Introduction

The prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) has reached epidemic proportions and continues to increase. Globally, NCDs are the leading cause of premature mortality and preventable morbidity. 1 Associated health, social, and financial costs – estimated to reach US$47 trillion between 2010 and 2030 – represent a double blow for low- and middle-income economies already stretched by infectious disease management. Reference Emadi, Delavari and Bayati2,3

NCDs, often referred to as chronic diseases, originate from a combination of environmental, behavioural, genetic, and physiological influences. They are usually slow to emerge and are of long duration. 4,5 The primary categories of NCDs include cardiovascular diseases like heart attacks and strokes, various cancers, diabetes, and respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. 4 Although typically viewed as adult-onset diseases, it is increasingly clear that the development of these conditions is influenced by the pre-conception environment (maternal and paternal, including diet, exercise, stress and toxic load) through to birth and the individual’s postnatal environment right through to adolescence. Reference Hanson and Gluckman6,Reference Shonkoff, Boyce and McEwen7 Evidence from the field of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) identifies the epigenetic mechanisms through which environmental exposures during these key developmental stages influence long-term metabolic health.

This life-course view of disease pathogenesis offers avenues for potential prevention when considered across multiple generations, recognising the complex interplay of biological, cultural, and socioecological factors affecting an individual’s health throughout the lifespan. Reference Goyal, Limesand and Goyal8,Reference Low, Gluckman and Hanson9 This approach emphasises societal and governmental responsibility in supporting preventive health programmes and reduces the perception of individual, particularly maternal, blame for disease. Reference Richardson, Daniels and Gillman10,Reference Sharp, Lawlor and Richardson11 However, systemic change requires both the public and policymakers to engage with DOHaD evidence and consider its implications for decision-making at all levels of society. Reference Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey and Walshe12

Effective knowledge translation requires robust baseline data to inform targeted messaging and evaluate intervention impacts over time. Reference Mayne, Lindkvist, Forss and MacGillivray13,Reference Vandiver14 The Public Understanding of DOHaD (PUD) project, initiated in 2014, aimed to develop a method of measuring awareness of NCD and DOHaD concepts in diverse populations using a standardised questionnaire adapted to suit each setting. A 2022 systematic review found no comparable equivalent to the PUD survey tool. Reference Hildreth, Vickers, Buklijas and Bay15 Of the seven quantitative or mixed-methods studies identified, one included only three questions relating to DOHaD knowledge as part of a wider questionnaire, Reference Grace, Woods-Townsend and Griffiths16 one considered only postnatal risk factors, Reference Gage, Raats and Williams17 and one conflated knowledge of nutritional and parenting guidelines with DOHaD awareness. Reference Bagheri, Nakhaee, Jahani and Khajouei18 Two studies utilised the PUD survey tool, as described here. Reference Bay, Mora, Sloboda, Morton, Vickers and Gluckman19,Reference Oyamada, Lim, Dixon, Wall and Bay20 The remaining two studies used a similar questionnaire design but for different purposes: Lynch et al. explored DOHaD awareness in relation to broader epigenetics concepts, Reference Lynch, Lewis, Macciocca and Craig21 and McKerracher et al. calculated an overall DOHaD knowledge score for each participant for comparison with a prenatal nutrition knowledge score. Reference McKerracher, Moffat and Barker22 Two further studies published since 2022 also use either the PUD survey tool Reference Tohi, Tu’akoi and Vickers23 or the scoring method developed by McKerracher et al. Reference Salvesen, Valen and Wills24 In 2023, Ku et al. described a new tool specifically for use with health professionals, designed to evaluate DOHaD knowledge and attitudes and how these inform clinical practice. Reference Ku, Kwek and Loo25,Reference Chan, Jia Heng and Zheng26

During the 10+ years the PUD tool has been in use, multiple DOHaD researchers have expressed interest in adapting it for use in their local context. In order to support effective translation and robust application of the survey instrument, we aim to document the development and testing of the questionnaire, examining the rationale behind the inclusion, format, order and wording of the questions. Reference Bennett, Khangura and Brehaut27–Reference Artino, Phillips, Utrankar, Ta and Durning29 Following this, we discuss methods of data analysis, limitations and considerations for future implementation of the tool in novel settings.

Methods

Questionnaire design

Questionnaire development stemmed from a series of questions used by the Healthy Start to Life Adolescent Education Programme (HSLEAP) at the University of Auckland’s Liggins Institute to assess pre- and post-intervention understanding of DOHaD concepts in school-aged adolescents and their parents. This science learning programme supported 11- to 14-year-olds to explore evidence of potential impacts of early-life environmental exposures on health throughout the life course. Changes in DOHaD awareness by students and their families was observed, often sustained for at least 12-months. Reference Bay, Mora, Sloboda, Morton, Vickers and Gluckman19,Reference Bay, Vickers, Mora, Sloboda and Morton30 Meanwhile, in Japan, Endo and Oyamada had adapted a questionnaire developed by Gage et al. Reference Gage, Raats and Williams17 to explore DOHaD awareness in 18- to 22-year-old Japanese university students. Reference Endo, Sato, Musashi and Oyamada31 A collaboration initiated in 2014 between Japanese and NZ researchers Reference Kawai and Hata32 drew Bay and Oyamada to combine insights from the use of these tools, establishing a core set of questions to facilitate consistent and reliable assessment of DOHaD awareness amongst public and professional populations. Reference Oyamada, Lim, Dixon, Wall and Bay20,Reference Bay, Dixon, Morgan, Wall and Oyamada33,Reference Oyamada, Morgan, Dixon, Wall, Lim and Bay34 Basing the survey protocol on a previous study measuring awareness and knowledge of stroke in adult NZers, Reference Bay, Spiroski, Fogg-Rogers, McCann, Faull and Barber35 the questionnaire could be self-administered online or on paper or conducted by an interviewer.

