Introduction

To address the large-scale socio-economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Union (EU)’s main policy response consisted in Next Generation EU (NGEU), a €750 billion programme integrated into the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), with the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) as its core financial assistance instrument. The RRF provides financial support to member state governments in the form of grants and loans to carry out structural reforms and public investments. The implementation of the RRF, which follows the adoption of the RRF regulation in February 2021, is itself a lengthy process which requires a number of steps to be completed: first, EU member states need to elaborate and submit National Recovery and Resilience Plans (NRRPs) to the European Commission, setting out the reform and investment projects they intend to pursue with EU funds; second, the European Commission then has to evaluate and approve those plans; third, EU member states are expected to carry through the reform and investment programmes outlined in their NRRPs; and finally, the European Commission then has the role to monitor over member states’ achievement of the agreed milestones and targets as per their NRRPs. This process departs from usual implementation arrangements where the implementation of EU policies is left to the member states, which then have a degree of freedom to choose the means with which to achieve the substance of the agreed policy objectives. By contrast, the RRF provides for a new form of implementation involving a coordinative effort between the European Commission and national authorities in what has been termed as a “direct management regime” (Lippi and Terlizzi Reference Lippi and Terlizzi2024).

The academic literature on the governance of the RRF is burgeoning (Buti and Fabbrini Reference Buti and Fabbrini2023; Capati Reference Capati2023; Fasone and Lupo Reference Fasone and Lupo2024; Fernández-Pasarín and Lanaia Reference Fernández-Pasarín and Lanaia2024; Zeitlin et al. Reference Zeitlin, Bokhorst and Eihmanis2024). Scholarly work has explored emerging patterns in the formulation of NRRPs, including the role of the Commission (Bokhorst and Corti Reference Bokhorst and Corti2023), national governments and parliaments (Bekker Reference Bekker2021), political parties (Oellerich and Simons Reference Oellerich and Simons2023) and other stakeholders (Munta et al. Reference Munta, Pircher and Bekker2023). In particular, the recent literature on coordinative Europeanisation (Ladi and Wolff Reference Ladi and Wolff2021; Ladi and Polverari Reference Ladi and Polverari2024) has investigated the interactions between the European Commission and executive actors (both political and technical) at the national level. In this respect, it has been argued that, starting from the outbreak of COVID-19, relations between actors at the EU and the national level have witnessed greater degrees of coordination, mutual learning and national ownership due to increased interdependence and the urgent need for action. As a result of such coordinative Europeanisation, in the implementation of the RRF, the Commission and national authorities “have been careful not to politicise the NRRP, downplaying latent conflicts and stressing the fruitful dialogue and ongoing cooperation” (Bressanelli and Natali Reference Bressanelli and Natali2024: 13). However, studies adopting this approach have arguably not taken sufficiently into account how aspects related to the legitimacy of the implementation of the RRF—or, as the case may be, the lack thereof—have the potential to politicise the adoption of NRRPs and even favour the emergence of political dissensus—i.e. a form of political contestation driven by different types of actors, operating at different levels, and with different goals.

Against this background, the present article seeks to contribute to and challenge the literature on coordinative Europeanisation in three respects. First, building on an earlier theoretical strand on the Europeanisation of the core executive (Bulmer and Burch Reference Bulmer and Burch2009; Laffan Reference Laffan, Graziano and Vink2007), the article shows that the implementation of the RRF tends to centralise powers in national executives and their technical-administrative structures to the detriment of national legislatures. This gives rise to a “legitimacy disequilibrium” in the implementation of the RRF characterised by a strong technocratic legitimacy and a weak democratic legitimacy. Second, drawing on post-functionalism theorising (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009), we take issue with the coordinative Europeanisation literature and argue that the implementation of EU policies (in general), and the implementation of the RRF (in particular), is not shielded from dynamics of politicisation. On the contrary, the legitimacy disequilibrium resulting from the implementation of the RRF is prone to being politicised by national party actors, thus assuming salience in national public debate. Finally, integrating insights from the literature on EU agenda responsiveness (Alexandrova et al Reference Alexandrova, Rasmussen and Toshkov2016; Koop et al. Reference Koop, Reh and Bressanelli2022), the article illustrates how the national politicisation of the NRRPs has the potential to give rise to political dissensus, involving different types of actors (EU institutions, member state governments and national parties), at different levels (EU and national), and with different aims.

The article tests the relationship between legitimacy and political dissensus in the implementation of the RRF against the Italian case. Italy can be considered as a critical test case in this regard. As the country who suffered the most from the economic consequences of the pandemic relative to GDP, it received the lion’s share of the facility’s resources. For this reason, the Italian NRPP is one of the most ambitious across the board, including more than 150 milestones and targets (Moschella and Verzichelli Reference Moschella and Verzichelli2021). In addition, Italy has traditionally faced longstanding structural weaknesses preventing the efficient management of EU resources due to bureaucratic inertia, a lack of administrative capacity and distinctive political instability, which in the past hampered the country’s ability to absorb EU funds (Domorenok and Guardiancich Reference Domorenok and Guardiancich2022). As for political instability, in the period under investigation, Italy witnessed two government crises and three very different coalition governments (one centre-left, one “technocratic” or “national unity” and one right-wing cabinet), each of which dealt with distinct stages in the policy process, from the initial design of the NRRP (Conte II government), via its redefinition and submission to the Commission (Draghi government) and eventually to its execution (Meloni government). All these factors combine to make Italy the most likely site of any potential dissensus about the implementation of the RRF.

The empirical analysis temporally covers all three Italian cabinets in their dealings with the RRF—the Conte II government, who elaborated the first draft of the NRRP; the Draghi government, who revised the NRRP and submitted it to the Commission for validation; and the Meloni government, responsible for amendments to the NRRP and its implementation. By relying on a triangulation between primary sources (e.g. official documents, media reports and a set of semi-structured elite interviews) and secondary sources (e.g. the relevant academic literature), the article shows that the emergence of a legitimacy disequilibrium in the implementation of the RRF in Italy contributed to the politicisation of the Italian NRRP by national parties. This, in turn, favoured the emergence of political dissensus by giving rise to a political confrontation over the NRRP involving the European Commission (EU level), the Italian government, as well as majority and opposition parties (national level).

