Introduction

Members of social minorities often face obstacles that hinder their political participation, leading to lower levels of political engagement (Banducci et al., Reference Banducci, Donovan and Karp2004; Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Heath, Fisher and Sobolewska2014; Verba & Nie, Reference Verba and Nie1972). Recent literature suggests that the shared experience of being discriminated against can, under certain conditions, enhance political participation among individuals belonging to social minorities (Dawson, Reference Dawson1995; Sanchez & Vargas, Reference Sanchez and Vargas2016). This holds especially true if minority group interests enter the political agenda and are advocated by a viable political force (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Lajevardi, Lindgren and Oskarsson2022; Chong & Kim, Reference Chong and Kim2006; Rocha et al., Reference Rocha, Tolbert, Bowen and Clark2010; Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Heath, Fisher and Sobolewska2014). Members of sexual and gender minorities, a group that includes lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgender people and other sexual and/or gender‐nonconforming (LGBT+) personsFootnote 1 appear to be no exception from this rule. In contexts where LGBT+ group interests are on the political agenda, LGBT+ voters are shown to be more likely than comparable heterosexual‐ and/or cisgender counterparts to engage in different forms of political action (Albaugh et al., Reference Albaugh, Harell, Loewen, Rubenson and Stephenson2023; Bowers & Whitley, Reference Bowers and Whitley2020; Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Nuño‐Pérez and Sanchez2019; Perrella et al., Reference Perrella, Brown and Kay2012; Swank & Fahs, Reference Swank and Fahs2019; Turnbull‐Dugarte & Townsley, Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte and Townsley2020). However, we do not yet know what happens to these positive participation gaps in contexts where key LGBT+ empowering laws – like the right to marry, self‐determine gender or adopt children – have been enacted (Guntermann & Beauvais, Reference Guntermann and Beauvais2022). Do the gaps disappear as expected by some of the existing literature on minority political participation (Chong & Kim, Reference Chong and Kim2006; Leighley & Nagler, Reference Leighley and Nagler2014) or do they persist? To shed light on this important question, this paper offers a pioneering longitudinal analysis of sexuality‐driven disparities in voter turnout in Sweden, which is one of the frontrunners in the protection of LGBT+ rights. With access to comprehensive and verified data encompassing the entire Swedish population, the study offers highly accurate analyses of potential sexuality‐driven differences in voter turnout.

Despite notable progress made in recent years in the field of political participation among sexual and gender minorities, several gaps remain (Ayoub, Reference Ayoub2022). First, most existing studies concentrate on individual, high‐salience elections, potentially capturing temporary spikes in electoral mobilization (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Rogers and Sherrill2011; Perrella et al., Reference Perrella, Brown and Kay2012; Turnbull‐Dugarte, Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte2020a). Furthermore, the majority of existing studies rely on self‐reported survey data which could potentially be affected by the underreporting of individuals’ sexual‐ and/or gender identities (Coffman et al., Reference Coffman, Coffman and Ericson2017; Egan, Reference Egan2012; Pathela et al., Reference Pathela, Hajat, Schillinger, Blank, Sell and Mostashari2006; Sell et al., Reference Sell, Kates and Brodie2007). This paper addresses both of these gaps. Using civil‐status and parenthood data from Swedish administrative records, the study identifies a sample of 16,000 lesbians, gays and bisexuals (LGB) who are either married, formally partnered or co‐parenting (Kolk & Andersson, Reference Kolk and Andersson2020). This sample size is notably larger than what has been seen in previous literature. Furthermore, we are able to link this sample to verified, individual‐level turnout data, thus avoiding some of the challenges associated with relying on self‐reported measures of political participation (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Lajevardi, Lindgren and Oskarsson2022).

To examine potential sexuality‐driven disparities in voter turnout within the context of robust LGBT+ rights protection, the study considers four Swedish electoral contests held after the enactment of same‐sex marriage in 2009: the 2009 and 2019 European Parliament elections (EP), as well as the 2010 and 2018 general elections. This selection encompasses different types of elections with varying overall turnout rates, contributing to a thorough and comprehensive examination of potential sexuality‐driven disparities in voter turnout (Just, Reference Just2017). The results are obtained using propensity score matching and fixed‐effects regression analyses, wherein we compare the likelihood of participating in elections among the identified LGB individuals to a suitable counterfactual group. Specifically, this counterfactual group consists of individuals who are either married to or co‐parenting with a person of a different sex.

The findings consistently indicate a positive disparity in voter turnout between LGB individuals and comparable heterosexual counterparts across the four elections, pointing to a mobilization of the LGB electorate that shows no tangible signs of abating. We find that this sexuality gap is not sensitive to differences in age, income, education, sex, place of residence or family situation. Importantly, we show that this gap did not manifest itself prior to the enactment of core LGBT+ policies, in 1982 and 1994, pointing to the potential significance of minority rights protection as a mechanism for ensuring enduring inclusion of social minority groups in democratic action. These findings make a notable contribution to our understanding of political engagement among non‐heterosexual individuals, as they demonstrate that the expansion of LGBT+ rights does not necessarily result in reduced political participation among this group of voters (Dawson, Reference Dawson1995; Just, Reference Just2017; Leighley & Nagler, Reference Leighley and Nagler2014). Furthermore, the innovative method employed to identify LGB individuals within a population registry holds potential value for other fields confronting a dearth of reliable data on sexual minorities (Ayoub, Reference Ayoub2022).

