1. Introduction

Energy communities have emerged as central models integrating economic, environmental, and social perspectives in energy choices (Cavallaro et al., Reference Cavallaro, Sessa and Malandrino2023). They signify a transformative approach fostering collective generation, management, and consumption of energy resources to address climate change, promote renewable sources, and enhance sustainability. Despite variations in terminology, energy communities essentially represent collaborative efforts towards decentralized energy production and consumption (Kyriakopoulos, Reference Kyriakopoulos2022). Understanding the motivations driving individual participation in energy communities is crucial, influenced by factors such as technology acceptance, legal frameworks, and geographical context. Economic disparities further shape adoption rates, with higher prevalence observed in wealthier northern European countries (Verde & Rossetto, Reference Verde and Rossetto2020). Moreover, sustainable communities prioritize values beyond economic gains, emphasizing mutual aid and renewable practices (Gui & MacGill, Reference Gui and MacGill2018). The design of grid charges plays a pivotal role in incentivizing engagement with clean energy and decentralized production (Abada et al., Reference Abada, Ehrenmann and Lambin2020). As the energy sector transitions towards digitalization, there is an increasing need for enabling technologies facilitating monitoring, data processing, and algorithm implementation within energy communities (Menniti et al., Reference Menniti, Pinnarelli, Sorrentino, Vizza, Barone, Brusco, Mendicino, Mendicino and Polizzi2022). The integration of these technologies is critical for the effective implementation and sustainability of energy communities, underscoring their role in promoting sustainable energy practices (Martínez-Peláez et al., Reference Martínez-Peláez, Ochoa-Brust, Rivera, Félix, Ostos, Brito, Félix and Mena2023).

This study emphasizes the role of social innovations in driving sustainable transitions (Dóci et al., Reference Dóci, Vasileiadou and Petersen2015), aligned with the importance of community-driven approaches in energy systems. While previous research highlights the motivations behind successful energy communities that encourage active participation (Sale et al., Reference Sale, Morch, Buonanno, Caliano, Somma and Papadimitriou2022), there remains a need for deeper insights into how these motivations translate into proactive citizen roles in energy transformation models (Otamendi-Irizar et al., Reference Otamendi-Irizar, Grijalba, Arias, Pennese and Hernández2022). Despite the extensive literature on the economic and environmental benefits of energy communities, gaps persist in understanding the socio-technical dynamics and wider participation in energy communities.

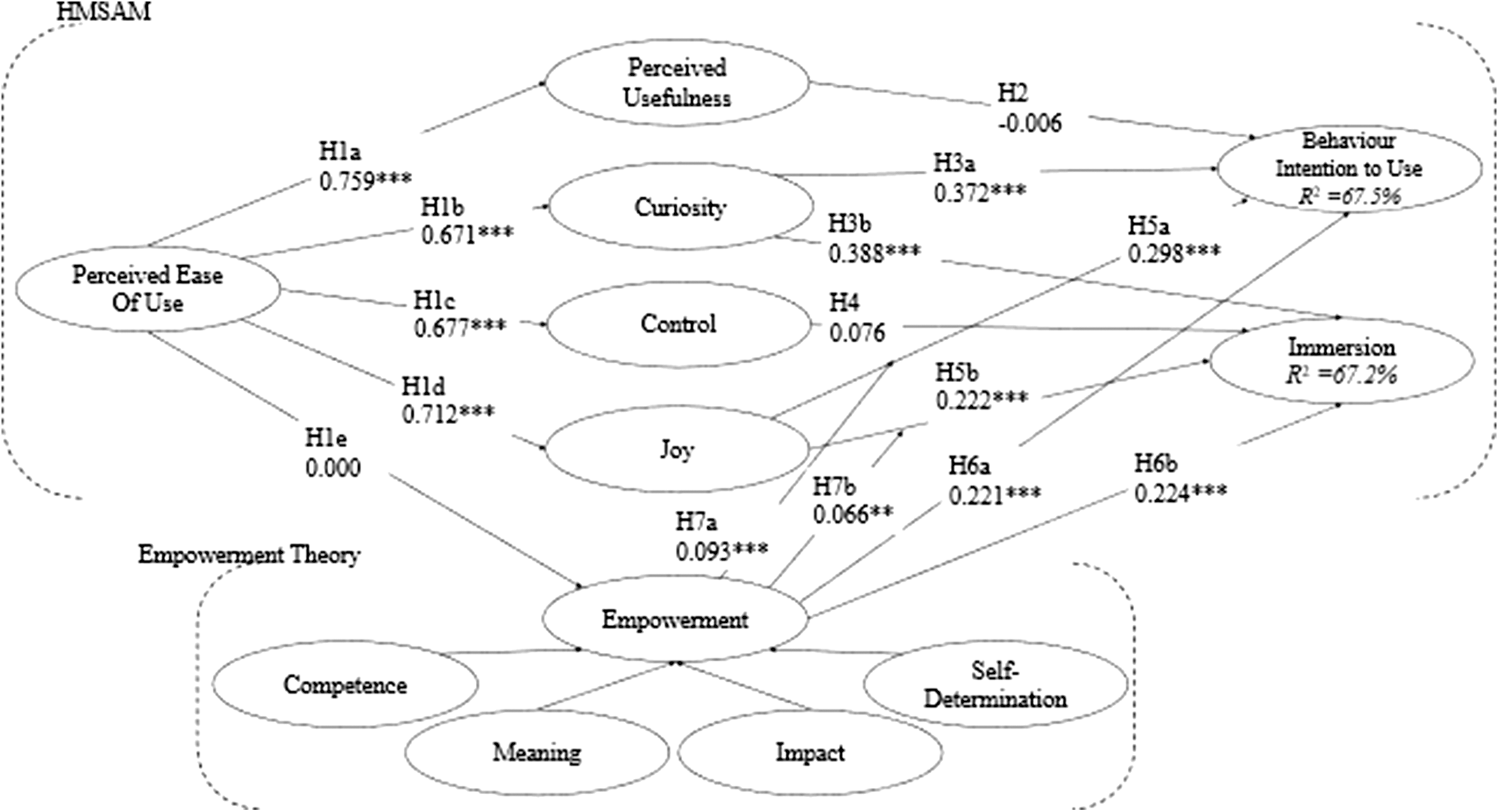

The primary objective of this study is to identify the motivations behind successful energy communities that encourage active participation focusing on the role of positive emotions, specifically hedonic motivations and empowerment. By doing so, the research aims to highlight the potential for energy communities to attract stakeholder investment and promote a proactive and meaningful participation of the citizens in the energy transformation model. Therefore, a model is developed based on two well-known theories: hedonic-motivation system adoption model and the empowerment theory. By complementing these two theories, it is possible to have a holistic understanding of these positive motivations on citizens’ decisions, comprehending how they can lead to purposeful participation in energy communities.

The contributions of this study are the following. First, by analysing the determinants of citizens engagement on energy communities, contributes to the on-going investigation on the topic of local strategies towards the decentralization and decarbonization of the energy systems, focusing not only on the technical factors, but especially on the role of the citizen. Second, by extending the hedonic-motivation system adoption model using the empowerment theory, the current study provides a deeper understanding of the psychological and emotional factors that drive individuals to participate in energy communities. This extension sheds light on how empowerment enhances engagement levels within these communities, ultimately supporting a broader energy transition. Finally, these findings offer valuable insights into strategies to foster community engagement and promote sustainable energy practices, contributing to the wider perceptions of energy transition and providing a strong foundation for understanding and improving the effectiveness of energy communities.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. The concept of energy communities and European framework

Energy communities are increasingly recognized as crucial for advancing sustainable energy by bridging local engagement and renewable resource utilization. They represent voluntary associations of diverse actors, including citizens, local authorities, and small to medium-sized enterprises, who prioritize environmental, economic, and social benefits over financial profits, thereby aligning with broader community goals (Arnould and Quiroz, Reference Arnould and Quiroz2022). A key feature of such initiatives is the role of prosumers, who can lower their energy costs and manage surplus generation, either storing it or selling it back to the grid (Gui & MacGill, Reference Gui and MacGill2018). Beyond energy production, energy communities contribute to social development goals by inspiring citizen participation, fostering renewable energy adoption (Otamendi-Irizar et al., Reference Otamendi-Irizar, Grijalba, Arias, Pennese and Hernández2022), and generating wider socio-economic benefits such as local job creation (Mey et al., Reference Mey, Diesendorf and MacGill2016).

