I. Introduction

Nearly four decades ago, the District Court for the Southern District in New York, United States of America (USA), in the Bhopal case, characterised the application of American laws to incidents occurring abroad as ‘imperialist’, while interpreting the jurisdictional clause in favour of the corporation.Footnote 1 By contrast, in 2019, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom (UK), in the Vedanta case, expressed cautious reluctance to suggest that Zambian courts—where the facts unfolded—might be inadequate for claimants seeking justice, fearing accusations of imperialism.Footnote 2 These divergent judicial approaches, from deference to corporate interests in Bhopal to hesitant support for human rights victims in Vedanta, underscore an enduring struggle within transnational litigation. This article argues that the real issue lies not in perceived judicial imperialism but in the structural imbalances ingrained within the transnational legal framework, which perpetuate systemic injustice. It explores one of the critical dimensions of these injustices, the structural imbalance created under international investment law (IIL). Specifically, it examines whether integrating access to remedy provisions into international investment agreements (IIAs) could alleviate the structural imbalance by enabling both national and transnational litigation avenues for human rights victims. The article also considers possible mechanisms which might operationalise such provisions effectively to address these structural imbalances.

The structural imbalance originates from the dual obligations imposed on states by two distinct branches of international law: international human rights law (IHRL) and IIL. Under IHRL, states must provide access to an effective remedy to the victims of human rights violations, including those perpetrated by transnational business entities.Footnote 3 Simultaneously, under IIL, many IIAs grant foreign investors substantive protections—including, but not limited to, minimum standards of treatment, fair and equitable treatment, and protection against expropriation—effectively securing quasi-property rights for transnational business entities operating within host states.Footnote 4 This duality becomes pronounced when human rights violations occur, as victims often face limited pathways for seeking redress against the state or the corporation.Footnote 5 In stark contrast, corporations enjoy extensive recourse under the Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanism, enabling them to claim substantial financial compensation from states that fail to uphold their IIL obligations.Footnote 6 These significant compensation awards, combined with the constraints IIAs impose on states’ ability to regulate in the public interest,Footnote 7 have prompted states to reconsider their commitments to such agreements,Footnote 8 including their consent to the ISDS mechanism.Footnote 9 Reflecting these concerns, the reform of the ISDS mechanism has been under discussion within the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law’s (UNCITRAL) Working Group III since 2017.Footnote 10 Similarly, in 2023, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s (UNCTAD) Investment Policy Hub launched a ‘Multi-Stakeholder Platform on IIA Reform’ as an informal expert group aimed at facilitating knowledge-sharing and the exchange of best practices on IIA reform.Footnote 11 However, these reform efforts are primarily procedural and remain driven by state dissatisfaction with the ISDS mechanism,Footnote 12 rather than reflecting any substantive reorientation towards the perspectives of rightsholders.Footnote 13 To address this imbalance, this article adopts a rightsholder’s perspective, examining whether individuals and communities harmed by foreign investors’ operations in host states should be granted access to remedies analogous to those available to investors under the ISDS mechanism. By exploring this question, it seeks to contribute to the broader discourse on rebalancing the rights and responsibilities of investors within IIL.

This paper builds upon the issues highlighted and remedies proposed in a 2021 report of the United Nations Working Group on human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises (UNWG).Footnote 14 The report advocates for the establishment of direct remedial mechanisms for communities and individuals affected by transnational investors,Footnote 15 advancing an ‘all roads to remedy’ approach, highlighted in the 2017 UNWG report, to address the asymmetrical framework of IIL.Footnote 16 Correcting this imbalance necessitates embedding access to remedy provisions within the investment law framework, thereby providing affected communities with viable pathways to hold investors accountable.Footnote 17 The 2021 UNWG report proposes two potential avenues for balancing this asymmetry. First, it suggests enabling rightsholders—individuals and communities—to bring international arbitration claims directly against investors for human rights violations.Footnote 18 Second, it proposes incorporating access to remedy provisions within IIAs, granting rightsholders the ability to bring direct claims against investors in their home states.Footnote 19 This article evaluates how the second avenue can be further developed to help address the structural imbalance inherent in IIL.

To cure the structural imbalance within the IIL, this article argues that inclusion of remedies in IIAs must not be restricted to home states but also extended to the host states, where human rights abuse frequently occurs. This becomes more important where the host states are in the Global South. In this pursuit, Part II examines the critique of transnational litigation by anti-imperialist scholars, highlighting that while they correctly identify structural imbalances within the transnational legal system, their analysis remains narrow. Specifically, they fail to account for the systemic protections afforded to investors under this system, overlooking the broader implications of these imbalances. Part III of the article then evaluates the feasibility and effectiveness of including access to remedy provisions in IIAs, specifically to facilitate human rights litigation against transnational corporations within host states. Part IV offers concluding remarks.

