Around the world, women are typically less likely to participate in politics than men (Burns et al. Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Desposato and Norrander Reference Desposato and Norrander2009; Fakih and Sleiman Reference Fakih and Sleiman2024). In sub-Saharan Africa, where youth and adults under the age of thirty-five constitute 75 per cent of the population,Footnote 1 this gender gap is most extreme among young adults (Butegwa and Charmaine Reference Butegwa and Charmaine2020; Lekalake and Gyimah-Boadi Reference Lekalake and Gyimah-Boadi2016). Young men consistently report a greater willingness than young women to discuss politics, join others to address problems, volunteer for political campaigns, attend community meetings, and contact elected officials (Hern Reference Hern2018; Logan and Bratton Reference Logan and Bratton2006). Although reducing gender gaps in political participation does not automatically close gaps in substantive representation of women (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1969), evidence suggests that the questions of turnout and substantive representation are linked.Footnote 2

Governments and civil society organizations often seek to address the gender gap by providing adult civic education, that is, information about the country’s political system and citizens’ rights and responsibilities (Kalla and Porter Reference Kalla and Porter2022; Gottlieb Reference Gottlieb2016a, Reference Gottlieb2016b). The reasoning is straightforward: political knowledge is a key ingredient in political participation (Delli Carpini and Keeter Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996). Newer to the political system, young adults are presumed to require additional information to participate (Gill et al. Reference Gill, Whitesell, Corcoran, Tilley, Finucane and Potamites2020). Moreover, young women report less political knowledge than young men (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2022; Burns et al. Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Delli Carpini and Keeter Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996; Pereira Reference Pereira2019; Reifen-Tagar and Saguy Reference Reifen-Tagar and Saguy2021), and civic education programs have had compensatory effects for other demographic groups with relatively low initial levels of political knowledge, such as children of immigrants (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell and Niemi2016; Finkel and Smith Reference Finkel and Smith2011; Neundorf et al. Reference Neundorf, Niemi and Smets2016; Willeck and Mendelberg Reference Willeck and Mendelberg2022). It is therefore reasonable to expect that providing civic education to young adults would increase participation and reduce the gender gap in this age group.

However, recent studies reveal that adult civic education programs rarely achieve this goal. In many cases, these information-focused programs have null effects on participation or increase men’s and women’s participation at similar rates, leaving the gender gap unchanged (Finkel Reference Finkel2002; Finkel and Lim Reference Finkel and Lim2021; Finkel and Smith Reference Finkel and Smith2011; Harris et al. Reference Harris, Kamindo and Van der Windt2021; Kalla and Porter Reference Kalla and Porter2022; Mvukiyehe and Samii Reference Mvukiyehe and Samii2017; Weinschenk and Dawes Reference Weinschenk and Dawes2022). In other cases, providing civic information to men and women has exacerbated the gender gap, increasing men’s participation but decreasing women’s (Gottlieb Reference Gottlieb2016a, Reference Gottlieb2016b).

Why doesn’t adult civic education reduce gender gaps in political participation? Political participation is a product of material, social, psychological, and informational barriers (Burns et al. Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001). In some settings, women are economically worse off than men or are legally or socially barred from participating in public life (Bleck and Michelitch Reference Bleck and Michelitch2018; Cheema et al. Reference Cheema, Khan, Liaqat and Mohmand2023). In these places, women are likely unable to act on information provided by civics courses. Yet, even when women face no major legal or socio-economic barriers to political participation, they still face psychological barriers to participation (Burns et al. Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Preece Reference Preece2016; Wolak Reference Wolak2020, Reference Wolak2018). As Wolak (Reference Wolak2020) argues, paying attention to and acting on political information requires a certain self-confidence and sense of efficacy that women tend to lack relative to men: indeed, gender gaps in efficacyFootnote 3 persist even among people with similar material resources and similar experiences of parental socialization into politics (Wolak Reference Wolak2020).

The consequences of gender gaps in efficacy for political participation are significant. Women with less confidence in their ability to act efficaciously tend to have lower levels of interest in politics (Preece Reference Preece2016; Wolak Reference Wolak2020), a critical ingredient in political participation (Finkel Reference Finkel2002; Prior Reference Prior2010). A weaker sense of efficacy is also linked to greater risk aversion (Fraile and de Miguel Moyer Reference Fraile and de Miguel Moyer2022) and lower levels of political anger (Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Gregorowicz and Groenendyk2009; Young Reference Young2020), factors that can constrain political participation (Kam Reference Kam2012; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Gregorowicz and Groenendyk2009). Civic education programs might therefore reduce gender gaps in political participation more successfully if they cultivate psychological resources, such as efficacy, in addition to providing civic information.Footnote 4

In this paper, we investigate whether civic education that provides political information and encourages a strong sense of efficacy can reduce the gender gap in political engagement among young voting-age adults. We conducted a pre-registered,Footnote 5 community-collaborative field experiment with urban young adults in the months preceding Zambia’s 2021 general elections. Blocking on gender, we randomly assigned 775 participants to one of two versions of a two-week-long civic education course administered via WhatsApp. Both courses provided identical civic information; one also presented messages designed to increase participants’ sense of efficacy. Although focusing on urban youth may limit the generalizability of our findings, urban areas in Zambia typically present young women with lower social costs for violating gender norms, relative to rural areas, and they are settings where young women’s educational and employment opportunities (or lack thereof) more closely approximate young men’s (Evans Reference Evans2018; Gough et al. Reference Gough, Chigunta and Langevang2016; Musonda Reference Musonda2022). Accordingly, urban areas are where psychological barriers are likely to play a significant role in gender gaps in political participation and where legal, social, and material barriers are likely to be (relatively) less formidable.

Across a range of behavioral and attitudinal measures collected prior to and immediately following the elections, we find that the efficacy course reduced gender gaps in political participation. The treatment increased both intended and actual participation among young women more than among young men, relative to the information-only course and to baseline. Exposure to the information-only course did not significantly reduce the gender gap in political participation, relative to baseline. In an exploration of mechanisms, we find that the efficacy course increased young women’s interest in politics and, to an extent, their willingness to take risks.

This paper makes several contributions. First, it provides new field experimental evidence further underscoring the critical role that women’s sense of efficacy can play in increasing their relative political participation – a role that scholars have highlighted in the United States and Europe (Fraile and de Miguel Moyer Reference Fraile and de Miguel Moyer2022, chapter 2; Holbein and Hillygus Reference Holbein and Hillygus2020; Karpowitz and Mendelberg Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2018; Preece Reference Preece2016; Wolak Reference Wolak2020) but that is also consequential in other world regions. Along similar lines, the paper advances understanding of urban political behavior in developing contexts: young women in urban areas may be relatively more free from social and material constraints to political participation than rural women (Bleck and Michelitch Reference Bleck and Michelitch2018; Gottlieb Reference Gottlieb2016b; Prillaman Reference Prillaman2023), but they still face psychological impediments to political participation and often exhibit low levels of interest in politics. Even short-term boosts in efficacy may therefore go a long way towards closing the gender gap in urban young women’s political participation. Additionally, we address the literature on civic education (see, for example, Campbell Reference Campbell2019; Finkel et al. Reference Finkel, Horowitz and Rojo-Mendoza2012; Finkel and Lim Reference Finkel and Lim2021; Finkel and Smith Reference Finkel and Smith2011; Gottlieb Reference Gottlieb2016b; Kalla and Porter Reference Kalla and Porter2022; Mvukiyehe and Samii Reference Mvukiyehe and Samii2017) and call for greater attention to the conditions under which increasing psychological resources among young adults (Holbein and Hillygus Reference Holbein and Hillygus2020) may disproportionately increase young women’s political participation. This paper also contributes to discussions about research design and measurement. Community collaborative methods and a cross-country team of authors allowed for evaluation of the cultural acceptability of the courses. Along with our community partners, we recognized that youth political participation goes beyond voting (Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Resnick, Bob-Milliar, Hazen and Patterson2023), and that studies of participation sometimes ignore forms of participation that appeal to women more than men, such as volunteering (M’Cormack-Hale Reference M’Cormack-Hale2015). Accordingly, we collected a wide range of behavioral measures of participation, such as online activity, listserv sign ups, and volunteering. Finally, delivering our young adult civic education courses over WhatsApp allowed for a digital intervention that appealed to young adults and ensured greater privacy for course participants than face-to-face interventions – benefits that our partner organizations highlighted during the study’s design phase.

