Introduction

Understanding state efforts to engage in “creating, nurturing, shaping and motivating” a national “self” has long been a key focus of Canadian political science (Norman, Reference Norman2006: 25; see Scott, Reference Scott1942; Smith, Reference Smith1981; Banting, Reference Banting2005). In Canada, the federal government engages in nation-building by projecting and promoting a unified identity, in which internal differences are minimized and distinctions from “others” are emphasized. This article focuses on the work of political parties to align Canadian identity with their party values. To this end, Prime Minister Stephen Harper once noted: “[My] long-term goal is to make Conservatives the natural governing party of the country. […] We’re also building the country towards a definition of itself that is more in line with conservatism” (quoted in Wells, Reference Wells2008).

In recent years, political scientists have grown increasingly concerned with efforts to meld partisan, state and national brands (Nimijean, Reference Nimijean2018; Marland and Nimijean, Reference Marland, Nimijean, Carment and Nimijean2021). Government mobilization of identity carries lasting social impact and orientates citizen engagement with politics and their processing of political cues (Raney and Berdahl, Reference Raney and Berdahl2009; Turgeon et al., Reference Turgeon, Bilodeau, White and Henderson2019; Merkley, Reference Merkley2021). Furthermore, voters are more supportive of parties and policies that align with their conception of Canadian identity, and questions pertaining to this identity are critical to voters during elections (Petry and Mendelsohn, Reference Petry and Mendelsohn2004; Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Banting, Kymlicka and Soroka2010; Raney and Berdahl, Reference Raney2011). As such, partisan conflict is not simply a debate regarding best policy practices but a battle to define social and political norms.

Recent research in this area has focused on the policy domains of multiculturalism (for example, Abu-Laban, Reference Abu-Laban and Jedwab2014; Elrick, Reference Elrick2021; Triadafilopolous, Reference Triadafilopoulos2023), citizenship (for example, Dhamoon and Abu-Laban, Reference Dhamoon and Abu-Laban2009; Tonon and Raney, Reference Tonon and Raney2013; Dobrowolsky, Reference Dobrowolsky, Fourot, Paquet and Nagels2018) and foreign policy (for example, Cros, Reference Cros2015; Paradis et al., Reference Paradis, Parker and James2018; Carment and Nimijean, Reference Carment and Nimijean2021). In this work, we look to official languages governance as a case study, pursuant to Nieguth and Raney’s call for further analysis of partisan constructions of national identity in policy (Reference Nieguth and Raney2017). Language politics have been a central focus for Canadian political scientists, generally pertaining to the governance of official languages (Cardinal et al., Reference Cardinal, Lang and Sauvé2008; Forgues, Reference Forgues2010; Léger, Reference Léger2013; Lapointe-Gagnon, Reference Lapointe-Gagnon2018), the politics of recognition (Charbonneau, Reference Charbonneau2012; Léger, Reference Léger2014), language hierarchies (Ricento, Reference Ricento2013; Haque, Reference Haque2014) and public attitudes regarding language (Dufresne and Ruderman, Reference Dufresne and Ruderman2018; Medeiros, Reference Medeiros2019; MacMillan, Reference MacMillan2021). Yet, despite research on nation-building in official languages conducted in South Africa, Türkiye and Ukraine (Orman, Reference Orman2008; Bayar, Reference Bayar2011; Fedorchenko, Reference Fedorchenko2024), researchers have yet to explore the interplay between governing ideology, national identity and official languages in the modern Canadian context. Much like immigration and citizenship, official languages governance dictates the style and degree of pluralism, drawing boundaries on what is officially Canadian and worthy of state support (Martel and Paquet, Reference Martel and Paquet2010; Haque, Reference Haque2012; Heller, Reference Heller, Block and Cameron2001).

