Chichilticale (variously spelled Chichilticalle, Chichiltiecally, Chichiltiqueale, Chichiltic calli, and other ways) has been the most sought-after location in present-day Arizona that was mentioned in documents pertaining to Coronado's expedition from 1539 to 1542. One reason for its “popularity” is that those pursuing the Coronado expedition route assumed that Chichilticale was the only place that would be found within the bounds of modern-day Arizona. Scholars expected that overnight encampments would only be found by chance, even though mobile group encampments related to the local Indigenous people are routinely found by those familiar with and experienced in that type of archaeology (see, for example, Adams et al. Reference Adams, White and Johnson2000a, Reference Adams, White and Johnson2000b; Brugge Reference Brugge and Seymour2012; Pilles Reference Pilles and Seymour2017; Seymour Reference Seymour and Purcell2008, Reference Seymour2009a, Reference Seymour2009b, Reference Seymour2009c, Reference Seymour and Seymour2012a, Reference Seymour2013, Reference Seymour2015a, Reference Seymour2016). That has been my life's work, as it has been for a handful of others. If overnight encampments by small, material-culture-impoverished Indigenous groups could be found, surely overnight encampments by foreigners bearing unusual and durable artifacts and traveling in sizable groups with shoed horses could be located.

Another reason why Chichilticale has been sought so often is that it was a “place” that the expedition traveled to more than once; thus, it was long thought that there would be an increased chance of finding evidence of the expedition there. Fray Marcos de Niza may have traveled through it or stayed there in the spring of 1539, according to Pedro de Castañeda de Nájera (Relación de la jornada de Cíbola: Donde se trata de aquellos poblados y ritos y costumbres, la quel fué el año de 1540, compuesta por Pedro de Castañeda de Nágera, Case 12, Rich Collection 63, Nuevo Mexico; Sevella, 1596, 157n11, quarto bound; Manuscripts and Archives Division, MssCol 2570, No. 63, New York Public Library, New York). Melchior Díaz and Juan de Zaldívar stayed there for about two months during the winter of 1539–1540 (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:235, 391). Francisco Vázquez de Coronado mentioned he stayed there a couple of days to rest the horses as the advanced guard moved across the terrain (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:256). And, as will be discussed, the main body of the expedition likely stayed there as well, if Castañeda's disappointment with “seeing” the ruined roofless house is an actual indication. Consequently, historians have assumed that this would be one of the few, if not the only, place in Arizona where European use was sufficiently persistent or intensive that evidence of the Coronado expedition might be found. Yet, our discovery of 12 Coronado period sites in Arizona between Nogales and the Gila River over the past four years demonstrates that this assumption about the inability to find camp sites is ill-founded. Archaeologists’ experience in following trails and in documenting mobile adaptations demonstrates that we can and do find such sites on a routine basis. Finding the Coronado expedition trail and campsites is no doubt a challenging problem because the trail traversed such a narrow corridor, or corridors, throughout a vast expanse, and the documentary record often confuses the issues. Examples of the latter include when multiple chroniclers describe a named place in noncongruent ways, provide seemingly sequential commentary on trail segments that are non-isomorphic, or convey ostensibly contradictory understandings of what is presumed to be the same place.

The name “Chichilticale” was mentioned repeatedly in documents, which has heightened its importance as well. Several expedition members, including Melchior Díaz, Juan de Zaldívar, Pedro de Castañeda de Nájera, Juan Jaramillo, and Francisco Vázquez de Coronado y Luján, referred to this place. It was also one of the few named places along the trail in southern Arizona; before the discovery of the townsite of San Geronimo III in the Suya Valley (aka Santa Cruz Valley), it was the only named place thought to be in southern Arizona. It was a consistent stopover and milestone on the route northward. Chichilticale was mentioned so often because several events and geographic markers important to the expedition's advance along the trail happened and were situated there, including a change in vegetation or biome from Sonoran/Chihuahuan Desert to grasslands, settled to unsettled zones, and so on. Moreover, documentary content indicates that Chichilticale was perceived as many different entities, including a ruin, a province, a pass, a mountain range, a port, and the edge of the wilderness. It was also identified as the spring camp of Fray Marcos, Díaz's winter camp, at least one occupied Sobaipuri-O'odham village, and perhaps the river and valley in part or as a whole.

Although Chichilticale represents all these landscape and cultural features, it is not generally understood to occupy more than a single location. Data suggest, however, that the various historical conceptions of Chichilticale may cover or occur across an expanse of many miles. The conflation of each of the Chichilticale representations, as conveyed by different chroniclers, has hindered the ability of researchers to determine the location(s) of Chichilticale. The number of referents makes this four-dimensional puzzle, as Charles Haecker (personal communication 2022) characterized it, of reconstructing the route even more complex. The problem has many discrete parts that must be analyzed in relation to one another while at the same time being considered independently, each with its own lines of evidence. Repeatedly retranslating and deconstructing the narrative passages from expeditionary members at each stage of the investigation raised expectations that each of the elements important to the problem could be understood.

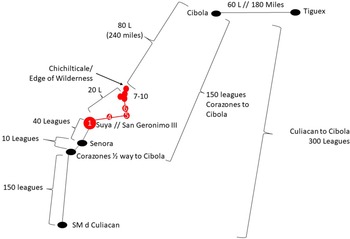

Furthermore, each aspect of the Chichilticale riddle had to be considered in the context of what we knew about the route trajectory to that point. What had already been discovered could be used to explore various route options and encampment locations as we pushed the projection of the trail ever farther to the north and northeast. Locating each existing trail segment represents weeks of fieldwork, probing, reconsidering, searching again, reformulating, and then breakthrough. We know a lot more than even four years ago: we now understand that the known route traverses a very different corridor than was previously argued (Figure 1). This new information changes many of the underlying assumptions and creates a series of heretofore unexplored evidential chains that that can be linked and relinked as hypotheses are investigated and either rejected or adopted (see Seymour Reference Seymour and Seymour2012a, Reference Seymour2014, Reference Seymour, Orser, Zarankin, Funari, Lawrence and Symonds2020a). The geographic considerations of the trail and Chichilticale can now be analyzed based on information on the location of recently documented and verified Coronado expedition archaeological sites.

Figure 1. General placement of the Coronado route through southern Arizona between San Geronimo III/Suya and Chichilticale. Image by Deni Seymour.

Previously, geography was used along with and similarly to narrative texts, as forms of data whose meanings were largely self-evident; after considered analysis and field checking, these data could be mapped on the ground to affirm the preferred route. The current exercise of reassessing both geography and narrative texts from the standpoint of emerging archaeological discoveries, until all the puzzle pieces fit, allows us to see more clearly the meaning behind the chroniclers’ words committed to paper as they relate to Chichilticale. This opens analysis to unexpectedly rich levels of interpretation.

In this article I discuss breakthroughs regarding several aspects of the Chichilticale conundrum and identify the ruined roofless house, Díaz's camp, Coronado's possible camp, the river crossing and the crossing into the wilderness, the mountain range, and the province. The pass remains to be identified at this writing. I do not address the port because it is several days’ distant from the area discussed. Importantly, the research is still underway, so more refined understandings will follow.

Background

The Coronado expedition was led by Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, who was assigned this role by Antonio de Mendoza, the first viceroy of Nueva España. It began with a reconnaissance mission by the Franciscan friar Marcos de Niza and the Black Moor Esteban. They traveled through southern Arizona in the spring of 1539. Esteban was one of four survivors of the Pánfilo de Narváez expedition in Florida. It is for this reason that he was sought to lead the way northward, along a portion of the trail the survivors had taken southward on their trek from Florida to Nueva España in 1536. In addition to Esteban, a “great multitude” of native porters, servants, and interpreters from what is now western and central Mexico went along on this first journey (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2019:83). Yet, something was amiss in the friar's reports or in conversations that alerted the viceroy to the need to verify the observations. Thus, as the rest of the expedition gathered in Compostela, Melchior Díaz, alcalde mayor of Culiacán, and Captain Juan de Zaldívar were sent ahead of Coronado to verify Fray Marcos's accounts of the region. They arrived with 16 horsemen and their support organization in mid-December 1539 and stayed at Chichilticale for around two months. It was expected that with all the horses, weapons, and number of participants that evidence of Díaz's presence would be seen.

