Introduction

Chinese stellara (Stellera chamaejasme L.) is a toxic perennial herbaceous plant commonly found in grasslands and meadows ranging from southern Russia to southwestern China and the western Himalayas (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Volis and Sun2010, Reference Zhang, Yue and Sun2015). It is a traditional Chinese medicine with various medicinal properties, including antibacterial, insecticidal, dispersing, diuretic, analgesic, and expectorant effects (Selenge et al. Reference Selenge, Vieira, Gendaram, Reis, Tsolmon, Tsendeekhuu, Ferreira and Neves2023; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Gao, Zhang, Zhang, Wang and Sun2016). Beyond its medicinal value, S. chamaejasme has drawn significant attention for its destructive effects on grassland ecosystems (Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Sheng, Cui and Xue2004). The entire plant is toxic, with specific components such as stellaterpenoids A-M demonstrating notable cytotoxic activity (Pan et al. Reference Pan, Su, Liu, Deng, Hu, Wu, Xia, Chen, He, Chen and Wan2021). Livestock accidentally ingesting this plant exhibit severe poisoning symptoms, including vomiting and convulsions, which can ultimately lead to death (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Guan, Song, Fu, Han, Lei, Ren, Guo, He and Wei2018). Consequently, grazing animals selectively avoid consuming S. chamaejasme, intensifying grazing pressure on other forage species (You et al. Reference You, Ma, Guo, Kong, Shi, Wu and Zhao2018). This selective grazing behavior not only accelerates grassland degradation but also disrupts ecological balance. Stellera chamaejasme has a strong reproductive capacity, with robust rhizomes and high soil nutrient conversion efficiency, which significantly suppresses the growth of surrounding plants; it often becomes a dominant species on grasslands (YM Liu et al. Reference Liu, Dong, Long, Zhu, Wang, Ge and Li2022). Particularly in northern regions, S. chamaejasme has become a major invasive threat, infesting millions of hectares across multiple provinces—notably 1.4 million ha in Qinghai and 546,700 ha in Gansu. In Gansu Province alone, this invasion has caused annual losses of 137.5 million kg of forage and economic damages estimated at 15 to 20 million yuan (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Ma, Geng, Feng, Wu, Wang and Zhao2015). The plant’s robust rhizomes and efficient nutrient conversion enable it to dominate degraded grasslands, with density increasing from 1.95 plants m−2 in mildly degraded areas to 7.16 plants m−2 in severely degraded ones (SB Liu et al. Reference Liu, Yin, Alatanqiqige A, Lu, Eridunqimuge E, Meng and Galiwa G2022). The proliferation of S. chamaejasme not only alters plant community structures (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Shi, Chen, Zhang, Yu, Cui and Zhao2018) but also negatively impacts ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration, nutrient cycling, soil and water conservation, and water retention (Ren et al. Reference Ren, Deng, Shang, Hou and Long2013), leading to a gradual decline in the service value and capacity of grassland ecosystems (Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Sun, Du, Wu, Zheng, Zhang, Liu and Wu2014). As S. chamaejasme continues to expand, the dominant species shift from forage grass to S. chamaejasme, making it one of the most serious weed problems on Chinese grasslands (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Zhao, Lu, Wang, Liu, Wang and Huang2020).

Current research on the dispersal mechanisms of S. chamaejasme has identified several key biological traits driving its invasion success. The species exhibits a robust root system capable of penetrating 60 to 100 cm (4-yr-old individuals) into the soil, enabling efficient nutrient and water uptake even in adverse conditions (Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Tang, Jiang, Duan and Chang2019). Its drought-resistant lanceolate leaves (Lee and Suh Reference Lee and Suh2015), caespitose stems with terminal inflorescences facilitating pollination (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Jin, Li, Zhang, Yang and Wang2014), and prolific seed production (200 seeds per mature plant) further enhance its reproductive efficiency (Zhao and Wang Reference Zhao and Wang2011). The hard-shelled nutlet fruit also ensures long-term seed viability despite livestock trampling (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Liu, He and Chen2014). Notably, the plant’s toxicity and allelopathic effects suppress herbivory and inhibit neighboring plant growth (Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Zhong, Xu, Du and Song2017; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang, Ren, Dou, Miao, Liu, Huang and Wang2022), while its secondary metabolites alter soil properties and microbial communities, creating self-favorable microhabitats (An et al. Reference An, Han, Wu, Chen, Yuan, Liu and Wang2016; Y Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Cui, Wang and Cao2021). The aqueous extract of S. chamaejasme contains toxic flavonoids that effectively deter herbivory by grazing animals, while its allelopathic compounds inhibit the normal growth of neighboring plants in grasslands (Li et al. Reference Li, Chu, Li, Ma, Niu and Dan2022; GZ Liu et al., Reference Liu, Liu, Guo, Su, Lan and Liu2022; Yan et al. Reference Yan, Guo, Yang, Liu, Jin, Xu, Cui and Qin2014). This plant species strategically modifies its rhizosphere environment by altering soil physicochemical properties and reducing nutrient cycling in the root zone, thereby creating favorable conditions for its own proliferation (N Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, He, Xia, Lian, Yan, Ding, Zhang and Xu2021; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Li, Xing, Chen, Huang and Gao2020). Furthermore, S. chamaejasme enhances its competitive advantage by increasing the abundance of soilborne pathogenic fungi that suppress surrounding vegetation, while simultaneously being protected from these pathogens through its inherent flavonoid constituents, such as neochamaejasmin B, chamechromone, and isochamaejasmin (Yan et al. Reference Yan, Zeng, Jin and Qin2015). The plant’s ecological dominance is further reinforced by its capacity to increase the diversity and richness of soil microbial communities, ultimately establishing a self-sustaining microenvironment that promotes its vigorous growth (Bao et al. Reference Bao, Song, Wang, Yin and Wang2020; Cui et al. Reference Cui, Pan, Wang, Zheng and Gao2020).

