Introduction

Based on agenda-setting theory (Dearing et al., Reference Dearing, Rogers and Rogers1996; McCombs & Shaw, Reference McCombs and Shaw1972), prior studies on immigration attitudes (Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014) have argued that media salience can aggravate anti-immigrant attitudes by creating an information environment that portrays immigration as a society's main problem. However, most of the empirical evidence on whether media salience induces anti-immigrant attitudes is contradictory. While one strand of research found that media salience induces anti-immigrant attitudes (Dunaway et al., Reference Dunaway, Goidel, Kirzinger and Wilkinson2011; Van Klingeren et al., Reference Van Klingeren, Boomgaarden, Vliegenthart and De Vreese2015; McLaren et al., Reference McLaren, Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2018), other studies have obtained null effects (Castanho Silva, Reference Castanho Silva2018; Czymara & Schmidt-Catran, Reference Czymara and Schmidt‐Catran2017; Jungkunz et al., Reference Jungkunz, Helbling and Schwemmer2019; Larsen et al., Reference Larsen, Cutts and Goodwin2020; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Simon, Hudson and van Heerde‐Hudson2021).

To fill this gap in the research and to advance our understanding of how media salience influences attitudes towards immigrants, this paper re-evaluates the implication of issue importance, that is, public issue salience. Previous studies have used the level of importance of the issue for the country or concerns people have for the issue to measure anti-immigrant attitudes based on the assumption that issue importance leads to threat perception (e.g., Dunaway et al., Reference Dunaway, Goidel, Kirzinger and Wilkinson2011). Building on the previous empirical tests (e.g., Jennings & Wlezien, Reference Jennings and Wlezien2015), I assume that the level of concern or importance of the immigration issue could be distinguished from anti-immigrant attitudes, depending on political landscapes. I posit that in a political landscape where the issue of immigration is a focal point of political competition, the issue primarily signals conflicts and carries a negative connotation. Consequently, public issue salience becomes closely related to anti-immigrant attitudes. On the other hand, when political parties maintain a welcoming stance in a consensual manner, public issue salience mainly signals the importance, not the problem status of the issue, resulting in a limited link between public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes. Accordingly, media salience has heterogeneous effects on anti-immigrant attitudes depending on political landscapes. In a polarizing environment, it heightens anti-immigrant attitudes yet in a consensual environment, its influence is limited to raising awareness of issue importance.

While there have been calls to determine how media salience influences public issue salience and anti-immigration attitudes (Czymara & Dochow, Reference Czymara and Dochow2018), prior work has highlighted their possible differences (Dennison et al., Reference Dennison, Kustov and Geddes2023; Hatton, Reference Hatton2021; Jennings & Wlezien, Reference Jennings and Wlezien2015; Kustov, Reference Kustov2023), such comparisons have been rare. This article compares two countries, the United Kingdom and Germany, which share similarities in being at the forefront of the recent debates surrounding the immigrant issue, with far-right parties capitalizing on it. However, their major differences lie in the reactions of major political elites to the event. The issue of immigration has been polarizing among major political parties in the United Kingdom since the 2010s, while German major political parties reached a consensus to maintain a welcoming stance from the early stage of the so-called 2015 refugee crisis. I expect that these differences provide fertile grounds for comparison.

Previous works on the topic of media salience, public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes have been limited to aggregate-level analysis or correlation tests. This article overcomes the methodological challenges associated with making this comparison by employing individual-level longitudinal data analysis using the British Election Study (BES) and Leibniz Institute for Social Sciences' GESIS panel data. I matched media article data to individual-level survey data to observe dynamic fluctuations in media salience and individuals' public issue salience and anti-immigration attitudes.

The comparative analyses generate insights into the possible role of the political landscape that supports the study's argument. The analyses illustrate that in the United Kingdom, where major political parties are polarized over the immigration issue, public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes are closely related over time. Thus, media salience heightens anti-immigrant attitudes and public issue salience simultaneously. However, in Germany, where major political parties hold a consensual welcoming stance on the immigration issue, public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes are not related; consequently, the effect of media salience is limited to public issue salience. In summary, when the immigration issue is politically polarizing, people regard the immigrant issue as important and negatively charged, so media salience heightens anti-immigrant attitudes. On the other hand, when the issue is politically salient but not at the centre of political contention, people consider the immigrant issue important but do not necessarily view it negatively. In that environment, media salience merely raises the awareness that the issue is important without affecting immigration attitudes. These findings highlight that equating public issue salience with anti-immigrant attitudes could overestimate the influence of media salience and that country and political climate differences should be accounted for when measuring anti-immigrant attitudes and the scope of media effects.

Theoretical framework

Media salience and anti-immigrant attitudes

One of the media's most powerful roles is to set what the public should be thinking by reporting on certain issues extensively in a short period of time, and it is referred to as agenda-setting (Cohen, Reference Cohen1963; McCombs & Reynolds, Reference McCombs, Reynolds, Bryant and Zillmann2002; McCombs & Shaw, Reference McCombs and Shaw1972). The media's agenda-setting shapes perceptions of what issues a country is facing or society's main concerns (McCombs & Reynolds, Reference McCombs, Reynolds, Bryant and Zillmann2002; McCombs & Shaw, Reference McCombs and Shaw1972). It further affects attitudes towards the issue even without a specific tone or framing since media coverage activates individuals' pre-existing knowledge, which facilitates their judgements about it (priming theory; Iyengar & Kinder, Reference Iyengar and Kinder1987). For instance, priming national identity exacerbates affective polarization towards undocumented immigrants (Wojcieszak & Garrett, Reference Wojcieszak and Garrett2018). The media has substantial influence even over people who do not directly consume it, for instance, through interpersonal communication (Peter, Reference Peter2004; Schlueter & Davidov, Reference Schlueter and Davidov2013; Zucker, Reference Zucker1978). The influence is amplified in the digital media era, as the Internet increases the chances of incidental exposure to news and political discussion (Bode, Reference Bode2016; Gottfried & Shearer, Reference Gottfried and Shearer2016). Media salience is the key determinant of agenda-setting, and it encompasses various concepts such as attention. In this study, following the work by Kiousis (Reference Kiousis2004), media salience refers to the state in which an issue emerges as a prominent topic of discussion in the media. In short, media salience indicates the state where the issue receives extensive media coverage.

Scholars of immigration studies have examined the media's agenda-setting effects on immigration attitudes by employing the concept of media salience. Various measures have been used to measure the media salience of the immigration issue – the extent to which immigration is extensively discussed in the media – such as the volume of media articles (Van Klingeren et al., Reference Van Klingeren, Boomgaarden, Vliegenthart and De Vreese2015), external events (Czymara & Schmidt-Catran, Reference Czymara and Schmidt‐Catran2017) and immigration policy (Flores, Reference Flores2017) (see the review by Eberl et al., Reference Eberl, Meltzer, Heidenreich, Herrero, Theorin, Lind, Berganza, Boomgaarden, Schemer and Strömbäck2018).

Past studies have concluded that media salience heightens the hatred of immigrants since anti-immigrant attitudes often originate from economic or cultural threats perceived due to immigration (Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014). Empirical evidence shows that, indeed, media salience increases the perceived importance of the issue (Dunaway et al., Reference Dunaway, Goidel, Kirzinger and Wilkinson2011; Van Klingeren et al., Reference Van Klingeren, Boomgaarden, Vliegenthart and De Vreese2015; McLaren et al., Reference McLaren, Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2018) and concerns about immigration (Czymara & Dochow, Reference Czymara and Dochow2018). Yet some researchers have observed that media salience has less influence on anti-immigrant sentiments than is widely assumed. Morales et al. (Reference Morales, Pilet and Ruedin2015) found that media coverage of immigrants did not significantly affect people's attitudes in several European countries. Multiple studies have concluded that even media coverage of events in which immigrants or members of an ethnic minority group perpetrated violence – such as the 2015 Paris attack (Castanho Silva, Reference Castanho Silva2018; Jungkunz et al., Reference Jungkunz, Helbling and Schwemmer2019), the 2015-2016 New Year's Eve assaults in Cologne (Czymara & Schmidt-Catran, Reference Czymara and Schmidt‐Catran2017), the 2016 Berlin Christmas market attack (Larsen et al., Reference Larsen, Cutts and Goodwin2020) – did not affect attitudes towards immigration.