The article is structured as follows. “Introduction” section develops a framework of analysis which conceptualises legitimacy in the relations between the EU and national institutions across the democratic, technocratic and procedural forms. It then discusses political dissensus as a multidimensional concept related to legitimacy aspects. “Conceptualising legitimacy and dissensus in the implementation of the RRF” section illustrates the article’s theoretical framework and research hypotheses. “Theoretical framework and research hypotheses” section examines democratic, technocratic and procedural legitimacy in the implementation of the RRF. “Democratic, technocratic and procedural legitimacy in the implementation of the RRF” section examines the legitimacy disequilibrium in Italy’s implementation of the RRF and how that contributed to the politicisation of the Italian NRRP. “The legitimacy disequilibrium and politicisation in the implementation of the RRF: The Italian NRRP” section investigates the emergence of political dissensus in Italy’s implementation of the RRF. The final section summarises the research findings, discusses the article’s contribution and concludes.

Conceptualising legitimacy and dissensus in the implementation of the RRF

The multilevel nature of EU economic policymaking involves the interaction among EU institutions as well as between EU and national institutions (Piattoni Reference Piattoni2009). These two dimensions of EU decision-making have been identified as the “horizontal” and the “vertical” dimension, respectively (Fabbrini Reference Fabbrini2010). The horizontal dimension concerns interactions among institutions at the same level of government, including inter-institutional relations between EU supranational and intergovernmental actors, most notably the European Commission, the European Council, the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers (hereafter, Council), as well as the role of EU-level expert committees in the decision-making process. The vertical dimension involves, instead, interactions between institutions at different levels of government, such as inter-level relations between EU actors and member state institutions, including national governments, national parliaments and independent advisory bodies. The horizontal and the vertical dimensions of legitimacy are de facto “fused” through member state governments, which have a dual role in EU economic governance: both as executives individually responsible for their respective national jurisdictions, and collectively as members of the European Council and the Council (Schramm and Wessels Reference Schramm and Wessels2022). Consistently with our focus on the national implementation of the RRF, this article addresses the vertical dimension of legitimacy, looking at relations between institutions at the EU and the national level.

We thus build on the relevant scholarly literature and identify three different types of legitimacy, namely democratic (or input), technocratic (or output) and procedural (or throughput) legitimacy. Democratic (or input) legitimacy requires that democratically elected representatives sitting in national legislatures determine the broad direction of policy choices and that these have the capacity to hold to account governments and technocratic officials in the decision-making process (Crum Reference Crum2018). This is because at the national level input legitimacy is traditionally associated with the democratic elections of parliaments and their roles in influencing political decisions as well as in controlling governments (Holzhacker Reference Holzhacker2007). Parliaments are generally seen as the institutional intermediaries in a chain of representation that goes from citizens to decision-makers (Strøm Reference Strøm2000). Between elections, parliamentary action and control of the government serves to ensure that the executive responds to voters’ preferences. According to Scharpf (Reference Scharpf1999), democratic legitimacy (or “input legitimacy”) emphasises “government by the people” and is based on the rhetoric of “participation” and “consensus”. Along these lines, “political choices are democratically legitimate if and because they reflect the ‘will of the people’—that is, if they can be derived from the authentic preferences of the members of a community” (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999: 7).

In this light, in addition to the few instances in which citizens can directly influence political decision-making (e.g. referendums, petitions, etc.), it is mainly the involvement of democratically elected representatives that ensures the political accountability and responsiveness of executive office holders to their respective national or European constituencies. Thus, “parliamentary accountability tracks executive authority” as parliaments are the institutional “arena where the exercise of political power is subject to political justification” (Crum Reference Crum2018: 270). This is even more apparent in the EU, where the supranational executive—the European Commission—is also a technical body composed of independent policymakers and where claims of a “democratic deficit” are primarily associated with the inability of the European Parliament to compensate for the downsizing of parliamentary powers at the national level following European integration dynamics (Holzhacker Reference Holzhacker2007; Weiler et al. Reference Weiler, Haltern and Mayer1995). In sum, although parliamentary involvement is only one aspect of democratic legitimacy and does not constitute it in its entirety, it is arguably one of the most relevant ones as there can be little democratic legitimacy without parliamentary control of executive power. The article thus identifies parliamentary involvement as a proxy for democratic legitimacy and operationalises democratic legitimacy through the role played by national parliaments in the policymaking process for the implementation of the RRF.

While democratic legitimacy requires parliamentary involvement in policymaking, technocratic (or “output”) legitimacy describes the way in which executive action can be legitimised through the involvement of technical experts who, through their superior knowledge of technical details in areas which require scientific expertise, are trusted to arrive at the best solution for a given problem (Lobo and MacManus Reference Lobo, MacManus, Bertsou and Caramani2020). This form of legitimacy is associated with political independence, expertise, regulation and de-politicisation (Sánchez-Cuenca Reference Sánchez-Cuenca2017). Notwithstanding the nature of the input provided in the political process, citizens will consider decision-making legitimate if the outcome satisfies or exceeds expectations. In reverse, the legitimacy of decision-making can be expected to suffer if and when the results of public policy are unsatisfactory. As such, technocracy “elevates a knowledge elite that identifies the common good objectively through reason and which relies on competence, neutrality, efficiency and expertise as [its] source of legitimacy” (Van der Veer and Meibauer Reference Van der Veer and Meibauer2024: 4). Thus, technocratic legitimacy privileges expertise and non-majoritarianism.

David Easton (Reference Easton1957), one of the first proponents of the concepts of “input” and “output” legitimacy, suggested that the latter consists in the effectiveness of executive authorities’ decisions and actions (see also Schmidt Reference Schmidt2013), with the implication that governments have access to technical expertise much more than the majoritarian institutions of electoral representation. Building on that, part of the literature has argued that in EU regulatory policymaking, technocrats rather than majoritarian bodies, such as parliaments, should play a key role in order to achieve pareto-optimal outcomes (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2002). While decisions in EU economic governance arguably have both regulatory and distributive implications, it is nevertheless an area in which the need for, and involvement of, technical expertise is undisputed. As a matter of fact, technocratic experts at the service of national governments have significantly shaped the design and evolution of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) (Dyson and Featherstone Reference Dyson and Featherstone1996). As a reflection, scholars adopting an output approach to legitimacy are not so pessimistic about the EU’s inherent deficits as they are more concerned with the EU’s policy effectiveness, which is related to the performance of non-majoritarian institutions, such as the European Commission, as well as their reliance on technical expertise (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2013). On this basis, the article operationalises technocratic legitimacy through member state governments’ reliance on independent expert committees and advisory bodies in the policymaking for the implementation of the RRF.