Linked fates and political participation of minorities

The study of determinants of political participation is a central focus within political science (Banducci et al., Reference Banducci, Donovan and Karp2004; Verba & Nie, Reference Verba and Nie1972). Past literature underscores that members of social minority groups face multiple barriers to political engagement (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Lajevardi, Lindgren and Oskarsson2022; Banducci et al., Reference Banducci, Donovan and Karp2004; Rocha et al., Reference Rocha, Tolbert, Bowen and Clark2010; Rosenthal et al., Reference Rosenthal, Zubida and Nachmias2018; Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Heath, Fisher and Sobolewska2014). These barriers span systemic aspects like electoral system types (Just, Reference Just2017; Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Heath, Fisher and Sobolewska2014), lack of descriptive representation (Rocha et al., Reference Rocha, Tolbert, Bowen and Clark2010) or inadequate access to polling stations in minority neighbourhoods (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Lajevardi, Lindgren and Oskarsson2022), but also individual barriers, such as lower educational attainment or socioeconomic status (Persson et al., Reference Persson, Sundell and Öhrvall2014; Verba & Nie, Reference Verba and Nie1972). Consequently, social minority groups often display lower political participation rates across various political contexts (Just, Reference Just2017; Rocha et al., Reference Rocha, Tolbert, Bowen and Clark2010). This includes voting in elections, which is one of the least resource‐intensive forms of political engagement (Just, Reference Just2017). However, past research also indicates that minority voters can mobilize when issues relevant to their group interests become politically salient and are championed by a viable political force. The linked fates theory, used to account for this phenomenon, posits that a collective experience of discrimination fosters a sense of shared identity among members of social minority groups (Austin et al., Reference Austin, Middleton and Yon2012; Dawson, Reference Dawson1995; Just, Reference Just2017; Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Nuño‐Pérez and Sanchez2019; Sanchez & Vargas, Reference Sanchez and Vargas2016). This shared identity can potentially enhance minority political participation by instigating a form of ‘oppositional consciousness’ and fostering a strong sense of common belonging among members of social minority groups (Austin et al., Reference Austin, Middleton and Yon2012; Just, Reference Just2017; Leighley & Nagler, Reference Leighley and Nagler2014). Within the realm of political participation, this theory proposes that minority groups abstain or engage in democratic actions based on their perception of advancing their group interests (Dawson, Reference Dawson1995; Just, Reference Just2017; Rosenthal et al., Reference Rosenthal, Zubida and Nachmias2018). If a viable political force champions minority interests, these groups are expected, and in some cases shown, to rally around that force (Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Villarreal and Woods2005). For example, the well‐known ‘Black gap’ in voter turnout in the United States diminished significantly during the civil rights movement and again when Barack Obama emerged as a presidential candidate (Austin et al., Reference Austin, Middleton and Yon2012; Leighley & Nagler, Reference Leighley and Nagler2014). Similarly, Israeli Arabs tend to participate more in local than national elections due to the former being seen as a better means to advance their group interests (Rosenthal et al., Reference Rosenthal, Zubida and Nachmias2018).

The existing empirical evidence on political participation among LGBT+ individuals is in line with the ‘linked fates’ theory. Studying 12 European democracies, Turnbull‐Dugarte and Townsley (Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte and Townsley2020) show that European LGB individualsFootnote 2 are more inclined to vote compared to their heterosexual counterparts. Perrella et al. (Reference Perrella, Brown and Kay2012) find evidence of strategic voting among Canadian LGBT voters in the 2006 parliamentary elections to safeguard the newly enacted same‐sex marriage bill from repeal. Moreau et al. (Reference Moreau, Nuño‐Pérez and Sanchez2019) show that US LGBTQ Latinx voters are more prone to political participation than their non‐LGBTQ Latinx counterparts due to having ‘linked fates’ feelings to both the LGBTQ‐ and Latinx communities. Bowers and Whitley (Reference Bowers and Whitley2020) show that trans‐ and gender non‐conforming individuals exhibit higher rates of voter registration due to oppositional consciousness. Drawing from the US General Social Survey data, Swank and Fahs (Reference Swank and Fahs2019) show that LGB individuals are more than twice as likely to protest as heterosexuals (see also Turnbull‐Dugarte & Townsley, Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte and Townsley2020). Additionally, numerous studies provide evidence of sexuality‐driven disparities in political attitudes and party preferences (Albaugh et al., Reference Albaugh, Harell, Loewen, Rubenson and Stephenson2023; Egan, Reference Egan2012; Grollman, Reference Grollman2017; Hunklinger & Ferch, Reference Hunklinger and Ferch2020; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Rogers and Sherrill2011; Turnbull‐Dugarte, Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte2020b; Wurthmann, Reference Wurthmann2023).

While these studies provide valuable insights into political engagement among sexual and gender minorities, they possess certain limitations. First, many studies focus on single elections in which LGBT+ issues were salient (Egan, Reference Egan2012; Perrella et al., Reference Perrella, Brown and Kay2012; Turnbull‐Dugarte & Townsley, Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte and Townsley2020), possibly capturing temporary spikes in mobilization. Second, much of the evidence stems from survey data (Egan, Reference Egan2012; Hunklinger & Ferch, Reference Hunklinger and Ferch2020; Jones, Reference Jones2021; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Rogers and Sherrill2011; Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Nuño‐Pérez and Sanchez2019; Turnbull‐Dugarte, Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte2020b; Wurthmann, Reference Wurthmann2023). Random samples drawn from the general population capture only a handful of LGBT+ individuals due to the small size of the LGBT+ population and underreporting (Grimmer et al., Reference Grimmer, Hersh, Meredith, Mummolo and Nall2018; Pathela et al., Reference Pathela, Hajat, Schillinger, Blank, Sell and Mostashari2006; Sell et al., Reference Sell, Kates and Brodie2007). Third, most existing studies are focused on majoritarian/plurality electoral systems with lower electoral coordination costs (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Rogers and Sherrill2011; McThomas & Buchanan, Reference McThomas and Buchanan2012; Perrella et al., Reference Perrella, Brown and Kay2012; Turnbull‐Dugarte, Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte2020a). This study is able to address some of these limitations by employing verified – rather than self‐reported – data and situating the study in the less studied proportional representation context (Anzia, Reference Anzia2011; Cox, Reference Cox2015). Additionally, by analyzing multiple elections within the same electoral context, this study generates insightful perspectives on voting behaviour among non‐straight individuals.

LGB turnout after LGBT+ rights enactment: Expectations

The ‘linked fates’ theory proposes that shared experiences of discrimination foster increased political participation among social minorities (Dawson, Reference Dawson1995; Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Nuño‐Pérez and Sanchez2019). Nevertheless, there is limited understanding of the dynamics when some of this discrimination subsides due to legal interventions or changing attitudes toward social minorities and their rights. Two potential scenarios are outlined below.

One potential scenario is that minority voters might gradually reduce their level of political engagement as their core group interests become legally protected and the social discrimination they experience begins to diminish. If the ‘linked fates’ mechanism is closely tied to experiences of discrimination, it could reasonably lose some of its influence as discrimination is mitigated, at least to a certain extent (Chong & Rogers, Reference Chong and Rogers2005; Turnbull‐Dugarte & Townsley, Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte and Townsley2020). Consequently, any disparities in political participation driven by minority status could gradually diminish.

Over the past three decades, there has been a rapid but uneven expansion of LGBT+ rights across the Western world (Ayoub & Page, Reference Ayoub and Page2020; Ayoub et al., Reference Ayoub, Page and Whitt2021; Mos, Reference Mos2020; Velasco, Reference Velasco2023). Countries such as Spain, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, as well as Scandinavian countries, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Uruguay, have been at the forefront of swiftly enacting and implementing laws and policies that support the rights of sexual and gender minorities (Leveille, Reference Leveille2023). These rights encompass areas like anti‐discrimination, marriage equality, parenting rights, gender self‐identification and recognition, and improved access to specialized healthcare, among others (Schaffner & Senic, Reference Schaffner and Senic2006). The changes are often driven by shifts in public attitudes towards sexual and gender minorities, leading to reduced levels of social discrimination (Antecol et al., Reference Antecol, Jong and Steinberger2008; Flores, Reference Flores2019, p. 19; Flores & Barclay, Reference Flores and Barclay2016; Mule et al., Reference Mule, Ross, Deeprose, Jackson, Daley, Travers and Moore2009). It is plausible to anticipate that as LGBT+ rights progress, the urgency of the shared cause might decrease, potentially resulting in a gradual decline in political engagement among the LGB electorate. Previous research on political engagement of other minority groups provides support for this expectation. For instance, Chong and Kim (Reference Chong and Kim2006) show that Latinx and Asian voters in the United States are increasingly inclined to vote based on their class affiliation rather than ethnic identity, as discrimination against these groups diminishes.

