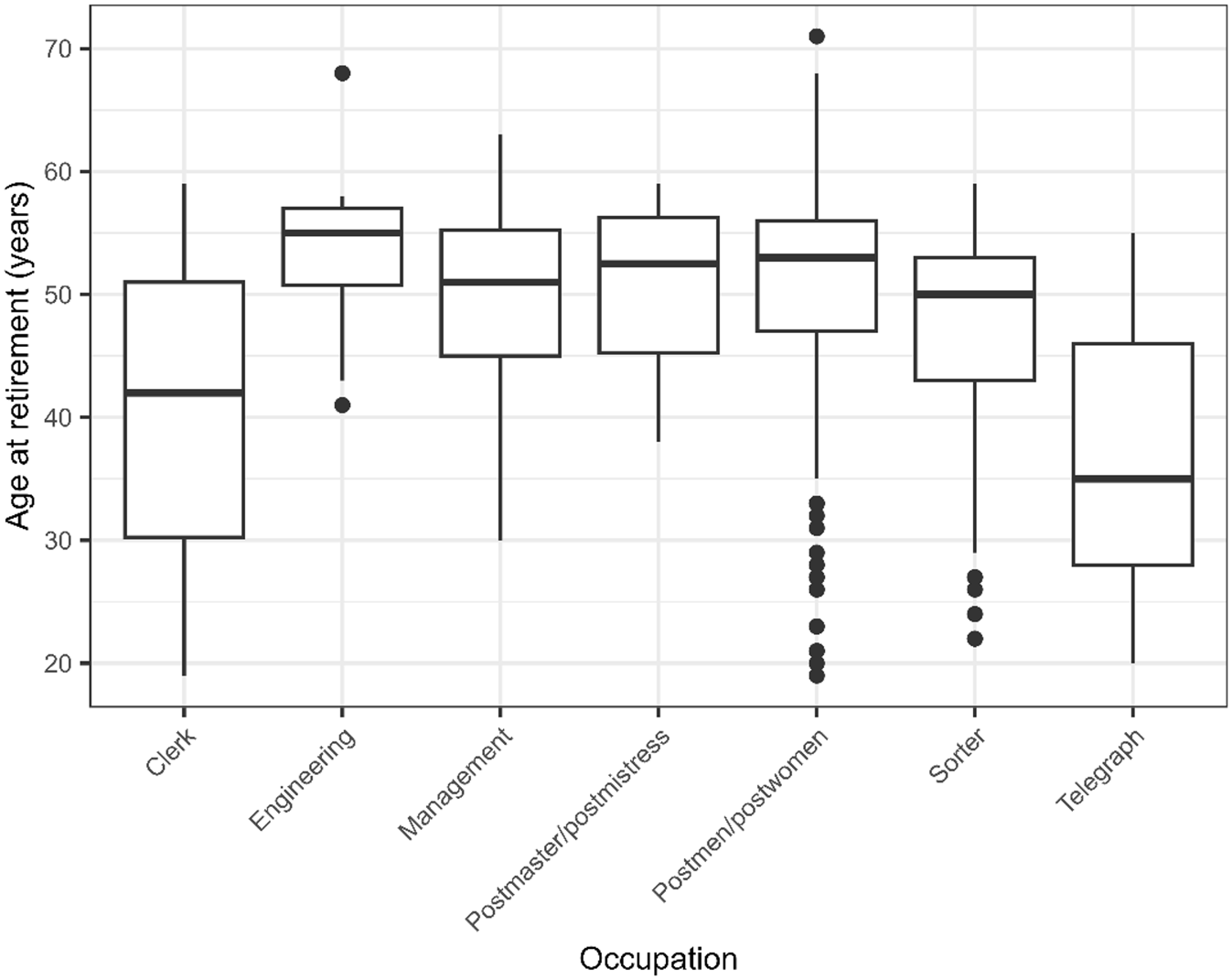

The phenomenon of working by gas (and later, electric) light was discussed by contemporaries as potentially contributing to eyesight problems amongst indoor staff. Otter’s discussion of the ways that ‘technologies of illumination […] shaped the visual experience of numerous forms of labour’ brings to light the various critiques of gas light that were voiced increasingly in the 1880s, both in terms of economy and sanitary conditions, as well as ocular fatigue.Footnote 60 From an early stage there was concern both from the Chief Medical Officer of the PO and from others about the effects of gas light: from the unwanted noise, the excessive heat and the noxious odour that occurred as by-products of the combustion process to the fumes that were thought to deprive the brain of oxygen.Footnote 61 Figure 3 shows the gas burners used in the 1870s to provide light in the main sorting room at the General Post Office in St Martin-le-Grand, including the open windows required to provide adequate ventilation in these spaces.