Three major considerations shaped the survey design. Firstly, questioning should be predominantly qualitative to avoid prompting the respondent with pre-determined choices. Reference Artino, Phillips, Utrankar, Ta and Durning29,Reference Bowling36 However, a quantitative component was necessary for comparing findings across multiple cohorts. Using open questions designed to elicit responses that could be easily and reliably coded either by the data collector or via a post-interview coding process satisfied both criteria. Reference Bowling36,Reference Thwaites Bee and Murdoch-Eaton37 Secondly, the questionnaire must adapt to a variety of settings and stakeholders with varying levels of education and language proficiency. This was achieved by identifying a core group of questions (Table 1), which could be augmented to suit the context. The third consideration emphasised simplicity, to support both face-to-face delivery of the questionnaire and readability for self-administering participants. Reference Bourque and Fielder38

Table 1. Public understanding of DOHaD questionnaire – core questions

* National Certificate of Educational Achievement; NCEA levels 1–3 are typically obtained during the final three years of high school.

Pilot groups evaluated the wording of the questions for ease of delivery and accurate comparison between cohorts. Reference Rickards, Magee and Artino39 To reduce non-completion due to respondent fatigue the questionnaire was designed to take only 5–10 minutes, context-dependent. Reference Bourque and Fielder38 This brevity also supports translation for use in different cultural settings – to date, the PUD questionnaire has undergone translation into Japanese, Tongan and te reo Māori (the Māori language).

Consultation and testing

The questions built on those of the HSLEAP project, developed via a process of expert review, pilot and content validity testing. Reference Bay, Mora, Sloboda, Morton, Vickers and Gluckman19,Reference Artino, La Rochelle, Dezee and Gehlbach28,Reference Bay, Vickers, Mora, Sloboda and Morton30 Together with a new series of questions exploring perceptions of NCDs and prior exposure to DOHaD concepts, these were reviewed again, this time by a different panel of DOHaD experts who confirmed the validity of the questions in relation to their particular field of expertise. Reference Rickards, Magee and Artino39,Reference Gehlbach and Brinkworth40 This group included internationally recognised DOHaD researchers specialising in fields spanning evolutionary biology, epigenetics and developmental physiology, cohort studies, public health and translation of science to policy. Repeat testing with a pilot group as well as focus groups checked the perceived meaning of the questions by lay members of the public, teachers, and university students. Reference Bowling36,Reference Rickards, Magee and Artino39–Reference Converse and Presser41

Survey questions

The core survey comprises three sections. This is referred to as the “core” of the questionnaire, as additional questions may be added depending on the goals of a particular project. Part A focuses on the respondent’s familiarity with NCD terminology, how NCDs develop, and their ideas about potential risk factors. Part B explores DOHaD-specific knowledge using Likert scale questions to determine awareness of early-life environmental impacts on adult health. Familiarity with commonly used DOHaD terminology is also assessed. Part C records demographic data to ensure earlier responses can be evaluated even if the respondent declines to provide personal information, preventing response fatigue from affecting priority questions. Reference Bourque and Fielder38,Reference Converse and Presser41 The format of the core questions is outlined in Table 1, along with a brief rationale for each question’s inclusion in the survey. In this analysis, each of the questions was examined individually and in the context of the wider questionnaire to evaluate how the format, position and wording of each question contributes to the survey’s purpose of assessing the respondent’s awareness of NCD and DOHaD concepts. Reference Rickards, Magee and Artino39

Data analysis

While the questionnaire used for each of the use cases (described in Table 2) was nearly identical, decisions regarding data analysis methods were specific to the aims of each project. In each case, a codebook was used to support coding and analysis of qualitative responses. Researchers wishing to adapt the questionnaire for their own context are advised to likewise develop a codebook to suit their study objectives. This article briefly discusses statistical tests used and the rationale behind their implementation. Given that the current focus is the survey tool itself, we predominantly employ simple descriptive statistics and qualitative observations to highlight key points and demonstrate the breadth of evidence that can be obtained through the tool’s application in various contexts. A full analysis of this data is beyond the scope of this paper; interested parties may consult the Outcome Reporting column in Table 2 for more information regarding the findings from the different cohorts discussed.