II. Legal Imperialism: Structural Imbalance and Systemic Injustice?

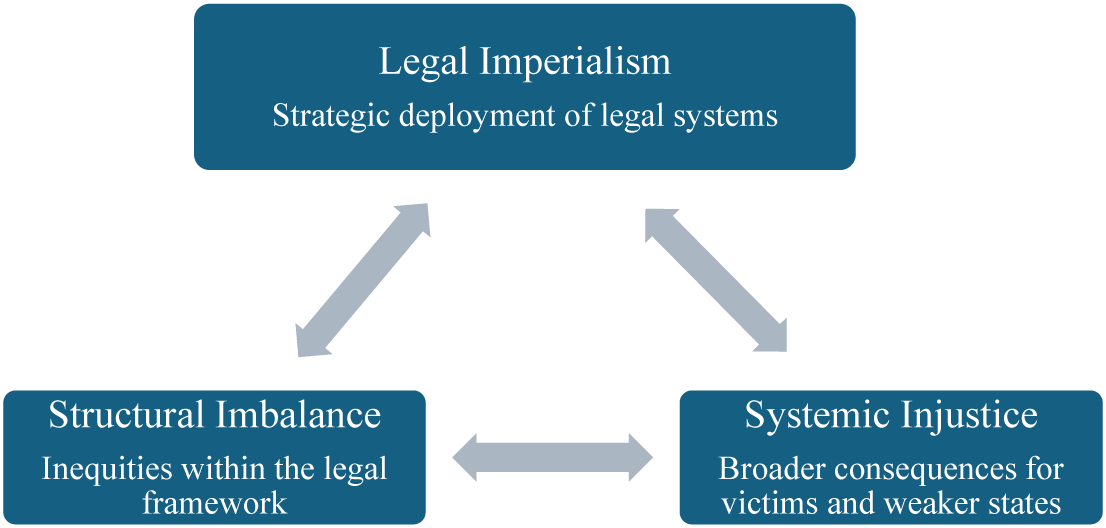

Legal imperialism manifests in various forms and interpretations. For the purposes of this article, it is defined as the strategic deployment of legal systems by states to create structural imbalance and systemic injustice within a national or international legal system. This definition is derived from analysing the broader impacts of the transnational application and frameworks of laws. It diverges from the narrower understanding often espoused by anti-imperialists who focus only on transnational litigation. Some anti-imperialists limit their definition of legal imperialism to the extraterritorial application of national laws, whether substantive or procedural, through transnational litigation, viewing such practices as inherently imperialist.Footnote 20 They argue that dominant legal systems, particularly those of powerful states, exert influence over less powerful nations, thereby undermining the sovereignty and autonomy of weaker states.Footnote 21 Others, such as Gibney, offer a more specific critique, defining legal imperialism as the application of double standards by dominant states. Gibney posits that ‘legal imperialism occurs when a dominant state … applies one set of legal standards to itself, but a much different (and invariably stricter) set of standards for all others, particularly for those in the Global South.’Footnote 22 Unfortunately, regardless of the form it takes, imperialism disproportionately harms weaker entities, those disadvantaged by the very structural imbalances it perpetuates. Yet, much of the discourse on legal imperialism has centred on its causes, rather than critically analysing its broader effects. The courts in the Bhopal and Vedanta cases, though reaching different jurisdictional outcomes, similarly identified imperialism in this narrower sense of extraterritorial application of national laws, rather than delving deeper to identify the strategic injustice within the transnational legal system, which endangers human dignity.

Ironically, whereas the extraterritorial exercise of civil jurisdiction is frequently critiqued as a form of legal imperialism and is often viewed with scepticism within the framework of private (international) law, public international law tends to afford greater legitimacy to the extraterritorial application of criminal jurisdiction under certain accepted principles.Footnote 23 In addition, states often invoke principles rooted in public international law to justify the extraterritorial application of their domestic laws in civil and regulatory matters as a matter of protecting state interest. Doctrines such as the nationality principle, the effects doctrine and the protective principle are frequently relied upon to extend jurisdiction beyond territorial borders.Footnote 24 For instance, the USA applies its sanctions regime not only to domestic entitiesFootnote 25 but also to foreign subsidiaries of US-based corporations and even to non-US nationals, based on the argument that their conduct affects US interests.Footnote 26 While these jurisdictional assertions may be legally framed within the existing rules of public international law, they also illustrate how such rules are applied selectively, often reflecting national political or economic priorities. This selective invocation reinforces a transnational legal order that legitimises state-led extraterritoriality when it aligns with state or corporate interests, thereby contributing to what some scholars have described as the ‘imperialism of non-state actors.’Footnote 27

