Highlights

Up to 60% of LVO stroke patients are first seen at a PSC before transfer for EVT.

One-third experienced ASPECTS decay during the transfer, which is associated with poor outcomes.

Collateral blood flow was the key factor. Collateral assessment may help predict outcomes and guide studying therapies in this group.

Introduction

Multiple randomized controlled trials provide evidence for substantial improvement in functional outcomes after endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) in patients with large vessel occlusion (LVO) up to 24 hours from stroke onset. Reference Goyal, Menon and van Zwam1–Reference Albers, Marks and Kemp3 Although the benefits of EVT have been recently demonstrated even in patients with a large infarction core, the extent of the infarction before EVT has been one of the determinants for functional outcomes following thrombectomy. Reference Yoshimura, Sakai and Yamagami4–Reference Bendszus, Fiehler and Subtil7 A common imaging score for this purpose is the Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) – a 10-point quantitative topographic CT scan score to assess the extent of early ischemic changes in 10 distinct anterior circulation brain regions. Reference Barber, Demchuk, Zhang and Buchan8 Patients with a higher ASPECTS score were found to have a favorable outcome following thrombectomy compared to patients with lower scores. Reference Hill, Demchuk and Goyal9

Stroke is a dynamic process. After arterial occlusion, there is a continuous expansion of the ischemic core volume, which determines infarct growth rate. Reference Goyal, Menon and van Zwam1,Reference Saver, Goyal and van der Lugt10–Reference Hossmann12 The pace of infarct growth is variable. For example, patients with poor collateral circulation are more likely to have fast growth resulting in large infarcts within a short period of time, while others with robust collateral circulation will have slower progression resulting in small infarcts over a long period of time. Reference Christoforidis, Mohammad, Kehagias, Avutu and Slivka13–Reference Liebeskind15 The rate of infarct growth can be estimated using imaging by comparing the extent of ischemic changes, for example, using ASPECTS, on a subsequent scan compared to a baseline scan. This phenomenon of relative worsening of the ASPECTS over time has been referred to as ASPECTS decay. Reference Sun, Connelly and Nogueira16

Up to 60% of patients with acute ischemic stroke and LVO are initially assessed at a primary stroke center (PSC) before being transferred to a comprehensive stroke center (CSC) for EVT. Reference Gerschenfeld, Muresan and Blanc17 ASPECTS decay during inter-hospital transfers is responsible for excluding up to 33% of transferred patients from getting EVT once they arrive at the CSC. Reference Mokin, Gupta, Guerrero, Rose, Burgin and Sivakanthan18 The incidence of ASPECTS decay during the interfacility transfers, its relation to collaterals and its role in influencing functional status and infarct growth have not been widely examined. We analyzed provincial registry data to determine the incidence, predictors and outcomes of ASPECTS decay during interfacility transfer for EVT.

Methods

Study design

The present study was a retrospective analysis of prospectively acquired provincial registry data (Quality Improvement and Clinical Research “QuICR”) within the province of Alberta, Canada. Reference Kamal, Jeerakathil and Stang19

Study population

Between October 2015 and September 2020, we included all patients with acute ischemic stroke symptoms within 24 hours from onset/last known well and evidence of LVO in internal carotid artery (ICA), M1-segment middle cerebral artery (MCA) and/or proximal M2-segment MCA at PSCs in Northern Alberta and transferred to the CSC in the University of Alberta Hospital in Edmonton for EVT. We included eligible patients even if EVT was not ultimately performed. Patients with posterior circulation stroke, medium vessel occlusion (distal M2-segment and beyond MCA occlusions or anterior cerebral artery), suspected chronic occlusions, lack of baseline CT at PSC or lack of repeated CT at CSC and poor quality CT that precluded objective ASPECTS assessments were excluded.

Baseline characteristics include age, sex, comorbidities, baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores, intravenous thrombolysis therapy, mode of transportation, interval time between CTs at PSCs and CSCs, whether EVT was performed and reasons if not, 90-day home time and mortality were collected.

The research protocol was approved by our local Human Research Ethics Board.

