Introduction

Intimate relationships can offer profound emotional fulfilment; however, it is equally evident that they can become a significant source of distress (Glabe & Gosnell, Reference Gable and Gosnell2013). In this context, deciding whether to continue or leave a relationship is among the most challenging choices individuals may face (Garrido-Macías et al., Reference Garrido-Macías, Valor-Segura and Expósito2017), particularly when the relationship implies intimate partner violence (IPV; Badenes-Sastre et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Medinilla-Tena, Spencer and Expósito2025). In this regard, approximately 30% of women worldwide have experienced IPV during their lifetime, which represents a violation of women’s human rights and constitutes one of the most common forms of violence against women (WHO, 2024). In its most extreme form, IPV results in death of women and girls: an estimated 85,000 feminicides were recorded globally in 2023, with Africa, the Americas, and Oceania being the regions with highest rates of feminicides committed by partners. In Latin America and the Caribbean, a woman is killed every 2 hours due to IPV (UN Women & UNODC, 2024). Women’s exposure to IPV—that is, to behaviors involving physical, sexual, psychological violence, or controlling behaviors by their male partner or former partner—carries serious consequences for their physical and mental health as well as their well-being (Wang, Reference Wang2016; World Health Organization [WHO], 2024).

In this sense, prioritizing decision-making for women’s well-being and safety is crucial, as in situations of violence, women are at risk of harm, and leaving the relationship may be an appropriate response (Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas and Expósito2023). However, leaving an intimate relationship is not an easy decision. Women may encounter numerous sociocultural and individual obstacles in terminating a violent relationship, such as cultural beliefs, relational roles, dependency, and cognitive distortions, among others (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Herrero et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas and Expósito2023; Barrios et al., Reference Barrios, Khaw, Bermea and Hardesty2021; Costanza Baldry & Cinquegrana, Reference Costanza Baldry and Cinquegrana2020; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Arriaga and Agnew2017; Valor‐Segura et al., Reference Valor‐Segura, Expósito, Moya and Kluwer2014; Valor-Segura et al., Reference Valor-Segura, Lozano and Garrido-Macías2020). Thus, we explored the role of various ideological (traditional female role), relational (dependency), and individual (cognitive distortions) variables in women’s decision-making in situations of violence, differentiating between those who are currently experiencing IPV and those who are not.

Traditional Female Role and Dependency

Gender roles are social constructs that shape behaviors, activities, expectations, and opportunities deemed appropriate for men and women in a specific sociocultural context, establishing conditions of power inequality that disadvantage women (WHO, 2018). For example, women are expected to act according to more communal dimensions (i.e., femininity: empathic, emotional, and dependent) that would imply maintaining the intimate relationship (Abele & Wojciszke, Reference Abele and Wojciszke2014; Villanueva-Moya & Expósito, Reference Villanueva-Moya and Expósito2020). In this regard, it appears that women tend to adhere more closely to gender roles than men, engaging in behaviors consistent with societal expectations due to fear of the negative consequences of not following socially established gender mandates (Villanueva-Moya & Expósito, Reference Villanueva-Moya and Expósito2020).

In the context of violent relationships, women’s adherence to traditional gender roles may increase the likelihood of remaining in these relationships (Amor & Echeburúa, Reference Amor and Echeburúa2010; González & Rodríguez-Planas, Reference González and Rodríguez-Planas2020; Rhatigan et al., Reference Rhatigan, Street and Axsom2006). Likewise, the assumption of gender roles has been related to greater acceptance of IPV and less perceived severity of IPV (Martín-Fernández et al., Reference Martín-Fernández, Gracia and Lila2018; Sánchez-Hernández et al., Reference Sánchez-Hernández, Herrera-Enríquez and Expósito2020). Women’s beliefs about the traditional female role can impact their psychological well-being and social performance (Rovira et al., Reference Rovira, Lega, Suso-Ribera and Orue2020), which may indirectly influence their decision-making in relationships.

Otherwise, dependency has been linked to women’s decision to remain in a violent relationship (Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas and Expósito2023; Le et al., Reference Le, Dove, Agnew, Korn and Mutso2010; Valor-Segura et al., Reference Valor‐Segura, Expósito, Moya and Kluwer2014). It refers to the dynamics of bonding with a partner, encompassing thoughts, behaviors, and emotions driven by the need for interaction and affirmation (Valor-Segura et al., Reference Valor-Segura, Expósito and Moya2009). Women who experience IPV typically exhibit higher levels of dependency on their partner, which makes it more difficult to break free from the abusive relationship (Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas and Expósito2023; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Arriaga and Agnew2017). Similarly, high levels of dependency were associated with lower perceived severity of IPV and assessed risk for women’s lives (Badenes-Sastre et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas, Lorente and Expósito2024). Both variables, traditional female roles and dependency, could moderate women’s interpretation of IPV, making it essential to examine their influence in this study.

Decision-Making in Violent Relationships and Cognitive Distortions

According to Rusbult et al. (Reference Rusbult, Morrow and Johnson1987), intimate partners can use different strategies to resolve conflicts, which may either support the maintenance of the relationship (i.e., voice or loyalty) or contribute to its deterioration (i.e., exit or neglect; Rusbult & Zembrodt, Reference Rusbult and Zembrodt1983). Specifically, exit implies active strategies to break a relationship, whereas loyalty involves passive strategies in which the situation is expected to change by itself (Rusbult et al., Reference Rusbult, Morrow and Johnson1987). Although exit strategies can be disruptive to relationships, they can serve as an effective response for women in cases of IPV, protecting them from the risks that IPV pose to their health (Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas and Expósito2023; Rusbult et al., Reference Rusbult, Morrow and Johnson1987). Otherwise, loyalty strategies encourage women to remain in the relationship, hoping for change, defending their partner when criticized by others, and praying for improvement, among others (Rusbult et al., Reference Rusbult, Morrow and Johnson1987). The use of loyalty strategies by women involved in violent relationships can have devastating consequences due to the fact that exposure to IPV negatively impacts both physical health (e.g., injuries, headaches) and mental health (e.g., anxiety, depression) and may even result in death (WHO, 2024).

In this regard, the presence of cognitive distortions could be an important obstacle to women’s decision-making about staying in (loyalty strategy) or leaving (exit strategy) relationships (Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas and Expósito2023; Heim et al., Reference Heim, Trujillo Tapia and Quintanilla Gonzáles2018; Nicholson & Lutz, Reference Nicholson and Lutz2017). Festinger’s (Reference Festinger1975) theory of cognitive dissonance describes the uncomfortable tension that arises when individuals hold two conflicting thoughts simultaneously or engage in behaviors that conflict with deeply held beliefs. This internal discomfort often prompts efforts to reduce the tension, such as altering one’s thoughts. These adjustments can, in turn, lead to the development of maladaptive cognitive distortions as a means of resolving the dissonance (Mattia et al., Reference Mattia, Di Leo and Principato2021). In general, this distorted reasoning can appear in anyone; however, the content and function of cognitive distortions vary according to the context, especially the sociocultural one (Lega & Ellis, Reference Lega and Ellis2001).

In cases of IPV, women may exhibit cognitive distortions to reduce dissonance, such as exonerating to the aggressor, minimizing, or denying the violence, and continue their relationship (Amor & Echeburúa, Reference Amor and Echeburúa2010; Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Herrero et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas and Expósito2023; Gilbert & Gordon, Reference Gilbert and Gordon2017; Nicholson & Lutz, Reference Nicholson and Lutz2017). Specifically, a recent systematic review (Badenes-Sastre et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Medinilla-Tena, Spencer and Expósito2025) indicates that IPV victims often display cognitive distortions, including minimizing the violence or its impact, denying injuries, maintaining hope for change, normalizing IPV, exonerating the aggressor, or engaging in self-blame, among others. These distortions significantly influence their decision to remain in the violent relationship. Also, women often leave the aggressor and return multiple times before ultimately breaking free (Anderson & Saunders, Reference Anderson and Saunders2003; Zapor et al., Reference Zapor, Wolford-Clevenger and Johnson2018). Specifically, women who attributed more responsibility to the aggressor for the IPV tended to make more attempts to leave the relationship (Rhatigan et al., Reference Rhatigan, Street and Axsom2006). In this sense, it is necessary to explore the cognitive distortions that hinder women’s perception of reality and their ability to break free from violent relationships, helping them avoid distorted reasoning and recognize that they are in a maladaptive relationship.

Finally, some sociodemographic variables, such as age, education level, economic dependency, relationship status, and having children, among others, must be considered because they can be factors that make women vulnerable to violent relationships and, consequently, affect their decisions to leave the violent relationship (Aiquipa & Canción, Reference Aiquipa Tello and Canción Suárez2020; Al-Modallal, Reference Al-Modallal2023; Ben-Porat & Reshef-Matzpoon, Reference Ben-Porat and Reshef-Matzpoon2023; Cravens et al., Reference Cravens, Whiting and Aamar2015).