Population structure also plays a critical role on the dispersal mechanisms of S. chamaejasme: seedlings exhibit a maternal distribution pattern near parent plants (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Zhao and Zhuo2014), and spatial distributions shift from clumped to random or uniform with increasing altitude or grassland degradation, reflecting adaptive niche expansion (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Zhao, Shi, Sheng, Ren and He2011). However, some gaps persist in our understanding of the ecological mechanisms underlying these patterns. Some studies have focused on small-scale analyses (0 to 2 m) of population structure and intraspecific interactions (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Li, Zhao, Ren, Nie, Jia, Li and Li2019; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Gao, Wang, Sheng and Shi2010), justified by the species’ limited seed dispersal radius (<0.5 m) and “near-mother” distribution (Bai Reference Bai2024). Yet the aforementioned studies are limited to a single region and overlook the differences in population spatial patterns across different regions (e.g., the variations in spatial patterns and spatial relationships may be shaped by different soil heterogeneity and climate conditions in different grasslands). Furthermore, the ecological functions of age-class interactions from spatial patterns (competition or facilitation between seedlings and mature plants) remain poorly resolved. For instance, while hypotheses suggest competitive suppression of seedlings by mature plants (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Zhao, Shi, Sheng, Ren and He2011), empirical evidence for such a dynamic is lacking.

To address these gaps, this study integrates point pattern analysis to investigate small-scale spatial patterns of S. chamaejasme in different regions (five grasslands from the meadow regions of the Qilian Mountains).. Specifically, we hypothesize: (1) S. chamaejasme exhibits distinct spatial distribution patterns across age classes (whole population, young, subadult, mature) in degraded grasslands, and the spatial distribution of S. chamaejasme is primarily driven by subadult plants. By analyzing spatial point patterns and correlations among age classes, this work aims to elucidate the mechanisms behind its dominance in degraded grasslands, providing critical insights for targeted ecological management and restoration strategies. (2) There are facilitation spatial effects of mature plants on seedling establishment, enabling rapid grassland invasion through age-class independence and localized maternal facilitation. By synthesizing density mapping with correlations among age classes, this work aims to elucidate S. chamaejasme’s expansion dynamics in degraded ecosystems, establishing a predictive framework for modeling invasion trajectories and guiding evidence-based intervention strategies in grassland restoration.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

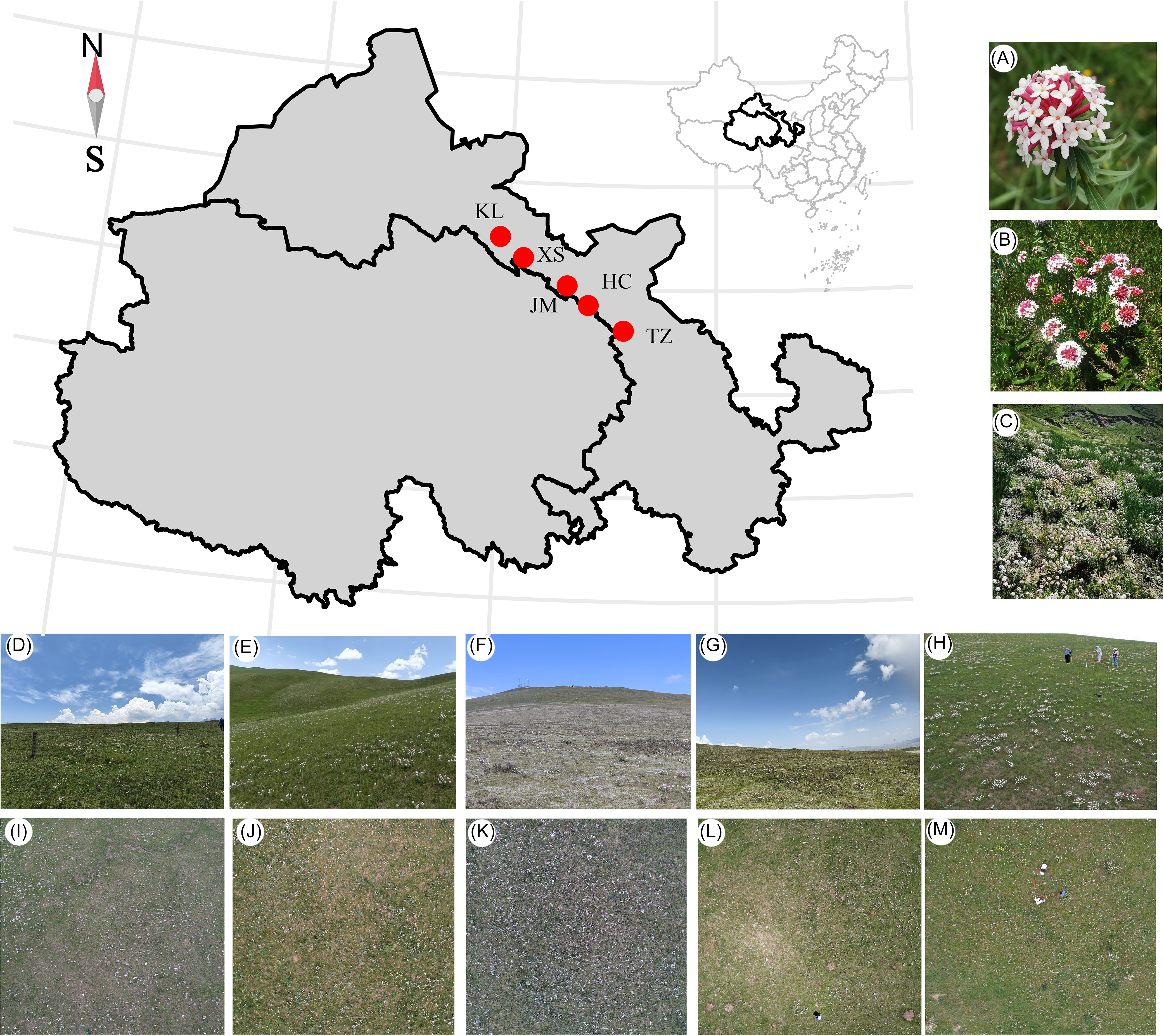

Representative natural alpine grasslands on the eastern side of the Qilian Mountains were selected for the experiment (Figure 1), located in the subalpine and alpine regions of the Qilian Mountain range, which belongs to the cold and humid climate type. This area exhibits distinct continental climate characteristics, with long, cold, and dry winters, and short, cool, and moist summers (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Dong, Li, Zhu and Li2024). Precipitation is concentrated mainly from May to September, and as altitude increases, temperatures gradually decrease while rainfall increases, creating a gradient of temperature and precipitation from the foothills to the deeper mountain areas (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Yu, Liu, Jiang, He, Zhang, Wang, Zhang, Zhao and Zhao2020). Based on the natural distribution patterns and population densities of S. chamaejasme, five sampling areas were established, namely Tian zhu Tibetan Autonomous County (TZ), Huang cheng Grassland (HC), Xi shui Nature Reserve Station (XS), Shan dan Military Horse Farm in Zhangye City (JM), and Kang le Grassland (KL) (Table 1).