Imaging variables

All baseline CT, CTA, CT perfusion, digital subtraction angiography and follow-up MRI and/or CT were included and interpreted by consensus of three study team members (AA, NI, AW). We collected ASPECTS, presence of hyperdense vessel sign, site of occlusion, collateral score, interval recanalization, whether CT perfusion was performed, final thrombolysis in cerebral infarction score and presence of hemorrhagic transformation (HT) in follow-up imaging. The degree of intracranial collateral flow was assessed using a single-phase CTA. The degree of intracranial collateral flow was defined using Maas and colleagues’ rating modified scale as follows: 1, absent collateral blood flow or less than 50% of the MCA territory (no or poor); 2, collateral blood flow less than that on the contralateral side but more than 50% of the MCA territory (moderate); 3, collateral blood flow equal to that on the contralateral side (adequate); and 4, collateral blood flow greater than that on the contralateral side (augmented). Reference Maas, Lev and Ay20 A visual illustration of the collateral grading system was demonstrated by Boulouis G et al. Reference Boulouis, Lauer and Siddiqui21 HT on follow-up MRI and/or CT was graded using European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS) criteria Reference Fiorelli, Bastianello and von Kummer22 : hemorrhagic infarction type 1 (HI1; small petechiae along the margins of the infarct), hemorrhagic infarction type 2 (HI2; confluent petechiae within the infarcted area but no space-occupying effect), parenchymal hemorrhage type 1 (PH1; hematoma in 30% or less of the infarcted area with some slight space-occupying effect) or parenchymal hemorrhage type 2 (PH2; hematoma in more than 30% of the infarcted area with substantial space-occupying effect). Three neurologists (A.A., N.I., A.W.) blinded to clinical details assessed all the scans separately.

Endpoints

ASPECTS decay was defined as ≥ 2 ASPECTS points decrement using the following equation: ASPECTS at PSC – ASPECTS at CSC at arrival, similar to the previous study. Reference Abdulrazzak, Greco, Azher, Qadri, Shaker and Pujara23 A similar definition was used to identify rapid infarct progression in another study. Reference Reddy, Friedman and Wu24 Patients were dichotomized into those with versus without ASPECTS decay. The clinical and imaging variables between the two groups were analyzed. The primary outcome was 90-day home time, which is a validated, objective and easy interpreted patient-centered outcome, defined as the total number of nights in pre-morbid living status in the 90 days post stroke admission. Reference Yu, Rogers and Wang25–Reference Fonarow, Liang and Thomas27 The distribution of home time was also reported as the following: (85–90 days, 70–84 days, 40–69 days, 1–39 days, 0 days–no death and mortality). The other endpoints were the ASPECTS point decrease per hour, time metrics, HT and mortality.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 28.0.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics Inc., 2015, Armonk, NY, USA). Baseline characteristics were reported by mean and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables with normal distribution, median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables with skewed distribution and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Differences between groups were assessed using independent t-tests for parametric data and Mann–Whitney U tests for nonparametric data. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to determine the relationship between the ASPECTS point decrease per hour and collateral scores. A linear regression model was used to determine the association between the ASPECTS point decrease per hour and 90-day home time and between performing EVT and 90-day home time in patients with ASPECTS decay. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were used to determine factors that are independently associated with ASPECTS decay and outcomes. The distribution of outcomes was assessed with Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

