Introduction

Several European countries were severely hit by floods in the summer of 2021. Belgium and Germany were particularly affected by these disastrous events, having seen 41 and 183 people, respectively, who died in the floods. Politicians quickly connected this disaster to global warming: the German Interior Minister back then, Horst Seehofer, stated on 16 July, 2021, that ‘nobody can deny that this catastrophe is linked to climate change’.Footnote 1 The former German chancellor, Angela Merkel, echoed this view on 18 July when she travelled to the Ahr valley in Rhineland‐Palatinate, one of the most affected areas.Footnote 2 The media as well as the scientific community also covered the floods swiftly and extensively, thus ensuring broad reporting of the events across Europe and the world, while highlighting that global climate change can be associated with the onset and severity of natural disasters. The British Guardian, for instance, wrote about the views of a number of climate scientistsFootnote 3 before publishing a story on 19 July that suggested a ‘global green deal to tackle climate crisis’ must quickly be agreed on.Footnote 4 Greek media called the floods of 2021 a ‘national catastrophe,’Footnote 5 an Italian newspaper wrote about a ‘climate massacre’, French media focused on the consequences of climate change, and the floods were covered in Spain, Russia, the United States and even in Australia.Footnote 6

The question we ask considering these events is whether the floods in one country affect public opinion in another state. More generally, do natural disasters have a transnational influence on environmental attitudes abroad? Following the dataset we rely on empirically, we define natural disasters as a ‘situation or event, which overwhelms local capacity, necessitating a request to national or international level for external assistance’. Such an unforeseen and often sudden event, caused by nature, frequently causes great damage, destruction and human suffering.Footnote 7 Environmental disasters have become more numerous, as climate change and global warming exacerbate (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2019; see also Fischer & Knutti, Reference Fischer and Knutti2016). Public opinion and political leaders, even in countries that have not been directly affected by (severe) disasters, may connect these events more and more to climate change (see also Bergquist et al., Reference Bergquist, Nilsson and Schultz2019; Demski et al., Reference Demski, Capstick, Pidgeon, Sposato and Spence2017; Smith & Joffe, Reference Smith and Joffe2013; Weber, Reference Weber2010). And we know that public opinion positively correlates with policy outputs (e.g., Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Böhmelt and Ward2018; Bakaki et al., Reference Bakaki, Böhmelt and Ward2020; Boswell et al., Reference Boswell, Corbett, Dommett, Jennings, Flinders, Rhodes and Wood2019; Schaffer et al., Reference Schaffer, Oehl and Bernauer2022). Thus, although politicians are those who ultimately make policy decisions, the public matters greatly as citizens’ concerns can shape governments’ environmental legislative actions. Having said that, are natural disasters abroad among the influences behind public opinion on the environment?

We test the theoretical expectations underlying this question with survey data from the Eurobarometer in 2002–2020 and information from the International Disaster Database (IDD) by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED).Footnote 8 The empirical results stress that there is robust support for a transnational diffusion effect: disasters abroad shape environmental attitudes at home. Eventually, our findings make several contributions to the literatures on environmental politics, public opinion, natural disasters and diffusion effects. For example, one implication of our work is that natural disasters cannot be treated as isolated incidents within state borders, but they have far‐reaching, transnational consequences on people's views and, potentially, policy. Hence, we depart from previous research in that we explore the transnational impact of natural disasters on the formation of public opinion.

This diffusion mechanism has rarely been acknowledged in the literature on environmental disasters, public opinion and environmental politics, possibly due to the emphasis on people's direct exposure and thus, experience with natural catastrophes. Böhmelt (Reference Böhmelt2020) is, to some degree, an exception here as he studies the impact of the Fukushima disaster on European public opinion. Yet, that article focuses on a rather major event of substantial magnitude, while the ‘average’ disaster is of lesser impact. What is more, Fukushima was at best partially a natural disaster and the net impact of environmental events on public opinion cannot be identified by studying single cases.

Finally, we help to better understand the formation of environmental public opinion also with a view toward policymaking as people's views influence legislative action (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Böhmelt and Ward2018; Bakaki et al., Reference Bakaki, Böhmelt and Ward2020; Ray et al., Reference Ray, Hughes, Konisky and Kaylor2017; Schaffer et al., Reference Schaffer, Oehl and Bernauer2022). As concluded in Bakaki and Bernauer (Reference Bakaki and Bernauer2017b: 1), this ‘implies that public opinion sets important constraints on what policymakers can achieve’.

Public opinion and the environment

An extensive literature focuses on what people think about the environment, and how attitudes toward environmental protection and salience are shaped (for recent overviews, see, Bakaki & Bernauer, Reference Bakaki and Bernauer2017a, Reference Bakaki and Bernauer2017b; Bernauer & McGrath, Reference Bernauer and McGrath2016; Hornsey et al., Reference Hornsey, Harris, Bain and Fielding2016; Howe et al., Reference Howe, Marlon, Mildenberger and Shield2019; Marquart‐Pyatt et al., Reference Marquart‐Pyatt, McCright, Dietz and Dunlap2014). Among others, individual political views, economic factors or – especially relevant for our research – natural disasters can all influence how people see the environment (Halder et al., Reference Halder, Hansen, Kangas and Laukkanen2020; Scott & Willits, Reference Scott and Willits1994). Wildfires in Australia, Greece and Turkey, hurricanes in the United States (Bergquist et al., Reference Bergquist, Nilsson and Schultz2019; Rudman et al., Reference Rudman, McLean and Bunzl2013), droughts in African states (Borick & Rabe, Reference Borick and Rabe2010; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Conover, Videras and Wu2012) or the severe floods in European countries of 2021 are just a few examples of natural disasters that have occurred over the recent past. Such environmental events affect people in numerous ways, including psychologically (Schultz et al., Reference Schultz, Gouveia, Cameron, Tankha, Schmuck and Franek2005), thus potentially influencing their preferences, perceptions and behaviour.