Figure 1. Display of sample plot landscape for five sampling areas in the natural alpine grasslands on the eastern side of the Qilian Mountains in China: Tian zhu Tibetan Autonomous County (TZ), Huang cheng Grassland (HC), Xi shui Nature Reserve Station (XS), Shan dan Military Horse Farm in Zhangye City (JM), and Kang le Grassland (KL). (A–C) Stellera chamaejasme inflorescence (A), individual plant (B), and population (C). Habitat images (D–H) and corresponding drone images (I–M) are shown for sample sites HC (D and I), JM (E and J), KL (F and K), TZ (G and L), and XS (H and M).

Table 1. Basic climate details of the five sampling areas in the natural alpine grasslands on the eastern side of the Qilian Mountains in China: Tian zhu Tibetan Autonomous County (TZ), Huang cheng Grassland (HC), Xi shui Nature Reserve Station (XS), Shan dan Military Horse Farm in Zhangye City (JM), and Kang le Grassland (KL).

Data Collection

Five representative grassland plots dominated by S. chamaejasme were systematically selected along an 837-km transect on the eastern Qilian Mountains. Within each S. chamaejasme habitat, standardized 15 m by 15 m sampling quadrats were established. A Cartesian coordinate system was implemented in each quadrat, with the southeastern corner designated as the origin for spatial referencing. This geospatial framework enabled precise mapping of all S. chamaejasme individuals through Cartesian coordinates. Spatial distribution patterns and inter–age class correlations within S. chamaejasme populations were quantitatively analyzed using coordinate-derived positional data. Population density distributions were calculated per unit area, with particular emphasis on comparative analysis of density variations across different developmental stages. These spatial metrics were subsequently employed to elucidate invasion mechanisms underlying S. chamaejasme colonization in degraded grassland ecosystems.

Experimental Methods

According to the classification criteria proposed by Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Zhao, Lu, Wang, Liu, Wang and Huang2020) (Table 2), the S. chamaejasme population was divided into two growth stages: young plants (I and II) and mature plants (III to X). Here, we further subdivided the mature plant category into subadult plants (III and IV) and mature plants (V to X).

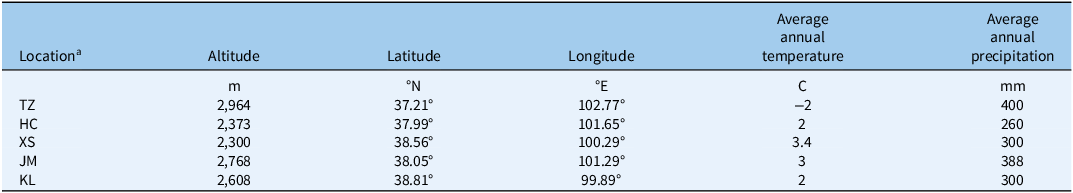

Table 2. Age grading standards for Stellera chamaejasme.

To assess the spatial patterns among the different age classes of young plants, subadult plants, and mature plants, we utilized the univariate pair correlation function g(r) (Stoyan and Stoyan Reference Stoyan and Stoyan1994; Wiegand and Moloney Reference Wiegand and Moloney2004) under a homogeneous Poisson null model. We adopted the homogeneous Poisson process, which assumes complete spatial randomness (CSR), for exploratory analysis across different age classes, demonstrating that the CSR distribution holds at approximately 0 to 3 m, indicating a spatial pattern consistent with randomness.

λ: The density of the point pattern (the number of points per unit area).

r: Spatial scale, referring to the radius of distance considered between points. It can be any value greater than 0.

dk(r)/dr: The derivative of the K-function with respect to the radius r. It represents the rate of change in the deviation of the point pattern from a completely random distribution at the distance scale r.

2πr : This factor is used to convert the derivative of the K function into a probability density function, ensuring that g(r) has the correct dimensionality in space, thus making it a probability density function.

We examined the correlation between different age classes by employing the bivariate g 12(r) function with the application of a random label null model (Aakala et al. Reference Aakala, Kuuluvainen, De Grandpré and Gauthier2007; Marzano et al. Reference Marzano, Lingua and Garbarino2012). For the analysis, we pooled the location data of the various age classes.

λ1 λ2 : The densities of the point patterns marked as 1 and 2, respectively (the number of points per unit area). These densities are used to normalize the values of g 12(r) so that it is not affected by the density of the point patterns.

K 12(r): The cross-type K-function, which describes the number of point pairs between points marked as 1 and points marked as 2 within a distance r.

dk 12(r)/dr: The derivative of K 12(r) with respect to the radius r, reflecting the rate of change in deviation from complete spatial randomness at the distance scale r.

For all analyses, significant departure from the null models was evaluated based on 95% simulation envelopes, which were calculated from the fifth-lowest and fifth-highest values of 99 Monte Carlo simulations. A distribution is classified as clumped, random, or regular for univariate analysis when the value is located above, inside, or below the 95% confidence intervals, respectively. Similarly, for bivariate analysis, two populations are significantly positively correlated (attraction), spatially independent, or significantly negatively correlated (repulsion), when the value is located above, inside, or under the 95% confidence intervals, respectively.

All univariate and bivariate point pattern analyses was conducted using the spatstat package in R. Additionally, contour and density distribution maps were generated by integrating ggplot2, ggmap, and sf packages in R.

