Introduction

For as long as democracy has existed, scholars have debated the merits of government based on expertise versus government based on a popular mandate. Today, this tension is embodied in the contrast between party government and technocratic government (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b).

Party government implies that members of the executive are selected based on their status as party representatives and that their legitimacy rests on their party's electoral mandate (Andeweg, Reference Andeweg, Andeweg, Elgie, Helms, Kaarbo and Müller‐Rommel2020; Mair, Reference Mair2008; Rose, Reference Rose1974). Technocratic government, by contrast, requires that political leaders are chosen based on subject-matter expertise; their legitimacy as politically neutral governors is based on their ability to implement ‘rational’ solutions without being constrained by public opinion (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b; Costa Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Cotta and Almeida2018).

Against this background, recent research on technocratic attitudes in democratic societies presents us with a puzzle: Despite lacking an electoral mandate, technocratic or expert government is surprisingly popular with voters (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2022; Lavezzolo et al., Reference Lavezzolo, Ramiro and Fernández‐Vázquez2021; Vittori, Rojon, et al., Reference Vittori, Rojon, Pilet and Paulis2023). This popularity is puzzling, since technocracy separates government actions from the choices available to voters on the ballot, thus undermining governments' responsiveness and accountability to voters (Müller, Reference Müller2000; Pereira & Öhberg, Reference Pereira and Öhberg2023).

Our investigation of this tension starts from the premise that, in theory, the defining characteristics of technocrats – expertise and party independence – are two independent dimensions, even though the literature often treats them as one perfectly correlated trait (where ministers are either partisan non-experts or non-partisan experts) (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou, Caramani, Bertsou and Caramani2020a; Bertsou & Pastorella, Reference Bertsou and Pastorella2017; Cotta, Reference Cotta, Pinto, Cotta and Almeida2018; Lavezzolo et al., Reference Lavezzolo, Ramiro and Fernández‐Vázquez2022; Rojon et al., Reference Rojon, Pilet, Vittori, Panel and Paulis2023).

While some studies go beyond this one-dimensional perspective (Camerlo & Pérez-Liñán, Reference Camerlo and Pérez‐Liñán2015; Lavezzolo et al., Reference Lavezzolo, Ramiro and Fernández‐Vázquez2021; Vittori, Rojon, et al., Reference Vittori, Rojon, Pilet and Paulis2023), investigating to what extent voters value expertise and (non-)partisanship in a minister, we still know very little about why they do so (e.g., the specific advantages and disadvantages voters associate with government by experts or partisans). Our study thus advances this burgeoning field by engaging with voters' reasoning behind their preferences for different types of ministers. Specifically, we contribute the first study on the perceived upsides and downsides of ministers' expertise and partisanship, allowing for a more nuanced perspective on voter perceptions of technocracy and party government.

In a pre-registered survey experiment, we examine whether manipulating information about a minister's partisanship (partisan vs. non-partisan) and expertise (expert vs. non-expert) affects voters' views of that person's competence along two dimensions: issue competence (the ability to make informed policy decisions in a given area) and bargaining competence (the ability to negotiate political support). Our research design thus allows us to assess both the anti-politics and the expertise basis of technocracy's popular appeal (Bertsou and Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2022).Footnote 1

Our findings suggest that support for technocratic governance is driven not only by the perceived merits of expert ministers but also by the disadvantages voters expect from being governed by party politicians. Holding expertise constant, partisan ministers are viewed as having less issue competence. Moreover, partisanship lowers the effect of expertise on issue competence perceptions, and – in one of two experimental scenarios – on perceived bargaining competence, indicating that voter perceptions of these ministerial traits are not independent from each other. However, such negative evaluations of partisan ministers are neither universal nor unconditional. In line with previous research, the partisanship penalty for issue competence disappears for supporters of the minister's party (Vittori, Rojon, et al., Reference Vittori, Rojon, Pilet and Paulis2023). What is more, partisanship does have important upsides as well. Specifically, partisans are viewed as more effective than non-partisans in political negotiations, which is a crucial component of democratic governance.

Theory

Party democracy is increasingly challenged by a tandem of rivalling forms of political representation: populism and technocracy (Bickerton & Accetti, Reference Bickerton and Accetti2017; Caramani, Reference Caramani2017).