Democratic and technocratic legitimacy mirrors the notions of “input” and “output” legitimacy that is applicable to the study of EU economic governance. In addition to democratic (input) legitimacy—citizens’ participation in the composition of representative institutions and the latter’s control over executive power—and technocratic (output) legitimacy—the achievement of effective policy outcomes through the reliance on technical expertise by executive officeholders—a further type of legitimacy has been proposed, namely procedural (or “throughput”). Throughput legitimacy “covers what goes on in between the Input and the Output” (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2013: 14). As Schmidt (Reference Schmidt2013) highlights, procedural legitimacy “is process oriented and based on the interactions—institutional and constructive—of all actors engaged in EU governance” (5). It thus “focuses on the quality of the governance processes of the EU” (5), emphasising institutions’ efficacy, accountability, inclusiveness, transparency and openness.

Drawing from the above, EU procedural legitimacy includes the following four basic elements: efficiency of decision-making processes, accountability of actors involved in those processes, transparency of information, and inclusiveness to deliberation and consultation (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2013: 6–8). Though a multifaceted concept, procedural legitimacy is here operationalised through the transparency and publicity of policy measures adopted in the implementation of the RRF. Such aspects of throughput legitimacy are in fact assumed to serve as a relevant analytical proxy for the whole concept.

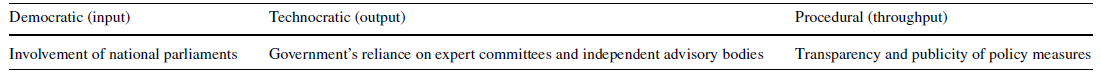

The combination of these three types of legitimacy—democratic, technocratic and procedural—provides us with the grid below (see Table 1). Bringing together various sources of legitimacy entails recognising that there are tensions and potential trade-offs between them—greater reliance on democratic input may jeopardise the weight of technocratic expertise, and vice versa (Bertsou and Caramani Reference Bertsou and Caramani2020). We thus conceptualise “legitimacy disequilibrium” in EU governance as the combination of both strong and weak legitimacy dimensions, most notably the presence of strong technocratic and weak democratic legitimacy.

Table 1 Forms of Legitimacy in the Implementation of the RRF. Source: Authors’ own elaboration

Along the lines of this Special Issue (SI), political dissensus is conceptualised as “the expression of social, political and legal conflicts driven by political, social, legal actors, including state and non-state actors seeking to maintain, to replace or to restructure liberal democracy” or aspects thereof. Contrary to “opposition” and “contestation”, which are unidimensional concepts, dissensus as an analytical tool addresses the expression of claims and counterclaims by exploring the interactions between different kind of actors (e.g. supranational actors, governments and parties), at different levels (e.g. EU, national and local), and with different aims. In its interpretation as multilevel and multi-purpose political conflict related to legitimacy issues, political dissensus has three dimensions to it: the origins (where it stems from), actors (who drives it) and goals (with what aims). Focusing on national government and party actors as well as EU supranational institutions as potential drivers of dissensus, the article discusses the implementation of the RRF in the case of Italy and sheds light on the origins and goals of political dissensus.

Theoretical framework and research hypotheses

Our investigation of the relation between legitimacy issues and the emergence of political dissensus in the implementation of the RRF is theoretically informed by three streams of the literature on EU studies. The literature on the Europeanisation of national executives (Bulmer and Burch Reference Bulmer and Burch2009; Goetz Reference Goetz2000) has traditionally pointed to the empowerment of national governments and their technocratic structures to the detriment of national legislatures in the context of European integration. In this light, the integration process has produced asymmetric effects at the domestic level, favouring a greater involvement of national executives in EU affairs and the concomitant downsizing of national parliaments. This has been particularly true since the integration of so-called "core state powers" with the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, which contributed to the institutionalisation of intergovernmental practices at the EU level to deal with policy areas at the core of national sovereignty (Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2014). Consistently with liberal intergovernmentalist theorising, the strengthening of national executives may reflect the fact that governments are the actors better positioned to identify and aggregate the amalgam of domestic socio-economic preferences that comes to constitute the national interest (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik1993).

The centralisation of powers in the hands of national executives following Europeanisation dynamics is particularly apparent in the phase of implementation of EU policies (Laffan Reference Laffan, Graziano and Vink2007), which requires the member states to give policy substance to supranational regulations or directives. This necessitates a degree of technical expertise, organisational efficiency and administrative capacity that the executive has much more of at its disposal than the legislature, thus favouring the “deparliamentarisation” of EU politics (Fabbrini and Donà Reference Fabbrini and Donà2003: 34). To this effect, the concept of "core executive" (Dunleavy and Rhodes Reference Dunleavy and Rhodes1990) has been advanced by the literature to refer not only to the cabinet and its prime minister, but also to the technical bodies established to coordinate the implementation of EU policies at the national level, including ad hoc expert committees and national civil servants (Dyson and Featherstone Reference Dyson and Featherstone1996). The key role of technocratic experts at the service of member state governments in the implementation of EU policy processes is arguably one of the key drivers of executive primacy and the concurrent weakening of parliaments. Based on the foregoing, we raise the following theoretical expectation on the implementation of the RRF in Italy:

H1

The implementation of the RRF is likely to lead to a legitimacy disequilibrium, characterised by a strong technocratic legitimacy and a weak democratic legitimacy.