Particularly the personal (local) experiences with natural disasters can be a focal point that forms environmental views (e.g., Akerlof et al., Reference Akerlof, Maibach, Fitzgerald, Cedeno and Neuman2013; Baccini & Leemann, Reference Baccini and Leemann2020; Bergquist et al., Reference Bergquist, Nilsson and Schultz2019; Brody et al., Reference Brody, Zahran, Vedlitz and Grover2008; Howe et al., Reference Howe, Boudet, Leiserowitz and Maibach2014; Konisky et al., Reference Konisky, Hughes and Kaylor2016; Li et al., Reference Li, Johnson and Zaval2011; Marlon et al., Reference Marlon, Bloodhart, Ballew, Rolfe‐Redding, Roser‐Renouf, Leiserowitz and Maibach2019; Reser et al., Reference Reser, Bradley and Ellul2014; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Whittle, Medd and Walker2011; Whitmarsh, Reference Whitmarsh2008). Lang and Ryder (Reference Lang and Ryder2016) show that there is an ‘experience‐perception link’: having lived through and directly experienced an environmental disaster shapes people's understanding of climate change, who then link also extreme weather events more strongly to global warming (see also Bergquist et al., Reference Bergquist, Nilsson and Schultz2019; Demski et al., Reference Demski, Capstick, Pidgeon, Sposato and Spence2017; Smith & Joffe, Reference Smith and Joffe2013). Similarly, Konisky et al. (Reference Konisky, Hughes and Kaylor2016) report that extreme weather events influence whether environmental issues are seen as salient or not. In addition, personal experience of environmental events leads to more pro‐environmental donations (Li et al., Reference Li, Johnson and Zaval2011), increased support of environmental‐friendly policies (Joireman et al., Reference Joireman, Barnes Truelove and Duell2010; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Conover, Videras and Wu2012; Rudman et al., Reference Rudman, McLean and Bunzl2013), pro‐environmental voting (Herrnstadt & Muehlegger, Reference Herrnstadt and Muehlegger2014) or the punishment of incumbent governments (Stokes, Reference Stokes2016).

When referring to personal experience, we talk about the more local effects witnessed by people and their proximity to an event – and not necessarily that individuals were directly hurt or have suffered from an environmental disaster. That said, the general underlying mechanism of those relationships above, posits that the direct (personal) experience with an extreme environmental event induces the perception of climate change as ‘more real, immediate, and local’ (Carlton et al., Reference Carlton, Mase, Knutson, Lemos, Haigh, Todey and Prokopy2016, p. 212; see also Bergquist et al., Reference Bergquist, Nilsson and Schultz2019; Leiserowitz, Reference Leiserowitz2006; Myers et al., Reference Myers, Nisbet, Maibach and Leiserowitz2012). Personal experience lowers ‘psychological distancing’ (Egan & Mullin, Reference Egan and Mullin2012; Ray et al., Reference Ray, Hughes, Konisky and Kaylor2017; Spence et al., Reference Spence, Poortinga, Butler and Pidgeon2011; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Dessai and Bruin2014). Lujala et al. (Reference Lujala, Lein and Rød2015, p. 490) state consistently that ‘[a] person's perception of climate change may thus be partially formed by her proximity to “danger”, for example, through personal experience of an event or by living near or in a hazard‐prone area’. And, indeed, Whitmarsh (Reference Whitmarsh2008) claims that extreme weather events’ effects on environmental perceptions are limited to the area where they occur and that, in these places, increased recognition of and concern over climate change are induced. Most existing evidence then suggests that natural disasters are positively associated with environmental concerns if these events are extreme and affect people directly, that is, occurred in close proximity (e.g., Bergquist et al., Reference Bergquist, Nilsson and Schultz2019; Demski et al., Reference Demski, Capstick, Pidgeon, Sposato and Spence2017; Lu & Schuldt, Reference Lu and Schuldt2015, Reference Lu and Schuldt2016; Reser et al., Reference Reser, Bradley and Ellul2014; but, e.g., Brulle et al., Reference Brulle, Carmichael and Jenkins2012; Carlton et al., Reference Carlton, Mase, Knutson, Lemos, Haigh, Todey and Prokopy2016; Marquart‐Pyatt et al., Reference Marquart‐Pyatt, McCright, Dietz and Dunlap2014).

Yet, natural disasters are not confined to state borders and can quickly spread across regions.Footnote 9 Therefore, in addition to the local effect identified by previous research, we argue for a transnational‐level influence, beyond domestic boundaries. Our argument is based on two interrelated mechanisms that pertain to the flow of information across borders as a necessary requirement for diffusion to emerge and for people's processing of information on events in nearby states. That is, natural disasters in nearby countries prompt individuals to believe they could also be directly affected by such incidents in the future. Moreover, local media must report on those events in the first place to ensure that information reaches individuals, and those media outlets are more likely to cover disasters in geographically proximate and neighbouring countries as opposed to more distant states. Both mechanisms imply that people will be more aware of environmental disasters in proximate countries and will be more likely to develop feelings of fear, distress and uncertainty due to these events. Public opinion on the environment is likely to be affected as a result, even if a disaster occurred in another, albeit nearby country.

Theoretical argument

Natural disasters can influence environmental public opinion, especially if these events have occurred and are more extreme, and also, if people have experienced them in close proximity (e.g., Bergquist et al., Reference Bergquist, Nilsson and Schultz2019; Demski et al., Reference Demski, Capstick, Pidgeon, Sposato and Spence2017; Lu & Schuldt, Reference Lu and Schuldt2015, Reference Lu and Schuldt2016; Reser et al., Reference Reser, Bradley and Ellul2014). This finding, and its underlying mechanisms, constitute the starting point for our argument, which focuses on the transnational effect of natural disasters on environmental public opinion, that is, at the cross‐border level. We contend that more natural disasters can form people's views on the environment not only ‘at home’, that is, the country where a disaster occurred, but also in geographically close states.

We develop the theory in two steps. On one hand, while the media of course cover events abroad, thus increasing the chances that people obtain information on environmental disasters in other countries, they tend to focus on nearby countries. More distant, remote events are less likely to be reported on. On the other hand, individuals process this information and develop disaster‐threat perceptions that feed feelings of danger, uncertainty, and distress that eventually translate into concerns about the environment. We claim that such a psychological dynamic does not only apply to disasters within a country's borders, but also in terms of nearby states.