Figure 3. Sorting and stamping letters at the General Post Office, St Martin-le-Grand, London.

The problems of badly illuminated, poorly-ventilated and overcrowded offices were particularly severe in London and impacted on the workforce in various ways. As the volume of mail arriving and departing from London increased, demands on space needed to sort and deliver the mail rose. Although new offices were opened to ease the pressure on the General Post Office building in St Martin-le-Grand, nevertheless in 1884 a Parliamentary committee warned that within two years the capacity of the central PO buildings would be exceeded and recommended the purchase of a new site to the north of the old building. In the following year a Select Committee, appointed to discuss the feasibility of purchasing further PO accommodation in London, considered the benefits that new offices would provide in terms of protecting the eyesight of indoor staff. In their questioning of Stephen Blackwood, secretary to the PO, members of the committee inquired whether he was ‘aware that the oculist at Christ’s Hospital is employed daily in attending to a great number of persons who have been engaged in underground work in the Post Office’, whose ‘eyesight is impaired in a much less number of years than it would be if they worked above ground?’ Blackwood, however, denied that this was an issue, given that no department in the main building was lit entirely by gas but instead used a combination of gas and natural daylight.Footnote 62 When later questioned, Blackwood produced figures that showed a limited number of cases of affected eyesight in the Inland and Newspaper branches for 1885. He also reported that having ‘questioned a considerable number of the men employed […] none of them attributed any injury to their eyesight from working under gas’.Footnote 63

Despite Blackwood’s insistence that gas lighting did not have a deleterious effect on workers’ health, there was nevertheless enthusiasm for installing electric lighting in the PO. William Preece, Chief Electrician to the PO, was an early if cautious advocate for electric over gas lighting. In an 1879 article in Nature, Preece discussed how – to prove its ultimate superiority over gas light – electric light needed to display a ‘durability greater than that which is required for night operations in England’ and ‘enable work to be conducted without affecting the eyes’.Footnote 64 A year later, under Preece’s watchful eye, Glasgow became the first post office to be electrified, with the sorting and telegraph instrument rooms the first to benefit from ‘the light of the future’.Footnote 65 The reporter from the Glasgow Herald noted that:

The light is most needed in the sorting-room from dusk up to a little after 9 o’clock pm, when the bulk of the day’s work is done. We believe that it is the experience of the sorting clerks and letter-carriers that their indoor labours are greatly facilitated by the excellent light which is abundantly showered down upon them.

Not only that, but the removal of gas lighting also lowered the temperature and noticeably improved the air quality in each of the rooms, resulting in what Preece claimed was better workers’ health.

Electric lighting spread rapidly from that date: in 1881 an experiment using electric lighting in one of the large sorting rooms at the General Post Office building was considered to have been a complete success, and in 1882 the press room, part of the Telegraph Department at the central office, was lit with fifty-nine incandescent bulbs. This noticeable improvement was reported in newspapers: ‘an even light without any shadow was thrown over the tables, while the atmosphere, previously heated by gas, sensibly diminished in temperature, even in the short space of about 20 minutes’.Footnote 66 Following this success, electric lighting spread to other post offices and Preece was keen to buttress his case for investing further, citing its sanitary benefits: ‘those who use it [electric lighting] not only feel all the better for its introduction, but their appetite increases, and their sleep improves, and the visits of the doctor are reduced in frequency’.Footnote 67 Electric lighting, he claimed, would pay for itself by reducing the costs of sick leave and by increasing the amount of work that could be performed.Footnote 68 Robert Bruce, controller of the London Postal Service, agreed, noting in 1906 that the use of electric light in large sorting offices mitigated against eye strain.Footnote 69

