Over 25 years ago in American Antiquity, Erlandson and colleagues (Reference Erlandson, Robertson and Descantes1999:524) urged the development of “regional libraries of geochemical data for red ochre sources” in North America to support provenance studies. As they explained, “If geological samples from a single [ochre] source are relatively localized, relatively homogeneous, geologically distinct from other regional sources, and were used by people in the past, they may well be used by archaeologists to help reconstruct patterns of trade or resource use” (Erlandson et al. Reference Erlandson, Robertson and Descantes1999:524). Ochre from the Paleoindian Powars II quarry in Wyoming is an exciting success along these lines, clearly distinguishable from other ochres and appearing in the archaeological record over 100 km from the quarry (Erlandson et al. Reference Erlandson, Robertson and Descantes1999; Pelton et al. Reference Pelton, Becerra-Valdivia, Craib, Allaun, Mahan, Koenig, Kelley, Zeimens and Frison2022; Tankersley et al. Reference Tankersley, Tankersley, Shaffer, Hess, Benz, Turner, Stafford, Zeimens and Frison1995; Zarzycka et al. Reference Zarzycka, Surovell, Mackie, Pelton, Kelly, Goldberg, Dewey and Kent2019). In general, however, there is a “major problem with red ochres in that they are extremely difficult to provenance” (Siddall Reference Siddall2018:5).

As with other rocks and minerals, ochre sources vary considerably in geographic scale (Popelka-Filcoff and Zipkin Reference Popelka-Filcoff and Zipkin2022). Igneous and metamorphic materials—such as metamorphic ochre from Powars II or the Crooked Red source in southern Arizona (Eiselt et al. Reference Eiselt, Popelka-Filcoff, Darling and Michael2011)—may be chemically or mineralogically distinctive on a smaller scale because they formed in localized geological events. Ochre also occurs in sedimentary sources (e.g., Dayet et al. Reference Dayet, Texier, Daniel and Porraz2013; Matarrese et al. Reference Matarrese, Di Prado and Poiré2011), which instead tend to be heterogeneous and widespread in their occurrence. In regions dominated by sedimentary rock, ceramic materials may be chemically similar over long distances (e.g., Golitko et al. Reference Golitko, Riebe, Kreiter, Duffy and Parditka2024; Roper et al. Reference Roper, Hoard, Speakman, Glascock and DiCosola2007). A chert source may equate to an entire geologic formation or member of a formation (e.g., Boulanger et al. Reference Boulanger, Buchanan, O’Brien, Redmond, Glascock and Eren2015; Luedtke Reference Luedtke1992), and in some cases, sources are only geochemically distinct because of hydrothermal alteration (Newlander Reference Newlander, Speer, Parish and Barrientos2023). For ochre provenance studies in sedimentary landscapes, a realistic outcome would be to identify specific rock types or geologic formations of origin rather than pinpoint smaller geographic areas as sources.

The first questions we ask about North American ochre should be broad ones: Is the ochre of igneous, metamorphic, or sedimentary origin? Can the rock type be narrowed down further (e.g., Dayet Reference Dayet2021; Pradeau et al. Reference Pradeau, Binder, Vérati, Lardeaux, Dubernet, Lefrais and Regert2016)? Does it have distinctive constituents that point to one or more appropriate geologic formations (e.g., Matarrese et al. Reference Matarrese, Di Prado and Poiré2011)? Sometimes, of course, ochre lacks distinctive constituents, and researchers conclude only that the material contains hematite (e.g., Needham et al. Reference Needham, Croft, Kröger, Robson, Rowley, Taylor, Jones and Conneller2018). In other cases, it is possible to at least determine geologic origin. In one North American example, the ochre on nonhuman bone in the Clovis Anzick burial in Montana was identified as sedimentary material (“an iron-rich silty mudstone”) through photomicrographs and electron microprobe analysis (Macintyre and Logan Reference Macintyre and Logan2001:122). In another North American example, potters at the Mississippian city of Cahokia in Illinois used ochre from hydrothermal deposits in red slips, as revealed by chemical and mineralogical analyses (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Freimuth and MacDonald2024). The closest hydrothermal deposits to Cahokia are at least 50 km away, so even just identifying material type was enough to reveal the long-distance movement of pigment.