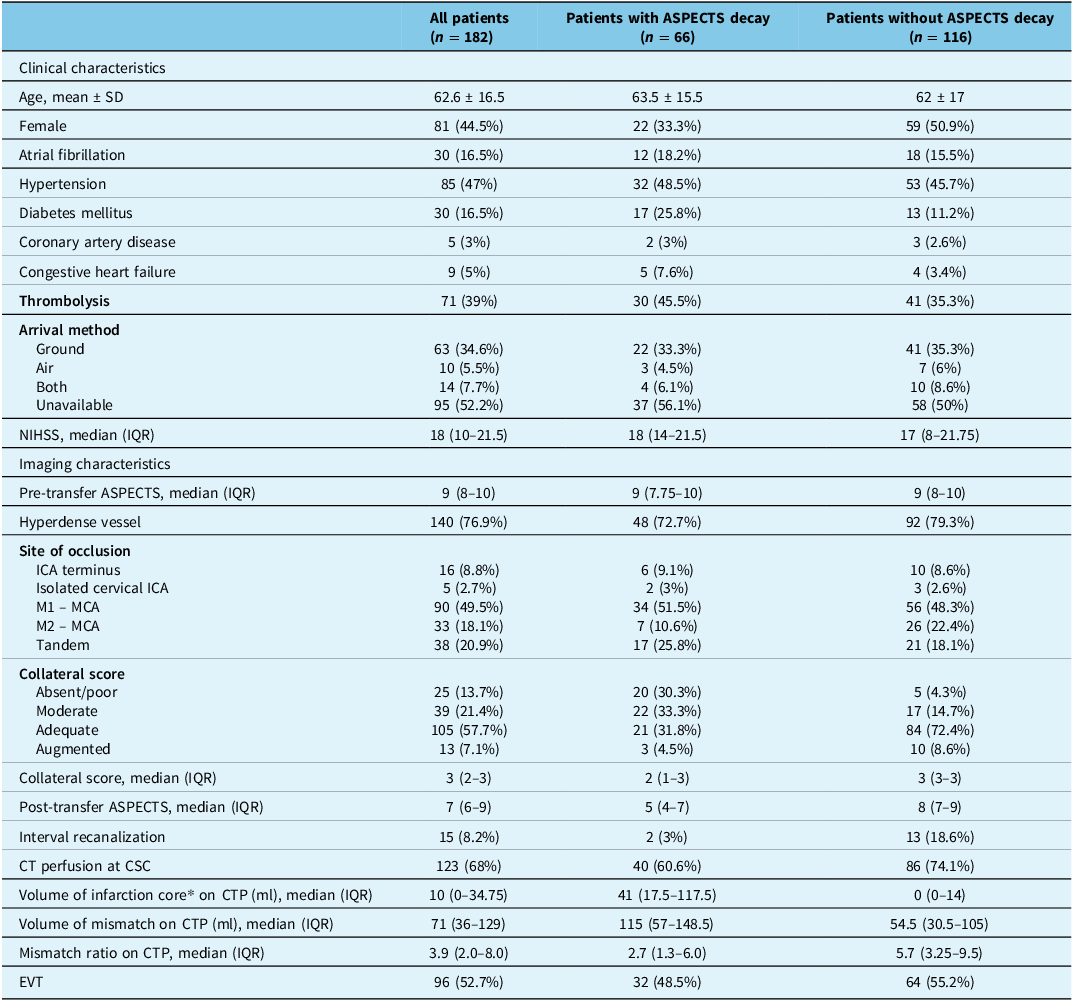

Between October 2015 and September 2020, out of 394 patients who presented with LVO to a PSC, 182 (44.5% female) transferred patients met the inclusion criteria (Supplementary Figure 1). The mean (SD) age was 62.6 (16.5) years, and 85 (47%) patients had hypertension. All patients had single-phase CTA at their PSCs prior to transfer. Among the 182 patients, 71 (39%) received thrombolysis prior to interfacility transfer. PSC-defined occlusions on CTA were in the ICA terminus in 16 (8.8%), isolated cervical ICA in 5 (2.7%), M1 MCA in 90 (49.5%), M2 MCA in 33 (18.1%) and tandem occlusions in 38 (20.9%) patients. Median (IQR) baseline NIHSS was 18 (10–21). The median time from last seen normal time to PSC triage was 96 (52–214.5) minutes, and the median time between baseline CT and subsequent CT upon arrival to CSC was 250 (163–324) minutes. Median (IQR) pre-transfer ASPECTS was 9 (8–10), collateral score 3 (2–3), subsequent ASPECTS 7 (6–9) and the median ASPECTS change was 1 (0–2) point. The transfer method was documented in 48% of patients. Of those, a total of 34.6% were transferred to the CSC via ground, 5.5% were transported by air and 7.7% used both.