Beyond Political Information: Cultivating a Sense of Efficacy

Scholars of gender and politics have long noted gender gaps in political participation, political interest, and political information (Burns et al. Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Delli Carpini and Keeter Reference Delli Carpini, Keeter, Tolleson-Rinehart and Josephson2016; Verba et al. Reference Verba, Burns and Schlozman1997). These gaps manifest in a wide range of political behaviors aside from voting (Prillaman Reference Prillaman2023). They result from relative deprivation along many dimensions, including deprivations in material and social resources (Bennett and Bennett Reference Bennett and Bennett1989; Bleck and Michelitch Reference Bleck and Michelitch2018; Burns et al. Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001). For instance, gender gaps in political participation can derive from legal or strong religious prohibitions on women’s active roles in public affairs (Bleck and Michelitch Reference Bleck and Michelitch2018; Cheema et al. Reference Cheema, Khan, Liaqat and Mohmand2023), limited access to education and the labor market (Verba et al. Reference Verba, Burns and Schlozman1997), and gendered socialization of children into politics (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2022; Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2014; Reifen-Tagar and Saguy Reference Reifen-Tagar and Saguy2021).

We underscore that relative deprivations in psychological resources also contribute to gender gaps in political interest, information, and participation. A growing body of evidence connects gender gaps in political interest to women’s relatively lower levels of sense of efficacy compared to men (Bennett and Bennett Reference Bennett and Bennett1989; Delli Carpini and Keeter Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996; Preece Reference Preece2016; Wolak Reference Wolak2020, Reference Wolak2018). Wolak (Reference Wolak2020) argues that a sense of efficacy can enhance women’s political interest by fostering a sense of agency in understanding and applying political information. Similarly, Preece (Reference Preece2016) shows that women randomly assigned to receive positive feedback on their efficacy exhibit greater interest in politics. If a heightened sense of efficacy boosts women’s political interest, it may in turn increase their relative political participation in contexts where psychological barriers are major impediments to participation. Political interest has important downstream consequences for various types of political engagement, such as attention to political information, political discussion, and voting (Delli Carpini and Keeter Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996; Prior Reference Prior2010), and for the uptake of civic education (Finkel Reference Finkel2002). People who report high levels of political interest pay more attention to political information, talk more with others about politics, and exhibit greater intrinsic motivation to engage in political activities.

In addition to the indirect effects that efficacy may exert on political participation via political interest, efficacy may also influence participation through other pathways. Increases in general efficacy can heighten a sense of both internal and external political efficacy.Footnote 6 Individuals with greater political efficacy are more confident that they will take the ‘right’ political actions and will make a difference (Lieberman and Zhou Reference Lieberman and Zhou2020; Niemi et al. Reference Niemi, Craig and Mattei1991; McClendon and Riedl Reference McClendon and Riedl2019). Research has also linked efficacy to emotional responses that matter for participation: individuals with higher levels of efficacy are more likely to react to political events with anger, which propels engagement, rather than fear, which often leads to withdrawal from politics (Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Gregorowicz and Groenendyk2009; Young Reference Young2020). Efficacy has also been found to moderate anxiety (Rudolph et al. Reference Rudolph, Gangl and Stevens2000), increasing the likelihood of political action. Fraile and de Miguel Moyer (Reference Fraile and de Miguel Moyer2022) documented that higher levels of efficacy correlated with higher risk acceptance, while Kam (Reference Kam2012) and others have argued that increased risk-acceptance can make people perceive politics as more exciting, thereby increasing the utility of political participation.

Each of these mechanisms linking efficacy to political participation is likely to be particularly important among young people (Condon and Holleque Reference Condon and Holleque2013; Holbein and Hillygus Reference Holbein and Hillygus2020), perhaps especially young women. Although political interest becomes more stable in adulthood than in adolescence (Fraile and Sánchez-Vítores Reference Fraile and Sánchez-Vítores2020), political interest is still malleable in adulthood (Preece Reference Preece2016) and likely to be more malleable in early adulthood. Young adults are also relatively new to the political arena (Holbein and Hillygus Reference Holbein and Hillygus2020), and those who are new to a domain tend to rely more on general psychological attitudes, such as self-efficacy, when assessing the utility of particular actions (Bandura Reference Bandura1977; Condon and Holleque Reference Condon and Holleque2013). Furthermore, meta-analyses (Byrnes et al. Reference Byrnes, Miller and Schafer1999; Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel and Grossman2008) confirm that in many settings women display lower risk acceptance than men, and Byrnes et al. (Reference Byrnes, Miller and Schafer1999) note that this gender difference in risk aversion tends to be largest among younger people and to diminish with age.

Where is an efficacy-cultivating approach to civic education most likely to have detectable effects on the gender gap in youth political participation? Cultivating a sense of efficacy does not provide material resources (Bleck and Michelitch Reference Bleck and Michelitch2018) or activate longer-term processes to lower legal and social barriers to women’s political participation (Brulé Reference Brulé2023; McConnaughy Reference McConnaughy2007; Teele Reference Teele2018). It also does not introduce new institutions or change the rules of the political game (Clayton Reference Clayton2015; Prillaman Reference Prillaman2023). Instead, we expect that an efficacy-boosting approach is most likely to have detectable effects in contexts that meet at least three conditions. First, there are no legal barriers to women’s participation in public life. Second, women exhibit relatively high rates of literacy, enabling them to engage with civic information. Third, although cultural norms against women’s participation may exist, they are less stringently enforced. Urban areas are likely such settings. Although urban women are by no means exempt from social constraints, the mechanisms of enforcement are likely less stringent in urban than in rural settings, and thus psychological constraints may play a relatively larger role.

Zambia

Zambia is a multiparty democracy in Southern Africa that held general elections in August 2021. Several major Zambian civil society organizations, most of whom are major providers of adult civic education,Footnote 7 sought to work together to evaluate civic education approaches among young adults. As in many developing countries today, Zambia’s population skews young: approximately 77 per cent of Zambia’s population is under the age of thirty-five (World Bank 2025). Given Zambia’s rapid rates of urbanization, our partners were also interested in digital interventions designed for urban youth, as more than 50 per cent of Zambians reside in urban or peri-urban areas (World Bank 2025).

Despite legal equality and increasing socio-economic equality between men and women,Footnote 8 Zambia has well-noted gender gaps in political participation (Center Electoral Expert Mission 2021). Consistent with Amoateng et al.’s (Reference Amoateng, Kalule-Sabiti and Heaton2014) research across sub-Saharan Africa, these gender gaps are even larger in urban areas than in rural Zambia.Footnote 9 These gaps can be seen in Appendix Figure C.1. As noted above, urban areas are also the contexts within Zambia where we expect an efficacy-promoting approach to have an effect: young women living in Zambia’s cities are more likely than young women living in rural areas to live apart from traditional institutions, to be engaged in the formal or informal labor markets, and to be less subject to severe material deprivation and stringent enforcement of gender norms around political participation (Evans Reference Evans2018; Gough et al. Reference Gough, Chigunta and Langevang2016; Musonda Reference Musonda2022). In these settings, psychological barriers are likely to be a strong component of the gender gap in political participation, at least relative to rural settings.