Within the European context, energy communities are promoted under the clean energy directives, while renewable energy communities, addressed in the renewable energy directive II 2018/2001, focus solely on renewable energy; Citizen energy communities, governed by the Internal electricity market directive 2019/944, cover all electricity types, offering a broader scope (Sale et al., Reference Sale, Morch, Buonanno, Caliano, Somma and Papadimitriou2022). These entities emphasize democratic governance, shared ownership, and public acceptance of renewables, while also mobilizing private capital for energy transition (Caratù et al., Reference Caratù, Brescia, Pigliautile and Biancone2023). The scale of their impact is already notable: over 7,700 communities across Europe engage around 2 million people, contributing approximately 7% of installed national capacity and generating 6.3 GW of renewable power, with investments exceeding €2.6 billion (Tatti et al., Reference Tatti, Ferroni, Ferrando, Motta and Causone2023). As highlighted by the European Commission, such initiatives act as catalysts for deploying renewable technologies and integrating citizens into energy systems, fostering a sustainable and inclusive energy future.

The choice of Portugal as the case study is justified on both empirical and theoretical grounds. First, Portugal possesses substantial untapped potential in renewable energy production and has an active civil society mobilizing around citizens’ energy communities. Second, Portugal has been relatively late in implementing energy communities compared to other EU member states, meaning that the institutional and organizational models are still being shaped, leaving room for experimentation and innovation (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Scharnigg, Monteiro and Pacheco2025). Third, the recent transposition of EU directives into national legislation has created a window of opportunity for pilot projects and novel energy-sharing scenarios (Decree-Law No. 162/2019; Regulation No. 373/2021; Decree-Law No. 15/2022; Regulation No. 815/2023). These policy changes align with EU objectives while simultaneously highlighting the technical and regulatory challenges that remain to be addressed. This evolving legal and policy framework makes Portugal a highly relevant and timely setting in which to explore the drivers of citizen engagement in energy communities.

2.2. Motivations for energy community engagement

Norms, as customary rules of behaviour, endure through conformity, such as investing in renewable energy to align with peers. These norms are driven by individual motivations, encompassing both self-regarding and social/moral aspects (Broska, Reference Broska2021). The complexity of these motivations makes them challenging to delineate. Social and moral norms, including environmental concern and trust, can play a crucial role when fostering positive behaviour and community engagement (Kalkbrenner & Roosen, Reference Kalkbrenner and Roosen2016). This engagement becomes most effective when people are in close spatial proximity, enhancing motivation and promoting a shared identity within communities (Bauwens, Reference Bauwens2016).

The determinants of engagement in community energy projects are multifaceted, including attitudes, context, and personal capability. Dimensions of social capital can be regarded as one of the most important contributing factors to pro-environmental behaviours (Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Gillott, Waldron, Cameron, Tubelo, Shipman, Ebbs and Bradshaw-Smith2020). For community energy projects to succeed, robust participation, sufficient financial resources, and government support are essential (Karytsas & Theodoropoulou, Reference Karytsas and Theodoropoulou2022). People engage in volunteering and community energy projects for several reasons, including personal and collective benefits (Goedkoop et al., Reference Goedkoop, Sloot, Jans, Dijkstra, Flache and Steg2022). Motivations for participating in sustainable projects vary and may include economic, social, or personal considerations. Personal motivation, particularly environmental concern, leads individuals to adopt sustainable behaviours and engage in community activities (Sloot et al., Reference Sloot, Jans and Steg2018). Engagement in energy communities is influenced by financial, environmental, and communal motives. Community ownership, in particular, fosters pride and optimistic attitudes, establishing strong relationships within geographical contexts (Sloot et al., Reference Sloot, Jans and Steg2019). Moreover, social identity is a significant predictor of behavioural intentions (Bauwens & Devine-Wright, Reference Bauwens and Devine-Wright2018).

2.3. Hedonic-Motivation System Adoption Model (HMSAM)

The adoption of hedonic-motivation systems is gaining relevance in the global economy, distinguishing themselves from utilitarian-motivation systems by prioritizing pleasure over productivity. Contrasting utilitarian systems, which are driven by an explicitly derived need for tangible benefits and specific outcomes, hedonic systems are focused on creating a profound level of immersion centred around user experience (Lowry et al., Reference Lowry, Jenkins, Gaskin and Hammer2013). This difference underlines the varying objectives of these systems: The utilitarian systems aim at efficiency and effectiveness, while the hedonic systems are oriented toward the maximization of enjoyment and satisfaction. Hedonic-motivation systems are also related to the area of user-acceptance models by explaining the differences between pragmatic and hedonism-oriented information systems (Van Der Heijden, Reference Van Der Heijden2004). This distinction is evident through the emphasis on intrinsic motivation, characterized by perceived ease of use and joy, as opposed to extrinsic motivation, represented by perceived usefulness (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Xie and Chen2024). This difference is important because it underscores how users engage with systems based on their motivational drivers. To further delve into intrinsic motivation, the concept of cognitive absorption was introduced alongside perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness as key components of the flow state (Kim & Hall, Reference Kim and Hall2019). This state of deep involvement and focus is essential to understanding user behaviour in hedonic contexts, exemplified by replacing the concept of pleasure with cognitive absorption. Some substructures, like curiosity, joy, and control, are thus established. These variables strongly influence the perceived ease of use and behavioural intention to use such systems, providing a better understanding of user engagement (Lowry et al., Reference Lowry, Jenkins, Gaskin and Hammer2013).

The HMSAM was designed to enhance the comprehension of hedonic-motivation systems adoption. This model includes variables such as behavioural intention, perceived usefulness, control, curiosity, focused immersion, joy, perceived ease of use, and temporal dissociation (Palos-Sanchez et al., Reference Palos-Sanchez, Saura and Velicia-Martin2024). These factors are incorporated into the HMSAM, which provides a thorough framework to analyse user adoption and engagement with hedonic systems. Moreover, the HMSAM underscores the importance of intrinsic motivation, where perceived ease of use and joy are key indicators. Perceived usefulness serves as an indicator of extrinsic motivation, mediating the relationship between perceived ease of use and behaviour intention to use (Van Der Heijden, Reference Van Der Heijden2004). This model posits that users who are internally motivated experience higher levels of involvement and concentration, which are crucial for immersion in their activities (Guo & Poole, Reference Guo and Poole2009). The addition of perceived enjoyment and subjective well-being can provide a more comprehensive understanding of user experience and satisfaction (Kim & Hall, Reference Kim and Hall2019). By understanding the interplay between these factors, we can better appreciate how hedonic systems captivate and retain users, ultimately driving their adoption and continued use.

2.4. Empowerment theory

Empowerment theory tries to explain how individuals and communities take control and gain influence over their lives and environments (Perkins & Zimmerman, Reference Perkins and Zimmerman1995). This theory is not a static concept but a dynamic process that varies depending on the context in which it gets applied. It includes the combination of three primary components: intrapersonal, interactional, and behavioural. Intrapersonal empowerment implies personal influence over social and political systems; interactional empowerment focuses on effective engagement with one’s environment. Behavioural empowerment refers to the execution of actions that affect the social and political spheres (Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Israel, Schulz and Checkoway1992). When individuals gain more control, especially those who previously lacked access to resources, they can experience greater participation in democratic processes and have a heightened awareness towards their surroundings (Rappaport, Reference Rappaport1987). This path to empowerment encompasses both methods and results, indicating that people can become empowered by deliberate action. Major elements of this process include goal setting and attainment, striving for access to resources, understanding sociopolitical dynamics, and participating in organizational processes that enhance engagement (Perkins & Zimmerman, Reference Perkins and Zimmerman1995).

