Personality disorders are common, affecting 9–12% of the general population, Reference Volkert, Gablonski and Rabung1,Reference Winsper, Bilgin, Thompson, Marwaha, Chanen and Singh2 up to 52% of psychiatric out-patients and even higher numbers in in-patient settings. Reference Beckwith, Moran and Reilly3,Reference Zimmerman, Chelminski and Young4 In the Italian mental health system, personality disorders, mainly borderline personality disorder (BPD), constitute 14% of patients treated in community services and 20% of hospital admissions in psychiatric emergency wards. Reference Sanza, Monzio Compagnoni, Caggiu, Allevi, Barbato and Campa5 Despite this, mental health professionals often feel unprepared to manage patients with personality disorders. Reference Baker and Beazley6 Clinical encounters with these patients can evoke feelings of frustration and inadequacy, leading to negative views of patients with BPD. Reference Commons Treloar and Lewis7 Concerningly, negative attitudes towards patients with personality disorders seem to worsen as psychiatric trainees progress in their careers. Reference Lindell-Innes, Phillips-Hughes, Bartsch, Galletly and Ludbrook8 Education and training in personality disorder management have been shown to improve attitudes and clinical confidence, even with brief interventions. Reference Masland, Price, MacDonald, Finch, Gunderson and Choi-Kain9,Reference Shanks, Pfohl, Blum and Black10 Yet, there is a documented gap in psychiatry trainees’ education about the assessment and management of patients with personality disorders. Reference Sansone, Kay and Anderson11

Transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP) is an evidence-based treatment for patients with personality disorders. Reference Oud, Arntz, Hermens, Verhoef and Kendall12,Reference Crotty, Viswanathan, Kennedy, Edlund, Ali and Siddiqui13 Rooted in psychoanalytic principles, TFP emphasises a structured therapeutic framework, goal setting, firm boundaries and techniques for using transference and countertransference. Reference Yeomans, Clarkin and Kernberg14 TFP has been used as a training tool, with positive results in several settings. Reference Arif Abdul Rassip, Mohamed, Razali, Rasidi and Lee15–Reference Kanter Bax, Nerantzis and Lee19

Our study aims to evaluate whether a series of teaching sessions on TFP theory and techniques as applied to personality disorders can improve psychiatric trainees’ attitude and technical confidence in a clinical encounter with a patient with a personality disorder, and the acceptability of such training.

Method

We implemented a mixed-methods approach that incorporated quantitative and qualitative data collection methods, using validated questionnaires to measure pre versus post changes in attitudes and confidence, and a subsequent focus group.

Description of the training modules

In November 2023, two 4-h training sessions, spaced 3 days apart, were held in person at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, in the North Italy. The training was delivered to residents in psychiatry from all stages of training (specialisation in psychiatry lasts 4 years in Italy), focusing on the theory and clinical application of TFP in the management of BPD. All residents in psychiatry of the university were invited to participate in the training 1 month in advance, with reminder after 2 weeks, both sent via email. Participation in the training was voluntary, as well as participation in the training evaluation (completion of questionnaires and taking part in the focus group).

Each workshop began with an introduction to the fundamental principles of TFP, covering object relations theory and key techniques such as working within the transference and countertransference, use of technical neutrality and systematic use of clarification, confrontation and interpretation. Theory sessions were followed by live role-plays featuring a fictional patient with BPD presenting with suicidality – first in an emergency room setting, and later in a community clinic. Between the first and the second sessions, a freely accessible educational paper was circulated among the participants. Reference Lee and Hersh20 Before the second session, participants were asked to prepare and share clinical material used for case-based discussion in the second half of the session.

The training was delivered in English by a TFP-certified teacher and supervisor (T.L.), with simultaneous Italian translation by a TFP therapist in training (A.S.).