As Díaz was returning with his company to the south to report the bleak outlook, 29-year-old Francisco Vázquez, typically referred to as Coronado, was already on his way north, and they encountered one another at Chiametla (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:391). Coronado led nearly 400 Europeans, as many as 2,000 Indigenous Mexican warriors, and an unrecorded number of support people, including slaves, domestic servants, interpreters, and guides. Because of the large size of his expedition, estimated to be around 2,800 people in total from San Miguel de Culiacán, Coronado went ahead with about 50 or 75 horsemen and 30 footmen as part of the advanced guard (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:291, 392). He had with him perhaps 600 or 700 support people and “Indios Amigos” (friendly Indians). The main body of the expedition followed behind with 1,100 horses and thousands of head of livestock, including cattle, pigs, sheep, and rams. They left Compostela in February 1540 (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:235). The expedition into Tierra Nueva lasted for around three years, after which they withdrew in April 1542.

In accounts of the northbound journey, Chichilticale is referred to more than other places, with the exceptions of Cíbola and the various versions of San Geronimo/Corazones. In the one surviving of the two reconnaissance reports, Marcos did not mention the name Chichilticale, but he did describe being among the extensive populations of settled people there, and Castañeda later stated that Marcos was there. Although in his correspondence Díaz did not name where he stayed, Zaldívar and Castañeda reported that Díaz and Zaldívar encamped at Chichilticale for what is estimated to be two months in the winter of 1539–1540. During the main expedition it was considered a waystation along the route, a place to regroup before heading into the wilderness (also see Ivey et al. Reference Ivey, Rhodes and Sanchez1991:56). Juan Jaramillo, who accompanied the advance guard and later wrote one of the two most detailed accounts of the trip north, referred to it briefly. In a letter to the viceroy, Coronado indicated that he rested there for two days. Castañeda, who was with the main body of the expedition that trailed months behind, prepared the longest and most information-rich account many years later. He implied that they went to Chichilticale along the route and stated clearly that others had been there. Finally, as the expedition was returning, they were met two days down trail from Chichilticale by Captain Juan Gallego, who had traveled from Mexico City via Culiacán with relief supplies and men; they discussed the possibility of establishing another town (that would have been San Geronimo IV) in the area.

Basic Understandings

Before 2020 no verifiable Coronado expedition sites had been identified in Arizona. One site was known in Texas—the Jimmy Owens Site—having been discovered by an amateur historian and subsequently professionally investigated (Blakeslee and Blaine Reference Blakeslee, Blaine, Flint and Flint2003). Coronado expedition sites were verified in the Albuquerque/Bernalillo area in New Mexico, including battlegrounds (Mathers Reference Mathers, Flint and Flint2011, Reference Mathers2020; Schmader Reference Schmader, Douglass and Graves2017, Reference Schmader, Moreira, Derderian and Bissonnette2019) and an encampment identified on the West Mesa during road construction (Railey Reference Railey2007; Schmader and Vierra Reference Schmader, Vierra, Brown, Barbour, Boyer and Head2021; Vierra Reference Vierra1989, Reference Vierra, Vierra and Gualtieri1992). The 1540 battle mentioned in documentary accounts has been investigated at Hawikuh at Zuni, New Mexico, the place known then as Cíbola (Damp Reference Damp2005). More recently, a possible Coronado presence has been suggested at El Morro, east of Zuni (Mathers and Haecker Reference Mathers and Haecker2009). Yet, no expedition sites were known south of Zuni: an area spanning 1,500 miles between where the Spaniards set off (from the farthest-north Spanish settlement in San Miguel de Culiacán, Sinaloa) and their initial destination at Cíbola/Zuni. Although amateur historian Nugent Brasher (Reference Brasher2007, Reference Brasher2009) claimed that the Kuykendall Ruin was the Coronado expedition site of Chichilticale, participating archaeologists at the time argued—and have since shown—that it is a later Spanish period site (over a prehistoric ruin) that is not related to the Coronado expedition: no authentic artifacts diagnostic of the expedition period were found there (Seymour Reference Seymour2022a).Footnote 1 No one before Brasher had claimed to have found a Coronado expedition site in Arizona (or anywhere down trail from Cíbola), much less Chichilticale, although there has been considerable speculation as to where it might have been (e.g., Bolton Reference Bolton1949:88; Duffen and Hartmann Reference Duffen, William K., Flint and Flint1997; Hartmann Reference Hartmann, Flint and Flint2011; Haury Reference Haury1984; Nallino Reference Nallino2014; Potter Reference Potter1908; Riley Reference Riley and Lange1985).

The first genuine Coronado expedition site found in Arizona in 2020 has since been interpreted as the townsite of San Geronimo III in the Suya Valley (Seymour Reference Seymour2025a).Footnote 2 This villa (town) provided a geographic anchor for knowledge about the trail, which has since led to the discovery of additional Coronado expedition sites. Only a subset of the 12 Coronado expedition sites in Arizona are described here. The objective of this article is not to discuss the route or routes themselves but their implications for understanding Chichilticale. In the interest of brevity, just enough of the site descriptions and information are be provided to establish the argument. Other aspects will be discussed in forthcoming publications.

Ten of the 12 known Coronado expedition sites in Arizona are along one trail alignment between Nogales and the Gila River (Figure 2). The two exceptions in Arizona are in the San Bernardino Valley in Cochise County, Arizona (Seymour Reference Seymour2023a). A possible third trail alignment north, indicated by metal Spanish period artifacts and a chronometric date consistent with the Coronado period, may represent that taken by Fray Marcos, but its association with the expedition is still being verified. If nothing else, the inference that at least two route corridors and perhaps a third are in southeastern Arizona demonstrates the complexity inherent in attempting to trace the route using archaeological evidence.

Figure 2. Approximate route of the expedition based on known Coronado expedition site distributions, including what is probably a second route in the San Bernardino Valley. Image by Deni Seymour.

The problem is compounded when considering the many forays into areas surrounding San Geronimo III, including their mining operations, resource procurement, and ranching. In addition, artifacts were clearly dispersed across the landscape by native residents, the Sobaipuri O'odham, Jocome, and Apache. They would have found and removed horseshoes and nails lost or left on the trail. They also attacked and plundered the townsite of San Geronimo III and the encampment at Chichilticale. They received items in trade and as payment and dispersed items through trade, ritual caching, burial, and repurposing. Tracing the route also requires looking in areas where the trail is not expected to be and then ruling those out as alternative routes, as is being done on the upper San Pedro River, the upper Santa Cruz River, along the Gila River, and elsewhere. This time-consuming effort will continue for some time but is essential for narrowing the corridors of travel.

Most past efforts to identify the exact route of this expedition have relied largely on documentary and geographic evidence. Using those types of evidence, without considering archaeological evidence specific to the Coronado expedition, produces a potentially infinite number of viable options for the course of the trail. This is clearly apparent in the number of hypotheses proposed over the years both for the route and the placement of Chichilticale. Thus, it becomes a matter of scholarly authority as to which route was favored. This is what occurred when the Coronado National Memorial by the National Park Service was established based on the consensus derived from documentary and geographic evidence alone (Ivey et al. Reference Ivey, Rhodes and Sanchez1991; Sánchez et al. Reference Sánchez, Érickson and Gurulé2001). This privileging of authority, in turn, accounts for the stalwart resistance to new evidence and interpretations regarding new route suggestions. Yet, archaeological evidence of Coronado artifacts and features—when used in a way that is consistent with basic scholarly precepts—anchors the route to specific places on the ground.