Building on the post-functionalist literature (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009), the article identifies politicisation as the channel through which the legitimacy disequilibrium, resulting from the implementation of the RRF, may lead to political dissensus. Politicisation is generally defined in terms of salience, meaning that an issue is politicised “when it is high on the agenda” of political actors (Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2012: 117). If applied to parties, politicisation consists of the emphasis that political parties give to specific policy issues (Budge and Farlie Reference Budge and Farlie1983), including those related to aspects of EU governance. Post-functionalism conceives the relation between politicisation and European integration in terms of a trade-off whereby politicisation ultimately constrains the integration process, increasing the scope for contestation of EU-related issues. That is because European integration has shifted from a context of "permissive consensus", based on depoliticisation and a tacit approval of integration dynamics by national publics, to one of "constraining dissensus", where the nature of EU decision-making processes becomes a matter of domestic political debate and conflict.

In the domestic electoral arena, political parties are the most relevant actors and are able to mobilise voters on issues which they deem relevant or electorally rewarding. In this respect, challenger and Eurosceptic parties on both the left and right of the political spectrum have been the main architects of politicisation dynamics around European integration since the “critical juncture” of the Maastricht Treaty (Kriesi Reference Kriesi2007). While mainstream parties have done everything to de-politicise the integration process, as they have promoted advancements in European integration for a long time, challenger parties have adopted politicisation strategies to reduce their electoral disadvantage vis-à-vis the governing parties. On the one hand, radical left parties have mobilised voters on specific EU policies. In particular, they have targeted the EU’s neoliberal character, considered as a way for the elites to exploit the working class and erode the welfare state. On the other, radical right parties have expressed a form of unconditional opposition to the EU as such, viewed as a form of supranational delegation undermining national identity and member states’ sovereignty (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Popa and Schmitt2019). Overall, however, both radical left and right parties have favoured politicisation by questioning the legitimacy of European integration, be it in terms of what constitutes a legitimate political order, the legitimate scope and degree of supranational authority or the legitimate policy trajectory of the EU (Statham and Trenz Reference Statham and Trenz2015). This leads us to raise the following hypothesis:

H2

The legitimacy disequilibrium resulting from the implementation of the RRF is likely to be politicised by challenger or Eurosceptic parties at the national level

The politicisation of European integration has invariably led to the increased domestic visibility of Europe, bringing with it both opportunities and challenges for EU supranational institutions and especially the European Commission as the “engine of integration” (Thomson and Dumont Reference Thomson and Dumont2022). Politicisation has extended the Commission’s audience from political elites, expert groups and insider networks to national parties and the mass publics (Rauh Reference Rauh2016). It has thus provided the supranational executive with the opportunity to strengthen its legitimacy and reputation before national constituencies by engaging in problem-solving and entrepreneurship practices in the face of internal or external pressures (Bressanelli et al. Reference Bressanelli, Koop and Reh2020). At the same time, as the EU’s technocratic institution par excellence, the Commission has itself attracted fierce criticism from Eurosceptic parties and national audiences for how it steered the integration process in an era of “polycrisis” (Zeitlin et al. Reference Zeitlin, Nicoli and Laffan2019).

A fundamental question thus remains as to whether and under what conditions the European Commission responds to domestic issue salience at the party and electoral levels. The literature on EU agenda responsiveness (Alexandrova et al Reference Alexandrova, Rasmussen and Toshkov2016; Koop et al. Reference Koop, Reh and Bressanelli2022; Rauh Reference Rauh2016) has suggested that the European Commission will act as a policy-seeker targeting EU issues that have been politicised, hence made more salient, by national parties and publics. As Majone (Reference Majone1996) argued, the Commission derives its legitimacy primarily from performance and reputation, which can be assessed against the policy output it contributes to generating.Footnote 1 This is all the more so in a politicised context, because the Commission’s failure to deliver becomes much more visible to national actors, who may in turn blame the supranational executive for poor policy outcomes (Koop et al. Reference Koop, Reh and Bressanelli2022). Domestic politicisation ends up producing bottom-up pressures that need to be addressed by EU-level actors (Bressanelli et al. Reference Bressanelli, Koop and Reh2020). As Moschella shows in the case of central banks, technocratic institutions “respond to the expectations and demands of various audiences (including political and public audiences) based on the challenges these audiences pose to [their] reputation” (2024: 5).

The Commission is thus expected to react to such bottom-up pressures and target those issues that are most salient to national parties and publics, with a view to increasing the chances of domestic delivery, and it is in a privileged position to do so in areas where competences are shared and cooperation is required between the Commission and national authorities, which is the case with the national implementation of EU policies. The implementation of the RRF, in particular, requires EU member states to elaborate and submit NRRPs setting out detailed reforms and investment programmes they intend to carry out in exchange for the requested financial assistance. For its part, the Commission assesses those plans against common and country-specific objectives of post-pandemic recovery and monitors the progressive achievement of so-called milestones and targets. Drawing on the literature on agenda responsiveness, we thus put forward the following research hypothesis:

H3

The European Commission is likely to respond to the politicisation of the NRRPs to ensure delivery by member state governments

We thus expect to find evidence of the European Commission contesting member states’ efforts to deviate from the reform and investment programmes outlined in their NRRPs as agreed upon with the EU.

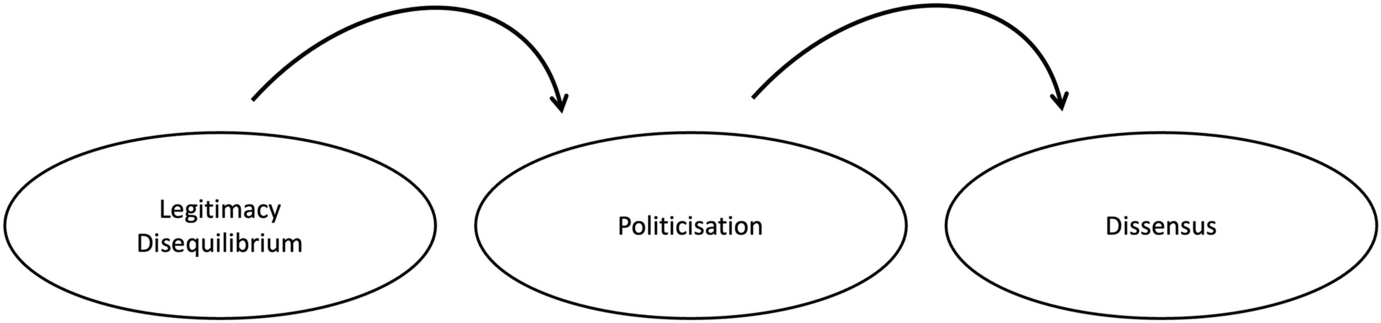

To this effect, the article’s hypothesised mechanism, synthesising the link between legitimacy issues, politicisation and dissensus in the implementation of the RRF, is summarised in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Italian NRRP: from legitimacy disequilibrium to dissensus through politicisation.