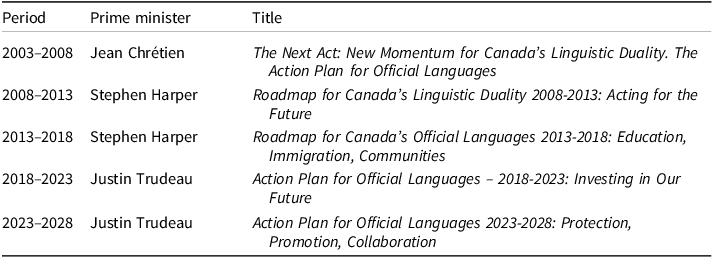

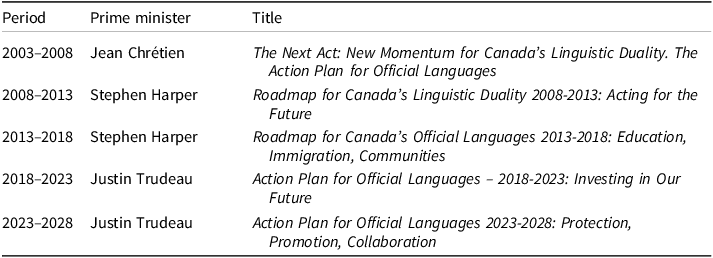

Canadian official languages governance is thus a fertile policy domain for analysing nation-building, which this article does by analysing and comparing partisan constructions of national identity in five official languages action plans and roadmaps. As shown by Cardinal, Gaspard and Léger (Reference Cardinal, Gaspard and Léger2015), these fundamentally political documents are policy instruments which serve to interpret the status and role of official languages in Canadian government and society, seen by stakeholders and policy makers as “vision statement[s]” (Canadian Heritage, 2017: vi) and the “public brand” of government action (Canadian Heritage, 2013: 2).Footnote 1 Jean Chrétien’s Liberal government published the first action plan in 2003, announcing renewed commitment to official bilingualism and new financial investments in official languages. The Harper Conservatives released five-year roadmaps for official languages in 2008 and 2013, and Justin Trudeau’s Liberals released two further action plans in 2018 and 2023, each replete with policy priorities, funding distributions and statements from the prime minister and the minister responsible for Official Languages. While the original 2003 action plan was developed to reinvest in official languages after years of cuts (ibid.; see also Mertl, Reference Mertl2000), the practice of developing five-year action plans or roadmaps is now established as an integral component of official languages governance in Canada. Indeed, the modernized Official Languages Act, adopted in 2023, requires the government to “develop and maintain a government-wide strategy that sets out the overall official languages priorities” (2023: 4).

Our primary objective is to analyse the Chrétien, Harper and Trudeau governments’ instrumentalization of Canadian national identity within the action plans and roadmaps. To do this, we propose an interpretive framework to facilitate the analysis and comparison of the constructions of national identity depicted in platforms, policy documents and political discourse. Our research contributes a new partisan and ideological focus to the literature on official languages governance and, in the process, contributes a novel insight into the government’s understanding of and ambitions for Canadian official languages policy and the relationship between the governing and the governed.

This article is organized into three sections. The first section summarizes official languages governance prior to the 2003 action plan and explains our approach to interpreting depictions of national identity. The second section identifies and analyses each government’s construction of a distinct Canadian identity in the action plans and roadmaps. The third section summarizes the instrumentalization of official languages to align with these presentations of Canadian identity, exemplified by the varied conceptualizations of Canadian official languages and “linguistic duality.”

Analysing the Instrumentalization of National Identity in Political Discourse and Texts

This article understands nation-building to be the effort to influence social and political norms through the construction of a national identity and the alignment of state institutions to that identity. Analysing political efforts to propagate and entrench an ideology within the public is contingent on understanding the depictions of Canadian identity being evoked, interpreted and instrumentalized in government policy and discourse. Recent studies to this end have employed a wealth of terminology, including national imaginaries (Dobrowolsky, Reference Dobrowolsky, Fourot, Paquet and Nagels2018), self-conception (Macklin, Reference Macklin and Mann2017), image (Cros, Reference Cros2015), brand (Nimijean, Reference Nimijean2005) and of course nationalisms (Dorion-Souliée et al., Reference Dorion-Soulié, Massie and Vézina2018). While this research may differ in its use of concepts, it ultimately engages with the same overarching question: What does the ruling party present as being Canadian?

Recent research has engaged with this question by isolating certain components within the instrumentalization of Canadian identity. These include a national narrative (MacKey, Reference Mackey1998; Reference Mackey2000; Blake, Reference Blake2013; Jeffrey, Reference Jeffrey2015; Wallner and Chouinard, Reference Wallner, Chouinard and Tröhler2023) and national values (Ipperciel, Reference Ipperciel2012; Tonon and Raney, Reference Tonon and Raney2013; Niegueth and Raney, Reference Nieguth and Raney2017). These parallel avenues of inquiry serve as the foundation of our interpretative framework for depictions of national identity, which we believe can serve to consolidate the broader conversation.

Our interpretive framework assists qualitative textual or discoursal analysis in identifying implicit meaning within the individual phrases, terms or concepts which invoke or appeal to a national identity (Hicks, Reference Hicks2009; van den Brink and Boily, Reference van den Brink and Boily2021; Boily and van den Brink, Reference Boily and van den Brink2022). As political language is ambiguous and indeterminate, meaning is reliant on the speaker’s context and usage (Wittgenstein, Reference Wittgenstein1958; Gallie, Reference Gallie1956; Skinner, Reference Skinner1978). Therefore, references and appeals to a national identity are non-neutral and are utilized with a specific purpose in the construction and depiction of a national identity. For example, references to a historical event pertain to a subjective memory rather than the “reality” outside the document. This can be seen as a generalization of floating signifiers, a concept previously used in studies of Canadian citizenship to analyse how key terms such as “foreignness” and “skilled” have meanings which are “subject to variation according to the specific ways in which discourses of nation, security and racialization interact” (Dhamoon and Abu-Laban, Reference Dhamoon and Abu-Laban2009: 166; see also Abu-Laban, Reference Abu-Laban2024). As such, political language which invokes or appeals to a national identity can be understood as fulfilling three distinct but co-informing roles in the construction of that national identity: contributing to a narrative, establishing collective values or giving affective context (Figure 1). This interpretive framework facilitates comparison, especially when cases employ overlapping terms and concepts with distinct meanings.

Figure 1. Our Interpretive Framework for Depictions of National Identity Comprising Three Distinct but Deeply Co-informed Components: Narrative, Values and Affect.