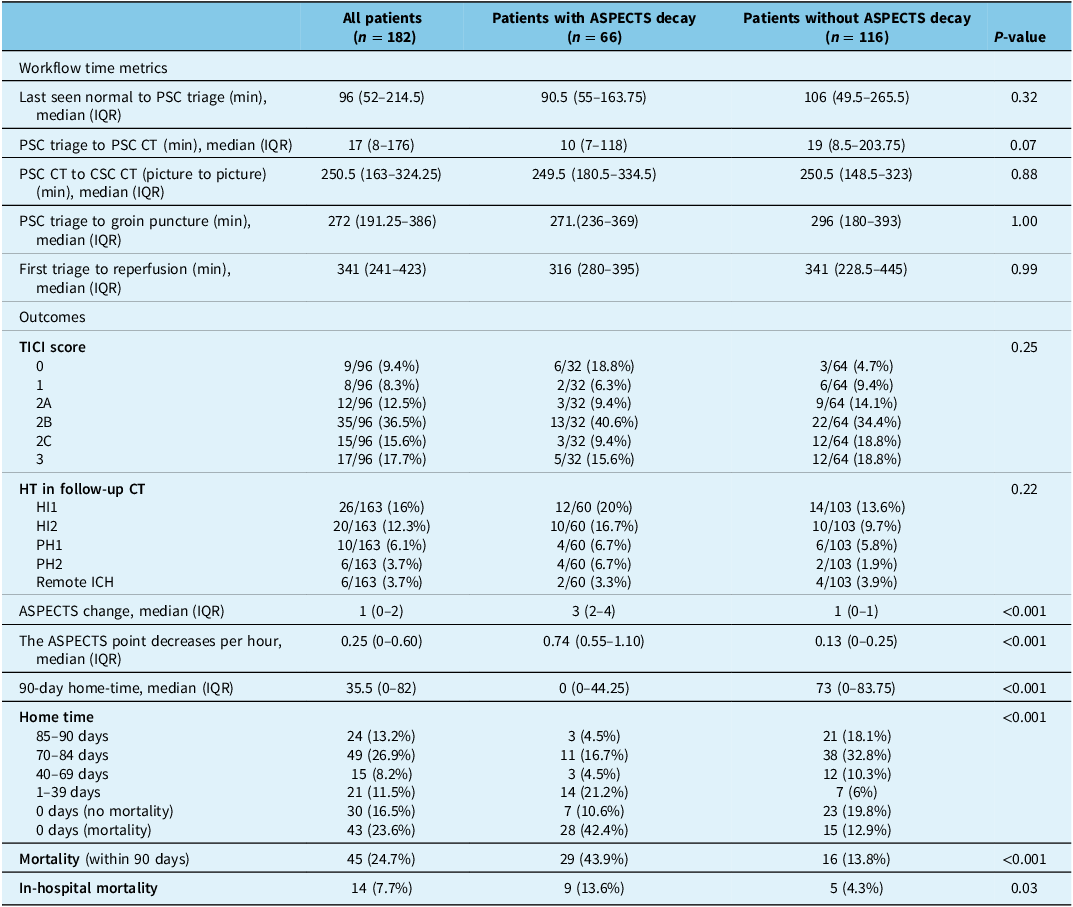

Baseline clinical and imaging characteristics are summarized in Table 1. In this cohort, EVT was not performed in 86 (47%) patients, dominantly due to ASPECTS decay (35 patients) as described by the treating physicians. Other reasons include full recanalization (18 patients), distal migration of thrombus (11 patients), NIHSS improvement upon arrival to CSC (7 patients), no target mismatch on CT perfusion imaging (10 patients), medical instability and/or goals of care changes (2 patients) and access-related technical reasons (3 patients). Among 182 patients, 96 of 182 (52.7%) patients underwent EVT, 66 of 182 (36%) patients had ASPECTS decay and 32 of 66 (48.5%) patients underwent EVT despite ASPECTS decay. Patients with ASPECTS decay had a non-significantly lower probability of receiving EVT (OR = 0.77, [0.42–1.40], p = 0.39. Univariable logistic regression indicated that collateral score (OR = 0.35, [0.21–0.59], p < 0.001) and sex (OR = 0.48, [0.26–0.91], p = 0.023) were both associated with ASPECTS decay, which indicates that a better collateral score and female sex had lower odds to develop ASPECTS drop. However, in multivariable logistic regression, only collateral score remained strongly associated with the ASPECTS decay (OR = 0.29, [0.19–0.46], p < 0.001). The ASPECTS point decrease per hour was inversely correlated with the collateral scores (r = −0.48, [−0.58–0.35], P < 0.001). In univariable logistic regression, age, thrombolysis, baseline hypertension, NIHSS, site of occlusion, presence of dense vessel, mode of transportation, transfer time and baseline ASPECTS were not associated with the ASPECTS decay. With regard to workflow time metrics, there was no difference between patients with and without ASPECTS decay (Table 2).