I argue that these inconsistent results could be due to the employment of public issue salience as a measure of anti-immigrant attitudes without contextualizing the political environment. By employing the concept of public issue salience and considering various political landscapes and elite competition cues, this study seeks to enhance our understanding of the impact of media salience. In the following section, I explore the definition of public issue salience and elucidate how it may diverge from immigration attitudes depending on the political landscape.

Public issue salience, political landscapes and media salience

In essence, public issue salience reflects the importance an individual places on an issue, encompassing elements of concern and caring (Boninger et al., Reference Boninger, Krosnick, Berent, Fabrigar, Petty and Krosnick2014; Krosnick, Reference Krosnick1990; Oppermann, Reference Oppermann2010). Public issue salience encompasses both psychological and behavioural dimensions since the perceived importance can affect political behaviour (Dennison, Reference Dennison2019). Perceived importance prompts voters to regularly contemplate the issue and to seek out relevant information, further shaping political choices, such as voting, candidate evaluation and support for a policy (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Krosnick, Fabrigar, Krosnick, Chiang and Stark2016; Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2005). For instance, a voter who prioritizes addressing inflation is likely to research the economic policies proposed by various political parties and vote for the party that she considers the most competent in economic matters.

Public issue salience has often been measured by asking survey respondents ‘What is the most important problem (MIP)’.Footnote 1 Wlezien (Reference Wlezien2005) analysed US citizens' answers to the MIP question and the public preference for policy (whether or not to increase government spending) and found out that the meaning of public issue salience can be extended from the degree of importance to the problem status. Building on this finding, prior researchers have used public issue salience (MIP or concerns about immigration) as a proxy for anti-immigrant attitudes (e.g., McLaren et al., Reference McLaren, Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2018) when they study media effects on immigration attitudes. They assume that media salience can aggravate anti-immigrant attitudes by making the issue of immigration important or problematic, thus encouraging voters to perceive it as a threat.

I point out that this assumption should be revisited. Several studies have implied that public issue salience and preference might be less similar than previously thought when various political landscapes are considered. Jennings and Wlezien (Reference Jennings and Wlezien2015) showed that voters' preferences and public issue salience related to government spending are distinct concepts by comparing the United Kingdom and the USA using longitudinal data. In line with their work, Hatton (Reference Hatton2021) identified a low correlation between public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes using survey data from multiple European countries from 2004 to 2016. Also, in his analysis, the demographic characteristics for public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes were distinct. Being young and male was associated with higher levels of public issue salience, meaning that younger males were more likely to consider the issue important. On the other hand, being older and female was associated with higher levels of anti-immigrant attitudes, indicating that older females tended to hold more negative views towards immigrants. A review by Dennison (Reference Dennison2019) observed that public issue salience is volatile and easily affected by real-world cues such as protests and policy. Yet, immigration attitudes are very stable (Kustov et al., Reference Kustov, Laaker and Reller2021) and remain unaffected by fluctuations in media salience (Gavin, Reference Gavin2018). Dennison et al. (Reference Dennison, Kustov and Geddes2023) similarly observed that during COVID-19, public issue salience of the immigration issue significantly dropped yet immigration attitudes remained stable. However, the work by Kustov (Reference Kustov2023) demonstrated that while public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes can be distinct, people with anti-immigrant sentiments tend to prioritize the issue personally and nationally so that they are likely to be active in immigration-related political events.

Building on these works, I argue that the similarities and differences between public issue salience and anti-immigration attitudes should be revisited, especially when considering the political landscape. I suggest that the implications of public issue salience are determined by signals from political elites. As laypersons cannot experience most of the political events themselves, elites' interpretations of reality are essential to shaping public opinion, providing guidance for people's political decisions (Bennett & Entman, Reference Bennett and Entman2000; Edelman, Reference Edelman1985; Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). Political elites can persuade the public by framing issues in a manner that aligns with their interests (Chong & Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007a, Reference Chong and Druckman2007b), by appealing to their political identities (Campbell, Reference Campbell1980; Mason, Reference Mason2018) or by elevating the salience of the issue (Downes & Loveless, Reference Downes and Loveless2018). For instance, Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2011) presented that contextual factors such as immigration population can lead to the perception of immigration as a problem, particularly when the issue is nationally debated by political elites. However, at the same time, when the issue is of high importance to the public, political elites' attempts to persuade the public through framing or partisan cues have limited effects (Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller, Hangartner and Helbling2015; Lecheler et al., Reference Lecheler, de Vreese and Slothuus2009). In light of these observations, I focus on political landscapes, arguing that political competition can alter the implications of public issue salience. I posit that in a political environment where the immigrant issue is politically salient and acts as a divisive factor among major political parties, it primarily signals conflicts that the immigrant issue has negative connotations. Consequently, public issue salience becomes closely intertwined with anti-immigrant attitudes. On the contrary, when major political parties share a similar level of welcoming position regarding the immigrant issue, the immigrant issue remains neutral, allowing public issue salience to be separated from anti-immigrant attitudes.

Hypothesis 1a. Public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes indicate the same concepts when major political parties are divided over the issue of immigration.

Hypothesis 1b. Public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes indicate different concepts when major political parties share a similar welcoming stance on the issue of immigration.

Moreover, given differences in the political landscape, the influence of media salience will differ as well. When political parties are divided over the issue of immigration, so that the issue is politically charged, media coverage of the immigration issue will reinforce the politically polarizing nature of the issue, thus increasing threat perception and anti-immigrant attitudes. On the other hand, in a context where political parties share similar welcoming ideas about the immigrant issue, media coverage of the immigration issue will only signal the priority of the issue rather than divisiveness.

Hypothesis 2a. Media salience increases the public issue salience of immigration and anti-immigrant attitudes when major political parties are divided over the issue of immigration.

Hypothesis 2b. Media salience increases the public issue salience of immigration but does not increase anti-immigrant attitudes when major political parties share a similar welcoming stance on the issue of immigration.

Despite various attempts to clarify the political ramifications of public issue salience and its relationship with anti-immigrant attitudes in multiple countries, attempts to account for different political landscapes have been rare (see Jennings and Wlezien, Reference Jennings and Wlezien2015; Kustov, Reference Kustov2023). Moreover, previous works, which highlighted the possible differences between these concepts (Hatton, Reference Hatton2021; Jennings & Wlezien, Reference Jennings and Wlezien2015; Kustov, Reference Kustov2023), employed a correlation test at an aggregated level. To complement their shortcomings, I employ longitudinal data analysis at the individual level and perform various analyses.

Case selection

I compared the United Kingdom and Germany due to their similar histories of immigration, the successes of populist right-wing parties and different major political elites' reactions to the issue of immigration in recent years. The two countries have been historically the country of immigrants' destinations thanks to their advanced economies and democratic systems. As a result, they have a similar level of immigration population (12.4 per cent for the United Kingdom in 2014 and 12.8 per cent for Germany in 2014; OECD, 2023). Moreover, due to their history of colonial conquest, slavery and the Holocaust, the United Kingdom and Germany have been at the centre of public discourse about racism, particularly anti-black racism in the United Kingdom and anti-Semitism in Germany (MacMaster, Reference MacMaster2017). However, given the uncertainty surrounding the European free movement and the refugee crisis, far-right parties in both countries capitalized on concerns and achieved success. UK Independence Party (UKIP) scored the highest electoral results, surpassing major political parties in the 2014 European Parliament election and the Alternative for Germany (AfD) achieved its highest electoral score in the 2019 European Parliament election.