While a rich literature has evolved around the causes and consequences of voters' affinity towards populist ideas (Erisen et al., Reference Erisen, Guidi, Martini, Toprakkiran, Isernia and Littvay2021; Marcos-Marne et al., Reference Marcos‐Marne, Gil de Zúñiga and Borah2022; Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel, Reference Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018, for instance), technocratic attitudes among the electorate have only recently begun to attract scholarly interest (Bertsou and Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2022; Bertsou & Pastorella, Reference Bertsou and Pastorella2017; Chiru & Enyedi, Reference Chiru and Enyedi2022; Ganuza & Font, Reference Ganuza and Font2020; Heyne & Lobo, Reference Heyne and Lobo2021; Lavezzolo et al., Reference Lavezzolo, Ramiro and Fernández‐Vázquez2022; Oana & Bojar, Reference Oana and Bojar2023). Like their populist counterpart, technocratic attitudes are rooted – at least partly – in a critique of party democracy. In the perception of voters holding such attitudes, party government leads to sub-optimal outcomes as party politicians seeking re-election are overly responsive towards particularistic interests when taking government decisions (Bickerton & Accetti, Reference Bickerton and Accetti2017; Caramani, Reference Caramani2017). In contrast, independent subject-matter experts in government are expected to act more responsibly, to identify what is in the general interest of society through ‘rational speculation’ and to implement optimal solutions for societal problems accordingly (Caramani, Reference Caramani2017).

Hence, ideal-typical voters with technocratic attitudes are not only anti-politics, they also assume that there are objective best solutions to many problems. These are accessible through expertise and best implemented by a qualified and politically neutral technocratic elite without much interference from less competent ordinary citizens (Caramani, Reference Caramani2017). Such technocratic attitudes have been found among considerable shares of voters across countries (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2022).

More generally, selecting technocrats for ministerial office resonates well with voter preferences, also beyond the sub-group of voters holding consistent sets of technocratic attitudes (Bertsou, Reference Bertsou2022; Lavezzolo et al., Reference Lavezzolo, Ramiro and Fernández‐Vázquez2022; Rojon et al., Reference Rojon, Pilet, Vittori, Panel and Paulis2023). Expertise, specifically, has been found to be a much desired trait not only for political outsiders in government but for partisan ministers as well (Lavezzolo et al., Reference Lavezzolo, Ramiro and Fernández‐Vázquez2021). Yet, independence from party politics has also been identified as a substantial component of technocrats appeal to voters, particularly when a minister is nominated by a disliked party (Vittori, Rojon, et al., Reference Vittori, Rojon, Pilet and Paulis2023).

Studies indicate that voters in favour of technocracy are less likely to go to the polls overall and that they are more likely to vote for new parties – if they vote at all (Heyne & Lobo, Reference Heyne and Lobo2021; Lavezzolo & Ramiro, Reference Lavezzolo and Ramiro2018). The apparent rise of technocrat ministers, also in ‘political’ cabinets, might thus relate to a growing distrust in parties' capability to govern effectively (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b; Cena & Roccato, Reference Cena and Roccato2023; Habermas, Reference Habermas1973).

Indeed, the appointment of technocratic prime ministers is more likely in times of economic crises and scandals (Wratil & Pastorella, Reference Wratil and Pastorella2018). While party system fragmentation and polarization do not play a role (Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Puleo and Vittori2023; Wratil & Pastorella, Reference Wratil and Pastorella2018), electoral volatility appears to be a significant driver of technocratic appointments (Emanuele et al., Reference Emanuele, Improta, Marino and Verzichelli2022). During crises, technocratic ministers are preferred over experienced politicians under competitive and personalized electoral systems (Alexiadou & Gunaydin, Reference Alexiadou and Gunaydin2019). In Austria, outsider ministers are more likely to be appointed when party support in the bureaucracy is greater, indicating that parties anticipate the risk of losing agency by appointing outsiders (Kaltenegger & Ennser-Jedenastik, Reference Kaltenegger and Ennser‐Jedenastik2022). Lastly, a higher share of populist parties within governments increases the likelihood of technocratic appointments (Pilet et al., Reference Pilet, Puleo and Vittori2023). Notwithstanding institutional and other political determinants, technocratic appointments are thus related to electoral motives: to avoid blame and to restore trust in government (Emanuele et al., Reference Emanuele, Improta, Marino and Verzichelli2022).

Hence, technocratic ministers' expertise and independence may enhance government legitimacy amid party decline. However, the literature has not yet explored why voters value each of the two distinct technocratic attributes. Since previous studies have either focused on technocratic attitudes or had respondents choose between politicians' profiles in survey experiments, we know next to nothing about the specific benefits and drawbacks voters expect from these traits regarding politicians' performance.

We engage with this gap by focusing on voters' perceptions along two dimensions of competence closely related to the defining elements of technocracy: issue competence and bargaining competence. Issue competence (the ability to make informed decisions in a given policy area) should be a function of ministers' expertise. Bargaining competence (the ability to negotiate political support) should primarily relate to their partisanship. Both qualities are essential for a minister's performance in office and should factor into voter evaluations of different ministerial types.

Our reasoning proceeds from the premise that expertise will increase perceptions of competence on both dimensions. The issue-specific knowledge and technical skills ministers have acquired are the natural source of their issue competence. Yet, expertise is also an asset in intra-party and inter-party negotiations as it will increase the authority and credibility of a minister in these processes. Building on this expectation, we test hypotheses on how partisanship and its interactions with expertise and voters' propensity to vote for the minister's party affect their issue and bargaining competence perceptions.