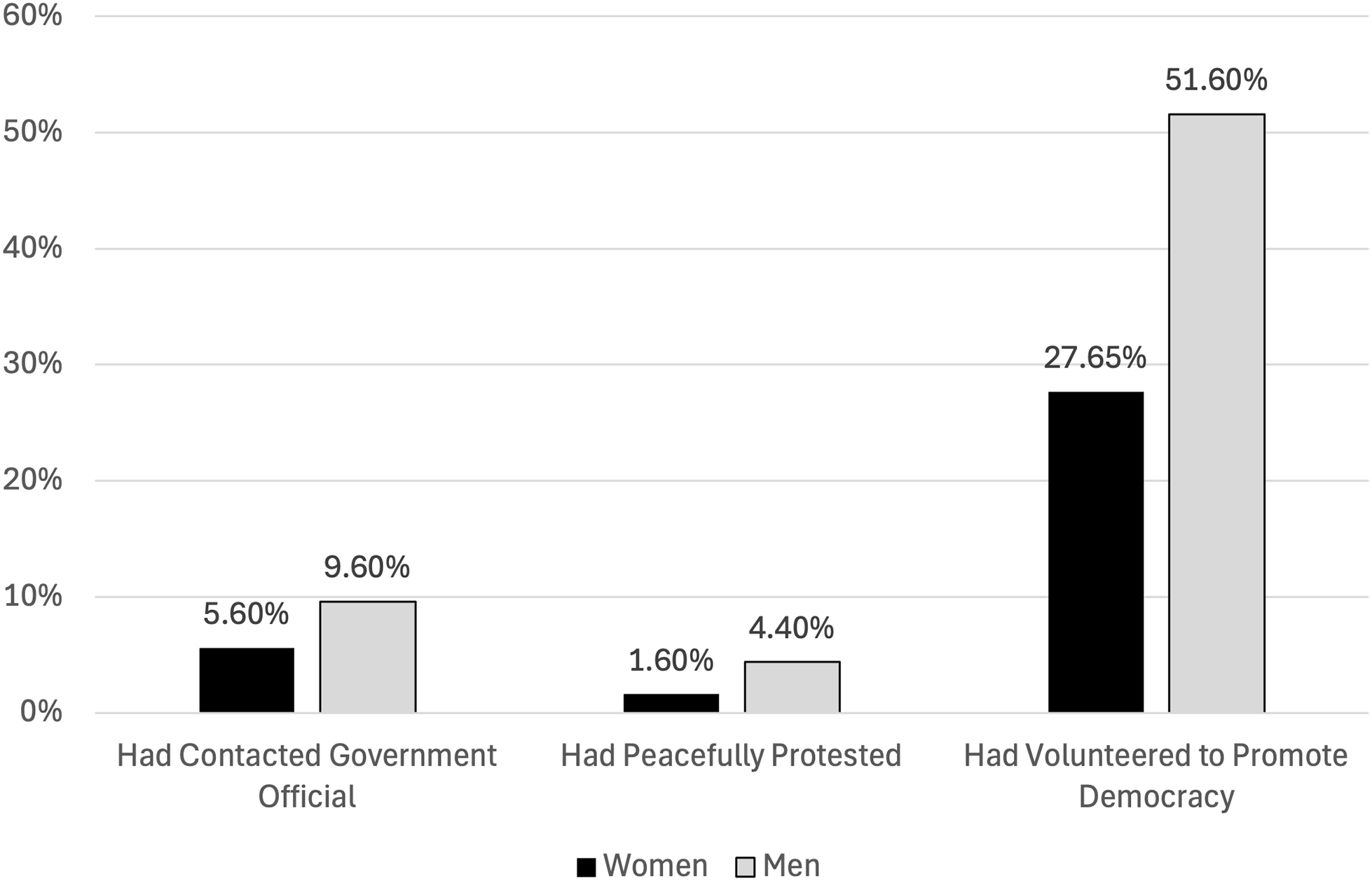

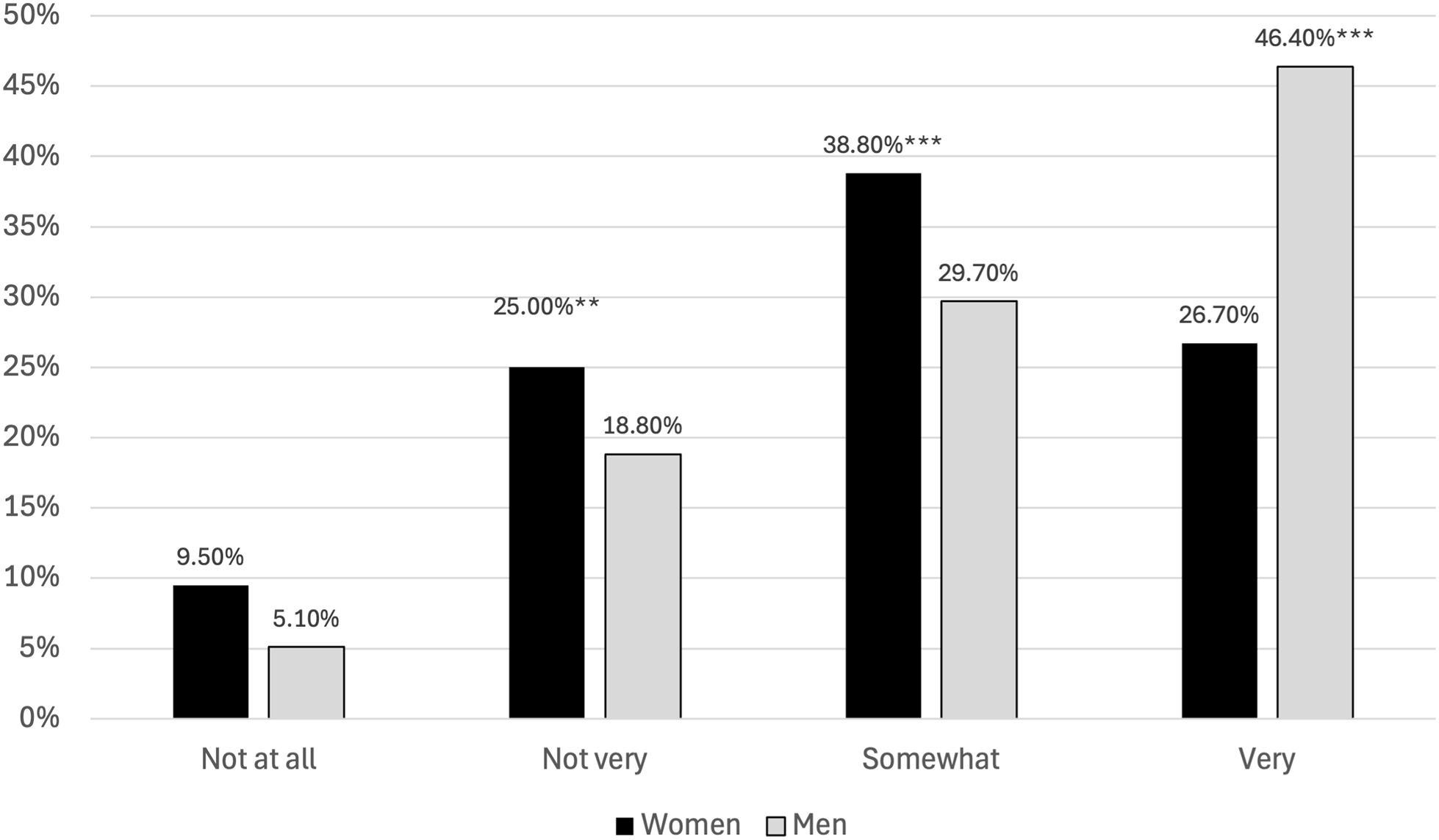

Focusing on our study sample, we observed gender gaps in several kinds of self-reported political participation. Figure 1 shows that young women in the sample were less likely to report having contacted a government official, participated in a peaceful protest, or volunteered to promote democracy at baseline. Additionally, women in our study reported fewer days of volunteering in the last month compared to men. Our study sample also exhibited significant gender differences in levels of political interest at baseline (Figure 2). When asked to indicate whether they were ‘not at all’ interested in politics, ‘not very’ interested in politics, ‘somewhat’ interested in politics, or ‘very’ interested in politics, the vast majority of young men (76 per cent) said they were very interested or somewhat interested, and close to a majority (46.4 per cent) said they were very interested. Young women’s level of political interest was markedly lower at baseline, with only 26.7 per cent reporting they were very interested in politics.

Figure 1. Baseline rates of participation by gender in study sample.

Figure 2. Baseline rates of political interest by gender in study sample.

Note: Stars in Figure 2 indicate that the difference between the share of women and the share of men in this category is statistically significant. **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Based on the nature of the context, we pre-registered the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Civic information alone might increase political knowledge and reduce the gender gap in political knowledge, but by itself, civic information would not increase political participation or reduce the gender gap in political participation.

Hypothesis 2: Exposure to a civic education course with messages intended to boost a sense of efficacy would reduce the gender gap in political participation, compared to a civic education course providing information alone.

Hypothesis 3: Exposure to a civic education course with messages intended to boost a sense of efficacy would reduce the gender gap in political participation, compared to baseline.