We thus concentrate on an influence stemming from natural disasters that spans across borders, and the key factor behind the two mechanisms is spatial proximity, which ensures media coverage, increases the chances that people are exposed to it, and raises the likelihood that they develop feelings of danger, distress, or uncertainty. Consistent with this idea, Howe et al. (Reference Howe, Boudet, Leiserowitz and Maibach2014) argue for a ‘shadow of experience’ when explaining the risk perception of weather events (see also Weber, Reference Weber2006, Reference Weber2010). Natural disasters exercise an indirect effect via broad media coverage, which in turn affects people who may feel that they have experienced these events even if they live further away. Additionally, seeing these events in such proximity aggravates the belief that they could experience them directly in the near future (Blennow et al., Reference Blennow, Persson, Tomé and Hanewinkel2012).

Media coverage of disasters in geographically proximate countries

A key requirement for an influence of an environmental disaster abroad on public opinion at home, is that information about the event actually reaches citizens. In other words, the media have to cover a disaster in another country, and, to this end, they play a pivotal role in shaping the perceptions of individuals (Dewenter et al., Reference Dewenter, Linder and Thomas2019). The media have the capacity to generate awareness and knowledge about climatic events (Barabas & Jerit, Reference Barabas and Jerit2009), often creating public awareness of environmental issues in the first place (Bakaki et al., Reference Bakaki, Böhmelt and Ward2020; Barnes & Hicks, Reference Barnes and Hicks2018; Oehl et al., Reference Oehl, Schaffer and Bernauer2017), which stimulates people's overall understanding about climate change (Dolan et al., Reference Dolan, Hallsworth, Halpern, King, Metcalfe and Vlaev2012; Grundmann, Reference Grundmann2007; Staats et al., Reference Staats, Wit and Midden1996). The media can be selective on what they present (Boykoff & Roberts, Reference Boykoff and Roberts2007) and they have the power to set the agenda (Dumitrescu & Mughan, Reference Dumitrescu, Mughan, Leicht and Craig Jenkins2010; McCombs, Reference McCombs2004). By steering the extent and prominence of coverage, they affect public opinion.

The transnational effect of the media implies that crucial events with national impact in one country are covered in another state, and primarily a neighbouring one (Brüggemann & Engesser, Reference Brüggemann and Engesser2017). The frequency and prominence of a story in media coverage conveys a message to the public about the importance of an issue (Brulle et al., Reference Brulle, Carmichael and Jenkins2012). Additionally, the media propagation of news and symbols of environmental catastrophes carries emotional weight (Birkland, Reference Birkland1998), which creates feelings of fear, distress, and uncertainty. Koopmans and Vliegenthart (Reference Koopmans and Vliegenthart2011) examine the media coverage of natural disasters across countries and find that strong ties between states as well as certain event‐related characteristics, most prominently the number of deaths caused by an event, raises the chances that a disaster abroad is thoroughly covered by the media at home.

That said, while the media do cover environmental issues abroad, such as global environmental conferences and summits, especially disasters in nearby countries, should attract media attention. Large‐scale disasters, due to their intensity and high impact on human lives, will find thorough media attention across the globe (Böhmelt, Reference Böhmelt2020), but the occurrence of ‘an average’ event will be reported more extensively in nearby and directly adjacent states. This claim mirrors Benesch et al. (Reference Benesch, Loretz, Stadelmann and Thomas2019) who find significant media spillovers between Germany and Switzerland, for instance, while Kwon et al. (Reference Kwon, Chadha and Pellizzaro2017) contend that news coverage represents more ‘culturally proximate’ cases. At the same time, Koopmans and Vliegenthart (Reference Koopmans and Vliegenthart2011) suggest that social relationships among countries also explain the diffusion of news coverage, and Rogers (Reference Rogers1995) presents the ‘homophily’ argument to claim that common interests (e.g., beliefs, education, social status) between sources and adopters induce diffusion. The environment is unlikely to be an exception here.

Again, with regard to the 2021 floods in Europe, the Belgian Interior Minister, Annelies Verlinden, stated that the floods in Belgium were ‘one of the greatest natural disasters our country has ever known’, and this has been widely covered, particularly in proximate countries’ media, including the United Kingdom.Footnote 10 Against this background, we argue that media coverage is a necessary requirement of the diffusion effect of natural disasters abroad on public opinion at home, that the media set the public agenda and provide the opportunity fort information flows across borders so that people can learn about events in other countries. Without that information, a diffusion effect simply cannot materialize. At the same time, the media's power to set the agenda reinforces the diffusion effect by influencing the attention citizens pay to natural disasters. However, while the media generally cover environmental events abroad, they tend to focus on those in closer proximity (Koopmans & Vliegenthart, Reference Koopmans and Vliegenthart2011).

Two additional remarks need to be made at this point. First, the public must pay attention to the news. We do not test this aspect empirically in the main text, but address it in the Supporting Information Appendix. Second, while media reporting on other countries is primarily driven by geographical distance (as we argue and focus on), it can be shaped by additional factors such as cultural preferences and power structures. The size of a country may be relevant for the diffusion process we argue for. For instance, a disaster in a larger state could exert a stronger influence than an environmental event in a smaller nation. Moreover, one may posit that a familiarity effect exists in that people are more familiar with proximate countries. Conceptualizing familiarity is challenging, but one way of doing this is via cultural similarity. In the Supporting Information Appendix, we present analyses for both of these additional influences and we return to this issue in the conclusion.