The Present Study

Based on the considerations, we aimed to explore the role of cognitive distortions in women’s decision-making regarding their current relationships, analyzing differences between women who experienced IPV and those who did not. Also, we aimed to examine the potential moderating effect of the traditional female role and dependency on the relationship between experiencing (or not) IPV and cognitive distortions. As an additional objective, we investigated differences between women’s groups (IPV victims or nonvictims) in the traditional female role, dependency, cognitive distortions, and the use of strategies to loyalty or exit in a violent relationship. Ultimately, we observed the prevalence of IPV in our sample, as well as the scores and correlations among the main variables.

Hypotheses

-

1. Cognitive distortions are positively associated with the traditional female role (H1a), dependency (H1b), and loyalty strategies (H1c), as well as negatively associated with exit strategies (H1d).

-

2. The group of women who experienced IPV by their current partner are expected to exhibit higher scores in adherence to the traditional female role (H2a), dependency (H2b), cognitive distortions (H2c), and the use of loyalty strategies (H2d), as well as lower use of exit strategies (H2e), compared to women who do not experience IPV by their current partner.

-

3. The group of women who have experienced IPV by their current partner exhibit higher levels of cognitive distortions and, consequently, a greater tendency to use strategies to maintain the relationship (loyalty) compared to women who do not experience IPV by their current partner.

-

4. The group of women who have experienced IPV by their current partner exhibit higher levels of cognitive distortions and, consequently, a lower tendency to use strategies to end the relationship (exit) compared to women who do not experience IPV by their current partner.

-

5. Higher adherence to the traditional female role and greater dependency positively moderates the relationship between the women’s group condition (IPV victims versus nonvictims) and the use of cognitive distortions. Specifically, higher adherence to the female role and dependency in IPV victims will have more use of cognitive distortions.

Method

Design and Participants

This study consisted of a quasi-experimental design (Montero & León, Reference Montero and León2007). The sample size was calculated a priori using the software G*power (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner and Lang2009). A total of 103 participants were required to perform a linear multiple regression, fixed-model R2 increase, with a medium effect size of .15 (Bologna, Reference Bologna, Caro, Cupani, D’Amelio, Galibert, Lorenzo, Santillán and Rodríguez2022), a significance level of α = 0.05 (two-tailed), and power of 0.80 (Cárdenas & Arancibia, Reference Cárdenas and Arancibia2014).

The initial sample was composed of 637 participants, with 246 of them excluded for the following reasons: (a) not completing the survey; (b) being under 18 years of age; (c) non-Spanish; and (d) incorrectly answering the attention check questions (“If you are reading this question, mark 3”). The final sample comprised 391 women (207 confirmed IPV in their current relationship and 184 did not confirm any violent episodes by their current partner). Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 75 years (M = 31.09, SD = 13.21). Most of them had higher education (89.8%), were not economically dependent on their current partner (96.2%), were not living with their current partner (54.5%), and did not have children (70.6%). Regarding the duration of the intimate relationship, 7.2% of the women had been in a relationship for less than a year, 46% for 1–3 years, and the remainder for more than 3 years. All women voluntarily participated in the study and were informed of the objectives. No monetary compensation was provided for participation.

Procedure

The Ethics Committee in Human Research of the University of Granada reviewed and approved all procedures. First, we developed an online survey on the Qualtrics platform and disseminated it through personal and professional social media (Instagram, Facebook, and WhatsApp) and institutional email, including a message requesting the participation of women over 18 years old who are currently in a relationship with a man. Additionally, participants and anyone who received the message—regardless of whether they met the inclusion criteria—were encouraged to share the survey with their own contacts, following a snowball sampling approach to increase reach. Afterward, women who met inclusion criteria and were interested in participating clicked on the survey link, were informed about the study’s objectives, and signed the informed consent form, ensuring the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses and the exclusive use of their answers for research purposes.

We formed the groups based on women’s responses to the WHO’s Violence Against Women instrument. If women indicated experiencing IPV, they were included in the “IPV victims” condition (referring to women who experienced IPV); otherwise, they were incorporated in the nonvictims condition (referring to women who did not experience IPV). To be included in the group of IPV victims, they had to respond one, few, or many to any of the 25 items in the WHO’s Violence Against Women instrument (Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas, & Expósito, Reference Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas and Expósito2023; Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas and Expósito2023), which assesses physical, sexual, psychological, and controlling violence by their current partner either in their lifetime or in the last 12 months. Conversely, if women answered never to all 25 items, they were included in the nonvictims group.

Instruments

Traditional Female Role

The O’Kelly Women’s Beliefs Scale (OWBS; (O’Kelly, Reference O’Kelly2011; Rovira et al., Reference Rovira, Lega, Suso-Ribera and Orue2020) was used to measure women’s irrational beliefs regarding the traditional female role stereotype acquired through the influence of the social context in which they live. This scale consists of 23 items (e.g., “I must have a husband/male partner”) with a Likert-type response (1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree). The total adherence score was calculated by summing the values of all directly rated items based on the level of agreement. The Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale in this study was .85.

Dependency

The Spouse-Specific Dependency Scale (Valor-Segura et al., Reference Valor-Segura, Expósito and Moya2009) was applied to assess dependency on the partner using 17 items (e.g., “I find it difficult to be separated from my partner”), each rated on a Likert response scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree), obtaining a total score. In this study, the scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of .78.

Intimate Partner Violence Against Women

The WHO’s Violence Against Women instrument (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Herrero et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas and Expósito2023), through 25 items, served to assess women’s experiences of violent behaviors perpetrated by a current or former male partner over a lifetime and in the last 12 months. In this study, women were asked about their current intimate relationship. Particularly, nine items measured physical violence (e.g., “Has your current partner ever pushed you?”), three items sexual violence (e.g., “Has your partner or former partner ever forced you to have sexual intercourse when you did not want to?”), seven items psychological violence (e.g., “Has your current partner ever humiliated you in front of other people?”), and six items controlling behaviors (e.g., “Has your current partner ever tried to restrict contact with your family of birth?”). A Likert-type frequency response format (1 = never; 2 = one; 3 = few; and 4 = many times) was included. In addition, participants were asked about the occurrence of each form of IPV in the last 12 months by their current partner. In this sense, a dichotomous response format was offered in which women had to answer “yes” or “no” to each of the 25 items. The Cronbach’s alpha for this instrument was .91. Based on the scores on this instrument, the study groups of women were established (IPV victims versus nonvictims).

Cognitive Distortions

The Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ; Domínguez-Sánchez et al., Reference Domínguez-Sánchez, Lasa-Aristu, Amor and Holgado-Tello2011) was employed to measure, through 36 items, the emotional regulation strategies that individuals use to respond to stressful life situations (e.g., “I think that I am to blame”). The response format was Likert type, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The total score was obtained by calculating the mean of all directly scored items. For this instrument, the Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was .96.

Exit and Loyalty Strategies

The subscales exit (7 items, e.g., “When I am unhappy with my partner, I suggest breaking up”) and loyalty (7 items, e.g., “When my partner hurts me, I don’t say anything but simply forgive him”) of the Accommodation Among Romantic Couples Scale (Valor-Segura et al., Reference Valor-Segura, Lozano and Garrido-Macías2020) were used to assess decision-making in women regarding their relationships. The 9-point Likert response scale ranged from 1 (never do that) to 9 (I always do that). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was .88 for exit and .72 for loyalty.

Demographic Information

Data regarding women’s age, nationality, educational level (1 = no studies, 2 = primary school, 3 = secondary education, 4 = high school diploma, 5 = vocational training, 6 = university education), economic dependency (1 = Yes, 2 = No), relationship status (1 = cohabiting with partner, 2 = non -cohabiting with partner), duration of the relationship (1 = less than 3 months, 2 = less than 6 months, 3 = less than 1 year, 4 = between 1–3 years, 5 = more than 5 years, 6 = more than 10 years), and having children (1 = Yes, 2 = No) were collected.

Analysis Strategy

We analyzed the data using the SPSS Program, Version 28. Initially, we conducted descriptive analysis to explore the sample characteristics (see Participants section) and frequencies of IPV in the group of women who indicated violence by their current partner. Then, we performed a Pearson correlation analysis to examine the relation between cognitive distortions and the rest of the assessed variables (women’s group condition, traditional female role, dependency, and strategies to loyalty or exit in the relationship), testing Hypothesis 1. After that, to test Hypothesis 2, we conducted a Student’s t-test for independent samples in order to determine any differences in the traditional female role, dependency, cognitive distortions, and decision-making between both groups of women. To test Hypotheses 3 and 4, we applied PROCESS Model 4, and for Hypothesis 5, we used PROCESS Model 9, following the approach proposed by Hayes (Reference Hayes2013). For the mediation and moderate mediation analyses, we estimated conditional spillover effects using 10,000 bootstrap samples, generating bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals.

We conducted these mediation analyses twice: once to examine the model with exit strategies and once for loyalty strategies. Specifically, in PROCESS Model 4, we included the group condition (IPV victims versus nonvictims) as a predictor variable (X), cognitive distortions as a mediating variable (M), and decision-making strategies loyalty or exit in the relationship as dependent variables (Y). The analyses controlled for sociodemographic variables such as age, education level, economic dependence, relationship status (with or without cohabitation), duration of the relationship, and having children. Similarly, PROCESS Model 9 retained the variables from Model 4 in the same order but included two moderators: traditional female role (W) and dependency (Z), in the relationship between condition (women’s group) and cognitive distortions. We controlled for the same sociodemographic variables in this analysis to ensure the consistency of the results.