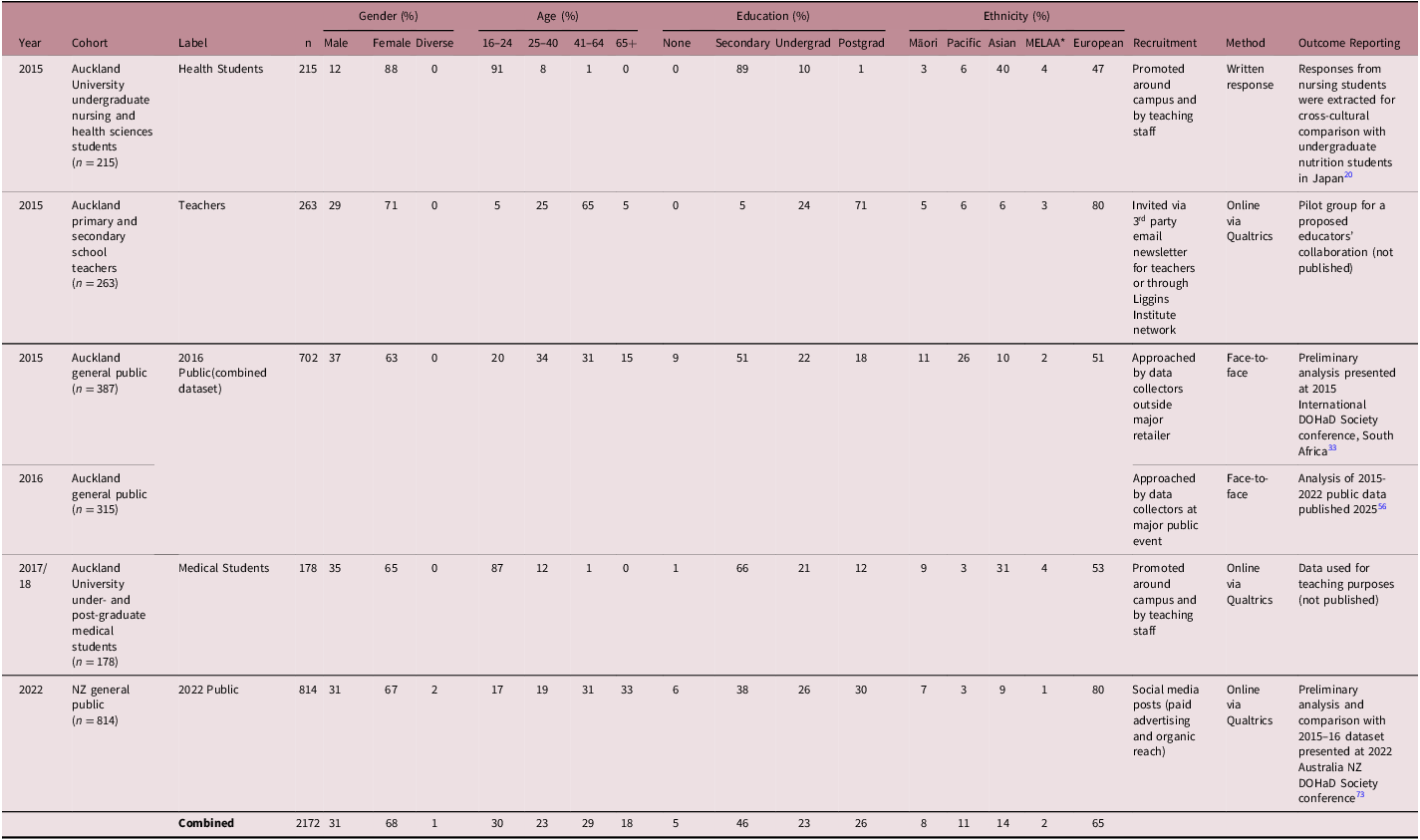

Table 2. Historical use of the public understanding of DOHaD survey tool in NZ

* MELAA = Middle Eastern, Latin American, or African ethnicity.

Ethical considerations

Data collected using the PUD survey tool are confidential for face-to-face or paper responses and completely anonymous for online questionnaires, as no identifying details are recorded. Ethical approval has been arranged according to the location of the survey. In NZ, authorisation in a range of specific settings has been granted by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC; refs. 013093/16008, 23178).

Results

The PUD survey tool has been implemented in several contexts in NZ, Japan, Tonga, and the Cook Islands. Data collected in New Zealand over the ten years of the tool’s history is presented for the purposes of illustration only. Table 2 provides a brief timeline of use since the tool’s inception in 2014.

The core survey questions as outlined in Table 1 formed the basis of all surveys, with minor changes to the wording or question order depending on context. Additional questions which were occasionally added to meet different project goals do not form part of this analysis.

In settings where subjects undertook a face-to-face interview or self-administered the questionnaire in a classroom context, completion rate was 100%. For the online survey in 2022, 772 (95%) of the 814 valid responses were complete. (Following elimination of duplicates, responses were considered valid if the subject answered more than one question.) The mix of open-ended and Likert scale questions was chosen partly to reduce the potential for respondent fatigue. Reference Bowling36

Q1: Have you heard of non-communicable diseases (NCDs)?

Beginning the questionnaire with a yes/no question has the dual advantage of being simple to ask and to answer. Reference Rowley42 Besides providing context for the questions to follow, the aim is to determine how familiar non-scientific populations are with this terminology, given its common use amongst scientists, health researchers and global organisations. 43 In NZ, the Ministry of Health favours the use of “long-term conditions” (LTCs) in public communications, noting that this term is inclusive of some infectious diseases such as hepatitis. Reference Millar and Richards44 Using terminology preferred and understood by the target population can significantly reduce barriers to effective health communication, making this an important consideration. Reference Grene, Cleary and Marcus-Quinn45

The dichotomous response to this question forms a basis for conditional inclusion of Q2 and Q3, as there is little point in querying respondents further regarding a term with which they are unfamiliar. In the case of the medical students, a decision was made to omit Q2. However, despite the anticipated affirmative response to Q1 (Figure 1a), this question was still considered valuable as a low-stakes opener to the survey. Reference Rowley42

Figure 1. (a) Knowledge of non-communicable diseases (note, Q2 not requested of medical students); (b) Characteristics of NCDs – responses combined from all cohorts (except medical students), n = 1355; (c) Correctly identified NCDs – sum of responses from all cohorts, n = 1533; (d) Participant familiarity with one or both of the terms “First 1000 Days” or “Developmental origins of health and disease”; (e) Origin of participant familiarity with terminology.

Q2: Can you tell me what a non-communicable disease is?

Respondents who answer “Yes” to Q1 are invited to clarify their understanding. While Q1 measures familiarity with the term, Q2 assesses understanding of its meaning. This is the first open-ended question and acts as a cross-check for the response to Q1. Reference Singer and Couper46 This question was originally phrased as, What is a non-communicable disease? However the wording was altered to flow more naturally in face-to-face interviews, and this change was adopted for online use as well. The phrasing Can you tell me what a non-communicable disease is? is sometimes interpreted by participants as a request for examples, but this was preferred to describe the characteristics of non-communicable diseases as being easier to say and understand, especially if language proficiency is a potential barrier.