Experimental Design

Zambia’s 2021 general elections occurred when COVID-19 was still a major concern. Under these circumstances, we did not want to conduct in-person civic education courses. Our partners were also highly interested in digital courses, because they believed they would appeal to young people and because they would enable a wider reach than face-to-face workshops. We therefore used digital strategies for recruitment, surveys, and dissemination of course content. In Appendix Section B, we further discuss ethical considerations.

We relied on four complementary recruitment methods: (1) Posting recruitment messages on the social media pages of Zambian groups that included ‘youth’ in the group’s name; (2) Sending recruitment messages to large WhatsApp networks organized by non-partisan university groups or by our study partners; (3) Presenting a recruitment message at Zoom meetings to youth group representatives recruited by our study partners; and (4) Inviting youth group members to read the same recruitment message at their church services.Footnote 10 Interested individuals registered their desire to participate through an online survey: the survey asked for their age, the province and district (or town name) where they lived, and assessed their access to WhatsApp to confirm study eligibility. WhatsApp access is, of course, not universal, but it is concentrated among young adults. Approximately 98 per cent of the 1 million smartphone users in Zambia are eighteen to thirty-five years old, roughly half of them men and half women.Footnote 11 Interested individuals were informed that they would receive weekly data bundles to enable them to participate fully in the course, so that there were no financial barriers to participating other than having access to WhatsApp. Recruitment ultimately relied on interest in civic education, which reflects the real-world voluntary nature of adult civic education.

We targeted recruitment in the Copperbelt, Lusaka, and Southern Provinces. These three provinces ensured reliable cellular service and increased the likelihood of ethnic and partisan diversity in our sample. Study materials were offered in Bemba, English, Nyanja, and Tonga. Though the Zambian Research & Ethics review boards did not allow us to ask about party ID, Southern Province was an opposition stronghold in the previous election, and urban areas in Lusaka and Copperbelt were competitive.

The baseline phone survey was completed by 775 individuals who were then randomized into one of the two courses relevant to this paper, stratified by gender. The conditions included an information-only course and an information plus efficacy course. Both courses included identical non-partisan civic information and almost exactly the same number of infographics per lesson. Each course was two weeks long. Each week, participants in both courses received two distinct lessons, spaced several days apart. Following best practices in WhatsApp-based interventions in the region,Footnote 12 each of the four automated lessons included text and infographics, and a brief combination of multiple choice and open-ended homework questions. Participants answered the homework questions directly in WhatsApp after each of the four lessons. All messages were sent individually, rather than as part of a WhatsApp group, to protect privacy. At the start of each survey, participants were informed that the study aims for confidentiality.Footnote 13 On an infographic at the start of the course, respondents were informed, ‘This is your personal course. Read and answer the questions on your own. Your homework responses are confidential. Please answer honestly’. At the beginning of each lesson and set of homework questions, respondents were further reminded, ‘All of your responses are confidential (private).’ These messages served to reduce the chance of social desirability in answers that might have arisen had the respondents been responding in group chats. Participants with questions or technical difficulties were able to call the local research co-ordinator.

Due to resource constraints, we prioritized the comparison of the efficacy-boosting course and an information-only course over a comparison of the two courses with a pure no-civic-education control group. Since many studies have compared information-only civics courses to pure control groups, we opted to maximize statistical power for analyzing our main comparison of interest. Nevertheless, in the very first lesson, we briefly approximated a pure control. In Lesson 1, half of the respondents received only logistical information about the course, and the other respondents received only civics information, with no efficacy messages. In Lesson 2, the respondents who had received only logistical information in the first lesson then started receiving civic information and went through the rest of the program in the information-only condition. The respondents who received civics information in the first lesson continued to receive civics information and also started receiving efficacy-boosting messages in Lesson 2 and for the rest of the course. The homework questions after Lesson 1 allow us to briefly compare political knowledge and intentions to participate among individuals who were exposed to no civic information (pure control) and those exposed only to civic information (before experiencing any efficacy-boosting messages). By the end of Lesson 4, both the information-only course and the efficacy course included the same number of lessons and identical informational content.

Figure 3 shows infographics sent via WhatsApp to all participants in Lesson 1. Figure 4 then shows the civics infographics that half the participants received alongside course logistics in Lesson 1. Our partner organizations consulted on the choice of topics and the presentation of lessons to ensure that content was clearly non-partisan and contextually appropriate.

Figure 3. Logistical infographics in lesson 1, sent to all respondents.

Figure 4. Information-only infographics in lesson 1, sent to efficacy-boosting respondents.

Note: Figure 4 infographics were then also sent to info-only respondents in Lesson 2.

Figure 5 provides an example of the efficacy-boosting messages that appeared in Lessons 2–4 for participants assigned to that course. The full text of the efficacy messages is in Appendix Section A. We constructed the messages in consultation with local partners and by drawing on existing strategies to promote a sense of efficacy (Holbein and Hillygus Reference Holbein and Hillygus2020). The message in Figure 5 acknowledges challenges to political participation and encourages participants to set clear goals and make concrete plans. In other contexts, this strategy has increased individuals’ beliefs in their ability to overcome obstacles (Holbein and Hillygus Reference Holbein and Hillygus2020; Nickerson and Rogers Reference Nickerson and Rogers2010; Rogers et al. Reference Rogers, Milkman, John and Norton2015).

Figure 5. Example of efficacy message from lesson 4, sent to efficacy-boosting respondents.

In Lesson 2, we employed other tactics associated with increasing individuals’ sense of efficacy – for example, boosting a sense of collective efficacy (as part of a larger group or community) (Condon and Holleque Reference Condon and Holleque2013; Niemi et al. Reference Niemi, Craig and Mattei1991). Lesson 3 directed participants to focus on building a sense of efficacy by practicing self-affirmations (Cohen and Sherman Reference Cohen and Sherman2014). ‘Remember you have within you the capacity to be a strong citizen and to bring positive change to the world. All you need to do is believe in yourself’. The message then offers specific mantras with which the participant might reinforce their sense of efficacy (cf. Lyons et al. Reference Lyons, Farhart, Hall, Kotcher, Levendusky, Miller, Nyhan, Raimi, Reifler, Saunders, Skytte and Zhao2022): ‘So, take time each day to reminder yourself: I am whole just as I am. I am worthy. I respect myself and the potential that resides within me. I believe I can make a positive impact in my life and the lives of those around me’.

We measured attitudinal outcomes through WhatsApp homework questions and through phone-based surveys. Endline phone surveys were conducted one week after a participant concluded the course and follow-up phone surveys were conducted two weeks after that. All relevant questions are listed in Appendix Section H. The questions assessed intent to participate and judgment of others who do not participate. We also asked about a number of possible mechanisms, which we discuss below.

We measured behavioral participation in the following ways:

Volunteering: We partnered with an organization that offers volunteer opportunities for helping with election monitoring and parallel vote counting, the Christian Churches Monitoring Group (CCMG). In a homework question during the course, we asked participants if they would be willing to supply their contact information to that organization in order to be informed about volunteering opportunities during the election. Those on CCMG’s listserv then received invitations in the lead up to the election to train to become election monitors (open to any participant) and to train and volunteer to help with data compilation from the parallel vote tally (open to Lusaka residents). A liaison at the partner organization provided information on who took up these opportunities.

Social Media: In a homework question at the end of the course, we asked participants to share their social media handles for us to follow, providing an indicator of willingness to engage in public political participation. (About 29 per cent did share.) We then collected Twitter posts from 1 June through 12 August and coded them for mentions of political participation. We encountered challenges in working with CrowdTangle, so for Facebook handles, we hand-coded whether they used popular election hashtags in Zambia (#YouthVote2021, #ZambiaDecides, #CanYouRemember), or mentioned voting or other political actions, during the two months before the elections.

Donations: We gave study participants an opportunity to donate some of the follow-up phone survey compensation (up to 20 kwacha) to CCMG to promote free and fair elections. They answered whether they wanted to do so in the follow-up phone survey. (They received an additional 20 kwacha for participation in the survey that they could not donate, guaranteeing decent compensation regardless of whether they donated or not.)

Retrospective Questions: Finally, in the days after the election took place, we sent out a final WhatsApp survey in which we asked course participants a range of questions about their participation during the election: whether they voted (with a verification question about the color of the lid for the ballot box for Presidential votes), helped others vote, attended a rally, volunteered to promote free and fair elections, and discussed politics.