Results and Discussion

Age Structure

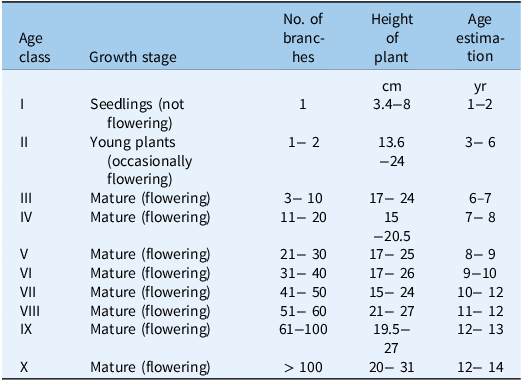

The specific distribution quantities and locations of S. chamaejasme across different age structures are depicted in Figure 2. Within the quadrats, the highest number of S. chamaejasme individuals is found in HC with 2,153 plants (Figure 2 B and G), while the lowest is in TZ, with only 604 plants (Figure 2A and 2F). Overall, the S. chamaejasme population is predominantly composed of subadult plants, with proportions of 68.21%, 75.48%, 70.96%, 62.27%, and 71.60% (Figure 2A–E). In terms of mature plants, the highest number is observed in KL, with 229 plants (Figure 2E and 2J), followed by TZ, with 122 plants (Figure 2A and 2F), and the lowest in JM, with only 12 plants (Figure 2D and 2I). Notably, in TZ, HC, and KL, the distribution of S. chamaejasme is markedly centered around mature plants (Figure 2F, G, and J). This pattern suggests that in these areas, the S. chamaejasme population is dominated by adult individuals, which may have significant implications for the stability and ecological functions of the population.

Figure 2. The quantity and spatial distribution of the three age groups of Stellera chamaejasme across five sampling areas. (A, F) Tianzhu Tibetan Autonomous County (TZ), (B, G) Huangcheng Grassland (HC), (C, H) Xishui Nature Reserve Station (XS), (D, I) Shandan Military Horse Farm in Zhangye City (JM), and (E, J) Kangle Grassland (KL). Y, young; S, subadult; and M, mature plants.

Spatial Pattern

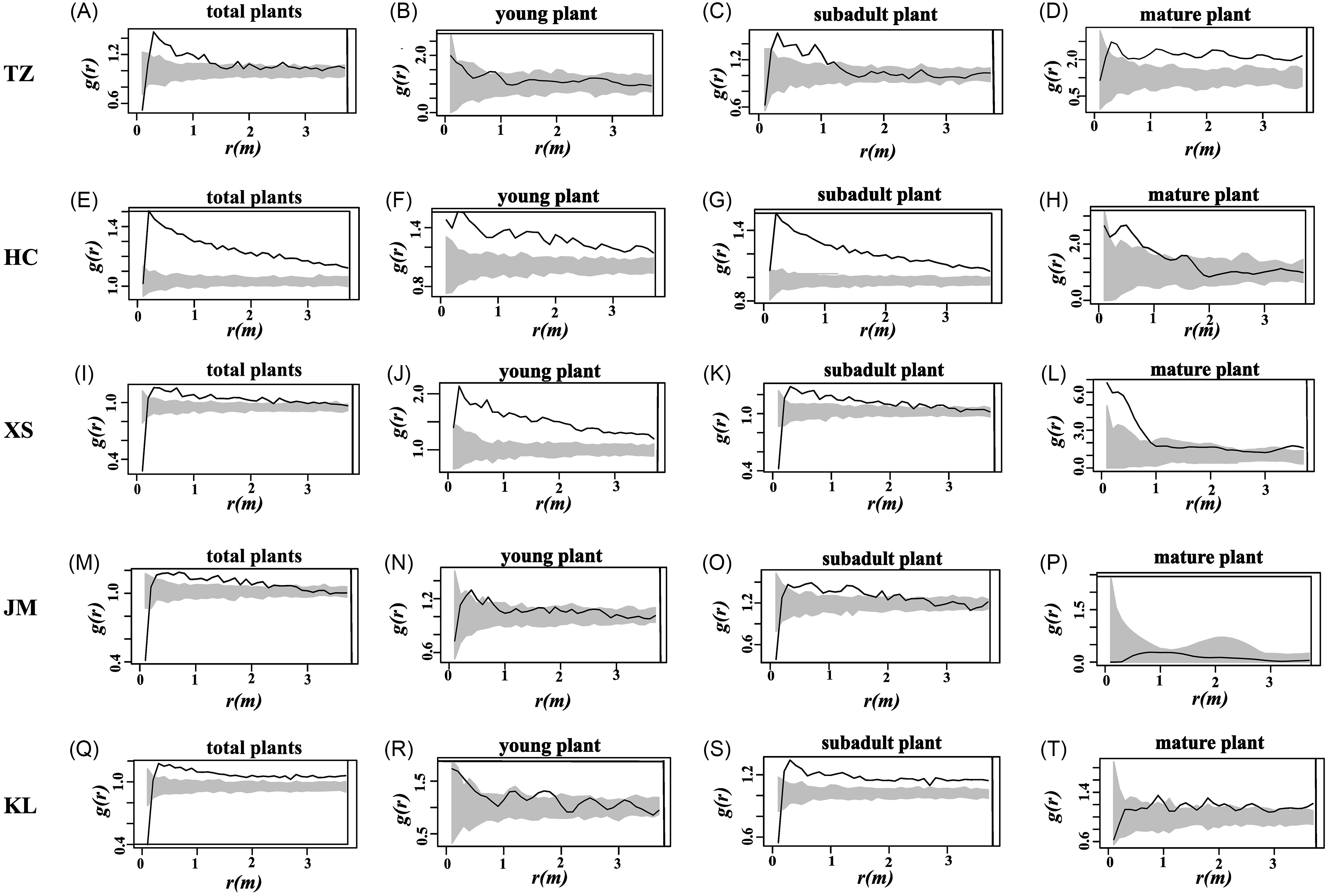

The g(r) univariate function reveals the distribution pattern of S. chamaejasme individuals at specific scales (Figure 3). In the TZ sampling site, the distribution pattern of S. chamaejasme total plants is similar to that of subadult plants, with initial aggregation within 0 to 1 m followed by random distribution beyond 1 m (Figure 3A and 3C). Young plants exhibit a random distribution (Figure 3A), while mature plants show an aggregated distribution (Figure 3D). In the HC sampling site, aside from mature plants, which follow a pattern of initial aggregation within 0 to 1 m followed by random distribution beyond 1 m (Figure 3H), the rest of the plants are aggregated (Figure 3E–G). In the XS sampling site, except for young plants, which are aggregated (Figure 3J), the rest exhibit a pattern of initial aggregation followed by randomness, with the aggregation scale for total and subadult plants being 0 to 3 m (Figure 3I and 3K), and for mature plants, it is 0 to 1 m (Figure 3L). In the JM sampling site, the distribution pattern for total and subadult plants is initial aggregation followed by randomness, with the random distribution primarily occurring beyond 2 m (Figure 3M and 3O), while young and mature plants are generally randomly distributed (Figure 3N and 3P). In the KL sampling site, young and mature plants are generally randomly distributed (Figure 3R and 3T), whereas total and subadult plants are predominantly aggregated (Figure 3Q and S).