Typical responses were variations of “a disease that is not passed from person to person.” One of the more common incorrect responses was that NCDs are diseases that are not necessary to report to health authorities, indicating that respondents may be confusing the terms “communicable” and “notifiable.” Responses are checked against three distinguishing characteristics of NCDs to determine whether the participant understands that NCDs (a) have a chronic or long-term component, (b) develop slowly over time, and (c) can’t be caught from another person 4 (Figure 1b). Responses may also be evaluated to determine whether they contain (a) all correct knowledge, (b) some or all incorrect knowledge, (c) no answer, or (d) examples only with no description of NCD characteristics. A response is deemed correct if it includes any of the three core characteristics of NCDs, with no accompanying inaccuracies. Figure 1a shows the proportion of each group demonstrating Correct knowledge. As this represents a subset of those answering Q1 affirmatively, both values may be displayed on the same chart.

Q3. Can you give some examples of non-communicable diseases?

As with Q2, Q3 was only asked to those respondents who answered Yes to Q1. An alternate wording for this question was presented to the medical students: Please list as many examples of non-communicable diseases as you can think of.

The open-ended responses are coded by tallying correct and incorrect examples given, determining whether each participant displayed correct knowledge or incorrect knowledge. The most common correct answers given were cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and cancer by a substantial margin, as shown in Figure 1c. Respondents who answered Q2 incorrectly typically proposed examples such as HIV/AIDS or flu, and later COVID-19. Of those who correctly characterised NCDs as non-contagious in Q2 but supplied incorrect examples in Q3, the most common wrong answers were either injuries or infections that are not transmitted by personal contact such as malaria or tetanus, highlighting a lack of clarity around the term “non-communicable.”

Q4: Can you tell me what might increase your chance of developing overweight or obesity?

The open-ended nature of this question allows both qualitative and quantitative analysis, while permitting respondents to provide as much detail as they choose. The original wording for Q4 – What are some of the risk factors for developing overweight or obesity? – was changed due to concerns over participant familiarity with the term “risk factors”; however, the revised wording is not without its problems. The awkwardness of the phrasing has been noted (often in lieu of answering the question) by multiple participants unfamiliar with the use of “overweight” as a noun. In addition, “what might increase your chance” prompts some to answer according to their personal situation rather than that of a hypothetical third person. A proposed change to this question of Can you give some examples of things that might cause a person to gain excess body weight over their lifetime? will be tested in future surveys.

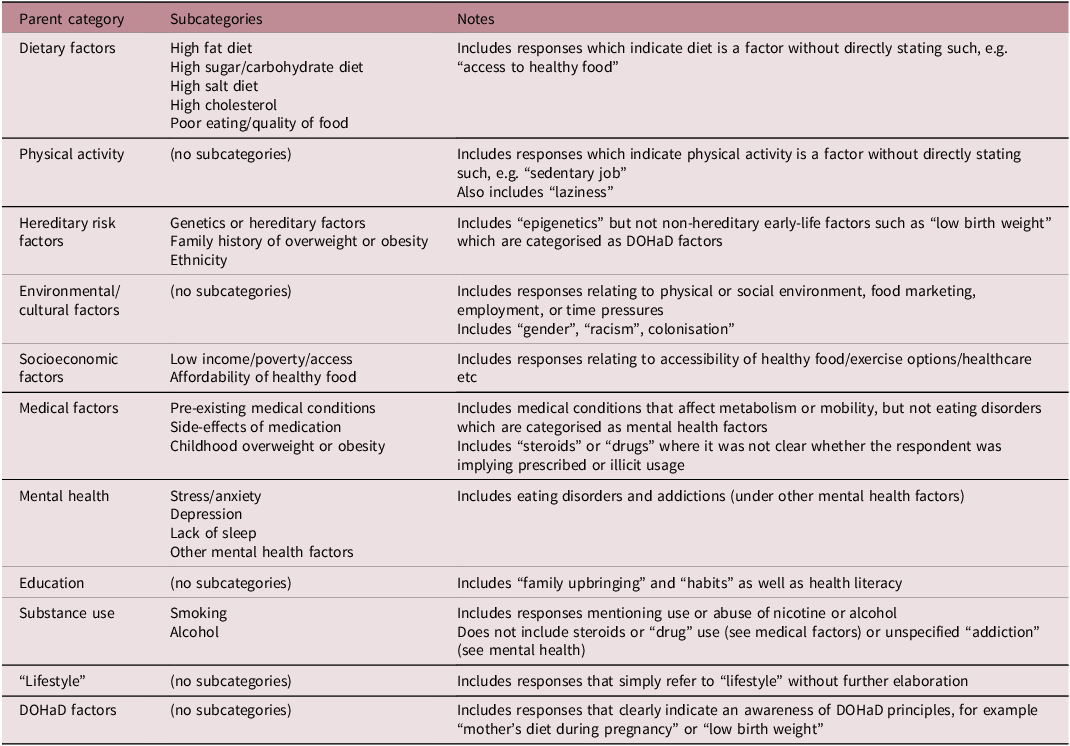

Responses are coded and then grouped into several parent categories (Table 3). Each response may fit multiple categories; for example, “surrounded by cheap takeaway food” would be categorised under Poor eating/quality of food, Affordability of healthy food and Environmental/cultural factors.