Citizen participation is essential to achieve an empowerment statement, and it involves an equal share of power and promoting individuals’ sense of self-determination and efficacy (Füller et al., Reference Füller, Mühlbacher, Matzler and Jawecki2009). This approach helps reduce feelings of powerlessness, leading people to take initiative and persistence in activities that are experienced as empowering. Consequently, there is a notable increase in motivation and participation, resulting in a community that is more proactive and involved (Conger and Kanungo, Reference Conger and Kanungo2024). Empowerment also explains why individuals engage in pro-environmental consumer behaviour, as the psychological empowerment acquired from such actions can become a force motivating future behaviour, as it goes on to leave the individual feeling capable and influential. This sense of competence and control drives them to address issues they care about, further empowering them through their actions and decisions (Hartmann et al., Reference Hartmann, Apaolaza and D'Souza2018). By breaking down the concept into four dimensions: competence, meaning, impact, and self-determination. Competence is the possession of the requisite skills to perform a behaviour effectively. Meaning is concerned with the personal significance attached to an activity. Impact denotes the stated effective and perceived results of an activity. Self-determination refers to the feeling of being responsible for the results of actions taken (Naranjo-Zolotov et al., Reference Naranjo-Zolotov, Oliveira and Casteleyn2019). In this way, empowerment is also about gaining power in specific areas, mainly through citizens’ influence, which is a precondition for meaningful participation in community life. Feeling proud of a community also makes the citizens feel empowered. Moreover, the feeling of empowerment is not only for citizen engagement subjects but also concerning themes of understanding technology acceptance. Technology has the potential for the empowerment of people as individuals and as communities, offering different ways in which to participate and exert influence (Neves, Oliveira, Sarker, et al., Reference Neves, Oliveira and Sarker2024b).

Thus, empowerment theory is then a wide-ranging framework that emphasizes the importance of participation and the dynamic progression of attaining empowerment and belongingness, influencing decision-making processes in communities and driving change. A chronological summary of various studies focused on empowerment presented in Appendix A.

3. Research model

The adoption of technology relies primarily on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use (Davis, Reference Davis1989), as they are critical determinants of effective technology utilization (Venkatesh et al., Reference Venkatesh, Morris, Davis and Davis2003). In the context of local energy communities, perceived ease of use reflects the mental effort involved in participating in such community activities, while perceived usefulness emphasizes the gain associated with improved performance and sustainability of the communities (Van Der Heijden, Reference Van Der Heijden2004). Energy community tools, such as sustainable technologies that are perceived as easier to use tend to consequently be more likely to accepted by users, playing therefore significant parts in user acceptance of technology in energy communities (Yao et al., Reference Yao, Guo, Liu and Zhang2024). Once these technologies are easy to use, users perceive them as more useful for achieving their goals, which encourages their participation and support (Meloni et al., Reference Meloni, Giubergia, Piras and Sottile2025). Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H1a: Perceived ease of use positively impacts perceived usefulness

A system's perceived ease of use can stimulate users’ curiosity in the energy community context (Lowry et al., Reference Lowry, Jenkins, Gaskin and Hammer2013). When systems or platforms are user-friendly, they spark individuals’ interest and motivate them to explore related topics in energy, such as renewable sources and energy conservation (Paneru et al., Reference Paneru, Tarigan and Toșa2025) and users feel more confident in managing and adapting their participation according to their desires (Tbaishat et al., Reference Tbaishat, Amoudi and Elfadel2025). This sense of control can lead to higher satisfaction and increased involvement in community activities (Mehdizadeh et al., Reference Mehdizadeh, Kroesen and Vos2025). While control and perceived ease of use as modelled separately in different prior studies, they influence technology adoption (Erekalo et al., Reference Erekalo, Gemtou, Kornelis, Pedersen, Christensen and Denver2025). There is a significant interaction between control and perceived ease of use. If one had control over the behaviour and perceived that it was going to be much easier to do, then we believe the indifference shouldn’t occur, as the individual probably makes a more positive assessment about the chance of obtaining the desired outcome (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Saridakis and Benson2018). Perceived ease of use increases individuals’ perceptions of control within an energy community (Palos-Sanchez et al., Reference Palos-Sanchez, Saura and Velicia-Martin2024).

Individuals who tend to explore new technologies, even without extensive prior knowledge, are inclined to form preliminary expectations that interacting with the technology will be intuitive and enjoyable (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hsieh and Hsu2011).

Perceived ease of use can enhance the experience of citizens within an energy community by making interactions more fun (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Xie and Chen2024). When individuals enjoy participating in energy initiatives, they are more likely to continue contributing to the community (Arango-Quiroga et al., Reference Arango-Quiroga, Kuhl and MacGoy2025). Pleasant experiences can also foster a sense of belonging and pride within the energy community (Vafaei-Zadeh et al., Reference Vafaei-Zadeh, Tsetsegtuya, Hanifah, Ramayah and Choo2025). Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H1b: Perceived ease of use positively impacts curiosity

H1c: Perceived ease of use positively impacts control

H1d: Perceived ease of use positively impacts joy

H1e: Perceived ease of use positively impacts empowerment

Perceived usefulness, being defined as a key perception of users when interacting with information systems (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Park and Wang2025), is described as a cognitive belief that an individual holds toward a system, which can rapidly influence the user’s attitude and subsequent usage behaviour (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Bagozzi and Warshaw1989), and also regarding the system’s capability to enhance performance and achieve desired outcomes (Palacios-Marqués et al., Reference Palacios-Marqués, Cortés-Grao and Lobato Carral2013). Therefore, in the context of energy communities, when individuals perceive these communities as valuable and beneficial, they are more likely to develop the intention to join and actively participate in them (Perez et al., Reference Perez, Prasetyo, Cahigas, Persada, Young and Nadlifatin2023). The community’s ability to provide tangible benefits, such as access to clean energy and enhanced community engagement, can influence this perception of usefulness (Chanda et al., Reference Chanda, Mohareb, Peters and Harty2025). The energy community’s perceived value and usefulness play a crucial role in shaping users’ intentions (Verma et al., Reference Verma, Bhattacharyya and Kumar2018). Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H2: Perceived usefulness positively impacts behaviour intention to use.

Curiosity is defined as an internally motivated form of information seeking (Kidd & Hayden, Reference Kidd and Hayden2015). While related constructs such as thrill-seeking reflect the pursuit of novel and intense experiences, curiosity specifically drives individuals to explore what others are doing and thinking (Sutton et al., Reference Sutton, Yang and Totino2025). It is a central component of human cognition, facilitating divergent thinking, innovative problem-solving, and the ability to navigate complex and uncertain challenges (Kashdan et al., Reference Kashdan, Goodman, Disabato, McKnight, Kelso and Naughton2020).

At the behavioural level, curiosity fosters heightened interest, sustained attention, and deeper engagement with new knowledge and experiences (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chang and Yang2025). Even in situations marked by uncertainty or potential risks, such as energy communities, curiosity functions as a strong motivator of continued participation and involvement (Antonio et al., Reference Antonio, Ong, Diaz, Cahigas and Gumasing2025). When individuals are curious about community activities, they are more likely to utilize available tools and facilities to satisfy that curiosity, which in turn fosters greater participation and collaboration (Lowry et al., Reference Lowry, Jenkins, Gaskin and Hammer2013). As interest deepens, individuals become more attentive and absorbed in the community experience, strengthening their connection to its goals (Lowry et al., Reference Lowry, Jenkins, Gaskin and Hammer2013). Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H3a: Curiosity positively impacts behaviour intention to use

H3b: Curiosity positively impacts immersion

Control is defined as an individual's self-perception of their capabilities and capacity to regulate actions necessary for performing a given behaviour (Marín Puchades et al., Reference Marín Puchades, Fassina, Fraboni, De Angelis, Prati, De Waard and Pietrantoni2018). When individuals perceive sufficient control over a situation, they are more willing to take risks and engage in activities that may be uncertain or demanding (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Xie, Ge and Qu2025). High perceived behavioural control is linked to stronger motivation and persistence, whereas low perceived control often results in reduced motivation and premature disengagement (Yzer, Reference Yzer2012).