Appendix Table E.2 considers evidence of balance on observables across courses. Given slight imbalances on some variables by chance, we follow our pre-registration plan and present results with demographic controls. Appendix Tables F.2, F.4, F.6, and F.8 show the results are consistent without including controls. Appendix Tables F.1, F.3, F.5, and F.7 show full results, including coefficients on covariates.

Results

High Engagement with the Courses and Limited Attrition

Engagement with the courses was high and did not differ by course type. Figure D.2 in the Appendix graphs lesson completion. Eighty-seven per cent of respondents responded ‘yes’ to seeing the infographics in all four lessons and engaged with homework questions in all four lessons. This rate of engagement did not differ across courses. Everyone in both courses engaged with at least one of the four lessons. Five of the homework questions were open-ended. If we add the number of words written by each respondent across all five open-ended questions, respondents wrote between 5 and 372 words in total, one possible indicator of the range of engagement with the course material. On average, the respondents assigned to the information-only course wrote a total of seventy-six words, and the respondents assigned to the efficacy course wrote eighty-two words, a difference that is only marginally statistically significant.

Attrition was low (Appendix Figure D.3). From baseline to the first phone survey conducted after course completion, attrition from these two conditions was 3.0 per cent and did not differ across them. Attrition from baseline to the follow-up phone survey (conducted three weeks after course completion) was only 5.0 per cent from these two conditions and was also consistent across them. Although more than two months elapsed between the baseline survey and the election, attrition from baseline to the very last survey (the post-election survey) was only 9.2 per cent across these two conditions, well below our pre-registered expectation of 25 per cent. In the post-election survey, attrition rates differed somewhat between the information-only course and the efficacy course. As we pre-registered, we assessed the demographic correlates of attrition generally (Appendix Table D.1), and the correlates of differential attrition (see, for example, Appendix Table D.2). Gender is not associated with overall attrition rates in the final survey, but men are slightly more likely to exhibit differential attrition (higher attrition from the efficacy course relative to the info-only course) in the final survey. Below, we adjust for differential attrition only when analyzing outcomes from the very last survey, because there was no differential attrition in the homework, endline, or follow-up surveys.

Main Treatment Effects

As pre-specified, we estimate intent-to-treat effects either of the civic-information-only lesson (Lesson 1), with the logistics-only lesson (Lesson 1) as the reference category, or of the efficacy course, with the information-only course as the reference category, on measures of intent to participate and of actual participation.

The basic specification for these intent-to-treat estimations is:

where T 1 refers to assignment either to the civics-information-only lesson (in which specifications the logistics-only lesson is the reference category) or to the efficacy course (in which specifications the information-only courses is the reference category). Y i refers to the relevant attitudinal or behavioral outcome, measured at the respondent (i) level. α represents the mean outcome for those in the reference category. X i is a vector of pre-treatment covariates (age, whether achieved secondary education, whether mother achieved secondary education, never married, whether has children, province, language survey taken in, whether has church leader position, whether attends church more than once a week, Pentecostal, and indicators for whether the respondent signed up for the study in weeks 1, 2, or 3 of recruitment). In all cases, we calculate estimates using robust standard errors. Regression results omitting controls are presented in Appendix F.

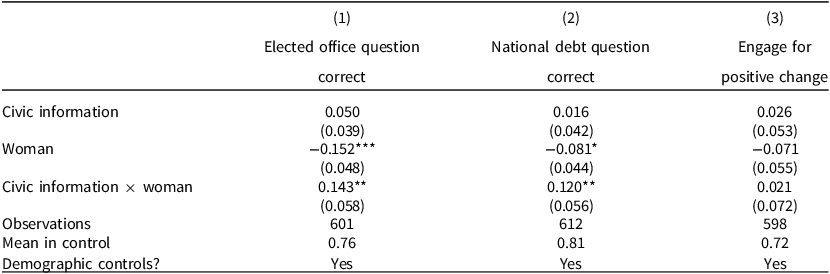

Table 1 shows the treatment effects of civic information versus only logistical course information on political knowledge and intent-to-participate after Lesson 1, by gender. As the first two columns of Table 1 show, civic information alone had a positive effect on political knowledge among women, and a compensatory effect on the gender gap in political knowledge: women learned more from the civic information treatment than men did, thereby closing the political knowledge gap. However, as shown in column 3, the civic information treatment did not have a compensatory effect on an attitude about engaging in politics. The size of the gender gap in that attitude was similar to the gap in knowledge on the second factual political knowledge question, but there was no substantively significant or statistically significant effect of civic information on this attitude towards political participation among men or women.

Table 1. Influence of civic information only, relative to logistical information (first lesson), on political knowledge, by gender

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. The reference experimental condition in these regressions is course logistics information only (no civics information). The first question (column 1) read, ‘Which of the following are going to be chosen through elections this August? You can text back as many options as you think apply. 1. President, 2. Provincial Ministers, 3. Ward Councillors, 4. Mayors, 5. Members of Parliament’. The second question (column 2) read, ‘To your knowledge, has Zambia’s national debt gone up or down in recent years? 1. It has gone down recently, 2. It has gone up recently, 3. I don’t know’. The third question (column 3) read, ’In your view, do you believe that regular Zambian people can help make positive change in this country by voting in national elections? Text the number of your response back. 1. Yes, voting can make a difference, 2. Voting can make a difference sometimes, but not in every election, 3. No, voting rarely makes a difference’ (coded as 1 if said 1, zero otherwise). Null results are even starker if coded as 1 if the respondent said 1 or 2, zero if said 3. Controls include age, secondary education, mother’s secondary education, never married, children, province, survey language, holding a church leader position, frequent church attendance, and Pentecostal affiliation. Full results with covariate coefficients in Table F.1. Results without controls in Table F.2.

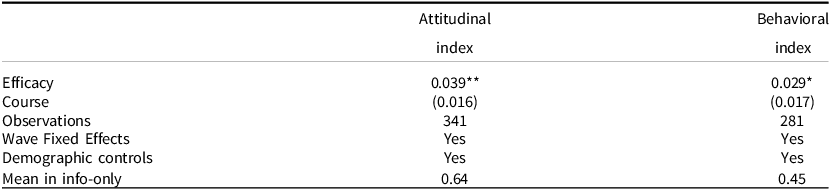

Table 2 shows treatment effects of the efficacy course on intent-to-participate and actual participation among women, relative to the information-only course. Among women, we observe a positive effect of the efficacy course compared to the information-only course, both on an additive index of intent-to-participate measures and on an additive index of reported and actual participation measures.Footnote 14 The efficacy course increased women’s intent to participate and actual participation by 3 to 4 percentage points, a magnitude comparable to the effect of many get-out-the-vote (GOTV) strategies used in the United States (Green and Gerber Reference Green and Gerber2019).

Table 2. Estimates of treatment effects of efficacy course on political participation, among women

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05. The reference experimental condition in these regressions is the civic information-only course. Demographic controls include gender, age, post-secondary education, mother’s post-secondary education, never married, has children, province, survey language, church leader, frequent church attendance, and Pentecostal affiliation. The attitudinal index is an additive index normalized to 0–1 that includes the following endline attitudes : (1) ‘There are various actions that people sometimes take as citizens. We are interested in whether you have done these things recently or would do these things if offered the opportunity in the near future. For instance, if elections were held tomorrow, would you vote? (Or if you are not registered but had the opportunity to register tomorrow, would you register?)’ (2) ‘Would you attend a peaceful protest or demonstration march?’ (3) ‘Would you contact a government official to ask for help with a problem or to raise an issue?’ (4) ‘Would you attend a protest where violence by political cadres was likely to break out?’ (reverse coded), (5) ‘Please imagine you have a friend who refuses an opportunity to learn more about politics and political participation because they believe ‘all politicians are corrupt’. Do you think that refusing to learn more about or engage in politics makes this friend a bad citizen?’ (coded as 1 if a respondent answered yes and zero otherwise), and (6) ‘Some people volunteer regularly or from time to time. This means doing unpaid work in the community …Have you volunteered at any point in the last five years?’ Results are robust whether or not the violent protest question is reverse coded. Results are also robust to dropping the volunteer question, which asks about a past time period. The behavioral index is an additive index normalized to 0–1 that includes the following actions: donating (or not), signing up for the volunteer listserv (or not), posting on social media (or not), and indicators for ‘yes’ to each of the six action questions in the post-election survey. Full results with covariate coefficients in Table F.3. Results without controls in Table F.4.