Quantitative phase

Participants completed two questionnaires at the beginning of the first session and the end of the second session, online, through the RedCap platform Reference Harris, Taylor, Minor, Elliott, Fernandez and O’Neal21 : the Attitudes to Personality Disorder Questionnaire (APDQ) Reference Bowers and Allan22 and the Clinical Confidence with Personality Disorder Questionnaire (CCPDQ). Reference Reid and Lee23 The APDQ is a validated 35-item scale that measures positive and negative attitudes towards personality disorders. It consists of a total score and five subscales, measuring one positively phrased attitude (enjoyment versus loathing) and four reverse-coded, negatively phrased attitudes (security versus vulnerability, acceptance versus rejection, purpose versus futility and enthusiasm versus exhaustion). The CCPDQ assesses confidence in applying a psychodynamic framework to personality disorders, focusing on TFP. It includes items evaluating confidence in conveying diagnoses of borderline and narcissistic personality disorders, establishing treatment contracts and objectives, managing countertransference and transference, applying object relations theory and maintaining technical neutrality. The CCPDQ has demonstrated face validity, and formal validation research is ongoing. Both questionnaires are scored on a six-point Likert scale. To be able to pair pre- and post-training questionnaires and evaluate any possible change while maintaining anonymity, we asked participants to sign the questionnaire by using an alphanumeric code.

Changes in the scores of the two questionnaires have been evaluated with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired observations. The test was two-tailed, and the level of statistical significance was 0.05. The effect size (r) was qualitatively assessed as small, moderate or large according to Cohen guidelines. Reference Cohen24

Qualitative phase

Following the quantitative data collection, we conducted an in-presence focus group to gather qualitative insights into the acceptability and perceived utility of the training. We employed a convenience sampling strategy, comprising an in-block randomisation by year of residency to ensure at least each year of residency was represented, to recruit a total of eight psychiatric trainees who participated in the teaching sessions. The focus group utilised the SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) framework to systematically assess the training programme, Reference Benzaghta, Elwalda, Mousa, Erkan and Rahman25 consistent with its application in other medical education evaluations. Reference Topor, Dickey, Stonestreet, Wendt, Woolley and Budson26–Reference McCarron, FitzGerald, Swann, Yang, Wraight and Arends29 Additionally, we explored educational needs, future curriculum development opportunities, and potential obstacles to implementation.

An external researcher (G.I.) facilitated the focus group discussion, allowing participants to express themselves freely. The discussion was recorded and transcribed. The thematic analysis was performed by two researchers not involved in the teaching phase (L.G. and G.I.), who organised the data by using the SWOT framework.

Ethics statement

Participants gave written informed consent, which was witnessed and recorded. Ethical clearance to conduct this study was obtained from the University Local Ethic Committee (protocol number 57/2022/SPER/UNIRE). Data were anonymised upon collection.

Results

Sample characteristics

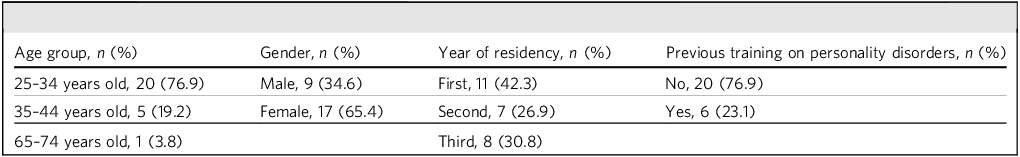

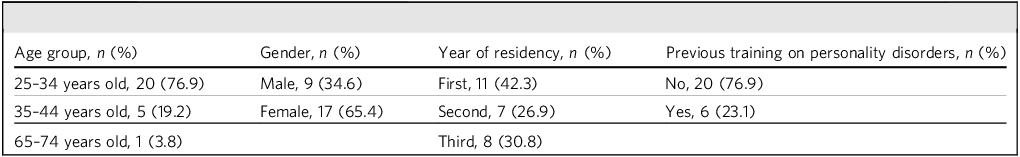

The invitation was sent to 47 residents in psychiatry. The first training session was attended by 37 participants, and the second by 34 participants (participation rate 78.7 and 72.3%, respectively). The baseline questionaries were completed by 30 participants, and the post-training ones were completed by 32 participants. Data were matched for 26 pairs who completed both pre- and post-training questionnaires. Table 1 contains the demographic and background characteristics of the participants.