Issue competence

From a technocratic governance perspective, partisan ministers (have to) follow vote- and office-seeking ambitions and are therefore constrained by electoral cycles, the dynamics of public opinion, and inter- and intra-party competition. These constraints limit their ability to make decisions solely based on expertise and to the long-term benefit of society (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b). Partisanship is rejected as it implies compromise and constraints through citizen involvement. This translates into a growing distrust in the general ability of party politicians to govern competently (Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss‐Morse2002). According to this perspective, voters perceive an inherent tension between partisanship and expertise. As Vittori, Rojon, et al. (Reference Vittori, Rojon, Pilet and Paulis2023) show, voters indeed prefer non-partisan over partisan experts, even when they are nominated by their most preferred party. We, therefore, expect that voters infer lower levels of issue competence from partisanship:

1 Hypothesis

Voters perceive partisan ministers as having lower levels of issue competence than non-partisan ministers.

In addition, we expect negative spillover between the two dimensions of partisanship and expertise: The negative view of partisanship that many voters share has the potential to degrade the value of expertise. If partisanship and expertise are seen as fundamentally in tension, the expertise that partisans do bring to the table will be viewed as compromised (in comparison with the ‘untainted’ expertise provided by non-partisans). For the purpose of our study, this implies that an expertise cue will have a smaller effect on perceived issue competence for partisan than for non-partisan ministers:

2 Hypothesis

The positive effect of expertise on issue competence perceptions is lower for partisan ministers than for non-partisan ministers.

Lastly, we expect the effect of minister's partisanship to be moderated by voters' party preferences, as citizens typically process information in ways that do not challenge their political predispositions (Taber & Lodge, Reference Taber and Lodge2006). Notably, partisanship leads to biases in the perception of candidates: Candidates from one's own party are seen as possessing more competence, integrity and empathy than those from the opposing party (Goren, Reference Goren2007; Martin, Reference Martin2022). Likewise, voters prefer non-partisan experts over partisan ones, but less so if they view the respective party more favourably (Vittori, Rojon, et al., Reference Vittori, Rojon, Pilet and Paulis2023). We, therefore, expect that the negative effect of ministers' partisanship on issue competence perceptions should diminish for supporters of a minister's party.

3 Hypothesis

The negative effect of partisanship on perceived issue competence is lower for party supporters than for other respondents.

Bargaining competence

Our second dimension of competence refers to a minister's bargaining competence – the ability to negotiate support for their policy proposals from other actors in the political system. While individual ministers have substantial discretion over decisions in their ministry (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Müller, Angelova and Strobl2022; Laver & Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1990, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996), their power to implement policies is not absolute. Notwithstanding the substantive qualities of a policy proposal, turning these proposals into policy output typically requires the support of the appointing party (e.g., in the cabinet and the legislature) as well as the consent of coalition partners and other veto players.Footnote 2

Establishing such support coalitions is not a trivial task and should be easier for a minister with greater political weight. Accordingly, Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2016) argues that high-ranking party politicians are amongst the most effective ministers in terms of producing their desired policy outcomes, due to their ability to override opposition in intra-party and inter-party negotiations. While such politicians have the most effective means to pressure other actors into accepting their demands (e.g., formal intra-party decision-making powers, mobilizing potential), they also have established political networks and a deeper understanding of party platforms and electoral constraints. These features will help party insiders negotiate with other political actors and to be seen as more competent brokers than non-partisan ministers.

4 Hypothesis

Voters perceive partisan ministers as having higher bargaining competence than non-partisan ministers.

In contrast to issue competence, we expect positive spillover between partisanship and expertise on perceived bargaining competence. While voters may perceive partisanship as a constraint on rational decision-making, there should be no analogous tension between expertise and a minister's performance in intra-party and inter-party bargaining. On the contrary, expertise may endow partisans with even greater authority in negotiations with their political counterparts. In line with Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2016, p. 26 et seq.), ministers combining the traits of a party politician with issue-specific expertise – ‘technopols’ (Lavezzolo et al., Reference Lavezzolo, Ramiro and Fernández‐Vázquez2021) – might therefore be the most effective ministerial type in terms of implementing their preferred policies, as they should be able to make better political use of their expertise than non-partisans.

5 Hypothesis

The positive effect of expertise on bargaining competence is higher for partisan than for non-partisan ministers.