Disaster‐related feelings of threat, distress and uncertainty

Based on the literature on media coverage about environmental events and their impact (e.g., Bakaki et al., Reference Bakaki, Böhmelt and Ward2020; Dewenter et al., Reference Dewenter, Linder and Thomas2019), individuals are exposed to information about environmental disasters, and this information must influence them, their views and their behaviour psychologically. Hence, media coverage is only one aspect of the diffusion effect we argue for, albeit arguably a necessary one. Existing literature suggests that environmental disasters tend to have a psychological impact on individuals (Donner & McDaniels, Reference Donner and McDaniels2013), fuelling feelings of threat, distress and uncertainty (Shultz et al., Reference Schultz, Gouveia, Cameron, Tankha, Schmuck and Franek2005; Stimpson, Reference Stimpson2005). Disasters influence people's environmental risk perceptions (Blennow et al., Reference Blennow, Persson, Tomé and Hanewinkel2012) and the magnitude of an event, as well as its severity, increases this effect. This is related to how exposure is translated to experience. Particularly in the case of natural disasters that are rare phenomena, people may have a limited understanding of their impact – unless they experience them (locally). Demski et al. (Reference Demski, Capstick, Pidgeon, Sposato and Spence2017, p. 150) claim that ‘experiences of an extreme weather event might make climate risk more cognitively available or salient in people's minds’. And Carlton et al. (Reference Carlton, Mase, Knutson, Lemos, Haigh, Todey and Prokopy2016, p. 212) argue that especially the direct (local) experience with a disaster induces the perception that climate change is ‘more real, immediate, and local’ (see also Leiserowitz, Reference Leiserowitz2006; Myers et al., Reference Myers, Nisbet, Maibach and Leiserowitz2012), since it is not about a distant phenomenon that occurred far away (see also Van der Linden, Reference Van der Linden2014). In addition, an environmental disaster in one country soon induces relief efforts as well as support measures by political and social leaders in order to help (see Bechtel & Hainmueller, Reference Bechtel and Hainmueller2011). Citizens of nearby countries who are not (directly) affected by an event might not benefit from this (psychological) support and the comfort offered, which could add further distress and uncertainty.

We subscribe to these psychological consequences, but also argue that disasters can provoke feelings across national borders – though most likely so in nearby, neighbouring countries. That is, a disaster can put in motion a psychological process associated with a series of behavioural and attitudinal consequences, which lead to the outcome that even disasters in other countries that may not affect individuals (directly) have an impact on their views about the environment. The effect of a disaster creating feelings of threat, danger, distress, and uncertainty, however, should be most strongly felt in nearby countries – not remote and geographically distant places (see Pfefferbaum et al., Reference Pfefferbaum, Seale, McDonald, Jr, Rainwater, Maynard, Meierhoefer and Miller2000; Schuster et al., Reference Schuster, Stein, Jaycox, Collins, Marshall, Elliott, Zhou, Kanouse, Morrison and Berry2001; Sprang, Reference Sprang1999). As we detail in the following, egocentric and sociotropic mechanisms are responsible for this to unfold.

First, natural disasters often spread across borders and frequently affect more than one region. This makes individuals consider that such an event could distress them too in the future due to the geographical contagion of the event and the proximity to the individual.Footnote 11 Hence, we observe an egocentric response driven by fear of a similar disaster happening in one's own place that spreads across borders.

Second, social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel and Turner1979) suggests that people in bordering countries are more strongly tied to each other by, for example, frequent exchange, travel or family links, which induces an identification much more with those affected by a natural disaster (see also Böhmelt et al., Reference Böhmelt, Bove and Nussio2020). Against this background, a sociotropic response emerges where individuals change their attitude in light of human suffering across the border, but this is beyond their own distress and it may well be that they think such a specific disaster will be unlikely to happen to them. Therefore, residents from more distant countries should be less affected by this psychological dynamic. This is consistent with Lujala et al. (Reference Lujala, Lein and Rød2015, p. 491) who argue that ‘[a] person's proximity to the perceived manifestation of climate change and the distance to where the person believes that the climate change is likely to have the largest impact potentially play an important role on how people feel about climate change and how threatening they deem it for them personally, locally, or globally’. To illustrate this, consider the British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, who announced with regard to nearby countries via Twitter in 2021 that it was ‘shocking to see the devastating flooding in Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Belgium,’ adding that ‘the UK is ready to provide any support needed in the rescue and recovery effort’.

Third, and derived from the previous two points combined, natural disasters could produce meso‐level effects that cross state borders. Extreme weather events tend to enhance feelings of cohesion within a community, as individuals realize they must cooperate to achieve mutually desired goals, such as post‐disaster recovery (Sweet, Reference Sweet1998; Chang, Reference Chang2010). If ties across borders exist between neighbouring and geographically close countries, such an impact on group cohesion may well go beyond a more narrowly defined community, and could actually travel from one state to another, thereby affecting public opinion in the other country eventually.

In sum, we argue that natural disasters likely influence people's environmental views in nearby states. Media tend to report natural disasters that have occurred in countries closer to their ‘home’ audience, making seemingly local events gain attention abroad. This media coverage and the proximate distance of the disaster create feelings of danger, threat, distress, and uncertainty, which generate the psychological impact on individuals’ environmental attitudes. Conversely, individuals living in countries farther away from a disaster are likely to be less affected by the corresponding psychological processes, given that feelings of imminent danger and identification are less intense there and since local media probably provide less coverage. Ultimately, we expect that natural disasters in nearby countries are likely to affect environmental public opinion at home.

Design

Our dataset is mainly based on the Eurobarometer surveyFootnote 12 and contains information on the core components of our argument: people's attitudes toward the environment, natural‐disaster fatalities and several other variables that control for alternative mechanisms shaping public opinion on the environment. Our final sample comprises 32 European countries between 2002 and 2020. The spatial and temporal coverage of our data are driven by data availability in the Eurobarometer (explained below). The unit of analysis is the country‐year and, ultimately, we have data for 546 observations.

The Eurobarometer is the source for our dependent variable, people's views on the environment. After assessing all relevant variables on environmental attitudes in the Eurobarometer, we eventually opted for a measure of environmental salience (see also Böhmelt et al., Reference Böhmelt, Bove and Nussio2020). In general, the literature distinguishes between preferences and salience when it comes to environmental public opinion. The former mainly relates to certain levels of environmental protection or specific policies a respondent would like to see, for example, one could express the preference that their home state should lower emissions by 5 per cent. The latter, salience, is the ‘intensity of that feeling’ and the degree of importance that the individual attaches to the environment as a policy issue (for a discussion of the two concepts, see Hatton, Reference Hatton2017). While data availability in the Eurobarometer is better for environmental salience, there is also an important theoretical, policy‐relevant, and conceptual reason to focus on this: voters’ preferences will probably not become political priorities when salience is low. Only salient issues are likely to elicit strong policy responses. In addition, Hatton (Reference Hatton2017) notes that short‐run shocks, such as disaster‐related deaths, are more likely to influence salience than preferences (see also Demski et al., Reference Demski, Capstick, Pidgeon, Sposato and Spence2017).