Table 1 Characteristics of participants filling in both pre- and post-training questionnaires

The focus group, lasting 90 min, involved eight trainees (five women and three men) who completed the training.

Quantitative results

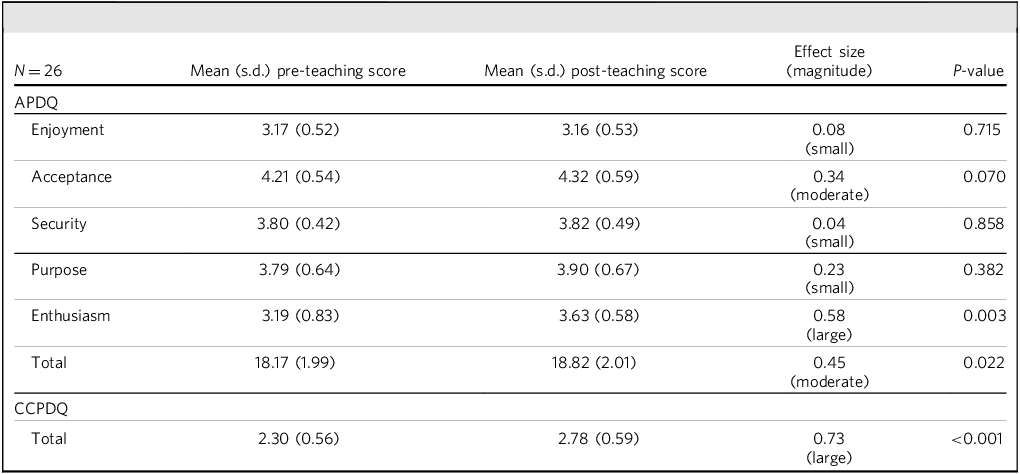

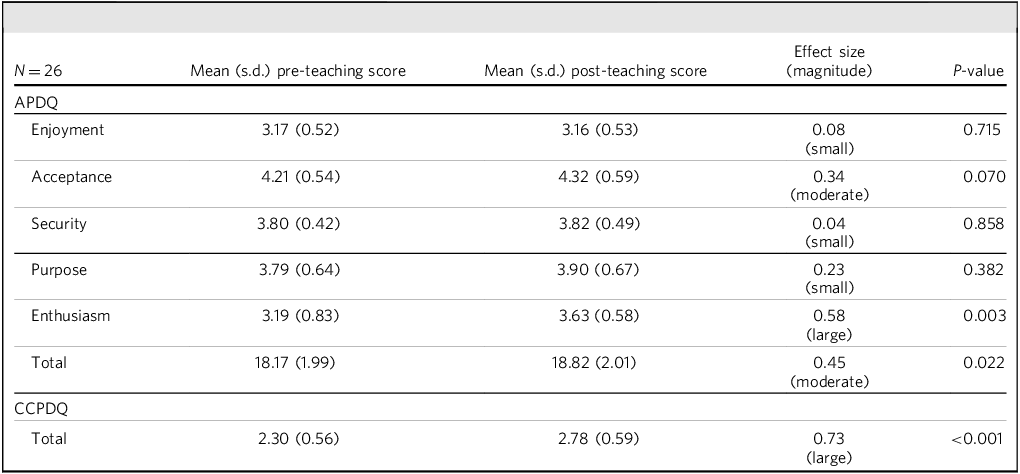

Table 2 presents pre- and post-teaching subscales and total APDQ and CCPDQ scores. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated a statistically significant improvement in the total APDQ score (P = 0.022, r = 0.45) and on the APDQ Enthusiasm subscale (P = 0.003, r = 0.58), with moderate and large effect sizes, respectively. Reference Cohen24 There were no significant improvements in the single APDQ Enjoyment, Acceptance, Security or Purpose subscales. The analysis of the CCPDQ scores, assessing confidence in the management of personality disorders by using a psychodynamic approach, also showed a statistically significant improvement (P < 0.001, r = 0.73) with a large effect size.