Our framework’s first component is a collection of subjective memories of people, policies or events, which we term the “narrative” (Anderson, Reference Anderson1983; Bouchard, Reference Bouchard2014). Within the narrative, the nation finds its origin and raison d’être. From this foundation, the narrative builds a storyline consisting of successes and failures and of heroes and villains. The narrative is utilized as evidence of the identity’s continuity and in providing historical context for the nation’s collective values. These values (for example, justice, strength, honor and duty) are presented as inherent and defining features of the nation and, therefore, also function as abstract societal ambitions. For example, if the nation’s citizens are presented as inherently “just,” it is natural they would further pursue “justice” in the future. As such, depicted values offer insight into the reasoning of the characters within the narrative. Finally, the affect is the presentation of a collective emotional response. The affect grants key positional context within the narrative, for example, whether a person or event is associated with pride or pain. In doing so, the use of affect draws the limits on who is included and who is othered (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2014; Gaucher, Reference Gaucher2014; Reference Gaucher2020). Furthermore, the choice of which emotions are used to demonstrate positionality—for example, the difference between using disgust or sadness to demonstrate negativity—is informed by and provides context for collective values.

Through the affective use of a national narrative and collective values, political discourse seeks to construct and perpetuate a national identity. These identities are used in parallel with the redefinition of relevant political concepts to suppose public demand, reframe policy questions and naturalize partisan approaches to governance. Through the propagation and perpetuation of this redefining of national questions through state institutions and political discourse, the ruling party aims to entrench partisan ideals within social and political norms.

Official Languages Governance in Canada

Language serves as a cultural basis for Canada’s Québécois, Indigenous and Acadian minority nations, and language policies have been an instrument of nation-building through societal hierarchization, homogenization and assimilation (Martel and Paquet, Reference Martel and Paquet2010; Haque, Reference Haque2012; Ricento, Reference Ricento2013). More specifically, language politics have served to institutionalize the superiority of English language and culture over French (Couture, Reference Couture1996; Cardinal and Léger, Reference Cardinal, Léger and Ricento2019; Charbonneau, Reference Charbonneau2020), to erase Indigenous culture and history (McKay, Reference McKay2013; Heller and McElhinney, Reference Heller and McElhinny2017; Huron, Reference Huron, Albaugh, Cardinal and Léger2024) and to establish the limits of belonging for othered immigrant communities (Haque, Reference Haque2014; Haque, Reference Haque2014; see Esman, Reference Esman1982).

The current paradigm of official bilingualism exists as a response to Quebec’s Quiet Revolution, as French Canadians had become “… for all intents and purposes second-class citizens in their own country. This was true both within Quebec, where they were in the majority, and outside of it” (Chouinard, Reference Chouinard2021: 6; see Gagnon and Montcalm, Reference Gagnon and Montcalm1992; Vessey, Reference Vessey2016). The federal governments of this era, most notably Pierre Elliott Trudeau (1968–1979, 1980–1984), used this unity crisis to institute significant reforms to Canada’s social model (Russell, Reference Russell1983; Whitaker, Reference Whitaker1991; Laforest, Reference Laforest1995). Within his ambitious “Just Society” vision, P. E. Trudeau instituted major national policies such as multiculturalism and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982, hereafter the Charter). Even failed policies, such as the National Energy Program (1980) and the 1969 White Paper, were radical in their efforts to redefine the federation and its citizens beyond cultural and national divisions and towards a post-national society of individuals with shared civics (Laforest, Reference Laforest1995; McRoberts, Reference McRoberts1997).

Official languages governance represented an area of concession for P. E. Trudeau: “In terms of realpolitik, French and English are equal in Canada because each of these linguistic groups has the power to break the country” (Trudeau, Reference Trudeau1968: 31).Footnote 2 In hopes of countering French-Canadian or Quebecois nationalisms within the federation, the federal government became the flagbearer of French (alongside English) through official bilingualism (Iacovino and Léger, Reference Iacovino and Léger2013) To this end, the Official Languages Act (OLA) in 1969 enshrined equal status, rights and privileges to English and French across federal institutions. The Charter brought a judicialization of language politics and constitutionally enshrined education rights for official language minority communities (OLMCs)—French-speaking communities outside Quebec and English-speaking communities within Quebec (Cardinal and Couture, Reference Couture1996; Cardinal et al., Reference Cardinal, Gaspard and Léger2015).

In the decades which followed, this rethinking of Canada’s official languages became well established in Canadian society, as evidenced by support from the Mulroney Conservative government and their expansion of the OLA in 1988, and representation of francophones in federal institutions has increased markedly (Léger, Reference Léger2013; Gaspard, Reference Gaspard2019; Théberge, Reference Théberge2021).Footnote 3 Support for official bilingualism has remained steady among four fifths of the public, as recently as 2024 (Environics, 2024). Most notably, official bilingualism, as with many of the Liberal governments’ other policies, including multiculturalism, peacekeeping and the creation of the flag, became associated with both Canada and the Liberal party (Parkin and Mendelsohn, Reference Parkin and Mendelsohn2003; Environics, 2022).