Empirical strategy

We test our hypotheses based on a survey experiment fielded in Austria between 10 and 26 October 2022 (

![]() $n=3,072$) (Partheymüller et al., Reference Partheymüller, Aichholzer, Kritzinger, Wagner, Plescia, Eberl, Meyer, Berk, Büttner, Boomgaarden and Müller2022).Footnote 3

$n=3,072$) (Partheymüller et al., Reference Partheymüller, Aichholzer, Kritzinger, Wagner, Plescia, Eberl, Meyer, Berk, Büttner, Boomgaarden and Müller2022).Footnote 3

Austria is a typical party democracy with exceptionally strong parties (Scarrow et al., Reference Scarrow, Webb and Poguntke2017) and predominantly partisan appointments to government office. However, Austrian voters are comparatively well-accustomed to moderate shares of technocrats in cabinets (Emanuele et al., Reference Emanuele, Improta, Marino and Verzichelli2022). While overall 11 per cent of Austrian ministers (1945–2020) fall into the technocrat category, the country has in recent decades experienced a substantial increase in technocratic appointments (Kaltenegger & Ennser-Jedenastik, Reference Kaltenegger and Ennser‐Jedenastik2022) (see the online Appendix, Figure A2). Austria is suitable to explore voters' preferences for different types of ministers as its citizens are familiar with technocratic ministers and because it is comparable to several other European countries in that regard (see the online Appendix, Figure A5).

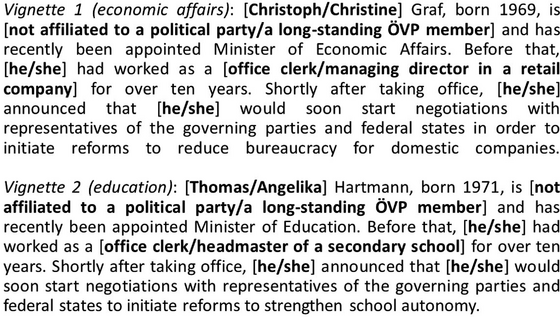

We use a two-by-two survey-experimental design that randomizes a minister's partisanship and portfolio-specific expertise.Footnote 4 Each respondent was shown two versions of the experimental vignette: one describing a recently appointed minister of economic affairs and the other describing a recently appointed minister of education. We deliberately chose valence-type issues to prevent respondents' perceptions of competence from being shaped by policy positions with which they may strongly agree or disagree. Both portfolios are comparatively likely to see technocratic appointments (Costa Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Cotta and Almeida2018; Vittori, Pilet, et al., Reference Vittori, Pilet, Rojon and Paulis2023) and were held by technocrats in the Austrian government during the data collection phase of the survey, thus ensuring high internal validity.

Ministers were assigned to be either non-partisans or long-standing members of the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP), the party holding the most important ministerial positions when the survey was fielded.Footnote 5 The focus on the ÖVP provides a high degree of internal validity, yet may come at the expense of external validity. However, because the party has a long history of government participation and is a party whose reputation for handling policy issues is known to voters, a certain degree of external validity is ensured. The mainstream, highly institutionalized character of the party makes it the typical party subject to the technocratic critique of party government and therefore a good fit for our analysis. While voters traditionally consider the ÖVP to be competent on economic policy issues, this applies to a much lesser extent to education policy (Meyer & Müller, Reference Meyer and Müller2013; Wagner & Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2015). Hence, the choice of ministerial portfolios in our research design allows us to account for discrepancies in perceived issue competence at the party level at least to some extent.

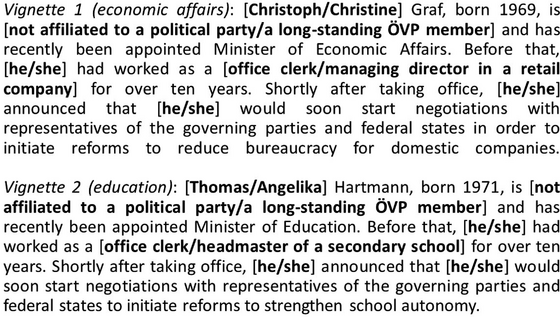

As expertise treatment, ministers were assigned prior job experience either as office clerks or as managing director in a retail company (in the economic affairs scenario) or headmaster of a secondary school (in the education scenario). All ministers in the vignettes announce negotiations with other government representatives and the federal states to initiate reforms in their policy areas. Figure 1 presents the English-language versions of the vignettes.

We then ask two outcome questions in random order:

Figure 1. Experimental vignettes for the two portfolios.

Issue competence question: ‘How much subject-matter expertise do you think [NAME] has for his/her work as Minister of Economic Affairs/Education?'

Bargaining competence question: ‘How much support do you think [NAME] will get from the governing parties and states for the planned reform?'

Responses were recorded on 11-point scales, ranging from 0 (‘has no subject-matter expertise’, ‘will get no support at all') to 10 (‘has a lot of subject-matter expertise’, ‘will get a lot of support for the reform'). These are the dependent variables in our analyses. We provide an overview of the number of respondents per experimental condition in the online Appendix.