A. Imperialist Tendencies in International Investment Laws

The legal imperialism is entrenched through the national investment laws and IIL, which prioritise the protection of business entities via transnational legal jurisdictions. These laws provide favourable legal frameworks for transnational business entities, particularly when operating through complex corporate structures. Most IIAs define investment broadly to include ownership or control by investors, allowing corporations to exploit this structure for strategic legal advantages.Footnote 28 There are two key ways in which investors use subsidiaries which cause structural imbalance. First, subsidiaries restrict the application of national regulations to the subsidiary entity alone, shielding the parent company from direct accountability under domestic laws. On the other hand, a parent company can invoke investment treaties, claiming that the subsidiary is a qualifying investor under an IIA, enabling claims against host states before arbitral tribunals.Footnote 29 Second, subsidiaries facilitate jurisdictional arbitrage, further enabling firms to gain access to favourable investment treaties and the ISDS mechanism. For example, parent companies often establish subsidiaries in third-party states that have favourable investment agreements with the target market, thus gaining access to the ISDS mechanism.Footnote 30 It is estimated that nearly a quarter of the world’s 500 largest firms route their foreign assets through subsidiaries located in transit countries to get access to the ISDS mechanism.Footnote 31 While the ISDS mechanism operates under the framework of international law and gets its legitimacy from the will and consent of states, its practices have often been criticised as imperialistic, particularly for disproportionately protecting investors from powerful states.Footnote 32 The disparate use of subsidiaries in litigation also provides an opportunity for ‘forum shopping’ to business entities. Forum shopping refers to the liberty of choosing among an existing set of rules.Footnote 33 The business entities have the liberty to choose a forum for dispute settlement, either ISDS (directly or through a subsidiary firm) or national legal systems through a subsidiary firm or transnational commercial dispute settlement laws, whichever favours them.Footnote 34 While the investors have all the operational liberties protected under the national and international legal systems including forum shopping, the rightsholders impacted by their operations are mostly left with limited effective legal remedies.

This issue of legal imperialism prevalent in the transnational legal system, particularly through IIL, can be illustrated through the example of the pesticide Dibromo Chloropropane (DBCP). This chemical was banned by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the late 1970s due to its proven link to male sterility and other severe health effects.Footnote 35 However, despite the domestic prohibition, US corporations continued producing DBCP for export to countries in the Global South, where regulatory protections were weaker and enforcement mechanisms limited. Workers in countries such as Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and the Philippines were exposed to the pesticide and later filed lawsuits against the companies involved.Footnote 36 Yet, due to jurisdictional and legal barriers, including the non-enforcement of national court decisions across borders, many of these victims were unable to obtain effective remedies.Footnote 37 As highlighted by Gibney, this example underscores how the global legal order can enable corporations to circumvent domestic regulatory constraints and externalise harm onto vulnerable populations, exemplifying a form of legal imperialism entrenched in the structure of IIL.Footnote 38

Numerous pesticides banned within the USA have continued to be exported to less-regulated markets in the Global South.Footnote 39 When the USA bans not only the use but also the export of such pesticides, some anti-imperialist critics might frame this as an extraterritorial imposition of the American legal norms—a form of regulatory imperialism. Others would argue that such bans infringe upon the sovereign right of other states to regulate and permit substances as they see fit. Gibney, however, frames the situation differently, arguing that the true manifestation of legal imperialism lies in the refusal to extend the protections of a domestic ban to other jurisdictions.Footnote 40 From my perspective, the injustice is not only about the permissibility of hazardous substances but about the design of the transnational legal system that inherently creates structural imbalances. This system privileges the legal and procedural interests of corporations—particularly through IIL—while leaving affected individuals with little to no access to comparable remedies. Corporations are empowered to initiate ISDS claims, seek compensation for regulatory interference and enforce arbitral awards globally. In contrast, pesticide-exposed workers in the Global South often face insurmountable obstacles, including underdeveloped tort systems, barriers to transnational litigation and a complete absence of standing under investment treaties.Footnote 41

Admittedly, one might question why states in the Global South permit the import of banned substances in the first place. While this is a valid concern, the answer often lies in a combination of structural challenges, i.e., weak regulatory frameworks, pervasive corruption, economic dependency and state complicity.Footnote 42 All these factors constrain the ability of such governments to effectively regulate harmful products. However, regardless of these structural challenges, the more pressing issue lies in the systemic absence of effective remedies for victims of transnational corporate harm, remedies that would almost certainly be available to corporate investors if their rights were similarly affected.

This discrepancy lies at the heart of the business and human rights (BHR) discourse. Indeed, one of the foundational concerns that sparked the BHR movement is precisely this question: why should businesses be allowed to profit at the expense of rightsholders, particularly in contexts where weak governance and an inequitable global legal order deny victims meaningful access to justice?Footnote 43 The asymmetry manifested in disparities of legal standing, access to enforcement mechanisms and institutional power constitutes a core structural imbalance in the transnational legal system. Thus, the more appropriate question is not merely whether certain harmful products are allowed or banned, but whether individuals harmed by corporate activities can access justice on terms comparable to those enjoyed by corporate actors within the same legal architecture. This structural imbalance highlights the extent to which legal systems tend to prioritise corporate and state interests over the equitable protection of vulnerable populations—namely, the rightsholders (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Legal imperialism explained

