Introduction

Starting from the mid-1990s, the literature about volunteering has significantly focused on the transformations of volunteering in contemporary (Western) societies. Second modernity theories (Beck, Reference Beck1992, Reference Beck, Beck, Giddens and Lash1994, Reference Beck2000; Giddens, Reference Giddens1991) have largely driven scholars’ and practitioners’ interpretations. This theoretical frame has helped to address the transition toward the so-called new forms of voluntary action, but debate in this regard still seems uncompleted. Scholars and practitioners have often welcomed the idea, similarly to other realms (Chadwick, Reference Chadwick and Bevir2007), that voluntary action in contemporary (Western) societies has been progressively destructured and disintermediated, i.e., released from the cognitive, regulative and organizational intermediations between volunteers and recipients that structured the field of volunteering in first modernity. The trends toward modernization and individualization of volunteering have been reduced “to a process of dis-embedding, without acknowledging a parallel process of re-embedding” (Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010: 166).

Although the recent literature has begun to fill this gap (Haski-Leventhal et al., Reference Haski-Leventhal, Meijs and Hustinx2010; Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010), the re-embedding processes of volunteering within second modernity still need to be better “differentiated,” “delineated” and “empirically investigated” (Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010: 175). This paper intends to do this in theoretical and empirical terms by focusing on the reintermediation processes of contemporary voluntary action in Italy. On the whole, it enables us to better grasp the plural nature of contemporary volunteering, its renewed intermediations and emerging tensions. Beyond the national case, the approach followed here helps to better understand the strategies of collective actors in the field of volunteering and the assemblies between global trends and local configurations.

In the first section, after having briefly recalled second modernity-inspired interpretations on the transformations of voluntary action, I introduce my research approach. Against dichotomic, abstract and implicit visions of change, I argue that different types of volunteering “traditions” (active membership, direct, program and organize-it-yourselves) coexist in contemporary (Western) societies and that they are generated and coevolve in path-dependent ways through the interplay of diverse strategic actors. In the second section, this approach is used to address the reintermediation processes within the Italian volunteering field in the 2000s. Although the analysis is exploratory, it can help to understand the coevolutions of the four traditions and identify a typical restructuration model based on professional agencies coming from the membership tradition.

The Changing Intermediations of Volunteering in Contemporary Societies: A Situated Approach

According to second modernity theories, contemporary volunteering has progressively abandoned the twentieth-century styles of involvement. The why (motivations to volunteer) and how (forms of volunteering) would appear to have changed conjointly (Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010; Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx2010a, Reference Hustinxb). Sacrifice, altruism and sociopolitical engagement may no longer be the central cognitive frames to explain why people act for free, whereas exploring, entertaining, strengthening employability and self-development emerge as typical motivations (Beck, Reference Beck, Beck, Giddens and Lash1994; Handy et al., Reference Handy2010). Second modernity volunteering has been shown to be more “reflexive”—that is “driven by individual preferences and shaped through occasional involvement in a diversity of settings” (Hustinx & Lammertyn, Reference Hustinx and Lammertyn2003: 168). The ways through which volunteers provide their own activity are changing toward occasionality, flexibility and temporality. “Episodic volunteering” (Wilson, Reference Wilson2012) is increasingly relevant in the world: that of “individuals who engage in one-time or short-term volunteer opportunities” (Cnaan & Handy, Reference Cnaan and Handy2005: 30). Contrary to the long-term commitment to membership-based associations in first modernity, the “new forms of voluntary action” are mainly carried out through a weak and limited belonging to an organization or without any form of organizational membership, “during special times of the year, or at one-time events, often in the form of self-contained and time-specific projects” (Meijs & Brudney, Reference Meijs and Brudney2007: 69). All this relieves volunteers from moral obligations and organizational structures, but it can also undermine conventional notions of gratuitousness. This shift risks contrasting with the civic action frame of volunteering (Eliasoph, Reference Eliasoph2009). Individualization and reflexivity may, however, shape the self-organization of engagement opportunities (Norris, Reference Norris2002).

Although these changes appear to dramatically challenge notion, practice and the possible impacts of voluntary action as we knew it in the twentieth century, a radical disorganization, disintermediation and deinstitutionalization of the voluntary action seems unrealistic. Contemporary voluntary action is more likely to be involved in relevant reintermediation processes. As Hustinx (Reference Hustinx2010: 174) wrote,

the ongoing debate has focused too one-sidedly on the ‘de-institutionalization’ of volunteering – that is, the breakdown of its traditional organizational design – and failed to recognize that these old frameworks are being replaced with new organizational forms. To fully understand emerging forms of volunteering, we thus need to pay more systematic attention to new processes of re-structuring.

In this perspective, institutions and organizations are brought back into the debate and the focus is shifted to the changing intermediations of volunteering in late modern societies. Two major paths appear to have emerged. In the first (primary restructuration), voluntary associations are still center stage. They design and adopt “new organizational strategies to better cope with [the] biographical changes of the individual volunteers (…) [and to] offer more attractive and flexible volunteering menus” (Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010: 170–174). The second path (secondary restructuration) mainly occurs outside the membership tradition and it is shaped by “third parties” (e.g., schools, governments, corporations) (Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010: 173; Haski-Leventhal et al., Reference Haski-Leventhal, Meijs and Hustinx2010). Often in collaboration with voluntary associations, they provide people with a differentiated offer of short-term and highly individualized volunteering programs, whose objectives (e.g., boosting social (re-)integration, employability and active citizenship) are shaped by each third party’s specific mission. These volunteering opportunities are designed and offered top-down, as “plug-in” activities that “mimic classic voluntary participation” (Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010: 174), or as institutionally enforced mandatory activities.

The renewed intermediations can foster and enhance volunteering in second modernity, but they also pose several challenges. The growing role of communication, marketing and management activities may be to the detriment of other activities in associations. Volunteering seems to result more from “recruitment efforts by the organization than from the intrinsic motivations of the volunteers” (Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010: 175). Third parties’ actions question the standard definition and conventional public understanding of volunteering as free will and they prompt issues regarding the instrumental uses of episodic volunteering (De Waele & Hustinx, Reference De Waele and Hustinx2019).

Nevertheless, research on the reintermediation processes of volunteering still seems to be unaccomplished. Whereas in-depth and critical investigations of single initiatives exist (eg. De Waele & Hustinx, Reference De Waele and Hustinx2019; Shachar, Reference Shacar2014), studies on the reintermediation paths of volunteering at country level are somewhat scarce. There is a lack of knowledge as to how these processes actually work in different contexts, beyond general typologies. Moreover, very little is known about some regions (e.g., Southern Europe).

