Introduction

The rice (Oryza sativa L.)–wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cropping system (RWCS) is crucial for global food security, providing staple foods to a significant portion of the world’s population. It supports the livelihoods of millions of farmers, contributing to stable incomes while benefiting a wide range of stakeholders across the agricultural value chain (Dhanda et al. Reference Dhanda, Yadav, Yadav and Chauhan2022). As one of the most widely cultivated and technologically advanced agricultural systems globally, RWCS covers approximately 13.5 million ha in Asia, with South Asia accounting for 57% of this area. Notably, more than 85% of South Asia’s RWCS is concentrated in the Indo-Gangetic Plains (Banjara et al. Reference Banjara, Bohra, Kumar, Ram and Pal2021). Rice is the staple food for more than half of the world’s population, feeding more than 3.5 billion people globally (Hashim et al. Reference Hashim, Ali, Mahadi, Abdullah, Wayayok, Kassim and Jamaluddin2024). Wheat is consumed by approximately 2.5 billion people across 89 countries (CAS 2020).

Following the Green Revolution, wheat production in South Asia experienced a significant increase, driven by the adoption of high-yielding varieties, the use of recommended chemical fertilizers, improved irrigation systems, and the implementation of advanced farming technologies (Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Ravichandran and Antony2019). However, in recent years, this growth has slowed (Ray et al. Reference Ray, Mueller, West and Foley2013). This slowdown is mainly due to emerging challenges such as persistent weed infestations, delayed wheat planting after rice harvest, rising soil salinity levels, soil compaction caused by rice puddling, and the prevalence of crop diseases. Among these issues, weed infestation remains one of the most serious threats to both rice and wheat crops (Nakka et al. Reference Nakka, Jugulam, Peterson and Asif2019).

Seed germination, a crucial phase in a plant’s life cycle, is intricately influenced by various factors like dormancy, temperature, moisture, oxygen, and light. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts a temperature increase of approximately 2 to 4 C by the period 2090 to 2099 as an outcome of greenhouse gas emissions (AGMIP 2017). Temperature plays a key role in seed germination in wet soil, affecting how seeds emerge. Light serves as a signal influencing germination, particularly in photoblastic seeds. Seed dormancy, allowing seeds to remain viable for extended periods, is a significant trait in many weed species, impacting their success (Bradford Reference Bradford2018).

Traditionally, rice required flooded fields and wheat needed finely tilled soil, but recent advances show rice can thrive with direct seeding or non-puddled transplanting, and wheat performs well under no-till conditions provided that integrated weed management (IWM) is properly implemented to achieve higher yields (Nawaz et al. Reference Nawaz, Farooq, Nadeem, Siddique and Lal2019; Panneerselvam et al. Reference Panneerselvam, Kumar, Banik, Kumar, Parida, Wasim, Das, Pattnaik, Roul, Sarangi and Sagwal2020). The productivity of wheat is adversely affected by several weed species, primarily littleseed canarygrass (Phalaris minor Retz.), lambsquarters (Chenopodium album L.), and wild oat (Avena fatua L.). Collectively, these weeds contribute to a significant yield loss ranging from 15% to 50%, and in some cases, exceeding 60% when weed growth is not controlled (Gharde et al. Reference Gharde, Singh, Dubey and Gupta2018). However, the extent of yield reduction due to weeds depends on factors such as the composition of weed flora, weed density, and duration of weed invasion. In addition to causing yield losses, certain weeds also pose challenges during threshing and harvesting procedures. For example, a heavy influx of P. minor in the wheat crop’s maturity stage can cause significant lodging, severely affecting yield (up to 50%) and harvest efficiency (Gherekhloo et al. Reference Gherekhloo, Osuna and De Prado2011).

Growing the same crop continuously in a cropping system leads to the dominance of well-adapted weeds. Different cropping systems, influenced by agronomic practices, also favor specific weeds. For example, the rice–wheat system tends to promote grassy weeds (Shahzad et al. Reference Shahzad, Farooq and Hussain2016). These resilient weed species, adapted to certain systems, pose challenges for existing weed management practices, as they may exhibit herbicide resistance and contribute to increased labor costs and environmental pollution. Physical or manual weed control, considered the most viable choice, is hindered by rising costs and labor shortages. Consequently, alternative weed management approaches are essential (Vasileiou et al. Reference Vasileiou, Kyrgiakos, Kleisiari, Kleftodimos, Vlontzos, Belhouchette and Pardalos2024).

Ecological strategies are critical and may involve sowing weed-free seeds, adjusting sowing times, employing cultivation and crop rotations, and utilizing the stale seedbed technique, along with understanding weed biology (Ali et al. Reference Ali, Afzal, Khaliq and Naveed2024) and offering non-chemical alternatives for effective weed management. Understanding weed ecology helps to exploit weaknesses for better management. Population-based models, such as hydro-time and thermal time, shed light on germination patterns, contributing to species fitness. Predicting species’ responses to climate change is crucial, and models like hydrothermal time are very effective in understanding and managing weed germination across diverse environments (Donohue et al. Reference Donohue, Liana, Burghardt, Daniel, Bradford and Schmitt2015). Therefore, this review paper centers on reevaluating weed management practices, emphasizing the exploration of effective ecological methods for weed control. Specifically, it seeks to utilize population-based threshold germination models to improve and optimize weed control methods within the framework of ecological approaches for managing weeds in wheat and rice fields, with a particular focus on the RWCS.

Challenges in the RWCS

The RWCS faces challenges that highlight the need for integrated and adaptive solutions.