Table 3. Coding categories for Q4 responses

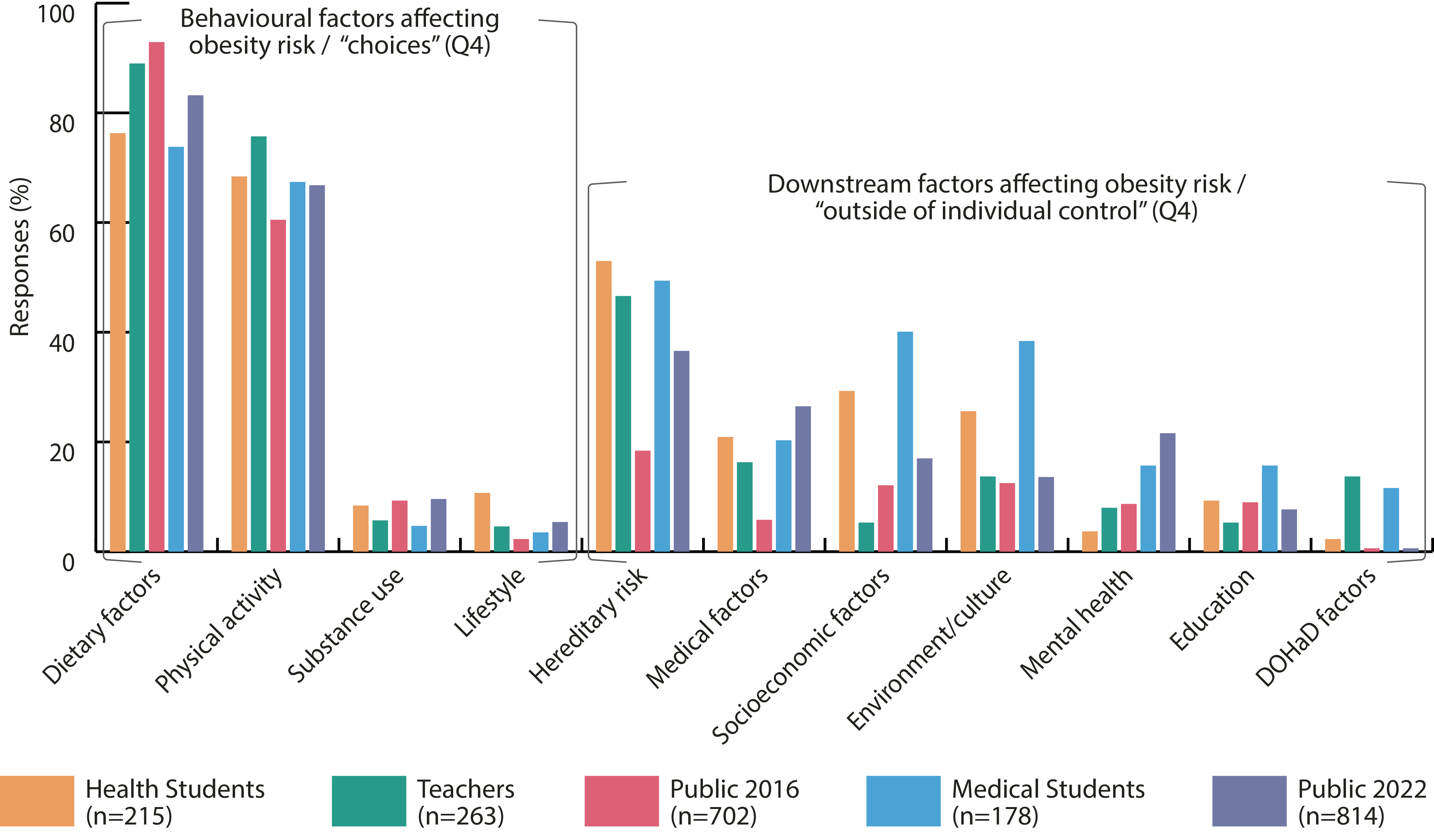

Following categorisation, it is possible to see whether the participants considered factors beyond individual behaviours as contributing to excess weight gain (Figure 2). The wide range of responses may be categorised in terms of upstream risk factors such as genetics, ethnicity, environment, low income or poverty, while some participants simply respond with the word “lifestyle.” Due to its open-ended format, this question provides valuable insight into participants’ perspectives regarding NCD risk factors and causality. To avoid prompting the subject it is necessary that Q4 be included prior to any questions relating to DOHaD concepts.

Figure 2. Factors identified as contributors to obesity risk.

Q5: Likert scale series

The Likert scale questions form the central component of the PUD questionnaire and allow for quantitative comparison of DOHaD awareness within and between groups. Reference Bowling36 The order of the Q5 statements is important, as the concepts presented progress from simple (the food we eat affects our health and wellbeing) through to complex (the food a mother eats during pregnancy may affect the health of the baby throughout adulthood), highlighting, for the majority of subjects, an increase in uncertainty corresponding with a decrease in agreement relative to the complexity of the statement. Reference Rowley42 The ordering of the statements also reduces any bias that could result from viewing the whole statement group and distributing responses accordingly. Reference Converse and Presser41,Reference Rowley42

Participants could agree, disagree, or indicate don’t know for each statement in Q5. Additional options differed for each cohort as the survey tool was refined over time, with strongly agree included for the health students and the 2022 public. For the teachers and medical students, this series was divided into two parts: after completing questions 5a–5l, those who selected agree for any of the questions were presented with the same set of phrases again, this time asking, “To what extent do you think this affects health?” Options given were Not at all, Slightly, Moderately, Extremely and I don’t know. The 2016 public group were also asked this in response to any individual reply of Agree, rather than in a block at the end. For simplicity, in this article we have treated a follow-up response of Extremely as equivalent to Strongly agree. However, it should be noted that these are not equivalent. Disagree/Agree/Strongly agree evaluates the strength of participant agreement with the statement, rather than the perceived significance for health. The choice of format and options provided in a particular setting will depend on the context and aims of the research.