As a contribution to further exploring, a dynamic and situated two-step approach is adopted here. The first step consists in giving volunteering a renewed sociological consideration. Volunteering is here intended as a complex and multifaceted phenomenon encompassing cognitive, regulative, agential and practice-related elements. This marks some distance from the conventional vocabulary of “new forms of voluntary action” where the “new” is implicitly and irreducibly counterposed to the “old” and the emphasis on the individual action risks obscuring institutional and organizational intermediations. The transformations of volunteering are here approached by integrating the reference to the (new) forms of voluntary action within the more comprehensive concept of “volunteering tradition,” which combines the different aspects of the “cross-section between individual and institutional forces” (Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010: 169). For “volunteering tradition,” I hereby mean a somehow coherent, multilayer and dynamic assembly of recognized beliefs, meanings and logics (cognitive components), formal regulations (regulative components), typical networks (social components), legitimized actors (agential components) and types of practice (practice-related components). This assembly becomes consolidated (institutionalized) within a context, under some conditions, in the medium–long term.Footnote 1 On the one hand, this definition owes much to the new institutionalist literature that highlighted the importance of cognitive features and regulative components for order and change (Béland, Reference Béland2005; Campbell, Reference Campbell2002; Pierson, Reference Pierson2001) and considered the context as distributing appropriateness and legimitimation entitlements among agents (March & Olsen, Reference March and Olsen1989; Hay, Reference Hay2002). On the other hand, the definition provides individual and collective agency with a significant—although bounded—room (Hay, Reference Hay2002). It releaves the voluntary action from pre-defined actors (such as voluntary associations), and it conceives “volunteering tradition” as the result of an institutionalizing process (Berger & Luckmann, Reference Berger and Luckmann1966) situated in time and space.

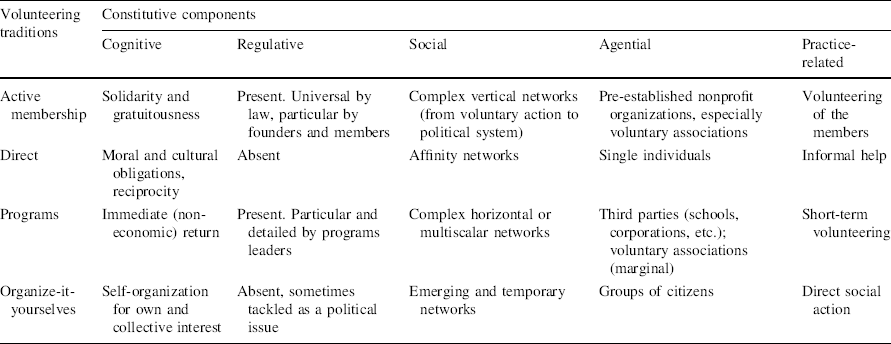

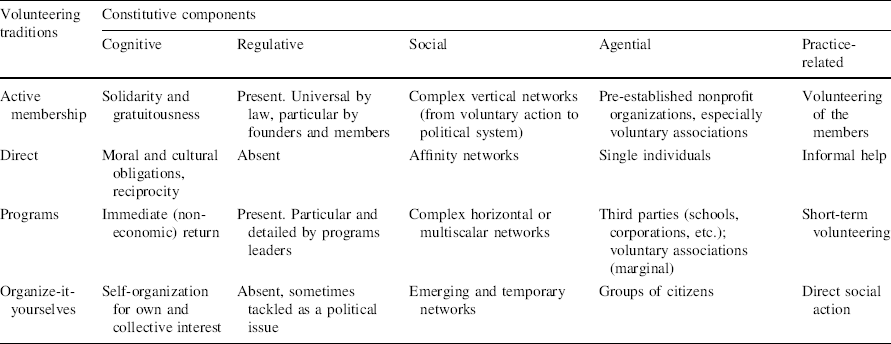

The recent literature seems to account for four ideal–typical volunteering traditions in contemporary societies.Footnote 2 Table 1 summarizes the key components of this starting typology. The active membership tradition has been considered typical of first modern Europe, namely of Scandinavian countries (Meijs & Hoogstad, Reference Meijs and Hoogstad2001; Dekker, Reference Dekker2018; Enjolras & Strømsens, Reference Enjolras, Strømsnes, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018). Here, volunteers belong to formally (pre-)established nonprofit organizations whose basic characteristics are regulated by legislation; core values and mission are shaped by founders; strategies, activities and instruments are defined by current members. Far from being a solipsistic activity, individual voluntary action is considered a way to reach the organization’s objectives. Organizations often have a multilevel structure and are intended as “mediating institutions between individual member and the national political system” (Enjolras & Strømsnes, Reference Enjolras, Strømsnes, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018: 2).

Table 1 Volunteering traditions, a starting typology

Volunteering traditions |

Constitutive components |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cognitive |

Regulative |

Social |

Agential |

Practice-related |

|

Active membership |

Solidarity and gratuitousness |

Present. Universal by law, particular by founders and members |

Complex vertical networks (from voluntary action to political system) |

Pre-established nonprofit organizations, especially voluntary associations |

Volunteering of the members |

Direct |

Moral and cultural obligations, reciprocity |

Absent |

Affinity networks |

Single individuals |

Informal help |

Programs |

Immediate (non-economic) return |

Present. Particular and detailed by programs leaders |

Complex horizontal or multiscalar networks |

Third parties (schools, corporations, etc.); voluntary associations (marginal) |

Short-term volunteering |

Organize-it- yourselves |

Self-organization for own and collective interest |

Absent, sometimes tackled as a political issue |

Emerging and temporary networks |

Groups of citizens |

Direct social action |

By contrast, in the direct volunteering tradition people act without any organizational intermediation (Einolf et al., Reference Einolf, Smith, Stebbins and Grotz2016). Volunteers’ actions are neither regulated by law or included in governance processes, nor coordinated, but they are not necessarily extemporaneous. Especially in Global South countries, low-status individuals often provide informal help within community circles (neighborhood, kinship, etc.) as a way to respond to moral and cultural obligations and/or as a reciprocity strategy allowing material subsistence (e.g., Andean “ayni” (Appe et al., Reference Appe, Butcher and Einolf2017) or informal assistance to HIV/AIDS victims in Africa (Fowler & Mati, Reference Fowler and Mati2019)). In Western societies, direct volunteering could, however, be interpreted in second modern terms, as an expression of individualistic, free, occasional involvement and a distrust in structured associations (Fonović et al., Reference Fonovic, Guidi and Cappadozzi2018). The lack of formal organization and the reciprocity pattern complicate the consideration of this kind of practice as volunteering, especially in some areas of the world (Guidi et al., Reference Guidi, Guidi, Fonović and Cappadozzi2021).