Results

Prevalence of IPV in the Sample

In this study, 36.6% of the women indicated having suffered physical, sexual, psychological, or controlling behaviors from previous partners, 52.9% of them indicated having experienced some form of violence from their current partner, and 21.5% indicated both experienced (by previous partners and by current partner) some form of violence. Particularly, 9.2% of them referred to physical violence, 10.2% sexual violence, 38.4% psychological violence, and 34% controlling behaviors by their current partner at some point in their relationship. Otherwise, 6.6% of women experienced physical violence in the last 12 months, 6.9% sexual violence, 26.1% psychological violence, and 22.3% controlling behaviors.

Cognitive Distortions and Related Variables

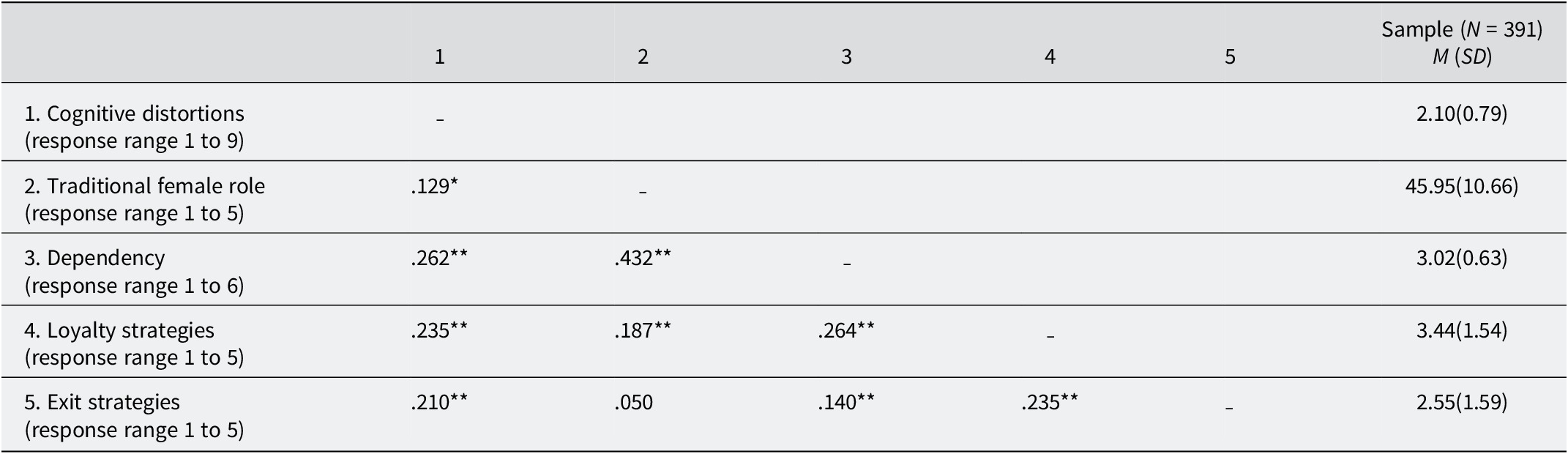

To test Hypothesis 1—“Cognitive distortions are positively associated with the traditional female role (H1a), dependency (H1b), and loyalty strategies (H1c), and negatively associated with exit strategies (H1d)”—a Pearson correlation (see Table 1) was carried out. The results showed that cognitive distortions are positively correlated with the traditional female role (r = .129, p = .01), dependency (r = .267, p < .001), loyalty strategies (r = .235, p < .001), and exit strategies (r = .210, p < .001). Therefore, Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1c were accepted, whereas Hypothesis 1d was rejected.

Table 1. Correlation analysis among cognitive distortions, traditional female role, dependency, loyalty, and exit strategies

Note. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Traditional Female Role, Dependency, Cognitive Distortions, Loyalty and Exit Strategies According to Women’s Group (IPV Victims versus Nonvictims)

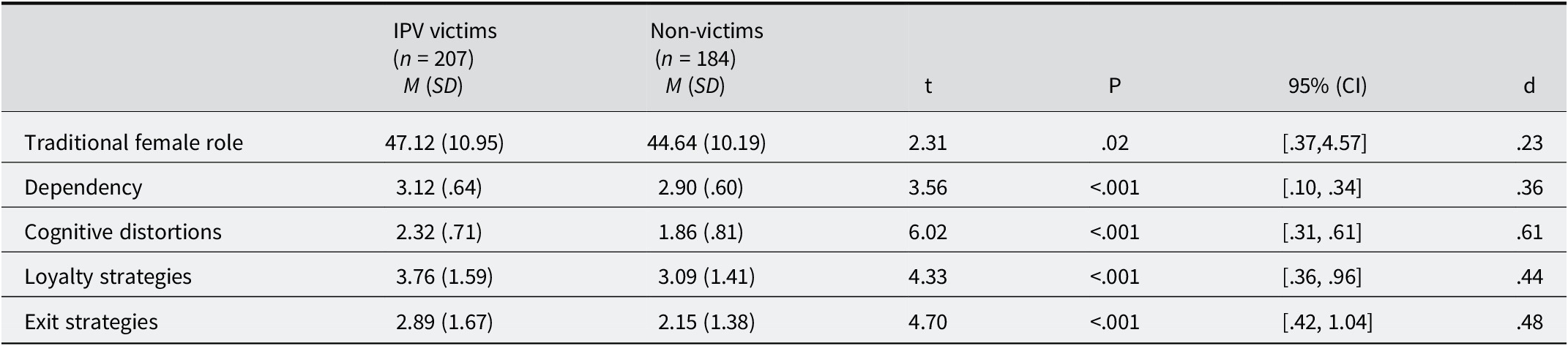

To analyze the differences between women’s groups in the variables evaluated (traditional female role, dependency, cognitive distortions, and strategies of loyalty and exit in the relationship), a Student’s t-test was conducted.

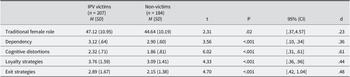

As can be seen in Table 2, the results revealed significant differences between the women’s group, presenting IPV victims’ higher scores on the traditional female role (M = 47.12, SD = 10.95 versus [nonvictims group] M = 44.64, SD = 10.19), dependency (M = 3.12, SD = .64 versus M = 2.90, SD = .60), cognitive distortions (M = 2.32, SD = .71 versus M = 1.86, SD = .81), loyalty strategies (M = 3.76, SD = 1.59 versus M = 3.09, SD = 1.41), and exit strategies (M = 2.89, SD = 1.67 versus M = 2.15, SD = 1.38) than the nonvictims group. These findings confirmed Hypotheses 2a, 2b, 2c, and 2d, but they rejected Hypothesis 2e.

Table 2. Differences between women’s group condition in traditional female role, dependency, cognitive distortions, and decision-making strategies (loyalty and exit)

Note. IPV = Intimate Partner Violence; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Mediating Effect of Cognitive Distortions on the Relationship Between Women’s Group (IPV Victims versus Nonvictims) and the Use of Loyalty and Exit Strategies