Table 2 Pre- and post-teaching scores on the APDQ and CCPDQ

APDQ, Attitude to Personality Disorders Questionnaire; CCPDQ, Clinical Confidence with Personality Disorder Questionnaire.

Notably, comparisons between paired and unpaired respondents did not reveal any significant differences in pre- or post-teaching scores, suggesting that attrition was unlikely to have introduced relevant bias (detailed comparisons are reported in Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2025.10185).

Qualitative results

Participants considered the TFP training engaging and relevant for clinical application. However, it was seen as overly theoretical, as participants expressed a preference for a more hands-on element. Trainees recognised the relevance of the content in enhancing their emotional awareness and fostering critical reflection during patient interactions. This was achieved by clarifying the conceptual foundations for effectively managing patients with personality disorder. In this context, the requirement to submit clinical cases before training cultivated the perception that the sessions were more practical. Although case discussions were incorporated, trainees wanted a greater emphasis on practical applications.

Participants felt the training provided an opportunity to understand and emphasise psychodynamic perspectives in psychiatric care teams while enhancing therapeutic skills. The significance of peer support was underscored in tackling the common challenges of managing patients with personality disorders.

Participants said that this form of training could optimise educational outcomes if implemented at various stages during their specialisation and reinforced over time. They also said it could facilitate intergenerational learning, and that mixed-cohort sessions involving trainees from different academic years could promote more substantive discussions and mutual understanding.

The primary barriers to the training’s effectiveness were organisational. Participants cited the limited number of sessions, the condensed scheduling during regular working hours and using English as the instructional language without sufficient breaks as obstacles to effective learning. Moreover, the absence of clear shared protocols for managing personality disorders in the local work settings and the contextual challenges of transferring knowledge to real-world clinical settings further complicate the implementation of TFP principles.

The focus group identified key training needs worth addressing, specifically, understanding TFP as well as knowing its limitations concerning specific personality disorders; familiarity with alternative therapeutic approaches when TFP proves ineffective; enhancing emotional competence to recognise and manage personal responses during patient interactions; and development of expertise in managing transference and countertransference as well as upholding professional standards, especially when patients show challenging behaviours.

Ultimately, to improve the transferability of TFP principles into clinical practice, there was a call to establish supervisors in key clinical settings to offer ongoing feedback and guidance, including considerations for the potential emotional impact on professionals.

Discussion

Our study indicates that even a brief training in TFP can lead to statistically significant improvements in both attitudes and confidence regarding the management of personality disorders. Significant changes were observed in the overall APDQ score and in the enthusiasm subscale. This subscale is particularly relevant as lower scores reflect frustration and emotional exhaustion, suggesting that short-term training may help alleviate negative emotions associated with treating patients with personality disorder.