Growing attention has been dedicated to the program-based volunteering tradition. Considered prevalent in North America (Meijs & Hoogstad, Reference Meijs and Hoogstad2001), increasing in Scandinavian countries (Grubb & Henriksen, Reference Grubb and Henriksen2019) and facilitated by ICT technologies (Trautwein et al., Reference Trautwein2020), it is characterized by episodic, short-term and spatially circumscribed volunteering experiences provided by different organizations for the general public or specific targets. This voluntary action is usually top-down and highly regulated by the organizer. Short-term volunteering experiences are often promoted, designed and publicly communicated by an organization (often a “third party”) and developed in another one (e.g., a membership-based association), or in an event (e.g., local festivals, World Expo, Good Deeds Day, etc.). These provide the relational context for the experience (Cnaan & Handy, Reference Cnaan and Handy2005; Meijs & Brudney, Reference Meijs and Brudney2007). Thus, program-based volunteering is strictly organized. It implies the activation of many organizations that design and manage the programs (Maas et al., Reference Maas2021). It is individualized in so far as the voluntary action does not imply that the volunteer has an organizational membership, a value identification or a future involvement. The relevance of incentives supporting individual activation within this tradition sometimes undermines the definition of volunteering as a free action (De Waele & Hustinx, Reference De Waele and Hustinx2019; Tõnurist & Surva, Reference Tõnurist and Surva2017).

The final volunteering tradition can be named Organize-It-Yourselves. It includes those citizens’ voluntary actions directly faced with an emergent problem which is not tackled enough by institutions, market or existing civil society organizations. Voluntary action is here highly spontaneous and informal, but not disorganized. People coordinate themselves to achieve a tangible result through soft and temporary instruments which often do not imply (and sometimes explicitly reject) any formal membership. Rooted in the history of bottom-up citizens’ initiatives, this multifaceted volunteering tradition recurs in multiple contexts, from the USA communities in the 1990s (Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow1994) to the recent crises in Europe (Kousis, Reference Kousis2017; Simsa et al., Reference Simsa2019). People involved in the self-organized initiatives often aspire to contribute to solving a problem they personally face, but the activity (or its results) can also be enjoyed by others. Whereas many initiatives are limited to the achievement of circumscribed results in given and undisputed settings, some may prefigure new ways of managing the commons (see below for Italian examples). People here may not name their own practice as volunteering, since they often act for partly self-interested or political reasons. Clear are here the connections to civic action and social movements (Evers & van Essen, Reference Evers and von Essen2019; della Porta, Reference Della Porta2020).

Once notions and ideal types of “volunteering tradition” have been introduced as starting references, the second step consists in tackling (re)intermediations of volunteering in contextual and dynamic terms. Beyond general typologies, a context-specific analysis identifies the peculiar characteristics of the volunteering traditions and enables us to grasp how each one possibly emerges, spreads, evolves and declines in relation to the others over time. Rather than considering the “volunteering traditions” separately and associating each with a country or a region, in times of complexity different volunteering traditions are taken as coexisting and coevolving within the same context, although one or another can be considered mainstream in a context. From this perspective, the attention is focused on the changes and continuities in the field of volunteering. On the wave of the modernization-induced transformations, this field is expected to become more plural and complex with both a growing number of concomitant traditions and changes within the established traditions. Whether and how this actually happens is a matter of empirical investigation context by context.

To conduct it, a conception of how changes happen is necessary. One of the most significant weaknesses in the debate on the “new forms of voluntary action” seems to be the adoption of mechanistic and culture-driven implicit assumptions about change. Although it seems clear that epochal cultural shifts have pushed the voluntary action of (Western) societies toward more individualized and reflexive styles, the processes through which a volunteering tradition transforms and adapts and/or a new one emerges in a context are unclear.

The concepts of “path dependency” and “strategic field” can help to fill this gap. Volunteering traditions are expected to be generated and coevolve mainly through path-dependent processes. Second modernity trends exert a global influence on Western societies, but local contexts matter. Coherently with the “path dependency” assumption (March & Olsen, Reference March and Olsen1989, Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2000; Mahoney & Schensul, Reference Mahoney, Schensul, Goodin and Tilly2006), the peculiar characteristics of volunteering in a context, institutionally stratified in time, are presumed to “filter” global pressures for change and condition the strategies of actors.

This does not imply assuming change is impossible. Volunteering traditions are loose, malleable and manipulable. Following Bevir, Rhodes, Weller (Reference Bevir, Rhodes and Weller2003: 14–17), they are “a starting point, not a destination” and change as agents “make a series of variations to them in response to any number of specific dilemmas.” From this perspective, innovation does not necessarily need innovators from outside because also incumbent actors enjoy significant room to innovate from the inside. Coherently with the literature (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004, Reference Campbell, Morgan, Campbell, Crouch, Pedersen and Whitley2010; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Bainton, Lendvai and Stubbs2015; Freeman, Reference Freeman2007), generating and regenerating a tradition in a path-dependent way means here mainly assembling different components coming from within and outside of the volunteering field. Incumbent actors can, for example, insert new components into the existing tradition without betraying it, incrementally or surreptitiously alter it or eventually spin a new tradition off the consolidated one and keep control over both. Conversely, new actors can pick out some components of different existing traditions in order to assemble a new one or bring in some components from outside and tackle an existing tradition with these.

Against the risk of hypostasizing the interpretations, the changes and continuities are conceived as resulting from the reiterated and bounded interaction between different actors within a context. More specifically, volunteering traditions are expected to exist and change through the interplays of strategic actors engaging within a structured and complex field. Fligstein’s works help in this regard. In his terms, a field can be understood as

a social arena where something is at stake and actors come to engage in social action with other actors under a set of common understandings and with a set of resources that help define the social positions in the field (Fligstein, Reference Fligstein2013: 40).

A field is populated by strategic actors who work “to maintain their position” (Fligstein, Reference Fligstein2013: 41). Sometimes it means that they are inertial or that they contrast innovation. Sometimes promoting change or capturing and governing renewal trends can be more effective.

In settled times—when the field is structured—actions are oriented to reproduce a given order of clear rules, well-defined roles and taken-for-granted meanings supporting conventional actions. Conversely, in unsettled times—when the field is emerging—actors can become “institutional entrepreneurs” (DiMaggio, Reference DiMaggio and Zucker1988), working to build groups’ interests and identities as well as new meanings and rules (Fligstein & McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012: 291–292). To be successful, institutional entrepreneurs must have “social skills,” that is they must be able “to motivate cooperation in other actors” (Fligstein, Reference Fligstein1997: 398) by taking other actors’ interests into account, meet them (Fligstein, Reference Fligstein1997: 398–401) and “mobilize sufficient support for a certain shared worldview” (Fligstein & McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012: 292).Footnote 3

According to Fligstein and McAdam (Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012), the field can have three states: (1) emerging; (2) organized and stable; and (3) organized and unstable. Emerging fields are particularly those where rules do not yet exist, but actors increasingly collaborate on the basis of new and interdependent interests. Since there are few restrictions to action, here innovation is more likely and socially skilled actors “can make an enormous difference” (Fligstein & McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012: 299). Existing fields can have a boosting influence on those that are emerging because the former can provide “the market” for new ends to emerge (Fligstein & McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012: 298). A field can be made unstable by the invasion of those outside organizations which “are not bound by the convention of the field and are free to bring new definitions of the situation and new forms of action to the fray” (Fligstein and McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012: 301).