Figure 3. Spatial point patterns of Stellera chamaejasme individuals across five study sites in the natural alpine grasslands on the eastern side of the Qilian Mountains in China: Tian zhu Tibetan Autonomous County (TZ), Huang cheng Grassland (HC), Xi shui Nature Reserve Station (XS), Shan dan Military Horse Farm in Zhangye City (JM), and Kang le Grassland (KL). Each row corresponds to a distinct study site. (A–D) TZ, (E–H) HC, (I–L) XS, (M–P) JM, and (Q–T) KL; within each site’s panel, columns (from left to right) depict the spatial distributions of young plants, subadult plants, and mature plants.

At this scale, the overall distribution pattern of S. chamaejasme (Figure 3A, E, I, M, and Q) transitions from clustering to random distribution, with the exception of HC and KL, which remain clustered. The young plants are predominantly clustered, except for JM and KL, which are randomly distributed. The distribution pattern of subadult plants closely mirrors the overall pattern, likely due to the fact that subadult plants typically constitute the majority of the S. chamaejasme population. Mature plants are primarily randomly distributed, with the exception of TZ, which shows a clustering distribution, this may be caused by differences in the number of individuals in the maturity plant.

Spatial Correlation

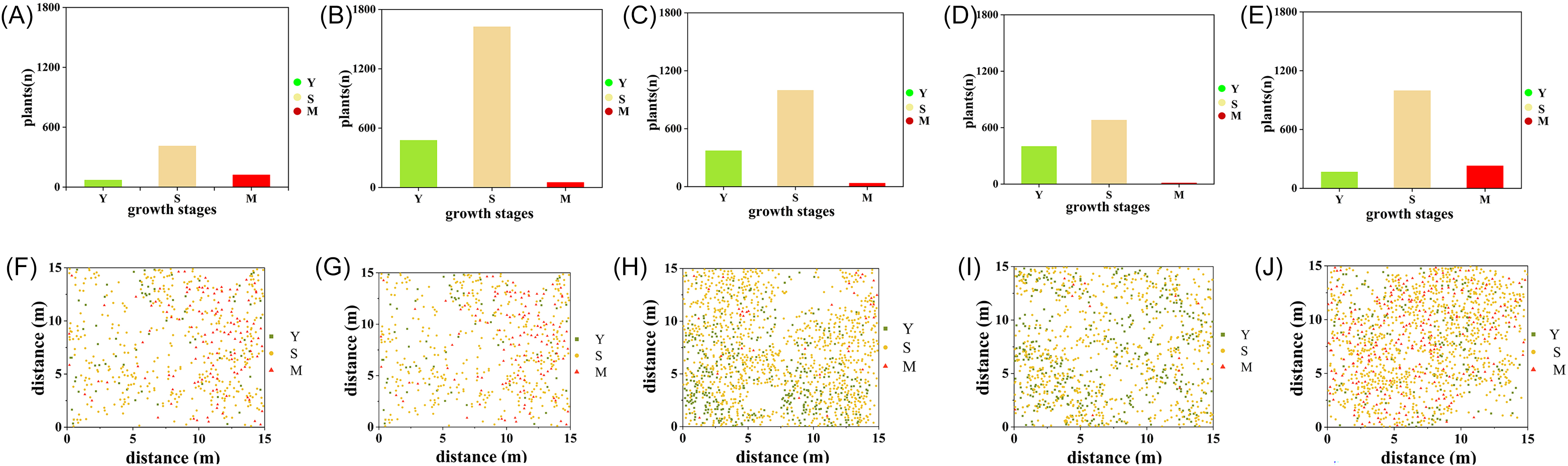

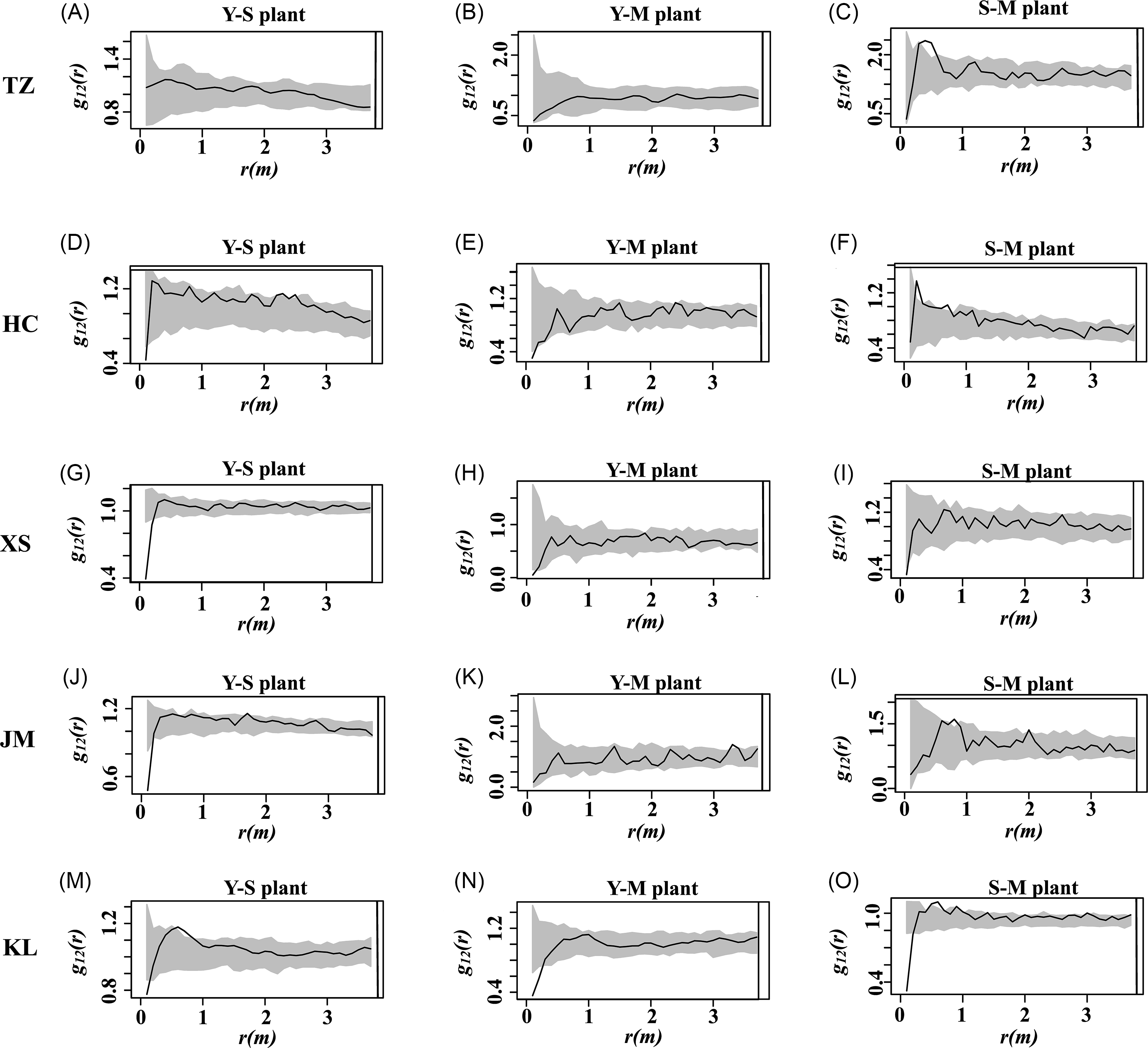

By employing the bivariate function g 12(r), we are able to assess the spatial correlation between different age groups of S. chamaejasme at a specific scale (Figure 4). The analysis reveals that there is no significant correlation between young plants and subadult plants (Y-S), young plants and mature plants (Y-M), or subadult plants and mature plants (S-M) at the 1- to 3-m scale, with no apparent spatial positive or negative correlations observed. This finding indicates that different age groups of S. chamaejasme are spatially independent, meaning the distribution of one age group does not influence the distribution of the others. Such independence suggests limited likelihood of intraspecific competition and mutualistic symbiosis, implying that mature plants are unlikely to significantly inhibit or affect the normal growth of young plants. This spatial independence is beneficial for the adaptability, stability of the population, and the overall health of the ecosystem.

Figure 4. Correlation between different age classes of Stellera chamaejasme individuals across five study sites in the natural alpine grasslands on the eastern side of the Qilian Mountains in China: Tian zhu Tibetan Autonomous County (TZ), Huang cheng Grassland (HC), Xi shui Nature Reserve Station (XS), Shan dan Military Horse Farm in Zhangye City (JM), and Kang le Grassland (KL). Each row corresponds to a distinct study site: (A–C) TZ, (D–F) HC, (G–I) XS, (J–L) JM, and (M–O) KL; within each site’s panel, columns (from left to right) depict the spatial associations among different plant cohorts. Young plants and subadult plants (Y-S), young plants and mature plants (Y-M), and subadult plants and mature plants (S-M).