This study provides the first description of red ochre sources in the Central Great Plains of Kansas, Nebraska, and western Iowa (Figure 1), a region in which archaeologists frequently encounter pigment as red “hematite” and yellow “limonite” (e.g., Wedel Reference Wedel1959:117, 319) but almost never describe it any further—much less connect it to possible sources. I rely on mineralogy assessed with powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) to distinguish two ochre sources that are formations or groups of formations. Source 1 is the Cretaceous Dakota formation, with exposures on the eastern side of the study area. Source 2 includes younger strata exposed to the west: the Cretaceous Carlile Shale, Niobrara, and Pierre Formations. Source 2 ochre is yellow but becomes red at 250°C–500°C. The creation of red ochre from yellow is easily accomplished in an open fire (Lin et al. Reference Lin, Natoli, Picuri, Shaw and Bowyer2021) and was a routine practice by Plains artists (Morrow Reference Morrow1975). Samples from a third potential source, Permian siltstones and shales (“red beds;” Tucker Reference Tucker2001:60), lacked identifiable iron oxides or hydroxides in this analysis and may not have been used as ochre.

Figure 1. Location of the study area, with collected geologic ochre and archaeological sites mentioned in the text. The mapped bedrock geology (King et al. Reference King, Beikman and Edmonston1974) appears courtesy of the US Geological Survey. (Color online)

Defining Ochre

I use the term “ochre” here to mean a mineral colorant or pigment with red, purple, or yellow streaks that is easily ground by hand (Hodgskiss Reference Hodgskiss, Beyin, Wright, Wilkins and Olszewski2023; MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Fox, Dubreuil, Beddard and Pidruczny2018). It is fine-grained material, dominated by clay- and silt-sized particles, and it may be processed to remove larger particles (Morrow Reference Morrow1975). The color typically comes from one or more iron oxide or hydroxide minerals in the fine fraction (Hodgskiss Reference Hodgskiss, Beyin, Wright, Wilkins and Olszewski2023; MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Fox, Dubreuil, Beddard and Pidruczny2018; Mastrotheodoros and Beltsios Reference Mastrotheodoros and Beltsios2022), such as red hematite and yellow goethite (Schwertmann and Taylor Reference Schwertmann, Taylor, Dixon and Weed1989). Ochre can be used as a dry powder or as pigment in a paint or ceramic slip (see discussion in Beck and Hill Reference Beck and Hill2025; Beck et al. Reference Beck, MacDonald, Ferguson and Adair2022:9, Reference Beck, Freimuth and MacDonald2024). In this article, I focus on ochre that is unheated or heated to 500°C or less, which excludes the discussion of ceramic slips or paints. I also focus on red ochre and ochre that becomes red when heat treated, although Plains peoples also used other pigment colors (Morrow Reference Morrow1975).

Some North American archaeologists describe ochre as “hematite,” but this can be a confusing label (Pierce et al. Reference Pierce, Wright and Popelka-Filcoff2020). It often refers to hematite in rock form, such as hematite-dominated rock in glacial till transported from the Canadian Shield (Pabian Reference Pabian1976; Whittaker Reference Whittaker2024) rather than the mineral hematite (or other iron oxides and hydroxides) disseminated throughout sedimentary rock. The latter is widely available in the geology of the Central Plains, whereas the former is not (Pabian Reference Pabian1976; Tolsted and Swineford Reference Tolsted, Swineford and Buchanan1984). Globally, people have used ochre from iron ore or sedimentary iron deposits with an iron content over 15% (Eiselt et al. Reference Eiselt, Popelka-Filcoff, Darling and Michael2011; MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Velliky, Forrester, Riedesel, Linstädter, Kuo, Woodborne, Mabuza and Bader2024; Tucker Reference Tucker2001), but the iron content need not be that high. In practice, the iron minerals that give ochre its color may comprise as little as 3%–5% of the ochre (e.g., Eiselt et al. Reference Eiselt, Popelka-Filcoff, Darling and Michael2011; Sajó et al. Reference Sajó, Kovács, Fitzsimmons, Jáger, Lengyel, Viola, Talamo and Hublin2015), with other minerals such as quartz and clays making up the remainder (Mastrotheodoros and Beltsios Reference Mastrotheodoros and Beltsios2022).