To recap, my approach to the study of volunteering reintermediation processes consists in

(a) (Re)considering volunteering in social and institutional terms through the notion of “volunteering tradition” and the reference to four ideal–typical traditions;

(b) Assuming that different “volunteering traditions” may coexist in the same context and that second modernity changes may push national fields of volunteering to become more complex and plural;

(c) Focusing attention on the peculiar characteristics and coevolutions of the different “traditions” in the field of one or more national/regional contexts;

(d) Assuming that these coevolutions are significantly path-dependent and that they result from the reiterated, complex, bounded strategic interactions of actors in the field.

Italian Volunteering Beyond the Membership Tradition: A Path-Dependent Restructuration

Exploring Italian Volunteering: Background and Methodological Questions

Cross-country analysis of non-profit and voluntary sectors is well established (Salamon & Anheier, Reference Salamon and Anheier1996; Salamon & Sokolowski, Reference Salamon and Sokolowski2001; Butcher & Einolf, Reference Butcher and Einolf2016) and the idea that second modernity has challenged volunteering as we knew it in twentieth century (Hustinx & Lammertyn, Reference Hustinx and Lammertyn2003) is largely shared among scholars and practitioners. However, comparative studies on the transformations of volunteering still seem weak and unsystematic.

In Europe, attention has been until now mainly focused on Northern countries. They certainly show remarkable trends, but they are small and peculiar in social and institutional terms. On the contrary, the changes of volunteering in Southern Europe have scarcely been addressed. This area is conventionally associated with a “parochial” model of civil society, “characterized by relatively small followings of voluntary organizations in combination with high percentages of the (few) members who engage in volunteering” (Dekker, van der Broek Reference Dekker and van den Broek1998: 27). Italy is a telling case on this point. Since Banfield (Reference Banfield1958) and Almond and Verba (Reference Almond and Verba1963) this country has been for a long time presented as a champion of the “amoral familistic,” “parochial,” “apathetic” and “alienative” political culture with very low levels of civism and associational resources.

Beyond the positioning in the international rankings on volunteering rates, little is known about the recent transformations of volunteering in Italy and almost nothing about its new intermediations. As an initial attempt to fill this gap, the next section focuses on the current volunteering traditions in the country. For each tradition, I explore the crucial characteristics, agencies and intermediation processes.

This kind of analysis poses serious methodological challenges. Each volunteering tradition has a knowledge regime (Campbell & Pederson, Reference Campbell, Pederson, Béland and Cox2010), dependent on its own cognitive, material and institutional traits. This implies that empirical research on the pluralization of volunteering traditions should endorse epistemological pluralism (Healy, Reference Healy2003) and recognize the unavoidable heterogeneity of approaches, definitions and methods. In Italy, knowledge regarding the “active membership tradition” is vast, reiterative and based on highly recognized formal operative definitions and standard instruments. Surveys are often conducted within the official statistical system, prompted by NPOs and used for lobbying and policy-making. Knowledge about the other traditions is instead largely episodic and non-standard. Evidence here is scarcely accruable since operative definitions are contended, practices are dispersed and there are no recognized agencies steering knowledge production.

This situation may generate some risks of scarce cohesion. These are here mitigated by the exploratory nature and the specific focus of the analysis. In the next section, different sources of knowledge (scholars’ publications, NPOs documents, legislation and official statistics reports) are used to grasp the most relevant intermediations of the four volunteering traditions. Once the attention is directed to (a) the characteristics of the agencies which shape and generate volunteering opportunities, (b) the processes through which they emerge and change and (c) the typical relations between the agencies and volunteers, tackling different knowledge regimes seems possible and the results of empirical research appear cohesive enough.

The (Mainstream) Active Membership Tradition

The active membership tradition in Italy has a long-term historical legacy. From the Late Middle Ages, catholicism before, and socialist mutualism later, inspired the establishment of organizations which have involved volunteers in the assistance of frail and disadvantaged people as a way to recognize brotherhood and community ties. Based on these, the current active membership tradition was structured from the mid-1970s to the early-1990s and onwards in such a way as to become mainstream (Ascoli & Cnaan, Reference Ascoli and Cnaan1997; Ranci, Reference Ranci1999; Guidi, Reference Guidi and Guidi2009, Rossi & Boccacin, Reference Rossi and Boccacin2006).

The basic traits were shaped by NPOs in the 1980s. In a lively debate, they publicly represented volunteering as a “new political convention” (Guidi, Reference Guidi and Guidi2009: 169)—different both from welfarism and party activism—and made new community self-managed services for disadvantaged people visible. The key players were not single volunteers but voluntary groups/associations. Their role in preventing volunteer work exploitation, giving individuals a chance of civic education and improving policies and institutions was particularly endorsed (Guidi, Reference Guidi and Guidi2009).

Early-1990s legislation recognized and further developed this tradition. Voluntary action was legally defined as “carried out in personal, spontaneous, free way through the organization participated by the volunteer” (Law 266/1991, art.2.1). Voluntary associations were expected to “use personal unpaid and free work of its members in a decisive and predominant way” (art.3.1). Associations could benefit from a wide freedom in terms of juridical forms and operative sectors, but they were limited by the membership configuration: Volunteers could not be paid and had to be insured by the association; clear member admission and exclusion criteria had to exist; the members’ assembly was the crucial associational body; official positions (e.g., President) were strictly free (art.3.2; 3.3). Legislation also contributed to shaping two developments. First, it regulated the partnerships between public institutions and voluntary associations with the consequent promotion of local welfare mix schemes (Ascoli & Ranci Reference Ascoli and Ranci2003). Second, it established new supporting infrastructures for voluntary associations, especially voluntary service centers (CSVs). Self-managed by voluntary associations, as from the late 1990s they were able to count by law on regular and substantial funds coming from the banking sector.

New millennium regulations affected the evolutions of this tradition without altering its pillars. Several laws in different domains (e.g., L.328/2000 in welfare, D.Lgs.1/2018 in civil protection) have further prompted collaboration between registered voluntary associations and public institutions. As a result, the former are today a key partner of public policies, with potential benefits in terms of participation and innovation, but with possible issues in terms of independence and advocacy (Ascoli & Ranci Reference Ascoli and Ranci2003; Pavolini, Reference Pavolini2003; Boccacin, Reference Boccacin2009; Costa, Reference Costa2009). Law 106/2016 (so-called “Third Sector Reform”) and subsequent measures have reformed existing instruments (e.g., register of voluntary associations), recognized the delegation role of national federations and broadened the mission of CSVs. The CSVs are now called to provide services to all the Italian organized volunteers, not only to voluntary associations.