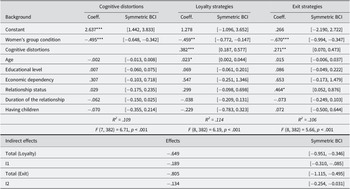

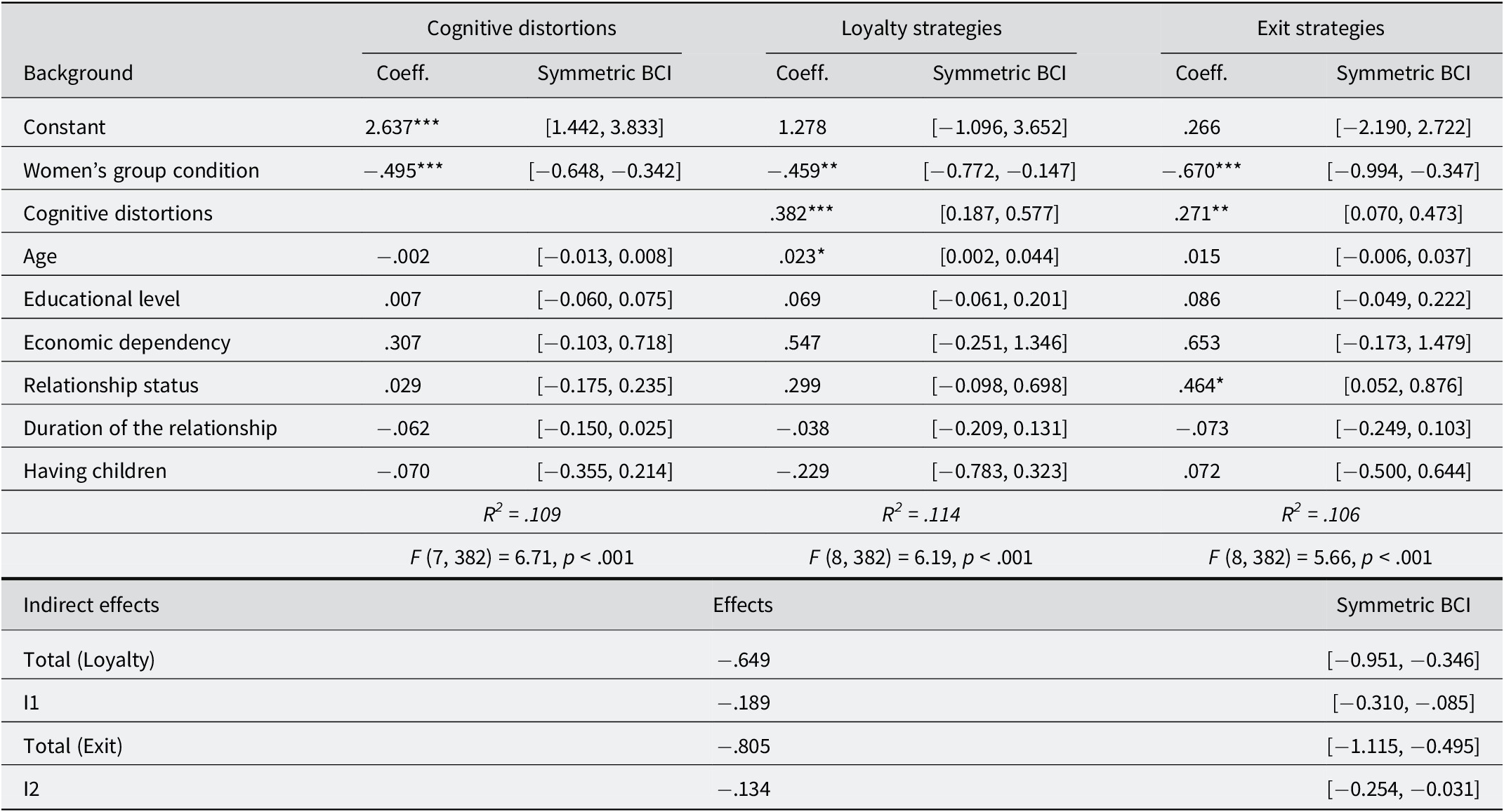

The mediating effects of cognitive distortions on the relationship between the group condition (IPV victims versus nonvictims) and the use of loyalty (Hypothesis 3) and exit (Hypothesis 4) strategies were tested using Model 4 of PROCESS. The results were controlled for age, educational level, economic dependency, relationship status, relationship duration, and having children. A significant effect was found for age; as age increases, there was a greater use of strategies to maintain the relationship (loyalty; b = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.00, 0.04]) and relationship status (not cohabiting with their partner), with an increased use of strategies to exit the relationship (b = 0.46, SE = 0.21, 95% CI [0.05, 0.87]).