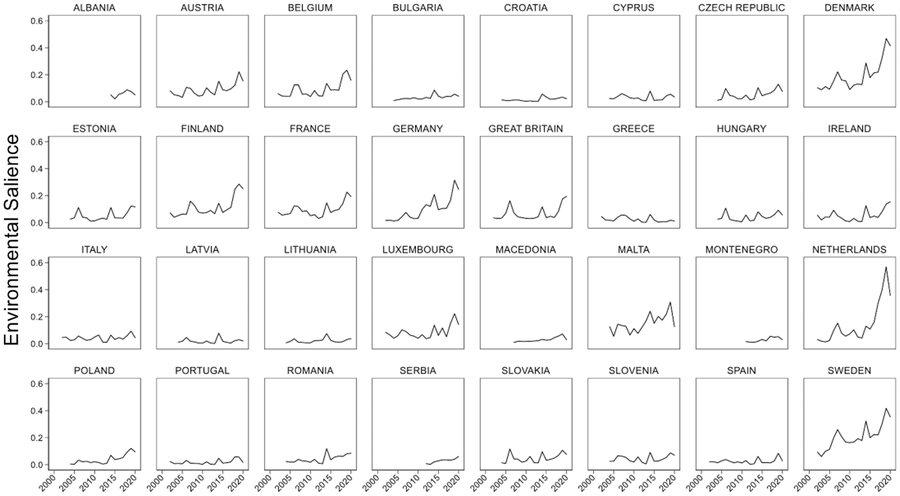

Considering this discussion, we focus on the question: ‘[w]hat do you think are the two most important issues facing (OUR COUNTRY) at the moment?’ With ‘environment’ or ‘environment, [and] climate (, and energy issues)’ as response options, the Eurobarometer has included this item consistently since the year 2002 and we use it to code the percent of respondents who stated that they perceive the environment as one of the two most salient policy issues in their country. After omitting the ‘don't know’ answers and missing values, we aggregate the individual‐level responses to the country level by averaging across all answers pertaining to a state each year.Footnote 13 Our final dependent variable thus captures the public's view on environmental salience, and it theoretically ranges between 0 (0 per cent of the population sees the environment as salient) and 1 (100 per cent of the population sees the environment as salient). For example, in the Eurobarometer survey 93.1 of 2020, 19.38 per cent of the French survey population stated that ‘the environment and climate change’ belong to the top two most important policy issues facing France at the present time. Overall, our dependent variable's mean value is 0.068 (standard deviation of 0.074), suggesting that 6.8 per cent of the entire survey population across countries and years saw the environment as a salient policy issue. In Figure 1, we plot Environmental Salience and its development across time for each country in our sample.

Figure 1. Environmental attitudes in Europe.

Our main interest is exploring how this variable on people's perception of environmental salience is shaped by environmental disasters in other countries. To this end, we make use of a distinct estimation procedure that incorporates a uniquely created variable suitable for our purposes. Specifically, we estimate spatial‐X models (Franzese & Hays, Reference Franzese and Hays2007, Reference Franzese and Hays2008; Plümper & Neumayer, Reference Plümper and Neumayer2010, p. 420f), which ‘regress the dependent variable on the values of one […] independent explanatory variable’. The main models presented below are based on ordinary least squares (OLS), but we have cross‐checked our findings using the maximum‐likelihood procedure by Franzese and Hays (Reference Franzese and Hays2007, Reference Franzese and Hays2008), which ‘does not assume a temporally lagged spatial lag and addresses simultaneity bias head on’ (Ward & Cao, Reference Ward and Cao2012, p. 1084; see also Elhorst, Reference Elhorst2001). In our case, Environmental Salience (dependent variable) thus is a function of environmental disasters in other countries, and a weighting matrix specifies the subset of countries that have an influence on the outcome. We capture this with the item WxDisaster Fatalities. This variable is the product of the weighting matrix based on state‐to‐state contiguity that we use to operationalize geographical proximity and a variable on disaster‐related deaths.

First, using the correlates of war direct contiguity data (Douglas et al., Reference Douglas, Tir, Shafer and Gochman2002), the elements in the connectivity matrix capture the contiguity of country i and country j as defined by a land/river border or the two are separated by max. 400 miles of water (value of 1 in the matrix). This is our operationalization of the spatial proximity, which we introduce in the theory above. If there is no such border between countries, they are separated by more than 400 miles of water, or elements refer to two different years in the matrix, we assign a value of 0 (also wi,i = 0).Footnote 14 We row‐standardize the matrix: ‘after row‐standardization, contiguous countries exert an influence that becomes proportionally smaller the larger the number of contiguous countries’ (Plümper & Neumayer, Reference Plümper and Neumayer2010, p. 430). In our European context, it seems unlikely that the number of neighbouring states is of importance and all contiguous countries probably exert the same influence. However, row‐standardization facilitates the interpretation of the results and, thus, we opt for this specification in the following. That said, the substance of our findings is not affected by this research‐design choice and non‐standardized matrices produce qualitatively similar results.