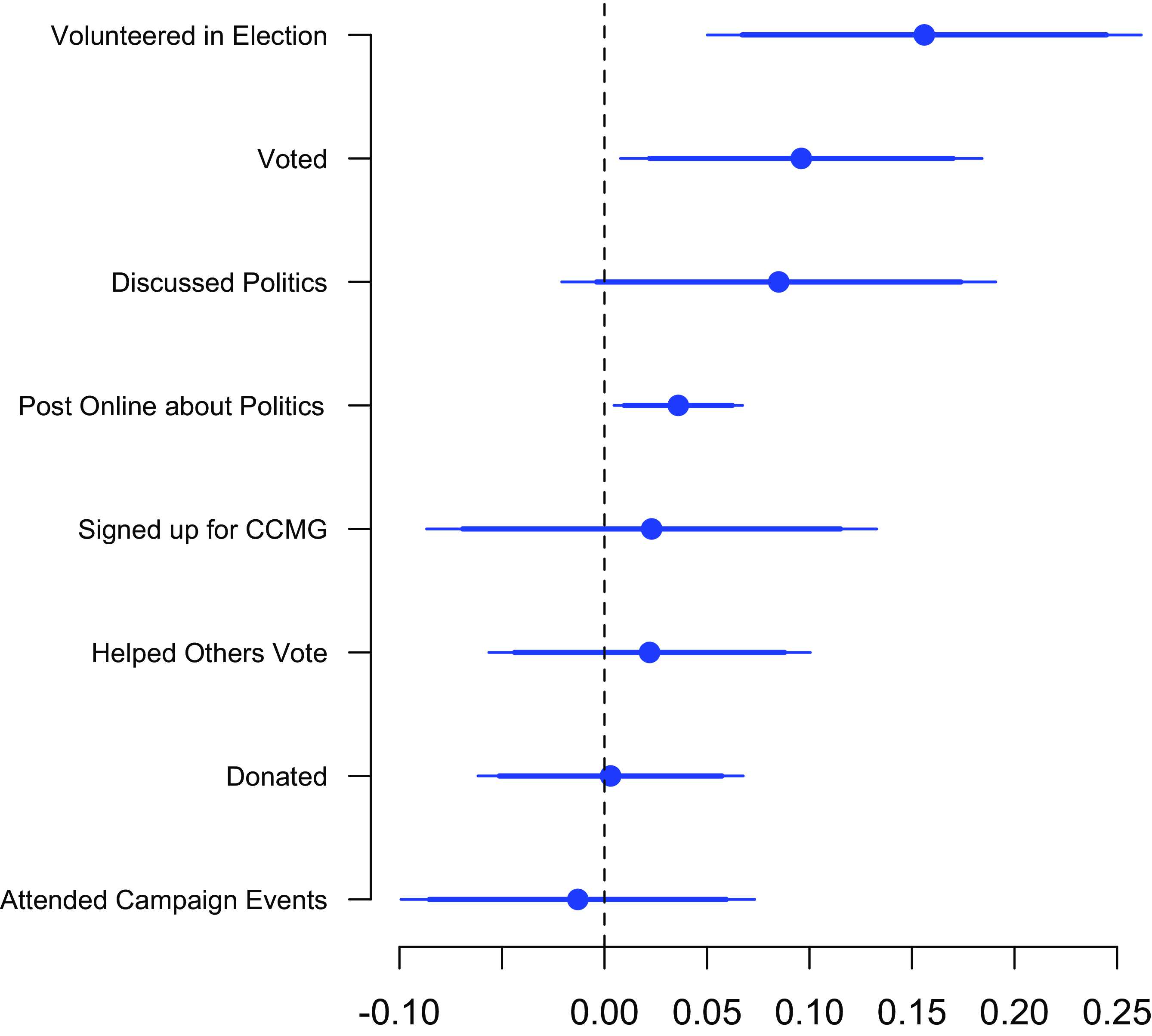

Figure 6 shows the estimated treatment effects of the efficacy course among women on individual actions, ordered by the size of the point estimates. The actions shown are those in the behavioral index. The positive effect of the efficacy course, compared to the information-only course, on women’s behavioral participation is driven by: a boost in volunteering during the election, a boost in voting, a boost in posting on social media about political actions, and, weakly, a boost in discussing politics with others during the election.Footnote 15 Notably, these measures represent a mix of more formal (voting) and less formal (volunteering, discussing, posting on social media) types of political behavior (M’Cormack-Hale Reference M’Cormack-Hale2015). Volunteering in this case is to promote a free and fair election, which is substantively important for sustaining democracy. Although the treatment effect on political discussion is less statistically robust than the treatment effects on other forms of political participation, it is substantively very similar to the treatment effects on volunteering and voting.

Figure 6. Effect of the efficacy course on behaviors, women only.

Note: Point estimates represent the effect of the efficacy course relative to the information-only course among women. Bars around point estimates depict 90 per cent (thick line) and 95 per cent (thin line) confidence intervals.

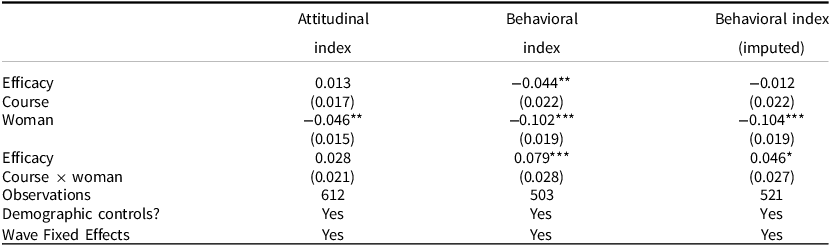

Table 3 then shows the treatment effects of the courses interacted with gender, so that we can see whether this increase in participation among women after the efficacy course is matched by a similar increase in men’s intention to participate or actual participation. Recall that there was no differential attrition across courses in surveys measuring intent-to-participate (attitudinal outcomes). As column 1 shows, there is a clear gender gap in intention to participate in the information-only course (row 2, column 1). The efficacy course has no statistically (or substantively) significant effect on the attitudinal index among men (row 1, column 1), but it has a positive (though not quite statistically significant) effect on the attitudinal index among women (row 3, column 1), closing the ex ante gender gap.

Table 3. Compensatory effects on participation, by gender

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. The reference experimental condition in these regressions is the civic information-only course. Demographic controls include gender, age, post-secondary education, mother’s post-secondary education, never married, has children, province, survey language, church leader, frequent church attendance, and Pentecostal affiliation. The attitudinal index is an additive index normalized to 0–1 that includes the following actions: (1) ‘There are various actions that people sometimes take as citizens. We are interested in whether you have done these things recently or would do these things if offered the opportunity in the near future. For instance, if elections were held tomorrow, would you vote? (Or if you are not registered but had the opportunity to register tomorrow, would you register?)’ (2) ‘Would you attend a peaceful protest or demonstration march?’ (3) ‘Would you contact a government official to ask for help with a problem or to raise an issue?’ (4) ‘Would you attend a protest where violence by political cadres was likely to break out?’ (reverse coded), (5) ‘Please imagine you have a friend who refuses an opportunity to learn more about politics and political participation because they believe ‘all politicians are corrupt’. Do you think that refusing to learn more about or engage in politics makes this friend a bad citizen?’ (coded as 1 if a respondent answered yes and zero otherwise), and (6) ‘Some people volunteer regularly or from time to time. This means doing unpaid work in the community …Have you volunteered at any point in the last five years?’ Results are robust whether or not the violent protest question is reverse coded. Results are also robust to dropping the volunteer question, which asks about a past time period. The behavioral index is an additive index normalized to 0–1 that includes the following actions: donating (or not), signing up for the volunteer listserv (or not), posting on social media (or not), and indicators for ‘yes’ to each of the six action questions in the post-election survey. Full results with covariate coefficients in Table F.5. Results without controls in Table F.6.