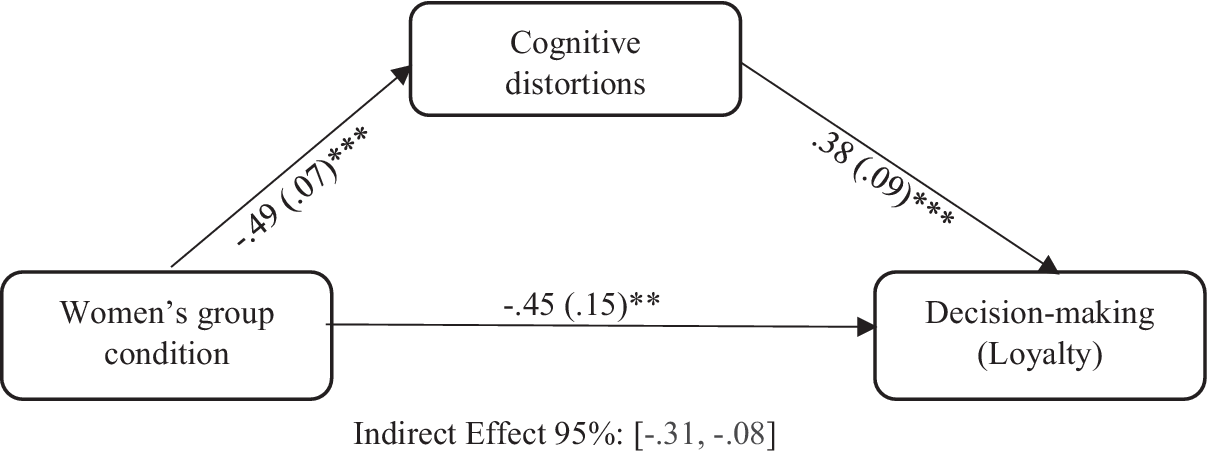

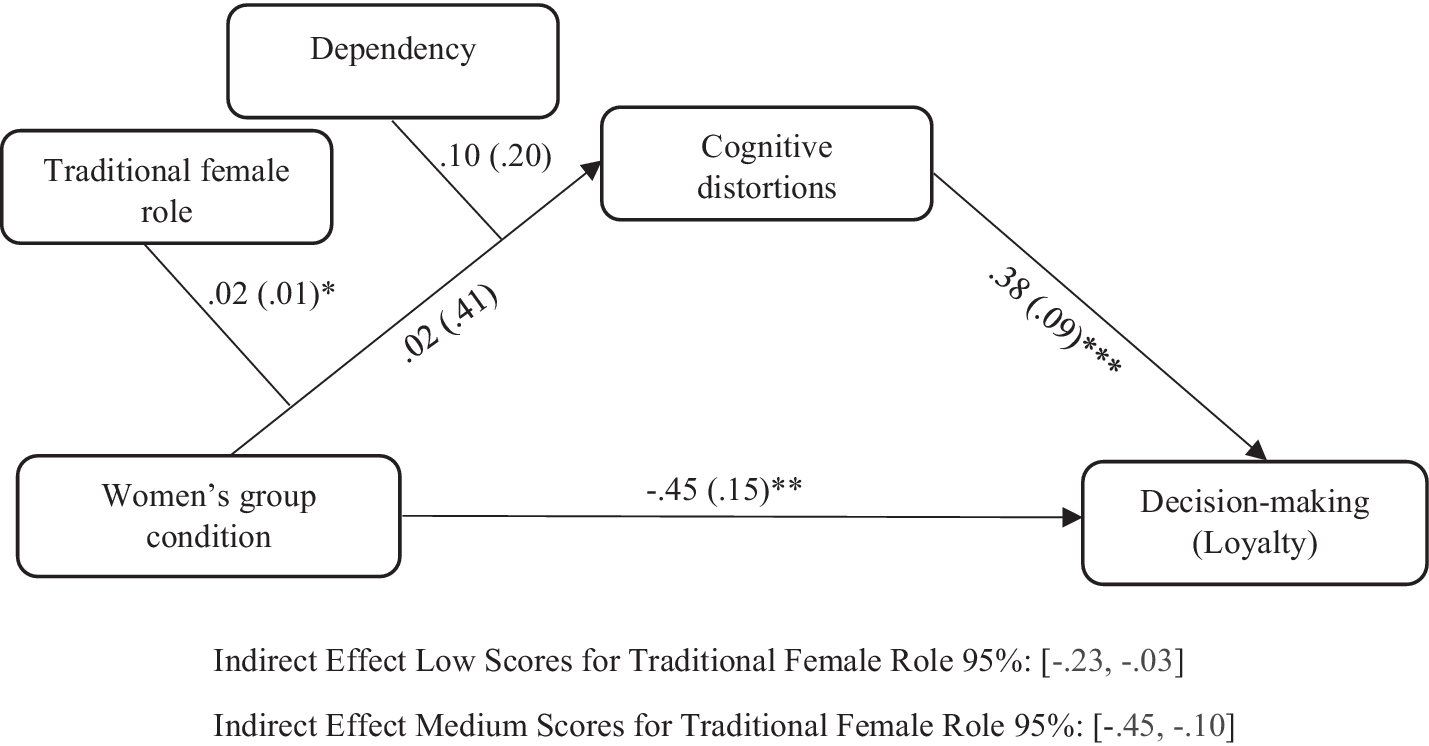

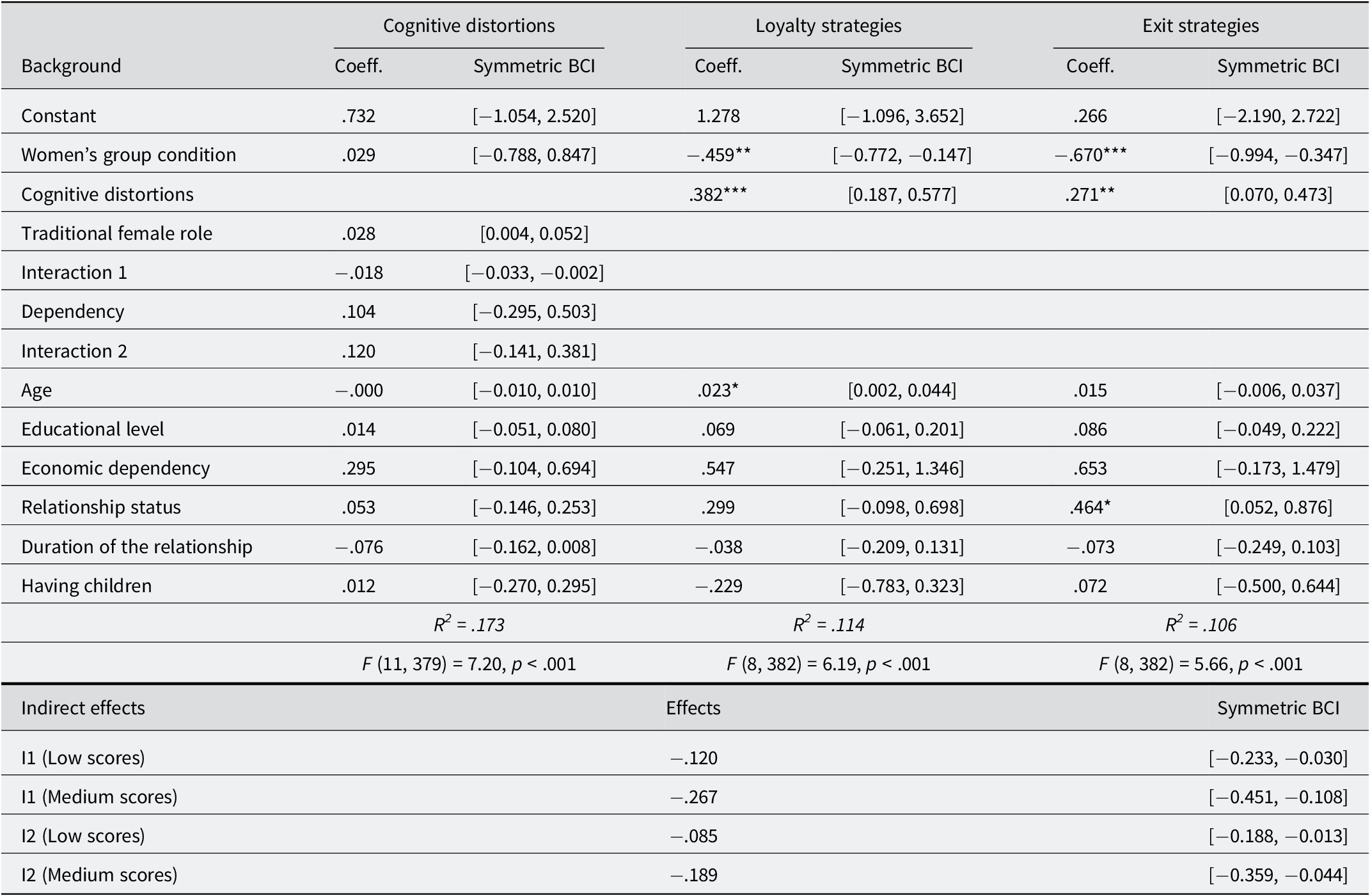

Regarding Hypothesis 3, the findings indicated a significant model. That is, an indirect effect mediated by cognitive distortions was observed, suggesting that victims of IPV had higher levels of cognitive distortions, which, in turn, increased the likelihood of using loyalty strategies (b = −0.18, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.31, −0.08]; see Figure 1 and Table 3). These results supported Hypothesis 3 and confirmed the validity of the proposed mediation model.

Figure 1. Conceptual model showing the proposed relationship between women’s group condition and decision-making (loyalty), mediated by cognitive distortions.

Note. Unstandardized beta coefficients are reported, with standard errors in parentheses. Women’s group condition: 1 = IPV victims; 2 = non-victims; **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 3. Mediating effect of cognitive distortions between women’s group condition and the use of loyalty and exit strategies

Note. Women’s group condition: 1 = IPV victims, 2 = non-victims; IPV = intimate partner violence; Educational level: 1 = no studies, 2 = primary school, 3 = secondary education, 4 = high school diploma, 4 = vocational training, 5 = university education; Economic dependency: 1 = Yes, 2 = No; Relationship status: 1 = cohabiting with partner, 2 = non-cohabitating with partner; Duration of the relationship: 1 = less than 3 months, 2 = less than 6 months, 3 = less than 1 year, 4 = between 1–3 years, 5 = more than 5 years, 6 = more than 10 years; Having children: 1 = Yes, 2 = No; I1 = women’s group condition → cognitive distortion → loyalty strategies; I2 = women’s group condition → cognitive distortion → exit strategies; symmetric BCI: symmetric bootstrapping confidence interval. The indirect effects are significant where the bootstrap confidence interval does not include the value 0. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