The waning influence of legal and social discrimination as a motivating factor for minority voters could lead to a spill‐over effect that revitalizes the significance of other structural factors that impede minority participation. For instance, minority groups with dispersed and small populations may encounter elevated mobilization costs in the absence of a potent mobilizing factor (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Lajevardi, Lindgren and Oskarsson2022). Additionally, pre‐existing and deeply ingrained inequalities in income, access to education and systemic elements inherent to the electoral system might regain prominence as barriers to voter participation (Just, Reference Just2017; Leighley & Nagler, Reference Leighley and Nagler2014; Verba & Nie, Reference Verba and Nie1972). Past research demonstrates that turnout among minority voters can be negatively influenced by factors such as the limited presence of viable minority candidates (Rocha et al., Reference Rocha, Tolbert, Bowen and Clark2010), high overall turnout rates (Anzia, Reference Anzia2011; Heath et al., Reference Heath, McLEAN, Taylor and Curtice1999), or electoral systems that minimize the impact of a minority vote. Based on these arguments, it is expected that:

Hypothesis 1: Sexuality‐driven positive disparities in voter participation will diminish following the enactment of key LGBT+ rights.

The advancement of LGBT+ rights could also potentially facilitate the enduring inclusion of LGB individuals in democratic processes (Mettler, Reference Mettler2019; Pierson, Reference Pierson1993). Recent significant political achievements may contribute to fostering a norm of democratic participation among minority voters (Soss & Schram, Reference Soss and Schram2007). Several mechanisms could work together to reinforce this norm over time. First, a major political triumph can amplify the perception that the system is responsive to minority concerns, consequently engendering empathetic connections with other marginalized groups still grappling with structural discrimination. This could encompass other minority groups within the country, such as ethnic, religious or foreign‐born minorities (Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Nuño‐Pérez and Sanchez2019), as well as fellow members of sexual and gender minorities globally (de Wit et al., Reference de Wit, Adam, den Daas, Yerkes and Bal2022). Prior research points to the international unevenness of progress in LGBT+ rights and its susceptibility to backlash (Ayoub & Page, Reference Ayoub and Page2020; Flores & Barclay, Reference Flores and Barclay2016; Velasco, Reference Velasco2023). The desire to assist other minority groups in precarious situations could sustain the electoral mobilization of LGB voters. Second, political parties are likely to keenly observe the mobilization of LGB voters following the enactment of LGBT+ rights (Karol, Reference Karol2023). To capture this previously untapped source of votes, political parties might continue advocating for pertinent minority policies domestically, pledging to champion minority interests internationally and/or enhancing the representation of minority candidates (Hunklinger & Ferch, Reference Hunklinger and Ferch2020; Spierings, Reference Spierings2020; Spierings et al., Reference Spierings, Lubbers and Zaslove2017). Third, the organizations established to support the equal rights movement are unlikely to disappear after the implementation of key LGBT+ policies (Bowers & Whitley, Reference Bowers and Whitley2020; Egan, Reference Egan2012; Hertzog, Reference Hertzog1996; Swank & Fahs, Reference Swank and Fahs2016). Instead, these groups are likely to actively work to sustain the mobilization of the LGBT+ electorate, aiming to uphold the newly achieved legal status quo and drive further emancipation (Bowers & Whitley, Reference Bowers and Whitley2020; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Wahlström and Wennerhag2018; Swank & Fahs, Reference Swank and Fahs2016). They might achieve this by raising awareness about lingering sources of inequality domestically or by directing their members’ attention to the conditions of LGBT+ individuals abroad. Finally, minority voters might remain engaged to safeguard their recently acquired rights, particularly if they perceive a viable political force posing a threat to these rights (Turnbull‐Dugarte & Townsley, Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte and Townsley2020). The findings of Perrella et al.’s Reference Perrella, Brown and Kay2012 study support this explanation. The Canadian Civil Marriage Act was enacted in 2005 under the Liberal Party minority government. In the lead‐up to the 2006 parliamentary election, the Conservative Party pledged to repeal the act. Fearing the potential loss of the recently gained right to marry, Canadian LGBT voters strategically voted against Conservative Party candidates. These arguments are consistent with the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: Sexuality‐driven, positive disparities in voter turnout will remain in place following the enactment of core LGBT+ rights.

Note that this study cannot empirically illuminate the exact mechanisms that drive the voting behaviour of LGB individuals after the enactment of core LGBT+ rights. However, the study is well‐equipped to generate particularly reliable insights into voter turnout among LGB individuals in a context where LGBT+ rights are relatively well protected. Consequently, it is well‐positioned to evaluate the two competing hypotheses. The research design of this study is presented in the following section.

Research design

Sweden: Where the grass is greener

The goal of this study is to analyze sexuality‐driven disparities in contexts of strong LGBT+ rights protection (Flores, Reference Flores2019; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Wahlström and Wennerhag2018). Sweden serves as an ideal case for such an analysis. The country ranks well in various international assessments of LGBT+ rights protection (Leveille, Reference Leveille2023).Footnote 3 What is more, the country took several important steps towards the legal emancipation of LGBT+ people. In 1972, Sweden became the first country globally to allow individuals to legally change their gender (Regeringskansliet, 2018).Footnote 4 In 1995, Sweden was among the pioneers in legalizing same‐sex partnerships. In 2003, relevant regulations were amended to allow for adoptions by same‐sex couples. Additional advancements followed, including state‐funded in‐vitro fertilization for same‐sex couples in 2005 and the enactment of gender‐neutral marriage in 2009 (Regeringskansliet, 2018). Within two decades, Swedish LGBT+ individuals gained significant rights, including the ability to change legal gender, the right to marry and the right to parenthood. Presently, non‐straight and trans/non‐binary individuals in Sweden can serve in the military and donate blood without concealing their sexual orientation or gender identity. These swift changes were facilitated in part by a relatively rapid shift in public attitudes toward sexual and gender minorities and their rights. In 2006, the European Commission survey indicated that 71 per cent of Swedes supported same‐sex marriage. By 2019, 98 per cent of Swedes believed that LGB individuals should enjoy the same rights as heterosexuals, marking the highest proportion within the European Union (EU )(European Commission, 2019). Overall, Sweden fulfils the necessary conditions for this study, providing a context of robust LGBT+ rights protection, coupled with positive societal attitudes towards these rights. Furthermore, over a decade has passed since the last significant LGBT+ community‐empowering legislation – same‐sex marriage – was enacted, allowing for the study of long‐term trends in minority voter turnout within a context of solid minority rights protection.