To recap, formally established NPOs (i.e., registered voluntary associations and their supra-local federations) and policy-makers have been the crucial agencies in the membership tradition since the 1980s. Although associations are free, this tradition has been highly regulated by law since the early 1990s. Voluntary associations originally contributed to shaping this tradition, after which an attitude of institutional governance prevailed. The relations between volunteer and association are based on a kind of membership whose fundamental traits are defined by law.

Although current studies permit a limited diachronic analysis, recent changes in these relations do not seem to have disrupted the typical membership pattern. For example, ISTAT surveys in 2002 and 2013 (ISTAT 2006, 2014; Guidi & Maraviglia, Reference Guidi, Maraviglia, Guidi, Fonovic and Cappadozzi2016) showed the existence of concomitant motivations for a large majority of volunteers. In 2013, civic and social motives, often interconnected, are the most frequent, and religious motivations are peculiar to volunteers in religious organizations. Self-oriented motivations (e.g., exploring one’s own strengths, employability) are scarcely reported, but are relevant among youngsters. Radical views on volunteering appear, however, to be unconfirmed, and contrary to what associations often report (Salvini & Corchia, Reference Salvini and Corchia2012; Citroni, Reference Citroni2014), the volunteering rate among youngsters has been stable in the last twenty years (Guidi & Cordella Reference Guidi, Cordella, Ciucci and Tomei2014) and their engagement in terms of hours per week—as reported by ISTAT (2014)—is similar to other age groups.

The (Re-enacted) Direct Volunteering Tradition

People on the ground, practitioners and scholars (Ascoli & Cnaan, Reference Ascoli and Cnaan1997; Caltabiano, Reference Caltabiano2006) agree that a directly provided voluntary action, with no organizational intermediations, has always existed in Italy. Nevertheless, since no evidence has existed until recently, direct volunteering has remained largely unexplored. Moreover, the risks associated with this tradition in the debate promoted by NPOs in the 1980s (e.g., confusion between volunteering and unpaid, “black” work) and 1990s legislation have led its exclusion from the volunteering field.

Still today, no significant intermediations exist in this tradition in Italy. Direct voluntary action has no formal structure and it is developed by people by themselves. Nevertheless, new trends reconfiguring this tradition in cognitive and regulative terms have emerged in the last ten years. The adoption of the ILO Manual on the measurement of volunteer work (ILO, 2011) by ISTAT in 2013 and the new legal definition of volunteering provided by the “Third Sector Code” (D.Lgs.117/2017) has given some agencies of the membership tradition the chance to reconsider direct voluntary action.

While elsewhere I have contributed to addressing methodological and substantial issues of the ILO Manual (Guidi et al., Reference Guidi, Guidi, Fonović and Cappadozzi2021), what really matters here are some aspects of the implementation process. The ILO Manual was adopted by ISTAT on the basis of a strong partnership with the CSVs’ national network (CSVnet) and FVP (a research Foundation established by CNV, the NPO leading the above-mentioned 1980s debate). This collaboration enabled the adaptation of the ILO Manual to the Italian context, the data collection and elaboration (Cappadozzi et al., Reference Cappadozzi, Guidi, Fonović and Cappadozzi2021). One of the most relevant aspects of the Manual is that it includes direct action for others outside their own household within the definition of volunteering. This is path-breaking for ISTAT and NPOs. On the one hand, ISTAT endorsed the ILO Manual in response to the UN and ILO call for standardized data on volunteering. On the other hand, CSVs and CSVnet supported the ILO Manual through a new discourse on direct voluntary action. Going beyond an ancient “taboo,” they left the argument of radical alterity and the risks of direct volunteering and reconsidered it as a new frontier to make organized volunteering more accessible (Tabò, Reference Tabò2018).

Results of the ILO Manual implementation in 2014–2016 further encouraged this discourse. Data not only showed that there were 3.03 million direct volunteers in Italy (ISTAT, 2014), but also that about 840,000 have the same cultural and economic background as those in organized volunteering and they commit themselves long term with no organizational intermediations for the collectivity, environment or people outside their own proximity circles. (Cappadozzi, Fonović, Reference Cappadozzi, Fonović, Guidi, Fonović and Cappadozzi2021). This profile of direct volunteers gave CSVs/CSVnet the chance to discover a new target of potential formal volunteers to intercept and, on this basis, to renew their recruitment strategies (Lo Cicero, Reference Lo Cicero2014; De Palma, Reference De Palma2017).

In the same period, further opportunities to reconsider direct volunteering came from the new “Third Sector Code” (D.Lgs.117/2017). This defined a volunteer as a “person who, on the basis of free choice, develops an activity for community and common good, also through a Third Sector body, by making available her/his time…” (art.17, italics added). Although implicitly, the law formally recognizes a person as a volunteer even if she/he acts informally, with no organization. Considering previous formal regulations, this small shift was a true novelty. Regional laws which followed further developed this notion. According to the new Tuscan Law on the Third Sector (L.R.T.65/2020), for example, “the duty of the Region is to support and facilitate structuring processes of individual volunteering.”

In conclusion, direct voluntary action in Italy continues not to have any organizational intermediation and to remain at the margins of the volunteering field. However, CSVs and policy-makers have recently moved toward its effective recognition as volunteering, reconsidering it as an opportunity for the mainstream membership tradition.

The (Emerging) Program-Oriented Volunteering Tradition

A program-oriented volunteering tradition has emerged in Italy since the late 1990s. Scholars, practitioners and the media have given specific initiatives some attention, but neither comprehensive data nor studies exist on it in Italy. As a matter of fact, there are currently so many different and dispersed volunteering programs that systematic knowledge is very difficult. I explored them by means of: (1) a national Seminar (Rome, 2017) and three local Seminars (Bologna, Ferrara, Modena, 2019) with NPOs and CSVs aimed at making examples of volunteering programs emerge; (2) content analysis of the websites of the twenty biggest national associative networks and the CSVs (November 2019); (3) systematic review of documents (2000–2020) archived in the Centro Studi, Documentazione e Ricerche of CSV Lazio, the largest Italian documentation center on volunteering.