While it cannot be assumed that the intervals between the different points on the Likert scale are equal, the Strongly agree, Agree and Disagree options allow for a relative ordering of responses and, as such, can be used to establish the existence and direction of a trend across multiple questions, as illustrated in Figure 3d and 3e. Reference Boone and Boone47,Reference Sullivan and Artino48 Provision of an I don’t know option means the data as a whole cannot be treated as ordinal, and therefore calculation of Cronbach’s alpha or other quantitative methods of determining reliability are not applicable; however, an uncertainty trend between questions may still be usefully explored. Common methods for handling Likert data disregard the “don’t know” response or treat it as equivalent to a non-response. Reference Converse and Presser41,Reference De Leeuw, Hox and Boevé49 However, as the goal of the survey tool is to assess participant knowledge, the proportion of participants who selected the “don’t know” option provides valuable insight into their inability and/or reluctance to endorse a more definitive answer. Reference Coombs and Coombs50–Reference Turner and Michael52

Figure 3. (a) Perceived importance of maternal vs. paternal pre-conception health for the health of the fetus – combined responses from all cohorts; (b) Perceived long-term effects of maternal diet vs. prenatal tobacco exposure – combined responses from all cohorts; (c) Perceived impact of maternal diet on lifelong health of the child – combined responses from all cohorts (the medical students were not asked Q5g). “Total agreement” combines “Strongly agree” and “Agree” responses; (d) Perceived impact of maternal diet on lifelong health of the child – combined responses from all cohorts (the medical students were not asked Q5g). “Total agreement” combines “Strongly agree” and “Agree” responses; (e) Perceived impact of maternal diet on lifelong health of the child – combined “Strongly agree” and “Agree” responses from all cohorts (the medical students were not asked Q5g).

Q5a: The food we eat affects our health and Wellbeing

This statement gauges respondents’ views on the link between diet and health and serves as a reference for other Q5 responses. As the Likert question with the simplest wording, it also serves to gently introduce the subject to the available Likert options. It is anticipated that nearly all respondents will agree or strongly agree, and this was found in the example populations, with 98%–100% agreement in four out of five cohorts. The exception was the health students, who were presented with a slightly different version of this question: An individual’s diet affects their risk for developing NCDs, to which 95% agreed.

Q5b & c: A mother’s health BEFORE she becomes pregnant/A father’s health BEFORE his partner becomes pregnant may affect the health of the baby (fetus) DURING the pregnancy

Evaluated together, this pair of statements reveals whether the pre-conception health of the mother and the father is viewed as being of equal or differing importance for the development of the child. Typically, more participants have agreed or strongly agreed with Q5b than Q5c (Figure 3a). These statements are particularly valuable for assessing men’s perceptions of the impact of paternal pre-conception health.

When presented in a written format, the words BEFORE and DURING are capitalised for clarity – this becomes more important as the questionnaire progresses and the Q5 statements increase in complexity. Both “fetus” and “baby” are included in the statement wording to maximise accessibility.

Q5e-h: The food a mother eats DURING pregnancy may affect the health of the baby (fetus) DURING the pregnancy? in the FIRST TWO YEARS of their life/throughout CHILDHOOD/throughout ADULTHOOD

As with Q5b and Q5c, these statements provide the greatest insight when analysed together as a set. Prenatal nutrition is used as a proxy to quantitatively assess subjects’ awareness of the ongoing contribution of the developmental environment to offspring health. Responses typically exhibit a trend of decreasing agreement corresponding to the proposed duration of health effects, as shown in Figure 3c, 3d, 3e.

Q5i & j: The food that the CHILD is fed during the first 2 years of life may affect their health throughout CHILDHOOD/throughout ADULTHOOD

These statements explore participants’ awareness of the ongoing importance of the postnatal feeding period including breastfeeding and introduction of solids. They can be treated as a pair and responses analysed similarly to Q5b and Q5c. These two statements are sometimes omitted to reduce the questionnaire length.

Q5k & l: A mother’s use of or exposure to tobacco smoke DURING pregnancy may affect the health of the baby (fetus) DURING the pregnancy/the child throughout their lifetime

These statements explore whether respondents view a non-nutritive factor such as maternal tobacco exposure as having similarly long-lasting health effects compared with maternal diet. The expert panel determined tobacco use in particular to be a suitable comparator as public health messaging around its impact on fetal development was widespread at the time. Reference Gendall, Hoek, Maubach and Edwards53,Reference Trappitt54 This proved accurate, as 65% of participants strongly agreed that tobacco exposure may affect a child’s health as an adult, outweighing both Strongly agree AND Agree responses regarding prenatal nutrition, as shown in Figure 3b.

Q6: Have you ever heard either of the terms “First 1000 Days” or “Developmental Origins of Health and Disease”?

Subjects indicate their familiarity with either of two phrases linked with the concept of early-life environmental influence on lifelong NCD risk. Positioning of this question after the Q5 Likert scale statements ensures participants who are familiar with one or both of the terms are not primed to respond to Q5 accordingly, giving a clearer picture of their understanding of the terms prior to their being explicitly mentioned. Responses are coded together into one of four categories: Heard of neither; Heard of “First 1000 Days”; Heard of DOHaD; Heard of both. Responses can be combined for both phrases (Figure 1d) or recorded separately for each of the two phrases, providing a more nuanced insight into the relative success of each branding or communication campaign.