As columns 2 and 3 show, the reduction in the gender gap is clearer when we examine actual participation. Column 2 shows the results with no accounting for attrition. Column 3 then imputes full behavioral participation for men who attrited from the very last survey and who were assigned to the efficacy course. Recall that men attrited from the very last survey at a slightly higher rate if they had been assigned to the efficacy course than if they had been assigned to the information-only course. If all those male attriters actually participated at high rates, we might mistakenly infer that the efficacy course reduced the gender gap only because we did not observe men’s high rates of participation. Column 3 suggests that is not the case. In column 3, we assume that all the men in the efficacy course who attrited from the final survey actually participated in every form of reported participation measured in the post-election survey. This is a strong assumption. On average, respondents participated in 49 per cent of the activities, and no one reported participating in every single activity. Nevertheless, even when we make this assumption, we find that the efficacy course still had a more positive effect on women’s participation than on men’s participation. The estimates in column 3 indicate that the efficacy course had a negligible effect on men’s participation while increasing women’s participation by 4.6 percentage points.

We note that the efficacy course seems to have more of an impact on actual behavior than on intent-to-participate. This pattern is consistent with the findings and argument in Holbein and Hillygus (Reference Holbein and Hillygus2020) in the United States. Those authors point out that intentions to participate tend to be over-reported – that is, many people who report intentions to participate do not actually do so. A sense of efficacy, they theorize, matters for actual political participation because it changes people’s willingness to follow through on their intentions.

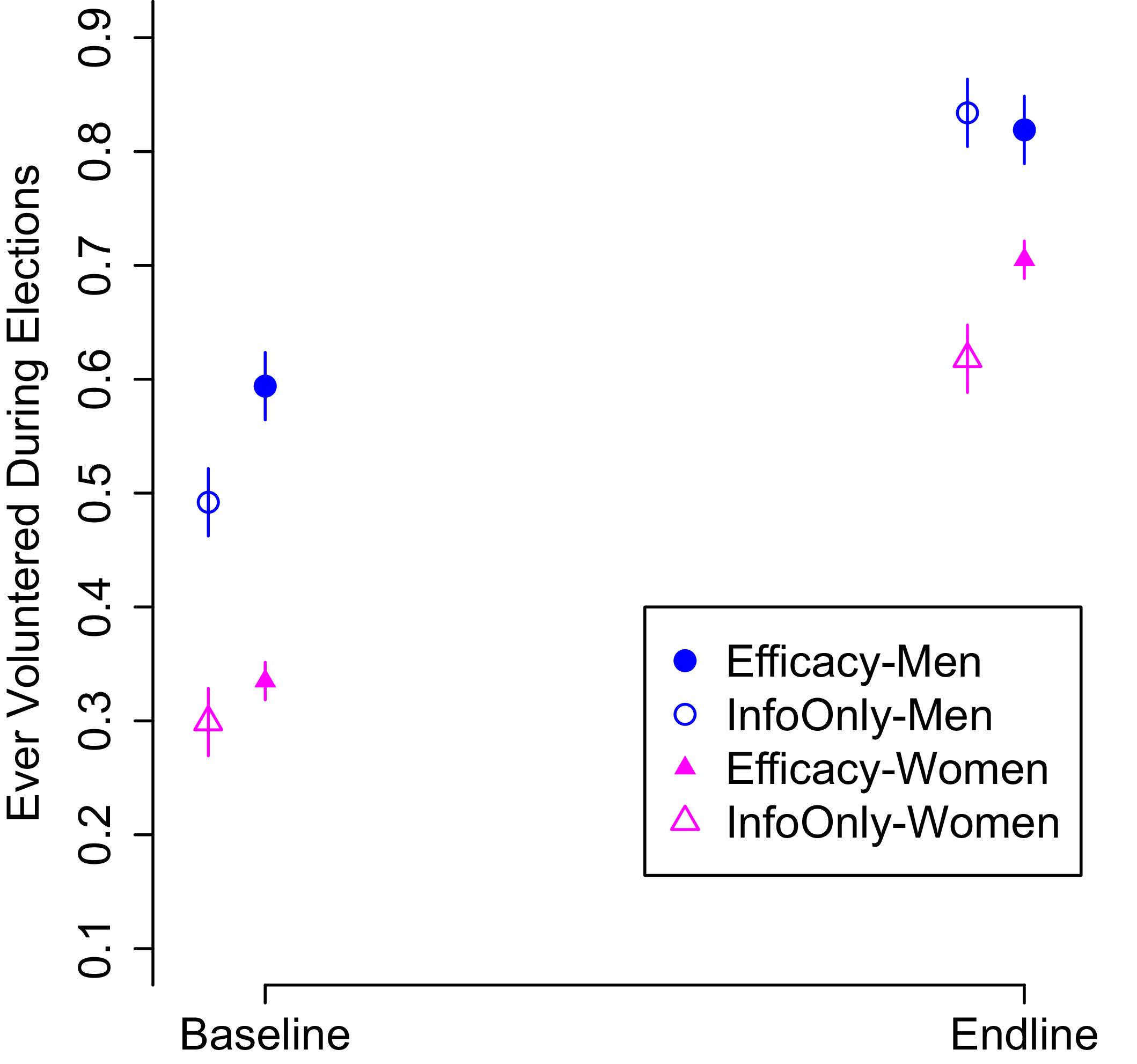

Figure 7 then illustrates the compensatory effects of the efficacy course vis-à-vis baseline. Shown here is the share of respondents who said they have volunteered to promote democracy or free and fair elections. In the baseline survey, respondents were asked, ‘Have you ever volunteered to promote democracy or fair elections? Some examples might include helping to register people to vote, educating people about democracy or voting, serving as an election observer with an organization like the Christian Churches Monitoring Group. Have you done this kind of volunteer work in the last five years?’ The gender gap at baseline in ‘yes’ responses to this question is 20–25 percentage points, or about 66–83 per cent of women’s baseline levels of participation, among people assigned to both conditions. In the post-election survey, the shares of people who said yes to this same question go up across the board, which makes sense because respondents in all conditions were offered opportunities to volunteer with CCMG during the elections. However, the gender gap shrinks only among participants in the efficacy course. In the information-only condition, the gender gap in volunteering remains about 20 percentage points; in the efficacy course, the gender gap shrinks to 11 percentage points. Although mentioning CCMG during the baseline survey could have increased women’s yes responses to the volunteering question at endline, it would have done so equally across the efficacy and information-only course conditions. The differential reduction in the gender gap relative to baseline can be due only to the messaging differences between the two course conditions.

Figure 7. Political volunteering at baseline and endline, by course type and gender.

In Appendix Table G.9, we show which results hold following the application of our pre-registered strategy of multiple comparison corrections. We pre-registered that we would apply Benjamini and Hochberg (Reference Benjamini and Hochberg1995) corrections to tests of the same pre-registered hypothesis with multiple measures of the same dependent variable, with an index counting as one measure. The findings that hold at the 0.05 level, even when multiple comparison corrections are applied, are: (1) that the efficacy course increased intentions to participate among women relative to the information-only course, (2) that the efficacy course reduced the gender gap in actual political participation relative to the information-only course, (3) that the civic-information-only treatment in Lesson 1 increased political knowledge relative to the logistics-only treatment among women and reduced the gender gap in political knowledge.Footnote 16 In our pre-analysis plan, we pre-registered specifically that the effects of the efficacy-boosting course would be ‘larger among women than among men’.Footnote 17 This pre-registered hypothesis survives multiple-comparison corrections when it comes to actual political participation, which is arguably a more politically consequential domain than intentions to participate.

Mechanisms

In this section, we explore possible mechanisms for the main findings. We pre-registered that the efficacy course would increase intended and actual political participation more for women than for men, but we did not pre-specify the mechanisms that might underpin those results. Thus, the following section should be treated as exploratory.

In our earlier discussion of theories connecting efficacy to political participation, we described several ways that efficacy might increase political participation. A sense of efficacy might increase political participation by enhancing internal political efficacy (Bandura Reference Bandura1977; Niemi et al. Reference Niemi, Craig and Mattei1991). A sense of efficacy might increase young women’s interest in politics (Wolak Reference Wolak2020; Preece Reference Preece2016). Or a sense of efficacy might make politics more exciting or anger-inducing for young women (Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Gregorowicz and Groenendyk2009; Young Reference Young2020), thus lowering their risk aversion (Young Reference Young2020), which tends to increase political participation (Kam Reference Kam2012).