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics

ASPECTS = The Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score; SD = standard deviation; NIHSS = National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; IQR = interquartile range; ICA = internal carotid artery; MCA = middle cerebral artery; CTP = CT perfusion; CSC = comprehensive stroke center; EVT = endovascular thrombectomy. *Infarction core was measured using RAPID or MIStar defined as cerebral blood flow <30%.

Table 2. Workflow time metrics and outcomes in patients with and without ASPECTS decay

ASPECTS = The Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score; SD = standard deviation; PSC = primary stroke center; IQR = interquartile range; CSC = comprehensive stroke center; TICI = thrombolysis in cerebral infarction; HT = hemorrhagic transformation; HI = hemorrhagic infarction; PH = parenchymal hemorrhage; ICH = intracerebral hemorrhage.

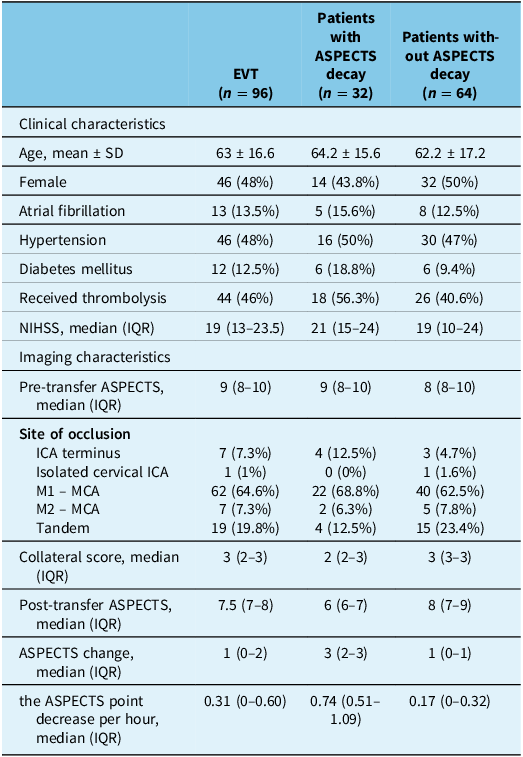

Patients with ASPECTS decay had a significantly lower 90-day home time and higher risk of both 90-day and in-hospital mortality (β = −0.32, [−36.4 – 4.6 ], P < 0.001; OR = 4.9, [2.4 – 10.0], P < 0.001; OR = 3.8, [1.2–12.3], P = 0.03, respectively; Table 2). The rate of ASPECTS decay (the ASPECTS point decrease per hour) was significantly associated with a lower number of days in pre-morbid living status in the 90 days post-onset (β = −0.265, [−25.5–7.7], P < 0.001). Clinical and imaging characteristics for patients who underwent EVT are summarized in Table 3. Among patients who underwent EVT, patients with ASPECTS decay (n = 32) have a significantly worse 90-day home time (P = 0.005; Supplementary Table 1). While the presence of ASPECTS decay was significantly associated with reduced home time, EVT, on the other hand, was not significantly associated with 90-day home time (β = 0.03, P = 0.75), and the interaction between EVT and ASPECTS decay was not significant (β = 0.10, P = 0.36). This suggests that the effect of EVT on functional recovery did not differ significantly between patients with and without ASPECTS decay. There was no difference in workflow time metrics between patients with and without ASPECTS decay (Supplementary Table 1). Patients who experienced ASPECTS decay had a significantly lower likelihood of achieving a favorable 90-day home time (70–90 days) (OR = 0.24, [0.12–0.48], p < 0.001; Figure 1) compared to those without ASPECTS decay.

Figure 1. Home time in patients with/without ASPECTS decay. Home time is dichotomized to 70–90 days versus 0–69 days. The presence of ASPECTS decay was associated with an increased likelihood of poor functional outcomes. OR = odds ratio; ASPECTS = The Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score.