Importantly, artifact evidence must include a select range of items that can be narrowed temporally to this 1539–1542 period (Seymour Reference Seymour2022a). In Arizona, the set of diagnostic artifacts are defined as those occurring any time before the mid to late 1600s because Europeans did not return to Arizona in any large number until later (Seymour Reference Seymour2022a). This provides a broader range of items to define the presence of this expedition than might be useful in New Mexico, where several other expeditions occurred before 1600. A limited range of artifacts are expected to be found in Coronado expedition (and, in the Southeast, Soto expedition) sites that do not also occur later. These are artifacts that can be shown to be limited to the 1539–1542 period or earlier, rather than to the longer Spanish period that ends in the early 1800s. In Arizona, these artifacts are found before the 1690s when Jesuit missionaries and Spanish military men entered the scene: copper and iron crossbow bolt heads; caret-head (aka gable-headed or bifaceted) nails; copper lace aglets; copper hawk, harness, and anquera (rump cover) bells; Venetian beads; green obsidian and native-made ceramics from Mexican sources; chain mail and plate and scale armor along with helmets (such as the cabasset and sallet); and their pieces (such as rosettes and rivets), breast plates, and pauldrons. These specific artifacts are described in detail in a video (Seymour Reference Seymour2022a), and the basis for these associations is presented in other sources for both the Coronado and Soto expeditions (Blanton Reference Blanton2020; Brecheisen Reference Brecheisen, Flint and Flint2003; Deagan Reference Deagan1987, Reference Deagan2002; Ewen and Hann Reference Ewen and Hann1998; Gagne Reference Gagne, Flint and Flint2003; Mathers Reference Mathers2020; Worth et al. Reference Worth, Benchley, Lloyd and Melcher2020).

My current research enables the additional inclusion of artifacts that did not go out of use immediately after the expedition but that were no longer manufactured or in use after or shortly after the turn of the seventeenth century, AD 1600. These artifacts include medieval-style horseshoes, bronze wall guns or cannons, Roman nails, Early Ming-period Chinese porcelain, and, with caveats, matchlock and wheellock gun parts. In addition, an impressive variety of iron and copper arrow, atlatl dart, crossbow, and lance heads have been added to the growing list of items that are distinctive of this period in southern Arizona (Seymour Reference Seymour2025b). Consideration must also be given to the long life of heirlooms, the extended duration of repurposed items in later social contexts, and the rediscovery of earlier items that were then incorporated into later contexts. Most helmets and breastplate discoveries seem to be from Native American caches that are not necessarily indicative of the trail route itself. This is one element of the multifarious and dynamic predictive model that will be presented when the route trajectory is completed, artifact analysis is concluded, and site protections have been fully considered.

This current work demonstrates the importance of applying archaeological solutions to the route question and interweaving them with documentary, geographic, and other types of evidence. Artifact and feature evidence of Coronado expedition camp sites and the route path provides a firm basis for interpreting documentary content and assessing geographic factors. Surprising interpretations arise when using all available lines of evidence to reconstruct the trail in the context of the rules of evidence, methodological standards, and theoretical underpinnings of the discipline. It is no wonder that the trail has not been defined previously, given the unexpected nature and location of the evidence and the depth of location- and discipline-specific knowledge and facility required to solve this problem. It is because of the unexpected nature of these findings that it is necessary to walk through the analytical, predictive, and search processes before discussing the characteristics of the site and their relevance to interpretations of the expedition, including implications for the local native population of Sobaipuri O'odham. This last point brings to the fore the larger implications of this research and its importance to descendant populations, including the O'odham and the Apache/Ndé (Seymour Reference Seymour2024). Their interest and engagement in this research underscore the importance of establishing the route and named places that bisected their homelands and entangled their ancestors in the web of history at first European contact in this region.

About Documents and Archaeology

It is no surprise that the addition of archaeological evidence allows us to derive another level of inference from documentary sources. Using our own personal interpretive filters, without recognizing their limitations, can skew the ways documentary content is understood. It is first necessary to contemplate the actual content of the documents, consider alternate meanings of phrases and words, and understand when there is a lack of clarity. In some instances, knowledge of the geographic area or other factors can clarify which of the possible meanings is likely correct. When a Coronado-specific site is found based on those assumptions, one can be confident in that interpretation.

Practice has shown that it is useful to repeatedly reread the relevant portions of the texts to ensure they are transmitted to one's memory correctly. (More often than not, the most stalwart objections come from people who misremembered the translations or used translations that had not been updated.) Each time a new hypothesis is considered or a new Coronado-expedition-specific site is found, engaging in this process of rereading, retranslating, and reconsidering alternative meanings is of value. For this reason, transcriptions and translations of the original (primary) expedition-related documents are cited liberally throughout this article so that readers can see the specific basis for interpretations.

Most people do not realize how much of the translation process is interpretation (Harlan Reference Harlan2007). Choosing one meaning when many different definitions are possible is one layer of difficulty. Another is that the meanings of words have changed through the years, and it is a time-consuming process to discover and consider every meaning. Moreover, just as today, writers then were not necessarily especially effective in conveying their thoughts, and in many instances, they assumed the reader would know the subject of their passage. The shift between subjects may not be immediately apparent and can be as convoluted as the trail itself. Errors were sometimes made that must be assessed, including, for example, the way San Geronimo in its various forms is referred to over time. Differences in perception of the landscape among chroniclers and through time and across cultures are another consideration I discussed earlier (Seymour Reference Seymour2014:99–104).

An effectively implemented research design requires a dynamic evaluative and analytical process. Flexibility in the way the questions are posed and reformulated is essential. Reconsideration of the nature of the specific data required at each stage is as important as pliancy in implementing the reconnaissance trajectory and in revising the search parameters and perimeter (which can be difficult if permit and permission requirements limit the search zone). Workable hypotheses are tested by laying out an explicit area to probe, then retreating to the known site and considering an alternative route until success is achieved. The same process applies to retreating to the written passage and retranslating or considering other meanings and incorporating other possible interpretations. Using the text as an artifact—and accepting that texts are cultural artifacts that may convey many different meanings—demands they be assessed within their own cultural framework.

Effective interpretation requires deconstructing each passage of the documentary record that pertains to the physical, spatial, and material aspects of each segment of the trail (see Seymour Reference Seymour and Seymour2012a, Reference Seymour2014, Reference Seymour2020b). This involves descriptive (Leone and Potter Reference Leone, Potter, Leone and Potter1988:14) or correlate grids (Seymour Reference Seymour and Seymour2012a, Reference Seymour2014, Reference Seymour, Orser, Zarankin, Funari, Lawrence and Symonds2020a) and then tacking back and forth between evidence to establish interpretations (Wylie Reference Wylie, Yoffee and Sherratt1993). It is best done for each trail segment.

Understanding which part of the trail is being referred to in each of the documents is also part of the inferential challenge. Importantly, the accounts are not isomorphic: chroniclers did not always refer to the same places when mentioning specific place names, as is apparent in references to Chichilticale. In addition, the next place mentioned is not always the same in each of the accounts, so a consistent sequence of events cannot be assumed. For example, there are differences between Coronado's and Jaramillo's discussions of their progression along the route. Although they were both part of the advance guard, it seems that Jaramillo went ahead, encountering the Gila River on San Juan Day when Coronado had just left Chichilticale the night before.

Following Charles Hudson (Reference Hudson and Galloway2006:322), I previously suggested that, as expedition members sat around the nighttime fires, they probably discussed aspects of their experiences that coalesced into an expedition narrative (Seymour Reference Seymour2009a:409). This may have happened during the Coronado expedition, especially within a company traveling together: these discussions seem evident in some of the legal documents where the statements appear rehearsed or committed to memory through repetition (see testimony in, for example, Flint Reference Flint2002). Yet, there were so many different expedition-related groups, traveling at different times, that several different understandings formed. This should perhaps not be unexpected, given that some accounts were written decades later, years after hearing the stories at social gatherings and in political, social, and legal settings. In fact, some of the place names may have been assigned after the expedition ended. This may have been the case with the term Ispa, La Ispa, or La'aspa (perhaps meaning trap or ambush in O'odham), mentioned only by one chronicler.Footnote 3 It may be an O'odham word that incorporated knowledge about the outcome of a battle, thus including information about a later battle in a narrative account about earlier travels. The assumption that the entire expedition saw the landscape and its occupants in a singular way impedes understanding of the meaning contained in each account: this is especially relevant to this discussion of the places called Chichilticale.