In a written or online questionnaire Q6 is presented as a multiple-choice question; however, in face-to-face settings subjects often volunteer more than a yes/no answer for each term. We therefore attempted to capture this qualitative response in a more structured way by introducing a follow-up question to the online survey in 2022: In your understanding, what do people mean when they talk about [whichever term they had heard]? Criteria for coding are understanding that (a) the early-life period begins prior to pregnancy; (b) the term refers to early-life environmental factors; and (c) adult health can be affected. These criteria were based on those defined by Lynch et al. in their exploration of epigenetic knowledge in an Australian population. Reference Lynch, Lewis, Macciocca and Craig21

Q7: If yes, where have you heard these terms?

To complete Part B of the questionnaire, participants who answered Q6 affirmatively are asked to describe where they heard the terms. The open-ended responses are coded into nine categories: professional training or work; traditional media (including TV, books, newspapers); public lecture or health promotion event/resource; participation in a research study; family and friends; health professional; online media (including videos, podcasts); general knowledge; or unsure (Figure 1e).

Q8-12: Demographic questions

In Part C, participants are asked about their gender, age, occupation, educational qualifications, and ethnicity. Demographic information can be reviewed after each session to support purposive sampling of future participants if a representative sample of the target population is required.

Demographics of the demonstration cohorts are provided in Table 2; however, as the data has not been analysed for statistical significance, it will not be possible to make inferences about any other population based on the reported results.

Discussion

Many research translation-based interventions focus on teaching or exposure to core concepts associated with DOHaD theory, collecting and analysing data about behaviour or policy change, and evaluating outcomes based on external markers. However, what was the participants’ prior knowledge? Did they already have the knowledge, and the intervention provided additional impetus for change? Could a different approach have led to more effective or lasting changes? By collecting baseline data on awareness of DOHaD principles, the PUD survey tool provides a useful instrument to identify knowledge gaps and tailor interventions to better address participant motivation – the WHY behind the desired behaviour or policy change. Reference Hildreth, Vickers, Buklijas and Bay15,Reference Michie, van Stralen and West55

The questions are designed to be adaptable to a range of contexts and delivery methods. Having implemented the survey in both face-to-face and online formats, with audiences ranging from medical students to the general public, we present some key considerations for effective use of the tool.

Sampling and recruitment considerations

A range of sampling strategies was used over the ten-year period, in both academic and public settings. Purposive sampling of face-to-face subjects was useful where the intention was to recruit a sample representative of the wider population. Online recruitment via social media advertising was significantly cheaper and less time-consuming; however, this introduced a strong self-selection bias, and reaching younger and more diverse audiences via this method proved challenging. Reference Hildreth and Bay56

Self-administered questionnaires yielded richer qualitative data than in-person interviews as participants, perhaps due to the asynchronous nature of the online setting, tended to provide more detailed responses. In face-to-face interviews, answer sheets were pre-printed with common responses, based on observations from pre-testing of the questionnaire – however this was solely for ease of recording and was never shown to the participant. Answers not aligning with pre-printed responses were recorded verbatim by the interviewer. Reference Bowling36,Reference Singer and Couper46 This method preserves qualitative descriptions for inductive analysis, supporting and illustrating quantitative findings. Although the deductive approach of “coding-as-you-go” ensures face-to-face interviews run smoothly, it complicates re-coding when new patterns or themes emerge. Reference Bowling36

In each of the use cases described in Table 2, the questionnaire was administered by researchers at the University of Auckland’s Liggins Institute, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, or School of Nursing. Aside from the public cohorts, subjects typically had an existing connection with the university, either as students or as educators undergoing professional training. The Liggins Institute also offers public lectures on early-life health; therefore, higher levels of health literacy and DOHaD awareness were expected amongst these groups (as is evident in Figure 1a). Factors affecting differences in familiarity with survey concepts should be accounted for if analysis involves comparison between populations.

Data analysis considerations

Coding of responses for most questions is straightforward, and chi-square testing can be performed to confirm the significance of any differences observed. However, Q2 and Q3 both presented coding challenges, as an unambiguous definition for the term “non-communicable disease” proved both elusive and contentious. Reference Ackland, Choi and Puska57,Reference Unwin, Epping Jordan and Bonita58 The World Health Organization and the NCD Alliance describe NCDs as chronic conditions that are not transmissible from person to person, 4,5 which leaves open the question of whether the term encompasses hereditary conditions and genetic or congenital disorders, as well as injuries or infections spread by non-human vectors which could result in a long-term illness. Nutritional deficiencies and neuropsychiatric conditions such as autism or schizophrenia are also inconsistently classified. The development of a codebook for responses to Q3 underwent multiple iterations before it was ultimately decided to code as Correct knowledge any examples for which consensus had not been reached, as it could not reasonably be expected that the ability of the participants to accurately define the term should exceed that of the research team. As our research is primarily concerned with highly prevalent NCDs and their association with environmental exposures, awareness of less well-known conditions was not a key focus of analysis.

Coding of Q3 (Can you give some examples of non-communicable diseases?) becomes more complicated in relation to the length of the response, as participants who took the time to answer in more detail also increased the likelihood of their response being coded Incorrect. For example, a response of “cancer” or “different types of cancer” would be coded as correct knowledge, whereas “all cancers” is incorrect as while proportionally small, some cancers are causes by persistent infections, such as cervical cancer. Reference Bosch, Lorincz, Muñoz, Meijer and Shah59 Less verbose answers in general may be attributed to the public setting or face-to-face interview format, which could influence participant selection and their willingness to provide detailed responses.