Density

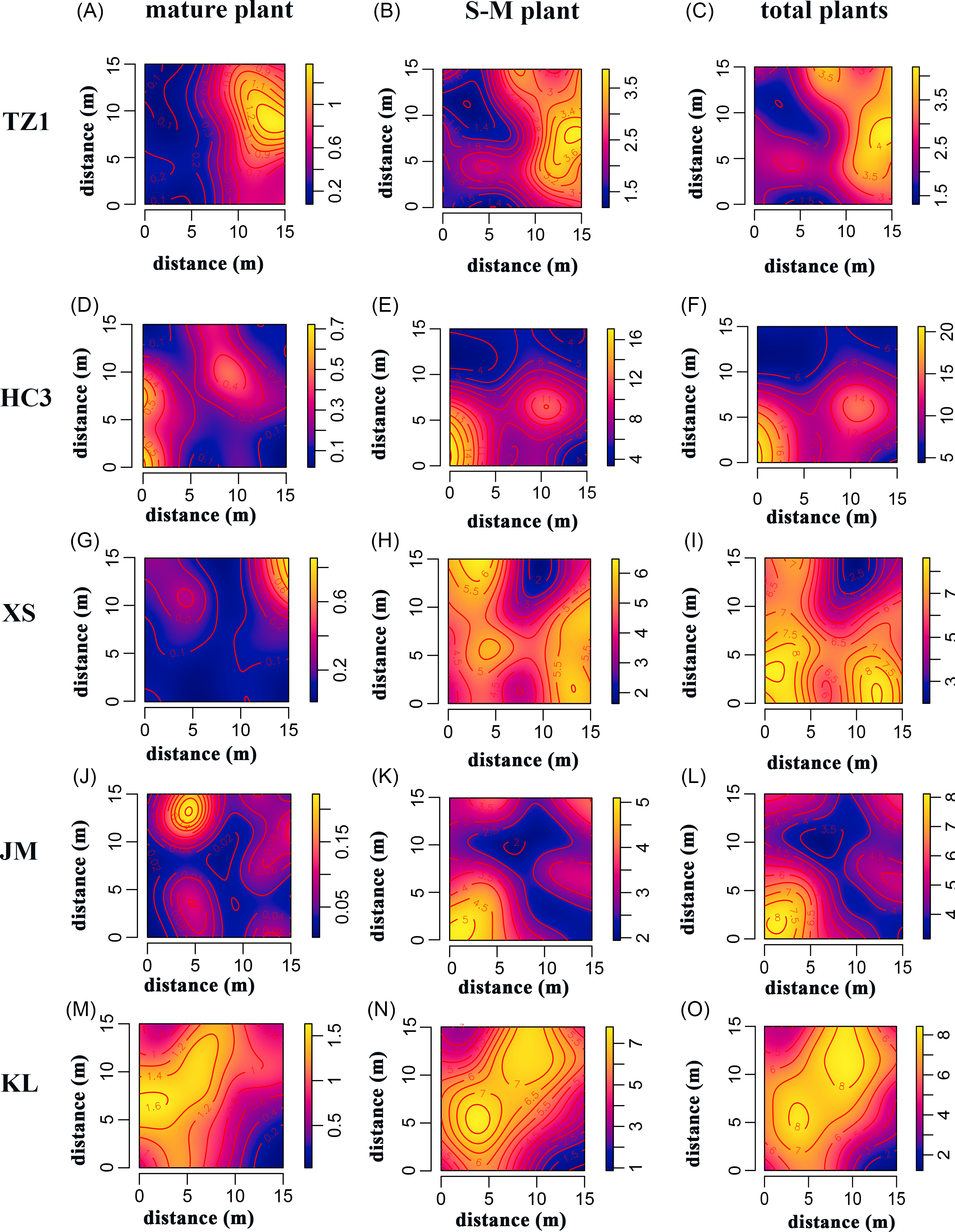

In Figure 5, the first column shows the density of mature plants, the second column shows the density of S-M plants, and the third column represents the total plant density for each group. Upon comparative analysis, a significant similarity is observed between the total plant density map and the S-M plant density map. This indicates that the distribution characteristics of the S. chamaejasme population are primarily influenced by the number of S-M plants. Outside the TZ region, the total plant density is notably higher than the S-M plant density, a difference likely attributed to the inclusion of young plants. However, in the TZ region, where the number of young plants is relatively low, this difference is less pronounced. Further analysis reveals that the high-density areas in the S-M plant density map often radiate outward from the high-density areas in the mature plant density map. This pattern aligns with the clumped distribution feature of S. chamaejasme, suggesting that new plants tend to establish near the parent plants.

Figure 5. Density of different age classes of Stellera chamaejasme individuals across five study sites in the natural alpine grasslands on the eastern side of the Qilian Mountains in China: Tian zhu Tibetan Autonomous County (TZ), Huang cheng Grassland (HC), Xi shui Nature Reserve Station (XS), Shan dan Military Horse Farm in Zhangye City (JM), and Kang le Grassland (KL). Each row corresponds to a distinct study site: (A–C) TZ, (D–F) HC, (G–I) XS, (J–L) JM, and (M–O) KL; each column represents the density distribution for a specific plant group: subadult plants and mature plants (S-M). Color bar: kernel density estimate; blue to yellow indicates low to high plant density.

Specifically, the high-density distribution centers in the TZ and XS regions are similar, both within the range of 10 to 15 m (Figure 5B and 5H); the high-density distribution centers in the HC and JM regions are similar, both within the range of 0-5 m (Figure 5E and 5K); while the high-density distribution center range in the KL region is larger, spanning 0 to 15 m (Figure 5N). From the total plant distribution density map, it can be observed that the distribution density value in the HC region is the highest (Figure 5F), while the distribution density value in the TZ region is the lowest (Figure 5C). Meanwhile, the highest distribution density values in the XS, JM, and KL regions show similarity (Figure 5I, L, and O). This demonstrates that there are evident differences and characteristics in the distribution density of S. chamaejasme across different regions, which may be caused by factors such as environmental conditions, soil fertility, and light exposure.

Stellera chamaejasme is recognized as an indicator plant for degraded grasslands due to its extensive growth and rapid invasion characteristics (Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Tang, Jiang, Duan and Chang2019). Because S. chamaejasme has caused serious damage to the ecological balance of grasslands, it is of great significance to investigate the reasons for its rapid invasion. This phenomenon is not only related to the biological characteristics (He et al. Reference He, Detheridge, Liu, Wang, Wei, Griffith, Scullion and Wei2019), allelopathic effects (Song