Alterations in the Composition of Weed Species

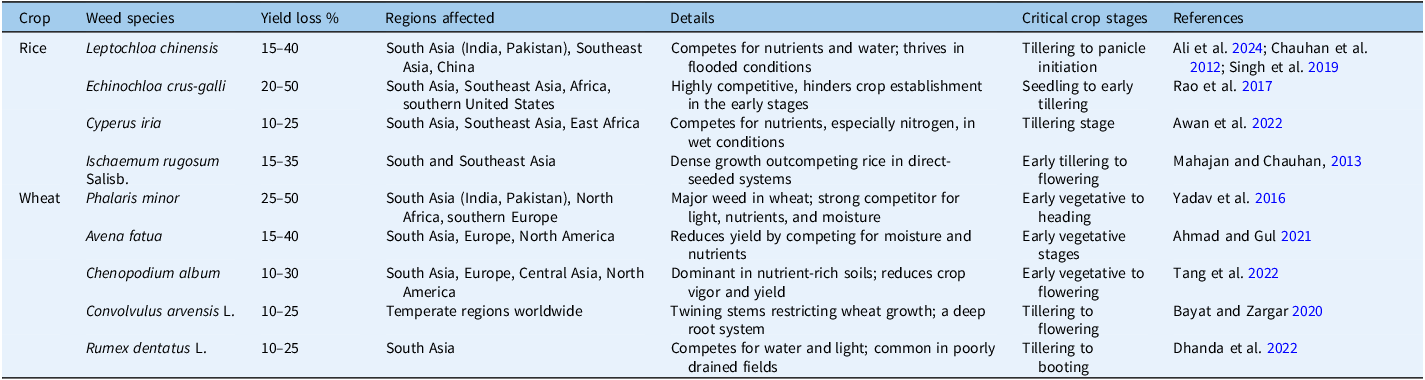

Following the Green Revolution, the rotation of rice and wheat crops became common, along with the introduction of high-yielding semi-dwarf varieties. Weeds were not a significant issue before this revolution due to the natural weed-suppressing abilities of wheat cultivars, mainly against broadleaf weeds (Nawaz et al. Reference Nawaz, Farooq, Nadeem, Siddique and Lal2019). However, the introduction of high-yielding wheat varieties in the early 1970s led to changes in weed composition. Grassy and broadleaf weeds coexisted, but since the 1970s, grassy weeds, particularly P. minor, have dominated the RWCS, which can cause wheat yield losses ranging from 10% to 50%, occasionally leading to crop failures (Kaur et al. Reference Kaur, Kaur, Deol, Sharma, Kaur, Brar and Choudhary2021). Globally, rice is cultivated in various systems, with weed composition varying based on crop management practices. Most of the reported weed species in rice belong to the Poaceae family (Nawaz et al. Reference Nawaz, Farooq, Nadeem, Siddique and Lal2019). Heavy weed infestations are more common in no-tillage direct-seeded aromatic rice systems compared with those with plow tillage. Conventional tillage affects seed burial, potentially preventing deeply buried seeds from emerging. Tillage also disrupts soil conditions, leading weed seeds to move to areas with varying moisture, temperature, light, and predator exposure, influencing weed seedbank behavior (Singh et al. Reference Singh, Bhullar and Chauhan2015). Thus, the RWCS weed landscape has changed since the 1960s; diverse weeds dominate (Table 1), leading to yield losses, posing challenges to crop productivity, and demanding prompt action (Nawaz et al. Reference Nawaz, Farooq, Nadeem, Siddique and Lal2019).

Table 1. Major weed species causing yield losses in the rice–wheat cropping system (RWCS) across different regions.

Irrigation Water Losses

Percolation and deep drainage cause significant irrigation water loss in rice and rice–wheat systems, especially on soils with coarse textures. In addition to decreasing water-use efficiency, these losses lead to fluctuating soil moisture conditions that favor advantageous and drought-tolerant weeds such as rice flatsedge (Cyperus iria L.) and junglerice [Echinochloa colona (L.) Link] (Chauhan and Johnson Reference Chauhan and Johnson2010; Rao et al. Reference Rao, Wani, Ahmed, Haider, Marambe, Rao and Matsumoto2017). Consequently, it is essential to comprehend soil water balance to maximize irrigation and predict weed emergence patterns under varying moisture conditions. Approximately 40% of water input was lost as deep drainage under conventionally tilled wheat, compared with 30% under zero-tillage wheat (Bhatt at al. Reference Bhatt, Singh, Hossain and Timsina2021), according to Bhatt and Kukal (Reference Bhatt and Kukal2017), who found that tillage had an impact on water distribution but observed little effect on the total amount of water applied. Conservation tillage improves water retention by changing the behavior of weed seedbanks and soil surface conditions, which frequently increases seed persistence and changes species composition (Gopal et al. Reference Gopal, Jat, Malik, Kumar, Alam, Jat, Mazid, Saharawat, McDonald and Gupta2020; Mahajan and Chauhan Reference Mahajan and Chauhan2022; Singh et al. Reference Singh, Bhullar and Chauhan2015).

Development of Soil Hardpan

In rice–wheat systems, wet tillage is commonly used to manage soil clods and improve puddling for rice (Bhatt et al. Reference Bhatt, Kukal, Busari, Arora and Yada2016). Still, repeated puddling leads to the formation of a compact hardpan below 7- to 10-cm depth, which restricts root growth in the following wheat crop (Singh et al. Reference Singh, Singh and Sodhi2019). While intensive wet tillage can reduce percolation losses and water demand, it also alters soil structure in ways that influence weed dynamics. The compacted layer tends to retain weed seeds near the surface, increasing their germination chances under moist conditions (Mahajan and Chauhan Reference Mahajan and Chauhan2022). Soil compaction and limited aeration also weaken crop competitiveness, creating favorable conditions for shallow-rooted and anaerobic weeds such as variable flatsedge (Cyperus difformis L.) and barnyard grass [Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) P. Beauv.] (Chauhan et al., Reference Chauhan, Ahmed, Awan, Jabran and Manalil2015; Rao et al. Reference Rao, Wani, Ahmed, Haider, Marambe, Rao and Matsumoto2017). Hence, while puddling benefits rice establishment, it can indirectly improve weed persistence and complicate management in subsequent wheat crops (Bhatt et al. Reference Bhatt, Singh, Hossain and Timsina2021).