Analysis

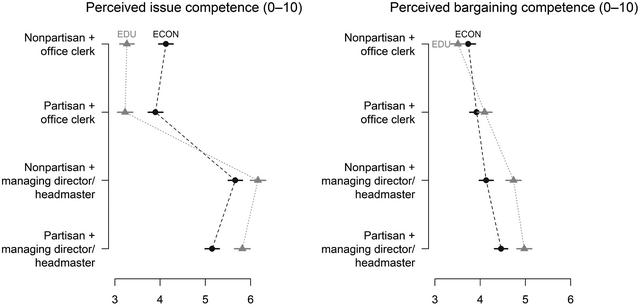

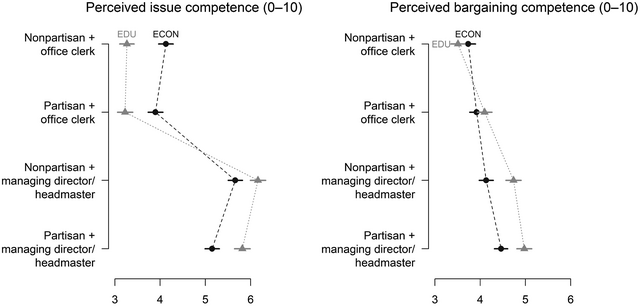

Figure 2 presents means and standard errors for the two outcome variables, issue competence and bargaining competence, in all experimental conditions. First, compared with the ‘office clerk’ baseline, perceived levels of issue competence jump markedly in the ‘managing director’ and (even more so) in the ‘headmaster’ condition. This, of course, is in line with our premise: expertise should boost perceived levels of issue competence.

In addition, issue competence perceptions are, on balance, somewhat lower in the partisan conditions than in the non-partisan ones. This suggests that partisanship has a negative impact on perceived issue competence independent of actual experience. A closer inspection of the left-hand panel in Figure 2 reveals that the gap between partisan and non-partisan ministers is smaller in the ‘office clerk’ conditions than in the conditions featuring the expertise treatments.

Figure 2. Perceived levels of issue competence and bargaining competence across experimental conditions.

Note: Means and standard errors.

By contrast, there is no partisanship penalty for perceptions of bargaining competence. In both scenarios, partisanship and expertise have a positive impact on perceived bargaining competence. As expected, voters thus view partisans with portfolio-specific expertise as the most effective negotiators.

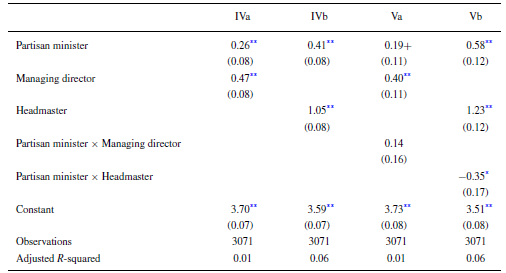

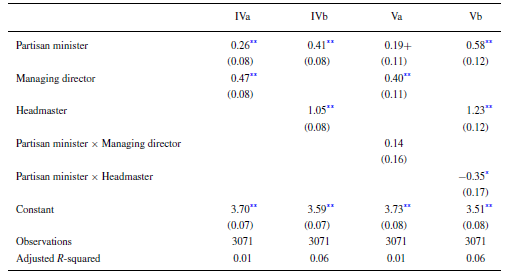

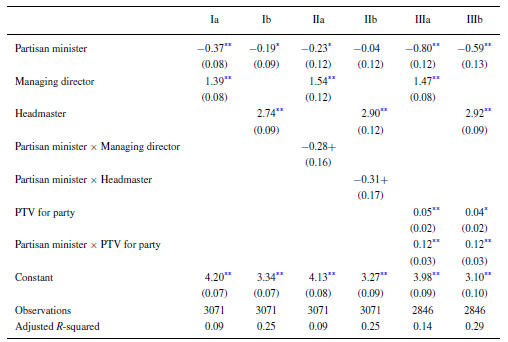

While Figure 2 produces results that align well with some of our hypotheses, we specify linear regression models for a more formal test. We use perceived issue (Table 1) and bargaining competence (Table 2) as the dependent variables. Models marked with an ‘a’ (Ia, IIa,…) refer to the economic affairs vignettes, whereas models marked with a ‘b’ (Ib, IIb,…) refer to the education vignettes.

Table 2. Regression analysis: Treatment effects on perceived bargaining competence

Note: Coefficients and standard errors from OLS models; ![]() $^{+}$

$^{+}$![]() $p<0.1$, *

$p<0.1$, *![]() $p<0.05$, **

$p<0.05$, **![]() $p<0.01$.

$p<0.01$.

Models marked with an ‘a’: economic affairs, models marked with a ‘b’: education.

Abbreviation: OLS, ordinary least squares.

Table 1. Regression analysis: Treatment effects on perceived issue competence

Note: Entries are coefficients and standard errors from OLS models;

![]() $^{+}$

$^{+}$

![]() $p<0.1$, *

$p<0.1$, *

![]() $p<0.05$, **

$p<0.05$, **

![]() $p<0.01$

$p<0.01$

Models marked with an ‘a’: economic affairs, models marked with a ‘b’: education.