et al. Reference Song, Li, Cheng, Song and Huang2023), and soil regulation capabilities of S. chamaejasme (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Li, Xing, Chen, Huang and Gao2020), but it is also closely linked to its spatial distribution patterns (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Li, Zhao, Ren, Nie, Jia, Li and Li2019). This study indicates that the spatial distribution of S. chamaejasme populations varies across different regions, yet there are also distinct commonalities. The overall distribution pattern and the distribution pattern of juvenile plants are quite different from each other. However, the overall distribution pattern of S. chamaejasme is highly similar to that of subadult plants, which can also be interpreted as the distribution pattern of the entire S. chamaejasme community being dominated by subadult plants.

The distribution pattern of S. chamaejasme hereafter referred to as exhibits an overall transition from aggregated to random distribution, consistent with findings reported by Ren et al. (Reference Ren, Zhao and An2015). Under highly heterogeneous environmental conditions, plant populations typically display aggregated distribution patterns, potentially due to individual clustering in resource-rich habitat patches or facilitation through intraspecific positive interactions (Daleo et al. Reference Daleo, Alberti, Chaneton, Iribarne, Tognetti, Bakker, Borer, Bruschetti, MacDougall, Pascual, Sankaran, Seabloom, Wang, Bagchi and Brudvig2023). Conversely, random distribution tends to emerge in the absence of significant intraspecific interactions (O’Dwyer et al. Reference O’Dwyer and Cornell2018). This distributional transition in S. chamaejasme facilitates its growth and expansion. During early grassland succession, S. chamaejasme lacks competitive advantages due to smaller individual size, limited resource acquisition capacity, and reduced resistance to interspecific competition and sandstorm disturbances, necessitating aggregated distribution to enhance risk resilience (Ren et al. Reference Ren, Zhao and An2015). As it becomes a dominant species, the distribution pattern naturally shifts toward non-aggregated forms, enabling more uniform resource utilization and reducing overreliance on singular resources, thereby enhancing population stability and adaptability (Wiegand et al. Reference Wiegand, Wang, Fischer, Kraft, Bourg, Brockelman, Cao, Cao, Chanthorn, Chu and Davies2023). Previous studies indicate that the transition from aggregated to non-aggregated distribution with increasing invasion intensity reflects a shift in intraspecific relationships from facilitation to competition (Ren et al. Reference Ren, Deng, Shang, Hou and Long2013). This behavioral shift promotes patch expansion, coalescence, and numerical proliferation of S. chamaejasme populations (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Li, Zhao, Ren, Nie, Jia, Li and Li2019). Notably, in the HC and KL regions, S. chamaejasme maintains persistent aggregated distribution across scales, suggesting exceptional environmental adaptation. The higher population density and abundance in these areas imply superior habitat suitability, where soil resources sustain greater S. chamaejasme density per unit area, potentially explaining this regional divergence.