Ochre definition is key in a search for ochre sources. The Plains ethnographic record is not much help for defining ochre in geological terms; although paint collection, processing, and use activities are briefly documented, any description or identification of paint materials is exceedingly vague (see Beck et al. Reference Beck, MacDonald, Ferguson and Adair2022; Morrow Reference Morrow1975). The only known quarry in the ethnographic record is a “Ponca paint mine said to be in the bluffs just west of Niobrara State Park” (Howard Reference Howard1965:69). In my work to identify possible sources, I use a definition of ochre that is not limited to hematite rocks or iron ore but broadly includes hematite, limonite, ironstone, iron oxides, and red or purple shale or mudstone. I compare sources on the level of the geologic formation or group of formations.

Sample and Methods

My approach relies on mineralogy, used in pigment studies to characterize materials and identify source rock type when possible (e.g., Grifa et al. Reference Grifa, Germinario, Pagano, Lepore, De Bonis, Mercurio and Morra2025; Pradeau et al. Reference Pradeau, Binder, Vérati, Lardeaux, Dubernet, Lefrais and Regert2016). Mineralogy has also been used to link sedimentary and metasedimentary pipestones to their geologic formations of origin (see Emerson et al. Reference Emerson, Hughes, Farnsworth and Wisseman2020; Wisseman et al. Reference Wisseman, Hughes, Emerson and Farnsworth2012). Here, I analyze geologic ochre samples with XRD, an established and widely accessible technique for assessing mineralogy in geologic and archaeological materials that requires a small powdered sample (Quinn and Benzonelli Reference Quinn, Benzonelli and Sandra2018). Raman spectroscopy is a nondestructive alternative often used for analyzing archaeological pigments (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Freimuth and MacDonald2024; Lin and Chang Reference Lin and Chang2022). As a line of evidence, mineralogy is best for materials heated to lower temperatures (if at all) during processing and use. Heating changes several mineral phases, such as altering goethite to hematite around 250°C–300°C and, at temperatures higher than 500°C, destroying the crystalline structure of clay minerals and oxidizing and decomposing calcite, dolomite, sulfides, and sulfates (Cavallo et al. Reference Cavallo, Fontana, Gialanella, Gonzato, Riccardi, Zorzin and Peresani2018; Quinn and Benzonelli Reference Quinn, Benzonelli and Sandra2018; Zumaquero et al. Reference Zumaquero, Gilabert, María Díaz-Canales, Fernanda Gazulla and Pilar Gómez-Tena2021).

For a geologic formation to serve as a defined ochre source, the mineralogical variability between formations must exceed variation within them (see Weigand et al. Reference Weigand, Harbottle, Sayre, Timothy and Jonathon1977). Geologists establish this on at least a large scale when they define and characterize formations—units that are distinct from others in “lithic characteristics and stratigraphic position” (North American Commission on Stratigraphic Nomenclature 2005:1567). Minerals and other lithic characteristics reflect the conditions under which they form (Hazen and Morrison Reference Hazen and Morrison2022), conditions that varied between the formations or groups of formations here as described below.

The 17 samples in this study (Table 1) are part of the pigment library in the North American Archaeology Laboratory at the University of Iowa. They were collected in a series of trips between May 2021 and March 2024 from five contexts: Cretaceous Pierre Shale (Figure 2a); Cretaceous Niobrara Formation, Smoky Hill Chalk member (Figure 2b); Cretaceous Carlile Shale (Figure 2c, d); Cretaceous Dakota Formation (Figure 2e–h); and Permian system siltstone and shale (Figure 2i).

Figure 2. Examples of collected geologic ochre (a–i) and archaeological ochre (j–l). Geologic ochre samples are shown both unheated (left) and heated (right): (a) Pierre-1; (b) Niobrara-1; (c) Carlile-1; (d) Carlile-2; (e) Dakota-2; (f) Dakota-4; (g) Dakota-8; (h) Dakota-10; (i) Permian-1; (j) 25NC1; (k–l) 25CH1. (Color online)

Table 1. Geologic Ochre Samples in This Study.

a Indicates sample heated to 650°C.

The study area (see Figure 1) is based on the combined study area of two previous projects comparing geologic samples to archaeological ochre at two sites in Kansas—14SC1 and 14RP1 (Beck and Hill Reference Beck and Hill2025; Beck et al. Reference Beck, MacDonald, Ferguson and Adair2022). The previously sampled geologic contexts were the Cretaceous Niobrara Formation, Smoky Hill Chalk member; Cretaceous Dakota Formation; and Permian system siltstone and shale. I have expanded the study area slightly to incorporate more samples from the Cretaceous Dakota Formation and new samples from the Cretaceous Pierre Shale and Carlile Shale.

