Music has the power to penetrate the mind, and my approach as a composer is to allow it to unveil the unexplainable, free the imagination and keep the audience in touch with the humanity that makes us spiritual and hopefully intelligent beings.

As a composer, over the years, I have found that writing for the stage provides me with an ideal platform with which to address human rights issues. The medium also allows an in-depth exploration of the impact these themes can have on musical dramaturgy.Footnote 1 Music theatre has led me to discover the realm of psychological and emotional states of different archetypal characters who portray real victims of human rights abuse. Through music, they recover their voices and speak to us, even when they have been silenced in real life.

Being a Latin American composer often raises expectations of the type of music the classical music industry expects from me: music that makes reference to rhythmic syncopated ostinatos like those often found in salsa music, or perhaps music that invokes regional traditional Mexican music. This preconception doesn't include an understanding of the rich cultural history that Mexico has to offer. In the works I have written for the stage, I have chosen to address cultural and human rights matters that have made our culture richer and our history a more complex one, without compromising the ongoing exploration in my musical language.Footnote 2

El Palacio imaginado: voices of original cultures of Mexico

My opera El Palacio imaginado Footnote 3 addresses the themes of the neglect of Mexico's original cultures and the growing gap between these communities and the modern world. Here I would like to make a parenthesis to acknowledge the numerous debates that are happening today regarding the correct terminology for communities in Mexico that have always been referred to as ‘indigenous’, which ‘as explained by Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, is an imposed category rooted in oppression and whose definition implies a colonized, marginalized and subdued condition.’Footnote 4

El Palacio Imaginado is also about how impunity has served as a tool of oppression and imposition of colonial values throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The work connects the fate of the oppressed native people with that of women in a male chauvinistic society obsessed with power.

El Palacio Imaginado also explores the richness of the original cultures of Mexico through the diversity of languages that are spoken and written in our contemporary world. To portray the survival of the diverse cultural life in Mexico, languages in the score include Náhuatl, Popoloca, Chinanteco, Tzotzil, and Tzeltal recorded at different locations in Tehuacán, Tepoztlán and Mexico City, and contemporary poetry in Mazateco by Juan Gregorio Regino, in Zapoteco by Natalia Toledo, and in Maya by Briceida Cuevas Cob. The setting of texts taken from the ancient compilation of Mayan spells, El Ritual de los Bacabes, gives a historical perspective as well as commenting on different moments throughout the dramatic development of the opera. Each of the poems included in the opera makes a commentary on what is happening at a particular moment in the story. All this material was processed at the Experimental Studio of the Südwestrundfunk (SWR) in Freiburg into an eight-channel tape that surrounds the audience. At different moments throughout the opera, these voices are not seen but heard from different places in the hall, making their presence felt among the listeners (who are not able to discern where they come from).

Sound example 1. El Palacio Imaginado, act 1, https://soundcloud.com/user-471956334/palacio-imaginado-act-l

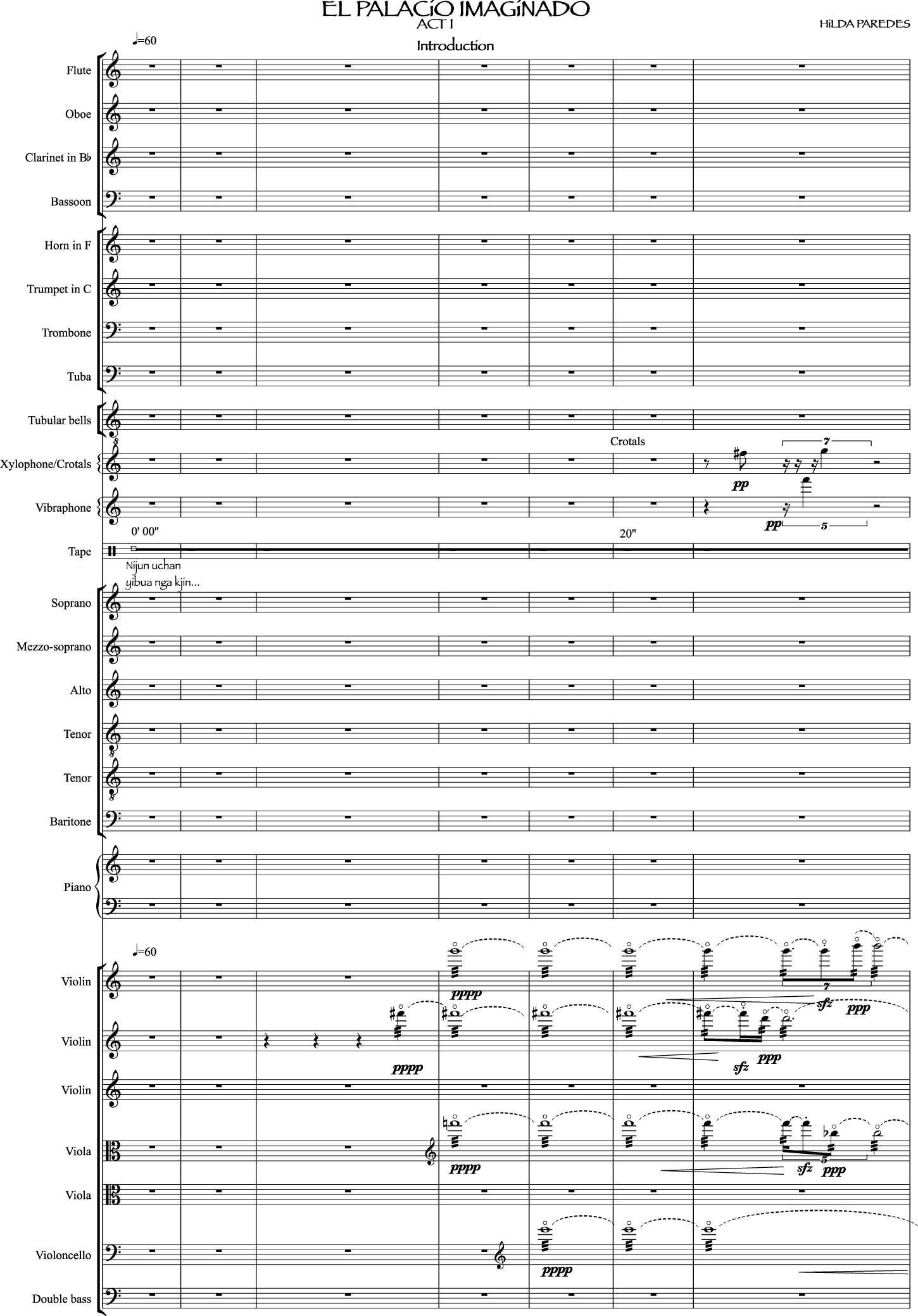

Example 1. Introduction of El Palacio Imaginado in 2003 production, directed by Carlos Wagner.