While electric lighting appeared to have health benefits, it was also a visible symbol of modernity and evidence of the progressive nature of the PO itself.Footnote 70 However, despite the early successful introduction of electric lighting, its spread was patchy and gas remained in widespread use.Footnote 71 The high costs of electrical installation coupled with improvements in the design of gas lighting meant that for a while gas remained a viable option for lighting many PO premises.Footnote 72 Nevertheless, sanitary concerns continued to provide the impetus to introduce electric lighting in the PO. Several medical officers who responded to a questionnaire sent out by the Tweedmouth Committee in 1896 on the sanitary condition of post offices under their charge still complained about poor ventilation and the build-up of gas fumes, calling for the speedy introduction of electric lighting to address the problem.Footnote 73

In the early years of the twentieth century, electrification in the PO gathered pace. Between 1908 and 1913 the number of post offices lit by electricity almost doubled. The number of electric lamps used in the PO likewise increased from around 13,000 to over 78,000.Footnote 74 Besides being more cost efficient, these electric lamps were found to produce a ‘soft, well-diffused light with comparative absence of shadow and eye-strain’.Footnote 75 The drop in the proportion of retirements because of defective vision was particularly sharp in the early 1880s, at the time when new electric lighting as well as improved gas lighting were being installed in London and other post offices in the country.Footnote 76 While it is impossible to be certain that electrification and falling rates of vision-related retirements were associated, nevertheless it is likely that better lighting in the types of spaces occupied by workers particularly susceptible to sight problems, such as sorters, would have helped to ease the strain on their bodies, and thereby reduce the incidence of poor eyesight as a reason for retirement.

VII

If by the end of the nineteenth century defective vision had become less of an issue in the PO, it was in a different guise that it rose to the fore at the start of the twentieth century. In the early years of the twentieth century the unclear boundaries between functional and non-functional levels of vision became the source of contention between PO management and the CSC, whose instructions regarding the testing of eyesight at the initial medical examination stated that ‘a moderate degree of ordinary short sight corrected by glasses would not as a rule be regarded as a disqualification’.Footnote 77 It also recognized that applicants who had lost the sight of one eye because of an accident at work, rather than a disease, should not be disqualified providing that the other eye was sound.Footnote 78 This was particularly important once employer liability was recognized in the various workmen’s compensation acts that were introduced from 1897 onwards. For the Civil Service as a whole, forcing a worker, who had been injured in the course of their duties but was still capable of undertaking work of some kind, to retire early was a consideration in the decision to keep someone on, even if they had lost an eye.

However, the PO authorities were stricter in the way they interpreted the requirements relating to the loss of an eye. This difference of opinion was due to several cases relating to prospective workers where the remaining eye was functional. In these instances, the CSC took a case-by-case approach, one in which Civil Service candidates would be referred to a specialist to determine the probability of the healthy eye remaining intact. This approach stood in contrast to senior figures in the PO Medical Service, who by the early twentieth century were pursuing a more uniform, exclusionist policy that left little space for bodily difference.Footnote 79 Arthur Sinclair, deputy Chief Medical Officer, wrote in 1907 how ‘in the Postal Service the one eyed man’s usefulness is limited […] his employment as a postman or Counter Clerk is attended with increased risk of loss of letters and stock by theft’. It was, he argued, also impossible to calculate the probability of the single healthy eye remaining unaffected, thus making the worker an ‘early candidate for the pension list’. Sinclair also pointed to the upcoming provisions of the Workmens’ Compensation Act (1908), which could leave the PO open to financial liability in case of further sight loss.Footnote 80 Sinclair’s concerns were shared by Arthur Wilson, then Chief Medical Officer for the PO.Footnote 81

Senior management, too, resisted the CSC’s insistence that the PO align with CSC policy. In a 1911 letter to the CSC, the Postmaster General, Herbert Samuel, wrote that he was ‘of the opinion that the risk of accident for a Postman was materially greater if he has but one effective eye than if he had use of both his eyes, especially if he be employed on outdoor duties in a large town’.Footnote 82 Concerns were not limited to postmen: Wilson maintained that clerical, telegraphic, and telephonic work demanded full and complete eyesight.Footnote 83 The ocular strain that came with navigating both the urban PO and the modern city were, in the PO’s understanding, too risky for workers with sight loss. Because of this, management argued, PO workers constituted a unique group of civil servants in which standards of vision needed to be higher.Footnote 84