Nevertheless, the main political parties in the two countries have reacted very differently to immigrants and the success of far-right parties. In the United Kingdom, the issue of European integration has been one of the major sources of party competition that the public named as a major problem in the 2010s (Blinder & Richards, Reference Blinder and Richards2020; Evans & Mellon, Reference Evans and Mellon2019; Geddes & Peter, Reference Geddes and Peter2016). In response, not only UKIP, but major political parties took a restrictive stance on immigration. The 2010–2015 Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition agreement and the Conservative Party after 2015 aimed for a ‘hostile environment’ for ‘unwanted’ immigrants and so their policies included several restrictive measures such as a cap on non-European Union (EU) migration and a crackdown on sham international marriages. Facing the so-called 2015 refugee crisis and the increase in net migration from European countries due to free movement, the UK government led by the ruling Conservative Party opted out of the relocation scheme. Those decisions resulted in strong criticisms from opposition parties, making the issue politically salient and competitive (Alan, Reference Alan2015).

On the other hand, in Germany, Euroscepticism had remained on the fringe, with the failure of radical right parties – the Republicans, the German People's Union (DVU) and the National Democrats (NPD) (Lees, Reference Lees2018) – due to the stigmatization of National Socialism by political elites (Art, Reference Art2011). The political landscape shifted in 2013 by the foundation of the AfD. Started by former conservative party (Christian Social Union in Bavaria, CSU) members, it focused on Euroscepticism and foreign policy, achieving successful results for a newly built political party in the 2013 federal election and the 2014 European Parliament election (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer2023). However, the major political parties parted on different paths from the United Kingdom to the success of AfD and the surge of the so-called 2015 refugee crisis. In 2015, the German government was led by a coalition between the two biggest parties across different political ideologies: the conservative parties, the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) and the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU) and the liberal party, Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Contrary to the United Kingdom, the conservative party CDU/CSU deviated from its traditional stance and agreed to take a welcoming stance towards refugees (Engler et al., Reference Engler, Bauer‐Blaschkowski and Zohlnhöfer2019; Mader & Schoen, Reference Mader and Schoen2019) so that AfD remained a main crusader of anti-immigrant policy. Major parties' stance on immigration in Germany remained stable long after the refugee crisis and even after AfD achieved its highest score in the 2019 European Parliament election (Gessler & Hunger, Reference Gessler and Hunger2022). Major political parties generally maintained non-inclusive formal and policy responses to AfD in parliament (Heinze, Reference Heinze2022).

Accordingly, the media coverage of the immigration issue in the two countries also followed different paths. As German political elites reached a consensus, German news coverage mainly mirrored the political elites' consensual views, whereas British news media's report aligned with their editorial lines and was more negative and polarized (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Garcia‐Blanco and Moore2015).

For these reasons, I found the United Kingdom and Germany are appropriate for my analysis. Both countries experienced external shocks and political events, such as the massive influx of immigrants and refugees as well as the success of far-right parties, yet major parties created different political landscapes. I set the United Kingdom as a country in which political elites placed the immigration issue at the centre of political competition so that the immigration issue signals negative messages. I chose Germany as a country in which the immigration issue is salient yet major political parties are not polarized over it and maintain a consensus, making the immigration issue neutral. I employed the data that covers the periods in which far-right parties achieved prominent electoral success (the 2014 European Parliament election for the United Kingdom and the 2019 European Parliament election for Germany) for comparison.

Data and methodology

Data

I used the sheer volume of news articles from traditional newspaper outlets to measure media salience. For individual-level variables (e.g., public issue salience, immigration attitudes), I employed BES survey data (Fieldhouse et al., Reference Fieldhouse, Green, Evans, Mellon, Prosser, de Geus, Bailey, Schmitt and van der Eijk2020) and Leibniz Institute for Social Sciences' GESIS panel data (GESIS, 2021). I employed the waves around the major political event related to immigration, namely, the success of the far-right parties in the European Parliament. I chose the three waves around the 2014 European Parliament election for the United Kingdom (waves 1–3) and the 2019 European Parliament election for Germany (waves ga, gb, gc). Waves 1–3 from the UK data were conducted between February and October 2014.Footnote 2 Waves ga, gb and gc from German data were conducted in 2019.Footnote 3 Hypothesis 1 posits that the similarities and differences between public issue salience and anti-immigration attitudes depend on political contexts. I test it using only the survey data since public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes are at the individual respondent level. Hypothesis 2 posits that the scope of the influence of media salience on public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes depends on political contexts. I test it by incorporating the news article data with the survey data.

For the media articles, quality newspapers – left- and right-leaning – and tabloids were chosen to reflect diverse political perspectives on the issue of immigration. For the quality UK papers, I analysed The Times (including the centre-right Sunday Times) and the centre-left The Guardian; the quality German newspapers were the centre-right Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) and the centre-left Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ). The Sun and BILD were chosen as tabloids in the United Kingdom and Germany, respectively.

I collected articles from LexisNexis, Factiva and FAZ's own website, FAZ.net, spanning from February 2014 to October 2014 for the United Kingdom and from February 2019 to August 2019 for Germany, reflecting differences in survey timing. I used broad keywords developed in previous studies (Boomgaarden & Vliegenthart, Reference Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2009; Czymara & Dochow, Reference Czymara and Dochow2018) to overcome the issue of personal subjectivity and to return a variety of articles related to immigrants, from naturalization to terror against immigrants (see the Appendix). I did not include the keywords ‘United Kingdom’ or ‘Germany’ in the search string to avoid limiting the articles to those about domestic events. Past studies have found that the public is not only influenced by incidents in their own country but also by those that occur abroad. For instance, German attitudes towards immigration became more negative following the 9/11 attacks in the United States (Schüller, Reference Schüller2016).

I downloaded only articles that included the keywords in their headlines. Headlines are one of the most important ways people get a (glimpse of) information. News coverage is often written in an inverted pyramid style, with the headline highlighting the main points of the piece (Kiousis, Reference Kiousis2004). Many people are ‘entry-point readers' – they read only the headlines to get an overview of the article (Holsanova et al., Reference Holsanova, Rahm and Holmqvist2006) – which means that headlines are the main determinants of how people remember articles (Ecker et al., Reference Ecker, Lewandowsky, Chang and Pillai2014). The importance of headlines is reinforced online; 59 per cent of the online news links shared on X (formerly known as Twitter) by individuals were not clicked on at all (Gabielkov et al., Reference Gabielkov, Ramachandran, Chaintreau and Legout2016). That means, only their headlines are exposed to the X users.

After downloading the articles, two student assistants and I manually deleted the ones unrelated to immigration (e.g., bird's migration, migraine), yielding 696 articles for the United Kingdom and 1,638 for Germany. The discrepancy in the total number of articles originates from the differences in the data collection periods (approximately 3 months for the United Kingdom and 6 months for Germany). Per day on average, in the United Kingdom, 6.89 articles (SD = 3.94) and in Germany 8.58 articles (SD = 5.18) were published. The topics of the articles are diverse, ranging from policy issues (‘Sharp criticism of the laws on asylum'Footnote 4) to integration (‘All schools must teach what it is to be British'Footnote 5).