B. Structural Imbalance within Transnational Law

Beyond IIL, transnational business entities operate within a broader framework often referred to as transnational law or private international law. This system is primarily designed to safeguard commercial interests and facilitate global business operations, primarily settling the issues of jurisdiction and choice of law in private matters.Footnote 44 The extraterritorial application of laws in private matters is widely accepted within this framework and is rarely criticised as imperialistic.Footnote 45 While anti-imperialists often critique public international law as a tool of legal imperialism, they seldom apply the same scrutiny to transnational law, perhaps because it is perceived as dealing with private rather than public matters.Footnote 46 This distinction, however, obscures a critical reality: the transnational legal system—crafted by states to protect business interests—provides limited avenues for rightsholders to seek effective remedies for harms caused by corporate activities. Paradoxically, this system not only prioritises the protection of private entities but, in some cases, enables these entities to obstruct state efforts to enact policies in the public interest.Footnote 47 This interplay between transnational private law and public international law, including IIL, collectively fosters structural imbalances within the international legal system. Although some scholars distinguish between private and public legal regimes based on their scope and focus,Footnote 48 this distinction loses significance when both systems are created by states fully aware of their international obligations under IHRL. The absence of mechanisms to protect rightsholders within these systems reflects a deliberate prioritisation of corporate interests over human rights, revealing imperialistic tendencies within the global legal order. Achieving structural balance necessitates a fundamental transformation of the transnational legal system to address the structural inequities it has institutionalised.

III. Balancing Structural Inequities in IIL for Systemic Justice

One of the primary factors contributing to structural imbalance in IIL is the disparity in access to remedy systems between investors and rightsholders. While efforts are underway outside the investment law regime to facilitate transnational human rights litigation through national laws, particularly in the Global North, these efforts remain limited in scope.Footnote 49 In addition, modern IIAs have begun to incorporate investor responsibility clauses, reflecting an emerging recognition of corporate accountability.Footnote 50 However, while recent developments indicate a gradual shift towards integrating remedy clauses within IIAs, the inclusion of clauses specifically addressing the needs of rightsholders remains a nascent and underexplored area, with efforts predominantly focused on transnational remedies in home states. Although some scholars view transnational human rights litigation in home states as a viable means of holding corporate entities accountable,Footnote 51 and some even justify it from the victims’ perspective,Footnote 52 exclusive reliance on such mechanisms will not achieve the structural balance within the IIL regime. A comprehensive approach that includes accessible and effective remedies in host states, alongside other transnational mechanisms, is necessary to bridge the current gap and ensure equitable outcomes for affected rightsholders.

A. Recent Developments in Remedy Clauses

Recent developments indicate a gradual inclusion of remedy clauses within IIAs, reflecting a growing recognition of the need for accountability mechanisms that extend to home states. An example of this emerging trend is the bilateral investment treaty (BIT) between Morocco and Nigeria, which explicitly subjects investors to civil liability in their home state for acts or decisions related to investments that result in ‘significant harm, personal injury, or loss of life in the host state’.Footnote 53 Notably, this BIT integrates labour standards by referencing the International Labour Organization (ILO) Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work as the applicable law in relevant disputes.Footnote 54 Furthermore, the treaty obligates investors to comply with environmental, labour and human rights commitments binding on both the home and host states,Footnote 55 establishing a framework that aligns corporate conduct with international obligations.

This BIT has influenced subsequent investment-related instruments in two significant ways. First, it has informed the draft Investment Protocol to the Agreement establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).Footnote 56 The Protocol incorporates investor obligations, including civil liability for harms related to environmental degradation or human rights violations. It also grants victims the right to initiate legal action against investors in their home state for acts or omissions linked to the investment, particularly where such actions lead to significant harm in the host state.Footnote 57 Importantly, the Protocol obliges state parties to amend their domestic legal frameworks to facilitate these remedies, including provisions for conflict of laws and the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments.Footnote 58 Second, the Morocco-Nigeria BIT has shaped the Netherlands’ Draft Model BIT, which mirrors similar language and principles. It mandates that investors ‘shall be liable in accordance with the rules concerning jurisdiction of their home state for acts or decisions made in relation to the investment where such acts or decisions lead to significant damage, personal injuries, or loss of life in the host state.’Footnote 59

While these developments indicate progress, none of these documents has yet been practically adopted. The Morocco-Nigeria BIT and the AfCFTA Protocol are still awaiting ratification by member states, while the Netherlands’ Draft Model BIT remains to be formalised in an actual agreement. Although these efforts demonstrate a promising shift towards procedural remedies within IIL, they fall short of addressing the structural imbalance that the system creates. A significant limitation is that rightsholders are still subjected to a pre-determined jurisdiction for seeking remedies, rather than being granted the autonomy to choose a forum most suitable to their claims. This includes the host state, where the violations occurred and where justice may be more contextually appropriate and accessible. Without such a choice, the imbalance in the transnational legal system remains fundamentally unaddressed.