It is within this context that the action plans and roadmaps have sought to shape the languages of Canada’s future while balancing the relative calm and appeasement—compared with the unity crisis of the twentieth century—with responses to continued sociopolitical challenges. As such, the action plans and roadmaps represent a new era in official languages governance at the federal level, shifting from a reliance on judicialization and allowed for greater politicization of the policy sector (Normand, Reference Normand, Rocher and Pelletier2013; Cardinal et al., Reference Cardinal, Gaspard and Léger2015).Footnote 4 These challenges include demographic shifts, such as reduced rates of individuals with English or French as their mother tongues (Cardinal and Léger, Reference Cardinal, Léger and Ricento2019). Furthermore, English’s demographic dominance over French continues with the growing proportion of new Canadians with English as their first official language (ibid.), and the increasing presence of English online and globally (Ives, Reference Ives and Ricento2019). Language politics have therefore reemerged as a focal issue in the past decade, with the White Paper on language (Government of Canada, 2021), Quebec’s Loi 96 (2021) and the modernization of the Official Languages Act (Reference Gallie2023). Furthermore, Indigenous reconciliation and resurgence have brought increased presence of Indigenous languages to the Canadian policy landscape, tabled politically through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action (2012: 6) and the Indigenous Languages Act (2019). However, these languages remain “unofficial” outside of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, impeding political commitments of revitalization and reconciliation (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2019; Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Leitch and Bear Nicholas2019; Huron, Reference Huron, Albaugh, Cardinal and Léger2024). As such, English and French have maintained their political and institutional hegemony (Haque, Reference Haque2012; Ricento, Reference Ricento2013).

Our analysis seeks to understand the distinct presentations and uses of national identity in this politicized era of Canadian official languages governance through the five action plans and roadmaps (Table 1). We have verified the consistency of the documents across both official languages and triangulated our findings with other official government outputs on official languages, including key speeches, press releases, legislation, platforms and other publications by the prime minister, the minister responsible for official languages and ministries such as Canadian Heritage. These secondary data ensure the authority of the action plans and roadmaps in representing official government discourse on official languages, which is consistent across the aforementioned formats. However, by focusing on government communication, our study analyses a more muted or “sanitized” rhetoric than what can be seen when the governing actors speaking unofficially to diverse audiences (Saurette and Gordon, Reference Saurette and Gordon2013; Clarke and Francoli, Reference Clarke, Francoli, Marland, Giasson and Esselment2017) and does not account for the differing presentations of Canadian identity seen among stakeholders, intellectuals and activists.

Table 1 The Five Action Plans and Roadmaps for Official Languages (2003–2023)

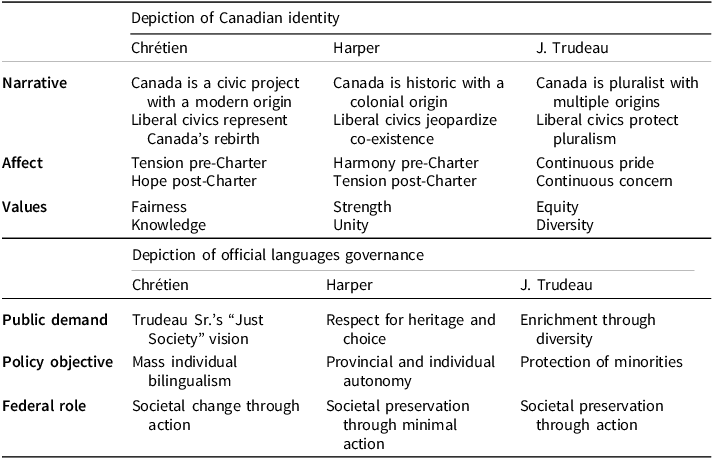

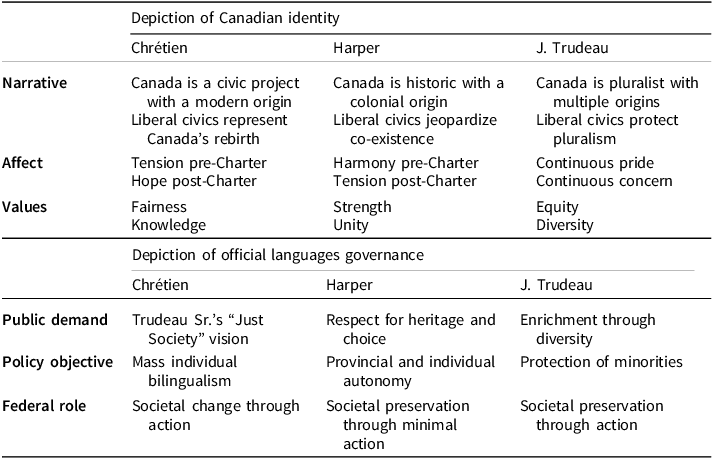

Table 2 Summary of the Depictions of Canadian National Identity in the Action Plans and Roadmaps and How They Suppose a Public Desire in Official Languages Governance for the Federal Government to Enact

Canadian Identity as Depicted by the Chrétien, Harper and Trudeau Governments

Canadian identity in the 2003 action plan

The 2003 action plan’s narrative is couched in the context of liberal achievements, including the Charter and the OLA (Government of Canada, 2003: 1, 3, 11, 12, 13). Vague appeals to a preceding and half-forgotten “linguistic heritage” carry an affect of tension and are used to validate the Liberal reshaping of Canada in the 1960s and 1970s (2003: vii, 1, 3, 8, 13):

Over the past 30 years, the Government of Canada has invested in creating a competent, bilingual public service in order to provide employment opportunities to English- and French-speaking Canadians and to serve Canadians in the official language of their choice. The results are palpable. The situation has greatly improved since the introduction of the first Official Languages Act in 1969 and its revision in 1988. The public service is no longer the almost unilingual institution it was thirty years ago (2003: 49).