For the individual-level variables, I used BES and GESIS panel survey data. Since they are both individual-level longitudinal data, using them complements previous studies that performed aggregate-level analyses (e.g., Hatton, 2021). BES panel data have been collected from residents in England, Scotland and Wales since February 2014.Footnote 6 Since BES does not provide information about the country in which respondents or their parents were born, I used ethnicity to evaluate immigration status. I categorized people who identified as white British (approximately 90 percent of respondents) as natives and included them in the analysis (N = 25,280–27,172). I excluded the rest, who listed various other ethnicities (e.g., ‘White and Asian’, ‘any other white background’, ‘Black').

For Germany, GESIS panel data were used. The GESIS panel has been surveyed every 3 months since February 2014 (starting cohort: 4900 panelists). As with BES, only native Germans were included in my data (N = 4,286–4,949). Immigration status was measured by the respondent's country of birth and their parents’ country of birth. Those who were born in Germany and whose parents were also born in Germany were categorized as native Germans.

Operationalization: Media salience, public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes

The summary of the main variables is available in Table 1. Following the finding by Kiousis (Reference Kiousis2004) that the sheer volume of news is the most dominant dimension of media salience, I measured media salience using the number of newspaper articles related to immigrants. The number of news articles from 1 to 7 daysFootnote 7 before the interview was totalled and matched to the individual interview date (United Kingdom: M = 45.59, SD = 10.26; Germany: M = 58.84, SD = 13.7). This operationalization allows me to observe the dynamic fluctuations of media salience.

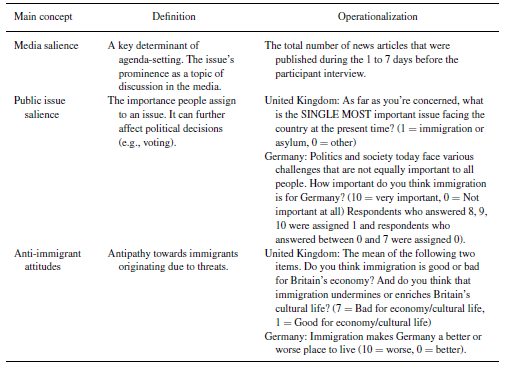

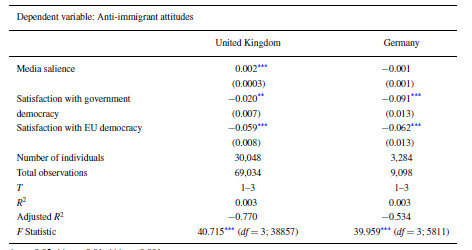

Table 1. Summary of main variables

Public issue salience was measured using the items asking how important respondents think immigration is. For the United Kingdom, an item asking what the respondent considered the MIP facing the country (MIP) was used (1 = immigration or asylum, 0 = other). Twenty-six per cent of respondents said immigration or racial tension is the most important issue. For Germany, the question asking the most important issue facing the country was asked only at the welcome survey so tracking the changes in public issue salience with the MIP question was not possible. Instead, I chose the question ‘Politics and society today face various challenges that are not equally important to all people. How important do you think immigration is for Germany?Footnote 8 (10 = very important, 0 = Not important at all; M = 7.35, SD = 2.29)’. This question is a part of the questionnaire batch ‘Has the Issue of Immigration Changed the Dynamics of European Parliament Elections?’, which aims to understand the political implications of the immigration issue, so I regard that it connotes both perceived importance and problem status of the issue for politics and society. In order to match the UK data, I recoded it to be a binary variable; people who answered higher than 7 were assigned 1 (immigration issue is very important) and the rest were assigned 0 (immigration issue is not important). 55.05 per cent of respondents regarded immigration as very important.

Anti-immigrant attitudes were measured with items asking about the threats they perceive due to immigrants (Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014). UK respondents were asked ‘Do you think immigration is good or bad for Britain's economy?’ and ‘And do you think that immigration undermines or enriches Britain's cultural life? (7 = Bad for economy/cultural life, 1 = Good for economy/cultural life)’. The mean of the two items was used for the analysis (M = 4.51, SD = 1.84). For Germany, I used the item asking if ‘Immigration makes Germany a better or worse place to live (10 = worse, 0 = better)Footnote 9 (M = 4.98, SD = 2.43)’. This item was employed in the European Social Survey Round 8 (2016) as a measure of immigration attitudes as well.

Control variables

I included only time-varying variables as controls in the analysis since time-constant variables were already controlled for within the individual levels in the panel data analysis I conducted. For the purpose of comparability, I chose similar controls for the two countries. For the United Kingdom, satisfaction with the way that democracy works in the United Kingdom and the EU were employed and for Germany, satisfaction with how the federal government works and the EU works were controlled.Footnote 10

I also accounted for party preferences in my analysis to have a nuanced understanding of the influence of the political landscape. For each country, the support for the two major parties (conservative and liberal) and the far-right party was accounted for. For the United Kingdom, I classified individuals who voted for the Conservative Party in the general election of 2010 as conservative party supporters. Those who voted for the Labour Party were categorized as liberal party supporters, while individuals who voted for the UKIP were considered far-right party supporters. In the case of Germany, conservative support was attributed to participants who cast their first or second vote for the conservative parties, CDU and CSU in the 2017 general election.Footnote 11 Liberal party support was assigned to those who voted for SPD, and far-right party support was determined when a respondent voted for AfD.

Analytical strategy

First, I tested Hypothesis 1 by analysing the correlation between public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes. Since public issue salience was a binary variable, a biserial correlation (or ordinary product-moment correlation) was calculated to evaluate the correlation between a dichotomous variable and a continuous variable (Tate, Reference Tate1954). I further performed correlation tests and compared the mean level of anti-immigrant attitudes by their supporting party. Additionally, I conducted the analysis using a random-intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM).Footnote 12

Hypothesis 2 was explored using methods that can take full advantage of the longitudinal data structure: conditional maximum likelihood (CML) and fixed-effect analysis. The variable for public issue salience was dichotomous so I employed CML. It transforms fixed-effect analysis for dichotomous outcomes (Andreß et al., Reference Andreß, Golsch and Schmidt2013). Since anti-immigration attitudes were continuous variables in both countries’ data, fixed-effects analysis was performed for both cases.