Moreover, we identified a statistically meaningful improvement in clinical confidence when applying TFP principles, as assessed by the CCPDQ. These findings align with previous research on TFP training among UK and Malaysia psychiatric trainees Reference Arif Abdul Rassip, Mohamed, Razali, Rasidi and Lee15,Reference Sinisi, Marchi, Prior and Lee17 and South Africa mental health practitioners, Reference Temmingh, Fanidi, Bracken and Lee16 where confidence in utilising TFP techniques showed a notable increase. Our results differ from those of Temmingh et al, who did not find a significant improvement in the APDQ total score. Reference Temmingh, Fanidi, Bracken and Lee16 These findings add to a growing body of research on teaching mental health professionals in personality disorders and improving attitudes. Existing studies on the Knowledge and Understanding Framework, Reference Finamore, Rocca, Parker, Blazdell and Dale30 Good Psychiatric Management Reference Keuroghlian, Palmer, Choi-Kain, Borba, Links and Gunderson31 and Mentalization-Based Treatment Reference Lee, Grove, Garrett, Whitehurst, Kanter-Bax and Bhui32 indicate that different psychological models are effective vehicles for this purpose. Our results match the evidence suggesting that training in TFP during residency can provide an applicable model for understanding and treating personality pathology in various settings. Reference Kanter Bax, Nerantzis and Lee19,Reference Moscara and Bergonzini33–Reference Zerbo, Cohen, Bielska and Caligor35

The focus group findings indicate that participants appreciated the theoretical and psychodynamic aspects of the TFP training, recognising their potential to enhance their professional skill set. This perspective contrasts with the broader trend observed over the past several decades, where psychotherapy training has significantly declined in psychiatric residency programmes. Psychiatry and behavioural health have increasingly moved away from psychodynamic approaches. Reference Plakun36,Reference Holoshitz, Lindy and Albright37 Several factors may contribute to this shift, including limited time and financial resources; the popularity of brief, evidence-based therapies like cognitive behavioural therapy; and an increasing focus on biological treatment approaches. Reference Holoshitz, Lindy and Albright37 The findings regarding the acceptability of TFP training warrant further investigation. Future research should integrate these results with exploring psychiatrists’ perceptions of its acceptability in their practice. Reference Moscara and Bergonzini33

Our participants expressed a clear desire for more practical, hands-on experiences. This preference aligns with adult learning theory principles, which emphasise practical, experience-based learning tailored to adult learners. Reference Lippitt, Knowles and Knowles38 Consistent with these principles, participants underscored the importance of incorporating case-based learning through direct observation and supervised clinical discussions to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

Our participants identified challenges they might face in clinical practice, as indicated elsewhere. Reference Moscara and Bergonzini33 Insufficient training has been shown to heighten feelings of anxiety among psychiatrists, contributing to the tendency to avoid diagnosing personality disorders because of a perceived lack of preparation. Reference Hersh39 Findings from the focus group support this notion, as participants felt that greater practical exposure and skill development would make them more confident in managing patients with personality disorders. Participants emphasised that integrating supervised case discussions and practical application of TFP techniques would not only enhance their technical competence, but also reduce the discomfort and uncertainty often associated with diagnosing and treating these complex conditions.

In this direction, they recommended embedding TFP training as a recurring, annual component of the psychiatry curriculum to facilitate progressive skill development and deeper conceptual integration. Participants proposed restructuring the course delivery by spreading sessions over multiple days to enhance learning outcomes, thereby reducing cognitive overload and fostering better knowledge retention. These insights are crucial when designing training programmes for adult learners, mainly when introducing complex psychotherapeutic models and practices.

Strengths and limitations

The training was delivered by clinicians with substantial experience in the treatment of personality disorders and specific expertise in TFP. This represents an important strength of the training, as the trainers’ competence and knowledge likely contributed to the effectiveness of the intervention and its acceptability among trainees. However, this also raises considerations regarding feasibility. In some training programmes, particularly those in smaller or more resource-limited settings, access to clinicians with this level of specialised expertise may be more limited, which could present challenges for implementing similar initiatives.

The strength of the quantitative analysis lies in the use of paired data, allowing each participant to serve as their own control. However, several limitations must be considered when interpreting the results. First, the use of de-identified data, relying on an alphanumeric code for each participant, may have limited the accurate matching of pre- and post-training responses. Although this has ensured anonymity for each participant in the questionnaire completion, some participants may have forgotten or misspelled their code during data entry, leading to incomplete pairing and reduced sample size for the analyses. Second, the study was conducted at a single centre, restricting the generalisability of the findings to other residency programmes or countries with different mental health systems. Third, participation in the training was voluntary, meaning that only residents with a particular interest in personality disorder may have enrolled, introducing a potential selection bias. The direction of this bias remains uncertain: highly motivated participants might have responded more favourably to the training, overestimating its effectiveness, or, conversely, they might have held higher expectations, leading to more critical evaluations. Fourth, the absence of follow-up assessments and supervision on the application of acquired knowledge represents another limitation in evaluating the training’s long-term impact.