Sweden possesses certain characteristics that might hinder political participation among sexual minorities following the enactment of LGBT+ rights. First, Sweden employs a proportional representation (PR) electoral system. PR systems tend to exhibit higher turnout rates compared to majoritarian systems, thereby diminishing the impact of an organized minority vote on electoral outcomes (Anzia, Reference Anzia2011; Jackman, Reference Jackman1987; Just, Reference Just2017). Swedish parliamentary elections consistently demonstrate high turnout rates, even by PR standards (Persson et al., Reference Persson, Sundell and Öhrvall2014). Since the 1958 election, the general turnout rate in parliamentary elections has not fallen below 80 per cent. While the turnout rate for EP elections is comparatively lower, such as the 55 per cent in the 2019 election, it remains relatively high in a cross‐national perspective. Second, proportional seat allocation formulas often yield multiparty systems. This structural attribute could also adversely affect minority political participation, particularly if multiple political parties vie for the votes of minority groups (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Lajevardi, Lindgren and Oskarsson2022; Jackman, Reference Jackman1987; Just, Reference Just2017; Spierings, Reference Spierings2020). Of the eight political parties currently represented in the Swedish Riksdag, seven, including the formerly sceptical Christian Democrats (KD), openly champion the protection of LGBT+ rights in their party programs (Spierings, Reference Spierings2020). This broad alignment with LGBT+ issues might reduce the incentive for LGB voters to participate in elections.

However, specific factors related to Sweden's fragmented party system and the institutionalization of the LGBT+ rights movement could serve as mobilizing factors for the LGB electorate. First, in a competitive electoral landscape with slim voting majorities, political parties cannot afford to overlook any potential source of votes. Consequently, Swedish political parties continue to advocate for LGBT+ policies to attract LGBT+ votes. Seven political parties have established LGBT+ party wings, which incubate new policy proposals and cultivate LGBT+ candidates. Second, the growing electoral influence of the Sweden Democrats (SD) could mobilize LGB voters. As of 2023, the SD, known for its anti‐immigration stance, ranks as the second‐largest party in the Riksdag. Although the party commits to upholding the existing rights of the LGBT+ community on paper (Åkesson & Herrstedt, Reference Åkesson and Herrstedt2010), it opposes the further expansion of these rights (Voss, Reference Voss2022). Lastly, the Swedish LGBT+ movement comprises several highly institutionalized and effective organizations that maintain their political relevance through op‐eds and public discussions with Swedish politicians (Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Wahlström and Wennerhag2018). The monthly magazine QX has a circulation of 30,000 print copies, and The Swedish Federation for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex Rights (RFSL) boasts 36 branches across Sweden and over 7,000 members. This organization is one of many with projects focused on the wellbeing of LGBT+ individuals both in Sweden and internationally.

Taken together, the case of Sweden provides an ideal testing ground for both competing hypotheses. On the one hand, the proliferation of LGBT+ rights, positive societal attitudes towards these rights, high voter turnout rates, and the presence of multiple effective advocates for LGBT+ causes might dampen voter turnout among LGB individuals. Conversely, the efforts of Swedish political parties to integrate sexual minorities into party politics, the potential mobilizing impact of the SD, and the strength of the Swedish LGBT+ rights movement create favourable conditions for the second hypothesis.

Data

In the upcoming analyses, we utilize the comprehensive Swedish administrative data, curated by Statistics Sweden (SCB).Footnote 5 This collection of datasets encompasses verified individual‐level information covering the entire population of Sweden. What sets this collection apart is that it includes verified turnout data for six electoral contests conducted from 1982 to 2018. The recording of voter participation is conducted by polling station clerks who meticulously document it in precinct voter rolls. The reliance on verified turnout data mitigates some of the social desirability bias that often affects survey‐based inquiries to voter participation (Grimmer et al., Reference Grimmer, Hersh, Meredith, Mummolo and Nall2018). Moreover, the Swedish administrative data comprises of crucial details related to civil‐ and family status, facilitating the identification of non‐straight individuals in a manner that circumvents some of the problems encountered by previous research on sexual minorities. Relevant to the present study, these registries encompass comprehensive and regularly updated data concerning each individual's residence, foreign‐born background, age, educational achievements, number of children and other pertinent factors. We have access to this data spanning from January 1990 to December 2018, with some segments tracing back to the 1960s.Footnote 6

Concepts and their operationalization

The central independent variable of focus in this study is sexual identity. Using the unique family identifier SCB employs for married or cohabiting partners who share children, we can identify non‐straight individuals who, at any given point between 1995 and 2018, are married, in formal partnerships or co‐parenting. In addition to that, we can leverage an older civil status identifier to identify LGB individuals who, between 1995 and 2009, entered into a registered partnership with someone of the same legal sex, even if they did not move in together. This methodology enables us to generate a sample comprised of 16,110 LGBT+ individuals.Footnote 7 Notably, this is a sizable sample within the context of existing literature, particularly given that we are dealing with verified, rather than self‐reported, data concerning cohabitation, civil status and parenthood. This distinction differentiates our study from previous research, which often had to rely on self‐reported data due to data limitations.

However, it is important to acknowledge that this sample represents only a subset of the entire LGB population. Notably absent are LGB individuals who are single, unmarried or childless. Due to these limitations, some LGB individuals might even find themselves in the control sample. Additionally, our subsample of the LGB community may exhibit systematic differences from the larger community. Consequently, it is essential to emphasize that the results presented below primarily pertain to LGB individuals who are willing to publicly express their non‐straight identity through marriage, partnership or co‐parenting with a same‐sex partner.

Given these challenges related to our sample, we have implemented specific measures to enhance the internal validity of our study's outcomes. Recognizing that our LGB sample mainly consists of partnered or formerly partnered individuals, it is imperative to ensure that the estimated participation rates among LGB individuals are appropriately compared to a relevant reference category. Prior research indicates that partnered individuals are more likely to vote compared to their single counterparts due to factors such as better access to resources like money and free time, which are robust predictors of political participation (Just, Reference Just2017; Persson et al., Reference Persson, Sundell and Öhrvall2014). Consequently, a potential positive gap in turnout between our LGB sample and the broader adult population of Sweden might stem from their partnered status. To address this concern, we generate a counterfactual sample of straight individuals – a control straight sample – employing a similar approach to that used to generate the LGB sample. The control straight sample consists of heterosexual individuals who, at any given point between 1995 and 2018, are married or co‐parenting with a person of the opposite sex.