Results

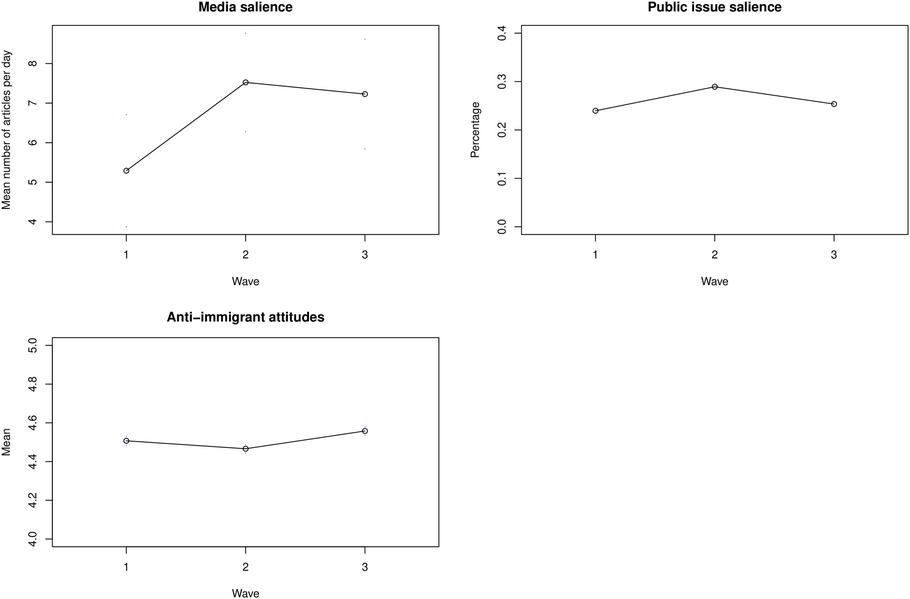

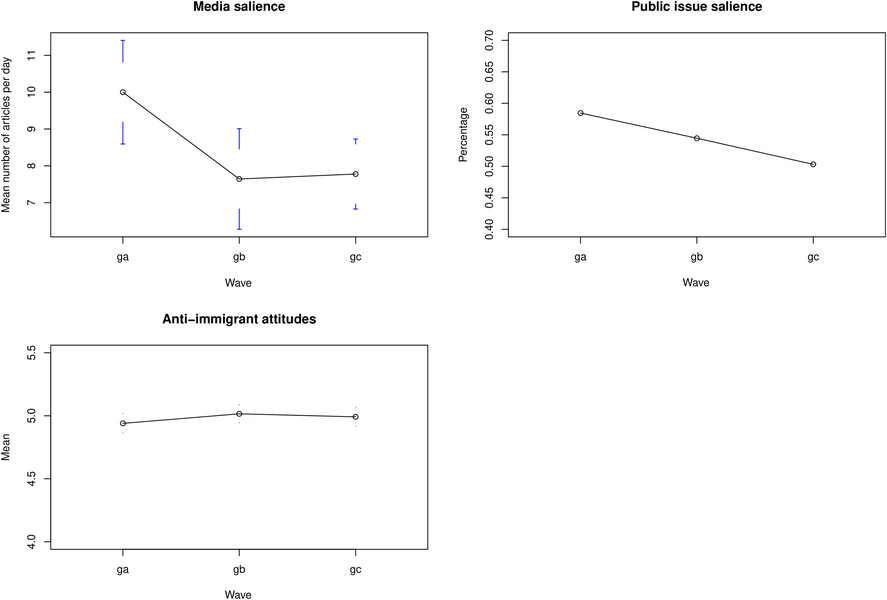

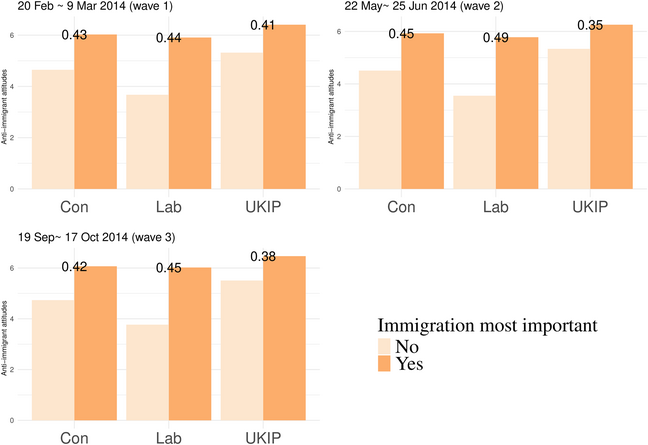

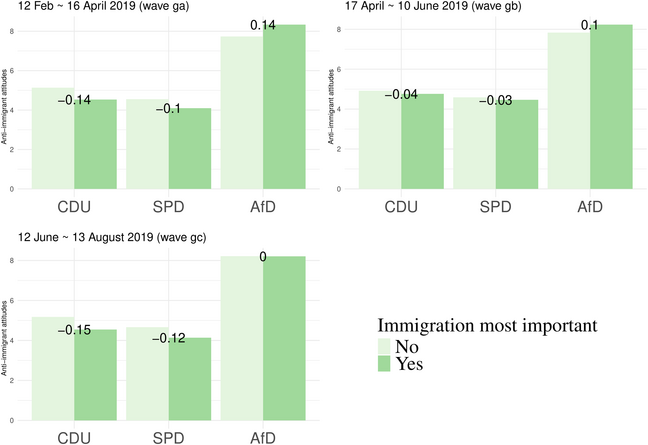

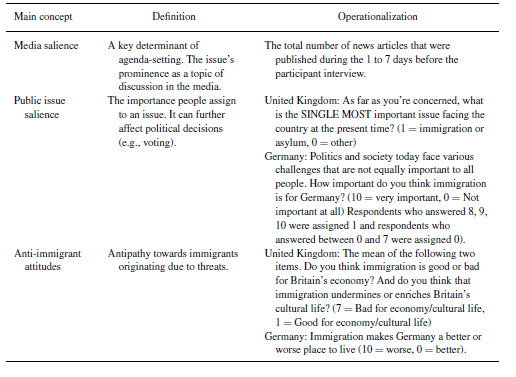

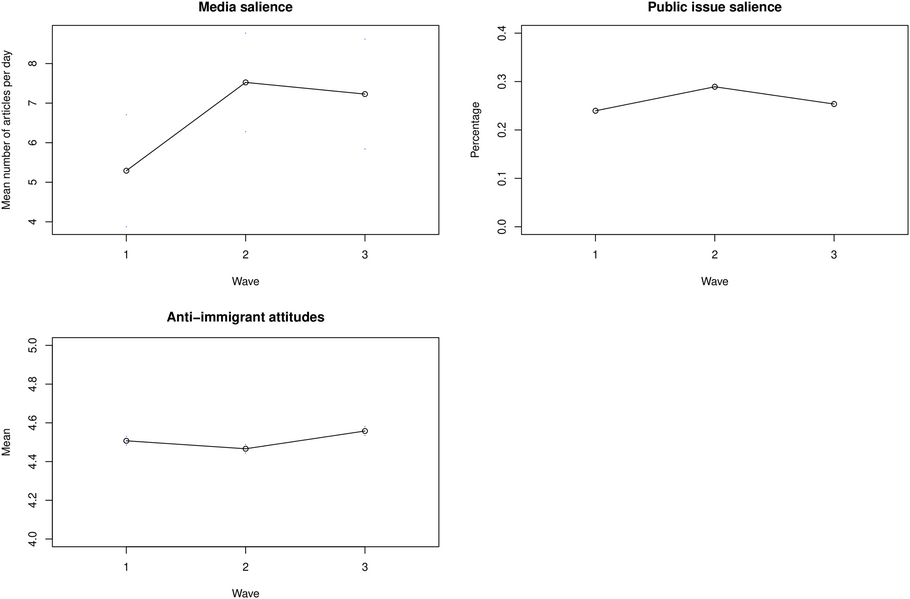

Before discussing the analyses, I present the dynamic fluctuations of media salience, public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes in the United Kingdom and Germany by wave in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 plots the trends in the United Kingdom during three waves around the major political event, the 2014 European Parliament election. Media salience and public issue salience increased slightly around the election. Anti-immigrant attitudes remained stable. Figure 2 depicts the trends in German data during three waves in 2019. In Germany, media salience and public issue salience declined together around the 2019 European Parliament election while anti-immigrant attitudes were stable. Both countries’ figures imply that media salience and public issue salience are closely associated while anti-immigrant attitudes are stable.

Figure 1. Heterogeneity across waves, the United Kingdom. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note. Wave 1 was conducted between 20 February and 9 March 2014. Wave 2 was conducted between 22 May and 25 June 2014. Wave 3 was conducted between 19 September and 17 October 2014. The European Parliament election took place on 22 May 2014.

Figure 2. Heterogeneity across waves, Germany. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note. Wave ga was conducted between 13 February and 16 April 2019. Wave gb was between 17 April and 10 June 2019. Wave gc was between 12 June and 13 August 2019. The 2019 European Parliament election was held on 26 May 2019.