Table 3. Clinical and imaging characteristics for patients who underwent EVT

EVT = endovascular thrombectomy; ASPECTS = The Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score; SD = standard deviation; NIHSS = National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; IQR = interquartile range; ICA = internal carotid artery; MCA = middle cerebral artery.

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis of a province-wide prospective registry, 36% of patients with LVO ischemic stroke who were transferred from PSCs for EVT experienced ASPECTS decay (defined as a ≥2-point drop in ASPECTS). As a result, approximately 19% of patients in this cohort were excluded from receiving EVT. Collateral status was strongly associated with the ASPECTS decay. ASPECTS decay was associated with a higher probability of poor outcomes even when EVT was performed. There was no difference in the workflow time metrics between patients with and without ASPECTS decay. In light of the recent randomized clinical trials demonstrating the benefits of EVT in patients with a large infarction core, the result from this cohort should not be a reason to withhold the thrombectomy. Reference Yoshimura, Sakai and Yamagami4–Reference Bendszus, Fiehler and Subtil7 Instead, it should be informative that ASPECTS decay could be one of the determinants for functional outcomes following thrombectomy.

The majority of patients with LVO ischemic stroke are initially assessed at PSC. Reference Gerschenfeld, Muresan and Blanc17 A change in clinical status – either improvement or deterioration – is observed in approximately 36% of patients during transfer, and its association with functional outcomes was highlighted in a recent study. Reference Seners, Ter Schiphorst and Wouters28 Clinical improvement during transfer was associated with distal occlusion, the use of thrombolysis and lower serum glucose levels. Reference Seners, Ter Schiphorst and Wouters28 In contrast, clinical deterioration was linked to proximal occlusion and higher serum glucose levels. Reference Seners, Ter Schiphorst and Wouters28 Patients with LVO located in remote communities provide a golden opportunity to study infarct growth dynamics and factors affecting the infarct growth over time. Identifying methods for predicting the infarct growth rate and patient outcomes is critical to study the pathophysiology behind stroke evolution and optimize the quality of health care by prioritizing the transfer of such patients. Unfortunately, there is little known about active methods to slow the ASPECTS decay such as neuroprotectants and any effects of controlling blood pressure and glucose. A similar finding was described previously in another study, Reference Boulouis, Lauer and Siddiqui21 which highlights the role of collaterals in determining the rate of stroke evolution. Reference Shuaib, Butcher, Mohammad, Saqqur and Liebeskind29,Reference Miteff, Levi, Bateman, Spratt, McElduff and Parsons30 Although a similar study found that lower baseline ASPECTS and higher NIHSS were associated with the ASPECTS decay, we did not establish this relationship in our study. Reference Boulouis, Lauer and Siddiqui21 In our study’s univariable logistic regression analysis, we found that men had higher odds of experiencing an ASPECTS decline compared to women. However, this association became insignificant in the multivariable logistic regression. In contrast, another study reported that ASPECTS decay was more likely to occur in females, though this too lost significance in multivariable analysis. Reference Boulouis, Lauer and Siddiqui21 While there is limited data directly linking sex differences to collateral status and/or ASPECTS decline, a few clinical studies have suggested that women tend to have better collateral circulation than men. Reference van der Meij, Holswilder and Bernsen31,Reference Lagebrant, Ramgren, Hassani Espili, Maranon and Kremer32 In our study, collateral scores were similar between sexes; however, men had lower baseline ASPECTS, longer transfer times, and a higher incidence of tandem occlusions.