Perceived control also enhances immersion, as individuals who believe they can influence their environment and community tend to demonstrate deeper engagement and sustained participation (Antonio et al., Reference Antonio, Ong, Diaz, Cahigas and Gumasing2025). When users perceive influence over their experiences, they are more likely to remain actively engaged and invested in decision-making (Lowry et al., Reference Lowry, Jenkins, Gaskin and Hammer2013). In the context of energy communities, this sense of control over energy use and related decisions increases individuals’ involvement and commitment to collective goals (Eunike et al., Reference Eunike, Silalahi, Phuong and Tedjakusuma2024). Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H4: Control positively impacts immersion

Incorporating joy into the design of engagement activities is essential to ensure that diverse audiences are intrinsically motivated and experience psychological rewards (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Chou and Liu2025). In the context of energy communities, this can be achieved by creating opportunities for community members to contribute to policy formation, thereby strengthening self-efficacy, or by fostering social engagement and shared experiences within identity groups (Fogg-Rogers et al., Reference Fogg-Rogers, Sardo, Csobod, Boushel, Laggan and Hayes2024). Since humans are inherently social beings, activities that encourage peer approval and reinforcement (Fogg-Rogers et al., Reference Fogg-Rogers, Hayes, Vanherle, Pápics, Chatterton, Barnes, Slingerland, Boushel, Laggan and Longhurst2021), as well as those that promote helping behaviours and contributions to society, are particularly effective in sustaining engagement. Therefore, joy is a distinct positive emotion that emerges when individuals perceive accomplishment or progress toward valued goals (Fredrickson & Levenson, Reference Fredrickson and Levenson1998). Experiencing joy enhances motivation, driving individuals to pursue goals with determination (Behnke et al., Reference Behnke, Kreibig, Kaczmarek, Assink and Gross2022). Beyond motivation, joy broadens awareness, deepens reflection, and strengthens information processing, thereby enriching cognitive engagement and decision-making (Janani & Vijayalakshmi, Reference Janani and Vijayalakshmi2025).

Citizens’ emotional responses to new initiatives often depend on their prior awareness; positive reactions are amplified when projects are perceived to deliver environmental improvements and tangible benefits for residents, reinforcing engagement with energy technologies (Huijts, Reference Huijts2018). In the context of energy communities, joy positively influences behavioural intentions to participate (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Xie and Chen2024). Positive emotions generated through community interactions increase members’ willingness to engage in future activities and contribute to collective success (Ye et al., Reference Ye, Yao and Li2022). Moreover, joyful experiences capture attention and foster immersion, enhancing feelings of belonging and commitment to the community (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Xie and Chen2024). Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H5a: Joy positively impacts behaviour intention to use

H5b: Joy positively impacts immersion.

The transformation of the global energy landscape has intensified attention on empowerment as a mechanism for advancing energy efficiency (Jing et al., Reference Jing, Li and Wang2025). Empowerment emerges through participatory practices such as public meetings, focus groups, citizen juries, and participatory budgeting, which create pathways for interaction between citizens and different levels of government in shaping public service delivery (Cardullo & Kitchin, Reference Cardullo and Kitchin2024). By strengthening perceptions of personal efficacy, empowerment enhances belief in the effectiveness of conservation efforts, motivating sustainable behaviour and narrowing the persistent attitude – behaviour gap (Chan & Tangri, Reference Chan and Tangri2025). In environmental contexts, it reduces barriers related to effort and decision-making, thereby fostering eco-friendly practices with wider social benefits (Truc, Reference Truc2024).

In energy communities, empowerment provides members with a sense of agency and autonomy, encouraging proactive engagement and sustained commitment to collective goals. This perception of influence nurtures immersion and strengthens bonds within the community (Neves, Oliveira, Sarker, et al., Reference Neves, Oliveira and Sarker2024b). Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H6a: Empowerment positively impacts behaviour intention to use

H6b: Empowerment positively impacts immersion

Empowerment becomes a mechanism for facilitating collective intelligence open to innovation while promoting knowledge, serving not only as a motivational construct but also as an affective social experience (Indrayanti et al., Reference Indrayanti, Ulfia and Hidayat2025). In this sense, empowerment may moderate the effect of joy on behaviour intention to use and immersion. In a condition where an individual is empowered, their experience of joy can have a more intense or more positive influence on their intentions to use certain behaviours or levels of immersion in activities related to the energy community. This combination can enhance overall engagement and commitment within the energy community. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H7a: Empowerment positively moderates the relationship between joy and behaviour intention to use

H7b: Empowerment positively moderates the relationship between joy and behaviour immersion

The research model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual model.

4. Methods

4.1. Measurement

The measurement items for the questionnaire, as shown in Appendix B, were based on those proposed without significant changes. The following constructs are based on perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, curiosity, joy, control, behaviour intention to use and immersion, as mentioned by Lowry et al. (Reference Lowry, Jenkins, Gaskin and Hammer2013); and competence, meaning, impact, and self-determination by Neves, Oliveira, Sarker, et al. (Reference Neves, Oliveira and Sarker2024b).

4.2. Data

An online questionnaire was developed in Qualtrics and distributed from the 8th to the 30th of March 2024 for data collection. The survey collected data solely from Portugal, as the study aimed to understand Portuguese citizens’ willingness to join energy communities. Participants were invited to answer the survey via email, personal messages, and other social network applications. In particular, the survey was disseminated online through social media groups and forums related to the topic of energy. The survey was therefore open to all interested individuals rather than restricted to participants in energy communities. Respondents were not necessarily members of energy communities but individuals with an interest in the topic, following the same sampling strategy of similar articles on the topic (Neves, Oliveira, Sarker, et al., Reference Neves, Oliveira and Sarker2024b) The distribution was broad to collect all the data within three weeks. A total of 307 responses were submitted and validated. The adequacy of the sample size for SEM follows the 10-times rule. The 10-times rule suggests that the minimum sample size should exceed 10 times the maximum number of structural paths pointing at a latent variable in the model (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Ringle and Sarstedt2011). The sample satisfies this requirement, and it is supported by similar studies (Coelho et al., Reference Coelho, Oliveira, Neves and Karatzas2024; Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Oliveira and Neves2023; Mateus et al., Reference Mateus, Oliveira and Neves2023). The questions were measured on a seven-point numerical scale: (1-completely disagree; 7-completely agree), with only the endpoints labelled, and without a “don´t know/prefer not to answer” option, following the scales used in the studies from which the constructs were sourced and adapted. Nevertheless, respondents could withdraw from the survey at any time, ensuring that no one was forced to answer. Only fully completed questionnaires were considered valid, and since all questions were mandatory, the dataset does not contain missing values. The questionnaire was written in English first, and then it was translated into Portuguese in order to allow the participants to respond more easily (Cha et al., Reference Cha, Kim and Erlen2007). It was translated back to English to ensure that all questions had equivalent meanings. A pilot test with 30 responses indicated that the items were adequately measuring the constructs. Two distinct methods were used to evaluate the possibility of common-method bias. According to the results of Harman's single-factor test (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003), each factor contributed less than 50% of the variation, meaning that no single factor could account for the majority of the variance. Additionally, the survey’s ostensibly immaterial marker variable resulted in a minimal maximum shared variance of just 2.8%, a value that (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Rosen and Djurdjevic2011) found trivial, indicating the absence of common-method bias.