This new start carries an affect of hope when invoking Trudeau Sr.’s “ideal” of a bilingual Canada and naturalizes the ultimate goal of the action plan: increased individual bilingualism through the doubling of bilingual high school graduates (2003: vii, ix, 1–3, 8, 27, 28, 30, 61). As such, the 2003 action plan presents itself as “A New Act” within the Liberal narrative and the pursuit of a society built upon values of justice, fairness and individual rights. Chrétien uses his own roleFootnote 5 as a minister throughout Pearson and P. E. Trudeau’s mandates to justify these connections:

The ideal of a bilingual Canada where everyone could benefit from our Anglophone and Francophone heritage seemed to us in those days to be a fundamentally just ideal for our society […] My time at the Department of Justice a few years later gave us the opportunity to protect that heritage by including minority language rights in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This fundamentally democratic document is a source of great pride not only for me as Prime Minister, but above all for a great people, a just people: the Canadian people. (2003: vii; see also 4, 6, 13, 14, 15, 17, 45, 62, 64).

In appealing to the Liberal legacy, the action plan mirrors other policy sectors wherein the Chrétien government’s “Canadian Way” expanded and reinterpreted Liberal civics such as multiculturalism and peacekeeping (Nimijean, Reference Nimijean2005; Cros, Reference Cros2015). We can see the concept of official bilingualism has been expanded to emphasize international themes such as global trade and diplomatic standing:

If the Plan succeeds, the proportion of high school graduates with a command of both our official languages will rise from 24% to 50%. When one out of two high school graduates can speak both our official languages, and in fact some of them will master a third or even a fourth language, Canada will be even more open to the world, more competitive and better positioned to ensure its prosperity. (Government of Canada, 2003: 61; see also x, 1–4).

As such, it is no surprise that, while acknowledging the “vulnerability of French in North America” (2003: 37; see also 3), there is little distinction given to Quebec relative to other provinces. Rather, the protection of vulnerable communities is directly associated with maximizing the knowledge of individuals. For example, minority language education is immediately tied to second-language education (2003: 5, 17, 25), and the action plan stipulates: “The learning of a second official language by the majority is increasingly an asset for the future of minority communities”. (2003: 24; see 5, 13). As such, rather than depicting Canada as a collection of nations with long and enduring histories, Chrétien’s action plan idealizes the Canadian Project: a just and evolving society of diverse and bilingual individuals with shared civics and values (2003: x).

Canadian identity in the 2008 and 2013 roadmaps

The roadmaps present the Canadian narrative as centuries old, emphasizing colonial roots: “English- and French-speaking Canadians have come a long way together since the founding of Québec City, which also marks the founding of the Canadian state, 400 years ago this year” (Government of Canada, 2008: 4; see also Government of Canada, 2013: i, 7, 9, 17). This colonial origin serves as the foundation of a nation of immigrants, with French and English as the dominant cultural heritages (2013: 9; see also 5, 12, 17). This narrative carries an affect of harmony, emphasizing the coexistence which preceded the Liberal project. In constructing a narrative centred on coexistence of settling peoples, the roadmaps evoke values of a strong and unified Canada.

Canada has a rich culture and history that are the product of Canadians’ aspirations and accomplishments. The peoples who formed our vast country did not all speak the same language. They did not all share the same culture. But our peoples did come together. The bonds between us were strengthened and an exceptional feeling of solidarity arose. Over the centuries, our country became enriched with extraordinary diversity. As Canadians, we are very proud of the coexistence of our two national languages. (Government of Canada, 2013: i).

Harper emphasizes these values in his opening address, noting: “Our country is more united today than it has been since our centennial” (Government of Canada, 2008: 4; see 5, 7, 15; 2013: i, ii, 1). This reference to Canada’s centennial, and the disunity which follows, is part of an affect of tension placed upon the Liberal era. Though the 2008 roadmap briefly invokes the 2003 action plan and the OLA to briefly establish precedence (2008: 7, 13, 14), this Liberal legacy is absent from the 2013 roadmap. The Charter is simply omitted from both roadmaps, consistent with the Harper Conservatives ideological opposition to the Charter’s egalitarian liberalism in other policy sectors (Laycock and Weldon, Reference Laycock, Weldon and Laycock2019) and efforts to co-opt or de-emphasize Liberal civics and symbols such as peacekeeping and multiculturalism (Ipperciel, Reference Ipperciel2012; Frenette, Reference Frenette2014; Raphael, Reference Raphael2021). This questioning of the civic model is also consistent with Harper’s prior comments deeming “the enforcement of national bilingualism” to be “the god that failed” (Harper, Reference Harper2001; see Harper, Reference Harper1997). The roadmaps thus eschew the idea of Canada as a project nation, and with it the ambition for universal bilingualism.

Rather, the Harper government seeks to “begin a promising journey” (Government of Canada 2008: 5) true to Canada’s colonial origin (2008: 4, 15; see also 2013: i, ii, 1, 2, 5, 15, 17). As such, bilingual government services emphasize language as a choice (2008: 5, 7–8, 11; 2013: ii, 14–16), bilingual programs facilitate cultural exchange between these distinct groups (2008: 5, 6; 2013:1, 2, 4–6, 11, 12) and individual bilingualism largely represents a boon to personal employment and cultural enrichment (2008: 4, 13; 2013: 1, 2, 4, 5, 9).