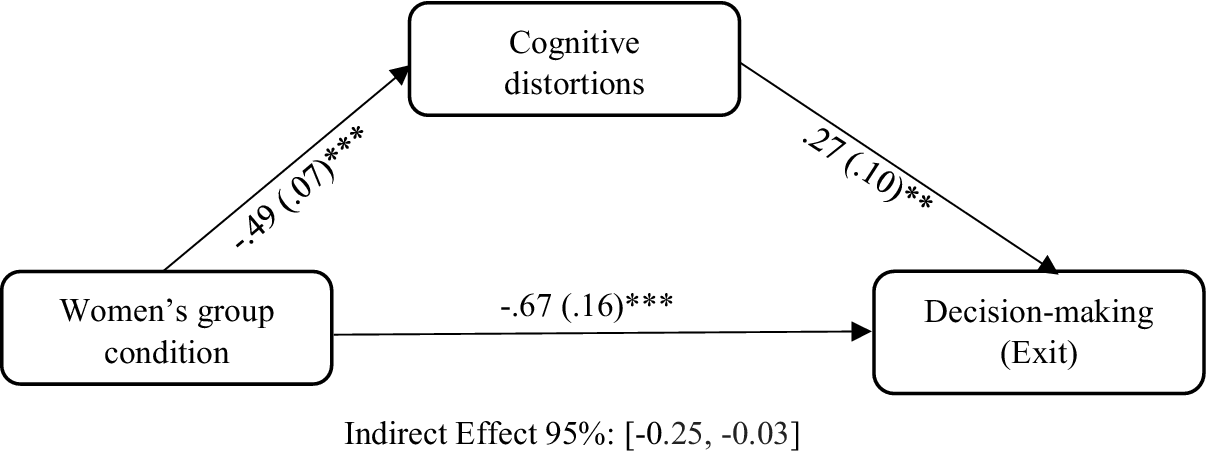

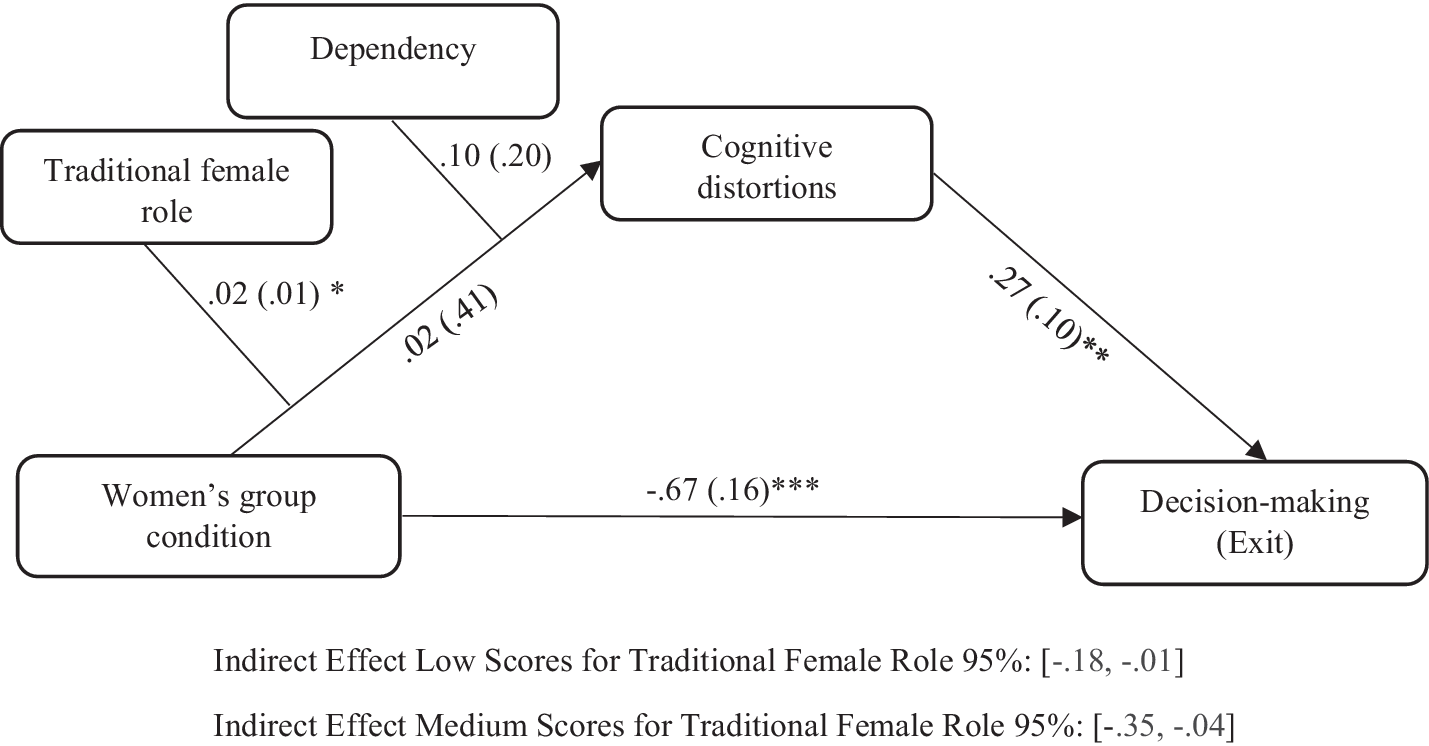

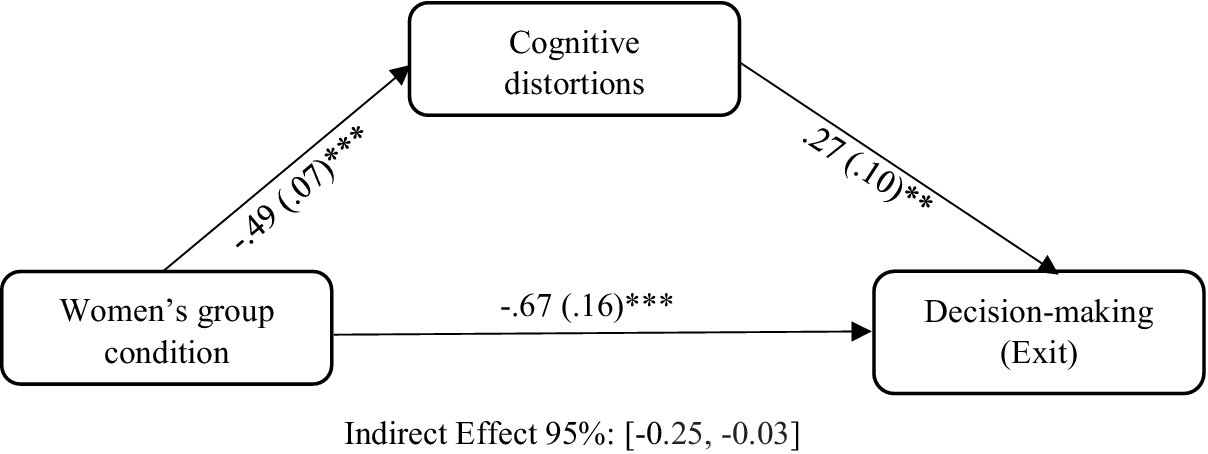

Otherwise, cognitive distortions mediated the relationship between the women’s group condition and the use of exit strategies (Hypothesis 4). Specifically, an indirect effect mediated by cognitive distortions was observed, suggesting that IPV victims condition presented higher levels of cognitive distortions and, consequently, tended to use exit strategies to a greater extent than nonvictims (b = −0.13, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.25, −0.03]; see Figure 2 and Table 3). Although the proposed mediation model was significant, these results lead to the rejection of Hypothesis 4.

Figure 2. Conceptual model showing the proposed relationship between women’s group condition and decision-making (exit), mediated by cognitive distortions.

Note. Unstandardized beta coefficients are reported, with standard errors in parentheses. Women’s group condition: 1 = IPV victims; 2 = non-victims; **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Moderate Effect of the Traditional Female Role and Dependency on the Relationship Between Women’s Group (IPV Victims versus Nonvictims) and Cognitive Distortions