The introduction (see Examples 1 and 2 and Sound example 1), which makes up the first five minutes of the work, depicts a fictional place – which could be anywhere in Latin America – where the original population has been living for several thousand years. These people are an ancient community, so poor that no one has bothered to extract taxes from them, and so meek that they have never been recruited for war. Gradually, the natives who did not die in slavery, from torture, or as victims of unknown illnesses, scattered deep into the jungle. ‘Always in hiding, they survived for centuries. They came to be so skilful in the art of dissimulation that history did not record them.’Footnote 5 To describe the historical and cultural diversity of this place, the opera opens with poems, heard on tape as read by their authors. These poems are then superimposed on top of the instrumental writing and combined with other voices recorded and treated in the studio, as well as a setting of a fragment of an ancient Mayan spell from the compilation El Ritual de los Bacabes:

Example 2. El Palacio Imaginado, act 1, bb. 1-7.

Opening poem: ‘Nijun uchan yibua nga…’ by Juan Gregorio Regino:

Followed by ‘Yan maax tu..’ by Briceida Cuevas:

Followed by a setting taken from El Ritual de los Bacabes:

These voices set up the aural and dramatic landscape before the inaugural speech of the Benefactor, the dictator of the nation and main character in the opera. He proudly builds a Summer Palace in a country where seasonal changes are barely perceived. The palace represents an obsessive dream, in which the First World has become the model of a cultural project that denies the historical reality of its social structure and thus does not accept the possibility of building a future based on its reality. The only way of existing is to become invisible.

The voices that surround the audience are portrayed as ghosts, only perceived by Marcia, the wife of Ambassador Liebermann who, much to his dismay, was sent by his government in the First World to this Latin American country.

Marcia has learnt some Spanish and contrary to her husband, she is fascinated by the new land and what it has to offer. By the time they arrive, the Benefactor has become an old man and at the reception in Scene 3 of Act I he becomes attracted to Marcia. The Benefactor is proud of never having been married, and every woman he wanted was brought to him by his guards and disposed of after fulfilling his pleasure. This is what happens at the end of Act I when his guards come to take Marcia away in the same manner as many of the disappeared have been taken from their homes in many countries of Latin America.

Act II opens with an attempted rape scene followed by Ambassador Liebermann coming to reclaim his wife from the Benefactor. He proceeds to persuade Liebermann with threating innuendos to leave the country in order not to spoil the good relations between their nations for a trifle. As Liebermann departs, the Benefactor feels free to do as he pleases with Marcia and takes her to his Summer Palace where she becomes more aware of the unseen but heard voices of the natives.

For the last scene of this Act (Examples 3 and 4), the score combines a superimposition of different languages (mostly Popoloca and Nahuatl) on tape and a setting of a spell taken from El Ritual de los Bacabes, with Marcia standing up for herself and joining the native community of voices:

Example 3. El Palacio Imaginado, end of act II. Production directed by Carlos Wagner.

Example 4. El Palacio Imaginado, end of act II, bb. 645-647.

From El Ritual de los Bacabes:

In this way the opera connects the fate of women to that of communities that have been reduced to shadows. The last voice we hear in this scene is that of the poet Natalia Toledo reading her poem in Zapoteco:

Act III is the shortest of the opera. It fast-forwards to a democratic country but with the same colonialist ideology towards the original communities. The Ministry of Culture decides to create an Art Centre at the Benefactor's old Summer Palace to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of democracy. A crew of representatives is sent to find the Palace but alas, it cannot be found. Only after a rain, rising through the hot steam of the jungle, a shade of the Summer Palace lifts up only to disappear into the land as we hear the closing voice of Juan Gregorio Regino reading his poem in Mazateco:

La tierra de la miel: a lost land, a lost voice

In La tierra de la miel,Footnote 12 the abuse of women parallels the repression of original communities as they become the subjects of human trafficking and sexual exploitation.

In 2012, I was asked to collaborate on the project Cuatro Corridos (Four Corridos), a music theatre project created in San Diego under the direction of Susan Narucki. La tierra de la miel is part four of this collaborative project.Footnote 13 Each part was to be composed by a different composer on a part of the libretto written by Mexican writer Jorge Volpi. This project is based on real events. It tells the story of women brought into the United States and trapped in a cycle of prostitution, human trafficking, and slavery around the U.S./Mexico border in San Diego and Tijuana.Footnote 14

The story is told by four of its central characters: a female member of the Salazar Juárez brothers’ kidnapping ring (Dalia); a Chicano policewoman in San Diego, who discovers the ring (Rose); and two of the victims, both young women from Tlaxcala forced to work in the Fields of Love (Azucena and Violeta). Each participant composer wrote the music for one of the characters: Hebert Vázquez wrote the music for Azucena, the character for Dalia had music by Arlene Sierra, and Lei Liang wrote the music for Rose. My contribution was a setting of young Violeta's story about her friend Iris, who couldn't bear the abuse, and was murdered as she tried to run away.

The text by Volpi also gave me the possibility to address the embedded idea in the minds of so many migrants who look for a better life across the border, given the lack of possibilities to survive in their own country. This is why I chose to highlight one of Volpi's verses as the title for my piece: La tierra de la miel (The Land of Honey):

Iris had not yet turned twenty

she was slender with big dark eyes

she liked chocolate

and wandering off in the fields.

Her father told it to her straight:

‘To a land of honey you go

to earn lots of dollars’.

So Iris went off with the men

as her father told her to do

with a smile on her face.Footnote 15

These are the words that Iris’ father tells her to persuade her to go away with the men who will ultimately rape her and force her into prostitution once in the U.S.