Differences in understanding held by expedition members are also expressed in the way and speed at which they traveled across the landscape. For example, the number of days or league distances is not commensurate between accounts. It seems that the advance guard or, at least, Jaramillo was traveling twice as fast as the main body that had all the livestock and included Castañeda. By the time Castañeda passed through the area, the landscape had already been traveled and was partially understood, had probably even been painted by expedition artists, and the routes had been modified accordingly. This accumulation of route and landscape knowledge seems to be reflected in Castañeda's account. Castañeda was with the main body; apparently, he understood certain places differently than did those who had traveled before him. His conception of Chichilticale as a ruined roofless house differs from Jaramillo's understanding of Chichilticale as a mountain range and pass, which he or his associates heard directly from the local natives.

It also is beginning to seem likely that Marcos de Niza took a different route north through portions of Arizona than did Coronado and Jaramillo, with the split occurring at Chichilticale (the province). Díaz may have followed Fray Marcos's route until he reached Chichilticale (the ruin and province) where he was stopped by winter weather. The main body of the expedition may have followed an adjusted or partially modified route as well (through the province and the pass), immediately crossing the river—as might have Pedro de Tovar as he led half the residents of San Geronimo along an even different, more southern route north to the Tiguex province in mid-1541 (Seymour Reference Seymour2023a). Further research may tell.

Without external evidence such as provided by archaeological data, we cannot possibly consider and select from among all the possible permutations and interpretations of a passage written 500 years ago by and about people of different and unfamiliar cultural backgrounds. They did not take the straightest route nor the one with the most accessible water. They did not initially have the knowledge of the entire landscape to make these decisions but rather were being guided and sometimes misguided. Thus, we need more than “careful consideration” of geographic and documentary data to solve this mystery, just as it is no longer sufficient for a researcher to reject one hypothesis while “declaring himself in favor” of an alternative, as historians and geographers have done in the past (e.g., see discussions in Sánchez et al. Reference Sánchez, Érickson and Gurulé2001:59; Sauer Reference Sauer1932; Undreiner Reference Undreiner1947:436). A basis for grasping and engaging in the many twists and turns in logic and interpretation required to solve the puzzle becomes obvious once on the ground and facing many options that would lead the trail to veer hundreds of miles in different directions. Being even a half-mile off-course (or even less) is problematic from the standpoint of finding tangible evidence.

New perceptions of the route and the landscape become available when an actual expedition site is found, just as new understandings of the impacts and shape of these encounters can be gleaned when these sites themselves are studied. Importantly, most researchers who have written about the route got at least one part of the equation correct, as seen in the many citations that follow. Yet, these many interpretations only advance the study of this problem so far. They have not identified the actual verifiable route, something that can only be done with archaeological proof that is carefully rendered within an appropriate interpretive framework. New external sources of inspiration are also required that extend our interpretive capacity. As new, externally derived insight is accessed, new interpretive possibilities are exposed. It is in actively seeking other possible, previously unconceived interpretations that new and surprising sources of alternative interpretations can be grasped, sometimes during only a momentary flash of insight.

Understanding the historical environment and native populations at the points and times of contact gained from four decades of research in these specific areas provides an advantage in reassessing interpretations of the route. This ongoing thematic research has modified reconstructions of the sequence and character of occupation by the Sobaipuri O'odham, Jocome, and ancestral Apache (Seymour Reference Seymour1990, Reference Seymour2009a, Reference Seymour2009b, Reference Seymour2011a, Reference Seymour2011b, Reference Seymour and Seymour2012a, Reference Seymour2016, Reference Seymour2020c, Reference Seymour2022b). Adjustments to understandings of river flow, arroyo formation, and vegetative distributions through historical investigations provide keys that have been crucial for determining the often convoluted nature of the expedition trail (Seymour Reference Seymour2020b, Reference Seymour2022b; Seymour and Rodriguez Reference Seymour and Rodriguez2020). The fruits of this cumulative field research become apparent when coupled with fresh translations and new interpretations of the meaning of documentary sources in the context of the new archaeological evidence at Coronado expedition sites along the trail alignment. The now-routine discovery of new Coronado expedition camp sites is an indication of the reliability of these interpretations.

Perceptions and Predictions

Deeply entrenched preconceived notions about the archaeology (cultural sequence and character) and environment of southeastern Arizona have limited the ability of earlier researchers to perceive the landscape in a way similar to how expedition members did and thereby to understand their narrative accounts. In turn, conventional wisdom has restricted our ability to make full use of documentary content. Given that the accounts do not seem to be isomorphic, it is necessary to contextualize each passage that has relevant spatial, temporal, geographic, and material correlates (see Seymour Reference Seymour2009a, Reference Seymour and Seymour2012a, Reference Seymour2014:97–104). This must be done with the information learned about this region through decades of focused research. The importance of this information cannot be overstated because pushback about the route is so often embedded in outdated notions about these facts. It is also important not to assume that one narrative account is a straightforward extension of another. Some readers may think I am entirely off course. Yet, I have identified 12 definitive Coronado expedition sites, even though, at the beginning of 2020, not a single verifiable Coronado expedition site had been found in Arizona.Footnote 4

If we can understand what expedition members were perceiving with respect to the landscape and its occupants, we can then find their camps and establish the route. This means understanding the changing historical use and character of each trail segment. Each passage must necessarily be analyzed for all its potential and conceivable implications, and then each of those potential implications must be explored using evidence in the archaeological record (Seymour Reference Seymour2022c). I was guided by these basic premises as I extended the trail beyond the three sites I initially identified in the Santa Cruz and San Bernardino Valleys. A series of hypotheses about the environment, water sources, and Indigenous populations in relation to the route were then proposed and tested, reexamined, and then tested again.

My research plan incorporated this hard-won knowledge of the specific areas in question. The proposed reconstructions led to precise expectations for the types of data to be found. In turn, these expectations were the basis for accurate predictions about where the next Coronado expedition sites should occur. Through this process, Coronado expedition Sites 4–11 were found, including how the expedition approached the San Pedro River (Site 4)Footnote 5; where the expedition encountered the San Pedro River (Site 5); one location where the expedition crossed the river, presumably in June 1540 (Site 6); where the ruined roofless house was located in relation to a Coronado expedition encampment (Sites 7–10); and where Coronado and the advanced guard, including Jaramillo, camped and then crossed the river (Site 11). At Sites 7–10, identification of the exact ruin—among the four late prehistoric equivalents of ruined roofless houses in the vicinity of the trail—was substantiated by confirmation of a sizable Coronado expedition encampment at that ruin. In the context of the documentary record, this site with a ruin and Coronado expedition encampment (as indicated by artifacts, features, and chronometric dates) is interpreted as the site of Díaz's 1539–1540 winter camp, which was said to be at Chichilticale and presumably was where Fray Marcos, and perhaps Esteban days before him, had camped six or so months earlier.

Understandings Specific to the San Pedro Valley

Based on the content of the documentary record in relation to recently discovered Coronado expedition archaeological sites along the reconstructed trail, it was expected that Chichilticale and Díaz's two-month encampment would be situated along the San Pedro River. The documents also supported the inference that the area in the vicinity of the camp would have been inhabited by the Sobaipuri O'odham: they were the settled villagers at that time, living in permanent riverside settlements. Their year-round residences were situated along their canal and field infrastructure; through the years their villages would shift location up and down specific reaches of the valley. However, they were not mobile. The Jocome and ancestral Chiricahua Apache lived around them and to the east, but the Spaniards would have seen their mobile nature and would have considered them unsettled: this is why they would have called the area to the east and northeast a despoblado, or unsettled region (Seymour Reference Seymour and Purcell2008, Reference Seymour2009a).