Democratic, technocratic and procedural legitimacy in the implementation of the RRF

This section examines democratic, technocratic and procedural legitimacy in the implementation of the RRF with a focus on inter-level relations between EU and national institutions, thus providing an empirical background for testing H1.

Socio-economic policy is one of the key decision-making powers of national parliaments domestically, and the role that national parliaments can play in the formulation of NRRPs has a large impact on the democratic legitimacy of the RRF at the vertical level. In practice, however, the participation of national parliaments in the implementation of the instrument greatly depends on national arrangements and, “given limitations of time and expertise, as well as the electoral incentives facing their members, it seems unrealistic to expect most national parliaments to play a more active part in scrutinising the Semester process” (Verdun and Zeitlin Reference Verdun and Zeitlin2018: 145), and also for what concerns aspects related to the RRF. The RRF regulation indeed does not require national parliaments to be involved in the preparation of the NRRPs and limits itself to providing that member states should compile “a summary of the consultation process, conducted in accordance with the national legal framework, of local and regional authorities, social partners, civil society organisations, youth organisations and other relevant stakeholders, and how the input of the stakeholders is reflected in the recovery and resilience plan” (RRF Regulation 2021: 63).

The role of national parliaments in the decision-making system of the RRF is thus completely neglected and absorbed into the broader concept of “stakeholders” (Dias Pinheiro and Dias Reference Dias Pinheiro and Dias2022). As Van den Brink (2020) puts it, “the proposed governance system of the RRF raises questions of parliamentary involvement and democratic decision-making similar to those that emerged when the European Semester was designed” (27). As a matter of fact, the elaboration of NRRPs witnessed the centralisation of power in the hands of core executives, including the chief executive and its offices, with a very limited involvement of national legislatures and domestic stakeholders (Bokhorst and Corti Reference Bokhorst and Corti2023). This was mainly due to the short time available for the submission of national recovery plans and the high technical expertise needed to formulate detailed and coherent investment and reform programmes. Notwithstanding the markedly supranational character of the RRF, especially when compared to the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) in use during the Eurozone crisis, the marginal involvement of both the European Parliament and of national legislatures in the governance of the RRF is what led the literature to talk of a “limited” or “constrained” supranationalism (Capati Reference Capati2024; Fabbrini and Capati Reference Fabbrini, Capati, Adamski, Amtenbrink and de Haan2023). For these reasons, the democratic legitimacy of the RRF at the vertical level remains highly contested.

In terms of technocratic legitimacy, the sweeping role of the European Commission in the framework of the RRF reflects the technical nature of the instrument, which requires administrative capacity and expertise and makes it elusive to the dynamics of political oversight. The RRF is indeed integrated into the policymaking cycle of the European Semester, the technocratic EU institutional framework par excellence (Crum and Curtin Reference Crum, Curtin and Piattoni2015), to facilitate alignment between the national recovery programmes and broader EU economic policy objectives. At the vertical level, the establishment of the RRF urged member states to provide themselves with an “efficient internal control system” to collect standardised data and prevent irregularities, including fraud and corruption (RRF Regulation 2021: 28). National governments are thus supported in the elaboration of NRRPs by national advisory bodies, expert committees as well as independent monitoring institutions. In particular, governments largely rely on economic data provided by independent bodies, such as the Federal Statistical Office in the case of Germany or the National Institute of Statistics in the case of Italy. In addition, member state governments are also supported by the Recovery and Resilience Task Force (RECOVER). RECOVER was established in August 2020 as part of the Commission’s Secretariat-General, working in close cooperation with DG ECFIN. RECOVER reports directly to the President of the Commission and acts as a bridge between the Commission and the member states in the framework of the RRF. It offers technical support to the member states in the elaboration of their recovery plans, cooperates with them to ensure that the NRRPs comply with the objectives of the green and digital transition as well as deliver on the country-specific recommendations, and helps the Commission evaluate the NRPPs’ fulfilment of the relevant milestones and targets. In this sense, expert committees operating between the EU and the national level may well be part of a de-politicisation strategy in the context of socio-economic policy coordination aimed at ensuring legitimacy through technocracy (Lobo and MacManus Reference Lobo, MacManus, Bertsou and Caramani2020).

Finally, in terms of procedural legitimacy, the transparency of the decision-making process under the RRF is ensured by the timely publication of all NRRPs submitted by the member states, which the Commission relays without delay to the European Parliament and Council. The Commission’s assessment of those plans and the Council implementing decision on the disbursement or suspension of financial assistance are also made public. The Commission’s assessments are open to follow-up, discussion and even contestation from member state governments, including through the exchange of formal letters between Commission officials and national representatives. Moreover, the Recovery and Resilience Scoreboard (RRS) was established in December 2021 as a tool to display the funding allocated to each member state, payment requests by the member states and the related Commission’s assessments and Council’s decisions on submitted NRRPs, as well as progress made by the member states in the implementation of NRRPs with respect to both the common and the country-specific objectives of the RRF. The RRS is publicly available for consultation and is updated by the European Commission at least twice a year.

Overall, the implementation of the RRF is characterised by a strong technocratic and procedural legitimacy and by very weak democratic legitimacy. In particular, the limited involvement of national parliaments in the formulation of NRRPs at the national level is compensated by the important role played by expert committees at the service of the supranational executive and domestic governments, resulting in the centralisation of power in so-called core executive structures. This is likely to lead to a legitimacy disequilibrium in the implementation of the RRF at the national level, with implications for the politicisation and contestation of NRRPs.