In the many years I have worked on setting poetry to music, I have learnt how music can provide the means of finding multiple meanings that transcend the semantic realities of poetry. When working with text and music, two different semantics are at play: that of the text and that of the music created by the composer. When I work with characters on stage, I always have to go further to allow the music to penetrate the minds of those characters. Understanding these women, who were kidnapped or sold and taken from their homeland, means getting in touch with the abuse they are subjected to and its consequences. Abuse and exploitation destroy the soul and the inner self is broken into pieces; language is lost, and the ability to articulate words is disabled. As illustrated by one rape victim:

After my assault, I had frequently had trouble speaking. I lost my voice, literally, when I lost my ability to continue my life's narrative. I was never entirely mute, but I often had bouts of what a friend labeled ‘fractured speech’, in which I stuttered and stammered, unable to string together a simple sentence without the words scattering like a broken necklace.Footnote 16

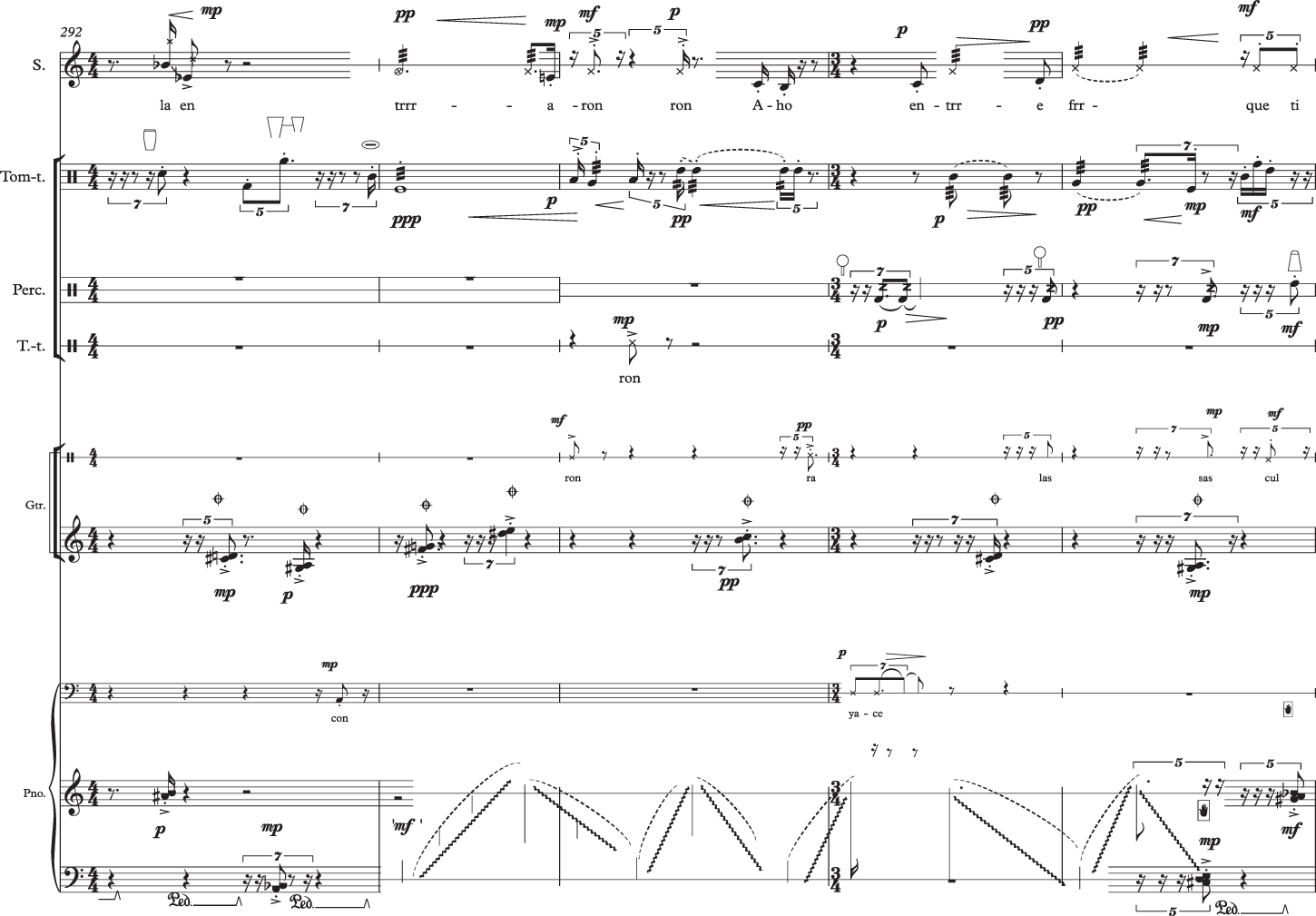

In La tierra de la miel, language is destroyed, and the remaining fragments are distributed between the voice of the singer and members of the ensemble (see Example 5). By destroying language, the music plunges into the psychological and emotional state of the character and enables the pain of the victim to be heard. This was my quest when I undertook this project. Whilst setting text to music I have found that phonetics also enriches my compositional palette through using different instrumental techniques which enhance specific phonemes. In Example 5, incorporating noise as a means to destroy pitch is coherent with the musical dramaturgy of the soul destruction of these victims.

Example 5. La tierra de la miel, bb. 292-296. © UYMP.

Sound example 2. La tierra de la miel, video of the production by the music theatre class at the Hochschule für Musik und darstellende Kunst Stuttgart performed at the ‘Sommer in Stuttgart’, 13–14 June 2015, https://youtu.Be/S5HVph2xPaU

As librettist Jorge Volpi writes,

in pre-Hispanic times, the village of Tenancingo in the Mexican state of Tlaxcala—then an independent dominion—was characterized by a strange and obscure tradition: the rearing of prostitutes to be sold or handed over to the enemy, generally a rival Nahuatl tribe. The girls were chosen in early childhood and brought up especially for the purpose.Footnote 17

What was unveiled by the US police in dismantling the Salazar Juárez gang is that

this appalling tradition continues, except that now it is the parents themselves who send off their daughters to swell the ranks of the prostitutes. For years now, there has existed a human traffic between this small village and the U.S.-Mexico border, in which young women are sold and exploited by mafias to serve as prostitutes for illegal migrant workers in southern California.Footnote 18

As Nahuatl is the mother tongue of many of these girls, I have chosen to give voice to Iris’ soul in this language, as she sings from the afterlife, enhanced by the cultural reference of the incorporation of the teponaztli (log drum) to end the work (Example 6).

Example 6. La tierra de la miel, bb. 308-314. © UYMP.

El Palacio Imaginado provided me with a platform with which to explore critical political, gender and human rights issues. In La tierra de la miel, I was able to continue addressing these issues. The project also gave me the opportunity to allow music to give voice to the many women that have been raped and murdered at the U.S.-Mexico border for decades, without most perpetrators ever being brought to justice.