The primary response variable in our analysis is individual‐level voter turnout. This verified indicator assumes a value of ‘1’ for adults who participated in either of the six electoral contests under investigation. Given that we will conduct election‐specific analyses, we employ distinct turnout indicators for each of the six contests. Additionally, we incorporate an array of control variables that previous research has identified as significant determinants of political participation. These encompass age, sex, income, educational attainment, place of residence, current civil status and foreign‐born status. Notably, all this data are verified and available for the entire Swedish population. This means that we can access individuals’ real annual income or educational attainment data, rather than relying on their self‐reported information. Regarding educational attainment, we possess a comprehensive measure that not only encompasses the level of education achieved but also the specific type of education received.

Empirical strategy

The purpose of the empirical analysis is to establish whether there are any sexuality‐driven gaps in voter turnout between LGB persons and similar straight counterparts after the enactment of core LGBT+ policies. Because our sample of non‐straight individuals is primarily comprised of partnered individuals, comparing them to the rest of the adult population is likely to induce bias. While a comparison of turnout rates between partnered LGB and partnered straight individuals seems promising, this approach could yield biased estimates if our LGB sample systematically differs from the straight sample. Relevant descriptive statistics on the LGB‐ and straight samples, summarized in Table 1, reveal that this is indeed the case. Similar to findings in other contexts, partnered or formerly partnered non‐straight individuals in Sweden tend to be younger, more affluent and better educated compared to their heterosexual counterparts (Black et al., Reference Black, Gates, Sanders and Taylor2000; Herek et al., Reference Herek, Norton, Allen and Sims2010; Jones, Reference Jones2021). Additionally, our non‐straight sample sees an overrepresentation of women and individuals with foreign‐born backgrounds, which is also in line with past findings (Herek et al., Reference Herek, Norton, Allen and Sims2010; Kolk & Andersson, Reference Kolk and Andersson2020).

Table 1. The LGB treatment group and the straight counterfactual group in 2018

Notes: a Statistical significance of the disparities in means/proportions between the treatment‐ and control groups is examined through t‐tests or Z‐tests, depending on the nature of the variable. All the reported means and proportions are significant at the 1% level of significance.

Educational attainment is measured using a detailed, three‐digit classification, Sun2000nivå, which delineates both the level and type of education attained. Generally, higher average values correspond to elevated levels of educational achievement. Income is measured as total annual net income, measured in 100 SEK units. An individual is categorized as having a foreign‐born background if both of their parents were born outside of Sweden.

To ensure fair comparisons, we use different empirical strategies. First, a propensity‐score matching technique is employed. This method enables the selection of individuals from the broader straight sample who closely resemble those in the non‐straight sample across a predetermined set of attributes. Propensity scores are derived through probit regression, and matching is executed through the Mahalanobis approach. This results in two distinct sets of samples: a treatment group comprised of LGB individuals, and a matched control group drawn from the straight control sample, the latter designed to closely resemble the LGB sample. Using these generated samples, we can then compare average turnout rates between them using appropriate statistical tests. Given our access to annual civil data, two separate sets of samples are constructed for the 2009/2010 elections and the 2018/2019 elections. This approach allows us to include individuals who passed away after the 2009/2010 or were too young to vote.

Determining which covariates to match on is a complex issue. Typically, it is not advisable to match on ‘post‐treatment’ covariates – those characteristics obtained after the treatment feature has been determined (Acharya et al., Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016; Angrist & Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2009, p. 49; Egan, Reference Egan2012, p. 605; Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum1984). As people usually become aware of their sexual orientation relatively early in life, we match on attributes that are ‘assigned‐at‐birth’, such as sex, birth year and foreign‐born background. Using common predictors of voter turnout, such as educational attainment, income or place of residence, in a matching model is not advisable due to the so‐called ‘bad control problem’ (Angrist & Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2009). These attributes are all ‘post‐treatment’ and can be influenced, at least in part, by the treatment variable (Antecol et al., Reference Antecol, Jong and Steinberger2008; Fine, Reference Fine2015; Poston et al., Reference Poston, Compton, Xiong and Knox2017; Río & Alonso‐Villar, Reference Río and Alonso‐Villar2019). As a matter of consequence, their inclusion might dilute the impact of sexuality on voter turnout. Because not many individual attributes are prior to one's sexual identity, we also opt to match on average turnout rate in one's place of living. Though ‘post‐treatment’, we find it unlikely that this particular characteristic is directly related to sexual identity.Footnote 8 The inclusion of this covariate allows us to account for local overall propensity to partake in elections.

Second, considering that factors such as education, income or place of residence have been established as significant predictors of voter turnout (Persson et al., Reference Persson, Sundell and Öhrvall2014), it is important to ascertain whether any potential variations in voter turnout driven by sexuality can be attributed to inherent disparities in income or educational achievements between our treatment and control groups. To address this concern, we estimate additional models in which we compare turnout rates between treatment and control groups while incorporating fixed effects for educational attainment, income, age and place of residence. By adopting this approach, we can effectively compare individuals who share the same attributes of income, education, place of residence and age. Furthermore, to bolster the robustness of the findings, we study the development in sexuality‐driven disparities in voter turnout over time. This is done to ascertain whether those who are identified as LGB individuals in our study have always had a particular proclivity to partake in elections but also to examine whether any eventual gaps in voter turnout between our straight‐ and non‐straight groups are gradually waning. The technicalities of these models are presented below alongside the results.

Results

Matching: persistent sexuality‐driven disparities in voter turnout

In this section of the results, we present the outcomes of the models in which individuals from our LGB sample are paired with their identical heterosexual twins using propensity‐score matching. Disenfranchised adults (e.g., legal aliens) are excluded from the analyses. We estimate two matching models – one for the 2009‐ and 2010 elections and another for the 2018‐ and 2019 elections. Table 2 below provides an overview of the findings. It is important to note that the matching process was successful, resulting in two statistically identical groups on the matching attributes. This is in line with our objective to emulate experimental conditions where the treatment and control groups closely resemble each other, differing primarily in the treatment condition – in this case, sexuality.

Table 2. Sexuality gap in voter turnout: Propensity scores matching

Notes: The matched sample consists of 13,082 LGB persons and 5,651 straight persons for the 2009‐/2010 model and 14,665 LGB persons and 6,795 straight persons for the 2018‐/2019 model. Significance:

*p < 0.05;

**p < 0.01;

***p < 0.001.

Table 2 indicates a positive sexuality gap in voter turnout, evident in both the 2009‐ and 2019 EP elections and the 2010‐ and 2018 parliamentary elections. For the parliamentary elections, the gap stands at six (2010) and three (2018) percentage points, respectively. In the case of EP elections, the gap is even more pronounced – 16 and 15 percentage points, respectively. The larger magnitude of the sexuality gap in the EP elections is in line with previous research on second‐order elections and minority mobilization (Anzia, Reference Anzia2011). Turnout rates among the counterfactual straight group were 48 and 60 per cent, respectively, and within our LGB sample, turnout rates were 59 and 74 per cent, marking a notable 16 and 15 percentage point increase compared to similar straight individuals. This signifies substantial turnout gaps.