The location of the places referred to in expedition texts as Chichilticale could also be determined using distance calculations found in textual passages. Another consideration was that the place called Chichilticale by Castañeda and that place called Chichilticale by Jaramillo might be in different locations and that none of the expedition camps might actually be at the ruined roofless house or the pass but would instead be in the general vicinity of one, the other, or both. Current claims for where these various Chichilticales might be located were based on (1) league distances provided between San Geronimo III/Suya and Chichilticale, (b) understandings about the edge of the thorny forest as it relates to known trail segments and recently revised knowledge of the historical environment, (c) the distributions of settled villagers in this part of southeastern Arizona in relation to the edge of the wilderness/despoblado, and (d) the distribution of late prehistoric ruins in areas “adjacent” to the known trail, particularly in relation to the ruined roofless house called Chichilticale.

Although it has been recognized that Chichilticale might refer to several different built and natural elements (Hartmann Reference Hartmann, Flint and Flint2011:199; Nallino Reference Nallino2014; Riley Reference Riley and Lange1985:153; Schroeder Reference Schroeder1955:294; Simpson Reference Simpson1869), few considered that that they would be in different places (also see Nallino Reference Nallino2014:10). Jaramillo conveyed a different understanding of Chichilticale than did Castañeda, and Díaz implied a third conception. Until now efforts to identify the ruin associated with the name Chichilticale were hindered by the assumption that it was located at or near the other places understood to be Chichilticale. For example, the ruin was thought by many to be near the pass, and under this assumption I spent considerable effort searching at the base of mountain ranges near passes. Díaz's winter encampment and Castañeda's ruined roofless house are in one and the same place—but it is not clear whether Castañeda actually saw the house or, even if he did, that he camped there, although he may have visited it. It seems that Díaz's winter encampment and the ruined roofless house are in different locations, respectively, from where Coronado and the advanced guard camped and from where Castañeda and the main body of the Coronado expedition camped. It is now established that there was likely more than one Chichilticale encampment. Complicating this issue is that other encampments would have been up and down the trail, some along the San Pedro, and they were not necessarily viewed as being Chichilticale—or perhaps all were.

It seems from Jaramillo's description and the archaeological evidence at Sites 6 and 11 that the advanced guard and the main body of the expedition may have taken a different route along and from the San Pedro River than did Díaz; perhaps they crossed the San Pedro almost immediately to avoid the Sobaipuri O'odham settlements. It is also possible that the Sobaipuri O'odham had moved away to avoid contact with these foreigners. Either one of these inferences may be supported by the fact that food could not be obtained from local residents when the advanced guard passed through, suggesting that the Sobaipuri O'odham were not friendly (after the battle with Díaz; see the discussion below) or that they were not settled in that immediate location. Coronado stated, “I rested for two days at Chichilticale, and there was good reason for staying longer, considering how tired the horses were; but there was no chance to rest further, because the food was giving out” (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:256). This was written on June 21–22, 1540, just before the mid-July harvest season. There might have been an expectation that food would be available at this location after Fray Marcos had noted the productivity of the land. Often this lack of food has been ascribed either to the lack of irrigation and crop productivity, to Coronado passing through too early in the growing season (e.g., Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:497, 690n35; Schroeder Reference Schroeder1955:272), or to a poor growing season (Antonio de Mendoza, letter to the king, Jacona, April 17, 1540, Archivo General de Indias [AGI], Sevilla, Patronato, 184, R.31; also see Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:235, 239). Perhaps Díaz and his company had already used up the local surplus. Yet, a seeming lack of produce or the excuse of a bad year may have been nothing more than a polite response by the Sobaipuri O'odham to the Spaniards’ unrelenting demand for food and other resources. The failure to offer provisions is almost certainly attributable to the hostility of the natives at this time. Importantly, however, Coronado does not say that the Spaniards asked or bargained for food here and were refused; he only said that their food was running out, consistent with a lack of contact with those who could provide those provisions.

Interestingly, Jaramillo's understanding of Chichilticale's location includes a mountain range, pass, or canyon area, or perhaps all three. He wrote, “Once we left the arroyo, we went to the right to the foot of the cordillera in two days of travel, where we were told it was called Chichilticale” (my translation; Relación del capitán Juan de Jaramillo de la entrada que hizo Francisco Vázquez, de Coronado a Cíbola ya Quivira, AGI, Patronato, Legajo 20, N.5, R.8). This hinterland or wilderness location of Jaramillo's Chichilticale is the reason Castañeda stated that the natives of Chichilticale were “the most barbaric people of those seen until then. They live in rancherías, without permanent settlements. They live by hunting” (my translation of Castañeda de Nájera, Relación de la jornada de Cíbola: Donde se trata de aquellos poblados y ritos y costumbres, la quel fué el año de 1540, compuesta por Pedro de Castañeda de Nágera. Case 12, Rich Collection 63, Nuevo Mexico, Sevella, 1596, 157n11, quarto bound; Manuscripts and Archives Division, MssCol 2570, No. 63, New York Public Library, New York). These were mobile people who lived beyond and around the settled farmers. If Jaramillo's statement is taken literally, given the geography and known distributions of native peoples at that time, it is reasonable to suggest that Chichilticale was pronounced as chích'il tū hálį̄į̄ and is an ancestral Apache term (see the video for pronunciation at Seymour Reference Seymour2023b). In the local Athabascan dialect it means “oaks,” “water flows out,” or “Oak Spring” (Willem de Reuse, personal communication 2023). One can imagine the following conversation months later between Castañeda and some of the native porters:

C: What did they say this was called?

Nahuatl speaker: Chichiltic calli.

C: What does that mean?

Nahuatl speaker: Red house.

The original conversation, however, was most likely in sign language and Athabascan, perhaps even in the Piman/O'odham language (the lingua franca for this region), with the actual Apache place name said out loud. So, the transmutation of this Apache term to a similar-sounding term in the Nahuatl language, which was familiar to the Indios Amigos (and others on the expedition), is a reasonable explanation for this place name. Elsewhere along the Coronado expedition route, local place names were used by the Spaniards to the degree that they were understood (examples include Tiguex = Tiwa, Acuco = Acoma, Chia = Zia); thus, there is no reason to believe that local place names were not used and incorporated along this portion of the route. In fact, the most parsimonious explanation is that it was a local place name. The reason why this origin and its meaning have not been considered previously is that scholars have assumed that the ancestral Apache did not arrive in this area until later. This misconception is clarified below.

As mentioned, the archaeological evidence suggests that the ruined roofless house, referred to by Castañeda as Chichilticale, was at the same place as Díaz's camp. His camp was at Chichilticale, according to statements by Juan de Zaldívar (Testimonio, 22 de agosto de 1544, Guadalajara, AGI, Justicia, Legajo 267 and Justicia, Legajo 1021, N. 2, Piezas 4 and 6; Flint Reference Flint2002:253–254; Castañeda de Nájera, Relación, Case 12, Rich Collection 63, Nuevo Mexico, Sevella, 1596, 157n11, quarto bound; Manuscripts and Archives Division, MssCol 2570, No. 63, New York Public Library, New York; Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:391). It is clear that Díaz was thinking of his location and its vicinity as Chichilticale, and so the Chichilticale province might be perceived in a way similar to how the Tiguex province referenced the Albuquerque/Bernalillo area. Based on the understanding that each of the chroniclers thought of Chichilticale as different things that were potentially in different locations, my expectations included the scenario that the ruined roofless house might simply be along the trail but that an expedition camp might not be at the ruin. Yet, as it turns out, a series of four related sites, inferred on the basis of new archaeological evidence to be Díaz's camp, are positioned at a ruined roofless house. This ruin, however, is in a different place from the location that Jaramillo called Chichilticale, and the ruined roofless house is probably not where Castañeda or Coronado camped when at Chichilticale.