Harriet: coded messages for freedom

In 2012, as we were rehearsing in Vermont for the premiere of La tierra de la miel, we received the news that Jorge Volpi was to become the next Director of the Festival Internacional Cervantino in Guanajuato (Mexico). He immediately decided to commission six new operas from different Mexican composers. My contribution would be performed in the 2018 edition of the Festival.

As the Festival had limited resources for these projects, I soon realised I had to write a work which would use minimal forces. This was when I contacted the Afro-American soprano Claron McFadden, whom I had known for many years but never had the chance to collaborate with. My proposal to her was to write a monodrama where she would be the soloist. She introduced me to the life of Harriet Tubman and a journey of discoveries began. I also realised that the new project was going to give continuity to subject matters that have been important for me throughout my life.

Harriet: Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman, Footnote 19 which was completed and premiered in 2018, followed La tierra de la miel. The opera is based on the life of Harriet Tubman (1822–1913), a former slave who became a fugitive from slavery and one of the most important abolitionists before the American Civil War. The work was commissioned by Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Festival Internacional Cervantino, Muziekgebouw aan ‘t IJ and Muziektheater Transparant. The libretto was based on poems written by Mayra Santos-Febres specifically for the opera and on a selection of dialogues by Lex Bohlmeijer.

Born on a plantation in Maryland, Harriet Tubman successfully escaped to the North in 1849. She came back a year later to free family members and friends, and this was followed by a string of journeys helping many other runaways. In this process she became the leader of an antislavery network called the Underground Railroad. She was never caught and was very proud of never having ‘lost a passenger’. Her success was due to the different hiding tactics she used, a parallel to how hiding has become a means of survival in many communities throughout the world. Such has been the case with original cultures in Mexico and Latin America for centuries as well as with women under the Taliban in Afghanistan in the 1980s, just to mention a couple of examples.

Like most slaves, Harriet was illiterate, so she and her collaborators had to devise a coded way to communicate and send messages to each other. This was done through music: several spirituals that are well known to us today, such as Steal Away, Wade in the Water, Go Down Moses, and Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, carried a specific code with instructions for the runaways on what to do or when to get ready to go.

In the process of doing the research for this opera, these tunes and their implicit function in Harriet's hiding tactics became a wealth of inspiration for the dramatic musical development of the work. They gradually became a big part of Act II, which is about Harriet's activities as a leader of the Underground Railroad.

Act II explores many of the hiding tactics and codes that were sent with each of these tunes. It is also important to underline that this material is integrated as the melodies appear and disappear according to the direction of the development of the musical dramaturgy. They are not merely illustrative: they are part of the tale being told by the music.

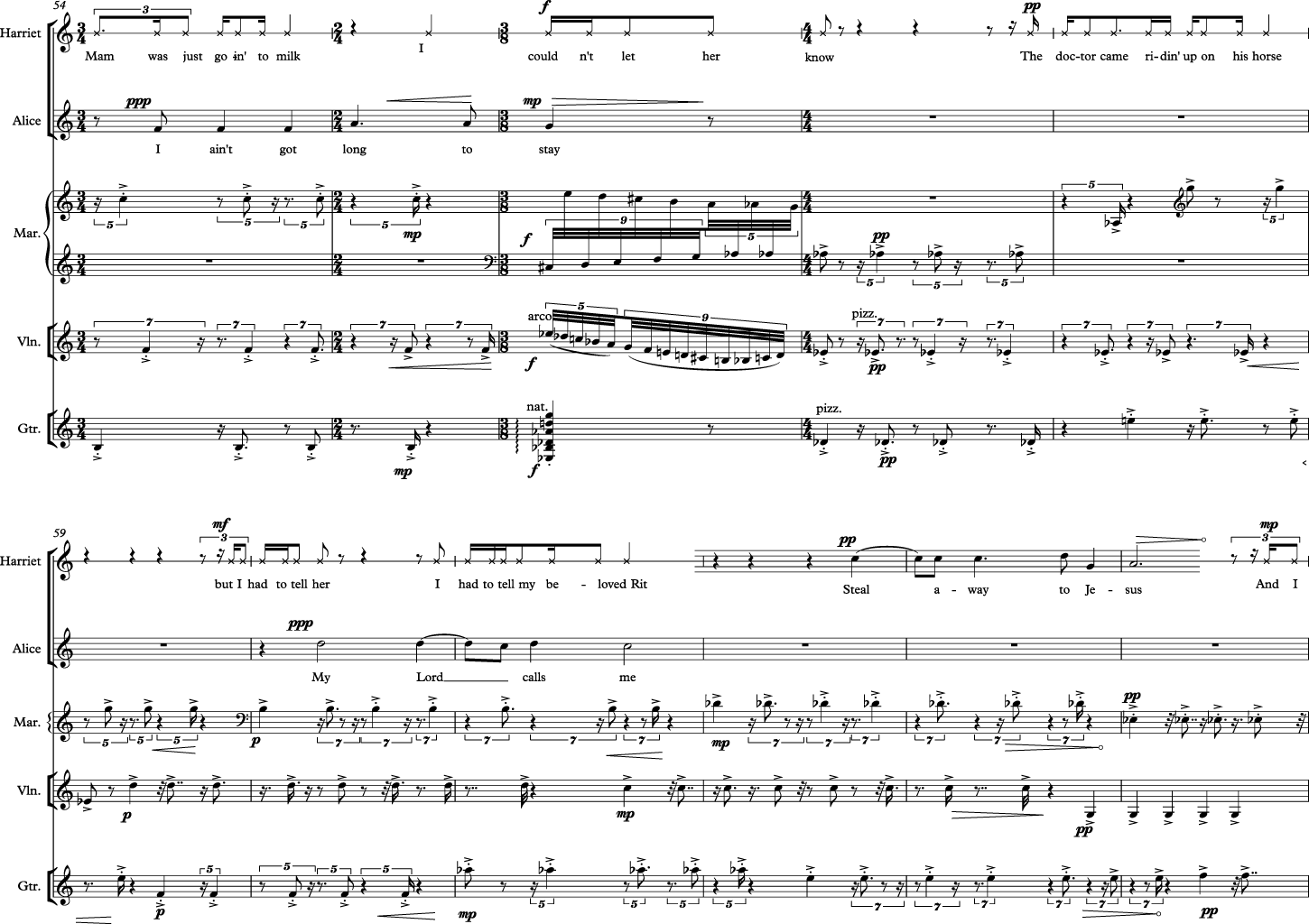

As music can penetrate the psychology of the characters portrayed, it enabled me to superimpose two contrasting ideas at the beginning of Act II. As Harriet gets ready to leave the plantation for the first time, she listens to the call of Steal Away letting her know she needs to get ready to go; her heartbeat speeds up with fear as a counterpoint idea to the melody. This pulse becomes an important musical idea throughout the whole of Act II (see Example 7 and Sound example 3).