Collection of ochre samples was guided by the geologic literature. My first step was to identify geologic formations with surface exposures and then review formation descriptions for references to iron oxide or hydroxides disseminated in the matrix or present in concretions. The search terms were hematite, limonite, ironstone, iron oxides, and red or purple shale or mudstone so as to cover a range of ochre types (also see Beck and Hill Reference Beck and Hill2025). My second step was to identify specific exposures, using a combination of geologic maps, published geologic field trips, and satellite imagery in Google Earth. Samples in this study were collected with a trowel from the exposed surface in roadcuts or an abandoned brick quarry (the Rose Creek pit in Jefferson County, Nebraska), with verbal permission from landowners.

To assess color, I first ground samples by hand in a ceramic mortar and pestle and then settled them in distilled water to concentrate finer particle sizes (clay and silt). I then mixed the finer particles with distilled water to create two pigment disks for each sample. A fragment from one of the two disks was heated in a Fisher Scientific Isotemp Muffle Furnace to 650°C, a temperature near the maximum temperature in ochre heat-treatment studies (Salomon et al. Reference Salomon, Vignaud, Lahlil and Menguy2015) that would ensure that all goethite had transformed into hematite (Cavallo et al. Reference Cavallo, Fontana, Gialanella, Gonzato, Riccardi, Zorzin and Peresani2018). During heating, I set the furnace to reach 650°C, held that maximum temperature for 30 minutes, and turned the furnace off and left ochre pieces inside to cool overnight. I recorded color data for unheated and heated disks in natural light with the 2000 Revised Washable Edition of the Munsell Soil Color Charts.

To assess mineralogy, I ground samples by hand in a ceramic mortar and pestle and then put the material through a No. 230 sieve to collect particles smaller than 63 µm (silt- and clay-sized particles). Daniel Unruh (Materials Analysis, Testing, and Fabrication [MATFab] Facility at the University of Iowa) conducted powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) on 0.1 g of screened material with a Bruker D8 ADVANCE diffractometer and identified minerals using the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) PDF-4+ powder diffraction database and Jade, EVA, and TOPAS analysis software. XRD data are from unheated ochre only.

Results and Discussion

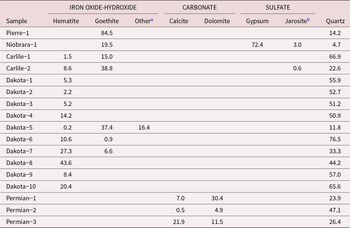

Tables 2 and 3 summarize identified minerals in all 17 geologic ochre samples. Examples of collected geologic ochre are illustrated in Figure 2a–i. Appearing alongside them are three ochre pieces (Figure 2j–l) from Central Plains archaeological sites 14SC1, 14RP1, 25NC1, and 25CH1 in the study area (see Figure 1). The archaeological ochre pieces were not analyzed but are shown here to illustrate their colors and aggregate shapes (platy and subangular or angular blocky). The visual similarities between geologic and archaeological ochre (see Figure 2) suggest that geologic formations close to these sites are plausible sources.

Table 2. Percentages of Identified Minerals in Geologic Ochre Samples, Part I.

a Lepidocrocite?

b Hydronium jarosite

Table 3. Percentages of Identified Minerals in Geologic Ochre Samples, Part II.

a Albite, microcline, or sanidine

b Muscovite

c Hydrohalloysite or tosudite

d Calcium aluminum hydroxide

Table 4. Typical Mineralogy of Defined Ochre Sources in This Study.

Almost all the XRD samples include quartz, mica, and clay minerals usually identified as kaolinite (see Tables 2 and 3). These are common constituents of ochre from the Great Plains and around the world, as are calcite and dolomite (Grifa et al. Reference Grifa, Germinario, Pagano, Lepore, De Bonis, Mercurio and Morra2025; Kingery-Schwartz et al. Reference Kingery-Schwartz, Popelka-Filcoff, Lopez, Pottier, Hill and Glascock2013; Reyman et al. Reference Reyman, Henning, Purdue and Moore2004; Teklay et al. Reference Teklay, Thole, Ndumbu, Vries and Mezger2023). Permian samples are distinguished from all others by the presence of calcite and dolomite and the absence of any identified iron oxides or hydroxides (see Table 2). There is no evidence that Permian red beds were used as ochre sources in the study area.