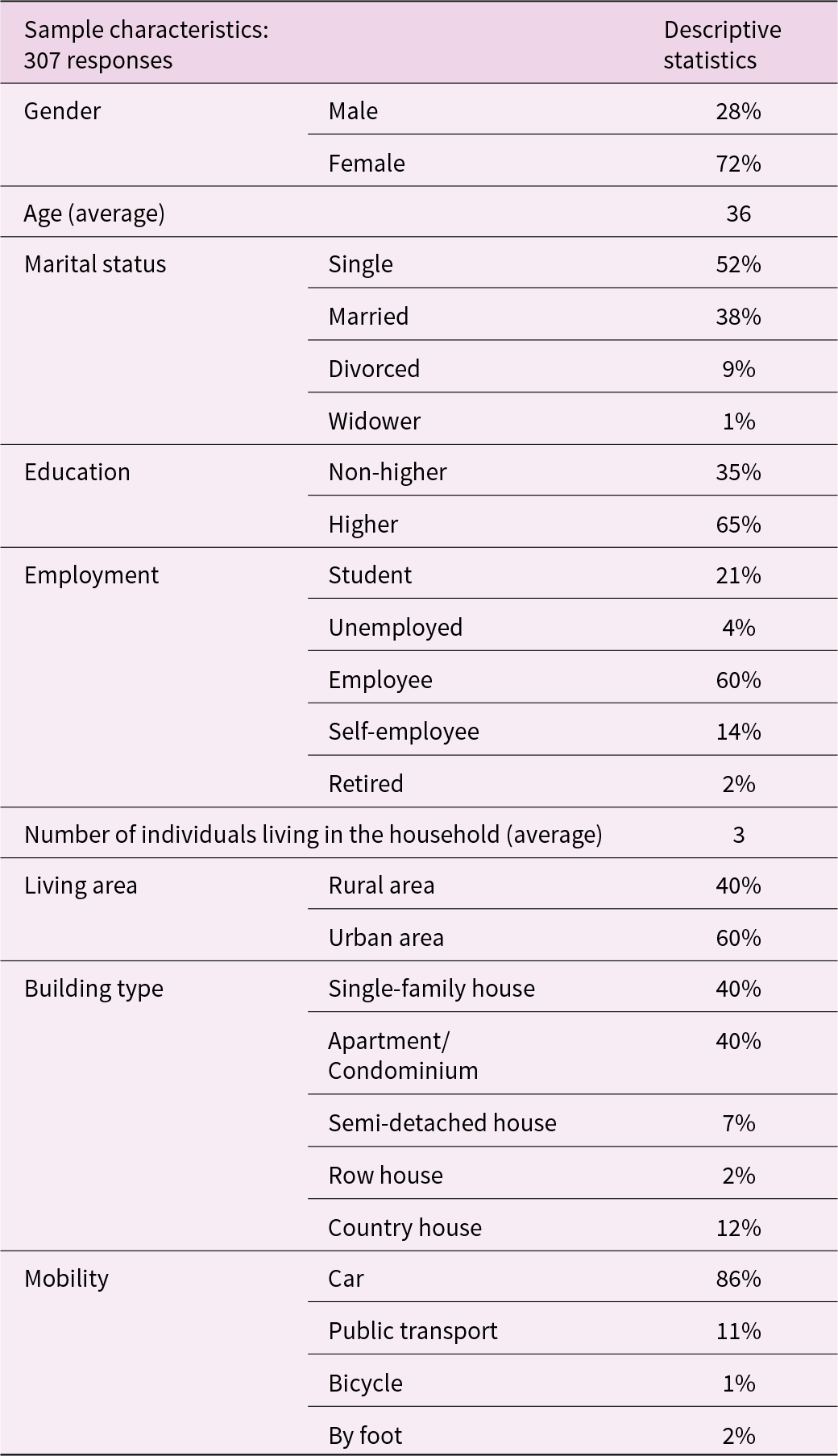

As seen in Table 1, regarding sample characteristics, 28% of respondents were male, and 72% were female. The average age of the respondents was 36 years, and most were single. Regarding education, 65% of the participants hold a higher education degree, while 35% do not. Moreover, over half of the participants worked. The average number of persons in a family was three, and 60% lived in urban areas, while 40% lived in rural areas, mostly in single-family homes or apartments. Most responders had cars.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

4.3. Demographic variables

Research on consumer behaviour commonly incorporates control variables, particularly socio-demographic characteristics (Davis, Reference Davis2010; Erell et al., Reference Erell, Portnov and Assif2018; Neves, Oliveira, Karatzas, et al., Reference Neves, Oliveira and Karatzas2024a; Yang & Zhao, Reference Yang and Zhao2015). In this study, age, gender, education, and living area were included as demographic variables to account for their potential influence and to ensure the robustness of the estimated effects of the explanatory variables. All control variables were treated as categorical, except for age. Specifically, gender was coded as 0 = female and 1 = male; education as 0 = non-higher education and 1 = higher education; and living area as 0 = rural and 1 = urban.

5. Data analysis and results

With the help of SmartPLS4, the partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) technique was used to estimate the research model. This method is appropriate for testing research models that have not been previously examined. Additionally, PLS does not require strong assumptions about the distribution of data, making it a suitable method (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Ringle and Sarstedt2011).

5.1. Measurement model

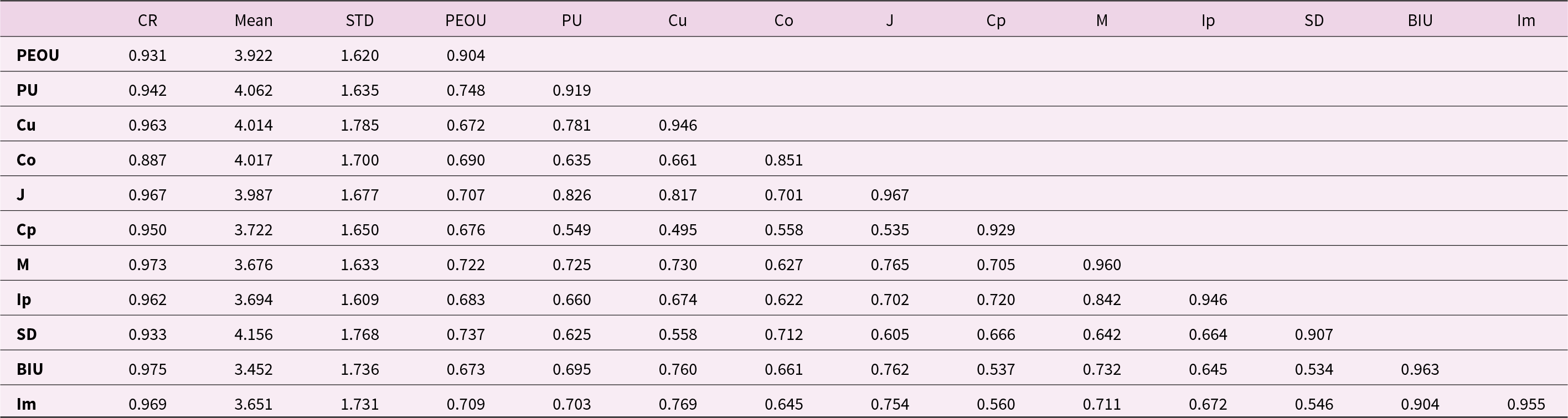

A set of analyses were made to assess the measurement model. The composite reliability (CR), the mean and standard deviation (STD) of the reflective constructs were calculated as shown in Table 2. All the constructs observe a CR higher than 0.7, indicating satisfactory internal consistency and reliability of the measurement instruments. To assess the discriminant validity, the Fornell–Larcker criterion was used to determine whether the square root of each construct’s average variance extracted (AVE) was higher than its highest correlation with any other construct (Fornell and Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). When evaluating the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) (Appendix C), it was confirmed that all diagonal values were lower than 0.9, except for the BIU with Im. With a 97.5% confidence interval, the value stayed below 1. As shown in Appendix D, the loadings and cross-loadings on the associated construct were greater than all of its loadings on other constructs.