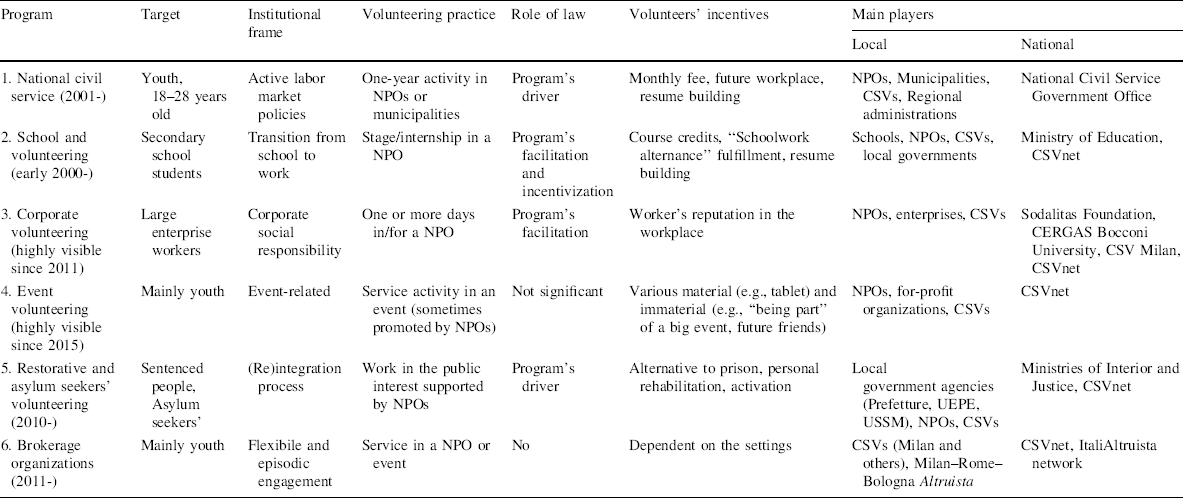

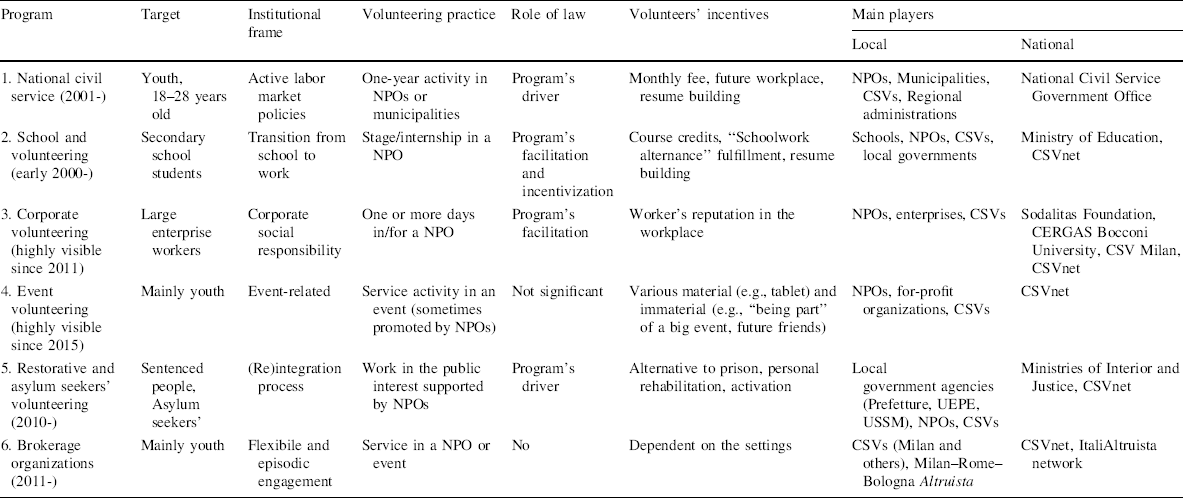

From this analysis (see Table 2 for a synthesis), Italian volunteering programs result aligned with the literature on episodic volunteering: Here voluntary activity is short term, separated from organizational membership and ongoing engagement, and weakly shaped by civic causes or reference to social problems.

Table 2 Volunteering programs in Italy, an initial map

Program |

Target |

Institutional frame |

Volunteering practice |

Role of law |

Volunteers’ incentives |

Main players |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Local |

National |

||||||

1. National civil service (2001-) |

Youth, 18–28 years old |

Active labor market policies |

One-year activity in NPOs or municipalities |

Program’s driver |

Monthly fee, future workplace, resume building |

NPOs, Municipalities, CSVs, Regional administrations |

National Civil Service Government Office |

2. School and volunteering (early 2000-) |

Secondary school students |

Transition from school to work |

Stage/internship in a NPO |

Program’s facilitation and incentivization |

Course credits, “Schoolwork alternance” fulfillment, resume building |

Schools, NPOs, CSVs, local governments |

Ministry of Education, CSVnet |

3. Corporate volunteering (highly visible since 2011) |

Large enterprise workers |

Corporate social responsibility |

One or more days in/for a NPO |

Program’s facilitation |

Worker’s reputation in the workplace |

NPOs, enterprises, CSVs |

Sodalitas Foundation, CERGAS Bocconi University, CSV Milan, CSVnet |

4. Event volunteering (highly visible since 2015) |

Mainly youth |

Event-related |

Service activity in an event (sometimes promoted by NPOs) |

Not significant |

Various material (e.g., tablet) and immaterial (e.g., “being part” of a big event, future friends) |

NPOs, for-profit organizations, CSVs |

CSVnet |

5. Restorative and asylum seekers’ volunteering (2010-) |

Sentenced people, Asylum seekers’ |

(Re)integration process |

Work in the public interest supported by NPOs |

Program’s driver |

Alternative to prison, personal rehabilitation, activation |

Local government agencies (Prefetture, UEPE, USSM), NPOs, CSVs |

Ministries of Interior and Justice, CSVnet |

6. Brokerage organizations (2011-) |

Mainly youth |

Flexibile and episodic engagement |

Service in a NPO or event |

No |

Dependent on the settings |

CSVs (Milan and others), Milan–Rome–Bologna Altruista |

CSVnet, ItaliAltruista network |

Although the heterogeneity of programs is high, some emerging intermediations appear to be relatively clear. NPO activities are the main contexts of voluntary action, but third parties (schools, corporations, institutions) structure short-term experiences in cognitive and material terms according to their own specific missions. The organizations where individuals study/work (programs 2, 3 in Table 2), those facilitating the matching between volunteering demand and supply (6) or the organizers of the events (4) seem to hegemonize the meaning-making of short-term voluntary action and establish its temporal limits. This trend is even stronger when programs (2, 5) are explicitly included in the domain of public policies aimed at increasing employability and social (re)integration.

Educating (young) people in solidarity and involving new (young) volunteers are often at the core of NPOs’ interest in programs, but these objectives are difficult to reach also because personal incentives are center stage. The voluntary action of programs is expected to produce immediate benefits for both promoters and volunteers. This return logic is initiative-dependent, according to the mission of the organization/institution, or shaped by an edonistic culture. Incentives are sometimes (1, 5) so strong that individual action may not be considered free enough for the conventional definitions of volunteering. This tension, however, exists in all the programs.