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Wet tillage in rice systems compacts the soil, creating anaerobic conditions that increase methane (CH4) emissions through organic matter decomposition (Saini and Bhatt Reference Saini and Bhatt2020). Flooded rice contributes nearly 20% of global CH4, which has a much higher warming potential than CO2 (Bhatt et al. Reference Bhatt, Singh, Hossain and Timsina2021). While continuous flooding promotes the release of CH4, direct-seeded rice (DSR) produces less CH4 but slightly more nitrous oxide (N2O) due to periodic aeration (Shindell et al. Reference Shindell, Faluvegi, Koch, Schmidt, Unger and Bauer2009). These shifts in soil aeration and redox potential also affect weed ecology. Flooded soils favor anaerobic weeds like E. crus-galli and C. difformis, whereas DSR systems encourage drought-tolerant species such as E. colona (Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan, Ahmed, Awan, Jabran and Manalil2015; Mahajan and Chauhan Reference Mahajan and Chauhan2022). Thus, greenhouse gas mitigation practices like alternate wetting and drying can influence both emissions and weed population dynamics in rice–wheat systems (Ullah et al. Reference Ullah, Nawaz, Farooq and Siddique2021).

The Challenge of Soil Nutrient Loss

Monocropping in rice–wheat systems undermines soil health by causing nutrient imbalances and reduced productivity. Continuous cultivation drains key macronutrients, N, P, and K, with each ton of rice and wheat removing about 20 to 25 kg N, 4 to 5 kg P, and 25 to 27 kg K from the soil (Bora Reference Bora2022). Residue burning worsens potassium loss, while widespread deficiencies of Zn (49%), B (33%), Fe (12%), and Mn (5%) further reduce soil fertility. In the Indo-Gangetic Plains, uniform fertilizer use often causes nutrient inefficiency and yield losses due to soil variability (Sapkota et al. Reference Sapkota, Singh, Yadav, Khatri-Chhetri, Jat, Sharma, Jat and Stirling2020). Moreover, nutrient depletion is worsened by weed competition, as weeds extract significant portions of N, P, and K from the root zone, further limiting nutrient availability for crops (Abbas et al. Reference Abbas, Iqbal, Iqbal, Ali, Ahmed, Ijaz, Hadifa and Bethune2021; Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Rana, Rana and Sharma2016).

The Growing Challenge of Time Management

Late-maturing rice varieties often delay harvest and postpone wheat sowing, creating a narrow turnaround between crops. Managing rice residues and restoring soil moisture further prolongs planting time, especially under delayed rainfall (Nawaz et al. Reference Nawaz, Farooq, Nadeem, Siddique and Lal2019). Late sowing, after mid-November, decreases wheat yield by about 1% to 1.5% d−1 due to rising temperatures during anthesis and grain filling (Helal et al. Reference Helal, Khattab, Emam, Niedbała, Wojciechowski, Hammami, Alabdallah, Darwish, El-Mogy and Hassan2022). Excessive heat (>30 C) causes pollen sterility and floret abortion, reducing grain weight (Afzal et al. Reference Afzal, Akram, Rehman, Rashid and Basra2019). Such delays not only lower wheat yield but also favor early-germinating winter weeds, intensifying competition at later stages (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Wu, Ma, Chen and Xin2015).

Diminished Land and Water Productivity

Meeting rising global food demand involves a 2.5% annual increase in cereal output, yet land competition from urbanization and industrial growth has stagnated yields in the rice–wheat system (Yamini et al. Reference Yamini, Singh, Antar and El Sabagh2025). Excessive groundwater extraction, about 1.2 million hectare-meters beyond recharge, has led to a continuous water table decline (Khan et al. Reference Khan, Timsina, Humphreys and Singh2023). Intensive puddling and flooding further degrade soil structure, reduce water productivity, and delay timely wheat establishment, indirectly influencing weed flushes. Shifting toward water-saving practices such as direct-seeded rice or mechanical transplanting can improve both water-use efficiency and crop–weed management (Nawaz et al. Reference Nawaz, Farooq, Nadeem, Siddique and Lal2019).

Hidden Dynamics of Soil Seedbanks

Certain studies have suggested that soil seedbanks play a significant role in individual invasiveness, as the establishment of a seedbank is a strategy that would sustain a species in invaded areas (Gioria et al. Reference Gioria, Pysek and Osborne2018). As germination or reproduction chances are poor, enduring soil seedbanks allow organisms to survive within soil (Pysek et al. Reference Pysek, Manceur, Alba, McGregor, Pergl, Stajerova, Chytry, Danihelka, Kartesz, Klimesova and Lucanova2015). Furthermore, seedbanks preserve population genetic variation, enhancing alien invaders’ capacity to adapt to unexpected site circumstances experienced in their imported area by distributing environmental hazards across time (Leary et al. Reference Leary, Mahnken, Wada and Burnett2018). Because a few viable seeds in the soil could allow reinvasion, the role of seedbanks in species’ resilience must be considered in weeds elimination. Compared with their native genera or non-invasive species, successful invading species frequently have bigger and longer-lasting seedbanks (Skalova et al. Reference Skalova, Moravcova, Cuda and Pysek2019).

Weed Dynamics in RWCS

Weeds in wheat-based systems decrease productivity, hindering sustainable agriculture and causing significant yield losses (Table 1). Agronomic practices promoting favorable crop environments inadvertently foster weed proliferation. Continuous cultivation of the same crop leads to well-adapted weeds, challenging existing management practices, such as in the rice–wheat system, which favors grassy weeds over broadleaved ones. Management difficulties arise from issues like herbicide resistance, labor costs, and environmental pollution (Shahzad et al. Reference Shahzad, Farooq and Hussain2016).