Conversely, Swedish parliamentary elections epitomize first‐order elections and are characterized by high overall turnout rates – especially for countries with non‐compulsory voting (Persson et al., Reference Persson, Sundell and Öhrvall2014). In the 2010‐ and 2018 elections, the overall turnout rates were 85 and 87 per cent. Among the LGB voters identified in this study, turnout rates reached 92 and 94 per cent, respectively. When contrasted with the turnout rates of our straight counterfactual group (86 and 90 per cent), this translates into a positive sexuality‐driven turnout gap of six and three percentage points. Given the context of the high overall turnout rate, these gaps are far from insignificant. As a robustness check, we re‐estimate the matching models, dropping the two post‐treatment covariates. The results, which corroborate those found here, can be found in the Supporting Information Appendix, Tables A2 and A3 (pp. 5–7).

In light of these findings, we can confidently conclude that there is a substantial, positive sexuality‐driven gap in voter turnout. Although the gap appears to have diminished slightly over time in these matching models, it remains robust and statistically significant a decade after the introduction of same‐sex marriage. It is crucial to emphasize that the shrinking gap is not necessarily indicative of reduced engagement within the LGB electorate. Instead, the overall turnout rate within our LGB sample has actually increased over time. This reduction in the gap stems from the increased propensity of straight counterfactual voters to participate in the latter two elections, rather than any decrease in LGB voter mobilization. In the remainder of this section, we use various approaches to ascertain the internal validity of these findings and examine whether the sexuality gap in voter turnout is gradually waning.

Is the gap driven by education, income or place of living?

Age, education, income and place of residence are established individual‐level indicators of political engagement (Persson et al., Reference Persson, Sundell and Öhrvall2014). Given that these attributes are accumulated by individuals over their lifetimes, they inherently fall within the ‘post‐treatment’ phase (Angrist & Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2009). Consequently, straight or non‐straight classification precedes the determination of educational attainment, income and place of living. Moreover, as sexuality itself serves as a stable predictor of educational attainment (Fine, Reference Fine2015; Mollborn & Everett, Reference Mollborn and Everett2015), income (Antecol et al., Reference Antecol, Jong and Steinberger2008) and place of living (Poston et al., Reference Poston, Compton, Xiong and Knox2017), incorporating these factors into the matching model would dilute the impact of sexuality on the primary outcome of interest – voter turnout. To ensure the robustness of the aforementioned results against potential variations in educational attainment, age, place of residence and income, we use linear regression models with fixed effects. We use linear models – as opposed to logistic regression – for a more straightforward interpretability of the results. The models that follow encompass the complete LGB and counterfactual straight samples, resulting in a significantly larger pool of observations. We explore the average inclination of identified LGB voters to participate in the four post‐rights elections relative to comparable heterosexual individuals. Our models encompass fixed effects for birth year, income, education and municipality of residence. This approach enables a comparison exclusively among individuals sharing identical levels of education, residing in the same municipality and belonging to the same age group. The findings are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Sexuality gap in turnout, 2009–2019

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

∗p < 0.05;

∗∗p < 0.01;

∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Table 3. Disenfranchised adults (e.g., legal aliens) are excluded from the analyses.

Starting with the elections to the EP, we observe that, on average, an LGB individual exhibited a 14 and 10 percentage point greater likelihood of voting in 2009 and 2019, respectively, in contrast to an average heterosexual from the counterfactual group. These outcomes reinforce the existence of the substantial sexuality gap established in the preceding matching models. Examining the parliamentary elections, we ascertain that, on average, an LGB individual demonstrated a three (in specifications 2 and 4) percentage point higher likelihood of casting a vote compared to an average straight voter from the counterfactual group. These results merit consideration within the context of the notably high overall turnout rates, standing at 85 and 87 per cent in 2010 and 2018, respectively. A positive turnout gap of three percentage points between LGB voters and their comparable straight counterparts in this context indeed represents a substantial disparity in voter turnout. For each election, we provide descriptive statistics at the end of Table 3, detailing the overall voter turnout rate, as well as specific turnout rates for both the LGB‐ and the counterfactual samples. These statistics also indicate a positive sexuality‐driven difference in voter turnout.

Summing up, our analysis reveals compelling evidence of a robust and statistically significant sexuality‐driven disparity in voter turnout, evident both shortly after and a decade following the enactment of same‐sex marriage. This gap remains in place even when differences in income, education, age and place of residence are accounted for. In the context of parliamentary elections, the gap has consistently held at around three percentage points. As for the EU elections, the gap appears to have declined by two percentage points but remains substantial. As a robustness check, we re‐estimate these models and include controls for being married/formally partnered right before the election, another common predictor of voter turnout. The results, summarized in Supporting Information Table A4 (pp. 7–8), corroborate those found in Table 3.

Sexuality gap before LGBT+ rights?

Up to this point, the paper has accumulated substantial evidence supporting the presence of a positive voter turnout gap between non‐straight and comparable straight voters, particularly within the context of strong legal protection for LGBT+ rights. Nonetheless, it raises the question of whether the individuals included in our non‐straight sample might possess an inherently greater propensity to engage in democratic participation. This section aims to address this query studying the voting behaviour of those in our LGB‐ and counterfactual samples in the 1982 and 1994 parliamentary elections.

The 1982 election marked the year when Sweden recorded its first HIV case, yet the campaign was unaffected by the subsequent surge of hostility towards the LGBT+ community that swept through the country during the latter half of that decade. The 1994 election followed 3 months after the enactment of the registered partnership bill, signifying initial progress towards civil equality for the LGBT+ community. This timeframe represents the early stages of the equal rights movement, with LGBT+ issues not yet occupying as prominent a place on the agenda as they would in the following years. Among the 16,000 individuals comprising our LGB sample in 2018, 4,257 and 8,922 were adults eligible to vote in the 1982 and 1994 elections, respectively.

For the ensuing analyses, we adopt the same methodology as outlined in the subsection above. Consequently, we utilize the complete LGB and counterfactual samples for the years 1982 and 1994. We proceed by estimating the average inclination to vote among our LGB individuals relative to their comparable straight counterparts. The identical set of fixed effects for year of birth, education, income and place of residence is applied. Regarding the 1982 election, a modest sexuality gap of approximately one percentage point is identified – a figure two percentage points lower than the gaps discovered in the 2010 and 2018 elections. For the 1994 election, the gap exhibits a slight increase, although it remains significantly lower than the three percentage points reported in Table 3 above. Note also that the descriptive statistics at the end of Table 4 do not yield evidence of a sexuality‐driven turnout gap in the 1982‐ and 1994 contests.

Table 4. Sexuality gap before rights, 1982 and 1994

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses. For model specifications 1 and 2, education and income data for 1990 is used because earlier data is not available.

∗p < 0.05;

∗∗p < 0.01;

∗∗∗p <0.001.