Table 2. CR, mean, STD, and Fornell–Larcker table

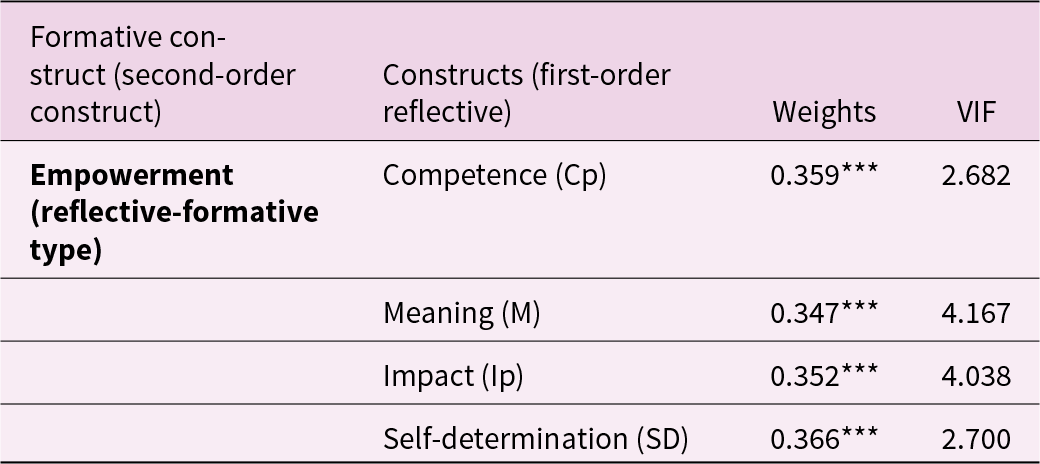

Table 3 verifies the multicollinearity and relevance of the evaluated indicator weights for the reflective-formative constructs. Variance inflation factor (VIF) scores were lower than 5, indicating no issues with multicollinearity (Hair et al., 2022).

Table 3. Formative measurement model evaluation (*p-value<0.1; **p-value<0.05; ***p-value<0.01)

5.2. Structural model

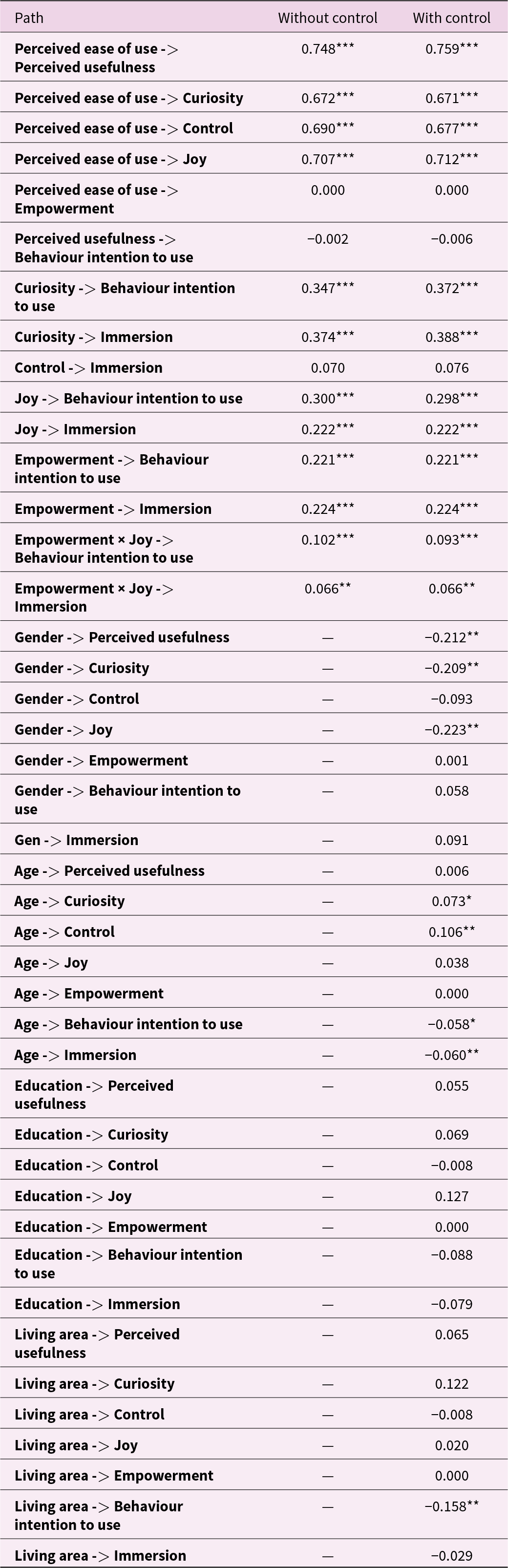

When examining the structural model, the path coefficients were revealed through bootstrapping with 5000 iterations of resampling. To further ensure the robustness of these findings, Table 4 reports the results with and without demographic variables. Comparing the two models reveals that, although some control variables have significant effects, the main hypothesized paths remain largely unchanged in terms of both significance and coefficient values. At the same time, demographic variables revealed additional effects: gender was negatively associated with perceived usefulness, curiosity, control, and joy; age was positively associated with curiosity and control but negatively associated with behavioural intention and immersion; education showed small positive effects on curiosity and joy; and finally, living area was negatively associated with behavioural intention to participate.

Table 4. Main paths without and with demographic variables (*p-value<0.1; **p-value<0.05; ***p-value<0.01)