Leagues between San Geronimo III and Chichilticale

The place or places designated by the Spaniards as Chichilticale were determined on a more general basis from archaeological knowledge of where Suya (aka San Geronimo III) was located. San Geronimo III in the Suya Valley was the first definitive Coronado expedition site discovered in Arizona: its location was unexpected because it was in a valley west of the San Pedro Valley, which most scholars thought the route would follow. Discovery of this named place anchored Suya to a firm geographic location from which other places mentioned in the documents, such as Chichilticale, could be calculated, albeit in a very general way. From this place, documentary content could be used to measure the approximate distances between this known place and other named or discussed places being sought. This was done in a general way using measurement tools in Google Earth. The relationship of Suya to Chichilticale was calculated based on league distances obtained through analysis of statements in the documents. The many passages that convey the league distance were analyzed, several of which are presented here and should be used with reference to Figure 3 (Castañeda de Nájera, Relación, Case 12, Rich Collection 63, Nuevo Mexico, Sevella, 1596, 157n11, quarto bound; Manuscripts and Archives Division, MssCol 2570, No. 63, New York Public Library, New York; Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:391, 388, 431):

They departed Culiacán and travelled as far as Chichilticale which is at the beginning of the unsettled region, 220 leagues from Culiacán.

Chichilticale which is at the beginning of the unsettled land. The unsettled area is 80 leagues across. From Culiacán to the beginning of the unsettled area there are 220 leagues plus the 80 that are the unsettled land (making it 300 ± 10).

[Gallego] traveled through that entire settled land [from Culiacán to Suya] in which he went 200 leagues.Footnote 6

Calculations used to arrive at the likely vicinity of Chichilticale were accomplished using a three-mile league,Footnote 7 which is borne out by other data. What is clear is that Chichilticale was 20 leagues from San Geronimo III in the Suya Valley (today's Santa Cruz Valley).

Figure 3. The documentary record provides surprisingly accurate league distances. Carefully analyzed, these distances were used as one line of evidence to locate Chichilticale. Image by Deni Seymour.

This effort to locate Chichilticale was aided by the fact that we now had a route trajectory from San Geronimo III/Suya to the east and northeast, based on the discovery of two additional Coronado sites (Sites 4 and 5) along this northern route at that time the calculation was undertaken along this specific route trajectory.Footnote 8 The route trajectory provided a directional aspect for distance measurements. Accordingly, distances and approximate bearings could be gleaned using documentary content in combination with the location of down-trail expedition sites. This contrasts with Potter's (Reference Potter1908:270) assertion that “nothing positive can be deduced from the distances or bearings, though it is remarkable how every such effort points to the zone line south of the Gila River.” That problem was true when using either documentary or geographic content alone, but the emerging alignment of the trail based on archaeological data provided essential information that guided the search for the next sites. With a general distance and a bracketed directional range, I was then able to place Chichilticale along the river in the San Pedro Valley and perhaps at the foot of the Dragoon Mountains or a related set of mountains.

Thorny Forest

The importance of this reconstruction based on the league distance between two places named in the documents (Suya and Chichilticale) is that other data then aligned with the inference that these were the place(s) called Chichilticale. This exercise indicated that the San Pedro Valley was pertinent to the placement of Chichilticale and that both Chichilticale and the San Pedro were at the edge of the thorny forest. The Sonoran Desert ends in this area, as does the Chihuahuan Desert, along the San Pedro River. Once passing the Dragoon Mountains, the landscape is dominated by grasslands. Many readers will argue that the geologic terraces along the San Pedro were once also characterized by grasslands, but this is inaccurate. The area includes silty relict lake deposits and rocky Pleistocene terraces with shallow soils, with an underlay of caliche and conglomerate that favor vegetative communities other than grasslands. Coronado expedition documents, as well as those of later historic explorers and residents, provide evidence that the grassland model is outdated and likely relates, as I have said elsewhere, to a degraded late nineteenth-century environment that was projected back in time. Even the 1775–1780 Santa Cruz de Terrenate Presidio soldiers were required to graze their horses at some distance from the river (Seymour and Rodriguez Reference Seymour and Rodriguez2020).

The misconception of a river-long marsh is also based on inappropriate assessments of historical documents. All the rivers in southeastern Arizona share the characteristic of river flow submerging underground and then emerging at bedrock constrictions and where the water table intersects with the surface (Seymour Reference Seymour2011a, Reference Seymour2020b, Reference Seymour2022b; Seymour and Rodriguez Reference Seymour and Rodriguez2020). Consequently, except for seasonally during the monsoon storms, a good part of the river channel is and was dry, except in the few areas where water was reliably on the surface. Those few areas are where Sobaipuri O'odham villages were located and also where trails converged. Travelers also tended to use specific crossings to avoid the marshes upstream from the constrictions and the quicksand. Numerous publications address these early observations and conditions confronting residents and travelers and how the historic record has been inappropriately used and restricted to a too-shallow period to reconstruct environmental history in this area (Seymour Reference Seymour2020b, Reference Seymour2022b; Seymour and Rodriguez Reference Seymour and Rodriguez2020).

Regarding the change in vegetative biome, Castañeda noted that he and his men passed from the thorny forest: “At Chichilticale the land again forms a boundary, and the spiny forest disappears. That is because the gulf reaches about as far as that place [and then] the coast turns and the mountain chain turns likewise. There one finally crosses the mountainous land, [which] is broken to permit passage to the land's region of plains” (Castañeda de Nájera, Relación; Case 12, Rich Collection 63, Nuevo Mexico; Sevella, 1596; 157n11, quarto bound; Manuscripts and Archives Division, MssCol 2570, No. 63, New York Public Library, New York; also see Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:417).

Castañeda also tells us that the thorny forest began at Petlatlán (see also Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:416), which is in Sinaloa, Mexico. What he was describing was the Sonoran Desert. In the San Pedro Valley, the Sonoran Desert grades into the Chihuahuan Desert and the uplands before transitioning into the grasslands. It does this today, and it did so in the past, because of elevation, soils, and other factors. The grassland and oak forest at the foothills of the Dragoon Mountains represent a gradation as one travels east and increases in elevation (see video, Seymour Reference Seymour2023c).

Despoblado, Edge of the Wilderness, and Settled Villagers

The Sobaipuri O'odham who resided along the San Pedro River when the Coronado expedition arrived were at the edge of the “wilderness,” unsettled land, or despobla do, in this early historic period.Footnote 9 This is stated in expedition-related documents and has also been verified by archaeological evidence:

Because the general had traversed the populated land and arrived at Chichilticale, [which is at the] beginning of the unsettled land, and saw nothing worthwhile, he did not fail to feel some distress [Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:393].

He [Esteban] got so far ahead of the friars [sic] that when they reached Chichilticale, which is [at] the beginning of the unsettled land, he was already in Cíbola [Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:388].

[Díaz and Zaldívar] departed and traveled as far as Chichilticale, which is at the beginning of the unsettled region two hundred and twenty leagues from Culiacan, and they found nothing of worth [Castañeda in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:391].

Extensive archaeological data indicate that the San Pedro Valley was the edge of settled village life at that time (Seymour Reference Seymour2011a, Reference Seymour2022b). Earlier there were Salado/Western Pueblo and Trincheras settlements along the San Pedro and to the east inhabited by late prehistoric peoples whose substantial settlements were distinguished by adobe-and-stone pueblos. These culture groups converged along this river valley, comprising a diverse cultural landscape. They then retreated, probably under Sobaipuri O'odham pressure in the late 1200s or early 1300s (Harlan and Seymour Reference Harlan, Seymour and Seymour2017; Seymour Reference Seymour2011a). But by the time the Coronado expedition came through, no one lived in settled villages to the east of or to the immediate north of the San Pedro Valley. This was not to say that people did not live there: everything to the east and to the north was occupied by mobile, hunting-and-gathering people—the ancestral Chiricahua Apache, the Jocome, and others—whose presence has been dated in the San Pedro Valley to the late 1200s. We know this from decades of archaeological research, including chronometric dating of dozens of sites (Seymour Reference Seymour and Purcell2008, Reference Seymour2009a, Reference Seymour and Seymour2012a, Reference Seymour2012b, Reference Seymour2013, Reference Seymour2016). So, all three of these groups—the ancestral Chiricahua Apache, the Jocome, and the Sobaipuri O'odham—were present in this area long before the Coronado expedition came through. This is important because the area to the east was not devoid of population; it is just that the Spaniards did not perceive the area used by these mobile groups as settled, and so they referred to the area where they resided as unpopulated or unsettled (despoblado; Seymour Reference Seymour and Purcell2008, Reference Seymour2009a). Importantly, too, Jaramillo's account accurately conveys that the four-day despoblado before the Nexpa was inhabited by small groups of Indians who “came out to see the general with gift[s] of little value, some roasted maguey stalks and pitahayas” (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:513). These were likely Jocome, although they could have been ancestral Apache, who occupied the areas not claimed by the settled, farming Sobaipuri O'odham (Seymour Reference Seymour2009a). These territories were not exclusive. Nonriverine areas and riverine areas outside Sobaipuri O'odham communities were frequented by these mobile peoples who, based on archaeological evidence, established camps throughout the area. Some of these encampments have been identified on abandoned Sobaipuri O'odham village sites and at one of the Chichilticale loci (Seymour Reference Seymour2011b, Reference Seymour2015b, Reference Seymour2016, Reference Seymour2022b).