The legitimacy disequilibrium and politicisation in the implementation of the RRF: The Italian NRRP

Two different versions of the Italian NRRP were elaborated by two consecutive Italian governments between mid-2020 and mid-2022, under the leadership of Giuseppe Conte and Mario Draghi, respectively. While Conte’s plan remained a draft proposal due to his government crisis in early 2021, Draghi’s NRPP was approved by the Italian parliament and submitted to the European Commission on May 1st that year. Both drafts were prepared by the Italian government in close cooperation with EU authorities and in consultation with independent advisory bodies, but with little involvement—if not in a monitoring capacity—of the legislature.Footnote 2 The Italian NRRP drafted by the Conte government envisaged a centralised governance structure, with the Minister for European Affairs as the single point of contact for the European Commission and the Presidency of the Council of Ministers (PCM) [Prime Minister’s Office] directly responsible for managing and implementing the reform and investment programmes. Conte’s draft plan also established a technical Task Force composed of nine experts, six managers and one supervisor, allowing for the centralised monitoring of the reform and investment projects. Finally, an Executive Committee with political oversight powers was set up comprising the prime minister, the Minister of Economy and Finance and the Minister of Economic Development.Footnote 3 While the Conte government published five provisional drafts of the NRRP between 7 December 2020 and 12 January 2021, the final version of the draft recovery programme was sent to parliament only on 15 January, two days after the beginning of a government crisis that would lead to Conte’s resignation as prime minister. Despite the fall of the Conte government and the inauguration of the Draghi government in February 2021, “both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate held discussions based on Conte’s previous NRRP until 30 March and 31 March, respectively, meaning the Italian parliament basically spoke hot air” (Interview A).

After the fall of the Conte government, Draghi’s half-technical half-political cabinet was formed in February 2021 under the aegis of the President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella, to secure an efficient spending of EU funds. Draghi’s recovery plan envisioned an even more centralised governance structure for the management of RRF resources (Bressanelli and Natali Reference Bressanelli and Natali2024) despite initial assurances of a greater parliamentary involvement (Cavatorto et al. Reference Cavatorto, De Giorgi and Piccolino2021). While the point of contact for the Commission was moved to the Ministry of Economy and Finance, a “control room” headed by the prime minister was established at the PCM with powers of political steering and general coordination of the NRRP. In addition, Draghi’s plan established a Technical Secretariat at the PCM with administrative support tasks for the control room as well as a Technical Unit for the rationalisation and improvement in regulation with coordination and resolution powers.

In continuity with the previous plan, the Draghi government’s NRRP was thus the result of attempts at further strengthening the government’s technical-administrative structures to address the challenges of implementing recovery and resilience policies (Guidi and Moschella Reference Guidi and Moschella2021). According to a policy advisor to a cabinet minister in the subsequent Meloni government, working in the legislative office of a party group at the Senate during the previous Draghi government, “due to the technical nature of many measures within the NRRP, the government quickly set up technical-administrative structures, including within the Presidency of the Council, in addition to the state bureaucracy (e.g. the Ragioneria Generale dello Stato and legislative offices). For the same reason, the Italian parliament was excluded from the bilateral dialogues between the government and the Commission on the NRRP” (Interview B). In the end, the Draghi government largely derived its legitimacy from its reputation and the expertise of the prime minister—a longtime technocrat and former president of the European Central Bank (ECB)—as well as of officials in central government structures (including academics, judges, professionals and entrepreneurs), who were indeed appointed based on their technical and professional competences (Interview B, C; Lippi and Terlizzi Reference Lippi and Terlizzi2024).

Draghi eventually presented a provisional version of the Italian NRRP to parliament on 25 April, just five days before the deadline for submission to the European Commission, while the final version of the plan was sent to the chambers later on (Cavatorto et al. Reference Cavatorto, De Giorgi and Piccolino2021). Incidentally, the lack of parliamentary involvement was also mirrored at the local level by the marginalisation of subregional governments (including regions and municipalities) in the design and governance of the plan (Lippi and Terlizzi Reference Lippi and Terlizzi2024; Profeti and Baldi Reference Profeti and Baldi2021). Overall, as a policy officer dealing with the NRRP dossier suggested, “the perception for parliamentary groups was one of irrelevance both because the government prioritised the work of its technical referents but also because it communicated directly with party officials responsible for the NRRP, thus bypassing the competent parliamentary committees” (Interview A).

The elaboration of the Italian NRRP under both the Conte and the Draghi governments thus witnessed a key role of experts and high-level civil servants with administrative and political functions, leading to the concentration of steering, coordination and monitoring powers in the core executive and away from parliament (Bressanelli and Natali Reference Bressanelli and Natali2024; Fabbrini Reference Fabbrini2022). This provides empirical support for the validation of H1, pointing to the emergence of a legitimacy disequilibrium based on a strong technocratic legitimacy and a weak democratic legitimacy in the implementation of the RRF.

The legitimacy disequilibrium stemming from the implementation of the RRF led to the politicisation of the Italian NRRP during both the Conte and the Draghi governments. Such politicisation was by no means confined to the electoral arena, but informed relations between majority and opposition parties in parliament (Cavatorto et al. Reference Cavatorto, De Giorgi and Piccolino2021), as well as relations amongst the parties of the governing coalitions themselves (Guidi and Moschella Reference Guidi and Moschella2021). In late November 2020, Conte circulated his draft NRRP ahead of a cabinet meeting among coalition partners—the Five Star Movement (M5S), Partito Democratico (PD) and Matteo Renzi’s Italia Viva (IV). While the M5S welcomed the plan, the PD and IV opposed aspects of it, making it salient in the Italian public debate. In particular, IV defined the proposal for the establishment of a technical Task Force as an attempt by the prime minister to replace ministers with bureaucrats, thus bypassing parliamentary control (Corriere Della Sera 2020; Guidi and Moschella Reference Guidi and Moschella2021). In mid-December, in an open letter to the prime minister, Renzi argued that the NRPP was a “patchwork of proposals without a soul, without a vision, without an idea of what we want to be in 20 years”, stressing that “we joined the coalition to avoid full powers to [League’s leader] Salvini, we will not allow full powers to others” (Capati et al. Reference Capati, Improta and Lento2023: 8). Shortly before the fall of the Conte government, in late December, IV claimed that the Italian plan lacked ambition and was the product of bureaucracy, threatening to withdraw from the governing coalition in the absence of changes (POLITICO 2021).