A recent report from the American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines-Stroke registry has highlighted the increase in time in acute stroke transfers at 174 minutes, Reference Stamm, Royan, Giurcanu, Messe, Jauch and Prabhakaran33 which is longer than current recommendations of 120 minutes. Reference Alberts, Wechsler and Jensen34 While there is no clear local Canadian consensus on the recommended time for acute stroke transfers, the median time of 250.5 minutes from PSC CT to CSC CT shown in our study calls for quality improvement initiatives in the emergency transport system. Acknowledging that point, distances between PSCs and the CSC in northern Alberta can be more than 700 km, which would make a 120-minute transfer practically impossible even with air transport. Our study also highlights the issue of unequal access to similar resources in health care in rural and urban areas. About 47% of patients with LVO who were transferred from PSCs to CSC with the intention to treat by EVT were not eligible for the treatment upon arrival, mostly due to ASPECTS decay. A similar finding was reported in the Madrid Stroke Network, where 41% of patients did not receive EVT ultimately due to infarction progression during interfacility transfer. Reference Fuentes, Alonso de Lecinana and Ximenez-Carrillo35 Delay in interfacility transfer has been shown to be a main reason for patients with LVO ischemic stroke not receiving thrombectomy. Reference Prabhakaran, Ward and John36 With 93% of the Alberta population living within a 6-hour drive from a stroke center, Reference Eswaradass, Swartz, Rosen, Hill and Lindsay37 our results represent an opportunity by suggesting that collateral assessment in patients with LVO located in PSCs could be considered as one of the factors in studying therapeutic interventions such as neuroprotectants in this patient population.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations, including the single CSC, retrospective analysis and relatively small sample size. In addition, the study used ASPECTS scoring to assess for the decay; however, this scoring system can only serve as a surrogate for infarction progression rather than a volumetric assessment. In addition, there was limited information on the mode of transportation in 52% of patients in the registry due to a transition from paper to electronic records.

Conclusion

For patients with LVO who were transferred for thrombectomy, a third developed ASPECTS decay, impacting their eligibility for the procedure. Collateral status was the main determinant of ASPECTS decay. The ASPECTS point decrease per hour during interfacility transfers is strongly associated with functional outcomes. Patients with ASPECTS decay were less likely to be offered EVT, and even when EVT was performed, it did not influence the functional status. Collateral assessment could inform triage decisions to CSCs and be considered as a predictor in studying promising therapies in this patient population.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2025.10421.

Acknowledgments

AA thanks King Saud University and the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Education for Residency and Fellowship funding. AA thanks the University of Alberta Hospital Foundation and the Neuroscience and Mental Health Institute for the Neurology Fellowship Award.

Author contributions

AA: Conceptualization, methodology, data acquisition, image analysis, statistical analysis, writing – original draft. NI: Data acquisition, image analysis, data management, writing – review and editing. AW: Data acquisition, image analysis, data management, writing – review and editing. TJ: Conceptualization, supervision, writing – review and editing. BB: Conceptualization, supervision, writing – review and editing. AS: Conceptualization, supervision, writing – review and editing. MDH: Conceptualization, supervision, writing – review and editing. MA: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, data acquisition, writing – review and editing. SM: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, data acquisition, writing – review and editing.

Funding statement

None.

Competing interests

AA: None. NI: None. AW: None. TJ: None. BB: None. AS: None. MDH: Grants or contracts from any entity – NoNO Inc. Grant to the University of Calgary for the ESCAPE-NA1 trial, ESCAPE-NEXT trial; Canadian Institutes for Health Research Grant to the University of Calgary for the ESCAPE-NA1 trial, ESCAPE-NEXT trial; Medtronic Grant to the University of Calgary for the ESCAPE-MeVO study; Canadian Institutes for Health Research Grant to the University of Calgary for the TEMPO-2 trial; Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada Grant to the University of Calgary for the TEMPO-2 trial. Consulting fees – Sun Pharma Brainsgate Inc. Paid work for adjudication of clinical trial outcomes. Patents planned, issued or pending – US Patent 62/086,077 Licensed to Circle NVI; US Patent 10,916,346 – Licensed to Circle NVI. Participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board – DSMC Chair Oncovir Hiltonel trial (end 2023); DSMC Chair DUMAS trial (end 2023); DSMB member ARTESIA trial (end 2023); DSMB member BRAIN-AF trial (end 2023); DSMB member LAAOS-4 trial (ongoing). Leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group, paid or unpaid – President, Canadian Neurological Sciences Federation (not for profit). Stock or stock options – Circle Inc., Basking Biosciences Private stock ownership. MA: None. SM: None.

Target article

Predictors and Outcomes of ASPECTS Decay during Interfacility Transfers in Patients with Large Vessel Occlusion

Related commentaries (1)

Reviewer Comment On Alrohimi et al. “Predictors and Outcomes of ASPECTS Decay during Inter-Facility Transfers in Patients with Large Vessel Occlusion”