Thus, the start of the great 15-day despoblado was just beyond the San Pedro River Valley.Footnote 10 The San Pedro represented the divide between settled and unsettled areas. To the east were mobile groups; that is, hunters and gatherers. On the San Pedro were the Sobaipuri O'odham who lived in permanent settlements. The hunters and gatherers used the San Pedro and areas to the west as well, but the Sobaipuri O'odham did not live to the east or north because they could not farm with irrigation canals. Beyond this valley, the rivers did not have the attributes described earlier that resulted in sufficient and reliable surface water.

The important part of this statement is that the people present at the edge of the wilderness—that is, west and south of it—as settled agriculturalists, in permanent riverside villages, were the Sobaipuri O'odham. Equally importantly, their easternmost distribution was along the San Pedro River, and their northern terminus at this time was at or south of the confluence of the San Pedro and Gila Rivers. This was the northeastern boundary of the Sobaipuri O'odham homeland, as it was during the later mission period (Seymour Reference Seymour2022b). Their residences and the river itself defined the western and southern margins of the wilderness as Coronado expedition participants understood it.

One reason this scenario has not been previously considered is that for decades scholars assumed that the Sobaipuri O'odham were late arrivals. Many early sources (and some current researchers) have them appearing in the area right before the mission period in the 1690s (see the discussion in Seymour Reference Seymour2011a). The assumption is that there was a hiatus, but dozens of chronometric dates have proven this wrong (Seymour Reference Seymour2011a, Reference Seymour2011c, Reference Seymour2014, Reference Seymour2020c, Reference Seymour2022b). We know that the Sobaipuri O'odham were present at and before the time of Coronado, as some earlier scholars did recognize (see Bandelier Reference Bandelier1929:35–36; Riley Reference Riley and Lange1985:160–161).

Another reason this reconstruction has not been possible before is that most scholars also viewed the Apache as late arrivals (e.g., Sauer Reference Sauer1932). For example, Hodge (Reference Hodge1895:230–231) wrote:

Had the Apache been in this section the narrators could not have failed to notice them. The only suspicion of the occupancy of the southern Arizona country by the Apache is that aroused by a statement of Castañeda to the effect that in the region round about Chichilticali . . . dwelt a “gente mas barbara de las que bieron hasta alli biuen en rancherias sin poblados biben decasar y todo los mas es despoblado.” . . . That ruin must have been in the heart of the Sobaipuri country, and these or the congeneric Opata were in all probability the savages to whom Castañeda alludes.

So, although Hodge correctly places the Sobaipuri O'odham along the San Pedro River, he did not realize that at least two additional groups were also present then: the Jocome and ancestral Apache also predated the Coronado expedition by at least a couple of centuries.Footnote 11

Many scholars have mischaracterized the adaptation of the Sobaipuri O'odham, which meant that they could easily confuse the Jocome and Apache for the Sobaipuri O'odham (e.g., Sauer Reference Sauer1932:36), just as did Hodge (Reference Hodge1895:231), who stated, “The fact that they are referred to as dwelling in isolated cabins, as being savage, and as living by the chase, is not at all surprising; indeed, these characteristics pertained quite as well to some of the early Piman tribes as to the later known Apache.” Unfortunately, these misconceptions persist today, despite a robust literature (already cited) backed by substantial field data that counter these notions.

Vicinity of an Occupied Pueblo

In the winter of 1539–1540 Melchior Díaz stayed at Chichilticale, and as noted, it is clear from the documents that it was located at the edge of the wilderness. He wrote, “It is impossible to cross the unsettled region there is between here and Cíbola because of the excessive snow and cold there is” (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:236). Díaz and his company stayed in this encampment on the San Pedro River for about two months at the place referenced as Chichilticale (see translation in Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:391).

Importantly, Díaz and his company were in or adjacent to a Sobaipuri O'odham village in the valley (also see Sauer Reference Sauer1932:32, 36; Schroeder Reference Schroeder1955:265; Undreiner Reference Undreiner1947).Footnote 12 We know Díaz was in the valley among the Sobaipuri O'odham because, in his letter to the viceroy, part of which was then quoted in a letter to the king, Díaz referred to the residents of the area as “the people of this pueblo” (Antonio de Mendoza, letter to the king, Jacona, April 17, 1540, AGI, Sevilla, Patronato, 184, R.31). This passage means that he was at or near an occupied village. We have already established that the only place this far east in southeastern Arizona that was occupied by villagers at this time was along the San Pedro River and that these villagers were the Sobaipuri O'odham. The Spaniards would have considered village-based agriculturalists to be settled, and therefore these villagers would have been the Sobaipuri O'odham. Díaz recognized that these were permanent villages, with irrigation and productive fields, as Marcos de Niza described: “which is so [heavily] populated by splendid people and so [well] supplied with food that it is enough to feed more than three hundred horses. Everything is irrigated and it is as a garden. The neighborhoods [or pueblos] are half a league and a quarter of league apart”Footnote 13 (my translation; Marcos de Niza, Relación de Fr. Marcos de Niza a la provincia de Culiacán en Nueva España, 1539, AGI, Patronato, Legajo 20, N.5, R.10).Footnote 14

Coronado's statement is different from that of Díaz, wherein he mentioned the “Indians of Chichilticale” (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:256; Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1940:165). The “Indians of Chichilticale” to whom Coronado was referring were probably those inhabiting the mountainous area where Jaramillo's Chichilticale pass was located, the ones who told them the name of the pass. The name given the pass (see the earlier discussion) indicates that they were the ancestral Apache, who lived as Castañeda stated, “in rancherías, without permanent habitations. They live by hunting” (my translation from Castañeda de Nájera, Relación, Case 12, Rich Collection 63, Nuevo Mexico, Sevella, 1596, 157n11, quarto bound).

Díaz said his camp was at or near an occupied “pueblo,” but he meant that he was near a “village” in our current way of thinking. Later, in Father Eusebio Francisco Kino's time (the 1690s and early 1700s), these Sobaipuri O'odham settlements were referred to as “rancherías,” but even later they were called “pueblos” again (for an extensive discussion see Seymour Reference Seymour2011a, Reference Seymour2022b; Seymour and Rodriguez Reference Seymour and Rodriguez2020). The use of these different terms is somewhat a matter of semantics, yet Díaz's use of the term “pueblo” has larger implications. What Díaz was saying is that he was in or near a Sobaipuri O'odham village, not a pueblo in the sense of Puebloan groups farther north. These Sobaipuri O'odham pueblos or villages were not multistoried adobe compounds as we have come to think of pueblos today; the important concept is that he viewed these people as settled villagers, not as mobile hunter-gatherers.