B. Challenges in Host State Litigation

In many cases, the host state’s legal system emerges as the most practical forum for rightsholders seeking remedies for human rights violations, particularly when the host state is not complicit in facilitating such violations.Footnote 60 First, since the alleged harm typically occurs within the host state, proving human rights violations often necessitates access to relevant evidence located within its jurisdiction. The collection and examination of evidence, including witness testimony and physical records, are inherently more feasible within the territorial boundaries of the host state.Footnote 61 Second, pursuing civil litigation in the victims’ own state can significantly reduce the financial burden on rightsholders, many of whom lack the resources to engage in costly transnational litigation.Footnote 62 These factors collectively underscore the potential advantages of host state litigation as a means of providing victims with accessible and effective remedies. However, the cases of Union Carbide in Bhopal and Chevron in Ecuador (discussed below) highlight the significant challenges that persist even when litigation is pursued in host state courts. These challenges primarily include issues related to establishing jurisdiction and enforcing judgments against multinational corporations, which often operate through intricate and opaque legal structures.

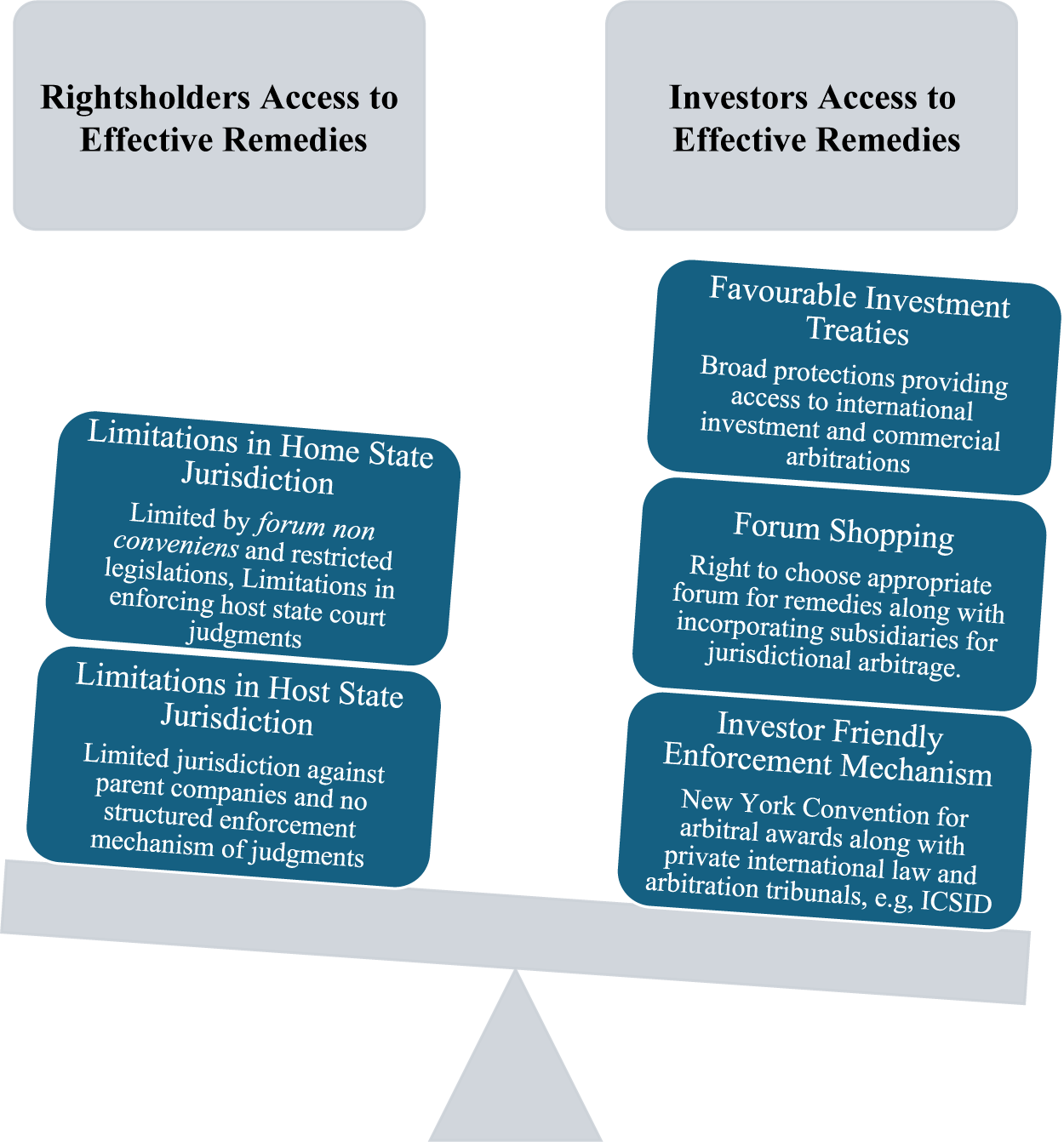

The Supreme Court of India, in its March 2023 judgment in Union of India v Union Carbide Corporation,Footnote 63 revisited the 1991 approval of the settlement agreement between Union Carbide and the Government of India.Footnote 64 The Court acknowledged the rationale behind its earlier approval, emphasising that the settlement was influenced by the limited financial capacity of Union Carbide’s Indian subsidiary, which was valued at 1,000 million Indian Rupees (about US$11.3 million).Footnote 65 Any judgment exceeding this amount would have necessitated enforcement in courts in the USA against the parent company.Footnote 66 The Court underscored the practical barriers to execution on the grounds of ‘due process’ in the USA, as there are significant differences in procedural as well as substantive laws of both states. These disparities in laws make sure that a domestic court will not have jurisdiction over a foreign parent company even if the host state were to enact laws to regulate its conduct.Footnote 67