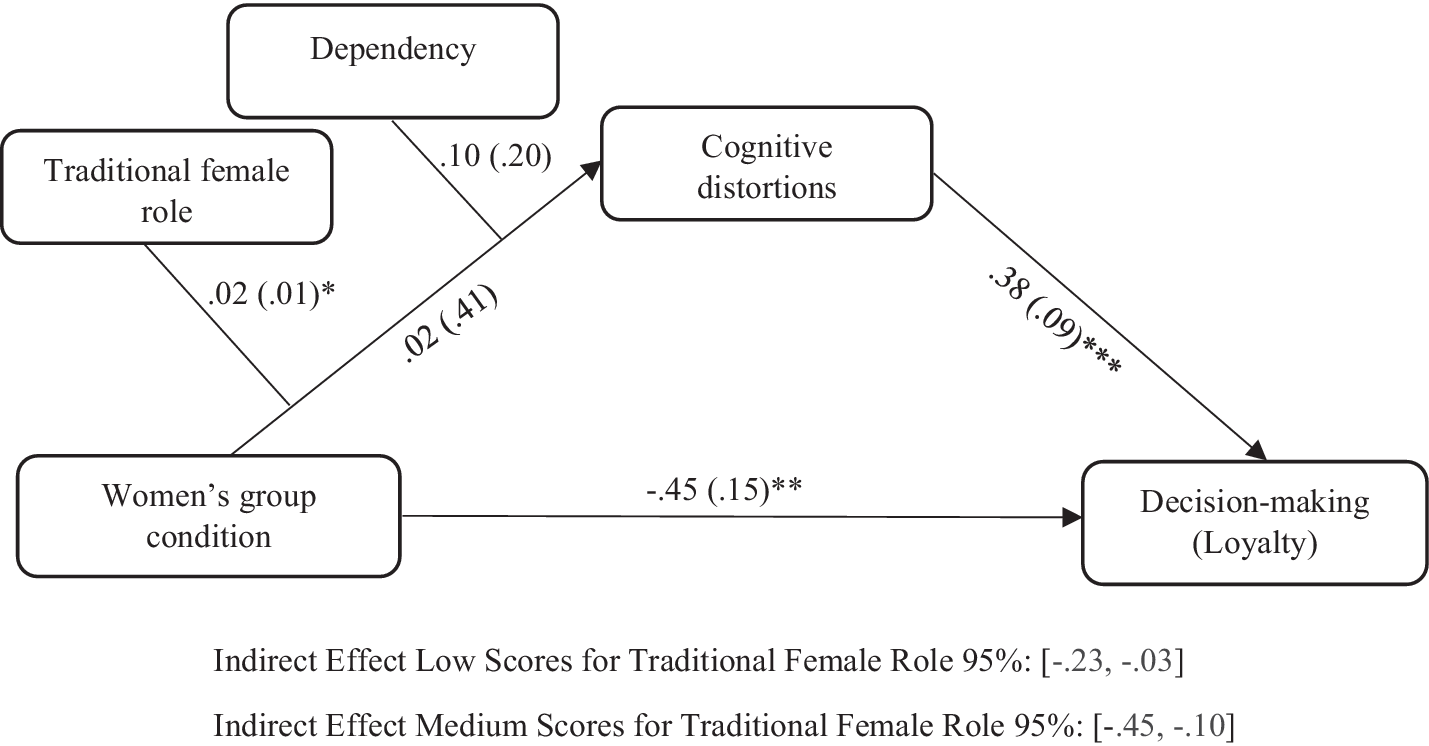

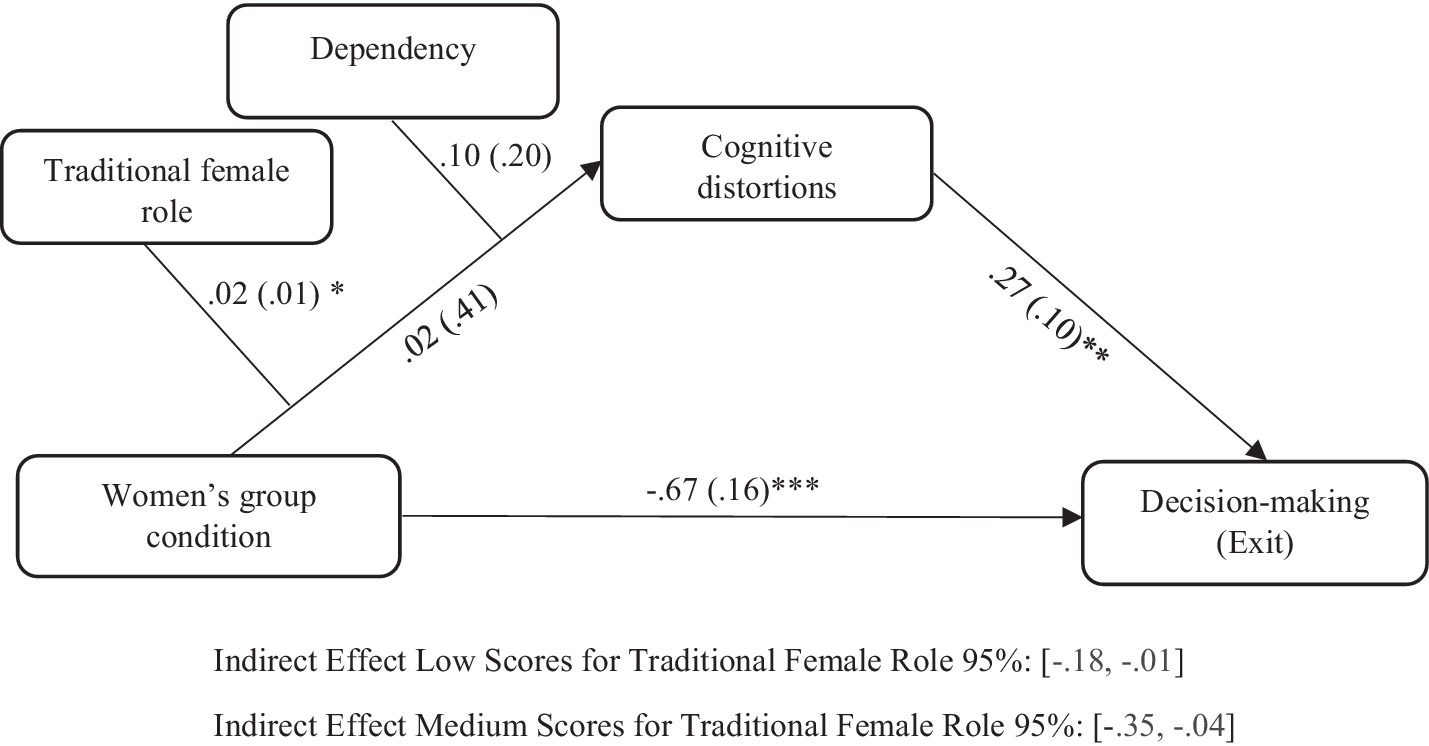

For Hypothesis 5—“Higher adherence to the traditional female role and greater dependency positively moderate the relationship between the women’s group condition (IPV victims versus nonvictims) and the use of cognitive distortions. Specifically, higher adherence to the female role and dependency in IPV victims will have more use of cognitive distortions”—Model 9 of PROCESS was applied. The analysis was controlled for sociodemographic variables (age, educational level, economic dependency, relationship status, duration of the relationship, and having children). Age had a significant positive effect on loyalty strategies (b = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.00, 0.04]), and women who were not cohabiting with their partner showed a higher likelihood of using strategies to exit the relationship (b = 0.46, SE = 0.21, 95% CI [0.05, 0.87]).

Otherwise, the main findings point out a positive moderating effect of the traditional female role on cognitive distortions (b = .02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.00, 0.05]), showing that those female victims of IPV had a higher adherence to the traditional female role and presented more cognitive distortions. Likewise, the women’s group condition had a significant effect on cognitive distortions through the moderated effect of the adherence to the traditional female role (b = −.01, SE = 0.00, 95% CI [−0.03, −0.00]). Additionally, IPV victims’ traditional female role scores, which were influenced through cognitive distortions in exit and loyalty decision-making, were, in both models, low (b = −.12, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.23, −0.03]; b = −.08, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.18, −0.01]) and medium (b = −.26, SE = 0. 08, 95% CI [−0.45, −0.03]; b = −.18, SE = 0.08, 95% CI [−0.35, −0.04]). With respect to dependency, no significant moderating effect was found in the relationship between the women’s group condition and cognitive distortions. These findings partially supported Hypothesis 5 (see Figures 3 and 4 and Table 4).

Figure 3. Conceptual model of the proposed relationship between women’s group condition and decision-making (loyalty), mediated by cognitive distortions and moderated by traditional female role and dependency.

Note. Unstandardized beta coefficients are reported, with standard errors in parentheses. Women’s group condition: 1 = IPV victims; 2 = non-victims; *p < .05,**p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 4. Conceptual model of the proposed relationship between women’s group condition and decision-making (exit), mediated by cognitive distortions and moderated by traditional female role and dependency.

Note. Unstandardized beta coefficients are reported, with standard errors in parentheses. Women’s group condition: 1 = IPV victims; 2 = non-victims; *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 4. Mediating effects of cognitive distortions on women’s group condition and loyalty/exit strategies, moderated by traditional female role and dependency

Note. Women’s group condition: 1 = IPV victims, 2 = non-victims; IPV = intimate partner violence; Educational level: 1 = no studies, 2 = primary school, 3 = secondary education, 4 = high school diploma, 4 = vocational training, 5 = university education; Economic dependency: 1 = Yes, 2 = No; Relationship status: 1 = cohabiting with partner, 2 = non-cohabitating with partner; Duration of the relationship: 1 = less than 3 months, 2 = less than 6 months, 3 = less than 1 year, 4 = between 1–3 years, 5 = more than 5 years, 6 = more than 10 years; Having children: 1 = Yes, 2 = No; I1 = women’s group condition (X) → traditional female role (W) → dependency (Z) → cognitive distortions (M) → loyalty strategies (Y); I2 = women’s group condition (X) → traditional female role (W) → dependency (Z) → cognitive distortion (M) → decision making (exit) (Y). Symmetric BCI: symmetric bootstrapping confidence interval. The indirect effects are significant where the bootstrap confidence interval does not include the value 0. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to explore how cognitive distortions influence the decision-making process of leaving or staying in a violent relationship, depending on the condition (IPV victims versus nonvictims). The findings reveal novel insights into the obstacles women encounter when making decisions about relationships. Specifically, this study confirmed that cognitive distortions promote the maintenance of violent relationships, particularly among women who experience such violence (IPV victims group), as they represent a distortion of reality. However, contrary to expectations, these distortions also appear to facilitate the decision to leave the violent relationship within the IPV victims group. These results supported some hypotheses of this study while rejecting others.

On one side, an initial objective of this study was to identify the prevalence of IPV in our sample, as well as the scores and correlations between the main variables analyzed. The results revealed that 36.6% of the women had experienced violence from a previous partner, whereas 52% informed experiencing violence from their current partner. Among current partners, the most prevalent form of violence was psychological, followed by controlling behaviors, and, to a lesser extent, sexual and physical violence. The prevalence of these forms of violence observed in this study exceeds the data reported in the European Gender Violence Survey 2022, which also indicated that 27.8% of women confirmed having suffered psychological violence (including controlling behaviors) in their lifetime, in greater proportion than physical and sexual violence (Delegación del Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género, 2022). Although these forms of violence may be less obvious, they are likely to have a significant impact on the mental health and well-being of the women who experience them (Marshall, Reference Marshall1999; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Sleath and Tramontano2021), which requires consideration.

Otherwise, a significant relationship of cognitive distortions with the traditional female role, dependence, loyalty, and exit strategies was found, partially confirming Hypothesis 1: “Cognitive distortions are positively associated with the traditional female role (H1a), dependence (H1b) and loyalty strategies (H1c), as well as negatively associated with exit strategies (H1d).” That is, according to previous research (Bogarín Azuaga et al., Reference Bogarín Azuaga, Gamarra Méreles, Bagnoli Peralta, Mongelós Gamarra and González Ramírez2021; Nicholson & Lutz, Reference Nicholson and Lutz2017; Rovira et al., Reference Rovira, Lega, Suso-Ribera and Orue2020; Vinagre-González et al., Reference Vinagre-González, Puente-López, Aguilar-Cárceles, Aparicio-García and Loinaz2023), cognitive distortions were positively correlated with target variables (traditional female role, dependency, and loyalty strategies). However, the use of exit strategies was also positively related to cognitive distortions, rejecting Hypothesis 1d.

Likewise, Hypothesis 2—“The group of women who experienced IPV by their current partner are expected to exhibit higher scores in adherence to the traditional female role (H2a), dependency (H2b), cognitive distortions (H2c), and the use of loyalty strategies (H2d), as well as lower use of exit strategies (H2e), compared to women who do not experience IPV by their current partner”—received partial support. As expected, the IPV victims group showed higher scores in traditional female role, dependency, cognitive distortions, and the use of loyalty strategies than nonvictims group. Contrary to what was expected, the group of IPV victims (versus nonvictims) also showed higher scores in the use of exit strategies. This finding is consistent with that of Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas et al. (Reference Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas and Expósito2023), who found greater use of exit strategies in women who informed IPV (versus nonvictims). In this sense, it will be essential to consider the role of some explanatory variables such as dependency or cognitive distortions. Moreover, ending a violent relationship is a complex process where victims often experience cycles of leaving and returning with the aggressor rather than a definitive break (Anderson & Saunders, Reference Anderson and Saunders2003; Cravens et al., Reference Cravens, Whiting and Aamar2015; Gilbert & Gordon, Reference Gilbert and Gordon2017). All of this must be considered when understanding the complexity of decision-making in violent relationships.