The remaining 14 geologic ochre samples are assigned to two sources that represent formations or groups of formations. Source 1 is the Cretaceous Dakota Formation, with red ochre containing 0.2%–43.0% hematite. Dakota formation ochre in the study area is particularly nondescript—in almost all cases, XRD analyses identify only hematite with quartz, mica, and one or more clay minerals (kaolinite or dickite or both; see Tables 2 and 3). Beck and colleagues (Reference Beck, MacDonald, Ferguson and Adair2022) suggested a Dakota source for red pigment on archaeological ceramics and powdered ochre at the Čariks i Čariks (Pawnee) site of 14RP1, comparing the archaeological samples to geologic samples from the Dakota-3 source. I still cannot disprove use of Dakota formation ochre at 14RP1 given the simple composition of the archaeological ochre and most Dakota samples. Red pigment at another Čariks i Čariks site—25NC1 (Beck Reference Beck2020; Figure 2j)—with its dark red color and blocky angular shape, is a reasonable visual match to ochre from the Dakota formation (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Dakota-7 collection site. (Color online)

Source 2 includes the Cretaceous Pierre Shale, Niobrara, and Carlile Shale Formations (Figures 4 and 5), with ochre that is yellow prior to heating because it contains more goethite than hematite (see Figure 2a–d; Table 2). Two of the four Source 2 ochre samples include a potassium iron sulfate mineral in the jarosite family (hydronium jarosite). When iron sulfide minerals such as pyrite and marcasite oxidize, the products include sulfuric acid and then iron oxides and hydroxides and secondary sulfate minerals such as jarosite and gypsum (Joeckel et al. Reference Joeckel, Matthew, J. Ang Clement, Hanson, Dillon and Wilson2011, Reference Joeckel, Divine, Hanson and Leslie2017; Singh et al. Reference Singh, Rajesh, Sajinkumar, Sajeev and Kumar2016). Smith (Reference Smith1977:93) has suggested that Plains peoples used “sulfur” (sulfate minerals?) for yellow pigment but provides no supporting information or further discussion.

Figure 4. Niobrara-1 collection site. (Color online)

Figure 5. Carlile-2 collection site. (Color online)

The exothermic reaction in the Carlile Shale Formation of iron sulfide to oxygen and water has been observed from the surface and has sometimes been mistaken for volcanic activity in Nebraska (Joeckel et al. Reference Joeckel, Matthew, J. Ang Clement, Hanson, Dillon and Wilson2011, Reference Joeckel, Divine, Hanson and Leslie2017). Along the Missouri River west of Dakota Formation exposures, where erosion along the river bluffs freshly exposed marcasite in the Carlile Shale, Meriwether Lewis described a “blue Clay Bluff . . . [that appeared] to have been laterly on fire, and at this time is too hot for a man to bear his hand in the earth” (Jengo Reference Jengo2011:9).

Jarosite, which is still identifiable in XRD after heating to 250°C–500°C (Cavallo et al. Reference Cavallo, Fontana, Gialanella, Gonzato, Riccardi, Zorzin and Peresani2018; Zumaquero et al. Reference Zumaquero, Gilabert, María Díaz-Canales, Fernanda Gazulla and Pilar Gómez-Tena2021), is a possible mineral in ochre from Source 2 contexts (Pierre Shale, Niobrara, and Carlile Shale Formations) but not Source 1 (Dakota Formation) contexts. Although pyrite weathering is common in the Dakota Formation and associated with iron oxide minerals (Joeckel et al. Reference Joeckel, Matthew and Bates2005), jarosite is “conspicuously absent” from the Dakota Formation (Joeckel et al. Reference Joeckel, Matthew, J. Ang Clement, Hanson, Dillon and Wilson2011:262).

Yellow ochre and possibly heat-treated red ochre have been recovered from archaeological sites near Source 2 deposits. At the Ndee (ancestral Apache or Dismal River) site of 25CH1 (Juptner and Hill Reference Juptner, Matthew and Hill2024), artifacts include both yellow (Figure 2k) and red ochre (Figure 2l). Selenite (a variety of gypsum) among the 25CH1 artifacts suggests that residents collected materials in sedimentary rock, perhaps from the Montana Group Pierre Shale relatively close to the site (see Figure 1).