Another notable example of jurisdictional challenges in home states and enforcement of host state judgments is the long-standing litigation against Texaco (later Chevron) initiated by Indigenous communities in Ecuador. The plaintiffs alleged severe environmental degradation and multiple human rights violations resulting from Texaco’s oil extraction activities. Initially, courts in the USA refused jurisdiction, applying the doctrine of forum non conveniens, on the basis that Ecuadorian courts were better suited to hear the claims. Similar to the Bhopal case, Texaco was compelled to submit to Ecuadorian jurisdiction under the condition that any Ecuadorian judgment could be executed in the USA.Footnote 68 However, unlike Bhopal, no settlement agreement was reached, and plaintiffs proceeded to file a case in Ecuadorian courts in 2003.Footnote 69 In 2011, an Ecuadorian court ordered Chevron to pay approximately USD20 billion in reparations,Footnote 70 a figure later reduced to USD9.5 billion in 2013.Footnote 71 Since Chevron no longer held assets in Ecuador, the plaintiffs pursued enforcement actions in various jurisdictions, including the USA, Canada, Argentina and Brazil, where Chevron had subsidiaries. All these courts rejected enforcement on multiple grounds, including allegations of corrupt practices during the Ecuadorian trial.Footnote 72 A consistent barrier to enforcement was the separate corporate entity doctrine, with courts’ ruling that Chevron’s subsidiaries were legally distinct from its USA-based parent company,Footnote 73 a position that corporations often refute when seeking to invoke jurisdiction for ISDS claims. Simultaneously, Chevron pursued an arbitral claim against Ecuador, resulting in an award that effectively restrained Ecuador from enforcing its domestic court judgment against Chevron.Footnote 74 This case starkly illustrates the dual barriers victims face, the refusal to enforce judgments due to procedural and corporate structuring arguments and the systemic use of ISDS mechanisms to undermine host state judicial outcomes. These dynamics highlight the structural imbalance in the international legal framework, which prioritises corporate protection over accessible remedies for the rightsholders (as shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Structural imbalance in access to remedies.