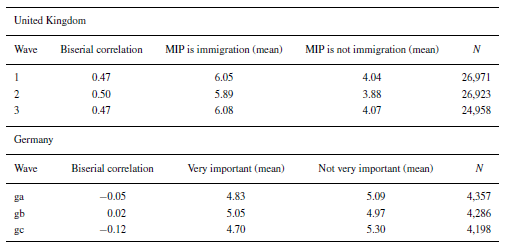

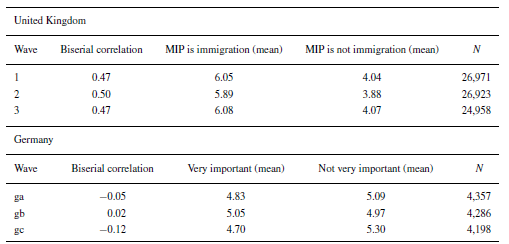

Hypothesis 1a maintains that public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes are closely related when political parties set the immigration issue at the centre of political competition (the United Kingdom) and Hypothesis 1b posits that they can be distinguished when the issue is not polarizing the major political parties (Germany). I first conducted correlation tests by wave to validate Hypotheses 1a and 1b (Table 2). In the United Kingdom, the biserial correlation between the two concepts was positive. They were generally at a moderately high level (0.47–0.5). In the meantime, people who consider immigration as the most important issue have a higher level of anti-immigrant attitudes. In Germany, I detected a correlation much smaller than the UK's correlation (−0.12 to 0.02). Furthermore, those who did not consider immigration an important issue had greater anti-immigrant attitudes in waves ga and gc yet the opposite was observed in wave gb. However, the differences between the two groups were generally very small and rather negligible.

Table 2. Hypothesis 1a and Hypothesis 1b testing. Correlations between public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes in the United Kingdom and Germany

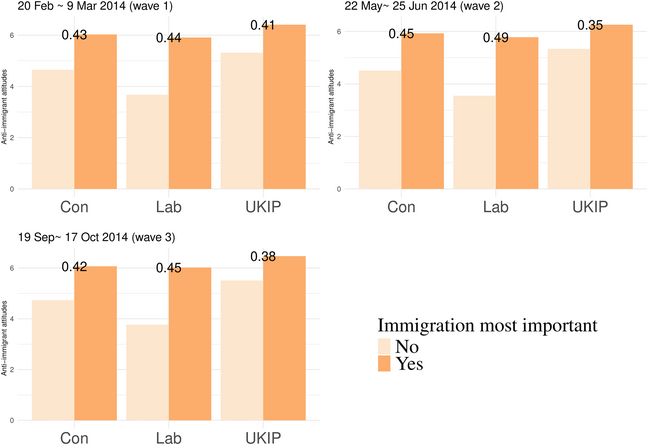

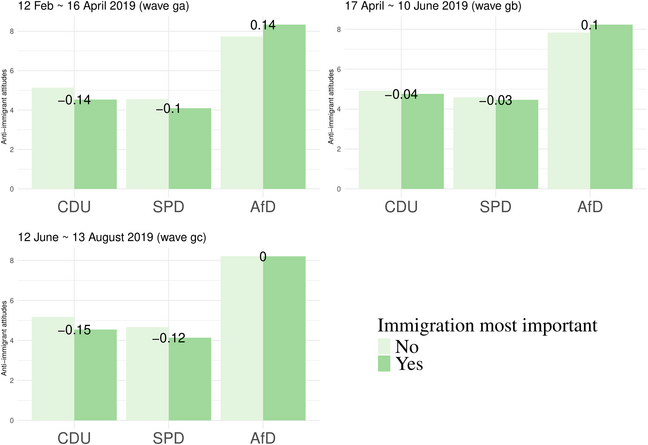

I further investigated the differences by supporting the party. In the United Kingdom (Figure 3), I observed moderately high positive correlations across waves 1–3. In all parties, individuals who named immigration as the MIP had a higher level of anti-immigrant attitudes than those who did not. Interestingly, Labour Party supporters exhibited the highest positive correlations. UKIP supporters showed the highest level of anti-immigrant attitudes across waves.

In the German case (Figure 4), generally, correlations were very small and negligible. Among supporters of conservative (CDU/CSU) and liberal (SPD) parties, there were negative correlations between public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes but the far-right party AfD supporters had a positive correlation. Also, conservative and liberal party supporters had lower levels of anti-immigrant attitudes when they regarded the immigrant issue as important. On the other hand, among AfD supporters, individuals who considered the immigrant issue important exhibited higher levels of anti-immigrant attitudes. Those observations imply the possibility that the relationship between public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes could change based on elite consensus.

Figure 3. Hypothesis 1a testing. Mean of anti-immigrant attitudes and correlation between public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes by supporting political party in the United Kingdom. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note. The number over the bar indicates the correlation.

Figure 4. Hypothesis 1b testing. Mean of anti-immigrant attitudes and correlation between public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes by supporting political party in Germany. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note. The number over the bar indicates the correlation.

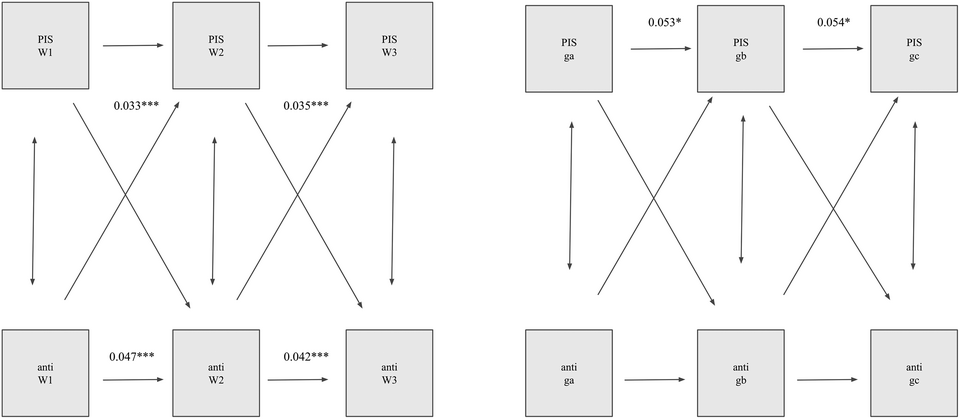

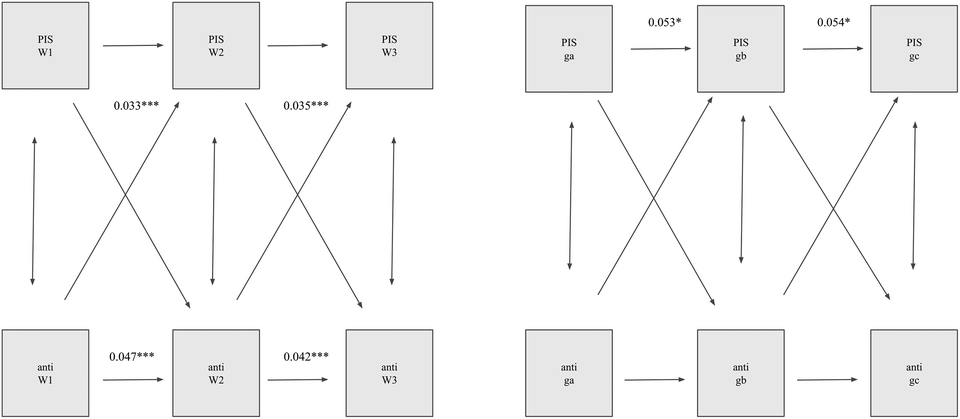

For a more thorough investigation, an RI-CLPM was performed to determine if there is a reciprocal relationship between public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes (Figure 5). The UK model resulted in a satisfying fit (Comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.989, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.984, Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.067). Public issue salience significantly and positively predicted future anti-immigration attitudes but anti-immigrant attitudes did not predict public issue salience. Anti-immigrant attitudes predict their future values, showing that immigration attitudes are stable. German data also resulted in a good fit (CFI = 0.982, TLI = 0.973, RMSEA = 0.065). However, the German model exhibited no relationship between public issue salience and anti-immigration attitudes as all coefficients were insignificant. Only public issue salience predicted its future values in a significant way.