The focus group’s strength lay in generating discussion among trainees, revealing benefits and limitations of TFP training. The SWOT framework enabled structured evaluation, highlighting actionable improvements and future strategies. However, the convenience sample may have introduced bias, limiting findings’ broader applicability to psychiatric trainees. Notably, the single focus group captured perceptions at one moment, potentially missing longitudinal changes.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that even brief training in TFP can significantly improve psychiatric trainees’ attitudes and confidence in managing patients with personality disorders. Notably, we observed a meaningful improvement in the overall attitude towards patients with personality disorders, and more specifically in the enthusiasm domain, suggesting that such training may alleviate the frustration often associated with working with patients with personality disorder. Additionally, trainees reported enhanced technical confidence in applying TFP principles, reinforcing the value of incorporating psychodynamic approaches into psychiatric training.

The acceptability of TFP training was also highlighted, with participants expressing appreciation for its theoretical and psychodynamic components. However, they emphasised the need for more practical, hands-on experiences, aligning with adult learning principles that prioritise experiential and case-based learning. The perceived lack of sufficient training in personality disorders has been linked to anxiety and avoidance in clinical practice, and our findings suggest that integrating supervised case discussions and structured skill development can help address these challenges.

Based on our results, we recommend that when TFP is embedded in psychiatric training, it is delivered as a recurring component of psychiatric education, in a spaced format to optimise learning and retention. Future research should further investigate the long-term impact of TFP training on clinical practice and explore strategies for overcoming barriers to its broader implementation. Our findings contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting psychotherapy training in psychiatric education, and reinforce the role of psychodynamic approaches in improving clinicians’ confidence and engagement with patients with personality disorders.

About the authors

Dr Arianna Sinisi, MD, is a psychiatrist at the Camden and Islington Personality Disorder Service, North London NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. Dr Mattia Marchi, MD, PhD, is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Department of Biomedical, Metabolic and Neural Sciences, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy; and psychiatrist at the Department of Mental Health and Drug Abuse at Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy. Prof. Luca Pingani, PhD, is an associate professor in Rehabilitation Healthcare Professions at the Department of Biomedical, Metabolic and Neural Sciences, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy; and Director of Healthcare Professions at the Department of Mental Health and Drug Abuse, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy. Dr Luca Ghirotto, PhD, is a methodologist and director at the Qualitative Research Unit, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy. Dr Giusy Iorio, MA, is a research fellow at the Qualitative Research Unit, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy. Prof. Gian Maria Galeazzi, MD, PhD, is a professor of Psychiatry at the Department of Biomedical, Metabolic and Neural Sciences, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy; and a psychiatrist and director at the Department of Mental Health and Drug Abuse, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy. Dr Tennyson Lee, MD, FRCPsych, M Inst. Psychoanal. FFCH(SA), is a psychiatrist, clinical lead at DeanCross Tower Hamlets Personality Disorder Service, East London NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2025.10185.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, M.M., upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

T.L., A.S., M.M., G.M.G. and L.P. contributed to the design and conceptualisation of the study, and edited subsequent versions of the article. M.M. and L.P. managed the data acquisition. T.L. and A.S. were involved in the study procedures of teaching the clinical model and conducting the role plays. M.M. curated and analysed the quantitative data. L.G. defined the focus group method and G.I. conducted it. G.I. and L.G. analysed qualitative data. A.S. wrote the first draft. A.S., M.M. and L.G. reviewed the draft. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.