While no law regulates this tradition, sector legislation significantly matters. Legislation is important for funding (1, 5), (re)framing (1, 5), facilitating (2, 3) and incentivizing (2, 6) the programs. However, this is only partially and, except for 1 and 5, law does not address volunteers’ action and role. In this tradition what is crucial are situated regulations provided by the organizations promoting and managing the program, which usually ask volunteers to carry out precise tasks in clear spatio-temporal conditions, with little room for discussion and creativity.

While conventional membership-based organizations have so far acted in this tradition with an agenda-taking attitude, the role of CSVs appears to be different. Since the early 2000s, several local CSVs have significantly invested in volunteering programs on the basis of a “misalignment hypothesis.” According to this, a growing distance between volunteering associations and young people exists. Associations cannot bridge this gap, and CSVs can help them through volunteering programs (Bonetti & Guidi, Reference Bonetti, Guidi and Ambrosini2016). The CSVs’ role in the programs appears today very relevant and mainly consists in.

1. Promoting the program (1);

2. Scouting opportunities for establishing a program, supporting member associations’ design and program start-up, monitoring and disseminating results in partnership with experts and third parties (3);

3. Designing, promoting (2, 4, 5) and sometimes directly funding and/or managing (2, 4) the program in collaboration with the member associations and/or third parties;

4. Constituting new brokerage organizations (7), in partnership with for-profit organizations, in order to facilitate the matching between the supply of short-term volunteering opportunities and the demand.

At a national level, CSVnet has endorsed and supported CSVs’ volunteering programs, widely disseminated their initiatives and facilitated the exchange of good practices. Through these activities, CSVs and CSVnet seem able to mitigate third-party activism in volunteering programs, thus allowing NPOs to keep some (indirect) control over the programs.

The (Marginal) Organize-it-Yourselves Volunteering Tradition

Organize-It-Yourselves (OIY) volunteering is clearly rooted in Italian contemporary history. At least since the 1970s social movements, grassroots organizations and citizens’ informal groups in Italy have been reported to design, fund, organize and manage everyday activities and services in response to unsatisfied needs (Bosi & Zamponi, Reference Bosi and Zamponi2015; Cattarinussi & Tellia, Reference Cattarinussi and Tellia1978).

Since current OIY initiatives are usually small-scale, bottom-up and often dispersed and temporary, systematic knowledge is impossible and case studies are the only alternative, with obvious limitations. Recent investigations in different realms (Focardi et al., Reference Focardi2006; Paba et al., Reference Paba2009; Guidi et al., Reference Guidi2016) show that people in several OIY initiatives volunteer spontaneously, without a formal membership, but with a high level of commitment to the cause and/or the group, in order to solve a personal and community problem. The settings for individual action are often so informal that the same organizational boundaries are uncertain. People often struggle to define themselves as volunteers since action is highly self-oriented and/or framed as political. People volunteer for very different periods and the end of their engagement sometimes corresponds to the end of the (informal) organization itself.

Both long-lasting (e.g., the weak Italian welfare model) and conjunctural (e.g., natural disasters) conditions constitute the premises for action. There are no specific authorities or laws influencing the OIY tradition. The 2001 Italian Constitutional reform (L.Cost. 3/2001), which gave subsidiarity the highest formal recognition, can, however, be intended as a full legitimation of these initiatives in different fields (Arena & Cotturri, Reference Arena and Cotturri2010). Within current Italian volunteering, the OIY tradition is well established but marginal and challenging mainly because of the informal character of the initiatives and, sometimes, their radical political ethos.

It is difficult to say something general about the OIY tradition beyond this. Further knowledge can be obtained only by focusing on specific initiatives, for example those developed in Italy in the years of economic recession and austerity policies. The latter seem to have peculiarly encouraged OIY volunteering (Bosi & Zamponi, Reference Bosi and Zamponi2019: 43–74), namely within citizens’ collaborative and conflictual initiatives regarding local common goods. On the one side, some have become visible under the umbrella of “administrative collaboration agreements.” Designed and promoted by Labsus, the Italian leading NPO on subsidiarity, these softly regulate the relations between municipalities and citizens with respect to regenerating and managing disused public areas (Labsus, 2018). On the other side, significant direct (co-)production experiences (Bailey & Marcucci, Reference Bailey and Marcucci2013; Andretta & Guidi, Reference Andretta and Guidi2017; Borchi, Reference Borchi2018) have been developed within the urban and rural public spaces abandoned by local institutions. Here activists/professionals restart productions for the benefit of the community and themselves. The action is political and productive, and initiatives establish bottom-up networks (e.g., Genuino Clandestino). In both cases, the (informal) organization emerges as a by-product, originating from the coordination acts of citizens targeting a public area which requires voluntary works to be restored. Some relation between citizens and public authorities is necessary, but this generates neither the stabilization of the partnership nor the formalization of volunteering opportunities.

OIY initiatives are specific, but connected with each other. Serious efforts to renew the general principles of laws and the regulation of the commons have been associated with these experiences from the beginning (Arena, Reference Arena2006; Mattei, Reference Mattei2011; Rodotà, Reference Rodotà2013).

Some conventional NPOs (e.g., ARCI) have supported OIY initiatives at local and national level (e.g., Comitato popolare di difesa dei beni pubblici e comuni). CSVs and CSVnet are also increasingly interested in common good collaborative initiatives. Since 2015, CSVnet has partnered with Labsus, establishing the Italian School for Common Goods and connected local CSV-supported common good initiatives as a way to “consolidate existing ones and promote new ones” (CSVnet President, quoted in Meroni, Reference Meroni2017).