In short, the analysis reveals that in the United Kingdom, where major political parties are divided over the issue of immigration, public issue salience and anti-immigration attitudes are closely and positively correlated (Hypothesis 1a is supported). On the contrary, in Germany, where major political parties take a consensual stance to welcome immigrants, even when the immigrant issue is controversial, for major party supporters, public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes are not closely related (Hypothesis 1b is supported). In the meantime, in both countries, for far-right party supporters, the immigrant issue always implies importance and problem status simultaneously.

Figure 5. Hypothesis 1a and Hypothesis 1b testing.

Note. All coefficients are standardized. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. PIS stands for public issue salience. Anti stands for anti-immigrant attitudes.

These empirical findings call into question the theoretical basis of previous studies on how media salience influences immigration attitudes. Under the assumption that public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes represent the same concept, previous scholars have used them interchangeably. My analyses suggest that they are not as closely correlated as previously thought if the immigrant issue is not a politically dividing issue, so that conflating the two concepts may have attributed to the conflicting results found in past research. In light of these findings, I proceeded to test Hypothesis 2, which focuses on the influence of media salience. If their similarities originate from political competition and the polarizing context of the issue, media salience will increase public issue salience as well as anti-immigrant attitudes (Hypothesis 2a). Conversely, if major political parties have a consensual welcoming stance, the influence of media salience will be limited to merely raising issue awareness (Hypothesis 2b).

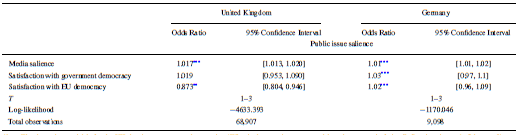

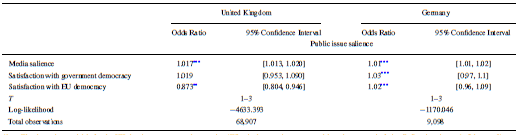

The analysis for Hypothesis 2 began with the public issue salience (Table 3). The analyses reveal that media salience significantly induced public issue salience, as hypothesized. In other words, media salience leads people to think immigration is an important issue. The same phenomenon was observed in Germany as well (p < 0.001).

Table 3. Hypotheses 2a and 2b testing. The CML model with the United Kingdom and German data

Note: The dependent variable for the UK data is an answer to the question ‘What is the most important problem the country is facing?’ (Immigration = 1, Others = 0).

The dependent variable for the German data is an answer to the question ‘How important do you think immigration is for Germany?’ (10 = Very important, 0 = Not important at all, answer 8–10 = 1, 0–7 = 0).

Abbreviations: EU, European Union.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

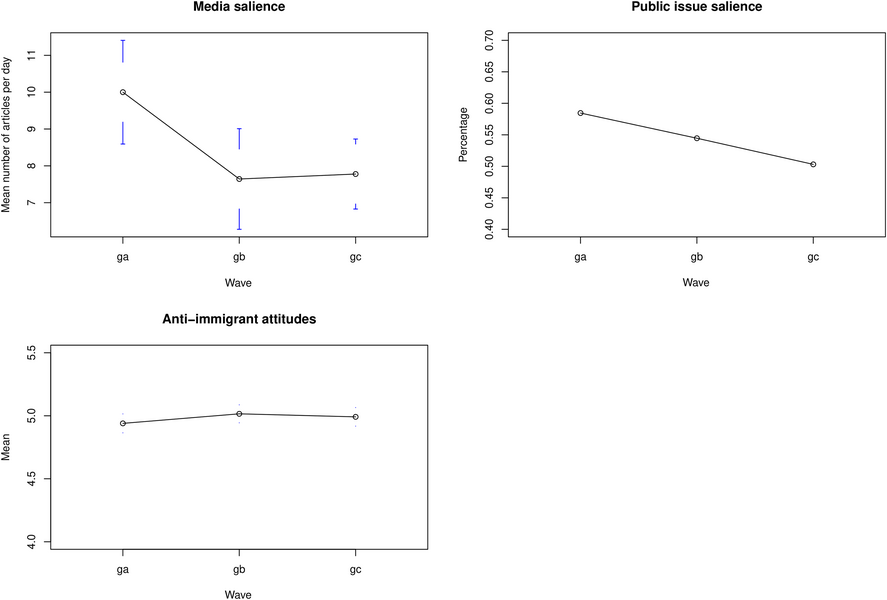

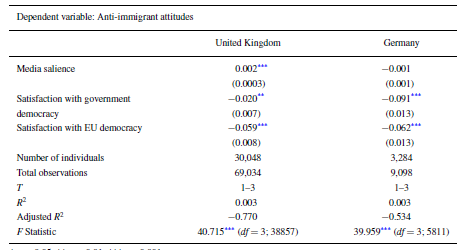

Table 4 reports the results of the fixed-effect analysis to study media salience's influence on anti-immigration attitudes. The analysis demonstrates that in the United Kingdom, media salience also significantly increased anti-immigrant attitudes (p < 0.001). Hypothesis 2a is supported. Satisfaction with how democracy works in the United Kingdom and the EU alleviated anti-immigrant attitudes. Then I moved to the German case. Unlike in the United Kingdom, media salience did not have a significant influence on anti-immigrant attitudes in Germany. Satisfaction with the federal government and the EU alleviated anti-immigration attitudes. To summarize, in Germany, media salience merely increased issue importance and did not affect anti-immigrant attitudes. Hypothesis 2b is supported.

Table 4. Hypotheses 2a and 2b testing. Fixed-effects analysis with the United Kingdom and German data

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The discrepancy between the United Kingdom and Germany hints at the reasons behind previous studies’ inconsistent findings regarding how media salience affects immigration attitudes. Prior results indicating that media salience does significantly influence anti-immigrant attitudes could have originated from failing to account for political contexts, resulting in the overestimation of media effects by using public issue salience to proxy for anti-immigrant attitudes.

Conclusion and discussion

This study explores the underlying reasons for the inconsistent findings in the literature regarding how media salience affects anti-immigrant attitudes. I find that these inconsistencies can be at least partly attributed to the tendency in prior works to not factor in political landscapes. I argue that public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes could be disentangled depending on the political contexts, particularly differences in political competition cues. Thus, conflating public issue salience with anti-immigration attitudes without accounting for political contexts could misconstrue the influence of media salience.

I employed multiple approaches to investigate the similarities and differences between public issue salience and anti-immigration attitudes as well as the scope of media salience's influence. To overcome the limitations of previous studies that employed aggregate-level correlation tests and did not consider contextual vulnerabilities, my analyses combined media article data and individual-level longitudinal data. Also, I compared two countries that have similarities in the immigration histories and far-right parties’ success but differences in the political elites’ decisions. The study provides evidence that the polarizing level of the issue of immigration among political elites plays a significant role in determining the relationship between public issue salience and anti-immigration attitudes and, consequently, the influence of media salience. The results from the United Kingdom data, where major political elites are divided over the issue, were consistent with previous findings that public issue salience leads to anti-immigrant attitudes. Media salience also significantly increased both of them. However, the German results contrasted with previous research. In Germany, a country in which major political elites reached a consensus on a welcoming stance at the early stage of the refugee crisis, the correlation between public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes was trivial. Also, media salience increased public issue salience but did not affect anti-immigrant attitudes.