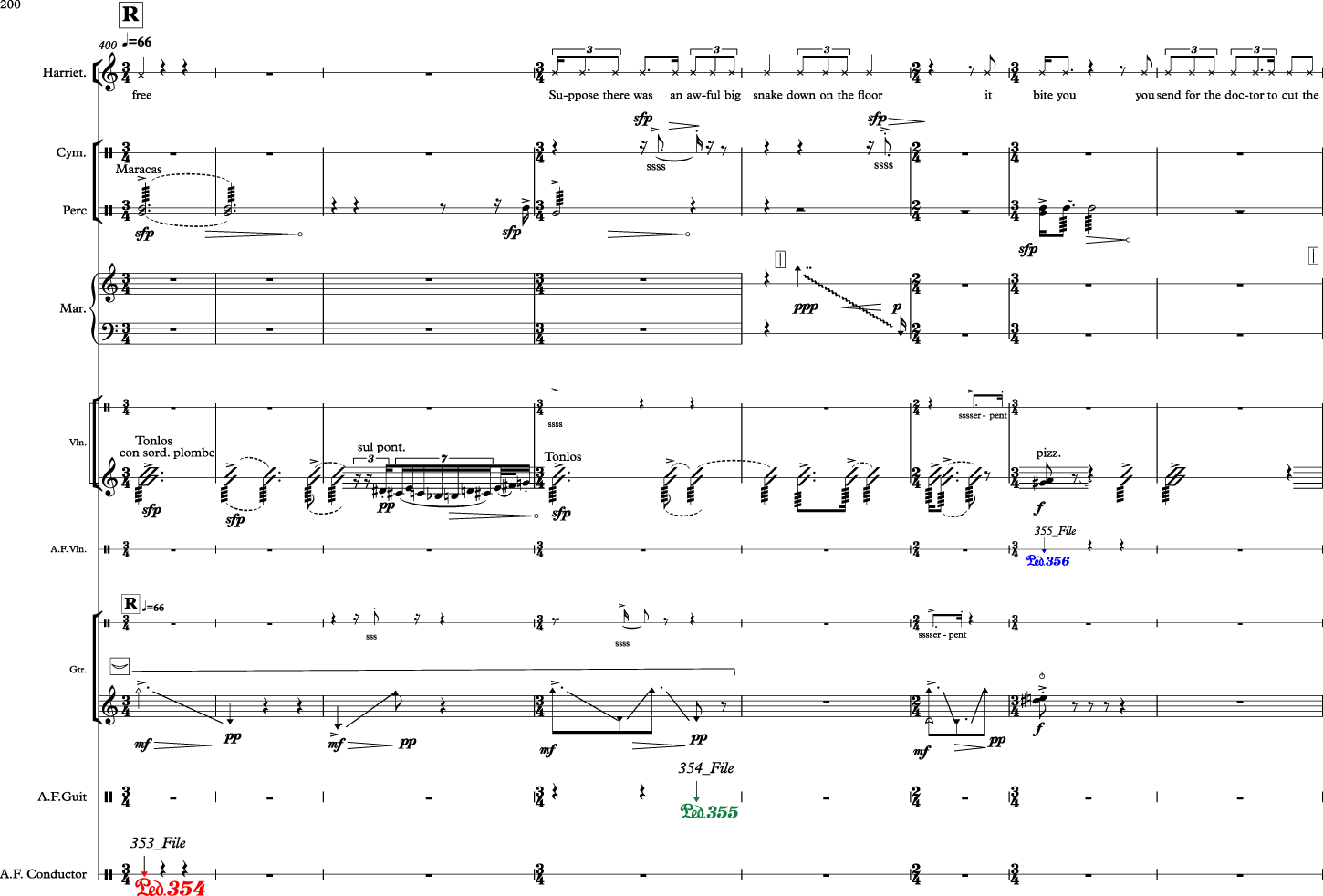

Example 7. Harriet, Act II, bb. 54-64. © UYMP.

Sound example 3. Harriet, Act II, Scene 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eScis8F4TKQ&t=232s

As part of the research process that was undertaken for this project, many quotes attributed to her make up the basis of the libretto. An example is the end of Act IV (Example 9), which quotes her message to President Abraham Lincoln (Example 10):

I am a poor negro

But the negro can tell master Lincoln

how to save money

and young men's lives

God won't let master Lincoln beat the South

till he does the right thing.

He can do it

by setting the negro free.

Suppose that was an awful big snake down on the floor.

He bite you.

You send for a doctor

to cut the bite;

and while the doctor doing it,

the snake springs up and bite you again;

so it keep doing it, till you kill it.