Discussion and Conclusions

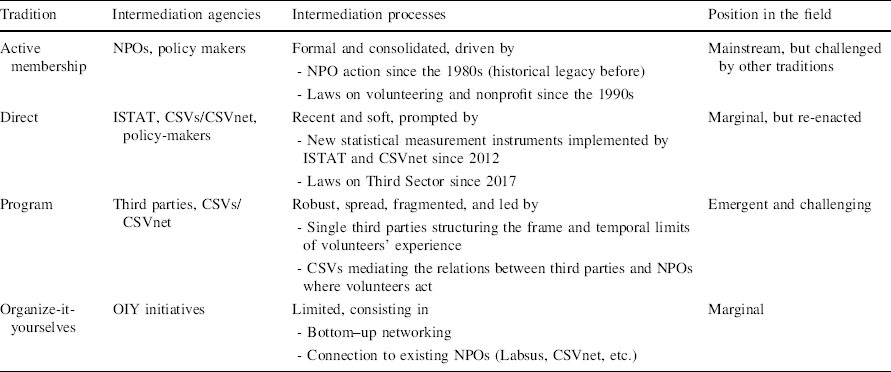

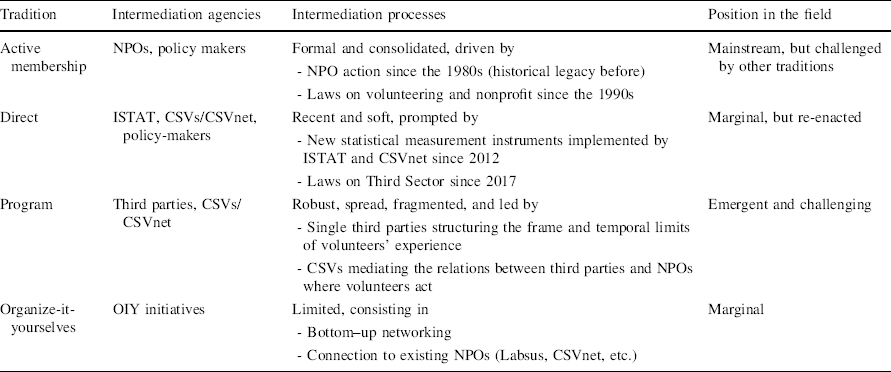

The exploratory analysis shows that in the last 20 years the Italian field of volunteering has become plural and “unstable” to some extent (Fligstein & McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012), with a growing number of agencies intermediating in the demand and supply of volunteering. Four recognizable volunteering traditions now coexist in Italy, each characterized by specific agencies and processes of intermediation. While the active membership tradition still appears to be mainstream, it no longer has the “monopoly” on intermediations and it is “challenged” by other traditions, namely by the program-oriented tradition, whose new intermediations are robust and widespread. Table 3 summarizes the most relevant results.

Table 3 Current intermediations of Italian volunteering, an exploration

Tradition |

Intermediation agencies |

Intermediation processes |

Position in the field |

|---|---|---|---|

Active membership |

NPOs, policy makers |

Formal and consolidated, driven by - NPO action since the 1980s (historical legacy before) - Laws on volunteering and nonprofit since the 1990s |

Mainstream, but challenged by other traditions |

Direct |

ISTAT, CSVs/CSVnet, policy-makers |

Recent and soft, prompted by - New statistical measurement instruments implemented by ISTAT and CSVnet since 2012 - Laws on Third Sector since 2017 |

Marginal, but re-enacted |

Program |

Third parties, CSVs/CSVnet |

Robust, spread, fragmented, and led by - Single third parties structuring the frame and temporal limits of volunteers’ experience - CSVs mediating the relations between third parties and NPOs where volunteers act |

Emergent and challenging |

Organize-it-yourselves |

OIY initiatives |

Limited, consisting in - Bottom–up networking - Connection to existing NPOs (Labsus, CSVnet, etc.) |

Marginal |

On the whole, the Italian case confirms the idea that, far from being disembedded and radically new, late modern evolutions of volunteering are supported by reintermediation processes (Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010) and it prompts the hypothesis that these result also from complex coevolutions between the different traditions of volunteering. The active membership tradition, structured in the 1980s/early-1990s, has significantly affected subsequent evolutions of the field, especially the characteristics of the program-based tradition, although exogeneous factors (e.g., new education policy) are relevant. As feedback, once established, the program-based tradition creates tensions regarding crucial aspects of the active membership tradition (e.g., marginal role of NPOs and relevance of incentives).

Differently from the primary restructuration path illustrated by Hustinx (Reference Hustinx2010), the Italian case shows that “path dependency” mechanisms can be spurious and bring relatively new actors to the fore. Rather than voluntary associations, voluntary service centers (CSVs) and their national network (CSVnet) appear to be the key “institutional entrepreneur” (DiMaggio, Reference DiMaggio and Zucker1988, Thornton & Ocasio Reference Thornton, Ocasio, Greenwood, Oliver, Suddaby and Sahlin2008) in the coevolution of volunteering traditions. Similarly to other peak organizations (Guidi et al. Reference Guidi, Guidi, Fonović and Cappadozzi2021), such actors deserve peculiar attention in the study of the new volunteering intermediations because of their hybrid nature, “in-between” conventional NPOs and third parties. Their history (they were established by the first national law on volunteering in 1991), structure of formal competences and corporate governance (they are second and third level organizations recognized by law and formally entitled to provide organized volunteer services), their resources (they can count on permanent funds by law) and their professional competences (they employ salaried professionals) have enabled them to develop highly legitimized strategies reshaping volunteering intermediations and keeping NPOs connected to new trends. They have acted to reenact and reframe the “direct volunteering” tradition through new data and discourse, to capture and control the trend toward volunteering programs through organization, funding and discourse, to connect (some) OIY initiatives through their visibilization and partnership.

The Italian case also contributes to a better understanding of the criticalities and risks of the new intermediations of volunteering (Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010; Haski-Leventhal et al., Reference Haski-Leventhal, Meijs and Hustinx2010). The action of CSVs and CSVnet in the program-based tradition has limited and conditioned third parties, but they also risk narrowing the room of manouvre for the NPOs being served. While CSVs and CSVnet have acted in the program-based tradition as a professional avantgarde since the 1990s, NPOs appear rather to be agenda takers and are sometimes reduced to being voluntary experience providers. The action of CSVs/CSVnet attempts to put the trend toward episodic volunteering at the service of NPOs, but risks indulging the advancement of governmentality, depoliticization and consumerism (Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010; Eliasoph, Reference Eliasoph2009) and to alter some basic connotations of voluntary action. Considering that “black” and underpaid work is widespread and youth unemployment is high in Italy, monetary and occupational incentives to volunteer may jeopardize the gratuitousness of volunteering and its civic meanings (Overgaard, Reference Overgaard2019).

In conclusion, the Italian case contributes to developing the debate on the reintermediations of volunteering insofar as it shows the existence of an “in-between” model of restructuring, neither driven by voluntary associations nor centered on third parties (Haski-Leventhal et al., Reference Haski-Leventhal, Meijs and Hustinx2010; Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010), but shaped by professional agencies governed by NPOs. On the basis of high levels of legitimation, resources and competences, these agencies welcome societal trends toward individualization and reflexivity and translate them into new, diversified and multifactorial organizational patterns (programs, brokerage initiatives, data sets, etc.) which are expected to serve the renewal of the NPOs. Path dependency is confirmed to be one of the major change dynamics of volunteering (Enjolras & Strømsens, Reference Enjolras, Strømsnes, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018), but in a “spurious” form, that is pivoted on new agencies emerging from the active membership tradition.

The reintermediation processes of volunteering appear, therefore, to be highly context-dependent and resulting from the interplay between collective strategic actors in a structured social arena. This can help future studies to reconsider the magnitude and dynamics of second modernity trends and to tackle continuities and changes in the reintermediation of volunteering in situated and dynamic terms, beyond just the Italian case.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the editors of Voluntas along with the anonymous referees for inspiring and insightful comments. Special thanks to the CSV Lazio - Centro studi, ricerca e documentazione sul Volontariato e il Terzo Settore, namely to Angela Dragonetti and Ksenija Fonović, as well as to Tania Cappadozzi.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università di Pisa within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.