The emphasis on unity as a Canadian value is evident in the roadmaps’ symmetrical engagement with both official languages and with all provinces as equal partners. While the settling of Quebec is emphasized and Quebec itself is recognized as the “cradle of the Canadian Francophonie” (2008: 14), these historical titles are used to depict Canada’s origin, rather than validate a unique role for the Quebec government relative to the other provinces. Specifically, all provinces are granted more agency to engage with bilingualism, OLMCs and integration of newcomers on their own terms: “The provinces and territories recognize the importance of ensuring the vitality and development of official-language minority communities” (2008: 8; see 6, 7, 12; 2013: 16, 17). Similarly, Ottawa and New Brunswick are highlighted precisely because they are the most willingly bilingual areas, therefore the government will act therein to preserve bilingualism.

To this end, the Roadmap will intensify current efforts to facilitate recruiting and integration, particularly by supporting francophone immigration in New Brunswick, the only officially bilingual province in Canada. (2008: 11) and [the roadmap will] encourage federal public servants to exercise their right to work in the language of their choice in the National Capital Region and other regions designated as bilingual in terms of language of work (2008: 8, 14; 2013: 16).

The roadmaps present themselves as increased government commitment and financial investment true to their presentation of Canadian identity (though the reality of the roadmaps’ fiscal investment has been questioned).Footnote 6 By presenting official bilingualism as specific to Ottawa and New Brunswick, the roadmaps engage with Harper’s earlier declarations which disassociate Canadian identity from official bilingualism and the Liberal era, also evident though unilingual ministerial appointments and the elimination of the court challenge system (Cardinal et al., Reference Cardinal, Gaspard and Léger2015). The Harper government’s depiction of identity therefore justifies a shift from enforcement of official bilingualism without officially critiquing it, effectively pushing for minimal government action in official languages through the “stealthy” reform of a key policy sector for Canadian social and political norms, much like with multiculturalism (Abu-Laban, Reference Abu-Laban, Isin and Nyers2013; Kymlicka, Reference Kymlicka2021).Footnote 7

Canadian identity in the 2018 and 2023 action plans

As with the roadmaps, the 2018 and 2023 action plans highlight Confederation and the arrival of European settlers as part of the Canadian narrative. However, the incorporation of Indigenous peoples eschews the logic of a singular origin. Rather, Indigenous and settler narratives merge and continue to incorporate diverse experiences through immigration:

English and French have been spoken in what is now Canada for centuries. French came onto the scene in 1604, with the founding of historical Acadia in what is now Nova Scotia, and the founding of Québec in 1608 marked the beginning of a permanent European presence on these lands. Canada’s linguistic heritage is also enriched by roughly 70 Indigenous languages that have been spoken here from time immemorial, and owing to successive waves of immigration from around the world, more than 200 other languages are now spoken here on a daily basis, languages that contribute to Canada’s diversity. (Government of Canada, 2023: 24; see also 2018: 7, 8).

Much like Trudeau’s appeals to and expansion of Liberal ideals such as multiculturalism and peacekeeping (Nimijean, Reference Nimijean2018; Dobrowolsky, Reference Dobrowolsky, Fourot, Paquet and Nagels2018), references to the Charter, the OLA and the 2003 action plan play key roles in this depiction of national identity (Government of Canada, 2018: 6, 8, 33, 53; 2023: 11, 12, 14, 15, 24, 29, 30). Specifically, the Liberal era of the 1960s and 1970s represent the protection of Canada’s pluralist origin. The narrative frames this pluralism before and after this Liberal era with an affect of pride, especially in the 2018 action plan (2018: 7, 8, 30, 41, 42; see also 2023: 6, 7). As such, the 2018 action plan establishes equality and diversity as Canada’s collective values, while the 2023 action plan specifies these values as substantive equality, equity and inclusion. While the preceding action plan and roadmaps had used the term “diversity” as ethnic, cultural or linguistic, the 2018 and 2023 action plans expand the term. For example, they include efforts to protect and support women and lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer/questioning and more (LGBTQ+) individuals (2023: 24; see also 7, 9, 13, 14), true to Trudeau’s progressive motifs seen in other policy sectors (Dobrowolsky, Reference Dobrowolsky, MacDonald and Dobrowolsky2020; Icart Reference Icart2023): “This ambitious five-year plan is the next step in our ongoing efforts to achieve substantive equality of English and French in Canada, with a clear focus on diversity, inclusion, and equity.” (Government of Canada, 2023: 6; see also 8, 9, 13, 14, 24, 25).

The conflict within this narrative is the continued presence of colonialism and assimilation, highlighted by an affect of concern (2018: 8, 9, 12, 45; 2023, 7, 11, 12, 13). Specifically, the lack “identity security” for Canada’s Francophonie is a matter of great urgency for the Trudeau action plans (Government of Canada, 2023: 11; 24). The roadmaps are depicted as having exacerbated this crisis through their inaction, as the 2018 action plan declares itself to be “the first real additional investment in official languages since 2003” (2018: 12; see also 16, 17, 53).