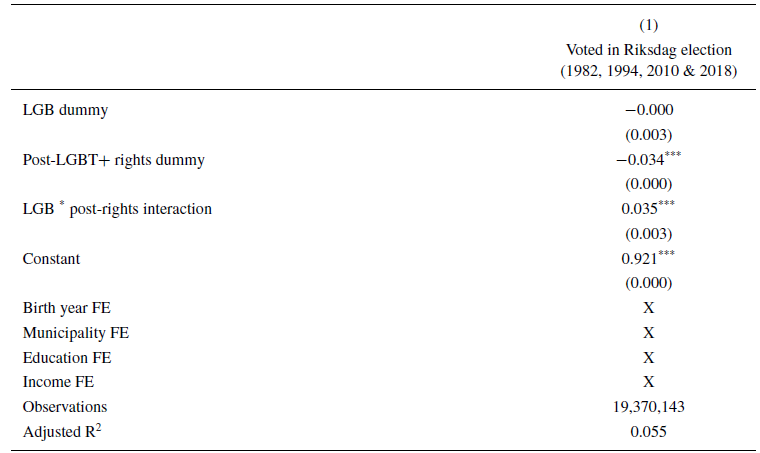

It is crucial to establish whether the disparities observed in voter turnout before the enactment of LGBT+ rights are statistically distinct from those identified in post‐rights elections. To address this, we pool the samples from the four parliamentary elections, creating a panel. We then create a binary variable representing the two post‐rights elections and introduce an interaction term between this variable and the LGB identifier. This approach enables us to evaluate whether the sexuality gaps in voter turnout during the 1982 and 1994 elections were of a smaller magnitude compared to those found in the two elections conducted subsequent to the introduction of the gender‐neutral marriage bill in 2009. The outcomes of this analysis are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Sexuality gap in parliamentary elections: Pre‐ and post‐rights

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

∗p < 0.05;

∗∗p < 0.01;

∗∗∗p <0.001.

The findings can be summarized as follows. The lack of statistical significance for the LGB dummy variable implies the absence of substantial evidence supporting a robust sexuality‐driven gap in voter turnout during the two pre‐rights elections, namely 1982 and 1994. In essence, individuals within both our LGB and counterfactual samples exhibited a similar average propensity to participate in these two electoral contests. Conversely, the statistically significant and positive interaction term between the LGB identifier and the post‐rights elections identifier further corroborates the existence of a sexuality gap in voter turnout after the enactment of same‐sex marriage, amounting to approximately three percentage points during the two post‐rights parliamentary elections. This outcome is also visually depicted in Figure 1 for better clarity. The figure illustrates that while the sexuality gap is not distinguishable from zero in the 1982 and 1994 elections, it stands above three percentage points in the 2010 and 2018 elections.

Figure 1. Sexuality gap pre‐ and post‐LGBT+ rights effects [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Sexuality gap over time

In this concluding results section, our focus shifts to the remaining question: has the sexuality‐driven gap in voter turnout diminished over the decade following the introduction of same‐sex marriage? To address whether the observed slight disparities in the post‐rights sexuality gap (as detailed in Tables 2 and 3 above) hold statistical significance, we pool data across the post‐rights elections and establish two models: one for parliamentary elections and another for EP elections. In both models, we introduce a dummy denoting the latter of the two elections – the ‘Decade later’ dummy – and interact this dummy with the LGB identifier. The presence of statistically significant interaction terms would indicate a change in the magnitude of the sexuality gap over time. The outcomes of this analysis are captured in Table 6.

Table 6. Pooled post‐LGBT+ rights models: EP and Riksdag elections (2009–2019)

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

∗p < 0.05;

∗∗ p < 0.01;

∗∗∗ p < 0.001.

Concerning parliamentary elections (specification 2), the model helps to ascertain that the sexuality gap has remained consistent between the two parliamentary elections that followed the enactment of the same‐sex marriage legislation. This means that we find no indications that the positive sexuality gap has declined in elections to the Swedish Riksdag. In contrast, for EP elections, a slight – yet statistically significant – reduction in the sexuality gap is identified, decreasing from 14 to 12 percentage points. The gap remains considerably large: LGB individuals were still 12 percentage points more likely than their comparable heterosexual counterparts to participate in the 2019 EP election.

Figure 2 helps to further contextualize these results. On the left‐hand side, the predicted turnout rates for the LGB and control samples are displayed, with the counterfactual straight group exhibiting narrow confidence intervals due to the substantial sample size and resultant precision. On the right‐hand side, the magnitude of the sexuality gap between the two sets of elections is illustrated. Upon examining both sets of graphs, it becomes evident that the minor decline in the sexuality gap for EP elections is not attributed to a demobilization of the LGB electorate. Quite the contrary, the projected turnout for an LGB voter has actually risen between the 2009 and 2019 EP elections. Concurrently, a slightly greater upswing in projected turnout is evident within the straight counterfactual sample. This signifies that the slight decrease in the sexuality gap between the 2009 and 2019 EP elections is not the result of decreased engagement within the LGB electorate.

Figure 2. Sexuality gap post‐LGBT+ rights over time [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The online appendix contains two alternative renditions of Figure 2 (pp. 8–10). One where we keep the same y‐axis for better comparison across elections and one where we zoom in on the confidence intervals.

In summary, the findings from this results section help to establish that there are significant positive disparities in voter turnout between LGB voters and their equivalent straight counterparts. These gaps are absent prior to the enactment of same‐sex partnerships in 1994, but are manifested both shortly after and a decade following the implementation of gender‐neutral marriage in 2009. Importantly, the size of this gap has not diminished substantially a decade after the enactment of gender‐neutral marriage, which is commonly regarded as the fundamental core of LGBT+ rights in Sweden. These findings allow us to refute Hypothesis 1 and corroborate Hypothesis 2. The implications of this are discussed in the final section.

Concluding discussion

Past research highlights the significant role of shared experiences of discrimination as drivers of political participation among social minority groups (Dawson, Reference Dawson1995; Just, Reference Just2017; Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Nuño‐Pérez and Sanchez2019). This trend is also observed among sexual and gender minorities (Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Nuño‐Pérez and Sanchez2019; Turnbull‐Dugarte & Townsley, Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte and Townsley2020). Existing literature indicates that LGBT+ voters are more likely than their straight counterparts to participate in elections when LGBT+ rights are on the political agenda (Bowers & Whitley, Reference Bowers and Whitley2020; Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Nuño‐Pérez and Sanchez2019; Turnbull‐Dugarte & Townsley, Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte and Townsley2020). The aim of this paper was to investigate the impact of relatively strong LGBT+ rights protection on the political participation of sexual minorities. Two possible outcomes were presented: that the positive turnout gap between LGB and non‐LGB voters would either diminish or persist after LGBT+ rights expansion.