Statistical comparison of participant responses across multiple Likert scale statements (e.g., Q5b and Q5c, Q5h and Q5l, or Q5e-h, Figure 3) also proved challenging. Many standard statistical tests are unsuitable for this, as samples are required to be independent. Responses may be compared within the same cohort using odds ratios or tests of marginal homogeneity such as McNemar’s test. For the same reason, establishing the statistical significance of the trends clearly evident in Figure 3c using the Kruskal–Wallis or Jonckheere-Terpstra methods of rank correlation is also not possible. A test of marginal homogeneity can determine whether the distribution of responses differs significantly across the four statements, while simple linear regression evaluates the trends produced and enables a visual comparison between cohorts (Figure 3d, 3e). A complete example of these statistical methods is demonstrated in our full analysis of the 2015–16 and 2021–22 public cohorts. Reference Hildreth and Bay56

Awareness and understanding of DOHaD concepts

As illustrated in Figure 1b, although most respondents who recognise the term “non-communicable disease” understand that NCDs are non-transmissible, few mention their chronic nature, and fewer still describe them as conditions that are slow to develop. This is noteworthy from a DOHaD perspective, as even those who recognise the DOHaD terminology in Q6 tend not to emphasise these characteristics.

Of the participants who had previously encountered DOHaD terminology (Q6), preliminary analysis suggests only 5% of those familiar with one or both phrases could fully articulate their meaning, while 32% mentioned none of the three elements foundational to a basic understanding of DOHaD concepts. Familiarity with DOHaD terminology was also not found to correlate with either a develop slowly response for Q2 or a DOHaD factors response for Q4, except in the case of the medical students, where chi-square testing revealed those students who had heard of one or both of the phrases were more likely to identify early-life factors as possible contributors to overweight and obesity in Q4 (p = 0.45). This discovery emphasises the crucial difference between being aware of something and truly comprehending it, highlighting the potential risk in mistaking recognition of DOHaD terminology for an understanding of its significance. Reference Trevethan60

Strengths and limitations of the survey tool

Mixed-methods approach

Open-ended questions enhance the survey tool but pose challenges for consistent coding. Development of a codebook to reflect the aims of each individual project allows open-ended responses to be analysed quantitatively for comparison between cohorts and over time, while retaining the original verbatim responses for maximum flexibility.

Participant interpretation of questions

Although open-ended questions are more likely to result in non-completion when the questionnaire is self-administered, they are valuable for gauging understanding of a concept without introducing bias via a prompt. Reference Schuwirth, van der Vleuten and Donkers61 For Q4 in particular, the absence of prescribed options reveals the extent to which the participant considers peripheral influences on diet and physical activity. However, this may result in participants interpreting the questions differently than intended. For example, they might agree that parental nutrition affects offspring health but explain that this is due to learned dietary habits and behaviours, which does not demonstrate knowledge of epigenetic factors. Therefore, agreement with Q5 statements should be seen as a maximum measure of DOHaD awareness, likely overestimating true understanding. In future questionnaire development, cognitive interviewing techniques or “think-aloud“ testing could be employed during pilot testing to highlight potential mismatches between question intent and participant interpretation and improve validity of responses. Reference Gehlbach and Brinkworth40,Reference Drennan62,Reference Suchman, Jordan and Tanur63

Non-nutritional early-life exposures

A key limitation of the tool is the focus on preconception health and prenatal nutrition as early-life indicators of NCD risk. This resulted in part from the early use of the PUD survey with nutrition students but was primarily a decision made for the purposes of questionnaire brevity. In the decade since the tool was developed, evidence implicating a wide range of early-life environmental influences as potential NCD risk factors has grown increasingly robust. Reference Buklijas and Al-Gailani64,Reference Penkler65 To quantify DOHaD awareness, the questionnaire inherently simplifies an extremely complex topic. However, exploring additional aspects of DOHaD knowledge in future surveys would enrich the evidence base for knowledge translation interventions.

Generalisability and validity across contexts

The PUD questionnaire is a valuable instrument for measuring awareness of DOHaD concepts and enables a quantitative foundation for comparison against baseline data within the same population. Additional questions may be added depending on the goals of a particular project. In general, inclusion of all the core questions is recommended, as they provide important cross-checks to help ensure validity of responses. By keeping questions simple, concise, and consistent, the survey tool can be used in various contexts. For tracking changes over time, recruitment and data collection methods should remain consistent where practical. Qualitative analysis of open-ended responses and comparison of individual answers across questions allows deeper exploration of subjects’ understanding of DOHaD science beyond stated awareness.

Conclusion

The implementation of the Public Understanding of DOHaD survey tool in various NZ and international settings illustrates its adaptability for different audiences as well as the tool’s evolution over time. The rationale behind the format and phrasing of the core questions has been described in order to assist with future adaptation and translation of the questionnaire for deployment in novel contexts. The authors anticipate this will contribute to its broader application amongst researchers and public health professionals seeking to better understand DOHaD awareness in their communities.

Data availability statement

Access to datasets presented in this article will be considered upon written request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the following people who contributed to the development and evolution of the Public Understanding of DOHaD survey tool: Robyn Dixon, Sarah Morgan, Clare Wall, Anecita Lim, Julie Brown and Lily Yang.

Author contributions

JLB and MO designed the Public Understanding of DOHaD Survey and led the prior work enabling the data sets that were combined in this study; JRH collated the combined data set used in this study; JRH and JLB analysed the combined dataset; JRH prepared the original draft, all authors contributed to review and editing; all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Liggins Institute’s Faculty Research Development Fund (3706937) at the University of Auckland in New Zealand and by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan (23617021). Jillian Hildreth is supported by a University of Auckland PhD Scholarship.

Competing interests

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical standard

Ethical approval for use of the survey tool has been arranged according to the location of the survey. In New Zealand approval for use in a range of specific settings has been granted by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC; refs. 013093/16008, 23178). All participants grant informed consent (written or oral depending on the setting) before engaging with the survey. All researchers or assistants working with the data are either named as collaborators in accordance with the ethics process or are required to sign a confidentiality agreement.