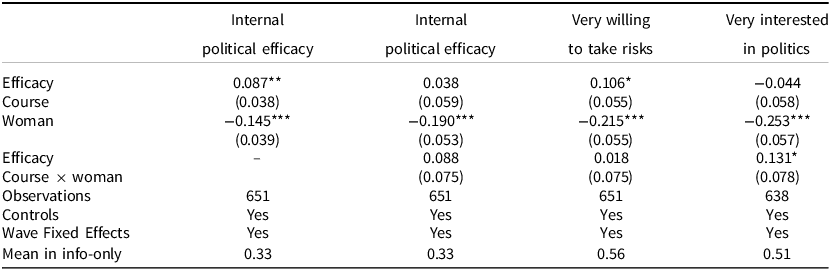

Table 4 explores the effects of the efficacy course on these intermediate variables: internal political efficacy, risk acceptance, and interest in politics. The first column shows that the efficacy course did indeed increase a sense of internal political efficacy, compared to the information-only course. However, in column 2, we cannot say with certainty that the efficacy course increased a sense of internal political efficacy more for women than for men. In column 3, one can further see that the course increased risk acceptance for both men and women.Footnote 18 The coefficient on the interaction term in column 3 is both small and statistically insignificant, indicating that there is no detectable gender heterogeneity in the treatment effect on risk acceptance. However, in column 4, we see that the efficacy course clearly and significantly increased political interest more among women than among men. The rate of women saying they are ‘very interested in politics’ increased by about 13 percentage points after the efficacy course, reducing a 25.3 percentage point gender gap in strong interest in the information-only condition.

Table 4. Treatment effects on internal efficacy, risk-taking, and political interest, by gender

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. The reference experimental condition in these regressions is the civic information-only course. Demographic controls include gender, age, post-secondary education, mother’s post-secondary education, never married, has children, province, survey language, church leader, frequent church attendance, and Pentecostal affiliation. Full results with covariate coefficients in Table F.7; results without controls in Table F.8.

To further explore these mechanisms, we conducted mediation analyses, the results of which are in Table G.1. These analyses were not pre-registered and are also exploratory. Following standard potential outcomes approaches (Bullock and Ha Reference Bullock and Ha2011; Imai et al. Reference Imai, Keele, Tingley and Yamamoto2010), we decomposed total treatment effects into direct and indirect components. This method relies on strong, untestable assumptions, particularly that there are no unobserved confounders between the mediator and the outcome. Even if we were to control for all observables, this would be a strong and untestable assumption. Table G.1 shows models without controls, and we interpret the results as suggestive. The results are consistent with the political interest mechanisms and, to some extent, with the risk acceptance mechanism. Among women, we find a statistically significant indirect effect on political participation for both risk acceptance and political interest (Table G.1). Only for women is the effect of the efficacy course on political participation mediated by political interest (column 2). We do not observe a corresponding indirect effect through political interest among men (column 4). Risk acceptance robustly mediates the relationship between the efficacy course and political participation for women (column 1) but does not do so robustly for men (column 3). In fact, when imputing for male attriters, we do not find any significant natural indirect effect through risk acceptance among men (Table G.8).

We examined several alternative mechanisms as well, specifically, whether the efficacy course affected emotions, or, apart from the mechanisms we described earlier in the paper, whether the efficacy course might have primed different kinds of identities or expectations about others’ participation. We find little support for these alternative mechanisms, as we show in Tables G.2–G.3. The fact that the efficacy course had little impact on expectations about others’ behavior further underscores that the intervention targeted individual psychological resources rather than shifting gender norms or social dynamics. We also examined several different robustness questions, including whether other demographic attributes that are correlated with gender instead explain the effects and whether the results are due to ceiling effects or reversion to the mean. Our results are robust to these possibilities, as shown in Appendix Section G.

In an open-ended homework question at the end of the course, we asked study participants to describe ‘one thing from this course you’ve learned so far that you had not known before’. A young women wrote the following:

This course has given me the courage to believe in myself and the strength of achieving my goals and so helped me to develop [an] interest in politics which I never did before.

This quote summarizes much of what this study has found: young women may need a boost in their sense of efficacy before developing an active interest in politics and participating in politics.

Conclusion

In this study, we examined the consequences of an efficacy-promoting civic education course on gender gaps in youth political participation. Through a community-collaborative field experiment in Zambia, we found that the efficacy course reduced the gender gap by increasing young women’s political participation more than young men’s. Studying these phenomena among young voting-age adults (18–35 years old) is important because in many developing countries, young people make up more than a majority of the population (YouthMap 2014) and because many political attitudes are formed in early adulthood (Dassonneville and McAllister Reference Dassonneville and McAllister2018; Fraile and Sánchez-Vítores Reference Fraile and Sánchez-Vítores2020).

Would this type of civic education help reduce the gender gap across all contexts? Zambia is a context in which, like in many parts of the world, gender socialization around politics occurs but where legal prohibitions against women’s empowerment are absent and women are increasingly catching up with men economically. In urban areas, where communal ties are often less robust, women may not face extremely stringent enforcement of gender norms around politics. We do not expect that the efficacy course would have had as large an effect in places where legal, social, and economic barriers to women’s participation are extremely high (see, for example, Bleck and Michelitch Reference Bleck and Michelitch2018; Cheema et al. Reference Cheema, Khan, Liaqat and Mohmand2023; McConnaughy Reference McConnaughy2013). However, we expect that efficacy courses like ours could, by themselves, reduce gender gaps in participation in places where gender gaps are heavily driven by a lack of psychological and informational resources. Examples of places where efficacy courses might have important effects include urban areas in relatively democratic countries, developing or developed, for example in Sub-Saharan Africa, Europe, Latin America, and so on.

Of course, as with any approach, there are limitations that future research should explore. The approach does not challenge gender norms directly and therefore may not lead to longer-term unraveling of gendered political socialization. On the other hand, as increased women’s political participation changes descriptive norms about women’s political presence, prescriptive norms might gradually shift over time, too (cf. Foos and Gilardi Reference Foos and Gilardi2020). It is an empirical question. The courses in this study were also delivered individually rather than through groups. Future research could compare the influence of individually delivered messages with the influence of women-only discussion groups that promote a sense of efficacy in politics (Karpowitz and Mendelberg Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2018; Wilke et al. Reference Wilke, Anaduaka, Hofstetter and Yu2024). The courses in this study were delivered by smartphone. On the one hand, many urban Zambians (young men and women) own smartphones, and digital platforms are likely to become even more important in the future. On the other hand, future research might explore the generalizability of the findings to non-digital settings. Finally, recruitment into our study was on a voluntary basis, which means we likely attracted young men and women who were somewhat more interested in a civic education course than the general population. Most adult civic education programs are voluntary, so our study is assessing treatment effects on the likely-to-be-treated. However, future research could further explore whether our findings extend to mandatory curricula.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712342510121X.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DBNFYU.

Acknowledgments

We thank our partner organizations, especially Caritas-Zambia, the Council of Churches in Zambia, the Christian Churches Monitoring Group in Zambia, and IPA-Zambia for their work on this project. At these organizations, we are particularly grateful to Eugene Kabilika, Rev. Emmanuel Chikoya, Tamara Billima, and Daniele Barro. Lughano Kabaghe and Alexis Palmer provided superb research assistance. We are grateful to participants in seminars at the University of New Mexico, Harvard University, and the Center for Democratic Politics at Princeton University, as well as at the Annual Meeting of the African Studies Association and at the 2024 and 2025 Meetings of the American Political Science Association, for helpful feedback, especially to Tiffany Barnes, Ryan Enos, Tanushree Goyal, Kimuli Kasara, Natalie Letsa, Lauren MacLean, Tali Mendelberg, Corinne McConnaughy, and Sun Young Park, and to three anonymous reviewers.

Financial support

This work was supported by generous funding from the Global Religion Research Initiative (GRRI) at the University of Notre Dame, A ‘Building Evidence on Citizen Engagement and Government Accountability’ grant from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Gov-Lab, as well as by the University of Denver (DU) and New York University (NYU).

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Zambia, the National Health Research Authority in Zambia, and by the Institutional Review Boards at Denver University and New York University.