Phalaris minor

Phalaris minor, an annual weed originating from the Mediterranean region, is now prevalent in more than 60 countries across every continent except Antarctica. This invasive weed, particularly problematic for winter crops like wheat, demands a closer look at how cropping systems impact its occurrence and damage. A density of 60 to 70 P. minor plants m−2 in a wheat field can result in a yield reduction of around 10%. In cases of severe infestation, where the population reaches 500 plants m−2, yield losses can escalate to as much as 50% (Kaur et al. Reference Kaur, Kaur, Deol, Sharma, Kaur, Brar and Choudhary2021).

Understanding the spatiotemporal population dynamics of P. minor in diverse cropping systems is crucial for effective control strategies (Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan, Singh and Mahajan2012; Om et al. Reference Om, Kumar and Dhiman2005). Given its annual herbaceous nature, P. minor’s seed and seedling characteristics, including dormancy, germination, and reproduction, are key factors in its establishment. Research on the bioecological aspects of seed dormancy, germination, and reproductive responses to various cropping systems is essential for future ecological control (Singh et al. Reference Singh, Singh and Raghubanshi2013). Previous findings indicate that P. minor seeds undergo true dormancy for 3 to 6 mo after dispersal, influenced by environmental factors such as exposure to light. However, further research is required to understand how different crops and cropping systems affect the occurrence, spread, and impact of this weed species (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Shen, Zhang, Clements, Yang, Li, Dong, Zhang, Jin and Gao2019).

Leptochloa chinensis

Chinese sprangletop [Leptochloa chinensis (L.) Nees], a C4 grass native to tropical Asia, has become a pervasive weed in direct-seeded rice fields due to its ability to thrive under both flooded and water-limited conditions. Despite its annual nature, it can persist as a perennial under favorable conditions, leading to invasiveness attributed to high seed production (Rao et al. Reference Rao, Wani, Ahmed, Haider, Marambe, Rao and Matsumoto2017). This weed is prevalent in direct-seeded rice in numerous countries, with its expansion linked to the adoption of direct-seeded systems and herbicide use, as observed in Malaysia and Sri Lanka. In water-limited fields, the weed’s competition for water can induce stress in crops, posing challenges to rice cultivation (Chauhan and Abugho 2013; Chauhan and Bhushan, Reference Chauhan and Bhushan2022). The habitat preferences and strong competitive nature of these species classify them as global rice crop weed. Despite it’s significance, limited information exists on its germination ecology, temperature and light preferences, and mechanisms for tolerating hypoxic, flooded conditions. Understanding its germination and emergence dynamics is crucial for comprehending the interactions between this weed and crops in aquatic environments (Kathiresan and Gualbert Reference Kathiresan and Gualbert2016).

Ecological Factors Influencing Weed Species Composition

The germination of seeds is influenced by diverse environmental factors, with temperature being the foremost among these, particularly in irrigated field settings (Kapiluto et al. Reference Kapiluto, Eizenberg and Lati2022). Weeds that emerge either early or late in the growth cycle generate substantial quantities of viable seeds, capable of persisting in soil profiles for extended periods. This persistence significantly contributes to the continued existence and triumph of weeds. Consequently, in most arable crop systems, the primary emphasis in weed management strategies is placed on diminishing weed density during the initial stages of crop growth (Khan et al. Reference Khan, Mobli, Werth and Chauhan2022). Nonetheless, limiting weed management to a specific time frame heightens the susceptibility to suboptimal weed control, primarily because of unfavorable weather conditions (Travlos et al. Reference Travlos, Gazoulis, Kanatas, Tsekoura, Zannopoulos and Papastylianou2020).

Temperature and Water Potential Predictors for Weed Seed Emergence

Weed seed longevity in soil profiles results from dormancy, preventing germination even in optimal conditions. Dormancy is categorized into primary and secondary types, with secondary dormancy succeeding the end of primary dormancy in a process known as dormancy cycling (Baskin and Baskin Reference Baskin and Baskin1998). Adapted weed species exit dormancy before the season favorable for seedling growth and enter dormancy before unfavorable environmental conditions (Benech-Arnold et al. Reference Benech-Arnold, Sanchez, Forcella, Kruk and Ghersa2000). Seeds of summer annual species typically require exposure to low winter temperatures to break dormancy, but germination occurs when temperatures rise in spring. In contrast, winter annual seeds emerge from dormancy with high summer temperatures and may enter secondary dormancy in response to low winter temperatures (Forcella et al. Reference Forcella, Benech-Arnold, Sanchez and Ghersa2000). Weed emergence timing relies on seed germination, influenced by soil temperature and moisture potential. Among various environmental factors affecting seed behavior, soil temperature primarily influences dormancy and germination capacity, impacting both dormancy regulation and the speed of germination in nondormant seeds (Ali et al. Reference Ali, Afzal, Khaliq and Naveed2024).

Germination rates vary with temperature, increasing up to the optimum range and declining beyond it (Bradford Reference Bradford2002). Upon dormancy loss, seed germination rate exhibits a positive linear correlation with the range from base to optimum temperature and a negative linear correlation from optimum to ceiling temperature (Travlos et al. Reference Travlos, Gazoulis, Kanatas, Tsekoura, Zannopoulos and Papastylianou2020). Fluctuating temperatures, especially diurnal soil temperature variations, can play a crucial role in reducing seed dormancy for various weed species, particularly when dormancy levels are low (Benech-Arnold et al. Reference Benech-Arnold, Sanchez, Forcella, Kruk and Ghersa2000).