While at this winter encampment, Díaz's company asked around about Cíbola. In their introduction, Flint and Flint (Reference Flint and Flint2005:234) state, “Both Zaldívar and Díaz reported that they made assiduous efforts to obtain information about Cíbola and Tierra Nueva, both by scouting and by interviewing local natives who had been there.” Although this was not explicitly stated by Díaz, one could take from what Díaz reports the implication that his men moved throughout the valley asking Sobaipuri O'odham about Cíbola. Recall that 300 men, plus some women, went to Cíbola with Esteban, which means that many of the Sobaipuri O'odham along this river would have had direct and recent knowledge of that place (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:75). Although Marcos reported that most of these people died along with Esteban (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:75), it seems apparent from Coronado's statement (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:262) and from subsequent events—that is, playing the flute as taught at Cíbola (see Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:237)—that few of these Sobaipuri O'odham men were actually killed. Instead, they may have been taken captive for a short period of time or given a good talking to about joining the Spaniards in their forays. It seems unlikely that a message would have been sent to these Sobaipuri O'odham from Zuni later in 1539 if such a large number of their men had been killed (see the later discussion).Footnote 15 When Marcos came through, he reported that many of the locals knew details about Cíbola, so there was also likely regular interaction. Presuming the Spaniards did move around throughout the valley during this two-month period, we can reasonably assume that many more sites in this area might have evidence of the Coronado expedition, beyond the place where Díaz camped (and in addition to the route and camps used by later Coronado expedition companies). Sobaipuri O'odham villages clustered but only in certain areas along the river where there was reliable surface water (Seymour Reference Seymour1989, Reference Seymour2011a, Reference Seymour2015b, Reference Seymour2020c, Reference Seymour2022b, Reference Seymour2024). As I have discussed elsewhere, these were spatially separate, socially and politically distinct villages that sometimes formed larger communities located along the same canal system or in the same reach of the river (Seymour Reference Seymour2011a, Reference Seymour2015b, Reference Seymour2022b). Yet, in any one area there were as many as a dozen to three dozen sites that represented the temporal shifting of residences up and down the river segment. This makes it somewhat difficult to assess which specific settlement(s) might have been occupied during this expedition (although it does preclude those communities found along separate river segments). Parsing these temporal distinctions and locating evidence of the expedition at Sobaipuri O'odham villages are objectives of future research.

Spaniards also entered the mountainous areas to look for minerals and resources. They surely moved along and beyond the river to visit nearby villages, perhaps even camping overnight. Even if only making a day visit, they potentially left residues and physical impressions of their short stay (horses hobbled outside the village; activities of domestic servants who may have come along but remained outside the village, etc.). Trade items would have been exchanged for goodwill, information, food, and resources, and some were likely passed along to other residents on this river and elsewhere.

Although the Spaniards probably did travel around through the valley extracting information from the locals, the Sobaipuri O'odham would not likely have been friendly. This seems apparent in a statement made by Díaz (my translation; Mendoza, letter to the king, Jacona, April 17, 1540, AGI, Sevilla, Patronato, 184, R.31) that they were not welcome:

Those from Cíbola told those of this [Sobaipuri O'odham] pueblo and its vicinity that if some Christians came that they should not have anything to do with them and that they should kill them because they were mortal and that they knew it because they had the bones of the one who had gone there and that if they did not dare, to send them a message because they would come to do it right. I believe that this has happened like this and that they have spoken with them based on the lukewarmness with which they received us and the mean face that they have shown us.

This is probably why their encampment was at the north end of the Sobaipuri O'odham settlement area on this part of the river, separated to some degree from the closest village. This series of statements provides invaluable information that is incorporated in the subsequent discussion to interpret the archaeological evidence at these sites.

The Ruined Roofless House

One meaning of Chichilticale, as Castañeda understood it, was that it was a ruined roofless house, and as Sauer (Reference Sauer1932:36) noted, “This was a prehistoric ruin of some fame as a landmark at that time.” In fact, as noted, the word in Nahuatl means “red house.” This ruined roofless house was said to have been built by a people who left Cíbola long ago:

Chichilticale was so called because the friars [sic] found in this region a house that was in other times populated by people who split from Cíbola, it was made of reddish or russet earth. The house was large and it seemed to have been a fortress. And it must have been abandoned because of those from the land who are the most barbaric people of those seen until then. They live in rancherías, without permanent settlements. They live by hunting [my translation of de Castañeda de Nájera, Relación. Case 12, Rich Collection 63, Nuevo Mexico, Sevella, 1596, 157n11, quarto bound].

It was disappointing for everyone to see that the renowned Chichilticale was summed up in a ruined roofless house, insomuch as it seemed in another time to have been a casa fuerte [strong house/fortified house] at the time it was inhabited and it was recognized to have been built by foreigners, diplomats, and warriors, who came from afar. This house was of russet earth [my translation of Castañeda de Nájera, Relación. Case 12, Rich Collection 63, Nuevo Mexico, Sevella, 1596, 157n11, quarto bound].

Scholars have long recognized that what Castañeda was describing was an abandoned Salado or Western Pueblo ruin or possibly a late prehistoric Trincheras ruin. Most have assumed this ruin was a sizable village, such as Kuykendall Ruin and 76 Ruin. Yet, the text says it was a ruined roofless house (casa), not a village and not a building. Potter (Reference Potter1908:271–272) also came to this conclusion. Most researchers have defaulted to Sauer and Brand (Reference Sauer and Brand1930:426) for their understanding of the distribution of these types of ruins, which for the most part are sizable village sites or pueblos and are situated to the east of the San Pedro and on the San Pedro to the north of our area of interest. Yet, many more late ruins are now known that are not substantial and therefore were not recognized by locals and so were not recorded by Sauer and Brand (Reference Sauer and Brand1930). The ruins happen to be in an area I have studied for four decades, and so I know the intricate details of sites there, having recorded, tested, and chronometrically dated many of the visible rectangular adobe-walled structures (Seymour Reference Seymour1990, Reference Seymour2011a, Reference Seymour2011b, Reference Seymour2014, Reference Seymour2022b). There are four late ruins on the San Pedro River within range of the trail as it was then known in the fall of 2023, and these were used to assess which, if any, might be Chichilticale.

Castañeda's account presents additional details about this ruined structure. It would have been rectangular, which would account for its description as a house (nonrectangular huts were not considered houses by the Spanish; see Seymour Reference Seymour2009c:158, Reference Seymour, Flint and Flint2011d, Reference Seymour2013:183). It almost certainly had standing walls because he might not have perceived it as a ruined roofless house without them; however, as he noted, it had no roof. Once a building loses its roof it disintegrates relatively quickly. From this we can assume that the ruined roofless house was one of the latest occupied in the area and so was more visible than other ruins there. It was also likely made of adobe or adobe and stone, as were many of the ruins in this area. This is affirmed by Castañeda's description of it as reddish and russet/ginger (colorada o bermeja): the colors of adobe. Past translations have emphasized its reddishness, sometimes translating this passage to indicate it was bright red, but this does not seem to be the intent of his statement—nor does it match the ruined house recorded.

Castañeda also conveyed in his account that Chichilticale “in former times, when it was inhabited . . . [it] appeared to have been a strongly fortified building” (Flint and Flint Reference Flint and Flint2005:393) or that it “appeared to be a strong place at some former time when it was inhabited” (Winship Reference Winship and Powell1896:482). Castañeda de Nájera, Relación. Case 12, Rich Collection 63, Nuevo Mexico, Sevella, 1596, 157n11, quarto bound) lamented that “The famous Chichilticale turned out to be a roofless ruined house, although it appeared that formerly, at the time when it was inhabited, it must have been a fortress” (Hammond and Rey Reference Hammond and Rey1940:207). These translations indicate that the house itself may have been large, with a surrounding wall or thick walls, or that it was on an elevated landform. What Castañeda actually wrote, however, is this: “which seemed to have once been a casa fuerte [strong house/fortified house] at the time it was inhabited” (que parecia en otro tiempo haber sido casa fuerte en tiempo que fue poblada; my translation; Castañeda de Nájera, Relación. Case 12, Rich Collection 63, Nuevo Mexico, Sevella, 1596, 157n11, quarto bound). A casa fuerte is a defensible building or fortified house.Footnote 16