Second, we multiply this matrix with a variable on the number of fatalities from environmental disasters in countries j each year (i.e., sending states from which the spatial stimulus originates). We rely on the international disaster database (IDD) from the Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED).Footnote 15 As indicated above, this dataset defines a disaster as a ‘situation or event, which overwhelms local capacity, necessitating a request to national or international level for external assistance; an unforeseen and often sudden event that causes great damage, destruction and human suffering. Though often caused by nature, disasters can have human origins’. We focus on natural disasters and, eventually, the following types of events are included in our data: droughts, earthquakes, epidemics, extreme temperatures, floods, landslides, mass movements (dry), storms, volcanic activity and wildfires. Given our argument on media coverage, which facilitates the cross‐national diffusion of information, we follow Koopmans and Vliegenthart (Reference Koopmans and Vliegenthart2011) who argue that the number of people killed by a disaster is arguably the strongest predictor of media coverage. Hence, our interest lies on the (logged) number of fatalities from these disasters, which we multiply with the weighting matrix to create WxDisaster Fatalities. Fatalities are defined by the IDD as the ‘number of people who lost their life because the event happened’. Disaster‐related deaths should especially make it to the news and are likely to be more covered than all people affected or economic losses and damage. If a disaster is ‘vivid and catastrophic, if it strikes’ (Weber & Stern, Reference Weber and Stern2011, p. 324), it is more likely to cause loss of life. This intensifies media coverage. Along those lines, Brody et al. (Reference Brody, Zahran, Vedlitz and Grover2008) show that human fatalities caused by weather events in local areas are predictive of people's perceived risk of climate change. And Demski et al. (Reference Demski, Capstick, Pidgeon, Sposato and Spence2017, p. 150) state that extreme weather events ‘act as a strong “signal” or “focusing event” […] whereby future climatic events are made more imaginable, indicating dramatic changes to familiar and local places, in turn heightening the sense of risk posed by climate change’.

We control for a series of other influences that are correlated with environmental attitudes at the domestic level and constitute alternative mechanisms shaping environmental public opinion. Hence, we rule out countries’ common exposure to similar exogenous (unit‐level) factors, which – rather than a genuine diffusion process – might influence people's environmental salience (Franzese & Hays, Reference Franzese and Hays2007, p. 142). Thereby, we intend to ensure that contagion ‘cannot be dismissed as a mere product of a clustering in similar [state] characteristics’ (Buhaug & Gleditsch, Reference Buhaug and Gleditsch2008, p. 230; see also Franzese & Hays, Reference Franzese and Hays2007, Reference Franzese and Hays2008; Plümper & Neumayer, Reference Plümper and Neumayer2010, p. 427). First, we include country and time fixed effects in all our models. The latter items control for system‐wide shocks such as the 2011 ‘Fukushima nuclear disaster’. The former variables address any influence stemming from time‐invariant, idiosyncratic factors.

Second, we include the variable Disaster Fatalities (ln). This item is a log‐transformed count variable, measuring the number of disaster fatalities in the focal country i in a given year. As in the case of the spatial variable, we use the IDD and its definition of disasters as well as disaster‐related deaths. The main difference between Disaster Fatalities (ln) and WxDisaster Fatalities is that the former is based at the domestic level, the latter concentrates on influences from abroad in the form of a transnational diffusion effect. Eventually, we capture whether environmental public opinion is also shaped by disasters ‘at home’. Although we argue that the psychological dynamics of natural disasters expand beyond national boarders, we postulate that this spatial effect will be less strongly pronounced than when people are directly affected by natural disasters (as captured by Disaster Fatalities (ln)). Direct, personal experience of danger differs from proximity to it. People more readily trust the evidence of their senses (Whitmarsh, Reference Whitmarsh2008) and, thus, those who have suffered from the direct impact of a disaster, like injuries, are expected to develop a more elevated concern with the environment.

Third, we control for the median voter and people's left‐right self‐placement using the Eurobarometer. Most surveys comprise an item on respondents’ left‐right self‐placement on a scale from 1 (left) to 10 (right) (Schmitt & Scholz, Reference Schmitt and Scholz2005). Individual‐level values are aggregated to the country level via Tukey's (Reference Tukey1977) method. The more ‘conservative’ the public is, the less likely the environment will be perceived as a salient policy issue. In our sample, this variable has a mean value of 5.212 (standard deviation of 0.343).

Fourth, all states in our data are (established) democracies, but we address any remaining imbalance by considering the polity2 item from the Polity V data (Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2016). This variable theoretically ranges between −10 and 10, with higher values signifying more democratic states. However, given a mean value of 9.592 in our dataset, cross‐country variation is rather low.

Fifth, two variables are taken from the World Bank Development Indicators: states’ economic development and their population. We use GDP per capita (in current US Dollars) for the former, which is defined as the gross domestic product (GDP) divided by midyear population. GDP is the sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy plus any product taxes and minus any subsidies not included in the value of the products. For the latter, population size is likely to be linked to the degree of preference heterogeneity in a society. We rely on a country's midyear total population, which counts all residents regardless of legal status or citizenship (except for refugees not permanently settled). Both variables are log‐transformed to account for their skewed distributions.

Finally, we control for environmental‐friendly political parties in a country's national parliament. The better the Greens are represented in the legislative, the more strongly pronounced the public mood on the environment should be. We rely on the Comparative Political Dataset by Armingeon et al. (Reference Armingeon, Engler and Leemann2020) who have compiled the information on the share of seats in parliament for political parties classified as ‘green’.