Soil temperature serves as a predictor in crop growth models for seedling emergence. It can also be applied to predict weed emergence if emergence follows a simple, continuous, cumulative sigmoidal curve and the upper soil layers stay consistently moist. Moreover, when the requirement for fluctuating temperatures to break seed dormancy in this species is unmet, there is a diminished responsiveness to such temperature variations among the population (Marschner et al. Reference Marschner, Colucci, Stup, Westbrook, Brunharo, DiTommaso and Mesgaran2024). The diversity among weed species in their specific demands for fluctuating temperatures during seed germination underscores the necessity for additional research on the influence of temperature fluctuations on the germination of harmful weed species across diverse global regions, considering various soil and climatic conditions (Bradford and Pedro Reference Bradford, Pedro, Buitink and Leprince2022; Travlos et al. Reference Travlos, Gazoulis, Kanatas, Tsekoura, Zannopoulos and Papastylianou2020).

Potential Impacts of Light on Weed Germination

Seed responsiveness to light signals relies on phytochromes, a group of proteins functioning as sensors for light changes. Phytochrome mediates dormancy cancellation, with two photo-convertible forms: active Pfr (peak absorption at 730 nm) and Pr (peak absorption at 660 nm). The transition from Pr to Pfr, induced by red light (R), is a recognized part of germination induction in various plant species (Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Wang and Deng2011). Germination induction occurs at Pfr/Pr ratios as low as 10−4, typically saturating at <0.03 Pfr/Pr. Light quality may surpass quantity in significance for seeds, with evidence indicating that far-red light (∼735 nm) can hinder germination. In terms of weed emergence influenced by light, the increase in far-red light or the far-red to red light ratio (∼645 nm) as plant canopies develop and solar elevation decreases post-summer suggests inhibition of sensitive species’ emergence (Benech-Arnold et al. Reference Benech-Arnold, Sanchez, Forcella, Kruk and Ghersa2000). However, the practical implications of far-red exposure for emergence under field conditions remain unclear. In certain situations, light seems to serve as a signal for breaking dormancy when deeply buried seeds are relocated to shallower soil depths. Conversely, exposure of seeds to light may hinder germination in diverse ways, contingent upon the species and conditions. Investigating the light requirements for seed germination is crucial for emergence modeling, representing a substantial and unexplored research area (Travlos et al. Reference Travlos, Gazoulis, Kanatas, Tsekoura, Zannopoulos and Papastylianou2020).

Traditional Weed Management Approaches

Traditional weed management in RWCS combines preventive, cultural, mechanical, and natural strategies to maintain weed control and crop productivity (Figure 1). Preventive methods such as stale seedbed preparation, deep plowing, and seed sanitation are considered the most sustainable, as they help eliminate early-emerging weeds and minimize new infestations (Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan, Matloob, Mahajan, Aslam, Florentine and Jha2017; Khan et al. Reference Khan, Ahmad, Raza and Hasanuzzaman2019). Cultural practices, including the use of vigorous cultivars, optimal row spacing, higher seed rates, crop rotation, and balanced nutrient and water management, strengthen crop competitiveness and reduce dependence on herbicides (Khan et al. Reference Khan, Ahmad, Raza and Hasanuzzaman2019; Mahajan and Chauhan Reference Mahajan and Chauhan2013). Additional techniques, such as dense planting and integrating ducks or fish into paddy fields, further suppress weed growth while lowering chemical inputs (Sayed et al. Reference Sayed, Syakir, Othman, Azhar, Tohiran and Nobilly2025).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of traditional weed management strategies in the rice–wheat cropping system (RWCS).

Mechanical controls, such as straw mulching, puddling, and hand weeding, provide reliable, nonchemical options but are often limited by high labor costs and potential soil disturbance when applied improperly (Beckie and Gill Reference Beckie, Gill, Singh, Batish and Kohli2006; Khan et al. Reference Khan, Ahmad, Raza and Hasanuzzaman2019). Natural herbicides derived from plants, such as neem extracts, offer safer environmental alternatives but generally act more slowly and require frequent applications to achieve consistent results (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Chen, Zhang, Wang, Ma, Liu, Niu, Yang, Xu and Zhang2023; Ofosu et al. Reference Ofosu, Agyemang, Marton, Pasztor, Taller and Kazinczi2023; Ologundudu Reference Ologundudu2019). Despite these advantages, conventional practices continue to face challenges, including herbicide resistance, labor shortages, and soil erosion (Gage et al. Reference Gage, Krausz and Walters2019; Kraehmer et al. Reference Kraehmer, Laber, Rosinger and Schulz2014; Sardana et al. Reference Sardana, Mahajan, Jabran and Chauhan2017).

A critical evaluation shows that the performance and adoption of these methods vary considerably across the rice–wheat belt. Stale seedbeds can reduce P. minor emergence by up to 50%, but timely irrigation and machinery availability often limit their widespread use. Crop rotations with Maize (Zea mays L.) or legumes are effective in depleting weed seedbanks, yet economic and market factors discourage many farmers from shifting away from continuous wheat. IWM, combining delayed sowing, competitive cultivars, and preemergence herbicides, has shown the most consistent success against weeds with complex dormancy, although its adoption depends on awareness, training, and cost considerations (Perotti et al. Reference Perotti, Larran, Palmieri, Martinatto and Permingeat2020). Overall, the transition toward locally adapted, cost-effective, and knowledge-driven IWM strategies remains key to achieving long-term weed suppression and sustainability in the RWCS.

Eco-evolutionary Approaches to Weed Management

Eco-evolutionary weed management uses ecological and evolutionary insights to develop sustainable strategies and enhance long-term agricultural resilience (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Exploring the ecological benefits of population-based threshold models for weed management in the rice–wheat cropping system (RWCS).