Studies clearly show that the ability to pass on the French language remains as difficult as ever in Canada’s minority communities. Among British Columbia’s Francophones, four out of five children will be assimilated before kindergarden [sic]. This is huge. (2018: 24; see also 8, 9, 43; 2023: 7, 30).

Canada’s pluralism requires a targeted policy response to protect French, specifically regarding the vitality and “linguistic well-being among Francophones” and OLMCs through targeted immigration, education and cultural measures (2023: 24; see 10, 30; 2018: 6, 8, 25, 26). Notably, the preservation of cultural diversity is directly tied to the returning goal of raising rates of individual bilingualism: “This is why we support and encourage second-official-language learning—because we believe that a more bilingual Canada better respects our official-language minority communities” (2018: 8; see 7, 13, 15; 2023: 30). More specifically: “the importance of our linguistic duality and bilingualism as the foundation of the social contract that brings us together” (2018: 7). The invocation of a social contract references Liberal civics-based values, wherein respect diversity, equity and equality are modelled not only by supporting OLMC rights but by living bilingualism as a citizen. Though not as ambitious as the Chrétien government’s goal for 50 per cent bilingualism among high school graduates, the Trudeau action plans seek to raise bilingualism from 17.9 per cent to 20 per cent by 2036, with specific focus on anglophones outside of Quebec (2018: 41; see also 9, 43; 2023: 6, 21).

The Trudeau government therefore translates the established Liberal portrayal of national identity that has been used to justify the enforcement of official bilingualism for decades. The 2018 and 2023 action plans posit Canada’s pluralist beginnings mandate the federal government preserve Canadian diversity for the sake of equity and substantive equality. The government’s active role in official languages is evident key speechesFootnote 8 and in large scale policy action such as the Indigenous Languages Act and the modernization of the Official Languages Act. Yet, considering Trudeau’s conception of Canada as “the first post-national state” with “no core identity, no mainstream” (Lawson, Reference Lawson2015), his increased engagement in official languages paints a complicated picture regarding Canada’s minority nations (Carbonneau et al., Reference Carbonneau, Léger, Houde and Zentrum2022). For example, the federal government remains the flagbearer for French in Canada despite newfound engagement with the government of Quebec to preserve its majority language (Government of Canada, 2023: 6, see also 7, 9, 11, 12).

The Instrumentalization of Languages and Linguistic Duality

Key to this connection between the depicted identity and governance is the redefining of key political concepts and reshaping of policy questions. This section analyses how the Chrétien, Harper and Justin Trudeau governments redefine languages within depictions of national identity, as evidenced through the floating signifier “linguistic duality” (Théberge, Reference Théberge2021). Within the action plans and roadmaps, linguistic duality is instrumentalized as a historic concept and serves to justify language hierarchies, and therefore the objectives and role of the federal government in official languages governance. For example, linguistic duality inherently serves in each national narrative to place Indigenous peoples and languages relative to the depiction of Canadian identity (see Green, Reference Green1995; Starblanket, Reference Starblanket2019; Starblanket and Hunt, Reference Starblanket and Hunt2020). Furthermore, linguistic duality is presented as an “asset” by each action plan and roadmap. However, the way in which this asset is defined serves as evidence of how the government understands Canada’s official languages—for example, depicting language and Canada’s linguistic duality as an individual endeavor or a communal experience, as an identity or an economic tool (Canut and Duchêne, Reference Canut and Duchêne2011; Heller, Reference Heller2010).

Linguistic duality under Chrétien

The 2003 action plan references linguistic duality as a historic and key piece of Canadian history. However, these references are vague and non-committal:

Linguistic duality is an important aspect of our Canadian heritage. The evolution that has brought us to the Canada of today has followed different paths. Canada has developed a strong economy, a culture of respect, an effective federation and a multicultural society. Throughout that evolution, it has remained faithful to one of its fundamental dimensions: its linguistic duality. (Government of Canada, 2003: 1; see also vii, 2, 3).

In contrast, the Chrétien action plan’s use of linguistic duality in the contemporary context is evident in his opening address: “Our linguistic duality means better access to markets and more jobs and greater mobility for workers.” (2003: vii; see 2, 3). The Chrétien government frames linguistic duality as an asset precisely when Canadians embody it in at an individual level, therefore emphasizing official bilingualism in the name of improved human capital. Language is therefore commodified and more divorced from culture and history than in the subsequent action plans and roadmaps. This commodification within the 2003 action plan inherently others Indigenous languages. Referred to briefly, Indigenous languages are to be “preserved” (2003: 2), in contrast to French and English which are to be “promoted” and “strengthened” (2003: 2, 3, 14, 54, 67, 70).

Linguistic duality under Harper

The roadmaps anchor their understanding of linguistic duality in Canada’s colonial origins. The confederation era is depicted as harmonious coexistence, while the relatively recent enforcement of bilingualism for the sake of a minority group has created tension. Thus, the roadmaps propose the avoidance of tension by engaging with English and French symmetrically and reducing federal ambition in the sector, conceptualizing language an asset for personal choice and individual freedom:

Our federation was born of a desire by English- and French-speaking Canadians to share a common future, and it was built on respect for the language and culture of all Canadians. Linguistic duality is a cornerstone of our national identity, and it is a source of immeasurable economic, social, and political benefits for all Canadians. (2008: 4; see also 8, 12; 2013: 6).