That's what master Lincoln ought to know.Footnote 20

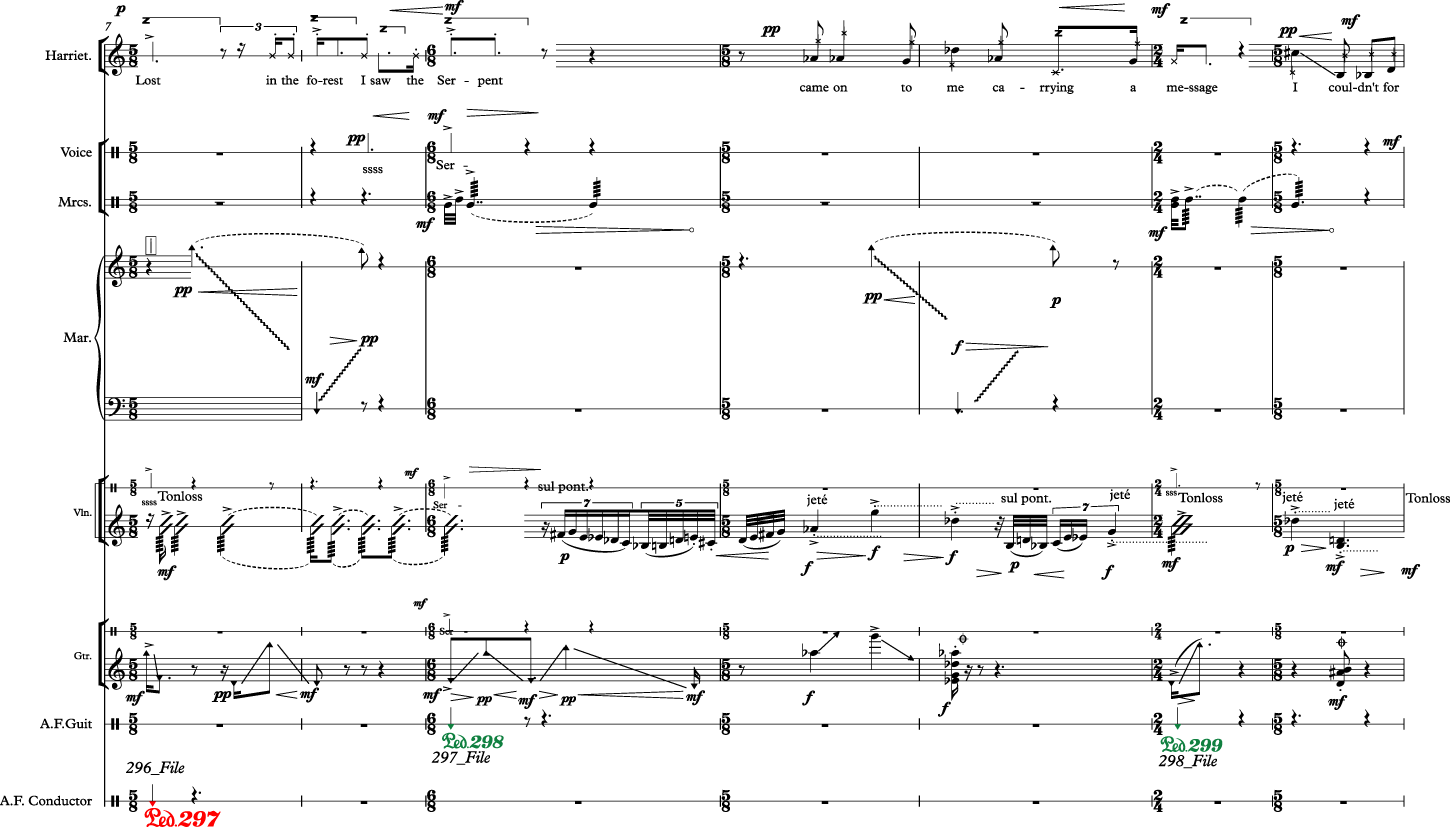

The first seven lines are spoken without music, and on the word free the music sparks off making reference to the musical idea which opened Act IV (Example 8), which also mentions the metaphor of a snake to refer to John Brown, one of the leading white abolitionists of the movement that led to the Civil War.

Example 8. Harriet, Act IV, scene 1, bb. 7- 13. © UYMP.

Example 9. Harriet, end of Act IV. ©Koen Broos.

Example 10. Harriet Act IV, scene 4, bb. 400-407. © UYMP.

This is followed by an Epilogue which consists of a brief outline of the heritage that this extraordinary woman passed on to the civil rights struggle in the US of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The last words attributed to her – ‘I got to prepare the road for you, so you can walk your very own walk'Footnote 21 which open the work and close Act III, give a perspective on the importance of the path she paved for the centuries that followed. As part of the material incorporated here, I chose to use a message emulating an announcement: ‘The Underground Railroad has not yet arrived at its destination’, which proceeds to echo in the fabric of the musical material. The music here is built on electronic and instrumental material used throughout the opera and throws a new light to close the work (Example 4).

Example 4. Harriet, Epilogue, https://youtu.Be/zZzx5Vykaoc.