Improving Crop Competitiveness through Enhanced Traits

Enhancing crop competitiveness is vital for sustainable weed management in the RWCS. Earlier studies mainly focused on identifying high-yielding cultivars under weed pressure, noting that late-maturing types often performed better, although the reasons were unclear (Choe et al. Reference Choe, Drnevich and Williams2016). Recent work highlights that competitiveness depends not only on growth duration but also on molecular, physiological, and morphological traits that help crops detect and respond to neighboring weeds (Ballare and Pierik Reference Ballare and Pierik2017). For instance, even in the absence of direct resource competition, weed seedlings can trigger oxidative stress in corn and soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] through H2O2 accumulation, revealing early recognition of competition (McKenzie-Gopsill et al. Reference McKenzie-Gopsill, Lee, Lukens and Swanton2016).

Seed treatments offer an additional way to improve crop performance under weedy conditions. Beyond protection, certain compounds act as “gene triggers,” activating defense pathways that enhance stress tolerance. Thiamethoxam, for example, improves germination, root growth, and enzyme activity while reducing oxidative damage (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Amirsadeghi, McKenzie-Gopsill, Afifi, Bozzo, Lee, Lukens and Swanton2016; Westwood et al. Reference Westwood, Charudattan, Duke, Fennimore, Marrone, Slaughter, Swanton and Zollinger2018). Integrating these physiological insights into breeding programs could greatly improve the competitiveness of rice and wheat against weeds like P. minor. Recent studies have shown that incorporating early shoot-vigor traits in wheat enhances root growth and field competitiveness (Hendriks et al. Reference Hendriks, Gurusinghe, Weston, Ryan, Delhaize, Weston and Rebetzke2024), while seed vigor–related QTLs in direct-seeded rice strengthen weed suppression (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Fei, Wang, Zhao, Hou, Cao, Wu and Wu2023).

Innovative Biological Strategies

In picturing weed control strategies, it is essential to consider biological control, which involves deploying natural enemies such as phytophagous arthropods, plant pathogens, fish, birds, and other animals to suppress weeds (Harding and Raizada Reference Harding and Raizada2015; Sayed et al. Reference Sayed, Syakir, Othman, Azhar, Tohiran and Nobilly2025). Classical biological control involves introducing non-native agents to manage exotic invasive weeds, whereas augmentation biocontrol entails boosting the population of indigenous agents for weed suppression (Gage and Schwartz-Lazaro Reference Gage and Schwartz-Lazaro2019). The term “bioherbicides” refers both to enhancing natural weed pathogens for control and to three biologically based types: biochemical herbicides, microbial formulations, and GM plants producing herbicidal compounds (Comont et al. Reference Comont, Hicks, Crook, Hull, Cocciantelli, Hadfield, Childs, Freckleton and Neve2019).

These biocontrol methods are expected to play a crucial role in weed management by 2050 due to their cost-effectiveness, long-term benefits, sustainability, effectiveness, and environmental friendliness (Westwood et al. Reference Westwood, Charudattan, Duke, Fennimore, Marrone, Slaughter, Swanton and Zollinger2018). While proven effective in undisturbed areas, such as natural spaces and forests, biological weed control faces challenges in disturbed agricultural lands due to inconsistent performance, uncontrollable interactions, and user acceptance issues (Neve Reference Neve2018). Exciting possibilities lie in using omics methods to discover genes and gene products involved in herbicidal effects, with newer molecular genetic approaches like RNAi and CRISPR/Cas9 promising advancements in weed control, provided they are recognized and regulated as biologically based controls (Comont et al. Reference Comont, Hicks, Crook, Hull, Cocciantelli, Hadfield, Childs, Freckleton and Neve2019).

Weed Seedbank Depletion

The soil seedbank is the main source of annual weed outbreaks in the RWCS (Nandan et al. Reference Nandan, Singh, Kumar, Singh, Hazra, Nath, Malik and Poonia2020). Because many dominant grasses, including P. minor, exhibit complex dormancy, management strategies must be evaluated for their actual impact on seedbank depletion rather than simply described. Conservation agriculture practices such as zero-tillage wheat and direct-seeded or unpuddled rice have shifted weed emergence patterns and increased monocot dominance (Nath et al. Reference Nath, Das, Rana, Bhattacharyya, Pathak, Paul, Meena and Singh2017). Their effectiveness remains highly dependent on initial seedbank levels, soil conditions, and species ecology; assessing viable seed density is essential for guiding management decisions (Lal et al. Reference Lal, Gautam, Raja, Tripathi, Shahid, Mohanty, Panda, Bhattacharyya and Nayak2016). Long-term weed suppression requires approaches that consistently exhaust the seedbank (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Li, Zhao and Qiang2021). Ecological and integrated strategies offer promise but remain underutilized in South Asia (MacLaren et al. Reference MacLaren, Storkey, Menegat, Metcalfe and Dehnen-Schmutz2020). Among them, the false seedbed technique can reduce seedbanks by inducing early germination, yet its performance varies with moisture, temperature, and soil disturbance (Travlos et al. Reference Travlos, Gazoulis, Kanatas, Tsekoura, Zannopoulos and Papastylianou2020). Overall, effective RWCS management relies on identifying which tactics reliably reduce dominant grass seedbanks and understanding the conditions under which they work best.