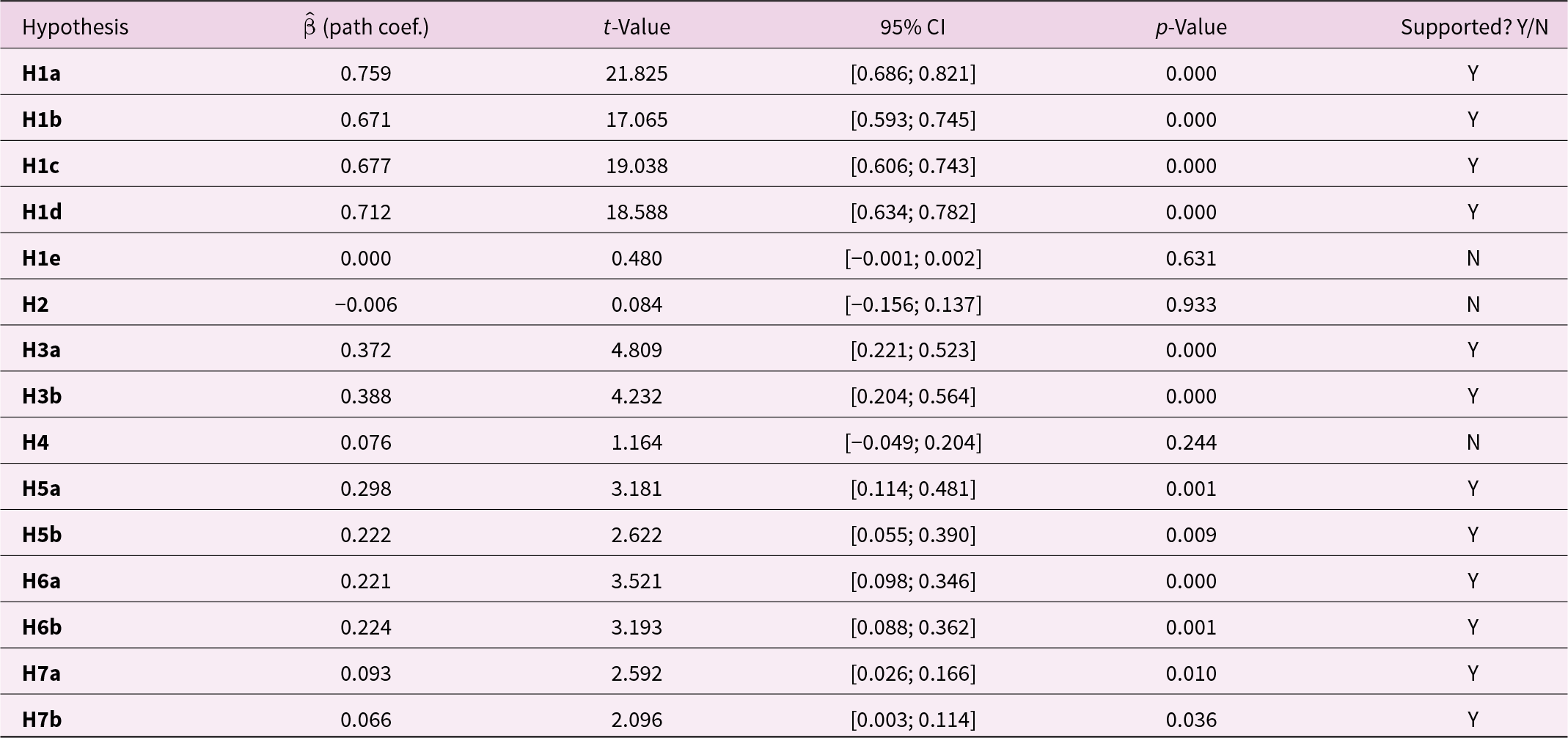

The model explains 67.5% of the variation of the behaviour intention to participate, and 67.2% by the immersion in energy communities, as shown in Figure 2. All the hypotheses were confirmed, except H1e (β̂ = 0.000, p > 0.1), H2 (β̂ = −0.006; p > 0.1), and H4 (β̂ = 0.076; p > 0.1), because their p-values are not statistically significant, then H1a (β̂ = 0.759, p < 0.01), H1b (β̂ = 0.671, p < 0.01), H1c (β̂ = 0.677, p < 0.01), H1d (β̂ = 0.712, p < 0.01), H3a (β̂ = 0.372, p < 0.01), H3b (β̂ = 0.388, p < 0.01), H5a (β̂ = 0.298, p < 0.01), H5b (β̂ = 0.222, p < 0.01), H6a (β̂ = 0.221, p < 0.01), H6b (β̂ = 0.224, p < 0.01), H7a (β̂ = 0.093, p < 0.01), and H7b (β̂ = 0.066, p < 0.05), complete what was previously known to participate in energy communities and engage in their activities as it is summarizes in Table 5 with the hypothesis results, revealing the path coefficients, t-values, 95% CIs, p-values, and support status.

Figure 2. Structural model (***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1).

Table 5. Hypothesis results

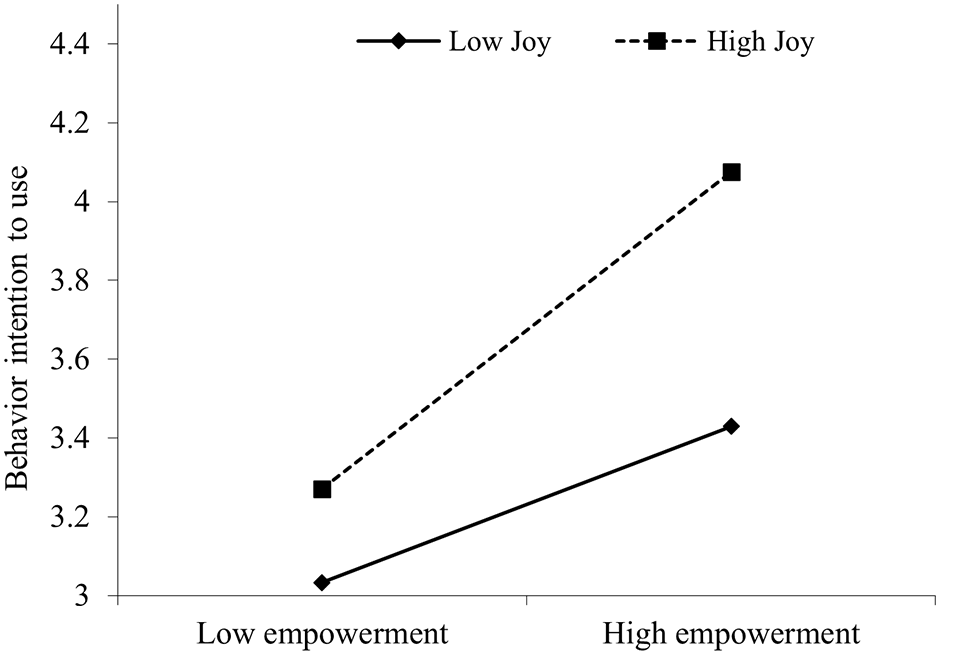

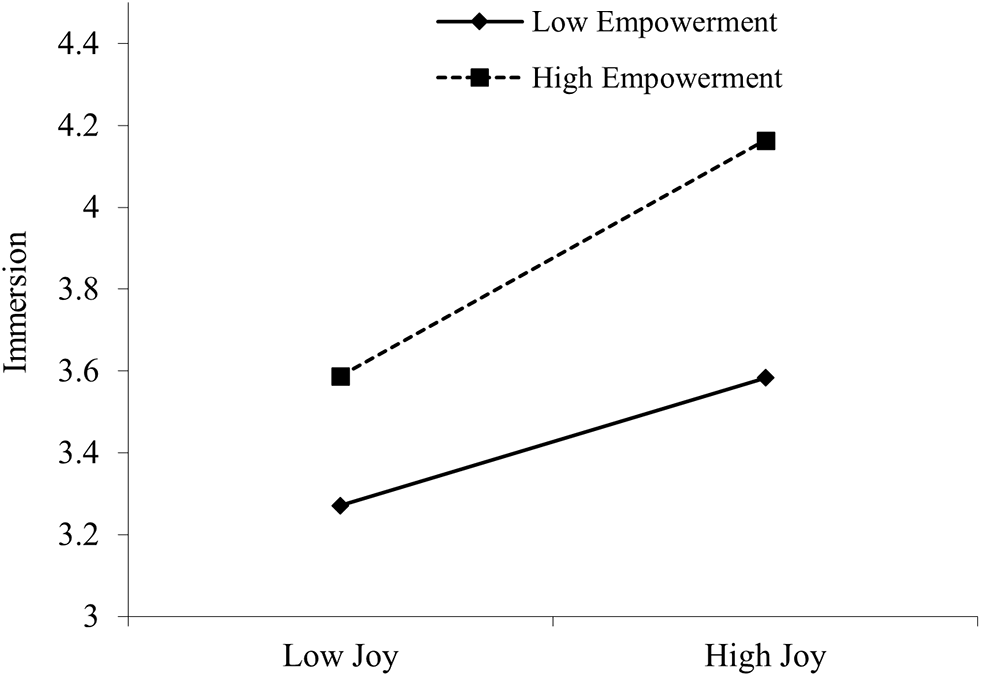

5.3. Moderator role of empowerment

The data support the hypothesis, also showing that empowerment plays a moderating effect in the relationship between joy and behaviour intention to use, H7a (β = 0.093, p < 0.01), or even joy and immersion H7b (β = 0.066, p < 0.05). Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the impact of empowerment on behaviour intention, use, and immersion, respectively. Joy has minimum impact on the behaviour intention to use or immersion for people with low levels of empowerment. On the other hand, when an individual feels empowered, joy has a stronger influence on their purpose to utilize and immerse in the energy community.