Abbreviations: OLS, ordinary least squares; PTV, propensity to vote.

To test H1 (partisanship decreases perceived issue competence), models Ia and Ib include predictors for the partisanship and the respective job experience treatments in the two versions of the vignette. Whereas experience as managing director or headmaster naturally increases perceived levels of issue competence by a substantial amount (1.4–2.7 scale points), there is a negative and statistically significant effect of partisanship: Notwithstanding their expertise, ministers with a party affiliation are viewed as less competent by 0.2–0.4 scale points on average (between 7 per cent and 16 per cent of a standard deviation). These findings provide clear support for H1.

In order to test H2 (the positive effect of expertise on issue competence is weaker for partisans), models IIa and IIb include interactions between the partisanship and the managing director/headmaster predictors. While the direct effects in model IIa resemble those found in model Ia, the effect of partisanship disappears in the education scenario (model IIb) when including the interaction term. This means that the partisanship penalty in model IIb is only present for ministers with expertise.

The interaction terms in both models are negative, though only significant at the 10 per cent level (![]() $p=0.086$ and

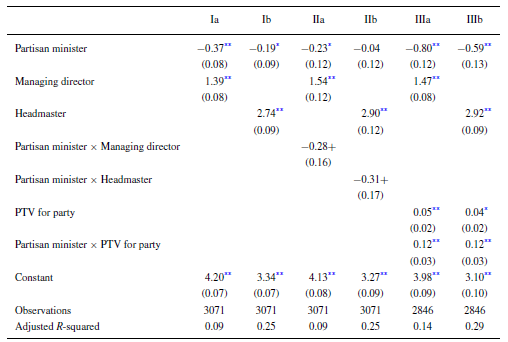

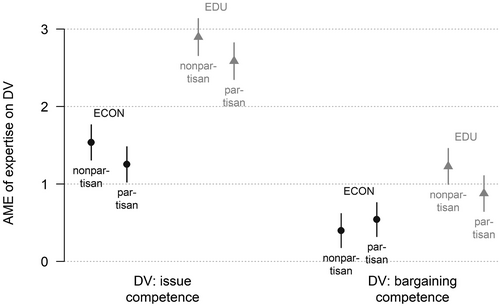

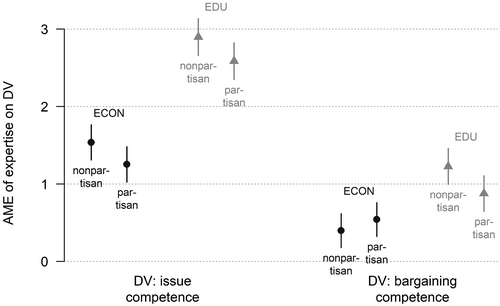

$p=0.086$ and ![]() $p=0.074$, respectively).Footnote 6 The average marginal effect (AME) of having relevant job experience on perceived issue competence is substantially lower for partisans than for nonpartisans: 1.25 versus 1.53 for economic affairs and 2.90 versus 2.59 for education (see Figure 3). The partisanship treatment thus reduces the AME of relevant job experience by 18 per cent (economic affairs) and 11 per cent (education), respectively. Not only do voters view partisan ministers as less competent, they also value their portfolio-specific expertise less than they do in non-partisans. Partisanship thus taints the value of subject-matter knowledge in politicians, as expected in H2.

$p=0.074$, respectively).Footnote 6 The average marginal effect (AME) of having relevant job experience on perceived issue competence is substantially lower for partisans than for nonpartisans: 1.25 versus 1.53 for economic affairs and 2.90 versus 2.59 for education (see Figure 3). The partisanship treatment thus reduces the AME of relevant job experience by 18 per cent (economic affairs) and 11 per cent (education), respectively. Not only do voters view partisan ministers as less competent, they also value their portfolio-specific expertise less than they do in non-partisans. Partisanship thus taints the value of subject-matter knowledge in politicians, as expected in H2.

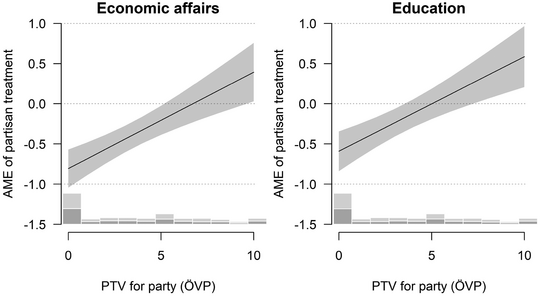

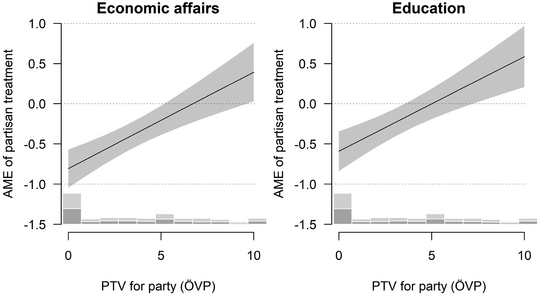

H3 posits that perceived issue competence is shaped by voters’ attitudes towards the party: party sympathizers should display a smaller ‘partisanship penalty’ than non-sympathizers. We test this hypothesis by interacting the partisan treatments with an item capturing the propensity to vote (PTV) for the ÖVP on a scale from 0 to 10. This interaction term is positive and statistically significant for both vignettes. To evaluate H3, Figure 4 displays the average marginal effect of the partisan treatment across the empirical range of the PTV variable.