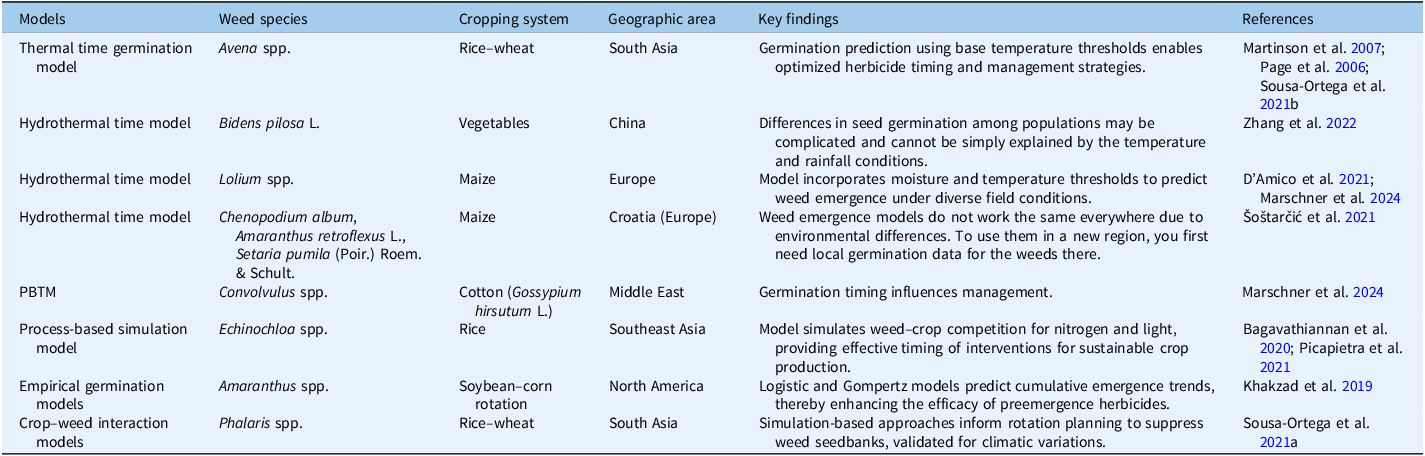

Population-based Threshold Models

Climate change is reshaping weed communities in the RWCS, with wetter conditions encouraging water clover (Marsilea spp.) in rice fields, while water scarcity and the shift toward direct-seeded rice promote grasses such as crowfoot grass [Dactyloctenium aegyptium (L.) Willd.], L. chinensis, and weedy rice (Oryza sativa L.). Rising temperatures further alter species composition, increasing parasitic weeds like witchweed (Striga spp.) and broomrape (Orobanche spp.) in corn, sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench], and rice (Jinger et al. Reference Jinger, Kaur, Kaur, Rajanna, Kumari and Dass2017). Elevated CO2 may also intensify P. minor infestations in wheat and accelerate weedy rice spread across the Indo-Gangetic Plains. Because invasion success is often linked to rapid germination and high seed production, accurately predicting emergence under changing temperature and moisture conditions is essential for effective ecological management (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Benech-Arnold, Batlla, Bradford, Bradford and Nonogaki2007; Boddy et al. Reference Boddy, Bradford and Fischer2012; Rodriguez et al. Reference Rodriguez, Kruk and Satorre2020). Population-based threshold models (PBTMs), which quantify germination responses to temperature, water potential, and oxygen (Bradford Reference Bradford2002; Finch-Savage et al. Reference Finch-Savage, Rowse and Dent2005), provide a practical tool for anticipating weed recruitment. Their value becomes clearer when applied to actual field conditions (Boddy et al. Reference Boddy, Bradford and Fischer2012). For example, integrating local temperature and soil moisture data to simulate the emergence of A. fatua can help farmers anticipate peak flushes and time early interventions more effectively (Martinson et al. Reference Martinson, Durgan, Forcella, Wiersma, Spokas and Archer2007; Table 2).

Table 2. Overview of population-based threshold models (PBTMs) for weed management across cropping systems and regions.

Thermal Time Model

Population-based models for seed germination time courses, as per Bradford (Reference Bradford, Kigel and Galili1995), rely on the threshold concept. A threshold signifies the minimum level of a specific factor necessary for a seed to initiate germination. For instance, in thermal time models, there is a base temperature (T b) below which germination will not occur. Above T b, germination becomes possible, with the rate increasing linearly with temperature. Thermal time (θ T ) in seed germination, measured in degree-days (C d) or degree-hours (C h), results from the product of temperature and accumulated time. In controlled seed germination tests, maintaining a specific temperature (T) for a set time allows calculation of thermal time (θ T(g)). In the field, daily temperature variations lead to the accumulation of thermal time for each day (i), with germination occurring upon reaching the total thermal time requirement (Watt and Bloomberg Reference Watt and Bloomberg2012). However, beyond an optimum temperature (T o), germination slows, eventually stopping or being impeded at a maximum temperature (T c). These are known as cardinal temperatures for seed germination, providing insights into seed performance under varying temperatures. Notably, seeds with the highest germination rates at suboptimal temperatures tend to be the most vigorous and stress tolerant (Bradford and Pedro Reference Bradford, Pedro, Buitink and Leprince2022).

Hydro-Time Model

Soil moisture plays a crucial role in influencing the seed dormancy of various species. Initially, the ecological conditions during seed development in maternal plants and seed maturation impact seed dormancy levels (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Zhao, Huang, Yang, Wei, He and Walck2018). The influence of water deficits on seed germination is captured by the concept of “hydro-time,” introduced by Gummerson (Reference Gummerson1986) and further elaborated by Bradford (Reference Bradford, Kigel and Galili1995). Bradford’s model incorporates dormancy loss during afterripening, reflecting changes in the base water potential (Ψ b(50)) that allows for 50% germination. Christensen et al. (Reference Christensen, Meyer and Allen1996) confirmed that the Ψ b(50) value decreases due to afterripening, with this updated value becoming the initial value for the next time step. This process repeats until the Ψ b(50) value of fully afterripened seeds is achieved. The model not only addresses dormancy changes concerning the thermal environment but also considers the soil water status. Importantly, the loss of primary dormancy does not guarantee germination for some species if moisture requirements are not met (Otieno et al. Reference Otieno, Ulian, Nzuve and Kimenju2020). The germination response of wild plants to soil water potential is linked to the natural water conditions in their habitats. Models predicting weed germination and emergence must encompass a broad range of water potentials, as different weed species require specific values for germination. While many weed seeds can germinate across various water potentials, emerged seedlings become vulnerable to dehydration, leading to irreversible cellular damage (Bao et al. Reference Bao, Zhang, Wei, Zhang and Liu2022). Therefore, understanding the water requirements for germination in dominant weed species is crucial for agricultural areas, and these needs can be addressed through proper irrigation if not naturally met.