These results make several contributions to the literature and suggest areas for future research. Perhaps most crucially, the findings highlight the importance of political elites' competition cues. A lack of consensus on the issue of immigration among the major political parties in the United Kingdom and the media coverage of divided politicians could have contributed to the dissemination of anti-immigrant messages. By contrast, German major politicians maintained a welcoming stance and distanced themselves from far-right party policy that media salience could have avoided entailing the increase of anti-immigrant attitudes. In short, the results suggest that the measure of attitudes and interpretation of media messages should be performed considering political contexts, highlighting the need to develop a new theory that incorporates the role of political context in media effects and public perceptions.

In addition, the findings of this study propose a revisit to the relationship between issue salience, immigration attitudes and electoral success. Despite the success of far-right parties across Western European countries, immigration attitudes have shown signs of improvement in recent years (Dennison & Geddes, Reference Dennison and Geddes2019). This implies that the success of the far-right parties may not necessarily originate from worsening immigration attitudes, but rather from their ability to position themselves as owners of the immigration issue, supporting issue ownership theory (Bélanger & Meguid, Reference Bélanger and Meguid2008; Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996; Powell & Whitten, Reference Powell and Whitten1993). Indeed, witnessing far-right parties attempting to exploit the immigrant issue during turbulent times, centre-right parties have achieved electoral gains by emphasizing immigration or strategically adopting hard-line positions (Downes & Loveless, Reference Downes and Loveless2018; Downes et al., Reference Downes, Loveless and Lam2021). However, the findings of this study suggest that issue salience and restrictive positions can be disentangled, allowing political parties to strategically employ inclusive policies to address the immigration issue.

This study bears several social implications for political elites and journalists. The results underscore that major political elites are pivotal in fostering social cohesion. The case with Germany implies that even when far-right parties are gaining political power if major political parties show cooperation over the immigration issue, interethnic relationships can remain relatively stable. In that, their responsibility extends beyond the mere acquisition of political power to actively foster harmony across political parties. This observation may have implications for Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries beyond Western Europe as well. Despite the structural distinctiveness in party competition dynamics due to the relative newness of democracy in CEE (Marks et al., Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006), the effects of the European integration issue on party competition are similar to those observed in Western European countries (De Vries & Tillman, Reference De Vries and Tillman2011; Marks et al., Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006). In the meantime, the findings call into question current journalistic practices that heavily prioritize political competition, as this emphasis may negatively impact interethnic relationships. Exploring alternative journalistic practices could potentially benefit society as a whole.

This study suffers from at least three limitations. The first is that its media analysis draws only on traditional news media (newspapers) and thus could have overlooked the growing influence of digital media outlets (Van Aelst et al., Reference Van Aelst, Strömbäck, Aalberg, Esser, De Vreese, Matthes, Hopmann, Salgado, Hubé and Stępińska2017). However, Djerf-Pierre and Shehata (Reference Djerf‐Pierre and Shehata2017) evaluated 23 years of media content data and public opinion data and found that the traditional media's agenda-setting effects do not decrease in a high-choice media environment, which increases confidence that my study captures the media's effects on the public. The second limitation is that the analysis for Hypothesis 1, which compared public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes, remains descriptive. I attempted to complement previous works, which often rely on aggregated level analysis, by using individual-level longitudinal data, yet a more comprehensive investigation is required.

The last limitation arises from data comparability. There was a 5-year gap between the analysis of the United Kingdom and Germany datasets. In an attempt to address this limitation, I conducted analyses around a major political event that occurred later, namely, the 2016 European referendum, determining whether the United Kingdom would leave the European Union. The passage of Britain's 2016 referendum was largely driven by fears of immigrants (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Goodwin and Whiteley2017; Ford & Goodwin, Reference Ford and Goodwin2017). My analyses, conducted during waves 7, 8 and 10,Footnote 13 presented that media salience increased both public issue salience and anti-immigrant attitudes, providing further evidence that a politically divided context can lead the immigrant issue to have a negative connotation. The results are available in the Supporting Information. Another issue with the comparability is the difference in the measurement items for public issue salience between the United Kingdom and Germany. In the United Kingdom, I employed the MIP question, while in Germany, the perceived importance of the immigration issue was used. The question used for Germany implies the problematic nature of the immigration issue by asking about its importance as a societal challenge, yet employing the MIP question in both contexts could enhance comparability.

Despite these limitations, this study makes a theoretical contribution to the field of media effects and immigration attitudes by highlighting the need to develop a new theory that incorporates the role of political context. Future studies could build on these findings to strengthen their research design and improve our understanding of media effects and immigration attitudes.

Acknowledgements

I thank Prof. Dr. Christopher Wlezien, Prof. Dr. Katrin Paula and Prof. Dr. Yannis Theocharis for their generous and helpful comments and support. Also, I thank participants at the 10th Conference of the European Survey Research Association 2023 for constructive comments. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflict of interest statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

The UK survey data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the British Election study at http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-8202-2. The German survey data that support the findings of this study are openly available in GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences at http://doi.org/10.4232/1.13785. The media article data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: LexisNexis at https://www.lexisnexis.com/, Factiva at https://www.dowjones.com/professional/factiva/ and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung at FAZ.net.

The R codes used for the analyses in this paper are available for replication purposes. They are included in the Supporting Information section.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table S1 Hypothesis 2a testing.

Table S2 Hypothesis 2a testing.

Data S1

Appendix

Keywords

The keywords I used in Factiva for the United Kingdom were as follows; immigra* OR migra* OR asylum* OR emigra* OR multicultur* OR intercultur* OR aslyum* OR refugee* OR foreigner* OR deport* OR (residence permit) OR visa* OR citizenship OR (permanent residen*) OR (work permit) OR (study permit) OR (work visa) OR (study visa) OR nationality OR (forced AND (wed* OR marri* OR engag*)) OR (parallel societ*) OR headscar* OR (honor murder) OR (hate preach*) OR burka* OR islam* OR muslim* OR (mohammed w/10 cartoon*) OR (naturali*) OR (family reunifi*) OR (sham AND (marri* OR wed*)) OR ((discrim* OR terror* OR threat* OR grop* OR rob* OR incident* OR sexual* OR assault* OR crime* OR violen* OR attack* integrat* OR bomb* OR crisis*) w/10 ((New Year) OR (New Year's) OR racis*)). The asterisk is a wildcard. There was a slight change for the search in LexisNexis to match the system's search command and connector rules.

The Factiva keywords for Germany were as follows; zuwand* OR einwand* OR migra* OR flücht* OR asyl* OR ausländer* OR geflüch* OR immigr* OR rassis* OR multikult* OR integrat* OR abschieb* OR abgeschob* OR aufenthaltsgeneh* OR Visum* OR Staatsbürgerschaft OR Niederlassungserlaubnis OR Aufenthalt* OR Aufenthaltserlaubnis OR Staatsangehörigkeit OR rassis* OR terror* OR anschlag* OR zwangshochzeit* OR zwangsheirat* OR parallelgesellschaft* OR kopftuch* OR ehrenmord* OR hassprediger* OR burka* OR islam* OR muslim* OR mohammedkarikatur OR (mohammed w/10 karikatur*) OR einbürgerung* OR Familienzusammenführung* OR Scheinehe* OR Zwangsverlobung* OR Scheinhochzeit* OR ((diskrim* OR terror* OR anschlag* OR Diebs* OR Vorfäll* OR sexuell* OR Übergriff* OR Täte* OR gewalt* OR Tötungsdelikt OR Messer*) w/10 (Silvester* OR rassis*)). Again, as with the UK data, keywords slightly changed according to the NexisLexis and FAZ.net's search command and connector rules.