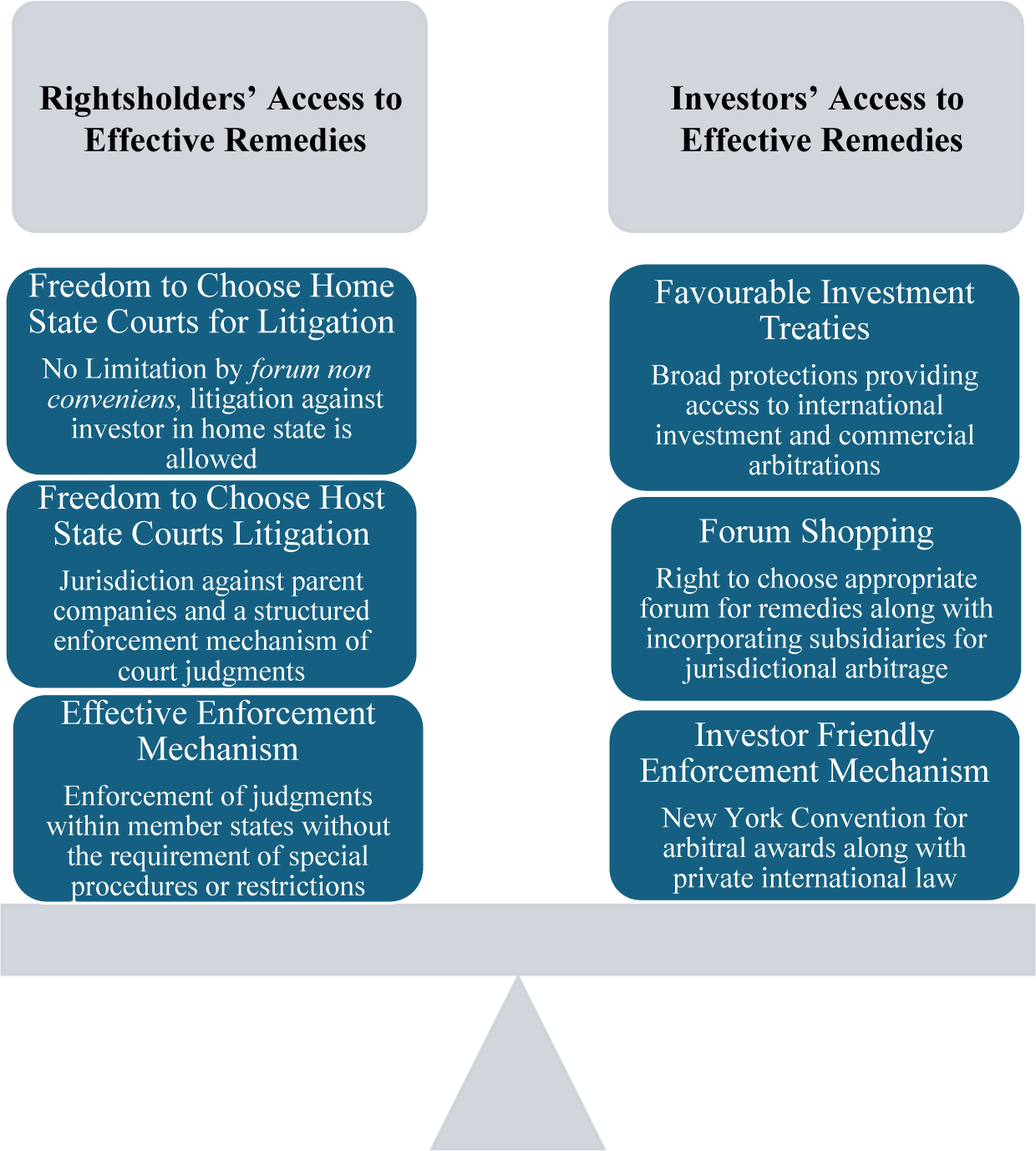

C. Balancing the Structure Through Equitable Remedies

The structural imbalance in the IIL necessitates reforms within the IIAs to bridge the gap between investor privileges and rightsholder remedies. This imbalance is deeply rooted in transnational legal systems, including national laws, but originates with the favourable investment treaties designed primarily to protect investors. Since IIL is fundamentally based on the principle of reciprocity, as reflected in the BITs, it may serve as one of the relevant platforms for addressing this imbalance. Consequently, the process of reducing this inequity must begin with reforms to investment treaties. Two primary challenges must be addressed within IIAs to ensure equitable access to justice: first, the establishment of jurisdiction for courts to hear claims against foreign investors, and second, the enforcement of judgments against investors in home states.

1. Establishing Jurisdiction of Courts

The establishment of jurisdiction for courts in either the home or host state under an IIA must align with the definition of ‘investor’ within the agreement. Investment treaties typically define a legal person as an investor based on factors such as the country of incorporation, the corporate seat,Footnote 75 and, less frequently, the country of control.Footnote 76 If investors can invoke IIAs to establish the jurisdiction of arbitral tribunals over their claims, then rightsholders, particularly those harmed by the activities of these investors, should also have some form of corresponding access to transnational remedies against such entities. In this context, including an access to remedy clause in IIAs could establish new avenues through which rightsholders may seek redress for harms caused by foreign investors. Such clauses, though not yet common in IIAs, would aim to address current asymmetries by explicitly granting affected individuals and communities standing to bring claims against investors, creating two significant possibilities. First, an access to remedy clause will enable affected individuals and communities to access courts in either the home or host state, empowering them, not judges, to select the most suitable forum for redress, thereby removing concerns of judicial imperialism in determining the appropriate forum. This is crucial given that local communities, despite bearing the brunt of foreign investment projects, remain ‘invisible’ within the international investment regime.Footnote 77 Second, such a clause will address the issue of forum non conveniens in home state courts, ensuring rightsholders are not excluded from pursuing claims due to jurisdictional barriers. Additionally, it will streamline the judicial process by reducing the time judges spend determining jurisdiction in such cases, which can often take years.Footnote 78 To address such delays, many states have already entered into international treaties to facilitate international cooperation with respect to legal assistance (e.g., regarding the taking of evidence) and enforcement of judgments in private law cases with a cross-border element.Footnote 79 Similarly, IIAs could be reformed to incorporate access to remedy clauses that include provisions for legal cooperation in BHR cases. Such clauses would support national courts in overcoming procedural obstacles and strengthen the transnational enforceability of judicial remedies for rightsholders. A proposed model clause for IIAs is as under:

Each contracting party agrees that an investor shall be liable in accordance with the rules concerning civil jurisdiction of their home state or host state for acts or decisions made in relation to the investment where such acts or decisions lead to violation of human rights or environmental damage according to the international law applicable on the host state. The victims of any such violations shall have the autonomy to select the forum most suitable to their claims. The courts of the contracting parties shall cooperate and establish mechanisms for mutual assistance to facilitate collection of evidence and ensure judicial efficiency in handling such claims.