Similarly, during Draghi’s premiership, Giorgia Meloni’s right-wing Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy)—at the time the only opposition party in parliament—repeatedly voiced concerns about the lack of parliamentary involvement in the definition of the recovery measures, questioning the legitimacy of the Italian government’s reform and investment plans. Brothers of Italy also condemned Draghi’s enlistment of international private consultancy companies—such as McKinsey—to draft the Italian recovery programme, despite the government’s already extensive reliance on national bureaucratic bodies and technical experts (Il Sole 24 Ore 2021). After repeated calls for greater parliamentary participation in the elaboration of the NRRP, ahead of the September 2022 general elections, Meloni openly vowed to reform the plan in case of electoral success to make sure “funds are used in areas where Italy is more competitive than others” (La Stampa 2022), arguing “we cannot accept a plan that has been locked in the drawer for months and put to a vote with a take-it-or-leave-it approach” (Corriere Della Sera 2021). By highlighting the technocratic hallmarks of the plan and its lack of democratic legitimacy, Meloni’s party was thus able to politicise the NPRR during the electoral campaign, which increased the salience of the Italian recovery plan at the national level. This was either due to Brothers of Italy’s peculiar position as the only opposition party to the Draghi government or to the effective relevance of the issue for the party’s political agenda (Cavatorto et al. Reference Cavatorto, De Giorgi and Piccolino2021).

Overall, the analysis contributes to corroborating the validity of H2 as it shows that the legitimacy disequilibrium resulting from the implementation of the RRF in Italy led to the politicisation of the NRRP in the Italian public discourse. However, a qualification applies. While the politicisation of the Italian plan during the Draghi government was driven by a challenger and traditionally Eurosceptic party—Meloni’s Brothers of Italy—during the previous Conte government the recovery plan became salient due to a mainstream, pro-European and government party instead, which lamented the blatant lack of parliamentary involvement and the centralised, technocratic structure set up by the prime minister to manage RRF funds.

The emergence of political dissensus over the Italian NRRP: the European commission, the Meloni government and Italian opposition parties

The implementation of the RRF through the elaboration of the NRRP has become subject to political dissensus in Italy with the changeover from the Draghi government to the Meloni government in October 2022, giving rise to a political confrontation between the new majority and opposition parties on key reform and investment programmes as well as to concerns from the European Commission over Italy’s ability to implement the agreed projects.

Under Draghi, the Italian government was able to achieve all milestones and targets set out in the NRRP, and the European Commission thus disbursed to the country all fundings available for 2021 and 2022 (Fabbrini Reference Fabbrini2022). However, soon after taking office as prime minister in October 2022, Giorgia Meloni reiterated her intentions to amend Italy’s NRRP, especially in light of changes in the international context following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. She argued that the war urges the government to identify “new strategic priorities” to account for rising costs, mostly in the energy sector. Italian Minister of the Economy, Giancarlo Giorgetti, thus went on to say that the governing coalition “cannot feel responsible for doing things that are today perhaps less urgent and less a priority than two years ago and that would be wrong” (Financial Times 2023a). To this effect, Minister for European Affairs, Raffaele Fitto, committed the Italian government to sending a revised plan to Brussels by the end of June 2023. This, however, contributed to jeopardising the achievement of relevant milestones and targets Italy had originally planned for the year, increasing the Commission’s concerns (Financial Times 2023b).

To this effect, the Meloni government attracted criticism from the parties of the previous governing coalition, which defended the “Draghi agenda”. The PD and the M5S defined the executive’s work on the NRRP as “confusing and sloppy” and asked government representatives to report to the chambers (Corriere Della Sera 2023). All this came after the government had passed an early reform in February 2023 to centralise the governance of the plan under Palazzo Chigi (the executive’s seat), taking full responsibility for the management of RRF resources. Following such a reform, the government replaced the Ministry of the Economy and Finance as the institutional point of contact for the Commission and provided itself with the power to remove public managers and to overcome resistance from local authorities on the use of EU funds (Reuters 2023). The Meloni government’s decision to centralise the governance of the NRRP had already led to contestation from opposition parties, which claimed that the “political confusion” the executive produced would require a “transparency operation and discussion in parliament of the government’s real intentions on the NRRP” (Euractiv 2023). Incidentally, after Giorgia Meloni’s reform of the governance of the plan, some of the technical staff—including senior officials—previously appointed by the Draghi government left by their own will as they believed they were “no longer useful to the cause” and were thus replaced by others (Interview C).

The Meloni government’s intentions to amend the Italian NRRP also spurred a reaction from the European Commission, which made clear that “Italy’s government cannot expect Brussels to renegotiate the fundamentals of a €200bn EU-funded COVID-19 recovery plan and must stick firmly to the reform pledges that Rome has made [under the Draghi government]” (Financial Times 2022). As a senior policy officer at the Presidency of the Council of Ministers disclosed, “the Commission was quite concerned about the handover from Draghi to Meloni. Once that was over, the Commission—more specifically the RECOVER task force—centred its first weekly meetings with the new representatives of the Italian government on the importance of delivering on the reforms already started under the NRRP, emphasising that those reforms would be followed by money” (Interview C). The political dissensus around the Italian NRRP even worsened after the European Commission significantly questioned Italy’s project to renovate a football stadium in Florence and to build two sports facilities in Venice as a means for restoring dilapidated urban neighbourhoods. As a response, the Italian government asked the Commission to “resort to maximum flexibility in using available resources” and agreed to “provide additional elements to support the admissibility of the project”, which was already presented as part of Draghi’s original NRRP (Financial Times 2023c). However, the doubts expressed by the Commission urged Italian authorities to consider a choice between cutting spending under the NRRP or requesting an extension of the plan’s deadline by one year, thus moving it on to 2027. In light of the Italian government’s efforts to amend the recovery plan presented by Draghi, European Commission officials repeatedly insisted on Italy’s respect of agreements under the NRRP, pressuring Rome to “stay on track” (Financial Times 2022).Footnote 4 This provides empirical evidence in support of H3, as it shows that the European Commission responded to the politicisation of the NRRP in Italy to ensure the Italian government’s respect of the reform and investment programmes negotiated with the EU.