Conclusion

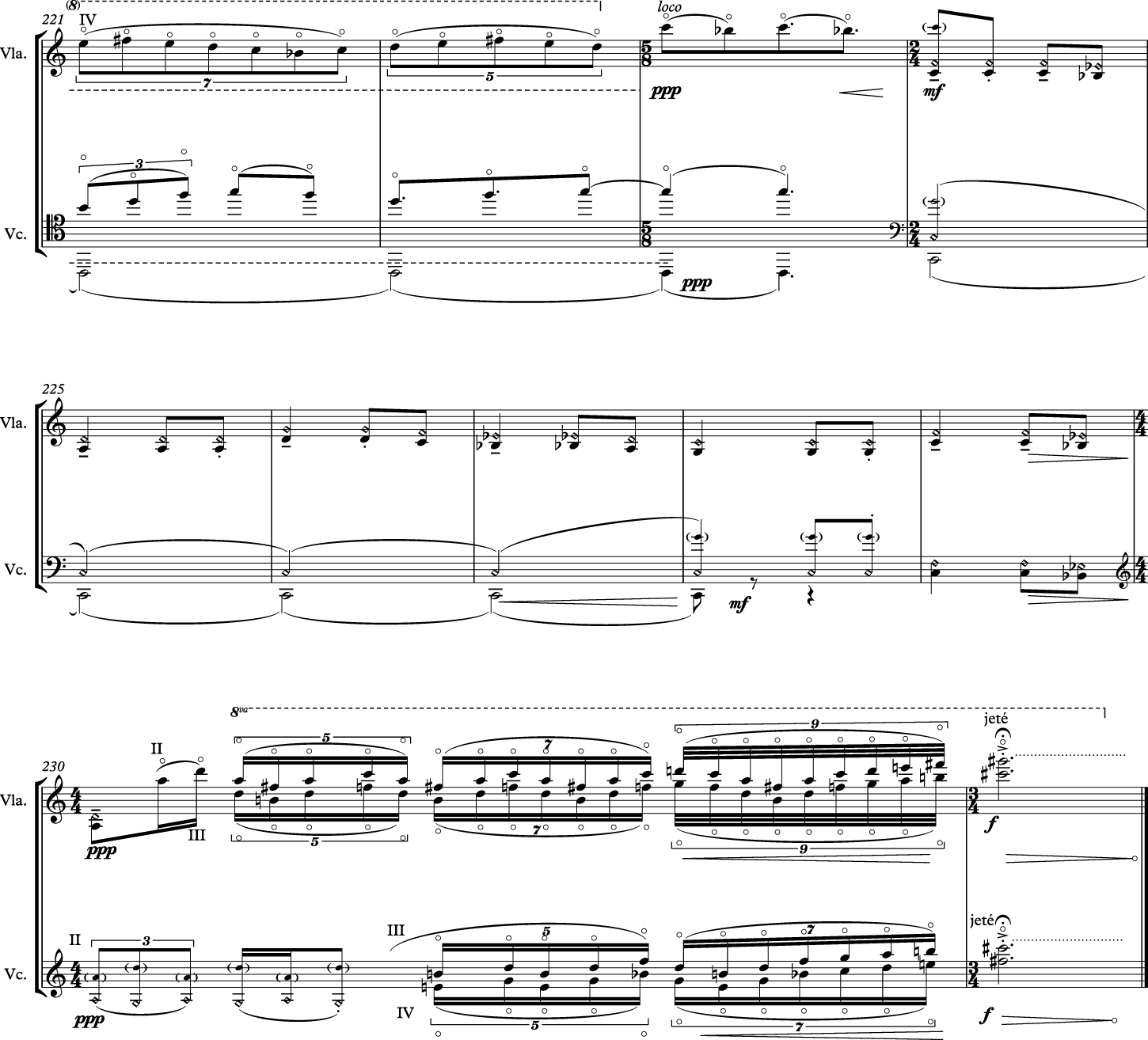

All three works mentioned here have nourished my creativity and I have now found ways to explore social and humanitarian issues in my recent chamber music as well, without necessarily setting words to music. Two recent examples are Juegos prohibidos (Forbidden Games), a trio for clarinet, cello and piano from 2019,Footnote 22 and Serpientes y escaleras (Snakes and Ladders) for viola and cello, completed in 2018.Footnote 23 Both works incorporate Mexican and Latin American traditional children's songs as the musical dramaturgy makes reference to the children in detention at the border between Mexico and the U.S. at the time when both works were written.

Juegos prohibidos was commissioned by clarinetist Vincent Dominguez for his Ph.D. exam at Arizona State University, with the stipulation to write a work that would make reference to political or social issues in the Mexican community in the U.S. For this score, I picked a quote of Dale, dale normally sung to entice people to break the piñata (Example 11):

Example 11. Dale, dale, transcription by the author.

The words translate as:

Come on, come on, come on, don't lose your aim,

because if you lose it, you lose your way.

The tune given to the cello in pizzicato is constantly fractured by the flow of the music (Example 12):

Example 12. Juegos prohibidos, bb. 96-102. © UYMP.

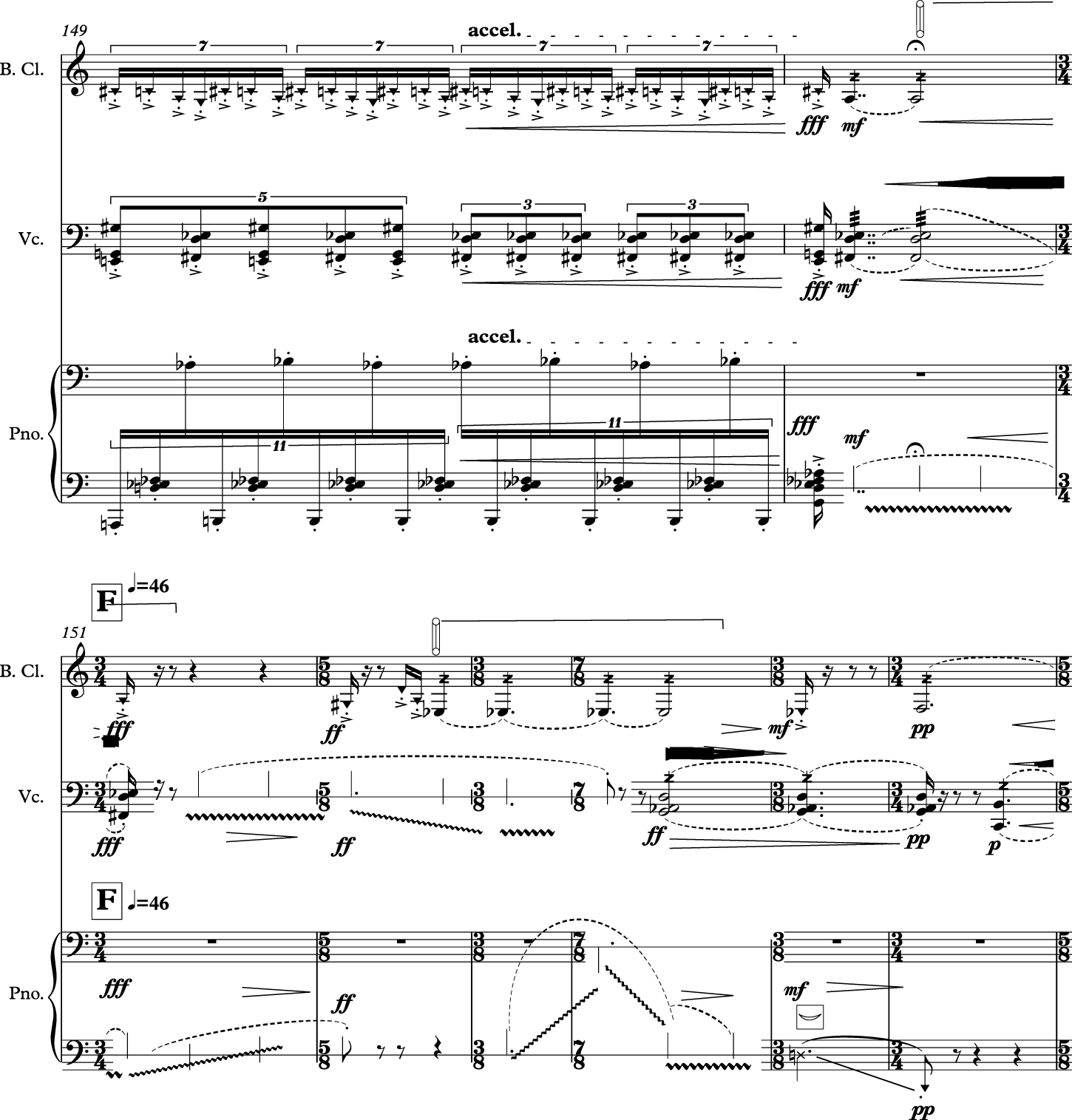

As in La tierra de la miel, the score of Juegos prohibidos undergoes a process of transformation towards the destruction of pitch, in this case by means of loud multiphonics on the bass clarinet, bow overpressure on the cello, and scratching of the strings on the piano to symbolize the destruction of childhood (Example 13).