Indeed, Minister James Moore summarizes this emphasis for a linguistic duality for “all Canadians” in his letter at the opening of the 2013 roadmap: “[The Roadmap creates] a country in which Canadians from all walks of life can benefit from Canada’s linguistic duality and make their contributions to society in the official language of their choice.” (2013: ii; see 3, 4, 5, 11, 14; 2008: 6, 9, 10, 15). To this end, the roadmaps propose tools for cultural exchange, greater choice in government services and greater respect for provincial jurisdiction, excluding Indigenous languages altogether.

Linguistic duality under Trudeau

The 2018 and 2023 action plans present language as a shared communal identity, and linguistic duality as a foundational aspect of Canadian pluralism: “[Linguistic duality] is why we support the vitality of official-language minority communities and celebrate the voices they bring to our country’s landscape.” (2018: 8). The state’s role according to the action plans is therefore to nourish this diversity and “support more vulnerable clienteles” as a source of “pride” and “enrichment” for Canada and Canadians (2023: 9; see also 20, 24; 2018: 6, 7, 8, 30, 41, 42).

Canada’s two official languages, English and French, are at the heart of who we are as Canadians. They are at the centre of our history. Along with Indigenous languages, they are a powerful symbol of our country’s diverse and inclusive society. (2018: 8).

Notably, the Trudeau action plans use the concept of linguistic duality much less than their predecessors, especially in 2023. Given the Trudeau government’s pluralistic and inclusive narratives, and their engagement with Indigenous languages (for example, the Indigenous Languages Act), they may be shifting away from the exclusivity of linguistic duality, perhaps allowing for future additions to Canada’s official languages (Ives, Reference Ives and Ricento2019). Nonetheless, Indigenous languages remain symbolically and substantively distinct to English and French within the Trudeau action plans (2023: 24; see also 2018: 7, 8).

In sum, the use of linguistic duality as a floating signifier is evidence of instrumentalization of key political terms within the action plans and roadmaps. Each government tailors these concepts, as well as Canada’s languages themselves, to align with their presentation of national identity. In doing so, they justify their proposed policy goals and methods, presenting them as true to the nation.

Conclusions

The five action plans and roadmaps for official languages provide insight into each federal government’s depiction of Canadian identity and how it justifies the preservation and support of some languages over others. Using our interpretive framework, we process the use of narrative, values and affect and their alignment with the distinct policy objectives within each document. For example, the use of narrative and affect serves to demonstrate either a heritage of tension in absence of government involvement in the case of the three action plans or a heritage of tension due to government involvement in the case of the roadmaps. This instrumentalization of identity is facilitated through the redefinition of key political concepts, including languages themselves, as demonstrated by the floating use of “linguistic duality.”

We see continuity of Trudeau Sr.’s vision for official bilingualism under Chrétien. The 2003 action plan is built upon an understanding of a civics-based Canada which only truly began in the Liberal era of the late twentieth century. The Chrétien government maintains a central focus on fairness, with a priority for universal bilingualism, but also widens the Liberal identity to include a greater international focus. For the Harper Conservatives, Canada’s linguistic duality represents its colonial origins, and the official languages provide an opportunity for citizens new and old to engage with the linguistic community of their choice. The roadmaps present government efforts to impose bilingualism as a threat to individual choice and national unity. As such, the Harper government represents an unprecedented challenge to the established Liberal paradigm in language governance. In contrast, Justin Trudeau’s action plans adopt significant portions of the Liberal brand with the addition of a pluralistic narrative inclusive of Indigenous peoples and the threat of assimilation. As such, the Trudeau government insists asymmetric action is required to ensure substantive equality between the diverse identities at the heart of Canadian identity.

These findings raise new questions for future research. We believe our interpretive framework could facilitate comparative research across policy sectors to better understand how national identities are constructed and mobilized in a holistic sense. To what extent does the policy sector—and stakeholder audience—affect the government’s presentation of narrative, affect or values? To what extent does the policy sector affect the instrumentalization of key concepts such as linguistic duality, gender or Indigeneity? Similarly, while our study has captured clear and distinctive presentations of Canadian identity, our focus on official government communications arguably captures the most muted of ideological discourse, as seen in relation to our brief references to Harper’s earlier rhetoric (see also Laycock, Reference Laycock2001; Kellogg, Reference Kellogg2020). Further study is required to understand the full scope of the varying conceptualizations of Canada’s languages and identities across parties, intellectuals and the public.

In their efforts to understand Canada, political scientists have long perpetuated what they perceive Canada to be (Underhill, Reference Underhill1935; Nath, Reference Nath2011; Abu-Laban, Reference Abu-Laban2017). Similarly, the narratives, values and affects brought to Canada’s official languages demonstrate the Chrétien, Harper and Trudeau governments’ efforts to mobilize partisan understandings of what Canada is and what the government should be. These messages are propagated through policies and communications, subsequently influencing how Canadians understand themselves and those around them. Research on these distinct perspectives and understandings of Canada and Canadians is of utmost importance in this era of ideological evolution and growing polarization (van den Brink and Boily, Reference Boily and van den Brink2022; Environics, 2023; Merkley, Reference Merkley2023; Boily and van den Brink, Reference Boily, van den Brink, Fortier-Chouinard, Birch, Arsenault, Duval and Dufresne2025).