Figure 3. Average marginal effect (AME) of expertise treatment on perceptions of issue and bargaining competence by partisanship.

Note: AMEs with 95 per cent confidence intervals, based on models IIa and IIb in Table 1 and models Va and Vb in Table 2. Tests of the difference between non-partisan and partisan AMEs yield p-values of 0.083, 0.070, 0.374 and 0.038, respectively.

Figure 4. Average marginal effect of partisan treatment on perceived issue competence by propensity to vote (PTV) for the ÖVP.

Note: AMEs with 95 per cent confidence intervals, based on models IIIa and IIIb in Table 1. Bars indicate the distribution of the PTV variable for cases with (light grey) and without (dark grey) the partisan treatment (median number of cases per cell = 129).

In both scenarios, PTV is a strong moderator of the partisan treatment. The partisanship penalty is largest for respondents least likely to vote for the minister's party (ÖVP) but shrinks to zero at higher PTV levels (even nudging into positive territory in the education scenario). This suggests that the mechanism behind our findings for H1 is not generic anti-party sentiment, but the sentiment towards a specific party. Non-partisan ministers are at an advantage because they can more easily avoid hostility from out-partisans and are thus more acceptable to a larger group of respondents.

Next, we turn to the hypotheses pertaining to bargaining competence. H4 conjectures that partisan ministers will be viewed as more competent in negotiating support for their policy proposals. This hypothesis is supported by the results of models IVa and IVb in Table 2. In both estimations, the partisanship treatment returns a positive and statistically significant coefficient. Respondents award partisan ministers a 0.26-point (economic affairs) and 0.41-point (education) higher score on bargaining competence than their non-partisan counterparts. In line with our expectation, there are thus positive qualities associated with partisanship. Partisanship is not simply a generically unfavourable attribute that produces negative valence in all contexts, as voters differentiate between different requirements for government office.

Finally, we expect a positive interaction between expertise and partisanship on bargaining competence (H5). However, models Va and Vb in Table 2 display non-significant and negative coefficients, respectively.Footnote 7 The average marginal effects calculated from these models are reported in Figure 3 above (right-hand side). In the economic affairs scenario, partisanship does not modify the effect of expertise: the AMEs of expertise are very similar for partisan and non-partisan ministers. In the education scenario, however, we find that partisanship decreases the effect of expertise on bargaining competence. Similar to the effects found for issue competence, the competence boost that ministers gain from their expertise is smaller for partisan ministers than for non-partisan ones. These findings clearly contradict H5.

Conclusion

Why do people like technocrats? We have broken down this question along two dimensions: issue competence and bargaining competence.

Our findings suggest that the relationship between ministers’ expertise and partisanship and voters’ competence perceptions is complex. To start with, there is a clear trade-off between partisanship and perceived issue competence: Voters believe that partisan ministers have lower issue competence, irrespective of ministers’ actual expertise – an effect driven by out-party supporters (see also Vittori, Rojon, et al., Reference Vittori, Rojon, Pilet and Paulis2023). In addition, ministers' expertise becomes less valuable (in terms of boosting issue competence perceptions) if the minister is a partisan as opposed to a non-partisan.

These findings suggest that technocrats' perceived issue competence is not merely a function of their expertise but also a function of their party independence. Thus, even on the dimension most directly linked to the expertise aspect of technocracy (issue competence), partisanship plays an important role in shaping voter attitudes. Thus, voters do not evaluate expertise and non-partisanship independently of each other. Instead, there is attitudinal spillover from one dimension of technocracy (non-partisanship) to the other (expertise). This ‘partisanship penalty’ implies that voters accept the technocratic critique that views party politicians as constrained by public opinion and electoral cycles, which deflects partisan experts from making decisions based on their expertise (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020b).

In contrast, we find that bargaining competence (a more ‘political’ trait) is positively affected by partisanship. Voters view partisan ministers as more likely to attain their policy goals when bargaining with other political actors. Partisanship is thus no disadvantage across the board but matters in dimension-specific ways. However, contrary to our expectations, we also find a trade-off between the effects of expertise and partisanship in one of our two scenarios: In the education-portfolio version of the experiment, partisanship decreases the positive impact of expertise on bargaining competence.