Results

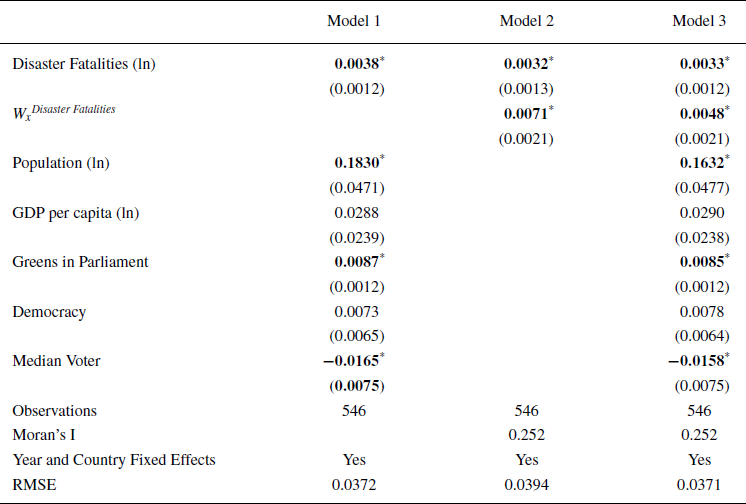

The main models are presented in Table 1. The first estimation here is a ‘naive’ model as we only consider the controls and the domestic‐level disaster‐fatality item. The spatial variable capturing a transnational diffusion effect is left out here. Model 1 thus ignores an impact from environmental disasters in other countries. Model 2 assumes a different perspective as we now include WxDisaster Fatalities next to Disaster Fatalities (ln). We omit the substantive controls, though, which shows that their inclusion or exclusion does not alter our main findings. Model 3 constitutes our full model as all explanatory variables we introduced in the previous section are included. As we row‐standardize the spatial variable's connectivity matrix, its coefficient can be interpreted directly. However, the coefficients provide information only about the pre‐dynamic effects, that is, ;the pre‐[spatial] interdependence feedback impetus to outcomes from other regressors’ (Hays et al., Reference Hays, Kachi and Franzese2010, p. 409). To fully understand the direct and indirect effects of WxDisaster Fatalities, Figure 3 also presents full spatial effects comprising direct, indirect, and feedback effects based on spatio‐temporal multipliers, which allow the ‘expression of estimated responses of the dependent variable across all units’ (Hays et al., Reference Hays, Kachi and Franzese2010, p. 409).

Table 1. Environmental salience and disasters abroad

Notes. Table entries are coefficients; standard errors in parentheses; constant, year fixed effects, and country fixed effects included in all models, but omitted from presentation. Estimates significant at 5 per cent (two‐tailed) in bold.

* significant at 5% (two‐tailed).

WxDisaster Fatalities is positively signed and statistically significant in Table 1. According to Model 2, if all neighbours of a focal country observed at least three fatalities from environmental disasters, public concern about the environment would increase by almost 1 percentage point (0.007). Considering all controls in Model 3, this decreases to about 0.5 percentage points. Hence, we obtain evidence that fatalities from environmental disasters abroad influence public opinion on the environment at home.

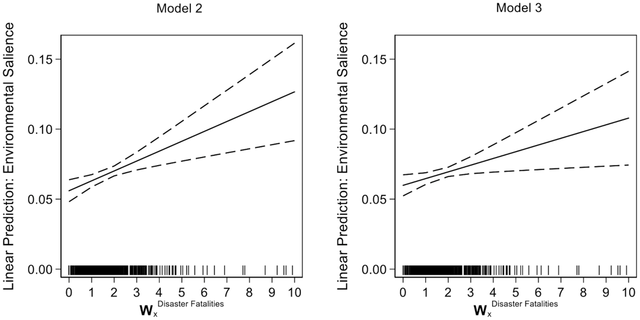

Figure 2 depicts predicted values of Environmental Salience for values of WxDisaster Fatalities, while holding all other variables constant at their means. At the minimum of the spatial item, which pertains to no disaster fatalities in neighbouring states, our model predicts a value of about 6, that us, on average, 6 per cent of the population would indicate that the environment is one of the two most salient issues affecting their country. The point estimate of the predicted values increases to more than 10, however, when raising WxDisaster Fatalities to its sample maximum.

Figure 2. Predicted values of Environmental Salience by WxDisaster Fatalities.

Notes: The dashed lines pertain to the 95 per cent confidence interval; the rug plot along the x‐axis illustrates the distribution of WxDisaster Fatalities.

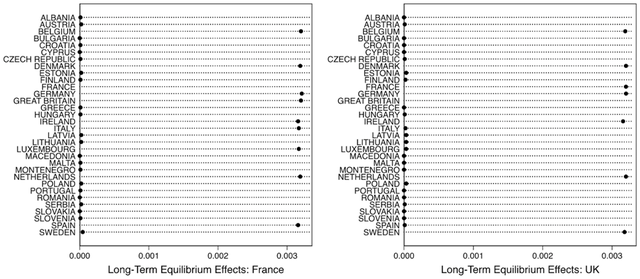

For the long‐term equilibrium impacts, that is, the higher‐order effect of disaster fatalities in j on its neighbour i, which feeds back and then influences others via direct and indirect links (see also Ward & Cao, Reference Ward and Cao2012, pp. 1092–1094), we focus on Model 3 while including a decay function. This function is given by 2 raised to the power of −(number of years since last disaster abroad/α), with α being the half‐life parameter. We determined that a half‐life of 2 years produced the best fit and mirrors earlier research on how long lasting the effects on public opinion are (see Bechtel & Hainmueller, Reference Bechtel and Hainmueller2011). The simulation is based on the year 2020 for hypothetically inducing exp(5) = 148 disaster‐related deaths in two states one at a time: France and the United Kingdom.Footnote 16 We then calculate the long‐term effects on all states, as the shock reverberates through the system. The decay function included in the estimation accounts for the fact that an environmental disaster does not last forever in shaping public opinion, which would lower second‐order effects.

Figure 3 suggests that the proclaimed spatial effect is both significantly and substantively important. Linking these findings to our theory, we find strong and robust support for our hypothesis. In sum, therefore, environmental disasters abroad strongly influence public opinion on environmental salience at home.

Figure 3. Spatial long‐term equilibrium effects.

Notes: Notes: Entries pertain to spatial long‐term equilibrium effects in other countries when simulating 148 disaster fatalities in either France (left panel) or the United Kingdom (right panel). Direct effects for France (0.9566) and the United Kingdom (0.95658) are not reported to improve readability. Calculations are based on Model 3 while including a decay function and 1,000 random draws from the multivariate normal distribution of the spatial lag and the decay variable.

The results concerning the control covariates are mixed. Four of these variables consistently display significant effects, however. First, the larger the population of a country, the higher the share of the population seeing the environment as a salient policy issue. Second, the larger the share of the Greens in parliament, the higher the values of Environmental Salience. Third, as expected, more rightist political views are linked to less environmental concerns. We obtain a negative coefficient estimate for Median Voter, which highlights that higher values on the left‐right self‐placement variable are associated with lower values on Environmental Salience. Finally, and in line with previous work (e.g., Bergquist et al., Reference Bergquist, Nilsson and Schultz2019; Demski et al., Reference Demski, Capstick, Pidgeon, Sposato and Spence2017; Lu & Schuldt, Reference Lu and Schuldt2015, Reference Lu and Schuldt2016; Reser et al., Reference Reser, Bradley and Ellul2014), we find evidence for a domestic‐level effect of disasters on environmental salience. Comparing the coefficients of Disaster Fatalities (ln) and WxDisaster Fatalities, the former's is somewhat smaller, although there is no statistically significant difference between the two.