Furthermore, the overall distribution pattern of S. chamaejasme closely aligns with that of subadult individuals, indicating their dominance in shaping population spatial structure. Quantitative surveys revealed subadult plants constitute greater than 60% of S. chamaejasme populations, reflecting both demographic structure and adaptive strategies across habitats. The aggregated distribution of subadults likely stems from limited seed-dispersal capacity, promoting germination near maternal plants, and potential survival benefits from intraspecific facilitation within clusters (Luo et al. Reference Luo, Zhang and Fang2021). Consequently, the numerical dominance and spatial characteristics of subadult plants significantly influence the overall distribution pattern of S. chamaejasme populations.

The most notable finding of this study is the lack of significant spatial correlations among different age classes of S. chamaejasme. This discovery effectively explains the species’ rapid invasion of grasslands, as the absence of resource competition among individuals reduces major growth constraints. Spatial independence between age classes enables populations to utilize limited resources more efficiently, alleviating growth suppression caused by resource competition and thereby enhancing overall survival probability and reproductive success (Zhang and Tielbörger, Reference Zhang and Tielbörger2020). Additionally, such spatial independence may create diverse habitats and resource niches for other species, increasing ecosystem species richness and niche breadth, which strengthens ecosystem stability and functionality (Wiegand et al. Reference Wiegand, Wang, Anderson-Teixeira, Bourg, Cao, Ci, Davies, Hao, Howe, Kress, Lian, Li, Lin and Lin2021). This aligns with Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Sun, Du, Wu, Zheng, Zhang, Liu and Wu2014), who found that S. chamaejasme can protect neighboring plants from overgrazing by livestock. Additionally, S. chamaejasme is rarely consumed by herbivores due to its chemical defenses and unpalatability, prompting herbivores to shift their foraging to other plant species (You et al. Reference You, Ma, Guo, Kong, Shi, Wu and Zhao2018). This selective foraging behavior compresses the habitat space and reduces resource utilization efficiency of other plants, while S. chamaejasme exploits limited resources more effectively. Studies demonstrate that plant life stages in resource-abundant environments may exhibit reduced interdependence (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Ji, Zhang, Zhang, Akram, Dong and Deng2023), as ample resources diminish interactions between individuals, allowing age classes to grow relatively independently (Akram et al. Reference Akram, Zhang, Wang, Shrestha, Malik, Khan, Ma, Sun, Li, Ran and Deng2022). This mechanism directly facilitates the spatial independence and expansion of S. chamaejasme.

This study further reveals that S. chamaejasme exhibits a distinct distribution pattern centered around mature plants. This phenomenon may arise because larger clumps provide shelter for smaller individuals (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Zhao, Shi, Sheng, Ren and He2011) or because microhabitats created by mature clumps (accumulated plant litter) supply essential nutrients for the growth of younger clusters (Durán-Rangel et al. Reference Durán-Rangel, Gärtner, Hernández and Reif2012). Such a pattern not only enhances population stability but also ensures the growth and reproduction of juvenile plants, significantly facilitating S. chamaejasme’s grassland invasion. High-density zones of S. chamaejasme populations typically radiate outward from areas dominated by mature plants, indicating a preference for establishment near adult individuals. This distribution pattern reduces interspecific competition while securing favorable conditions for juvenile growth, thereby supporting the species’ proliferation and invasion success. Importantly, these findings offer critical insights for management strategies. Controlling the density of mature plants may effectively curb S. chamaejasme expansion, as mature individuals serve as focal points for seedling establishment and growth.

This study elucidates the invasion mechanisms of S. chamaejasme and provides insights for its control and grassland restoration. During the initial invasion phase, S. chamaejasme spreads predominantly around mature plants (Figure 5) that facilitate the establishment of juveniles and subadults by offering shelter and improving microhabitat conditions. After securing initial growth space (0 to 1 m), juveniles and subadults compete for resources through aggregated distribution. As their competitive dominance increases (1 to 3 m), spatial patterns gradually transition from aggregated to random distribution, accelerating grassland invasion. However, under favorable soil conditions, S. chamaejasme maintains aggregated distribution to maintain high density per unit area, reinforcing its spatial dominance (Figure 3). Simultaneously, the lack of significant correlations among different age classes minimizes intraspecific resource competition, enabling efficient resource utilization and enhancing population survival and reproductive success (Figure 4).

The overall distribution pattern of S. chamaejasme is primarily driven by subadult plants. Therefore, control and restoration efforts should prioritize monitoring the growth dynamics of subadult populations. However, due to weak inter–age class correlations, strategies targeting a single age class may yield limited effectiveness. Given that mature plants dominate invasion centers, their control remains essential. An integrated strategy managing both mature and subadult plants is critical. During early invasion stages, the focus should be on mature plant control. Mechanical mowing sustained for 3 yr can be employed, concurrently combined with autumn mowing and reseeding to optimize grassland restoration (Li et al. Reference Li, Song, Wang, Wang and Yin2021). For reseeding, Mongolian wheatgrass (Elymus dahuricus Turcz.) and crested wheatgrass [Agropyron cristatum (L.) Gaertn.] are recommended, as studies indicate their tolerance to the allelopathic effects of S. chamaejasme (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Meng, Dang, Song and Zhuo2019). However, mechanical mowing may cause ecosystem damage. Although reseeding mitigates this issue, it becomes logistically impractical during advanced invasion stages due to the overwhelming workload. Therefore, control efforts during later phases should shift to subadult plants. Given their large numbers, a combined chemical–physical approach such as mowing followed by targeted herbicide application is suggested. The herbicide formulation Langdujing (675 ml ha−1) plus an organosilicon adjuvant (112.5 ml ha−1) is recommended, as it effectively controls S. chamaejasme while reducing the damage to forage grasses caused by using Langdujing alone (Gang et al., Reference Gang, Wang and Li2008; Bao et al. Reference Bao, Wang and Zeng2015). This approach is expected to prove effective. Consequently, future research should prioritize spatial distribution analysis to identify factors driving the distribution heterogeneity of S. chamaejasme across grasslands. Comparative studies of regional environmental variables could clarify its habitat preferences, enabling targeted control through population suppression and soil amendments altering soil fertility to create unfavorable growth conditions. These methods would not only curb invasion but also advance theoretical frameworks for grassland ecosystem restoration.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Funding statement

No funding was received for this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.