The findings reveal a robust, positive gap in voter turnout among LGB voters and their comparable straight counterparts. This gap persists both shortly after and a decade following the legalization of same‐sex marriage. While the gap is more pronounced in ‘second‐order’ EP elections, it is also present in parliamentary elections. Importantly, the disparity in voter turnout based on sexuality has not diminished significantly even a decade after the legalization of same‐sex marriage. These turnout patterns manifest themselves despite potential dampening factors on LGBT+ voter turnout, such as the presence of multiple advocates for LGBT+ rights, decreasing social discrimination and high overall turnout rates. Robustness analyses confirm that differences in age, income, location, educational attainment do not account for these gaps. Additionally, the disparities were not characteristic of the LGB electorate prior to the enactment of core LGBT+ rights.

The study's contributions to the literature are threefold. First, this study is the first to offer a comprehensive, longitudinal analysis of sexuality‐driven disparities in voter turnout. Previous research has mostly focused on individual electoral contests in which LGBT+ issues were prominently featured (Egan, Reference Egan2012; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Rogers and Sherrill2011; Perrella et al., Reference Perrella, Brown and Kay2012; Wurthmann, Reference Wurthmann2023). The restricted scope of analysis has presented challenges in determining the enduring or transient nature of the sexuality gap in political participation. This study demonstrates that the former scenario is likely applicable. Second, this study establishes that LGB individuals remain politically engaged even as the legal discrimination they have traditionally faced diminishes. By demonstrating that the sexuality gap did not exist prior to the enactment of core LGBT+ rights and yet remained in place a decade after their implementation, this study's findings indirectly emphasize the role of minority rights protection as a potential mechanism for ensuring the enduring inclusion of sexual minorities in democratic processes. In particular, the finding that the enactment of minority rights is not necessarily accompanied by a demobilization of the LGB electorate is likely to be of interest to students of minority political participation (Just, Reference Just2017). Finally, the paper introduces a novel method for identifying LGB individuals using a population‐wide registry, addressing biases associated with survey‐based approaches (Grimmer et al., Reference Grimmer, Hersh, Meredith, Mummolo and Nall2018; Kolk & Andersson, Reference Kolk and Andersson2020). To our knowledge, this is the first time a population‐wide registry is used to study the political behaviour of LGB persons. We hope that the identification method described in this paper will be used in different fields for those studying the wellbeing of sexual minorities and grappling with a lack of data (Antecol et al., Reference Antecol, Jong and Steinberger2008; Mule et al., Reference Mule, Ross, Deeprose, Jackson, Daley, Travers and Moore2009; Poston et al., Reference Poston, Compton, Xiong and Knox2017).

There are some caveats and areas for future research that merit consideration. First, it is worth reiterating that these findings are specific to a subset of the LGB community – namely those who are married, formally partnered or co‐parents. These individuals may have a particularly strong connection to their non‐straight group identity and might be more inclined to take action based on it compared to their counterparts. As this study has shown, these individuals are more affluent, more educated and younger, on average, than their heterosexual counterparts (Jones, Reference Jones2021). This study has employed various empirical techniques, including propensity‐score matching and fixed‐effects regression approaches, to ensure that our identified non‐straight individuals are compared to a relevant reference category. While the robustness of our analyses is not in doubt and the theoretical insights regarding minority electoral participation in contexts with robust minority rights protection likely extend to other members of the LGBT+ community, we encourage further empirical testing in this area once better data becomes available. We also encourage future research to explore additional dimensions of political behaviour beyond voter turnout, in order to examine the extent of the sexuality gap in political engagement. Prior investigations have revealed that the sexuality gap encompasses various other facets of political engagement, such as voter registration (Bowers & Whitley, Reference Bowers and Whitley2020), as well as inclinations towards protest, petition signing, or wearing of a political badge (Atteberry‐Ash et al., Reference Atteberry‐Ash, Swank and Williams2023; Swank & Fahs, Reference Swank and Fahs2019; Turnbull‐Dugarte & Townsley, Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte and Townsley2020). It is vital to investigate whether LGBT+ voters retain a higher propensity to participate in these forms of democratic action in contexts where their fundamental rights are safeguarded (Guntermann & Beauvais, Reference Guntermann and Beauvais2022).

Although the study does not delve into the mechanisms driving the observed sustained electoral mobilization among LGB voters in a context with well‐protected rights, it suggests avenues for further investigation. Future studies could assess the extent to which the sexuality‐driven turnout gap is influenced by empathy towards other minority groups – both domestically and internationally (Moreau et al., Reference Moreau, Nuño‐Pérez and Sanchez2019), sustainable integration of LGBT+ concerns into political agendas (Spierings, Reference Spierings2020), institutionalization of the LGBT+ rights movement, or concerns among LGB voters about potential rights erosion (Turnbull‐Dugarte & Townsley, Reference Turnbull‐Dugarte and Townsley2020). Given the varied landscape of LGBT+ rights protection and the recurring backlash (Ayoub & Page, Reference Ayoub and Page2020; Velasco, Reference Velasco2023), we hope that forthcoming research will explore the potential correlation between international threats to LGBT+ rights and the domestic electoral mobilization of LGBT+ voters. The magnitude of the sexuality gap in the Swedish EP elections specifically prompts us to question whether Swedish LGB voters participate in a show of solidarity with their EU counterparts whose rights are threatened or yet to be safeguarded. We hope that future research will shed light on this and other questions that arise from this study's findings.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to Pär Nyman. Not only did he write an early version of the code that serves as the foundation for the empirical analyses in this paper, but he also kindly guided me in navigating the intricacies of the Swedish administrative data. I also wish to acknowledge Sven Oskarsson and Karl‐Oskar Lindgren for their diligent efforts in digitizing the 2009 and 2010 turnout data, as well as for their invaluable feedback and financial support. A special thank you goes to Stuart Turnbull‐Dugarte for countless hours of feedback, mentoring, and cherished friendship. A previous version of this paper was presented at Princeton University's Queer Politics seminar and the ECPR Joint Sessions in Edinburgh. I am grateful to all participants at these events for their insightful feedback. Last but not least, my thanks extend to the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive and helpful comments.

The study was generously funded by the people of Sweden through the Swedish Research Council (grants: 2022‐01716_VR & 2022–05227_VR) and the European Research Council (grant ID: 683214).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Access to the Swedish population registries is subject to rigorous security‐ and ethical reviews. The data can only be accessed from within Sweden and is stored on a safe server. Due to the nature of the data and the rules regulating who may access it, it is – unfortunately – not possible to make the data available for replication purposes. This fact was made explicit before the peer‐review process. For more information, kindly contact the author.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1: Growth of same‐sex families in the Swedish civil registry

Table A2: Sexuality gap in turnout (2009‐10): pre‐treatment covariates only

Table A3: Sexuality gap in turnout (2018‐19): pre‐treatment covariates only

Table A4: Sexuality gap in turnout, 2009—2019

Figure A1: Figure 2 with consistent y‐axes

Figure A2: Figure 2 with more precise y‐axis