While in the former case, our findings confirm the view that party politicians are perceived, at least by voters, as the most effective ministers in terms of achieving their policy goals (Alexiadou, Reference Alexiadou2016), the latter finding challenges this view. It appears that, for certain issues, non-partisan experts are actually perceived as having higher bargaining competence than partisan experts. One possible explanation is that voters may see some issues as more politicized – and thus legitimately subject to the logic of party politics – than others. For less politicized issues, partisanship and expertise may be seen as in tension when it comes to achieving negotiation success.

A noteworthy limitation of our study is the measurement of bargaining competence. Our first attempt to capture perceptions of ministers' bargaining competence focuses on outcomes but does not address how politicians achieve them. Respondents who answered ‘will get a lot of support’ may perceive party politicians as effective either through legitimate means or malpractice. This distinction is not captured by our current measure and thus merits further research. An additional limitation is related to effect sizes. While the effects are small, these effect sizes are consistent with the subtle nature of the treatments.Footnote 8 In reality, voters would have access to more information (e.g., ministerial performance), so the subtle treatments increase external validity. Another limitation is the focus on one party, the ÖVP. While focusing on a currently governing party ensures high internal validity, it reduces external validity. Specifically, we do not know how different party-level characteristics would have affected respondents' competence evaluations, making it unclear to what extent our findings generalize. However, we believe our findings are relevant for similar mainstream, conservative parties – especially since such parties in Eastern and Western Europe have appointed technocrats to a similar extent as the ÖVP (see the online Appendix, Figure A6).

Overall, our results support the view that technocracy is best conceptualized as a multi-dimensional phenomenon encompassing both, expertise and party independence (Bertsou & Caramani, Reference Bertsou, Caramani, Bertsou and Caramani2020a; Vittori, Rojon, et al., Reference Vittori, Rojon, Pilet and Paulis2023). However, in the eyes of voters, these dimensions are not completely separate, but affect each other, as a minister's partisanship boosts some dimensions of perceived competence (bargaining competence) but decreases others (issue competence). These spillover effects provide an empirical rationale for the strategic use of technocratic appointments to enhance a government's perceived issue competence. However, forgoing partisan appointments may come at a price in other competence dimensions, as non-partisan ministers are viewed as less effective negotiators.

Acknowledgements

We thank the team of the AUTNES Online Panel Study for incorporating our survey module into wave 15 (10–26 October 2022). The data collection for the elections of 2017 and 2019 in the AUTNES Online Panel Study was supported by ACIER – Austrian Cooperative Infrastructure for Electoral Research, which received funding from the Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economic Affairs (BMWFW) through the Hochschulraum-Strukturmittel 2016 scheme. The continued data collection from 2022 onwards was made possible through the cooperative Digitize! project, funded by the Federal Ministry of Education, Science, and Research (BMBWF). Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik and Jeanne Marlier gratefully acknowledge funding through the https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/945501 DEPART project (European Research Council grant no. 954401). Matthias Kaltenegger gratefully acknowledges funding through the PARTY CONGRESS POLITICS project (Austrian Science Fund grant no. P33596-G).

Online Appendix

Table A1: Pooled regression models

Table A2: Number of respondents per experimental condition

Table A3: Summary statistics: competence perceptions

Figure A1: Anti-party sentiment, support for binding policy decisions by experts and PTV for the OVP

Table A4: Correlations between dependent variables

Table A5: Power calculations per dependent variables and portfolios

Figure A2: Shares of technocrats among Austrian ministers by decade (1945-2020)

Figure A3: Number of appointed technocrat ministers by Austrian parties (1945-2020)

Figure A4: Shares of technocrat ministers in selected portfolios by Austrian parties (1945-2020)

Figure A5: Average share of technocrat ministers in Europe (1997-2022) (Vittori, Puleo, Pilet, Rojon, Paulis and Panel, Reference Rojon, Pilet, Vittori, Panel and Paulis2023)

Figure A6: Average share of technocrat ministers in right-wing European government (1997-2022) (Vittori, Puleo, Pilet, Rojon, Paulis and Panel, Reference Rojon, Pilet, Vittori, Panel and Paulis2023)

Table A6: Regression analysis: effects of partisan treatments on bargaining competence, conditional on propensity to vote (PTV)

Table A7: Regression analysis: effects of partisan treatments on issue competence, conditional on anti-party sentiment

Table A8: Regression analysis: effects of partisan treatments on issue and bargaining competence, conditional on ministers' gender

Table A9: Regression analysis: effects of partisan treatments and ministers' gender on issue competence, by respondent gender

Table A10: Regression analysis: effects of partisan treatments and ministers' gender on bargaining competence, by respondent gender

Table A11: Regression analysis: interaction effects of ministers' gender and respondent age on issue and bargaining competence

Table A12: Regression analysis: interaction effects of partisan and ministers' gender on issue competence, by respondent gender