Hydrothermal Time Model

Temperature and water are fundamental and variable factors crucial for seed germination. Gummerson (Reference Gummerson1986) pioneered the integration of thermal and hydro-time models into the hydrothermal time (HTT) model (measured in MPa C h or MPa C d). This model, conceptualized as an extension of the hydro-time model, incorporates the effects of water potential (Ψ) on germination within a thermal time framework. Notably, the HTT model, often analyzed concerning the logarithm of time, effectively describes germination rates and percentages in response to both temperature (T) and water potential (Ψ). With approximately 50 publications using the term “hydrothermal” in their titles and almost 300 total publications addressing various applications, this model has proven to be broadly applicable and accurate, influencing fields such as seed physiology, crop production, weed management, and ecology (Bradford and Pedro Reference Bradford, Pedro, Buitink and Leprince2022). The equations within this model successfully account for the increasing germination rate with rising temperature above the base (T b) and the opposite effect as water potential decreases toward the base water potential (Ψ b ) thresholds of different seed fractions, particularly in suboptimal temperature ranges (Durr et al. Reference Durr, Dickie, Yang and Pritchard2015).

Ecological Benefits of Population-based Threshold Models in Weed Management

In the realm of weed management, understanding the soil seedbank is essential, given its persistence, regulated by processes governing seed dormancy (Schwartz-Lazaro and Copes Reference Schwartz-Lazaro and Copes2019). Population-based threshold models have proven effective in analyzing the permanence and establishment of weed seedbanks about environmental variables, as highlighted by Bradford and Pedro (Reference Bradford, Pedro, Buitink and Leprince2022). This knowledge is particularly valuable in scenarios involving environmental and plant variation. However, it is worth noting that the dormancy processes of wild species are more pronounced than those of cultivated species, playing a significant role in bet-hedging responses, as discussed by Bradford and Pedro (Reference Bradford, Pedro, Buitink and Leprince2022).

Population-based threshold models play a pivotal role in weed management by allowing for targeted control measures precisely when weed populations exceed predetermined thresholds. This precision not only minimizes the use of chemical inputs but also reduces environmental pollution, contributing to the preservation of the overall ecological balance in agroecosystems (Sapkota et al. Reference Sapkota, Stenger, Ostlie and Flores2023). By avoiding unnecessary and excessive weed control, these models play a crucial role in preserving biodiversity. The maintenance of a diverse ecological community supports natural pest control, enhances soil health, and fosters a resilient agricultural ecosystem (Diyaolu and Folarin Reference Diyaolu and Folarin2024). This nuanced understanding underscores the importance of incorporating population-based models into weed management strategies for sustainable agricultural practices (Figure 2).

Key Constraints in Model Use and Implementation

Weed species exhibit diverse life cycles and growth patterns, making it challenging to develop universal threshold models. Tailoring models to specific weed species and local conditions is essential for effective implementation. Continuous monitoring of weed populations is crucial for model accuracy, but it can be resource-intensive (MacLaren et al. Reference MacLaren, Storkey, Menegat, Metcalfe and Dehnen-Schmutz2020). Despite a few short-term bioassay studies, efforts to understand weed biology in the context of climate change are progressing slowly, particularly in the realm of long-term, system-level experiments. This research is sophisticated and prolonged and demands an interdisciplinary approach, making it less appealing to funding agencies and weed scientists alike (Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan, Matloob, Mahajan, Aslam, Florentine and Jha2017). Meanwhile, invasive plant species are multiplying and spreading, posing an increasing threat to both managed and natural ecosystems. In the face of climate change, the invasion by alien plant species stands out as the foremost challenge to ecosystem function and stability (Hellmann et al. Reference Hellmann, Byers, Bierwagen and Dukes2008).

Implementing PBTMs comes with challenges, especially in consistently collecting accurate data across large agricultural areas. Environmental variability, like changing weather, soil conditions, and regional differences, adds complexity and can affect model accuracy. Adapting these models to different ecological contexts requires ongoing refinement and calibration to ensure reliable results.

Future Research Horizons

Effective weed management requires a well-rounded, interdisciplinary approach. In the realm of herbicides, it is vital to understand how resistance, especially to new options like RNAi-based herbicides, evolves. Discovering novel herbicides, particularly those derived from natural sources, demands expertise in weed biology, genetics, and chemistry. Precision agriculture and robotics technologies call for the development of automated weed recognition systems and innovative control techniques, with collaboration between weed scientists and technology experts at the forefront. Unraveling the complexities of weed biology and crop–weed interactions, as well as advancing biological control strategies, involves teamwork with plant pathologists and entomologists. The integration of population-based models enhances a well-rounded approach to weed management for sustainable practices. Population-based threshold models offer valuable ecological benefits in weed management, promoting precision, biodiversity conservation, and resource efficiency. However, addressing challenges related to variable environmental conditions, species-specific dynamics, and data collection is essential for successful and widespread implementation. Furthermore, in education, extension, and economics, there is a need for user-friendly data management systems. Training programs should equip students with a mix of skills in weed science, technology, psychology, and socioeconomics. A holistic understanding of these factors will contribute to the development of robust and adaptable models that align with sustainable weed management practices.

Funding statement

This review did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest concerning this publication.