2. Enforcement of Judgments

In Hilton v Guyot (1895) the US Supreme Court observed: ‘It is not an admitted principle of the law of nations that a state is bound to enforce within its territories the judgments of a foreign tribunal. Several of the continental nations … do not enforce the judgments of other countries, unless where there are reciprocal treaties to that effect.’Footnote 80

These words underline the foundational principle that the enforcement of foreign judgments historically relies on reciprocal treaties between states. Over time, such treaties have contributed to the development of private international law and conflict of laws. For instance, within the European Union (EU), the Brussels I Regulation harmonises the recognition and enforcement of judgments across member states, ensuring predictability and efficiency.Footnote 81 Under this framework, a judgment rendered in one member state is automatically recognised in others without requiring a special procedure.Footnote 82 The Lugano Convention extends similar principles to certain non-EU countries, such as Norway and Switzerland, enhancing mutual recognition and enforcement.Footnote 83 Internationally, the Hague Convention on Choice of Court Agreements 2005 provides an essential framework for the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters.Footnote 84 However, the Convention’s application is limited to cases where a prior choice of court agreement exists between the parties.Footnote 85 Similarly, the Hague Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil or Commercial Matters 2019 requires consent of the defendant to the jurisdiction of the court,Footnote 86 which the transnational corporations are unlikely to do so and thereby excluding tort claims by victims of human rights violations. For such cases, enforcement mechanisms must be grounded in public law rather than private contractual frameworks.

In public international law the recognition and enforcement of judgments and arbitral awards in transnational commercial disputes is well established. One primary reason for the widespread preference for international arbitration is the relative ease of enforcing arbitral awards across borders.Footnote 87 The UN Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards 1958 serves as a foundational instrument, ensuring widespread enforceability of arbitral awards in over 170 contracting states.Footnote 88 The Inter-American Convention on Extraterritorial Validity of Foreign Judgments and Arbitral Awards similarly provides a regional framework for enforcement, though its application remains more limited.Footnote 89 The legal instruments provide one significant disparity, i.e., while businesses can readily access arbitration tribunals to resolve disputes, individuals seeking remedies for human rights violations face structural barriers to accessing such mechanisms.Footnote 90 The existing frameworks of public international law fail to provide equivalent mechanisms for transnational enforcement of judgments in public law claims. This imbalance perpetuates corporate impunity and undermines access to justice for affected communities. Using the principles of reciprocity articulated in Hilton v Guyot, I propose the inclusion of an enforcement of foreign judgments clause within IIAs. Drawing from lessons in private international law, these clauses should enable victims of human rights violations to enforce judgments across borders, particularly against corporations operating transnationally. A proposed model clause in IIAs for enforcement is as under:

Each contracting party shall recognize and enforce final and binding judgments rendered by the courts of the other contracting party concerning claims under [the clause providing jurisdiction]. Such judgments shall be enforceable in the same manner as domestic judgments, subject to [fair trial or due process restrictions may be included by the parties]. Contracting Parties shall also establish mechanisms for mutual assistance in the execution of judgments.

As noted earlier, the failure to enforce the judgment against Chevron exemplifies the significant challenges in securing remedies in BHR litigation. Courts in the Global North have frequently cited procedural shortcomings and concerns over judicial independence in the Global South as reasons for non-enforcement.Footnote 91 Paradoxically, arbitral tribunals, often criticised for corporate bias,Footnote 92 do not face the same scrutiny when their awards favour businesses over states or communities.Footnote 93 This disparity underscores the structural inequities within the global enforcement regime. Rather than relying solely on courts in the Global North to determine enforcement outcomes, litigants should have the autonomy to select judicial forums they trust, regardless of geographic or economic divides.Footnote 94 Empowering the judicial systems of the Global South to handle transnational cases not only promotes equity but also provides an opportunity for these systems to evolve, earning greater trust and legitimacy over time (see Figure 3 showcasing a balanced approach).Footnote 95

Figure 3. A balanced approach to access to remedies.

IV. Conclusion

This article has argued that structural imbalances in IIL are not incidental but embedded in the very design of IIAs, which privilege investor protections while leaving rightsholders without comparable access to justice. By revisiting examples such as Chevron, Bhopal, and DBCP, it has been illustrated how the absence of effective transnational remedies perpetuates legal imperialism. Against this backdrop and building on the 2021 UNWG report, the article has advanced a normative proposal to include the access to remedy clauses in IIAs as an effort for rebalancing the system.

The contribution here is twofold. First, it repositions IIAs, which are long viewed as central to the problem, as potential tools for addressing the very asymmetries they have entrenched. Second, it shifts attention beyond procedural reform of ISDS to a more structural reorientation that centres rightsholders. Admittedly, this is a normative argument, and political feasibility remains uncertain, particularly given the reluctance of capital-exporting states to dilute protections for their investors. Yet the persistence of BHR debates underscores a central truth: that if IHRL mechanisms had sufficed to deliver remedies, the BHR agenda would not exist. Precisely because IIAs have proven so effective for investors, they also represent an inevitable site for corrective reform.

Finally, the article raises broader questions for future research. Rightsholders’ access to remedy might also be explored through parallel instruments, including the prospective BHR treaty. Equally, proposals for incorporating remedy clauses into IIAs warrant closer scrutiny from the perspective of private international law, to assess how such provisions might be operationalised in practice. Without such interdisciplinary inquiry, efforts to dismantle the entrenched asymmetry between capital and communities risk remaining largely aspirational.

Competing interests

The author declares none.