We assessed the robustness of our empirical findings with several additional analyses, which are summarized in the online appendix/supplementary information (SI). There, we address issues of intra‐group correlations by clustered standard errors and we introduce a spatial Durbin model (Elhorst, Reference Elhorst2010). We also evaluate our findings conditional on countries’ population size and economic power, we control for the level of environmental quality, and we employ capital‐to‐capital inverse distance weights in the connectivity matrix. Moreover, we explore cultural similarities, different characteristics of natural disasters, and we examine the influence of news media consumption. Finally, we present more disaggregated analyses at the regional and individual levels, while concluding the additional analyses with a quasi‐experimental study of public opinion during the Greek wildfires in 2018. These supplementary checks increase the confidence in our main result: environmental attitudes ‘at home’ are systematically driven by environmental‐disaster fatalities in neighbouring countries.

Conclusion

What drives public opinion about climate change and the environment? An extensive body of research has examined the determinants of public opinion (for recent overviews, see, Bakaki & Bernauer, Reference Bakaki and Bernauer2017a, Reference Bakaki and Bernauer2017b; Bernauer & McGrath, Reference Bernauer and McGrath2016; Hornsey et al., Reference Hornsey, Harris, Bain and Fielding2016; Howe et al., Reference Howe, Marlon, Mildenberger and Shield2019; Marquart‐Pyatt et al., Reference Marquart‐Pyatt, McCright, Dietz and Dunlap2014), with many of those studies exploring the impact of disasters. We have sought to contribute to and extend this debate by examining the spatial dynamics surrounding environmental events and public opinion.

We contend that environmental public opinion is influenced by natural disasters even when those disasters occur beyond a country's borders. Media coverage of environmental disasters is facilitated when events are intense and nearby; what is more, the proximate distance of a disaster creates feelings of threat, danger, distress, and uncertainty, which in turn shape individuals’ environmental attitudes. Our empirical findings, based on the analysis of Eurobarometer and disaster data, highlight that natural disasters abroad can significantly increase concerns over the environment. Thus, environmental events in other countries, particularly those in the direct neighbourhood, play an important role in explaining environmental public opinion. Combining this conclusion with existing research on the ‘local’, domestic‐level impact of disasters (e.g., Bergquist et al., Reference Bergquist, Nilsson and Schultz2019; Demski et al., Reference Demski, Capstick, Pidgeon, Sposato and Spence2017; Lu & Schuldt, Reference Lu and Schuldt2015, Reference Lu and Schuldt2016; Reser et al., Reference Reser, Bradley and Ellul2014), we believe to be among the first to show that the influence of natural disasters on environmental public opinion is even larger than hypothesized by previous research.

The implications of these findings are important for both the academic literature and policymakers. On one hand, this research provides substantial evidence of the cross‐border influence of natural disasters, and to this end, our general understanding of how public opinion is formed is improved. On the other hand, recent research shows that policymaking pays attention to public opinion (e.g., Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Böhmelt and Ward2018; Boswell et al., Reference Boswell, Corbett, Dommett, Jennings, Flinders, Rhodes and Wood2019; Bakaki et al., Reference Bakaki, Böhmelt and Ward2020; Schaffer et al., Reference Schaffer, Oehl and Bernauer2022). The more the public sees the environment as an important issue, the more likely it is that corresponding policies will be implemented. Hence, an implication of our research is a potentially important route to engagement with climate change and a window of opportunity to build political support for environmental mitigation policies.

There are several interesting questions to explore in further research. First, one question worth exploring is whether the effect we identified in the European sample exists elsewhere or even worldwide. On one hand, similar analyses using data from the LatinobarometerFootnote 17 or the AfrobarometerFootnote 18 may want to confirm that what we find for Europe is a phenomenon that is present in other regions, too. On the other hand, and derived from this, a global analysis would go even further, although countries’ interconnectedness or the power structures behind media reporting are likely to be more crucial than in our setup and must be taken into account more thoroughly than it can be done it in the analyses above as well as in the appendix. In any case, substantial data collection efforts would be necessary for such studies, as high‐quality and comparable survey data does not exist for all countries worldwide.

Second, it would be useful to identify conditions under which environmental disasters abroad influence environmental attitudes at home. Relatedly, media reporting on other countries is shaped by additional factors and exploring these may be an effort worth making. And recall that contiguity – our proxy for the transnational flow of information via mass media – does not capture the ‘whole story’. Indeed, factors such as power, influence, or cultural similarity of other countries abroad are likely to influence whether people may have followed the news and/or whether the media covers a specific environmental event in the first place. Alternative and supplementary forms of connectedness (see also Deutschmann et al., Reference Deutschmann, Delhey, Verbalyte and Aplowski2018) and as presented above as well as in the Supporting Information, provides some analyses based on the characteristics of disasters or the size and power of sending countries. Clearly, however, other conditional influences and forms of interconnectedness could exist, even though space limitations prevent us from thoroughly analyzing these theoretically and empirically. It will be interesting to explore them in detail.

Finally, our theory suggests several different mechanisms, egocentric and sociotropic ones, which link disasters abroad with public‐opinion changes at home. It could be useful, also with a view towards more accurate policy recommendations, to be able to empirically distinguish between these mechanisms and to fully clarify which are the more influential factors. We cannot distinguish among mechanisms with the existing data material, but we believe this would be an exciting avenue for further work. Future research could also try move beyond the study of environmental public opinion and analyze whether natural disasters influence environment‐related action, like environmental activism or pro‐environmental voting.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A.1. Clustered Standard Errors

Table A.2. Spatial Durbin Model

Table A.3. Population Size and Economic Power

Table A.4. Environmental Quality

Table A.5. Inverse‐Distance Weights

Table A.6. Alternative Disaster Characteristics

Table A.7. Cultural Similarity

Figure A.1. News Media Consumption

Table A.8. News Media Consumption

Table A.9. Disaggregated Analysis: Regional Level

Table A.10. Disaggregated Analysis: Individual Level

Figure A.2. Marginal Effect Estimates