Regarding to Hypothesis 3—“The group of women who have experienced IPV by their current partner exhibit higher levels of cognitive distortions and, consequently, a greater tendency to use strategies to maintain the relationship (loyalty) compared to women who do not experience IPV by their current partner”—the results aligned with previous research (Badenes-Sastre et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Medinilla-Tena, Spencer and Expósito2025; Byrne & Arias, Reference Byrne and Arias2004; Heim et al., Reference Heim, Trujillo Tapia and Quintanilla Gonzáles2018) that indicated the role of cognitive distortions in the use of loyalty strategies in violent relationships. That is, women victims of IPV, in order to maintain consistency in their decision to continue with the relationship (use of loyalty strategies), activated cognitive distortions such as positive re-evaluation of the situation or hope for future change. These cognitive distortions acted as a coping mechanism in the face of traumatic events (e.g., IPV), allowing women to maintain a more positive perception of their situation and preserve their emotional stability (Heim et al., Reference Heim, Trujillo Tapia and Quintanilla Gonzáles2018).

Surprisingly, Hypothesis 4—“The group of women who have experienced IPV by their current partner exhibit higher levels of cognitive distortions and, consequently, a lower tendency to use strategies to end the relationship (exit) compared to women who do not experience IPV by their current partner”—was rejected. As could be observed, the IPV victims group (versus nonvictims group) presented higher levels of cognitive distortions, which were associated with a greater use of exit strategies. As mentioned above, it would seem that the distortions have a significant effect in keeping women in the violent relationship (loyalty strategies) but not so much in making the decision to leave it. This is an interesting finding, as according to Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas et al. (Reference Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas and Expósito2023), variables such as dependency or commitment to the relationship would explain why IPV victims use fewer exit strategies. However, these variables did not have a significant effect on the use of strategies to remain in the relationship. In the latter case, cognitive distortions play a more prominent role, as shown by the results of the present study. Also, there may be a discrepancy between the willingness to act in situations of IPV and the actions taken in practice (Sánchez-Prada et al., Reference Sánchez-Prada, Delgado-Alvarez, Bosch-Fiol, Ferreiro-Basurto and Ferrer-Perez2022). In this case, it is common for IPV victims to return to the perpetrator multiple times before ending the relationship for good (Gilbert & Gordon, Reference Gilbert and Gordon2017; Zapor et al., Reference Zapor, Wolford-Clevenger and Johnson2018), showing that cognitive distortions play a significant role in the reappraisal of the violent situation (Nicholson & Lutz, Reference Nicholson and Lutz2017), which could explain why, despite the attempts to leave the relationship, many return to it.

Finally, adherence to the traditional female role and dependency were considered to be possible moderators between the group condition (IPV victims versus nonvictims) and cognitive distortions. Hypothesis 5—“Higher adherence to the traditional female role and greater dependency positively moderate the relationship between the women’s group condition (IPV victims versus nonvictims), and the use of cognitive distortions”—was refused. Although the traditional female role moderated the relation between the women’s condition (IPV victims versus nonvictims) and cognitive distortions, no significant effect was found on dependency.

Regarding the traditional female role, beliefs acquired during the socialization process regarding roles in romantic relationships (e.g., “Things should not go wrong in my family/marriage, as I would be responsible”) can trigger cognitive distortions in women, encouraging them to remain in the relationship (Çelikkaleli & Kaya, Reference Çelikkaleli and Kaya2016; Rovira et al., Reference Rovira, Lega, Suso-Ribera and Orue2020; Vinagre-González et al., Reference Vinagre-González, Puente-López, Aguilar-Cárceles, Aparicio-García and Loinaz2023), requiring consideration. Conversely, according to previous studies (Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Beltrán-Morillas and Expósito2023; Garrido-Macías et al., Reference Garrido-Macías, Valor-Segura and Expósito2017; Valor-Segura et al., Reference Valor‐Segura, Expósito, Moya and Kluwer2014), dependency is key to understanding why women make decisions to leave or stay in a relationship, especially in women involved in IPV. Although dependency is associated with decision-making in IPV, it does not appear to have a sufficient effect in moderating the relationship between women groups (IPV victims versus nonvictims) and cognitive distortions. Despite this, the role of dependency cannot be overlooked, as IPV victims tend to exhibit greater dependency on their partners, which carries significant implications for decision-making about whether to leave or remain in the relationship. It is important to note that this should not be seen as victim-blaming, as the social context and gender roles plays a key role in shaping and maintaining these patterns of dependency.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present study has some limitations that should be considered and addressed in future research. First, to obtain more accurate results and avoid influence of culture, the sample only consisted of women of Spanish nationality. However, cognitive distortions may manifest differently across cultural contexts (Lega & Ellis, Reference Lega and Ellis2001) where community norms give privilege or superior status to men and inferior status to women, thus accepting IPV (WHO, 2021). Future research should focus on examining cognitive distortions in various cultural settings, particularly in regions where patriarchal attitudes continue to dominate in more traditional families where men have greater power than women (Chandarana et al., Reference Chandarana, Rai and Ravi2024).

Second, with respect to the controlled variables, such as age, educational level, economic dependency, relationship status (with or without cohabitation), duration of the relationship, and having children, significant positive effects were obtained in some of them. Notably, older women were more likely to use loyalty strategies, whereas women who did not live with their partners were less likely to use exit strategies. In this regard, additional research is recommended to better understand the role of these variables in the decision-making process of women in IPV situations as well as the possible factors related, such as commitment with the relationship. Particularly, it is important to distinguish between women who live with their aggressor and those who do not, as Yamawaki et al. (Reference Yamawaki, Ochoa-Shipp, Pulsipher, Harlos and Swindler2012) suggested that individuals in dating relationships tend to be less committed than married couples and are therefore seen as more likely to end the relationship.

Third, we collected information on the time point (lifetime and last 12 months) at which women experienced IPV. Nevertheless, we did not control for the potential influence of experiencing violence recently (last 12 months) or in the past on cognitive distortions. Considerably more work will be recommended to determine the role of cognitive distortions in decision-making, especially when women find themselves in a real situation of cognitive dissonance (i.e., discomfort due to the discrepancy between what they think and what they do; Festinger, Reference Festinger1975).

Lastly, we assessed cognitive distortions using the CERQ (Domínguez-Sánchez et al., Reference Domínguez-Sánchez, Lasa-Aristu, Amor and Holgado-Tello2011). We selected this questionnaire due to the limited availability of specific instruments that evaluate cognitive distortions in situations of IPV. In this sense, it is essential to have suitable and validated assessment tools to effectively identify these distortions in female victims of IPV (Badenes-Sastre et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Medinilla-Tena, Spencer and Expósito2025), and future studies should consider the development of this measure. Similarly, we suggest that other studies analyze the role of cognitive distortions differentiated by typology. It is possible that, depending on the type of distortion that is activated, there may be different effects on women’s decision-making. Specifically, previous literature (Badenes-Sastre et al., Reference Badenes-Sastre, Medinilla-Tena, Spencer and Expósito2025) has highlighted several key cognitive distortions, such as the minimization of violence, the normalization of IPV, hope for change, and self-blame, as factors that contribute to women staying in abusive relationships. For this reason, it is recommended to interpret these results with caution.

Practical Implications

Continued efforts are essential to address the obstacles that women encounter when making decisions about their intimate relationships, particularly in the context of IPV. The findings of this research highlight the need to address both sociocultural factors, such as adherence to the traditional female role, and individual factors, including dependency and cognitive distortions, which together create significant barriers to exiting violent relationships, with profound implications for women’s health and well-being. A reasonable approach to tackle this issue could be to implement psychoeducational programs from an early age that promote equality and healthy relationship models, aiming to prevent the normalization of IPV in future generations. Moreover, tailored awareness and training programs should be developed not only for victims of IPV but also for the general female population, to facilitate the identification of maladaptive cognitive patterns that can trap women in abusive dynamics.

Furthermore, it is crucial to equip women with tools to recognize and evaluate the severity and risks of IPV, considering the broader social and contextual factors. Ensuring accessible, comprehensive support systems and services for women who decide to leave abusive relationships is paramount to prevent relapse, which often results from reactivated cognitive distortions such as minimization of abuse or misattribution of responsibility.

Conclusion

Cognitive distortions could impact the decision to leave or maintain a violent relationship, especially in women involved in IPV. This study provides the first comprehensive assessment of the role of cognitive distortions in women’s decision-making, differentiating between those who currently suffer from IPV and those who do not. The results obtained have gone some way toward enhancing our understanding of women’s difficulty in making decisions about breaking away from violent relationships, as distortions of reality can arise that favor their continuance in these relationships. Likewise, the adherence to the traditional female role could enhance these cognitive distortions by reinforcing the idea that women are responsible for maintaining relationships, even if it is risky for them. Given the seriousness and complexity of IPV, more research is required to understand the mechanisms that make it difficult for women to perceive the reality of violence.

Data availability statement

Data would be available upon request via the corresponding author’s email: patmedten@ugr.es.

Author contribution

M. B.-S.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft and Writing—review & editing. P. M.-T.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft and Writing—review & editing. F. E.: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, and Visualization.

Acknowledgements

Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Granada / CBUA.

Funding statement

This work was supported by a research project “Violence against women: Implications for their psychosocial wellbeing” (grant) PID2021-123125OB-100 financed by the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ERDF, EU.

Competing interests

The authors of this article have no conflicts of interest. This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Granada (No.: 3328/CEIH/2021).