Example 13. Juegos prohibidos, bb. 149-156. © UYMP.

At the end of the work, we hear a fragment of the South American lullaby Duerme negrito, to farewell the many Latin American childhoods lost at the border of the U.S. (Examples 14 and 15).

Example 14. Juegos prohibidos, bb. 167-173. © UYMP.

Example 15. Juegos prohibidos, bb. 194-end. © UYMP.

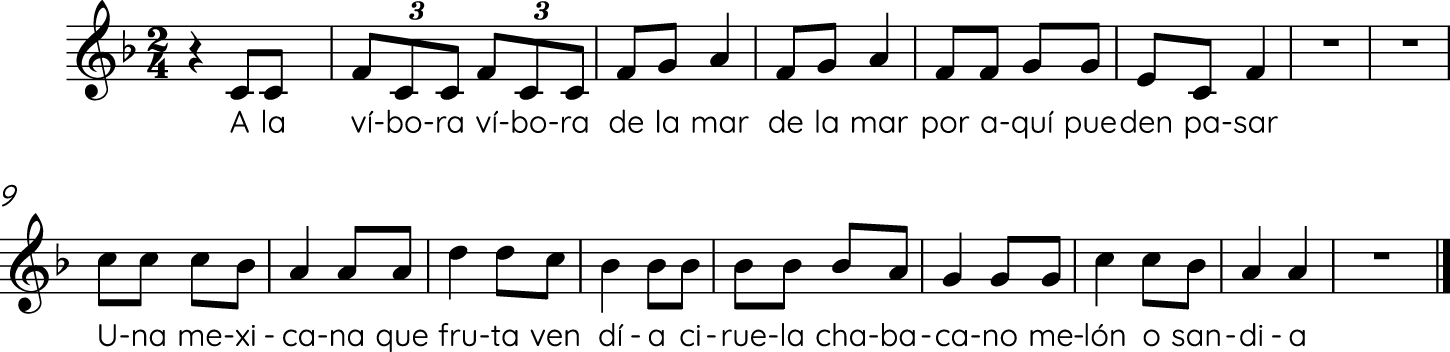

Written a year earlier in 2018, Serpientes y escaleras was commissioned by Karla Hamelin and Ames Asbell, two young players from Texas State University. The request was also to write something that would be relevant to the social and political situation near the border with Mexico. For Serpientes y escaleras I included what I thought were two relevant fragments from a Mexican nursery game, La Víbora de la mar (Example 16):

Example 16. La Víbora de la mar, transcription by the author.

The lyrics can translate as:

The viper, viper of the sea, this way you can pass..

A Mexican woman who sold fruit, plum, apricot, melon or watermelon.

As in Juegos prohibidos, in this score every attempt for the first quote to continue is interrupted (Example 17):

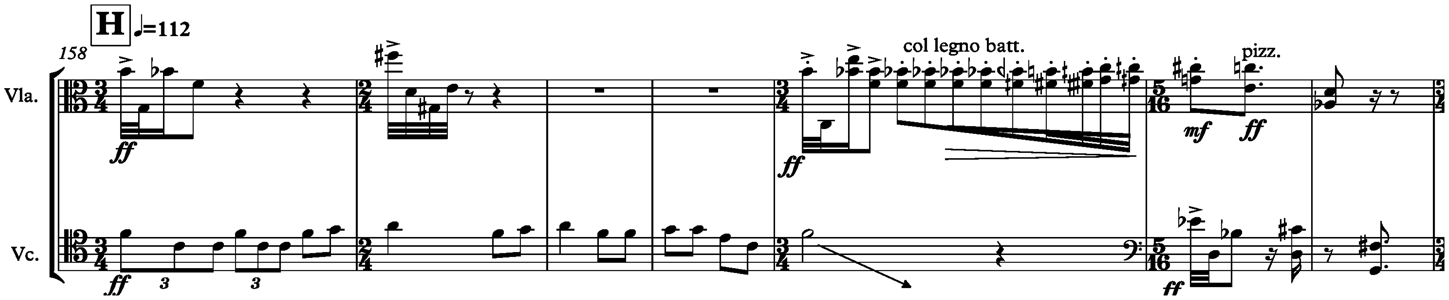

Example 17. Serpientes y escaleras, bb. 158-164. © UYMP.

The work ends with the second fragment of the tune which vanishes into harmonics, like a lost hope (Example 18):

Example 18. Serpientes y escaleras, bb. 221-end. © UYMP.

In my next opera project, I am planning to explore issues of integration of people with Down syndrome in a society that has ignored them and failed to understand what they can offer to our highly overachieving race obsessed with success. This is a libretto about a dystopian society and an alternative planet ruled by ministers with Down syndrome proposing that it is necessary to have an extra chromosome to get rid of human cruelty and prevent wars. This is the first time I wrote my own libretto (during the first COVID-19 lockdown), and at the time I am writing this, I am hoping to raise some interest from opera producers.

As a composer, I believe that it is important to raise awareness of human rights issues in the concert hall. Music has the power to bring to the forefront the poignant emotions that make us all human. Music can give voice to those whose voices have been shattered and can connect us with the humanity that we all share. In my opinion, my role as a composer is to allow music to guide me towards bringing human spirituality to the foreground, in an effort to reach those that cannot be listened to and to give them a voice that will speak to us. Perhaps music can allow us to listen to what cannot be heard and connect the inner souls of those who have been silenced with those that came after.

Funding statement

This work was financially supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 101027828 (project ONTOMUSIC), the Schulich School of Music of McGill University and the Canada Research Chair in Music and Politics at the Université de Montréal Faculty of Music. The funding bodies played no role in the development of this article, which reflects only the author's view.

Firmly established as one of the leading Mexican composers of her generation, Hilda Paredes (Mexico/UK, b. 1957) has been based in the UK for over four decades. Her music has received many international awards from the PRS for Music Foundation, the Gwärtler Stiftung in Switzerland, the Sistema Nacional de Creadores in Mexico, the J. S. Guggenheim Foundation, and more recently the Koussevitzky Foundation. In 2019, her opera Harriet won the Ivors Composers award. After studying composition at the Conservatoire in Mexico, she graduated from the Guildhall School of Music, obtained her MA at City University, London and her PhD at the University of Manchester. Paredes’ music has been commissioned and performed by many prestigious ensembles, orchestras and soloists and has been widely performed at important festivals around the world. https://hildaparedes.com/