The “Ponca paint mine” noted by Howard (Reference Howard1965:69), recorded by the Nebraska State Historical Society as site 25KX401, probably represents collection of yellow ochre from the Niobrara Formation. Niobrara yellow ochre could also have been used for red slips by seventeenth- and eighteenth-century potters at 14SC1 and nearby sites, based on the fired color and properties of the Niobrara-1 sample (Beck and Hill Reference Beck and Hill2025). The primary constituent of the Niobrara-1 sample is gypsum (72%), along with goethite (20%), quartz, and jarosite (see Table 2). Gypsum is an ingredient in paint elsewhere in the world (e.g., Nodari and Ricciardi Reference Nodari and Ricciardi2019) and may serve as a binder. An ochre with over 70% gypsum (calcium sulfate dihydrate) should be recognizable by portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) spectrometry (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Quinn, Goodale and Conrey2024).

Conclusion

Red ochre may be found in igneous, metamorphic, or sedimentary rock, but igneous and metamorphic sources formed in localized geological events are easier to define. Sedimentary ochres are nonetheless important resources, used by Indigenous communities in geologically diverse regions alongside other ochre types (e.g., Eiselt et al. Reference Eiselt, Popelka-Filcoff, Darling and Michael2011; Munson Reference Munson, Marit and Hays-Gilpin2020). In the sedimentary Central Great Plains, archaeologists have not identified any red ochre sources at all—a task complicated by the dearth of ethnographic information on pigments in the region.

This study explores the Central Plains landscape through geologic literature and sample collection, using geologic stratigraphic classification as a framework for defining sources. Differences in geologic history between formations produced mineralogical differences—specifically, differences in iron and sulfate minerals between two defined sources.

Source 1 is the Cretaceous Dakota Formation, containing red ochre usually just hematite with quartz, mica, and one or more clay minerals. Source 2 includes the Cretaceous Pierre Shale, Niobrara, and Carlile Shale Formations, with ochre that is yellow prior to heating because it contains more goethite than hematite. Jarosite minerals are possible in ochre from Source 2 contexts but not Source 1 contexts, and gypsum has only been identified to date in Source 2 ochre. Neither Source 1 or Source 2 ochre contains calcite or dolomite.

Source 1 and Source 2 appear to be plausible sources worth additional research, based on visual comparisons with archaeological ochre and evidence from previous work. Differences in the percentage or type of sulfate minerals, such as hydronium jarosite here or kornelite in the Northern Plains (Kingery-Schwartz et al. Reference Kingery-Schwartz, Popelka-Filcoff, Lopez, Pottier, Hill and Glascock2013:Table 1), may be particularly useful for distinguishing formations in a larger study area. The Permian red bed samples, with both calcite and dolomite and no identified iron oxides or hydroxides, do not represent a plausible source.

My work defines two sources of red or red-firing ochre in the Central Great Plains—the first sources to be identified in this sedimentary region. It also illustrates an approach to ochre research used elsewhere in the world (e.g., Matarrese et al. Reference Matarrese, Di Prado and Poiré2011; Pradeau et al. Reference Pradeau, Binder, Vérati, Lardeaux, Dubernet, Lefrais and Regert2016), rooted in a geologically broad definition of ochre and a focus on the geologic origin of materials. More than anything, this study seeks to explain what ochre is and where to find it within a particular landscape.

Acknowledgments

Daniel Unruh (MATFab Facility, University of Iowa) conducted the powder X-ray diffraction. Matthew E. Hill Jr. (University of Iowa), Oscar Hill, and Georgia Hill assisted in sample collection; and Trish Nelson and Dave Williams (Nebraska State Historical Society) provided access to ochre from 25CH1 and 25NC1. My sincere thanks go to them and to Rob Bozell, Spencer Pelton, Dave Williams, and anonymous reviewers for sharing their thoughtful and constructive feedback on the manuscript. No permits were required for this research. All photographs are courtesy of the author.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Donna C. Roper Research Fund of the Plains Anthropological Society and by the University of Iowa Department of Anthropology.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this study are included in this article. Geologic ochre samples are curated at the University of Iowa Department of Anthropology, Iowa City.

Competing Interests

The author declares none.