The CSC countered, noting that one-eyed candidates for other Civil Service clerkships were not excluded on this basis. They also believed that one-eyed prospective telephonists and telegraphists should not be excluded.Footnote 85 After further pushback from the PO, however, the CSC eventually conceded; they accepted that in cases of a broad class of prospective workers that covered (amongst other roles) telegraphists, telephonists, learners, sorters, postmen, porters, and engineers that a ‘defect of vision will be regarded as a disqualification for these positions’.Footnote 86 A complex matrix of risk, therefore, was at play in PO discussions of the implications of a more liberal policy in employing those with sight loss, one that took into account prospective commercial loss, security, and a legislative environment that made employers financially culpable for workplace accidents after 1908.

VIII

Sight loss provides a means by which to probe the relationships between work, workspaces, and vision-related disability. The relationships between sight loss and employability, however, need to be made cautiously because what constituted and constitutes ‘defective’ vision has varied over time, and depended also on bureaucratic requirements.Footnote 87 Changes in workspaces and the availability of spectacles, for example, meant that the PO clerk whose eyesight might have been considered inadequate in 1861 may not have met the same fate if he had been working some decades later. Focussing on poor eyesight rather than blindness draws attention to the wider issues associated with the complex relationships between impairment, disability, and work. Identifying varying degrees of sight loss in the PO takes us into much wider realms of technology, biology, and politics. It also takes us into issues of spatiality and temporality – of work spaces and work times – which provide the material background to identifying disability. The extension of work into the depths of the night – a necessary requirement as the volume of mail expanded – placed greater strain on workers’ bodies and minds, which resulted in worsening health outcomes in general. Concerns about poor health towards the end of the century, including myopia and other vision-related conditions, coalesced into wider discussions about urban degeneration and physical deterioration. In the PO, the prophylactic measures taken to address those issues, including the use of standardized eye tests in medical examinations, stricter attention to visual acuity as a condition for employment, and improvements in lighting, helped to reduce the impact of deficient eyesight in the workforce. At an individual level, from mid-century, the growing mass production of spectacles brought them within the reach of the working class, including most established postal workers.Footnote 88 Late nineteenth-century improvements in both the understanding and treatment of eye diseases, as well as vision testing, were also likely to have had an impact on the PO employee’s experience of both diagnosis, treatment, and the ability to continue in work.

Alongside these material changes in the ability of individuals with defective eyesight to continue to work, the PO had to balance other considerations. Retirement for medical reasons, including defective and failing vision, highlights the fact that the management of actuarial risk was a key factor in the exercise of biopower by PO management charged with ensuring both economy and efficiency of operations. Eyesight, defective or otherwise, was the focus of a range of concerns in the PO relating to risk, productivity, and economy. To employ workers with poor vision was to run the risk of mis-sorting the mail, mis-spelling telegraph messages or, indeed, mis-counting money. As an organization whose existence depended on public trust, such errors cast doubt on its ability to provide a secure and efficient service. Weeding out those with weak eyesight was an important consideration for the PO authorities, both at the start of employment where doctors were tasked with examining candidates, and at the end when a judgement had to be made about the extent to which workers could continue to undertake their roles in a timely and efficient manner. Neither point of inspection, however, was fixed. Within limits, candidates with defective vision could wear spectacles to correct their eyesight, while better illumination arising from the diffusion of electric lighting as well as improved gas lights could act both to maintain good eyesight as well as prolong the working life of those whose vision was beginning to decline. Achieving a balance between retaining experienced staff with long service records and maintaining a high standard of service, however, required constant attention both to the condition of workers’ bodies as well as that of the workspaces – reminding us that the boundary between impairment and disability at work is a malleable one dependent always on contingent factors related to managerial considerations, individual capacities, workplaces, and the nature of employment itself.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Wellcome Trust for generously funding our project ‘Addressing Health: Morbidity, Mortality, and Occupational Health in the Victorian and Edwardian Post Office’ (Award No. 217755/Z/19/Z). With many thanks to our fellow project colleagues Doug Brown (1977–2021), Kathleen McIlvenna, Nicola Shelton, Joe Chick, Holly Marley, and Natasha Preger. Final thanks go to the anonymous reviewers, who helped us to improve this article at the review stage.