Figure 3. Moderator effect on behaviour intention to use.

Figure 4. Moderator effect on immersion.

6. Discussion

The purpose of this research is to identify the factors impacting engagement in energy communities and related activities. For this purpose, a model was developed joining the hedonic-motivation system adoption model and the empowerment theory. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that energy communities’ engagement is analysed under this perspective, focusing on the role of positive emotions, such as hedonic motivations and empowerment, rather than the usual utilitarian ones.

The results confirm that hedonic motivations such as joy and curiosity, along with empowerment, remain central, while demographic factors indicate potential barriers. The results indicate that women show greater emotional connection and perceive more value in participating in energy communities, aligning with prior findings that women often express higher environmental concern and community orientation (Subiza-Pérez et al., Reference Subiza-Pérez, Santa Marina, Irizar, Gallastegi, Anabitarte, Urbieta, Babarro, Molinuevo, Vozmediano and Ibarluzea2020). Age appears to play a dual role: older respondents show greater curiosity and control but lower intention and immersion, possibly due to perceived complexity or lower long-term incentives. For education, the slight positive leanings toward curiosity and joy indicate that individuals with higher education levels tend to exhibit slightly higher intrinsic interest and positive emotions toward energy community engagement.

It is also important to consider the socio-territorial context in which energy communities emerge. Rural areas in Portugal, which produce substantial renewable energy from solar, wind, and hydropower, offer opportunities to develop local energy communities that boost sustainability and empower citizens (Dijkstra & Theise, Reference Dijkstra and Theise2025). Despite regional differences, the analysis reveals an urban–rural gap, showing that urban residents are more likely to express willingness to join and participate in energy communities. This could be attributed to greater exposure to sustainability campaigns, higher social visibility of collective projects, and more accessible institutional support in urban areas. In opposition, rural participants may face organizational or informational barriers despite their proximity to renewable resources, reflecting a missed opportunity for local empowerment and community-based energy transition.

In the end, the main model relationships remain robust even after including these control variables, confirming the validity of our findings.

6.1. Theoretical implications

The theoretical contribution of this study to the literature on energy communities is manifold. First, it advances understanding of the motivators for citizen participation by adopting a citizen-centred perspective, rather than the institutional or operational focus that dominates previous research (Neves, Oliveira, Sarker, et al., Reference Neves, Oliveira and Sarker2024b). By combining the hedonic-motivation system adoption model (HMSAM) with the empowerment theory, the study highlights how positive emotions and feelings of empowerment are decisive drivers of engagement. This approach contrasts with earlier studies that primarily examined the stimulus of technology as a driver of pro-environmental behaviour, under the SOR (stimulus-organism-response) framework or the potential role of gamification features (Neves, Oliveira, Sarker, et al., Reference Neves, Oliveira and Sarker2024b).

Second, our findings support and extend the importance of emotional and social dimensions in shaping sustainable behaviours. Results show that joy leads to more meaningful environmental experiences, while environmental awareness and community-relatedness contribute to long-term sustainable habits. This resonates with prior studies drawing on the theory of planned behaviour (TPB), where factors such as trust, altruism, and personal characteristics have been identified as key factors of participation (Neves, Oliveira, and Santini, Reference Neves, Oliveira and Santini2024). However, our model provides a more integrated explanation by showing how hedonic motivations and empowerment jointly influence behaviour, going beyond utilitarian or normative determinants.

Third, this complements research based on social identity and pro-environmental behaviour theories, where community commitment, trust, and knowledge were highlighted as substantial predictors of participation (Neves, Oliveira, and Karatzas, Reference Neves, Oliveira and Karatzas2025). Our findings expand these insights by demonstrating that empowerment acts not only as a contextual factor but as a moderator that interacts with hedonic motivations to shape participation.

Altogether, the study extends the scope of the HMSAM into the domain of energy communities, where its applicability is beyond traditional areas of social networks, virtual communities or gamification processes (Perez et al., Reference Perez, Prasetyo, Cahigas, Persada, Young and Nadlifatin2023), complements and connects with theories such as TAM (Lowry et al., Reference Lowry, Jenkins, Gaskin and Hammer2013), TPB, SOR, and social identity theory. By emphasizing hedonic and empowerment-based motivations, it provides a more nuanced understanding of why citizens join and remain engaged in energy communities, thus reinforcing the value of integrating technology adoption and behavioural theories in this emerging field.

6.2. Managerial/practical implications

The need to take into consideration citizens’ views and involve them in the production of concrete actions with long-term measures inside the energy community is critical to the support of effective outcomes in energy communities. Applying this approach increases community involvement in more connected and sustainable topics and brings a feeling of empowerment (Hyytinen & Toivonen, Reference Hyytinen and Toivonen2015). In this respect, local governments should establish specific points for public feedback and offer incentives or resources easily understandable for sustainable projects (Mey et al., Reference Mey, Diesendorf and MacGill2016). According to the model, it has been shown that empowerment has a major positive impact on community engagement. To maximize this effect, strategies should focus on the four basic elements of empowerment, by offering concise details regarding the advantages, resulting in the involvement of energy communities, which can enhance general empowerment and stimulate increased degrees of engagement. This approach aimed to help create a sense of ownership and belonging within energy communities, potentially leading to more sustainable and impactful outcomes. Some advisory groups or committees could be created with a varied representation of the community or knowledgeable people could organize informational workshops, and institute open decision-making procedures that might be taken as an example of initial steps (Lennon et al., Reference Lennon, Dunphy and Sanvicente2019). To further improve individuals’ competency and involvement in energy projects, local governments might provide training programs, technical assistance, and financial incentives. Local governments can foster an atmosphere that drives and maintains active citizen participation in energy programs by anticipating probable obstacles and using successful case studies as models (Manhique et al., Reference Manhique, Kouta, Barchiesi, O'Regan and Silva2021).

6.3. Limitations and future research

First, the quantitative study focused only on people living in Portugal and did not give way to the general perspective of citizens and their attitudes aimed at participation in energy communities in other regions. Second, the sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Although the study's model and the selection of variables were justified, it may not encompass all possible perspectives of citizen behaviour. Future research should explore other variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of citizen perspectives and could also benefit from a broader and more targeted sampling strategy that distinguishes between participants and non-participants in energy communities and compares their responses. Expanding the study to include comparisons between different countries could offer valuable insights into regional variations in attitudes and behaviours towards energy communities. Conducting targeted interviews to delve into specific aspects of citizen interests could also enrich the data and offer more nuanced insights.

7. Conclusion

This research study highlights the findings of motivations about energy communities through the combination of the HMSAM with an empowerment perspective. It reveals that joy leads to more meaningful experiences related to the environment itself, fostering their interest in such activities. In this sense, community engagement heightens citizens’ sense of expertise and purpose, reinforcing their feeling of empowerment and ability to contribute positively to society. Besides that, both environmental awareness and community relatedness within citizens raise long-term sustainable habits. Once we can understand what people are motivated by, targeted strategies can drive practitioners to create more inclusive energy communities. Such interventions are going to frame the energy landscape, promote greener practices, and empower people to be more conscious. The findings can offer relevant thoughts to the binding of citizens within communities and shaping the way forward into the future, with a view toward maximizing the positive impact that energy communities can achieve at larger scales.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by national funds through FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia), under the project – UIDB/04152 – Centro de Investigação em Gestão de Informação (MagIC)/NOVA IMS.

Author Contributions

Dadid Moniz: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Tiago Oliveira: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Conceptualization. Catarina Neves: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Financial Support

This work was supported by national funds through FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia), under the project – UIDB/04152 – Centro de Investigação em Gestão de Informação (MagIC)/NOVA IMS.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability

Data will be made available upon request.

Appendix A – Studies on empowerment

Appendix B – Instrument table

Appendix C — Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)

Appendix D – Loadings and Cross-Loadings