Overall, Italy’s implementation of the RRF shows how the legitimacy disequilibrium resulting from a strong technocratic and a weak democratic legitimacy contributed to the emergence of political dissensus through politicisation dynamics. Renzi’s and Meloni’s claims, under the Conte and the Draghi governments, respectively, that the content of the Italian NRRP was overly determined by the government’s external and internal advisory bodies with little input from the Italian parliament, indeed opened the doors to the politicisation of the issue. The media attention given to the design of the Italian recovery plan ensured that it became one of the most salient issues in the Italian public debate. The politicisation of the Italian recovery plan thus paved the way for the emergence of political dissensus, involving claims and counterclaims by different kind of actors at different levels and with different aims. The Meloni government’s steps to revise the recovery projects Italy had originally agreed with the European Commission triggered a political confrontation about the use of RRF funds. Political conflict emerged at the national level between majority and opposition parties over the content and governance of the NRRP and at the EU level between the Italian government and the European Commission over Italy’s compliance with the reform and investment programmes previously agreed by the Draghi government with Brussels. It is this form of political contestation related to legitimacy aspects and driven by the interaction between actors of a different nature (EU institutions, governments and parties), operating at different levels (EU and national), and with different aims (e.g. ensuring delivery by national governments or defining the content of policy measures) that we associate with “political dissensus”.

Conclusion

This article examined the links between legitimacy, politicisation and the rise of political dissensus in the context of the implementation of the RRF. In particular, it identified three forms of legitimacy—democratic, technocratic, and procedural—and assessed them against the vertical, inter-level relations between EU institutions and national authorities in the elaboration of NRRPs, with a focus on the Italian case. As is shown, the involvement of national parliaments has been marginal, undermining democratic (or input) legitimacy. The emphasis instead has rather been on technical (output) and procedural (throughput) legitimacy channels, with a significant involvement in the policymaking of EU and national independent expert committees at the service of member state governments. Even though procedural rules foster a high degree of transparency, decision-making powers in the implementation of the RRF are mostly in the hands of governments and technocratic actors, while opportunities for parliamentary involvement in the process remain limited.

The article makes both a theoretical and an empirical contribution. Theoretically, it engaged with, and challenged, the recent literature on coordinative Europeanisation in three respects. First, building on the Europeanisation of the core executive literature, the article illustrated how the implementation of the RRF fosters the centralisation of powers in national executives and their technical-administrative structures at the expense of national legislatures. This, we argued, gives rise to a “legitimacy disequilibrium” in the implementation of the RRF characterised by a strong technocratic and a weak democratic legitimacy. Second, following post-functionalism theorising, the article showed that the implementation of the RRF is not immune to politicisation processes. On the contrary, the legitimacy disequilibrium resulting from the implementation of the RRF is susceptible to politicisation by national party actors, which makes it a salient issue in national public debate. Finally, drawing on the literature on EU agenda responsiveness, the article investigated how the politicisation of NRRPs has the potential to engender political dissensus, involving different types of actors (EU institutions, national governments and national parties), at different levels (EU and national), and with different aims.

Empirically, the article looked at the implementation of the RRF in Italy to illustrate the effects of the legitimacy disequilibrium in a most likely case for the rise of political dissensus. It showed how the limitations to parliamentary involvement in the elaboration of the Italian NRRP, coupled with the Conte- and Draghi governments’ extensive reliance on independent advisory bodies, fuelled the politicisation of the issue by a small party of the governing coalition and the main opposition party, respectively. This pushed a matter hitherto considered technocratic into the realm of party politics and thereby made room for political dissensus. The article thus shed light on the origins, actors and goals of political dissensus in EU economic governance through the case of Italy. Political dissensus originated from the politicisation of the national implementation of the RRF. In turn, such a politicisation stemmed from a legitimacy disequilibrium, that is, the perception that the Italian NRRP was elaborated by the government and bureaucrats with little parliamentary involvement. Political dissensus was driven by national actors, most notably political parties, and then spilled over into the EU arena, with a confrontation between the European Commission and the Italian government. Finally, the goals of political dissensus were twofold. At the national level, majority and opposition parties dissented on the specific content and governance of the Italian NRRP with a view to influencing the substance of the plan in line with their preferences. At the EU level, the European Commission confronted the Meloni government to ensure its willingness to comply with the reform and investment programmes previously agreed with Brussels by the Draghi government.

The single case study constitutes a limitation of the article. Italy is a particular case and can therefore not be considered as representative of implementation patterns in all or most of the EU member states. Some of the observed developments may indeed be exceptional to the more general trend of depoliticised decision-making and increased coordination between EU and national authorities in the implementation of the RRF. We would argue, however, that evidence from the Italian case nevertheless provides valuable insights. It demonstrates that the potential for politicisation and conflict dynamics in the implementation of EU policies does exist, and illustrates how these dynamics are linked to the legitimacy of EU economic governance.

Finally, while the study of the Italian case provides valuable insights, further comparative research is needed to establish more generally the conditions under which the mechanisms of consensus-seeking, mutual learning and national ownership, theorised by coordinative Europeanisation, are likely to prevail in the implementation of the RRF as opposed to the processes of politicisation and political dissensus identified in this research.

Appendix

Interviews

Interview A—policy officer, majority party group during Draghi government, Senate of the Republic, in person, 5 November 2024.

Interview B—policy advisor to cabinet member in Meloni government, on the phone, 8 November 2024.

Interview C—senior policy officer, Presidency of the Council of Ministers, in person, 11 November 2024.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the guest editors of this special issue as well as the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. This paper was presented at the CES conferences in Reykjavik (June 2023) and Lyon (July 2024) and at the SISP conference in Trieste (September 2024). The authors are grateful to Matilde Ceron, Cristina Fasone and Lucia Quaglia for their valuable feedback on these occasions as well as to Sofia Eliodori for her precious research assistance.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Luiss University within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This work was funded by RED-SPINEL (Respond to Emerging Dissensus: SuPranational Instruments and Norms of European democracy), a Horizon Europe’s project under Grant 101061621.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.